How to deal with uncooperative child

8 Strategies for Dealing with a Defiant Child

When a child acts out and demonstrates defiant behavior, there’s usually an underlying reason. Maybe your child is seeking attention, testing boundaries, or frustrated about school or her social life. Taking the time to understand why your child is acting out is often a big part of finding the solution.

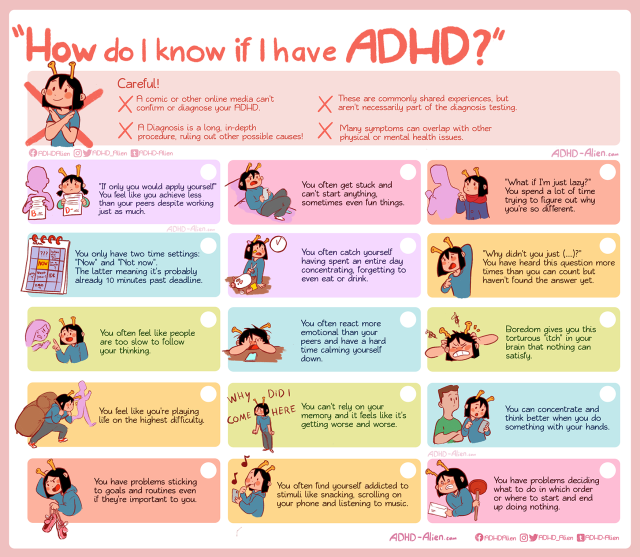

Could you be dealing with oppositional defiant disorder?

First, make sure your child’s behavior isn’t an ongoing pattern. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) isn’t just a buzzword, it’s something very real that 1 to 16 percent of children and their parents struggle with. Here’s how the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry defines ODD.

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is one of a group of behavioral disorders called disruptive behavior disorders (DBD). These disorders are called this because children who have these disorders tend to disrupt those around them. ODD is one of the more common mental health disorders found in children and adolescents.

![]()

Physicians define ODD as a pattern of disobedient, hostile, and defiant behavior directed toward authority figures. Children and adolescents with ODD often rebel, are stubborn, argue with adults, and refuse to obey. They have angry outbursts and have a hard time controlling their temper.

ODD: A Guide for Families, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

A child with oppositional defiant disorder:

- Has frequent temper tantrums

- Argues constantly with adults

- Refuses to do what is asked of an adult

- Always questions rules and refuses to follow rules

- Does things to annoy or upset others, including adults

- Blames others for his/her own misbehaviors or mistakes

- Is easily annoyed by others

- Often displays an angry attitude

- Speaks harshly or unkindly

- Seeks revenge or acts vindictively

Any child can act out from time to time, but children with ODD show a constant pattern of hostility and defiance, usually aimed at people in authority like parents or teachers. Their behavior interferes with learning and school activities.

Their behavior interferes with learning and school activities.

If you suspect your child may have ODD, seek guidance from your child’s doctor or a mental health professional.

How to parent a defiant child

If your child is like most kids and has occasional periods of defiance, there are things you can do to make things easier. I discovered eight strategies that helped me with my own brood. By following these techniques, you too can survive your child’s maddening moments.

1. Make your expectations clear

Children of all ages need to know the family rules for things like helping out with chores, completing homework, bedtime and curfews, and acceptable behavior toward others. The time to discuss these matters is when things are going well, not after an incident has occurred.

Sit down with your kids and let them know what types of behaviors you will not tolerate. List examples of unacceptable behaviors such as treating others with disrespect, refusing to do chores or homework, mistreating possessions, or physical aggression like hitting or biting.

The goal is not to prevent your child from ever breaking the rules but to teach him that when rules are broken, consequences follow.

You can’t expect your child to be compliant if he doesn’t know your expectations. The goal is not to prevent your child from ever breaking the rules but to teach him—preferably from a young age—that when rules are broken, consequences follow.

In my family, we took the time to write our rules and their respective consequences on a poster board which we have framed and hanging in our home. This way, there’s never a question as to our expectations.

2. Choose your battles

Parenting is exhausting enough when things are going well, but when one of your children is purposefully misbehaving, the difficulties are multiplied. So choose how you spend your energy wisely!

