How does hiv affect child development

The impact of HIV/AIDS on children in developing countries

Paediatr Child Health. 2005 May-Jun; 10(5): 261–263.

Language: English | French

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

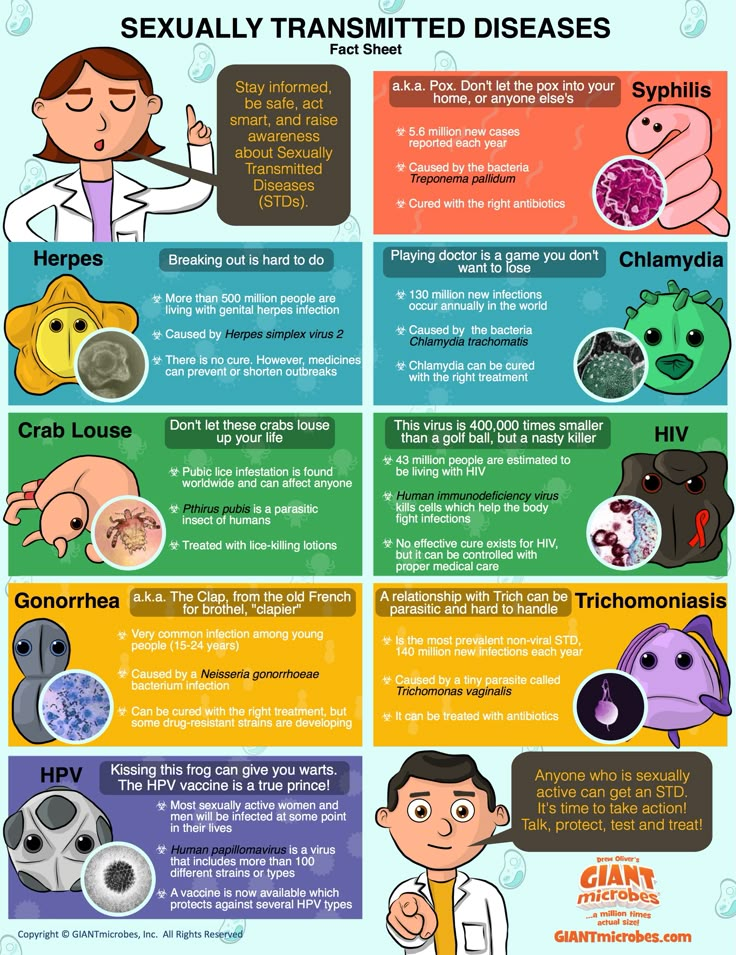

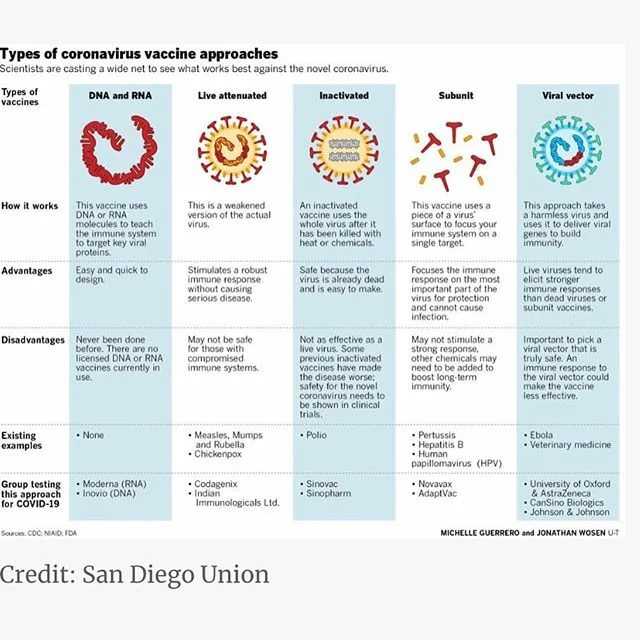

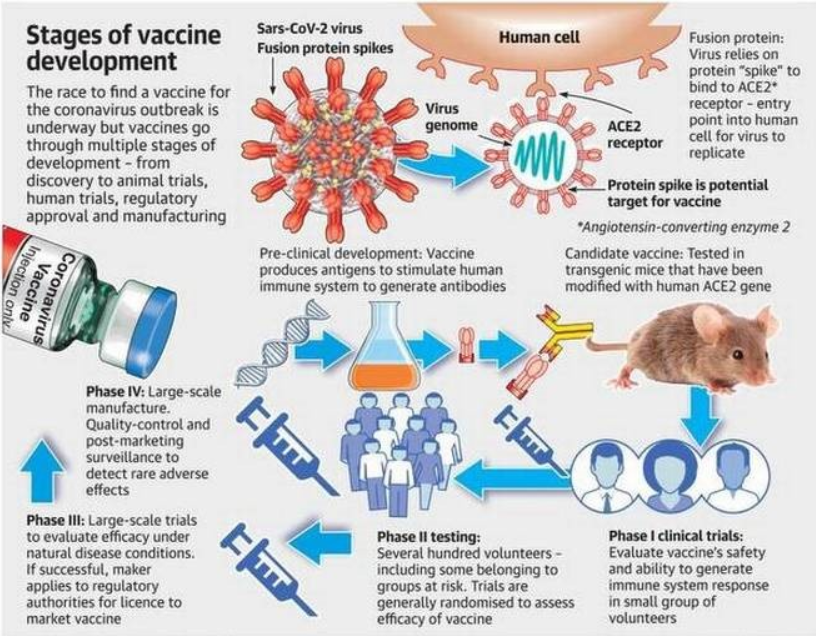

HIV infection and AIDS among children continues to be a significant problem in developing countries despite the progress that has been made in HIV prevention and AIDS treatment elsewhere during the past two decades. The reasons for this difference are complex and multifactorial. They include the higher background prevalence of infection among adults in some communities in developing countries, the slow implementation in many countries of prenatal HIV screening programs and prophylaxis which can reduce the transmission to infants during labor and delivery, the social and health consequences of not breastfeeding, and the economic realities associated with expensive diagnostic testing and antiretroviral treatment. While the world waits for an effective HIV/AIDS vaccine, to reduce the prevalence of HIV in the community, public health programs need to continue to emphasize proven methods of HIV transmission prevention among groups with a high-risk of HIV acquisition, as well as provide counselling for the general population about personal protection and the provision of compassionate care for those affected.

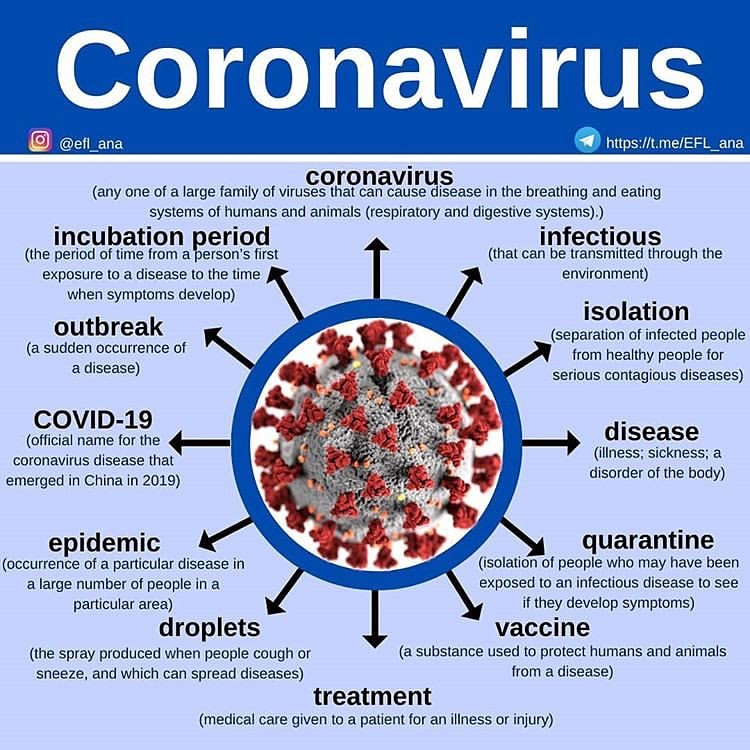

Keywords: HIV infection, Paediatric AIDS, Public health policies

L’infection au VIH et le sida chez les enfants continuent de représenter un grave problème dans les pays en voie de développement, malgré les progrès réalisés dans la prévention du VIH et le traitement du sida dans les autres pays depuis deux décennies. Les raisons de cette différence sont complexes et multifactorielles. Elles incluent l’historique de prévalence d’infection plus élevée chez les adultes de certaines collectivités des pays en voie de développement, la lenteur de l’implantation de programmes de dépistage et de prophylaxie prénatals du VIH dans de nombreux pays, lesquels peuvent réduire la transmission aux nourrissons pendant le travail et l’accouchement, les conséquences sociales et sanitaires de ne pas allaiter et les réalités économiques associées aux tests diagnostiques et aux traitements antirétroviraux coûteux. Tandis que le monde attend un vaccin efficace contre le VIH et le sida, les programmes de santé publique doivent se poursuivre afin de réduire la prévalence du VIH dans la collectivité et de mettre l’accent sur les méthodes éprouvées pour prévenir la transmission du VIH parmi les groupes très vulnérables à l’acquisition de ce virus, ainsi que pour offrir des conseils thérapeutiques à l’ensemble de la population au sujet de la protection personnelle et pour prodiguer des soins compatissants aux personnes atteintes.

