How to get pregnant for men

How can I improve my chances of becoming a dad – NHS

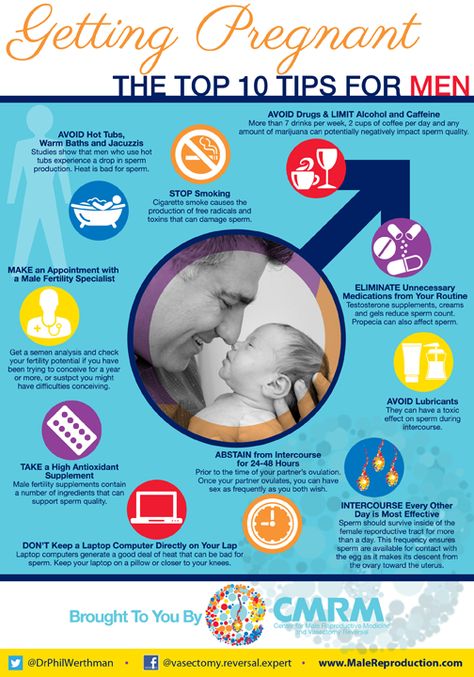

It may seem obvious, but you need to have regular sex (2 or 3 times a week) if you want to become a dad.

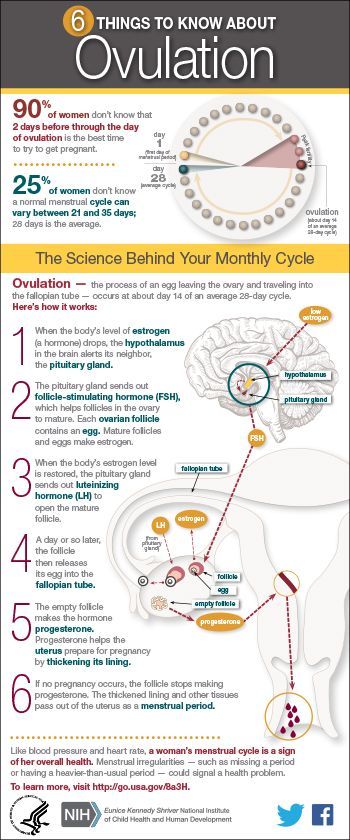

Having sex around the time your partner ovulates (when an egg is released from the ovary) will increase your chances of conceiving.

Read more about the best time to get pregnant.

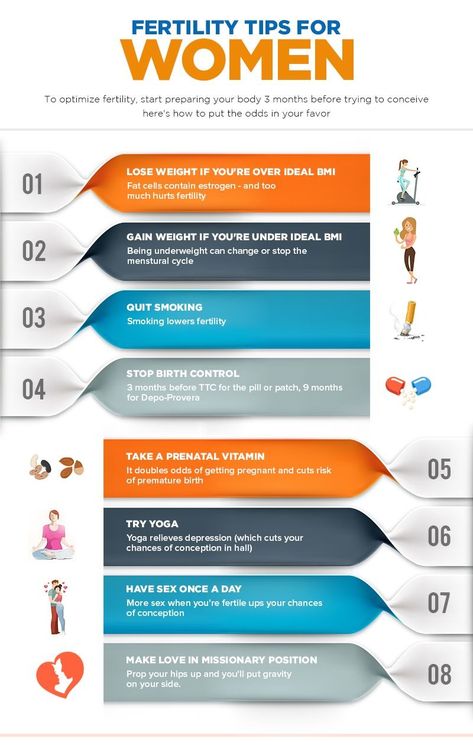

There are also a number of lifestyle changes you can make to improve your chances of becoming a dad.

Sperm temperature

Your testicles are outside your body because, to produce the best quality sperm, they need to be kept cooler than the rest of you (slightly below body temperature).

If you're planning a pregnancy, taking a few simple measures to keep your testicles cool may help. For example, if your job involves working in a hot environment, take regular breaks outside. If you sit still for long periods, get up and move around regularly.

Wearing tight underwear is also thought to increase testicle temperature by up to 1C. Although research has shown that tight underwear does not seem to affect sperm quality, you may want to wear loose-fitting underwear, such as boxer shorts, while trying for a baby.

Smoking

Smoking can reduce fertility, so you should give up smoking if you want to become a dad.

Smoking around a newborn baby also significantly increases their chances of respiratory disease and cot death (sudden infant death syndrome).

A GP will be able to give you advice and treatment to help you quit smoking.

You can also visit the NHS Smokefree website for more help and advice about quitting smoking, or you can call the helpline on 0300 123 1044 (9am to 8pm Monday to Friday, 11am to 4pm Saturday and Sunday).

Alcohol

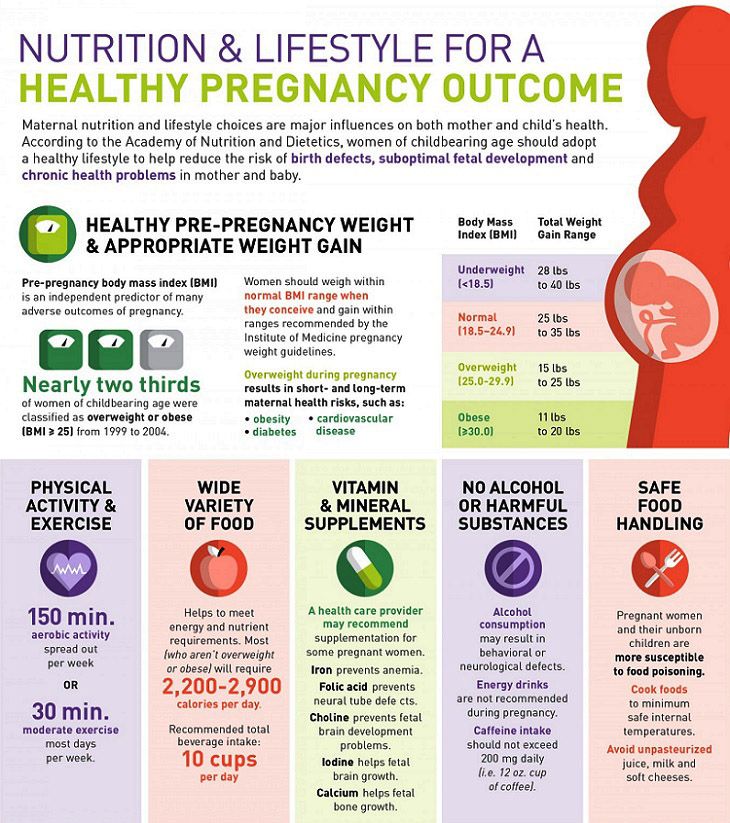

Drinking alcohol excessively can affect the quality of sperm. The UK Chief Medical Officers' recommendation is to drink no more than 14 units of alcohol a week, which should be spread evenly over 3 days or more.

