How is day of the dead celebrated when a child dies

Remembering Children on the Day of the Dead ⋆ Photos of Mexico by Dane Strom

Skip to content

Instagram Facebook Youtube

Last Updated Nov 2, 2019 Mexican Holidays

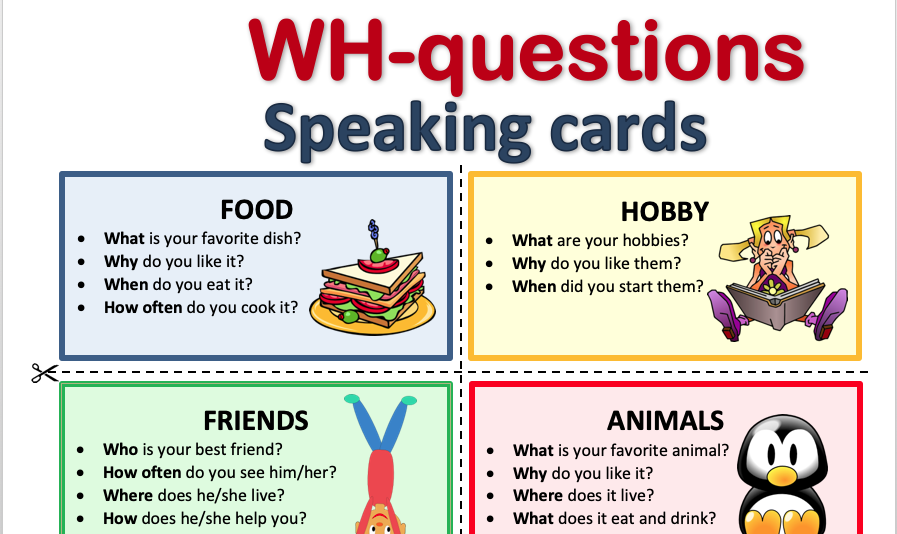

The Day of the Dead is a misnomer. It doesn’t last just a day, but three. November 2 is the main celebration, but the day before is known as Children’s Day or Day of the Little Angels (Día de los Angelitos).

Some parents who have lost children will spend this afternoon creating an altar in the graveyard or at their home (either inside or outside for everyone to see on the street). Items are left, such as favorite foods and drinks, games, toys, balloons, footballs, as well as the traditional Day of the Dead offerings. It’s a touching way to remember the children who have died.

Día de los Angelitos happens the day before the big events of November 2 because it’s said the spirits of the children are so eager to come back to the land of the living, that they run ahead of the adults, who arrive a night later.

The day is also sometimes called el Día de los Inocentes (Day of the Innocents), but this can be confused without further clarification for Mexico’s version of April Fool’s Day on December 28.

An altar for a boy, including mini-representations of some of his favorite things. Families who have lost children might light the altar on the night of October 31 and/or November 1 for the angelitos (little angels), who rush back home quicker than their adult counterparts, who arrive later on November 2.Inside a mausoleum for a family, which was decorated on the Día de los Angelitos for a young girl.Handmade decorations and candles light up an altar with toy blocks that spell “B-A-B-Y” on a tomb in the graveyard in Ajijic, Jalisco.A colorful grave with balloons remembering a child during the Day of the Dead in Jalisco, Mexico.A display created on the Día de los Angelitos for a seven-year-old boy named Denny, created in the graveyard in Ajijic, Jalisco.A November 1st Children’s Day display during the Days of the Dead in Ajijic, Jalisco. A candlelit ofrenda on the Noche de los Angelitos in the graveyard in Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico.A grave with toys on November 1 in Ajijic, Mexico.Decorations on a grave decorated for el Día de los Angelitos in Ajijic, Mexico.An altar for family, friends and a young grandson on el Día de los Angelitos in Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico.Toys left on a headstone on November 1 during the Days of the Dead in Jalisco, Mexico.Mari Huizar paints her family’s plot in the cemetery on the Day of the Innocents 2018. Her young disabled daughter died in the previous year. She asked me to come back later that night to take photos of it lit with candles, but I couldn’t make it back. I’ll go again in 2019 to take the photo and see how she has decorated the grave this year.Mari’s family helps clean and decorate the grave.The grave for Mari’s daughter, Rosario Guadalupe Rodríguez Huizar, March 8, 2009 – February 2, 2018. Photo taken in 2019.

