How to find the father of an illegitimate child

How To Discover The Secrets of Your Illegitimate Ancestors : Genealogy Stories

Discovering an illegitimate ancestor in your family tree is exciting. It presents a mystery to be solved. A case to be cracked. What were the circumstances of their birth? Who were their parents? But, these curious ancestors also pose some difficulties. How can we track down unnamed fathers? Will we ever know their secrets?

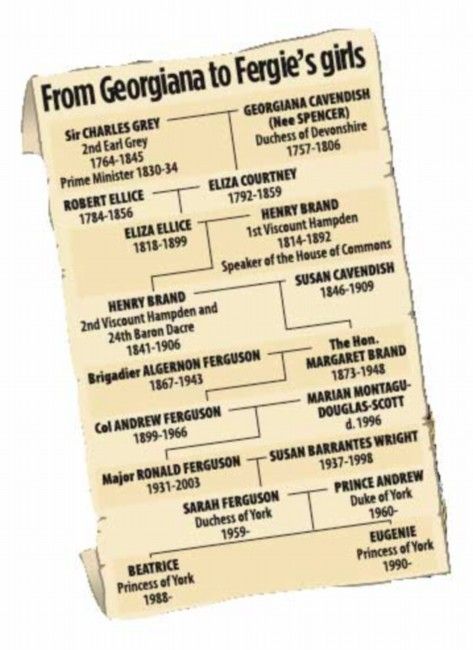

For an example of a real case of an illegitimacy mystery, check out my interview with Nick Barratt. Nick revealed his many attempts to discover the identity of the father of his great-grandmother.

Table of Contents

What is an illegitimate ancestor?

Illegitimate means “not recognised as lawful offspring”, specifically because the child was born to unmarried parents. See Merriam-Webster dictionary

When you see genealogists using the term, please know that they are using it as a legal term and not a judgement. As an unmarried mother of 3, I have 3 little illegitimate blighters nipping at my heels so there is certainly no judgement here!!

The legal nature of the term is important and sadly, it’s still relevant. Children born to married parents had greater inheritance rights than children born outside of wedlock.

Whilst registering the birth of my children, their father and I were advised that should we decide to marry, then we should consider re-registering the birth of our children. Just in case we went on to have another child born within wedlock. If we didn’t re-register, then our imaginary “legitimate” child would have greater inheritance rights then our “illegitimate” children. It turns out, this is incorrect and the law was changed in 1987. That’s right…not 1897….1987! Technically, though you still need to re-register your children and can be fined a whopping £2 (that’s right £2) for failure to do so.

Note that being born illegitimate does not necessarily mean that your ancestor was the offspring of a single mother. Or that your ancestors parents never married.

How do I know if my ancestor was illegitimate?

Sadly, our ancestors were often made to feel ashamed of having children outside of wedlock. Especially in cases where no future marriage was planned. There were serious social-economic consequences to having a child outside of wedlock too. The number of jobs that women could do were far smaller than those available to men. Working women were paid less then their male counterparts too. Add to this the complication of an extra mouth to feed and the need to obtain childcare and it’s no surprise many women ended up at the Workhouse. In a judgemental, patriarchal society, a woman with an illegitimate child may have found that her “cards had been marked” and she was considered undesirable to future potential marital partners. This could prevent her from ever gaining the financial security a husband might bring.

Especially in cases where no future marriage was planned. There were serious social-economic consequences to having a child outside of wedlock too. The number of jobs that women could do were far smaller than those available to men. Working women were paid less then their male counterparts too. Add to this the complication of an extra mouth to feed and the need to obtain childcare and it’s no surprise many women ended up at the Workhouse. In a judgemental, patriarchal society, a woman with an illegitimate child may have found that her “cards had been marked” and she was considered undesirable to future potential marital partners. This could prevent her from ever gaining the financial security a husband might bring.

This means that our ancestors may have tried to conceal their illegitimate offspring. It’s therefore worth considering less obvious clues, along with the glaringly obvious (such as an ancestor that has the same surname as their mother, an inability to find a marriage record or / and an infant with no father’s name recorded on their baptism / birth record.

The below clues do not always indicate an illegitimacy but they are potential flags that raise questions:

- Your ancestor grew up in institutions (like industrial schools, workhouses), you don’t find them living with their parents on the various census records.

- A long gap between the birth of children.

- A mother and child on a census live without a husband, perhaps with the mother’s family. Mother’s marital status is given as “married”. Further flags should be raised if this happens on several census OR if you later find mother and child on a census in which she is married, the husband is present but mother and child’s surnames now match the husbands and not that of earlier census.

- Missing births and baptisms.

- Some ambiguity in a child’s surname, perhaps a name that changes across documents.

- A middle name that looks like a surname but doesn’t relate to any of the mother’s family.

- Finding an ancestor with a child, but being unable to find that child’s birth registration – perhaps the child was actually the child of a sibling

Bride or Groom’s giving their father’s name as something you either don’t recognise OR that differs to the name given on other documents (including re-marriages). Perhaps they were illegitimate and didn’t know (or were unsure of) their father’s name?

