How to cook julia child

Julie Powell: What I Learned From Cooking Julia Child's Recipes For a Year

Julie Powell contemplates her next project in New York, May 16, 2004.Photograph by Julien Jourdes

culture

Everything Julie Powell learned from cooking through Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

By Julie Powell

Illustration by Pornchai Mittongtare

Editor's note: On October 26 writer Julie Powell died at her home in Olivebridge, in upstate New York. She was 49. Powell was famous for the Julie/Julia Project, for which she spent a year cooking from Julia Child's cookbook, ‘Mastering the Art of French Cooking.’ In Bon Appétit’s December 2003 issue, Powell wrote “Julia Knows Best,” an essay about her experience. Read it below.

Mastering the Art of French Cooking has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. Not the food, you understand, just the book itself. It resided in my mother's rack of cookbooks, an eccentric aunt to the spiral-bound Junior League collections that surrounded it, its cover spangled with an old-world pattern of rose-colored fleurs-de-lys, its pages dotted with French words and occasional line drawings depicting culinary acts beyond comprehension.

Later, when I graduated from college and headed out to New York, I brought it with me. But I didn't cook out of it. Instead, I just caressed its cover and skimmed over its pages, savoring the unlikely recipes —Oeufs à la Bourguignonne, Poulet en Cocotte Bonne Femme—when I needed the inspiration to attempt a complete Thanksgiving dinner in a basement studio apartment. The book was a talisman, not a tool.

That is, until the psychotic break that came to be known as The Julie/Julia Project occurred. One day when it all got to be too much—the job, the commute, the whole turning-30 thing—I abruptly chose to immerse myself in the pages of Julia Child's 1961 classic. The plan was this: Cook every recipe in Mastering the Art of French Cooking. All of them. And do it in one year.

Only it wasn't so much a plan, per se. More like a revelation. Or a panic attack. No matter. In the 60s, Julia had taught an America up to its ears in ambrosia salad how to cook—and eat—well. Now she could teach me.

And so she did. After one year and 524 recipes, here's what I've learned.

Begin at the Beginning

If you are going to master the art of French cooking with Julia Child, you are going to start with Potage Parmentier—potato and leek soup.

It is, in Julia's words, "simplicity itself to make," just sliced potatoes and leeks simmered in water for close to an hour, then mashed with a fork, seasoned with salt and pepper, and enriched with cream or butter. You may be tempted to skip it—you know all about potato and leek soup, after all.

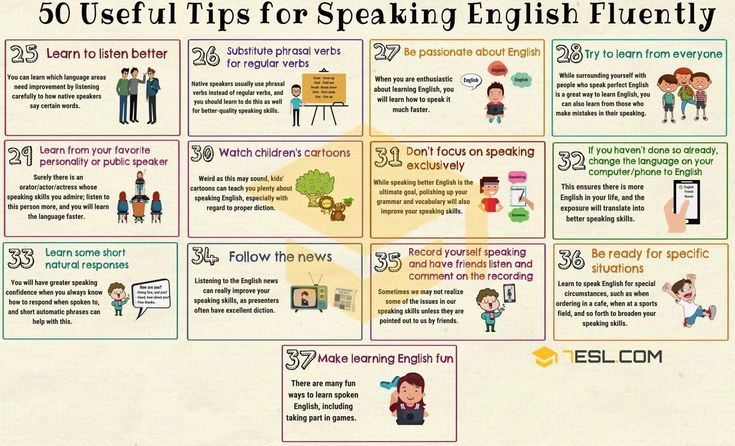

Don't. The whole structure of MtAoFC starts with the idea that in order to learn well, you start with basic techniques and build on them. Julia's not suggesting you don't know how to make potato and leek soup; she just wants you to begin at the beginning. Have you ever started learning a foreign language and gotten really cocky at the first class —Parlez-vous français? Duh!—only to find yourself drowning in conjugations three weeks later? This is the same. Pay attention, or by the time you get to bouillabaisse you'll be in real trouble.

Try New Things

Okay, here's a confession: I had never eaten an egg before I embarked on The Julie/Julia Project. Well, only ones that were baked in a cake, or at the very least scrambled with cheese and peppers and tortilla chips and anything else I could think of that would keep them from tasting like, smelling like, or in any way resembling eggs.

