How parenting influences child development

Parental Behavior Influences Child Development

How do we make decisions when our lives are so complex? An increasingly popular way to approach this question is through behavioral sciences—the science of evaluating psychological, cognitive, emotional, cultural, neuroscience and social factors and their impact on decisions. To explore the intersection between behavioral sciences and public policies, the Inter-American Development Bank has launched a series of webinars featuring renowned subject experts and convened by our co-editor Florencia Lopez Boo.

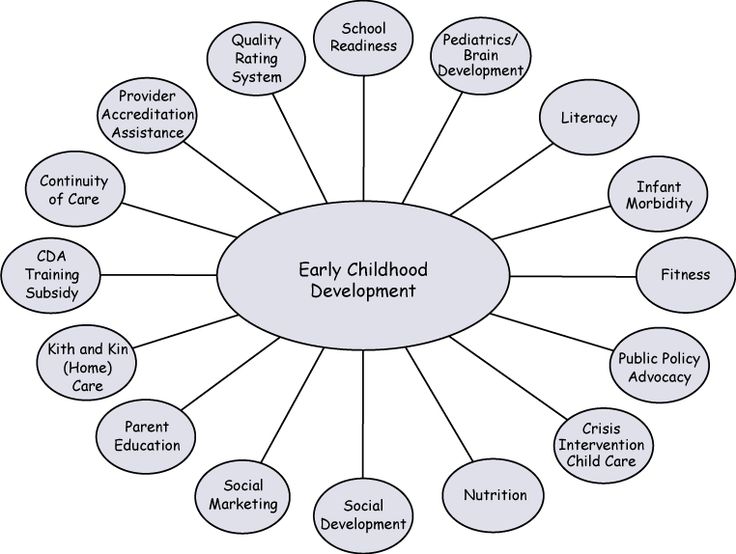

We spoke to Ariel Kalil, Director of the Center for Human Potential and Public Policy and Co-Director of the Behavioral Insights and Parenting (BIP) Lab at the University of Chicago, on the application of behavioral economics to Early Childhood Development policies.

A powerful thing you said during your webinar is that “parents are the single greatest influence on children.” How and why is the role of parents paramount to child development?