One unit of alcohol is the equivalent of half a pint of beer or lager, or a single pub measure (25ml) of spirits. A small glass of wine (125ml) contains 1.5 units of alcohol.

Read more about alcohol support and alcohol units.

Recreational drugs

Some recreational drugs are known to damage sperm quality and reduce male fertility. These include:

- cannabis

- cocaine

- anabolic steroids

You should avoid taking these types of drugs if you're trying for a baby.

Medicines

Some prescription medicines and medicines you buy from a pharmacy can also affect male fertility.

For example, some chemotherapy medicines can affect fertility, either temporarily or permanently.

Long-term use of some antibiotics can also affect both sperm quality and quantity. But these effects are usually reversed 3 months after stopping the medicine.

Speak to a GP, pharmacist or other healthcare professional if you're taking a medicine and you're unsure whether it could affect your fertility.

Diet, weight and exercise

Eating a healthy, balanced diet and maintaining a healthy weight is essential for keeping your sperm in good condition.

The Eatwell Guide shows that to have a healthy diet you should:

- eat at least 5 portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables every day (see 5 A Day)

- base meals on higher fibre starchy foods like potatoes, bread, rice or pasta

- include some dairy or dairy alternatives (such as soya drinks and yoghurts)

- eat some beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other protein

Being overweight (having a body mass index above 25) may affect the quality and quantity of your sperm.

If you're overweight and trying for a baby, you should try to lose weight by combining healthy eating with regular exercise.

Stress

Stress can affect your relationship. It can also lower your or your partner's sex drive (libido), which may reduce how often you have sex.

Severe stress may also limit sperm production. So when trying to have a baby, learning to relax and taking steps to reduce the amount of stress in your life will help.

Read more about loss of libido, mental health and wellbeing and breathing exercise for stress.

Getting help

Some people get pregnant quickly, but for others it can take longer. It's a good idea to see a GP if your partner is not pregnant after a year of trying.

Further information

- How can I increase my chances of getting pregnant

- What is preconception care?

- Infertility

Page last reviewed: 15 May 2020

Next review due: 15 May 2023

Male fertility: 10 tips for men trying to conceive

(Image credit: Getty Images)Are you and your partner figuring out how to get pregnant? Although a woman will be the one who technically gets pregnant, and carries and delivers the baby, a man also has a crucial role. For fertilization to occur, his sperm must be healthy and strong to reach and penetrate the woman's egg.

For fertilization to occur, his sperm must be healthy and strong to reach and penetrate the woman's egg.

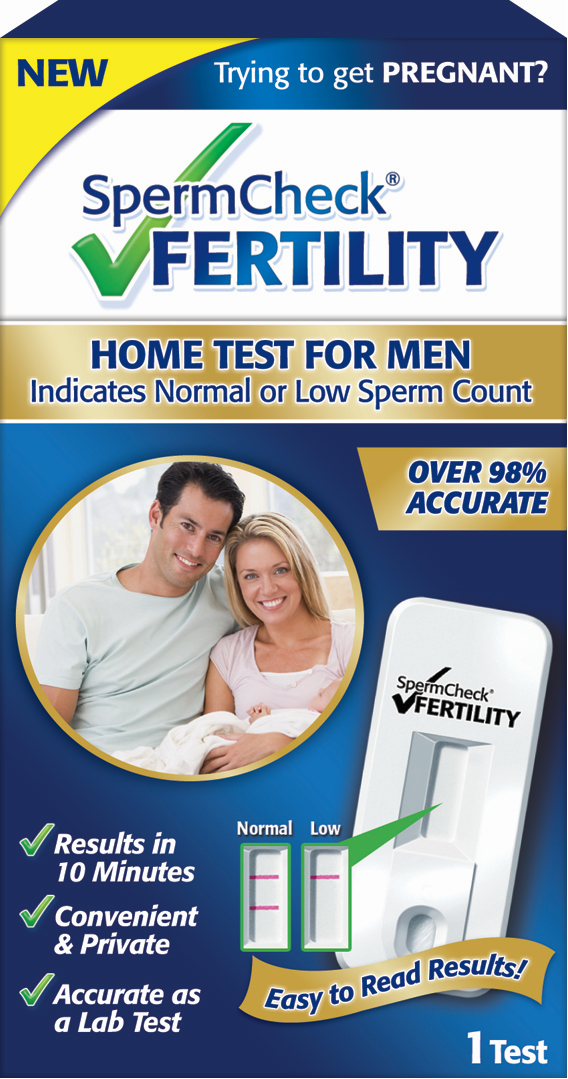

To make fertilization happen, a man must be able to have and keep an erection, have enough sperm that are the right shape and move in the right way, and have enough semen to carry the sperm to the egg, according to the Mayo Clinic . A problem in any step in this process, including male fertility, can prevent pregnancy.

A variety of factors, from genetics and lifestyle to environmental exposures and hormones, can affect a man's fertility, so it's difficult to isolate the exact cause for infertility, according to Dr. Jared Robins, chief of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Northwestern Medicine's Fertility and Reproductive Medicine in Chicago. Nonetheless, doctors identify the cause of problems in about 80 percent of infertile couples, Robins noted. When there is a known cause of infertility, problems in the male partner tend to account for about 40 percent of infertile couples, he said. But there are many steps that men can take to enhance their health, lifestyle and relationship to increase a couple's chances of conceiving. Here are 10 tips for men who want to improve their fertility.