But MtAoFC has a whole chapter on eggs, starting with poached eggs. The thought of them made my gorge rise, but I had started this crazy thing, and now I had to finish it, so poach eggs I did.

I did it the hard way, too, without those reptilian-looking poaching cups—I just slipped the eggs into the simmering water and gently urged the whites over the yolks with a spoon. And after going through two dozen eggs and three poached-egg recipes (including one in which I had to poach them in red wine, which not only was really hard but also turned the finished eggs a disturbingly cadaverous blue), I could make poached eggs that were...well, not perfect. But they held together, and they were runny inside, and they fit on the round toasts Julia had me serve them on, covered with cheese sauce, and into the pastry cups, with mushrooms and a tomato béarnaise.

I could make poached eggs. Better yet, though, I could eat them, even like them. Because poached eggs, it turns out, taste like cheese sauce. Mirabile dictu!

Practice, Practice, Practice

I'd never been much of a quiche person. I grew up in Texas, after all, where the saying "real men don't eat quiche" is not gender-specific. But MtAoFC contains nine recipes for quiche, so quiches I made: Quiche Lorraine and Quiche aux Oignons, quiches with tomatoes and olives and anchovies and leeks. By the end of the quiches I could whip the stuff up in seconds, and my crusts turned out buttery and golden and flaky and perfect.

I finished with the quiches long ago, and now, separated by more than half a year and a gulf of aspic and leg of lamb, I remember them as if from a dream. I think I miss Quiche au Roquefort the most. Such a clean, simple, rich combination of flavors—the sharp Roquefort mellowed in the eggs and cream, the delicate snap of the pastry crust. That is the taste of French food to me now.

Taste Everything

I have had my fair share of cooking disasters. The quail in rose petal sauce that I made with a bunch of roses I bought at the 7-Eleven comes to mind.

But Oeufs en Gelée was the worst. I made the jelly by boiling cow's hooves and pigskin, which made my house smell like a tannery. I poured the jelly over some poached eggs in little molds and let them set. When I unmolded them, they were brownish, quivering cylinders, the little x of tarragon leaves I'd used to decorate them somehow macabre, like a mark on the door of a plague-ridden house.

I tasted it. It was a horrible mess. But it was my horrible mess. And now I never have to do it again.

Death Is a Part of Life

I think a strong argument can be made that any meat-eating person ought to take the responsibility once in life for slaughtering an animal for food. But I speak from experience when I say that it's probably not necessary to chop the animal into small pieces while it's still alive.

In the recipe for Homard à l'Américaine, Julia instructed me to "split the lobsters in two lengthwise." Sounds simple enough, doesn't it? Many people insist that plunging a knife through a lobster's head is absolutely the quickest and most humane way to kill it. I have to say, though, that the lobster I murdered in this way did not seem to think so. It did not think being sawed in half vertically was much fun, either. Even after I'd chopped the thing into six pieces, the claws managed to make a few final complaints about the discomforts of being sautéed in hot olive oil.

But when I had completed my Homard à l'Américaine, I ate it. And, raising a glass, I took a moment to remember all the chickens and cows that have died for me, if not at my hands.

Live. And Learn.

It is a mysterious fact that I had never once in my entire life watched a Julia Child cooking show before the inception of the project. To me, Julia Child was always the book, plus Dan Aykroyd blithely gushing blood on Saturday Night Live.

So watching my first episode a few months ago was illuminating. I had just had a kitchen meltdown, complete with hurled cutlery and the beating of skulls on door frames. (These incidents occur, it must be said, not infrequently. )

My husband, fearing I might do myself an injury, sat me down in front of the television—and who should be on PBS but Julia herself! It was, truly, a miraculous event, a manifestation in my living room of the Patron Saint of Servantless American Cooks. The show was an old episode of Cooking with Master Chefs and Julia was being taught, by a French person I didn't recognize, how to temper chocolate.

I had come to think of Julia as my mentor, but as I sat there, the tears still drying on my face, clutching a food mill clotted with fish, and watched her warbling away, I realized that she is also an exemplary and inspirational student. There she was, 80 if she was a day, sticking her fingers into the chocolate, leaning over on her big, curled paws to watch the proceedings, and asking, asking, asking. She was teaching me again —this time, how to learn —with grace, generosity, wit, and endless enjoyment.

