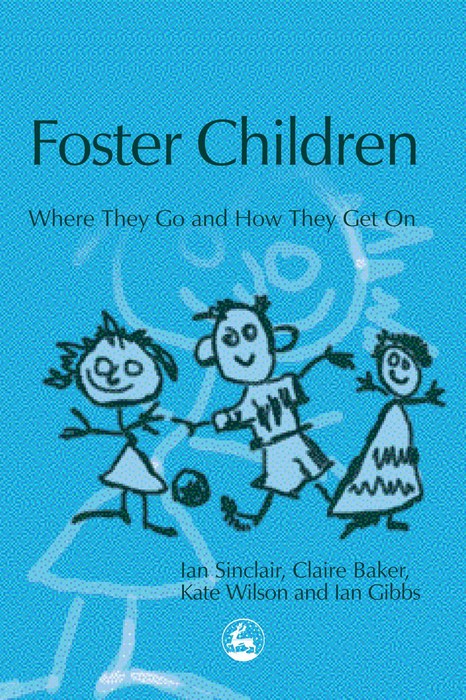

How to foster a child in ireland

Fostering

Introduction

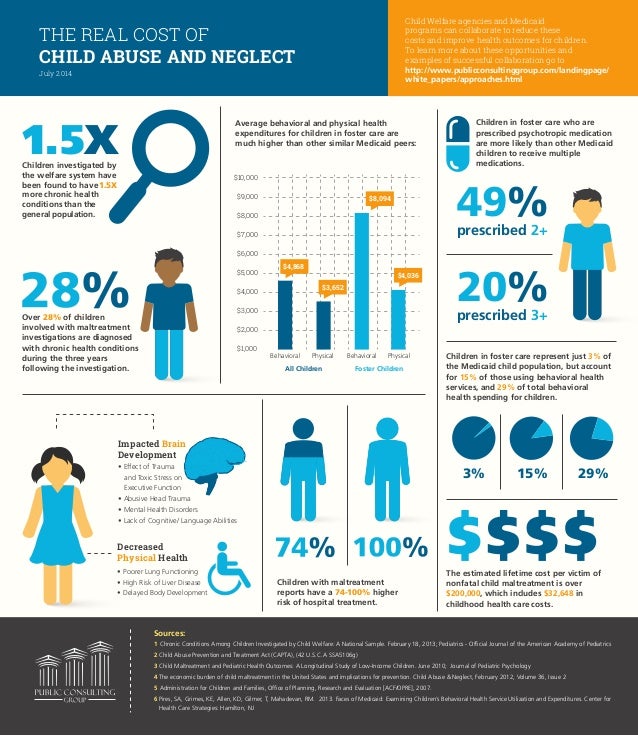

Fostering means taking care of someone else's child in your own home. Sometimes a child cannot live with their own family, either on a short-term or long-term basis. This could be because of illness in the family, the death of a parent, neglect, abuse or violence in the home. Sometimes it can be because the parent or family is not coping. It is always the goal that a child placed in foster care will return to their own family as soon as they can, if possible. Young people up to the age of 18 can be fostered.

Foster care in Ireland is governed by the Child Care Act 1991 and the Child Care (Placement of Children in Foster Care) Regulations 1995, as amended. In addition, the National Standards for Foster Care, 2003 (pdf) ensure that foster care placements are adequately supported and that children in foster care are receiving the best possible care.