Let’s say your high schooler wants to wear pants that are too big because that’s the style. Do you really want to start the day off on a negative note by hassling him over his fashion choices? On the other hand, if he tells you he isn’t going to school because he doesn’t feel like it, that’s just not going to fly. Save your mental energy, not to mention your child’s, for more serious issues.

Save your mental energy, not to mention your child’s, for more serious issues.

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned in my 18 years of parenting is that you can’t change your child’s attitude unless you change your own first. Which brings us to strategy number three.

[block:qdt=insticator]

3. Act, don’t react

When you witness defiant behavior from your child, don’t get angry and lose your temper. Instead, take a step back and tell your child that you don’t approve of the behavior and she needs to stop. Tell her you’ll talk about consequences at a later time when you can both talk calmly.

This will give your child time to think about her actions and the potential consequences. Not only are you using the time to calm yourself down, but you’re also teaching her to do the same.

4. Enforce consequences

Effective consequences can largely be grouped into two categories: removals and impositions.

A removal is taking something away from the child, such as your attention, an exciting environment, or a pleasant activity. The most well-known and widely-used removal is a time out. Other effective removals include grounding your child from social activities, taking away electronics for a certain period of time, or immediately leaving the park, a friend’s house, or a family party when a defiant behavior occurs.

The most well-known and widely-used removal is a time out. Other effective removals include grounding your child from social activities, taking away electronics for a certain period of time, or immediately leaving the park, a friend’s house, or a family party when a defiant behavior occurs.

Impositions are consequences that impose a new situation on the child. Paying his own money into a family fine jar, doing extra chores, having to run errands with mom because he abused the privilege to stay home alone by inviting friends over without permission—these are impositions.

Without question, consequences require time and energy to enforce. But if you don’t follow through with consequences for bad behavior, you send the message “If you wear me down, eventually, you’ll get your way.”

5. Keep your power

When you engage in an argument with your child, you’re enforcing the child’s perception that they have the power to challenge you, which can lead to even more defiant behavior.

The next time your child tries to draw you into a power struggle over something, just say, “We’ve discussed this and I’ve told you what’s going to happen. We’re not going to talk about it anymore,” and leave the room.

When you leave, you take all the power with you. Know that the more you engage your child in an argument, the more control you give away.

6. No second chances or bargaining

Consistency is key if you don’t want to reinforce bad habits. Once your child is old enough to understand that behaviors have consequences, don’t give him repeat chances. This just teaches him that you don’t take your own rules seriously.

Don’t bargain or offer treats or privileges in return for better behavior. You’re only enabling your child to test how far they can push you.

If your son calls his friend a rude name when you arrive for a play date, firmly say “We don’t talk like that. We’re going home now so you can spend some time thinking about what you said.” Insist that he apologize, and then leave immediately. No ifs, ands, or buts.

No ifs, ands, or buts.

Don’t bargain or offer treats or privileges in return for better behavior. You’re only enabling your child to test how far they can push you before you strike another bargain.

7. Always build on the positive

Make sure you build on the positive attitudes and actions of your children. Praise your children for their positive behaviors, like rewarding them when they show a cooperative attitude. Positive reinforcement can go a long way in raising a responsible child.

By making a simple switch to rewarding good behavior instead of reacting to bad, parents will see a significant reduction in challenging behavior.

For more about building on the positive and rewarding good behavior, listen to my interview with Dr. Heather Maguire, a behavior analyst and school psychologist. (It’s episode 569, What to Do When Your Child Won’t Behave.) She advocated for rewarding good behavior by catching your child doing good. By making a simple switch to rewarding good behavior instead of reacting to bad, she said, parents will see a significant reduction in challenging behavior.

8. Set regular times to talk to your child

In a moment of downtime, when things are going well and you don’t anticipate an immediate power struggle, sit down with your child. Let her know that your intentions are to keep her safe and help her grow into a responsible, productive, self-reliant adult who will be as happy and fulfilled in life as possible. Remind her that your family has rules and values that are in place for her future, not to cause her grief while growing up.

Dealing Effectively with Defiant Young Children and Toddlers

Do you ever find yourself wondering, “When will this child stop defying me and start doing what I ask?”