Despite the advances of the past two decades in the understanding of the characteristics of HIV, the means to prevent its transmission and the pathophysiology of the progression from HIV infection to symptomatic AIDS, as well as the development of effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection and AIDS among children has emerged as a significant problem in developing countries that has yet to be solved. A comprehensive review of the literature is beyond the scope of the present paper, but it will attempt to provide an overview of the issues relevant to the present situation.

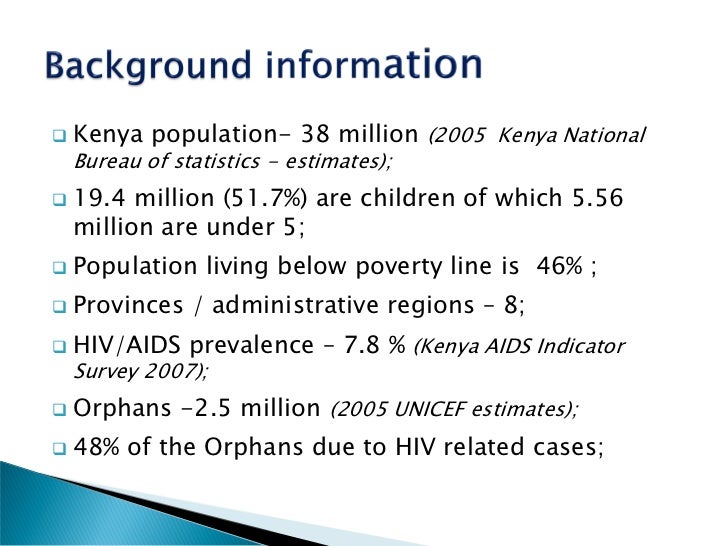

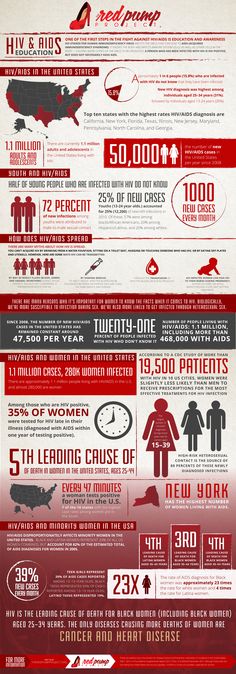

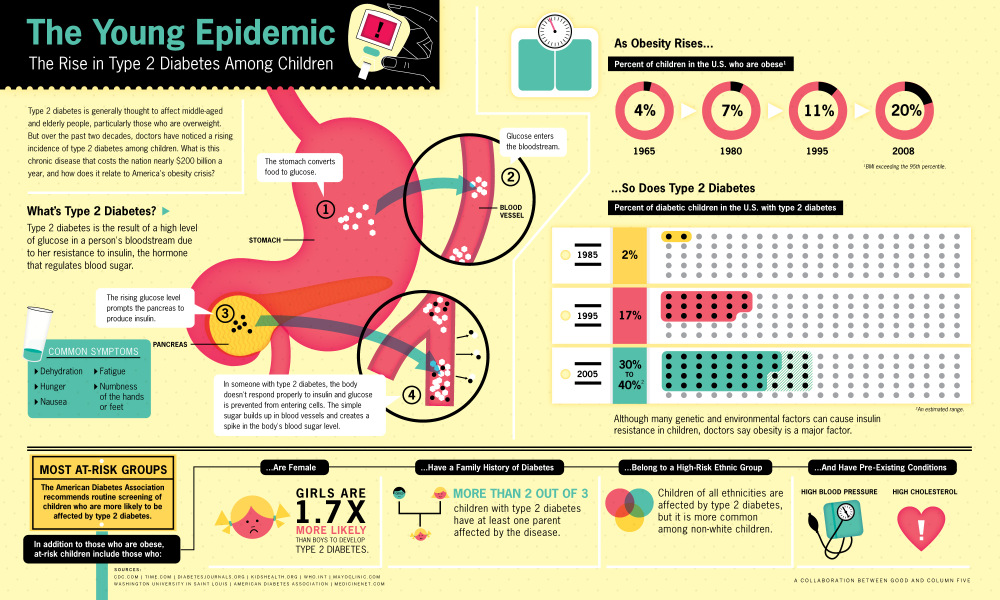

The magnitude of the problem of HIV/AIDS, in terms of the numbers of affected children, is enormous. The World Health Organization estimated that at the end of 2003, there were 2.1 million (95% CI 2.1 to 2.9 million) children living with AIDS worldwide, with 2 to 2.2 million of them residing in Sub-Saharan Africa (1). Also, they estimated that approximately 660,000 children were newly infected in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2003 and approximately 540,000 children died of AIDS in the region. Thus, the absolute number of children living with HIV is continuing to increase. This is in stark contrast to the situation in Canada, where new infections among children have declined and are now rare, with only two to three new infections identified in children each year, and where most infected children are doing well on antiretroviral treatment and death in childhood is unusual (Susan King, Canadian Pediatric AIDS Research Group, personal communication).

Thus, the absolute number of children living with HIV is continuing to increase. This is in stark contrast to the situation in Canada, where new infections among children have declined and are now rare, with only two to three new infections identified in children each year, and where most infected children are doing well on antiretroviral treatment and death in childhood is unusual (Susan King, Canadian Pediatric AIDS Research Group, personal communication).

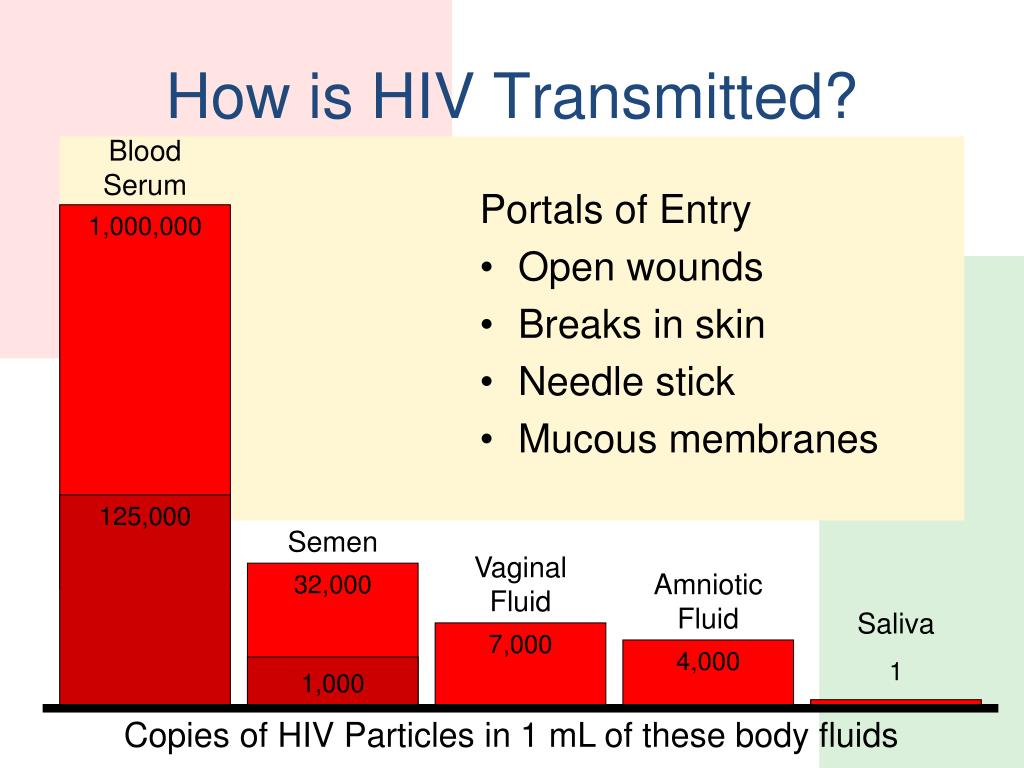

Why is there such a great difference? Although some children may still acquire the virus from injections received from reusable needles, contaminated blood or blood products (despite the implementation of recommendations to prevent this), or from sexual activity, the primary mode of HIV transmission to a child in the developing world is from the infected mother during delivery or from her breast milk. The magnitude of the epidemic among children is therefore directly related to the epidemiology of the infection among adults, in particular, women of childbearing age. In most developing countries, women and men are equally affected, with most of the infected women being those of childbearing age. The prevalence of infection among women attending antenatal clinics and/or presenting to health care units in labour in Sub-Saharan Africa may range from 1% to 2% to as high as 70% in some communities (1). In many regions of eastern and southern Africa, the prevalence is between 15% and 30%. The rates of HIV infection among pregnant women in developing areas of subcontinental India and Asia are considerably lower, ranging from 0.1% to 5%. This still represents a substantial number of infected individuals (taking into account the large population involved). As a further example of the difference between the situation in Canada and that of some developing countries, approximately 10 to 12 HIV-affected pregnancies per year are identified in Manitoba, while 12 to 15 HIV-positive women deliver each day at the study hospital in Nairobi (University of Manitoba/University of Nairobi Mother to Child HIV Transmission Study recruited study subjects from the hospital until 2000) (personal observations).

In most developing countries, women and men are equally affected, with most of the infected women being those of childbearing age. The prevalence of infection among women attending antenatal clinics and/or presenting to health care units in labour in Sub-Saharan Africa may range from 1% to 2% to as high as 70% in some communities (1). In many regions of eastern and southern Africa, the prevalence is between 15% and 30%. The rates of HIV infection among pregnant women in developing areas of subcontinental India and Asia are considerably lower, ranging from 0.1% to 5%. This still represents a substantial number of infected individuals (taking into account the large population involved). As a further example of the difference between the situation in Canada and that of some developing countries, approximately 10 to 12 HIV-affected pregnancies per year are identified in Manitoba, while 12 to 15 HIV-positive women deliver each day at the study hospital in Nairobi (University of Manitoba/University of Nairobi Mother to Child HIV Transmission Study recruited study subjects from the hospital until 2000) (personal observations).