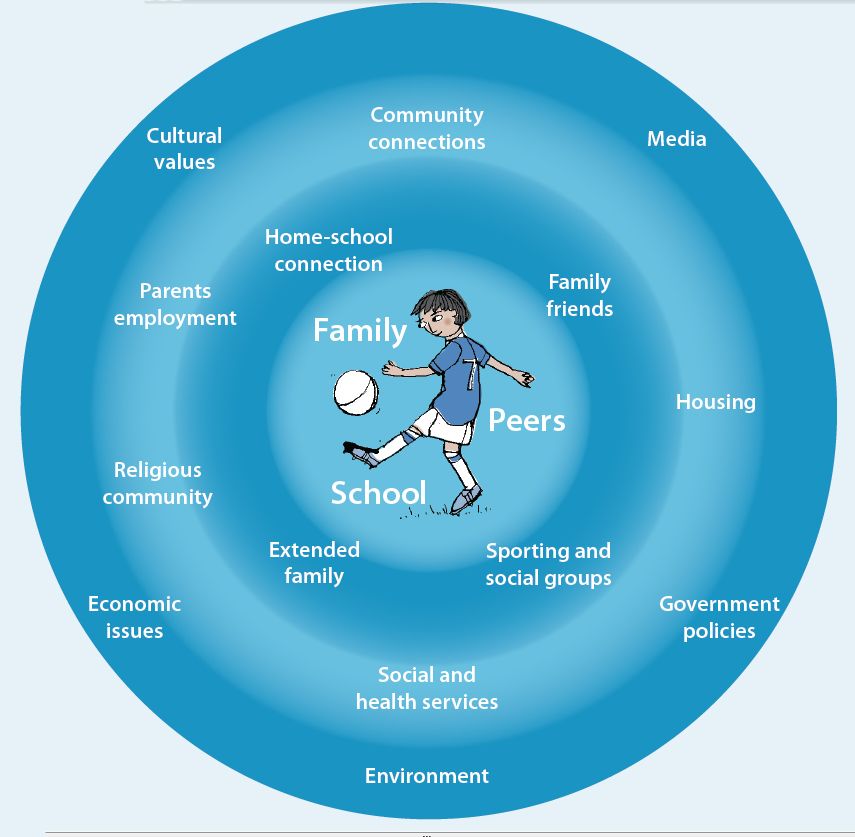

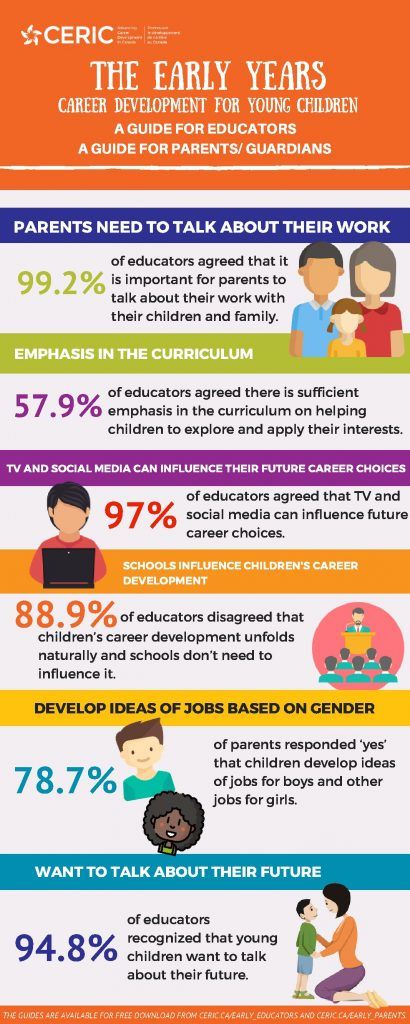

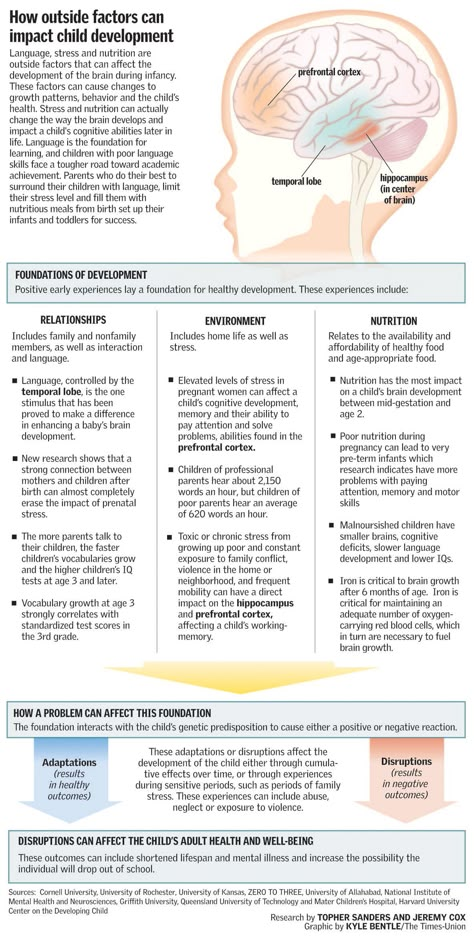

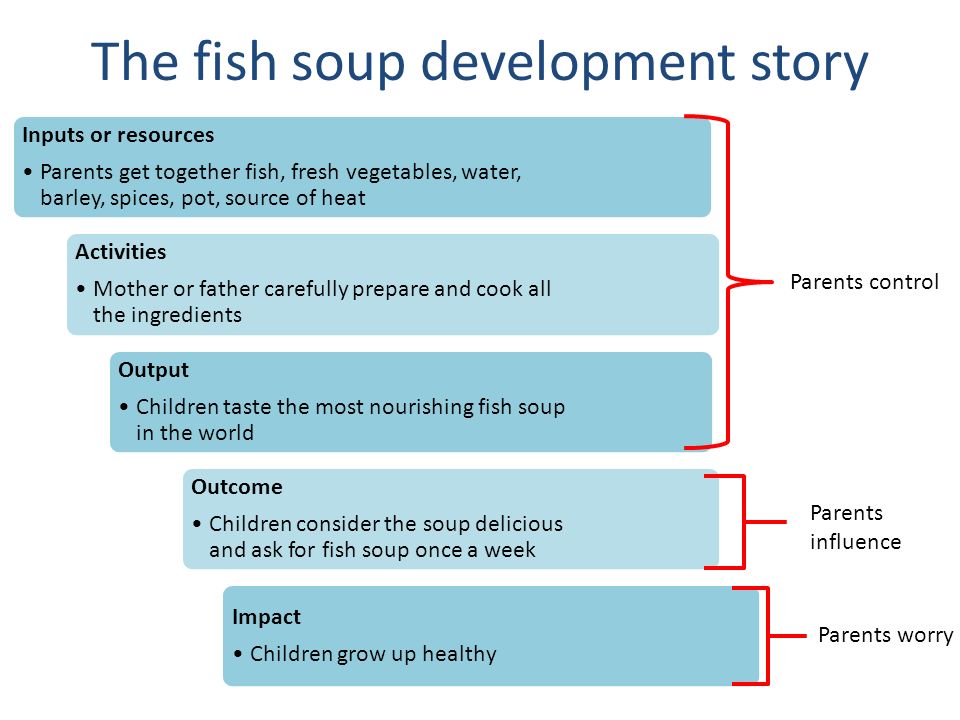

Usually when we think about child learning and development, we think about schooling and institutions outside the home. My hypothesis is that most people will say we can fix childhood issues through schooling. Consequently, the role of parents has become kind of lost both in research and policy. But if you look at where children spend their time, especially during their first and most critical years, it’s in a family environment. They spend less time in school versus in the company of their parents and caregivers. Even beyond caregiving, parents play a critical role throughout the years. For example, parents select their children’s environments all the time based on things they think are good for them, like neighborhoods, schools, etc., although some constraints exist. All this suggests parents are the number one influence on children.

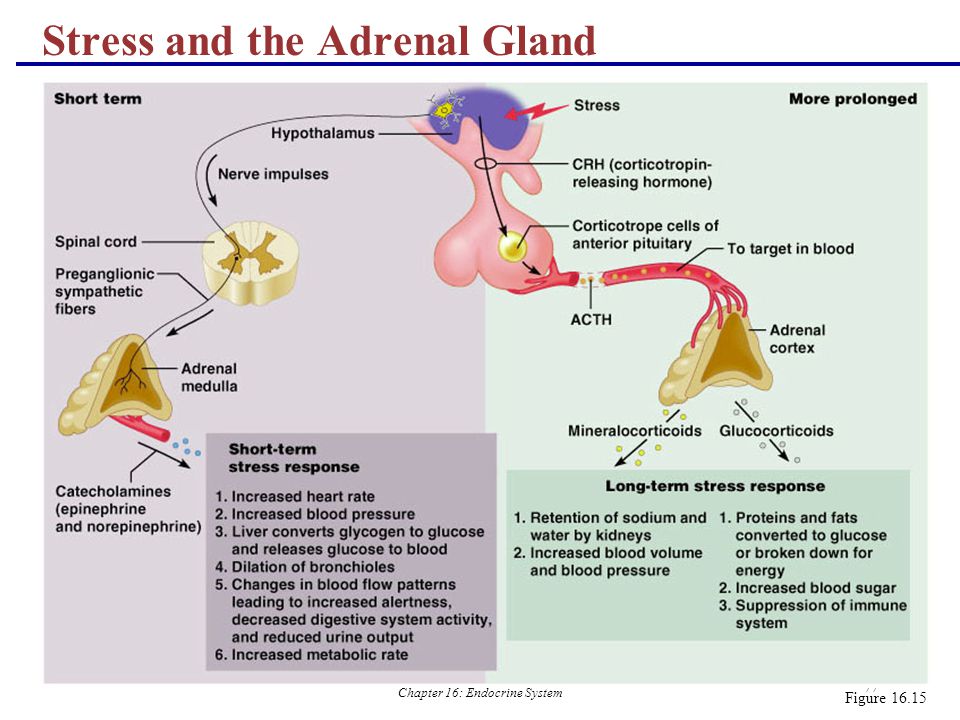

How true is it that parents in low income contexts, usually under stress, tend to procrastinate more in their interactions with children than those in higher income contexts?

It’s the 20-million-dollar question… There’s a general notion that life is more complex and complicated in low-income contexts, and that as stress increases so does the probability of procrastination. Under stress, it might be more appealing to choose leisure time or watching TV for 20 extra minutes rather than reading to your child because you’ve had a long day and you think you’ll read tomorrow. There’s no question this happens in all families, but it might be more common in low income households because there are more – or different – kinds of stressors. This does not mean these parents don’t value the return on time investment in the early childhood. Surveys of parents of young kids show that parents have very high expectations for their children’s future and are therefore willing to invest in the present time to increase their cognitive development. But less educated or low-income parents have a harder time converting what they wish to do into what they actually do.

Under stress, it might be more appealing to choose leisure time or watching TV for 20 extra minutes rather than reading to your child because you’ve had a long day and you think you’ll read tomorrow. There’s no question this happens in all families, but it might be more common in low income households because there are more – or different – kinds of stressors. This does not mean these parents don’t value the return on time investment in the early childhood. Surveys of parents of young kids show that parents have very high expectations for their children’s future and are therefore willing to invest in the present time to increase their cognitive development. But less educated or low-income parents have a harder time converting what they wish to do into what they actually do.