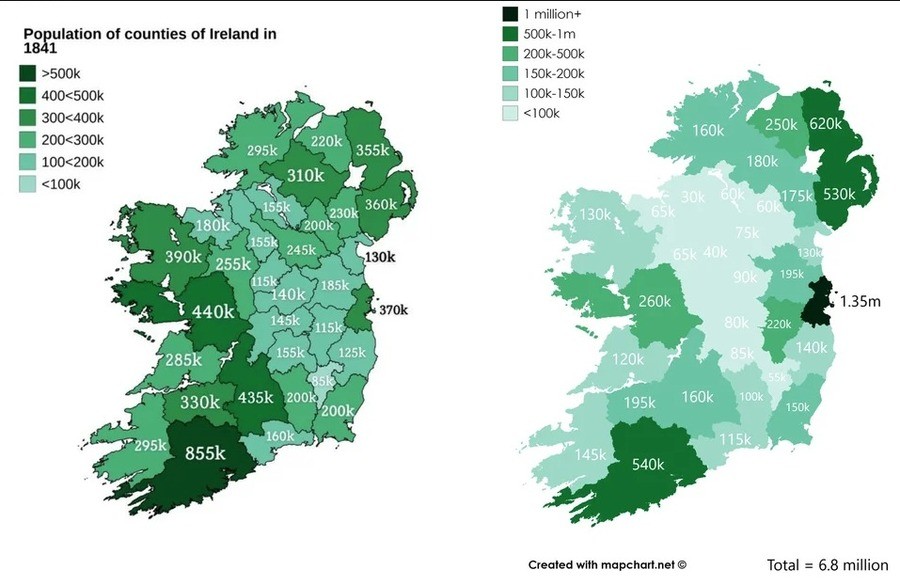

In May 2020, 65% of children in care were in general foster care, 26% were in relative foster care, 7% were in residential care and 2% in other care placements.

The role of Tusla

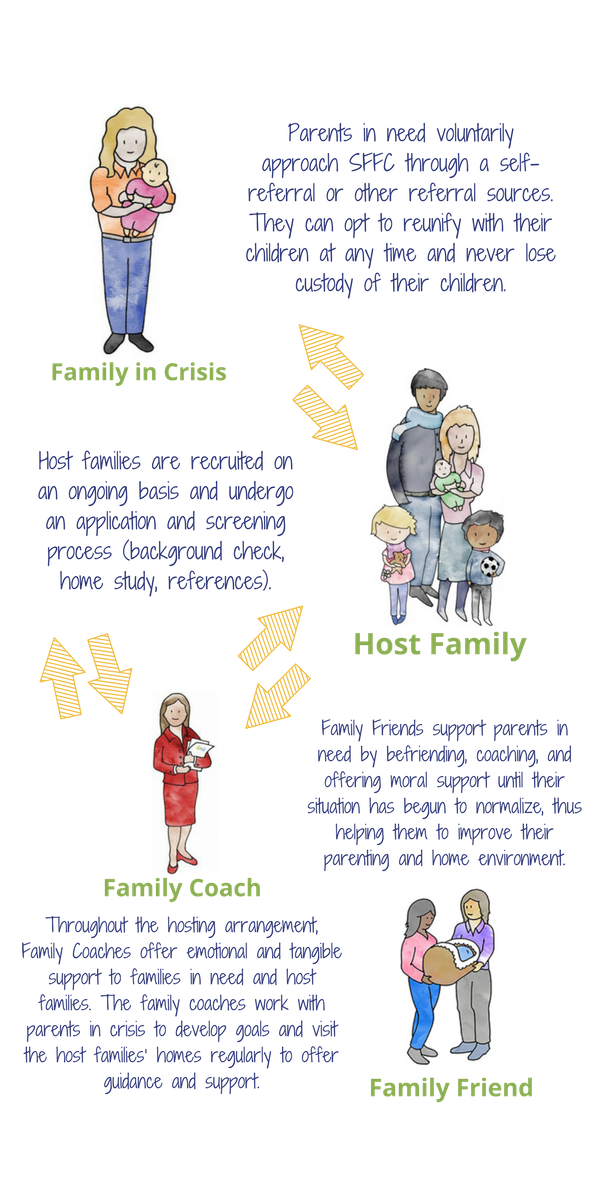

Tusla, the Child and Family Agency, assesses, recruits and trains foster families according to the needs of the area. Tusla also places children with foster families who have been recruited and trained by non-statutory agencies. Tusla is a non-statutory agency responsible for each child in care. Tusla may also provide support to the foster family.

Each foster child has their own social worker who monitors the growth and development of the child, and ensures that the best interests of the child are always the priority. Each foster family also has its own social worker, who may have helped assess the family as suitable to foster children and who will support the family throughout the foster term. An important part of the social worker's role is to develop the relationship between the foster child and the foster family and between the foster child and their own family.

Fostering a child differs from adoption because a child in foster care always remains a permanent part of their own family. Tusla is responsible for the child and the foster parents do not have guardianship.

Tusla is responsible for the child and the foster parents do not have guardianship.

