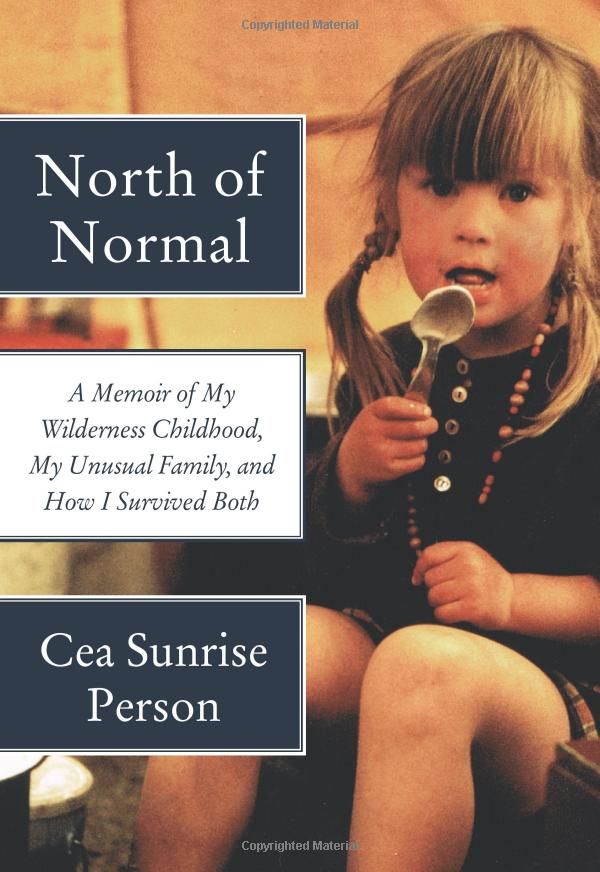

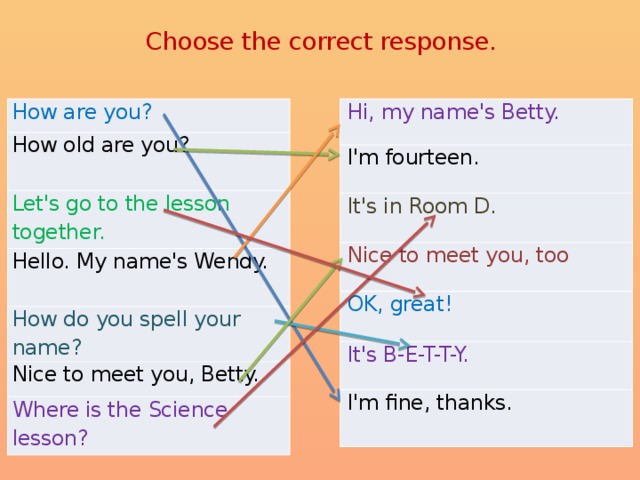

How old is genie the wild child now

Starved, tortured, forgotten: Genie, the feral child who left a mark on researchers | Children

She hobbled into a Los Angeles county welfare office in October 1970, a stooped, withered waif with a curious way of holding up her hands, like a rabbit. She looked about six or seven. Her mother, stricken with cataracts, was seeking an office with services for the blind and had entered the wrong room.

But the girl transfixed welfare officers.

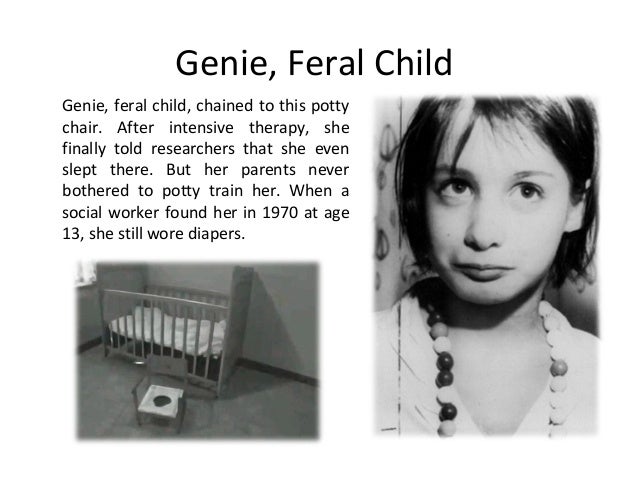

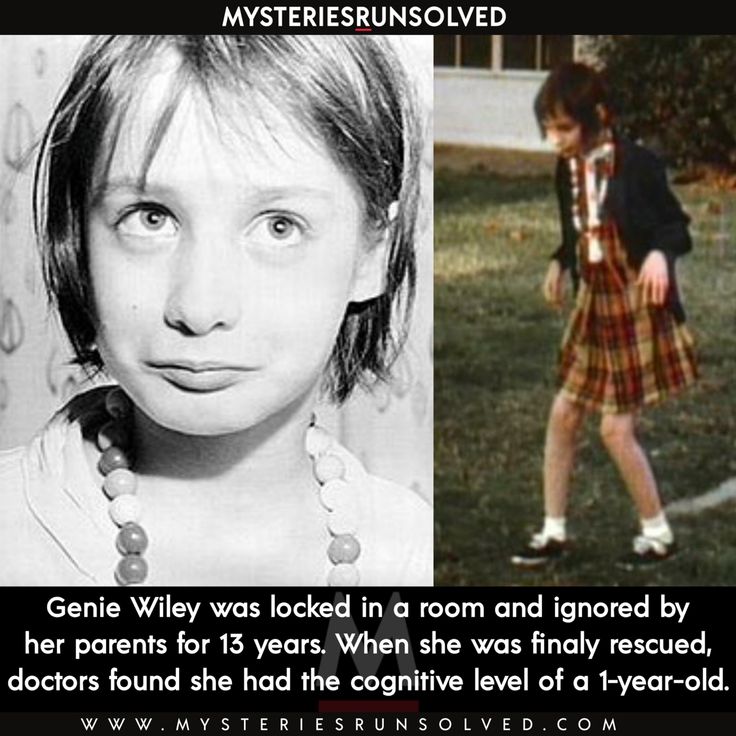

At first they assumed autism. Then they discovered she could not talk. She was incontinent and salivated and spat. She had two nearly complete sets of teeth - extra teeth in such cases are known as supernumeraries, a rare dental condition. She could barely chew or swallow, and could not fully focus her eyes or extend her limbs. She weighed just 59lb (26kg). And she was, it turned out, 13 years old.

