How does child soldiers violate human rights

Children recruited by armed forces or armed groups

Programme

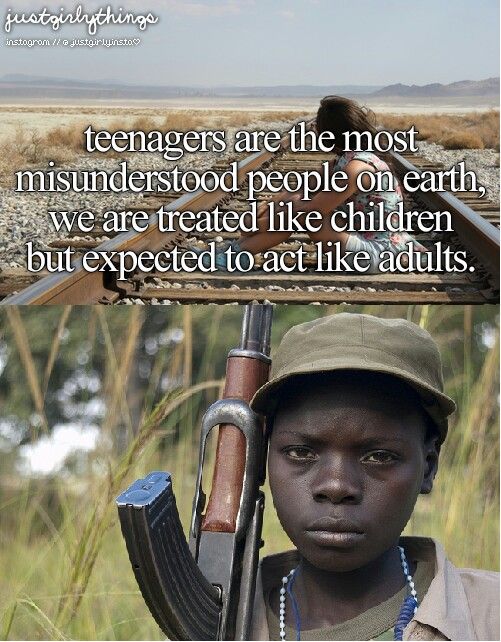

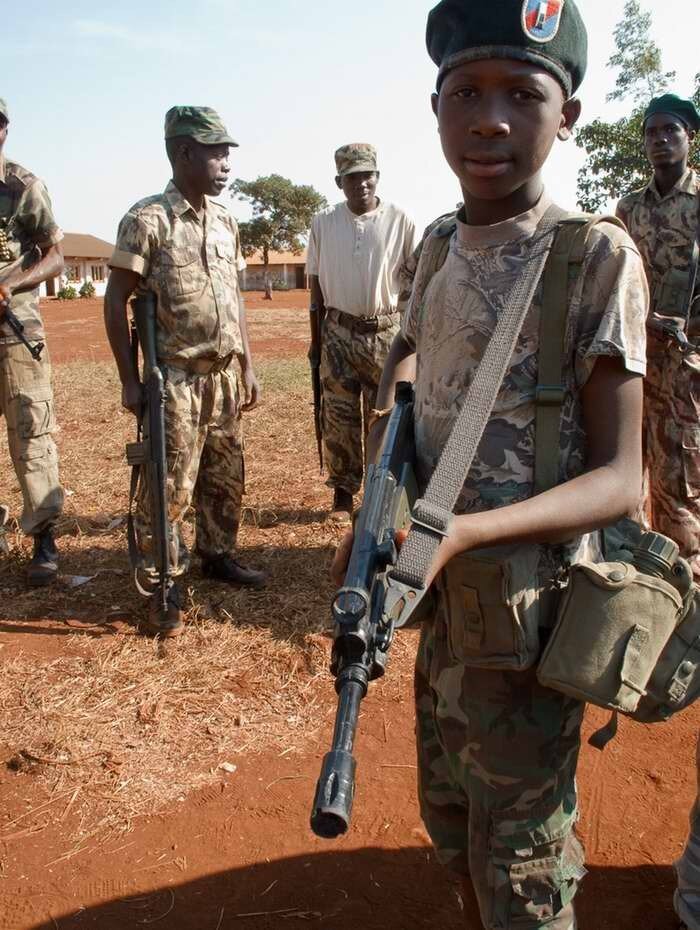

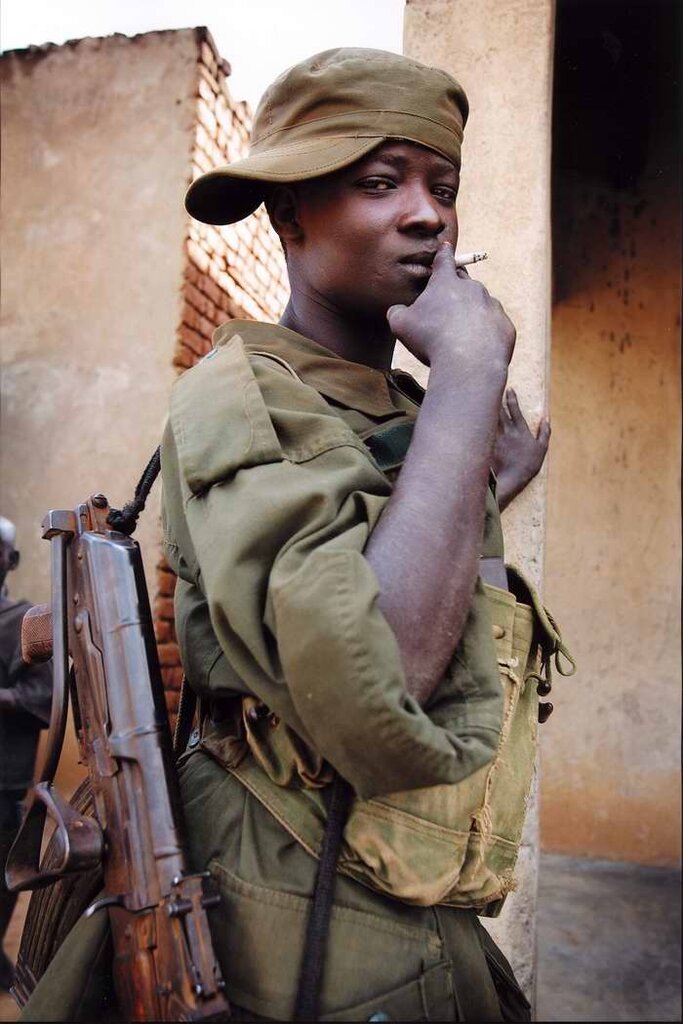

Thousands of boys and girls are used as soldiers, cooks, spies and more in armed conflicts around the world.

UNICEF/UN0202141/Rich

Thousands of children are recruited and used in armed conflicts across the world. Between 2005 and 2020, more than 93,000 children were verified as recruited and used by parties to conflict, although the actual number of cases is believed to be much higher.

Often referred to as “child soldiers,” these boys and girls suffer extensive forms of exploitation and abuse that are not fully captured by that term. Warring parties use children not only as fighters, but as scouts, cooks, porters, guards, messengers and more. Many, especially girls, are also subjected to gender-based violence.

Children become part of an armed force or group for various reasons. Some are abducted, threatened, coerced or manipulated by armed actors. Others are driven by poverty, compelled to generate income for their families. Still others associate themselves for survival or to protect their communities. No matter their involvement, the recruitment and use of children by armed forces is a grave violation of child rights and international humanitarian law.

The recruitment and use of children by armed forces or armed groups is a grave violation of child rights and international humanitarian law.

While living among armed actors, children experience unconscionable forms of violence. They may be required to participate in harrowing training or initiation ceremonies, to undergo hazardous labour or to engage in combat – with great risk of death, chronic injury and disability. They may also witness, suffer or be forced to take part in torture and killings. Girls, especially, can be subjected to gender-based violence.

Warring parties also deprive children of nutrition and healthy living conditions, or subject them to substance abuse, with significant consequences for their physical and mental well-being.

