How to engage a child with autism

How to Engage Autistic Kids

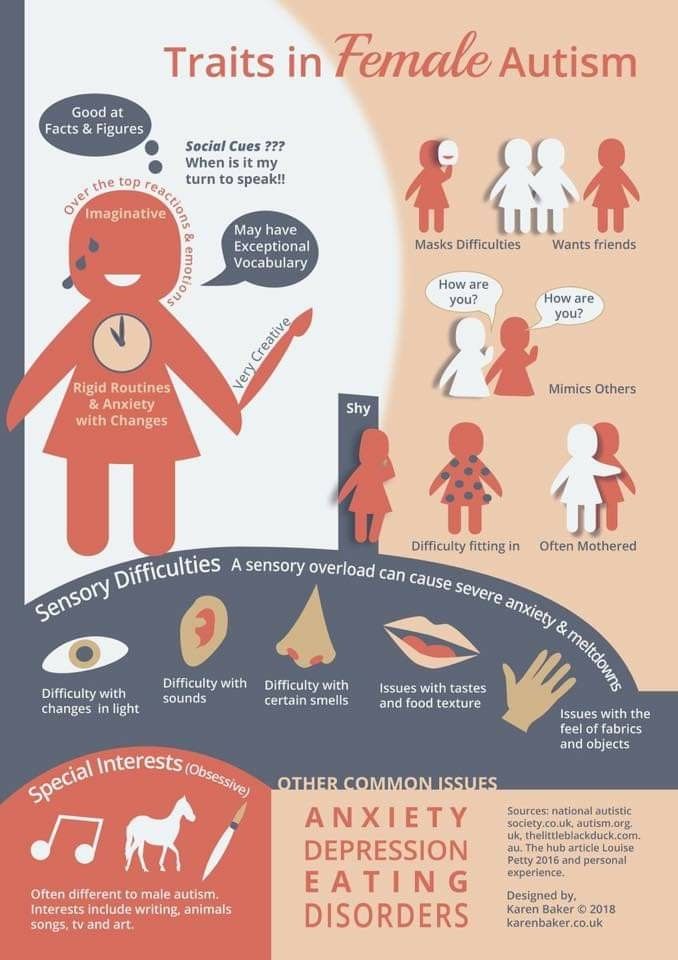

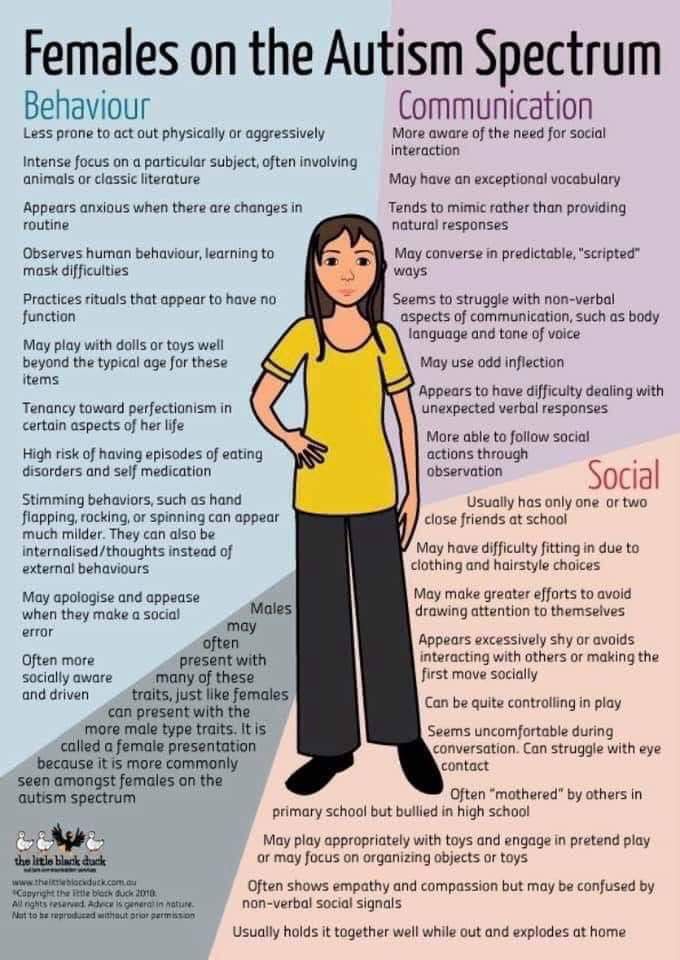

If it seems like you hear a lot more about autism these days, you're right. Its prevalence has grown significantly (an estimated 10-fold growth over the past 40 years). The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention estimate that one in 68 American children are on the autistic spectrum. Chances are, you know a child with autism. What might be even more surprising is the significantly higher numbers in boys; it's estimated that 1 in 42 boys are diagnosed with autism versus 1 in 189 girls.

Why is autism so prevalent?

Part of the rise in autism has been attributed to increased awareness and improved diagnosis. Techniques have been improved and more professionals have been trained to properly identify autism. This, however, only explains part of the rise. Research suggests a combination of genetic and environmental causes, the latter including factors like problems during birth, parents having children at older ages, or mothers taking prescription drugs like valproic acid and thalidomide during pregnancy.

What can parents do?