A candlelit ofrenda on the Noche de los Angelitos in the graveyard in Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico.A grave with toys on November 1 in Ajijic, Mexico.Decorations on a grave decorated for el Día de los Angelitos in Ajijic, Mexico.An altar for family, friends and a young grandson on el Día de los Angelitos in Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico.Toys left on a headstone on November 1 during the Days of the Dead in Jalisco, Mexico.Mari Huizar paints her family’s plot in the cemetery on the Day of the Innocents 2018. Her young disabled daughter died in the previous year. She asked me to come back later that night to take photos of it lit with candles, but I couldn’t make it back. I’ll go again in 2019 to take the photo and see how she has decorated the grave this year.Mari’s family helps clean and decorate the grave.The grave for Mari’s daughter, Rosario Guadalupe Rodríguez Huizar, March 8, 2009 – February 2, 2018. Photo taken in 2019.See More of Mexico

- Photo Series

- Photo Essays

- Photo Gallery

- Videos

Fine Art Photography Prints of Mexico

Carnaval 2022

Two children are dressed as catrines on the Day of

Victor Rochin launches a rocket during the process

Hice una página web / guía turística virtual pa Un joven charro en el Día del Charro en Ajijic, JUn "castillo" de fuegos artificiales durante las f

All images © Dane Strom

Día de los Muertos: 5 Day of the Dead Traditions Explained

By Helen Partlow, publisher of Macaroni KID Mt. Sinai and Port Jefferson, N.Y. and Natalie Sanchez, publisher of Upland/Claremont/La Verne October 28, 2022

Sinai and Port Jefferson, N.Y. and Natalie Sanchez, publisher of Upland/Claremont/La Verne October 28, 2022

Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is a holiday celebrated in Mexico and by those of Mexican heritage throughout the world.

While this holiday is typically held around the same time as Halloween, it is its own separate holiday with its own traditions and intentions. While Halloween is a spooky type of holiday, Día de los Muertos is a celebration of life. Many of us know about Day of the Dead from the animated movie "Coco," the 2017 film about a 12-year-old boy named Miguel who is accidentally transported to the Land of the Dead.

rimmabondarenko via Canva |

1. Día de los Muertos is always celebrated Nov. 1 & 2

Día de los Muertos originates back to pre-Hispanic times with the indigenous peoples the Aztec, Maya, Toltec, and other Nahua people. These pre-Hispanic cultures considered mourning the dead to be disrespectful. They saw the dead as still being members of the family, who came alive through memory and spirit.

These pre-Hispanic cultures considered mourning the dead to be disrespectful. They saw the dead as still being members of the family, who came alive through memory and spirit.

Once the Spanish arrived in Mexico, this holiday got intertwined with All Saints' Day (celebrated Nov. 1) and All Souls' Day (celebrated Nov. 2). Today Día de los Muertos is typically celebrated on Nov. 1 and 2. Nov. 1 is a day to remember children who have passed, and Nov. 2 is set aside to remember adults who have passed.

egumeny via Canva |

2. Día de los Muertos celebrates life

Día de los Muertos is often misunderstood because it happens around the same time as Halloween and uses symbols such as skulls. But Día de los Muertos is a celebration of life — of the memories and bonds that tie us together that most certainly survive one’s death into the beyond. It is believed that for a brief 24 hours during Dia de los Muertos, loved ones who have died can be reunited with the living for a big celebration of life.

This celebration is an energetic, colorful event designed to demonstrate love and respect for family members who have died. It's believed those who have died get to join in on the Día de los Muertos celebrations. Costumes, parades, and dancing are often a large part of the celebration.

mariacastellanosphotos via Canva |

3. Creating an ofrenda to welcome the dead back

People make an ofrenda, or altar, at cemeteries and their private homes as an homage to the dead. The ofrenda is different from altars meant for praying. Instead, the ofrenda is meant to welcome the dead back to the land of the living. These altars may include the deceased loved one's photos, as well as their favorite incense, candles, foods, and other items from when they were alive. These items together are meant to help attract the souls to visit the living in celebration. Ofrendas are often decorated with marigolds or the flor de muerto, which translates to "flower of the dead." Marigolds are often scattered from the ofrenda to the gravesite as a way to guide the dead back to their place of rest.

Ofrendas are often decorated with marigolds or the flor de muerto, which translates to "flower of the dead." Marigolds are often scattered from the ofrenda to the gravesite as a way to guide the dead back to their place of rest.

