How does socioeconomic status affect child development

Children, Youth, Families and Socioeconomic Status

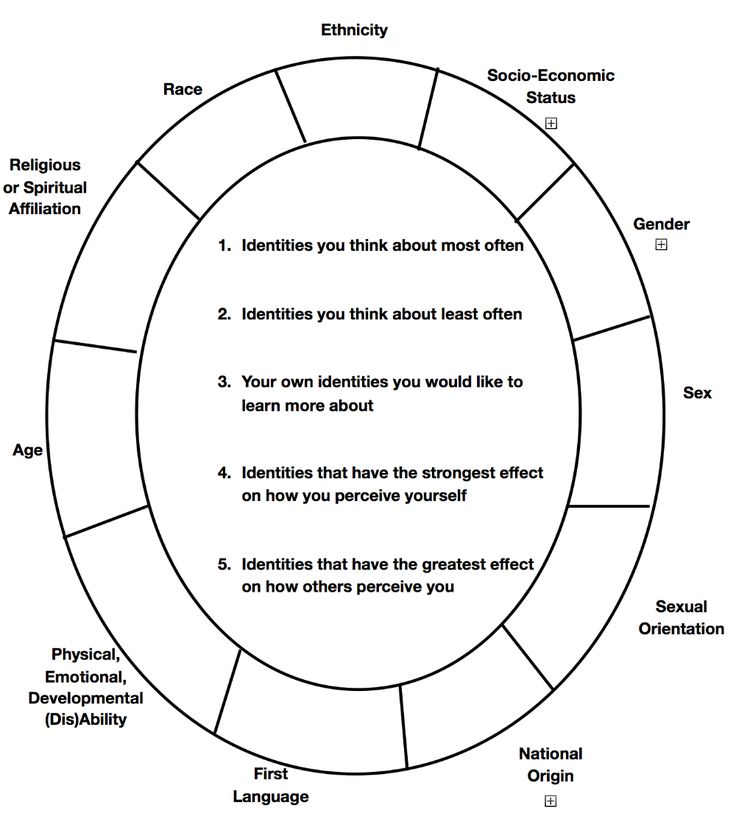

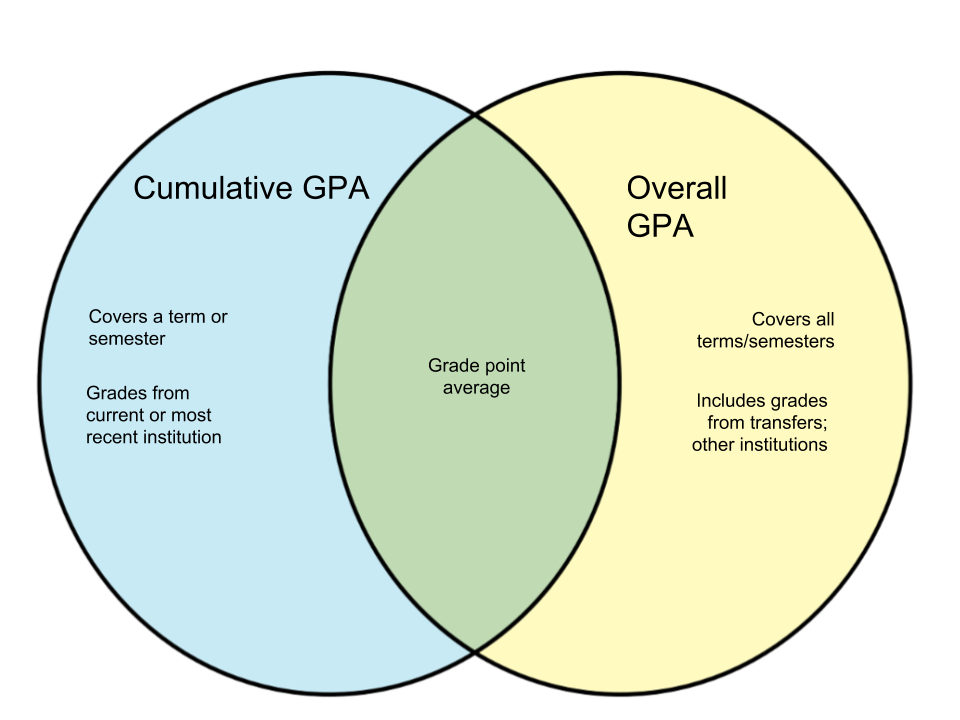

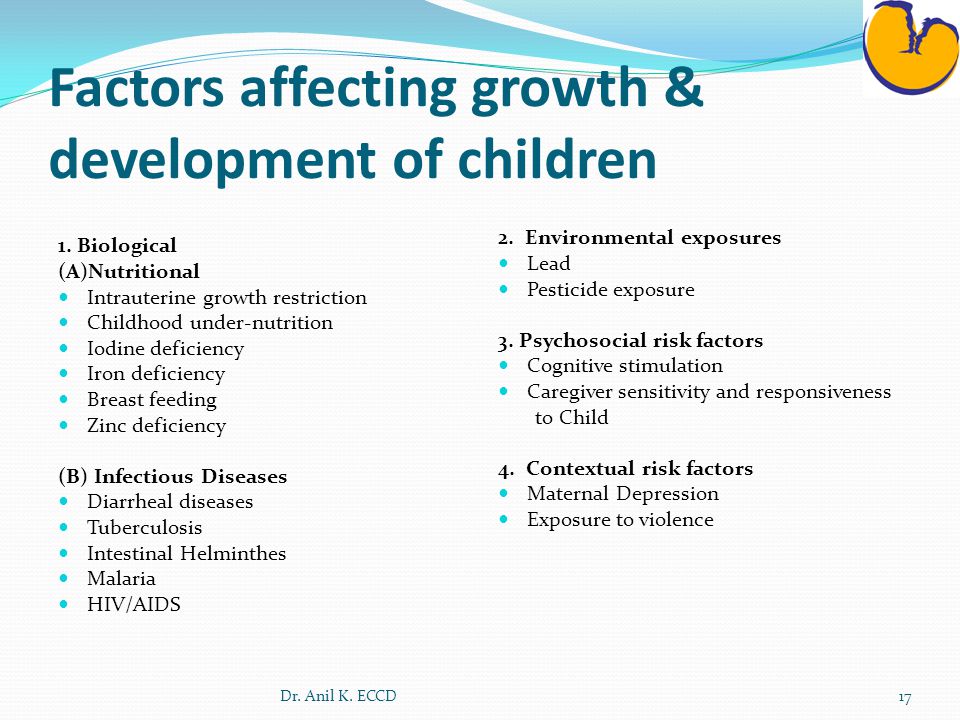

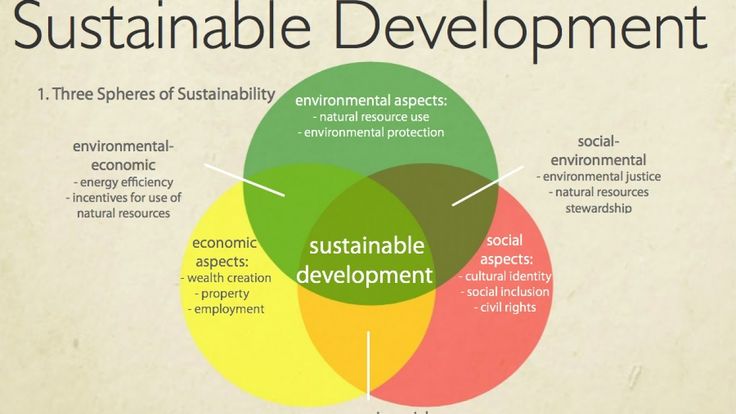

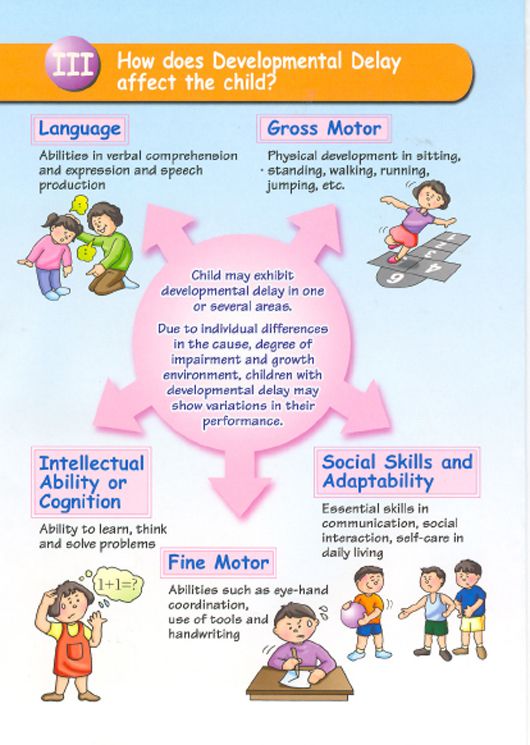

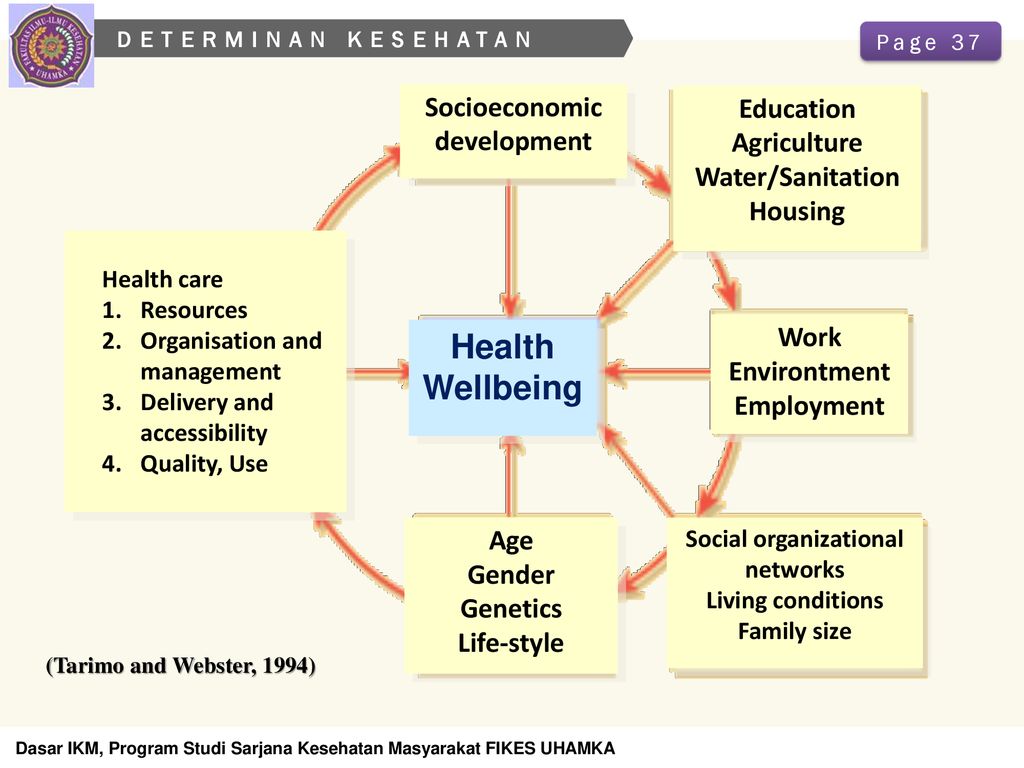

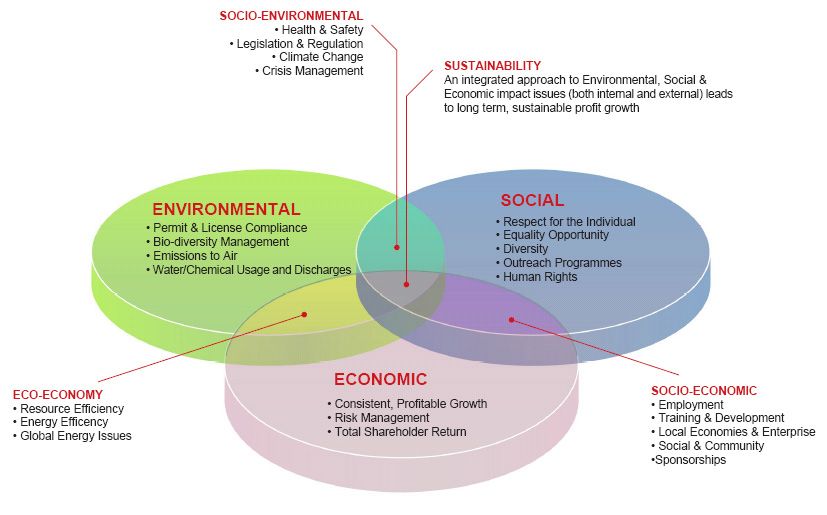

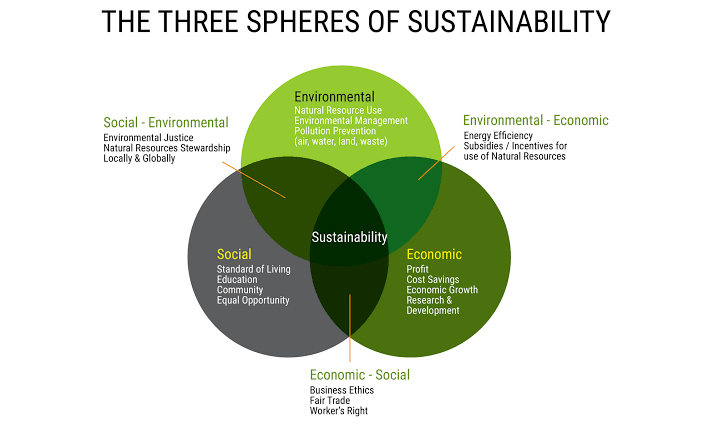

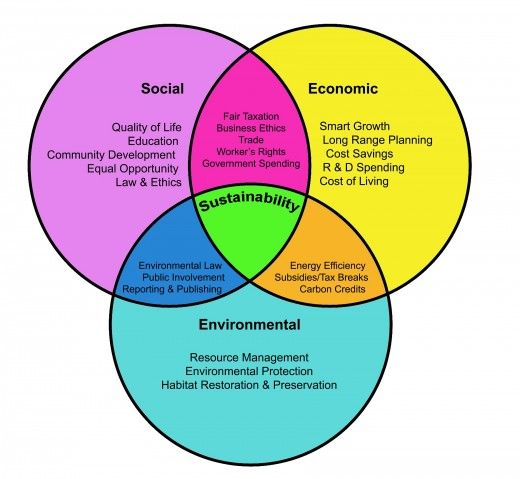

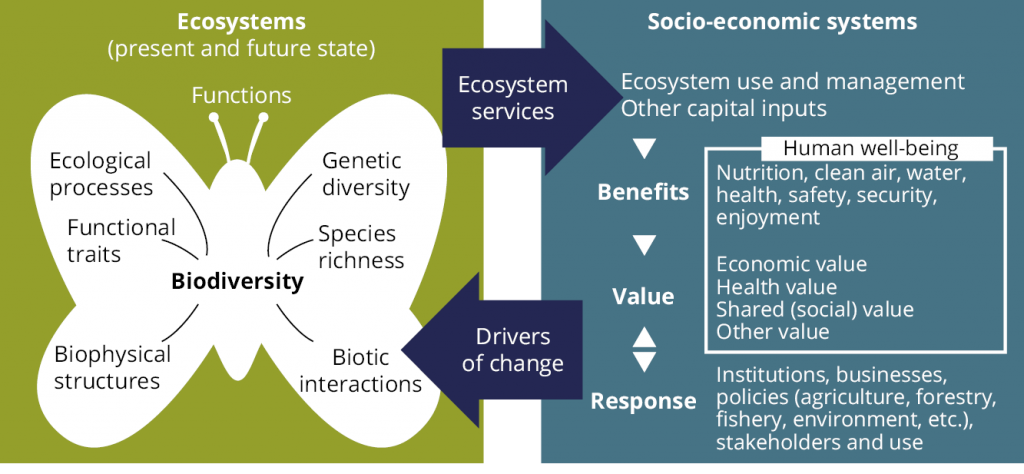

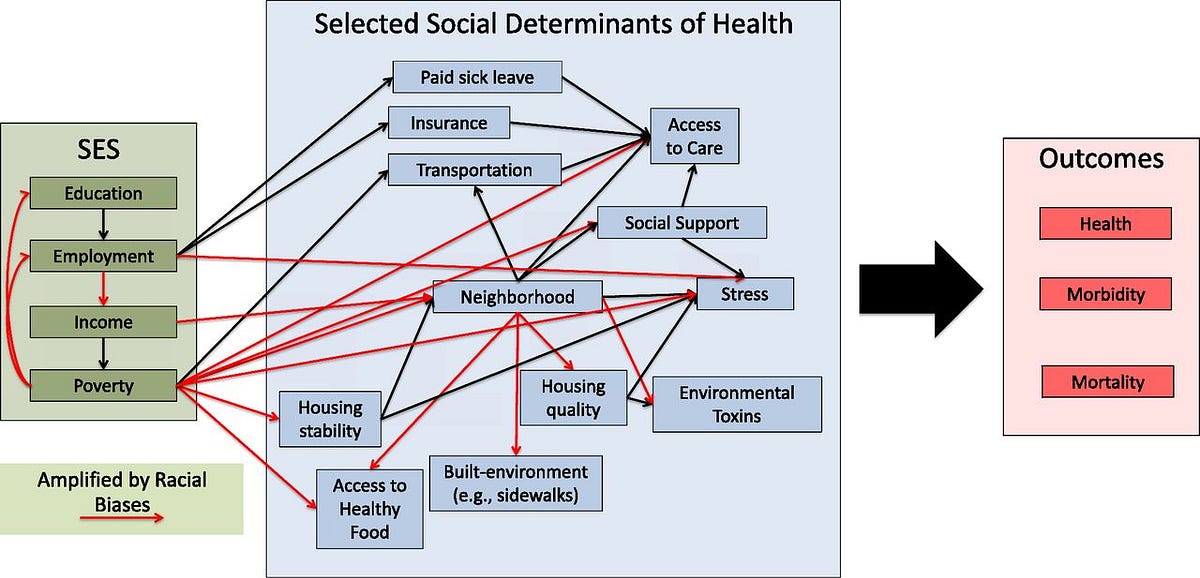

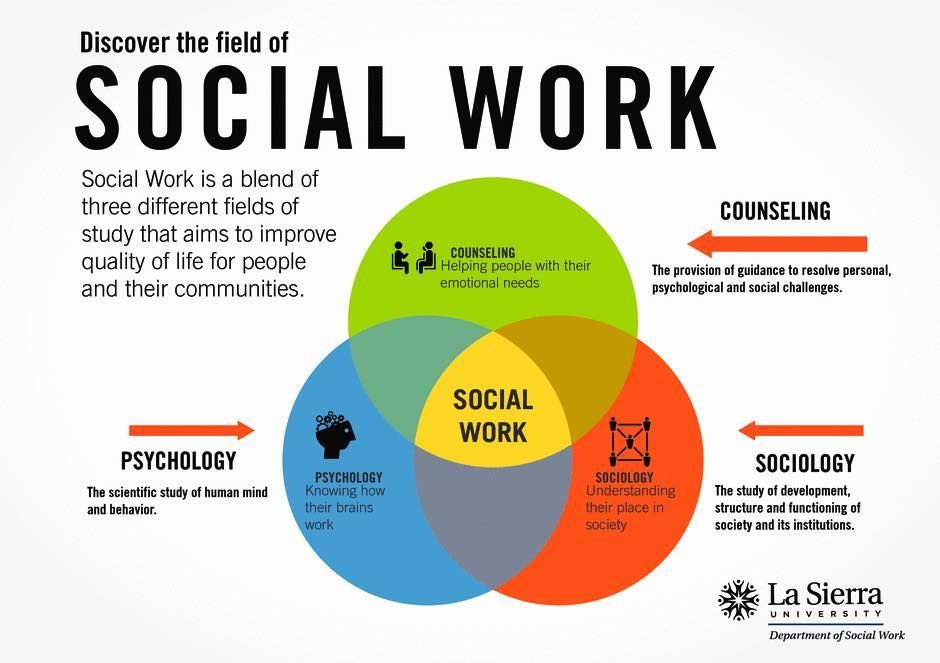

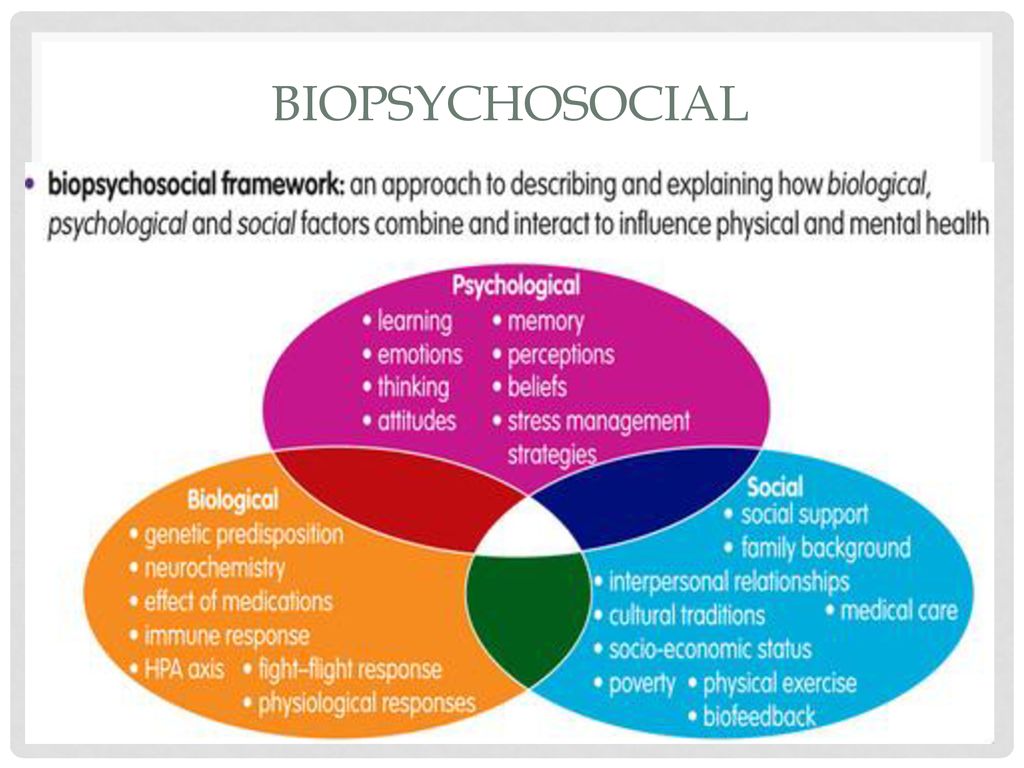

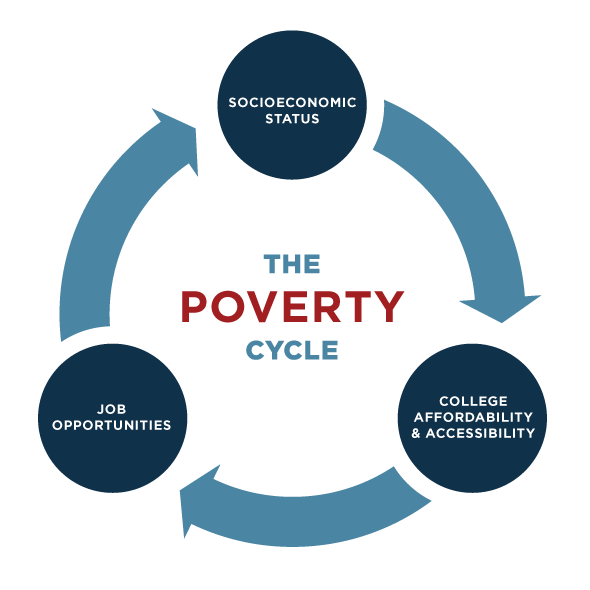

Socioeconomic status (SES) encompasses not just income but also educational attainment, occupational prestige, and subjective perceptions of social status and social class. Socioeconomic status can encompass quality of life attributes as well as the opportunities and privileges afforded to people within society. Poverty, specifically, is not a single factor but rather is characterized by multiple physical and psychosocial stressors. Further, SES is a consistent and reliable predictor of a vast array of outcomes across the life span, including physical and psychological health. Thus, SES is relevant to all realms of behavioral and social science, including research, practice, education and advocacy.

SES Affects Our Society

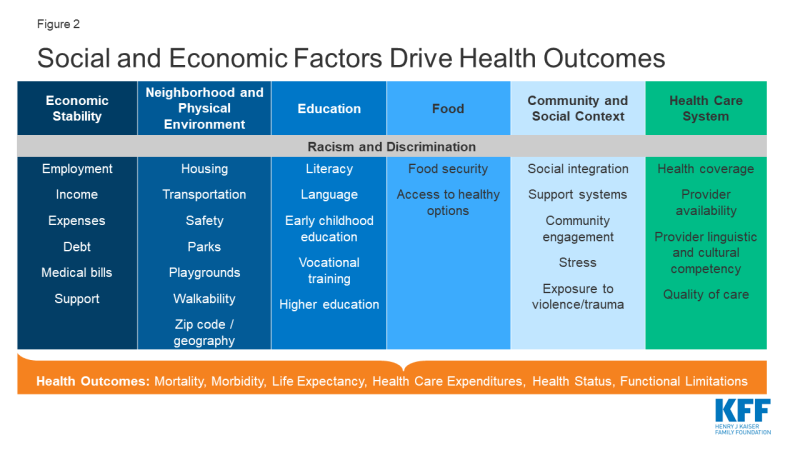