Her name – the name given to protect her identity – was Genie. Her deranged father had strapped her into a handmade straitjacket and tied her to a chair in a silent room of a suburban house since she was a toddler. He had forbidden her to cry, speak or make noise and had beaten and growled at her, like a dog.

It made news as one of the US’s worst cases of child abuse. How, asked Walter Cronkite, could a quiet residential street, Golden West Avenue, in Temple City, a sleepy Californian town, produce a feral child – a child so bereft of human touch she evoked cases like the wolf child of Hesse in the 14th century, the bear child of Lithuania in 1661 and Victor of Aveyron, a boy reared in the forests of revolutionary France?

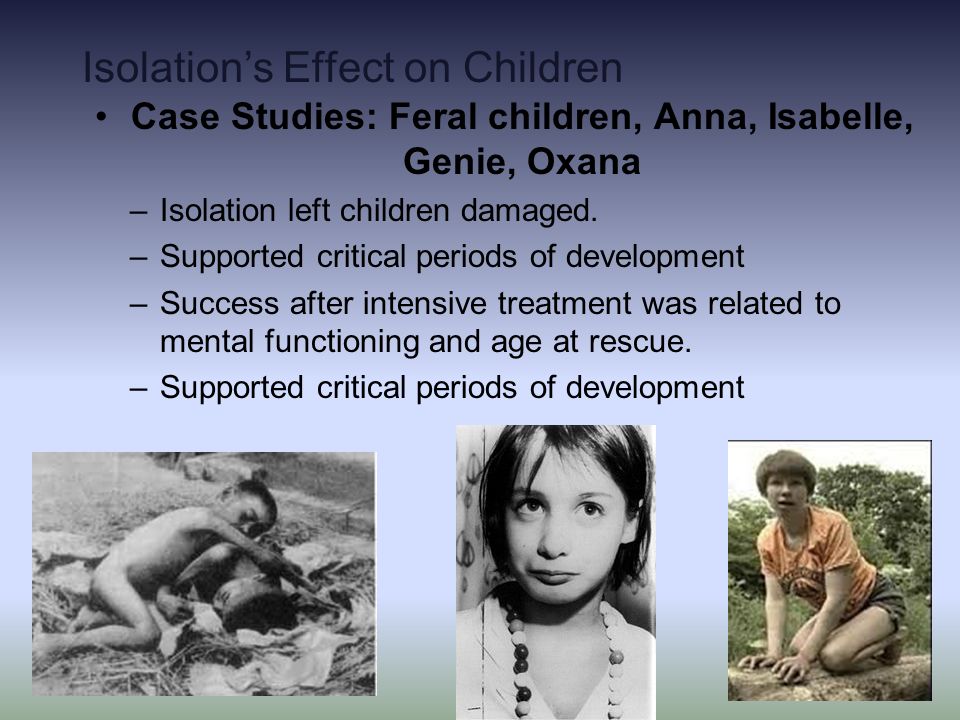

Over time, Genie slipped from headlines – Vietnam was burning, the Beatles were in the midst of breaking up – but she retained the attention of scientists, especially linguists. She was a prize specimen for having grown up without language or social training. Could she now learn language?

Jostling for access, they took brain scans and audio recordings, performed countless tests, compiled reams of data, published papers. And gradually they, too, with a few exceptions, also lost interest.

By the late 1970s, Genie had vanished back into obscurity. As she was a ward of California, authorities housed her in state-run institutions, her location secret. Four decades later, she apparently remains in state care.

“I’m pretty sure she’s still alive because I’ve asked each time I called and they told me she’s well,” said Susan Curtiss, a UCLA linguistics professor who studied and befriended Genie. “They never let me have any contact with her. I’ve become powerless in my attempts to visit her or write to her. I think my last contact was in the early 1980s.”

Authorities rebuffed Guardian inquiries. “If ‘Genie’ is alive, information relating to her is confidential and it does not meet the criteria of information that is available through a PRA Request,” said Kim Tsuchida, a public records act coordinator for California’s department of social services. “We would suggest that you contact Los Angeles County with your request.” LA County referred the query to mental health authorities, who did not respond to a written request.

With Genie approaching her 60th birthday, her fate remains an enigma. Has she learned to speak? To engage with the world? To be happy? Only a handful of people know.

But the story has an additional chapter: the fate of the other players. Almost all, it turns out, were scarred. Scarred psychologically and professionally in ways none anticipated, and which in some cases endure to this day.

There were the scientists and carers who studied and, in some cases, loved her. Their collaboration collapsed into feuds, vendettas and muck-raking.

There was the author who chronicled the saga and found it taking over his life. He moved to Paris to escape only for Genie’s story to follow him and manifest itself in other ways.

There was Genie’s older brother, who also suffered grievously under their father. He lived, in his own words, like a “dead man” and failed his own daughter – Genie’s niece – who in turn failed her daughters.

The story begins with Genie’s father, Clark Wiley. He grew up in foster homes in the Pacific north-west and worked as a machinist on aircraft assembly lines in LA during and after the second world war. He married Irene Oglesby, a dust bowl migrant 20 years his junior. A controlling man who hated noise, he did not want children. Yet children came. The first, a baby girl, died after being left in a cold garage. A second died from birth complications. A third, a boy named John, survived, followed five years later by the girl who would become known as Genie.

When a drunk driver killed Wiley’s mother in 1958, he unravelled into anger and paranoia. He brutalised John and locked his 20-month-old daughter alone in a small bedroom, isolated and barely able to move. When not harnessed to a potty seat, she was constrained in a type of straitjacket and wire mesh-covered crib. Wiley imposed silence with his fists and a piece of wood. That is how Genie passed the 1960s.