Placing a child in foster care

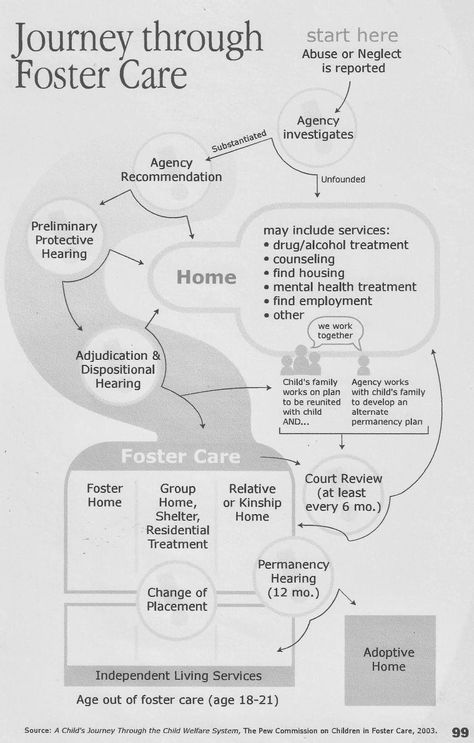

Children can be placed in foster care in 2 ways:

- Voluntarily: When a parent or family asks Tusla for help, and/or

- Court order: When a judge decides that it is in the best interests of the child to be placed in the care of Tusla.

When a child is placed in foster care, Tusla assigns responsibility for the child to a social worker. Based on the child's needs and circumstances, Tusla makes a decision on the type of fostering that is most suitable for the child.

Types of foster care

There are several types of foster care that can be provided by general or relative foster carers, such as short-term and long-term care. Foster care can also include emergency, day, respite, private, high support or other forms of foster care.

Relative foster care

Relative foster care is when a person such as a family member, family friend or neighbour becomes the foster parent of the child. Normally, a relative foster carer is a person with whom the child or the child’s family has had a relationship prior to the child’s admission to care. A relative foster carer is assessed by Tusla in the same way as all other foster parents.

Normally, a relative foster carer is a person with whom the child or the child’s family has had a relationship prior to the child’s admission to care. A relative foster carer is assessed by Tusla in the same way as all other foster parents.

In making a decision about a relative becoming foster parent to the child, Tusla will consider what is in the best interest of the child. Assessment will also take into account the needs of the child and the abilities and suitability of the relative foster carer to be a foster parent.

At the end of May 2020, 26% of children in care were living with a relative foster carer.

General foster care

When Tusla cannot find a suitable relative, or person known to the child, to provide relative care, they place a child in general foster care. A general foster carer has:

- Been approved by Tusla

- Completed a process of assessment

- Been placed on the panel of approved foster carers to care for children in care

Many of the children living in foster care have been with their foster families for most of their lives. Others have shorter placements.

Others have shorter placements.

At the end of May 2020, 65% of children in care were in general foster care.

Day foster care

This involves specially trained foster parents providing foster care for a child on a daily basis. The child is not separated from their family, as they go home each evening, yet benefit from the additional care offered in the foster home. This type of care gives the child's own family an opportunity to deal with difficulties each day as they arise. The aim of day foster care is that the child can return home on a full-time basis.

Short-term foster care

This involves a child being cared for by a foster family for a short period (ranging from 1 week to some months). The aim is for the child to return to their family full-time at the end of the short-term period. Sometimes, however, the child may remain in foster care on a longer-term basis.

Long-term foster care

Long-term foster care involves a child being cared for by a foster family for a number of years and may continue until the child reaches adulthood.

If foster parents, including relative foster parents, have been caring for a child for a continuous period of at least 5 years, they may apply to the court for an order. The order may, subject to conditions, give the foster parents broadly the same rights as parents to make decisions about their children. For example, they will be able to give consent for medical and psychiatric examinations, treatment and assessments, and apply for a passport. The foster parents must get consent from Tusla, and may also need the consent of the parents or guardians. This is set out under Section 4 of the Child Care (Amendment) Act 2007.

After a period of time, if it becomes clear that it will not be possible for the child to be returned to their birth parents or family, it may be decided that the child’s best interests would be served by being adopted by the foster parents.

The foster child and their own family

When a child is placed in foster care on a daily, short-term or longer-term basis, maintaining links with his or her own family is very important. The child's own parents are involved as much as possible and are always kept fully informed of how the child is getting on. The child will see their own family as much as possible and even though they may live (even for a longer-term period) with another family, the child's identity and name is their own.

The child's own parents are involved as much as possible and are always kept fully informed of how the child is getting on. The child will see their own family as much as possible and even though they may live (even for a longer-term period) with another family, the child's identity and name is their own.

Who can become a foster carer?

In March 2020, there were more than 4,000 foster carers on the panel of approved foster carers in Ireland. Any person or family can apply to Tusla to be assessed as a foster parent or foster family. Foster carers are a diverse group and may be single, married, in a same-sex relationship, employed, unemployed, renting, retired, or have a disability. They may also be from different cultures, ethnic or religious backgrounds.