Sometimes —for instance, when I contemplate making Pâté de Canard en Croûte, which involves boning a whole duck and stuffing it with homemade pâté, then baking it in a pastry crust—I despair.

But then I picture Julia, sipping a glass of wine and biting into a gorgeous piece of the chocolate she just learned to temper, crying "Bon Appeteeeee!" with the relish of a deranged schoolgirl, and I remember. I am learning—to cook, yes, but also to live, like Julia.

Explore Bon AppétitCulture

Read MoreJulia Child's 14 Best Cooking Tips For Home Chefs

George Rose/Getty Images

By Adrienne Katz Kennedy/Updated: Dec. 15, 2022 1:53 pm EST

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Much has been written about the legendary chef and TV icon Julia Child. She is credited for bringing traditional French cuisine into the homes and hearts of Americans by showcasing techniques in a simple and accessible way.

More than just a good teacher, Child was known for her sense of humor, her authentic and imperfect delivery, and her relentless drive to break down barriers and uplift the value of women in the kitchen. Her refusal to quit culinary school despite being the only woman admitted to Le Cordon Bleu in France, in 1949, is proof of said drive and stubborn determination (via Showbiz CheatSheet).

In an era that touted the perfect happy housewife as the standard for all women, Child added a sense of depth, fallibility, humanity, and bravery in the kitchen, as well as timeless advice. Here are some of Julia Child's best tips and nuggets of wisdom, applicable to home (and professional) cooks everywhere.

Don't overcrowd your pan

Zichrini/Shutterstock

So much of cooking revolves around patience. Paradoxically, of course, we often come into the kitchen already driven by feelings of hunger and the desire to alleviate them quickly. We want to make as much as we can as quickly as possible.

When it comes to pan cooking, however, sautéing or frying in small batches to avoid overcrowding will work in your favor to save you time and produce a delicious result. In fact, this was Julia Child's secret to achieving the best crispy-edged sautéed mushrooms. Ingredients that are water-rich, like mushrooms, will release their moisture when heated. In order to avoid steaming them — which is a different technique altogether — heed Julia's advice and spread them out in the pan to avoid using the water during their time in the pan.

Julia even suggests using as little water as possible, perhaps even just rubbing the mushrooms and trimming the stems to help remove dirt, to prevent further water absorption, which will only increase the need to really spread them out when they hit the pan (via Julia Child on PBS).

Sautée with oil and butter to prevent burning

Cheche22/Getty Images

Let this list inspire you to re-watch Julia Child in the kitchen, in search of all the nuggets of wisdom tucked into every show she filmed. As we know, Julia was perhaps butter's biggest fan, using well over 700 pounds of it during her series "Baking with Julia" (via PBS). Butter, like cream, is prevalent within French cuisine, which may have inspired her well-known saying, "If you are afraid of butter, use cream."

Despite its high-frequency use in her baking series, butter was used to enhance a variety of different flavors and cooking techniques throughout Child's repertoire. One of her best tips might just be this one, from her series "The Way to Cook Poultry". Here, she shows the audience that the best way to prevent butter from burning when using it to sautée is to simply add a splash of good olive oil or other high smoke point oils along with it. Given butter's low smoke point, it is not great for high-heat cooking unless protected, as Child suggests, with a flavorless oil with a higher smoke point.

Prick your eggs before poaching

RomanaMart/Shutterstock

One of the best things about dining out for brunch is the opportunity to order and eat poached eggs, as they can sometimes be a daunting cooking technique to perfect at home. There are so many different suggestions and poaching hacks out there that gadgets like egg poaching cups or egg poachers just aren't necessary. What is required, however, is a bit of time and the willingness to break a few eggs before you get it right.

While there are many different techniques from using vinegar to turning off the heat and covering the pot, Child's is a bit more outside the box — or, rather, inside the eggshell. Grab sewing needles or pins, because you'll need them.

Rather than worrying about wispy, runaway egg whites, Child instructs home cooks to make perfect poached eggs by first poking each egg once with a pin or needle to release any air inside, all while keeping the egg whole and in its shell. Then, lower the egg into a pot of boiling water for a total of 10 seconds, after which you can crack open the egg and poach as you normally would, using any preferred method. If Julia says to do it, there must be something to it.