MStudioImages via Canva |

4. Emergence of Calavera Catrina

In the 19th century, artist José Guadalupe Posada re-imagined what he believed Mictecacíhuatl, the Aztec goddess of the underworld, looked like as a female skeleton. His rendering is now known as the Calavera Catrina.

“Todos somos calaveras,” meaning “we are all skeletons” is a quote often attributed to Posada. It means "we are all the same on the inside."

Today, people wear masks and face makeup in a colorful fashion to mimic the Calavera Catrina.

pashapixel via Canva |

Sugar Skulls and other traditional foods

Sugar Skulls and other traditional foodsThose returning from the land of the dead are believed to work up quite an appetite along their journey, so families often leave out the dead’s favorite foods as well as some other more common traditional dishes.

Pan de muerto — bread of the dead — is a sweet bread with a little bit of anise. There are many different variations across Mexico, including one in Oaxaca City where they add a face, or caritas, in the center.

Sugar candy is molded into the shape of skulls in celebration of Día de los Muertos. These started in the 17th century with Italian missionaries. This sugar art is often colorful and can vary in size as well as complexity.

Local Dia De Los Muertos Events & Celebrations

Saturday, October 29

Rio de Ojas, 250 Harvard Ave, Claremont

From 9am - 3pm Rio de Ojas will have artists and their wares for sale. From 5pm - 8pm Shelton Park will have altars and music.

Now - November 2

Creme Bakery, 116 Harvard Ave N., Claremont

Pan de Muerto is an essential part of a Día de los Muertos home altar or shrine, also called an ofrenda. The bread adorns the altar openly or in a basket and is meant to nourish the dead when they return to the land of the living during Día de Los Muertos. Creme Bakery Pan de Muerto is available with sugar or sesame until November 2.

Sunday, October 30

Muckenthaler Cultural Center, 1201 W Malvern Ave, Fullerton

Día de los Muertos: making death a little bit less scary for everyone every year. Our Day of the Dead celebration is family-friendly (kids encouraged!). Expect colorful, festive decorations, traditional music and dance performances, and arts and crafts! This festival runs from 12pm - 4 pm.

Sunday, October 30

Forest Lawn Covina Hills

Attend one of Forest Lawns Dia de los Muertos events in person and on Facebook Live. The event runs from 2pm-4pm and includes Alter, Cultural Expressions, Folklorico Dance Group and Mariachi Music

The event runs from 2pm-4pm and includes Alter, Cultural Expressions, Folklorico Dance Group and Mariachi Music

Tuesday, November 1

Don Day Neighborhood Center, 14501 Live Oak Ave, Fontana

Shake your bones and join the City of Fontana in celebrating life and death. Explore the historical and cultural significance of the Day of the Dead Traditions. Festivities will take place on Tuesday, November 1, from 4 pm-7 pm. Free admission! For more information, visit Halloween.Fontana.org

November 1 - 6

Kidspace Children's Museum, 480 N Arroyo Blvd, Pasadena

Celebration of life at the six-day Día de Los Muertos (Day of The Dead) festivities at Kidspace, November 1-6. The program includes music, art, and a community ofrenda where families can share memories of people and pets who have enriched their lives.

Wednesday, November 2

Lewis Family Branch, 3850 East Riverside Drive, Ontario

Join us as we celebrate Dia De Los Muertos at Lewis Family Branch! Paint a flowerpot and make paper marigolds to fill them. These beautifully decorated pieces will be the perfect addition to add to your ofrenda. For more information, please call (909) 395-2256

These beautifully decorated pieces will be the perfect addition to add to your ofrenda. For more information, please call (909) 395-2256

Now-November 27

Día de Los Muertos: Cempasúchil: Instruments of the Wind

Ontario Museum, 225 South Euclid Avenue, Ontario

Stop by the Ontario Museum of History & Art and view our Día de Los Muertos exhibit, Cempasúchil: Instruments of the Wind. The exhibit features a plethora of different artistic mediums, including paintings, drawings, photos, ceramics, altars, and sculptures! Come explore the indigenous origins of the holiday, like the history of the ofrenda and the significance of the marigold!

- 10 Books about the Day of the Dead for kids

- 5 Family Movies to Celebrate the Day of the Dead

- 25 Day of the Dead Crafts for kids

Helen Partlow is the publisher of Macaroni KIDMt. Sinai and Macaroni KID Port Jefferson, N. Y.

Y.