A foster carer must be able to provide adequate and appropriate accommodation for the foster child. Tusla assigns a social worker to carry out an assessment of suitability. These assessments include meeting all members of the family (particularly the foster parents) over a number of months. References, Garda vetting and a willingness to attend training and ongoing learning support will also be required as part of this process. Find out more about what is required to become a foster carer at tusla.ie.

References, Garda vetting and a willingness to attend training and ongoing learning support will also be required as part of this process. Find out more about what is required to become a foster carer at tusla.ie.

Allowances

Tusla pays a basic maintenance allowance to foster parents and families. The agency also offers support structures to assist the child, carer and family during the fostering term, including:

- Training for the foster carer or family

- Ongoing liaison with social workers

- Insurance

- A medical card for the child in care

The Foster Care Allowance payable for children in foster care placements is as follows:

| Age of child | Weekly rate |

|---|---|

| Under 12 years | €325 per child |

| 12 years and over | €352 per child |

An allowance may be paid between the ages of 18 and 21 to young people leaving care who are still in training or education. In certain circumstances, support may continue for a further 2 years if the person is on a clear education or training pathway.

In certain circumstances, support may continue for a further 2 years if the person is on a clear education or training pathway.

This allowance is known as a Standardised Aftercare Allowance. A range of other supports is available to all young people leaving care, whether they are in education or not. You can find more information on Financial Support in Aftercare (pdf) on the Tusla website.

Foster care allowances from Tusla are not taken into account in the means test for social welfare payments and are not taxable. An Increase for a Child Dependant may also be payable.

Child Benefit

When a child has been placed in foster care by Tusla, Child Benefit may continue to be paid to the child's mother or father for a period of 6 months from the date of the child's placement. Payment may then transfer to the foster parent(s) provided that the child has been in their continuous care for a period of 6 months.

Further information

If you are interested in fostering and would like to offer a child or young person a home, you should contact the Tusla fostering service.

The Irish Foster Care Association (IFCA) is a voluntary organisation working with Tusla throughout Ireland to promote fostering as the best option for children who cannot live with their own family. The Association, through its network of local branches nationwide, offers advice, information and support for foster carers. In addition, the Association has produced an information pack (pdf) for those interested in finding out more about fostering.

Tusla - Child and Family Agency

Brunel Building

Heuston South Quarter

Dublin 8

Ireland

Tel: (01) 771 8500

Homepage: https://www.tusla.ie/

Email: [email protected]

Irish Foster Care Association

Unit 23

Village Green

Tallaght Village

Dublin 24

Ireland

Tel: (01) 459 9474

Fax: (01) 462 8014

Homepage: http://www.ifca.ie

Email: [email protected]

Page edited: 4 August 2021

Related Documents

- Domestic adoption

An outline of the adoption procedure in Ireland.

- Children in care

The primary legislation regulating child care policy is the Child Care Act 1991 which brought in considerable changes in relation to children in care. Find out more here

- Youth homelessness

Causes of youth homelessness, also arrangements for young people who are homeless or at risk of losing their home.

Contact Us

If you have a question about this topic you can contact the Citizens Information Phone Service on 0818 07 4000 (Monday to Friday, 9am to 8pm).

You can also contact your local Citizens Information Centre.

Foster CareTusla - Child and Family Agency

Foster CareTusla - Child and Family Agency

| Children and young people in your community urgently need the opportunity to be cared for in a loving and caring home. Tusla foster carers provide a safe, secure and stable home environment for the most vulnerable in our society and are a core part of ensuring children who need foster care are cared for in a loving, home environment. We’re running a recruitment campaign to encourage people like you to consider fostering, and changing a child’s life. |

| |

| ||

|

Across Ireland some 4,124 Tusla foster carers open their homes to 5,450 children. Tusla owes our foster carers in each county a big debt of gratitude. Our foster carers are invisible heroes. But don’t take our word for it, children in their care have told of the invaluable influence that Tusla foster carers have had on their lives:

| ||

Adopting a child from Russia costs 17 thousand euros - December 20, 2005

All news A new earthquake has occurred in Turkey. People took to the streets en masse

People took to the streets en masse

Bastrykin told how many criminal cases were opened in Russia because of the discrediting of the RF Armed Forces