Fold from the center, outwards

Ika Rahma H/Shutterstock

Folding is not just for laundry or paper. In cooking, it's a way to mix ingredients while keeping a light and airy quality to the batter. It's a technique used in many foods we love, from fluffy cheese soufflé to mousse to meringues, and is a necessary skill to learn when it comes to learning to cook French cuisine well. It comes as no surprise then, that Julia Child gave her readers and viewers some good advice on how to fold.

Child explains it quite simply: To fold best, stick your spoon or, ideally, rubber spatula straight down into the very center of the bowl. Then, following the curvature of the sloped sides, sweep your cooking utensil along the side of the bowl until you reach the top lip, lightly folding it over the top of your mixture. Then, begin again, moving in a different direction. This will help to keep those hard-earned air pockets in the batter and ensure a fluffy finish.

Hang your knives horizontally

Larry French/Getty Images

When it comes to great cooking, one of the best pieces of advice there is, is to make sure you are well organized with ingredients, equipment, and a clear and clean space before the first ingredient ever hits the pan. It is why the French technique of mise en place — meaning "put in place" — exists and is emphasized especially in a professional kitchen.

One look at Child's kitchen, now an exhibit at the National Museum of American History and we can see how seriously she took this practice. Here we can also see Child's preferred method for storing her knives — horizontally on the wall.

When it comes to risks in the kitchen, a dull knife is often times more dangerous than a sharp one. The reason why is that it requires more force to perform tasks, making any slip-up that much more serious. Knives stored together in a drawer are not only dangerous when reaching for one, but the process of rubbing together dulls the knives, making them all the more dangerous when used as well.

Magnetic knife strips are a wonderful tool for organizing knives and keeping them from taking up valuable work surfaces, which are high-value commodities in many home kitchens. However, Child chose not to hang her knife strips vertically, positioning her knives horizontally to allow for ease when reaching for whichever knife she needed (and perhaps accounting for her own personal aesthetic preferences, too).

Cook with copper whenever possible

FabrikaSimf/Shutterstock

When it really boils down to it, most cooking is largely about heat control and having a basic understanding of the chemistry that takes place as a result. Once you understand and can put into practice the hard and fast science behind it, there becomes a great opportunity to add flourish, art, and inspiration on top.

Cooking techniques like searing, flambéing, high heat sautéing, and blanching are quick and require instant action from both the cook and equipment in order to achieve success. It is why Child preferred to use copper pots and pans most of the time (though she demonstrated with non-stick pans as well during her shows). Copper is an excellent heat conductor, meaning it reacts to direct and indirect heat in a matter of seconds, and holds onto it well so it can distribute it to cook your food (via Markham Metals).

Copper not only means faster and more efficient cooking, but it also puts more control into the hands of the cook, which is why Child preferred it to other materials. She did advise readers to look for high-quality copper products, rather than just the shiniest. Though, copper does get a few bonus points for being pretty enough to display in the kitchen, especially if you're short on storage.

Test your baking powder before using it

Alain Intraina/Getty Images

Much of cooking, as Julia Child is famous for showcasing, is a bit of an experiment, with both failures and successes as essential parts of the learning process. This includes what many of us only learn through experience, the shelf life of some of our standard pantry items. It's likely that if you make bread, you've had a loaf fail to rise due to old and inactive yeast. It turns out it's not just yeast but other rising agents like baking soda and powder also have a life expectancy.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, sealed boxes of baking soda can be stored in ambient temperatures for up to 18 months, but need to be used within 6 months once opened. David Lebovitz gives baking powder around the same lifespan, though notably suggests baking soda can hang around for much longer.

So, how do you know if it's good or if it's going to ruin your next batch of chocolate chip cookies? Child suggests testing your baking powder by mixing one teaspoon of the leavening agent with half a cup of hot water. If it bubbles, you're in business. If not, you know it's time to get rid of it and buy fresh before using.

Salt your sauce at the end

Thananan Kannim/Shutterstock

Julia Child was a wonderful cook whose approach changed the ways in which recipes were written. She was also an incredibly thorough researcher, an engaged student, and a lifelong learner. During one such project entitled "Cooking with Master Chefs," — both a PBS aired show and a cookbook — Child sought out the advice and expertise of 16 professional and acclaimed chefs, from Alice Waters to Emeril Lagasse, for advice and recipes for the home cook. Child was interested in closing the gap between restaurant food and the homecooked meal.

