How many people die during child birth

Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020

- Data sources and methods

- References

- Suggested citation

- Table

- Figures

by Donna L. Hoyert, Ph.D., Division of Vital Statistics

PDF Version pdf icon[PDF – 426 KB]

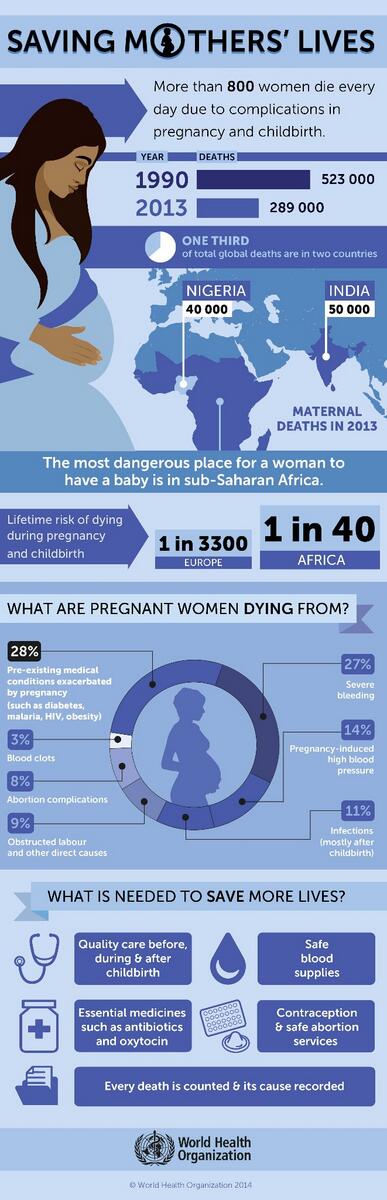

This report presents maternal mortality rates for 2020 based on data from the National Vital Statistics System. A maternal death is defined by the World Health Organization as, “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes” (1). Maternal mortality rates, which are the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, are shown in this report by age group and race and Hispanic origin.

This report updates a previous one that showed maternal mortality rates for 2018 and 2019 (2). In 2020, 861 women were identified as having died of maternal causes in the United States, compared with 754 in 2019 (3). The maternal mortality rate for 2020 was 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with a rate of 20.1 in 2019 (Table).

In 2020, the maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black women was 55.3 deaths per 100,000 live births, 2.9 times the rate for non-Hispanic White women (19.1) (Figure 1 and Table). Rates for non-Hispanic Black women were significantly higher than rates for non-Hispanic White and Hispanic women. The increases from 2019 to 2020 for non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women were significant. The observed increase from 2019 to 2020 for non-Hispanic White women was not significant.

Rates increased with maternal age. Rates in 2020 were 13.8 deaths per 100,000 live births for women under age 25, 22.8 for those aged 25–39, and 107.9 for those aged 40 and over (Figure 2 and Table). The rate for women aged 40 and over was 7.8 times higher than the rate for women under age 25. Differences in the rates between age groups were statistically significant. Among age groups, the increase in the rates between 2019 and 2020 for women aged 25–39 and 40 and over were statistically significant.

Data sources and methods

Data are from the National Vital Statistics System mortality file (4). Consistent with previous reports, the number of maternal deaths does not include all deaths occurring to pregnant or recently pregnant women, but only those deaths with the underlying cause of death assigned to International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision code numbers A34, O00–O95, and O98–O99. Maternal mortality rates are per 100,000 live births based on data from the National Vital Statistics System natality file. Maternal mortality rates fluctuate from year to year because of the relatively small number of these events, and possibly also due to issues associated with the reporting of maternal deaths on death certificates (3). Efforts to improve data quality are continuous, and these data will continue to be evaluated for possible errors.

References

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision.

2008 ed. 2009.

2008 ed. 2009. - Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2019. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:103855external icon.

- Hoyert DL, Miniño AM. Maternal mortality in the United States: Changes in coding, publication, and data release, 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 69 no 2. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020.

- Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu JQ, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief, no 427. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021.

Suggested citation

Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2020. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2022. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:113967external icon.

Table

Table. Number of live births, maternal deaths, and maternal mortality rates, by race and Hispanic origin and age: United States, 2018–2020

| Race and Hispanic origin and age | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ||||||

| Number of live births | Number of maternal deaths | Maternal mortality rate1 | Number of live births | Number of maternal deaths | Maternal mortality rate1 | Number of live births | Number of maternal deaths | Maternal mortality rate1 | |

| Total2 | 3,791,712 | 658 | 17. 4 4 | 3,747,540 | 754 | 20.1 | 3,613,647 | 861 | 23.8 |

| Under 25 | 907,782 | 96 | 10.6 | 877,803 | 111 | 12.6 | 825,403 | 114 | 13.8 |

| 25–39 | 2,756,974 | 458 | 16.6 | 2,739,976 | 544 | 19.9 | 2,658,445 | 607 | 22.8 |

| 40 and over | 126,956 | 104 | 81.9 | 129,761 | 98 | 75.5 | 129,799 | 140 | 107.9 |

| Non-Hispanic White3 | 1,956,413 | 291 | 14.9 | 1,915,912 | 343 | 17.9 | 1,843,432 | 352 | 19.1 |

| Under 25 | 391,829 | 41 | 10.5 | 374,129 | 49 | 13.1 | 348,666 | 40 | 11.5 |

| 25–39 | 1,504,888 | 207 | 13. 8 8 | 1,480,595 | 248 | 16.8 | 1,433,839 | 253 | 17.6 |