These experiences take a heavy toll on children’s relationships with their families and communities.

Children who have been recruited or used by armed actors may be viewed with suspicion, or outright rejected, by their families and communities.

Whether or not children are accepted back into society depends on various factors, including their reason for association with armed actors, and the perceptions of their families and communities. Some children who attempt to reintegrate are viewed with suspicion or outright rejected, while others may struggle to fit in. Psychological distress can make it difficult for children to process and verbalize their experiences, especially when they fear stigma or how people will react.

What’s more, families and communities may be coping with their own challenges and trauma from conflict, and have trouble understanding or accepting children who return home. Communities need support to care for their returning children – just as the thousands of boys and girls who exit armed forces each year need it to rebuild their futures.

UNICEF’S response

UNICEF/NYHQ2012-0883/Sokol Many girls associated with armed forces or groups regularly experience gender-based violence. This girl was 16 when she managed to exit the armed group that held her in the Central African Republic.

UNICEF partners with governments, community groups and others to address the drivers of child recruitment and stop violations before they occur.

We support the release and reintegration of thousands of children who exit armed forces and groups each year – providing a safe place for them to live upon release, as well as community-based services for case management, family tracing, reunification and psychosocial support. We also provide specialized support for survivors of gender-based violence.

What’s more, UNICEF links children and families to mental and physical health services, education, catch-up classes and vocational opportunities. In 2018, we responded to the needs of more than 13,000 child survivors.