SES affects overall human functioning, including our physical and mental health. Low SES and its correlates, such as lower educational achievement, poverty and poor health, ultimately affect our society. Inequities in health distribution, resource distribution, and quality of life are increasing in the United States and globally. Society benefits from an increased focus on the foundations of socioeconomic inequities and efforts to reduce the deep gaps in socioeconomic status in the United States and abroad.

SES Impacts the Lives of Children, Youth and Families

Research indicates that SES is a key factor influencing quality of life, across the life span, for children, youth and families (CYF).

Psychological Health

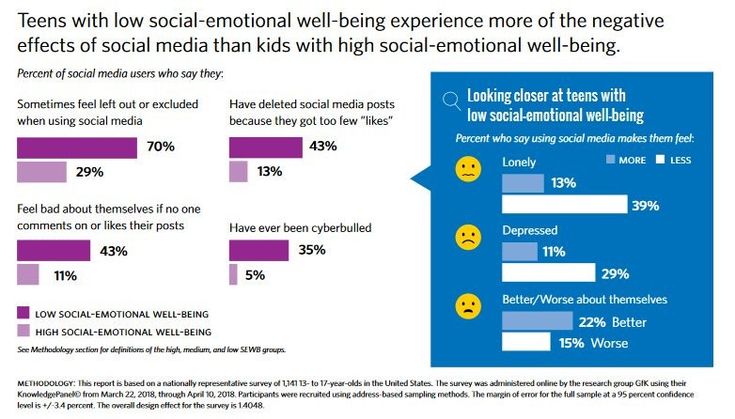

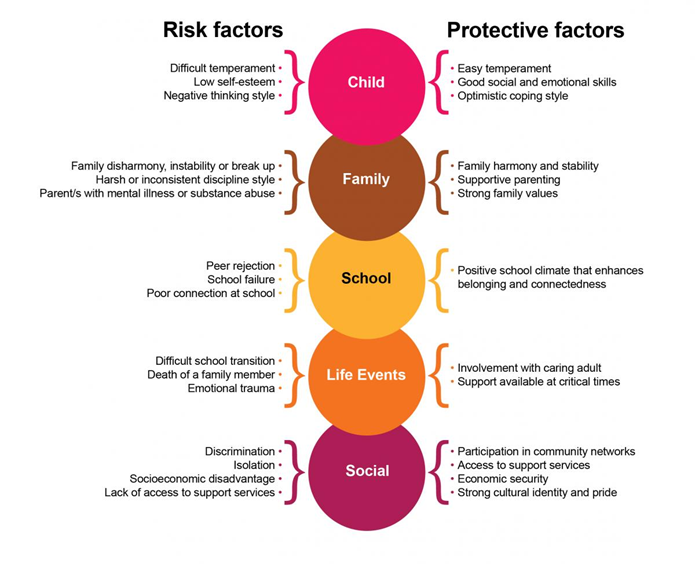

Increasing evidence supports the link between lower SES and negative psychological health outcomes, while more positive psychological outcomes such as optimism, self-esteem and perceived control have been linked to higher levels of SES for youth.

Lower levels of SES are associated with the following:

- Higher levels of emotional and behavioral difficulties, including social problems, delinquent behavior symptoms and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adolescents (DeCarlo Santiago, Wadsworth, & Stump, 2011; Russell, Ford, Williams, & Russell, 2016; Spencer, Kohn, & Woods, 2002).

- Higher rates of depression, anxiety, attempted suicide, cigarette dependence, illicit drug use and episodic heavy drinking among adolescents (Newacheck, Hung, Park, Brindis, & Irwin, 2003).

- Higher levels of aggression (Molnar, Cerda, Roberts, & Buka, 2008), hostility, perceived threat, and discrimination for youth (Chen & Paterson, 2006).

