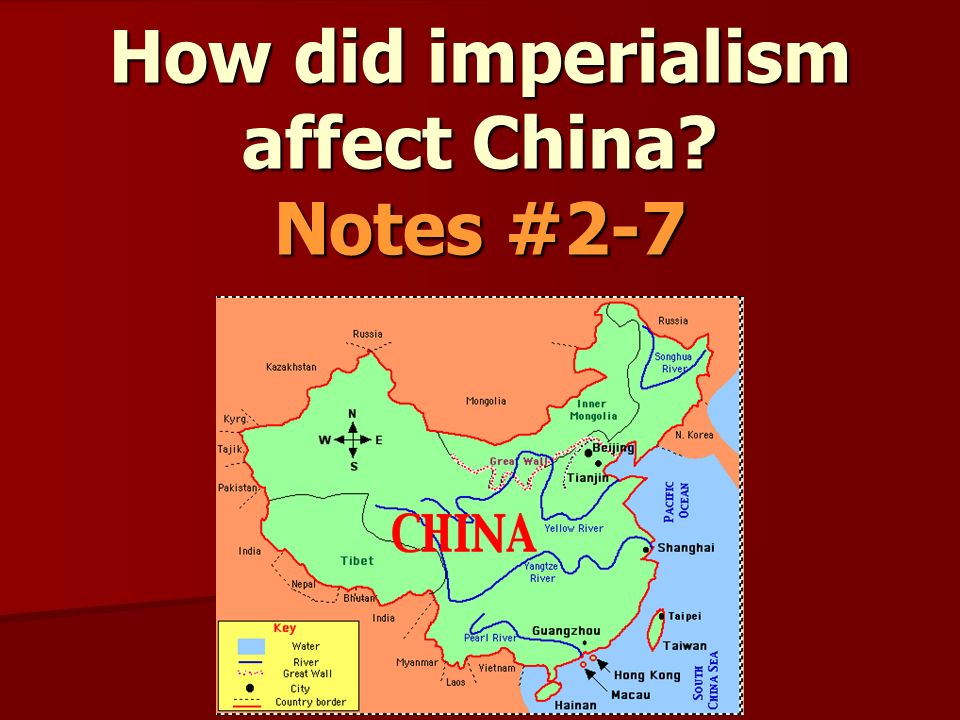

How does the one child policy affect china

One-child policy | Definition, Start Date, Effects, & Facts

Top Questions

What is the one-child policy?