| 40 and over | 59,696 | 43 | 72.0 | 61,188 | 46 | 75.2 | 60,927 | 59 | 96.8 |

| Non-Hispanic Black3 | 552,029 | 206 | 37.3 | 548,075 | 241 | 44.0 | 529,811 | 293 | 55.3 |

| Under 25 | 176,243 | 27 | 15.3 | 169,853 | 32 | 18.8 | 159,541 | 46 | 28.8 |

| 25–39 | 358,276 | 137 | 38.2 | 360,206 | 179 | 49.7 | 351,648 | 198 | 56.3 |

| 40 and over | 17,510 | 42 | 239.9 | 18,016 | 30 | 166.5 | 18,622 | 49 | 263.1 |

| Hispanic | 886,210 | 105 | 11.8 | 886,467 | 112 | 12. 6 6 | 866,713 | 158 | 18.2 |

| Under 25 | 275,553 | 21 | 7.6 | 270,948 | 23 | 8.5 | 258,635 | 20 | 7.7 |

| 25–39 | 579,553 | 72 | 12.4 | 584,109 | 71 | 12.2 | 576,690 | 111 | 19.2 |

| 40 and over | 31,104 | 12 | * | 31,410 | 18 | * | 31,388 | 27 | 86.0 |

* Rate does not meet National Center for Health Statistics standards of reliability.

1Maternal mortality rates are deaths per 100,000 live births.

2Total includes race and origin groups not shown separately, including women of multiple races and origin not stated.

3Race groups are single race.

NOTES: Maternal deaths are those assigned to code numbers A34, O00–O95, and O98–O99 of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Maternal deaths occur while pregnant or within 42 days of being pregnant.

Maternal deaths occur while pregnant or within 42 days of being pregnant.

SOURCES: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality and Natality.

Figures

Figure 1. Maternal mortality rates, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2018–2020

image icon

1Statistically significant increase in rate from previous year (p < 0.05).

NOTE: Race groups are single race.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

Figure 2. Maternal mortality rates, by age group: United States, 2018–2020

image icon

1Statistically significant increase in rate from previous year (p < 0.05).

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

Maternal Mortality in the United States: A Primer

In 2017, at a time when maternal mortality was declining worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the U. S. was one of only two countries (along with the Dominican Republic) to report a significant increase in its maternal mortality ratio (the proportion of pregnancies that result in death of the mother) since 2000. While U.S. maternal deaths have leveled in recent years, the ratio is still higher than in comparable countries, and significant racial disparities remain.

S. was one of only two countries (along with the Dominican Republic) to report a significant increase in its maternal mortality ratio (the proportion of pregnancies that result in death of the mother) since 2000. While U.S. maternal deaths have leveled in recent years, the ratio is still higher than in comparable countries, and significant racial disparities remain.

Understanding the evidence on maternal mortality and its causes is a key step in crafting health care delivery and policy solutions at the state or federal level. This data brief draws on a range of recent and historical data sets to present the state of maternal health in the United States today.

Highlights

- The most recent U.S. maternal mortality ratio, or rate, of 17.4 per 100,000 pregnancies represented approximately 660 maternal deaths in 2018. This ranks last overall among industrialized countries.

- More than half of recorded maternal deaths occur after the day of birth.

- The maternal death ratio for Black women (37.

1 per 100,000 pregnancies) is 2.5 times the ratio for white women (14.7) and three times the ratio for Hispanic women (11.8).

1 per 100,000 pregnancies) is 2.5 times the ratio for white women (14.7) and three times the ratio for Hispanic women (11.8). - A Black mother with a college education is at 60 percent greater risk for a maternal death than a white or Hispanic woman with less than a high school education.

- Causes of death vary widely, with death from hemorrhage most likely during pregnancy and at the time of birth and deaths from heart conditions and mental health–related conditions (including substance use and suicide) most common in the postpartum period.

- State ratios vary widely: in 2018, some states reported more than 30 maternal deaths per 100,000 births, while others reported fewer than 15.

There are three commonly used measures of maternal deaths in the United States. It is important to note that, while they all capture some aspect of maternal deaths, they are not equivalent.

Pregnancy-associated mortality: Death while pregnant or within one year of the end of the pregnancy, irrespective of cause. This is the starting point for analyses of maternal deaths.

This is the starting point for analyses of maternal deaths.

Pregnancy-related mortality: Death during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy from: a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy. Used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to report U.S. trends, this measure is typically reported as a ratio per 100,000 live births. In this brief, when we discuss causes of maternal deaths and current rates, we will generally be using pregnancy-related mortality as our index.

Maternal mortality ratio: Death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes. Used by the World Health Organization in international comparisons, this measure is reported as a ratio per 100,000 live births. When we examine historical trends, we will be using maternal mortality as our index.

When we examine historical trends, we will be using maternal mortality as our index.

There are various causes of maternal mortality; deaths during delivery are significant but only a part of the problem. Slightly more than half (52%) of all deaths occur after the day of delivery, while almost a third occur during pregnancy. There have been considerable efforts to improve clinical care, but efforts that focus on the birth hospitalization will only solve a portion of the problem. To improve outcomes, it will also be critical to address causes of maternal mortality that arise during pregnancy (such as hypertension, or high blood pressure) and in the postpartum period (such as cardiomyopathy, or weakened heart muscle), through upgrades to women’s health care before, during, and after pregnancy.

