How much breastmilk at 6 months with solids

How much expressed milk will my baby need? • KellyMom.com

By Kelly Bonyata, BS, IBCLC

- How much milk do babies need?

- What if baby is eating solid foods?

- Is baby drinking too much or too little expressed milk?

- Other ways of estimating milk intake

- References

Image credit: Jerry Bunkers on flickr

How much milk do babies need?

Many mothers wonder how much expressed breastmilk they need to have available if they are away from baby.

Now infants can get

all their vitamin D

from their mothers’ milk;

no drops needed with

our sponsor's

TheraNatal Lactation Complete

by THERALOGIX. Use PRC code “KELLY” for a special discount!

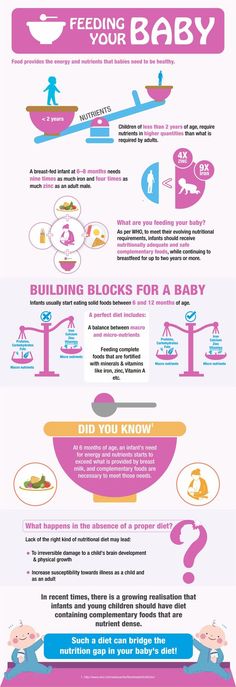

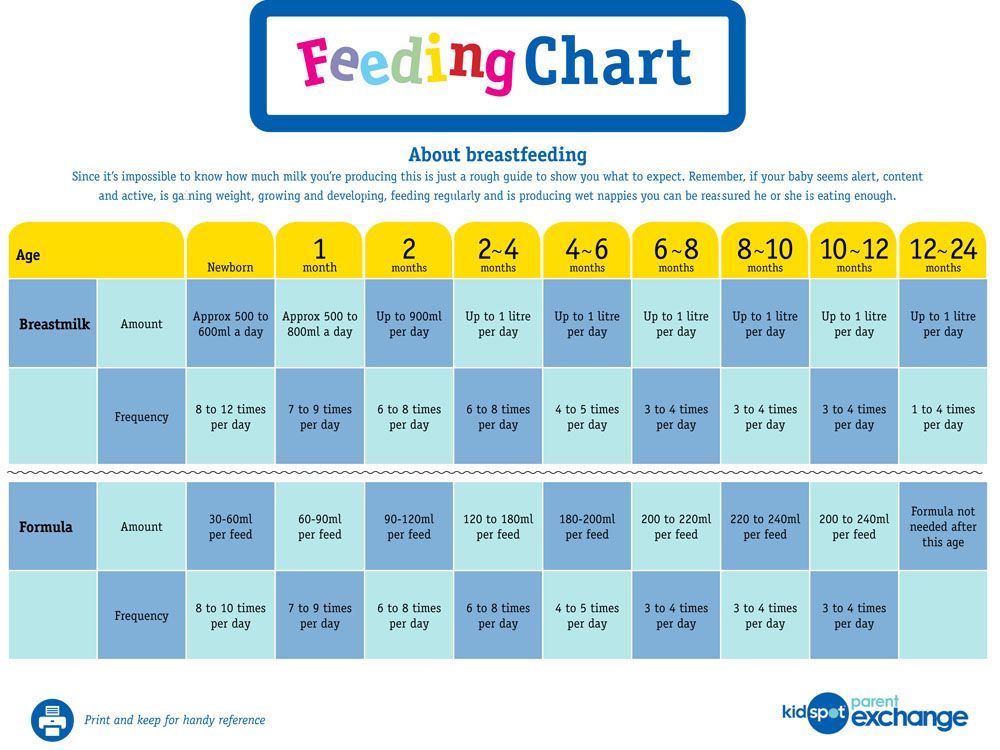

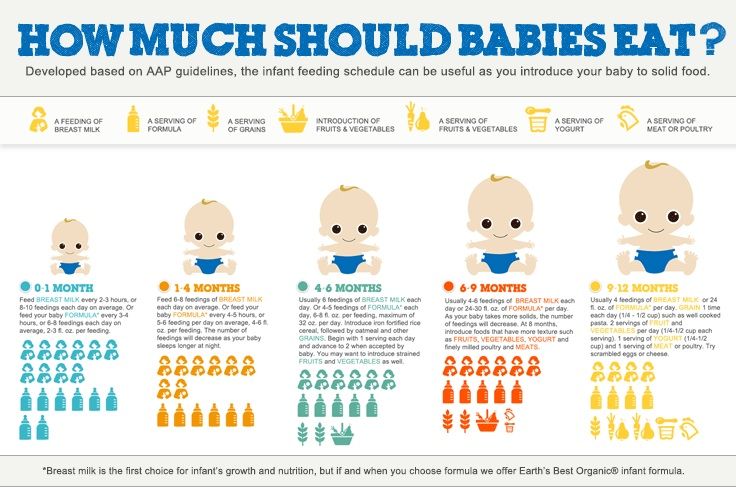

In exclusively breastfed babies, milk intake increases quickly during the first few weeks of life, then stays about the same between one and six months (though it likely increases short term during growth spurts). Current breastfeeding research does not indicate that breastmilk intake changes with baby’s age or weight between one and six months. After six months, breastmilk intake will continue at this same level until — sometime after six months, depending in baby’s intake from other foods — baby’s milk intake begins to decrease gradually (see below).

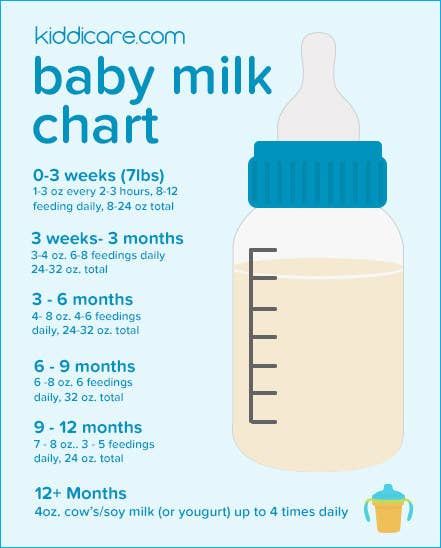

The research tells us that exclusively breastfed babies take in an average of 25 oz (750 mL) per day between the ages of 1 month and 6 months. Different babies take in different amounts of milk; a typical range of milk intakes is 19-30 oz per day (570-900 mL per day).

We can use this information to estimate the average amount of milk baby will need at a feeding:

- Estimate the number of times that baby nurses per day (24 hours).