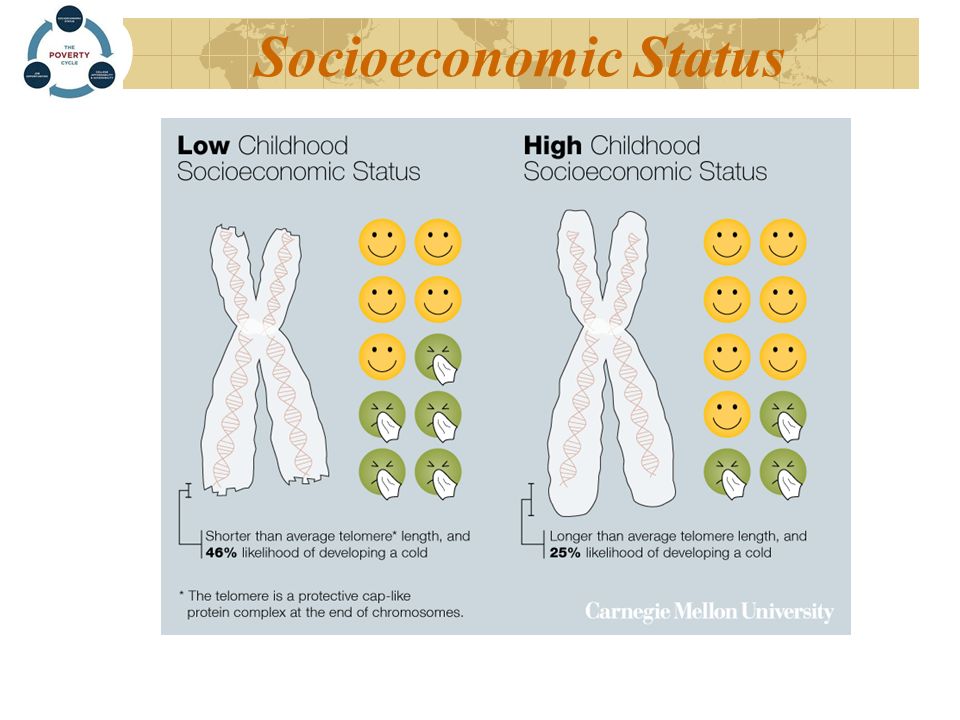

- Higher incidence of Alzheimer’s disease later in life (Evans et al., 1997; Fratiglioni & Roca, 2001; Fratiglioni, Winblad, & von Strauss, 2007; Karp et al., 2004). However, socioeconomic disparities in cell aging are evident in early life, long before the onset of age-related diseases (Needham, Fernández, Lin, Epel, & Blackburn, 2012).

- Elevated rates of morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases later in life (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011).

Physical Health

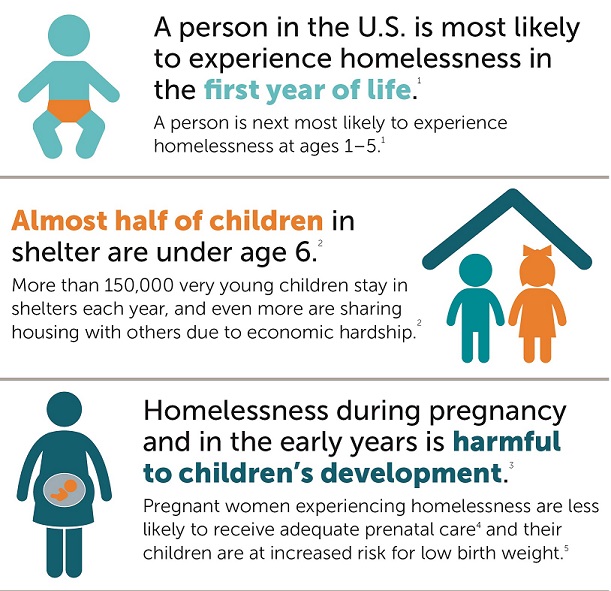

Research continues to link lower SES to a variety of negative health outcomes at birth and throughout the lifespan.

Lower levels of SES are associated with the following:

- Higher infant mortality. In the United States, babies born to White mothers have an expected mortality rate of 5.35 per 1,000 births. In comparison, babies born to black mothers had a mortality rate of 12.35 per 1,000 births (Haider, 2014).

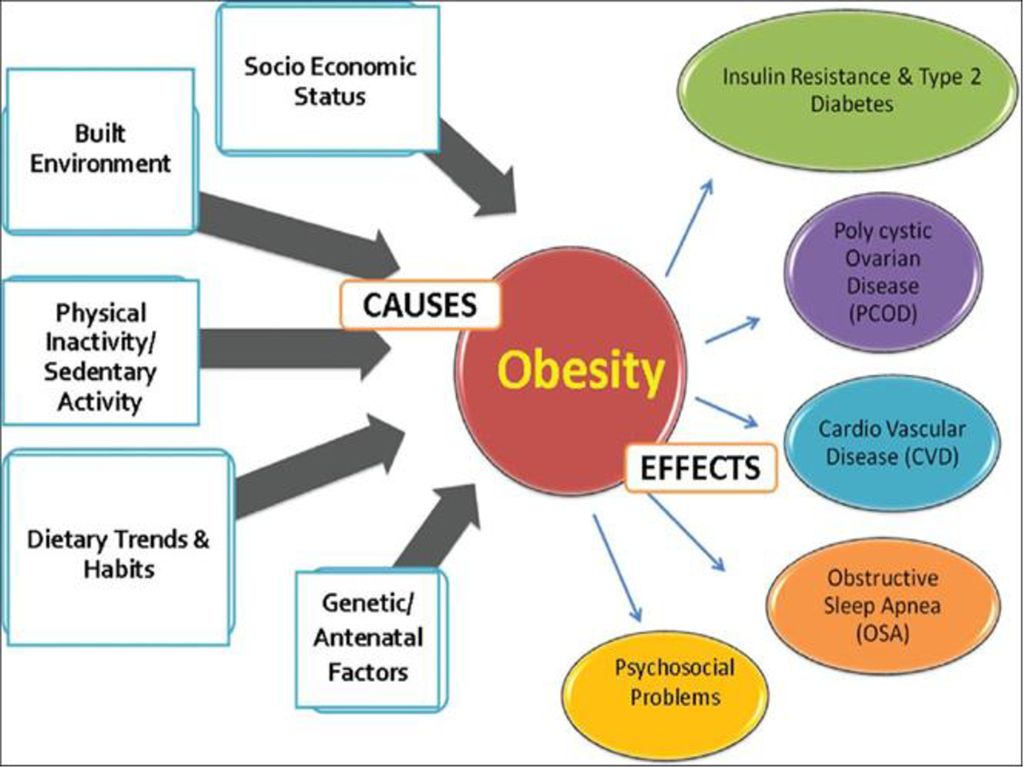

- Higher likelihood of being sedentary (Newacheck et al., 2003) and higher body mass index for adolescents (Chen & Paterson, 2006), possibly because of a lack of neighborhood resources—such as playgrounds and accessible healthy food options.

- Higher levels of obesity. U.S. counties with poverty rates of less than 35 percent had obesity rates 145 percent greater than wealthy counties (Levine, 2011).

- Higher physiological markers of chronic stressful experiences for adolescents (Chen & Paterson, 2006).

- Higher rates of cardiovascular disease for adults (Colhoun, Hemingway, & Poulter, 1998; Kaplan & Keil, 1993; Steptoe & Marmot, 2004).

Education

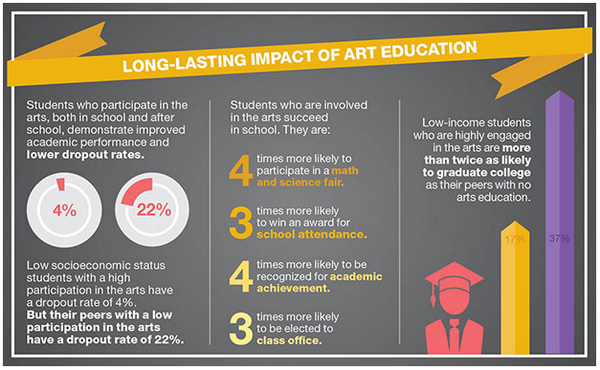

Increasing evidence supports the link between SES and educational outcomes.

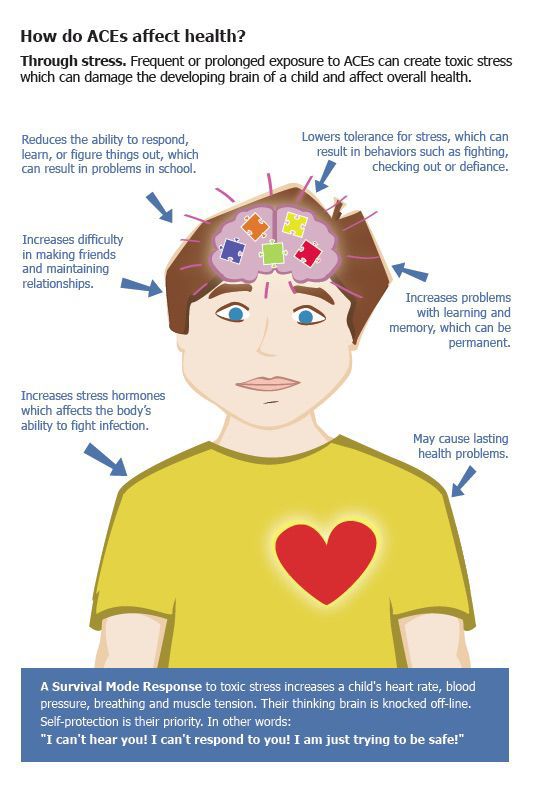

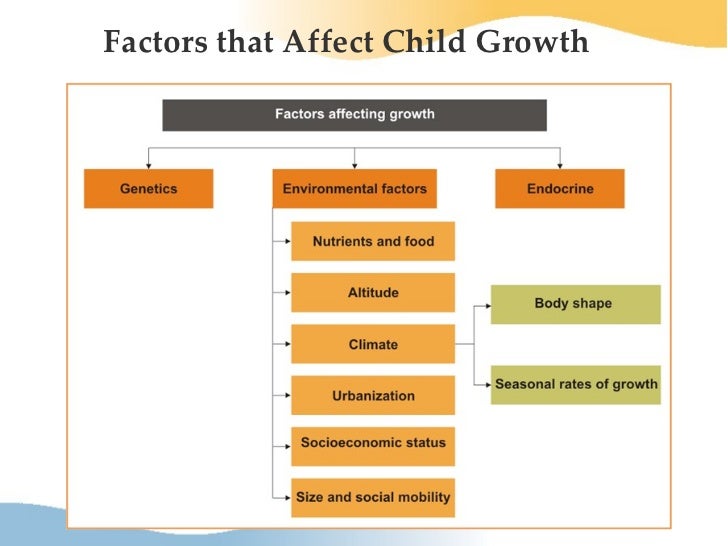

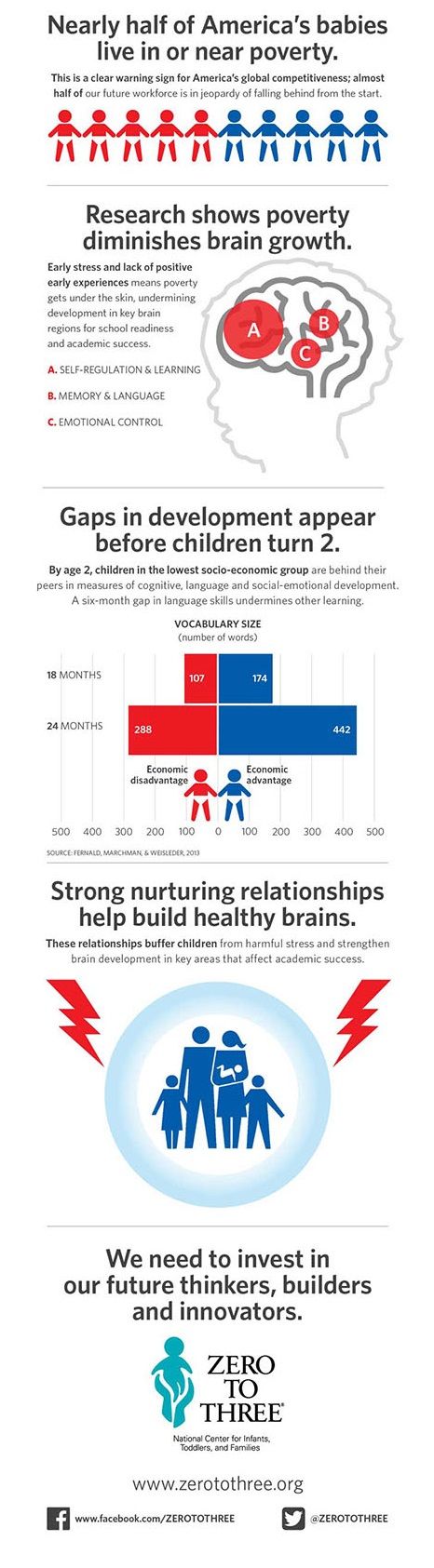

- Low SES and exposure to adversity are linked to decreased educational success (Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2016). Early experiences and environmental influences can have a lasting impact on learning (linguistic, cognitive and socioemotional skills), behavior and health (Shonkoff & Garner, 2012).

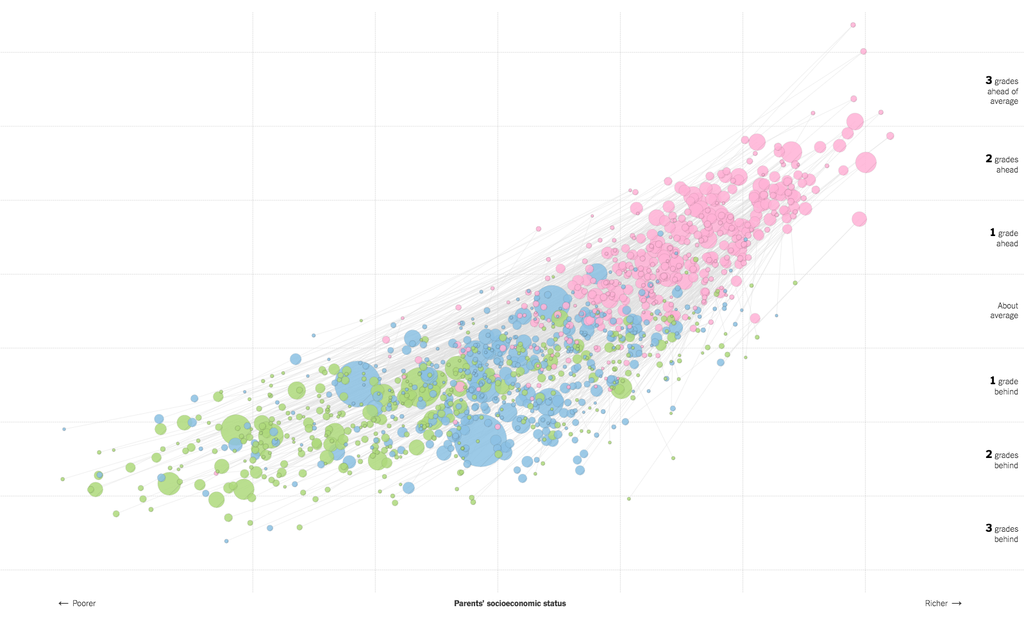

- Children from low-SES families often begin kindergarten with significantly less linguistic knowledge (Purcell-Gates, McIntyre, & Freppon, 1995). As such, children from low-income families enter high school with average literacy skills five years behind those of high-income students (Reardon, Valentino, & Shores, 2013).