Irene, stricken by fear and poor eyesight, finally fled in 1970. Things happened swiftly after she blundered into the wrong welfare office. Wiley, charged with child abuse, shot himself. “The world will never understand,” said the note.

Things happened swiftly after she blundered into the wrong welfare office. Wiley, charged with child abuse, shot himself. “The world will never understand,” said the note.

Genie, a ward of court, was moved to LA’s children’s hospital. Pediatricians, psychologists, linguists and other experts from around the US petitioned to examine and treat her, for here was a unique opportunity to study brain and speech development – how language makes us human.

Genie could speak a few words, such as “blue”, “orange”, “mother” and “go”, but mostly remained silent and undemonstrative. She shuffled with a sort of bunny hop and urinated and defecated when stressed. Doctors called her the most profoundly damaged child they had ever seen.

Progress initially was promising. Genie learned to play, chew, dress herself and enjoy music. She expanded her vocabulary and sketched pictures to communicate what words could not. She performed well on intelligence tests.

“Language and thought are distinct from each other. For many of us, our thoughts are verbally encoded. For Genie, her thoughts were virtually never verbally encoded, but there are many ways to think,” said Curtiss, one of the few surviving members of the research team. “She was smart. She could hold a set of pictures so they told a story. She could create all sorts of complex structures from sticks. She had other signs of intelligence. The lights were on.”

For many of us, our thoughts are verbally encoded. For Genie, her thoughts were virtually never verbally encoded, but there are many ways to think,” said Curtiss, one of the few surviving members of the research team. “She was smart. She could hold a set of pictures so they told a story. She could create all sorts of complex structures from sticks. She had other signs of intelligence. The lights were on.”

Curtiss, who was starting out as an academic at that time, formed a tight bond with Genie during walks and shopping trips (mainly for plastic buckets, which Genie collected). Her curiosity and spirit also enchanted hospital cooks, orderlies and other staff members.

Genie showed that lexicon seemed to have no age limit. But grammar, forming words into sentences, proved beyond her, bolstering the view that beyond a certain age, it is simply too late. The window seems to close, said Curtiss, between five and 10.

“Does language make us human? That’s a tough question,” said the linguist. “It’s possible to know very little language and still be fully human, to love, form relationships and engage with the world. Genie definitely engaged with the world. She could draw in ways you would know exactly what she was communicating.”

“It’s possible to know very little language and still be fully human, to love, form relationships and engage with the world. Genie definitely engaged with the world. She could draw in ways you would know exactly what she was communicating.”

Yet there was to be no Helen Keller-style breakthrough. On the contrary, by 1972, feuding divided the carers and scientists. Jean Butler, a rehabilitation teacher, clashed with researchers and enlisted Irene, Genie’s mother, in a campaign for control. Each side accused the other of exploitation.

Genie Wiley with a doctor. Photograph: Nova: Secret of the Wild ChildResearch funding dried up and Genie was moved to an inadequate foster home. Irene briefly regained custody only to find herself overwhelmed – so Genie went to another foster home, then a series of state institutions under the supervision of social workers who barred access to Curtiss and others. Genie’s progress swiftly reversed, perhaps never to be recovered.

Russ Rymer, a journalist who detailed the case in the 1990s in two New Yorker articles and a book, Genie: a Scientific Tragedy, painted a bleak portrait of photographs from her 27th birthday party.

“A large, bumbling woman with a facial expression of cowlike incomprehension … her eyes focus poorly on the cake. Her dark hair has been hacked off raggedly at the top of her forehead, giving her the aspect of an asylum inmate.”

Jay Shurley, a professor of psychiatry and behavioural science who was at that party, and her 29th, told Rymer she was miserable, stooped and seldom made eye contact. “It was heartrending.”

A veil cloaks Genie’s life since then. But a melancholy thread connects those she left behind.

For the surviving scientists it is regret tinged with anguish. Shurley’s verdict: “She was this isolated person, incarcerated for all those years, and she emerged and lived in a more reasonable world for a while, and responded to this world, and then the door was shut and she withdrew again and her soul was sick.”

Clark Wiley, 70, and his son John leave a police station after the father was booked for investigation of child abuse in 1970. Photograph: APCurtiss, who wrote a book about Genie, and is one of the few researchers to emerge creditably from the saga, feels grief-stricken to this day. “I’m not in touch with her, but not by my choice. They never let me have any contact with her. I’ve become powerless in my attempts to visit her or write to her. I long to see her. There is a hole in my heart and soul from not being able to see her that doesn’t go away.”

“I’m not in touch with her, but not by my choice. They never let me have any contact with her. I’ve become powerless in my attempts to visit her or write to her. I long to see her. There is a hole in my heart and soul from not being able to see her that doesn’t go away.”

In an interview, Rymer said Genie’s story affected all those involved, himself included. “It made for a pretty intense and disturbing several years. This took over my life, my worldview. A lot about this case left me shaken. Maybe this is cowardice – I was relieved to be able to turn away from the story. Because anytime I went into that room [where Genie grew up], it was unbearable.”

But Rymer discovered he could not turn away, not fully. “I generally go on to another story. But I had to confront how much I identified with Genie. Being shut up, unable to express herself, I think that speaks to everyone. I think the person I was writing about was to some extent myself.”

Genie infiltrated his recent novel, Paris Twilight, set in France in 1990, said Rymer. “The novel details, as the Genie tale does more literally, an attempted escape from a small dank room and a thwarted life, into a palatial future that doesn’t in the end work out. It’s about the connection between science and emotion. So right there I’m still trying to resolve some of these issues. [In my experience] as a journalist, Genie, in ways I could never anticipate, brought up issues that will never release me.”

“The novel details, as the Genie tale does more literally, an attempted escape from a small dank room and a thwarted life, into a palatial future that doesn’t in the end work out. It’s about the connection between science and emotion. So right there I’m still trying to resolve some of these issues. [In my experience] as a journalist, Genie, in ways I could never anticipate, brought up issues that will never release me.”