In Canada, we have the facilities to screen pregnant women for HIV, and to provide counselling, antiretroviral therapy, elective cesarean section when necessary and safe alternatives to breastfeeding. As a result, the probability of transmission of HIV from an infected mother to her infant in Canada is approximately 1% to 2%. In many areas of the developing world, screening is difficult, antiretroviral therapy to prevent transmission is not available or less effective protocols are in use, elective cesarean sections are rarely possible, and safe alternatives to breastfeeding are not available or socially acceptable. In these areas, the transmission rate of HIV from an infected mother to her infant varies from 30% to 45% (2). Thus, in those communities with extremely high prevalences of maternal infection and no facilities for prenatal screening or provision of antiretroviral prophylaxis, the percentage of all children born in a community who will acquire HIV infection and ultimately develop AIDS may be as high as 30%. Overall, in Sub-Saharan, eastern and southern Africa, approximately 5% to 10% of all children born in 2005 will likely acquire HIV infection unless effective prevention programs are rapidly instituted.

Overall, in Sub-Saharan, eastern and southern Africa, approximately 5% to 10% of all children born in 2005 will likely acquire HIV infection unless effective prevention programs are rapidly instituted.

There are logistical problems to providing large-scale screening and counselling to pregnant women in a manner that assures safety and confidentiality. However, short courses of zidovudine beginning at 32 weeks gestation or at delivery and the use of nevirapine prophylaxis given to the mother during labour, with a second dose provided to the infant at around 48 h of life, are capable of reducing the risk of transmission to the infant by around 60% (3–6). This effect is tempered by prolonged breastfeeding, but it still represents a substantial reduction in terms of the absolute number of children for whom infection will be prevented. The costs of these medications are not high and programs implementing their use are being introduced. These medications should impact the overall burden of paediatric HIV-related disease by reducing the number of children affected. Unfortunately, these particular drugs have become the mainstay of therapy for adults with HIV/AIDS, which, due to the development of resistant viral strains, may ultimately limit their usefulness in the long term. Whether they will be as effective for subsequent pregnancies is unknown (7,8). Also, their effectiveness may not be as great outside the clinical trial setting (9). Further research and additional strategies, including substituting breast milk with formula, are still necessary.

Unfortunately, these particular drugs have become the mainstay of therapy for adults with HIV/AIDS, which, due to the development of resistant viral strains, may ultimately limit their usefulness in the long term. Whether they will be as effective for subsequent pregnancies is unknown (7,8). Also, their effectiveness may not be as great outside the clinical trial setting (9). Further research and additional strategies, including substituting breast milk with formula, are still necessary.

In Canada, by screening pregnant women for HIV infection and thereby identifying those infants at risk of HIV, we can monitor these children and detect those who are infected early in life before they develop AIDS. Antiretroviral therapy can then be provided early, which significantly delays the deterioration of their immune systems. In contrast, in the developing world, in addition to limited HIV screening in pregnancy, the availability of polymerase chain reaction diagnostic testing to reliably identify infected infants early in life is extremely limited. Also, antiretroviral medications for infants is expensive and not readily available. Therefore, early therapy of HIV-infected infants to prevent the development of AIDS is the exception rather than the common practice in the developing world.

Also, antiretroviral medications for infants is expensive and not readily available. Therefore, early therapy of HIV-infected infants to prevent the development of AIDS is the exception rather than the common practice in the developing world.

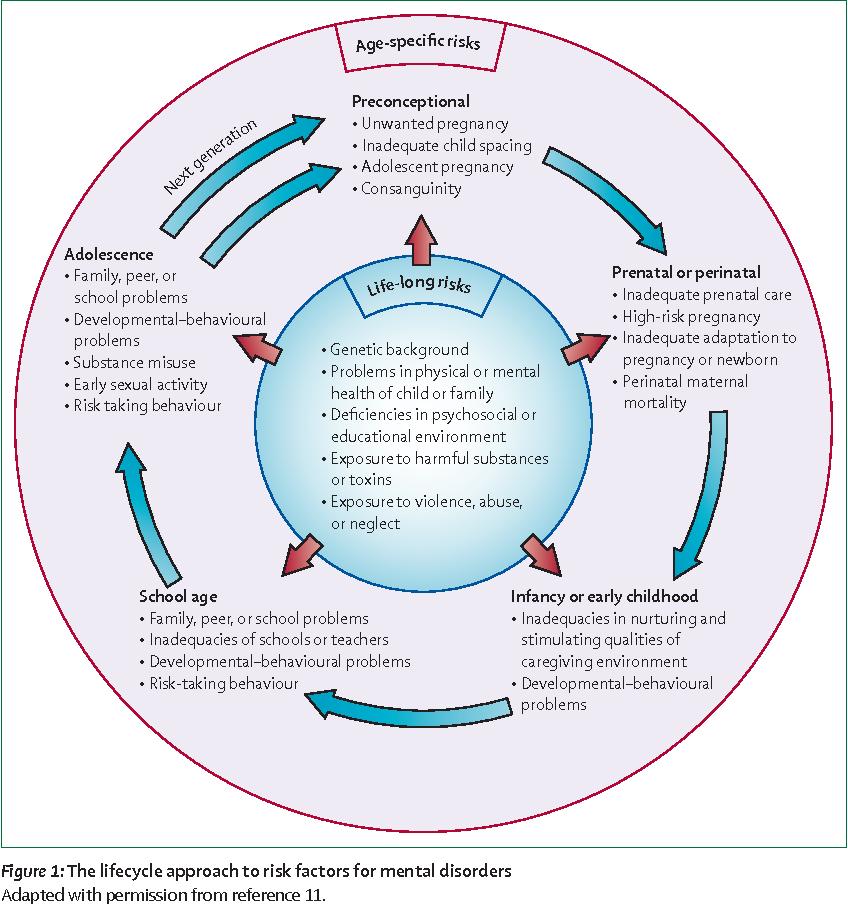

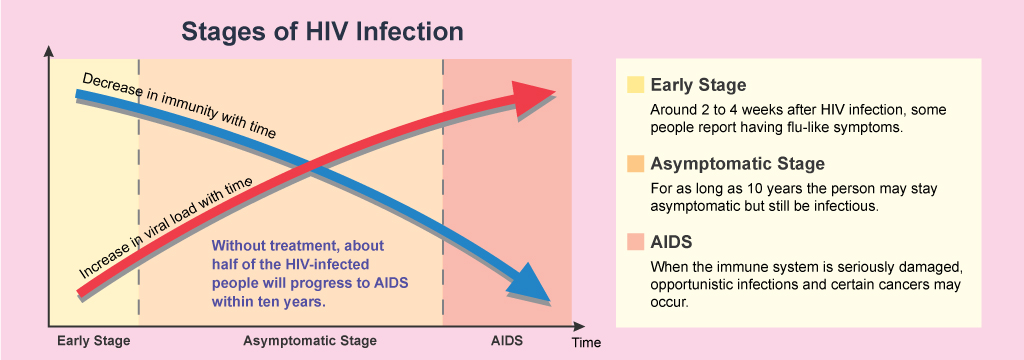

HIV-infected children reside in communities where infectious diseases are common and the background death rate is already high. The estimated infant mortality rate among HIV-infected infants is thought to be at least two- to threefold higher than the background rate (10–12). Although the prospective studies conducted have some limitations, children in developing countries seem to have a bimodal pattern of AIDS development, with approximately one-third of children becoming ill and dying of AIDS in the first year of life and the remainder having a slower rate of progression over the next five years (13).

Generally, the infectious disease patterns of children infected with HIV/AIDS resemble those of other children in their communities. However, these children have more frequent infections, are less likely to recover and have higher rates of associated failure to thrive (12,14–16). For example, in a recent study (14) in rural Kenya of children admitted to hospital with bacteremia, there was no difference in the infecting organisms between HIV-infected and uninfected children, but the rates of infections were two- to sixfold greater among those children who were HIV-infected. Tuberculosis is one specific illness that is significantly over-represented in HIV-infected children in developing countries. Tuberculosis incidence in adults has increased in parallel to the AIDS epidemic in many regions and is a disease that frequently affects HIV-infected children, in part, due to the reactivation of disease in infected parents and other care providers. In Ethiopia, HIV coinfection was found in 11% of children admitted with tuberculosis, and coinfection was associated with higher parental education and income and better living conditions (17). Infant bacille Calmette-Guérin immunization was not found to be protective. Dually infected children tended to be younger, more likely to have associated failure to thrive and six times more likely to die of tuberculosis; however, those who survived were two-thirds as likely to complete therapy and be cured of their tuberculosis (18).