More from UNICEF

Save the Children, UNICEF and France launch new handbook to strengthen bid to end the recruitment and use of children in conflict

Visit the page

A long journey: The story of Ishmael Beah

From a child in war to renowned author, human rights activist and Goodwill Ambassador

Read the story

15 child soldiers released in South Sudan

Visit the page

Critical support for former child soldiers in South Sudan at risk from lack of funding

Visit the page

Resources

UNICEF Humanitarian Practice: COVID-19 Technical Guidance

Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Groups

Paris Principles and Commitments on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups Explanatory Note: What are the Paris Principles and Commitments?

Paris Principles and Commitments on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups: Frequently Asked Questions

Impact of Armed Conflict on Children

Paris Principles: Operational handbook

UN Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict

Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict

Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts

Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions and Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts

The Recruitment and Use of Children by Non-State Armed Groups in Contemporary Conflict Research Initiative

Reintegration of Former Child Soldiers

Girls Associated with Armed Forces and Armed Groups: Lessons Learnt and Good Practices on Prevention, Recruitment and Use, Release and Reintegration

Last updated 22 December 2021

Coercion and Intimidation of Child Soldiers to Participate in Violence

Introduction

Angola

Burma

Colombia

Liberia

Nepal

Sierra Leone

Uganda

Conclusion

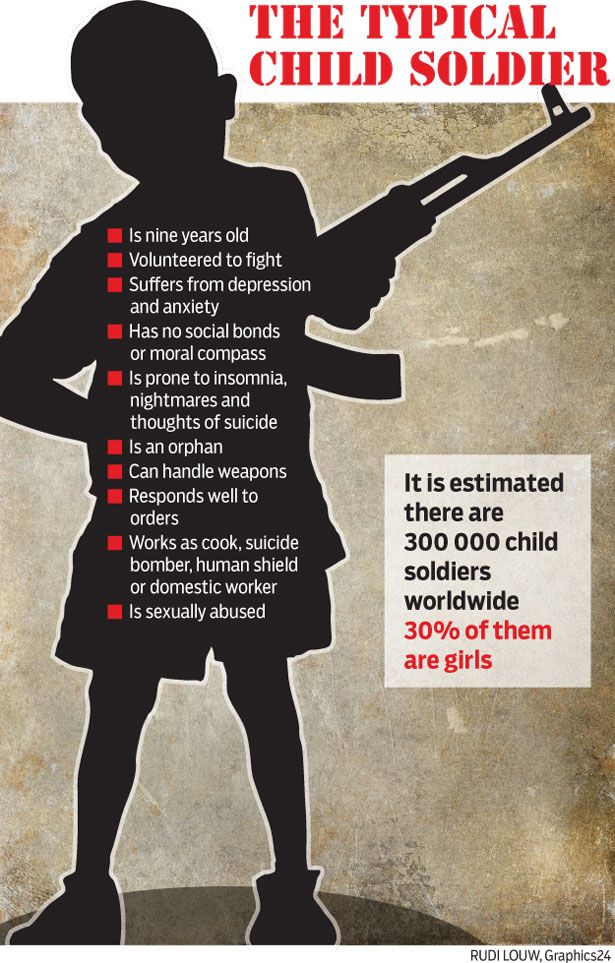

Introduction

Thousands of children under the age of 18 currently participate in armed conflicts in at least 18 countries worldwide, as part of government armies, paramilitaries, and armed opposition groups. Since 1994, Human Rights Watch has reported on the use and recruitment of child soldiers in 15 countries. Both girls and boys are used as child soldiers. They serve as porters or cooks, guards, messengers or spies. Many are pressed into combat, where they may be forced to the front lines or sent into minefields ahead of older troops. Children have also been used for suicide missions. In some conflicts, girls are raped, or given to military commanders as "wives."

Since 1994, Human Rights Watch has reported on the use and recruitment of child soldiers in 15 countries. Both girls and boys are used as child soldiers. They serve as porters or cooks, guards, messengers or spies. Many are pressed into combat, where they may be forced to the front lines or sent into minefields ahead of older troops. Children have also been used for suicide missions. In some conflicts, girls are raped, or given to military commanders as "wives."