“I won’t do it!”…“You can’t make me!”…“I’m not going!”

It can be incredibly frustrating, not to mention exhausting, dealing with a young child or toddler who finds it necessary to challenge your every request, act in a defiant manner, lose their temper, and be generally disruptive or annoying.

Parents oftentimes find themselves drained as they come up against this behavior, and wind up feeling hopeless about how to handle the situation. They might also start worrying about what the future holds for such a strong-willed child. The good news is there is help in dealing with defiance in young kids—and the solutions are easier than you may think.

If your child can’t calm himself, setting limits for him to work through his rage can help. The point is to not jump on the crazy train with him.

Why Is My Child So Difficult?

Many parents want to know why their toddler or young child is so difficult.

“Why can’t my child be more like my niece who’s so pleasant and calm?”

“Why does my son have to be the one who is always saying no and acting so angry?”

It’s normal to want an answer to why your child is the one who’s always acting out and hard to manage, and there may be concrete reasons for his behavior.

No Control

It’s important to take into account that young children have very little control in their day-to-day lives. If you think about it, most kids float through their days with most decisions already made for them: when they wake, when and what they eat, what they will wear, when they will do chores or play, and finally, what time they go to bed each evening.

For many kids this isn’t a problem; they ride the wave of parental control without incident, some even enjoying having decisions made for them. Other kids, especially those who have strong personalities and definite opinions, find this level of “control” confining and annoying. What better way for a young child to express his displeasure than to habitually refuse to listen or to be argumentative?

Communication Skills and Temperament

Young kids and toddlers have a limited vocabulary and become frustrated when they can’t articulate what they want or how they’re feeling. They’re learning how to communicate with parents and teachers, so it makes sense that anger, defiance and irritability may be the only route they know to take when feeling overwhelmed and out of control. Another reason for a child’s defiance can simply stem from the strong personality they were born with. All of us can probably identify at least one strong-willed person (maybe even ourselves?) in our family tree.

Another reason for a child’s defiance can simply stem from the strong personality they were born with. All of us can probably identify at least one strong-willed person (maybe even ourselves?) in our family tree.

Is It ODD?

When looking at your young child, it’s important to understand that for some, this period of defiance is just a phase that they will pass through as they mature. Other kids may meet the criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), which is a persistent and frequent form of defiant behavior.

Examples of ODD include any time a child has a pattern of being angry and irritable, argumentative or defiant along with displays of vindictive behavior. These characteristics can show up in a child who easily loses their temper, is unusually touchy or annoyed, and is often angry and resentful of those around him.

In addition, the child with ODD will argue with authority figures, refuses to comply with rules or requests and will annoy others on purpose, all the while blaming others for his behavior.

When you read this description, you may be thinking, “My child does all of that!” In fact, you’d be correct in noting that all children at some point or another probably engage in these kinds of behaviors. The key here, though, is whether or not your child has a pattern of displaying such behavior on a regular basis towards those around her, as opposed to occasionally refusing to do chores, teasing her younger brother sometimes, or being angry at you in the moment for getting called out for bad behavior.

While a child with Oppositional Defiant Disorder does act out on a more regular basis, as opposed to a child with simply a difficult temperament, parents should generally take the same approach to handling the behavior.

Below are 5 things not to do when dealing with a defiant or “difficult” child.

1. Don’t lose your cool

The most crucial first step you can take when dealing with a defiant young child is to not lose your cool. I know this is easier said than done, and can be incredibly challenging for any parent who’s going up against a screaming, uncooperative child! But the primary point to keep in mind when this happens is this: You are the adult and you are modeling how to act appropriately in a difficult situation for your young child. Defiant kids often lack resources for knowing what to do next and are looking to you for guidance. There can be a number of reasons why your child is acting out, some that you (or even your child) may never be able to fully understand, but the bottom line is that in that moment of rage, they don’t know what to do. This teachable moment can allow your child to truly learn how to respond when experiencing a full-blown emotional crisis. Some useful responses for your young child might be:

Defiant kids often lack resources for knowing what to do next and are looking to you for guidance. There can be a number of reasons why your child is acting out, some that you (or even your child) may never be able to fully understand, but the bottom line is that in that moment of rage, they don’t know what to do. This teachable moment can allow your child to truly learn how to respond when experiencing a full-blown emotional crisis. Some useful responses for your young child might be:

“We don’t yell. Please stop.”

