How much does the average parent spend on their child

The Cost of Raising a Child

Posted by Mark Lino, Economist at the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion in Food and Nutrition

Feb 18, 2020

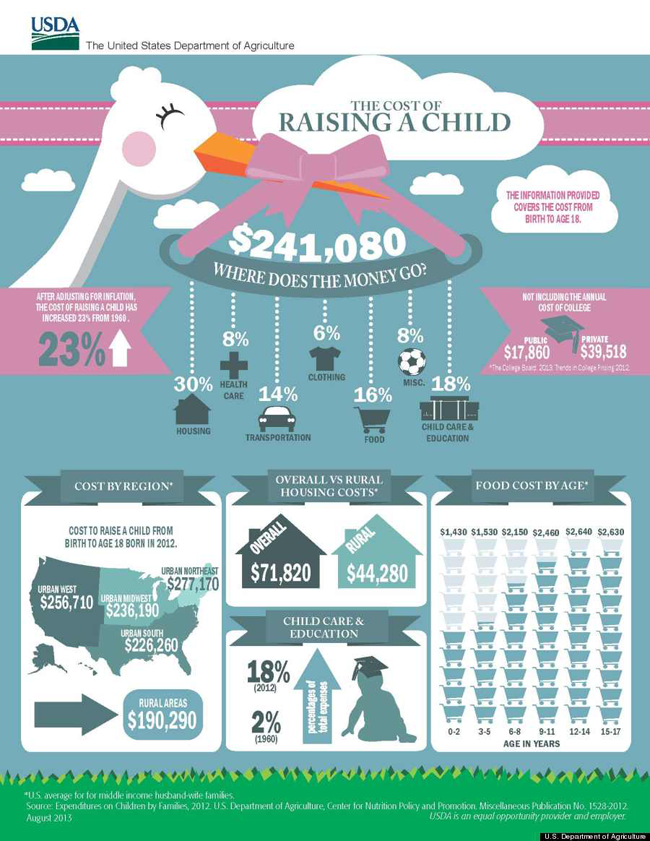

Families Projected to Spend an Average of $233,610 Raising a Child Born in 2015.USDA recently issued Expenditures on Children by Families, 2015. This report is also known as “The Cost of Raising a Child.” USDA has been tracking the cost of raising a child since 1960 and this analysis examines expenses by age of child, household income, budgetary component, and region of the country.

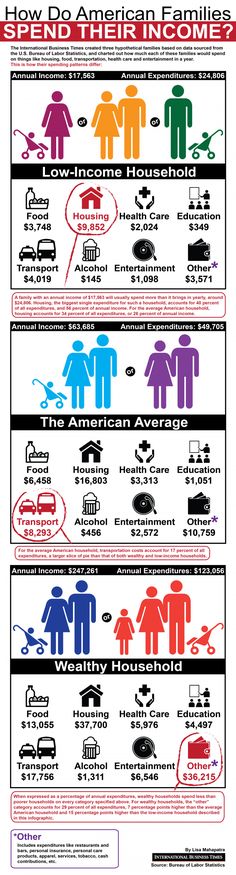

Based on the most recent data from the Consumer Expenditures Survey, in 2015, a family will spend approximately $12,980 annually per child in a middle-income ($59,200-$107,400), two-child, married-couple family. Middle-income, married-couple parents of a child born in 2015 may expect to spend $233,610 ($284,570 if projected inflation costs are factored in*) for food, shelter, and other necessities to raise a child through age 17. This does not include the cost of a college education.

Where does the money go? For a middle-income family, housing accounts for the largest share at 29% of total child-rearing costs. Food is second at 18%, and child care/education (for those with the expense) is third at 16%. Expenses vary depending on the age of the child.

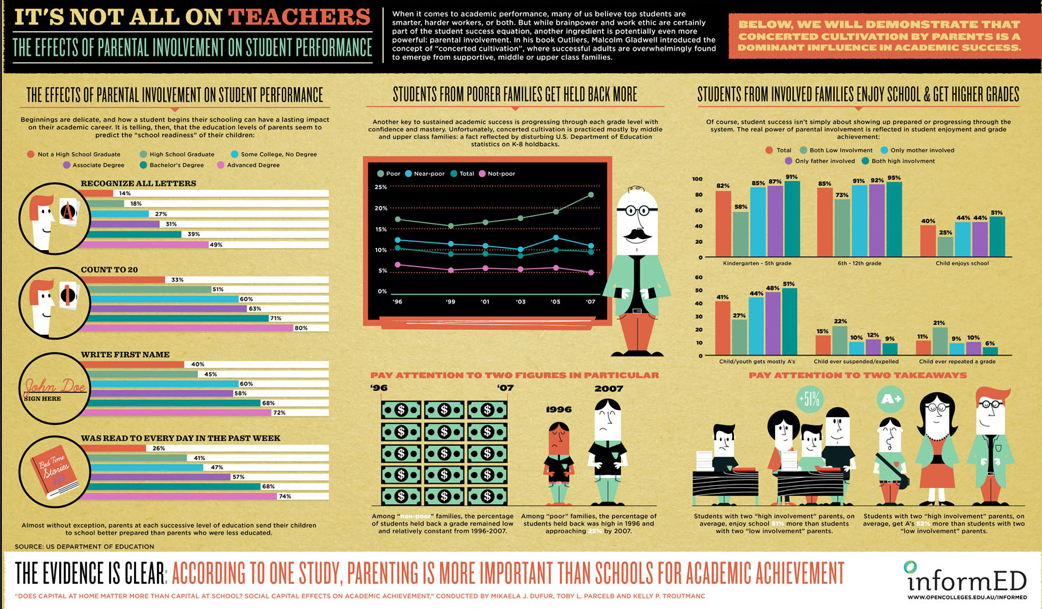

As families often need more room to accommodate children, housing is the largest expense.We did the analysis by household income level, age of the child, and region of residence. Not surprising, the higher a family’s income the more was spent on a child, particularly for child care/education and miscellaneous expenses.