It was during this project she devoted a section to sauces, noting the profound flavor distinctions between the average restaurant quality sauce and one made in the domestic kitchen. One key tip to increase flavor concentration is to reduce the sauce's volume, a process done over heat to thicken and intensify its flavors. A second key tip, says Child, is to wait until after it is reduced before salting and seasoning, tasting it first so you know how much is needed for balance (via PBS).

Season your pan for omelette success

Bruce Peter/Shutterstock

Arguably one of the most brazen things Julia Child did was beginning her television career by cooking something perceived as simple — an omelette. Not just any omelette, of course, a French omelette. It took about 30 seconds or so to make, which allowed her to show it several times over using several pieces of equipment. Despite many naysayers behind the screens, it launched her career, helped a huge number of home cooks, and has since become the muse for other Julia-inspired television (via Vulture).

In this 30-minute segment of "The French Chef Season 1," there is a lot of good information and tips to take away. Child shows how to shake the pan just so, taking the audience step by step on when to change hands, how to position the pan, and more.

Child also talks about the importance of having a non-stick pan, whether this is created in the factory through a coating or at home through the process of seasoning. Though there are several different methods for seasoning, Child suggests heating the pan until hot, adding oil, removing it from heat, and letting the oil sit overnight. Before using it the next day, she suggests salting the pan, then, over heat, rubbing the pan with a towel, and wiping out the salt before it's ready to cook. This can be done again and again, whenever it feels necessary.

Find inspiration from cuisines you don't normally cook

Pixel-Shot/Shutterstock

Prior to going to cooking school Child worked for the CIA, stationed in China for the first two years of World War II (via History.com). Afterward, when working for the OSS (Office Strategic Services), she was utilized for her research skills and natural curiosity — attributes she was known to flex ever since.

Child's curious and meticulous mind found inspiration in a great number of things, even when out of her comfort zone, which was often, including when she lived abroad in China, Sri Lanka, and France and enrolled in Le Cordon Bleu, a male-dominated culinary institution.

Perhaps when you're as statuesque as she was at 6'2", sticking out is such a normal practice that it doesn't inhibit you from seeking joy and inspiration everywhere you can, which is what Child did when encountering the cuisines of China while stationed there. Even going back to 1974, Child told the New Yorker that she would be fine living with only Chinese food.

Child is also quoted describing American food in China as "terrible" and preferring local Chinese cuisine instead. In fact, that's what sparked her interest in food (via France24). Even if she never sought to cook it herself, Child was notorious for her fascination and genuine love of food cultures and cuisine from around the globe, which arguably made her a better chef and teacher.

Don't take yourself or your food too seriously

Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock

Julia Child is not just famous for her food or the ways in which she helped to break down the techniques that make up French cuisine, but also for her joie de vivre, her humor, and her human approach. For context, Child hit television screens just after WWII. Women at this time were still responsible for cooking each night regardless of whether they worked outside of the home. In fact, they were urged by companies like Betty Crocker to turn to convenience foods to create the perfect dishes, night after night, for their perfect families in their well-kept family homes. The emphasis was on perfection (via AV Club).

Child was a messier, more human version of this stereotyped expectation. Sometimes, Child's dish didn't quite work out as intended. One of her funniest quotes to live by was "Always remember: If you're alone in the kitchen and you drop the lamb, you can always just pick it up. Who's going to know?" Childs tells us to enjoy the journey, not take ourselves or our food too seriously, to enjoy the lessons learned along the way. And, if we are very lucky, we'll have the opportunity to try again tomorrow.

Cook with real ingredients

Jacob Lund/Shutterstock

We'd like to think with such access to information comes shared knowledge on how best to eat to support good health, at least most of the time. Sadly, there are still celebrities and big businesses peddling laxatives, diet drinks, and hyper-restricted eating as a form of "health." The late Julia Child never fit into such a category, taking a stance that more closely resembles that of intuitive eating, a restriction-free way of eating that prioritizes the body's own signals and promotes a healthy relationship with food (via WebMD).

Child relished in the joys of the ingredients with which she cooked, prioritizing fresh and recognizable foods and a colorful plate. Her way of eating and feelings about "diet food" will never go out of style, no matter what fad comes our way.