“You can’t talk to me like that. Stop now or you will need to sit by yourself.” (If your child is old enough and it’s appropriate for them to sit alone.)

This can also be a good time to teach your child some calming techniques that can help them regain control. Showing a young child how to stop, count, and breathe involves explaining to your child when she is calm how to stop herself in her tracks by physically sitting down, closing her eyes and slowly breathing in and out, all the while counting to ten, however many times it takes for the crisis to pass. Practicing this regularly with your child can allow her to have a tool ready when the crisis hits. Note however, that for some kids this will not work, in which case you will need to move to the next step.

Practicing this regularly with your child can allow her to have a tool ready when the crisis hits. Note however, that for some kids this will not work, in which case you will need to move to the next step.

2. Don’t go down the well

There’s a reason why the saying “Misery loves company” makes sense. Many times when children are defiant, they want everyone around them to experience their pain as well. The important thing is to not let them pull you into their momentary misery. For some kids, upping the ante and getting everyone in the family involved in their personal drama is extremely satisfying for them and serves to reinforce future outbursts.

If your child can’t calm himself, setting limits for him to work through his rage can help. The point is to not jump on the crazy train with him. Secure a safe spot for him to go when outbursts occur and guide him there. If your child is old enough and you think it’s safe to do so, you can walk into another room and give him or her some time to calm down. Some things to say include:

Some things to say include:

“I understand you’re upset. Can you calm down so we can talk?”

“Since you won’t stop yelling I’m leaving the room until you calm down.” (If your child is old enough and it’s appropriate for you to leave the room.)

“When you’re ready we’ll talk, but not until you get ahold of yourself.”

3. Don’t take the focus off responsibility

Since defiant kids often have a hard time taking responsibility for their actions, it’s important to tell them your expectations (“We don’t hit our sister”) and provide consequences for them upfront. Try to consistently reinforce them, all the while pointing out that they are ultimately in charge of their behavior. In the moment when the behavior is happening, you can let him know there will be a consequence of some kind. Then, after things have calmed down, you can follow up and implement an appropriate one. (“Since you hit your sister, there will be no TV tonight.”)

By consistently not letting your child off the hook, he knows you mean business, that you care enough to hold him accountable, and that there are boundaries in your home that shouldn’t be crossed. Even though your child may rage and yell in the moment, ultimately this provides him with a sense of security. This may not necessarily stop his defiance at this point in his development, but it will prevent it from growing into a more severe problem as he gets older.

Even though your child may rage and yell in the moment, ultimately this provides him with a sense of security. This may not necessarily stop his defiance at this point in his development, but it will prevent it from growing into a more severe problem as he gets older.

4. Don’t Flash Forward

Too often when a child has a difficult temperament or a full blown Oppositional Defiant Disorder, parents fast forward to the worst case scenario possible, imagining all sorts of gloomy forecasts for their child’s future. This is easy to do when your child rarely seems happy, is often irritable, and has unrelenting behavior. As hard as it is though, try to be mindful of the here and now and what your child needs from you in this moment. When you find yourself worrying that your child is going to end up unemployed and living under a bridge because he talks back so much and won’t take no for an answer, try to ground yourself and move on to the next step.

5. Don’t forget to pay attention to the good things about your child

Parenting a defiant child is likely one of the most difficult tasks any parent will face. It’s hard, it’s tiring, and it can be depressing at times, which is why it’s so important to remember to find things about them that are loveable, kind, and sweet, even if it may seem like a stretch on some days. Accepting one’s child doesn’t mean excusing bad behavior, but rather acknowledging that they experience the world differently than many of us. Too often parents become so entangled with the daily struggles of parenting a child who behaves like this that the goodness that exists within them (and it’s in there, even if you have to dig deep) gets lost. Actively search out examples on a daily or weekly basis that confirm not the worst in your child, but the best. These can be instances when your son was kind to his sister for one full day, or your daughter said “thank you” instead of giving you a rude answer. It can come in the form of them putting away their dishes on their own or not arguing with you or blaming others. Point out to your child that you noticed by saying, “I like how nicely you answered me.