For decades in the U.S. and around the world, maternal mortality dropped as women gained healthier living conditions, better maternity services, safer surgical procedures, and access to antibiotics. Then, 20 years ago, the U.S. maternal mortality ratio began to rise.

Then, 20 years ago, the U.S. maternal mortality ratio began to rise.

Systematic, comprehensive collection of data on maternal mortality in the U.S. began in the early 20th century in individual states. In 1915, the state data began to be compiled into a national estimate; by 1933, all states were participating and the nationally reported ratio was 619 deaths per 100,000 live births. By way of contrast, the ratio in 1927 for England and Wales was 411 per 100,000 and for Italy was 264 per 100,000.

For most of the 20th century, maternal mortality ratios dropped rapidly around the world with the introduction of healthier living conditions, improved maternity services, safer surgical procedures, and antibiotics. By 1960 the U.S. ratio was 37 per 100,000 live births. During the 1980s and into the 1990s, clinical interventions as well as public health efforts further reduced maternal mortality; it declined until the late 1990s, when it leveled off at about nine deaths per 100,000. After 1997, the U.S. ratio began rising again until 2008, when it plateaued at around 14 deaths per 100,000 births.

After 1997, the U.S. ratio began rising again until 2008, when it plateaued at around 14 deaths per 100,000 births.

The focus on improving maternity care in hospitals has had consequences, for example by diminishing the importance of community-based care and overlooking persistent racial and ethnic disparities.

Black–white disparities in maternal mortality have existed since the beginning of the collection of such data. In 1915, the maternal mortality ratio for Black mothers (1,065 per 100,000 births) was 1.8 times that of white mothers (601).

As white maternal mortality ratios declined more rapidly than those for Black mothers after World War II, the disparity increased until the maternal mortality ratio for Black mothers was four times that of white mothers. Since the early 1970s, Black mothers have been three to four times more likely to die than white mothers. In the recently reported 2018 maternal mortality data, the Black–white disparity was 2.5 (37.1 for Black mothers vs 14. 7 for whites) — the same as the disparity seen in the 1940s.

7 for whites) — the same as the disparity seen in the 1940s.

This figure, drawing on a decade (2007–16) of data on causes of maternal deaths broken down by race/ethnicity, illustrates the diversity of factors that contribute to maternal deaths in different groups. The percentages represent the distribution of causes of deaths within each group.

The same study also reported widely disparate pregnancy-related mortality ratios for each group, specifically: white (12.7), Black (40.8), American Indian/Alaska Native (29.7), Asian Pacific Islander (13.5), and Hispanic (11.5). For example, hemorrhage (severe bleeding) is a cause of death most frequently seen in pregnancy and at the time of birth. It was the leading cause of death among American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) and Asian Pacific Islanders (APIs), accounting for twice the proportion of deaths as seen among white or Black people. Cardiomyopathy, most commonly seen in the postpartum period, accounts for one of seven deaths among Black and AIAN people, but less than half that proportion among Hispanic and API people.

To reduce such disparities, it is critical to understand the particular risks that women face and then address all relevant factors, including access to treatment before and after birth, the quality of clinical care, the effects of structural racism, and social determinants of health.

While educational advancement is typically seen as protective in terms of health, that’s not the case for Black mothers. Education exacerbates rather than mitigates Black–white differences in maternal deaths. Five times as many Black mothers with a college education die as white mothers with a college education. Mortality ratios for white mothers decrease with higher education, but the difference in mortality risk for a Black mother with less than a high school education and one with a college degree is minimal. This leads to the startling finding that maternal deaths are more common among Black mothers with a college education than they are among white mothers with less than a high school education (40. 2 vs. 25.0). Mortality ratios for Hispanic mothers decrease slightly with education but are generally lower at each level.

2 vs. 25.0). Mortality ratios for Hispanic mothers decrease slightly with education but are generally lower at each level.

It is important to understand the clinical causes of pregnancy-related mortality. According to a recent CDC report, the majority relate to cardiovascular conditions such as heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy) (11%), blood clots (9%), high blood pressure (8%), stroke (7%), and a category combining other cardiac conditions (15%). Infection (13%) and severe postpartum bleeding (11%) are also leading causes. When many of these conditions are identified early, there are clinical interventions that can save lives. And a number of these conditions, particularly cardiomyopathy, occur up to a year after childbirth.

Improvements in hospital care have, according to a recent study, decreased the number of maternal deaths occurring at the time of birth hospitalization. Pregnancy-related mortality ratios associated with hospital care (such as hemorrhage, eclampsia, and infection) have declined in recent years.

In addition to hospital-focused interventions, key efforts involve identifying higher-risk women earlier, enrolling women in insurance, and keeping them in care after childbirth. Additionally, many new mothers feel torn between the economic pressure to return to work and the need to focus primarily on their infant’s health, perhaps at the cost of their own care.

The causes of maternal death vary considerably and depend on when mothers die. These data are based on a report from maternal mortality review committees.

During pregnancy, hemorrhage and cardiovascular conditions are the leading causes of death. At birth and shortly after, infection is the leading cause. In the postpartum period, often during the time when new parents are out of the hospital and beyond the traditional six- or eight-week post-pregnancy visit, cardiomyopathy (weakened heart muscle) and mental health conditions (including substance use and suicide) are identified as leading causes.