The avalanche cut off Sochi from Russia: it demolished the bridge and damaged the gas pipeline. Collected video from eyewitnesses

A train of trams was noticed in Yekaterinburg

Why passengers are not allowed to the Yekaterinburg railway station: we publish clarifications on safety rules

In the Urals, they said goodbye to a fighter of the Wagner PMC, who died in the Northern Military District and was convicted of murder

People in bulletproof vests gathered at the Sberbank in the center of Yekaterinburg. We tell you what happened

Waves the size of a five-story building: how the devastating North Kuril tsunami was hidden in the USSR — it claimed thousands of lives : the developer talked about the benefits of buying an apartment at an early stage

Public utilities from an elite house in the center of Yekaterinburg responded to claims due to a fecal flood and cockroaches

Left for work and did not return. Search for a man in the Sverdlovsk region for the third day

Search for a man in the Sverdlovsk region for the third day

A stadium in Yekaterinburg has been turned into a super-greenhouse to grow grass even in severe frosts

In Akademichesky, a mustachioed shop visitor stole expensive perfume twice: video

“Children stay at home”. In Yekaterinburg, two schools, a kindergarten and a hospital were left without cold water

Hide at home! Heavy snowfalls are approaching the Sverdlovsk Region

"They are walking through a dark forest." In the Ural village, children were left without a bus and themselves get to school for 20 kilometers

“You can carry a person in a suitcase - no one cares”: the media manager told how he crossed the borders of 10 countries with a Russian passport

In Yekaterinburg, the ex-policeman was given 12 years in prison for "bookmarks"

The asphalt is already shining through! Residents of Akademichesky showed sprawling roads

"Why the hell didn't you let me in?!" Nervous drivers in Yekaterinburg fought for a place in a traffic jam

“Mom is crying”: a year and a half later, a Yekaterinburg woman was given a new cause of death for her unborn son

“If you can’t sell it, buy it yourself”: employees told horrors about working at Krasnoy&Beliy

Left from home at six in the morning: a teenage girl with an unusual name disappeared near Yekaterinburg

The mayor's office showed the new school on Roshchinskaya for the first time. So far only on paper0003

So far only on paper0003

We divide two, three - in the mind. The longer you work, the less pension points you get

“A person like this is lying in the trash!” A Uralian found an urn with ashes in a garbage dump

The governor changed his mind: residents of new buildings will be allowed not to pay for overhaul for three years

The legendary faceted glasses will be returned to passenger trains (because they are difficult to break)

No one will be able to write these 8 words correctly the first time . Are you able to?

Half a thousand a piece! Ekaterinburg opened a snack bar with "golden" hot dogs

In Yekaterinburg, a thief in black threatened the seller with a knife, which he had previously stolen. What happens if you go through it?

Two deputies of the mayor of Yekaterinburg and the son of Chernetsky were sanctioned by Ukraine because of the main city bank "Spetsavtobazy" with scammers

How a dead phone almost led to tragedy. The story of an 86-year-old grandmother who got lost in Yekaterinburg

The story of an 86-year-old grandmother who got lost in Yekaterinburg

Until the rates increased: the Urals residents were rushed to apply for a mortgage - why you need to do it before March 17

The amount for housing and communal services will be half as much. Owners of private houses were told how to save money on a communal apartment

All news

Share

Irish couples pay up to 17,000 euros to international agencies to find children for adoption in Russia. Now Russia has become the most popular country among Irish people who want to adopt a child abroad, despite the fact that there is no adoption agreement between Russia and Ireland, writes the British The Times.

Such huge payments are criticized by the leadership of the International Adoption Agency, which says that the Irish government must take steps to put an end to this.

"I find it disgusting to have money in this process," says Kevin O'Byrne. cases showed enough activity for such an agreement to be concluded. From 398 children adopted last year from other countries 189 were from Russia. This is three times more than in 2000. Reasons for Russia's popularity are cited as a reasonable legal system, white race children, and the relative speed of the adoption process.

cases showed enough activity for such an agreement to be concluded. From 398 children adopted last year from other countries 189 were from Russia. This is three times more than in 2000. Reasons for Russia's popularity are cited as a reasonable legal system, white race children, and the relative speed of the adoption process.

"Russians are very similar to the Irish in terms of habits and culture," says Derek Farrell of Irish Adoption Families from Russia. "They love to sing, they drink a lot. Unfortunately, there are a lot of abandoned children, but I will hope for the best for Russia in connection with the Russian law on the protection of children." The fact that adoptions from Romania and Belarus have been put to an end also encourages the Irish to turn their eyes to Russia. Romania has suspended the practice of adoptions due to pressure from the EU.