It’s hard, it’s tiring, and it can be depressing at times, which is why it’s so important to remember to find things about them that are loveable, kind, and sweet, even if it may seem like a stretch on some days. Accepting one’s child doesn’t mean excusing bad behavior, but rather acknowledging that they experience the world differently than many of us. Too often parents become so entangled with the daily struggles of parenting a child who behaves like this that the goodness that exists within them (and it’s in there, even if you have to dig deep) gets lost. Actively search out examples on a daily or weekly basis that confirm not the worst in your child, but the best. These can be instances when your son was kind to his sister for one full day, or your daughter said “thank you” instead of giving you a rude answer. It can come in the form of them putting away their dishes on their own or not arguing with you or blaming others. Point out to your child that you noticed by saying, “I like how nicely you answered me. Thank you.” Or “Thank you for not losing your temper just now.” Remember, it’s the behavior that you may not like, not your child him or herself.

Thank you.” Or “Thank you for not losing your temper just now.” Remember, it’s the behavior that you may not like, not your child him or herself.

A final point to keep in mind is that children with these personality traits may not be the easiest to live with while they are at home, but it is exactly these types of kids who can grow up and change the world. Everyone agrees that a calm, sweet child is easy to raise, but those traits, while admirable, may not be the ones that stop injustice, forge new ways of thinking, or uncover the unfairness and inequity of the world we live in. Often it’s the very qualities in our children that make us crazy—the stubbornness, the defiance, the anger—that are not only useful, but are necessary for a person who wants to make society a better place. That idea of not giving up, so annoying now, can propel our children to greatness as adults. When we look throughout history at who has changed the world, it has rarely been the meek or the quiet, but rather those who charged through difficulties, wouldn’t take no for an answer, and sometimes had to get angry to bring about change. When you combine firm, loving, consistent boundaries together to form a parenting style in which to deal with your defiant young child, you are laying the groundwork towards helping them take responsibility for their temperament while also honoring who they are as a person. This gives you both the opportunity to be the best that you can be, now and in the future.

When you combine firm, loving, consistent boundaries together to form a parenting style in which to deal with your defiant young child, you are laying the groundwork towards helping them take responsibility for their temperament while also honoring who they are as a person. This gives you both the opportunity to be the best that you can be, now and in the future.

Related content:

How to Discipline Young Kids Effectively: 4 Steps Every Parent Can Take

Young Kids with ODD: Is It Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Just Bratty Behavior?

Subscribe to the Empowering Parents Podcast via Stitcher

Subscribe to the Empowering Parents Podcast via iTunes

How to behave with children? Psychologist's advice

When disturbing, frightening events occur or a situation of uncertainty arises, parents are often worried about questions: how to behave with a child correctly, how to tell him about what is happening and whether to tell him at all what should alert the child's behavior, and what, on the contrary, is normal.

In child psychology, it is customary to distinguish several age periods. Consider the features of interaction with children of preschool (3-7 years old) and primary school (7-11 years old) ages.

A few recommendations:

The greatest influence on the child is not even the situation itself, but the reaction to it of close adults who surround him. For a preschooler, such adults will be parents and those adult family members with whom communication takes place every day; For the younger student, the teacher also plays a significant role:

- Children are very sensitive to the emotional state of close, significant adults. When an adult is upset, anxious, scared, the child also experiences these emotions. If the child does not know the reason, then helplessness is added to fear and anxiety. Therefore, when you see a child's need to talk, do not ignore it.

Example: You are upset and need some time to recover. The child feels this and insistently asks the question “What happened?”

The child feels this and insistently asks the question “What happened?”

Wrong answer: "Nothing happened, go play (draw, do your homework)"

The correct answer is: “I’m a little upset (alarmed, sad) right now, because ..., let’s draw a robot now (do your math homework), and then we’ll go for a walk (we’ll have dinner).”

- When talking to your child, use simple, child-friendly phrases and expressions.

- Ask about the child's point of view. This will help to understand what worries, scares or worries him, and you can provide the necessary psychological support.

- Try not to contradict the positions of the adults. Putting a child in a situation of choice, you place an unbearable burden on him.