Do children in these contexts learn to procrastinate?

That’s an interesting question. Children behavior is modelled on their parents, and maybe if they grow up in households that don’t have routines or language about doing things today because it’s important for the future — such as: ‘You need to read today because you’re going to kindergarten tomorrow’— that can be possible. If children don’t grasp the idea that the reason you do things now is for a future reward, their horizon might be different.

If children don’t grasp the idea that the reason you do things now is for a future reward, their horizon might be different.

Evidence suggests more educated parents spend more time with their children. What implications does this have for vulnerable contexts? What strategies can we implement to change this?

Assuming parent-child interactions have an impact on development, we should be concerned if one group of kids gets the benefits of parental time and another doesn’t. However, over time low-income parents have vastly increased the time they spend with their children. Less educated parents now spend the same amount of time with their kids than more educated parents did 30 years ago. But highly-educated parents have also increased their time investments over time, and thus we still see income-based inequality in parent engagement. If there’s a minimum threshold for time investment, parents in low income families have reached it, but a puzzle we still need to solve is whether there is such a threshold or if more is always better.

How to close these gaps turns out to be easier than we might have thought because we know low-income parents share the same aspirations for their kid’s development. They do not enjoy time with their kids any less, and they do not completely lack the tools to promote their development. Most homes have at least some books. But the answer is not to give them more books; rather, we must provide tools for optimal decision-making, where the optimal decision is parents doing the things they say they want to do.

Evidence also suggests parents with lower levels of education have just as much positive feelings about spending time in child care and with their children, even though they spend less time in those activities. What does this apparent paradox tell us?

That given the opportunity, they would do it more and enjoy it as much. At the BIP Lab, we’ve learned a lot about why parents do or don’t do certain things, rejecting long-standing assumptions. For example, it’s not always true less-educated parents don’t do a particular thing for their kid because they lack information. When we survey them, it turns out they know a lot! So if they know, why are they not doing it? Behavioral economics places parenting in a decision-making framework.

For example, it’s not always true less-educated parents don’t do a particular thing for their kid because they lack information. When we survey them, it turns out they know a lot! So if they know, why are they not doing it? Behavioral economics places parenting in a decision-making framework.

The decisions parents make on whether they read to their kids need not be different to any other decision to something not related to kids. It comes down to this: if you have an hour in front of you, how will you use it? This is a very new way of thinking about parenting. Interventions designed around this concept aim to create the conditions, so they can make decision A vs B: to read vs not; brush their teeth vs not, eat healthier vs not.

How to achieve this goal?

We want to help parents go from doing none of what they say they want to do most of the time, to doing at least a little bit of it much of the time. To do this, we need to manage different cognitive biases that are standing in the way of parents doing things they say they want to do. We want parents to be goal-oriented and think about the future by bringing the future to the present.

We want parents to be goal-oriented and think about the future by bringing the future to the present.

The tools we use are not expensive, don’t demand a lot of parent time, and work in many different income contexts. For example, we send parents reminders via text about setting and meeting a goal for reading time with their kids that week. Or, if parents think other kids are missing school as much as theirs, we show them that might not be true, changing normalization patterns that get in the way of them doing things differently. It’s about finding the right match and tool, matching tools that already exist to behaviors you want to change.

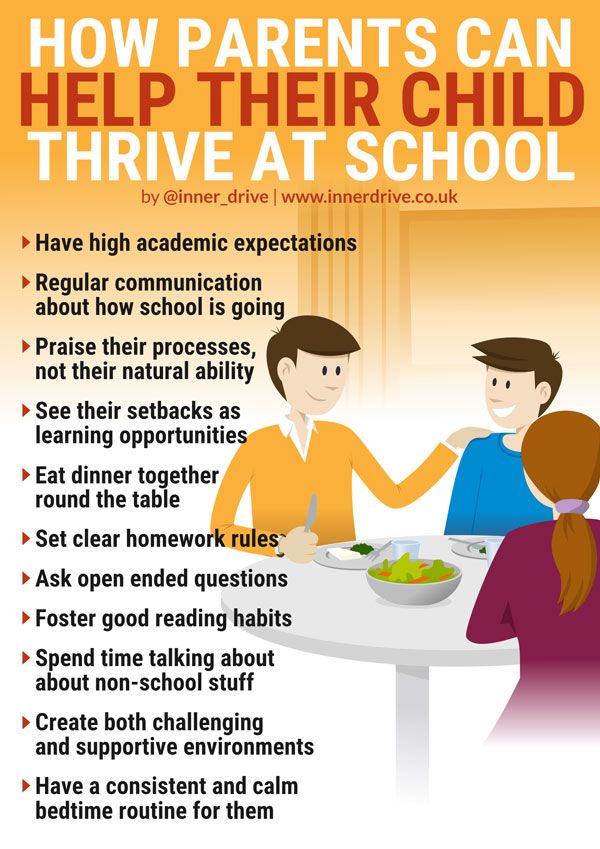

To finish out interview, a very important question: you mentioned “the key to closing the gap in child outcomes is closing the gap in what families do with their children.” What are some examples of what parents could do to this end?