- Children from less-advantaged homes score at least ten percent lower than the national average on national achievement scores in mathematics and reading (Hochschild, 2003).

- Children in impoverished settings are much more likely to be absent from school throughout their educational experiences (Zhang, 2003), further increasing the learning gap between them and their wealthier peers.

- While national high school dropout rates have steadily declined, dropout rates for children living in poverty have steadily increased. Low-income students fail to graduate at five times the rate of middle-income families and six times that of higher income youth (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016).

Family Well-Being

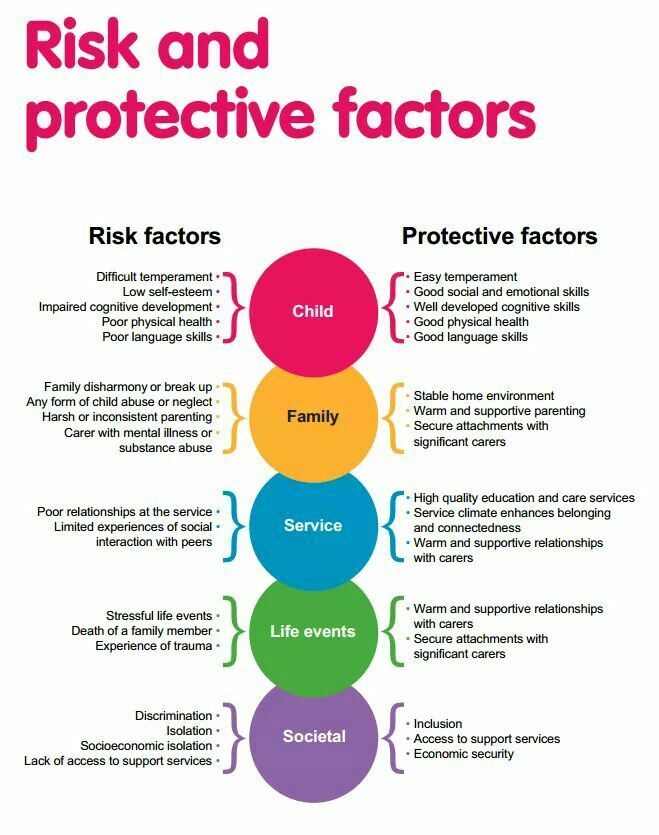

Evidence indicates that socioeconomic status affects family stability, including parenting practices and developmental outcomes for children (Trickett, Aber, Carlson, & Cicchetti, 1991).

- Resilience is optimized when protective factors are strengthened at all socioecological levels, including individual, family and community levels (Benzies & Mychasiuk, 2009).

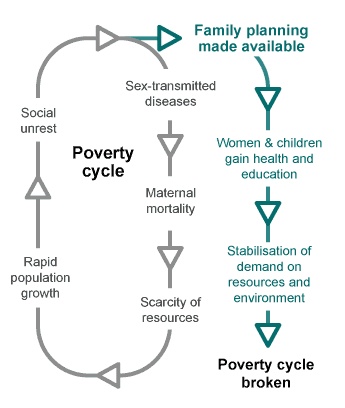

- Poverty is a reliable predictor of child abuse and neglect. Among low-income families, those with family exposure to substance use exhibit the highest rates of child abuse and neglect (Ondersma, 2002).

- Lower SES has been linked to domestic crowding, a condition that has negative consequences for adults and children, including higher psychological stress and poor health outcomes (Melki, Beydoun, Khogali, Tamim, & Yunis, 2004).

- Seven in 10 children living with a single mother are low income, compared to less than a third (32 percent) of children living in other types of family structures (Shriberg, 2013).

- All family members living in poverty are more likely to be victims of violence. Racial and ethnic minorities who are also of lower SES are at an increased risk of victimization (Pearlman, Zierler, Gjelsvik, & Verhoek-Oftedahl, 2004).

- Maintaining a strong parent–child bond helps promote healthy child development, particularly for children of low SES (Milteer, Ginsburg, & Mulligan, 2012).

Get Involved

- Support parents and caregivers in combating environmental stressors by using the Resilience Booster: Parent Tip Tool.

- Join the ACT Raising Safe Kids Program that teaches positive parenting skills to parents and caregivers.

- Consider SES in your education, practice, and research efforts.

- Stay up to date on legislation and policies that explore and work to eliminate socioeconomic disparities.

Visit the Office on Government Relations website.

Visit the Office on Government Relations website. - Visit APA’s Office on Socioeconomic Status (OSES) website.

- Visit APA’s Office on CYF website.

References

Benzies, K., & Mychasiuk, R. (2009). Fostering family resiliency: A review of the key protective factors. Child and Family Social Work, 14, 103-114. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00586.x

Chen, E., & Paterson, L. Q. (2006). Neighborhood, family, and subjective socioeconomic status: How do they relate to adolescent health? Health Psychology, 25, 704-714. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.704

Colhoun, H. M., Hemingway, H., & Poulter, N. R. (1998). Socio-economic status and blood pressure: An overview analysis. Journal of Human Hypertension, 12, 91–110. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1000558

DeCarlo Santiago, C., Wadsworth, M. E., & Stump, J. (2011). Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32, 218-230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.008

Journal of Economic Psychology, 32, 218-230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.008

Evans, D. A., Hebert, L. E., Beckett, L. A., Scherr, P. A., Albert, M. S., Chown, M. J., & Taylor, J. O. (1997). Education and other measures of socioeconomic status and risk of incident Alzheimer disease in a defined population of older persons. Archives of Neurology, 54, 1399-1405. doi:10.1001/archneur.1997.00550230066019

Fratiglioni, L., & Rocca, W. A. (2001). Epidemiology of dementia. In F. Boller, & S. F. Cappa (Eds.), Handbook of neuropsychology (2nd ed., pp. 193-215). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier.

Fratiglioni, L., Winblad, B., & von Strauss, E. (2007). Prevention of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: Major findings from the Kungsholmen Project. Physiology & Behavior, 92, 98-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.059

Haider, S. J. (2014). Racial and ethnic infant mortality gaps and socioeconomic status. Focus, 31, 18-20. Retrieved from http://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/focus.htm

Focus, 31, 18-20. Retrieved from http://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/focus.htm

Hochschild, J. L. (2003). Social class in public schools. Journal of Social Issues, 59, 821-840.

Kaplan, G. A., & Keil, J. E. (1993). Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: A review of the literature. Circulation, 88, 1973-1998. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.88.4.1973

Karp, A., Kåreholt, I., Qiu, C., Bellander, T., Winblad, B., & Fratiglioni, L. (2004). Relation of education and occupation-based socioeconomic status to incident Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159, 175-183.

Levine, J. A. (2011). Poverty and obesity in the U.S. Diabetes, 60, 2667-2668. doi:10.2337/db11-1118

Melki, I. S., Beydoun, H. A., Khogali, M., Tamim, H., & Yunis, K. A. (2004). Household crowding index: A correlate of socioeconomic status and interpregnancy spacing in an urban setting. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 476-480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.012690

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.012690

Miller, G. E., Chen, E., & Parker, K. J. (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 959-997. doi:10.1037/a0024768.

Milteer, R. M., Ginsburg, K. R., & Mulligan, D. A. (2012). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bond: Focus on children in poverty. Pediatrics, 129(1), e204-e213. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2953

Molnar, B. E., Cerda, M., Roberts, A. L., & Buka, S. L. (2008). Effects of neighborhood resources on aggressive and delinquent behaviors among urban youths. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1086-1093. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.098913

National Center for Education Statistics. (2002). Education Longitudinal Study of 2002. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/els2002/bibliography. asp

asp

Needham, B. L., Fernández, J. R., Lin, J., Epel, E. S., & Blackburn, E. H. (2012). Socioeconomic status and cell aging in children. Social Science and Medicine, 74, 1948-1951. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.019

Newacheck, P. W., Hung, Y. Y., Park, M. J., Brindis, C. D., & Irwin, C. E. (2003). Disparities in adolescent health and health care: Does socioeconomic status matter? Health Services Research, 38, 1235-1252. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.00174

Ondersma, S. J. (2002). Predictors of neglect within low-SES families: The importance of substance abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72, 383-391. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.72.3.383

Pearlman, D. N., Zierler, S., Gjelsvik, A., & Verhoek-Oftedahl, W. (2004). Neighborhood environment, racial position, and risk of police-reported domestic violence: A contextual analysis. Public Health Reports, 118, 44-58. doi:10.1093/phr/118.1.44

Purcell-Gates, V., McIntyre, E., & Freppon, P. A. (1995). Learning written storybook language in school: A comparison of low-SES children in skills-based and whole language classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 32, 659-685. doi:10.3102/00028312032003659

A. (1995). Learning written storybook language in school: A comparison of low-SES children in skills-based and whole language classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 32, 659-685. doi:10.3102/00028312032003659

Reardon, S. F., Valentino, R. A., & Shores, K. A. (2013). Patterns of literacy among U.S. students. The Future of Children, 23(2), 17-37.

Russell, A. E., Ford, T., Williams, R., & Russell, G. (2016). The association between socioeconomic disadvantage and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A systematic review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47, 440-458. doi:10.1007/s10578-015-0578-3

Sheridan, M. A., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Neurological models of the impact of adversity on education. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 10, 108-113. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.05.013

Shonkoff, J. P. & Garner, A. S. (2012). The lifelong effects of childhood adversity and toxic stress. American Academy of Pediatrics, 129, e232-e246. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663

doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Shriberg, D. (2013). School psychology and social justice: Conceptual foundations and tools for practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Spencer, M. S., Kohn L. P., & Woods J. R. (2002). Labeling vs. early identification: The dilemma of mental health services under-utilization among low-income African American children. African American Perspectives, 8, 1–14.

Steptoe, A., & Marmot, M. (2004). Socioeconomic status and coronary heart disease: A psychobiological perspective. In L. J. Waite (Ed.), Aging, health and public policy: Demographic and economic perspectives (pp. 133-152. New York, NY: Population Council.

Trickett, P. K., Aber, J. L., Carlson, V., & Cicchetti, D. (1991). Relationship of socioeconomic status to the etiology and developmental sequelae of physical child abuse. Developmental Psychology, 27, 148-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.148

Zhang, M. (2003). Links between school absenteeism and child poverty. Pastoral Care in Education, 21, 10-17. doi:10.1111/1468-0122.00249

Pastoral Care in Education, 21, 10-17. doi:10.1111/1468-0122.00249

Effect of socioeconomic status on behavioral problems from preschool to early elementary school – A Japanese longitudinal study

1. Currie J, Stabile M. Socioeconomic status and child health: why is the relationship stronger for older children? Am Econ Rev. 2003;93: 1813–1823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Velez CN, Johnson J, Cohen P. A longitudinal analysis of selected risk factors for childhood psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28: 861–864. doi: S0890-8567(09) 60209–4 doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. van Oort F, van der Ende J, Wadsworth M, Verhulst F, Achenbach T. Cross-national comparison of the link between socioeconomic status and emotional and behavioral problems in youths. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46: 167–172. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0191-5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Mendelson T, Kubzansky LD, Datta GD, Buka SL. Relation of female gender and low socioeconomic status to internalizing symptoms among adolescents: A case of double jeopardy? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66: 1284–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.033 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Relation of female gender and low socioeconomic status to internalizing symptoms among adolescents: A case of double jeopardy? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66: 1284–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.033 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Ensminger M., Fotherill K. A decade of measuring SES: what it tells us and where to go from here In: Bornstein M, Bradley R, editors. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

6. Ostberg V, Vågerö D. Socioeconomic differences in mortality among children. Do they persist into adulthood? Soc Sci Med. 1991;32: 403–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Power C, Hypponen E, Smith GD. Socioeconomic position in childhood and early adult life and risk of mortality. Am J Public Health. 2005;9: 1396–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58: 175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Adler NE, Snibbe AC. The role of psychosocial processes in explaining the gradient between socioeconomic status and health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12: 119–123. [Google Scholar]

10. McLoyd V, Shanahan M. Poverty, parenting, and children’s mental health. Am Sociol Rev. 1993;5: 351–366. [Google Scholar]

11. Looker ED. Accuracy of proxy reports of parental status characteristics. Sociol Educ. 1989;62: 257–276. [Google Scholar]

12. Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. 2011. Summary Report of Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions 2011. Available from www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hss/dl/report_gaikyo_2011.pdf. Cited 7 March 2018

13. OECD. Society at a Glance. 2016. Available from www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/8116131e.pdf. Cited 7 March 2018

14. OECD. Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries Paris: OECD Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

15. OECD. Doing Better for Children; 2009. Available from www.oecd.org/els/social/childwellbeing. Cited 7 March 2018

OECD. Doing Better for Children; 2009. Available from www.oecd.org/els/social/childwellbeing. Cited 7 March 2018

16. OECD. In It Together Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

17. Tachibanaki T. Confronting income inequality in Japan. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

18. Adler NE, Snibbe AC. The role of psychosocial processes in explaining the gradient between socioeconomic status and health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12: 119–123. [Google Scholar]

19. Elgar FJ, De Clercq B, Schnohr CW, Bird P, Pickett KE, Torsheim T, et al. Absolute and relative family affluence and psychosomatic symptoms in adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2013;91: 25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.030 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Reagan PB, Salsberry PJ, Olsen RJ. Does the measure of economic disadvantage matter? Exploring the effect of individual and relative deprivation on intrauterine growth restriction. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64: 2016–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.022 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.022 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Ensminger M, Fotherill K. A decade of measuring SES: what it tells us and where to go from here In: Bornstein M, Bradley R, editors. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

22. von Rueden U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Bisegger C, Ravens-Sieberer U. Socioeconomic determinants of health related quality of life in childhood and adolescence: results from a European study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60: 130–135. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039792 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Dearing E, McCartney K, Taylor BA. Change in family income-to-needs matters more for children with less. Child Dev. 2001;72: 1779–1793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Kohen DE, Brooks-Gunn J, Leventhal T, Hertzman C. Neighborhood income and physical and social disorder in Canada: associations with young children’s competencies. Child Dev. 2002;73: 1844–1860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Child Dev. 2002;73: 1844–1860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Tamis-LeMonda CS, Shannon JD, Cabrera NJ, Lamb ME. Fathers and mothers at play with their 2- and 3-year-olds: contributions to language and cognitive development. Child Dev. 2004;75: 1806–1820. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00818.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. OECD. Education at a Glance. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

27. OECD. Country note, Japan. Education at a Glance; 2016. Available from www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/9616041ec065.pdf. Cited 7 March 2018

28. Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Yeung WJ, Smith JR. How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? Am Sociol Rev. 1998;63: 406–423. [Google Scholar]

29. Guo G. The timing of the influences of cumulative poverty on children’s cognitive ability and achievement. Soc Forces. 1998;77: 257–288. [Google Scholar]

30. NICHD. Duration and developmental timing of poverty and children’s cognitive and social development from birth through third grade. Child Dev. 2005;76: 795–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00878.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Child Dev. 2005;76: 795–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00878.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Brunner E, Davey Smith G, Marmot M, Canner R, Beksinska M, O’Brien J. Childhood social circumstances and psychosocial and behavioural factors as determinants of plasma fibrinogen. Lancet. 1996;347: 1008–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Power C, Manor O. Explaining social class differences in psychosocial health among young adults: a longitudinal perspective. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27: 284–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Rahkonen O, Lahelma E, Huuhka M. Past or present? Childhood living conditions and current socioeconomic status as determinants of adult health. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44: 327–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Power C. Childhood adversity still matters for adult health outcomes. Lancet. 2002;360: 1610–1620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11555-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Korenman S, Miller JE, Sjaastad JE. Long-term poverty and child development in the United States: results from the NLSY. Child Youth Serv Rev. 1995;17: 127–155. [Google Scholar]

Child Youth Serv Rev. 1995;17: 127–155. [Google Scholar]

36. Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Dev. 1994;65: 296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20: 359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Rutter M, Sroufe LA. Developmental psychopathology: concepts and challenges. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12: 265–296. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400003023 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Zigler EF, Muenchow S. Head Start: The inside story of America’s most successful educational experiment New York: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

40. Currie J, Thomas D. Does head start make a difference. Am Econ Rev. 1995;85 doi: 10.3386/w4406 [Google Scholar]

41. Olds DL, Sadler L, Kitzman H. Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: Recent evidence from randomized trials. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48: 355–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01702.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48: 355–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01702.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behaviour Check-List/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

43. Itani T, Kanbayashi Y, Nakata Y, Kita M, Kuramoto H, Negishi T, et al. Standardization of the Japanese version of the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18. Psychiatr Neurol Pediatr Jpn. 2001;41: 243–252. [Google Scholar]

44. Kobayashi K, Endoh F, Ogino T, Oka M, Morooka T, Yoshinaga H, Ohtsuka Y. Questionnaire-based assessment of behavioral problems in Japanese children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27: 238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.01.020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Drotar D, Stein RE, Perrin EC. Methodological issues in using the child behavior checklist and its related instruments in clinical psychology research. J Clin Child Psychol. 1995;24: 184–192. [Google Scholar]

46. Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280: 1690–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280: 1690–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3: 21 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Petersen MR. A comparison of two methods for estimating prevalence ratios. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8: 9 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Population Census 2010. Statistics Bureau. Available from: http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kokusei/2010/summary.htm. Cited 09 February 2018

50. Becker G. A treatise on the family Boston: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

51. McLoyd V, Wilson L. Maternal behavior, social support, and economic conditions as predictors of distress in children. New Dir Child Dev. 1990;46: 49–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

New Dir Child Dev. 1990;46: 49–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch. BMJ. 2001;322: 1233–1236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Hart B, Risley T. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brooks; 1995. [Google Scholar]

54. Elder G, Conger K, Foster E, Ardelt M. Families under economic pressure. J Fam Issues. 1992;13: 5–37. [Google Scholar]

55. Meadows S, McLanahan S, Brooks-Gunn J. Parental depression and anxiety and early childhood behavior problems across family types. J Marriage Fam. 2007;69: 1162–1177. [Google Scholar]

56. Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Family poverty, welfare reform, and child development. Child Dev. 2000;71: 188–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early-childhood development. Child Dev. 1994;65: 296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1994;65: 296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Garrett P, Ng’andu N, Ferron J. Poverty experience of young children and the quality of their home environments. Child Dev. 1994;65: 331–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Magnuson KA, Votruba-Drzal E. Enduring influences of childhood poverty In: Cancian M, Danziger S, editors. Changing poverty, changing policies. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. pp. 153–179. [Google Scholar]

60. Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Family poverty, welfare reform, and child development. Child Dev. 2000;71: 188–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Yeung WJ, Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J. How money matters for young children’s development: parental investment and family processes. Child Dev. 2002;73: 1861–1879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Petterson S, Albers AB. Effects of poverty and maternal depression and early childhood development. Child Dev. 2001;72: 1794–1813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Dev. 1992;63: 526–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Dev. 1992;63: 526–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviours and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull. 2002;128: 539–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. 1990;61: 311–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. Am Psychol. 2004;59: 77–92. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch. BMJ. 2001;322: 1233–1236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder G. Family economic hardship and adolescent academic performance: Mediating and moderating processes In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 288–310. [Google Scholar]

Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 288–310. [Google Scholar]

69. Runciman WG. Relative deprivation and social justice London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1966. [Google Scholar]

70. Deater-Deckard K, Chen N, Wang Z, Bell MA. Socioeconomic risk moderates the link between household chaos and maternal executive function. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26: 391–399. doi: 10.1037/a0028331 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Wilkinson R. Health inequalities: relative or absolute material standards? BMJ. 1997;314: 591–595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Eibner C, Evans W. Relative deprivation, poor health habits deprivation, poor health habits, and mortality. J Hum Resour. 2005;40: 591–620. [Google Scholar]

73. Huisman M, Araya R, Lawlor DA, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Oldehinkel AJ. Cognitive ability, parental socioeconomic position and internalising and externalising problems in adolescence: findings from two European cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(8): 569–580. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9473-1 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(8): 569–580. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9473-1 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Miech RA, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wright BRE, Silva PA. Low socioeconomic status and mental disorders: a longitudinal study of selection and causation during young adulthood. Am J Sociol. 1999;104: 1096–1131. [Google Scholar]

75. Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Maternal age and educational and psychosocial outcomes in early adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;43: 479–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Frias-Armenta M., McCloskey LA. Determinants of harsh parenting in Mexico. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26: 129–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Jackson S, Thompson RA, Christiansen EH, Colman RA, Wyatt J, Buckendahl CW, et al. Predicting abuse-prone parental attitudes and discipline practices in a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23: 15–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Kelley ML, Power TG, Wimbush DD. Determinants of disciplinary practices in low-income black mothers. Child Dev. 1992;63: 573–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Child Dev. 1992;63: 573–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Dietz TL. Disciplining children: Characteristics associated with the use of corporal punishment. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24: 1529–1542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. Does neighborhood and family poverty affect mothers’ parenting, mental health, and social support? J Marriage Fam. 1994;56: 441–455. [Google Scholar]

81. Davis-Kean PE. The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: the indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19: 294 doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.294 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Rhee SH, Waldman ID. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychol Bull. 2002;128: 490–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.490 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Bouchard TJ. Genetic influence on human psychological traits: a survey. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2004;13: 148–151. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00295.x [Google Scholar]

2004;13: 148–151. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00295.x [Google Scholar]

84. DiLalla LF, Gottesman II. Biological and genetic contributors to violence—Widom’s untold tale. Psychol Bull. 1991;109: 125–129. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.1.125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M. Strategy for investigating interactions between measured genes and measured environments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62: 473–481. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17: 271–301. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Pluess M, Belsky J. Differential susceptibility to parenting and quality child care. Dev Psychol. 2010;46: 379–390. doi: 10.1037/a0015203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Plomin R, Crabbe J. Dna. Psychol Bull. 2000;126: 806–828. doi: 10. 1037/0033-2909.126.6.806 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1037/0033-2909.126.6.806 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Miller GE, Chen E, Fok AK, Walker H, Lim A, Nicholls EF, et al. Low early-life social class leaves a biological residue manifested by decreased glucocorticoid and increased proinflammatory signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106: 14716–14721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902971106 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Umer M, Herceg Z. Deciphering the epigenetic code: an overview of DNA methylation analysis methods. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18: 1972–1986. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4923 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Levine S. Developmental determinants of sensitivity and resistance to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30: 939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Environmental programming of stress responses through DNA methylation: life at the interface between a dynamic environment and a fixed genome. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7: 103–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2005;7: 103–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Susman EJ. Psychobiology of persistent antisocial behavior: stress, early vulnerabilities and the attenuation hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30: 376–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.08.002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Meaney MJ. Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene × environment interactions. Child Dev. 2010; 81:41–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01381.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. van der Knaap LJ, Riese H, Hudziak JJ, Verbiest MM, Verhulst FC, Oldehinkel AJ, et al. Adverse life events and allele-specific methylation of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) in adolescents: the TRAILS study. Psychosom Med. 2015;77: 246–550. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Borghol N, Suderman M, McArdle W, Racine A, Hallett M, Pembrey M, et al. Associations with early-life socioeconomic position in adult DNA methylation. Int J Epidemiol. 2011; 41:62–74. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr147 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr147 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Tehranifar P, Wu H, Fan X, Flom JD, Ferris JS, Cho YH, et al. Early life socioeconomic factors and genomic DNA methylation in midlife. Epigenetics. 2013; 8: 23–27. doi: 10.4161/epi.22989 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Taylor SE, Way BM, Welch WT, Hillmert CJ, Lehman BJ, Eisenberger NI. Early family environment, current adversity, the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, and depressive symptomatology. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60: 671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Brummett BH, Boyle SH, Siegler IC, Kuhn CM, Ashley-Koch A, Jonassaint CR, et al. Effects of environmental stress and gender on associations among symptoms of depression and the serotonin transporter gene linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR). Behav Genet. 2008;38: 34–43. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9172-1 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Puig J, Englund MM, Simpson JA, Collins WA. Predicting adult physical illness from infant attachment: a prospective longitudinal study. Health Psychol. 2013;32: 409–417. doi: 10.1037/a0028889 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Predicting adult physical illness from infant attachment: a prospective longitudinal study. Health Psychol. 2013;32: 409–417. doi: 10.1037/a0028889 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Tsuya NO, Bumpass LL. Gender and housework In: Tsuya NO, Bumpas LL, editors. Marriage, work & family life in comparative perspective: Japan, South Korea & the United States. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press; 2004. pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar]

102. National Women’s Education Center of Japan (NWEC). International Comparative Research on ‘Home Education’ 2005: survey on children and the family life. Saitama: National Woman’s Education Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

103. Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31: 285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Najman JM, Hayatbakhsh MR, Clavarino A, Bor W, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM. Family poverty over the early life course and recurrent adolescent and young adult anxiety and depression: a longitudinal study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100: 1719–1723. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180943 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Family poverty over the early life course and recurrent adolescent and young adult anxiety and depression: a longitudinal study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100: 1719–1723. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180943 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Bennett J, Tayler CP. Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care. OECD; 2006. [Google Scholar]

106. Kearney MS, Levine PB. Income inequality, social mobility, and the decision to drop out of high school NBER Working Paper 20195. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Socio-economic status and development of executive function