This emphasis on buying local foods and supporting local farmers not only makes a pretty plate, but the more local the foods we buy whenever possible, the more nutrient-dense they tend to be (via Dr. Hyman). That's even more reason to put it into practice. Child said, "The only time to eat diet food is while you're waiting for the steak to cook" (via Today).

Learn how to adapt in the kitchen

Mehmet Cetin/Shutterstock

Throughout the duration of her career, Julia Child bestowed us with a plethora of valuable information and tricks to arm us in all of our cooking endeavors. Her advice, though largely aimed towards an audience of amateur home cooks looking to put something nice on their dinner table, was valued by professional chefs too, including Emeril Lagasse.

As Lagasse describes in his interview, Child emphasized the ability to adapt and go with the flow in the kitchen, embracing imperfections, mistakes, and challenges along the way. She was so dedicated to showing what life was really like in the kitchen that her mistakes were kept in her television shows, allowing audiences not only to see her as human but consider mistakes in the kitchen to be a given rather than something to be avoided at all costs.

This approach, during an era that favored the gendered stereotypes of perfection, helped create a bit of humanity behind the busy housewife stereotype, alongside great kitchen successes (and failures).

A little bit of the best ingredients you can find go a long way

Taras Shparhala/Shutterstock

Many chefs and publications agree that when it comes to ingredients, opt for the highest quality within your budget and then use them sparingly. Oftentimes, this is the key difference between something that tastes good versus great.

While this isn't a universal truth for all ingredients and dishes, it is true in many situations for ingredients like wine and olive oil. Other great examples for buying less but better include animal products like meat and dairy as well as fruits and vegetables that are seasonal, local, and grown without pesticides. Food writer Fiona Becket advises readers to only cook with wine they would drink on its own (via The Guardian).

While you don't need to go for the top-shelf spirits when cooking, as one chef did when cooking for Julia Child herself, we also can't blame him for taking her advice to heart. After all, Child is known for promoting cooking simple, delicious food with quality ingredients.

Bon apetit: 3 recipes from Julia Child that everyone should cook

The most famous American housewife, who defeated stereotypes about female chefs and adapted recipes for haute French cuisine into everyday dishes, would celebrate her 107th birthday today. Julia began her ascent as a food pro at the age of 36 (1948): then the future star moved to Paris with her diplomat husband, fell in love with French cuisine and signed up for courses a week later. After completing her training, Julia decided to open a culinary school for American women, with the help of her new French friends.

Meryl Streep as Julia Child (Julie & Julia: "Cooking Happiness with a Recipe", 2009)

After the successful launch of the courses, Mrs. Child began to write recipe books that eventually broke the sales charts and became bestsellers several times. The bosses of American television drew attention to the popular writer-housewife, offering Julia to open her own show, in which she could talk about cooking in simple language. By the way, in the era of frozen foods and Campbell’s broths, Julia’s approach to food made a splash. In her TV programs, she showed and proved that tasty and beautiful food heals and gives happiness. ELLE has compiled 3 of Julia Child's best recipes that every woman should cook and add to her family's diet.

1. Berry Clafouthi

Ingredients:

1. Butter for buttering the mold

2. 1 and ¼ cups 2% milk

3. 2/3 cups granulated egg

9002 5.0002 1 tablespoon of vanilla extract6. 1/8 teaspoon of salt

7. 1 cup of flour

8. 2 cups of berries, washed and dried

9. Sugar powder

Preparation:

Purchase the oven to 160 degrees. Grease a baking dish with butter. Place milk, 1/3 cup granulated sugar, eggs, vanilla, salt, and flour in a mixer bowl. Beat for about 1 minute until smooth. Pour a 5-7 mm layer of dough on the bottom of the mold, wait 1-2 minutes until the dough layer "grabs".

Remove the mold from the oven. Arrange berries on top and sprinkle with remaining granulated sugar. Pour in the rest of the dough and smooth the surface. Return the pan to the oven and bake for about 50 minutes.

Dust the clafoutis with powdered sugar before serving. Ideally, the clafoutis should be served warm with a scoop of vanilla ice cream.