For example, in a recent study (14) in rural Kenya of children admitted to hospital with bacteremia, there was no difference in the infecting organisms between HIV-infected and uninfected children, but the rates of infections were two- to sixfold greater among those children who were HIV-infected. Tuberculosis is one specific illness that is significantly over-represented in HIV-infected children in developing countries. Tuberculosis incidence in adults has increased in parallel to the AIDS epidemic in many regions and is a disease that frequently affects HIV-infected children, in part, due to the reactivation of disease in infected parents and other care providers. In Ethiopia, HIV coinfection was found in 11% of children admitted with tuberculosis, and coinfection was associated with higher parental education and income and better living conditions (17). Infant bacille Calmette-Guérin immunization was not found to be protective. Dually infected children tended to be younger, more likely to have associated failure to thrive and six times more likely to die of tuberculosis; however, those who survived were two-thirds as likely to complete therapy and be cured of their tuberculosis (18). In this and other studies, the clinical and radiographical presentation did not significantly differ between HIV-infected and uninfected children but tuberculin skin reactivity was significantly reduced (19). The efforts to reduce tuberculosis worldwide will ultimately help reduce illness and death among HIV-infected children.

In this and other studies, the clinical and radiographical presentation did not significantly differ between HIV-infected and uninfected children but tuberculin skin reactivity was significantly reduced (19). The efforts to reduce tuberculosis worldwide will ultimately help reduce illness and death among HIV-infected children.

Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, the hallmark infection of HIV before effective antiretroviral therapy in developed countries, is not usually identified in HIV-infected children in developing countries. However, one autopsy series did show that P jiroveci pneumonia was responsible for one-third of all deaths among HIV-infected children and nearly one-half of all deaths among infants younger than one year of age (21). Use of P jiroveci prophylaxis should, therefore, be considered for infants suspected of being HIV infected. In addition, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis was recently shown to dramatically reduce the death rate in HIV-infected children due to bacterial pathogens in Zambia (21). This medication is cheap and widely available and should be considered for routine use in children who have documented HIV infection or for infants with clinical features indicative of a high likelihood of HIV infection.

This medication is cheap and widely available and should be considered for routine use in children who have documented HIV infection or for infants with clinical features indicative of a high likelihood of HIV infection.

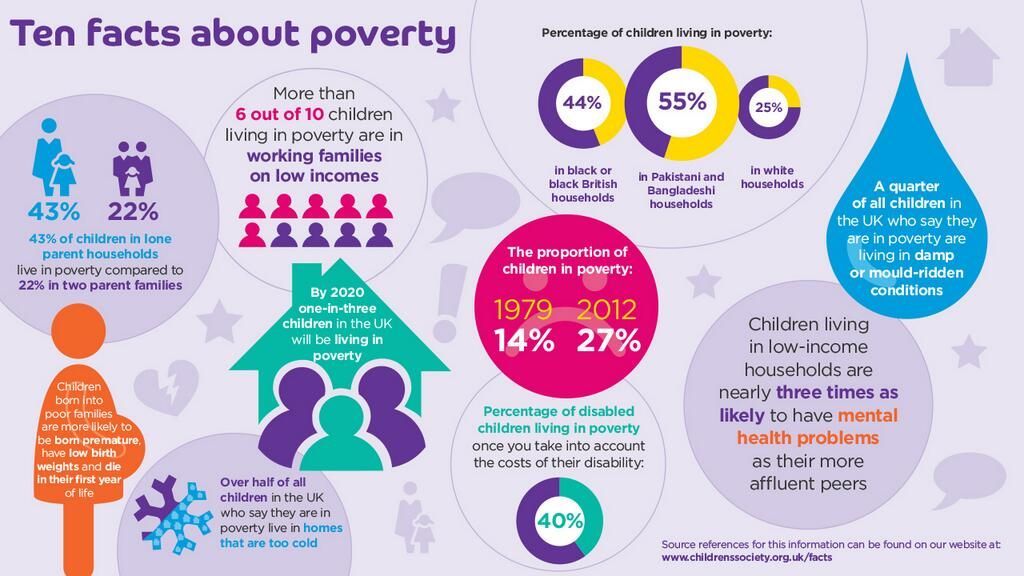

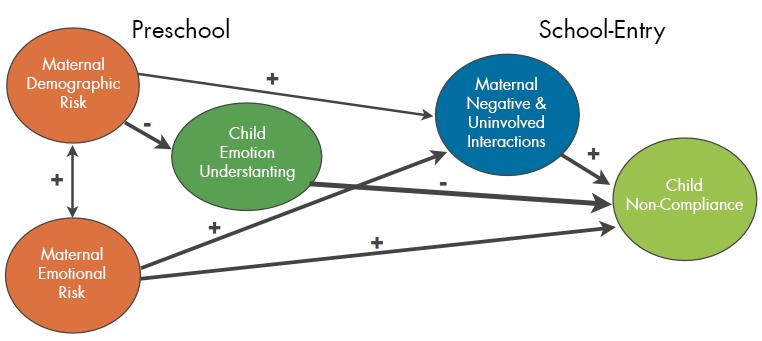

In addition to increased illness and early death, those HIV-infected children who do survive into childhood and adolescence face a number of social problems. They are usually in a family unit where one or more adults are also infected. They may have been taken in by their extended family, placed in an orphanage or live on the streets. There may be limited educational opportunities due to frequent illness, parental HIV-related illness resulting in lowered income for the family unit and inability to pay school fees, or the decision not to devote limited family resources to educate a child who will not likely live to adulthood.

Families in which adults and/or children are identified with HIV infection are at risk of stigmatization in the developing world just as they remain so in other areas. As a result, the community is often hesitant to discuss the parents’ situation or the family’s illness, or to provide counselling. There have been champions for more openness related to AIDS in the developing world. Nelson Mandella has recently joined this cause. It is hoped that he will be able to make a difference.

As a result, the community is often hesitant to discuss the parents’ situation or the family’s illness, or to provide counselling. There have been champions for more openness related to AIDS in the developing world. Nelson Mandella has recently joined this cause. It is hoped that he will be able to make a difference.

There are obviously large obstacles to the universal provision of specific antiretroviral treatment to children in the developing world. As for adults, the issue of the cost of the drugs pales in comparison with the cost of the infrastructure development needed for even minimal monitoring of therapeutic side effects and drug effectiveness on plasma viremia and immune status. However, therapy is slowly becoming available. In addition, there is a need to improve the general health of children in these areas. One solution is to expand the childhood immunization programs to include the newer vaccines against common bacterial and viral pathogens. This intervention would benefit both HIV-infected and uninfected children.

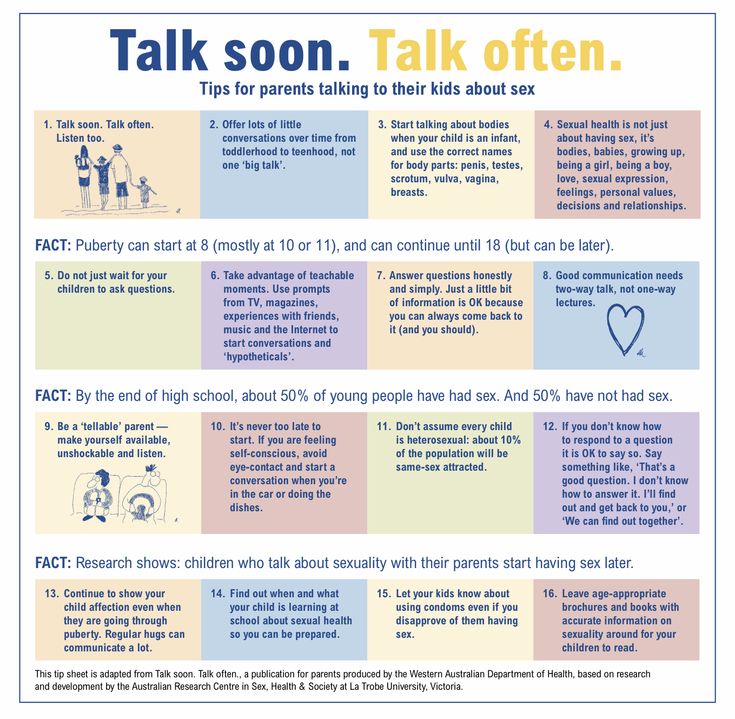

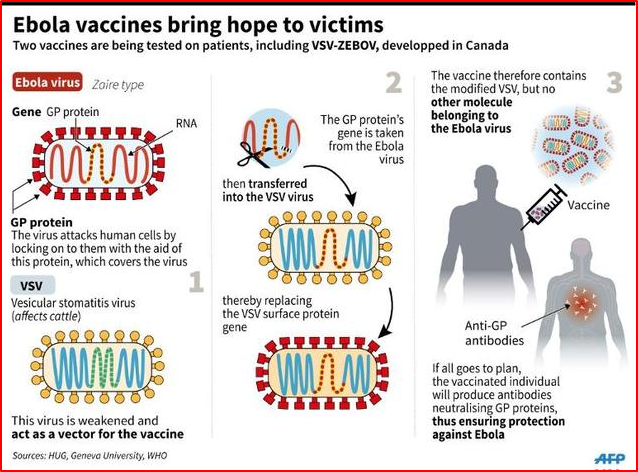

However, despite the advances that have been made, the following observation remains as true today as it was when AIDS was first recognized as a disease of children 20 years ago: the best way to manage paediatric HIV/AIDS in all areas is to prevent children from acquiring HIV by preventing the infection of their mothers. Efforts that result in the reduction of the prevalence of HIV among core groups, such as commercial sex workers who have high levels of transmission, will limit the risk of other groups, such as pregnant women who are not commercial sex workers, and slow the progression of the epidemic in the general population. In addition, provision of appropriate education and counselling regarding sexually transmitted diseases to youth before their sexual debut may help some reduce their personal risk. However, if this is to be successful, there also needs to be active programs to teach parenting skills and to emphasize to those who care for children that they serve as role models for healthy living choices. AIDS needs to be discussed openly. It is hoped that there will ultimately be an effective vaccine to prevent either HIV infection or the development of AIDS in those infected. In the meantime, prevention of HIV infection of infants, children and adolescents needs to be a priority, along with care and compassion for those affected.