But there are many steps that men can take to enhance their health, lifestyle and relationship to increase a couple's chances of conceiving. Here are 10 tips for men who want to improve their fertility.

1. Lose extra pounds

Losing weight can improve sperm quality. (Image credit: Getty Images)Studies have suggested that couples in which the man is overweight or obese take longer to conceive than couples with no weight problems. Research has also indicated that being overweight or obese affects a man's sperm quality, reducing sperm counts and decreasing their ability to swim, as well as increasing damage to genetic material (DNA) in sperm, according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine .

A 2012 study found that overweight and obese men were more likely to have low sperm counts or a lack of viable sperm compared with normal-weight men, possibly making it harder for these men to father a child. The researchers suspected that too much body fat was linked with changes in testosterone and other reproductive hormone levels in men.

2. Get health conditions under control

Effectively managing chronic medical conditions, such as high blood pressure and diabetes, may improve a man's chances of getting his partner pregnant, suggests The World Journal of Men’s Health . Other medical conditions, such as cystic fibrosis or varicoceles (enlarged veins in the scrotum that cause overheating), may also affect male fertility, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . In addition, some medications used to treat high blood pressure (beta blockers), depression and anxiety (SSRIs), pain (long-term opiates), and an enlarged prostate (finasteride), could have a negative influence on fertility, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Supplemental testosterone can also decrease sperm production. Some chemotherapy drugs and radiation treatments for cancer can cause permanent infertility, according to the Mayo Clinic . A man should speak to his doctor about medication he is taking and whether it might interfere with his ability to father a child.

3. Eat healthy foods

Antioxidants and fiber can improve male fertility. (Image credit: Getty Images)"The role of diet in male fertility is unclear," Robins told Live Science. Even though the science may be inconclusive, it still makes sense for men to eat a variety of healthy foods, including plenty of fruits and vegetables, which are rich sources of antioxidants that may help to produce healthy sperm. Men should also consume fiber-rich foods, healthy monounsaturated fats, and moderate amounts of lean protein.

Robins said men frequently ask him whether drinking soda can decrease their sperm counts. He tells them there's no good evidence that caffeine in soda affects men's fertility, and there's little evidence that caffeine in coffee, tea and energy drinks is linked with fertility problems in men.

4. Get regular physical activity

Robins said he encourages men to get regular exercise because it helps reduce stress, makes men feel better about themselves and benefits their long-term health. While being physically active is beneficial, according to a 2014 study, published in the journal Wilderness and Environmental Medicine , those who have a strenuous training schedule and regularly participate in endurance events may impact their levels of luteinising hormone and testosterone, impacting fertility.

While being physically active is beneficial, according to a 2014 study, published in the journal Wilderness and Environmental Medicine , those who have a strenuous training schedule and regularly participate in endurance events may impact their levels of luteinising hormone and testosterone, impacting fertility.

Related articles

Researchers have also looked at whether bike riding can affect sperm because the sport involves long periods of sitting in a position that increases scrotal temperatures as well as bouncing and vibrations that could cause trauma to the testicles. A few studies have suggested that long-distance truck drivers may also have more fertility problems for similar reasons as avid male cyclists.

One study, published in the journal Fertility and Sterility , found that men who attended fertility clinics and who reported they cycled for at least five hours a week were more likely to have low sperm counts and poor sperm motility compared to men who did other forms of exercise. However, there's little data on whether or not cycling actually impacts sperm function, Robins said.

However, there's little data on whether or not cycling actually impacts sperm function, Robins said.

5. Increase vitamin intake

Some vitamins may improve sperm quality. (Image credit: Getty Images)Robins tends to recommend that men take a daily multivitamin. "There is little likelihood of harm and some potential benefits," he said. Many multivitamin formulations for men might include antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, and the minerals selenium and zinc. Some research has found that antioxidants may cause a slight increase in sperm count and movement, according to The American Society for Reproductive Medicine. It makes sense that antioxidants may improve sperm quality because they can protect against free radicals, which can cause damage to DNA within sperm cells, Robins said.

6. Be conscious of age-related fertility changes

Similarly to women, men have a ticking biological clock, but they experience fertility declines later in life than women do, according to a 2020 article by the BBC . Research shows that as a man gets older, both the volume and quality of his semen tend to diminish. As men get older, there is also a falloff in the number of healthy sperm and their movement, and they can also have more DNA damage in their sperm.

Research shows that as a man gets older, both the volume and quality of his semen tend to diminish. As men get older, there is also a falloff in the number of healthy sperm and their movement, and they can also have more DNA damage in their sperm.

These changes could mean it might take longer for a couple to conceive. With age, there is also a greater risk for genetic abnormalities in their sperm. Random mutations in a man's sperm can pile up as the years go by, making older fathers more likely to pass on more genetic mutations to a child.

7. Stop smoking

Smoking can impact sperm quality. (Image credit: Getty Images)Smoking is linked with reduced sperm quality: Male smokers are more likely to have low sperm counts and decreased sperm movement, and they have higher numbers of abnormally-shaped sperm, according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine .

Marijuana and other recreational drug use, including anabolic steroids for bodybuilding, should also be avoided because some studies suggest they may also negatively impact sperm production, Robins said.

8. Boxers or briefs?

"This is everyone's favorite question," Robins said. But there's not a lot of science to suggest that switching from briefs to boxers improves a couple's chances of getting pregnant. Although a man's underwear choice may affect his scrotal temperature and reduce sperm quality, most studies have demonstrated no real difference between boxers and briefs in terms of their impact on male fertility, Robins said.

A 2016 study found that it really didn't make much difference whether men wore boxers or briefs or went commando on a couple's ability to conceive or on a man's semen quality, suggesting that it's best for men to wear whatever feels most comfortable to them when a couple wants to have a baby.

9. Beware of the heat

Heat can temporarily lower sperm numbers (Image credit: Getty Images)Frequent visits to and long stays in hot tubs, saunas and steam rooms could increase scrotal temperatures, which may decrease sperm counts and sperm quality. But this heat exposure does not have a permanent impact on sperm, Robins said. Reduced sperm counts may only be temporary and could return to normal in a few months once a man stops going into a hot tub or sauna.