- Then divide 25 oz by the number of nursings.

- This gives you a “ballpark” figure for the amount of expressed milk your exclusively breastfed baby will need at one feeding.

Example: If baby usually nurses around 8 times per day, you can guess that baby might need around 3 ounces per feeding when mom is away. (25/8=3.1).

(25/8=3.1).

What if baby is eating solid foods?

Sometime between six months and a year (as solids are introduced and slowly increased) baby’s milk intake may begin to decrease, but breastmilk should provide the majority of baby’s nutrition through the first year. Because of the great variability in the amount of solids that babies take during the second six months, the amount of milk will vary, too. One study found average breastmilk intake to be 30 oz per day (875 ml/day; 93% of total intake) at 7 months and 19 oz (550 ml/day; 50% of total energy intake) at 11-16 months.

Several studies have measured breastmilk intake for babies between 12 and 24 months and found typical amounts to be 14-19 oz per day (400-550 mL per day). Studies looking at breastmilk intake between 24 and 36 months have found typical amounts to be 10-12 oz per day (300-360 mL per day).

Is baby drinking too much or too little expressed milk?

Keep in mind that the amount of milk that baby takes at a particular feeding will vary, just as the amount of food and drink that an adult takes throughout the day will vary. Baby will probably not drink the same amount of milk at each feeding. Watch baby’s cues instead of simply encouraging baby to finish the bottle.

Baby will probably not drink the same amount of milk at each feeding. Watch baby’s cues instead of simply encouraging baby to finish the bottle.

If your baby is taking substantially more than the average amounts, consider the possibility that baby is being given too much milk while you are away. Things that can contribute to overfeeding include:

- Fast flow bottles. Always use the lowest flow bottle nipple that baby will tolerate. Even with a slower flowing nipple, it is important to pace the bottle feed to allow baby to better control his intake.

- Using bottle feeding as the primary way to comfort baby. Some well-meaning caregivers feed baby the bottle every time he makes a sound. Use the calculator above to estimate the amount of milk that baby needs, and start with that amount. If baby still seems to be hungry, have your caregiver first check to see whether baby will settle with walking, rocking, holding, etc. before offering another ounce or two.

- Baby’s need to suck.

Babies have a very strong need to suck, and the need may be greater while mom is away (sucking is comforting to baby). A baby can control the flow of milk at the breast and will get minimal milk when he mainly needs to suck. When drinking from a bottle, baby gets a larger constant flow of milk as long as he is sucking. If baby is taking large amounts of expressed milk while you are away, you might consider encouraging baby to suck fingers or thumb, or consider using a pacifier for the times when mom is not available, to give baby something besides the bottle to satisfy his sucking needs.

Babies have a very strong need to suck, and the need may be greater while mom is away (sucking is comforting to baby). A baby can control the flow of milk at the breast and will get minimal milk when he mainly needs to suck. When drinking from a bottle, baby gets a larger constant flow of milk as long as he is sucking. If baby is taking large amounts of expressed milk while you are away, you might consider encouraging baby to suck fingers or thumb, or consider using a pacifier for the times when mom is not available, to give baby something besides the bottle to satisfy his sucking needs. - If, after trying these suggestions, you’re still having a hard time pumping enough milk, see I’m not pumping enough milk. What can I do?

If baby is taking significantly less expressed milk than the average, it could be that baby is reverse-cycling, where baby takes just enough milk to “take the edge off” his hunger, then waits for mom to return to get the bulk of his calories. Baby will typically nurse more often and/or longer than usual once mom returns. Some mothers encourage reverse cycling so they won’t need to pump as much milk. Reverse cycling is common for breastfed babies, especially those just starting out with the bottle.

Baby will typically nurse more often and/or longer than usual once mom returns. Some mothers encourage reverse cycling so they won’t need to pump as much milk. Reverse cycling is common for breastfed babies, especially those just starting out with the bottle.

If your baby is reverse cycling, here are a few tips:

- Be patient. Try not to stress about it. Consider it a compliment – baby prefers you!

- Use small amounts of expressed milk per bottle so there is less waste.

- If you’re worrying that baby can’t go that long without more milk, keep in mind that some babies sleep through the night for 8 hours or so without mom needing to worry that baby is not eating during that time period. Keep an eye on wet diapers and weight gain to assure yourself that baby is getting enough milk.

- Ensure that baby has ample chance to nurse when you’re together.

Other ways of estimating milk intake

There are various ways of estimating the amount of milk intake related to the weight of the baby and the age of the baby, based upon formula intake – research has shown that after the early weeks these methods overestimate the amount of milk that baby actually needs. These are the estimates that we used for breastfed babies for years, with the caveat that most breastfed babies don’t take as much expressed milk as estimated by these methods. Current research tells us that breastmilk intake is quite constant after the first month and does not appreciably increase with age or weight, so the current findings are validating what moms and lactation counselors have observed all along.

These are the estimates that we used for breastfed babies for years, with the caveat that most breastfed babies don’t take as much expressed milk as estimated by these methods. Current research tells us that breastmilk intake is quite constant after the first month and does not appreciably increase with age or weight, so the current findings are validating what moms and lactation counselors have observed all along.

More:

- Breast Versus Bottle: How much milk should baby take? By Nancy Mohrbacher, IBCLC, FILCA

- Supplementation Guidelines from LowMilkSupply.org

References

Onyango, Adelheid W., Receveur, Olivier and Esrey, Steven A. The contribution of breast milk to toddler diets in western Kenya. Bull World Health Organ, 2002, vol.80 no.4. ISSN 0042-9686.

Salazar G, Vio F, Garcia C, Aguirre E, Coward WA. Energy requirements in Chilean infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000 Sep;83(2):F120-3.

Kent JC, Mitoulas L, Cox DB, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. Breast volume and milk production during extended lactation in women. Exp Physiol. 1999 Mar;84(2):435-47.

Breast volume and milk production during extended lactation in women. Exp Physiol. 1999 Mar;84(2):435-47.

Persson V, Greiner T, Islam S, and Gebre-Medhin M. The Helen Keller international food-frequency method underestimates vitamin A intake where sustained breastfeeding is common. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, vol.19 no.4. Tokyo, Japan: United Nations University Press, 1998.

Cox DB, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. Blood and milk prolactin and the rate of milk synthesis in women. Exp Physiol. 1996 Nov;81(6):1007-20.

Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Lonnerdal B. Maternal versus infant factors related to breast milk intake and residual milk volume: the DARLING study. Pediatrics. 1991 Jun;87(6):829-37.

Neville MC, et al. Studies in human lactation: milk volumes in lactating women during the onset of lactation and full lactation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988 Dec;48(6):1375-86.

Dewey KG, Finley DA, Lonnerdal B. Breast milk volume and composition during late lactation (7-20 months). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984 Nov;3(5):713-20.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984 Nov;3(5):713-20.

Butte NF, Garza C, Smith EO, Nichols BL. Human milk intake and growth in exclusively breast-fed infants. J Pediatr. 1984 Feb;104(2):187-95.

Dewey KG, Lonnerdal B. Milk and nutrient intake of breast-fed infants from 1 to 6 months: relation to growth and fatness. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1983;2(3):497-506.

Brown K, Black R, Robertson A, Akhtar N, Ahmed G, Becker S. Clinical and field studies of human lactation: methodological considerations. Am J Clin Nutr 1982;35:745-56.

Jelliffe D, Jelliffe E. The volume and composition of human milk in poorly nourished communities: a review. Am J Clin Nutr 1978;31:492-515.

| Summary of Research Data | ||||

| Baby’s Age | Average Milk Intake per 24 hours | Reference | ||

| g | ml | oz | ||

| 5 days | 498 +/- 129 g | 483 ml | 16 oz | Neville 1988 |

| 1 mo | 728 g | 706 ml | 24 oz | Salazar 2000 |

| 1 mo | — | 673 ml | 23 oz | Dewey 1983 |

| 1 mo | 708 +/- 54. 7 g 7 g | 687 ml | 23 oz | Cox 1996 |

| 1-6 mo | 453.6+/-201 g per breast | 440 ml x2 = 880 ml | 30 oz | Kent 1999 |

| 3 mo | 818 g | 793 ml | 27 oz | Dewey 1991 |

| 3-5 mo | 753 +/- 89 g | 730 ml | 25 oz | Neville 1988 |

| 6 mo | — | 896 ml | 30 oz | Dewey 1983 |

| 6 mo | 742 +/- 79.4 g | 720 ml | 24 oz | Cox 1996 |

| 7 mo | — | 875 ml (93% of total energy intake) | 30 oz | Dewey 1984 |

| 11-16 mo | — | 550 ml (50% of total energy intake) | 19 oz | Dewey 1984 |

| 11-16 mo | 502 +/- 34 g | 487 ml (32% of total energy intake) | 16. 5 oz 5 oz | Onyango 2002 |

| 12-17 mo | 563 g | 546 ml | 18 oz | Brown 1982 |

| 12-23 mo | 548 g | 532 ml | 18 oz | Persson 1998 |

| 15 mo | 208.0+/-56.7 g per breast | 202 ml x2 = 404 ml | 14 oz | Kent 1999 |

| 18-23 mo | 501 g | 486 ml | 16 oz | Brown 1982 |

| >24 mo | 368 g | 357 ml | 12 oz | Brown 1982 |

| 24-36 mo | 312 g | 303 ml | 10 oz | Persson 1998 |

| Specific Gravity of Mature Human Milk = 1.031, so Density of Mature Human Milk ~ 1.031 g/ml;1 oz = 29.6 ml;Numbers in gray were derived using the above conversion factors. | ||||

Breastfeeding beyond 6 months | Medela

When your baby starts solids, you may think he no longer needs breast milk. However, breastfeeding after six months has numerous benefits for you both

However, breastfeeding after six months has numerous benefits for you both

Share this content

Is breastfeeding still important after you’ve reached the six-month milestone? And how long should you continue? The answers may surprise you, as the additional health and developmental benefits of breastfeeding – which solid foods and other milks cannot offer – are often overlooked.

How long should I breastfeed for?

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends breastfeeding for two years and beyond – and this applies to families around the world, not just in developing countries.1

“It’s important to note the WHO doesn’t set a maximum breastfeeding duration,”2 says Dr Leon Mitoulas, Medela’s Head of Breastfeeding Research. “From an anthropological perspective, breastfeeding for between two-and-a-half and seven years would be optimal.3 However, cultural norms today generally entail weaning at a much younger age. ”

”

The WHO’s recommendations are supported by a recent surge in research into the first 1,000 days of a child’s life – from conception to the second birthday.4 Dr Mitoulas explains: “Scientists have discovered the right nutrition, and other factors, have the most profound impact on growth and long-term health during this time. Evidence unequivocally demonstrates that breastfeeding is uniquely beneficial during that crucial 1,000-day window.

“Breastfeeding can be considered a food, a medicine and a signal all at the same time,”5 he adds. “And these trifold benefits certainly continue beyond two years.”

Food: Nutritional benefits of extended breastfeeding

Once your baby starts eating solids at around six months, you might think your breast milk becomes just a ‘drink’ that complements them. In fact, the opposite is true – your baby will only get a tiny proportion of his calories and nutrients from food when he first starts solids.

“The undisputed best start for babies is exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months. But even after your baby starts eating complementary foods, breast milk provides significant nutrition,” says Dr Mitoulas.

But even after your baby starts eating complementary foods, breast milk provides significant nutrition,” says Dr Mitoulas.

When exclusively breastfeeding, a baby typically consumes 750 to 800 ml (26.4 to 28 fl oz) of milk each day. At nine to 12 months old, he could still take around 500 ml (17.6 fl oz) a day, which provides about half his daily calories. By 18 months, he’ll probably have about 200 ml (7 fl oz) a day, which is about 29% of his calories.6

It’s true that after six months your baby needs other foods for nutrients that he may not get from your breast milk or his own reserves, including iron, zinc and vitamins B and D.1,7 But even in his second year of life, breast milk provides significant amounts of other key nutrients, as Dr Mitoulas explains:

“At this stage, breast milk provides about 43% of a baby’s protein, 60% of his vitamin C, 75% of his vitamin A, 76% of his folate, and 94% of his vitamin B12.”8

Medicine: Health benefits of breastfeeding after six months

Whilst the message to promote exclusive breastfeeding for six months is well known, there is not much information on the role of breastfeeding and human milk beyond six months, once complementary foods have been introduced to an infant's diet. This is despite organisations such as the WHO recommending the provision of human milk beyond six months.1

This is despite organisations such as the WHO recommending the provision of human milk beyond six months.1

Continuing to breastfeed after six months has been shown to lower the chances of some childhood and adult illnesses and, if your baby does get ill, helps him recover more quickly.