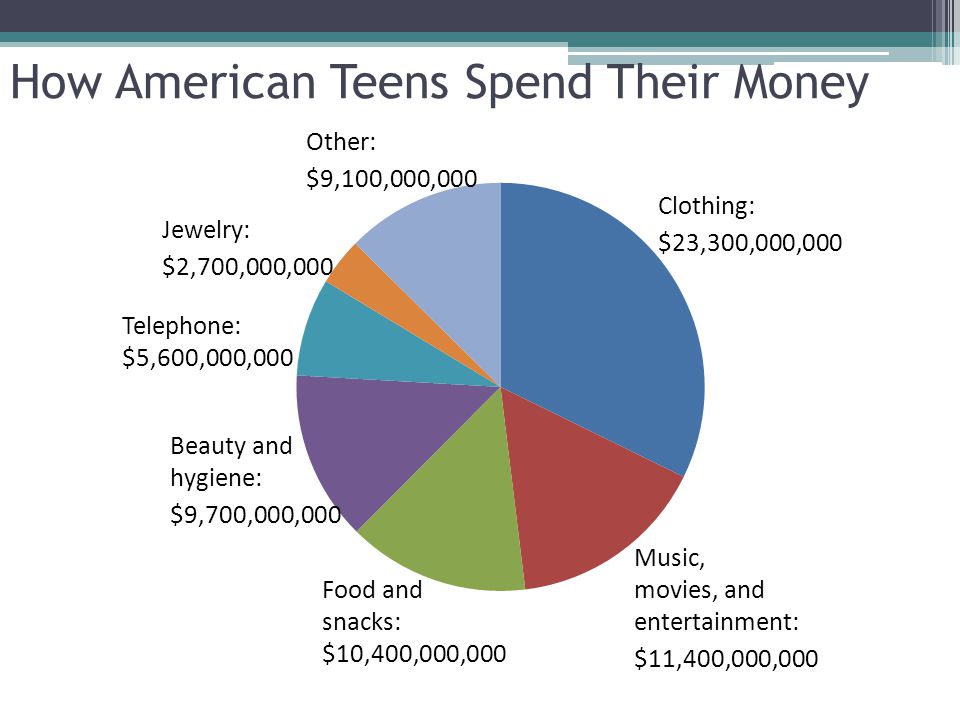

Expenses also increase as a child ages. Overall annual expenses averaged about $300 less for children from birth to 2 years old, and averaged $900 more for teenagers between 15-17 years of age. Teenagers have higher food costs as well as higher transportation costs as these are the years they start to drive so insurance is included or a maybe a second car is purchased for them.

Teenagers have higher food costs as well as higher transportation costs as these are the years they start to drive so insurance is included or a maybe a second car is purchased for them.

Regional variation was also observed. Families in the urban Northeast spent the most on a child, followed by families in the urban West, urban South, and urban Midwest. Families in rural areas throughout the country spent the least on a child—child-rearing expenses were 27% lower in rural areas than the urban Northeast, primarily due to lower housing and child care/education expenses.

Child-rearing expenses are subject to economies of scale. That is, with each additional child, expenses on each declines. For married-couple families with one child, expenses averaged 27% more per child than expenses in a two-child family. For families with three or more children, per child expenses averaged 24% less on each child than on a child in a two-child family. This is sometimes referred to as the “cheaper by the dozen” effect. Each additional child costs less because children can share a bedroom; a family can buy food in larger, more economical quantities; clothing and toys can be handed down; and older children can often babysit younger ones.

Each additional child costs less because children can share a bedroom; a family can buy food in larger, more economical quantities; clothing and toys can be handed down; and older children can often babysit younger ones.

This report is one of many ways that USDA works to support American families through our programs and work. It outlines typical spending by families from across the country, and is used in a number of ways to help support and education American families. Courts and state governments use this data to inform their decisions about child support guidelines and foster care payments. Financial planners use the information to provide advice to their clients, and families can access our Cost of Raising a Child calculator, which we update with every report on our website, to look at spending patterns for families similar to theirs. This Calculator is one of many tools available on MyMoney. gov, a government research and data clearinghouse related to financial education.

gov, a government research and data clearinghouse related to financial education.

This year we released the report at a time when families are thinking about their plans for the New Year. We’ve been focusing on nutrition-related New Year’s resolutions – or what we are referring to as Real Solutions - on our MyPlate website, ChooseMyPlate.gov. This report and the updated calculator can help families as they focus on financial health resolutions. This report will provide families with a greater awareness of the expenses they are likely to face while raising children.

In addition to the report and the calculator, we also have a dedicated section on ChooseMyPlate.gov that provides tips and tools to aid families and individuals in making healthy choices while staying on a budget. For strategies beyond food, our friends at MyMoney.gov offer a wealth of information to help Americans plan for their financial future.

For more information on the Annual Report on Expenditures on Children by Families, also known as the cost of raising a child, go to: www. fns.usda.gov/resource/expenditures-children-families-reports-all-years.

fns.usda.gov/resource/expenditures-children-families-reports-all-years.

*Projected inflationary costs are estimated to average 2.2 percent per year. This estimate is calculated by averaging the rate of inflation over the past 20 years.

Editor’s Note (March 8, 2017): The comparison of rural vs. urban northeast child care and education value has been updated.

Visit the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s MyMoney.gov for more resources to ensure financial well-being this New Year’s season!Category/Topic: Food and Nutrition

Tags: children choosemyplate. gov CNPP Cost of Raising a Child economics Expenditures on Children by Families Food and Nutrition mymoney.gov MyPlate Research

gov CNPP Cost of Raising a Child economics Expenditures on Children by Families Food and Nutrition mymoney.gov MyPlate Research

Cost of Raising a Child

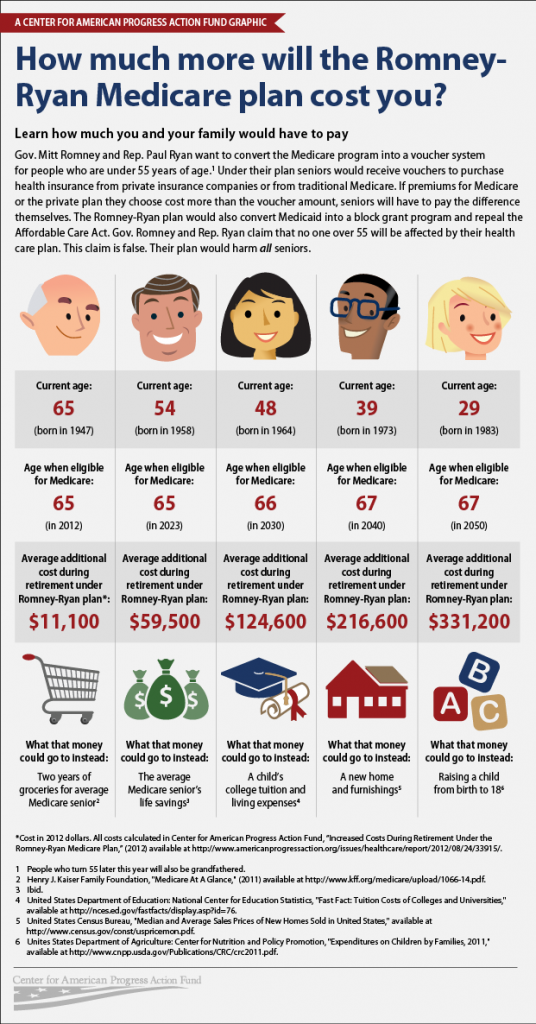

How much does it cost to have a baby and raise them? A 2015 study done by the USDA found that it cost an estimated $233,610 to raise two children from birth to age 17 in a middle-income family with two parents. That figure, adjusted for inflation, is just over a quarter of a million dollars at $286,000 in 2022. Shouldering the cost of raising children can be an additional pressure on parents, especially as costs continue to rise. Here’s what you need to know.

How much does it cost to have a baby?