But this heat exposure does not have a permanent impact on sperm, Robins said. Reduced sperm counts may only be temporary and could return to normal in a few months once a man stops going into a hot tub or sauna.

A 2011 study about men using laptops received plenty of media coverage when it reported that men who placed the computers on their laps may be more likely to have damaged sperm and decreased sperm motility. But these conclusions were "jumping the gun," Robins said. It's unclear how much time the men spent with the laptop in close proximity to their testicles, he explained, and it's also unclear whether the effects may have been caused by heat or if they resulted from radiation due to the use of a wireless connection.

10. Know when to get help

Infertility is defined as the inability of a sexually active couple who are not using birth control to get pregnant after one year of trying, according to The American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Robins said he tells couples that a woman who is under the age of 35 and her partner should try to become pregnant for one year without success before seeking an infertility evaluation. For women who are 35 or older, the time before seeing an infertility specialist shortens to 6 months in couples who are having sex regularly without using birth control, he noted.

Robins said he tells couples that a woman who is under the age of 35 and her partner should try to become pregnant for one year without success before seeking an infertility evaluation. For women who are 35 or older, the time before seeing an infertility specialist shortens to 6 months in couples who are having sex regularly without using birth control, he noted.

Additional resources

For more information about how to improve male fertility and how to get help, head to the U.K. National Health Service website . You can read about male reproduction in more detail in the Encyclopedia of Reproduction .

Bibliography

"Hypertension and Male Fertility". The World Journal of Men's Health (2017). https://synapse.koreamed.org/articles/1088840

"The Impact of an Ultramarathon on Hormonal and Biochemical Parameters in Men". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine (2014). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1080603214001021

"Physical activity and semen quality among men attending an infertility clinic". Fertility and Sterility (2011). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0015028210027767

Fertility and Sterility (2011). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0015028210027767

"Smoking and Infertility". The American Society for Reproductive Medicine. https://www.reproductivefacts.org/globalassets/asrm/asrm-content/learning--resources/patient-resources/protect-your-fertility3/smoking_infertility.pdf

This article is for informational purposes only, and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ailsa is a staff writer for How It Works magazine, where she writes science, technology, history, space and environment features. Based in the U.K., she graduated from the University of Stirling with a BA (Hons) journalism degree. Previously, Ailsa has written for Cardiff Times magazine, Psychology Now and numerous science bookazines. Ailsa's interest in the environment also lies outside of writing, as she has worked alongside Operation Wallacea conducting rainforest and ocean conservation research.

Preparing a man for conception - clinic "Family Doctor".

- Home >

- About clinic >

- Publications >

- Preparing a man for conception

Preparation for conception is necessary for both a woman and a man. This is because the child receives 50% of the genetic material from each parent. So, for the birth of a healthy child, his parents must be healthy. nine0013

Many factors can affect the male reproductive system. First of all, bad habits should be mentioned, which include smoking and alcohol abuse, as well as constant stress and chronic lack of sleep. It is also the presence of sexually transmitted infections, exacerbation of chronic prostatitis, hormonal disorders, taking certain medications and steroids, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, overheating of the groin and perineum, etc. nine0013

When planning a conception, a man needs to exclude the impact of all of the above factors in three months and cure diseases and infections, because. the full cycle of sperm renewal takes three months.

the full cycle of sperm renewal takes three months.

What can you do to improve the quality of your sperm = the genetic material of your unborn child?

1. Remember that sperm do not like overheating. Therefore, it is advisable to cancel visits to baths and saunas, to keep the seat heating in the car turned on for too long. nine0015 2. Reduce weight if you are obese. For men, a waist circumference in centimeters (at the level of the navel) over 94 cm = obese. In adipose tissue, testosterone is converted to estrogens, many inflammatory factors are produced, and this can also lead to type 2 diabetes, etc. Which, as you understand, are not the best companions for easily injured sperm!

3. Exclude sugary carbonated drinks, dyes, trans fats, confectionery from the diet. nine0015 4. Do not abuse alcohol. Alcohol, in addition to a direct toxic effect on spermatozoa, reduces the body's ability to absorb zinc, which is necessary for normal spermatogenesis.

5. Stop smoking. According to numerous studies, up to 50% of couples suffering from idiopathic infertility, after stopping smoking, find a long-awaited baby.

6. Try to be less nervous and sleep more.

7. Do not take medicines without a doctor's prescription (many drugs can significantly impair sperm quality). From here follows the rule: treat your chronic diseases before the moment of pregnancy planning. nine0015

In order to understand how fertile you are, you need to come to a consultation with a urologist-andrologist. It is advisable to have at least a spermogram with you. The rest of the list of examinations will be consulted by a doctor of the aforementioned specialty. It is better for a married couple to undergo an examination in parallel so that the treatment does not work out late, because. after the age of 35, a woman loses the ability to bear children faster than a man, and many couples miss the moment just because the man does not want to visit medical institutions. nine0013

nine0013

To make an appointment with a specialist, call the single contact center in Moscow +7 (495) 775 75 66, fill out the online appointment form or contact the receptionist of the Family Doctor clinic.

Return to the list of publications

Physicians

About doctor Record

Annenkov Andrey Viktorovich

urologist, PhD

Clinic on Novoslobodskaya

Clinic on Usacheva

Clinic on Ozerkovskaya

About doctor Record

top

Is male pregnancy possible in nature? — T&P

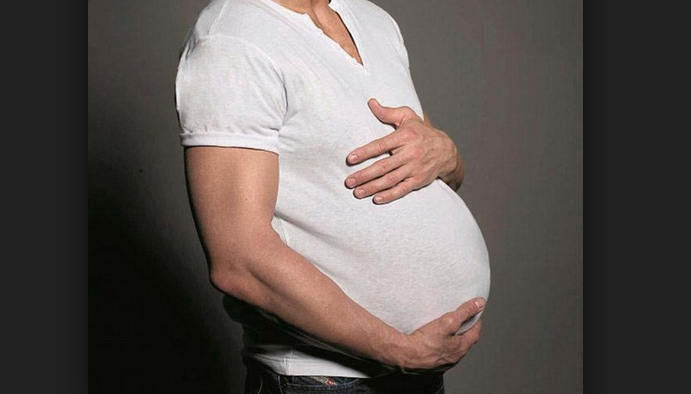

The most famous example of “male pregnancy” is still the story of Thomas Beaty, a transgender man who retained his uterus and gave birth to three children.