Breastfeeding protects your baby from infection and illness, so much so that it’s even considered a form of ‘personalised medicine’, with potential lifelong effects,” says Dr Mitoulas.

For example, breastfeeding for longer than six months has been shown to protect your baby against certain childhood cancers, such as acute lymphocytic leukaemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.9 Breastfeeding might also lessen his chances of developing type 2 diabetes,10 although this effect is confounded, or attenuated by factors such as smoking, gestational weight gain, preterm birth and other factors. There are also benefits for your baby in terms of sight 11 , dental problems,12 and obesity. ”13

”13

Your breast milk can also reduce your baby’s risk of diarrhoea and sickness,14 gastroenteritis, colds and flu, thrush and ear, throat and lung infections.9,15 This is especially helpful as he gets older and starts interacting with other children or going into childcare, where germs can be rife.

Breastfeeding can also be a lifesaver, as Dr Mitoulas points out: “The consequences of not breastfeeding between six and 23 months can be dire in low- and middle-income countries, where babies who aren’t breastfed are twice as likely to die from infection as babies who are breastfed, even partly.”16 And breastfeeding is not just about the benefits of your milk, it’s also wonderful for nurturing and calming your baby. Nothing soothes an upset infant or toddler like a nursing session with mum. As your baby grows, a feed helps with everything from teething and vaccinations to the inevitable knocks and scrapes or viruses that occur along the way. For many mums, breastfeeding can feel like a miracle worker.

For many mums, breastfeeding can feel like a miracle worker.

Signal: Enhanced benefits

The act of being close to your baby, instantly responding to his needs and engaging in lots of eye contact also sends signals between you. Scientists think these could affect many aspects of your child’s development, from appetite to academic performance. The longer you breastfeed, the stronger the positive outcome is likely to be.

Breast milk contains thousands of active molecules,” Dr Mitoulas explains. “These range from enzymes that help digest fats17 and hormones that regulate appetite,18 to immune molecules that promote immune system development.19

Did you know that breast milk is actually alive? Every day your baby drinks millions to billions of living cells20 – there are thousands of them in each millilitre of your milk, including stem cells,”21 he continues. “Each one of these cells has a specific job in terms of keeping your baby healthy, and research is ongoing to discover exactly how these components benefit an infant during long-term breastfeeding. ”

”

One thing that’s already known is that extended breastfeeding has a positive impact on a child’s IQ. Studies show a consistent three-point IQ advantage for children who were breastfed over those who were never breastfed.22

Breastfeeding beyond six months has even been linked to fewer behavioural problems in school-age children23 and improved mental health in children and adolescents.24

Shouldn’t I switch to follow-on formula after six months?

The health claims on the packaging may look impressive, but there is no better milk for your baby than your own.

No formula milk contains all the antibodies, live cells, growth factors, hormones or helpful bacteria, nor the array of enzymes, amino acids and micronutrients found in breast milk.25 Your milk adjusts to provide your baby with more infection-fighting antibodies and white blood cells when he’s ill26 – something formula simply can’t do. Read Breast milk vs formula: How similar are they? for more information.

Breastfeeding after six months: Benefits for mums

Extended breastfeeding isn’t just brilliant for your baby – it’s also great for you. By continuing breastfeeding beyond six months, you lower your lifelong risk of developing heart disease,27 type 2 diabetes28 and cancers of the breast,29 ovaries30 and uterus.”31 And breastfeeding mums often find their periods don’t return for many months – and possibly for as long as two years.32

“The desire to get back to their pre-pregnancy body weight is a significant one for many mums,” says Dr Mitoulas. “One study showed that a mother’s body mass index (BMI) is 1% lower for every six months of breastfeeding.”24

Not to mention that after six months, breastfeeding is very convenient. Your breasts produce the right amount of milk when they need to and you don’t have to clean equipment or take anything with you when going out. You may also find you’re increasingly only feeding at times that fit your routine, such as before work, after childcare pick-up, and at bedtime. And even if you’re back at work, you can use a breast pump to express milk for your baby so he can continue enjoying the advantages.

And even if you’re back at work, you can use a breast pump to express milk for your baby so he can continue enjoying the advantages.

With so many potential benefits, it’s perhaps not surprising a growing number of mums are choosing to practise ‘natural-term’ or ‘full-term’ breastfeeding and letting their child decide the right time to stop.

References

1 World Health Organization. Health topics: Breastfeeding [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018 [Accessed: 26.03.2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/breastfeeding/en/

2 Innocenti Research Centre. 1990–2005 Celebrating the Innocenti Declaration on the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding: past achievements, present challenges and the way forward for infant and young child feeding. Florence: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2005. 38 p.

3 Dettwyler KA. When to wean: biological versus cultural perspectives. Clin Obstet Gyecol. 2004;47(3):712-723.

4 1,000 Days. [Internet] Washington DC, USA; 2018. Available from: https://thousanddays.org

Available from: https://thousanddays.org

5 TED. TEDWomen: What we don’t know about mother’s milk [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: TED Conferences LLC; 2016. [Accessed 26.03.2018]. Available from www.ted.com/talks/katie_hinde_what_we_don_t_know_about_mother_s_milk/reading-list

6 Kent JC et al. Breast volume and milk production during extended lactation in women. Exp Physiol. 1999;84(2):435-447.

7 Kuo AA et al. Introduction of solid food to young infants. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(8):1185-1194.

8 Dewey, KG. Nutrition, growth, and complementary feeding of the breastfed infant. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48(1):87-104.

9 Bener A et al. Does prolonged breastfeeding reduce the risk for childhood leukemia and lymphomas? Minerva Pediatr. 2008;60(2):155-161.

10 Bjerregaard LG et al. Breastfeeding duration in infancy and adult risks of type 2 diabetes in a high‐income country. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;e12869.

11 Singhal A et al. Infant nutrition and stereoacuity at age 4–6 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):152-159.

Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):152-159.

12 Peres KG et al. Effect of breastfeeding on malocclusions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(S467):54-61.

13 Horta BL et al. Long‐term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(S467):30-37.

14 Howie PW et al. Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. BMJ. 1990;300(6716):11-16.

15 Ladomenou F et al. Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(12):1004-1008.

16 Sankar MJ et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta paediatr. 2015;104(S467):3-13.

17 Lönnerdal B. Bioactive proteins in breast milk. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49(S1):1-7.

18 Gridneva Z et al. Effect of human milk appetite hormones, macronutrients, and infant characteristics on gastric emptying and breastfeeding patterns of term fully breastfed infants. Nutrients. 2016;9(1):15.