Having a child is an undeniably major life change. Women and families today may be more anxious to understand how life and their financial situation might change with a baby, whether anticipated or unplanned. Here are just some of the expected costs related to having and raising a baby:

Women and families today may be more anxious to understand how life and their financial situation might change with a baby, whether anticipated or unplanned. Here are just some of the expected costs related to having and raising a baby:

- The average cost of powdered formula is around $400-$800 per month for babies who are exclusively fed on formula. This cost could be different depending on your situation, such as if your baby needs special formula, if there is a formula shortage or recall or if your baby is also fed breast milk. (Babycenter.com)

- A study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that the total costs associated with being pregnant, experiencing childbirth and postpartum care averaged $18,865. (Kaiser Family Foundation)

- That same study found that average vaginal deliveries cost $14,768, with $2,655 paid out of pocket, while the average cesarean section cost $26,280, with $3,214 paid out of pocket.

(Kaiser Family Foundation)

(Kaiser Family Foundation) - A home birth could cost between $1,500 to $5,000, but typically isn’t covered by health insurance. (Healthline)

- Adoption and in vitro fertilization (IVF) costs can also vary. One cycle of IVF could range between $4,900 to $30,000 depending how the procedure is performed, while private adoption fees could be between $20,000 to $45,000. (Healthline)

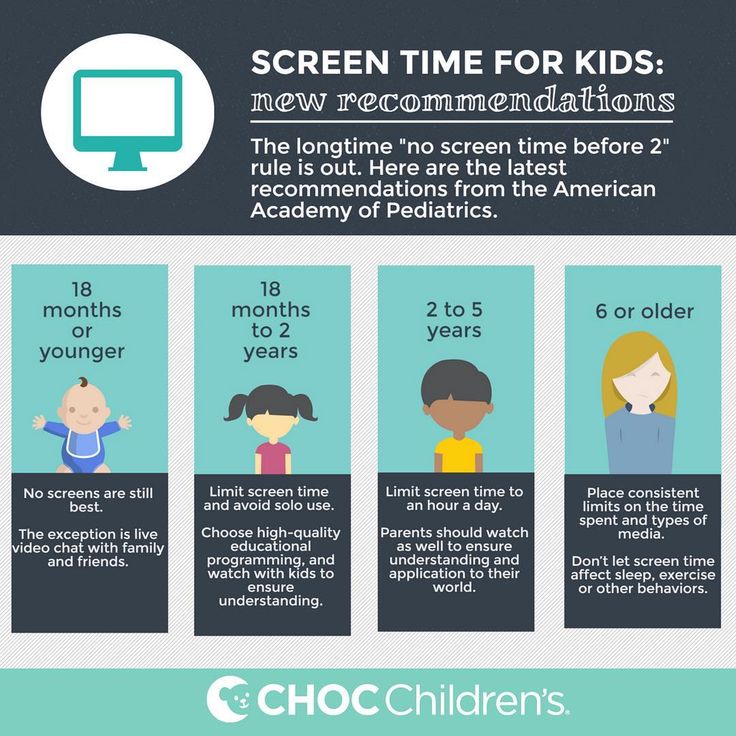

- The annual cost of childcare for infants to four years old averages about $10,000 per child for center-based care and $8,000 for home-based care. (S. Treasury Department)

- A survey from CNBC found that the weekly cost of a nanny for a single child in 2021 was $694, up from $565 in 2019. An after school sitter in 2021 was $261, slightly higher than the 2019 figure of $243. (CNBC)

- That same study found that parents reported spending more than 20% of their household income on childcare, although 72% reported spending 10% or more.

(CNBC)

(CNBC) - With babies going through 6-12 diapers per day, this could mean up to $936 per year, or $18 a week, spent on disposable diapers. (Healthline)

- Getting all the necessary gear for a baby, like strollers, car seats, play pens and carriers, can cost anywhere from $425 to nearly $3,000. (The Bump)

How much do school expenses cost?

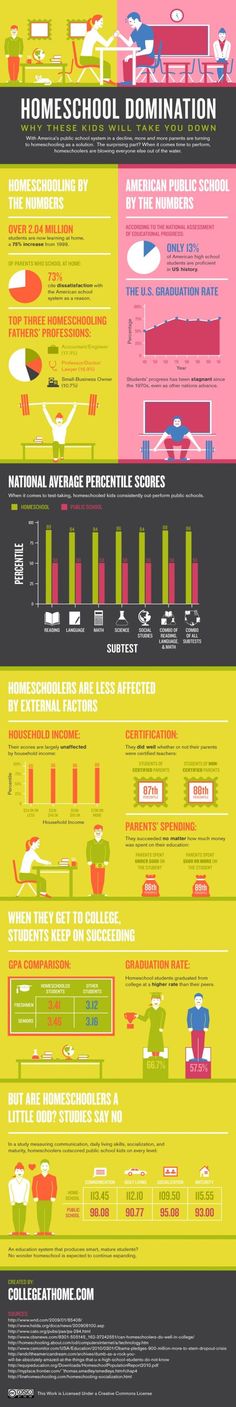

A major expense when it comes to raising children is the cost of education. Starting with preschool, the average cost per year of tuition can range from $4,460 to $13,158 per year, or about $372-$1,100 per month.

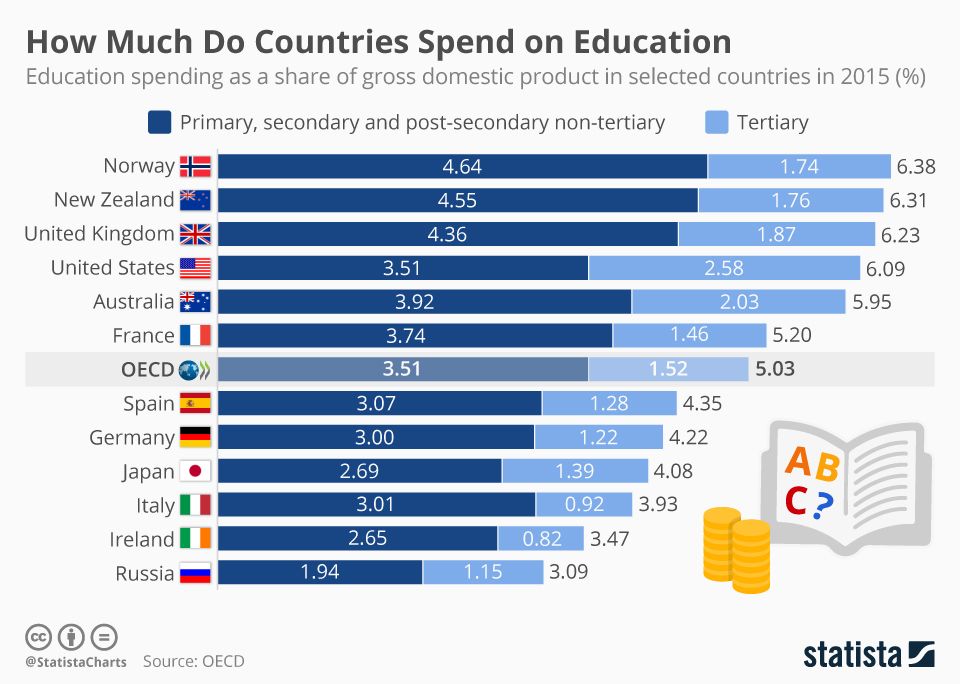

When it comes to kindergarten through high school, parents can choose between public and private schools. For private schools, the Education Data Initiative estimated that tuition costs an average of $12,350 per year. Associated costs, like technology, textbooks, back-to-school supplies and more, could bring that up to $16,050. For a child to be in private school from kindergarten through eighth grade, the estimated cost could be around $208,650.