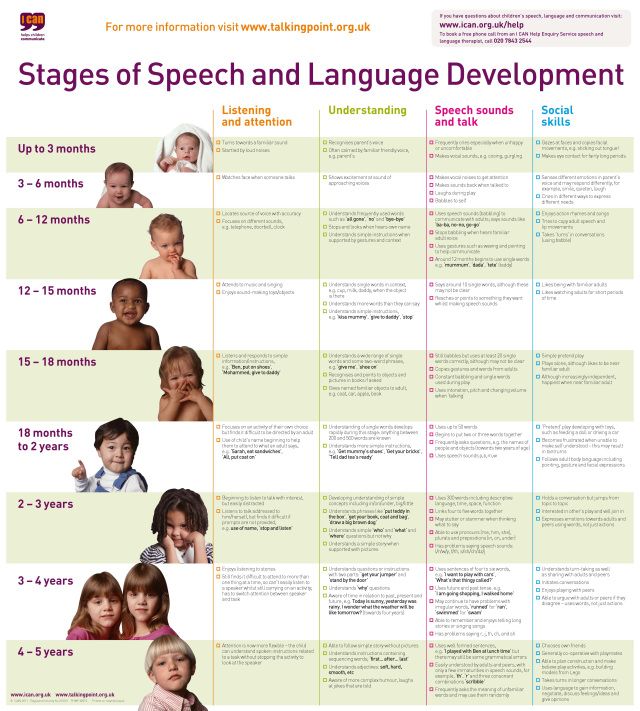

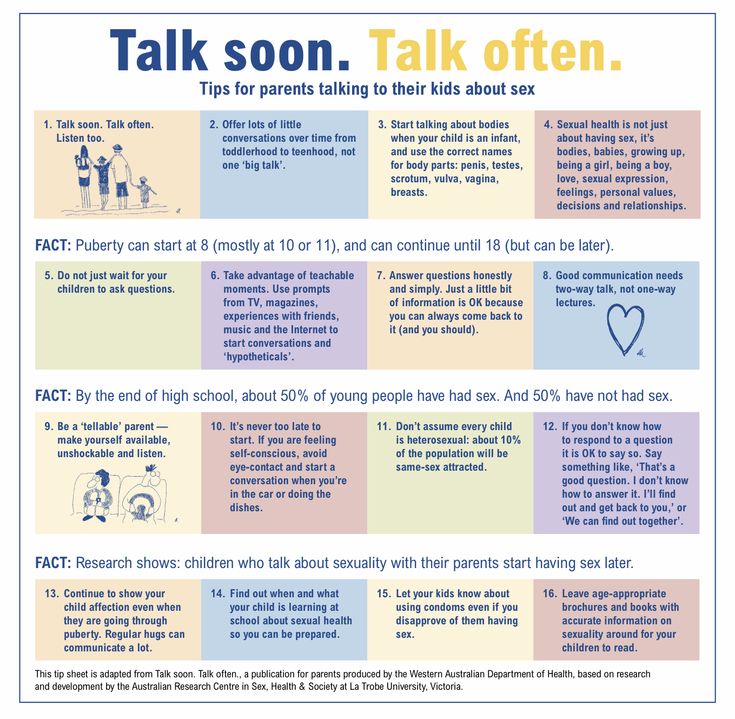

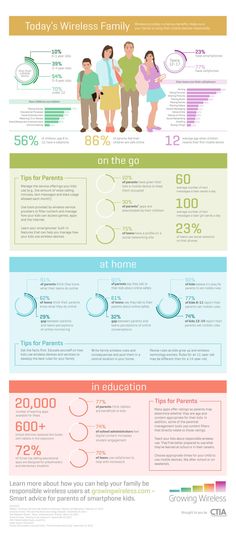

There are some key things parents should be doing, and cognitive stimulation is right up there: talking, reading, stimulating quality interactions and strong communications… There’s no app or media or TV that’s a substitute for active dynamic interaction with human beings, which takes many forms.

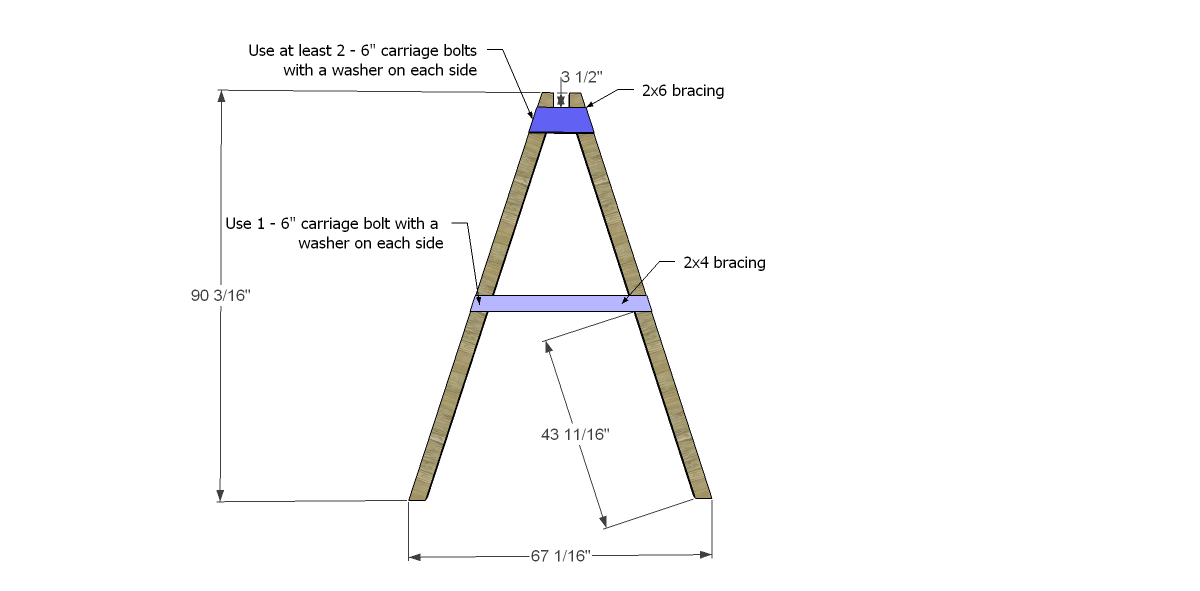

Second, children need consistency, so there needs to be routine in caregiving. They need to know where their next meal is coming from, metaphorically, to have confidence about their environment. Parents should be affectionate and warm, and they should be so consistently.

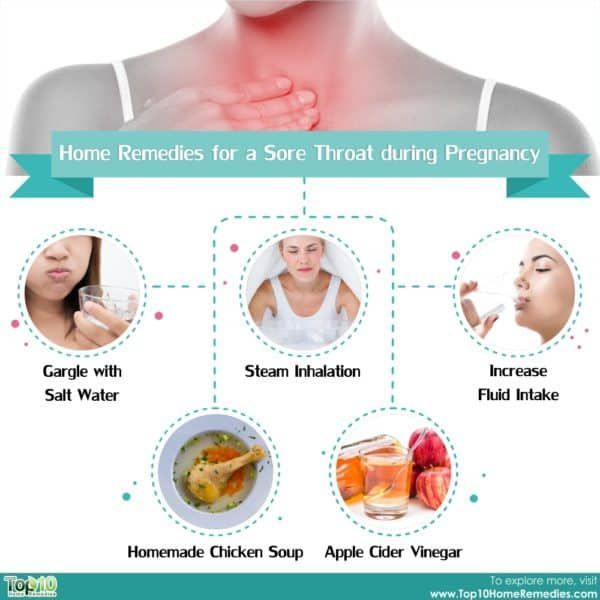

An important aspect parents need to care for is their children’s health. This unfortunately changes a lot between high and low-income households. Our research shows the number one infection in children, and also the most preventable, are cavities! This is largely a function of one behavior: toothbrushing. Most parents have what they need to prevent this: a toothbrush.

All this shows that approaching parenting through a decision-making lens and shaping parent behavior can definitely pave the way for children to reach their full potential. We need to be their best allies.

Which activities would you want to share with your children more? Leave your comments below or mention @BIDgente on Twitter.

Andrea Proaño Calderon is the communications consultant for the Inter-American Development Bank’s Social Protection and Health Division.

Lee en español.

Parenting skills: Impact of parents' attitudes and beliefs

Joan E. Grusec, PhD, Tanya Danyliuk, BA

University of Toronto, Canada

, Rev. ed.