How Mexico celebrates the Day of the Dead — Snob

On November 2, Mexico celebrates one of the most unusual holidays in the world — Dia de Muertos

Photo: Ivan Diaz / UnsplashThe cemetery could be seen from afar, a couple of kilometers away. From the Mexican town of San Luis Rio Colorado, located on the border with American Arizona, we left already dark, and all the way outside the windows only the harsh Sonoran Desert blackened in complete silence. The lonely necropolis outside the city limits today, on the Day of the Dead, looked like a real island of life, illuminated by searchlights and surrounded by cars; music that was not at all mournful could be heard from behind the fence, the cries of children, laughter, the barking of dogs, and even, it seems, the tinkle of beer bottles. (Actually, why be surprised if we also had a case of beer in our trunk?)

On November 2, I was visiting Mexican friends in a place that was not at all touristy. In the north of Mexico, which is considered more Americanized than the south and center, on the occasion of the Day of the Dead, city carnivals are not arranged. But the traditions are respected: on November 1, on Angel Day, when the dead children are commemorated, at the house of my friends lined up, it seems, all the children of San Luis - the family arranged tricky-tricky , a ritual of treating children with sweets, which the Mexicans borrowed at Halloween, slightly correcting its original, hard-to-pronounce name treat-or-trick . Women appeared in the traditional image of Katrina for the Day of the Dead, a symbol of death - in black dresses and hats with a veil, with faces painted like skulls (it should be noted that special make-up for this occasion in Mexico is very high quality - it was possible to wipe off the “mask of death” only in the morning ).

In the north of Mexico, which is considered more Americanized than the south and center, on the occasion of the Day of the Dead, city carnivals are not arranged. But the traditions are respected: on November 1, on Angel Day, when the dead children are commemorated, at the house of my friends lined up, it seems, all the children of San Luis - the family arranged tricky-tricky , a ritual of treating children with sweets, which the Mexicans borrowed at Halloween, slightly correcting its original, hard-to-pronounce name treat-or-trick . Women appeared in the traditional image of Katrina for the Day of the Dead, a symbol of death - in black dresses and hats with a veil, with faces painted like skulls (it should be noted that special make-up for this occasion in Mexico is very high quality - it was possible to wipe off the “mask of death” only in the morning ).

The next day, a friend suggested that we go to the cemetery together - her friend's father died a month ago, and he was going to celebrate the Day of the Dead there. We knew each other with a hat, he did not speak English at all, and I spoke Spanish very poorly, but it was stupid to refer to the terrible internal awkwardness on such a holiday. Even though the idea of dancing on graves still made me stupor, I already wanted to pass this test of openness to foreign cultures.

We knew each other with a hat, he did not speak English at all, and I spoke Spanish very poorly, but it was stupid to refer to the terrible internal awkwardness on such a holiday. Even though the idea of dancing on graves still made me stupor, I already wanted to pass this test of openness to foreign cultures.

***

The tradition of celebrating the Day of the Dead in Mexico is rooted in the pre-Columbian past and is closely connected with the culture of the peoples of Mesoamerica - the Olmecs, Toltecs, Aztecs, Mayans. All of them were united by a kind of cult around death: there were no cemeteries in the usual sense, and the dead were buried right under residential buildings. This practice literally brought the living and the dead closer together: the graves were not walled up, relatives regularly “visited” the dead and brought offerings to them. The deceased were perceived as intermediaries between the world of life and death.

The Aztecs believed that these two hypostases are natural forces that set the world in motion, necessary components of regeneration. After all, in order to get food, it was necessary to kill an animal or a plant - which means that death gave life.

The Indians believed that a person has three souls, each of which could go to the afterlife, turn into a divine power, or stay between two worlds to give strength to the surviving loved ones.

Many of the Aztec rituals in honor of the dead, such as the worship of the death goddess Mictlancihuatl, who was depicted as a woman with a skull for a head, smoking incense, offering food and gifts to the dead ofrendas - have become an important part of the celebration of the Day of the Dead. But, of course, in its modern form, this holiday took shape as a result of a mixture of pre-Columbian and Spanish Catholic practices, which, paradoxically, harmoniously complemented each other. For example, the popular plot of religious Spanish painting Danza Macabra (“Dance of Death”), in which death was depicted dancing with the living, perfectly superimposed on the Indian depiction of death in the form of a skull. The Spaniards encouraged the Indians to hold rituals to honor the dead on Catholic holidays - All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day, which were celebrated on November 1 and 2 (before that, Indian celebrations in honor of the dead took place in August).