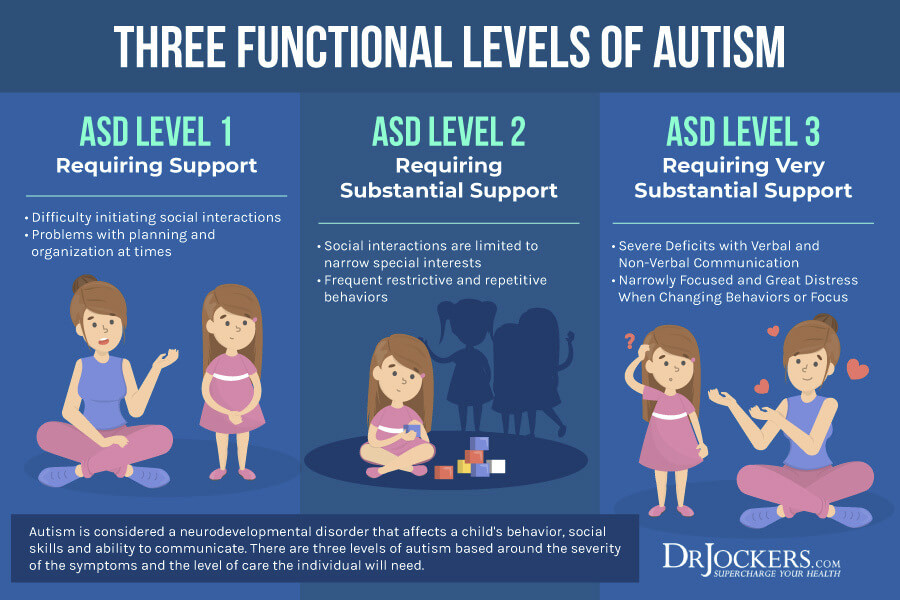

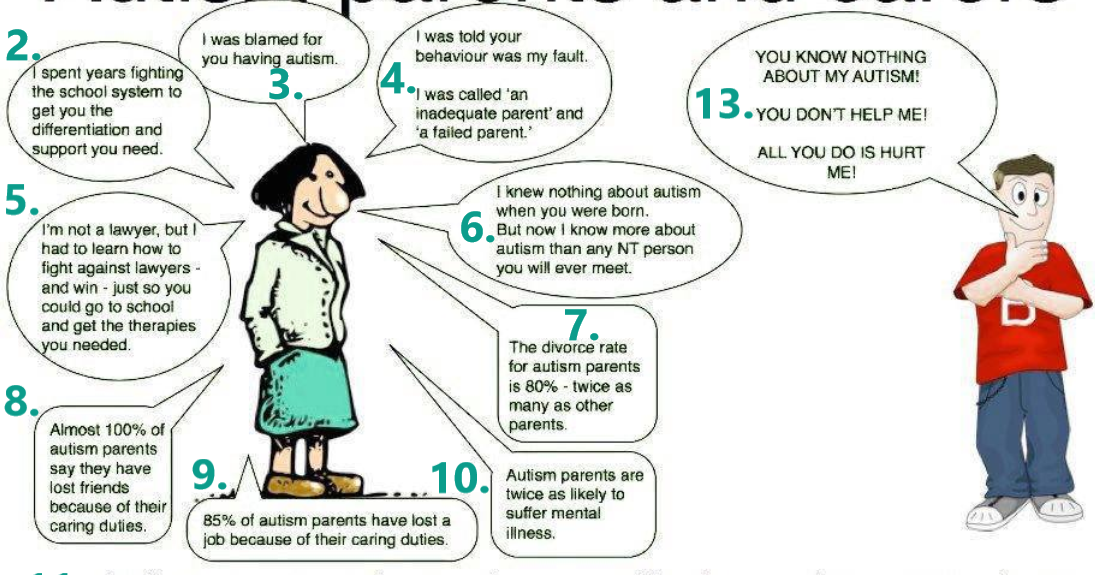

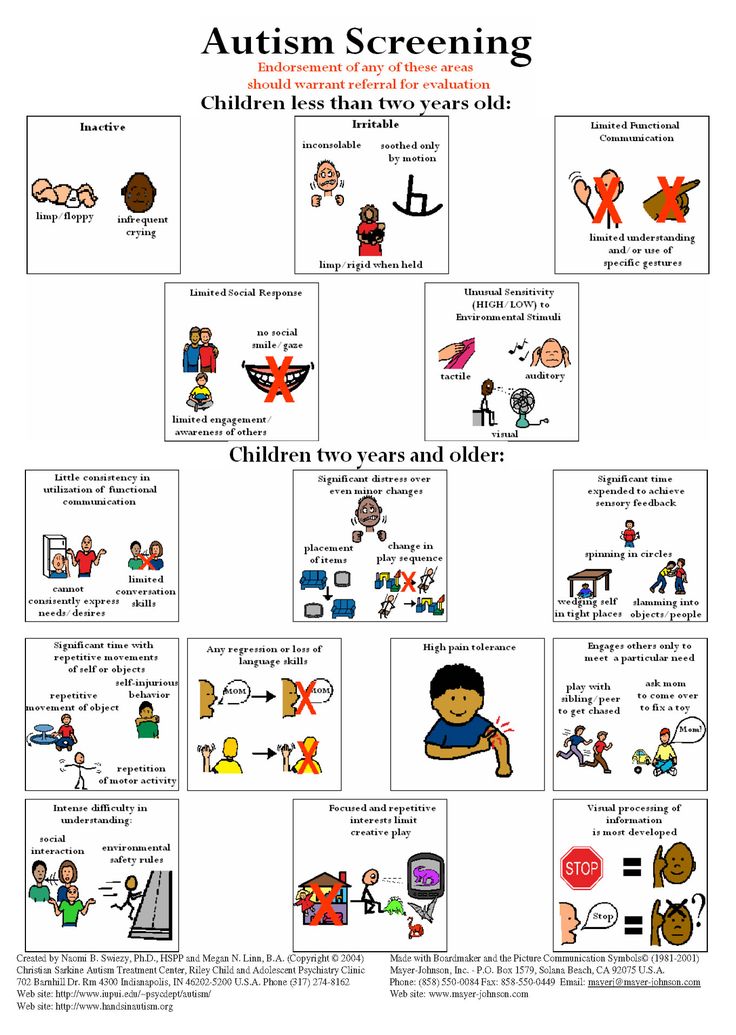

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often have problems with social interaction, emotions, and communication. The challenges depend on their specific condition and its severity, but early intervention can significantly improve children's conditions. So, it's important to work with a doctor or trained expert as soon as possible to confirm the condition and develop a specific plan. In many cases, therapy and other services are available from local and state organizations.

How can we engage autistic children?

For Communication Skills:

- Children typically begin to talk about the future and past, and in conversational formats once they reach their preschool years (3 to 5 years old). Kids also grow their vocabulary size immensely during this time.

- Provide children with the opportunity to create their own story narratives, perhaps focusing on a favorite book or TV character.

- Teach children how to ask questions and listen to others, such as a pretend interview game.

For Social Skills:

- Provide children with opportunities to mimic appropriate behavior from adult role models. These opportunities can take the form of live conversations and activities with parents and other adults, or through role-playing games and programs where a role-model "character" helps kids navigate various challenges.

- Focus on all-inclusive, team-oriented activities in environments where children have the opportunity to work with and befriend other children.

For Motor Skills:

- For gross motor skills: obstacle courses, dance games, and balancing and jumping games can help develop muscle tone and coordination -- begin with least-threatening activities, and introduce new activities gradually.

- For fine motor skills, coloring and tracing games can help kids develop pencil grasp and hand-eye coordination.

For Sensory Integration:

- Children who are sensory seekers tend to be attracted to physical activity, such as jumping, moving, lifting, pushing, and pulling (trampolines, obstacle courses).

- Children who are sensory sensitive can benefit from calming activities that avoid triggers (strong smells, lights, and sounds) and help kids feel more grounded, as well as smooth transitions.

- For example, have kids help with preparing meals or baking, like mixing and rolling dough.

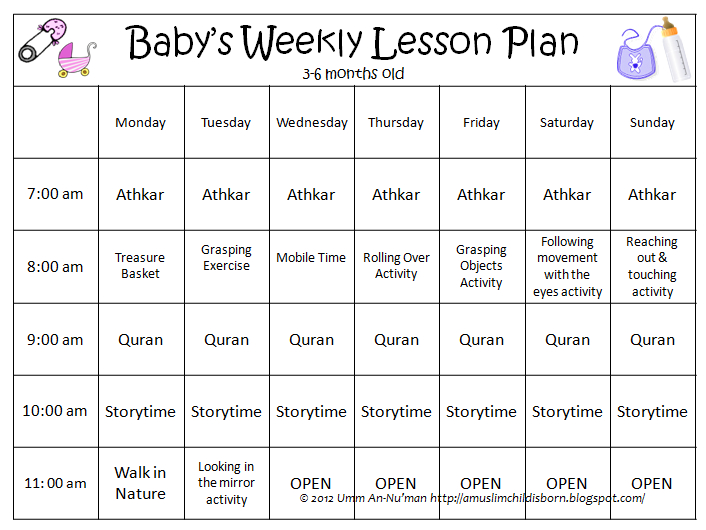

- Consistent routines and activity schedules can help children feel more secure.

People with ASD can be found in every area of life. Many of the specifics conditions -- attention to detail, deep knowledge, highly-developed skills in a specific area, and strong memories -- can be strengths for particular fields and professions. Again, much depends on the severity as well as how quickly it is diagnosed and treated.

Do you have a story to share? I'd love to hear your thoughts on the Scholastic Parents Facebook page!

Featured Book

learn more

GRADES

30 Activities, Teaching Strategies, and Resources for Teaching Children with Autism

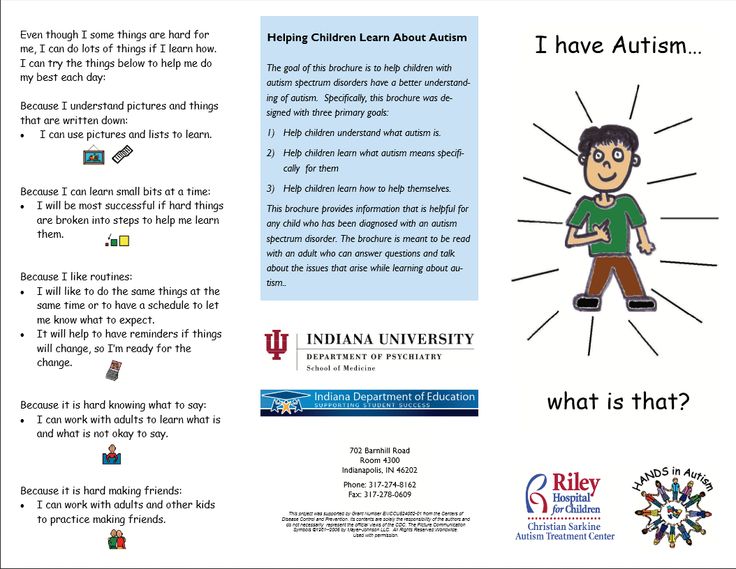

Because approximately 1 in 59 students are diagnosed with autism, learning how to help students with this disorder in the classroom is so important. [1] Teaching young students with autism communication skills and learning strategies makes it all the more likely that they’ll reach their academic potential later on. And the more you learn about autism spectrum disorder, the better you’ll be able to prepare these students for lifelong success.

[1] Teaching young students with autism communication skills and learning strategies makes it all the more likely that they’ll reach their academic potential later on. And the more you learn about autism spectrum disorder, the better you’ll be able to prepare these students for lifelong success.