For a child to be in private school from kindergarten through eighth grade, the estimated cost could be around $208,650.

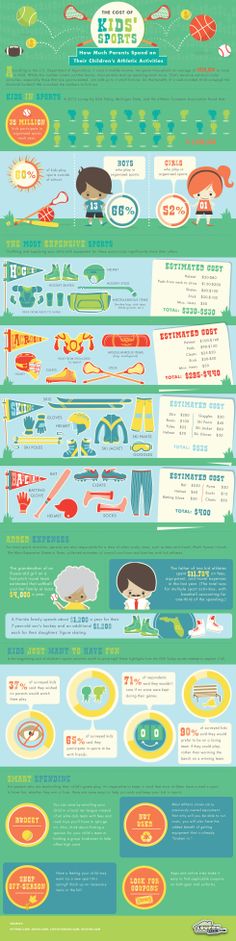

Public schools don’t charge a tuition fee like private schools, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t costs as well. In 2016, the University of Michigan estimated that it cost $302 per student to play sports, $218 for arts like music, theater or yearbook, and $124 for other clubs. These figures included costs like participation fees, equipment and travel, and may have been increased since due to inflation.

Paying for college

Currently, the average cost of full-time undergraduate tuition for a public university ranges from $10,740 for in-state students and $27,560 for out-of-state students. Parents who choose to pay for college can take advantage of savings plans like the 529 plan. Starting early in your kids’ lives allows you to leverage time to build up savings for your child’s post-high school education.

The school that your child attends matters, too. While they may receive a lower tuition for attending an in-state public school, they may want to go out-of-state as well. Below are the most expensive and cheapest states for out-of-state students attending a 4-year public university:

While they may receive a lower tuition for attending an in-state public school, they may want to go out-of-state as well. Below are the most expensive and cheapest states for out-of-state students attending a 4-year public university:

Five cheapest states for out-of-state students attending a 4-year public university

- Florida: $4,463 per year

- Wyoming: $4,747 per year

- District of Columbia: $6,020 per year

- Nevada: $6,023 per year

- Utah: $6,700 per year

Five most expensive states for out-of-state students attending a 4-year public university

- New Jersey: $14,360 per year

- Illinois: $14,455 per year

- Pennsylvania: $15,565 per year

- New Hampshire: $16,679 per year

- Vermont: $17,083 per year

Other costs of raising a child

Though housing, food and child care are the highest cost categories related to raising a child to age 18, they are not the only expenses to consider. Other necessities like clothing, education and health care can be expensive. All of these categories should also be considered when factoring in the costs of having and raising a child.

Other necessities like clothing, education and health care can be expensive. All of these categories should also be considered when factoring in the costs of having and raising a child.

As your child gets older and earns their driver’s license, for instance, this could be a significant expense — Bankrate’s research found that adding your 16-year-old to your car insurance policy runs an average of $2,531 per year, although there are some relatively affordable car insurance options available for teens.

Housing

Housing is arguably the most significant expense associated with raising a child. In the USDA report, housing costs make up 29% of the overall cost of raising a baby. The cost of housing varies widely by location and the type of housing you choose. Many parents dream of a suburban house with a white picket fence and enough bedrooms for the entire family.

Based on a $250K dwelling coverage amount, the average cost of home insurance is $1,383 per year, according to 2021 Quadrant Information Services data. This is just one factor in the cost of owning a home; you will also have to consider the cost of a mortgage, utilities and maintenance.

This is just one factor in the cost of owning a home; you will also have to consider the cost of a mortgage, utilities and maintenance.

Food

The cost of food is the second-largest expense, at 18% of the overall cost of raising a child. Over time, food prices have trended up, with food-at-home pricing increasing 12.1% and food-away-from-home pricing increasing by 7.7% from June 2021 to July 2022. The USDA expects rising costs for 2022, with increases as high as 10.0% and 7.5%, respectively.

To eat healthy foods, like high-quality meats and fresh fruits and vegetables, food expenses increase even more. In 2022, the costs for all food categories are expected to increase:

- Meats: +9.0%-10.0%

- Processed fruits and vegetables: +8.5%-9.5%

- Cereals and bakery products:0%-13.0%

Life insurance

Life insurance is crucial for families, especially if your income cannot be easily replaced if the unexpected were to happen. Funeral costs, living and education expenses and more can quickly add up even for those who budget carefully. Because of this, it’s also important to have a plan in the event that you or your partner are no longer able to financially support your children. Some parents rely on life insurance to ensure that, if they were to pass away, their family would be able to maintain their lifestyle and have some financial cushion for the future.

Funeral costs, living and education expenses and more can quickly add up even for those who budget carefully. Because of this, it’s also important to have a plan in the event that you or your partner are no longer able to financially support your children. Some parents rely on life insurance to ensure that, if they were to pass away, their family would be able to maintain their lifestyle and have some financial cushion for the future.

Both parents should consider purchasing adequate life insurance to replace their salary, even for a stay-at-home parent. A recent survey completed by Salary.com estimates the annual salary of a stay-at-home parent at $184,820 per year. In addition, life insurance is typically the least expensive when you are young and healthy, especially if you choose term instead of permanent life insurance.

The bottom line

Raising children is rewarding and fulfilling to many people. But it’s also very expensive these days. Infancy to age 18 is likely to cost you close to a quarter of a million dollars or more as a parent. But by preparing mentally and implementing financial planning strategies, you can be well-equipped to raise your child to adulthood comfortably, even on a budget. Given the ever-growing costs of raising a child, parents thinking of having a baby might want to consider some of the following tips: start early with a budget, try to live below your means, save money wherever possible, shop around for home and auto insurance each year for the best deal and purchase life insurance when you are young and healthy.

But by preparing mentally and implementing financial planning strategies, you can be well-equipped to raise your child to adulthood comfortably, even on a budget. Given the ever-growing costs of raising a child, parents thinking of having a baby might want to consider some of the following tips: start early with a budget, try to live below your means, save money wherever possible, shop around for home and auto insurance each year for the best deal and purchase life insurance when you are young and healthy.

Should an adult child give money to the family?