The legacy of Clark Wiley’s abuse never released Genie’s brother, John. After the beatings, and witnessing his sister’s suffering, he told ABC News in 2008: “I feel at times God failed me. Maybe I failed him.” He saw Genie for the last time in 1982 and lost touch with their mother, who died in 2003. “I tried to put [Genie] out of my mind because of the shame. But I’m glad she got some help.”

After brushes with the law, John settled in Ohio and worked as a housepainter. He married and had a daughter, Pamela. But the marriage crumbled and his daughter – Genie’s niece – turned to drugs.

In 2010, police found Pamela intoxicated and charged her with endangering her two daughters, Genie’s grandnieces. There would be no miracle turnaround, no happy ending. John, who had diabetes, died in 2011. Pamela, who apparently never met her aunt Genie, died in 2012.

In Arab folklore, a genie is a spirit imprisoned in a bottle or oil lamp who, when freed, can grant wishes. The waif who shuffled into the world in 1970 enchanted many people in that brief, heady period after her liberation.

But granting wishes, like so much else, proved beyond her, perhaps because she never truly escaped.

The Tragic Story Of Genie Wiley, The Feral Child Of 1970s California

By Andrew Milne | Checked By John Kuroski

Published October 31, 2021

Updated July 25, 2022

"Feral Child" Genie Wiley was strapped to a chair by her parents and neglected for 13 years, giving researchers a rare chance to study human development.

The story of Genie Wiley the Feral Child sounds like the stuff of fairytales: An unwanted, mistreated child survives brutal imprisonment at the hands of a savage ogre and is rediscovered and reintroduced to the world in an impossibly youthful state. Unfortunately for Wiley, hers is a dark, real-life tale with no happy ending. There would be no fairy godmothers, no magic solutions, and no enchanted transformations.

Unfortunately for Wiley, hers is a dark, real-life tale with no happy ending. There would be no fairy godmothers, no magic solutions, and no enchanted transformations.

Getty ImagesFor the first 13 years of her life, Genie Wiley suffered unimaginable abuse and neglect at the hands of her parents.

Genie Wiley was separated from any form of socialization and society for the first 13 years of her life. Her intensely abusive father and helpless mother so neglected Wiley that she hadn’t learned to speak and her growth was so stunted that she looked like she was no more than eight years old.

Her intense trauma proved something of a godsend to scientists of various fields including psychology and linguistics, though they were later accused of exploiting the child for their research on learning and development. But Genie Wiley’s case did beg the question: What does it mean to be human?

Listen above to the History Uncovered podcast, episode 36: Genie Wiley, also available on Apple and Spotify.

The Horrifying Upbringing That Turned Genie Wiley Into A “Feral Child”

Genie isn’t the Feral Child’s real name. She was given the name to protect her identity once she became a spectacle of scientific research and awe.

ApolloEight Genesis/YouTubeThe home in which Genie Wiley was raised by her abusive parents.

Susan Wiley was born in 1957 to Clark Wiley and his much-younger wife Irene Oglesby. Oglesby was a Dust Bowl refugee who had drifted to the Los Angeles area where she met her husband. He was a former assembly-line machinist raised in and out of brothels by his mother. This childhood had a profound effect on Clark, as for the rest of his life he’d fixate on the figure of his mother.

Clark Wiley never wanted children. He hated the noise and stress they brought along. Nonetheless, the first baby girl did come along and Wiley left the child in the garage to freeze to death when she wouldn’t be quiet.

The Wiley’s second baby died of a congenital defect, and then came along Genie Wiley and her brother John. While her brother also faced their father’s abuse, it was nothing compared to Susan’s suffering.

While her brother also faced their father’s abuse, it was nothing compared to Susan’s suffering.

Though he was always a bit off, the death of Clark Wiley’s mother by a drunk driver in 1958 seemed to undo him completely. The end to the complicated relationship they shared fanned his cruelty into a bonfire.

ApolloEight Genesis/YouTubeGenie Wiley’s mother was legally blind, which was supposedly the reason why she felt she couldn’t intervene on her daughter’s behalf during the abuse.

Clark Wiley decided that his daughter was mentally disabled and that she’d be useless to society. Thus, he banished society from her. No one was allowed to interact with the girl who was mostly locked in a blacked-out room or in a makeshift cage. He kept her strapped into a toddler toilet as a sort of straight-jacket, and she wasn’t potty-trained.

Clark Wiley would hit her with a large plank of wood for any infraction. He’d growl outside her door like a deranged guard dog, instilling a lifelong fear of clawed animals in the girl. Some experts believe sexual abuse may have been involved, due to Wiley’s later sexually inappropriate behavior, particularly involving older men.

Some experts believe sexual abuse may have been involved, due to Wiley’s later sexually inappropriate behavior, particularly involving older men.

In her own words, Genie Wiley, the Feral Child recalled:

“Father hit arm. Big wood. Genie cry… Not spit. Father. Hit face — spit. Father hit big stick. Father is angry. Father hit Genie big stick. Father take piece wood hit. Cry. Father make me cry.”

She had spent 13 years living this way.

Genie Wiley’s Salvation From Torment

Genie Wiley’s mother was nearly blind which she later said kept her from interceding on her daughter’s behalf. But one day, 14 years after Genie Wiley’s first introduction to her father’s cruelty, her mother did finally muster her courage and leave.

In 1970, she stumbled into social services, mistaking it for the office where they’d give aid to the blind. The office workers’ antennae were immediately raised when they noticed the young girl acting so strangely, hopping like a bunny instead of walking.

Genie Wiley was then nearly 14 but she looked no more than eight.

Associated PressClark Wiley (center left) and John Wiley (center right) after the abuse scandal broke open.

An abuse case was immediately opened against both parents, but Clark Wiley would kill himself shortly before trial. He left behind a note which read: “The world will never understand.”

Wiley became a ward of the state. She knew but a few words when she entered UCLA’s Children’s Hospital and was dubbed by medical professionals there as “the most profoundly damaged child they had ever seen.”

A 2003 TLC Documentary on Genie Wiley’s experience.