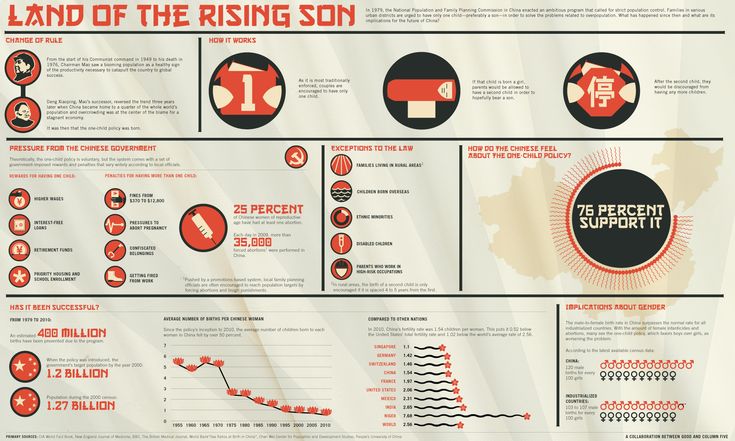

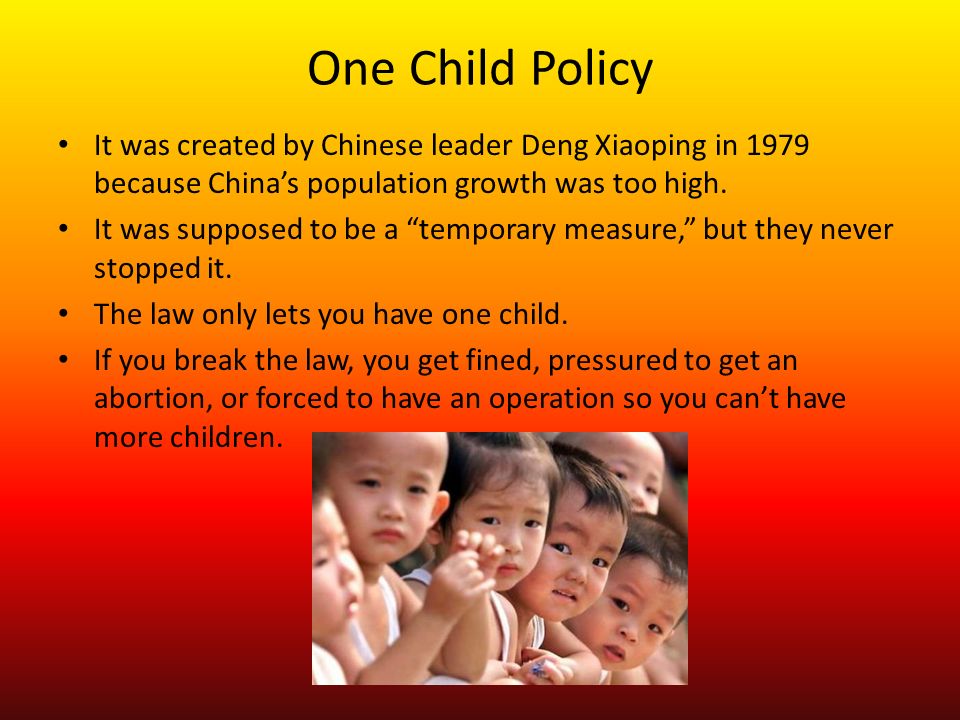

The one-child policy was a program in China that limited most Chinese families to one child each. It was implemented nationwide by the Chinese government in 1980, and it ended in 2016. The policy was enacted to address the growth rate of the country’s population, which the government viewed as being too rapid. It was enforced by a variety of methods, including financial incentives for families in compliance, contraceptives, forced sterilizations, and forced abortions.

When was the one-child policy introduced?

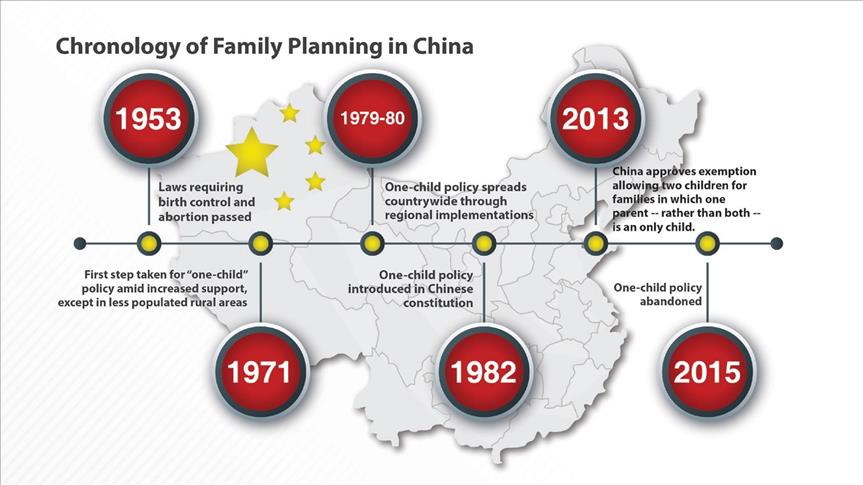

September 25, 1980, is often cited as the official start of China’s one-child policy, although attempts to curb the number of children in a family existed prior to that. Birth control and family planning had been promoted from 1949. A voluntary program introduced in 1978 encouraged families to have only one or two children. In 1979 there was a push for families to limit themselves to one child, but that was not evenly enforced across China. The Chinese government issued a letter on September 25, 1980, that called for nationwide adherence to the one-child policy.

Why is the one-child policy controversial?