Because children are often physically vulnerable, easily intimidated, and susceptible to psychological manipulation, they typically make obedient soldiers. As part of their training for violence, child recruits are often subject to grueling physical tasks as well as ideological indoctrination. Children accused of the slightest infractions may be subject to extreme physical punishments including beating, whipping, caning, and being chained or tied up with rope for days at a time. In some conflicts, commanders supply child soldiers with marijuana and opiates to make them "brave" and lessen their fear of combat. Furthermore, commanders may initiate child recruits by forcing them to witness or commit abuses and killings in order to desensitize them to violence. Some children are forced to take part in atrocities against their own families and neighbors to stigmatize them and ensure that they are unable to return to their communities.

Furthermore, commanders may initiate child recruits by forcing them to witness or commit abuses and killings in order to desensitize them to violence. Some children are forced to take part in atrocities against their own families and neighbors to stigmatize them and ensure that they are unable to return to their communities.

Many child soldiers are compelled to follow these orders under threat of severe punishment or death. To coerce children to participate in combat and commit atrocities against civilians, commanders not only use threats of violence against child recruits but also against their families as well as the possibility of torture and death at the hands of the enemy. Human Rights Watch investigations have also found that child recruits are often forced to physically punish and kill other soldiers, including children, accused of desertion and other crimes. Child soldiers who refuse to comply with orders may be severely beaten or threatened with execution. These practices instill fear and guilt in the children and forewarn them of their fate should they attempt to escape or fail to heed orders.

The use or threat of violence to compel child recruits to kill and torture other fighters and to commit human rights violations against civilians is geographically widespread and common to government armies, paramilitaries, and armed opposition groups. Human Rights Watch has collected testimony to this effect in its investigations in Africa, Asia and the Americas.

The following examples are drawn from reports on child soldiers produced by Human Rights Watch. Full reports are available at: https://www.hrw.org/en/topic/children039s-rights/child-soldiers.

Angola

Children recruited by the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) faced harsh discipline for infractions and especially severe penalties for attempting to escape. To deter desertion, commanders forced child recruits to watch and participate in the execution of captured escapees. Children demobilized from UNITA forces in 1996 explained that when one child who had escaped was captured, the others would have to assist in his execution even if that person were a family member.

João F. told Human Rights Watch: "If you didn't comply with orders, you would be punished, sometimes killed. Children were punished too. Myself, I was whipped twice for disobeying orders. Other children were beaten with heavy sticks."

See: Forgotten Fighters: Child Soldiers in Angola, April 2003.

Burma

Burma has recruited tens of thousands of boys into its national army, typically by force, coercion or intimidation. Boys are often told that if they refuse to join the army, they will be forced to go to jail. Deliberately cut off from contact with their families, they are treated brutally by their superiors and often prevented from fraternizing even among themselves. After training they are sent off to distant battalions, where they are further brutalized by their commanders and taught to view the local population as their enemy.

When a recruit is captured attempting to escape there is a standard punishment that seems common to most of Burma's training schools and has not changed in the last 10 years: the trainee is paraded in front of his entire training company, who are then forced to line up and take turns hitting him hard once or twice with a stick while officers or other trainees pin him down and look on.

Sai Seng described his experience of this in 2005, when he was 17:

Only one person was caught. All 249 people had to beat him on the buttocks and the back of his thighs with a green bamboo. I felt pity on my friend so I hit him lightly, and the NCO came and said, "Don't hit like that, hit like this" and hit me, and then made me hit my friend again. Three sections [150 recruits] had already beaten him by then, and he was crying. The NCO was pinning his arms down with his back to me, so I couldn't see his face, he was face down with his legs in the stocks. He was bloody because sometimes the sticks broke when they hit him. After the beating the NCOs carried him to the barracks with his legs still in the stocks, and laid him on the cement floor without a mat. He died that night. His name was Thet Naing Soe, he was 18. After that the NCOs said, "If you run away we'll do the same to you."

Sai Seng, a 16-year-old Shan farmer who was taken as a porter in mid-2001 and then forced into the army, told Human Rights Watch in 2002,

After a while the soldiers couldn't bear it anymore and they ran away.