- Children very quickly adapt to the situation, BUT! Only on condition that the behavior of adults gives them such an opportunity.

Pay attention to information hygiene:

- Pay attention to what you watch or talk about with your family, friends, acquaintances.

Try not to see or hear what is not intended for him: emotional disputes with colorful examples, news releases with frightening details. Sometimes there is a feeling that the child does not pay attention to what is happening - this is an illusion! Based on the information obtained in this way, children often draw their own conclusions about what is happening, which are often the cause of children's fears.

Try not to see or hear what is not intended for him: emotional disputes with colorful examples, news releases with frightening details. Sometimes there is a feeling that the child does not pay attention to what is happening - this is an illusion! Based on the information obtained in this way, children often draw their own conclusions about what is happening, which are often the cause of children's fears. - At primary school age, the information field of the child expands, it includes school friends, classmates, many at this age master communication on the Internet. Show interest in this area, ask about his friends and hobbies. A trusting relationship will help you spot trouble or danger.

- Talk to children about topics that concern them, do not limit yourself to the phrases “everything will be fine”, “this is an adult topic, you won’t understand”, etc. If adults do not give an answer to a question of interest to the child, he will find the answer in another source, which may be unreliable and even dangerous.

Pay attention to the behavior and mode of life of the child:

- Adults experience difficult moments, realizing, thinking over and discussing what is happening. Children have other ways. It is easier for a preschooler to cope with what is happening by playing or drawing it. Therefore, stories that frighten a child can be found in a game or drawings. For younger students, it is important to study, master new knowledge, so often children of this age try to learn more about what excites, frightens or disturbs. Do not prohibit children from these activities and do not blame them. The best strategy is discussion and cooperation. And if the behavior of the child is alarming, consult a child psychologist for advice.

- Organize your child's life by keeping the usual routine of the day as much as possible. The usual course of life, everyday affairs, the presence of a plan for the next day, week, month allow you to overcome the feeling of helplessness and anxiety, allow you to feel confident.

Do not neglect sports, communication, hobbies yourself and do not deprive this child. If something from the previous possibilities turned out to be unavailable, try to find a replacement. These activities allow you to replenish the resources and energy spent on experiences.

Seek professional help if necessary. You may need to consult a child psychologist if:

- The child's behavior has changed dramatically, these changes are persistent - they last several weeks or longer.

- The child has lost interest in things that were previously important to him: play, study, sports.

- Significantly changed the nature of communication with others: he became withdrawn, stopped communicating with friends, refuses to go to school or kindergarten.

- Symptoms such as stuttering, nightmares and difficulty falling asleep, intense fear appeared.

You feel the need for psychological help, even if there are no signs listed above.

We remind you that the Ministry of Education has organized a round-the-clock hotline for psychological assistance for children and parents based on the resource center of the Moscow State University of Psychology and Education. Help for children will be provided by phone: 8-495-624-60-01, adults - by the number 8-800-600-31-14.

Children behave well if they can

Ross W. Green “Explosive Child. A new approach to understanding and educating easily irritable, chronically intractable children "

The book is addressed to parents of children who have adaptation problems and often demonstrate unacceptable behavior that is difficult for others to cope with.

There are many worldly names for such children: "difficult", "behaving provocatively", "stubborn", "manipulating", "selfish", "acting out of spite", "wayward", "unyielding", "unmotivated". They are united by a number of distinctive properties, which primarily include extreme non-adaptation and the almost complete lack of self-control in a situation of emotional stress. Even simple changes in the environment and the requests of others can cause them to have an acute intense reaction, physical and verbal aggression, they can withdraw into themselves and begin to avoid communication with others due to problems with flexibility and emotional self-control. They may have many virtues, but their lack of adaptability and emotional self-control skills overshadows their positive qualities. It is incredibly difficult for such children to think rationally in a situation of emotional stress. Outside observers, as a rule, make comments to parents that such behavior is the result of improper upbringing. Traditional explanations for children's temper and disobedience are: "he does it to get attention", "he just wants to get his way" or "when he needs to, he can behave perfectly."