Introduction

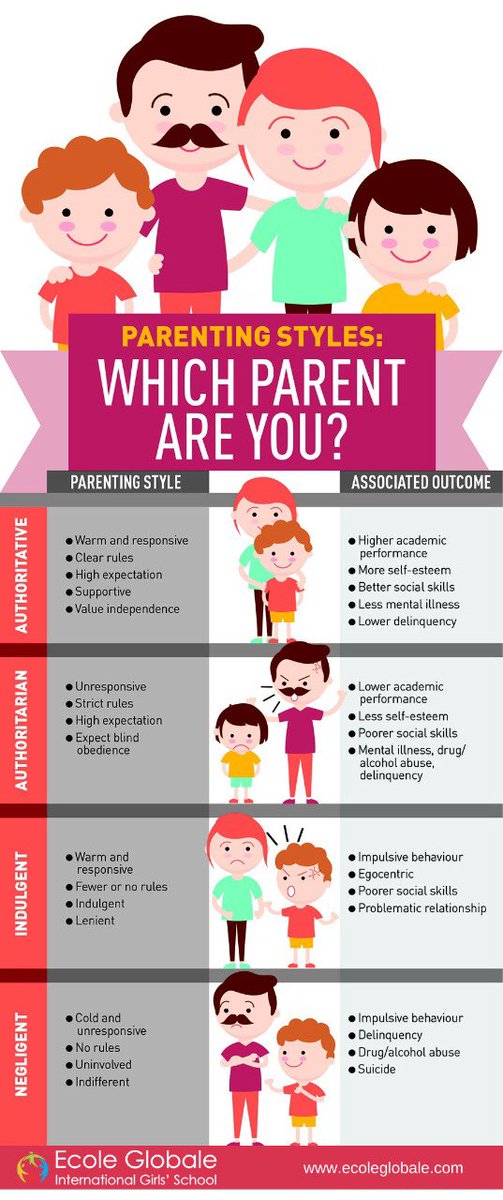

Why do parents behave the way they do when raising children? One answer is that they are modelling the behaviour of their own parents, having learned how to parent in the course of being parented. Another is that they are behaving in accord with information about appropriate parenting acquired through books, Web sites, or informal and formal advice. Yet another major determinant of their behaviour lies in their general attitudes as well as specific beliefs, thoughts, and feelings that are activated during parenting: These have a powerful impact on behaviour, even if parents are distressed by or unaware of that impact. Researchers interested in children’s development have explored parenting attitudes, cognitions, and the resulting emotions (such as anger or happiness), because of their influence on parenting behaviour and on the subsequent impact of that parenting behaviour on children’s socioemotional and cognitive development.

Researchers interested in children’s development have explored parenting attitudes, cognitions, and the resulting emotions (such as anger or happiness), because of their influence on parenting behaviour and on the subsequent impact of that parenting behaviour on children’s socioemotional and cognitive development.

Subject

Child-rearing attitudes are cognitions that predispose an individual to act either positively or negatively toward a child. Attitudes most frequently considered involve the degree of warmth and acceptance or coldness and rejection that exists in the parent-child relationship, as well as the extent to which parents are permissive or restrictive in the limits they set for their offspring. Researchers have also studied more situation-specific thoughts or schemas – filters through which parents interpret and react to events,, particularly ambiguous ones. These include cognitions such as beliefs about parenting abilities, expectations about what children are capable of or should be expected to do, and reasons why children have behaved in a particular way.

Problems

The influence of attitudes on parenting behaviours has been a favourite topic of investigation, with research suggesting that linkages are generally of a modest nature.1 In part, this is because reported attitudes do not always have a direct impact on parenting actions which are often directed by specific features of the situation. For example, parents might endorse or value being warm and responsive to children, but have difficulty expressing those feelings when their child is misbehaving. As a result of this realization the study of parent cognitions has been widened to include more specific ways of thinking.

Research Context

The study of parent attitudes, belief systems, and thinking has taken place along with changing conceptions of child-rearing. These changes have emphasized the bidirectional nature of interactions, with children influencing parents as well as parents influencing children.2 Accordingly, an interesting extension of research on attitudes and cognitions has to do with how children’s actions affect parents’ attitudes and thoughts, although little work has been done in this area.

Key Research Questions

- Which parental attitudes result in the best child outcomes?

- How do negative/positive thoughts and cognitions hinder/facilitate child development?

- How can parents’ harmful attitudes be modified?

Recent Research Results

A large body of research on attitudes indicates that parental warmth together with reasonable levels of control combine to produce positive child outcomes. Although not strong, as noted above, the results are consistent. Researchers have noted that what is seen to be a reasonable level of control varies as a function of sociocultural context.3 Attitudes toward control are generally more positive in non Anglo-European cultures, with these attitudes having less detrimental effects on children’s development because they are more normative and less likely to be interpreted as rejecting or unloving.3,4 In accord with the realization that children’s behaviour affects that of their parents, researchers have found that, whereas parent attitudes affect child behaviour, this relation shifts as the child grows, with adolescent behaviour having an impact on parenting style and attitudes. 5

5

Research on more specific cognitions also highlights the importance of parent thinking on child outcomes. As an example, parents look for reasons why both they and their children act the way the do. These attributions can make parenting more efficient when they are accurate. They can also interfere with effective parenting when they lead to feelings of anger or depression (a possibility if children’s bad behaviour is attributed to a bad disposition or an intentional desire to hurt, or the parent’s failure or inadequacy). These negative feelings distract parents from the task of parenting, and make it more difficult for them to react appropriately and effectively to the challenges of socialization.6

Specific cognitions have been assessed both with respect to their impact on children’s socioemotional development and on their cognitive development. For example, Bugental and colleagues have studied mothers who believe their children have more power than they do in situations where events are not going well. 7 These mothers are threatened and become either abusive and hostile or unassertive and submissive. They send confusing messages to their children, with the result that children stop paying attention to them as well as showing a decrease in cognitive ability.8 This view of the power relationship takes its toll on mothers’ ability to problem-solve and therefore to operate effectively in their parenting role. Similarly, mothers of infants who are low in self-efficacy, that is, do not believe they can parent effectively, give up on parenting when the task is challenging and become depressed. They are cold and disengaged in interactions with their babies.9 Furthermore, parents who trust that their child’s course of biological development will proceed in a natural and healthy way are able to adjust better to their parenting role and less likely to develop a coercive parenting style.10

7 These mothers are threatened and become either abusive and hostile or unassertive and submissive. They send confusing messages to their children, with the result that children stop paying attention to them as well as showing a decrease in cognitive ability.8 This view of the power relationship takes its toll on mothers’ ability to problem-solve and therefore to operate effectively in their parenting role. Similarly, mothers of infants who are low in self-efficacy, that is, do not believe they can parent effectively, give up on parenting when the task is challenging and become depressed. They are cold and disengaged in interactions with their babies.9 Furthermore, parents who trust that their child’s course of biological development will proceed in a natural and healthy way are able to adjust better to their parenting role and less likely to develop a coercive parenting style.10