43,994

To parentsA person among people

- Photo

- Shutterstock/Fotodom.ru

Until they reach adulthood, parents are required to provide for their children - that's what the law says. But after the age of 18, the “child” may remain a student or not study at all, but then it is already a voluntary decision of the parents to feed and clothe him. And if a son or daughter finds a job, even if it is temporary, for many, a difficult question arises: should he or she contribute to the family budget?

And if a son or daughter finds a job, even if it is temporary, for many, a difficult question arises: should he or she contribute to the family budget?

We conducted a survey in which the opinions of the participants were quite divided. 35% believe that they "should", 26% that they "shouldn't". Moreover, many noted that they would refuse to take money from a child, even if he himself offered them. 39% of respondents answered that everything is determined by the financial situation of the family. And 13% of them give the right to decide to the child himself and are ready to agree with him in any case.

"Must"

People with an average income took part in the survey. This means that the participation of a child in the family budget is not a matter of family survival, but rather a matter of principle, tradition or educational moment.

-

“I think I should. Well, I mean, it's his family. Of course, it is up to him to decide, but if, for example, a refrigerator is bought with his money, he will be able to be proud of himself.

-

“I think it's cool if an 18+ person gets the experience of contributing to a family. I would agree on some feasible regular responsibility. For example, if a child uses something himself, then he regularly pays for it. Internet, for example. Or some segment of products (for tea, coffee). This will not help the budget much, but it will give a person a sense of his strength, and get used to the fact that he will have to regularly invest in caring for loved ones - those with whom you are now.

-

“Child 18+? It would be good for such a “child” to have an idea of \u200b\u200bresponsibility and chip in for common needs if he wants to live with his parents and enjoy common benefits. Or let him live separately, if he believes that he does not owe anything to anyone. If he does not yet have such an understanding, then parents need to be helped to form it, creating an objective need to share honestly earned money.

-

“Even if you bring a loaf of bread bought with your own money, this is also a contribution.

”

”

“Shouldn't”

More than a quarter of respondents believe that while a child is studying, he can spend money on his personal needs. But many specify that after graduation, it's time to look for a job and separate from your parents, rent your own apartment and manage your own budget.

-

“No, it's his money while he lives with me and studies. As soon as he learns - work, a suitcase and an independent life.

-

"Let it be better to invest in yourself and fly."

-

“I don't know, but my parents forbade me to work while I was studying. They gave money. And now I keep them. In the middle there was a period when no one owed anything to anyone.”

-

“I dug a lot into the issue with a psychologist and realized one thing for myself: no one owes anything to anyone. You can give your child a choice: if you want, invest, and then we will invest (down payment on a mortgage or a car). If you don’t want to, it’s also your choice, be independent, and then we will decide according to the circumstances, but don’t make any demands.

”

” -

“If dad and mom don't need, then they shouldn't. At worst, they can pay a communal apartment together. He buys a lot of food outside the house anyway.

-

“If he is still studying, then all his part-time work. If you have already unlearned or dropped out of school and are fully working, it’s time to live separately.”

-

“No, I shouldn't give money. But he must make every effort to live separately. Let him save up for rent.”

“Depends on…”

For many participants, the wealth of the family is of decisive importance in resolving this issue.

-

“I worked as a student and tried to cover all my needs so as not to be a burden to my parents. And, by the way, the first repair in the apartment was at my expense. I don't think sharing is necessary, but optional. But a normal teenager will always share honestly earned money with his parents. It's a way to show your worth as a person.

"

" -

“I think it depends a lot on the wealth of the family and the motivation of the child. For example, a child from a millionaire's family goes to work to get a feel for life and understand how much a pound is worth. Well, what is the contribution to the family budget? Not even a millionaire. If the child's contribution does not significantly change the family budget, then there is no need to pretend. Or another case. A middle-class family, the child earns for his entertainment, clothes, gadgets. Excellent. He's already very helpful. You can exempt him from contributing to the payment of utility bills and food. The third situation is a poor family. It is clear that this contribution is expected and it is rather the norm.”

-

“I think that the attitude to money should be formed by example, and from the age of 10-12 you should learn how to handle it, save it, appreciate it, and then by the age of 18 the child will naturally want to participate in the general budget.

”

” -

“According to a Jewish saying, children should give money to their children, not to their parents. Work for work experience, not for income. But if every penny counts, then everyone is working.”

-

“I would look at a side job positively by agreement with the child. Let him provide for his personal needs. Gains experience. I really like the American tradition, when teenagers work in the summer and often for free, to gain life experience in the field they plan to do. I really believe in stories when they grow from a newspaper peddler to the owner of a publishing house.

-

“If it is possible not to spend a child's money on living, then let work be a continuation of education for him. I myself worked on holidays from the age of 13, I earned more than my mother. He spent money on clothes, electronics, school supplies, and his sweets. It took almost the whole year. At 18, I was already making decent money and just once or twice a week I filled the refrigerator with food.

And then somehow my childhood ended abruptly, and I began to live separately, got my own family.

And then somehow my childhood ended abruptly, and I began to live separately, got my own family.

If the process drags on

Many parents are frustrated that their adult children, after graduating from college and getting a job, continue to take money from them.

“Children grow up as dependents. They grow up, but their light bulb does not turn on, that parents need help. My decently for 30, but do not help. Not because bad kids. They just don't think about it."

“In theory, it should. But most people only dream of such a thing.”

Quite often the situation is complicated by the discrepancy between the positions of the two parents. “The youngest gets more than 80 thousand, I get half as much. Mom gives him money, as before, to pay for the apartment. My wife and I do not have a common position. I try to speak, but it doesn't end well. Well, I won’t say more,” writes one of the survey participants. “It’s not annoying, although it’s clear that it’s so wrong. ”

”

“A smooth transition from a parenting relationship to cooperation with your own child is the final stage of his upbringing,” comments Ekaterina Klochkova, family system consultant. “Therefore, it is important that the next step towards the child’s adulthood is as comfortable as possible for everyone.

Material contribution to the family budget is a new rule of interaction. When discussing it, you can rely on the already established household duties of the child and talk about their expansion, taking into account his capabilities.

Parent-child relationships are moving into a new quality — the older generation is turning from caring and authoritative figures into wise advisers

parents.

The opportunity to make a material contribution to the family budget is an important signal for parents and children that the child has already grown up, becomes able to take full responsibility for his life and can build communication with parents as an adult.

Unfortunately, in our culture, such a move may seem eccentric, but it has an important communicative aspect for both parties. Participating in the financial life of the family, your son or daughter seems to be saying: “I am no longer a child and I can pay part of my expenses myself.”

Parents' careful attitude and care during this period is manifested in the fact that they help to make the child's transition to full responsibility for his life smooth and gradual. On the one hand, it is important to give the opportunity and time to adapt, to pay only part of the costs. On the other hand, in this way to demonstrate faith in his strength. Recognition that he is independent.

Psychotherapist, counseling psychologist

Text: Elena Sivkova

New on the site

Is it time to worry? Checklist for assessing the emotional state

Breaking deadlines and depression: what perfectionism leads to

“I am raising my daughter and working, forgetting about myself. Where to get strength?