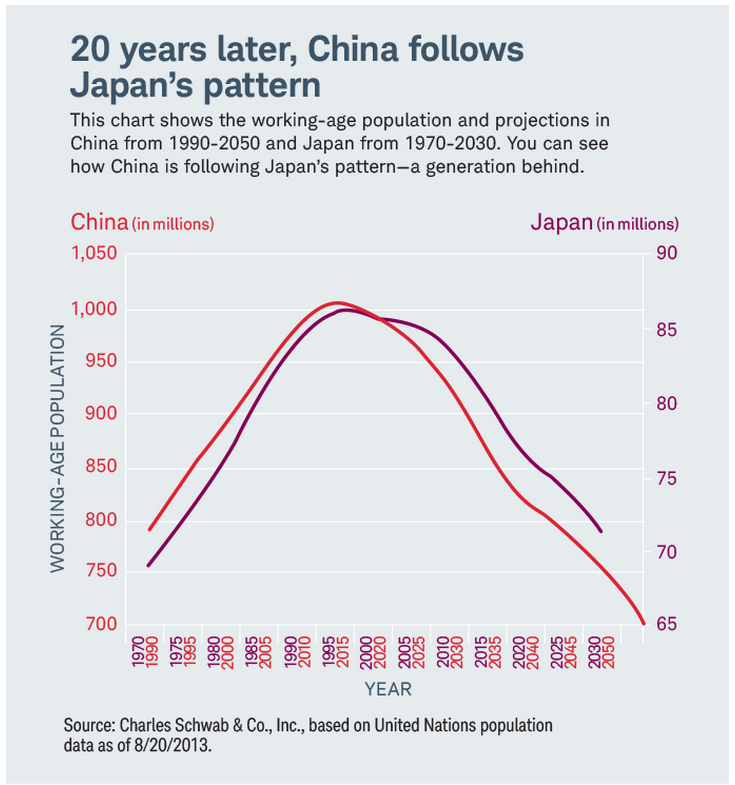

China’s one-child policy was controversial because it was a radical intervention by government in the reproductive lives of citizens, because of how it was enforced, and because of some of its consequences. Although some of the government’s enforcement methods were comparatively mild, such as providing contraceptives, millions of Chinese had to endure methods such as forced sterilizations and forced abortions. Long-term consequences of the policy included a substantially greater number of males than females in China and a shrinking workforce.

When did the one-child policy end?

The end of China’s one-child policy was announced in late 2015, and it formally ended in 2016. Beginning in 2016, the Chinese government allowed all families to have two children, and in 2021 all married couples were permitted to have as many as three children.

Beginning in 2016, the Chinese government allowed all families to have two children, and in 2021 all married couples were permitted to have as many as three children.

What are the consequences of the one-child policy?

There have been many consequences to China’s one-child policy. The country’s fertility rate and birth rate both decreased after 1980; the Chinese government estimated that some 400 million births had been prevented. Because sons were generally favoured over daughters, the sex ratio in China became skewed toward men, and there was a rise in the number of abortions of female fetuses along with an increase in the number of female babies killed or placed in orphanages.

After the one-child policy ended in 2016, China’s birth and fertility rates remained low, leaving the country with a population that was aging rapidly and a workforce that was shrinking. With data from China’s 2020 census highlighting an impending demographic and economic crisis, the Chinese government announced in 2021 that married couples would be allowed to have as many as three children.

one-child policy, official program initiated in the late 1970s and early ’80s by the central government of China, the purpose of which was to limit the great majority of family units in the country to one child each. The rationale for implementing the policy was to reduce the growth rate of China’s enormous population. It was announced in late 2015 that the program was to end in early 2016.