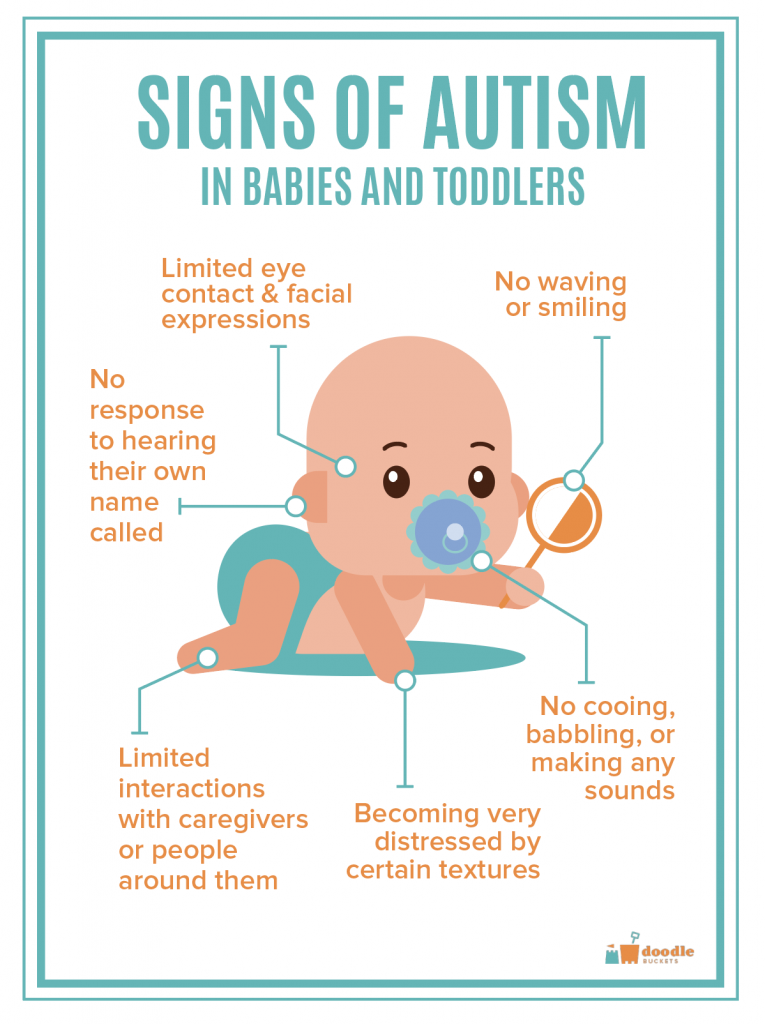

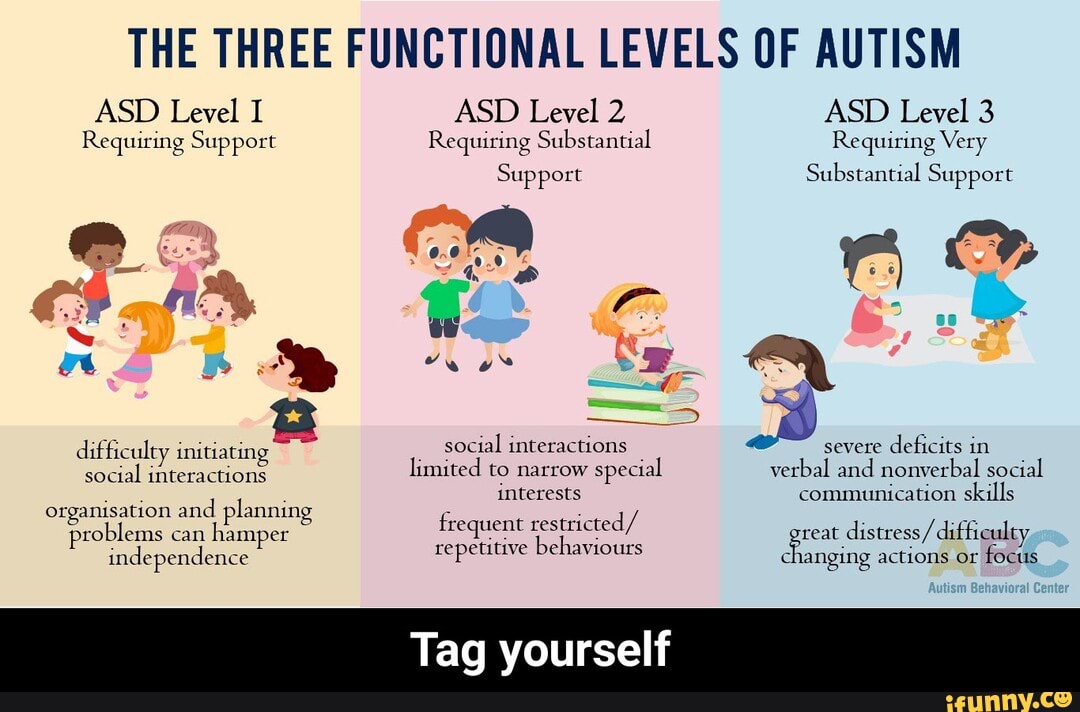

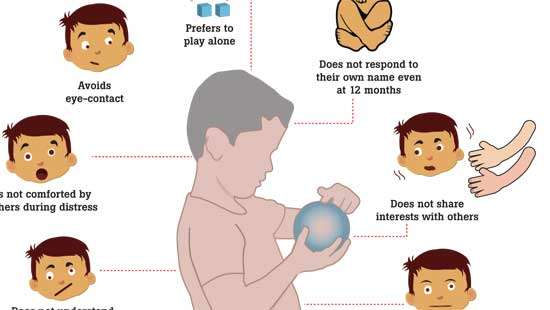

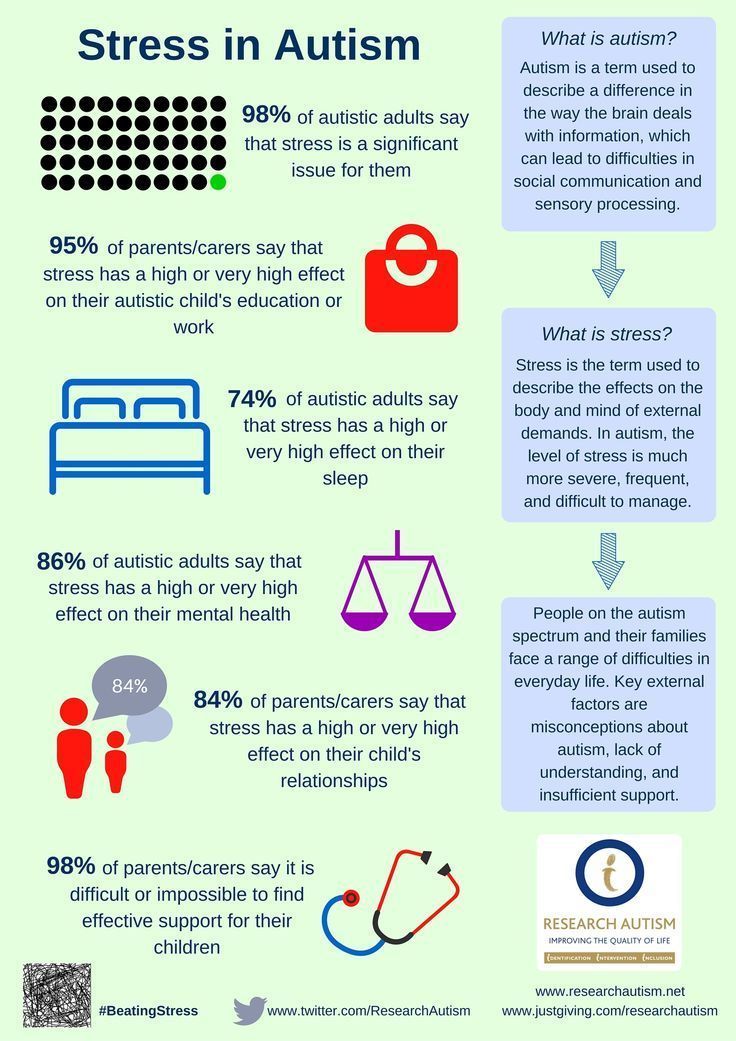

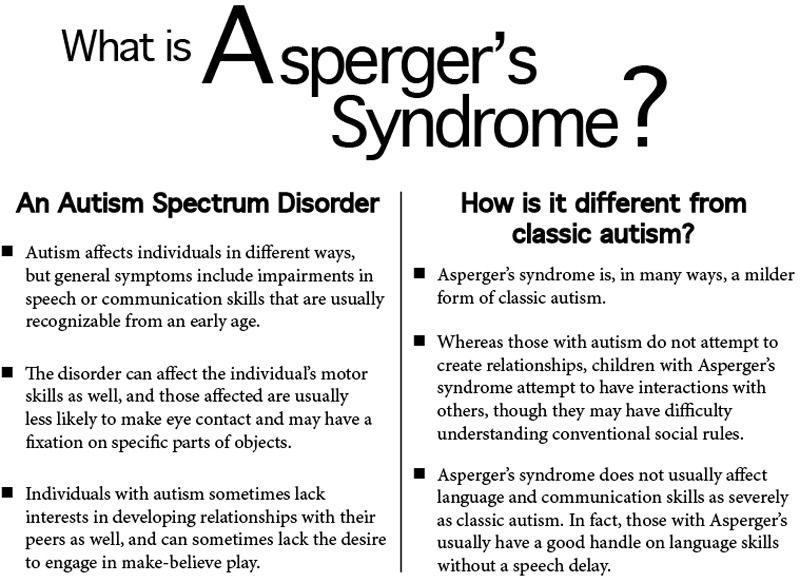

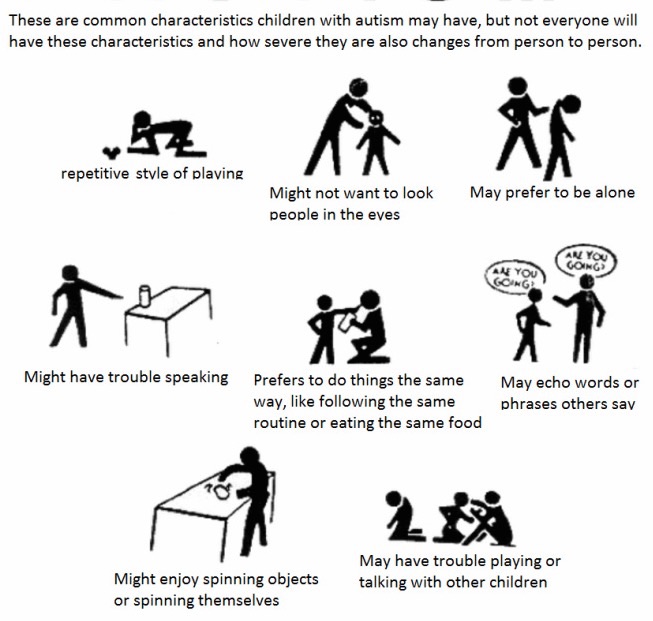

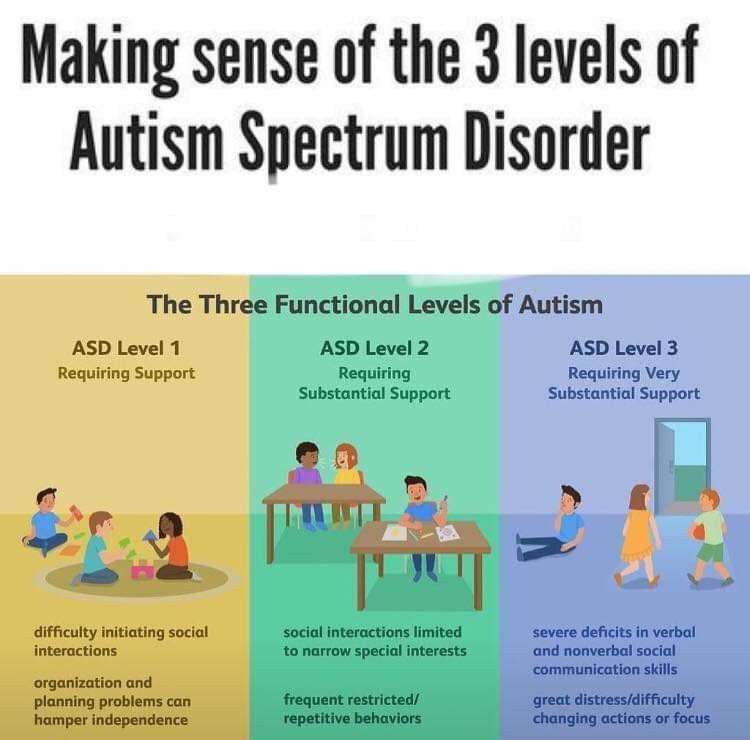

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability that causes hypersensitivity to sights, sounds, and other sensory information. Symptoms of autism generally fall into three categories:[2]