Wiley’s case soon enchanted scientists and physicians who applied for and were rewarded a grant by the National Institute of Mental Health to study her. The team explored the “Developmental Consequence of Extreme Social Isolation” for four years from 1971 to 1975.

The team explored the “Developmental Consequence of Extreme Social Isolation” for four years from 1971 to 1975.

For those four years, Wiley became the center of these scientists’ lives. “She wasn’t socialized, and her behavior was distasteful,” began Susie Curtiss, a linguist intimately involved in the feral child study, “but she just captivated us with her beauty.”

But also for those four years, Wiley’s case tested the ethics of a relationship between a subject and their researcher. Wiley would come to live with many of the team members who observed her which was not only a huge conflict of interest but also potentially begat another abusive relationship in her life.

Researchers Begin Experimenting On The “Feral Child”

ApolloEight Genesis/YouTubeFor four years, Genie the Feral Child was subject to scientific experimentation that some felt was too intense to be ethical.

Genie Wiley’s discovery timed precisely with an uptick in the scientific study of language. To language scientists, Wiley was a blank slate, a way to understand what part language has in our development and vice versa. In a twist of dramatic irony, Genie Wiley now became deeply wanted.

To language scientists, Wiley was a blank slate, a way to understand what part language has in our development and vice versa. In a twist of dramatic irony, Genie Wiley now became deeply wanted.

One of the foremost tasks of the “Genie Team” was to establish which came first: Wiley’s abuse or her lapse in development. Did Wiley’s developmental delay come as a symptom of her abuse, or was Wiley born challenged?

Up until the late 1960s, it was largely believed by linguists that children could not learn language after puberty. But Genie the Feral Child disproved this. She had a thirst for learning and curiosity and her researchers found her “highly communicative.” It turned out that Wiley could learn language, but grammar and sentence structure was another thing entirely.

“She was smart,” Curtiss said. “She could hold a set of pictures so they told a story. She could create all sorts of complex structures from sticks. She had other signs of intelligence. The lights were on. ”

”

Wiley showed that grammar becomes inexplicable to children without training between five and 10, but communication and language remains entirely attainable. Wiley’s case also posed some more existential questions about the human experience.

“Does language make us human? That’s a tough question,” said Curtiss. “It’s possible to know very little language and still be fully human, to love, form relationships and engage with the world. Genie definitely engaged with the world. She could draw in ways you would know exactly what she was communicating.”

TLCSusan Curtiss, a UCLA linguistics professor, helps Genie the Feral Child to find her voice.

As such, Wiley could construct simple phrases to convey what she wanted or was thinking, like “applesauce buy store,” but the nuances of a more sophisticated sentence structure were out of her grasp. This demonstrated that language is different from thought.

Curtiss explained that “For many of us, our thoughts are verbally encoded. For Genie, her thoughts were virtually never verbally encoded, but there are many ways to think.”

For Genie, her thoughts were virtually never verbally encoded, but there are many ways to think.”

Genie the Feral Child’s case did help to establish that there is a point beyond which total language fluency is impossible if the subject does not already speak one language fluently.

According to Psychology Today:

“The case of Genie confirms that there is a certain window of opportunity that sets the limit for when you can become relatively fluent in a language. Of course, if you already are fluent in another language, the brain is already primed for language acquisition and you may well succeed in becoming fluent in a second or third language. If you have no experience with grammar, however, Broca’s area remains relatively hard to change: you cannot learn grammatical language production later on in life.”

Conflicts Of Interest And Exploitation

Wiley’s walk was described as a ‘bunny hop’.

For all their contributions to understanding human nature, the “Genie Team” was not without its critics. For one thing, each of the scientists on the team accused each other of abusing their position and relationships with Genie the feral child.

For instance, in 1971, language teacher Jean Butler obtained permission to bring Wiley home with her for socialization purposes. Butler was able to contribute some integral insights on Wiley in this environment, including the feral child’s fascination with collecting buckets and other containers that stored liquid, a common trait amongst other children who have faced extreme isolation. She also saw that Genie Wiley was beginning puberty at this time, a sign that her health was strengthening.

The arrangement went along well enough for a time until Butler claimed she caught Rubella and would need to quarantine herself and Wiley. Their temporary situation turned more permanent. Butler turned away the other physicians on the “Genie Team” claiming that they were subjecting her to too much scrutiny. She applied for the foster care of Wiley as well.

She applied for the foster care of Wiley as well.

Later, Butler was accused by other members of the team of exploiting Wiley. They said Butler believed her young ward would make her “the next Anne Sullivan,” the teacher who helped Helen Keller to become more than invalid.

As such, Genie Wiley later went to live with the family of therapist David Rigler, another member of the “Genie Team.” As far as Genie Wiley’s luck would allow, this seemed to be a good fit for her and a time to develop and discover the world with people who genuinely cared for her well-being.

The arrangement also gave the “Genie Team” more access to her. As Curtiss later wrote in her book Genie: A Psycholinguistic Study of a Modern-Day Wild Child:

“One particularly striking memory of those early months was an absolutely wonderful man who was a butcher, and he never asked her name, he never asked anything about her. They just connected and communicated somehow. And every time we came in — and I know this was so with others, as well — He would slide open the little window and hand her something that wasn’t wrapped, a bone of some sort, some meat, fish, whatever.

And he would allow her to do her thing with it, and to do her thing, what her thing was, basically, was to explore it tactilely, to put it up against her lips and feel it with her lips and touch it, almost as if she were blind.”

Wiley remained an expert in non-verbal communication and had a way of expressing her thoughts to people even if she couldn’t speak to them.

Rigler, too, recalled how one time a father and his young son carrying a fire engine passed by Wiley. “And they just passed,” Rigler remembered. “And then they turned around and came back, and the boy, without a word, handed the fire engine to Genie. She never asked for it. She never said a word. She did this kind of thing, somehow, to people.”