Ireland has bilateral agreements with China, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines. The Adoption Commission has attempted to arrange a meeting with Russian counterparts to conclude the same agreement.

The absence of an agreement with Russia, however, does not stop Irish couples. If the Irish authorities have recognized them as meeting the requirements for adoptive parents, they can independently deal with the issue of adopting children in Russia. But the lack of an agreement leads some of them to seek help from agencies that charge dearly for their services. “The disadvantage is that there are adoption agencies,” Farrell agrees. “They charge a lot of money: as far as I know, adopting a child from another country costs 16,800 euros. We are an independent group, accredited by the adoption commission, which helps people to adopt children for free without agency assistance.

Annette and John Kenny from Cork adopted a child from Russia through Farrell's group. Their sons Simon (6) and Luke (5) were taken from the same orphanage at the age of three. "Our friend had children adopted in Russia, and we could see how quickly they settle down, - says Annette Kenny. - This confirmed us in choosing Russia. We did not want to use the services of agencies, so we turned to Derek and his wife Olga, who is Russian herself. It was more personal, it was not a business."

We did not want to use the services of agencies, so we turned to Derek and his wife Olga, who is Russian herself. It was more personal, it was not a business."

For many couples adopting a child, time is of the essence. The process of checking a couple for compliance with all requirements in Ireland can take from 18 months to three years, more than 1,800 couples are waiting for the completion of this procedure. "People's decision is often determined by where they can go through the adoption process the fastest," says Kevin OBearn. "After they've waited three years to get an adoption, they want to go where they can get help with adopting as quickly as possible." .

Some people think that a white child of European appearance will feel more comfortable in Ireland. According to Farrell, this is another reason why Russia is so popular. "Besides, children in Russia are well looked after, they are healthy children. The process is more transparent: future parents are allowed to come to orphanages - and this is not the case everywhere. "

"

Ann McElhinney, a journalist who has made several documentaries on cross-country adoptions, says that while prospective adoptive parents are subject to stringent scrutiny in Ireland, the weak link is the adoption process in the countries where the children are taken from. “These adoptions cost a lot of money, and for poor countries like Vietnam, or some regions of Russia, this is a fortune,” she says. "Despite the rigorous checks and good intentions of Irish adoptive parents, they cannot be sure that the child they are promised to be given for adoption actually exists."

- LIKE0

- LAUGHTER0

- SURPRISE0

- ANGER0

- SAD0

See the typo? Select a fragment and click Ctrl+Enter

Comments0

Guest

Enter

RFIRѕRIRѕSASHNA RARM? 2

RARIRARѕSASHMANI RARM? 2Article 21: Adoption | CRIN

Text

States Parties that recognize and/or permit the existence of an adoption system shall ensure that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration and they:

a) ensure that the adoption of a child is authorized only by competent authorities who determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures and on the basis of all relevant and reliable information, that the adoption is permissible in view of the status of the child in relation to parents, relatives and legal guardians, and that, if required, the persons concerned have given their informed consent to the adoption on the basis of such consultation as may be necessary ;

b) recognize that adoption in another country may be considered as an alternative way of caring for a child if the child cannot be fostered or placed with a family that could provide for his upbringing or adoption, and if the provision of any appropriate care in the child's country of origin is not possible;

c) ensure that, in the event of a child being adopted in another country, the same safeguards and standards apply as apply to domestic adoption;

d) take all necessary measures to ensure that, in the event of an adoption in another country, the placement of a child does not result in undue financial gain for those involved;

e) promote, where appropriate, the objectives of this Article by concluding bilateral and multilateral arrangements or agreements and endeavor on this basis to ensure that the placement of the child in another country is carried out by the competent authorities or bodies.

What does article 21 say?

Article 21 sets standards for adoption - where it is recognized practice - to ensure the best interests of the child in all adoption decisions first and foremost.

The need for children to be adopted must be determined in the right way: decided by the competent authorities, with the informed consent of all parties involved; be carried out in the right direction, without "unjustified financial benefits"; intercountry adoption should only be considered when appropriate care cannot be provided to the child in their own country.

This article should be seen in the context of the Convention on the Rights of the Child as a whole: it deals with personal identity, the right of children to know their origins, to have the care and support of their parents, and the care of children deprived of a family environment – all of these must be achieved subject to the overriding consideration of the best interests of the children.