Even simple changes in the environment and the requests of others can cause them to have an acute intense reaction, physical and verbal aggression, they can withdraw into themselves and begin to avoid communication with others due to problems with flexibility and emotional self-control. They may have many virtues, but their lack of adaptability and emotional self-control skills overshadows their positive qualities. It is incredibly difficult for such children to think rationally in a situation of emotional stress. Outside observers, as a rule, make comments to parents that such behavior is the result of improper upbringing. Traditional explanations for children's temper and disobedience are: "he does it to get attention", "he just wants to get his way" or "when he needs to, he can behave perfectly."

Effective correction strategies flow naturally from understanding the causes of a child's peculiar behavior. In some cases, understanding the motives for such behavior itself leads to improved relations between children and adults, even without the use of special strategies.

For parents, there is nothing more amazing and entertaining than watching their child master new skills and cope with increasingly complex problems on his own every month and year. No less surprising is the unevenness with which different skills develop in different children. Some people find it easy to read, but have problems with math. There are children who excel in all sports, while for others, any sporting achievement is given with noticeable effort. In some cases, the backlog is due to a lack of practice. But often difficulties in mastering a certain skill arise, despite the desire of the child himself to achieve a positive result, even after appropriate explanations and training.

It's not that children don't want to learn a particular skill, they just don't learn it at the rate they expect. If a child's skills in some area are far behind the expected level of development, we try to help him. Some children start reading late, others never achieve outstanding sports results.

And there are children who lag behind in the field of adaptability and self-control. Mastering these skills is extremely important for the overall development of the child, since a harmonious existence is unthinkable without the ability to resolve emerging problems and settle disagreements with others, as well as control oneself in a situation of emotional stress. In fact, it is difficult to imagine a situation that would not require flexibility, adaptability and self-control from the child. It is important to understand that such children do not consciously choose to be short-tempered as a behavior, in the same way that children do not consciously choose a reduced ability to read: such children simply lag behind the norm in developing skills of adaptability and self-control. There is a huge difference between viewing temper tantrums as the result of developmental delays and blaming a child for intentional, conscious, and purposeful misbehavior. And the explanation of the reasons for the child's behavior, in turn, is inextricably linked with the methods by which you are trying to change this behavior. In other words, your parenting strategy is determined by the explanation you choose. If you consider a child's behavior to be intentional, conscious, and purposeful, then labels such as ("stubborn", "argumentative", "little dictator", "extortionist", "hungry for attention", "nonsensical", "manipulator", "brawler" ”, “lost the chain”, etc.) will seem quite reasonable to you, and the use of popular strategies that force obedience and tell the child “who is in charge in the house” will become an acceptable way to solve the problem.

In other words, your parenting strategy is determined by the explanation you choose. If you consider a child's behavior to be intentional, conscious, and purposeful, then labels such as ("stubborn", "argumentative", "little dictator", "extortionist", "hungry for attention", "nonsensical", "manipulator", "brawler" ”, “lost the chain”, etc.) will seem quite reasonable to you, and the use of popular strategies that force obedience and tell the child “who is in charge in the house” will become an acceptable way to solve the problem.

In other words, if your child could behave well, he would behave well. If he could take the restrictions imposed by adults and the demands of others calmly, he would do so. You already know why he can't: because of developmental delays in adaptability and self-control.

An outburst (an outburst of irritation), like any other form of maladaptive behavior, occurs when the demands placed on a person exceed his ability to adequately respond to them.

According to the author, the types of internal stabilizers, i.e. there are not so many certain mental skills, the absence of which leads the child to an explosive outbreak, these are:

• skills of conscious self-management,

• Speech skills,

• Emotion control skills,

• Intellectual Flexibility Skills

• social skills.

And here's what's interesting: first, since these are skills, they can and should be developed, second, there are no concepts in the list: "not strict enough parents" and "lack of education." If you understand exactly what skills your child lacks, you will not explain his behavior as unmotivated, selfish or dictated by the desire to manipulate, you know what he needs to be taught.

Pins:

1. Adaptability and self-control are important developmental skills that some children do not develop at the level appropriate for their age. A delay in the development of these skills leads to various deviations in behavior: sudden manifestations of irascibility, tantrums, physical and verbal aggression, which often become a reaction to the most innocent set of circumstances and have a traumatic, negative impact on the relationship of such children with parents, teachers, brothers, sisters.