2. Roast Provence with white wine

Ingredients:

1. 4 tablespoons olive oil

2. 2 tablespoons brandy or cognac

3. 2.5 kg boneless beef, cut into small pieces

4. Salt and ground black pepper

5. 2 large onions, thinly sliced

6. 4 carrots, thinly sliced

7. 150 g mushrooms, finely chopped

8. 1 head of garlic, divided into cloves, crushed with a garlic press

9. Zest of 1 orange

10. 2 tomatoes or 1 cup of tomato puree

11. 2 bottles of white wine

6-8 stalks fresh thyme and 2 bay leaves (all spices can be tied into a bunch and then removed from the finished roast)

Preparation:

Marinate the meat for 2 hours with half the olive oil, cognac, salt and pepper. Preheat oven to 160 degrees. In a thick bottomed saucepan, heat the rest of the oil, add the onions, carrots, mushrooms, garlic, orange zest and 2 pinches of salt, fry, then reduce heat, cover and simmer for 8-10 minutes until the onions and garlic are soft. Then add beef with marinade, tomatoes, wine, bunch of herbs and black pepper, mix. Cover with a lid and place in the oven for 3-4 hours. Serve hot with potatoes or pasta.

3. Fragrant chicken

Ingredients:

1. One 1.5-2 kg. chicken

2.2 + ½ tbsp. unsalted butter

3.1/3 cups finely chopped carrots

4.1/3 cups finely chopped onions

5.1/3 cups finely chopped celery

6.1 tsp. dried thyme

7. Parsley stalks

8. Celery leaves

9.6 slices of lemon 0.3 cm thick.

10.½ cups chopped onion

11.½ cup chopped carrots

12.1 tbsp. fresh lemon juice

13.¾ cup chicken stock

14. Freshly ground pepper, salt

Preparation:

Preheat oven to 220°C. Melt 1 tablespoon butter in a frying pan. Add the diced carrots, onion and celery and cook over moderate heat until the vegetables soften. Add thyme.

Quickly rinse the inside and outside of the chicken with hot water and dry well. Put a spoonful of fried vegetables, a handful of parsley stalks and celery leaves, lemon slices, salt and pepper into the cavity of the chicken. Brush the entire chicken with 1 tablespoon of butter. Tie the legs together, tuck the tips of the wings under the carcass. Salt the chicken and place in a heat-resistant dish breast-side up.

Bake the chicken in the oven for about 1 hour and 15 minutes as follows:

After 15 minutes, brush the chicken with the remaining ½ tablespoon of butter. Arrange chopped onions and carrots around. Reduce oven temperature to 180°C.

After 45 minutes of cooking, brush the chicken with lemon juice. If necessary, add ½ cup of water to keep the vegetables from burning.

After 60 minutes, pour the juice from the pan over the chicken. Check the doneness: the thermometer should read about 75 °C. If chicken is not done yet, continue to roast, basting with juices and checking for doneness every 7 minutes.

Drain the juice from the chicken. Transfer the bird to the board and let it rest for 15 minutes. Drain the juice into the pan. Add broth and simmer for about 5 minutes. Strain the sauce. Drizzle sauce over each serving of chicken before serving.

Yuliya Lifanova

Julia Child's roast recipe - French cuisine: Main dishes. "Food"

Julie Child's Roast Recipe - French Cuisine: Main Courses. "Food"GOLDEN THOUSAND

- Recipes

4 Prepare:

2 hours 15 minutes 9000

54

13

kcal

grams

grams

grams

Ol000 Tomatoes0003

Cooking instructions

2 hours 15 minutes

Print

1 Wash the meat, remove films and fat, cut into pieces with a side of four centimeters and fry in vegetable oil in a frying pan.

ToolCeramic pan

2Put the meat into the saucepan. Scoop out excess oil from the frying pan so that there is very little left, and fry the onion cut into rings on it.

Cheat Sheet How to cut onions

3 Put the pot with the meat on the fire, put the fried onion, chopped tomato, rosemary, garlic cloves crushed with a knife. Then pour wine, add broth so that it only covers the meat, salt, pepper, close the lid and simmer over low heat for an hour and a half (or you can put it in the oven).

Crib How to prepare tomatoes

4 Five minutes before the end of the stew, fry the flour in butter, leave the mass on low heat and immediately go to the next step.

5 Strain the entire contents of the saucepan through a sieve over a frying pan with flour, mix with a whisk. Squeeze out all the liquid from the vegetables (then you can throw them away), and return the pieces of meat back to the pan.

6 Whisk the resulting sauce until the mixture thickens, then pour it over the meat.