How many child soldiers are there in south sudan

South Sudan CSPA Country Profile • Stimson Center

Specifically, the president has waived more than $20 million in Direct Commercial Sales, $773,000 in International Military Education and Training, and more than $229 million in Peacekeeping Operations assistance from FY2013 through FY2022. After not receiving a waiver in 2022, South Sudan was denied $18 million in FY2023 Peacekeeping Operations assistance due to CSPA prohibitions.

Since 2021, U.S. presidents have been required to include justifications for CSPA waivers that were issued during the previous year in the annual Trafficking in Persons Report. South Sudan’s 2020 and 2021 waiver justifications maintain that “waiving restrictions to PKO assistance is in the U.S. national interest,” as PKO funds are used to support essential ceasefire monitoring mechanisms or efforts in the country – including the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, which requires the government of South Sudan to refrain from the recruitment and use of child soldiers.

According to the U.S. State Department, government and opposition forces in South Sudan are believed to have recruited more than 19,000 children for use as soldiers since the country’s civil war began in 2013. Experts estimate that there were between 7,000 and 19,000 child soldiers in South Sudan as of February 2021. Government forces – including the South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF) and the South Sudan National Police Service (SSNPS) – as well as allied militias that have received government support – including the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North (SPLM/A-N) – have all recruited and used child soldiers. The SSPDF, SSNPS, and allied militias continued to recruit and use child soldiers as of March 2022. South Sudanese government forces use children to fight and perpetuate violence against other children and civilians, serve as bodyguards, staff checkpoints, and in other security support roles.

In a 2018 peace agreement, the South Sudanese government and other warring parties committed to “refrain from” the “recruitment and/or use of child soldiers by armed forces or militias in contravention of international conventions. ” The government also signed a UN Action Plan in February 2020 to end and prevent all grave violations against children. Between April 2021 and March 2022, the government cooperated with an international organization to demobilize and release 20 child soldiers, compared to the 189 child soldiers demobilized and released the previous year. However, as of March 2022, South Sudanese security forces had yet to fully implement the 2020 action plan to demobilize child soldiers currently within their ranks, and many SSPDF officers did not meet their annual training requirements to increase their awareness of international standards and obligations around the recruitment and use of child soldiers. In addition, the government has yet to hold members of the SSPDF, SSNPS, or allied militias criminally or administratively accountable for the recruitment and use of child soldiers.

” The government also signed a UN Action Plan in February 2020 to end and prevent all grave violations against children. Between April 2021 and March 2022, the government cooperated with an international organization to demobilize and release 20 child soldiers, compared to the 189 child soldiers demobilized and released the previous year. However, as of March 2022, South Sudanese security forces had yet to fully implement the 2020 action plan to demobilize child soldiers currently within their ranks, and many SSPDF officers did not meet their annual training requirements to increase their awareness of international standards and obligations around the recruitment and use of child soldiers. In addition, the government has yet to hold members of the SSPDF, SSNPS, or allied militias criminally or administratively accountable for the recruitment and use of child soldiers.

For more information, see the U.S. State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report and Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. More information on the situation in South Sudan can also be found in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report on Children and Armed Conflict and country-specific report on South Sudan.

More information on the situation in South Sudan can also be found in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report on Children and Armed Conflict and country-specific report on South Sudan.

Total Waived and Prohibited

Since the CSPA took effect.

Child soldiers of South Sudan | Humanitarian Crises

Former child soldiers during the release ceremony, outside Yambio in South Sudan. One hundred twenty-eight children (90 boys and 38 girls) were officially released at this ceremony by two armed groups, bringing the total number released this year to over 900. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]By Andreea Campeanu and Patricia Huon

Published On 30 Oct 201830 Oct 2018

Yambio, South Sudan – On the red, dusty ground in Yambio, under a large mango tree, a group of 30 girls and boys, some wearing military clothes and some with guns next to them, sit in the shade eating biscuits while waiting for the start of the ceremony to release them from the army.

The US ambassador and other guests are coming from the capital Juba to attend the event.

They are part of the 900 children released from the armed forces in South Sudan in 2018, the country with one of the largest number of child soldiers in the world. The ceremony consists of them symbolically taking off the military clothes, and receiving blue UNICEF labelled notebooks and schoolbags.