Casey J. Hook, BA, Gwendolen M. Lawson, BA, Martha J. Farah, PhD

University of Pennsylvania, USA

(English). Translation: August 2015

Translation: August 2015

Introduction

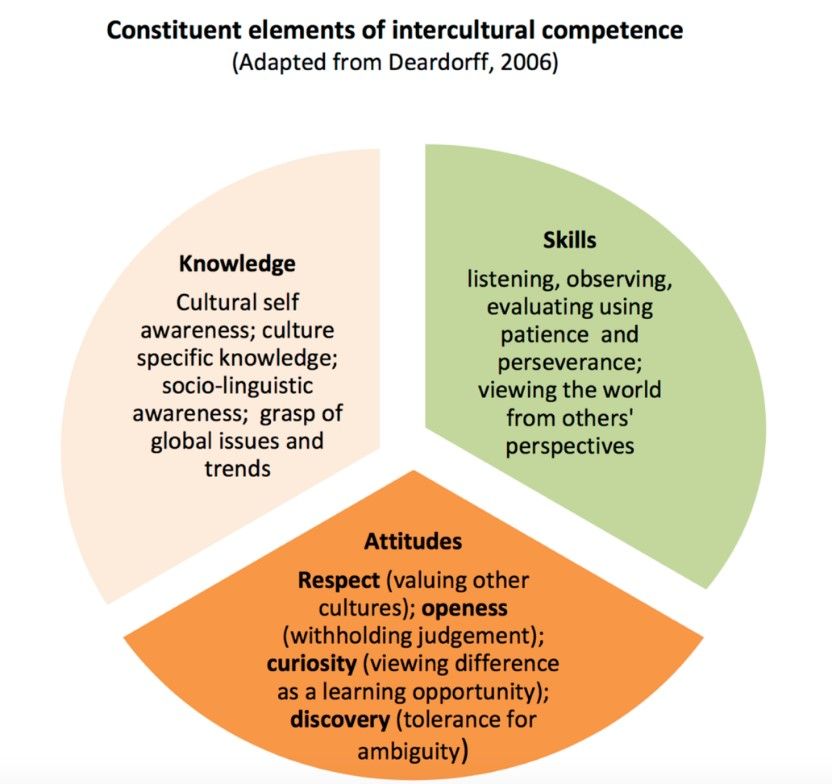

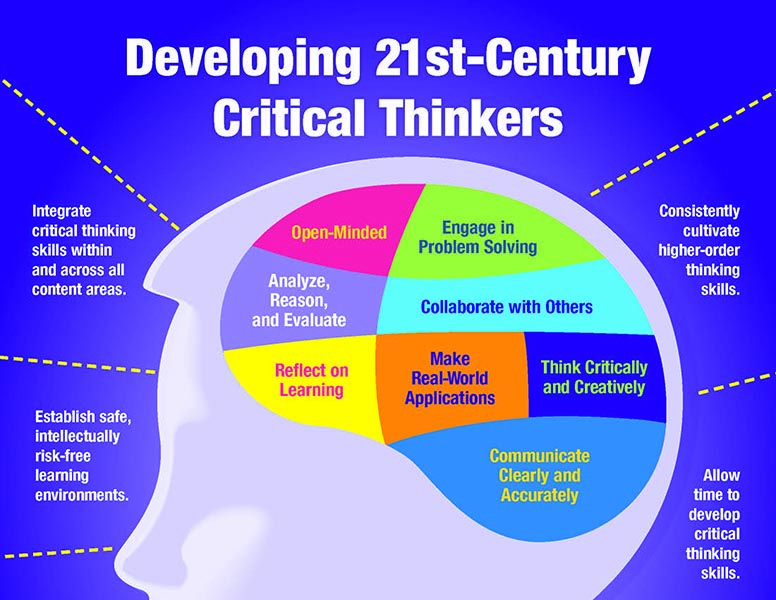

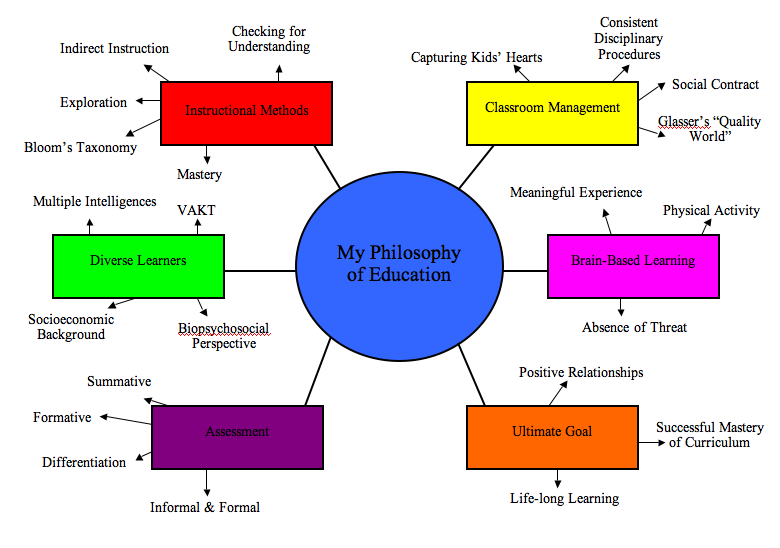

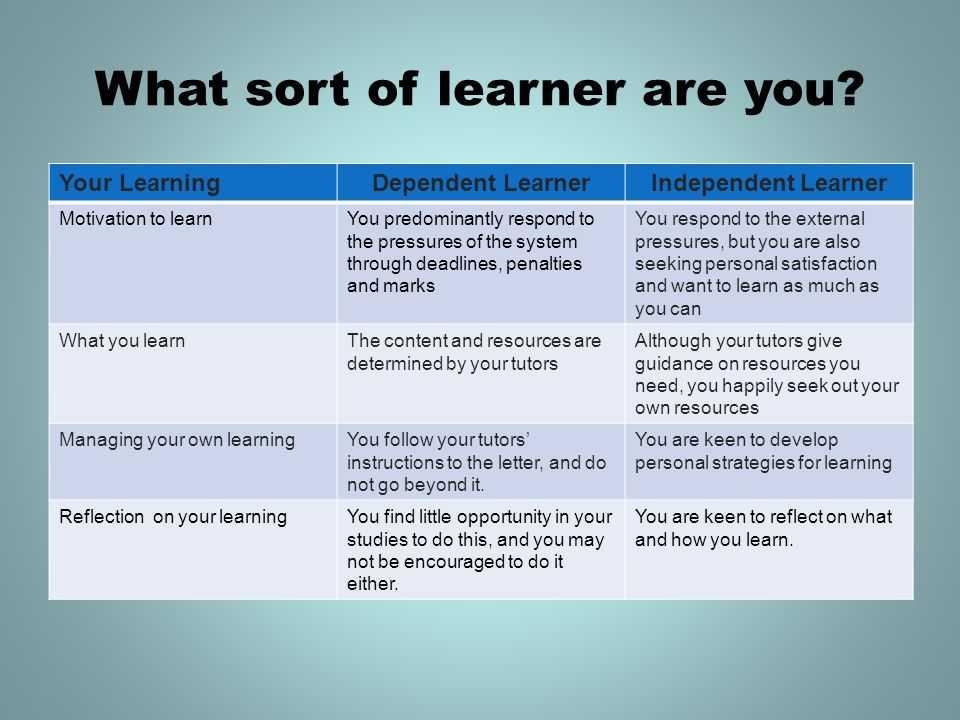

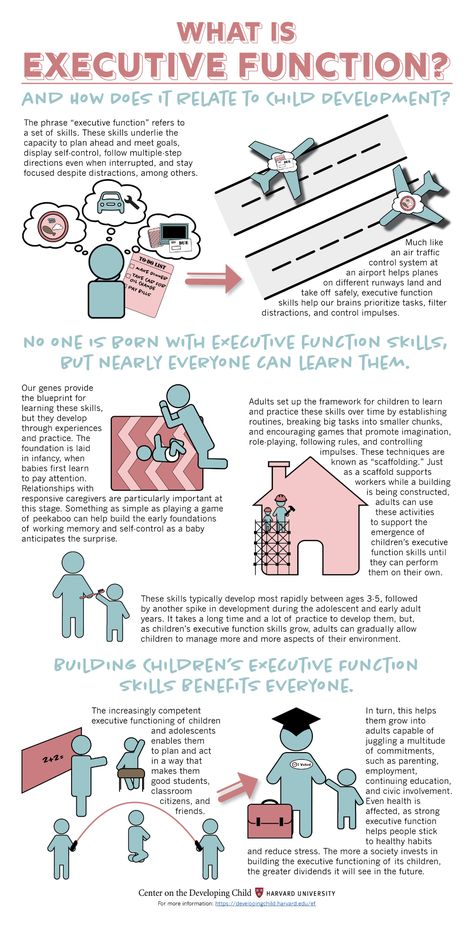

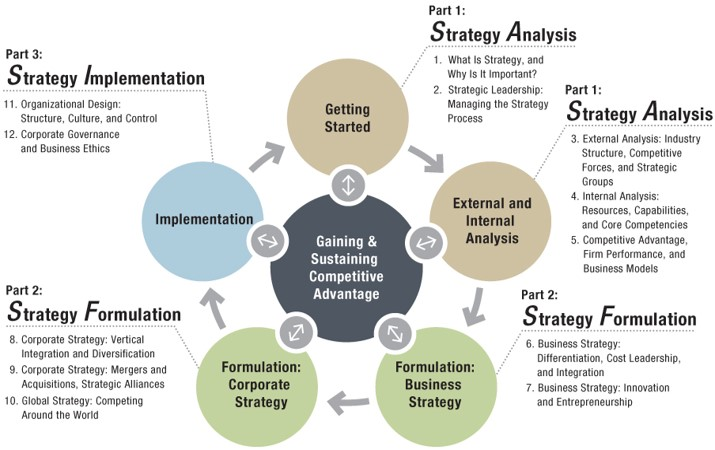

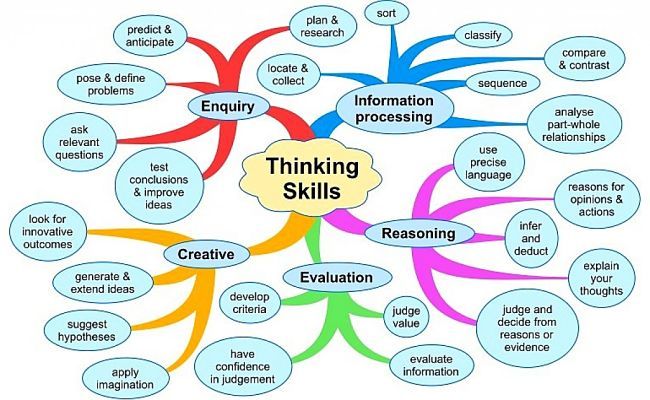

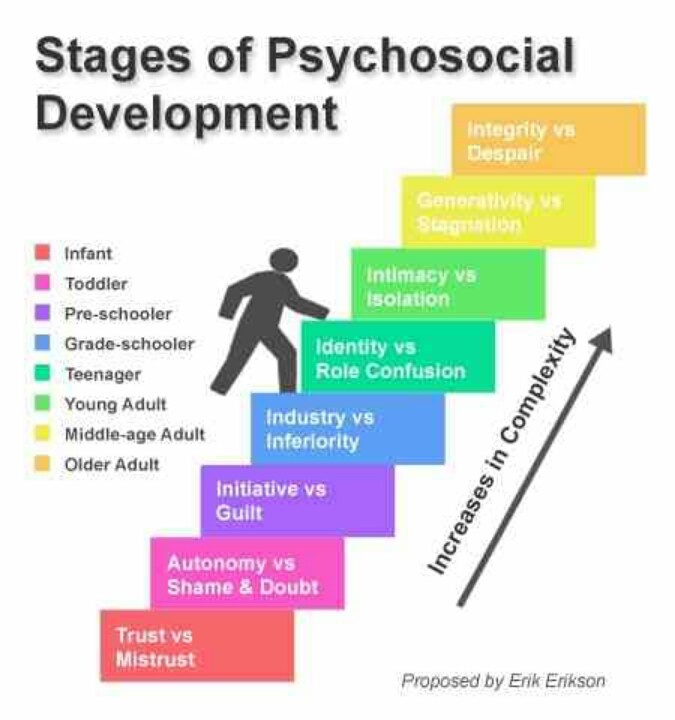

Emerging research indicates a relationship between childhood socioeconomic status and executive function development. Because socioeconomic status and executive function are highly and independently correlated with academic achievement and health status, understanding their relationship can be important for remedial interventions to reduce socioeconomic disparities and promote healthy development in all children.

Subject

Socioeconomic status, a measure of social standing that typically includes income, education, and occupation, is associated with a wide range of life outcomes ranging from cognitive ability and academic achievement to physical and mental health. 1-5 Understanding how childhood socioeconomic status affects life prospects is a matter of critical importance for education and public health, especially as global economic trends push more families into poverty. 6

6

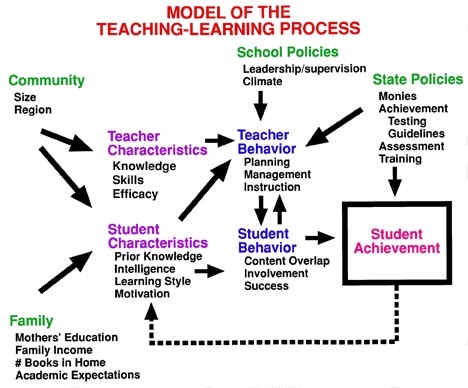

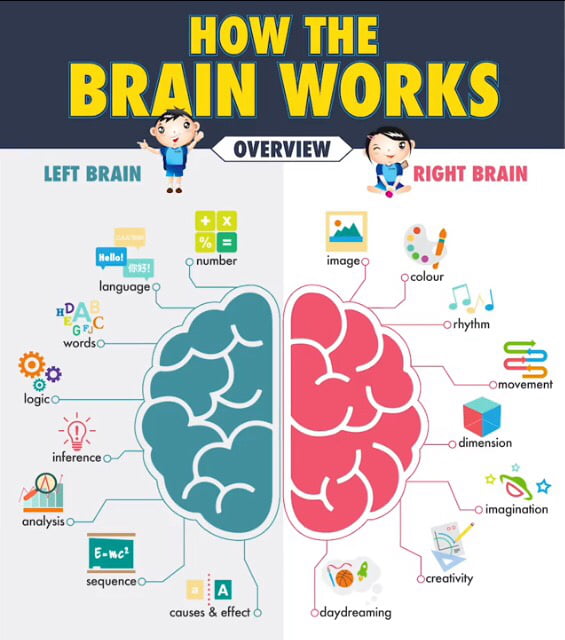

Current knowledge of socioeconomic status and child development indicates that children from families of high socioeconomic status demonstrate better executive function—the ability to actively direct, control, and regulate thoughts and behavior—compared to children from families with low socioeconomic status. Because the executive function has been shown to predict school achievement 7.8 and is associated with mental health outcomes, 9-13 then it can serve as one of the mediating links between socioeconomic status and academic performance, the relationship between which is reliably established.

Issues

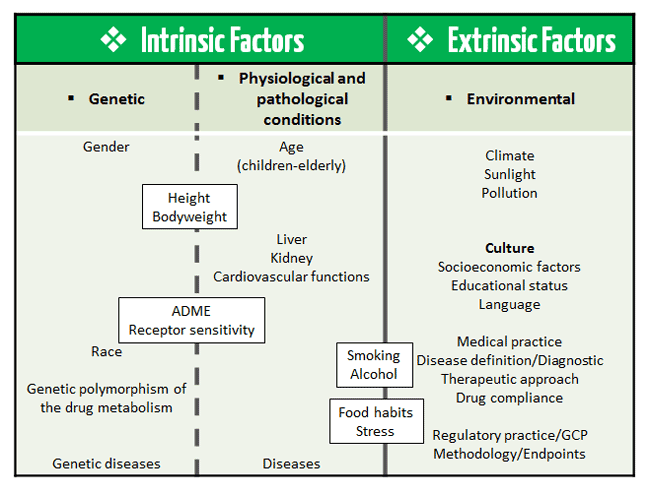

The study of this topic encounters certain methodological difficulties, which are partly a consequence of the broad and sometimes ambiguous origin of the terms "executive function" and "socio-economic status". "Executive function" refers to higher-order processes such as inhibitory control, working memory, and attentional flexibility that enable goal-directed behavior. Such a wide range of abilities can be operationalized using many different valid tests, such as computerized cognitive tasks or parental reports of children's behavior. 14 Similarly, "socioeconomic status" is a broad concept that can be measured in a variety of ways. 15 In addition, it cannot be manipulated experimentally, which makes it difficult to isolate genetic and environmental influences, as well as to assess the individual contribution of various circumstances associated with poverty (for example, increased family stress, poor cognitive stimulation, poor nutrition, crowding and poor environmental conditions). 16.17 Difficulties in establishing a causal relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function point to the need for large, well-designed studies requiring careful interpretation.

Such a wide range of abilities can be operationalized using many different valid tests, such as computerized cognitive tasks or parental reports of children's behavior. 14 Similarly, "socioeconomic status" is a broad concept that can be measured in a variety of ways. 15 In addition, it cannot be manipulated experimentally, which makes it difficult to isolate genetic and environmental influences, as well as to assess the individual contribution of various circumstances associated with poverty (for example, increased family stress, poor cognitive stimulation, poor nutrition, crowding and poor environmental conditions). 16.17 Difficulties in establishing a causal relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function point to the need for large, well-designed studies requiring careful interpretation.

Scientific context

Most studies of socioeconomic status and executive function have examined behavioral performance during age-appropriate executive function tasks, although a few recent studies 18-20 electrophysiological measurements of prefrontal cortical functions were used instead. Executive function development has been studied using both cross-sectional and large-scale longitudinal studies such as the Study of Early Childcare and the Family Life Project by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (the NICHD , National Institute of Child Health and Human Development). Many studies of mediating factors rely on data obtained during home visits, for example, using methods such as “HOME” (the HOME inventory) 21 , or from observing the interaction between a child and an adult during free or structured play. 22

Executive function development has been studied using both cross-sectional and large-scale longitudinal studies such as the Study of Early Childcare and the Family Life Project by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (the NICHD , National Institute of Child Health and Human Development). Many studies of mediating factors rely on data obtained during home visits, for example, using methods such as “HOME” (the HOME inventory) 21 , or from observing the interaction between a child and an adult during free or structured play. 22

Key questions

- What is the relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function development?

- What environmental factors mediate between socioeconomic status and executive function?

Latest research results

What is the relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function performance?

Research shows that socioeconomic status has an uneven effect on neurocognitive systems. In a recent series of studies, 23-25 preschoolers, first graders, and middle school students from families of diverse socioeconomic backgrounds completed a series of tasks that assessed independent cognitive systems that included executive function, memory, language, and visuospatial reasoning. Language abilities and executive function—particularly the areas of working memory and cognitive control—were among the most affected by socioeconomic status.