- Communication issues

- Social impairment

- Repetitive behaviors (known among the autism community as “stimming”)

Here are 15 fun activities to help children with autism feel welcome in your class while addressing their symptoms and individual learning styles. Whether you play them one-on-one or as group activities, these are excellent ways to keep students with autism engaged and ready to learn.

Social Skills Activities for Elementary Students with Autism

A common characteristic of students with autism is trouble communicating or connecting with their classmates. Use these social skills activities to teach kids with autism how to recognize social cues, practice empathy, and learn other important life skills.

Use these social skills activities to teach kids with autism how to recognize social cues, practice empathy, and learn other important life skills.

1. Name Game [3]

This fun group communication activity teaches students with autism an essential skill: how to introduce themselves and learn someone else’s name. To play this game, gather your students in a circle so they can all see each other. Start by pointing at yourself and saying your name (“I am Mr. or Ms. _____.”). Then, ask the child on your right to share their name just like you did and then repeat your name while pointing at you. Have each child take turn saying their name, then pointing at another child in the class and repeating their name.

The Name Game is an especially fun social skills activity for children with autism to do at the beginning of the school year. That way, they’ll be able to learn their classmates’ names and get a head start on making new friends.

2. “How Would It Feel to Be ____?” [4]

Next time you read a book to your class, try asking your students how it would feel to be the main character in the story. If you’re reading a picture book about Cinderella, for example, you could ask how they would feel if they had two evil stepsisters who were mean to them. Or if you’re reading Peter Pan as a class, you could ask them what happy memories they would think about to fly with magic pixie dust.

If you’re reading a picture book about Cinderella, for example, you could ask how they would feel if they had two evil stepsisters who were mean to them. Or if you’re reading Peter Pan as a class, you could ask them what happy memories they would think about to fly with magic pixie dust.

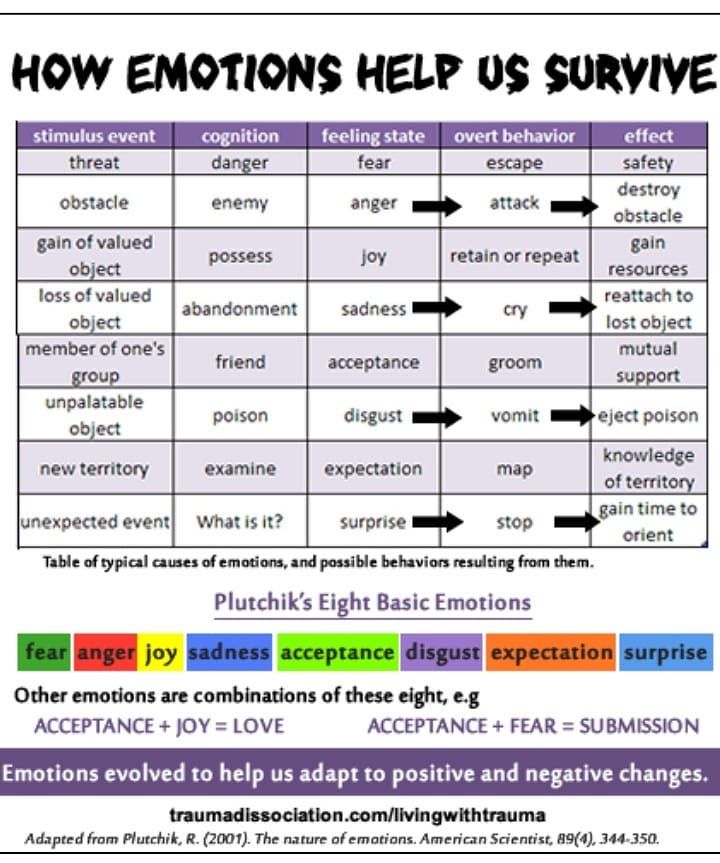

This can help students with autism learn empathy as well as how to see situations in their lives from another perspective. It can also teach them how to recognize emotional cues by encouraging them to put themselves in the perspective of another person.

3. Sharing Time [5]

Sharing time is a classic elementary school staple, and it can also be a great social-emotional learning (SEL) activity for kids with autism. Every week, have one kid in your class bring something that they’d like to share with the class. This will not only show students with autism how to discuss their interests with others but also how to practice active listening. And if they’re fascinated by something another student brings in (or vice versa), they may even make a friend.

4. Emotion Cards

These printable cards for students with autism can help them learn how to recognize different emotions in themselves and others. Cut out each one with scissors and shuffle them in a deck. Then, go through each card and see if your student can recognize the emotion without looking at the word.

If they get stuck, that’s okay—just show them the word and give them context for the emotion shown. If the card is “embarrassed,” for example, you could say, “When a person is embarrassed, they might feel like they have done something silly or wrong on accident.”

5. Board Games with a Twist

Teaching children manners can be a helpful way to boost social skills and explain the importance of being polite. This simple, but effective activity puts an etiquette-related twist on a simple game of chess, checkers, or mancala by requiring players to wish their opponent “good luck” or “good game” before and after they have played.

6. What Would You Do?

For a take-home activity you can share with families, try this What Would You Do? game. Families can go through different scenarios together and decide how they would react with questions like “How would you help?” or “What would you say?”

Families can go through different scenarios together and decide how they would react with questions like “How would you help?” or “What would you say?”

This activity keeps social skills sharp and reinforces relationship-building skills.

Sensory Activities for Children with Autism

Because children with autism are often hyper aware of sensory input, it’s helpful for educators to provide accommodations so their students can focus in class. These activities involving sensory stimulation can keep kids with autism grounded in the present and comfortable learning with the rest of their classmates.

7. Sorting with Snacks Activity [6]

This tactile activity for children with autism can be a fun way to engage students during math time. Give everyone in your class a food that is easy to sort, like chewy snacks or small crackers. Multicolored snacks are ideal, but you can also use food that comes in different shapes, textures, or sizes.

First, ask them to sort the food by color, shape, or another characteristic. Then, use the snacks to teach students basic math skills like counting, adding, or subtraction. Once they’ve grasped the concept you want to teach, reward your students by letting them eat the snack.

Then, use the snacks to teach students basic math skills like counting, adding, or subtraction. Once they’ve grasped the concept you want to teach, reward your students by letting them eat the snack.

8. Vegetable Paint Stamps [7]

This art activity for children with autism engages touch and sight to keep students focused on their assignment. Before class begins, cut slices of vegetables like potatoes, cucumbers, or peppers. Hand out a few vegetable slices to each child along with a cup of paint. Instruct your students to dip the bottom of the vegetable slice into the paint and then press it against a piece of paper.

As your students use these homemade stamps, they will make vibrant botanical impressions on their paper. From there, your students can either leave them as they are or finger paint to transform them into whimsical artwork.

9. Scientific Slime Experiments

Slime is not only a popular craft for young children but also a great sensory activity for autism in class. There are plenty of simple slime recipes online–look up your favorite and have fun making it with your students. You can use this as a tactile art activity if you’d like or as a science activity for elementary students.

There are plenty of simple slime recipes online–look up your favorite and have fun making it with your students. You can use this as a tactile art activity if you’d like or as a science activity for elementary students.

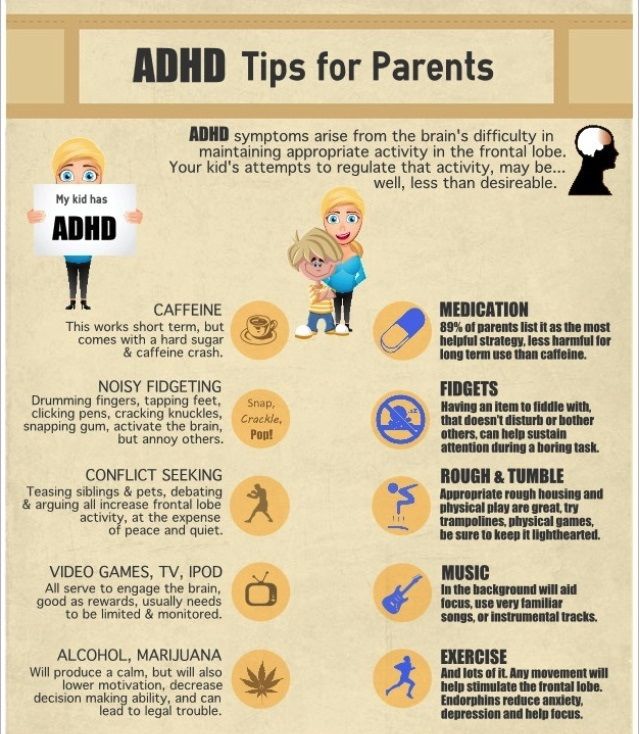

10. Fidget Toys

Fidget toys are a well-known sensory tool for helping children with autism and other sensory processing disorders stay calm and focused. Depending on your available resources, you can either stock your classroom with a few fidget toys or make some of your own.