Perhaps they were illegitimate and didn’t know (or were unsure of) their father’s name? - Upon your widowed (or unmarried) ancestors’ death, their property went to the Crown OR your ancestor is mentioned in the will of someone else, rather unexpectedly. There are various rules around inheritance and some pay provide clues to your ancestors illegitimacy. There is a great summary at FamilySearch.

How did our ancestors try to hide illegitimacy?

Considering the social stigma it is not surprising that some of our ancestors attempted to conceal the illegitimacy of their children. Here are few examples for you based around different scenarios.

- If your ancestor was born very shortly (days, couple of weeks) before their parents married they might have held off registering the birth of their child until after their marriage. Similarly, pre-1837 (before centralised birth registration) they may have delayed a baptism.

- For birth’s after 1837, it is worth bearing in mind that father’s did not need to agree to be named in order to have their name recorded on the birth certificate.

A woman could say that the father was a labourer called William Smith. It’d be hard to prove otherwise, when William Smith could be any number of different people. Although, rules changed in 1875 requiring both mother and father to agree to be named, it doesn’t take much of a stretch in imagination to think of ways around this if someone really wanted to pretend to be married, despite a father refusing to attend.

A woman could say that the father was a labourer called William Smith. It’d be hard to prove otherwise, when William Smith could be any number of different people. Although, rules changed in 1875 requiring both mother and father to agree to be named, it doesn’t take much of a stretch in imagination to think of ways around this if someone really wanted to pretend to be married, despite a father refusing to attend. - If a young unmarried mother had older, married and more financially secure parents or siblings, they may have asked them to raise the child “as their own”. This would hide their secret illegitimacy and protect both mother and child’s reputation.

- Neighbours may have helped bring up a child. My own illegitimate Great-Grandmother was brought up by her neighbours. She didn’t realise her mother (an occasional visitor, called “Aunt Sissy”) was her mother until later in life – by which time “Aunt Sissy” had remarried and had other children.

- In more extreme instances poor women may have decided that it would be best for both their child and themselves to leave the child – either at a foundling hospital or having the child adopted.

- A child lives with their father and their mother is not present. Unmarried mother’s lost right’s over their child once they turned 7 years old. A wealthy father may have decided that they wanted to bring up the child (or send them to boarding school) and give them financial support

Of course, these are just a few examples and just as many people have complicated family structures now – so too did people in the past!

10 hints to help you discover illegitimate ancestors' father's names

What family historian doesn’t want to fill in that blank space on a birth record? Of course we ask ourselves, who is the father? Did they know about their child? Did they abandon both mother and child? Why?

Sometimes we may never find the answer to these questions – but we should always keep striving to try and answer them. We shouldn’t presume that it’s impossible. Read here my article detailing how I discovered the father of my illegitimate 3x Great-Grandfather.

Here’s my top tips for tracking down father’s identities:

1. Check Marriage Certificates

A father’s name might not be recorded on their birth but they may have named one on their marriage. Sometimes this name is made up, but not always. Sometimes it really is the father’s name and sometimes it’s a muddled version or a half truth. Don’t forget to check all marriages (many of our ancestors married more than once, after being widowed). Lastly, make a note of the occupation of the father. It might help you narrow down possibilities.

2. Stalk The Neighbours

If you have a hint of a father’s identity (perhaps due to DNA or one of the other suggestions on this list) – then look at your ancestor’s childhood neighbours. This may mean using census, or for earlier ancestors, looking at other children baptised within your ancestors parish. Can you find that name anywhere amongst the other parishioners?

2. Bastard Wasn't Always a Swear Word

The Bastardy Act 1733 meant that man could be imprisoned until he coughed up funds for looking after a child or at least agreed to marry the mother of his child. This was not an Act born of altruism. There was a real risk that children born outside of wedlock would become a financial burden upon the parish. Of course, parishes were keen to avoid this. Unmarried mothers were legally obliged to inform the parish that they were expecting to deliver an illegitimate child. They would then be submitted for a bastardy examination, during which they would be asked to name the father of their child. That father would then be required to pay regular support to mother and child (a bastardy bond). Alternatively, they could pay the parish compensation. In reality, many of these examinations took place after a child was born. This practice slowly lessoned after 1834 with the introduction of the New Poor Law (the one that brought about the workhouses).

This was not an Act born of altruism. There was a real risk that children born outside of wedlock would become a financial burden upon the parish. Of course, parishes were keen to avoid this. Unmarried mothers were legally obliged to inform the parish that they were expecting to deliver an illegitimate child. They would then be submitted for a bastardy examination, during which they would be asked to name the father of their child. That father would then be required to pay regular support to mother and child (a bastardy bond). Alternatively, they could pay the parish compensation. In reality, many of these examinations took place after a child was born. This practice slowly lessoned after 1834 with the introduction of the New Poor Law (the one that brought about the workhouses).