According to the UN, there are still 19,000 children in armed forces in South Sudan, a number contested by the army. “We have concerns about the figures published by UNICEF. We don’t know how they came up with those numbers. Now, it’s true that some other groups that were integrated into the SPLA had child soldiers among them. But our policy is clear: we don’t want child soldiers,” said Lul Ruai Koang, the spokesperson for the South Sudan’s People Defence Force (former SPLA). “We gave their names to UNICEF. In Pibor or Yambio, they have been demobilised. We facilitate the process. After, it’s their responsibility to help them. ”

”

Many of the children in the ceremony have already returned to their communities before the official release. They received medical screenings, counselling and psychosocial support as part of their rehabilitation, and some were assisted to return to school, while others received vocational training. Their families were also provided with food assistance.

But across South Sudan and in refugee camps outside the country, there are children and youth who left or escaped from the armed forces but received no assistance and have not been through a rehabilitation programme. Depending on age, boys are either used as porters, cleaners, or are trained to fight. Girls are often taken as “wives”, and often return in their communities with children.

“We see depression, anxiety. They have intrusive thoughts that come back. That can be triggered by something happening, but of which they have no control. That can affect their functionality,” says Rayan Fattouch, mental health specialist working in Yambio with Doctors Without Borders (known by its French initials, MSF).

MSF is medically screening the children who were associated with armed groups. Part of it is the mental health aspect. They are dealing with children and young adults who are facing “moderate to severe trauma”.

“The child needs to feel embraced by his community. And that can change from one community to another, depending on the experiences they have been through. They have their own trauma,” said Fattouch.

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

According to the UN, there are still around 19,000 children serving in armed forces across South Sudan. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]Advertisement

An 18-year-old boy from Yei. He said he was abducted and held by a militia aligned to the SPLA since the conflict started in 2013. 'They would raid villages', he said. 'We were given weed to smoke and alcohol [to drink], so that we don’t think about what they made us do.' He said he was treated rather fairly by the commanders and was given food to eat, but life in the bush was not easy. He managed to escape when the militia he was held by moved to Equatoria with SPLA troops. He took advantage of being near the border to escape to Uganda. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]A 15-year-old girl who was held by armed forces for a week. Originally from Mayendit, she was collecting firewood outside the Protection of Civilians (POC) site near Bentiu, in December 2017. 'Soldiers came to us, they had guns and uniforms. We all tried to run away, but they caught me.' They took her to Bentiu town, and kept her for a week. She was repeatedly raped. 'One soldier took me as a wife. But when he was away, the other soldiers would come to the house and do what they wanted with me. That man didn't care. He was mean to me; he would beat me and say I was useless. I was thinking to kill myself.' She now lives in the POC near Bentiu with her family, who are supportive but very poor. She's going to school and hopes to be able to complete her studies and forget about the past. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]Augustino Ting Mayai was part of the Red Army in the second civil war that started in 1983 and lasted till 2005.

He managed to escape when the militia he was held by moved to Equatoria with SPLA troops. He took advantage of being near the border to escape to Uganda. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]A 15-year-old girl who was held by armed forces for a week. Originally from Mayendit, she was collecting firewood outside the Protection of Civilians (POC) site near Bentiu, in December 2017. 'Soldiers came to us, they had guns and uniforms. We all tried to run away, but they caught me.' They took her to Bentiu town, and kept her for a week. She was repeatedly raped. 'One soldier took me as a wife. But when he was away, the other soldiers would come to the house and do what they wanted with me. That man didn't care. He was mean to me; he would beat me and say I was useless. I was thinking to kill myself.' She now lives in the POC near Bentiu with her family, who are supportive but very poor. She's going to school and hopes to be able to complete her studies and forget about the past. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]Augustino Ting Mayai was part of the Red Army in the second civil war that started in 1983 and lasted till 2005. In the early 1980s, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) recruited and trained boys as young as 12. The child soldiers were called the Red Army. In 2013, the Red Army Foundation (RAF) was formed, an organisation dedicated to addressing social problems, especially among its own former members and South Sudan's youth. Mayai, a member of the Red Army Foundation, now holds a PhD in sociology and is a director of research at the Sudd Institute and an assistant professor at the University of Juba’s School of Public Service. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]Children walk outside the POC in Juba, South Sudan, home to more than 40,000 people. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]A 16-year-old boy who was a bodyguard in the opposition group South Sudan National Liberation Movement (SSNLM) plays football outside the transit centre ran by World Vision and UNI. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]

In the early 1980s, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) recruited and trained boys as young as 12. The child soldiers were called the Red Army. In 2013, the Red Army Foundation (RAF) was formed, an organisation dedicated to addressing social problems, especially among its own former members and South Sudan's youth. Mayai, a member of the Red Army Foundation, now holds a PhD in sociology and is a director of research at the Sudd Institute and an assistant professor at the University of Juba’s School of Public Service. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]Children walk outside the POC in Juba, South Sudan, home to more than 40,000 people. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]A 16-year-old boy who was a bodyguard in the opposition group South Sudan National Liberation Movement (SSNLM) plays football outside the transit centre ran by World Vision and UNI. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]Advertisement