AIDS needs to be discussed openly. It is hoped that there will ultimately be an effective vaccine to prevent either HIV infection or the development of AIDS in those infected. In the meantime, prevention of HIV infection of infants, children and adolescents needs to be a priority, along with care and compassion for those affected.

1. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. < www.unaids.org/en/default.asp#> (Version current at May 17, 2005)

2. Datta P, Embree JE, Kriess JK, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: Report of the Nairobi Study. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Brocklehurst P, Volmink J. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD003510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Jackson JB, Musoke P, Fleming T, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: 18-month follow-up of the HIVNET 012 randomized trial. Lancet. 2003;362:859–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lancet. 2003;362:859–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Lallemant M, Jourdain G, Le Coeur S, et al. Single-dose perinatal nevirapine plus standard zidovudine to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:217–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Taha TE, Kumwenda NI, Hoover DR, et al. Nevirapine and zidovudine at birth to reduce perinatal transmission of HIV in an African setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:202–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Lyons FE, Coughlan S, Byrne CM, Hopkins SM, Hall WW, Mulcahy FM. Emergence of antiretroviral resistance in HIV-positive women receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy. AIDS. 2005;19:63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Jourdain G, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Le Coeur S, et al. Intrapartum exposure to nevirapine and subsequent maternal responses to nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:229–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Quaghebeur A, Mutunga L, Mwanyumba F, et al. Low efficacy of nevirapine (HIVNET012) in preventing perinatal HIV-1 transmission in a real-life situation. AIDS. 2004;18:1854–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Low efficacy of nevirapine (HIVNET012) in preventing perinatal HIV-1 transmission in a real-life situation. AIDS. 2004;18:1854–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Spira R, Lepage P, Msellati P, et al. Mother-to-Child HIV-1 Transmission Study Group. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in children: A five year study in Rwanda. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Obimbo E, Mbori-Ngacha DA, Ochieng JO, et al. Predictors of early mortality in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected African children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:536–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Taha TE, Kumwenda NI, Broadhead RL, et al. Mortality after the first year of life among human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and uninfected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:689–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Blanche S, Tardieu M, Dulliege A, et al. Longitudinal study of 94 symptomatic infants with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency infection. Evidence for a bimodal expression of clinical and biological symptoms. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:1210–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evidence for a bimodal expression of clinical and biological symptoms. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:1210–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Berkley JA, Lowe BS, Mwangi I, et al. Bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Jean SS, Pape JW, Verdier R, et al. The natural history of human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection in Haitian infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Embree JE, Datta P, Stackiw W, et al. Increased risk of early measles in infants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seropositive mothers. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:262–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Palme IB, Gudetta B, Degefu H, Bruchfeld J, Muhe L, Giesecke J. Risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus infection in Ethiopian children with tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:1066–72. (Erratum in 2002;21:61) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Palme IB, Gudetta B, Bruchfeld J, Muhe L, Giesecke J. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection on clinical presentation, treatment outcome and survival in a cohort of Ethiopian children with tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:1053–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Impact of human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection on clinical presentation, treatment outcome and survival in a cohort of Ethiopian children with tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:1053–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Madhi SA, Gray GE, Huebner RE, Sherman G, McKinnon D, Pettifor JM. Correlation between CD4+ lymphocyte counts, concurrent antigen skin test and tuberculin skin test reactivity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and -uninfected children with tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:800–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Ansari NA, Kombe AH, Kenyon TA, et al. Pathology and causes of death in a series of human immunodeficiency virus-positive and -negative pediatric referral hospital admissions in Botswana. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:43–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Chintu C, Bhat GJ, Walker AS, et al. Co-trimoxazole as prophylaxis against opportunistic infections in HIV-infected Zambian children (CHAP): A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1865–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lancet. 2004;364:1865–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

HIV and Children - POZ

We have made tremendous progress in terms of reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission. Provided that a woman living with HIV takes good care of herself and her developing baby, which includes getting proper prenatal care and taking a combination of HIV medications during pregnancy, labor and delivery—the risk of HIV transmission is less than 2 percent.

Today, thanks to early access to care and advances in HIV drug treatment, being a child living with HIV is not nearly as dire as it once was. And with more information quickly emerging with respect to how children living with HIV should be treated, we can expect the success rate to improve significantly.