Despite the progress she displayed at the Riglers’, once the funding ended for the study in 1975, Wiley went to live with her mother for a brief period. In 1979, her mother filed a lawsuit against the hospital and her daughter’s individual caregivers, including the scientists on the “Genie Team,” alleging they exploited Wiley for “prestige and profit. ” The suit was settled in 1984 and Wiley’s contact with her researchers all but entirely severed.

” The suit was settled in 1984 and Wiley’s contact with her researchers all but entirely severed.

Wikimedia CommonsGenie Wiley was returned to foster care after the research on her ended. She regressed in these environments and never regained speech.

Wiley was eventually placed in a number of foster homes, some of which were also abusive. There Wiley was beaten for vomiting and regressed greatly. She never regained the progress she had made.

Genie Wiley Today

Genie Wiley’s present life is little-known; once her mother took custody, she refused to let her daughter be the subject of any more studies. Like so many people with special needs, she fell through the cracks of proper care.

Wiley’s mother died in 2003, her brother John in 2011, and her niece Pamela in 2012. Russ Rymer, a journalist, tried to piece together what led to the dissolution of Wiley’s team, but he found the task challenging as the scientists had all divided on who was exploitative and who had the feral child’s best interests in mind. “The tremendous rift complicated my reporting,” Rymer said. “That was also part of the breakdown that turned her treatment into such a tragedy.”

“The tremendous rift complicated my reporting,” Rymer said. “That was also part of the breakdown that turned her treatment into such a tragedy.”

He later recalled visiting Susan Wiley on her 27th birthday and seeing:

“A large, bumbling woman with a facial expression of cowlike incomprehension… her eyes focus poorly on the cake. Her dark hair has been hacked off raggedly at the top of her forehead, giving her the aspect of an asylum inmate.”

Despite this, Wiley is not forgotten by those that cared about her.

“I’m pretty sure she’s still alive because I’ve asked each time I called and they told me she’s well,” Curtiss said. “They never let me have any contact with her. I’ve become powerless in my attempts to visit her or write to her. I think my last contact was in the early 1980s.”

Curtiss added in a 2008 interview that she has “spent the last 20 years looking for her… I can get as far as the social worker in charge of her case, but I can’t get any farther. ”

”

As of 2008, Wiley was in an assisted living facility in Los Angeles.

Genie the feral child’s story is not a happy one as she drifted from one abusive situation to another, and by all accounts, was denied and failed by society at every step. But, one can hope that wherever she is, she continues to find joy in discovering the still-new world around her, and instills in others the fascination and affection that she had for her researchers.

After this look at Genie Wiley the Feral Child, read about teenage murderer Zachary Davis and Louise Turpin, the woman who kept her children captive for decades.

Milwaukee Protocol against Rabies - Knife

A little about incurable diseases and how humanity is trying to treat them

Infections have always accompanied humans. Some of them, like pneumonia or tuberculosis, have become much less terrible for the average patient over the years, and these are probably the majority: humanity has exterminated - or at least greatly reduced the likelihood of infection - measles, plague, polio and thousands of other diseases. But a smaller part remained - those diseases that, as before, are almost or always fatal. Even in ancient Greece, cancer, syphilis, encephalitis, and rabies were well known. It is about rabies that will be discussed in this article.

But a smaller part remained - those diseases that, as before, are almost or always fatal. Even in ancient Greece, cancer, syphilis, encephalitis, and rabies were well known. It is about rabies that will be discussed in this article.

Rabies is now relatively rare, with about 55,000 deaths worldwide per year. Compared to car accidents or AIDS, 1.25 million and about 2 million, respectively, is almost nothing. But every death is a tragedy, and it is all the more terrible because death from rabies cannot be prevented. Or rather, almost impossible. Is there a cure for this terrible disease? Let's figure it out.

A brief excursion into virology

The rabies virus belongs to the family named after itself - the family of rhabdoviruses (Rhabdoviridae from the ancient Greek rhabdos - "rod", because the virus is similar in shape to an elongated bullet). Like other similar viruses, it is enveloped and has a single-stranded RNA genome.

The virus has flat and rounded ends, which is why it is often compared to a bullet. To protect against the environment, it is covered with a glycoprotein scaffold with specific spikes: for example, glycoprotein G helps the virus to penetrate into the cell - it is to it that the rabies vaccine forms antibodies. In total, there are 7 strains of the rabies virus in the world, but people are most often infected by one - the so-called genotype 1. It is also common in Russia.

To protect against the environment, it is covered with a glycoprotein scaffold with specific spikes: for example, glycoprotein G helps the virus to penetrate into the cell - it is to it that the rabies vaccine forms antibodies. In total, there are 7 strains of the rabies virus in the world, but people are most often infected by one - the so-called genotype 1. It is also common in Russia.

How infection occurs and why a person has almost no time

Most often, the virus enters the body of a person or animal with the bite of a rabid animal, but cases of human infection during the skinning of sick animals are known: the virus entered the human body through cuts and abrasions. The literature also describes the possibility of aerosol contamination in caves where a large number of virus-infected bats nest, but this is extremely rare.

The closer the bite is to the head, the faster rabies develops - the duration of the incubation period directly depends on the proximity to the brain.

The main problem of rabies is that a person has almost no time: despite the long incubation period, the virus practically does not manifest itself before the onset of symptoms, and the immune system does not have time to react and start fighting the pathogen.

Once in the body, the virus spreads at a breakneck speed — up to 250–400 mm/day — and travels up the nervous system up to the brain using axonal transport. At this time, a person can still be cured - an emergency vaccination is prescribed for the bitten. But if the symptoms have already appeared, then the usual methods cannot save a person - the body simply does not have time to fight the alien. Therefore, the main idea of rabies therapy is precisely to give the patient as much time as possible.

Source: ProDiseases Almost immediately after infection, the synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin (a coenzyme involved in the metabolism of the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine) is disrupted, which leads to impaired synthesis of a number of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and adrenaline. The lethality of the disease at the stage of onset of symptoms is 100%.

The lethality of the disease at the stage of onset of symptoms is 100%.

The disease (from the first symptoms to the death of the patient) lasts from 5 to, in rare cases, 10-12 days.