A boy who was in an armed group learning carpentry at a vocational training centre ran by UNICEF outside the city of Yambio. [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]Originally from Bentiu, this young man fled in December 2013 when the conflict broke out in his town. He went to a smaller town called Mayom, where the war had not yet reached. There, he wanted to keep on going to school. But in April 2014, when he was 14, government soldiers came to the town and took him away. 'I was forced to be a soldier. Many people were taken that day. I knew that they were there looking for new recruits'. He was taken for training with other young men, to a military camp. 'They would beat up those who resisted.' After he managed to escape, he made his way to Juba, where he now lives. He last heard from his parents and brothers three years ago. 'War creates a lot of destruction, war kills people, he says. You are going backwards. But I hope that with studying, I can make progress.' [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]The one-month-old baby girl of a mother, 16, who was held by rebel soldiers, is sleeping on a mat in their compound, outside Yambio.

[Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]Originally from Bentiu, this young man fled in December 2013 when the conflict broke out in his town. He went to a smaller town called Mayom, where the war had not yet reached. There, he wanted to keep on going to school. But in April 2014, when he was 14, government soldiers came to the town and took him away. 'I was forced to be a soldier. Many people were taken that day. I knew that they were there looking for new recruits'. He was taken for training with other young men, to a military camp. 'They would beat up those who resisted.' After he managed to escape, he made his way to Juba, where he now lives. He last heard from his parents and brothers three years ago. 'War creates a lot of destruction, war kills people, he says. You are going backwards. But I hope that with studying, I can make progress.' [Andreea Campeanu/Al Jazeera]The one-month-old baby girl of a mother, 16, who was held by rebel soldiers, is sleeping on a mat in their compound, outside Yambio.90,000 How almost 300 child soldiers were demobilized in South Sudan |

Some 3,000 young South Sudan Democratic Army fighters will soon be heading home. They will be demobilized as part of an agreement reached between the UN and the former rebel group. Rehabilitation of former child soldiers will be taken up by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). About how the demobilization process is going on - a report by Artem Pashchenko.

*****

In March 2014, the UN launched a campaign called "Children not soldiers". The goal of the campaign is to end the recruitment and use of children as soldiers by 2016.

The project is being implemented by UNICEF, as well as by several UN entities. These are the office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children in Armed Conflict, Leila Zerrougui, and the Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration Units, which are part of the UN Department of Peace Operations. Assistant Secretary General Dmitry Titov speaking:

“ UN Department of Peacekeeping deals with issues such as the demobilization and disarmament of combatants and their reintegration into normal civilian life, the collection of weapons and their destruction ".

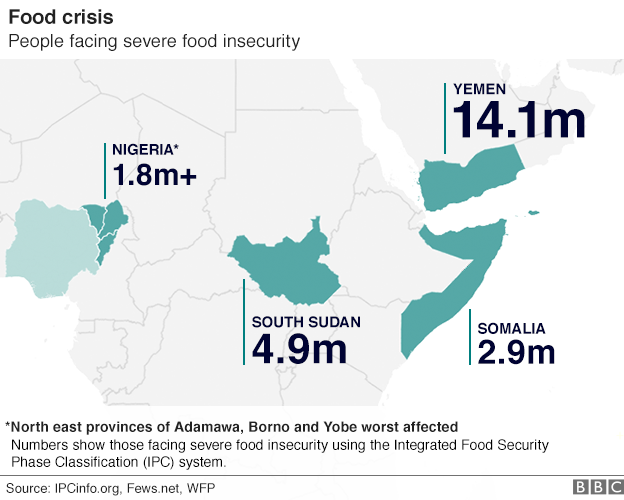

Countries whose government forces recruit children include Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Yemen, Myanmar, Somalia, Sudan, Chad, and South Sudan. With the exception of Yemen and Sudan, the remaining six countries have already signed action plans with the UN to end the practice.

In late 2013, clashes erupted in South Sudan between supporters of the president and the prime minister. The conflict turned into a full-scale armed confrontation. The army and the opposition began recruiting children. The UN estimates that 12,000 children were recruited into various rebel groups in South Sudan in 2014.