The diversity of causes at different times throughout pregnancy until one year postpartum can best be addressed through integrated care delivery models. Those that leverage telehealth, midwives, and doulas can improve access to care. Since almost 7 percent of non-Hispanic Black women in 2018 did not start prenatal care until their third trimester, and an additional 3 percent report no prenatal care at all, efforts to enroll women into insurance early in pregnancy would be an appropriate place to begin. The large proportion of deaths occurring after birth also suggests too many mothers are lost to care after they’ve given birth, a problem exacerbated by current Medicaid policies that drop expanded coverage for pregnant women 60 days after birth.

Those that leverage telehealth, midwives, and doulas can improve access to care. Since almost 7 percent of non-Hispanic Black women in 2018 did not start prenatal care until their third trimester, and an additional 3 percent report no prenatal care at all, efforts to enroll women into insurance early in pregnancy would be an appropriate place to begin. The large proportion of deaths occurring after birth also suggests too many mothers are lost to care after they’ve given birth, a problem exacerbated by current Medicaid policies that drop expanded coverage for pregnant women 60 days after birth.

Given that large-scale policy changes may take longer to implement, there are also more immediate practice changes that can reduce disparities and save lives in the short term; these include increasing support for programs like community-based doulas and wraparound services, which have been found to act as effective buffers against larger social determinants of health.

The varying conditions require different approaches to treatment. Therefore, providing women with optimal care, including mental health care, throughout the 21 months from conception through the year after they have given birth is essential.

Therefore, providing women with optimal care, including mental health care, throughout the 21 months from conception through the year after they have given birth is essential.

State maternal mortality ratios vary widely. The recent report on maternal deaths in 2018 included ratios for the 25 states reporting at least 10 maternal deaths. A cluster of states in the South (Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Oklahoma) reported ratios of greater than 30 per 100,000 live births, while California, Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania all reported ratios less than half the figures in those states.

It is striking that the data are missing for approximately half of all U.S. states and territories. It is expected that with subsequent annual reports, multiple years can be combined to enable the comparison of all states.

Black women are more likely than white women to report that their concerns and preferences regarding birth were disregarded; women with Medicaid coverage reported inadequate postpartum care and support.

Listening to Mothers is a series of national surveys fielded by the nonprofit National Partnership for Women and Families. Below is a summary of some of the key findings from the Listening to Mothers 2011–12 survey, as well as a California survey conducted in 2016, about the experiences of mothers who had hospital births in the United States.

Compared with white women, non-Hispanic Black women were more likely to report:

- Being treated unfairly and with disrespect by providers because of their race

- Not having decision autonomy during labor and delivery

- Feeling pressured to have a cesarean section

- Not exclusively breastfeeding at one week and six months.

Compared with women with private health insurance, women with Medicaid coverage were more likely to report:

- No postpartum visit

- Returning to work within two months of birth

- Less postpartum emotional and practical support at home

- Not having decision autonomy during labor and delivery

- Being treated unfairly and with disrespect by providers because of their insurance status

- Not exclusively breastfeeding at one week and six months.

As these findings illustrate, different women have different experiences with maternity care, childbirth, and parenting. For example, both Black women and those with Medicaid coverage were less likely than white women and those with private health coverage to say they had autonomy about childbirth decisions and were treated with respect by their providers.

When we consider causes of racial and other disparities in maternal mortality, it is essential to consider women’s interactions with the maternity care system and understand how bias and racism manifest in these experiences. Because experiences of pregnancy and parenthood differ by race and insurance coverage, our health care systems need to address structural factors — including racism and bias — that affect treatment while meeting the full needs of all pregnant and birthing people.

Discussion

As these charts show, relatively high maternal mortality ratios in the U.S. as compared with other countries, and disparities between Black and white women, are not new problems, nor are they improving. Even if you looked just at non-Hispanic white women in cross-national comparisons of maternal mortality, the U.S. would still be in last place. Even with varying ways to measure maternal mortality, the U.S. does not perform well on any analysis of this sentinel measure of a society’s health.

Even if you looked just at non-Hispanic white women in cross-national comparisons of maternal mortality, the U.S. would still be in last place. Even with varying ways to measure maternal mortality, the U.S. does not perform well on any analysis of this sentinel measure of a society’s health.

Preventing maternal mortality is complicated by the multifactorial nature of the problem. The causes vary across racial and ethnic groups as well as timing — whether during pregnancy, at birth, or postpartum. And a woman’s chance of dying in childbirth is more than twice as high in some states.

The fact that the U.S. has the highest maternal mortality ratio among wealthy countries even when we limit the U.S. data only to white women suggests that our maternal health care system needs dramatic change. The U.S. has to intentionally focus on disparities between Black and white women, in particular by naming and seeking to reduce the impacts of structural racism.

Structural racism leads to disparities in income, housing, safety, education, and other circumstances that are associated with poorer health and increased rates of chronic disease. These, in turn, place Black women at greater risk than white women of pregnancy-related deaths from cardiomyopathy and hypertension, among other causes.

These, in turn, place Black women at greater risk than white women of pregnancy-related deaths from cardiomyopathy and hypertension, among other causes.

Racism in the health care sector compounds the issue, with Black women less likely to have access to treatment and receive good-quality care. And the intersection of sexism and racism can mean women of color are not listened to or respected by their providers, contributing to preventable morbidity and mortality due to delayed diagnosis or care. This has been reported by women in multiple surveys and illustrated by the high-profile cases of Serena Williams, Shalon Irving, and Kira Johnson.