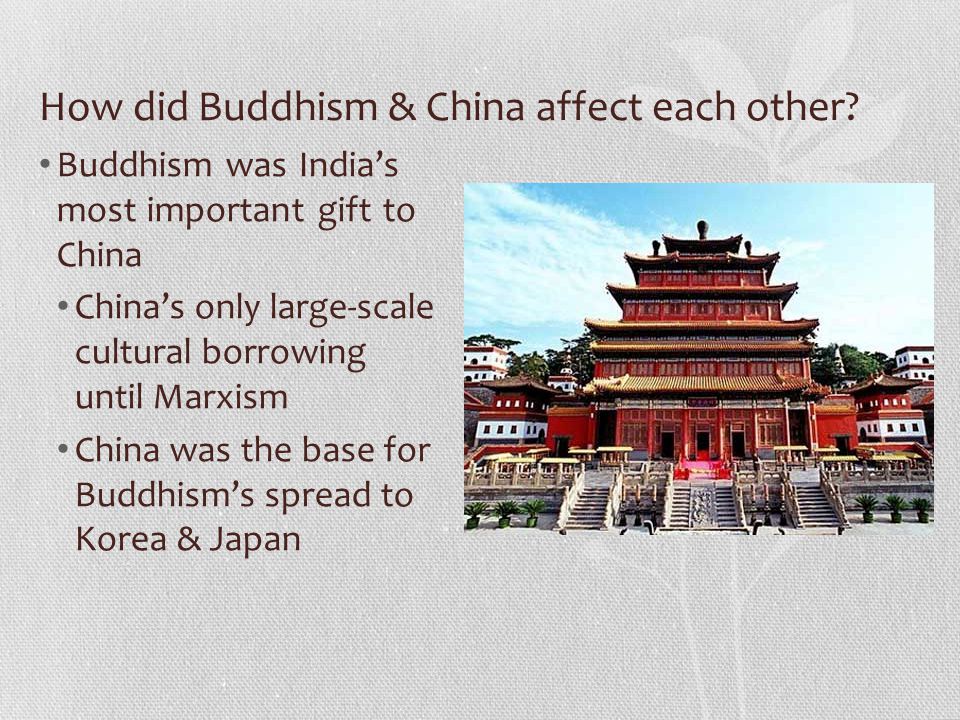

China began promoting the use of birth control and family planning with the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, though such efforts remained sporadic and voluntary until after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. By the late 1970s China’s population was rapidly approaching the one-billion mark, and the country’s new pragmatic leadership headed by Deng Xiaoping was beginning to give serious consideration to curbing what had become a rapid population growth rate. A voluntary program was announced in late 1978 that encouraged families to have no more than two children, one child being preferable. In 1979 demand grew for making the limit one child per family. However, that stricter requirement was then applied unevenly across the country among the provinces, and by 1980 the central government sought to standardize the one-child policy nationwide. On September 25, 1980, a public letter—published by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party to the party membership—called upon all to adhere to the one-child policy, and that date has often been cited as the policy’s “official” start date.

In 1979 demand grew for making the limit one child per family. However, that stricter requirement was then applied unevenly across the country among the provinces, and by 1980 the central government sought to standardize the one-child policy nationwide. On September 25, 1980, a public letter—published by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party to the party membership—called upon all to adhere to the one-child policy, and that date has often been cited as the policy’s “official” start date.

The program was intended to be applied universally, although exceptions were made—e.g., parents within some ethnic minority groups or those whose firstborn was handicapped were allowed to have more than one child. It was implemented more effectively in urban environments, where much of the population consisted of small nuclear families who were more willing to comply with the policy, than in rural areas, with their traditional agrarian extended families that resisted the one-child restriction. In addition, enforcement of the policy was somewhat uneven over time, generally being strongest in cities and more lenient in the countryside. Methods of enforcement included making various contraceptive methods widely available, offering financial incentives and preferential employment opportunities for those who complied, imposing sanctions (economic or otherwise) against those who violated the policy, and, at times (notably the early 1980s), invoking stronger measures such as forced abortions and sterilizations (the latter primarily of women).

In addition, enforcement of the policy was somewhat uneven over time, generally being strongest in cities and more lenient in the countryside. Methods of enforcement included making various contraceptive methods widely available, offering financial incentives and preferential employment opportunities for those who complied, imposing sanctions (economic or otherwise) against those who violated the policy, and, at times (notably the early 1980s), invoking stronger measures such as forced abortions and sterilizations (the latter primarily of women).

The result of the policy was a general reduction in China’s fertility and birth rates after 1980, with the fertility rate declining and dropping below two children per woman in the mid-1990s. Those gains were offset to some degree by a similar drop in the death rate and a rise in life expectancy, but China’s overall rate of natural increase declined.

China's Former 1-Child Policy Continues To Haunt Families : NPR

The legacy of China's one-child rule is still painfully felt by many of those who suffered for having more children. Ran Zheng for NPR hide caption

Ran Zheng for NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Ran Zheng for NPR

The legacy of China's one-child rule is still painfully felt by many of those who suffered for having more children.

Ran Zheng for NPR

Editor's note: This story contains descriptions that may be disturbing.

LINYI, China — Outside, rain falls. Inside, a middle-school student completes his homework. His mother watches him approvingly.

She is especially protective of him. He's the youngest of three children this mother had under China's one-child policy.

Giving birth to him was a huge risk — and she took no chances. She carried her son to term while hiding in a relative's house. She wanted to avoid the "family planning officials" in her home village, just outside Linyi, a city of 11 million in China's northern Shandong province, where the policy's enforcement was especially violent.

She carried her son to term while hiding in a relative's house. She wanted to avoid the "family planning officials" in her home village, just outside Linyi, a city of 11 million in China's northern Shandong province, where the policy's enforcement was especially violent.

What was she hiding from? What could the family planning officials have done to her? She demurs, her voice growing quiet. "All we can do is go on living," she says. "There is no use in trying to make sense of society."

A mother and a grandmother take care of a child in Beijing on Jan. 1, 2016. Married couples in China in 2016, were allowed to have two children, after concerns over an aging population and shrinking workforce ushered in an end to the country's controversial one-child policy. Fred Dufour/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

Fred Dufour/AFP via Getty Images

Her son is part of the last generation of children in China whose births were ruled illegal at the time. Anxious that rapid population growth would strain the country's welfare systems and state-planned economy, the Chinese state began limiting how many children families could have in the late 1970s.