The Spaniards encouraged the Indians to hold rituals to honor the dead on Catholic holidays - All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day, which were celebrated on November 1 and 2 (before that, Indian celebrations in honor of the dead took place in August).

Early 1900s The authorities of the already independent Mexico declared the Day of the Dead an official holiday in order to unite the nation against the backdrop of political divisions that reigned. So the fiesta, traditional for the south of the country, spread throughout its territory and eventually began to attract hundreds of thousands of tourists to the country. Ten years ago, in 2008, the Day of the Dead was inscribed by UNESCO on the List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Photo: Maria Zhelikhovskaya***

Trying to mentally put all known Spanish words of sympathy into more or less harmonious phrases, as we walked out of the parking lot, I experienced a strange mixture of fear of someone else's grief and my own hypocrisy. Eight years ago, my own father died suddenly, and the memories of the depression that did not leave me for a whole year after that did not fit well with the thoughts that in such a state one could communicate with the curious and see the holiday around. It was really fun at the San Luis cemetery: before we found our friend, we had to make our way through armfuls of flowers, whole orchestras of norteños and many people at the graves - they were talking loudly, eating, drinking. Our friend was sitting in a large company of relatives and was tipsy in every sense. They began to hug us tightly, immediately poured beer and put tamales on plates.

Eight years ago, my own father died suddenly, and the memories of the depression that did not leave me for a whole year after that did not fit well with the thoughts that in such a state one could communicate with the curious and see the holiday around. It was really fun at the San Luis cemetery: before we found our friend, we had to make our way through armfuls of flowers, whole orchestras of norteños and many people at the graves - they were talking loudly, eating, drinking. Our friend was sitting in a large company of relatives and was tipsy in every sense. They began to hug us tightly, immediately poured beer and put tamales on plates.

***

"If you do not light a candle for a dead man, he will have to set fire to his own finger in order to find his way home," says a popular belief among the Indians of southern Mexico. Dia de Muertos is not just an occasion to commemorate the dead. It is believed that on this day the deceased come home to visit their relatives - and they, in turn, should take care to ensure that the return, albeit temporary, becomes easy and pleasant. To do this, in houses, and in some cities in squares and cemeteries, altars are built with photographs of deceased relatives. They decorate them with great imagination, decorate them with flowers - pink celosia, white gypsophila, red carnations and bright orange marigolds inherited from the Aztecs cempasúchil . From their petals, a path is poured up to the altar from the threshold of the house or yard, which will show the right way to the deceased. Offerings are placed on the altar - ofrendas .

To do this, in houses, and in some cities in squares and cemeteries, altars are built with photographs of deceased relatives. They decorate them with great imagination, decorate them with flowers - pink celosia, white gypsophila, red carnations and bright orange marigolds inherited from the Aztecs cempasúchil . From their petals, a path is poured up to the altar from the threshold of the house or yard, which will show the right way to the deceased. Offerings are placed on the altar - ofrendas .

Traditionally, the altar should contain four elements: water to quench the thirst of the deceased during the long journey from the realm of the dead Mictlan; fire (candles) to light the way to earth; the wind, which is symbolized by garlands of colored carved paper papel picado , to create coolness, and unite the dead with the living earth, which is personified by food. It is usually a sweet, yeasty "bread of the dead" pan de muerto , tamales - Mexican "dumplings" stuffed with meat and cornmeal, boiled in corn or banana leaves, hot corn drink atolle, fruit, mole chocolate sauce, and sweets in the form of sugar skulls. However, on the altar you can find almost everything that the deceased loved, right down to cans of Coca-Cola, cigarettes and baseball t-shirts! Incense is also part of the tradition, and since the time of the Aztecs, copal has been used for this, a resin secreted by tropical trees of the legume family.

However, on the altar you can find almost everything that the deceased loved, right down to cans of Coca-Cola, cigarettes and baseball t-shirts! Incense is also part of the tradition, and since the time of the Aztecs, copal has been used for this, a resin secreted by tropical trees of the legume family.

But still, the main and most replicated symbols of the Day of the Dead are the artistic representation of the skull, which is called the calavera, and Katrina, a skeleton in a woman's dress and hat. These images, which are considered folk, actually have an author - Mexican cartoonist José Guadelupe Posada. It was he who turned the image of the skeleton into a work of art, drawing calaveras in the images of people, including politicians, for magazines and newspapers. At 1910 d. Posada printed a lithograph called La Calavera Garbancera - "Elegant Skeleton". The drawing revealed a lady shy of her Indian roots, dressed in French fashion and with copious make-up to appear whiter.