Nutrients. 2016;9(1):15.

19 Field CJ. The immunological components of human milk and their effect on immune development in infants. J Nutr. 2005;135(1):1-4.

20 Hassiotou F, Hartmann PE. At the dawn of a new discovery: the potential of breast milk stem cells. Adv Nutr. 2014;5(6):770-778.

21 Cregan MD et al. Identification of nestin-positive putative mammary stem cells in human breastmilk. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;329(1):129-136.

22 Victora CG et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475-490.

23 Heikkilä K et al. Breast feeding and child behaviour in the Millennium Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):635-642.

24 Oddy WH et al. The long-term effects of breastfeeding on child and adolescent mental health: a pregnancy cohort study followed for 14 years. J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):568-574.

25 Ballard O, Morrow AL. Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(1):49-74.

2013;60(1):49-74.

26 Hassiotou F et al. Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. Clin Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

27 Peters SA et al. Breastfeeding and the risk of maternal cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of 300 000 Chinese women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(6):e006081.

28 Horta BL et al. Long‐term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(S467):30-37.

29 Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50 302 women with breast cancer and 96 973 women without the disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9328):187-195.

30 Li DP et al. Breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(12):4829-4837.

2014;15(12):4829-4837.

31 Jordan SJ et al. Breastfeeding and endometrial cancer risk: an analysis from the epidemiology of endometrial cancer consortium. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(6):1059-1067.

32 Howie PW. Breastfeeding: a natural method for child spacing. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165(6):1990-1991.

Diet for a 4-6 month old baby

Your baby is already 4 months old. He has noticeably grown up, become more active, is interested in objects that fall into his field of vision, carefully examines and reaches for them. The emotional reactions of the child have become much richer: he joyfully smiles at all the people whom he often sees more and more often, makes various sounds.

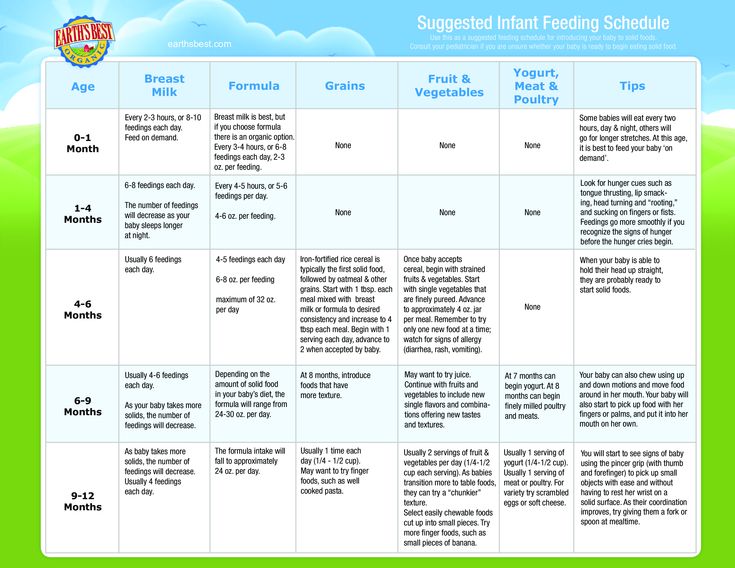

You are still breastfeeding your baby or have had to switch to mixed or formula feeding. The child is actively growing, and only with breast milk or infant formula, he can no longer always get all the necessary nutrients. And that means it's time to think about complementary foods.