Anxious that rapid population growth would strain the country's welfare systems and state-planned economy, the Chinese state began limiting how many children families could have in the late 1970s.

The limit in most cases was just one child. Then in 2016, the state allowed two children. And in May, after a new census showed the birth rate had slowed, China raised the cap to three children. State media celebrated the news.

But the legacy of the one-child rule is still painfully felt by many parents who suffered for having multiple children. For some, the pain is still too much to bear.

"It has been so many years, and I have let the pain go," the mother of three says, eyes downcast. "If you carry it with you all the time, it gets too tiring."

A mother's quandary

One night in August 2008, the mother made a fateful decision. Her body was giving her all the telltale signs that she was pregnant — again.

She already had two children and had gone through four abortions afterward, to avoid paying the ruinously high "social maintenance fee" demanded from families as penalty when they contravened birth limits.

Medical staff massage babies at an infant care center in Yongquan, in Chongqing municipality, in southwest China, on Dec. 15, 2016. China had 1 million more births in 2016 than in 2015, following the end of the one-child policy. AFP via Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

AFP via Getty Images

But this time she felt differently.

"I had already had two children but my heart just did not feel right," says the woman, now in her 50s, who works part time in a canning factory. NPR isn't using her name to protect her identity because of the trauma she suffered. "I thought this is it — if I do not have this child, my body will not be able to have any more."

Officials in her village were actively policing families under the one-child policy. Enforcement of the policy had begun to loosen by the early 2000s, as horrific stories of forced abortions and botched sterilizations caused policymakers to rethink the rule. But starting in 2005, the authorities began enforcing the policy with a renewed ferocity in Linyi.

Enforcement of the policy had begun to loosen by the early 2000s, as horrific stories of forced abortions and botched sterilizations caused policymakers to rethink the rule. But starting in 2005, the authorities began enforcing the policy with a renewed ferocity in Linyi.

So the mother went into hiding to carry her son to term. One night, family planning officials approached her husband, intending to pressure him and his wife into ending the pregnancy. He used a pickax to drive them off and was imprisoned for that for half a year.

An old friend of hers, the blind lawyer Chen Guangcheng, knows full well what she and tens of thousands of other women in Linyi city went through.

Chinese parents, who have children born outside the country's one-child policy, protest outside the family planning commission in an attempt to have their fines canceled in Beijing, on Jan. 5, 2016. For decades, China's family planning policy limited most urban couples to one child and rural couples to two if their first was a girl. Ng Han Guan/AP hide caption

Ng Han Guan/AP hide caption

toggle caption

Ng Han Guan/AP

"The doctors would inject poison directly into the baby's skull to kill it," Chen says, drawing on recordings he made of interviews with hundreds of women and their families in Linyi. "Other doctors would artificially induce labor. But some babies were alive when they were born and began crying. The doctors strangled or drowned those babies."

The terror of such enforcement of birth limits was widespread in Linyi, even if residents were not themselves planning on giving birth.

"Officials would kidnap you if you tried to have two children. If you were hiding and they could not find you, they would kidnap your elder relatives and make them stand in cold water, in the winter," remembers Lu Bilun, a resident.

Lu says the harassment became so savage that elderly residents of Linyi became afraid to leave their homes out of fear they might be kidnapped. Lu says he paid a 4,000 yuan fine to have his second son in 2006 (about $500 at the time), after hiding his wife for months. "This was not your average level of policy enforcement. It was vicious," he says.

Chen, the lawyer, mounted a class action lawsuit on behalf of Linyi's women. The suit led to an apology from the authorities in Linyi and a reduction in the kidnappings, beatings and forced abortions.

Children ride a toy train at a shopping mall in Beijing, on Oct. 30, 2015. China's decision to abolish its one-child policy offered some relief to couples and to sellers of baby-related goods, but the government hasn't lifted birth limits entirely. Andy Wong/AP hide caption

toggle caption

Andy Wong/AP

But the Chinese government punished Chen for his activism by imprisoning him, then trapping him for nearly three years in his home, in a village just outside Linyi.

In 2012, Chen escaped by scaling a wall and running to the next village, despite being blind and having broken his foot during the escape. There, he was picked up by supporters and driven to the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. He was able to fly to the U.S. after weeks of tense negotiation. Today, he lives in Maryland with his family.