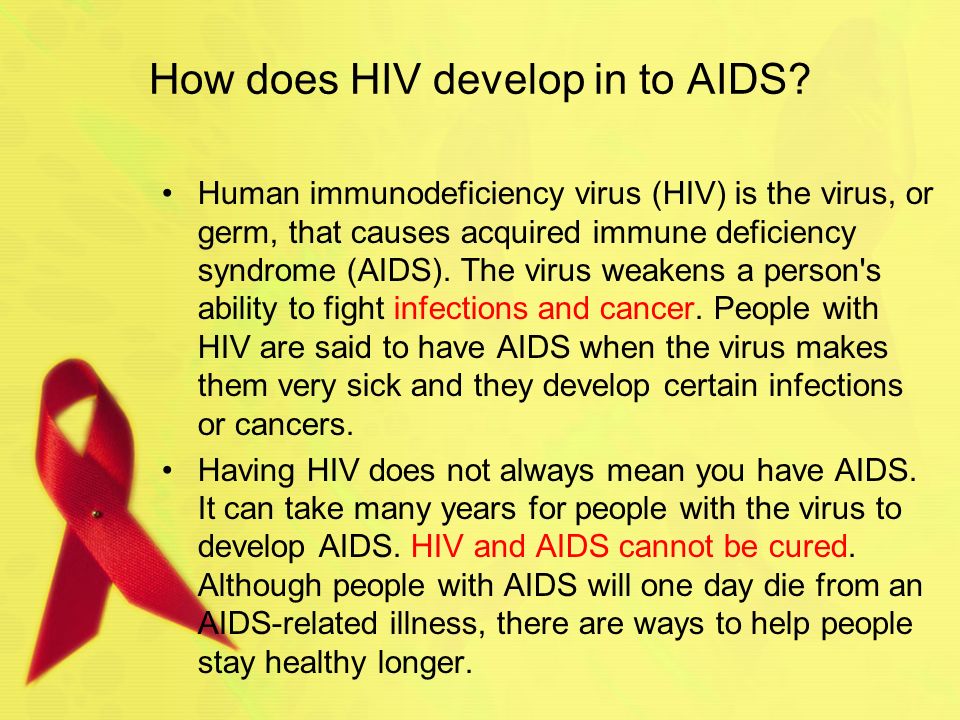

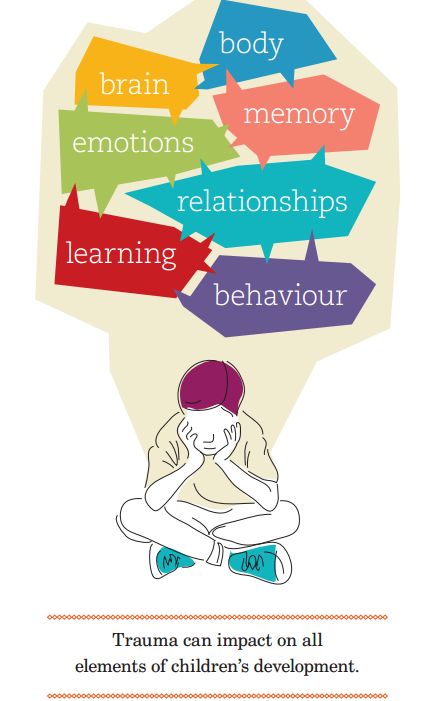

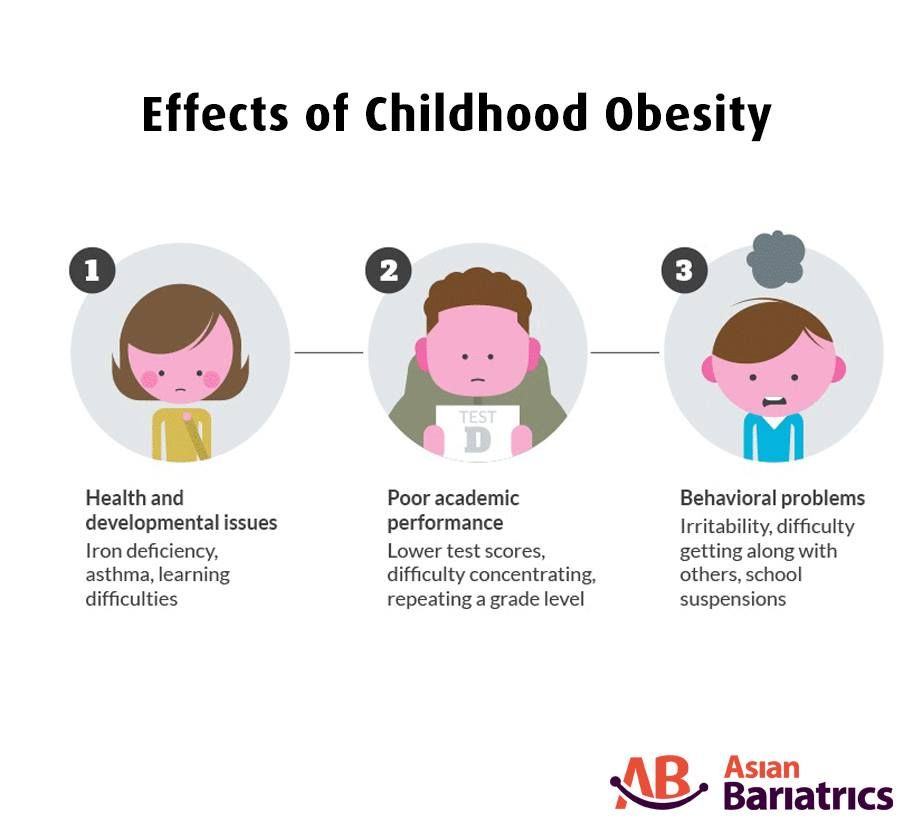

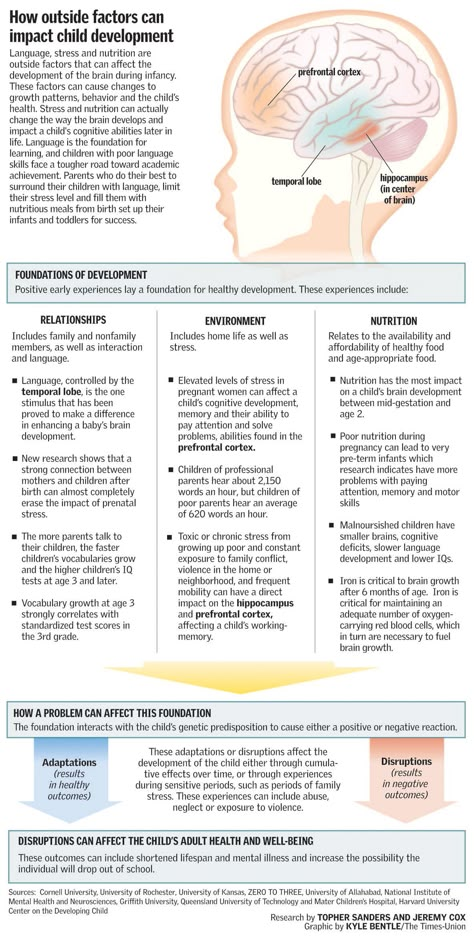

Nonetheless, caring for a child who is HIV positive comes with many challenges. HIV, even during the earliest stages of infection, can severely affect a child’s development, whether related to physical growth, psychological evolvement, or emotional well-being.

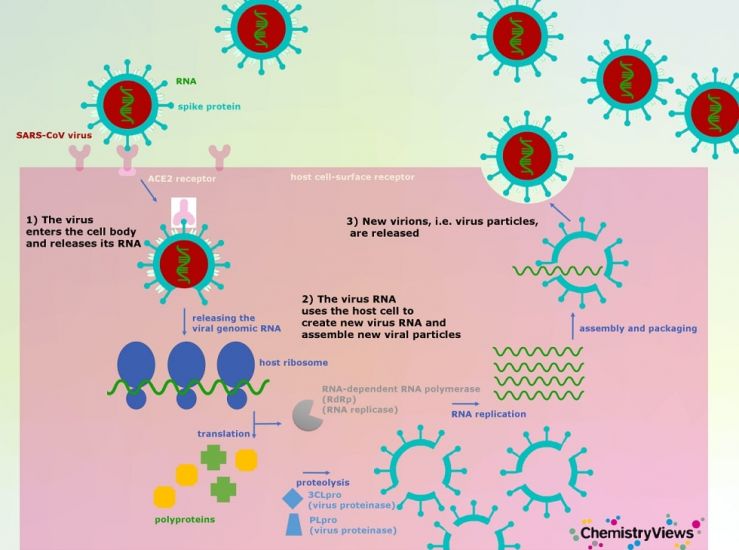

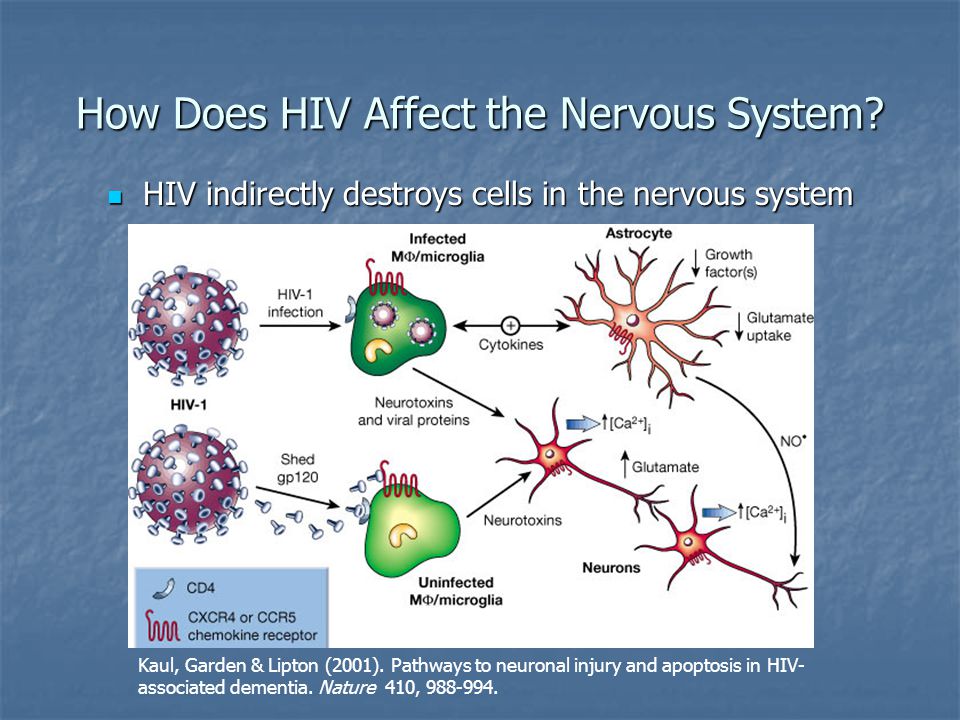

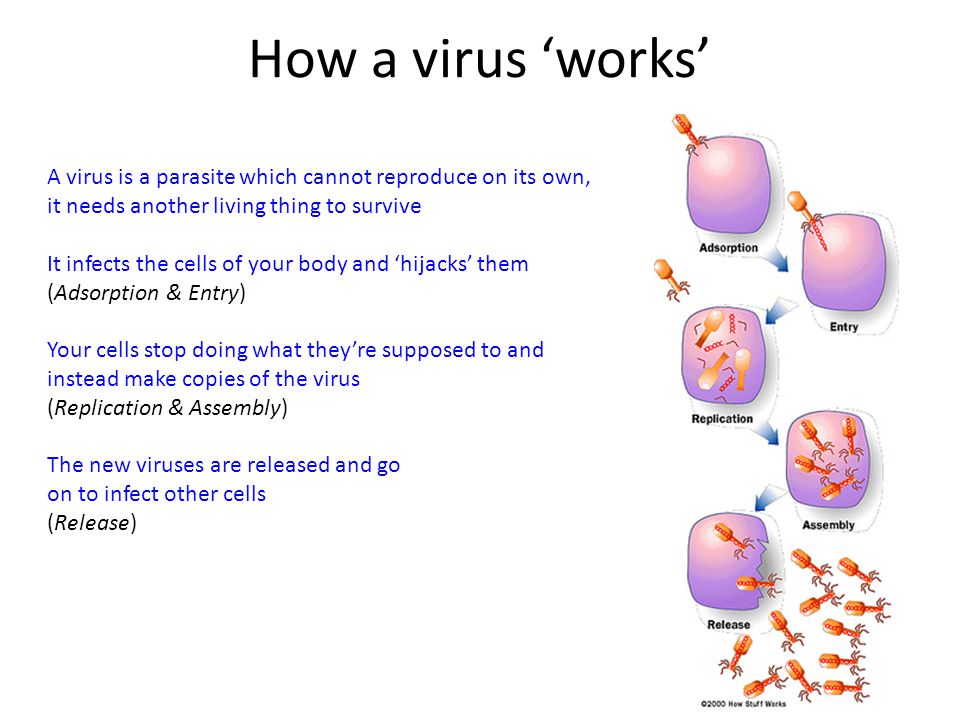

Children have different immune systems than adults. HIV rapidly impairs a child’s immune system ability to control common childhood infections, such as bacterial-associated lung and ear infections and viral infections like chicken pox. HIV also prevents the immune system from producing memory cells which, in adults, help ward off life-threatening infections like Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), and cytomegalovirus (CMV). What’s more, many children living with HIV are born to mothers who abused alcohol and/or drugs while pregnant, which can worsen problems caused by HIV infection.

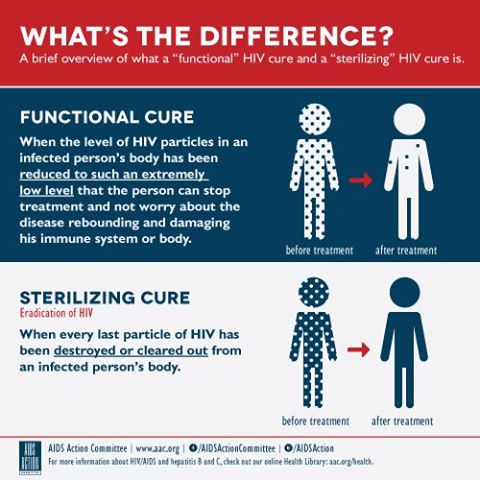

Researchers have shown that babies with HIV tend to have higher viral loads than adults. As a result, the lessons we have learned about treating adults with HIV hold true for children infected with the virus: a powerful combination of drugs should be used to lower a child’s viral load to the lowest possible level.