In a recent series of studies, 23-25 preschoolers, first graders, and middle school students from families of diverse socioeconomic backgrounds completed a series of tasks that assessed independent cognitive systems that included executive function, memory, language, and visuospatial reasoning. Language abilities and executive function—particularly the areas of working memory and cognitive control—were among the most affected by socioeconomic status.

Socioeconomic status inequalities in relation to executive function have been noted across a wide age range, from infancy 26 to older childhood. 27 Research has consistently found that higher socioeconomic status is associated with better executive function performance, regardless of the indicators of socioeconomic status used (such as family income-to-needs or mother's educational attainment) and regardless of how executive function is measured (such as working memory and inhibitory control). 28-32

28-32

Executive function is maintained by a region of the brain called the prefrontal cortex that undergoes long postnatal development, 33 so it may be particularly susceptible to the influences of childhood experiences. Socioeconomic differences in data processing in the neural networks of the prefrontal cortex have been studied using the method of evoked potentials (EP), where brain activity is measured using electrodes placed on the scalp. In two RJ studies 18.20 compared neural measures of selective attention across socioeconomic groups. In both cases, task performance was similar, but neural network processing scores suggest that children with low socioeconomic status paid more attention to irrelevant stimuli compared to their peers with high socioeconomic status.

What are the mediating factors between socioeconomic status and executive functions?

Many environmental factors such as stress, home cognitive stimulation, prenatal environment and nutrition have been shown to change in response to socioeconomic conditions. 16.17 Any of these factors can lead to social and economic inequality in the managerial function. Recent studies have attempted to isolate environmental factors that provide a link between socioeconomic status and executive function. These mediating factors can serve as material for interventions aimed at inequality of socioeconomic status in executive function and other cognitive and behavioral indicators.

16.17 Any of these factors can lead to social and economic inequality in the managerial function. Recent studies have attempted to isolate environmental factors that provide a link between socioeconomic status and executive function. These mediating factors can serve as material for interventions aimed at inequality of socioeconomic status in executive function and other cognitive and behavioral indicators.

Several studies have found evidence that various aspects of the family environment influence the early development of executive function. For example, the quality of the relationship between parent and child, especially during infancy, has been found to mediate socioeconomic status and executive function in children at 36 months of age. 22 In addition, infant stress levels (measured using salivary cortisol) partially explained the effect of positive parenting on executive function, suggesting that parenting may affect it by inducing stress responses in children. 28 Other research indicates that parental support for child independence, 34 gentle help and guidance, and levels of family chaos may be important predictors of executive function in early childhood. 35.36

28 Other research indicates that parental support for child independence, 34 gentle help and guidance, and levels of family chaos may be important predictors of executive function in early childhood. 35.36

Unexplored areas

- The trajectory of the inequality relationship and the control function over time is largely unknown. The influence of socioeconomic status may increase over time, for example if it is combined with other influences throughout development. On the other hand, it may remain unchanged or decrease, for example, if it is opposed by formal education.

- Research to date suggests that executive function development may be particularly sensitive to environmental influences during the early childhood and preschool years, but the exact timing and nature of this possible sensitive period remains to be explored.

- It is difficult to disentangle the role played by genetic and environmental factors in the development of executive function, and the causal nature of the relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function has not yet been fully established.

One way to establish causality in these relationships is to study the outcomes of remedial interventions that alter factors in the child's environment.

One way to establish causality in these relationships is to study the outcomes of remedial interventions that alter factors in the child's environment. - While differences in executive function are thought to be part of the explanation for disparities in achievement, the extent to which corrective interventions that improve executive function lead to improvements in other vital signs deserves further investigation.

Conclusions

Evidence indicates a clear relationship between childhood socioeconomic status and executive function performance. This relationship appears to be mediated by aspects of the family environment, such as the quality of parent-child relationships and their ability to buffer stress. Research in this area is at an early stage, and research currently under way will contribute to understanding the nature of the relationship between executive socioeconomic status and environmental factors.

It is important to note that the existence of differences related to socioeconomic status and executive and brain function does not in any way mean that these differences are innate or unchangeable. The brain is a highly plastic organ; in addition, many studies indicate that the neural correlates of cognition can be altered through exposure to environmental experience. 37 We hope that clarifying the impact of socioeconomic status on cognitive development will allow remedial interventions to target more specific cognitive processes and environmental factors, ultimately helping to reduce socioeconomic inequalities.

The brain is a highly plastic organ; in addition, many studies indicate that the neural correlates of cognition can be altered through exposure to environmental experience. 37 We hope that clarifying the impact of socioeconomic status on cognitive development will allow remedial interventions to target more specific cognitive processes and environmental factors, ultimately helping to reduce socioeconomic inequalities.

Recommendations

Social policies designed to reduce socioeconomic disparities have traditionally focused either on socioeconomic status per se or on the outcomes of a wide range of achievements. The research presented in this article reveals additional targets: factors that mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function (eg, family environment) and executive function itself.

Many emerging studies 38 indicate that corrective interventions can improve executive function in children. Successful interventions include learning software, games, yoga and meditation, participation in sports activities, and specialized training programs; children from low-income families are among those showing the greatest progress.

Successful interventions include learning software, games, yoga and meditation, participation in sports activities, and specialized training programs; children from low-income families are among those showing the greatest progress.

How can administrative policies and services address the root causes of the gap between socioeconomic status and managerial function? Because the home environment has a lasting impact on development, policy decisions regarding children's environments in a broader sense – rather than those focused solely on school and preschool – can be helpful. In particular, research on mediating mechanisms points to the need to create programs and activities that reduce parental stress and increase children's access to cognitively stimulating activities and resources. 39

Literature

- Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, & Syme SL. Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient.

American Psychologist . 1994;49(1):15-24.

American Psychologist . 1994;49(1):15-24. - Gottfried AW, Gottfried AE, Bathurst K, Guerin DW, & Parramore MM. In: Bornstein, MH, Bradley RH, eds. Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. Monographs in Parenting Series . Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003; 189-207.

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics . 2010; 125(1):75-81.

- Shanahan L, Copeland W, Costello EJ, & Angold A. Specificity of putative psychosocial risk factors for psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry . 2008;49(1):34-42.

- Sirin SR. Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: a meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research . 2005;75(3):417-453.

- Fritzell J, Ritakallio V. Societal shifts and changed patterns of poverty.

International Journal of Social Welfare . 2010;19:S25-S41.

International Journal of Social Welfare . 2010;19:S25-S41. - Blair C, Diamond A. Biological processes in prevention and intervention: the promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Development and Psychopathology . 2008; 20:899-911.

- Evans GW, Rosenbaum J. Self-regulation and the income-achievement gap. Early Child Research Quarterly . 2008; 23(4):504-514.

- Barch D. The cognitive neuroscience of schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology . 2005; 1:321-353.

- Bush G, Valera EM, & Seidman LJ. Functional neuroimaging of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A review and suggested future directions. Biological Psychiatry . 2005; 57:1273-128.

- Morgan AB, Lilienfeld SO. A meta-analytic review of the relation between antisocial behavior and neuropsychological measures of executive function. Clinical Psychology Review . 2000; 20(1):113–136.

- Rogers RD, Kasai K, Koji M, Fukuda R, Iwanami A, Nakagome K., et al. Executive and prefrontal dysfunction in unipolar depression: a review of neuropsychological and imaging evidence. Neuroscience Research . 2004; 50(1):1-11.

- Williams JM, Watts, FM, Macleod C, & Mathews A. Cognitive Psychology and Emotional Disorders (2 nd ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1997.

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager T. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology . 2000; 41(1):49-100.

- Hauser R.M. Measuring socioeconomic status in studies of child development. child development. 1994; 65:1541-1545.

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology . 2002; 53(1):371-399.

- Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty.

American Psychologist . 2004; 59(2):77-92.

American Psychologist . 2004; 59(2):77-92. - D’AngiulliA, Weinberg J, Grunau R, Hertzman C, and Grebenkov P. Towards a cognitive science of social inequality: Children’s attention-related ERPs and salivary cortisol vary with their socioeconomic status. Proceedings of the 30th Cognitive Science Society Annual Meeting. 211-216

- Kishiyama, MM, Boyce WT, Jimenez AM, Perry LM, Knight RT. Socioeconomic disparities affect prefrontal function in children. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience . 2008; 21(6):1106-1115.

- Stevens C, Lauinger B, Neville H. Differences in the neural mechanisms of selective attention in children from different socioeconomic backgrounds: an event-related brain potential study. Developmental Science . 2009; 12(4):634-646.

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF, McAdoo HP, Coll CG. The home environments of children in the United States. Part 1: variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Development .

2001; 72(6):1868-1886.

2001; 72(6):1868-1886. - Rhoades BL, Greenberg MT, Lanza ST, Blair C. Demographic and familial predictors of early executive function development: contribution of a person-centered perspective. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology . 2011; 108(3): 638-662.

- Farah MJ, Shera DM, Savage JH, et al. Childhood poverty: Specific associations with neurocognitive development. Brain Research . 2006; 1110(1): 166-174.

- Noble KG, Norman MF, Farah MJ. Neurocognitive correlates of socioeconomic status in kindergarten children. Developmental Science . 2005; 8(1): 74-87.

- Noble KG, McCandliss BD, Farah MJ. Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Developmental Science . 2007; 10(4): 464-480.

- Lipina SJ, Martelli MI, Vuelta B, Colombo JA. Performance on the A-not-B task of Argentinian infants from unsatisfied and satisfied basic needs homes. International Journal of Psychology .

2005; 39:49-60.

2005; 39:49-60. - Sarsour K, Sheridan M, Jutte D, Nuru-Jeter A, Hinsh S, Boyce WT. Family socioeconomic status and child executive functions: The roles of language, home environment, and single parenthood. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2011; 17(1): 120-132.

- Blair C, Granger DA, Willoughby M et al. Salivary cortisol mediates effects of poverty and parenting on executive functions in early childhood. Child Development . 2011; 82(6): 1970-1984.

- Hughes C, Ensor R. Executive function and theory of mind in 2 year olds: a family affair? Developmental Neuropsychology . 2005; 28(2): 645-668.

- Lipina SJ, Martelli MI, Vuelta BL, Injoque-Ricle I, Colombo JA. Poverty and executive performance in preschool pupils from Buenos Aires city (Republica Argentina). Interdisciplinaria . 2004; 21(2): 153-193.

- Mezzacappa E. Alerting, orienting, and executive attention: Developmental properties and sociodemographic correlates in an epidemiological sample of young, urban children.

Child Development . 2004; 75(5): 1373-1386.

Child Development . 2004; 75(5): 1373-1386. - Wiebe SA, Sheffield T, Nelson JM, Clark CAC, Chevalier N, & Espy KA. The structure of executive function in 3-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology . 2011; 108(3): 436-452.

- Casey BJ, Giedd JN, Thomas KM. Structural and functional brain development and its relation to cognitive development. Biological Psychology . 2000; 54(1-3): 241-257.

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Whipple N. From external regulation to self-regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Development . 2010; 81(1): 326-339.

- Bibok MB, Carpendale JIM, Muller U. Parent scaffolding and the development of executive function. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development . 2009; 123:17-34.

- Hughes C, Ensor R. How do families help or hinder the emergence of early executive function? New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development .

2009; 123:35-50.

2009; 123:35-50. - Rosenzweig, MR. Effects of differential experience on the brain and behavior. Developmental Neuropsychology . 2003;24(2-3):523-540.

- Diamond A, Lee K. Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science . 2011;333(6045):959 -964.

- Hackman DA, Farah MJ, Meaney MJ. Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nature Reviews Neuroscience . 2010; 11:651-659.

For citation:

Hook KJ, Lawson GM, Farah MJ. Socio-economic status and development of the managerial function. In: Tremblay RE, Buavan M, Peters RDeV, eds. Morton DB, eds. Topics. Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.encyclopedia-deti.com/upravlyayushchie-funkcii/ot-ekspertov/socialno-ekonomicheskiy-status-i-razvitie-upravlyayushchey. Published: January 2013 (English). Viewed on December 2, 2022

Text copied to clipboard ✓

Socio-economic friendship — ECONS.

ONLINE

ONLINE Photo: Zuma | TASS

Economics

Macroeconomics

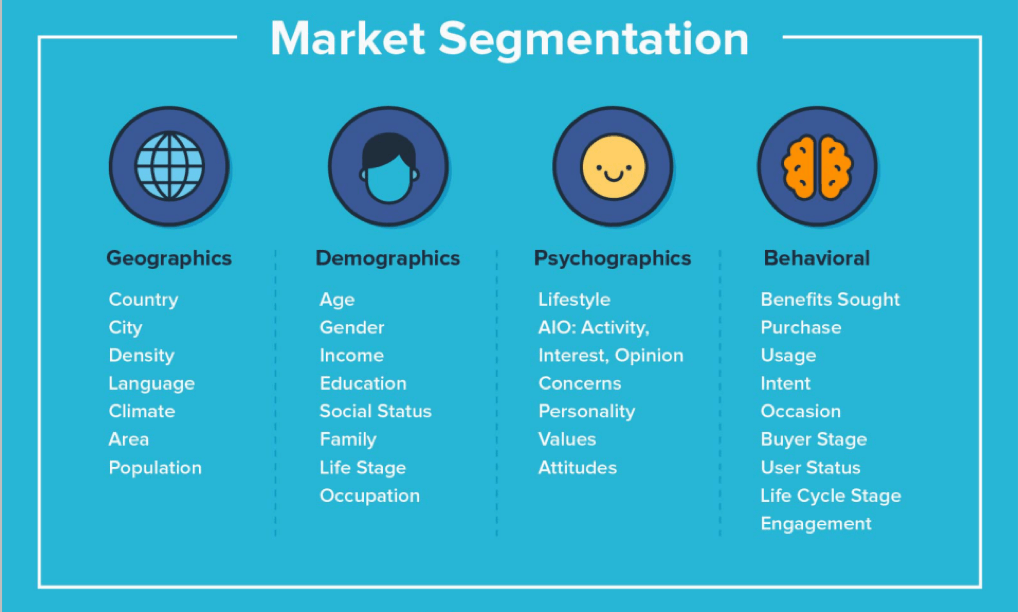

Many factors, from personal to institutional, influence how people move up the income ladder, but one seems to trump all others, a new large-scale study shows: it is friendship between people with different socioeconomic status .

August 22, 2022 | Olga Volkova Econs, Olga Kuvshinova Econs

Many factors, from personal to institutional, influence how people move up the income ladder, but one seems to trump all others, a new large-scale study has found: it is friendship between people of different socioeconomic status.