The UN worked hard with the South Sudanese authorities and the opposition to bring children back from the front. And so, at the end of January, 280 former Cobra fighters from the South Sudan Democratic Army surrendered their weapons and uniforms. The fact is that quite recently, Cobra and the government of South Sudan signed a ceasefire agreement.

True, former Cobra commander David Yau-Yau denies that teenagers were recruited by force:

« We did not force them to become soldiers. This is their own choice. They deliberately enlisted in the army ".

The UN does not divide child soldiers into those who voluntarily took up arms and those who were forced to do so. They believe that minors have no place in the war.

Among the Cobra fighters are teenagers aged 11-17. Many of them served for about four years and never went to school. As a rule, in zones of armed conflict, both the army and the rebels recruit children and teenagers not only as soldiers, but also as cooks and porters. Sometimes boys are turned into sex slaves.

Now the demobilized children will go to a special center where they will be provided with the necessary medical care, food, water and clothing. Then they will be taken to their homes. Psychologists will work with some teenagers.

UNICEF staff will soon meet with the children, who will teach them literacy and other skills needed in everyday life. Jonathan Veitch from UNICEF says:

« All kids want to learn. Many of them never went to school. They need study support. Before that, we want to provide psychological assistance to those who need it. After all, these children have seen terrible things. Then we will assign them to courses where they can learn certain professions, for example, carpentry. We hope that all of them will find work and become useful members of their society ".

Some of the former child soldiers already know what they will do in civilian life. Says a 12-year-old former fighter who did not give his name:

“ I don't want to fight anymore. Soldiers never have anything. I think that if I had stayed in the army, someday I would have been killed. Now I want to go to school. And then I will study to be a doctor .”

It seems that the military has come to understand that the future of the country depends on children. Former commander David Yau-Yau says:

« Children need to be supervised, especially their mental development. In the army, they will not become good people. The best way for them is to study. They must be treated with respect. After all, it depends on teenagers what tomorrow will be like in this country of .”

And very soon more than 2.5 thousand former juvenile Cobra fighters will go home.

When child soldiers grow up... Motherland on the Neva

Sudan and South Sudan on the map of AfricaNumerous military conflicts already blazing or smoldering along the periphery of the borders of modern Russia give rise to a whole series of serious and, sometimes, the most unexpected problems , which will have to be decided in any case. And a huge part of them overtakes after the war ends. This happens not only with us. This happens in every part of the world where wars start and end. And in order to understand what we may have to face in the future, it makes sense to look at the experience of other territories, even if they are very far from us.

Overcoming the consequences of war is always a multifaceted process. War leaves behind very different traces. These are minefields, which take years to clear. And the destroyed infrastructure, without the restoration of which a peaceful life is very problematic.

And they are also people: a huge part of the population who took part in the hostilities and needs medical support and a new, post-war socialization. The larger and fiercer the war was, the larger this part of the population.

In South Sudan, which gained independence eight years ago, this social problem is presented in its most extreme form: the civil war that broke out a few years later turned children into soldiers. This has happened very often in world history. It was the same in Russia during the Great Patriotic War, when teenagers (and it happened that they were just children) went to partisan detachments or even to army units. But very rarely this phenomenon acquired such a scope as in African countries. How are the consequences of this overcome in the conditions of modern African reality? How are the children who fought in South Sudan socialized?

War cubs

Seventeen-year-old namesake of the 44th President of America Moses Obama lived in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, when the three-year-old civil war resumed in 2016. He fled to his family home in the countryside, where he discovered that his father had been killed and his mother was missing. Soon an anti-government group called "In Opposition" (IO) took control of his village. Lonely, heartbroken and hungry, he waited for his mother's return. But the opportunity to have a new family, not to mention hot food and shelter, was too hard to pass up. Having lost everything, he joined the huge children's army of the Sudanese bush.

Over the next two years, Moses rose through the ranks. He did well what he was taught. “I had to kill so many innocent people from my country that I just stopped counting them,” he says.

Armed formations in all African countries take people like Moses into their ranks on purpose: children do not yet fully understand what exactly they are doing. And so it's easiest to make a child a killer who won't hesitate.

Marked with blood

A brutal civil war ravaged South Sudan for nearly six years. It claimed over 400,000 lives. UNICEF estimates that more than 19,000 children have been drawn into the ranks of the warring factions during this time. Adaptability, malleability, and an underdeveloped ability to assess risk make these children the best recruits. Immersed in an environment of extreme violence, child soldiers commit unimaginable atrocities. Then they become social outcasts with severe psychological problems.