The price of defiance

"The policy was wrong and what we did with Chen was right," says a neighbor of Chen, the lawyer who sued the city of Linyi. The man wants to remain unnamed because he believes he could be harassed again for speaking of that time.

In the 1990s, he says, family planning officials ambushed him in his home at night and beat him with sticks in an effort to convince his wife to abort their third son.

Chinese lawyer Chen Guangcheng attends a rally to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre June 4, 2019, at the West Lawn of the U.S. Capitol. Chen had been persecuted and detained in China after his work advising villagers and speaking out official abuses under the one-child rule. Alex Wong/Getty Images hide caption

Alex Wong/Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

Alex Wong/Getty Images

"Our country's leaders did not want us to have children and I didn't know why, but we could not do anything about it," he sighs.

He and his wife persevered and had three sons. They did not officially register the last two to avoid paying a fine, but the father says he still paid a bribe to family planning officials to avoid further harassment. These economic penalties depleted his life savings, a financial impact that compounded over the ensuing years.

The policy permeates through Chinese society in other, sometimes unexpected ways. Because many prioritized having a son over a daughter, orphanages experienced a surge in baby girls who were abandoned or put up for adoption. Single's Day, China's biggest online shopping holiday — akin to Black Friday in the U.S. — is a recognition of the many bachelors who are unable to find partners in a gender-skewed society.

Single's Day, China's biggest online shopping holiday — akin to Black Friday in the U.S. — is a recognition of the many bachelors who are unable to find partners in a gender-skewed society.

"A very unbalanced population gender-wise has also led to a rise in property prices in major cities because families of men have bought apartments to make their sons eligible in a marriage market where there are millions of missing women," says Mei Fong, who wrote a book on the one-child rule. "These effects will be felt in the generation ahead."

A child walks near government propaganda one of which reads "1.3 billion people united" on the streets of Beijing, China, Tuesday, March 8, 2016. Ng Han Guan/AP hide caption

toggle caption

Ng Han Guan/AP

According to the census conducted last year, the population is aging and there are fewer young children and working-age people, a major demographic shift that comes with its own economic strains. That's pushing policymakers to consider raising the official retirement age — currently 60 for men and 55 for women — for the first time in 40 years.

That's pushing policymakers to consider raising the official retirement age — currently 60 for men and 55 for women — for the first time in 40 years.

Yet the authorities still only allow couples to have three children. Why won't China remove all caps?

"Despite all the overwhelming demographic evidence, they're saying, 'We need to control you,'" says the author, Fong. Anxious about already strained public education and health care systems, China's leadership is reportedly considering ditching limits entirely. It has been slow to completely dismantle its massive family planning bureaucracy built up over the past four decades. And according to an Associated Press investigation, it continues to impose stricter controls over births — including forced sterilizations — among ethnic minorities, like the Turkic Uyghurs.

Some demographers in China argue that instituting birth limits was necessary for keeping birth rates low. But Stuart Gietel-Basten, a demographer at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, cautions there is no definitive answer. "There is only one China and there is only one one-child policy, so it is kind of impossible to say the real effect of that was [of the policy]," he says.

"There is only one China and there is only one one-child policy, so it is kind of impossible to say the real effect of that was [of the policy]," he says.

Families were already having fewer children in the 1970s, before the policy took force in 1979. "The one-child policy was not the only thing that happened in China in the 1980s and 1990s," Gietel-Basten says. "There was also rapid urbanization, economic growth, industrialization, female emancipation and more female labor force participation."

A man and a child are reflected on a glass panel displaying a tiger at the Museum of Natural History in Beijing, Dec. 2, 2016. Andy Wong/AP hide caption

toggle caption

Andy Wong/AP

It was worth the cost

The fact that the children are alive at all makes Chen, the lawyer, feel his seven years in prison and house arrest were all worth it.

"I really feel happy. Even if I had to go to prison and endure beatings, in the end, these children were able to survive. They must be in middle school or high school by now."

The mother of one of these middle schoolers holds her son close. Part of the reason she demurred when first speaking to NPR was because of how dearly her family fought for his birth.

Her worries these days are more mundane. She wants to start preparing for her son's marriage — a costly endeavor as rural families expect the husband to provide a material guarantee for any future wife.

"That requires buying them a car, an apartment. No one can afford that," she complains.

Her job at a nearby canning factory refuses to hire her full time, she says, because she is a mother of three and needs to leave every afternoon to pick up her son from school.