3. Follow The Money

Whenever money changes hands there’s normally a record. These records might lead to clues. For example, parish accounts might detail payments to an unmarried mother AND maybe they took the time to note that the alleged father was deceased or serving in the militia. You never know until you check. See here for more detail on the parish chest.

You never know until you check. See here for more detail on the parish chest.

Similarly, check whether your illegitimate ancestor completed an apprenticeship. These had to be paid for in the form of an indenture. Although a father’s name might not be included on your ancestor’s apprenticeship papers, the name of whoever paid the indenture might be a clue to a father’s identity. Read the The National Archives guide here.

Lastly if your pregnant ancestor entered the workhouse there may be information recorded, particularly if a settlement record were required. See here for a more detailed look at workhouse records.

4. "Naughty" Ancestors Leave A Mark

I’m sure you can imagine lots of circumstances within which the birth of a child might result in activities at court. Failure to pay maintenance. A disputed father’s identity. Tragically, perhaps the conception of your ancestor was tied up with a more serious crime (assault, rape, fraud). Check petty and quarter sessions for information.

5. Read All About It

You just never know what you are going to find in a newspaper, court cases of all sorts, family disputes. I found my own pregnant ancestor got into an altercation with one of her neighbours. I later discovered that the baby she was carrying did not belong to her husband. Was that what the altercation was about? Were these named neighbours clues to a father’s identity? You can purchase a subscription to Find My Past or British Newspaper Archives (affiliate links) to explore an amazing collection of newspapers. Read my article here.

6. Track Mum's Movements

It sounds obvious and it is highly dependent on when your ancestor was born – but where was Mum about 9 months before she gave birth? Who was nearby? What was Mum doing?

7. Take A DNA Test

Cluster your results using colour coding to tie up each of your grandparents, then great grandparents. Is there a surname in your matches that keeps cropping up? One you can’t account for? Or do you have surnames in your matches tree that tie in with clues you’ve gained from trying the above steps? Please keep in mind you are more likely to have success with DNA with more recent illegitimate ancestors. DNA is diluted over the generations.

DNA is diluted over the generations.

I recommend testing with Ancestry, purely because it has the largest database of test kits. You can purchase a kit here. Please note this is an affiliate link.

Don't Give Up

I hope, like Nick, you manage to track down the father’s of your illegitimate ancestors. But be prepared for some surprises along the way. Nick certainly found some! Please also note that it can take a long time to track down the identify of those illusive unnamed fathers. It’s not easy and definitely falls into the realms of more advanced genealogy. Services like my one-to-one tuition might be able to help you tackle these techniques in detail.

Further Reading

University of Cambridge, Supporting London’s Bastard Children

Courtship, sex and poverty: illegitimacy in eighteenth-century Wales by Angela Joy Muir

I haven’t read this one yet but it is definitely on my must read list –

Evans, Tanya. “Unfortunate Objects”: Lone Mothers in Eighteenth-Century London. 2005

2005

Write Your Family History With Style

Discover your family history writing style, and get writing today.

Read More »

Why Everyone Should Write Their Family History

Write your family history stories and suddenly you’ll find you are spotting research gaps, tackling brick walls, and creating a legacy of stories.

Read More »

5 Tips to Make The Most of Genealogy Research Rabbit Holes

Genealogy research rabbit holes are fun! Nothing beats the joy of finding yourself utterly fascinated by some random part of your family history. Whether your

Read More »

Join The Curious Descendants!

If you enjoyed this then you’ll LOVE my Curious Descendants emails. I send daily emails packed with family history writing tips, ideas and stories. Plus a weekly news roundup, ensuring you’ll never miss one of my articles (or an episode of #TwiceRemoved) ever again.

Name

CURIOUS DESCENDANTS

Never miss a blog post or an episode of #TwiceRemoved ever again. Plus get daily family history writing tips & a weekly news roundup delivered straight to your inbox. All for FREE!

Name

Purchases made via these links may earn me a small commission – helping me to keep blogging!

Read my other articles

THE CLUB

Start writing your family history today. Turn your facts into narratives with the help of the Curious Descendants Club workshops and community.

RESEARCH

Discover your family history. Whether you need me to research from scratch or take your existing work further. My service is fully tailored to your exact requirements.

GIFT CERTIFICATES

Give your loved one a gift that will last a life time – family history research or lessons. This is the ultimate personalised gift. One they will treasure forever.

How to Find the Father of an Illegitimate Child

Illegitimacy was not uncommon in earlier centuries. About 5% of all children born in England and Wales between 1837 and 1965 were illegitimate, which means they were born out of wedlock.

Many family tree researchers will find during their research that there is at least one illegitimate ancestor in their family.

Illegitimacy is no longer frowned upon like it was in the past, but finding that your ancestor was illegitimate may pose a problem when you conduct family tree research because it makes it that much more difficult to track down the name of the child’s father.