For several decades, biomedical scientists have been looking for ways that will allow a man to endure and give birth to a child without a sex change. This could be a new solution to the problem of infertility, and would also truly equalize men and women in rights. The Ivan Limbakh Publishing House publishes a book by sociologist Irina Aristarkhova "Hospitality of the Matrix: Philosophy, Biomedicine, Culture" translated by Daniil Zhayvoronok, which deals with the problems of new reproductive practices and gender identity. T&P publishes an excerpt about whether men need the function of childbearing and how close the world is to such a turn. nine0110

For several decades, biomedical scientists have been looking for ways that will allow a man to endure and give birth to a child without a sex change. This could be a new solution to the problem of infertility, and would also truly equalize men and women in rights. The Ivan Limbakh Publishing House publishes a book by sociologist Irina Aristarkhova "Hospitality of the Matrix: Philosophy, Biomedicine, Culture" translated by Daniil Zhayvoronok, which deals with the problems of new reproductive practices and gender identity. T&P publishes an excerpt about whether men need the function of childbearing and how close the world is to such a turn. nine0110

Biomedical Discourse of Male Pregnancy

Matrix Hospitality: Philosophy, Biomedicine, Culture

Over the past two decades, some eminent and eminent biomedical experts in various parts of the world have been explaining the feasibility of male pregnancy or taking it seriously (Walters 1991; Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998; Winston 1998; Gosden 2000). From a biomedical point of view, male pregnancy can be understood as another form of ectogenesis. As the long history of supporting ectogenetic research shows, male pregnancy is also seen as a solution to the problem of infertility and, increasingly and more specifically, as an issue of the legal rights of men (especially homosexual and transgender men) to reproduce. William Walters, Executive Clinical Director at the Royal Melbourne Women's Hospital and co-author of a book with Peter Singer (1982), is a prominent proponent of ectogenesis. Walters specializes in transsexuality and describes those who may be interested in male pregnancy: “[Biological males] expressing an interest or strong desire to have a child of their own include (i) transgender men who have become women, (ii) homosexuals in a monogamous relationship , (iii) single heterosexual males with strong maternal instincts, and (iv) married males whose wives are infertile or fertile but have serious health conditions that are unfavorable for childbearing” (Walters 1991, 739).

From a biomedical point of view, male pregnancy can be understood as another form of ectogenesis. As the long history of supporting ectogenetic research shows, male pregnancy is also seen as a solution to the problem of infertility and, increasingly and more specifically, as an issue of the legal rights of men (especially homosexual and transgender men) to reproduce. William Walters, Executive Clinical Director at the Royal Melbourne Women's Hospital and co-author of a book with Peter Singer (1982), is a prominent proponent of ectogenesis. Walters specializes in transsexuality and describes those who may be interested in male pregnancy: “[Biological males] expressing an interest or strong desire to have a child of their own include (i) transgender men who have become women, (ii) homosexuals in a monogamous relationship , (iii) single heterosexual males with strong maternal instincts, and (iv) married males whose wives are infertile or fertile but have serious health conditions that are unfavorable for childbearing” (Walters 1991, 739).

Currently, abdominal pregnancy and uterine transplantation are considered to be the main ways to achieve human male pregnancy in the future. It is worth noting that both of these possibilities treat pregnancy as a matter of "where" - that is, finding a suitable place to introduce a fertilized embryo into a male body. This problem is often presented as a major impediment to male pregnancy, reinforcing the understanding of the womb/womb as "just a smart incubator", as Gosden puts it, that could easily be replaced. Before we take a closer look at both of these possibilities for human male pregnancy, I will briefly outline the current state of biomedical research regarding this issue. nine0013

Teresi and Mcauliffe (1998) collected extensive information on Australian, New Zealand and British studies of male pregnancy in animals. It is important to note that most of these studies derive their justification from references to the benefits of biomedicine, which have nothing to do with male pregnancy, but rather deal with problems of embryonic development, evolutionary biology, fertility treatment, and so on. These examples, however, support my contention that the main question of pregnancy remains the question of where: where can a male baboon or mouse embryo be implanted and how long can that embryo survive inside the abdominal cavity without being expelled or reabsorbed. Spatial restrictions for the placement and development of the embryo, observed in animals, are given as one of the objections to the possibility of male pregnancy: “It is obvious. The placental sac and the baby at term will weigh about twenty-five pounds. And during all the months of growth, this bag can twist and turn” (Hallatt, cited in: Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 180). Despite these limitations, a male baboon carried an implanted embryo for four months, according to Dr. Jacobsen, a renowned fertility specialist credited with developing amniocentesis to check for genetic abnormalities. Jacobsen concludes that "the miracle of our discovery" was the realization that "a fertilized egg can be autonomous, producing all the hormones it needs for development" (Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 177).

These examples, however, support my contention that the main question of pregnancy remains the question of where: where can a male baboon or mouse embryo be implanted and how long can that embryo survive inside the abdominal cavity without being expelled or reabsorbed. Spatial restrictions for the placement and development of the embryo, observed in animals, are given as one of the objections to the possibility of male pregnancy: “It is obvious. The placental sac and the baby at term will weigh about twenty-five pounds. And during all the months of growth, this bag can twist and turn” (Hallatt, cited in: Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 180). Despite these limitations, a male baboon carried an implanted embryo for four months, according to Dr. Jacobsen, a renowned fertility specialist credited with developing amniocentesis to check for genetic abnormalities. Jacobsen concludes that "the miracle of our discovery" was the realization that "a fertilized egg can be autonomous, producing all the hormones it needs for development" (Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 177). Jacobsen also reported a successful abdominal pregnancy in a male chimpanzee (Andrews 1984, 261). A pregnant male mouse carried a fetus in her testicles for twelve days until “perfect condition,” adds David Kirby of Oxford University, and only the lack of elasticity and space inside the testicles stopped the development of the embryo (Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 177). With successful implantation and gestation in the male baboon and mouse, Harding concludes, like Jacobsen, "hormonally, the embryo is completely autonomous" (Harding, cited in Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 179). This means that a human male does not even have to undergo hormone therapy in order to become pregnant. Once the placenta develops, the "autonomous" creature will produce its own steroids on its own.