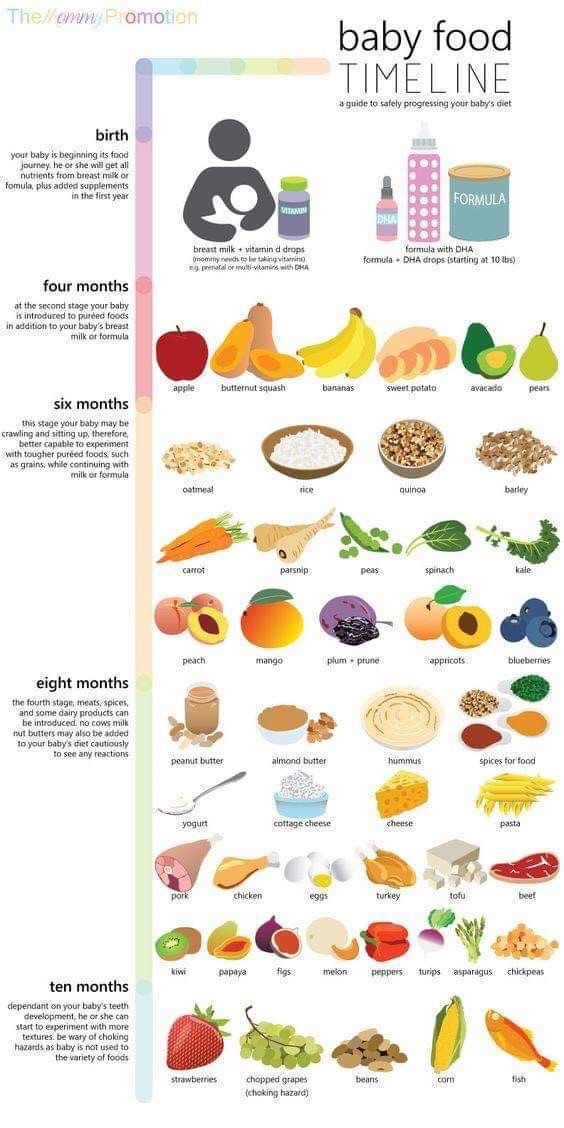

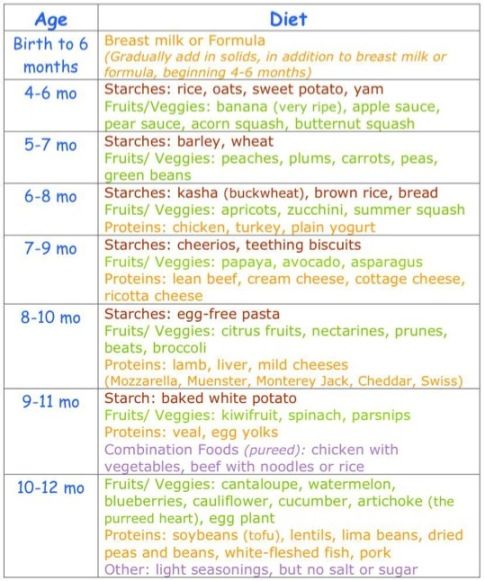

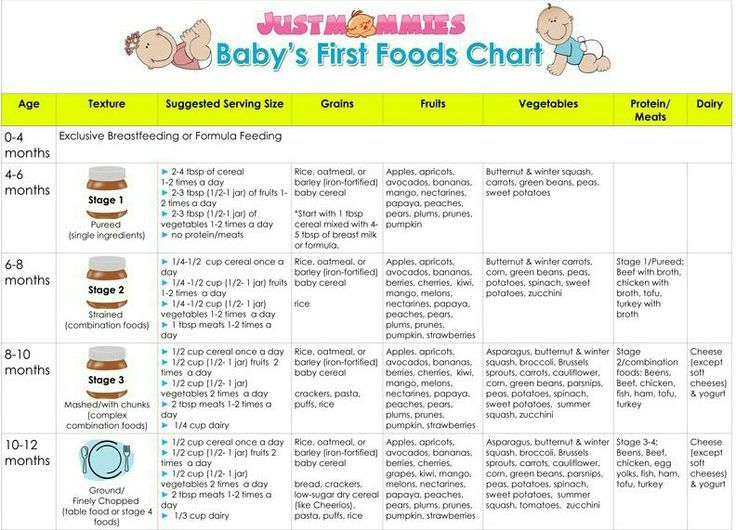

The optimal time to start its introduction is between 4 and 6 months, regardless of whether the baby is receiving breast milk or formula. This is the time when children respond best to new foods. Up to 4 months, the child is not yet ready to perceive and digest any other food. And with the late introduction of complementary foods - after 6 months, children already have significant deficiencies of individual nutrients and, first of all, micronutrients (minerals, vitamins, long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, etc.). In addition, toddlers at this age often refuse new foods, they have delayed development of chewing skills for thick foods, and inadequate eating habits are formed. It is important to know that, no matter how strange it may seem at first glance, with a delayed appointment of complementary foods, allergic reactions more often occur on them.

When is it advisable to introduce complementary foods as early as 4 months, and when can you wait until 5.5 or even 6 months? To resolve this issue, be sure to consult a pediatrician.

As a rule, at an earlier age (4 - 4.5 months), complementary foods are introduced to children at risk of developing iron deficiency anemia, as well as children with insufficient weight gain and with functional digestive disorders.

The optimal time to start complementary foods for a healthy baby is between 5 and 5.5 months of age.

The World Health Organization recommends that breastfed babies should be introduced to complementary foods from 6 months of age. From the point of view of domestic pediatricians, which is based on extensive practical experience and scientific research, this is possible only in cases where the child was born on time, without malnutrition (since in these cases the mineral reserves are very small), he is healthy, grows well and develops. In addition, the mother should also be healthy, eat well and use either specialized enriched foods for pregnant and lactating women, or vitamin and mineral complexes in courses. Such restrictions are associated with the depletion of iron stores even in a completely healthy child by 5-5.5 months of age and a significant increase in the risk of anemia in the absence of complementary foods rich or fortified with iron. There are other deficits as well.

The first complementary food can be vegetable puree or porridge, fruit puree is better to give the baby later - after tasty sweet fruits, children usually eat vegetable puree and cereals worse, often refuse them altogether.

Where is the best place to start? In cases where the child has a tendency to constipation or he puts on weight too quickly, preference should be given to vegetables. With a high probability of developing anemia, unstable stools and small weight gains - from baby cereals enriched with micronutrients. And if you started introducing complementary foods with cereals, then the second product will be vegetables and vice versa.

If the first complementary food is introduced at 6 months, it must be baby porridge enriched with iron and other minerals and vitamins, the intake of which with breast milk is no longer enough.

Another important complementary food product is mashed meat. It contains iron, which is easily absorbed. And adding meat to vegetables improves the absorption of iron from them. It is advisable to introduce meat puree to a child at the age of 6 months. Only the daily use of children's enriched porridge and meat puree can satisfy the needs of babies in iron, zinc and other micronutrients.

It is advisable to introduce meat puree to a child at the age of 6 months. Only the daily use of children's enriched porridge and meat puree can satisfy the needs of babies in iron, zinc and other micronutrients.

But it is better to introduce juices later, when the child already receives the main complementary foods - vegetables, cereals, meat and fruits. After all, complementary foods are needed so that the baby receives all the substances necessary for growth and development, and there are very few in their juices, including vitamins and minerals.

Juices should not be given between feedings, but after the child has eaten porridge or vegetables with meat puree, as well as for an afternoon snack. The habit of drinking juice between meals leads to frequent snacking in the future, a love of sweets is instilled, children have more tooth decay and an increased risk of obesity.