If you find there is a long gap between sibling’s birth dates, it is possible that the younger child may not be a brother or sister, but an illegitimate son or daughter of the supposed elder ‘sibling’, and passed off as being the child of the girl’s parents.

This brought great shame on the family, and they would go to any lengths to cover up the illegitimacy, even changing or falsifying records, which could pose problems for the family historian.

Although it can be upsetting to discover one of your ancestor’s may have been illegitimate, there can be reasons why this may have been the case, and the situation may not be because of promiscuity.

Certain reasons why the child may have been classed as illegitimate include prevention of a marriage in time, and the fact that the marriage may not have been recognised.

There are steps you can take to track down the father’s name which I discuss in detail below, which include perusing baptism registers, checking a child’s middle name, perusing army records, and checking census returns.

Circumstances May Have Prevented Parents Marrying Before Birth

Illegitimacy occurred in many walks of life.

It is possible that the couple had always intended to marry, but circumstances, such as the man being called into the army, or losing his livelihood so they could no longer afford to marry, precluded this from happening before the birth of the child.

In some circumstances, however, the man could have taken advantage of the woman, especially if they were in a servant-master relationship. Many unmarried mothers were domestic servants.

Many unmarried mothers were domestic servants.

If women were unemployed, their desire to find a source of income could have led to them becoming prostitutes as a way of making ends meet. This, in turn, could lead to the woman discovering she was pregnant.

Marriage May Not Have Been Recognised

If your ancestor was deemed to be illegitimate, it may not mean that their parents were not married, just that the marriage was not recognised by the institution who recorded the birth.

If a marriage had taken place in a non-conformist church or chapel, it may not have been legitimate in the yes of the church, and thus treated accordingly.

If a man married the sister of his dead wife, the children were deemed to be illegitimate because the marriage was not considered to be valid.

Some Women Murdered Their Babies

To hide the shame of giving birth to an illegitimate child, some women murdered their babies to hide the fact. It is terrible that we once lived in a society where women felt compelled to take this drastic and devastating step.

Rights of Illegitimate Children

An illegitimate son of Royalty was not able to inherit his title from his father, but if the father recognised him as being his son, he may have been issued with a coat of arms, it being indicated that this line was illegitimate.

How to Find Father of Illegitimate Child – Steps You Can Take

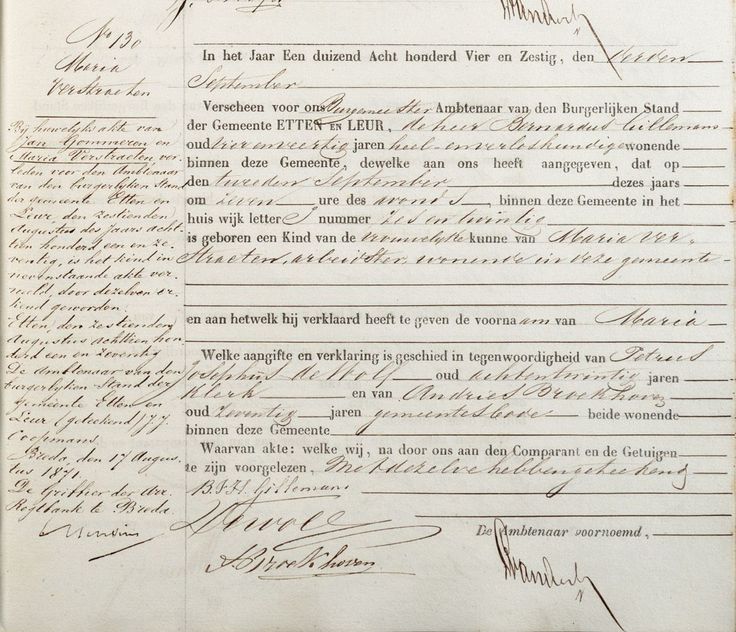

Search Through Baptism Entries in Parish Registers

In earlier centuries, illegitimacy was considered sinful, and the clergyman could be most unfair to illegitimate children by writing the word ‘bastard’ after the entry in the baptism register. Some entries also state ‘base born’ or ‘natural’.

If a child was illegitimate, the entry in the parish register may simply state, as in the Courteenhall parish registers, Martha daughter of Sarah Dunckley (a bastard) baptised June 17, 1781, which does not help you to track down the child’s father.

It may be very difficult to prove who the father was under these circumstances.

Some entries in parish registers give much more information, however, such as this entry in the baptism register of Northampton St Giles: William Hartnell son of Mary Bason was born Nov 21 1764, and baptised Jun 26, 1765.

This could be as a reference to the name of the father, in this case William Hartnell or a member of the Hartnell family.

Some entries give you even more information, even stating the name of the reputed father, as in this entry from Northampton Holy Sepulchre: Ann bastard daughter of Jane Mickley baptised October 25, 1772; Charles Embery reputed father.

This information can give you another avenue to explore because this usually meant that this had been proven, or that he had admitted to being the father.