When people ran away, if they recaptured them we students had to beat them. There were 200 people in our group, and every one of us was ordered to hit him one time with a cane stick. If we said anything they hit us. The reason is for us to know that if we run away later we will get beaten like that too. After the beating, if he couldn't stand up anymore he was just left laying on the concrete like that. Sometimes they were unconscious.

Child recruits sent to their first combat operation were often so afraid that they were unable to use their weapon or attempted to retreat. Fear of beatings or death at the hands of their commanders prevented them from escaping.

Khin Maung Than was 12 years old when he was first deployed into combat:

I was afraid that first time. The section leader ordered us to take cover and open fire. There were seven of us, and seven or ten of the enemy. I was too afraid to look, so I put my face in the ground and shot my gun up at the sky.

I was afraid their bullets would hit my head. I fired two magazines, about forty rounds. I was afraid that if I didn't fire the section leader would punish me.

Aung Zaw's commander threatened to kill him if he attempted to retreat during his first combat exposure:

I can't remember how old I was the first time in fighting. About 13. That time we walked into a Karenni ambush, and four of our soldiers died. I was afraid because I was very young so I tried to run back, but [the captain] shouted, "Don't run back! If you run back I'll shoot you myself!"

Child recruits interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported being forced to participate in human rights violations against civilians, including forced labor, beatings and summary executions. Forced to carry heavy loads of ammunition and other supplies, the civilians often have trouble keeping up with the army column. The rank and file soldiers in charge of them, afraid of the beatings and other punishments they face if they fall behind, become desperate and try to do whatever is necessary to keep the porters moving. Thein Oo often saw villagers beaten by his commanders during forced labor; "I didn't like it but I was afraid of my commander. If I protested I'd be beaten by my commander, 2nd Lieutenant Kyaw Myint Thein."

Thein Oo often saw villagers beaten by his commanders during forced labor; "I didn't like it but I was afraid of my commander. If I protested I'd be beaten by my commander, 2nd Lieutenant Kyaw Myint Thein."

Child soldiers are also compelled to take part in the destruction of villages in areas where the army is pursuing a scorched earth policy. From the time of his recruitment at age thirteen in 1995 until he fled the army in late 2001, Moe Shwe says, "I saw it twelve times. There were some Karen soldiers in the village, or if there's a battle near a village we burned the village." When asked if he actually torched houses himself, he answered, "Yes, three times. About two or three houses each time. We had to do it. We were ordered. If not they'd punch me. I felt very sorry and unhappy, because I thought that if my house were burned like this there would be a lot of problems for my family and me."

See: "My Gun Was as Tall as Me": Child Soldiers in Burma, October 2002, and Sold to Be Soldiers: The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma, October 2007.

Colombia

As part of their training, children recruited by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP) and paramilitary forces in Colombia have been asked to kill captured enemy soldiers as well as other child recruits, including friends, to prove their loyalty. Bernardo, who joined paramilitaries as a seven-year-old street child, told Human Rights Watch,

They give you a gun and you have to kill the best friend you have. They do it to see if they can trust you. If you don't kill him, your friend will be ordered to kill you. I had to do it because otherwise I would have been killed.

Seventeen-year-old Adolfo, also recruited by paramilitaries, described his initiation:

I was really scared at first. The first test they give you is to kill a man, a guerrilla. Bring me so and so, they say, so that he can learn. And they bring you and tell you to kill the man. If you don't kill him, they will kill you. They used to bring guerrillas captured in Caquetá to the camp, and tie them up by the hands and legs and a man would come up with a chainsaw, and slice them piece by piece.

Everybody could watch. I must have seen it ten times. It's part of the training.

Fellow combatants who desert or are accused of infractions are treated harshly. Child recruits are expected to watch and often to participate in such punishments. Mauricio had been in the FARC-EP for four years and had won a command without killing anybody. Then he was sent to find and bring back a deserter who had been spotted in town by the militia:

We went to his house and picked up him, then brought him back to the camp. There, they held a war council. He had a defender, but everyone knew what the verdict was going to be. It was automatic. There was no real possibility that he would escape shooting. His crimes were "theft from the movement and desertion," the most serious crimes of all. In the war council, no one voted to save him. After the council, we went and dug his grave. Then we brought him to the side of the grave. He closed his eyes, and I shot him in the head.