In 1948, Diego Rivera, who considered Posada his inspiration, painted his famous mural "Sunday Evening Dream in Alameda Park", dedicated to the colonial history of Mexico, in which he quoted a satirical drawing of Posada, giving his heroine the name La Catrina (in the slang of that time - the name of an expensively dressed rich man). Since then, Katrina and the calavera have become one of the most popular images of Mexican identity.

Despite the fact that the main tradition of the Day of the Dead is a visit to the cemetery, which turns into a party, different states and cities have their own customs. Mexico City has recently held a carnival, and the largest altar in the country is being built on the university campus and the local Indian saint, a pilgrim child, is being celebrated.0007 Nino Pa . Oaxaca is famous for the calenda tradition, a street procession with puppets, dancers and music. In Michoacán they dance La Danza de los Tecuanes - “Dance of the Jaguars”, depicting the hunt for these animals, and La Danza de los Viejitos - “Dance of the Little Old Men”, in which teenagers dressed as old people first walk with their backs bent, and then suddenly jump up and start moving vigorously. And the Purépecha Indians, who inhabit the northwest of this state, prepare for the holiday several weeks in advance: young boys, tatakeres are sent, often illegally, to the plantations to dig marigolds or to the forest to cut trees for the construction of altars in the village squares. In the town of San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato state, they hold a colorful four-day festival La Calaca dedicated to skulls, and in Guadalajara they hold a festival at the Belen cemetery and it seems that every single local woman is dressed as Katrina! In Chiapas, in the village of San Juan Chamula, where the Tzotzili Indians live, the least assimilated after the conquest, they organize a festival K'Anima , during which the locals ring the church bell, believing that it attracts the souls of the dead, and then go to the cemetery to play harps and guitars. San Sebastian, Yucatán hosts the Mucbipollo festival, the name given to chicken cooked in an earthen oven in a sauce made from tomatoes and cornmeal.

And the Purépecha Indians, who inhabit the northwest of this state, prepare for the holiday several weeks in advance: young boys, tatakeres are sent, often illegally, to the plantations to dig marigolds or to the forest to cut trees for the construction of altars in the village squares. In the town of San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato state, they hold a colorful four-day festival La Calaca dedicated to skulls, and in Guadalajara they hold a festival at the Belen cemetery and it seems that every single local woman is dressed as Katrina! In Chiapas, in the village of San Juan Chamula, where the Tzotzili Indians live, the least assimilated after the conquest, they organize a festival K'Anima , during which the locals ring the church bell, believing that it attracts the souls of the dead, and then go to the cemetery to play harps and guitars. San Sebastian, Yucatán hosts the Mucbipollo festival, the name given to chicken cooked in an earthen oven in a sauce made from tomatoes and cornmeal.

But the most extravagant custom is practiced in the town of Pomuch in the state of Campeche, which is inhabited by the Maya Indians. Here, three or four years after the funeral, the dead are taken out of the graves, and on the eve of the holiday, their bones are literally washed. This occupation takes almost a day, then the remains are put into wooden boxes and carried to the cemetery, where there is a special place for their storage. On the Day of the Dead, they are taken out, laid out on the altar, wrapped in napkins with beautifully embroidered patterns and the names of the dead, and placed next to offerings.

Photo: Maria Zhelikhovskaya***

Midnight passed, but the fun in the cemetery did not subside. Still, Mexican syncretism works in an amazing way. The traditional Spanish stoic attitude towards death, the concept of the sadness of earthly existence and the benefits of suffering, did not take root here. Even deceased loved ones are called by the Mexicans in a diminutive way - muertitos . In a country where the Inquisition did not work, it is not customary to challenge death to a duel; here they would rather pat her on the shoulder, drink tequila with her and go on enjoying life.

In a country where the Inquisition did not work, it is not customary to challenge death to a duel; here they would rather pat her on the shoulder, drink tequila with her and go on enjoying life.

Guests came and went, and our friend's father's grave was overgrown with a pile of plastic plates and cups. The slabs were separated from each other only by curb stones, and this created the impression of a large common feast. Rollerblading children squealing furiously along the path, obscure Spanish speech merged with the music, and at some point I found myself stomping to the beat. Father, who joked always and under any circumstances, would surely pat my neck and smile. And in general, it already seemed that both of them - both the father of our friend and my own - should be sitting somewhere nearby. At the next table. Drink beer, joke, laugh and not be afraid of the language barrier.