Where to get strength?

Genius is you: a guide for those who are looking for a new calling

Psychological defenses: why we need them

"Tired of swings in relationships, but not ready to leave"

“I fell in love with a married boss. How to control feelings at work?

How to prevent cheating: advice from scientists — strengthen your relationship

Children and money

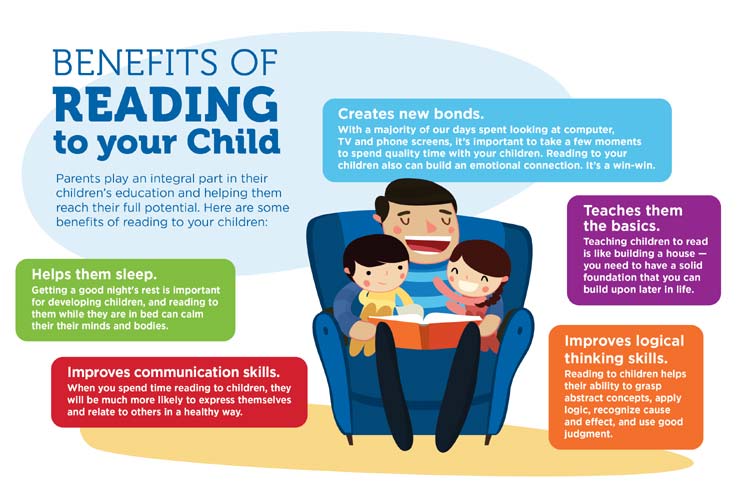

In the family of some of my acquaintances, the first word that my son said was “money”. The boy's parents were very surprised and even saddened by this, because we all want money to be just a concomitant circumstance. However, in this family, the topic of money was constantly discussed in the variant: “there is not enough money, where can I get it from?”. How to raise a child who will be “friends” with money, appreciate it, make savings, spend wisely? Parents should think about this at the very early age of their children, and not when the first problems come (childish theft, greed or extravagance, complete inability to navigate in the financial sector), because children draw their knowledge about money relations from the comments and reactions of parents.

Greed or economy?

We do not teach a small child to save or spend money, we teach him to take care of toys, appreciate purchases, do not forget molds in the sandbox and not lose mittens in winter. Or, on the contrary, we are calm about the fact that everything is lost, broken, forgotten, and just buy him a new one. It is these parental actions-attitudes that form the future attitude of the child to money.

A few years ago, I observed this situation from the outside: two girls were simultaneously bought a new model of a baby doll with a pot and special cereals. The doll could be fed with porridge, and she went to the potty. Separately, "porridge" was not sold. A girl from one family immediately opened all the bags and diluted a giant portion of porridge. The other looked at it with horror, realizing that the bags should be saved. She cherished the cherished bags so much that, when she reached adolescence, she found them in her old toys. These four-year-old girls already showed two opposite traits: extravagance and economy. This is already a small result of the action of parental attitudes: do not spend too much, there will be no other, or, conversely, seize the moment, live for your own pleasure.

These four-year-old girls already showed two opposite traits: extravagance and economy. This is already a small result of the action of parental attitudes: do not spend too much, there will be no other, or, conversely, seize the moment, live for your own pleasure.

Observing how parents and close people manage resources also brings up the attitude towards money. Do they easily throw away cherished products or recycle them? Do they throw away unwanted clothes, donate them to those in need, or sell them? Children notice all these little things and shake them off. Whichever approach you take, so will your child.

An interesting situation occurs when parents from families with different economic attitudes simultaneously broadcast them to their children. One day, a couple came to me for a parenting consultation after arguing for years about the lights being left on and the water running in vain. The wife's attitude sounded something like this: "why bother yourself with dim lighting and twilight if the payment for resources is minimal?" The husband’s attitude was the opposite: “if there is an opportunity to save money, you need to save money in order to buy something valuable later. ” In the wife's family, comfort and relaxation were valued, in the husband's family, the increase in social and economic status through savings. The couple faced a dilemma: which of the installations to follow as the main one? Each defended his own: the husband saved, the wife spent, and the children absorbed both. What attitudes children who have grown up in this contradiction will follow will be seen over time: either the influence of one of the parents will be stronger, or it will be some other position. We can never foresee what a child will choose when equally important people profess different values. But there is a golden mean between greed and economy, and between generosity and extravagance, and the choice of how to raise a child is up to you.

” In the wife's family, comfort and relaxation were valued, in the husband's family, the increase in social and economic status through savings. The couple faced a dilemma: which of the installations to follow as the main one? Each defended his own: the husband saved, the wife spent, and the children absorbed both. What attitudes children who have grown up in this contradiction will follow will be seen over time: either the influence of one of the parents will be stronger, or it will be some other position. We can never foresee what a child will choose when equally important people profess different values. But there is a golden mean between greed and economy, and between generosity and extravagance, and the choice of how to raise a child is up to you.

Mine—yours—someone else's

used. It is then that children begin to form an attitude towards property - so far, this role is played by the values of the children's world, that is, toys. Hence the first manifestations of greed, when the kids cling tightly to their buckets in the sandbox and are not going to share with anyone. This does not mean greed as such, but that the child has entered a new period of his psychological development. “I won’t give” means that the baby has already experienced the new concept of “mine—not mine.”

Hence the first manifestations of greed, when the kids cling tightly to their buckets in the sandbox and are not going to share with anyone. This does not mean greed as such, but that the child has entered a new period of his psychological development. “I won’t give” means that the baby has already experienced the new concept of “mine—not mine.”

Some mothers mistakenly perceive it this way: at first the child was kind and shared, and then deteriorated and became greedy. But it is rather the other way around. The child initially shared because he did not feel the boundaries between his own and others, and only realizing that not the whole world belongs to him, he began to keep exactly his own. And such important qualities as future greed or generosity depend on how parents relate to his “holds”, whether the word “alien” will become forbidden or will be a reason to expand the boundaries of “one's own”.

It is very important to teach a child, even a small one, not to take someone else's without the permission of the owner, to exchange toys with other children. It is also worth respecting the right of the child to defend his own. “Misha loves this car very much, he is probably not ready to share it yet, maybe you can play with our ball instead of the car?” - the mother of the “greedy” can say to the baby, who is already ready to exchange toys. It is the parents who should pronounce the most important points of such interaction. If you are the mother of a child who heard “I won’t give it!” from another kid, then his refusal can be commented as follows: “He doesn’t want to give his tractor, it’s his toy, and we can’t do anything, let’s play with a spatula?”.

It is also worth respecting the right of the child to defend his own. “Misha loves this car very much, he is probably not ready to share it yet, maybe you can play with our ball instead of the car?” - the mother of the “greedy” can say to the baby, who is already ready to exchange toys. It is the parents who should pronounce the most important points of such interaction. If you are the mother of a child who heard “I won’t give it!” from another kid, then his refusal can be commented as follows: “He doesn’t want to give his tractor, it’s his toy, and we can’t do anything, let’s play with a spatula?”.