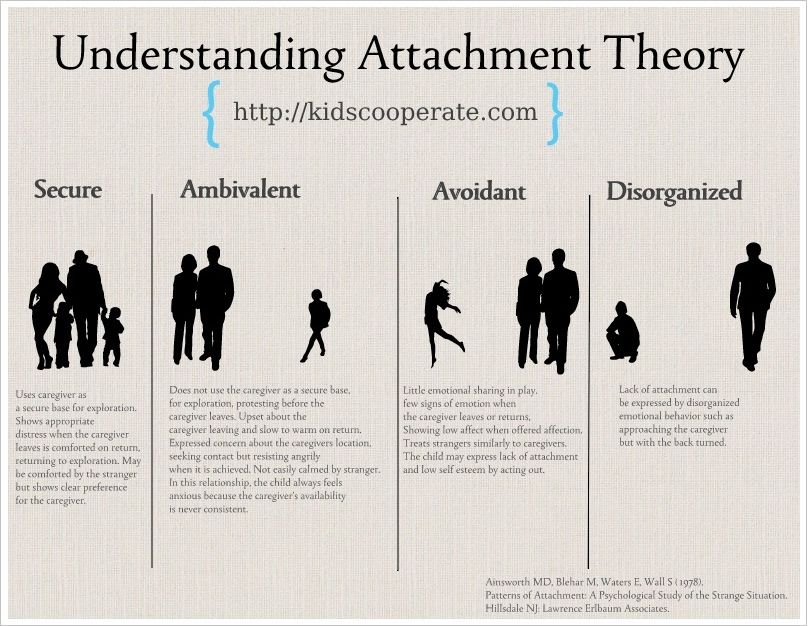

Other aspects of parent thinking include the ability to take the perspective of the child. Mothers who recognize what is distressing for their children have children who are better able to cope with their own distress11 and parents who can accurately identify their children’s thoughts and feelings during conflicts are better able to achieve satisfactory outcomes for those conflicts.12 “Mind-mindedness,” the ability of parents to think of children as having mental states as well as being accurate in their assessment of these mental states, has been linked to children’s secure attachment,13 with a positive link between mothers who describe their children using positive mental descriptors and mothers’ sensitivity.14

Mothers who recognize what is distressing for their children have children who are better able to cope with their own distress11 and parents who can accurately identify their children’s thoughts and feelings during conflicts are better able to achieve satisfactory outcomes for those conflicts.12 “Mind-mindedness,” the ability of parents to think of children as having mental states as well as being accurate in their assessment of these mental states, has been linked to children’s secure attachment,13 with a positive link between mothers who describe their children using positive mental descriptors and mothers’ sensitivity.14

Research Gaps

Little has been done to see how fathers’ cognitions and attitudes affect child development. There has been some investigation of how mothers and fathers differ in their parental cognitions and parenting style: Mothers report higher endorsement of progressive parenting attitudes, encouraging their children to think and verbalize their own ideas and opinions, whereas fathers endorse a more authoritarian approach. 15 What is unknown is the extent to which these differences in attitudes affect child outcomes. Another gap has to do with the direction of effect between parent and child, that is, how children affect their parents’ cognitions and attitudes.

15 What is unknown is the extent to which these differences in attitudes affect child outcomes. Another gap has to do with the direction of effect between parent and child, that is, how children affect their parents’ cognitions and attitudes.

Conclusions

The study of parent cognitions, beliefs, thoughts, and feelings can expand our knowledge of child development. Child-rearing cognitions influence parents to act either positively or negatively towards their children. These beliefs have been considered good predictors of parenting behaviour because they indicate the emotional climate in which children and parents operate and the health of the relationship. In sum, parents observe their children through a filter of conscious and unconscious thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes, and these filters direct the way they perceive their children’s actions. When the thoughts are benign, they direct positive actions. When the thoughts are accurate they will usually lead to positive actions. When they are distorted and distressing, however, they distract parents from the task at hand as well as leading to negative emotions and attributions that ultimately impair effective parenting.

When they are distorted and distressing, however, they distract parents from the task at hand as well as leading to negative emotions and attributions that ultimately impair effective parenting.

Implications for Policy and Services

Most intervention programs for parents involve teaching effective strategies for managing children’s behaviour. But problems can also arise when parents engage in maladaptive thinking. Mothers at a higher risk of child abuse, for example, are more likely to attribute negative traits to children who demonstrate ambiguous behaviour, and see this behaviour as intentional.16 Bugental and her colleagues have administered a cognitive retraining intervention program for parents which aims to alter such biases. They found that mothers who participated in the program showed improvement in parenting cognitions, diminished levels of harsh parenting, and greater emotional availability. In turn, children, two years after their mothers participated in the program, displayed lower levels of aggressive behaviour as well as better cognitive skills than those whose mothers had not undergone such cognitive retraining. 17,18,19 These findings, then, clearly underline the important role played by parental beliefs in the child-rearing process.

17,18,19 These findings, then, clearly underline the important role played by parental beliefs in the child-rearing process.

References

- Holden GW, Buck MJ. Parental attitudes toward childrearing. In: Bornstein MH, ed. Handbook of Parenting. Volume 3: Being and Becoming a Parent. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002:537-562.

- Kuczynski L, ed. Handbook of dynamics in parent child relations. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2003.

- Chen X, Fu R, Zhao S. Culture and socialization. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, Eds. Handbook of Socialization. New York: Guilford Press; 2014:451-472.

- Rothbaum F, Trommsdorff G. Do roots and wings complement or oppose one another? The socialization of relatedness and autonomy in cultural context. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, Eds. Handbook of Socialization. New York: Guilford Press; 2007:461-489.

- Kerr M, Stattin H, Özdemir M. Perceived parenting style and adolescent adjustment: Revisiting directions of effects and the role of parental knowledge.

Dev Psychol. 2012;48:1540-1553.

Dev Psychol. 2012;48:1540-1553. - Bugental DB, Brown M, Reiss C. Cognitive representations of power in caregiving relationships: Biasing effects on interpersonal interaction and information processing. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10:397-407.

- Bugental DB, Lyon JE, Lin EK, McGrath EP, Bimbela A. Children “tune out” in response to ambiguous communication style of powerless adults. Child Dev. 1999;70:214-230.

- Bugental DB, Happaney K. Parental attributions. In: Bornstein MH, ed. Handbook of parenting. Volume 3: Being and becoming a parent. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002:509-535.

- Teti DM, Gelfand DM. Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: The mediational role of maternal self-efficacy. Child Dev. 1991;62:918-929.

- Landry R, Whipple N, Mageau G, et al. Trust in organismic development, autonomy support and adaptation among mothers and their children. Motiv Emotion.

2008;32:173-188.

2008;32:173-188. - Vinik J, Almas A, Grusec JE. Mothers’ knowledge of what distresses and what comforts their children predicts children’s coping, empathy, and prosocial behavior. Parent Sci Pract. 2011;11:56-71.