We Are Teachers has compiled a list of eleven fidget toys you can make on a budget with your students. From classics like fidget spinners to repurposed pipe cleaners or popsicle sticks, you’re sure to find something useful for your classroom.

11.Auditory Sensory Play

When the phrase “sensory play” comes up, visual or textual activities usually come to mind first. Autism Adventures, however, suggests including activities that involve sound—with a few examples to get you started:[15]

- Musical chairs

- White noise machine

- Simon Says

- Noise-cancelling headphones

- Rhythm instruments like shakers, rain sticks, or drums

12.

Sensory Bin

Sensory BinSensory bins can be useful for two reasons. First, they encourage differentiated instruction or independent play—both of which can have academic benefits for students. And second, they’re a straightforward and accessible sensory experience for students with autism.

The Kindergarten Smorgasbord has put together a few useful tips for making your own sensory bin. Use them as a guide to set up a sensory bin that will best accommodate your students’ needs.

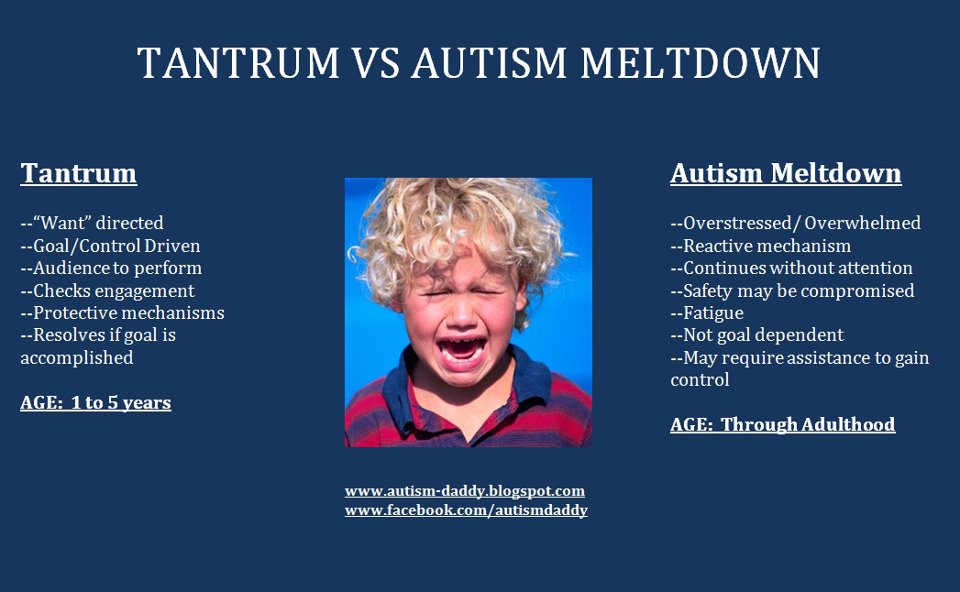

Calming Activities to Prevent Autism Meltdowns in Class

When students with autism are feeling overwhelmed, the intense response that they feel may cause them to lose control of their emotions. This is called an “autism meltdown” and is different from when students without autism act out in class. While the best strategy for autism meltdowns is to seek help from a school specialist, these calm down activities can help to de-escalate stressful situations.

13. Grounding Techniques

Grounding techniques are designed to help us focus on the present during stressful situations. Here are a few grounding activities for kids with autism to try if they seem agitated:[8]

Here are a few grounding activities for kids with autism to try if they seem agitated:[8]

- Count to ten or recite the alphabet as slowly as you can

- Listen to calming music and pay attention to the different instruments

- List five different things that you can see around the room

- Try stretching or simple yoga exercises and focus on how your body feels

- Hold something tactile like a piece of clay or a stuffed animal

For older students with autism, you could also try mindfulness meditation. This can produce a similar effect and help students tune into the present rather than getting carried away by their emotions.

14. Student Retreat Zone [9]

When a student with autism is overwhelmed, giving them a place where they can relax and take a break from sensory stimulation can sometimes go a long way. Designate a corner of your class as the “Student Retreat Zone” and fill it with sensory toys, picture books, comfortable seats, and calming activities that students with autism could do on their own.

Let every student in your class know that if they feel anxious or stressed, they can always take a few minutes to decompress in the Student Retreat Zone. That way, you don’t have to single your student with autism out but still let them know that it’s an option. If your student with autism seems like they could use some time away from class, you could also ask them if they’d like to read or work on homework in the library for a while.

15. Calm Down Drawer [10]

Tactile toys can help children with autism calm down if they’re agitated since their minds are so attuned to sensory information. If you have children with autism in your class, fill a drawer in your classroom with toys that could help neutralize overwhelming emotions. When your student seems stressed or has trouble focusing, give them a sensory toy or two to help them relax.

Here are a few ideas for sensory toys to put in your “calm down drawer:” [11]

- Play dough

- Fidget toys

- Stress balls

- Weighted blankets

- Aromatherapy pillows

16.

Coloring

ColoringAccording to a partner article by The National Institute for Trauma and Loss in Children published by We Are Teachers, coloring pages can be a great mind-body exercise for calming down and focusing on the here and now.[16]

Keep a few coloring pages on hand, and suggest them as a calm-down activity when your students are overwhelmed. For a few free coloring pages to get you started, check out this resource from Disney.

17. Calm-Down Cards

If your student with autism struggles with calming down after feeling strong emotions, calm-down cards can be a helpful resource. A mother whose child has autism has created a how-to on creating your own calm-down cards at And Next Comes L.

Each card has a helpful idea for calming down after a stressful moment. Plus, the author notes they can also be useful for children with anxiety—a great resource for your classroom to have.

18. Mindful Breathing

Mindfulness is a technique that encourages children to keep their mind in the present and deal with uncomfortable emotions. If your student is struggling to calm down, try watching this mindful breathing video to help them regain composure.

If your student is struggling to calm down, try watching this mindful breathing video to help them regain composure.

Effective Teaching Strategies for Children with Autism

In some cases, the learning characteristics of students with autism may differ from the rest of your class. But luckily, the right teaching strategies and methods can keep children with autism on track to finish the school year strong. Try these tips, educational accommodations, and resources for students with autism to help them learn concepts that might otherwise be difficult for them to grasp.

19. Bring Special Interests Into Lesson Plans [12]

Many children with autism have a fixation on certain topics or activities. Take advantage of what they’re passionate about and use it while teaching students with autism to help them focus in class. If a child with autism loves outer space, for example, you could plan a math assignment about counting the planets in our Solar System.

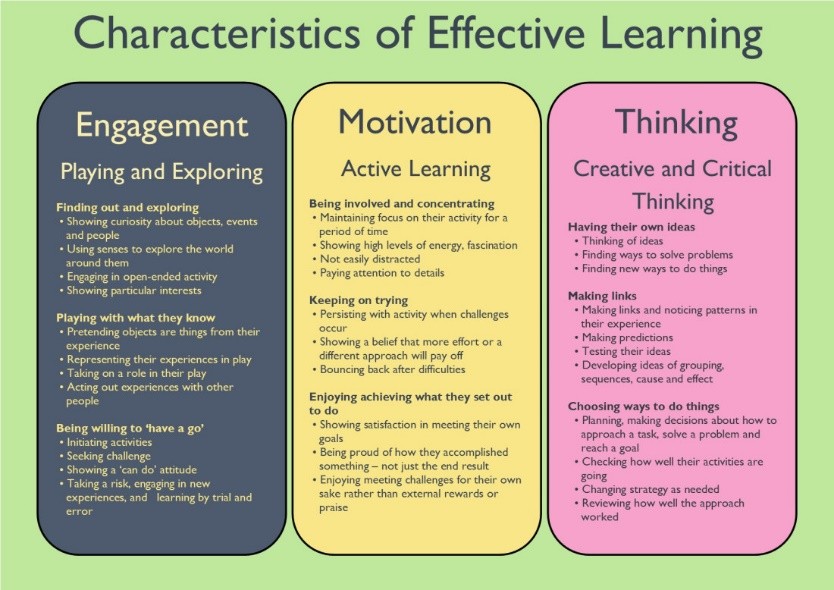

20. Use Multisensory Learning

Many kids with autism are multisensory thinkers and don’t focus as well when assignments only engage one of their senses. Renowned scientist and autism advocate Dr. Temple Grandin once said, “I used to think adults spoke a different language. I think in pictures. Words are like a second language to me.” [13]

Renowned scientist and autism advocate Dr. Temple Grandin once said, “I used to think adults spoke a different language. I think in pictures. Words are like a second language to me.” [13]

For this reason, lessons that engage several senses like sight, hearing, and touch can make students with autism more responsive in class. You could, for example, teach children with autism how to read with magnet letters or sing a patriotic song to learn about American history.

21. Try a SMART Goal Challenge

If a student with autism is having a hard time with school, sit down with them and pick a SMART goal to work on over the next month or semester. SMART goals are an effective way to help children with autism reach their potential, and they are: [14]

- Specific

- Measurable

- Agreed-upon

- Relevant

- Time-bound

Suppose, for example, that your student with autism is having trouble learning how to recognize emotions. You could make a goal with them to practice flash cards with emotions on them every day for five minutes and for the student to recognize each card by the end of the month. As long as the SMART goal hits all of the criteria, it can help your student focus on ways to make progress.