Unfortunately, often we ourselves allow children to take someone else's, forcing others to share, and not our own, justifying his actions by saying that he is still small. An untimely taboo on someone else's property leads to unconscious permission to take someone else's, especially when you really want to, and, accordingly, to theft.

First money

The abstract value of banknotes is not easy for children to understand. Often, kids offer their parents, if they don’t have money, to go to an ATM, where banknotes are given out to everyone. By the age of four or five, they already understand that you can’t buy anything in a store without money, they like to take change, rejoicing in its quantity, and not in face value. Then, already before school, they understand the differences in the value of banknotes, they can control a simple commodity-money exchange, and then they begin to save “their” money.

Often, kids offer their parents, if they don’t have money, to go to an ATM, where banknotes are given out to everyone. By the age of four or five, they already understand that you can’t buy anything in a store without money, they like to take change, rejoicing in its quantity, and not in face value. Then, already before school, they understand the differences in the value of banknotes, they can control a simple commodity-money exchange, and then they begin to save “their” money.

A preschool child should be initiated into commodity-money relations gradually, but this must be done. At first, the child is interested in giving the banknote to the seller instead of the parents, then taking the change. Take to give to parents, not to take away. The main thing is that a child should not have his own money if he does not understand their economic value. If you let your child play with change, there is nothing wrong with that. It is important that he does not perceive it only as a toy (there should be a special place for small things, a container), but also as a value of the adult world. And here an interesting question arises - whose money is it: the child's or the parent's?

And here an interesting question arises - whose money is it: the child's or the parent's?

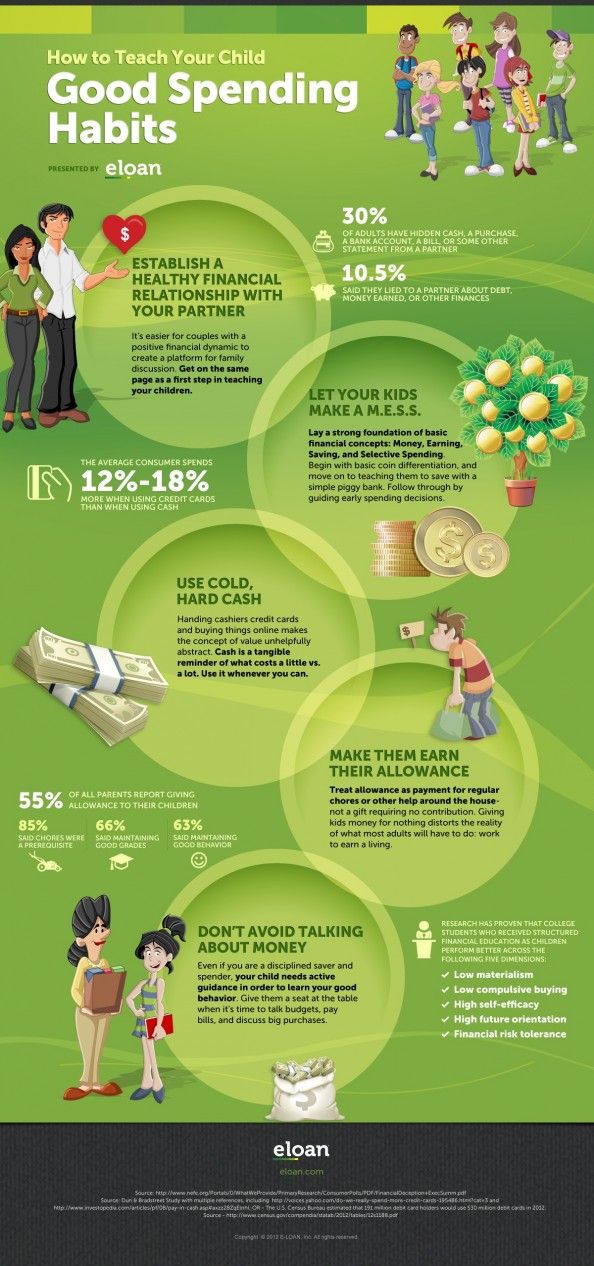

The answer seems to be simple - whoever earned them belongs to him. But some parents agree to consider them childish. Modern grandparents often give money to children just like that, give them for the holidays. On the one hand, this is a good opportunity for preschoolers to practice their ability to manage money. However, there is one BUT that must be taken into account: a child cannot and should not manage money that he did not earn himself! Responsibility for children's money lies with the parents, so all decisions should be subject to discussion. Parents, controlling how the child spends "their" money, can teach him the processes of financial management. Accumulate, plan the necessary purchases, spend on hobbies or momentary desires - you can try all the tactics, the main thing is to help the child draw the right conclusions.

In elementary school, a child has a new category of money - pocket money. The degree of independence of the child and the number of options for dealing with money are growing - now he has the opportunity to buy a bun in the buffet, ice cream after school, borrow or borrow money. The question of how much pocket money to give, or whether to give it at all, is decided by the parents, based on their financial situation. But if a child does not have small amounts for pocket expenses, he does not have the opportunity to learn these financial transactions, make the first mistakes, and gain his experience. The child spends pocket money himself, but from time to time it is important to be interested in where they go, at what speed and what conclusions the young financier makes.

The degree of independence of the child and the number of options for dealing with money are growing - now he has the opportunity to buy a bun in the buffet, ice cream after school, borrow or borrow money. The question of how much pocket money to give, or whether to give it at all, is decided by the parents, based on their financial situation. But if a child does not have small amounts for pocket expenses, he does not have the opportunity to learn these financial transactions, make the first mistakes, and gain his experience. The child spends pocket money himself, but from time to time it is important to be interested in where they go, at what speed and what conclusions the young financier makes.

Childish stealing

I think that almost every adult can remember an episode from his childhood, associated with theft. Someone stole buns in the store, someone stole money from their parents ... Therefore, a one-time "action" can be classified as children's experiments, but parents need to respond correctly to such an act. Correctly— means to treat it as something unacceptable, terrible and requiring your increased attention. Even if you treat this condescendingly, precisely as a child's experiment with the boundaries of what is permissible, you must react strictly.

Correctly— means to treat it as something unacceptable, terrible and requiring your increased attention. Even if you treat this condescendingly, precisely as a child's experiment with the boundaries of what is permissible, you must react strictly.

At the same time, not every appropriation of someone else's is theft — there must be self-interest or intent in it. Accordingly, the child must already operate with the concepts of "mine" and "alien".

If a three-year-old child takes a purse from her mother's bag while she is chatting with a friend, this is not stealing, but an opportunity to talk and learn the rules. If a teenager who knows all the rules for a long time does the same, this is already theft. Everything illegally seized must be returned to the owner with an apology from the child or parents. Often, parents are ashamed to return the stolen, and they release the situation on the brakes, limiting themselves to swearing and edification. But according to the law, theft is considered a completed crime from the moment when the perpetrator seized someone else's property and got a real opportunity to dispose of it at his own discretion, regardless of whether he managed to realize this opportunity or not.