Jacobsen also reported a successful abdominal pregnancy in a male chimpanzee (Andrews 1984, 261). A pregnant male mouse carried a fetus in her testicles for twelve days until “perfect condition,” adds David Kirby of Oxford University, and only the lack of elasticity and space inside the testicles stopped the development of the embryo (Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 177). With successful implantation and gestation in the male baboon and mouse, Harding concludes, like Jacobsen, "hormonally, the embryo is completely autonomous" (Harding, cited in Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 179). This means that a human male does not even have to undergo hormone therapy in order to become pregnant. Once the placenta develops, the "autonomous" creature will produce its own steroids on its own.

The biomedical community thus assumes that if male pregnancy is ever possible, it will take place in the abdominal cavity. There is practically no discussion about the effect on surrounding organs. When it comes to pregnancy, the male body, like the female body, comes to be seen as a passive "bag of tissue" and an empty space just waiting to be filled through in vitro fertilization or some other type of assisted reproductive technology. The possibility of abdominal pregnancy in men is based not only on the limited number of male pregnancies in animals, but also on successful abdominal (i.e. ectopic) pregnancies in women. Abdominal pregnancies in women occur outside of their "place" they are supposed to, that is, they are ectopic. Today, most researchers are calling for a "wait and see" approach to ectopic pregnancies in previously infertile women or those who have passed the placental fixation stage without complications, "because it is impossible to predict which of the spontaneous abdominal pregnancies will develop in a relatively favorable way in order to produce a normal, healthy baby, the expectant approach to all abdominal pregnancies can be argued, especially when the carrier has a long history of infertility" (Walters 1991, 738-739).

There is practically no discussion about the effect on surrounding organs. When it comes to pregnancy, the male body, like the female body, comes to be seen as a passive "bag of tissue" and an empty space just waiting to be filled through in vitro fertilization or some other type of assisted reproductive technology. The possibility of abdominal pregnancy in men is based not only on the limited number of male pregnancies in animals, but also on successful abdominal (i.e. ectopic) pregnancies in women. Abdominal pregnancies in women occur outside of their "place" they are supposed to, that is, they are ectopic. Today, most researchers are calling for a "wait and see" approach to ectopic pregnancies in previously infertile women or those who have passed the placental fixation stage without complications, "because it is impossible to predict which of the spontaneous abdominal pregnancies will develop in a relatively favorable way in order to produce a normal, healthy baby, the expectant approach to all abdominal pregnancies can be argued, especially when the carrier has a long history of infertility" (Walters 1991, 738-739). The wording is important here: instead of focusing on the prevalence of failures, life-threatening cases, the focus has shifted to a relatively small number of successful cases, which paves the way for the biomedical future of male pregnancy.

The wording is important here: instead of focusing on the prevalence of failures, life-threatening cases, the focus has shifted to a relatively small number of successful cases, which paves the way for the biomedical future of male pregnancy.

For Roger Gosden, another researcher who seriously considers human male pregnancy, it is a distinct, if risky, possibility (Gosden 2000, 193–197). Gosden offers various grounds for male pregnancy: the father may be the recipient of the fetus until the mother's uterus is ready to receive it; male pregnancy can replace a surrogate or artificial pregnancy, which will mean lower costs and resolution of legal problems; it will bind the child and the father at a very early stage of development. Gosden, however, concludes that at present, "given the availability of safe alternatives, there is no need to construct an ectopic male pregnancy," where "safe alternatives" refers to traditional maternal pregnancy. Concerns about the safety of male pregnancy are notable, as Gosden seems to view father involvement in childbearing as highly scientifically probable. In his work, he also shows that the lack of research in this area in comparison with ectogenesis (its other species) is more the result of a "cultural gap" that refuses to recognize its possibility than a biological improbability: apparently, to get funding for the study of ectogenetic systems, even as far-flung and futuristic as male pregnancy, it is much easier than to study male pregnancy as such (Gosden 2000, 193–197).

In his work, he also shows that the lack of research in this area in comparison with ectogenesis (its other species) is more the result of a "cultural gap" that refuses to recognize its possibility than a biological improbability: apparently, to get funding for the study of ectogenetic systems, even as far-flung and futuristic as male pregnancy, it is much easier than to study male pregnancy as such (Gosden 2000, 193–197).

Walters, one of the early advocates of the possibility of male pregnancy, when discussing biomedical alternatives to infertility, seriously considers abdominal pregnancy for women: “Due to the possibility of abdominal pregnancy to end in the birth of a normal healthy child, it is understandable that some well-informed infertile couples consider this method of childbirth as solutions to their problems... There is no doubt that artificially induced abdominal pregnancy has legal and psychological benefits for infertile women who would otherwise have to consider surrogacy. In this way, her (the couple. - I. A.) understandable anxiety about the surrogate mother giving up the child at birth will be eliminated ”(Walters 1991, 733, 737).

In this way, her (the couple. - I. A.) understandable anxiety about the surrogate mother giving up the child at birth will be eliminated ”(Walters 1991, 733, 737).