“These are children who were forced, either by circumstances or by force, to participate in armed groups, many of which did, at times, terrible things. Who committed war crimes. It is our collective responsibility to help them return to a peaceful life,” says Sharon Riggle , who works for the UN Secretary General's Special Representative for Children in Armed Conflict.

What Africa is now facing is nothing new. Although on the black continent this is now presented in the most concentrated form. But now the world is entering a period of instability, and who knows in which of its regions such a situation could happen again at any moment.

According to her, the number of children involved in the South Sudanese civil war is an underestimate and in fact they are much higher than commonly thought. She says that, despite the best efforts of UNICEF and other international humanitarian organizations that provide assistance and ensure the safety of recently released children (as far as their very limited budgets allow), tens of thousands of children are currently in need of access to rehabilitation programs, but not can get it. Simply due to lack of sufficient funding. Yet proper psychological care, health care and education are essential for the reintegration into society of war-affected children.

The right to a future

Education suffered the most during this armed conflict. It was not only the child soldiers who lost it, but also many ordinary children throughout South Sudan. For vast numbers, commuting to school on booby-trapped roads, under fire from snipers, and under the constant threat of kidnapping has become commonplace. Institutions of public education were purposefully attacked, schools were burned down, teachers were killed.

The parents of thirteen-year-old Kennedy did not want to send him to school just for fear of an armed attack, kidnapping and forcible recruitment into the ranks of paramilitary groups. But he still witnessed violence, torture and death. Having been evacuated to Uganda, he still did not attend school, unable to fulfill his dream of becoming a doctor, as his family could not even afford the shoes needed to enter school.

Helping Africa cope is not just a humanitarian issue. It's also a matter of experience. Which, with a certain development of events, can be invaluable.

Today, twelve months later, Kennedy is back at school in the Bidibidi refugee settlement thanks to an education program run by the PEIC Foundation and the humanitarian organization Artolution. The International Citizens' Education Program (GCED), operating under the auspices of UNESCO, brings together artists, educators, children and youth from both refugees and their host communities. Within its framework, Kennedy and other South Sudanese children who have lost a normal childhood are given back the right to a future.

The Last King of Scotland

Another foundation helping a war-torn society transform into a peaceful, resilient and stable society is Hollywood actor Forest Whitaker's WPDI. It was created after Forest Whitaker won an Oscar in 2009 for his role as African dictator Idi Amin in The Last King of Scotland. This movie was filmed in Uganda. Exactly where many children in South Sudan have been displaced.

The current situation requires that the world community finally recognize the need to create a full-scale international program of specialized, individual and long-term care aimed at the rehabilitation of children - participants in the war.

According to Forest Whitaker, being involved in the establishment of peace on the planet is amazing. He believes it is a privilege to be able to help eliminate pain, conflict, and violence. In South Sudan and Uganda, his foundation, along with PEIC, supports the Youth Peacemaker Network (YPN) program to empower and mobilize young people to become effective leaders and advocates for their communities.

One of the alumni of this program, David Kaji, was abducted at the age of nine by the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda. He was too small and weak to carry a weapon. Instead, he was forced to cut people with a knife and burn them alive in their houses. David, now 22, who completed a youth peacebuilding course at the WPDI Community Training Center in Gulu, Ugandan, says that although he still hears the screams of his victims at night, the program saved his life, giving him the opportunity to start his own business and enter university.

Adult children

Today, more than 8,000 children are waiting for help in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and thousands more in the Central African Republic and other countries in the region. After the ceasefire in South Sudan, it turned out that children captured by armed groups could only be released in small batches, since there was simply no infrastructure or mechanisms for releasing all the children at the same time.

According to the representative of the British organization "Children of War" Rocco Bloom , these kids don't get the attention they deserve. The current situation requires that the world community finally recognize the need to create a full-scale international program of specialized, individual and long-term care aimed at the rehabilitation of these children, since their number indicates that a new social problem of enormous proportions has formed in the region.

In order to understand what we may have to face in the future, it makes sense to look at the experience of other territories, even if they are very far from us.

So far, only individuals and organizations have made significant efforts to ensure that children emerging from armed conflict receive everything they need to reintegrate into society and have a future in adult life. If this problem is ignored, then in less than a decade the international community will have a huge mass of non-socialized population with a deeply traumatized psyche, having only military skills. What consequences this may have is not difficult to guess.

Once upon a time, a hundred years ago, the Soviet writer Arkady Gaidar , who himself went through something very similar during the Civil War, wrote: “I dreamed of people I killed in my childhood” (c). Yes, what Africa is facing right now is nothing new. Although on the black continent this is now presented in the most concentrated form.