And suddenly my heart suddenly felt light.

Day of the Dead in Mexico: Interesting Facts - Mexican Culture

Día de los Muertos, or the Day of the Dead, is a celebration of life and death. Although the holiday originated in Mexico, today it is celebrated throughout Latin America with colorful calaveras (skulls) and calacas (skeletons). The ceremonies abound with symbolic rituals and lavish processions.

Although the holiday originated in Mexico, today it is celebrated throughout Latin America with colorful calaveras (skulls) and calacas (skeletons). The ceremonies abound with symbolic rituals and lavish processions.

The Day of the Dead is not the Mexican version of Halloween. Although these two annual holidays are related, they are very different in tradition and spirit. While Halloween is a dark night of horror and mischief, the Day of the Dead celebration unfolds amid an explosion of color and life-affirming joy. The main theme is the same - death, but the essence of the Day of the Dead is different - to demonstrate love and respect for the deceased family members. In towns across Mexico, residents put on unusual make-up and don skeleton costumes, hold parades and parties, sing, dance and make offerings to departed loved ones. They don't mourn, they enjoy life.

In 2008, UNESCO recognized the importance of the Mexican Day of the Dead by adding this holiday to its list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Today, the Day of the Dead is celebrated by Mexicans of all religious and ethnic groups, but in essence it is a confirmation that the descendants of indigenous peoples live among us.

Today, the Day of the Dead is celebrated by Mexicans of all religious and ethnic groups, but in essence it is a confirmation that the descendants of indigenous peoples live among us.

History

The celebration of the Day of the Dead originated several thousand years ago among the Aztecs, Toltecs and other Nahua peoples, who considered mourning the dead disrespectful. For these pre-Hispanic cultures, death was only a natural phase of a long life cycle. The dead continued to be considered members of the community, memories of them were kept in memory, during the Day of the Dead, the dead temporarily returned to earth, and their life continued.

Today's Día de los Muertos is a mixture of pre-Hispanic religious rites and Christian holidays. It is usually celebrated for two days, November 1 and 2 - on All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day according to the Catholic calendar, that is, around the time of the autumn corn harvest. However, the holiday is not limited to these two days. Families in communities begin to meet and honor deceased relatives even before the start of mass events, and in some regions, celebrations can continue on other days, until the end of November.

Families in communities begin to meet and honor deceased relatives even before the start of mass events, and in some regions, celebrations can continue on other days, until the end of November.

When do the souls of the dead come

On what days do the souls of the dead come to earth? It is believed that this happens at noon.

October 27: On this day, pets return from the afterlife, so water and some food are usually placed in one of the corners of the house.

October 28: The souls of those who died suddenly, as a result of an accident or by force, return. Lonely souls also come on this day. For them, they put a candlestick with a candle and a white flower.

October 29: Drowned Day.

October 30: A lone candle and a glass of water are placed for forgotten souls or those who have no family.

October 31: Memorial day for children, but only unborn or unbaptized.

November 1: on this day we remember all those who died or perished in childhood.

November 2: Day of remembrance for all adults, grandparents or great-grandparents and in general for all ancestors. This is the traditional day to visit the cemetery. Also on this day, the souls of all the dead begin to return to the afterlife.

Altar

The central element of the celebration is the altar, or offrenda. Altars are placed in houses, in cemeteries and in general everywhere. These are not altars for worship. Rather, they are meant to welcome the arrival of spirits back to the realm of the living. The altars are filled with offerings - water to quench the thirst of souls after a long journey, food to satisfy their hunger, memorable family photographs, and a candle for each deceased relative. If a child is commemorated, there will definitely be small toys on the altar. Marigolds are the main flowers that adorn the altar. Scattered from the altar to the grave, marigold petals guide wandering souls to their resting place. The smoke from the incense, made from the resin of the sacred kopal tree, conveys praises and prayers and purifies the area around the altar.

Loading

Watch on Instagram

Calavera

Calavera means skull. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the term "calavera" was used for short, humorous poems that were sarcastic epitaphs carved on tombstones that ridiculed the living. Usually such epitaphs were taken from newspapers of that time. Literary calaveras eventually became a popular part of Day of the Dead celebrations. You will find these smart, poignant verses in print, heard from others or seen on television.