- Hastings P, Grusec JE. Conflict outcome as a function of parental accuracy in perceiving child cognitions and affect. Soc Dev 1997;6:76-90.

- Bernier A, Dozier M. Bridging the attachment transmission gap: The role of maternal mind-mindedness. Int J of Behav Dev. 2003;27:355-365.

- McMahon CA, Meins E. Mind-mindedness, parenting stress, and emotional availability in mothers of preschoolers. Early Child Res Q. 2012;27:245-252.

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Lansford JE. Parenting attributions and attitudes in cross-cultural perspective. Parent Sci Pract. 2011;11:214-237.

- McCarthy R, Crouch J, Skowvonski, et al. Child physical abuse risk moderates spontaneously inferred traits from ambiguous child behaviors.

Child Abuse Neglect. 2013;37:1142-1151.

- Bugental DB, Ellerson PC, Lin EK, Rainey B, Kokotovic A, & O'Hara N. A cognitive approach to child abuse prevention. Psychol Violence. 2010;1: 84-106.

- Bugental DB, Corpuz R, Schwartz A. Parenting children’s aggression: Outcomes of an early intervention. Devel Psychol. 2012;48:1443-1449.

- Bugental DB, Schwartz A, Lynch C. Effects of an early family intervention on children's memory: The mediating effects of cortisol levels. Mind, Brain, Educ. 2010;4:159-170.

How to cite this article:

Grusec JE, Danyliuk T. Parents’ Attitudes and Beliefs: Their Impact on Children’s Development. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. Tremblay RE, topic ed. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/parenting-skills/according-experts/parents-attitudes-and-beliefs-their-impact-childrens-development. Updated: December 2014. Accessed November 30, 2022.

Updated: December 2014. Accessed November 30, 2022.

Text copied to the clipboard ✓

Genetics or upbringing? Neuropsychologist on how the "family factor" affects the development of a child

Psychology

Genetics or upbringing? Neuropsychologist on how the "family factor" affects the development of the child

January 22, 2021 3 370 views

Irina Matanova, neuropsychologist of the project "Children ready for the future"

Irina Matanova, neuropsychologist of the project "Children Ready for the Future" (@deti_ready), answers the question, what has a greater influence on a child's development - heredity or upbringing?

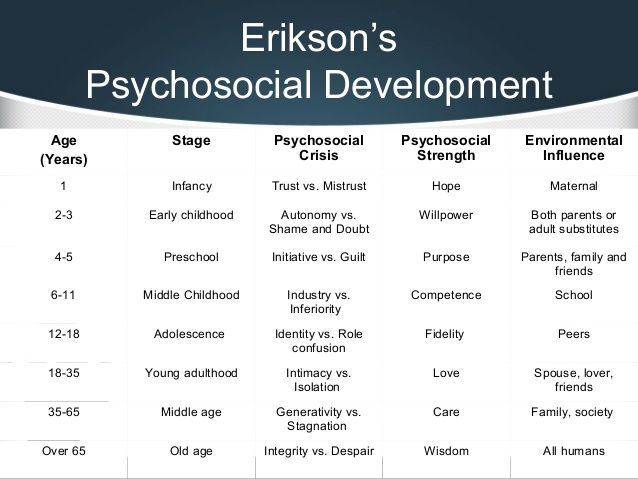

It is believed that development depends mainly on three factors - this is heredity, individual refraction of qualities transmitted by genes, and the influence of environmental conditions. Consider the extent to which these factors affect the formation of personality.

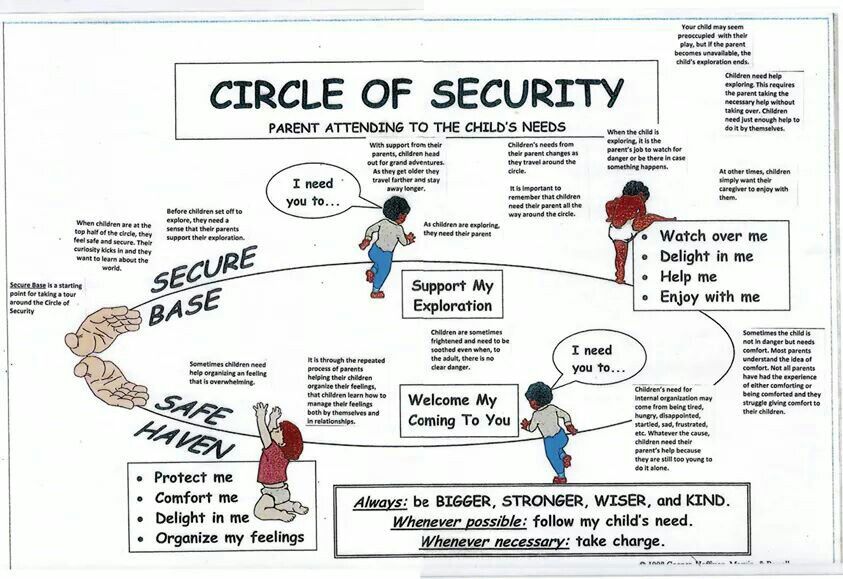

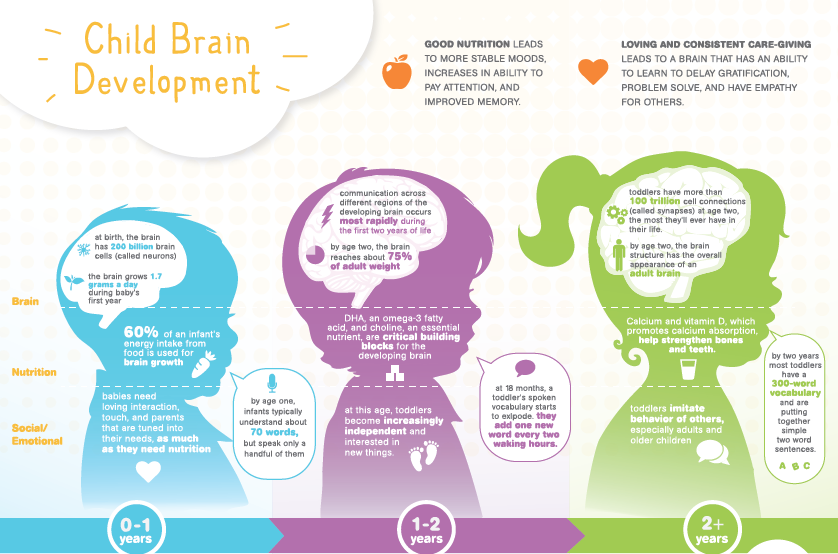

It has long been proven that intelligence is highly dependent on genetics. However, studies have emerged that have shown the importance of emotional relationships and attachment in the development of children's intelligence.

For infants and young children, this factor can be decisive.