Father’s Name as Middle Name

It was not uncommon for the illegitimate child to have their possible father’s surname as a middle name, or to take the surname of their mother’s future husband, if she subsequently married, but it does not necessarily mean that this man was the child’s biological father.

Higher Rates of Illegitimacy in Towns in Earlier Centuries

The rate of illegitimacy was usually higher in the towns than in villages because women could have moved into the town looking for work, such as work as domestic servants.

If the woman was unable to make enough money through her job as a domestic servant, she made have turned to prostitution to make ends meet because no effective social welfare system existed.

More pressure was placed on couple’s in villages than in towns to marry before the child’s birth, hence you may find a baptism just a few weeks after the couple’s marriage.

It is also possible that the community were more likely to act adversely if the child was born as the result of a casual sexual encounter, rather than born to a couple married in all but name.

A woman having illegitimate children was more likely to bring shame on the family in the villages than in the towns because the village was a close-knit community.

A woman was not stigmatised in the same way in the towns, with this lack of shame encouraging illegitimacy. It was also easier for the woman to remain anonymous in the towns than in the villages.

Father May Have Been in the Army

One reason that a woman may have had an illegitimate child is that her partner was in the army, and had abandoned her after a casual sexual encounter.

Lord Strange was compelled to argue in a speech to parliament in 1750 that many redcoats behaved irresponsibly toward women and had no respect for marriage.

If you do find that the father was in the Army, it may well be worth investigating further to see if an army regiment was stationed nearby at the time that the woman may have become pregnant. This could lead you to discovering more about the man concerned, and possibly even his birthplace.

Family May Have Accepted the Illegitimate Child

If your ancestor had a illegitimate child, it does not necessarily follow that she was disowned by her family.

My ancestor, Maria Dunkley, had two illegitimate children in 1827 and 1835 respectively, the latter child, Isaac, living with his mother, grandfather John and uncle Benjamin in Roade, Northamptonshire in 1851.

This showed that the family had completely accepted Isaac into the family.

Isaac even eventually married Jane McJannett, the daughter of his elder brother William’s wife Ann McJannett, (who was also illegitimate, born to John Shingler) on 26 September 1864 in Courteenhall, Northamptonshire.

Birth and Marriage Certificates

After 1837, finding that no father is recorded on a birth certificate usually meant that the child was illegitimate, but could also have meant that the father did not register the birth and the official did not wish to put him on the birth certificate in these circumstances.

In these circumstances, the mother’s maiden name was stated on the certificate.

If you do not see the father’s name on a birth certificate, it is also worth checking to see if the child was baptised, because the entry in the baptism register could help you to determine if the child was indeed illegitimate.

This can cause a problem in family history research, but sometimes the registrar or clergyman would insist that the baby was given the father’s surname as a middle name.

Although this may not have been insisted upon by the clergyman, my illegitimate ancestor was named William Baker Carrington, subsequently changing his name to William Carrington Baker.

Although William was born on 6 June 1852, his parents did not marry until 27 March 1856. If you find your ancestor has a surname as a middle name, they could have been illegitimate, so if you are unable to find their birth registration, it is worth checking the index under their middle name as well.

William Baker Carrington Birth CertificateWhen illegitimate children married, they did not always state their father’s name on a marriage certificate because they might not know it and also because the father might not have acknowledged their illegitimate child.

If the father was not stated on a marriage certificate, the bride or groom may have been illegitimate, but it could also simply mean that the father had disowned his child for some reason.

It is possible the bride or groom could simply make up a name, giving this fictitious man the same surname as themselves which can be very confusing when researching family history.

I have experience of this as my own relative, William Dunkley, stated Joseph Dunkley was his father when he married. Joseph was in fact his uncle.

Joseph was in fact his uncle.

If the events occurred after 1837, it is always worth obtaining both the birth and marriage certificates to prove or disprove your theory.

Illegitimacy Shown on the Census?

Sometimes, when looking at the ages of children born to the parents on a census, and the ages 20, 18, 15, 11 and 3 are shown, it is entirely possible that the 3 year old is in fact an illegitimate child of one of the elder siblings, so is in reality a grandchild rather than a child.

If your ancestor is living with a seemingly unmarried or widowed mother, as was the case for my own ancestor Mary Minton, who was living with her widowed? mother Mary in 1871, this could mean that the child may have been illegitimate.

If the census entry states that the mother was a widow, it is worth doing more research into whether or not she actually ever married, and was not stating that she was a widow to avoid awkward questions being asked.

Your Family May Know More About The Possible Illegitimacy

If the event occurred in within the lifetime of elder family members, they may be able to help you shed some light on whether your hunch is correct. If you take this path, however, please tread carefully because family members might find it difficult to discuss these events.

If you take this path, however, please tread carefully because family members might find it difficult to discuss these events.

It is possible that the shame they felt at the time is still deeply felt. Do not be too disappointed if they are not prepared to divulge the information.

Definitive Proof Of Who The Father Was May Not be Forthcoming

It is entirely possible you will never be able to prove that a particular man is the child’s father, although you suspect that he was.