Katrina

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Mexican political cartoonist and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada created an etching to accompany the literary calavera. Posada dressed his personification of death - a skeleton - in fancy French clothing and named it Calavera Garbancera. In this way, he ridiculed Mexican society, imitating European sophistication. "Todos somos calaveras," a quote commonly attributed to Posada, means "we are all skeletons. " Hidden behind all our artificial trappings is that we are all the same.

" Hidden behind all our artificial trappings is that we are all the same.

In 1947, the artist Diego Rivera presented Posada's stylized skeleton in his masterpiece mural Dream of a Sunday in Alameda Park. The skeleton was wearing a large woman's hat, and Rivera named the presented female image Katrina, slang for "rich". Today, the calavera Catrina, or elegant skull, is the most famous symbol of the Day of the Dead.

Food of the dead

Traveling from the underworld back to the world of the living, souls must satisfy their hunger and thirst. At least that's how it is in Mexico. Families place favorite foods of deceased loved ones or symbolic offerings on the altar. The latter have become the most common over the years and can be pre-purchased at any grocery store.

Pan de muerto, or bread of the dead, is a typical sweet bread (pan dulce), often containing anise seeds and decorated with dough bones and skulls. Bones can be arranged in a circle, as if in a circle of life. Tiny tears from the dough symbolize sadness.

Tiny tears from the dough symbolize sadness.

Sugar skulls are part of the sugar art tradition brought by 17th century Italian missionaries. Pressed into shapes and adorned with edible flowers, they come in all sizes, colors and levels of complexity. Some of them are real works of art.

Mandatory attributes of the altar on the Day of the Dead are traditional drinks. For example, pulque is a sweet fermented drink made from agave juice, atole is a liquid warm gruel made from cornmeal with the addition of unrefined cane sugar, cinnamon and vanilla. Hot chocolate is also customary to bring to the souls of the dead.

Loading

Watch on Instagram

Costumes

The Day of the Dead is an extremely popular holiday. Celebrations take place on the streets and squares at any time of the day or night. Dressing up in skeleton costumes is just part of the fun. The faces of people of all ages are artfully painted to resemble skulls. Imitating the calavera Katrina, participants in parades and parties wear costumes and masquerade dresses. Many wear shells or other objects to make noise - this should increase the excitement, as well as wake the dead and keep them around all the time during the fun.

Imitating the calavera Katrina, participants in parades and parties wear costumes and masquerade dresses. Many wear shells or other objects to make noise - this should increase the excitement, as well as wake the dead and keep them around all the time during the fun.

Paper carvings

You must have seen these beautiful paper crafts many times in Mexican restaurants and public events, not just on the Day of the Dead. The literal translation of Papel picado - "perforated paper" - perfectly describes how it is made. Craftsmen fold colored tissue paper into dozens of layers and then perforate the layers with a hammer and chisel. Papel picado is used not only during the Day of the Dead, but plays an important role in the holiday. Decorating altars and streets, this art personifies the wind and the fragility of life.

Day of the Dead today

Thanks to the recognition of UNESCO, the Day of the Dead is becoming more popular not only in Mexico, but also increasingly abroad. If you find yourself in Mexico City these days, be sure to watch the grandiose parade on the central avenue. However, celebrations are held throughout the city. Countless communities celebrate the Day of the Dead throughout Mexico, but styles and customs vary by region and by the prevailing pre-Hispanic culture. Here are a few places that stand out for their colorful and touching celebrations.

If you find yourself in Mexico City these days, be sure to watch the grandiose parade on the central avenue. However, celebrations are held throughout the city. Countless communities celebrate the Day of the Dead throughout Mexico, but styles and customs vary by region and by the prevailing pre-Hispanic culture. Here are a few places that stand out for their colorful and touching celebrations.

Loading

Watch on Instagram

One of the most colorful Day of the Dead celebrations each year takes place in Pátzcuaro, a municipality in the state of Michoacán, about 360 kilometers west of Mexico City. Indigenous people from the countryside gather on the shores of Lake Patzcuaro, where they sit in canoes adorned with lit candles and sail to a tiny island called Janicio to hold a nightly vigil in their ancestral graveyard.

Mixquic. In this suburb of Mexico City, the bells of an ancient Augustinian monastery toll, and members of the community with candles and flowers go to the local cemetery, where they clean and decorate the graves of their loved ones.