Why is this right important?

No one will dispute the benefits of children growing up in a loving, stable and permanent family, and the fact that adoption can be one way to achieve this goal - provided that this process is regulated by law and monitored by government agencies. However, adoption can also deprive children of their rights if the rules are not properly set and the interests of the children are not a primary consideration in decision making.

What problems might arise?

Recent reports have highlighted the extent of illegal and unethical cases involving adoption - particularly in the international arena - raising questions about why, how and when adoption should be considered an option.

The main controversy has arisen because of the strong global "demand" for children, which currently exceeds the number of children eligible for adoption. In fact, very few "orphans" do not have families; A recent study showed that 98 per cent of children in institutions in Central and Eastern Europe have at least one living parent and that when these institutions close, many of these children are taken away by family members. In some countries, children are placed in institutions not because they are unwanted or have no family, but because of poverty. In other cases, children are left homeless due to social norms that reject teenage pregnancy and children born out of wedlock. In Ireland, for example, thousands of unmarried women and girls were forced to abandon their children in favor of adoption and were placed in catalytic orphanages (the last of which closed in 1996). In Uruguay, unmarried girls under the age of 18 still cannot be registered as the parent of their child (Article 235 of the Civil Code).

In some countries, children are placed in institutions not because they are unwanted or have no family, but because of poverty. In other cases, children are left homeless due to social norms that reject teenage pregnancy and children born out of wedlock. In Ireland, for example, thousands of unmarried women and girls were forced to abandon their children in favor of adoption and were placed in catalytic orphanages (the last of which closed in 1996). In Uruguay, unmarried girls under the age of 18 still cannot be registered as the parent of their child (Article 235 of the Civil Code).

While most prospective parents have a well-intentioned and legitimate desire to start a family, the scarcity of adoptable infants and young children in their home country, coupled with harsh and lengthy adoption procedures, motivates them to look for children in countries where there are rules. This has resulted in children being deceived from their parents and essentially sold by unscrupulous intermediaries. Prior to legal reform in Guatemala, for example, children were abducted, abducted and sold for adoption in the usual way, in collusion by notaries and medical professionals who falsified DNA tests and legal documents. At some point, one in a hundred children was placed for international adoption.

Prior to legal reform in Guatemala, for example, children were abducted, abducted and sold for adoption in the usual way, in collusion by notaries and medical professionals who falsified DNA tests and legal documents. At some point, one in a hundred children was placed for international adoption.

Despite the growing demand for intercountry adoption, the practice has declined worldwide since 2004, primarily due to the development of strong national systems to allow most children to remain in care in their home country. Many countries are currently restricting international adoptions of children who were generally ignored domestically, such as children over a certain age or children with disabilities. While this indicates progress, it has led to new problems: some countries hide children's mental retardation from their adoptive parents, who are later unable to cope, which in turn leads to a very unpleasant situation for the child.

While international adoption is the main arena for such abuses, domestic adoption is also not free from such abuses. Internal procedures may violate children's rights in other ways, such as when their views are not considered or when they are denied access to their files.

Internal procedures may violate children's rights in other ways, such as when their views are not considered or when they are denied access to their files.

What can be done?

The original draft article 21 only required states to "facilitate" adoption. However, by this time, reports of illegal and unethical adoptions had already begun to emerge, prompting the project developers to change the final draft to establish minimum standards (1). Other important adoption standards include Hague Convention 1993, which protects children at the intercountry level of adoption, the European Convention on the Adoption of Children (Updated in 2008) and the draft guidelines on intercountry adoption in Africa.

The most important factor throughout the entire adoption process, from the identification of a child in need of a family to the very procedure for monitoring the child's placement, is the best interests of the child (Article 3), and this should be spelled out in law.

The principle of best interests requires that the circumstances and personality of the child be examined by judicial and professional authorities in a transparent manner. They are responsible for determining the best interests of the child and the informed consent of the parties, with the full knowledge of all involved. Consideration of the child's views is paramount in establishing the child's best interests under Article 12. Some countries set a minimum age above which the child's consent must be obtained, in other countries children may veto their adoption.

Another fundamental principle of the Hague Convention is the principle of subsidiarity. It requires finding solutions that have softer interventions (family support system, assistance to foster families, and support from family members, for example) before permanently destroying the child's own family ties. Before starting any adoption procedure or recognizing a child for adoption, all possible solutions must be considered. The child's individual situation should be carefully considered to establish an alternative form of parental support or assistance.