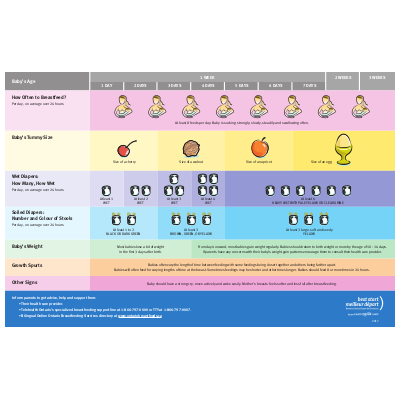

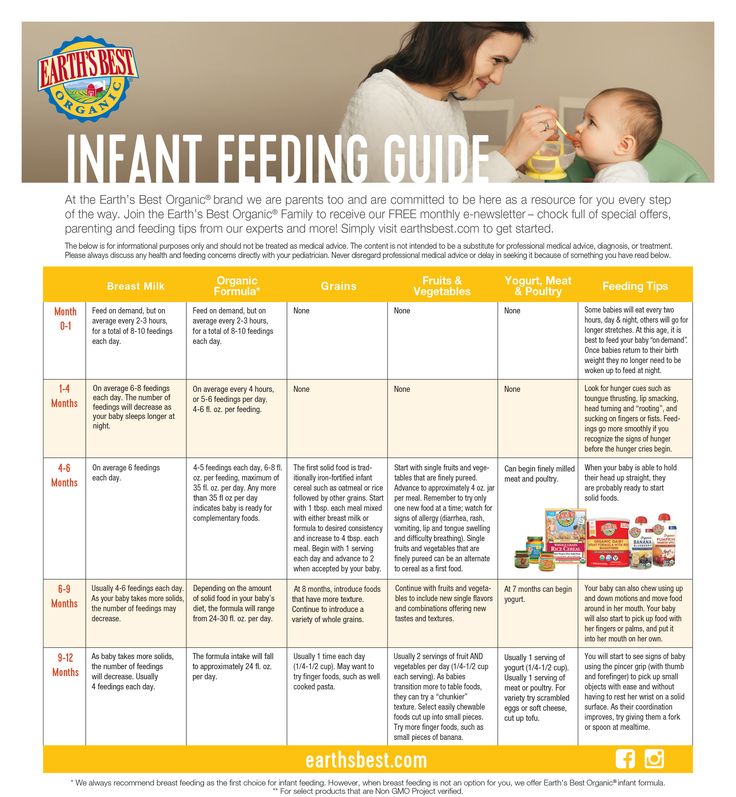

With the start of the introduction of complementary foods, the child is gradually transferred to a 5-time feeding regimen.

Rules for the introduction of complementary foods:

- preference should be given to baby products of industrial production, they are made from environmentally friendly raw materials, have a guaranteed composition and degree of grinding

- Complementary foods should be offered to the baby by spoon at the start of feeding, before breastfeeding (formula feeding)

- the volume of the product increases gradually, starting with ½ - 1 spoon, and in 7 - 10 days we bring it to the age norm, subsequent products within the same group (cereals from other cereals or new vegetables)

- can be entered faster, in 5 - 7 days

- start introduction with monocomponent products

- it is undesirable to give a new product in the afternoon, it is important to follow how the child reacts to it

- do not introduce new products in the event of acute illnesses, as well as before and immediately after prophylactic vaccination (should be abstained for several days)

When introducing a new type of complementary food, first try one product, gradually increasing its amount, and then gradually “dilute” this product with a new one. For example, vegetable complementary foods can be started with a teaspoon of zucchini puree. During the week, give the baby only this product, gradually increasing its volume. After a week, add a teaspoon of mashed broccoli or cauliflower to the zucchini puree and continue to increase the total volume every day. Vegetable puree from three types of vegetables will be optimal. The portion should correspond to the age norm. Over time, you can replace the introduced vegetables with others faster.

For example, vegetable complementary foods can be started with a teaspoon of zucchini puree. During the week, give the baby only this product, gradually increasing its volume. After a week, add a teaspoon of mashed broccoli or cauliflower to the zucchini puree and continue to increase the total volume every day. Vegetable puree from three types of vegetables will be optimal. The portion should correspond to the age norm. Over time, you can replace the introduced vegetables with others faster.

After the introduction of one vegetable (bringing its volume to the required amount), you can proceed to the intake of porridge, and diversify the vegetable diet later.

If the child did not like the dish, for example, broccoli, do not give up and continue to offer this vegetable in a small amount - 1-2 spoons daily, you can not even once, but 2-3 times before meals, and after 7 - 10, and sometimes 15 days, the baby will get used to the new taste. This diversifies the diet, will help to form the right taste habits in the baby.

Spoon-feeding should be done with patience and care. Forced feeding is unacceptable!

In the diet of healthy children, porridge is usually introduced after vegetables (with the exception of healthy breastfed children, when complementary foods are introduced from 6 months). It is better to start with dairy-free gluten-free cereals - buckwheat, corn, rice. At the same time, it is important to use porridge for baby food of industrial production, which contains a complex of vitamins and minerals. In addition, it is already ready for use, you just need to dilute it with breast milk or the mixture that the baby receives.

Children suffering from food allergies are introduced complementary foods at 5-5.5 months. The rules for the introduction of products are the same as for healthy children, in all cases it is introduced slowly and begins with hypoallergenic products. Be sure to take into account individual tolerance. The difference is only in the correction of the diet, taking into account the identified allergens. From meat products, preference should first be given to mashed turkey and rabbit.

From meat products, preference should first be given to mashed turkey and rabbit.

Diets for different age periods

Explain how you can make a diet, it is better to use a few examples that will help you navigate in compiling a menu specifically for your child.

From 5 months, the volume of one feeding is on average 200 ml.

Option 1.

If your baby started receiving complementary foods from 4-5 months, then at 6 months his diet should look like this:

| I feeding 6 hours | Breast milk or VHI* | 200 ml |

| II feeding 10 hours | Dairy-free porridge** Supplementation with breast milk or VHI* | 150 g 50 ml |

| III feeding 14 hours | Vegetable puree Meat puree Vegetable oil Supplemental breast milk or VHI* | 150 g 5 - 30 g 1 tsp 30 ml |

| IV feeding 18 hours | Fruit puree Breast milk or VHI* | 60 g 140 ml |

| V feeding 22 hours | Breast milk or VHI* | 200 ml |

* - infant formula

** - diluted with breast milk or VHI

Option 2.