My ancestor, Maria Dunkley, had two illegitimate children William Campion Dunkley and Isaac Campion Dunkley in 1827 and 1835 respectively, them both being baptised with the middle name of Campion, leading me to believe that a Campion was my ancestor’s father.

Although there was a family of Campion’s in Roade, Northamptonshire at the time of the births, I have never been able to establish beyond reasonable doubt which Campion was the father.

Newspapers can Provide a Breakthrough

Sometimes, a breakthrough can come where you least expect it. My ancestor, Ann McJannett, had an illegitimate daughter Jane in 1846, but the child’s father was not mentioned on the birth certificate and the birth was registered under the mother’s name of McJannett.

My ancestor, Ann McJannett, had an illegitimate daughter Jane in 1846, but the child’s father was not mentioned on the birth certificate and the birth was registered under the mother’s name of McJannett.

Whilst looking in a newspaper, I came across Ann’s name with regard to this matter, and it turned out that Jane’s father was reported as being John Shingler. This proves how important newspapers are as a resource for tracing your family history.

The Child may have been Mentioned in a Will

If the father of the child was wealthy, he may have provided for the child in any possible will. This may help you to prove your suspicions.

Bastardy Bonds

From 1576, Justices of the Peace could track down the father of a bastard child and issue a bond known as a Bastardy Bond. Bastardy Bonds were issued by the parish against the father of an illegitimate child, so that they could ask him to reimburse the parish for any possible expense of looking after the child.

The child’s mother is named in the Bastardy Bond, it stating that she had sworn whilst under oath to a Justice of the Peace that she was with child and that the child was likely to be born a bastard and as such, chargeable to the parish.

The document was also signed by the father and their surety to show that they accepted the terms of the document so could not shirk their responsibilities. The father’s occupation was also mentioned in the bond, which may help you to ascertain if you have found the correct man.

The bastardy bond is useful to the family historian because the child’s father is usually named in the document, making it easier to ascertain if the mother of the child went on to marry the father of her child. This is especially useful if the name of the father was not mentioned in the baptism register.

Bastardy Bonds can be found in quarter sessions records. Please be aware, however, that not all illegitimate children were the subject of a bastardy bond because it was only issued if the child was likely to become chargeable to the parish.

A bastardy bond was also unlikely to be issued in the unhappy event that the child died and was buried a few days after being baptised. A wealthier woman may not appear in the bastardy bonds because she could make her own provision for her own bastard child.

An example of a bastardy bond from Barnwell St Andrew, Northamptonshire in 1772 states that ‘Ann Lane, singlewoman, hath declared that she is with child and that the child wherewith she goeth is likely to be born a bastard and to be chargeable to the said parish of Barnwell St Andrew and that Charles Kempston the younger the father of such child.’

Bastardy Examinations

The Bastardy Examination was conducted before two Justices of the Peace and enquired into the circumstances surrounding how the woman became pregnant. A woman had to attend a bastardy examination, but these usually occurred after the birth of the child.

Illegitimate child \ Acts, samples, forms, contracts \ Consultant Plus

- Main

- Legal resources

- Collections

- Illegitimate child

A selection of the most important documents on request Illegitimate child (regulations, forms, articles, expert advice and much more).

- Minors:

- Administrative responsibility of minors

- Act on the inspection of housing conditions

- Act of examination of housing conditions

- Alimony for minor children

- Grandmother legal representative

- more ...

Judicial practice : izramist child

Register and get bouncer access to the system ConsultantPlus free of charge for 2 days

Open the document in your system ConsultantPlus:

Selection of court decisions for 2020: Article 49"Establishment of paternity in court" SK RF

(R.B. Kasenov) The court refused to accept for consideration the citizen's complaint about the violation of his constitutional rights by the provisions of Art. 49 of the Family Code of the Russian Federation, para. 3 art. 220 and par. 2 hours 1 tbsp. 327.1 Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation. In the citizen's opinion, the challenged norms impede the repeated filing of a claim to establish the fact of the paternity of the deceased father against the citizen, since they do not allow the presentation of additional evidence when considering such a case in the court of appeal. The court pointed out that the provisions of Art. 49The Family Code of the Russian Federation is aimed at protecting the rights of children whose parents are not married to each other, are consistent with the constitutional principle of state support and protection of the family, motherhood, fatherhood and childhood, enshrined in Part 2 of Art. 7, part 1, art. 38 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation (Determinations of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation of October 26, 2017 N 2386-O and November 26, 2018 N 3042-O). The above norm, which does not regulate the presentation of evidence, taking into account the fact that the Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation does not allow repeated consideration by the courts of disputes between the same parties, on the same subject and on the same grounds, cannot be considered as violating the constitutional rights of a citizen in the aspect indicated in the complaint.