I had never executed anyone before, but this time I had to do it. If you don't do it, they'll kill you.

Children recruited by paramilitary and guerilla groups are trained to treat their enemy's fighters and sympathizers without mercy. As a result children witness and participate in grave violations of human rights including torture and killings. Commanders often use these instances to initiate and implicate children in violence. Many child soldiers expressed fear of being executed if they did not comply with orders.

At 13, Laidy, recruited by paramilitary forces, shot a policeman in the head. "I felt happy afterwards. I wanted to please the commanders. Because if you say no, they'll kill you."

Separated from their families and believing they will never be released or escape, many child recruits believe they have no choice but to prove their loyalty to their commanders and fellow combatants by participating in killings and other grave abuses.

See: "You'll Learn Not To Cry": Child Combatants in Colombia, September 2003.

Liberia

Many children were recruited into armed groups and government forces during the conflict in Liberia. Some children saw their parents killed and believed they had no options but to join armed groups for safety or survival. Some were forcibly recruited. Some joined because of starvation so they would be fed by a warring faction. Human Rights Watch received testimony that both rebel and government affiliated forces including the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), United Liberian Movement for Democracy in Liberia (ULIMO), Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL), and Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) threatened, beat, and tortured children to force them to witness and participate in atrocities against combatants and civilians.

Child soldiers and their counselors told Human Rights Watch that children were frequently severely mistreated by the warring factions. KN, a 13 year old recruited by the NPFL in 1993, told Human Rights Watch:

They treated me very bad.

They didn't take care of me. They beat me with a cartridge belt if I put my gun down.

The treatment of child soldiers was described by a social worker as follows:

The kids got very harsh treatment. First of all, boys from both factions have told us that there were initiation procedures when they joined in which they were forced to kill or rape someone or perform some other atrocity, like throwing someone down a well, or into a river. This was supposed to demonstrate that they were brave enough to be soldiers. Anyway, they were told that they would be shot if they didn't do it.

Then many of them have told us that they were beaten if they spoke up and were threatened with torture as punishment for doing something they weren't supposed to do. It was not just NPFL and ULIMO that beat the kids; ECOMOG and the AFL beat kids severely, too, sometimes causing head or other injuries.

A counselor working with child soldiers also discussed their treatment by commanders:

The factions use a kind of torture called "tabay," in which a person's elbows are tied together behind his back, and the rope is pulled tighter and tighter until his rib cage separates.

This was a form of punishment that was used with child soldiers, too.

Kids have told us that they were actually forced to witness the execution of members of their family or their friends. If they screamed or cried, they were killed. Boys have told us of being lined up to watch executions and being forced to applaud. If you didn't applaud, you could be next.

One child-care worker reported:

Some children were the most vicious, brutal fighters of all. I once saw a nine-year-old kill someone at a check-point. Children learn by imitation; they saw killings and then when their commanding officers ordered them to kill, they did. Some of the kids killed out of fear; they were told they would be killed if they didn't carry out orders to kill.

In 1990, 15-year-old FW was "arrested" by INPFL soldiers at a checkpoint and asked to join the group, but he refused. He said he was then told to kill a captured AFL soldier who was being beaten. He refused. The INPFL fighters told him that he would be killed if he did not kill the soldier. At knifepoint, he carried out the order.

He refused. The INPFL fighters told him that he would be killed if he did not kill the soldier. At knifepoint, he carried out the order.

See: Easy Prey: Child Soldiers in Liberia, September 1994.

Nepal

To discourage child recruits from surrendering, Maoist commanders informed children that they will be tortured if captured by the army. Child soldiers also fear violence to themselves or their families if they attempt to surrender.

Eighteen-year-old Padma told Human Rights Watch that her superiors tried to discourage her from ever surrendering, warning her about the treatment she would receive from the Nepali army:

The commanders told us never to surrender. They told us to throw the grenade that we had into the troops and run away. When I said that I wouldn't be able to do that, they said that the army would then arrest me, and if I surrender the army would torture and rape me.