And so, ironically, now that people are allowed to have more children, they are increasingly reluctant to, because of the high cost of child care and education.

"Women have it all figured out now — they won't have more kids even when they're told to have more!" the mother laughs helplessly.

"People act in funny ways," she says. "There is no point in controlling them."

The Chinese authorities allowed families to have three children - RBC

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

Hide banners

What is your location ?

YesChoose other

Categories

Euro exchange rate as of December 10

EUR CB: 65.84 (+0.16) Investments, 09 Dec, 15:47

Dollar exchange rate on December 10

USD Central Bank: 62. 38 (-0.19) Investments, 09 Dec, 15:47

38 (-0.19) Investments, 09 Dec, 15:47

The President of Cuba received a delegation of American congressmen in Havana Politics, 04:44

Twitter will return the premium subscription on December 12 Technology and media, 04:44

The head of the VTsIOM considered the manifestation of cosmopolitanism among young people to be temporary Politics, 03:49

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

Egypt bans smoking hookah within 1 km of mosques, schools and gas stations Society, 03:10

I live “not my own” life: how to find a place for myself RBC and Gazprombank, 02:40

In Moscow, a case was opened against the mother who left the baby in the entrance Society, 02:01

Intelligence is about the sense of taste. How to evaluate it RBC and GALS, 01:41

How to evaluate it RBC and GALS, 01:41

Explaining what the news means

RBC Evening Newsletter

Subscribe

Explosions and gunfire sounded in northern Serbia Politics, 01:35

All pairs of the semi-finals of the World Cup have become known Sport, 01:06

The number of victims of the impact of the Armed Forces of Ukraine on Melitopol increased to 10 Politics, 01:04

Deputy head of the European Parliament suspended from work amid corruption case Politics, 00:49

Zelensky announced more than 1. 5 million people without electricity in the Odessa region Politics, 00:32

5 million people without electricity in the Odessa region Politics, 00:32

Classical architecture and comfort: what is the city-complex "Amaranth" RBC and Amaranth, 00:30

Kane missed a penalty in the match lost to France. What's Happening at the World Cup Sport, 00:15

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

Deposit "Best %"

Your income

0 ₽

Rate

0%

Apply online

Advertiser PJSC Sberbank.

Preliminary settlement at an increased rate. It is not a public offer.

The one-family-two-child policy is being abolished in the PRC. The birth rate in the world's most populous country has fallen sharply, reducing the number of able-bodied citizens and increasing the burden on the economy

Photo: Getty Images

Chinese authorities announced on Monday that married couples can now have three children. According to Xinhua News Agency, the corresponding decision was made at a meeting of the Politburo of the CPC Central Committee.

The authorities believe that the new permit will improve the demographic situation in the country, given the rapidly aging population.

The Chinese authorities began to engage in family planning policy due to the population explosion in the middle of the 20th century, when the population of China grew at a record pace. At first, state policy was focused on the distribution of contraceptives and the promotion of late marriages, but later the country's authorities began a policy of direct birth control. From 19In 1979, the PRC began to operate a one-child policy: with some exceptions, families were allowed to have no more than one child. Parents were subject to heavy fines for violations.

From 19In 1979, the PRC began to operate a one-child policy: with some exceptions, families were allowed to have no more than one child. Parents were subject to heavy fines for violations.

As a result of these decisions, population growth began to slow down in the 1990s. In 2013, families where at least one parent was an only child were allowed to have a second child. The one-child policy was finally abolished in 2015, when all families were allowed to have two children.

adv.rbc.ru

Due to the declining birth rate, China is facing a new problem - an aging population. The working-age population began to decline, the proportion of the elderly began to increase, which threatened a rapid increase in social spending. The Beijing Xiehe Medical Institute and the China Association for the Health of the Elderly predicted that by 2026, China will become an "aging society" with more than 14% of the population aged 65 and over.

In January 2020, China's National Bureau of Statistics reported that the country's birth rate had fallen to a record low since 1949 (the founding year of the People's Republic of China). This figure averaged 10.48 children per 1,000 people. In Russia, for comparison, in the same year it was only slightly lower - 10.2.

This figure averaged 10.48 children per 1,000 people. In Russia, for comparison, in the same year it was only slightly lower - 10.2.

In 2021, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, China's population was 1.412 billion people.

Despite the experience of China, in February 2021, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi also called the rapid population growth a problem for the country and demanded a reduction in the birth rate. “Why do you need a child whom you cannot feed and do not know how to get him a job? As a result, 50% live in slums,” the head of state said at the time.

8% - what a rate!