* - infant formula Option 3. : ** - diluted with breast milk Up to 7 months, increase the volume of porridge and vegetable puree to 150 g and introduce fruit puree. The materials were prepared by the staff of the Healthy and Sick Child Nutrition Laboratory of the National Research Center for Children's Health of the Ministry of Health of Russia and are based on the recommendations given in the National Program for Optimizing the Feeding of Children in the First Year of Life in the Russian Federation, approved at the XV Congress of Pediatricians of Russia (02.2009d.) Pediatricians around the world, including experts from the World Health Organization, unanimously believe that the introduction of complementary foods should be carried out in the interval of 4-6 months. Early introduction of complementary foods (up to 4 months). fraught with the development of allergic reactions and indigestion. Late introduction of complementary foods, from 7 months, can lead to a deficiency in the child's diet of essential nutrients, an iron deficiency state at the age of 9-10 months, eating disorders, delayed development of chewing skills and swallowing of thick foods. With the normal development of the child and the absence of signs of iron deficiency anemia, complementary foods can be introduced from 6 months. This applies to both formula-fed and breast-fed babies. Signs that a baby is ready to breastfeed include It is important to remember that a child’s lack of teeth and the ability to sit are not signs of a baby’s unpreparedness for eating thick food. It is very important to understand the main goals of the introduction of complementary foods: In no case should the introduction of complementary foods be of a violent nature, since this will not only not contribute to the development of a child’s food interest, but can also lead to a complete refusal of the baby from complementary foods, which will destroy the main goals of complementary foods. The first product of complementary foods, regardless of the start date of the introduction of complementary foods and the type of feeding of the baby (breast or artificial), should be energy-intensive foods: porridge, or vegetable puree. If the child has a liquefied or unstable stool, and there is also a lack of body weight, then it is better to choose porridge as the first complementary food. After 3-4 days from the beginning of the introduction of porridge, butter can be gradually added to it (up to 5 g per serving of porridge in 150 g) If the child has a tendency to constipation, then it is better to choose vegetable marrow puree as the first complementary food, which can have a mild laxative effect on the child's stool. Starting from the 3-4th day of the introduction of vegetable puree, vegetable oil can be gradually added to it (up to 5 g per serving of vegetables in 150 g) The first cereals can be buckwheat, rice or corn. The first vegetable puree can be zucchini, broccoli, or cauliflower. Later, kohlrabi, potatoes, green beans, white cabbage, green peas, celery can be introduced into the diet. The third type of complementary foods can be fruit puree from apples, pears or bananas. Later, you can introduce mashed apricot, peach. For starters, fruit puree may not be given to the child separately, but it is better to mix it with cereal or vegetables so that the child does not begin to prefer the sweet taste of fruits. When the amount of fruit puree reaches 50 g or more, it can also be given separately, for example, after the child has eaten porridge or cottage cheese. Juices should not be the first feeding, in addition, they can not be introduced into the baby's first year of life at all, given their sweet taste and low nutritional value. The introduction of a new product should be gradual. Important! If on the 5-7th day of the introduction of a new product, the baby still cannot eat 100-150 ml of porridge or puree at once, then this amount can be divided into 2 doses, for example, give 100 ml of porridge in the morning and 50 ml in the evening. From the second week of the introduction of a new product, one milk feeding can be completely replaced with complementary foods. If we start complementary foods with vegetable puree, then the schedule might look something like this: 2 weeks From the second week, you need to start introducing dairy-free porridge. 3 week From the third week, you need to start introducing meat puree, which is most convenient to add to vegetable puree 4 week From the fourth week, you can introduce fruit puree, which is most convenient to add to porridge I feeding

6 hours Breast milk or VHI* 200 ml II feeding

10 hours Dairy-free porridge**

Fruit puree 150 g

20 g III feeding

14 hours Vegetable puree

Meat puree Vegetable oil

Fruit juice 150 g

5 - 30 g

1 tsp

60 ml IV feeding

18 hours Fruit puree

Breast milk or VHI* 40 g

140 ml V feeding

22 hours Breast milk or VHI* 200 ml

** - diluted with breast milk or VMS

I feeding

6 hours Breast milk II feeding

10 hours Dairy-free porridge**

Breast milk supplement 100 g III feeding

14 hours Vegetable puree

Meat puree Vegetable oil

Breast milk supplement 100 g

5 - 30 g

1 tsp IV feeding

18 hours Breast milk V feeding

22 hours Breast milk

Complementary foods at 6 months | Useful tips from the Tyoma brand

How to start introducing complementary foods at 6 months of age?

What products are better to give preference to at 6 months?

Kashi

They must be dairy-free and can be diluted with water or breast milk, or the mixture that the baby eats. Later, you can introduce oatmeal and millet porridge

They must be dairy-free and can be diluted with water or breast milk, or the mixture that the baby eats. Later, you can introduce oatmeal and millet porridge Vegetables

Fruit

Juices

Basic rules for the introduction of complementary foods from 6 months

How to start the introduction of a new product?

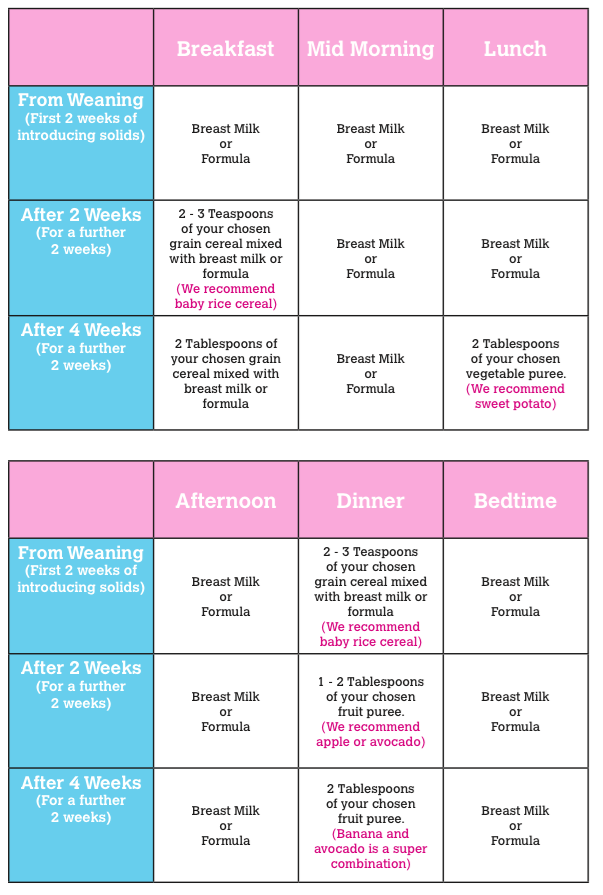

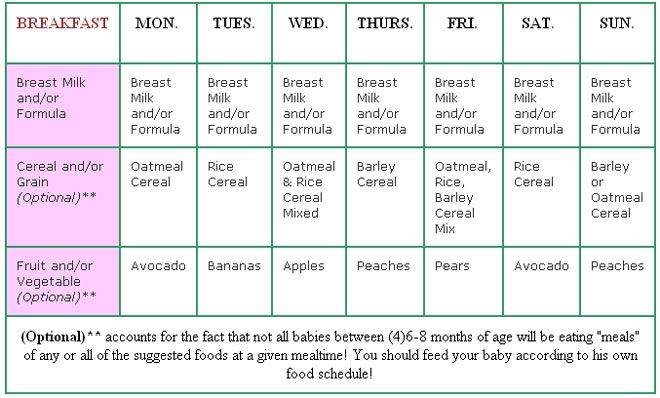

Approximate weekly feeding schedule

Vegetable oil 5 g Supplementary feeding with breast milk or infant formula up to 50 ml

Vegetable oil 5 g Supplementary feeding with breast milk or infant formula up to 50 ml