August 22, 2022 | Olga Volkova Econs, Olga Kuvshinova Econs

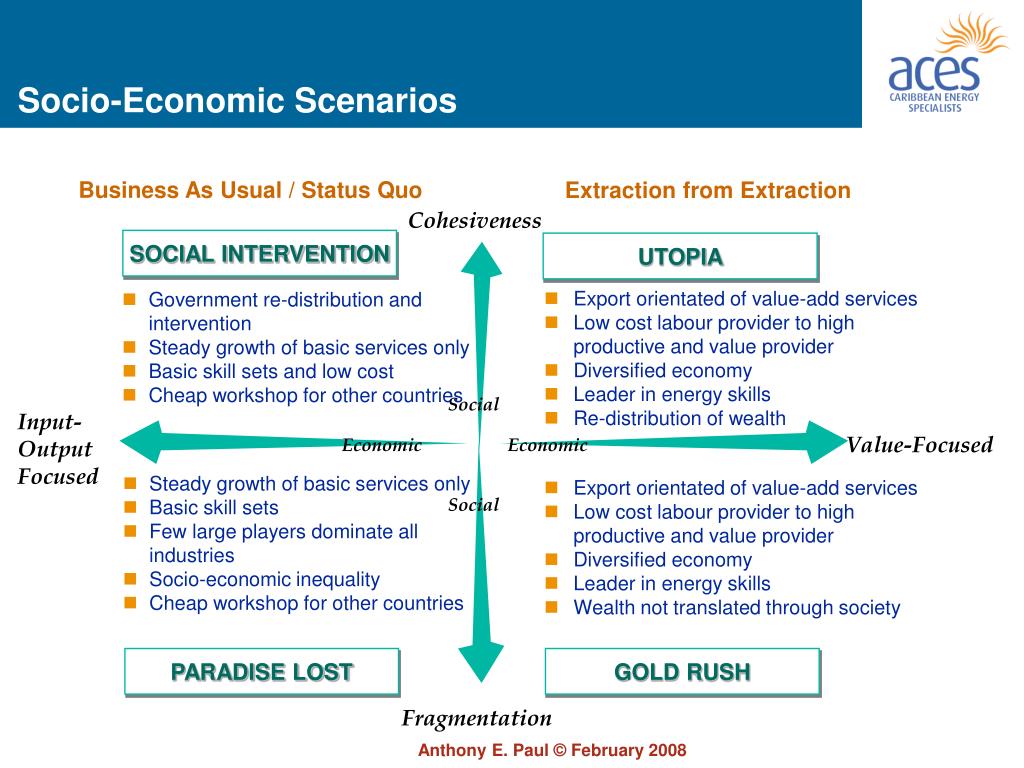

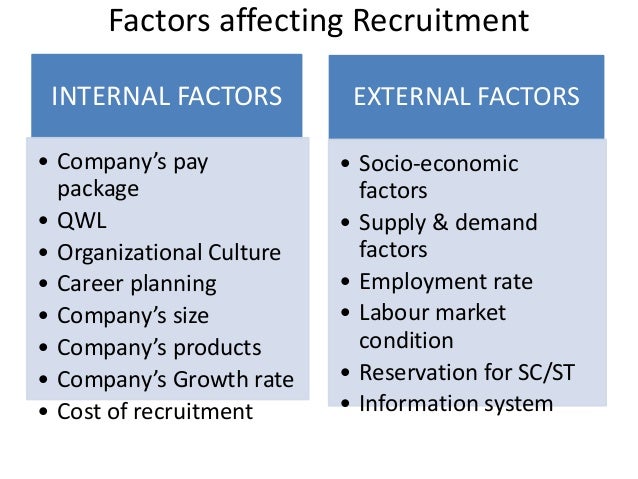

The ability of people to increase their socioeconomic status – or economic mobility, usually measured by higher income levels – depends on many conditions, from education policies and the labor market to the health care system and the housing market.:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19829235/at_risk_jobs_by_industry.jpg) Increasing economic mobility leads to accelerated economic growth and poverty reduction, therefore it is usually in the focus of economic policy. An important role in economic mobility is played by social capital - the quality of social ties between people, affecting economic development in general.

Increasing economic mobility leads to accelerated economic growth and poverty reduction, therefore it is usually in the focus of economic policy. An important role in economic mobility is played by social capital - the quality of social ties between people, affecting economic development in general.

But the most significant for economic mobility is not any social capital, but its quite specific subtype - economic connectedness, or how closely people with different socioeconomic status interact with each other. This conclusion was reached in a recent large-scale study published in two parts in the journal Nature ( First part, second part), a group of economists led by Raj Chetty, a professor at Harvard and winner of the John Bates Clark Medal, awarded to young scientists under the age of 40 and considered the second most important award for economists after the Nobel Prize.

Chetty and his co-authors analyzed data from more than 70 million social media users aged 25 to 44 living in the United States (and with at least 100 friends) - about 80% of the total population of the country in this age group. The number of considered pairs of friends exceeds 20 billion, and the detailing of the data allows for analysis at the micro level down to postal codes, that is, places of residence, and specific schools and universities graduated from users. Researchers rely on data on “online friendships” as a proxy for real-life friendships.

The number of considered pairs of friends exceeds 20 billion, and the detailing of the data allows for analysis at the micro level down to postal codes, that is, places of residence, and specific schools and universities graduated from users. Researchers rely on data on “online friendships” as a proxy for real-life friendships.

The study found that friendships between people from different socioeconomic groups influence economic mobility not only more strongly than other forms of social capital (such as cohesion based on the number of mutual friends and civic engagement), but also more strongly than such commonly recognized factors, as the level of education, the structure and status of the family, the level of inequality.

Economic connectedness, defined as the proportion of friends with high socioeconomic status among people with low socioeconomic status, is one of the strongest predictors of upward economic mobility (that is, chances to move up in income levels), the study authors conclude.

Economic mobility

Economic mobility is the ability of a person (or a family or social group) to increase their income level, namely, to move to a higher group in the income distribution (as a rule, in statistics, the entire population is divided into several equal groups with different income levels - usually per decile, or 10 groups). This movement up the income ladder, or moving from a lower decile to a higher decile, is called upward mobility. There is also a descending one - when people become poorer, shifting to lower rungs of the income ladder.

Economists distinguish between intergenerational and intragenerational mobility. Intergenerational is a comparison of the income of an adult with the income of his parents, that is, a comparison of the income of generations: the growth of intergenerational mobility means that grown children move into a higher income decile, that is, they have a higher socioeconomic status than their parents. Intragenerational mobility is the increase in a person's income group during his life.

Intragenerational mobility is the increase in a person's income group during his life.

Economic connectedness

The researchers calculated the socioeconomic status for each sample participant by combining several indicators (both the user's own data and external sources - for example, the average income of the area of \u200b\u200bits residence), calculating for each percentile rank in the national income distribution. Percentile rank is the distribution of the population into 100 equal groups, where the 1st percentile is the 1% of people with the lowest income, and the 100th percentile is the 1% of people with the highest income (the division into deciles by income is applied similarly, see . cut above).

The socioeconomic status of each user was compared by the researchers with the similar status of his friends. As expected, it turned out that to a greater extent "the poor are friends with the poor, the rich - with the rich." On average, less than 40% of people with below average status in the sample have friends with above average status, while more than 70% of people with above average status have friends with the same above average status. In addition, people with high status also have more friends - an average of 25%.

In addition, people with high status also have more friends - an average of 25%.

The relationship between different income deciles is weaker the farther these deciles are from each other. So, people from the top, 10th decile (the most affluent) have only 16% of friends from the bottom five deciles and more than a third from the 10th decile. People in the 1st decile (poorest) have three-quarters of their friends from the bottom five deciles, including almost a quarter from the same first decile they belong to.

The relationship between the status of own and friends is almost linear, the researchers found. An increase in a user's rank by one percentile is associated with an increase in the average rank of their friends by 0.44 percentile. Almost the same figure (0.46 percentile) is obtained if only the 10 closest friends are taken into account - that is, economic mobility is not affected by the strength of friendships and the number of friends, the authors conclude: only the overall “quality” of friendships is affected.

The "sources" of this environment also differ markedly between different income groups. The authors analyzed six such "sources" - places where people make friends: school, university, work, places of leisure, religious groups, place of residence (neighbourhood). It turned out that the poor are mostly friends with their neighbors, while the rich are friends with fellow students with whom they studied at universities (largely for the simple reason that the more affluent are more likely to go to university).

People with the lowest socioeconomic status have almost four times the proportion of neighbors among friends than people with the highest status; and people with a high socioeconomic status have the maximum share of friends acquired during their studies at a university.

Thus, neighborhoods play the most important role in the formation of social communities of people with low socioeconomic status - which explains why the neighborhood has a greater influence on economic results and health in low-income people than in high-income people.

Conditions for economic relations

The degree of economic interconnectedness depends on two factors:

- level of interaction between different socio-economic groups;

- friendship propensity (the speed with which friendly relations are formed between people with different socio-economic status).

Accordingly, the following can negatively affect economic connectedness: 1) low frequency or lack of contacts, primarily for people with a lower status - with people with a higher one, and 2) "bias in friendship", when even with the possibility of contacts, people still prefer make friends with people close to you. If we cite schools as an example, then in the first case, families with different statuses may prefer different schools for their children (explicit segregation), in the second case, children from families with different statuses may study in the same schools, but prefer to be friends with "like themselves" (implicit segregation).

The distinction between these two channels is of fundamental importance for designing policies to increase economic connectivity – and many policymakers worry that societies around the world are becoming more fragmented and polarized, the researchers note. If the main influence on economic connectivity is the lack of interaction, then measures are needed to increase integration between districts and educational institutions. And if "bias in friendship" - then the strengthening of integration within the districts and educational institutions.

The analysis of Chetty and his team showed that the lack of interaction factor “works” in almost all six “sources” of making friends described above (neighborhood, place of work, etc.), with the exception of universities: in other words, for people with low income the mere opportunity to enter into friendly contact with people with high income is significant only in places of higher education.

The “friendship bias” factor, in turn, is itself correlated with the level of economic connectedness of individual communities. For example, given an equal share of wealthy people in a low-income person's area of residence and in the religious group they attend, they are 20% more likely to make a higher-status friend in the religious group than in their neighborhood.

For example, given an equal share of wealthy people in a low-income person's area of residence and in the religious group they attend, they are 20% more likely to make a higher-status friend in the religious group than in their neighborhood.

Geography of friendship

Chetty and his team found some geographic patterns by comparing levels of interaction and "friendship bias" in boroughs US (postcode distribution): Thus, the states of the Midwest turned out to be much friendlier than the northeast of the country. At the same time, in the northeast, people with different socioeconomic status, although they are friends with each other less often, are better integrated (interact more often) at the level of schools and districts of residence.

By examining the relationship between upward economic mobility and economic connectivity at the geographic level of the United States (see box above), the researchers confirmed that connectivity affects mobility more than the level of income in a given region by itself. In other words, a person of low socioeconomic status living in a region that is relatively wealthier but with relatively less contact between socioeconomic classes is less likely to move into a higher income group than a person of the same low status living in a region less wealthy, but with a higher economic connectivity of different social groups.

In other words, a person of low socioeconomic status living in a region that is relatively wealthier but with relatively less contact between socioeconomic classes is less likely to move into a higher income group than a person of the same low status living in a region less wealthy, but with a higher economic connectivity of different social groups.

An increase in the proportion of wealthier friends from 25% to 50% leads to an increase in the person in the income distribution structure by 8.2 percentage points. The authors estimate that moving a child from an area in the bottom 10% of economic connectedness to an area in the top 10% with the highest scores would result in an average 17.5% higher income as an adult.

If we take into account the level of economic connectedness, then the average income level in the area of residence generally loses predictive power in relation to the future income of children. The authors obtain a similar "null" predictive result for indicators of geographic segregation by race, income inequality, or the quality of local schools.

At the same time, living in a low-income area may limit upward mobility - but in the sense that it reduces interaction with people with a higher socioeconomic status, the authors write.

How to improve economic connectivity

The analysis of Chetty and his co-authors indicates that higher economic connectivity primarily affects people from groups with lower socioeconomic status and has little effect on wealthy people - then it turns out that by increasing economic connectivity, the position of less wealthy can be improved. citizens without prejudice to the more affluent.

Of the two factors of economic connectivity—the level of interaction and the propensity to befriend—policies so far have focused primarily on enhancing interaction, the authors write. Such measures include, for example, zoning and affordable housing policies aimed at consolidating neighborhoods; college admissions reforms to increase the social diversity of students. Such measures can significantly increase the interaction between socio-economic groups.

Such measures can significantly increase the interaction between socio-economic groups.

However, even if all groups were fully integrated, half of the social division between people of low and high socioeconomic status would persist due to "friendship bias".

While measures to reduce this bias have been much less explored, there are some positive examples that could be scaled up, the authors suggest.

For example, Berkeley High School has historically had a socio-economically diverse student population, but had a high level of "friendship bias": more than 3,000 students were divided into five communities, each with its own program, leading to hidden segregation, including racial segregation. . To change this, starting in 2018, the school began placing students in small and deliberately diverse "houses". Paying attention to how students are assigned to study groups and reducing the size of those groups can help reduce "friendship bias," Chetty and his team advise.

As another example, management at Lake Highlands School in Texas, also characterized by a high "friendship bias", concluded that some spaces were hindered in forming bonds between children from families with different incomes - for example, the presence of three dining rooms, not all of which were available. budget food. This led to a segregation of students who were grouped into one of three canteens depending on their status and the availability of inexpensive or free meals. The school has attempted to minimize this problem by building a single dining facility and creating more common spaces for all students. While students may continue to huddle into the tight circles they are accustomed to, they have more opportunities to cross paths and interact with peers from other social groups.

By analogy, urban architecture and planning can have an impact on increasing the economic connectedness of citizens - existing examples of social infrastructure redevelopment include public libraries, kindergartens, city parks, as well as public transport connecting people living in different areas.

Another way to reduce the "bias in friendship" could be the creation of new platforms to increase interaction between different socio-economic groups. Researchers cite the Boston fitness center InnerCity Weightlifting as an example, which, in order to increase economic mobility began hiring people who were socially and economically disadvantaged as trainers for wealthy clients, many of whom had prison terms behind them and fell into the category of people about whom they say “either fire a bullet or catch them themselves.” In addition to the fact that such people received a steady income and a way to increase their social capital, and people from the opposite end of the social ladder - the opportunity to learn more about those who shied away from on the street, “something unexpected happened in parallel”, Jonathan Feynman, founder of the fitness center, says: clients began to offer their trainers employment outside the gym, paid for joint vacations for them and their children, and also helped with lawyers and supported in court "when something went wrong. " Such “interclass” communication destroys the system of segregation and racism that pushes people to delinquency, he is sure.

" Such “interclass” communication destroys the system of segregation and racism that pushes people to delinquency, he is sure.

By examining such examples and their impact over time on the interaction of socioeconomic groups and "friendship bias", researchers and policymakers can identify the most progressive ways to increase economic connectivity - the form of social capital that most strongly determines economic mobility, conclude Chetty and his colleagues. co-authors.

Olga Volkova

Econs.online editor

Olga Kuvshinova