Moreover, although recent efforts to improve hospital maternity care have been valuable, only a third of pregnancy-related deaths occur at the time of birth. We need to improve women’s health services before and after pregnancy — not just at the time of birth.

Policies are also needed to promote continuous health insurance coverage before and after pregnancy. In particular, the large proportion of maternal deaths that occur after childbirth suggests that too many women are losing connections to health care after giving birth.

In particular, the large proportion of maternal deaths that occur after childbirth suggests that too many women are losing connections to health care after giving birth.

High maternal mortality in the U.S. is not the result of any single factor, and reducing it will require an integrated effort involving policy and practice changes to improve hospital and community care for all women while advancing racial equity.

How We Conducted This Study

The figures cited in this study are based on data from a wide range of contemporary and historical sources. The historical data are drawn from early national vital statistics reports. The current breakdowns of maternal death by timing of deaths and causes of death are from the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System and the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application, both developed by CDC. The 2018 state ratios were published by the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System. The Listening to Mothers survey methods and results are all available from the National Partnership for Women and Families website.

The National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) provides the official reports of maternal mortality, and in 2020, after a decade-long hiatus, reported a national ratio (17.4 deaths per 100,000 births) for 2018. Meanwhile, the CDC has been publishing a pregnancy-related mortality ratio for more than two decades. However, the CDC data cannot be used to make international comparisons because the CDC reports deaths up to one year postpartum, while other countries report deaths that occur up to 42 days postpartum. While the CDC data could be truncated at 42 days for comparison, the CDC is not allowed to report those rates, because the NVSS is the only governmental body allowed to report an official maternal mortality ratio. Finally, CDC has developed the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application system, for which data from states’ maternal mortality review committees are gathered to produce multistate reports on maternal deaths.

The major limitation in examining maternal mortality is that there is no single national system in the U. S. for collecting maternal mortality data. Rather, there is a federal system wherein deaths are reported at the local and state levels and those reports conveyed to federal officials. Therefore, the system relies on the quality of data collected locally and the quality-control processes for converting those reports into national data. Documentation and analysis of maternal mortality over time have been hampered by limited funding, changing definitions, and inconsistent reporting by states. These shortcomings have resulted in notable gaps in our understanding of the problem, including the degree of difference in maternal mortality between urban and rural areas, though there is considerable evidence reporting the growing problem of gaps in maternal health services in rural areas.

S. for collecting maternal mortality data. Rather, there is a federal system wherein deaths are reported at the local and state levels and those reports conveyed to federal officials. Therefore, the system relies on the quality of data collected locally and the quality-control processes for converting those reports into national data. Documentation and analysis of maternal mortality over time have been hampered by limited funding, changing definitions, and inconsistent reporting by states. These shortcomings have resulted in notable gaps in our understanding of the problem, including the degree of difference in maternal mortality between urban and rural areas, though there is considerable evidence reporting the growing problem of gaps in maternal health services in rural areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ebere Oparaeke, M.P.H., and Ruby Barnard Mayers, M.P.H., for research and technical support, and Jodie Katon, Ph.D., for her careful review.

Why is childbirth difficult and dangerous?

- Colin Barras

- BBC Earth

Photo credit: Blend Images / Alamy

Scientists have long believed that the cause of difficult labor in women is upright posture. However, recent research shows that this is not the only issue.

However, recent research shows that this is not the only issue.

The birth of a child is a long and painful process, and sometimes deadly. The World Health Organization estimates that about 830 women die every day due to complications during pregnancy and childbirth. And this is already 44% lower than 1990 years.

"These statistics are astounding," says Jonathan Wells of University College London, who studies infant nutrition. "Female mammals have never had to pay such a high price for offspring."

But why is childbirth so dangerous for women? And what can we do to reduce the death rate?

Image copyright Juan Manuel Borrero / naturepl.com

Image captionHominins have walked upright for millions of years

Scientists first began to think about the issue of childbirth in women in the middle of the 20th century. They quickly found an explanation. Problems with childbearing began in the early members of our evolutionary branch - hominins, who split from other primates about seven million years ago.

These were animals that had little in common with us, except, perhaps, for the fact that already in those distant times they, like us, walked on two legs.

Bipedalism caused the hominin skeleton to change - it stretched out, and this affected the shape of the animal's pelvis.

In most primates, the birth canal is relatively straight. Among the hominins, they soon changed quite markedly. The hips became narrower, and the birth canal curved.

Thus, at the dawn of our history, hominin babies had to twist and turn in order to squeeze through the birth canal. This made the birth process very difficult.

image copyrightP. Plailly/E. Daynes/Science Photo Library

Photo caption,About two million years ago, our hominin ancestors began to lose their ape-like features and become more like modern humans

But things soon got worse.

About two million years ago, our hominin ancestors began to change again. They lost their ape-like features and became more like modern humans. Their bodies stretched a little more, their arms shortened, and their brains noticeably increased. And this last detail was bad news especially for women.

They lost their ape-like features and became more like modern humans. Their bodies stretched a little more, their arms shortened, and their brains noticeably increased. And this last detail was bad news especially for women.

It seems that evolution has begun to contradict itself. On the one hand, the pelvis of women had to narrow so that they could move on two legs, on the other hand, the babies they carried had an enlarged head, complicating the process of passing through the already narrow birth canal.

Childbirth has become an incredibly painful and potentially dangerous business, which it has remained to this day.

In 1960, anthropologist Sherwood Washburn called this theory the "obstetrical dilemma" and this explanation satisfied many scientists. But not everyone.