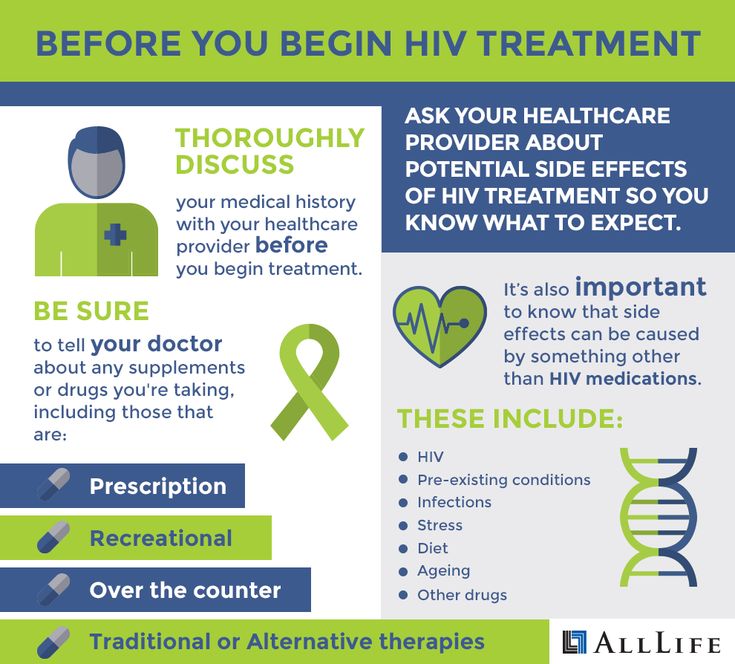

Are HIV meds safe for children?

Many clinical trials have determined that some HIV drugs, particularly when used in combination with each other, work well and are safe in children. However, it is important to recognize that many HIV drugs are absorbed, metabolized and eliminated from the body differently in children than in adults. Fortunately, many of the drugs used to treat adults with HIV can also be used to treat children with HIV infection. In fact, many have also been found to be safe and effective for newborns and infants infected with the virus.

However, it is important to recognize that many HIV drugs are absorbed, metabolized and eliminated from the body differently in children than in adults. Fortunately, many of the drugs used to treat adults with HIV can also be used to treat children with HIV infection. In fact, many have also been found to be safe and effective for newborns and infants infected with the virus.

When should children start HIV treatment?

The United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)—a branch of the federal government that oversees health care policy in the United States—has published guidelines focusing on how best to treat HIV-positive children. These guidelines are important, as they help to make sure that all HIV-positive children in the United States are sufficiently cared for and treated.

The guidelines, which were updated in April 2019, are based on data collected from a number of studies—along with expert opinions—focusing on the importance of treating HIV-positive children, including the best time to start treatment and the best treatments to use.

Click here for the DHHS recommendations of when HIV treatment should be started by HIV-positive children.

If you are caring for a child living with HIV who is not being treated or have questions about starting your child on antiretroviral medications, be sure to discuss these issues with your child’s pediatrician.

Once HIV treatment is started, the child living with HIV will need to be monitored regularly to make sure that the medications are working well and not causing any serious side effects. If a significant problem arises while on therapy—such as a viral load becoming and/or remaining detectable, suppression of the immune system, symptoms of infection, slowed development of the central nervous system or growth failure —a switch in therapy might be necessary.

What drug combinations are recommended for children?

As is the case with adults infected with HIV, children living with HIV almost always need to be treated with a combination of drugs to help push their viral loads to undetectable levels. This helps delay drug resistance, prolong the effects of treatment and keeps the immune system functioning properly.

This helps delay drug resistance, prolong the effects of treatment and keeps the immune system functioning properly.

Click here for the DHHS treatment guidelines on what regimens are recommended for initial therapy of children living with HIV.

What about opportunistic infections?

As with adults, children living with HIV need to take preventive therapies (prophylaxis) to ward of common childhood and AIDS-related infections. It’s estimated that 20 percent of children living with HIV will have an opportunistic infection within the first year of their life.

All children less than 1 year of age must take Bactrim or Septra (TMP-SMX)—or if they are allergic to sulfa-based drugs, either dapsone or aerosolized pentamidine (NebuPent)—to prevent Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP). Children between the ages of 1 and 2 should take PCP prophylaxis if their CD4 cells fall below 750. Two- to five-year-olds with CD4 cell counts below 500 should also be taking prophylaxis, as should all children six years or older with CD4 counts below 200 (similar to adult recommendations).

A rather unique HIV-related problem among children is lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis (LIP). LIP is caused by a hyperactive immune response to a usually harmless infection in the lungs. The symptoms are similar to those of asthma (e.g., coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, tightness in the chest) and, likewise, are treated with corticosteroids like prednisone, and with inhalers to ease breathing.

Conclusion

While research continues to show that HIV therapy has made a tremendous impact on the lives of children living with HIV, it’s not yet entirely understood to what extent these powerful drugs affect young immune systems. In turn, maintaining children on treatment remains the standard of care, and it is still not clear whether or not immune system-related complications, such as LIP, are less likely to occur during successful HIV therapy.

The bottom line is that the care and treatment of our youngest patients with HIV has come a long, long way in recent years. While it will take some time to sort out the unique complications facing children living with HIV, fortunately, time is one thing many of those children now have.

While it will take some time to sort out the unique complications facing children living with HIV, fortunately, time is one thing many of those children now have.

Last Reviewed: April 16, 2019

- #adolescent

- #babies

- #children

- #HIV treatment guidelines

Read More About:

Family and children - AIDS Center

HIV and family life

A positive HIV test result is by no means a reason to give up personal happiness. Including from becoming parents of healthy children. After all, they are your hope for the future, the best incentive for successful therapy and taking care of your own health. But a family in which one or both spouses are HIV-positive should approach the issue of having a child as responsibly as possible.

Even if both partners are positive, they should not have unprotected sex. This rule must be observed in order to avoid secondary infection with another strain of HIV, hepatitis and other diseases.

Talk to your loved one about your options for conceiving. Choose the one that suits you the most. Make a decision carefully assessing all possible risks. And make sure that everything will work out for you.

Be sure to consult with doctors: both the specialist who accompanies your treatment for HIV infection, and the obstetrician-gynecologist. They will help you determine whether your couple is ready for pregnancy and the birth of a baby. And also choose the method of conception that is right for you.

Having problems conceiving does not mean that they are related to HIV. Be sure to consult with your doctor about the options for solving the problem in your situation. You can seek help from a fertility clinic where doctors have experience working with HIV-positive patients.

Have a healthy baby? YES!

An HIV-positive woman can give birth to a healthy baby. Or rather, she is simply obliged to do everything possible so that HIV is not transmitted to the child. This risk can be significantly minimized only by following certain rules.

HIV can be transmitted from a woman to her baby in only three ways:

1. In utero.

2. During childbirth.

3. When breastfeeding.

How to avoid?

1. Drug prophylaxis. In order to reduce the concentration of the virus in the blood and prevent infection of the child, a pregnant woman is prescribed a course of drugs used to treat HIV infection. Antiretroviral drugs are also given to the woman during childbirth (intravenously) and to the newborn (in the form of syrup). The timely start of taking medications can reduce the amount of virus in the blood of a pregnant woman to undetectable and almost completely prevent infection of the baby.

2. Caesarean section. If antiretroviral prophylaxis for some reason has not been carried out or has been ineffective, then women living with HIV are recommended a planned caesarean section. Carrying out this operation avoids additional contact with blood during natural childbirth and reduces the possible risk of infection of the child.

If antiretroviral prophylaxis for some reason has not been carried out or has been ineffective, then women living with HIV are recommended a planned caesarean section. Carrying out this operation avoids additional contact with blood during natural childbirth and reduces the possible risk of infection of the child.

Important! The final decision on the need for a caesarean section is made by the obstetrician-gynecologist individually, taking into account the state of health of the pregnant woman.

3. Not breastfeeding. To protect the child from HIV infection through breast milk, the mother needs to use only artificial feeding. Currently, breast milk replacement formulas are fully adapted to the needs of the baby and guarantee excellent growth and development.

There is no scientific evidence that pregnancy can accelerate the development of HIV infection. To protect the baby from developmental pathologies and intrauterine diseases, like all pregnant women, women with HIV-positive status should change their lifestyle to a healthier one. Complete rejection of alcohol, cigarettes and, of course, drugs. A woman needs to eat a balanced diet and follow all the recommendations of the attending physician. Strictly adhere to the course of antiviral therapy. Without proper precautions during pregnancy, childbirth and after them, the risk of HIV infection in a newborn reaches 40%. With timely prevention, it can be reduced to 1-2%.

Complete rejection of alcohol, cigarettes and, of course, drugs. A woman needs to eat a balanced diet and follow all the recommendations of the attending physician. Strictly adhere to the course of antiviral therapy. Without proper precautions during pregnancy, childbirth and after them, the risk of HIV infection in a newborn reaches 40%. With timely prevention, it can be reduced to 1-2%.

Pregnant life with HIV

A pregnant woman should not smoke, drink alcohol or use drugs. Pregnancy may end prematurely, and the child will be born with congenital diseases, low weight and will grow and develop poorly. Also, in some cases, the risk of intrauterine infection of the child with HIV infection increases.

Give up bad habits even at the stage of pregnancy planning - not only for the sake of maintaining your health, but also in order to help your unborn child.