You could make a goal with them to practice flash cards with emotions on them every day for five minutes and for the student to recognize each card by the end of the month. As long as the SMART goal hits all of the criteria, it can help your student focus on ways to make progress.

22. Provide Clear Choices

According to educators at the special education program of St Joseph’s University, children with autism may become overwhelmed when given too many options.[17] Keep this in mind while creating assignments for your students or asking them questions in class. That way, you’re more likely to keep your student with autism focused and comfortable choosing an answer.

23. Create a Strong Classroom Routine

In an article with Scholastic, educator Kim Greene reminds teachers that students with autism work best with a strong daily structure.[18] She suggests posting your class schedule for every student to see and, if possible, providing visuals and extra transition time to students with autism.

24. Offer Accommodations for Students with Limited Motor Skills

Some students with autism may have more trouble with activities that require fine motor skills than others. In an article with the Indiana Resource Center for Autism, renowned scientist and advocate Dr. Temple Grandin suggests offering accommodations—like typing on a computer instead of writing—to mitigate these challenges.[19]

When it comes to specific accommodations, it may depend on the individual. It’s always a good idea to reach out to a student’s family to determine the best resources for their child.

Activities for Autism Awareness Month in April

April is Autism Awareness Month, a time when we celebrate neurodiversity and help students with autism feel welcome in private or public schools. Although parents may not want their child’s autism diagnosis to be shared (and you never should without their permission), you can still teach your class about inclusion this month without mentioning a certain student.

Use these three games as autism awareness activities during April or whenever you want to teach a lesson on diversity.

25. “Just Like Me” Activity

For this activity, gather all of your students together on the floor so they can all see each other. Have each child take turns sharing something about themselves, like:

- “I have a pet dog.”

- “I can play the piano.”

- “My birthday is in September.”

- “I love to play soccer.”

- “My favorite color is yellow.”

If a statement also applies to other students (like, for example, they also play the piano), instruct them to raise their hands. This will help remind students that they share more similarities than differences with their peers and that they can always find something to talk about.

26. Picture Books About Diversity

By reading a story about inclusiveness to your class, you can help them remember to be kind to everyone and look out for people who are different.

Here are a few picture books about diversity that you can share with your students:

- The Sneetches and Other Stories by Dr. Seuss

- I’m New Here by Anne Sibley O’Brian

- It’s Okay to Be Different by Todd Parr

- Everywhere Babies by Susan Meyers and Marla Frazee

- The Girl Who Thought In Pictures: The Story of Dr. Temple Grandin by Julia Finley Mosca

The last book on this list, The Girl Who Thought in Pictures, is about a famous researcher who was diagnosed with autism and has since stood as an activist for people with her condition. It is perfect for helping kids understand autism a little better without calling out a specific student.

27. Apples and Actions Game [15]

This object lesson starts with showing your student an apple. Pass the apple around the class and, as you do, have each child insult it and drop it on their desk or the ground. After every child has dropped it and said a mean thing to it, cut the apple in half and show your students all the bruises inside.

Explain to them that our words have consequences and that everything we say can make an impact on someone else. Just like how insulting and dropping the apple can bruise it, being mean to a classmate can have big effects on them. That way, your students will always remember to be kind.

28. Autism Bulletin Board

The puzzle piece is a popular autism awareness symbol. For a simple yet meaningful way to teach your students about autism awareness, create this puzzle piece bulletin board from Mrs. D’s Corner. Each piece fights against negative stereotypes by reminding your students that people with autism are intelligent, empathetic, important, and so much more.

29. Teach Students About Historical Figures with Autism

Although the disorder wasn’t discovered until the twentieth-century, people with autism have made important contributions to history, and it’s important to educate students about them—not just in April but throughout the year. Here are a few well-known figures who are diagnosed with or believed to have had autism to get you started:[20]

- Greta Thunberg

- Vincent van Gogh

- Temple Grandin

- Albert Einstein

- Emily Dickinson

30.

Hold a Professional Development Session on Autism

Hold a Professional Development Session on AutismIt’s so important to teach faculty about autism awareness, too. If you’re a school administrator, consider holding a professional development session on teaching students with autism or sharing a few resources.

For example, the Regional Educational Laboratory Program has put together a helpful resource for administrators on how educators can support students with autism during remote learning.

Sources:

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

- The National Institute for Mental Health. A Parent’s Guide to Autism Spectrum Disorder. https://www.autism-watch.org/general/nimh.pdf

- Shapiro, L.E. 101 Ways to Teach Children Social Skills. The Bureau for At-Risk Youth, 2004.

- Dougan, R. Social Emotional Learning Guidebook: Ideas for Incorporating SEL Activities into your Classroom.

https://www.dvc.edu/faculty-staff/pdfs/SEL-Guidebook.pdf.

https://www.dvc.edu/faculty-staff/pdfs/SEL-Guidebook.pdf. - Shapiro, L.E. 101 Ways to Teach Children Social Skills. The Bureau for At-Risk Youth, 2004.

- Autism Parenting Magazine. Sensory Play Ideas and Summer Activities for Kids with Autism. https://www.autismparentingmagazine.com/best-sensory-play-ideas/.

- Autism Speaks. 10 Fun Summer DIY Sensory Games for Kids. https://www.autismspeaks.org/blog/10-fun-summer-diy-sensory-games-kids.

- Noelke, K. Grounding Worksheet. https://www.winona.edu/resilience/Media/Grounding-Worksheet.pdf.

- Tullemans, A. Self-Calming Strategies. Autism Spectrum Disorder News, July 2013, 23.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Retrieved from cdc.gov: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

- Larkey, S. Strategies for teaching students with Autism Spectrum Disorder and other students with special needs.

Learning Links: Helping Kids Learn, 3, pp. 1-5.

Learning Links: Helping Kids Learn, 3, pp. 1-5. - Blanc, M. Finding the Words… When They Are Pictures! Helping Your Child Become Verbal! Part 1. Autism/Asperger’s Digest, May-June 2006, pp. 41-44.

- Larkey, S. Strategies for teaching students with Autism Spectrum Disorder and other students with special needs. Learning Links: Helping Kids Learn, 3, pp. 1-5.

- Penn State Extension. More Diversity Activities for Children and Adults. R https://extension.psu.edu/more-diversity-activities-for-youth-and-adults.

- Autism Adventures. Sensory Play in the Classroom. www.autismadventures.com/sensory-play-in-the-classroom/

- The National Institute for Trauma and Loss in Children. 5 Calming Mind-Body Exercises to Try With Your Students. We Are Teachers. April 2018. https://www.weareteachers.com/mind-body-skills/.

- Saint Joseph’s University. Techniques for Teaching Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. https://online.

sju.edu/graduate/masters-special-education/resources/articles/techniques-for-teaching-students-with-autism-spectrum-disorder.

sju.edu/graduate/masters-special-education/resources/articles/techniques-for-teaching-students-with-autism-spectrum-disorder. - Greene, K. Teaching Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/teaching-students-autism-spectrum-disorder/.

- Grandin, T. Teaching Tips for Children and Adults with Autism. Indiana Resource Center for Autism. https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/irca/articles/teaching-tips-for-children-and-adults-with-autism.html.

- Autism Community Network. Famous—With Autism. https://www.autismcommunity.org.au/famous—with-autism.html.

How to attract the attention of a child with autism during class?

07/21/15

Recommendations of a behavioral analyst to keep the attention of a child with autism

Author: Tameik Midose / Tameika MEADOS

Source: I Love ABA

9000 9000 9000

) child (teacher, parent, therapist), he understands how important it is to attract and keep the attention of the child. Even if you started a class with an obedient, quiet and attentive student, there is no guarantee that he will remain the same by the end of the class. ABA instructions may include specific requirements at a fast pace, and if the child is not focused on learning, it can be difficult to assess progress.

Even if you started a class with an obedient, quiet and attentive student, there is no guarantee that he will remain the same by the end of the class. ABA instructions may include specific requirements at a fast pace, and if the child is not focused on learning, it can be difficult to assess progress.

Even outside of an ABA session, getting and keeping the attention of a child with autism can be a challenge. When I see non-ABA professionals interacting with children with autism, most often they start bombarding the child with instructions. They may make demands on a child who is absorbed in watching DVDs, sits with his back to them and vocalizes. I do not blame the child for not fulfilling their requirements in such a situation. How can a child fulfill the request "Come to dinner" when he, at best, heard ".. nah"?

What most adults consider signs of attention (maintaining eye contact, immediate response) is difficult behavior for a child with autism. Self-stimulation can interfere with attention, as can hearing problems. For example, if I'm at a play center with a client and I'm trying to give them instructions, I'll have to compete with the noise of other kids yelling and laughing, the noise of the air conditioner, and the sound effects of the nearest video game machine. It will be difficult for my client to filter out all this noise in order to focus on what I am saying.

For example, if I'm at a play center with a client and I'm trying to give them instructions, I'll have to compete with the noise of other kids yelling and laughing, the noise of the air conditioner, and the sound effects of the nearest video game machine. It will be difficult for my client to filter out all this noise in order to focus on what I am saying.

Socialization problems also make it difficult for a child with autism to pay attention during class. Looking directly into my eyes can be very uncomfortable for the child, and if I require him to "look into my eyes", the resulting discomfort will prevent him from concentrating on what I am saying. In other situations, physical proximity to me may be unpleasant for him, and this may make it difficult for him to understand my words. When we are trying to get and keep the attention of a child with autism, we must consider all of these factors.