Photo credit, Science Photo Library/Alamy

Photo caption,Many women use pain relief during childbirth

Holly Dunsworth of the University of Rhode Island was initially fascinated by Washburn's theory, but later found that there was a lot that didn't add up.

According to the scientist, when the human brain increased two million years ago, the woman's body began to adapt to this, and the duration of pregnancy was noticeably reduced. This hypothesis seems quite logical.

Babies began to be born at an earlier stage of development, and anyone who has ever seen a newborn baby will attest to how helpless and vulnerable he is.

However, Dunsworth believes that this is simply not true.

image copyrightblickwinkel / Alamy

Caption before photo,Some animals, such as the eland (Taurotragus Oryx), can walk from birth

"Our babies are born quite large, and women's pregnancies last 37 days more than monkeys of the corresponding size", - explains the researcher.

The same applies to the size of the brain. Females give birth to babies with larger heads than females of other primates, with about the same body weight as females. And this means that the key points of Washburn's hypothesis are false.

And that's not all. The central assumption of the obstetrical dilemma is that the size and shape of the human pelvis, in particular in women, has changed greatly due to our habit of walking in an upright position.

However, if evolution were to "solve" the problem of childbirth in humans, it would certainly have already made women's hips and therefore the birth canal a little wider. In this case, our ability to walk on two legs would not suffer at all.

image copyrightVisuals Unlimited/naturepl.com

Caption before photo,Men's (left) and women's (right) pelvises

In 2015, researchers from Harvard University conducted an experiment that involved men and women with different body types. The researchers observed the physical activity of volunteers in the lab and found that those with wider hips had no trouble walking or running.

So, for purely energetic reasons, if nature made women's hips a little wider and thus facilitated childbearing, their ability to move would not deteriorate.

According to Dunsworth, the duration of pregnancy in women is not determined by the size of the baby's brain, as the obstetric dilemma suggests.

The fact is that a woman's body is simply not able to feed a fetus that requires too much energy for longer than 39-40 weeks. So, the reason for this length of pregnancy is not the difficulty of passing the child through the birth canal, as Washburn believed.

image copyrightCultura Creative RF / Alamy

Photo caption,The size of a full-term fetus on a tomography image

What then is the true cause of difficult labor in women? In 2012, researcher Jonathan Wells of University College London and his team began to study the history of childbirth and came to a startling conclusion. For most of human evolution, having a baby was apparently much easier.

From the little evidence that remains today, it follows that in early hunter-gatherer societies, childbirth was one of the smallest problems. Archaeologists find almost no skeletons of babies from this period, which indicates a relatively low mortality rate in early childhood.

Archaeologists find almost no skeletons of babies from this period, which indicates a relatively low mortality rate in early childhood.

But the situation changed dramatically a few thousand years ago, when people switched to a sedentary lifestyle. Many more newborn bones appear in the archaeological record from the early era of agricultural societies.

Photo credit, Volker Steger/4 Million Years of Man/Science Photo

Photo caption,Homo erectus, according to scientists, had less difficult births than modern women

Skip the podcast and continue

podcast

What was the cost

The main story of today, as our journalists explain

Issues

End of the podcast

The increase in infant mortality at the dawn of agriculture probably had several reasons.

On the one hand, living in more densely populated groups has led to an outbreak of infectious diseases to which newborns are more vulnerable. On the other hand, the diet of farmers with a high content of carbohydrates began to differ markedly from the diet of hunter-gatherers, which was dominated by proteins.

This affected the changes in body structure: as evidenced by archaeological finds, farmers were significantly shorter than hunter-gatherers. And scientists who study childbirth are well aware that the shape and size of a woman's pelvis directly depends on her height.

The smaller the woman, the narrower her hips, and consequently, the agricultural revolution has apparently complicated the process of childbearing. On the other hand, a carbohydrate-rich diet has made babies gain weight faster in the womb, and it is much more difficult to give birth to a large baby.

Image copyright Jose Antonio Penas/Science Photo Library

Photo captionFarming has once again changed our bodies

Thus, about 10,000 years ago, childbirth, which had been a relatively easy process for millions of years, suddenly became into a problem.

However, according to Holly Dunsworth, this is not the end of the story.

Scientific evidence shows that a woman's pelvis is at its most birth-friendly in late adolescence, when she reaches her peak fertility, and remains so until about 40 years of age. After that, it gradually changes its shape, preparing for menopause, and becomes less suitable for the birth of a child.

Scientists suggest that such changes make the birth of a child a little easier. And therefore, the question arises: if so many evolutionary factors influenced the characteristics of childbirth, maybe this process is still changing?

Photo copyright, Martin Valigursky/Alamy

Photo caption,Baby born by caesarean section

In December 2016, scientists Fischer and Mittereker published a sensational paper on this topic.

Previous studies have suggested that larger babies are more likely to survive, and that infant size at birth is somewhat hereditary.

The growth of the average size of the fetus is evolutionarily limited by the width of the female pelvis. But many babies are now being born by caesarean section. Consequently, Fischer and Mittereker suggest that in societies where caesarean section is gaining popularity, babies will be born ever larger.

Image copyright Tetra Images/Alamy

Theoretically, the number of cases of a baby too big to be born naturally could rise by 10-20% in just a few decades, at least in some parts of the world. Or, in other words, the bodies of women in these societies may evolve towards having larger babies.

So far, this is just an idea, and there is no convincing evidence for it, but it is a rather interesting assumption.