It is important to have a nutritious and balanced diet. Your diet should now include a variety of high-quality foods. There is a direct link between poor maternal nutrition and a high risk of HIV transmission to the child. Proper nutrition is also important to ensure that all organs and systems of the unborn baby are properly formed and developed. Talk to your doctor - he will tell you how to make the right diet for you. Strictly follow all his recommendations.

There is a direct link between poor maternal nutrition and a high risk of HIV transmission to the child. Proper nutrition is also important to ensure that all organs and systems of the unborn baby are properly formed and developed. Talk to your doctor - he will tell you how to make the right diet for you. Strictly follow all his recommendations.

Create an atmosphere of calm and comfort around you. Stress and depression reduce immunity and disrupt the protective functions of the placenta. This can lead to preterm birth or increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Strong shocks affect the baby in the womb - both physically and psychologically.

After all, a child can receive signals about the mother's emotional state both through her hormonal system and directly with the help of the senses.

The baby feels the beating of the mother's heart, feels the stroking of the abdomen. And if the mother is calm, the baby feels good and develops correctly.

Get more rest and sleep. Pregnancy is not a reason to stop an active social life. But now you need to think about how to help your body during pregnancy. Try to sleep at least 8 hours a day and do not deny yourself the pleasure of lying down during the day. Ask loved ones to help you with heavy homework. And be sure to walk every day for at least an hour. While walking, oxygen actively enters the baby's body through the placenta and improves its growth and development. In addition, walking in the fresh air stimulates the immunity of the expectant mother, which makes the treatment of HIV infection during pregnancy more effective.

Pregnancy is not a reason to stop an active social life. But now you need to think about how to help your body during pregnancy. Try to sleep at least 8 hours a day and do not deny yourself the pleasure of lying down during the day. Ask loved ones to help you with heavy homework. And be sure to walk every day for at least an hour. While walking, oxygen actively enters the baby's body through the placenta and improves its growth and development. In addition, walking in the fresh air stimulates the immunity of the expectant mother, which makes the treatment of HIV infection during pregnancy more effective.

It is very important for a pregnant woman to stay in good physical shape. After all, the load on her body is constantly increasing, and he has yet to prepare for childbirth. In addition, sufficient physical activity during pregnancy helps in the prevention of its complications: edema, shortness of breath, back pain and even depression.

Physically active mothers have fewer symptoms of toxicosis, and their babies develop better, since movement activates the blood circulation process, including in the placenta.

If you want and are ready to have a child, do it. Even with a positive HIV status, you can become a mother of a healthy baby.

HIV and pregnancy

Every pregnant woman registered with the antenatal clinic must be tested for HIV twice - at the first visit and in the third trimester. If a positive or doubtful test for antibodies to HIV is detected, the woman is immediately sent for a consultation to the AIDS Center to clarify the diagnosis.

Mother-to-child transmission of HIV is possible during pregnancy, more often in late pregnancy, during childbirth and while breastfeeding.

Without preventive measures, the risk of HIV transmission is up to 30%. The risk of infection of the child increases if the mother was infected within six months before the onset of pregnancy or during pregnancy, and also if the pregnancy occurred in the late stages of HIV infection. The risk increases with a high viral load (the amount of virus in the blood) and low immunity. An increase in the risk of infection of the child occurs with repeated pregnancies.

An increase in the risk of infection of the child occurs with repeated pregnancies.

With proper preventive measures, the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection is reduced to 2%.

In this brochure you will find information on how to reduce the risk of infection of a child and on the terms of dispensary observation of a child at the AIDS Center.

Reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection

When contacting the AIDS Center, a pregnant woman receives advice from an infectious disease specialist, an obstetrician-gynecologist, a pediatrician; passes all the necessary tests (viral load, immune status, etc.), after which the issue of prescribing antiretroviral (ARV) drugs to the woman is decided. When ARV drugs are taken correctly, the amount of virus in the blood decreases and the risk of passing HIV to an unborn child is reduced. The choice of the regimen and the term of prescription of ARV drugs is decided individually. The safety of their use for the fetus and the pregnant woman herself has been proven. The medicines are given out free of charge according to the prescriptions of the doctors of the AIDS Center.

The safety of their use for the fetus and the pregnant woman herself has been proven. The medicines are given out free of charge according to the prescriptions of the doctors of the AIDS Center.

The effectiveness of drugs should be checked by the end of pregnancy (laboratory viral load test).

A pregnant woman must continue to be observed at the antenatal clinic at the place of residence.

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV includes 3 stages:

1 stage. Taking medication by a pregnant woman. Prevention should be started as early as possible, preferably from 13 weeks of gestation, with three drugs and continued until delivery.

Stage 2. Intravenous administration of an ARV drug to a woman during childbirth (“dropper”).

Stage 3. Taking medications for a newborn baby. Taking drugs by a child begins in the first 6 hours after birth (no later than 3 days). Most children receive zidovudine syrup at a dose of 0. 4 ml per 1 kg of body weight twice a day (every 12 hours) for 28 days. In special cases, the doctor can add 2 more drugs to the child for prevention: viramune suspension - 3 days, epivir solution - within one week.

4 ml per 1 kg of body weight twice a day (every 12 hours) for 28 days. In special cases, the doctor can add 2 more drugs to the child for prevention: viramune suspension - 3 days, epivir solution - within one week.

Births take place in maternity hospitals where the woman lives. Maternity hospitals in the Kostroma region are provided with all the necessary ARV drugs for prevention. The method of delivery (natural childbirth or caesarean section) is chosen by the general decision of the infectious disease specialist and obstetrician-gynecologist.

Breastfeeding is one of the ways of transmission of HIV infection (not only breastfeeding, but also feeding with expressed milk).

Without exception, women with HIV should not breastfeed!

Timing of examination of children born to HIV-infected mothers in the first year of life.

Before the age of 1 year, the child is examined three times:

- In the first 2 days after birth, blood is taken in the maternity hospital for HIV testing by PCR (detects virus particles) and ELISA (detects antibodies - protective proteins produced by the human body for the presence of infection ) for delivery to the AIDS Center.

- At 1 month of age - blood is taken for HIV by PCR in a children's clinic or hospital, in the HIV prevention office at the place of residence (if you have not donated blood at the place of residence, this will need to be done at the AIDS Center at 2 months).

- At 4 months of age - you must come to the AIDS Center to examine the child by a pediatrician and test the blood for HIV by PCR. Also, the doctor may prescribe additional tests for your child (immune status, hematology, biochemistry, hepatitis C, etc.).

If you missed one of the examination dates, do not postpone it until a later time. At the age of 1 month and up to 1 year of life, the child must be tested for HIV by PCR at least 2 times!

What do the test results mean?

Positive blood test for HIV antibodies

All children of HIV-positive mothers are also positive from birth, and this is normal! The mother passes on her proteins (antibodies) in an attempt to protect the baby. Maternal antibodies should leave the blood of a healthy child by 1.5 years (on average).

Maternal antibodies should leave the blood of a healthy child by 1.5 years (on average).

Positive PCR result

This test directly detects the virus itself, which means that a positive PCR may indicate a possible infection of the child. An urgent appearance of the child in the AIDS Center for rechecking is required.

Negative PCR

Negative result - the best result! Virus not detected.

- A negative PCR on the second day of a child's life indicates that the child most likely did not become infected during pregnancy.

- Negative PCR at 1 month of life says that the child was not infected during childbirth. The reliability of this analysis at the age of one month is about 93%.

- Negative PCR over 4 months of age - the child is not infected with a probability of almost 100%.

Examinations of children from 1 year.

If a child already has a negative blood test for HIV by PCR, the main method of research from the age of 1 year is the determination of antibodies to HIV in the child's blood. The average age when the child's blood is completely "cleared" of maternal proteins is 1.5 years.

The average age when the child's blood is completely "cleared" of maternal proteins is 1.5 years.

- At the age of 1, the child donates blood for HIV antibodies at the AIDS Center or at the place of residence. If a negative test result is obtained, repeat after 1 month and the child can be deregistered ahead of schedule. A positive or questionable result for HIV antibodies requires a retake after 1.5 years.

- Over 1.5 years of age, one negative HIV antibody result is sufficient to deregister a child if previous tests are available.

Deregistration of children

- Age of the child is over 1 year;

- Presence of two or more negative PCR tests over 1 month of age;

- Having two or more negative HIV antibody tests over 1 year of age;

- Not breastfeeding in the last 12 months.

Confirmation of the diagnosis of HIV infection in a child

Confirmation is possible at any age from 1 to 12 months with two positive HIV PCR results.

In children older than 1.5 years, criteria for diagnosis as adults (presence of a positive blood test for antibodies to HIV).

The diagnosis is confirmed only by specialists from the AIDS Center.

Children with HIV infection are constantly under the supervision of a pediatrician of the AIDS Center, as well as in the children's polyclinic at the place of residence. HIV infection may be asymptomatic, but there comes a time when the doctor will prescribe treatment for the child. Modern drugs can suppress the immunodeficiency virus, thereby eliminating its effect on the body of a growing child. Children with HIV can lead a full life, visit any children's institutions on a general basis.

Vaccination

Children of positive mothers are vaccinated like all other children according to the national calendar, but with two exceptions:

- The polio vaccine must be inactivated (not live).

- Permission for the BCG vaccination (vaccination against tuberculosis), which is usually given in the maternity hospital, you will receive from the pediatrician of the AIDS Center

Pediatric department phone: 8-9191397331 (from 0900 to 1500 except Thursdays).