Milwaukee Protocol: from idea to implementation

The idea that you need to give a person time to cope with the virus on their own has been around for a long time. Even before the Milwaukee Protocol, individual doctors were trying to find a cure for a terrible disease. The first was Michael Huttwick from the Center for Infectious Disease Control in Atlanta. The scientific community is still arguing whether a child bitten by a bat really had rabies and whether he really entered the active stage of the disease, as medical protocols state.

10 Oct 1970 years old, a six-year-old boy was delivered to an Atlanta hospital, bitten on the thumb by a bat. The mouse was examined and five days later it was confirmed to have rabies. For the next 14 days, the boy received a daily rabies vaccine, but by October 30, he became drowsy, which was attributed to an incipient cold. Later, his temperature rose to 40.3, and his neck "stiffened", the doctor explained this as a reaction to the vaccine and advised him to go to the hospital "just in case". On November 14, the boy's speech became slurred, the left side of his body became numb, he lost coordination and fell into a semi-comatose state. It was then that Dr. Michael Hattwick came into play, who suggested that the patient was killed by too rapidly developing symptoms.

Later, his temperature rose to 40.3, and his neck "stiffened", the doctor explained this as a reaction to the vaccine and advised him to go to the hospital "just in case". On November 14, the boy's speech became slurred, the left side of his body became numb, he lost coordination and fell into a semi-comatose state. It was then that Dr. Michael Hattwick came into play, who suggested that the patient was killed by too rapidly developing symptoms.

His plan was to treat all the symptoms at the time of their occurrence and prevent their simultaneous action: anticonvulsants were used for convulsions, tracheotomy for tracheal spasm. Gradually, the manifestations of the disease stopped, and after three months the child left the hospital.

This case was noticed, but it did not become anything really unexpected - most doctors did not believe in the possibility of saving the patient and considered the case a falsification. Most, but not all. And in 2004, the attempt to give the patient time was repeated.

On September 12, 2004, fifteen-year-old Gina Gies was bitten on the index finger of her left hand by a bat. Since the scratch was superficial, the relatives simply washed the wound with peroxide and did not apply for vaccination. After 37 days, symptoms of rabies appeared one after another: drowsiness and tingling in the left arm; after two days, deterioration of vision, loss of balance; the next day - nausea and vomiting without fever, partial ataxia of both hands; later weakness in the left leg, slurred speech. On the fifth day, fever, speech intermittency, nystagmus, tremor of the left hand and convulsions appeared.

Gina was admitted to a hospital in Milwaukee and laboratory tests confirmed active rabies. By this time, Gina could no longer breathe on her own. On the second day of hospitalization, Gina's attending physician, Rodney Willoughby, suggested to the parents an experimental method of treatment - to put Gina into an artificial coma using a mixture of sedatives.

Artificial coma was then used in the treatment of patients with extensive brain damage, trauma and strokes. Putting a patient into a coma for rabies therapy sounded absurd and dangerous—and yet it worked. On the third day of hospitalization, the girl was injected with ribavirin, an antiviral drug that is often used in the treatment of hepatitis C and some other diseases. The doctors hoped that ribavirin would activate the patient's immune system, which would help to produce enough antibodies. The next day, amantadine (an antiviral and antiparkinsonian drug that stimulates dopamine production) was added to ribavirin. On the eighth day of such therapy, in combination with maintenance drugs, the girl's blood was found to contain antibodies to the rabies virus. It was a small victory - before that, no one had been able to see an immune response in an unvaccinated person. On the twelfth day, the girl woke up, on the fourteenth, voluntary eye movement was restored, on the nineteenth, Gina could already voluntarily move her legs and arms. By day 23, Gina was able to sit up and keep her head upright.

By day 23, Gina was able to sit up and keep her head upright.

Tests made on the thirty-first day showed the absence of the virus in the body, but it was still far from complete recovery - for the next six months, Gina took drugs that help restore body functions and underwent a course of rehabilitation.

Gina was finally discharged only in January 2005, and after six months she was already moving independently.

Gina is now 32 years old, graduated from college with a degree in biology and bat diseases, and has given birth to two children. The only thing that reminds her of rabies is the inability to run.

Criticism of the Milwaukee Protocol and attempts to replicate it in other countries

Gina Geese's case shocked the country. The incident was called a miracle and glorified by the doctors who proposed experimental therapy. But there was a lot of criticism: someone believed that Gina was just lucky to be born with a very strong immune response. Someone - that the rabies virus that entered her body was extremely weakened, or that some people have a genetic predisposition to a mild, non-fatal course of the disease. Someone even considered the whole story a hoax. Be that as it may, confirmation that the Milwaukee Protocol really works was required. The only way to prove it was by curing someone else.

Someone - that the rabies virus that entered her body was extremely weakened, or that some people have a genetic predisposition to a mild, non-fatal course of the disease. Someone even considered the whole story a hoax. Be that as it may, confirmation that the Milwaukee Protocol really works was required. The only way to prove it was by curing someone else.

The problem was the high cost of therapy - Gina's treatment cost about $800,000 in total. Obviously, either very rich countries or very rich people could afford the “repetition of the banquet”. At the same time, the protocol did not at all promise 100% patient survival. Dr. Willoughby himself, who proposed the treatment regimen, believed that the survival rate increased only to 20-25% percent. However, without a protocol, there is no survival at all. He also suggested that the protocol mainly works for children and adolescents.

Colombian doctors were the first who decided to check the protocol. In 2008, eight-year-old Nelsi Gomez was bitten by a wild cat. The girl was not vaccinated, and a month later the first symptoms appeared, after which she was urgently hospitalized. The doctors, who decided to follow the protocol, put the patient into an artificial coma, in which she spent two weeks. Nelsie's immune response was ten times stronger than that of Gina Geese, which caused swelling of the brain, which, however, was managed. The recovery went very quickly: within a few weeks, Nelsi had good control of her legs and arms. The protocol worked, but the girl died some time later - apparently, having contracted nosocomial pneumonia.