Learn about the contribution

2.3% - what an increase!

Learn about the contribution

10.3% - that's a win!

Learn about the contribution

This is DISCOVERY

Learn about the contribution

Authors

Tags

Research Store Analytics by topic "Children"

Deposit "Best %"

Your income

0 ₽

Rate

0%

Apply online

Advertiser PJSC Sberbank.

Preliminary settlement at an increased rate. It is not a public offer.

How China abandoned the "one family, one child" rule

Since the proclamation of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the ruling party has approved a population policy plan calling on the Chinese to have more children, she said. In many aspects, it was similar to the demographic policy of the USSR.

Until the 1970s, the Chinese authorities encouraged the Chinese to have several children, and the following statement was written on the birth certificate of each child: "One is too little, two is not enough, and three is just right." However, by the end of the decade, the government thought about family planning and decided that the optimal number of children for an exemplary couple was two. And in June 1979, an official order was issued "at the local level to apply practical measures to support married couples with one child. "

"

By the end of 1981, the Chinese population reached a billion people, and soon the authorities of the Celestial Empire proclaimed that the goal of China's population policy would be "birth control and improving the quality of the population."

In 1995, China's population policy encouraged couples to have fewer but healthier children. The Chinese government had a policy calling for couples to have only one child, but allowed couples to have two children under special conditions.

By 2000, in some regions of China, especially in economically developed cities, family planning policy became less rigid: for example, a couple could have two children if both mom and dad were the only children in their families (and after 2013 - if at least one parent).

In October 2015, planned changes to the current one-child law were published, allowing all families without exception to have two children. The law came into force on January 1, 2016.

According to Ms. Song Xiaomei, over the years of reforms and demographic policy, China has managed to develop the health care system, reduce child mortality and raise the status of women in society. However, until today, a Chinese woman who has decided to give birth to a child is afraid of losing her job or losing her salary after leaving the decree. Many women in such a situation prefer a career to a family and refuse a second child. To remedy the situation, the Chinese authorities passed several laws at once. For example, "On population and family planning", according to which the newlyweds are given a month's leave, the same amount is given to the husband to care for his wife and newborn, and maternity leave was 128-156 days

However, until today, a Chinese woman who has decided to give birth to a child is afraid of losing her job or losing her salary after leaving the decree. Many women in such a situation prefer a career to a family and refuse a second child. To remedy the situation, the Chinese authorities passed several laws at once. For example, "On population and family planning", according to which the newlyweds are given a month's leave, the same amount is given to the husband to care for his wife and newborn, and maternity leave was 128-156 days

Another law, "Employment Promotion" requires local people's governments to create conditions for fair competition in the labor market and the elimination of discrimination against certain categories of workers, guaranteeing the equal right to work for men and women. Employers do not have the right to refuse to hire women on the basis of gender or set higher requirements for women when hiring. An exception is certain types of work or positions for which women cannot be accepted in accordance with labor protection rules for the weaker sex.

In addition, employers may not include conditions in an employment contract that restrict the right of female workers to marry and have children.

At the same time, if a woman cannot be at the workplace due to pregnancy, the employer must resolve this issue according to her application, but not demote. If necessary, you can change her workplace, but you can not harm the health of a pregnant woman and an unborn child.

At the same time, the problem of generational conflict has become especially acute in modern China, and in the case of the Celestial Empire, it is not so much about "fathers and children" as about "daughters-in-law and mother-in-law," said Liu Shizen, a professor at the China Youth University of Political Science.

According to her, harmony in the family largely depends on the relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law. Misunderstanding between them brings discomfort to other family members, has a negative impact on the development of children, and even leads to divorce. And the global transformation of society, including changes in the political, economic, cultural and moral spheres, only adds fuel to the fire.

And the global transformation of society, including changes in the political, economic, cultural and moral spheres, only adds fuel to the fire.

According to statistics, 82 percent of Chinese families experience intergenerational conflicts due to different methods and views on raising children, and only two percent adhere to common views on this matter. When a child is not yet three years old, disagreements between mothers and grandmothers are not much different from ours: how to swaddle, how to put to sleep, what to feed and how to treat. The real fundamental disputes begin later.

For example, for the older generation, material wealth and health are the highest goals. Grandmothers believe that young children do not need education. And young parents are sure that the child needs to develop abilities. Mom wants the child to play more on the street, and grandparents, as soon as they see at least some kind of danger, immediately forbid him to play, often carry him along the street in his arms and do not let him run so that he does not suddenly fall.