Why do children experiment with strangers? There are many reasons for stealing: parents did not impose a strict taboo on it; the child fights with parents for power; the child wants to conquer the whole world, feeling that he is above all parental rules; he feels his deprivation, uselessness and restores "justice"; he had an experience of appropriation with impunity and enjoyed it. There are many reasons, but often they come down to two opposite parental attitudes: connivance and disrespect for the child's personal boundaries. There are always psychological reasons for stealing, and understanding them correctly is very important for both parents and children. Often this is a way to say something to the world, parents or yourself. By understanding this language, a child can be taught to express himself in a socially acceptable way.

Should I pay my child money?

Parents often think about this question, but everyone answers it differently. Usually, there are not many options for what to pay a child for: good grades at school, house cleaning and other “services”. In life, the principle of payment is logical and simple: work can be called an item or service for which an outsider is ready to pay money, because for him it is a value. A person who cleans windows in his own house, of course, works, but does not earn, at most, saves. But if he washes the windows in someone else's apartment, this is already earnings. However, parents often apply completely different principles of financial incentives for children.

Usually, there are not many options for what to pay a child for: good grades at school, house cleaning and other “services”. In life, the principle of payment is logical and simple: work can be called an item or service for which an outsider is ready to pay money, because for him it is a value. A person who cleans windows in his own house, of course, works, but does not earn, at most, saves. But if he washes the windows in someone else's apartment, this is already earnings. However, parents often apply completely different principles of financial incentives for children.

Parents who pay tuition fees think that this way they increase their motivation to study. “Studying at school is like a job, so we pay for it by introducing a system of bonuses and penalties” - I come across such ideas quite often. However, I recently met a family who similarly encouraged their four-year-old daughter to go to kindergarten. The girl did not want to visit him, and her parents assumed that the garden was the same job for her as their professional work was for mom and dad. The girl reasonably remarked that they were making money there, but she was not. After this conversation, the parents agreed with the teacher that she would pay the girl a “salary” at the end of each week, and she began to visit the garden more willingly. The financial stimulus had the desired effect, but thanks to what? What conclusions does a child draw when he receives money for things that are not labor?

The girl reasonably remarked that they were making money there, but she was not. After this conversation, the parents agreed with the teacher that she would pay the girl a “salary” at the end of each week, and she began to visit the garden more willingly. The financial stimulus had the desired effect, but thanks to what? What conclusions does a child draw when he receives money for things that are not labor?

Going to kindergarten, studying at school, cleaning the house are not labor, but life processes, the results of which bring benefits to the child, and not to society.

Parents who pay for this “labor” substitute concepts, drawing an extra material element into the parent-child relationship. Often this does not lead to an increase in motivation, but to the accumulation of funds through dishonest play. In studies, this manifests itself as follows: deuces are actively hidden, fives are attributed, second diaries are started, a lot of other tricks are invented. The child learns to cheat, not earn honestly. Motivation for learning is when it is interesting for me to study, I myself see sense, purpose and perspective in this matter, I enjoy it. Tuition fees reinforce the idea that education is not for the child, but for the parents.

The child learns to cheat, not earn honestly. Motivation for learning is when it is interesting for me to study, I myself see sense, purpose and perspective in this matter, I enjoy it. Tuition fees reinforce the idea that education is not for the child, but for the parents.

Domestic work is much the same, but there is one difference. All housework can be roughly divided into three categories. The first two are labor in the name of oneself (clean one's room, wash and iron one's clothes, etc.) and labor for the benefit of the family (wash the floor in the apartment, bake a cake, go to the store, sit with a younger brother, etc.). d.). These actions are not paid for moral reasons. The third category is serious and high-quality work for the benefit of the family, when the child performs someone's duty. Here you can already think about payment.

For example, you have always used the services of a window cleaner and you know perfectly well how much it costs and what quality the work should be. Your teenage daughter offers you her services for the same pay. She needs money, you need clean windows. In the process of washing, she learns how money is earned by physical labor, how fastidious the “owners” are who check the quality and speed of work, how to negotiate the amount of payment, and how quickly this payment evaporates from the wallet ... And the daughter’s work must be evaluated as strictly as the work of an outsider, or reduce payment for poor quality.

Your teenage daughter offers you her services for the same pay. She needs money, you need clean windows. In the process of washing, she learns how money is earned by physical labor, how fastidious the “owners” are who check the quality and speed of work, how to negotiate the amount of payment, and how quickly this payment evaporates from the wallet ... And the daughter’s work must be evaluated as strictly as the work of an outsider, or reduce payment for poor quality.

In the question of whether to pay or not to pay a child for work, there are two criteria: the willingness to pay for this work (service) to an outsider and the obligation/not the obligation of the child to perform this work.

General financial awareness

Sometimes parents try to prolong their children's childhood and hide from them the entire financial life of the family -expenses, loans, plans. “Why does he need to know our difficulties? We'll take care of everything,” parents think.

From the age of 9-10, it is reasonable to begin to dedicate a child to the financial situation of the family, that is, to explain, tell and comment. It is important that the child sees how you prioritize, what you are doing to improve your financial situation: do you earn more or spend less? What financial principles does your family live by? This awareness, on the one hand, brings the child down to earth, and on the other hand, makes him a participant in the family process. The collision of children's consumer position with the principle of reality and the possibilities of parents is very sobering for the child and helps to develop responsibility in him.

I recently witnessed a conversation between a thirteen year old girl and her mother. Making plans for the next year, the daughter asks: “Mom, will you give me money for a trip to a ballet competition in Germany?” Mom, in response, is interested in her daughter’s previous plans-desires: “So the trip to your birthday in Paris is canceled?” - "Not". — “And in the summer to the language camp?” - "Not". “And with us at sea with the whole family?” - "Not". — “So during the year you plan to go to Germany, to Paris, to a foreign language camp and to the sea with everyone?” Mom clarifies. And he hears in response: "Yes ... Do you think it's too much?". “Daughter, great desires, but you know our financial capabilities,” says mom. The girl thought. Mom is not against her desires, only they will have to be correlated with the financial reality of the family and prioritized.

— “And in the summer to the language camp?” - "Not". “And with us at sea with the whole family?” - "Not". — “So during the year you plan to go to Germany, to Paris, to a foreign language camp and to the sea with everyone?” Mom clarifies. And he hears in response: "Yes ... Do you think it's too much?". “Daughter, great desires, but you know our financial capabilities,” says mom. The girl thought. Mom is not against her desires, only they will have to be correlated with the financial reality of the family and prioritized.

When parents initiate their children into the principles of their decisions, children become participants in events, and not just their weak-willed followers. This teaches the child to limit his desires, to plan and rely on reality. How many people, chasing their “I want”, have taken excessive loans? The ratio between "I want" - "I can" - "I can't" determines the degree of maturity of a person as a person.

Money is not a toy for children

In order for children to grow up to be financially successful people, it is necessary to instill in them from an early age those values that you think will help them in this.