It seems to me that everyone already knows this, but just in case, let me remind you: if a person with autism does not look you in the eyes, this does not mean that he does not listen to you. I know that many teachers believe that if a child looks at the floor when they are talking to him, then this is a sign of disrespect. However, a child with autism may look away from you precisely because he is trying to focus on your speech.

I know that many teachers believe that if a child looks at the floor when they are talking to him, then this is a sign of disrespect. However, a child with autism may look away from you precisely because he is trying to focus on your speech.

Here are some attention-getting ideas:

Things to avoid

Do not call your child by name. It's best not to give the child's name at all when you're trying to get their attention during class. Otherwise, you can literally repeat it hundreds of times in two hours. In the end, you just teach the child that his name always means some kind of requirement. Imagine that during work, your boss does nothing but shout your name, and each time it ends up with you having more cases. How quickly do you start to flinch and feel annoyed every time your boss says your name? Pretty fast. So it's very important not to combine the child's name with the job ("Aidan, show me a cup", "Aidan, give me a yellow", "Aidan, how old are you").

Do not touch the child's face or turn his head. Apart from the fact that this has nothing to do with real attention (the child may turn his face in your direction, but still not look at you), these actions are very unpleasant for the child. Imagine that you are bored while I tell you about my vacation and I grab your chin to get your attention back. Do you like it? I doubt. The child may have completely forgotten about your presence and immersed himself in self-stimulation, so that a sudden touch on the face or chin can greatly frighten him.

Don't say "Look at me!" Understand that "Look at me" is not a request for attention. Also, please , don't yell at the child "Look at me!" It's not a way to get attention. Speak in a normal tone, do not raise your voice, use pronounced facial expressions and say something like “Look here” (simultaneously pointing to the educational material).

Do not use the same reminders and prompts. I used to use visual cues to get a child's attention back at the table, especially with very young children. However, such clues can be difficult to generalize or reduce. I'm talking about signs like "Hands on knees, feet on the floor, mouth closed, ready to learn." I suggest not relying on prompts and reminders like these, because they don't teach the child to pay attention, they teach him to depend on your prompts.

I used to use visual cues to get a child's attention back at the table, especially with very young children. However, such clues can be difficult to generalize or reduce. I'm talking about signs like "Hands on knees, feet on the floor, mouth closed, ready to learn." I suggest not relying on prompts and reminders like these, because they don't teach the child to pay attention, they teach him to depend on your prompts.

Things to try

Use behavioral impulse. In a nutshell, behavioral impulse means that you allow the person to be successful, and only then present a more difficult task or requirement. So if you are having an ABA session and the child is not paying attention, then give him some simple tasks that he has already fully mastered. This way, the child will have a behavioral cycle - simple (reward) + simple (reward) - before you move on to more difficult tasks, and the child will be more attentive during them.

Be fun and emotional. The best way to attract attention, of course, depends on the individual characteristics of a particular child. However, with many clients in the past, I have fooled around to the fullest, and we started the session with countdowns, handshakes and legshakes, racing around the table, and so on. For older and more high-functioning children, a choice can be offered (“First do “Where does it fit” or “Play numbers” first?). In this way, the child will participate in the structure of the session, and you will get his attention.

The best way to attract attention, of course, depends on the individual characteristics of a particular child. However, with many clients in the past, I have fooled around to the fullest, and we started the session with countdowns, handshakes and legshakes, racing around the table, and so on. For older and more high-functioning children, a choice can be offered (“First do “Where does it fit” or “Play numbers” first?). In this way, the child will participate in the structure of the session, and you will get his attention.

Get motivated. If you have correctly identified what motivates the child, then this will certainly lead to increased attention. If I really need five dollars, and here you come to me with five dollars in your hands, then I will most likely pay great attention to what you tell me. Are you not? Always start with a systematic preference assessment to find out what motivates the child.

Helpful Hint

Attention is a complex skill and should not be assumed by default that a child has it. Perhaps the child simply does not know how and what to focus on during the lesson. In this case, you can use ABA to teach this skill. Here are a few examples of programs that can improve attention during class: imitation, receptive speech, responding to a name, following an object (the child follows the object with his eyes).

Perhaps the child simply does not know how and what to focus on during the lesson. In this case, you can use ABA to teach this skill. Here are a few examples of programs that can improve attention during class: imitation, receptive speech, responding to a name, following an object (the child follows the object with his eyes).

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

ABA Therapy and Behavior, Techniques and Treatment

How to teach a child with autism to play?

10/13/18

Speech therapist on how to teach a small child to play with different toys and other people, and how to use the game to develop speech

Source: Let’s Talk

When I tell parents that the first thing we should do is teach their child to ask for the things he wants, very often they answer me: “But he doesn’t want anything!” All children want something, and there are techniques that allow us to increase the variety and quantity of objects and activities that they desire. (This is called increasing the number of potential rewards). It seems to me extremely important that we purposefully "teach" the child to enjoy a variety of activities and games. In this case, we will have much more opportunities for learning other skills, in addition, the child will have alternative leisure activities besides “stimming”.

(This is called increasing the number of potential rewards). It seems to me extremely important that we purposefully "teach" the child to enjoy a variety of activities and games. In this case, we will have much more opportunities for learning other skills, in addition, the child will have alternative leisure activities besides “stimming”.

Why play is important

It is hard to overestimate the importance of having a small child learn to enjoy "play". While it is possible to teach a child to point to pictures as instructed, to imitate other people's actions or words in carefully structured and artificial situations, it is unlikely that a child will apply such skills in a spontaneous, functional manner and in natural situations. To do this, we must teach him how to use these skills in the "real world" (to achieve generalization of the skill). However, if the "real world" objects (toys, children's games, other people) are not interesting to the child, he will not be motivated to use these skills, and they will be retained only in an artificial situation (working at the table), when he can receive artificial encouragement (for example , candy or a cartoon for the correct answers).

For this reason, any education program for a child with autism must include one unchanging "goal" - to combine the child's already known rewards (favorite foods, smells, touches, and so on) with new objects and activities. Thus, more and more rewards for the child (conditional rewards) should be created.

In order to determine what toys and games a child might like, the easiest way is to analyze the self-stimulating behavior (“stimming”) that he has at the moment. We need to test how it will respond to various visual stimuli, sounds, tastes and movements in the environment. You may not know the answers to these questions yet. Show your child various stimuli - music, tactile sensations, flashing or bright toys and see how he reacts. When you answer these questions, you can determine which activities and toys will include sensory stimulation that is enjoyable for your child.

A very important rule for introducing a child to a new toy or activity is that you must combine it with the child's existing reward, that is, you must achieve a "combination of stimuli". In other words, your goal is to do something that the child is not particularly interested in, at the same time as doing something that the child really likes. This idea applies to any situation where you introduce a child to something new.

In other words, your goal is to do something that the child is not particularly interested in, at the same time as doing something that the child really likes. This idea applies to any situation where you introduce a child to something new.

Any incentive can be used to "combine incentives". For example, let's say that your child really likes it when you hug him very tightly. Combine a strong hug with reading a book. Does your child like to look at spinning objects? Choose toys and games that rotate. Does your child like funny sounds? Talk to him in a funny voice when you play with him. Does he like music? Sing or exaggerate the tone of your voice as you play.

After we have successfully "hooked" the child to a new game or activity (a combination of stimuli has occurred), we can teach him to ask us for a new toy or activity. We can also teach the child to ask us for various parts or parts that are needed for this game. If the child is non-verbal, then we can teach him to ask with the help of gestures or pictures. You can also pause before the last word during the game and wait for the child to “finish” for you. Such "agreement" will be partly a request to continue the lesson, and partly a more "advanced" speech response - an intraverbal reaction.

You can also pause before the last word during the game and wait for the child to “finish” for you. Such "agreement" will be partly a request to continue the lesson, and partly a more "advanced" speech response - an intraverbal reaction.

The first toys and games chosen for a child with autism are usually 'stimming' toys. For example, these are toys with rotating wheels and parts, flashing or pleasant to the touch toys. In other words, they are toys that a child can be left with and will watch or interact with in the same way over and over again. It is very important not to allow the child to "play" in this way, because self-stimulating behavior tends to reward itself.

It is important for us not to give the child unlimited access to such toys, which will only lead to an increase in self-stimulating, repetitive behavior. Instead, we are trying to combine reward (a "stimming" toy) with interaction or conversation with you. It is better to keep such toys out of the reach of the child and take them out only to play with an adult. It is very important that the instructor maintains control over the toy or parts of the toy during play so that the child does not simply "stim" and completely ignore the other person.

It is very important that the instructor maintains control over the toy or parts of the toy during play so that the child does not simply "stim" and completely ignore the other person.

If you find a toy or activity that your child is very interested in, try finding other similar toys or games that provide similar sensory stimulation to your child, or use the toy to combine with other toys and activities.

Another type of toys and play to consider are toys that combine mechanical cause and effect with imaginary play. For example, a toy car wash that sprays real water, a toy stove that blows bubbles while “cooking” or a top that plays music when spun. If your child enjoys manipulating "cause and effect" in a toy, you can control this part of the game. For example, if a child wants to look at the bubbles from the stove, but you block the button to turn it on, the child is more likely to ask for "cook"!

I very often observe the same huge mistake that is made while learning the game. The adult sits down with the child to “play” and begins to bombard him with questions. This is NOT a game, this is an exam and the child will not like it.

The adult sits down with the child to “play” and begins to bombard him with questions. This is NOT a game, this is an exam and the child will not like it.