In the absence of a healthy parent-child relationship, emotional neglect can cause severe intellectual decline in children despite normal care.

It is important that certain processes take place simultaneously during maturation: the maturation of the nervous system must be “superimposed” on the positive experience of emotional relationships with close relatives.

The personality of the child, his temperament, innate characteristics of patience, endurance, sensitivity, the ability to withstand unpleasant experiences - all this affects how the child will develop. And just as important is the context of family relationships in which the child grows up, the experience of trauma and deprivation.

The child's behavior and development is influenced by internal conflicts, fears, and aggression. Often, because of them, the development of the child is inhibited, and there may be a delay in development. Worries about conflicts in the family, divorce of parents, illnesses of loved ones can exhaust the child so much that there is simply no strength left for cognitive activity.

Let's get back to genetic factors. Today, it is known that genetic information inside the cell and its implementation are influenced by non-genetic factors. For example, environmental factors, the emotional state of the mother during pregnancy (this can also affect the genetic information of the child through hormones and communication with him).

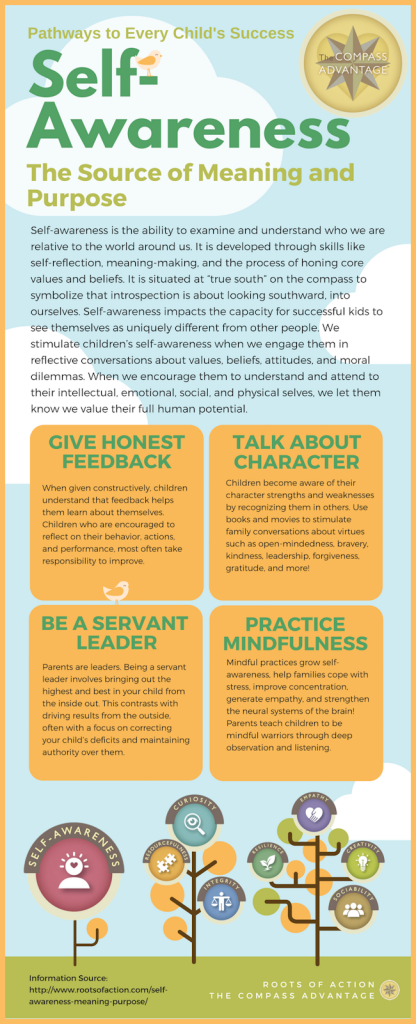

Much in the development of a child depends on the reaction of the close environment. If adults accept certain characteristics of the child, he has the opportunity to significantly develop his abilities. In other words, parents can both provide a resource for development and undermine the child's self-confidence.

For example, a child has poor eyesight and must wear glasses. If you constantly worry and talk about the problem, then you can "infect" the baby with self-doubt. And you can support with the words: “It looks like you look like dad ( or mother, depending on who also has visual difficulties ), but you have a keen ear and musical abilities. In any situation, you can find supportive words and resources that can strengthen self-confidence and make the child feel that he is not alone.

Parental support of the interests and natural inclinations of the child has the same supporting and developing potential. Many other things also influence: the personal maturity of the parents, the socio-economic factor, the parenting strategies adopted in the family, and even the success of the parents in the profession.

Heredity is certainly important. But this is something that we cannot influence in any way. But other factors - the style of upbringing, the atmosphere in the family, and so on - already depend on us adults. We can help children become happy, find their place and harmony in the family and society, love and work, so that children are ready for the future!

We can help children become happy, find their place and harmony in the family and society, love and work, so that children are ready for the future!

Post cover: unsplash.com

Family influence on child development

It would seem obvious that family and social education directly affects the formation and development of the child. But often we do not pay much attention to this, making a big mistake. The family has a special place in the life of every person. The child grows up in it, and from the first years of his life he learns the norms of human relations, absorbing both good and evil from the family, everything that is characteristic of his family. Having matured, children repeat in their family everything that was in the family of their parents.

One of the main conditions is that the family provides a sense of security, which provides him with security when interacting with the outside world. Children gain confidence in their abilities, fear and excitement go away.

Parenting patterns also play an important role. Children often copy the behavior of other people, especially those who are in close contact with them. Partly it is a conscious attempt to behave in the same way as others behave, partly it is an unconscious imitation, which is one aspect of identification with another.

The family plays an important role in the child's life experiences. The extent to which parents provide the child with the opportunity to study in libraries, visit museums, and relax in nature depends on the stock of children's knowledge. It is also very important to talk a lot with children. Those children who have more life experience will be better than other children to adapt to the new environment and respond positively to the changes taking place around them.

Thus, it can be argued that the positive attitude of parents to the cognitive development of the child, support for his cognitive and creative activity, encouragement of cognitive activity and recognition of the success of the child helps to develop their intellectual and creative abilities.

The family is an important factor in the formation of discipline and behavior in the child. Parents influence the child's behavior by encouraging or condemning certain types of behavior, as well as applying punishments or allowing a degree of freedom in behavior that is acceptable to them. The child learns from his parents what he should do, how to behave.

Communication in the family affects the formation of a child's worldview, which allows him to develop his own norms, views, ideas. The development of the child will depend on how good conditions for communication are provided to him in the family; development also depends on the clarity and clarity of communication in the family.

For a child, a family is a talisman, a pantry of knowledge and a springboard to adulthood. It is in the family that the child receives the basics of knowledge about the world around him, and with the high cultural and educational potential of his parents, he continues to receive not only the basics, but also the culture itself all his life. Family is a certain moral and psychological climate, for a child it is the first school of relations with people.

Family is a certain moral and psychological climate, for a child it is the first school of relations with people.

Family education has a wide time range of influence: it lasts a person’s entire life, occurs at any time of the day, at any time of the year.

Also, the family can be fraught with certain difficulties, contradictions and shortcomings of educational influence. The most widespread negative factors of family upbringing, which have to be taken into account in the educational process, are: spoiledness and effeminacy, immorality and illegality of the family economy;

• lack of spirituality of parents, lack of striving for the spiritual development of children;

• authoritarianism or "liberalism", impunity and forgiveness;

• immorality, immoral style and tone of family relations;

• absence of a normal psychological climate in the family;

• fanaticism in any of its manifestations;

• pedagogical illiteracy;

• illegal behavior of adults.

Based on the specifics of the family as a personal environment for the development of the child's personality, a system of principles of family education should be built:

• children should grow up and be brought up in an atmosphere of goodwill, love and happiness;

• parents must understand and accept their child for who he is and contribute to the development of the best in him;

• educational influences should be built taking into account age, gender and individual characteristics;

• the dialectical unity of sincere, deep respect for the individual and high demands on him should be the basis of family education;

• the personality of the parents themselves is an ideal model for children to imitate;

• upbringing should be based on the positive in a growing person;

• all activities organized in the family for the development of the child must be based on the game;

• optimism is the basis of the style and tone of communication with children in the family.