The court pointed out that the provisions of Art. 49The Family Code of the Russian Federation is aimed at protecting the rights of children whose parents are not married to each other, are consistent with the constitutional principle of state support and protection of the family, motherhood, fatherhood and childhood, enshrined in Part 2 of Art. 7, part 1, art. 38 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation (Determinations of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation of October 26, 2017 N 2386-O and November 26, 2018 N 3042-O). The above norm, which does not regulate the presentation of evidence, taking into account the fact that the Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation does not allow repeated consideration by the courts of disputes between the same parties, on the same subject and on the same grounds, cannot be considered as violating the constitutional rights of a citizen in the aspect indicated in the complaint.

Articles, comments, answers to questions : Illegitimate child

Normative acts : Illegitimate child

"Review of the practice of interstate bodies for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms N 4 (2021)"

(prepared by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation) The Court recalled that the concept of "family" is not limited to a relationship based on marriage, but can cover other de facto "family" ties where the parties live together outside of marriage. The child born into such a relationship is ipso jure part of the "family" from the moment and by the very fact of his birth. Thus, between the child and his parents there is a connection that can be considered as family life. Moreover, when deciding whether a relationship can be considered “family life”, a number of factors may be taken into account, including the fact that the couple lives together, the length of their relationship and whether they have children together (paragraph 51 of the judgment).

The child born into such a relationship is ipso jure part of the "family" from the moment and by the very fact of his birth. Thus, between the child and his parents there is a connection that can be considered as family life. Moreover, when deciding whether a relationship can be considered “family life”, a number of factors may be taken into account, including the fact that the couple lives together, the length of their relationship and whether they have children together (paragraph 51 of the judgment).

"Review of the Practice of Interstate Bodies for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms N 7 (2020)"

(prepared by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation) In the opinion of the Court, intended family life may, in exceptional cases, fall within the scope of Article 8 of the Convention when family life , not yet fully established, takes place through no fault of the applicant. In particular, if the circumstances so require, the concept of "family life" should include the potential relationship that may develop between an illegitimate child and a biological father. Relevant factors that may determine the actual existence of close personal ties in these cases include the nature of the relationship between the biological parents and demonstrate the father's interest and willingness to be involved in the child's life both before and after birth (paragraph 66 of the judgment).

Relevant factors that may determine the actual existence of close personal ties in these cases include the nature of the relationship between the biological parents and demonstrate the father's interest and willingness to be involved in the child's life both before and after birth (paragraph 66 of the judgment).

DNA paternity test | Baby-Med

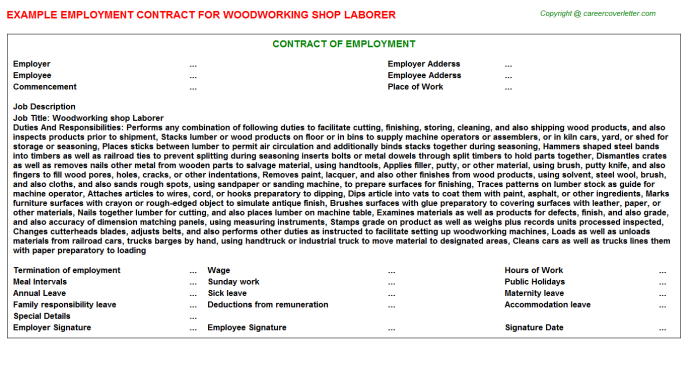

A Research on kinship. Personal identification by DNA.A-1 Establishment of paternity and motherhood. | |||||

A-1.1 | PATERNITY/MATERNITY STUDY (DUET), 25 markers. standard conclusion. | 2 members: 1 Intended Parent, 1 Child | Standard sample | 9800 | 3 w.d. |

A-1.2 | PATERNITY/MATERNITY STUDY (TRIO), 25 markers. standard conclusion. | 3 members: 1 Intended Parent, 1 Unconditional Parent, 1 Child | Standard sample | 10500 | 3 w. d. d. |

A-1.4 | RESEARCH FOR PATERNITY (MATERNITY) IN THE ABSENCE OF THE SUSPECTED FATHER (MOTHER), 25 markers. Standard conclusion. | 3 members: Intended Parent Grandparent, Child | Standard sample | 16900 | 3 w.d. |

A-1.9 | PATERNITY/MATERNALITY STUDY (DUET), 35 markers. Standard conclusion. | 2 members: 1 Intended Parent, 1 Child | Standard sample | 19100 | 5 w.d. |

A-1.10 | PATERNITY/MATERNALITY STUDY (TRIO), 35 markers. Standard conclusion. | 3 members: 1 Intended Parent, 1 Unconditional Parent, 1 Child | Reference sample | 22300 | 5 w.d. |

A-1. 11 11 | RESEARCH ON PATERNITY (MATERNITY) IN THE ABSENCE OF THE SUSPECTED FATHER (MOTHER), 35 markers. Standard conclusion. | 3 members: Intended Parent Grandparent, Child | Standard sample | 25900 | 5 w.d. |