The child's individual situation should be carefully considered to establish an alternative form of parental support or assistance.

In practice, the principle of best interests is often violated in intercountry adoptions, which often leads to the perception that children would be better off with a wealthy family outside their country of origin than staying with poor relatives at home.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child states that the State must take all possible measures to support children to stay with their families where it is considered to be in their best interests (Article 20.3), and that parents have the primary responsibility for raising their children. child (Article 18). Adoption should only be considered when the parents are unwilling to bear this responsibility or are found by the court to be unable to do so. In this case, the child must be placed in a family of relatives or provided with proper care within their own country, while international adoption is considered only as a last resort. The Hague Convention supports this view, also known as the principle of subsidiarity. A recent Council of Europe report urges states to continue to send adoption applications to other countries only in the number and time necessary to avoid attempts to remove children from their families for financial gain. Particular vigilance must be exercised in the post-emergency period by both sending and receiving countries, as tracing the identity documents of a child and their relatives is almost impossible, and the implementation of relevant regulations is complicated.

The Hague Convention supports this view, also known as the principle of subsidiarity. A recent Council of Europe report urges states to continue to send adoption applications to other countries only in the number and time necessary to avoid attempts to remove children from their families for financial gain. Particular vigilance must be exercised in the post-emergency period by both sending and receiving countries, as tracing the identity documents of a child and their relatives is almost impossible, and the implementation of relevant regulations is complicated.

There is widespread concern about the sale of children for adoption for "undue financial gain". Article 35, together with the Optional Protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, prohibits the sale of children for any reason and also requires States to criminalize those responsible for these acts.

Adoption management helps match children with the right people based on reliable information. All prospective parents should be informed about the chances of international adoption. They should also be helped to prepare for children's questions about their background. Articles 7 and 8 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child promote the rights of children to know of their adoption and to know the identity of their parents at will. These articles were developed by children's rights advocates in Latin America in response to adoptions (often by military families) of children of parents who "disappeared" during the dictatorship 1970s and 80s. In this vein, the Convention also affirms the importance of introducing the child (at his request) to his own culture and language, if they differ from the place of residence of his foster family (Article 30).

All prospective parents should be informed about the chances of international adoption. They should also be helped to prepare for children's questions about their background. Articles 7 and 8 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child promote the rights of children to know of their adoption and to know the identity of their parents at will. These articles were developed by children's rights advocates in Latin America in response to adoptions (often by military families) of children of parents who "disappeared" during the dictatorship 1970s and 80s. In this vein, the Convention also affirms the importance of introducing the child (at his request) to his own culture and language, if they differ from the place of residence of his foster family (Article 30).

In the case of intercountry adoption, states must ensure that children obtain the citizenship of their adoptive parents to prevent the situation of being stateless.

This page is part of the guide to children's rights as set out in the articles of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Learn more

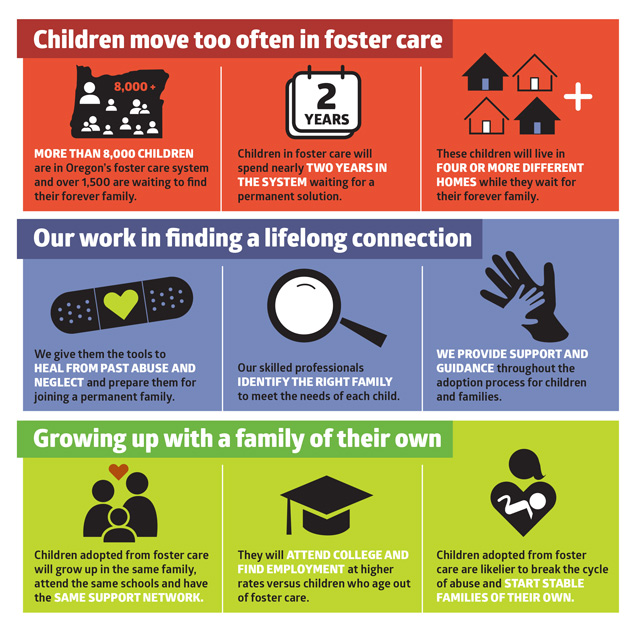

Due to the humanitarian crisis and the impact of Covid-19 on our communities, Tusla is experiencing an increased demand for all types of foster care placements

Due to the humanitarian crisis and the impact of Covid-19 on our communities, Tusla is experiencing an increased demand for all types of foster care placements