It is generally recommended to avoid making any demands on the child during play. Just have fun and enjoy the game together. The game should be a reward for the child, even if he does not follow any of your instructions (this is called unconditional reward). For example, many children like it when adults "fool around" - they speak in a "funny" voice, exaggerate intonation, sing. In this case, accompany your actions during the game with a song or a "melodious" voice. For example, if you're helping a child jump on an exercise ball, you might say "Let's go, let's go down the flat path, over the bumps, over the bumps, hit the hole!" and help the child roll off the ball in the words "into the hole boo." If you repeat this regularly, and if the child likes this game, then you will notice that he looks at you expectantly when you come to "boom". Start pausing before that word, and it's possible your child will start saying "boo" for you! This word becomes a behavior that we can encourage, shape, and transfer to other language functions.

Start pausing before that word, and it's possible your child will start saying "boo" for you! This word becomes a behavior that we can encourage, shape, and transfer to other language functions.

Try not to tell the child what he is doing, instead try to join in his activities. For example, if a child is driving a train on rails, take another engine and try to crash or race the child's engine. If your child seems to be repeating the same action over and over again, try interrupting it in a non-intrusive way. For example, if a child is running in circles around the room, pick him up in your arms so that now he “flies” around the room.

Some children need to be around a new toy for a while before they interact with it. If this is typical for your child, then just leave the toy in the room for a few days untouched. Gradually begin to play with her yourself at a time when the child is in the room, but not next to you. Let the child see how you put the toy away where it can be seen, but where it can not be reached. Wait for the child to come to you when you are playing with the toy, and do not come to him with it. And remember: if a child ran away from a toy that he saw for the first time in his life, this does not mean that he will not adore it in the future.

Wait for the child to come to you when you are playing with the toy, and do not come to him with it. And remember: if a child ran away from a toy that he saw for the first time in his life, this does not mean that he will not adore it in the future.

Make sure that the child does not get stuck on the same action with a toy or the same story. Very often it turns out that the child is used to playing this game with mom, but he is not interested in playing with dad at all! If this tendency is typical for a child, observe what kind of behavior of another person attracts him. Perhaps it is the intonation of the voice or certain words. Although our goal is for the child to gradually overcome the need for "sameness", we can use this information to make the same toy just as interesting when playing with another person or playing in a different scenario.

Be aware that some children experience great arousal when playing with certain toys, especially if they are "stimming" toys. If the child seems to become very active and unable to focus on what you are doing, take a break and move on to another activity that includes other subjects. For example, if your child is jumping up and down and clapping his hands when playing with a top, you might want to ask him to sit down, then take a break and do something that usually calms him down. You need to be very careful - otherwise you may inadvertently reward behavior that is not entirely desirable if you react to it. Use this information, but if the “soothing” activity is more preferable for the child, proceed to it only at the moment when the child behaves in the desired way.

For example, if your child is jumping up and down and clapping his hands when playing with a top, you might want to ask him to sit down, then take a break and do something that usually calms him down. You need to be very careful - otherwise you may inadvertently reward behavior that is not entirely desirable if you react to it. Use this information, but if the “soothing” activity is more preferable for the child, proceed to it only at the moment when the child behaves in the desired way.

How to start playing

The following are techniques to increase your child's interest in other people and/or toys. Remember that in the early stages, your goal is for your child to "allow" you to join his play and for you to be part of the reward of play.

1. Warm up the anticipation. Repeat the same words and sequence of actions over and over, then begin to pause.

Example: While playing peek-a-boo, say "ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah-ah!" As the child begins to follow your actions, notice if he has begun to smile and look at you as you approach. Perhaps the child begins to laugh when you first begin to remove the blanket. If you notice that this is happening, then stop right before the “cuckoo!”. Perhaps the child will begin to say "coo-coo" or he will try to remove the blanket from you!

Perhaps the child begins to laugh when you first begin to remove the blanket. If you notice that this is happening, then stop right before the “cuckoo!”. Perhaps the child will begin to say "coo-coo" or he will try to remove the blanket from you!

2. Do something unexpected. Repeat the game in the same way, and then suddenly change the sequence.

Example: If the child is eating a cookie, say "I'm hungry!" and then pretend to take a bite of the cookie. If the child has taken it well a few times, move over and start making exaggerated noises like you're chewing something.

3. Imitate what the child is doing and then turn it into a game.

Example: A child deliberately steps on pine cones while walking. Start stepping on the bumps, saying: “Bump! Top! Then tell the child: “Your turn! Top!” when he steps on the bump himself. As the "game" develops, you may decide to arrange the cones in a circle or come up with another pattern for the "cones game". Pay attention - I'm not saying that you should repeat the stimming after the child, I suggest that you turn it into a meaningful game.

Pay attention - I'm not saying that you should repeat the stimming after the child, I suggest that you turn it into a meaningful game.

4. Interrupt your child's "play" with play obstacles.

Example: A child slides down a small indoor slide over and over again. Grab his leg (gently) when he's at the top of the slide and start pulling it from side to side, saying, “Oh no! I got you!" Pay attention to the expression on the child's face - whether he is "fun" or not. Wait until he looks at you and say “Let go?”, And then let the child slide down the slide. Or, if the child runs in circles and then jumps onto the sofa cushions, place some of the cushions on the floor and jump into them. Try jumping into the pillows one by one!

5. Associate specific words/sounds with the child's actions.

Example: When a child is coloring a picture, say “paint, paint, paint” or “up and down, up and down” (depending on what the child is doing). Use a voice (singing, quiet, or exaggerated) that the child usually likes. If you simply accompany with some words or sounds that are a reward for the child, this will increase the likelihood that the child will say these words / sounds in the future.

Use a voice (singing, quiet, or exaggerated) that the child usually likes. If you simply accompany with some words or sounds that are a reward for the child, this will increase the likelihood that the child will say these words / sounds in the future.

6. Give an old game an unexpected new meaning.

Example: If the child fills the scoop with sand over and over again and then pours it back out, pretend to eat it from the scoop! Or bring a toy of your favorite cartoon character to join the game and "feed" him.

7. Use exaggerated facial expressions and movements to get attention.

Example: Open your eyes wide and fall on the pillow shouting "boom!", open your mouth wide and pretend to wipe "tears" with your fists.

8. Give meaning to your baby's sounds. Even if you don't think the child said the "real word," listen for what those sounds are and act as if they make sense.

Example: A child draws, babbles and says something like "the sun". Say "Sun!" and draw the sun, as if a child asked him to draw.

Say "Sun!" and draw the sun, as if a child asked him to draw.

9. Add new "characters" to the game.

Example: Your child loves it when you rock him on the gym ball. Bring other toys - let them sway too. If the child starts throwing toys off the ball, comment on his actions, for example: “Go away, bear!”

Further play

All children are different, so you will need to observe your child carefully to determine when to add "requirements" to the game. As your child starts asking for toys and activities, you can gradually add in what he has to say. For example, if a child consistently asks to play with a ball, put the ball in a transparent container and prompt the child to ask you to "open" it. In the future, also teach him to say "roll" or "kick the ball" or maybe choose a ball of a certain color in your request. It is important not to increase the requirements too drastically, otherwise the child will no longer want to participate in the game. This is sometimes referred to as "kill promotion". In essence, this means that the demands have become so great that now avoiding the activity has become more motivating than the activity itself.

This is sometimes referred to as "kill promotion". In essence, this means that the demands have become so great that now avoiding the activity has become more motivating than the activity itself.

Another way to "kill a reward" is to provide so much access to it that the child gets bored with it (satiation occurs). For example, if your child really likes to play with balloons, but you play with them 10 times a day, every day, they may not be so interesting anymore! Interrupt the activity from time to time when the child still has motivation for it, but be sure to move on to the activity that is also rewarding. If you continually try new toys and games, gradually increase demands, and change activities frequently, the value of the toy or game will remain high.

Some children have very few favorite games, but they can't stand to be offered something new. If this is the case, then it is possible that the child can simply watch you play with a new toy, and in doing so, he will eat or drink what he really likes (combining with an existing reward). You will know that the child is ready to play with a new toy or a new game when he smiles at you and reaches for the toy.

You will know that the child is ready to play with a new toy or a new game when he smiles at you and reaches for the toy.

Over time, you can also expand the game by adding new "parts" to scenarios or new characters. For example, if your child likes toy animals on the train, it might be time to stop the train and take the animals to the zoo, farm, or wherever they live. Use a game that is interesting for the child and add a new part to the sequence in order to teach the child something new. Again, be careful not to add too many new requirements too quickly, otherwise the child will lose interest in the activity or simply decide to play when you are not around!

Another way to move on to more challenging play is to use your child's favorite videos. Start playing with toys the same situations as in the video. Stop the video and let the toys repeat the same situation as the one you just observed. This helps to combine toys with encouragement and also provides the child with a script to play with. Gradually change the script so that the child does not get stuck on it.

Gradually change the script so that the child does not get stuck on it.

If you teach while playing, you may be tempted to speak quickly or ask your child questions. This must be avoided at all costs. Instead, model for him how to name various items, include game-related instructions, and focus on requests.

Give your child the opportunity to decide in which direction the game will develop. For example, if a bear is “sick”, shall we take him to the doctor or to the park? If the crane cannot lift the pipe, then let the excavator help him, or shall we put it in place? Giving choices will allow your child to ask you questions while expanding the game.

Play should not be like "work"! I recommend using play to teach your child new skills and, if possible, "save" intensive learning sessions for working on speed and accuracy in multiple tasks (mixed block learning). Moreover, I believe that the first goals in teaching the child other functions of speech depend on what words the child has learned to say as requests.