A-2 Establishment of other types of relationship. | |||||

A-2.1 | STUDY FOR RELATIONSHIP "UNIVERSAL"Depending on the type of relationship being studied and the possibility of providing DNA samples of additional relatives, up to 40 DNA markers, X or Y chromosome markers, are examined. In the study of 25 markers, the cost includes testing of two additional relatives, whose participation may increase the accuracy of the analysis. standard conclusion. | 2 participants: relationship is determined (not further than 3 degrees of relationship) between grandfather / grandmother - grandson / granddaughter, uncle / aunt - nephew / niece (avuncular test), siblings / half-siblings (full- and half-sibling ), twin test. | Standard sample | 14000 | 5 w.d. |

A-2.2 | RELATIONSHIP STUDY, 25 markers. standard conclusion. | 2 participants (not more than 3 degrees of relationship): grandfather / grandmother - grandson / granddaughter, uncle / aunt - nephew / niece (avuncular test), siblings / step-siblings (full- and half-sibling, twin test ) | Standard sample | 11900 | 3 w.d. |

A-2.6 | MALE RELATIONSHIP TEST, Y-chromosome test. standard conclusion. | 2 members: paternal grandfather-grandson, uncle-nephew, siblings/half-brothers | Standard sample | 12000 | 5 w.d. |

A-2.7 | RELATIONSHIP TEST, X chromosome test. standard conclusion. standard conclusion. | 2 members: paternal grandmother - granddaughter, paternal half-sisters | Standard sample | 12000 | 5 w.d. |

A-2.8 | STUDY FOR RELATIONSHIP ON THE FEMALE LINE AT ANY DISTANCE OF RELATIONSHIP, the study of mitochondrial DNA. standard conclusion. | 2 members | Standard sample | 28000 | 20 w.d. |

A-5 FORENSIC MOLECULAR GENETIC EXAMINATION | |||||

A-5.1 | FORENSIC PATERNITY/MATERNALITY MOLECULAR GENETIC EXAMINATION (DUET), 25 markers | 2 members: 1 Intended Parent, 1 Child | Standard sample | 14000 | 5 w.d. |

A-5. 2 2 | PATERNITY/MATERNITY FORENSIC MOLECULAR GENETIC EXAMINATION (TRIO), 25 markers | 3 members: 1 Intended Parent, 1 Unconditional Parent, 1 Child | Standard sample | 14000 | 5 w.d. |

A-5.3 | FORENSIC MOLECULAR GENETIC EXAMINATION FOR RELATIONSHIPS IN REGARD TO A MARRIED COUPLE, 25 markers | 3 members: Intended Mother, Intended Father, Child | Standard sample | 14000 | 5 w.d. |

A-5.4 | 25 markers | 3 members: grandparents by intended parent, child | Standard sample | 19000 | 5 w.d. |

A-5.5 | FORENSIC MOLECULAR GENETIC EXAMINATION TO ESTABLISH OTHER RELATIONSHIPSDepending on the type of relationship being investigated and the possibility of providing DNA samples of additional relatives, up to 40 DNA markers, X or Y chromosome markers, are examined. In the study of 25 markers, the cost includes testing of two additional relatives, whose participation may increase the accuracy of the analysis. In the study of 25 markers, the cost includes testing of two additional relatives, whose participation may increase the accuracy of the analysis. | 2 participants: relationship is determined (not further than 3 degrees of relationship) between grandfather / grandmother - grandson / granddaughter, uncle / aunt - nephew / niece (avuncular test), siblings / half-siblings (full- and half-sibling ), twin test. | Standard sample | 18000 | 7 w.d. |

A-5.10 | FORENSIC MOLECULAR GENETIC EXAMINATION TO ESTABLISH MALE RELATIONSHIP, Y-Chromosome | 2 members: paternal grandfather-grandson, uncle-nephew, siblings/half-brothers | Standard sample | 15000 | 7 w.d. |

A-5.11 | FORENSIC MOLECULAR GENETIC EXAMINATION TO ESTABLISH RELATIONSHIP, X-chromosome testing | 2 members: paternal grandmother-granddaughter, paternal half-sisters | Standard sample | 15000 | 7 w. d. d. |

A-5.12 | FORENSIC MOLECULAR GENETIC EXAMINATION FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF RELATIONSHIP ON THE FEMALE LINE AT ANY DISTANCE OF RELATIONSHIP, the study of mitochondrial DNA | 2 members | Standard sample | 30000 | 25 w.d. |

C NON-INVASIVE PRENATAL TESTING | |||||

C-1 | FETUS SEX DETERMINATION (from the 9th week of pregnancy, biomaterial - venous blood) when blood is delivered to the laboratory within 48 hours, a CPDA tube, 9 ml is used | Venous blood | 6900 | 5 w.d. | |

S-2 | DETERMINATION OF FETAL rhesus factor on mother's blood, when blood is delivered to the laboratory within 48 hours, a CPDA tube, 9 ml is used | Venous blood | 10000 | 5 w. | |