From the moment birth began to change under the influence of evolution, the size of the fetus has always been limited to a certain extent by the size of the birth canal. But perhaps for some children, it won't matter.

You can read the original of this article in English on the website BBC Earth.

How was childbirth from 1900 BC

Over the past 100 years, the death rate for women during childbirth has fallen by 99% and that of children by 90%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The goal was the same - to make sure that the child was born alive and healthy, and everything was in order with the mother. But you will be amazed at how much progress has been made in obstetric care since the beginning of the 20th century.

Grazia

Tags:

procedures

Diseases

C-section

Home birth

Genetic diseases

1900s

Most women gave birth at home—hospitals were still not widely available, and less than 5% of women in the US went to hospitals. Midwives helped to deliver, but wealthy families could already afford to call a doctor. Although anesthesia already existed, it was still very rarely used to anesthetize women in labor.

Midwives helped to deliver, but wealthy families could already afford to call a doctor. Although anesthesia already existed, it was still very rarely used to anesthetize women in labor.

In Russia things were about the same.

In 1897, at the celebration of the centenary of the Imperial Clinical Obstetric Institute of Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, its director, life obstetrician Dmitry Oskarovich Ott sadly noted: "98% of women in labor in Russia are still left without any obstetric care!"

“According to the data for 1908-1910, the number of deaths under the age of 5 years was almost 3/5 of the total number of deaths. The mortality rate of infants was especially high ”(Rashin“ The population of Russia for 100 years. 1811−1913 years).

1910s

Although most women still invite midwives (rarely doctors) to give birth, in 1914 the first “maternity hospital” already appeared. At the same time, doctors in the United States began using a method of pain relief called "Twilight Sleep" - the woman was given morphine or scopolamine. During childbirth, the woman fell into a deep sleep.

At the same time, doctors in the United States began using a method of pain relief called "Twilight Sleep" - the woman was given morphine or scopolamine. During childbirth, the woman fell into a deep sleep.

The problem was that the risk of death of the mother and child in this case increased.

At the same time, 90% of doctors have not even received a formal education.

In 1913, throughout Russia, there were only nine children's clinics and only 6824 beds in maternity hospitals. In large cities, coverage with inpatient obstetric care was only 0.6% [BME, vol. 28, 1962]. Most women continued to traditionally give birth at home with the help of relatives and neighbors or invited a midwife, a midwife, and only in difficult cases an obstetrician.

According to statistics, more than 30,000 women died each year during childbirth (mainly from sepsis and uterine ruptures). Mortality among children of the first year of life was also extremely high: an average of 273 children died per 1,000 births. According to official data from the beginning of the 20th century, only 50 percent of Moscow residents had the opportunity to receive professional medical care during childbirth in a hospital, and in the whole country this percentage was only 5.2% for urban residents and 1.2% in rural areas.

According to official data from the beginning of the 20th century, only 50 percent of Moscow residents had the opportunity to receive professional medical care during childbirth in a hospital, and in the whole country this percentage was only 5.2% for urban residents and 1.2% in rural areas.

The First World War and the revolution of 1917 that followed it slowed down the development of medicine in the country and caused degradation. The infrastructure was destroyed, and doctors were called to the front.

Changes also took place in Russia after the events of October 1917. First of all, the system of providing assistance to pregnant women and women in childbirth has changed.

By a special decree of 1918, the Department for the Protection of Motherhood and Infancy was established under the People's Commissariat of State Charity. This department was given the main role in solving the grandiose task - the construction of "a new building for the social protection of future generations. "

"

1920s

In almost all developed countries, a real revolution in obstetrics takes place during these years. Now the woman in labor was often visited by doctors, who, however, considered childbirth rather a “pathological process”. “Normal delivery”, without the intervention of doctors, has now become a rarity. Very often, doctors began to use the method of dilating the cervix, giving the woman ether in the second stage of labor, doing an episiotomy (dissection of the perineum), applying forceps, pulling out the placenta and medically forcing the uterus to contract.

Women of the USSR were now offered to be systematically observed in antenatal clinics, they were entitled to prenatal care and early diagnosis of pregnancy pathology. The authorities struggled with "social" diseases such as tuberculosis, syphilis and alcoholism.

In 1920, the RSFSR became the first country in the world to legalize abortion. A decree of 1920 allowed only a doctor in a hospital to perform an abortion; the mere desire of a woman was enough for the operation.

A decree of 1920 allowed only a doctor in a hospital to perform an abortion; the mere desire of a woman was enough for the operation.

December 1920 years The first meeting on the protection of motherhood and infancy decides on the priority of developing open-type institutions: nurseries, consultations, dairy kitchens. Since 1924, antenatal clinics begin to issue permission for free abortion.

The problem of training qualified personnel is also gradually being solved. A great contribution to its solution was made by the institutes for the protection of motherhood and infancy created in 1922 in Moscow, Kharkov, Kyiv and Petrograd.

1930s

The Great Depression came to the USA during these years. Already, about 75% of births took place in hospitals. Finally, doctors who specialized in obstetrics began to help women in labor. Unfortunately, infant mortality has increased from 40% to 50% - mainly due to birth injuries that children received due to unwanted medical intervention. The "twilight sleep" method was now used so frequently that almost no woman in labor in the United States could remember the circumstances of the birth.

The "twilight sleep" method was now used so frequently that almost no woman in labor in the United States could remember the circumstances of the birth.