The "site" commonly cited as suitable for implantation in the abdominal cavity is the omentum (one of the tissue folds of the peritoneum, a membrane that supports and envelops the organs of the peritoneum), since it seems impractical to allow a fertilized embryo to wander around the body. The human embryo needs to be immersed in tissues rather than superficially attached to them (it is noteworthy that implantation in humans is deeper than in other animals). Therefore, the omentum is chosen as a place where it can be implanted, where the blood supply and placenta can be developed and growth is ensured. Since men may not provide the necessary amount of hormones for the successful development of the embryo, they may need to undergo hormone therapy. In addition to many other drugs that correct their bodies to facilitate this process, they may need immunosuppressants, especially in the period before the placenta is fully developed. As previously shown in the case of male pregnancy in animals, the researchers believe that this should not be a big problem, since, they argue, the embryo in the first weeks of its development is more or less a self-sufficient creature. And just as it develops outside the body after artificial insemination and before implantation, the same will happen inside a man. Another possibility is that the embryo, once contact with the male body is established, will facilitate the production of the necessary hormones, just as it does in the female body through the placental surface. nine0013

Male Pregnancy Project 1999-2002 Li Mingwei and Virgil Wong

The second option for male pregnancy is transplantation, and is based on animal and human uterine transplantation studies (Altchek 2003; Bedaiwy et al. 2008 ; Gauthier et al. 2008). One of the notable characteristics of uterine transplantation is that researchers present and treat it as a rare temporary transplant, as the uterus is not a vital organ, unlike the liver, kidney, and even the eyes. This means that after the baby is born, the uterus can be removed. In addition, due to hysterectomy, human wombs are almost constantly "available" and can be used relatively "cheaply". Gosden suggests that transplanting the uterus into the father's body would be beneficial for the baby, as the dense uterine walls provide a "safe" environment, and the risk of abnormalities in ectopic births exceeds 50 percent (Gosden 2000, 196). It is well known that the relative utility of uterine transplant research stems from the fact that not all cultural and religious contexts consider surrogacy or assisted reproduction acceptable. For example, one famous attempt at uterine transplantation was carried out in Saudi Arabia, and some argue that this is not surprising given the negative cultural attitudes towards surrogacy and assisted reproduction (Fageeh et al. 2002). Since women with ovaries, as well as women with ovarian tissues, benefit from ovarian tissue transplantation and in vitro fertilization in the postmenopausal period, there is agreement among biomedical scientists that it is only a matter of time before the uterus is transplanted into the woman and the embryo is implanted.

This means that after the baby is born, the uterus can be removed. In addition, due to hysterectomy, human wombs are almost constantly "available" and can be used relatively "cheaply". Gosden suggests that transplanting the uterus into the father's body would be beneficial for the baby, as the dense uterine walls provide a "safe" environment, and the risk of abnormalities in ectopic births exceeds 50 percent (Gosden 2000, 196). It is well known that the relative utility of uterine transplant research stems from the fact that not all cultural and religious contexts consider surrogacy or assisted reproduction acceptable. For example, one famous attempt at uterine transplantation was carried out in Saudi Arabia, and some argue that this is not surprising given the negative cultural attitudes towards surrogacy and assisted reproduction (Fageeh et al. 2002). Since women with ovaries, as well as women with ovarian tissues, benefit from ovarian tissue transplantation and in vitro fertilization in the postmenopausal period, there is agreement among biomedical scientists that it is only a matter of time before the uterus is transplanted into the woman and the embryo is implanted. and delivered on time. Thus, in this case, the rationale is that if a woman or a female animal is capable of this, then so is a man. It is noteworthy that the scientific language describes both of these problems in a very straightforward manner, which serves to increase the biomedical possibility of male pregnancy. The womb transplant is described as: medicate, inject, cut, remove, mix, grow, remove, inject, medicate, bear, cut, and become a mother. The male body is just another abdominal cavity, a simple implantation incubator. nine0013

and delivered on time. Thus, in this case, the rationale is that if a woman or a female animal is capable of this, then so is a man. It is noteworthy that the scientific language describes both of these problems in a very straightforward manner, which serves to increase the biomedical possibility of male pregnancy. The womb transplant is described as: medicate, inject, cut, remove, mix, grow, remove, inject, medicate, bear, cut, and become a mother. The male body is just another abdominal cavity, a simple implantation incubator. nine0013

However, many problems and complications surround both abdominal and womb transplant pregnancy. Just as in the case of abdominal pregnancy in women, the risk to the life of a pregnant man will be great. The vast majority of ectopic pregnancies end in surgery, provided that such a pregnancy is detected at an early stage and the operation is still possible. Otherwise, an ectopic pregnancy can be fatal. Other common complications are genetic abnormalities, developmental disorders and, if the child survives, a significantly reduced quality of life. Since the child is limited by adjacent organs, the head and body may not form properly. However, again we are told that since there are cases of healthy, normal children being born as a result of ectopic pregnancies, there is a (however small) possibility of successful pregnancy in men (Walters 1991). Most of the proponents of male pregnancy cited here (Gosden 2000; Walters 1991) refer to it as stemming from the needs of men who have "strong maternal instincts" and exhibit "effeminate" behavior - as "transgender", "feminine" or hormonalized during pregnancy. . These perspectives once again reveal pregnancy as a maternal attitude (even when discussing male pregnancy) and an attitude of hospitality. Thus, apart from the need for internal tissues "like a womb" (like an omentum), or the need for a uterine transplant, that is, apart from searching for an "empty space" inside the male body, the idea of male pregnancy has the potential to change, thanks to the mother's attitude of hospitality and that what this attitude makes possible is the perception of what it means to be a man.

Since the child is limited by adjacent organs, the head and body may not form properly. However, again we are told that since there are cases of healthy, normal children being born as a result of ectopic pregnancies, there is a (however small) possibility of successful pregnancy in men (Walters 1991). Most of the proponents of male pregnancy cited here (Gosden 2000; Walters 1991) refer to it as stemming from the needs of men who have "strong maternal instincts" and exhibit "effeminate" behavior - as "transgender", "feminine" or hormonalized during pregnancy. . These perspectives once again reveal pregnancy as a maternal attitude (even when discussing male pregnancy) and an attitude of hospitality. Thus, apart from the need for internal tissues "like a womb" (like an omentum), or the need for a uterine transplant, that is, apart from searching for an "empty space" inside the male body, the idea of male pregnancy has the potential to change, thanks to the mother's attitude of hospitality and that what this attitude makes possible is the perception of what it means to be a man. nine0013

nine0013

In summary, biomedical experts who view male pregnancy as the outcome and next (logical?) step of their own practice place it in the same rubric as research on uterine transplantation and preterm birth, while agreeing that bioethically is a much more complex issue. It has become much more relevant and openly discussed in homosexual and transgender communities (Walters 1991; Sparrow 2008). Although Gosden never mentions homosexuality and suggests male pregnancy as a solution to the heterosexual family's problems with fulfilling it natural when a woman is unable or unwilling to bear a child herself, in other discourses, the terminology of reproductive "rights" and "freedoms" for homosexual and transgender men has significantly influenced this discussion, shifting the emphasis from sacred duty or pre-established need in nuclear heterosexual reproduction to the right to have a child for men.