The girl was not vaccinated, and a month later the first symptoms appeared, after which she was urgently hospitalized. The doctors, who decided to follow the protocol, put the patient into an artificial coma, in which she spent two weeks. Nelsie's immune response was ten times stronger than that of Gina Geese, which caused swelling of the brain, which, however, was managed. The recovery went very quickly: within a few weeks, Nelsi had good control of her legs and arms. The protocol worked, but the girl died some time later - apparently, having contracted nosocomial pneumonia.

Around the same time, in the fall of 2008, another case of protocol therapy was recorded: 15-year-old Marciano Meneses from Brazil contracted rabies after being bitten by a bat. He was given an emergency vaccination, but this did not help - a month later the boy developed symptoms of rabies. The doctors decided to follow the protocol and put the patient into an artificial coma. After leaving it, Martianu could move, but artificial lung ventilation was required. After a year of maintenance therapy and rehabilitation, the child fully recovered. Now he is 28 years old, he lives on his parents' farm.

After a year of maintenance therapy and rehabilitation, the child fully recovered. Now he is 28 years old, he lives on his parents' farm.

Anyway, the first cases confirmed the possible effectiveness of the protocol. By the beginning of 2012, there were already four confirmed cases of recovery from rabies in the United States under the Milwaukee Protocol, in total, six such cases were known in the world at that time.

About 35 cases of the protocol have been documented to date, although by no means all patients ultimately survived - as Dr. Willoughby suggested, the overall survival rate is about 20-25%.

In Russia, treatment according to the Milwaukee Protocol was applied in 2011 at the Krasnodar Clinical Children's Hospital for Infectious Diseases. A six-year-old boy was hastily put into a coma, supporting the body with drugs. He spent a month in this state, after which the virus disappeared from the body. Unfortunately, the boy died from a stroke, the cause of which could not be determined - most likely, he became a complication of rabies. This was the first and only case of therapy according to the protocol, after which no more attempts were made in our country. Partly because of the high cost.

This was the first and only case of therapy according to the protocol, after which no more attempts were made in our country. Partly because of the high cost.

What else?

In addition to the Milwaukee Protocol, other rabies therapy options are available. The already mentioned ribavirin, together with interferon-α and ketamine, showed good results in vitro and in laboratory animals, but did not show an effect in humans after the first manifestations of rabies. The main problem with their use is that the drugs cannot cross the blood-brain barrier into the brain, the main site of the virus. A number of scientists are actively working on the creation of a drug that would be able to overcome the BBB - this would lead to the emergence of a truly effective cure for rabies.

Another treatment option similar to artificial coma is artificial hypothermia, strong cooling of the body. As with an artificial coma, hypothermia reduces the metabolic rate, reduces oxidative stress and other destructive processes - and the body gets more time to fight. In practice, however, hypothermia has not yet been used.

In practice, however, hypothermia has not yet been used.

Rabies, despite attempts at treatment, is still a 100% lethal disease. So far, the best protection against it is vaccination, both of animals and humans. However, a full-fledged therapy with a survival rate of more than 20% is most likely not far off.

Without 40 injections. What you need to know about rabies in humans. Society news

How do they get infected?

Domestic dogs and cats most commonly infect humans, and those in the wild. Rabies affects foxes, wolves, raccoon dogs, bats, even hedgehogs and crows.

You can get infected by the bite of a sick animal or the ingress of saliva on damaged areas of the skin. Therefore, you should not pick up cubs found in the forest or try to pet adult animals.

Atypical behavior for a wild animal, for example, lack of fear of humans, is one of the signs of the disease.

Can a person infect a person?

The rabies virus is almost instantly killed in the open air under direct sunlight, as well as when boiled. In the stomach, it is destroyed in about 20 minutes.

In the stomach, it is destroyed in about 20 minutes.

An infected person cannot transmit the virus to another person. The pathogen penetrates the patient's peripheral nervous system and begins to move into its central sections at a rate of approximately 3 mm per hour.

Photo: pixabay.com 29 Jun 2022 16:51

How the new veterinary rules for rabies control work in the Belgorod Region 07 May 2021 15:33

In the Belgorod region, the incidence of rabies in animals has increased 3 times 25 Jul 2018 11:53

If a person is bitten by a rabid animal, is this a death sentence?

Not at all. It is important to provide preventive treatment in time - before the onset of signs of the disease.

It is important to provide preventive treatment in time - before the onset of signs of the disease.

The disease develops slowly. The incubation period can last from 7 days to a year. It depends on the site of the bite, the depth of the wound, as well as the age and health of the victim.

The most dangerous bites are on the head, neck, and hands. In this case, the symptoms of the disease may appear earlier than 50 days after the bite.

How does the infected feel?

Initially, there is discomfort at the site of the bite. By that time, the wound may have already healed, but the pain, burning, swelling will remain.

A person develops a temperature, sleep and appetite are disturbed, inexplicable fears appear, and sometimes hallucinations.

Rabies vaccinations are no longer effective when the first symptoms of the disease appear.

In the second stage of the disease, a person develops hydrophobia (fear of water), dehydration occurs. The patient reacts inadequately to bright light, loud sounds, he may begin uncontrollable violent seizures. The pupils dilate, the patient can look at one point for a long time.

The pupils dilate, the patient can look at one point for a long time.

Often the heart stops during an attack. If this does not happen, the third stage occurs - paralysis. The temperature rises to 40 degrees, the heart beats strongly, and over the next day the entire body is paralyzed.

From a scratch to a wound. What to do if you are bitten

What to do if bitten by a suspicious animal?

If bitten by an unfamiliar animal and even a pet, if he has not been vaccinated against rabies, you need to urgently seek medical help.

The patient will receive an injection on the same day.

40 injections in the abdomen?

No. Such a scheme for preventing the disease has long been abandoned. Doctors use the modern Kokav vaccine.

After completion of the prophylactic course, a person develops immunity.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/recognizing-and-treating-a-yeast-diaper-rash-284385_V3-aecf9328ee0b491992c051f490e5a4bf.png)