The USSR is also rolling back: the turning point was 1936, when the resolution "On the prohibition of abortions, the increase in material assistance to women in childbirth, the establishment of state assistance to large families, the expansion of the network of maternity hospitals, nurseries and orphanages, the strengthening of punishment for non-payment of alimony and some changes in the legislation on abortion" was adopted.

Since the late 1930s, the mortality rate has been significantly affected by the introduction of new medical technologies and drugs, in particular sulfonamides and antibiotics, which can dramatically reduce infant mortality even during the war years.

Now abortions were performed only for medical reasons. Accordingly, clandestine abortions, dangerous to a woman's life, became part of the shadow economy of the USSR. Abortions were often done by people who had no medical education at all, and women, having received complications, were afraid to go to the doctor, because he was forced to report the offender "to the right place." If an unwanted child did appear, sometimes he was simply killed.

Abortions were often done by people who had no medical education at all, and women, having received complications, were afraid to go to the doctor, because he was forced to report the offender "to the right place." If an unwanted child did appear, sometimes he was simply killed.

1940s

In the years following the end of wars, there is a sharp increase in overall marriage and birth rates. In the US, the birth rate is 1945 was 20.4%. In the United States, the first books in defense of natural childbirth appear, and the popularity of minimal intervention in the process of childbirth is slowly growing. In the same years (in 1948), Kinsey's research on sexuality saw the light, which gave women a better understanding of their own reproductive system.

1950s

On November 23, 1955, by the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR “On the abolition of the prohibition of abortion”, the operation of artificial termination of pregnancy was allowed for all women, even in the absence of medical contraindications.

The decree allowed abortions in hospitals, while home abortion remained a criminal offense. The doctor in this case was threatened with imprisonment of up to one year, and in the event of the death of the patient, up to eight years.

Separately, about the ultrasound procedure. Until a certain period, Soviet medicine did not have such opportunities, and the sex of the child, like many pathologies, was determined “by eye”: by manual examination and listening to the abdomen with a special tube. The first department of ultrasound was created on the basis of the Acoustic Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences under the leadership of Professor L. Rozenberg in 1954, and only from the end of the 80s, ultrasound began to gradually take root in Soviet medicine.

1960s

First fetal heart rate monitoring available in the US. Postpartum care increasingly included antibiotics, and maternal and child mortality rates plummeted.

After giving birth, a woman in the US finally has the opportunity to buy a birth control pill.

1970s

American women in these years had significantly more ways to relieve labor pains than women in the USSR. Twilight sleep is being replaced by less harmful methods of pain relief, such as hypnosis, childbirth in water, special breathing, and the famous Lamaze method, a technique for preparing for childbirth, developed in 1950s by the French obstetrician Fernand Lamaze as an alternative to medical intervention during childbirth. The main goal of the "Lamaze method" is to increase the mother's confidence in her ability to give birth, help in eliminating painful and painful sensations, facilitate the birth process and create a psychologically comfortable mood.

MR Auden owns the first publication in a scientific journal on the topic of aquatic birth [Lancet, 1983, ii, 1476-1477]. M.R. Auden described water births as "more natural" and "closer to nature" and based his conclusions on the successful practice of childbirth in the pool of the Pitiviere clinic since the early 70s.

M.R. Auden described water births as "more natural" and "closer to nature" and based his conclusions on the successful practice of childbirth in the pool of the Pitiviere clinic since the early 70s.

Epidural anesthesia is being used for the first time, which, unfortunately, slowed down contractions in almost half of the cases.

And in the same years, pitocin was invented - a means to stimulate childbirth.

1980s

In the early 1980s, “circles” were gaining popularity in the USSR, promoting the fashion for the same natural childbirth: in water or at home. One of the ideological inspirers of this method was the physiologist Igor Charkovsky, who created the Healthy Family club. The Soviet government fought against such tendencies.

Since the end of the 80s, the ultrasound procedure began to be gradually introduced into Soviet medicine, although the quality of the images left much to be desired.

In the early 1980s, the term for artificial termination of pregnancy in the USSR was increased from 12 to 24 weeks. In 1987, it was possible to terminate a pregnancy even for up to 28 weeks, if there were indications for this: disability of the first and second groups in the husband, death of the husband during the wife's pregnancy, divorce, the stay of the woman or her husband in prison, the presence of a court decision on deprivation of parental rights, large families, pregnancy as a result of rape.

In 1989, outpatient abortion was allowed at its early stages by vacuum aspiration, that is, mini-abortion. Started medical abortion.

1990s

The 1990s is a time when doctors are looking for a balance between natural childbirth and medical childbirth. The idea is growing stronger that the better the mother feels, the better the baby will be.

In the mid-1990s, about 21% of children were born by caesarean section, and this number is steadily increasing.

The Times reporter writes: "The rise in caesarean sections in the mid-1990s was due to an increase in the number of pregnant women who were scheduled for this procedure before the 39th week of pregnancy, even if it was not medically justified."

Another popular trend of the 90s is home birth. Although the number of such practices in the United States in those days was only less than 1% of all births, this number also began to grow.

Amniocentesis appears - an analysis of amniotic fluid, during which a puncture is made in the embryonic membrane and a sample of the amniotic fluid is taken. It contains fetal cells that are suitable for testing for the presence or absence of genetic diseases.

There is a practice of doulas - assistants during childbirth, who provide practical, informational and psychological assistance to a woman in labor.

2000s

Approximately 30% of births are by caesarean section.