Bioethical discourses on the possibility of male pregnancy

In the bioethical literature, the problem of male pregnancy is associated with the discourse of the "right" to receive additional reproductive services. The logic here is simple: if we spend so much time and effort helping women who would otherwise not be able to conceive and bear children, then we need to help men too. Assisted reproductive technologies should not discriminate against anyone: neither the poor nor the rich; neither healthy nor sick or people with developmental features; neither white nor non-white; neither women nor men. This argument seems to be quite valid, especially in cases where those who wish to receive such services must pay for them out of their own pocket, thus reinforcing the individual right to "autonomy" and "freedom of choice". nine0013

The logic here is simple: if we spend so much time and effort helping women who would otherwise not be able to conceive and bear children, then we need to help men too. Assisted reproductive technologies should not discriminate against anyone: neither the poor nor the rich; neither healthy nor sick or people with developmental features; neither white nor non-white; neither women nor men. This argument seems to be quite valid, especially in cases where those who wish to receive such services must pay for them out of their own pocket, thus reinforcing the individual right to "autonomy" and "freedom of choice". nine0013

Another justification for male pregnancy in bioethics is the market economic model. According to this logic, male pregnancy, like other assisted reproductive services, will be a normal business model doing some work for families and individuals, just like an adoption agency and an assisted reproduction clinic. Currently, unmarried men can pay for surrogacy services in some US states. Both Walters (1991) and Gosden (2000) argue that male pregnancy can reduce the number of complications (especially emotional, legal, and financial) associated with surrogacy. If an unmarried woman (gay or not) wishes to receive in vitro fertilization (IVF) services using frozen sperm to have children of her own, then she can do so, and a man whose desire to have a biological child in this system is guaranteed through egg donation and surrogacy (considering, of course, that he is quite wealthy and IVF will work for a surrogate mother), can also receive such a service. nine0013

Both Walters (1991) and Gosden (2000) argue that male pregnancy can reduce the number of complications (especially emotional, legal, and financial) associated with surrogacy. If an unmarried woman (gay or not) wishes to receive in vitro fertilization (IVF) services using frozen sperm to have children of her own, then she can do so, and a man whose desire to have a biological child in this system is guaranteed through egg donation and surrogacy (considering, of course, that he is quite wealthy and IVF will work for a surrogate mother), can also receive such a service. nine0013

The Male Pregnancy Project 1999–2002 Lee Mingway and Virgil Wong

Although the definitions of feminine and masculine are becoming more and more complex in biomedical and bioethical discourses, they still rest, interestingly enough, on the fact that which is regarded as the "science" of "sexual differentiation". The legal terminology pertaining to it has shifted from primary and secondary "sexual characteristics" such as penis/testicles and uterus/vagina/breasts to "masculine behaviour", "biological male" and "chromosomal male" (Walters 1991, 199; Sparrow 2008). Each new definition seeks to overcome the shortcomings found in the previous one. The problem with definitions usually comes up when economic, political, and health inequalities are recognized for transgender, transgender, biogender, bisexual, intergender, intersex, and homosexual communities and individuals (Roscoe 1991).

Each new definition seeks to overcome the shortcomings found in the previous one. The problem with definitions usually comes up when economic, political, and health inequalities are recognized for transgender, transgender, biogender, bisexual, intergender, intersex, and homosexual communities and individuals (Roscoe 1991).

Sparrow (2008) wrote an excellent essay that takes male pregnancy seriously from a bioethical perspective. However, despite Sparow's recognition of legal, economic, and medical inequalities, his main bioethical argument against male pregnancy is still based on the notion of biology as "destiny." Thus, according to Sparow, the suggestion that men have the right to be pregnant is a mockery of the "natural order of things," especially since some women want but cannot get pregnant. However, such a claim, in turn, undermines women's claim to these technologies as their "natural" right in addition to their "cultural" rights. Therefore, Sparow argues, such reasoning is a perversion of the concept of "reproductive freedom" and "rights" and makes a joke of women's rights, especially since male pregnancy is not based on "normal human life cycle" "reproductive biology facts" or "normal reproduction context" and is a "frivolous or banal project" (Sparrow 2008, 287). His argument against male pregnancy reveals that women's claims to a fundamental "right" to assisted reproduction are often based on cultural or political arguments—even if "nature" is used to support them—and argues for women's specific rights at the expense of other groups. (including animals). When it comes to men, however, the social and collective needs and contexts surrounding pregnancy are invoked, and the "collective" and "social" are favored over individual rights to pregnancy (Squier 1995).

His argument against male pregnancy reveals that women's claims to a fundamental "right" to assisted reproduction are often based on cultural or political arguments—even if "nature" is used to support them—and argues for women's specific rights at the expense of other groups. (including animals). When it comes to men, however, the social and collective needs and contexts surrounding pregnancy are invoked, and the "collective" and "social" are favored over individual rights to pregnancy (Squier 1995).

As Walters (1991) points out, along with others, the biggest beneficiaries of IVF and assisted reproductive medicine research are (white) affluent women. Squier (1994 and 1995) also notes that we often forget that current biomedical research is not politically and culturally neutral. Therefore, Sparow's argument that male pregnancy is not is a normal reproductive context and therefore should not be supported is untenable, as the same charge can be leveled against current biomedical research on infertility in general: a significant amount of scientific and government resources are directed to support the treatment of infertility in privileged women, who, in turn, can support such research through social, cultural and political pressure on the relevant institutions.