When Padma and several other Maoists, including children, were followed by government forces after the battle of Tensen, the group sought shelter in a house in a village. Harried by government helicopters, their commanders first told them not to surrender and then essentially abandoned them:

Harried by government helicopters, their commanders first told them not to surrender and then essentially abandoned them:

We were staying in the house with our commanders; they went out and started firing at the helicopter, and they also told the others to come out. Then, when the second helicopter arrived, the commanders just threw their weapons in the house and left. The commanders told us to run and not to surrender, but we said we would surrender to the army. The commanders were outside of the house, still trying to convince us to run, saying, ‘You are going to surrender, we cannot let this happen-we would rather kill you.' And then they shot at the house once from a submachine gun, and ran away.

See: Children in the Ranks: The Maoists' Use of Child Soldiers in Nepal, February 2007.

Sierra Leone

During Sierra Leone's civil war, child combatants armed with pistols, rifles, and machetes actively participated in killings and massacres, severed the arms of other children, participated in rapes, and beat and humiliated elderly people. Often under the influence of drugs, they were known and feared for their impetuosity, lack of control, and brutality. Human Rights Watch documented instances in which children recruited to the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) were compelled to commit abuses under threat of death or as a result of being drugged.

Often under the influence of drugs, they were known and feared for their impetuosity, lack of control, and brutality. Human Rights Watch documented instances in which children recruited to the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) were compelled to commit abuses under threat of death or as a result of being drugged.

Abubakar, a 17 year old RUF child soldier demobilized in March 2000 was abducted outside the demobilization camp and forced to rejoin the RUF later that same year:

It was not my wish to go fight, it was because they captured me and forced me ... There was no use in arguing with them, because in the RUF if you argue with any commander they will kill you.

Abubakar and others were often forced to commit abuses. In Rogberi Junction, their commander ordered them to burn down the entire town after a counterattack on the RUF by government helicopters. He finally managed to sneak away from the RUF and return to the demobilization camp, which was evacuated to Freetown soon after.

The RUF frequently gave their fighters drugs, marijuana, and alcohol. Many witnesses believe that most of the group's atrocities were committed while fighters were under the influence of these substances.

Lynette, 16, was abducted and held by the rebels for several days during which time she was given drugs in her food, and witnessed other abductees being lined up and injected with drugs. She recounted:

From the first day they drugged us. They showed me some powder and said it was cocaine and was called brown-brown. I saw them put it in the food and after eating I felt dizzy. I felt crazy.

One day I saw a group of rebels bring out about 20 boys all abductees between 15 and 20 years old. They had them lined up under gunpoint and one by one called them forward to be injected in their arms with a needle. The boys begged them not to use needles but the rebels said it would give them power.

About 20 minutes later the boys started screaming like they were crazy and some of them even passed out.

Two of the rebels instructed the boys to scream, "I want kill, I want kill" and gave a few of them kerosene to take with them on one of their burn house raids.

See: Getting Away with Murder, Mutilation, Rape: New Testimony from Sierra Leone, July 1999, and "Sierra Leone Rebels Forcefully Recruit Child Soldiers," May 2000.

Uganda

Child abductees in the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) are forced to beat and sometimes kill civilians in looting operations, participate in the abduction of new children, and steal from and burn houses in their home regions. Children are forced to witness and to participate in the killings of other children, usually those who attempt to escape and are captured. The practice of using the children to collectively kill fosters guilt and fear among them, and sends a powerful message to the children of their potential fate if they attempt to escape. In addition, the brutal tactics used to control children make their personal rehabilitation and reintegration into their home communities more difficult.

Many children interviewed by Human Rights Watch were forced to participate in the beating or trampling of fellow abductees. Some of the children, while fearing to refuse the orders of the LRA, nevertheless spoke with difficulty about performing these killings. James K. told Human Rights Watch:

Just a few days before an air assault by UPDF [Uganda People's Defense Force] helicopter gunship, there was a group of children who escaped. Two girls, aged fourteen, were captured. They were given to the group of child abductees and we were told that we must kill them with clubs. Every one of the new recruits was made to participate. We were warned that if we ever tried to escape, we would be killed in the same manner.

Twelve-year-old Susan A. reported being forced with a group of other girls to kill an adult escapee:

I saw many dead bodies in the bush. One day, a man tried to escape. After he was caught, four of us girls were forced to beat him to death.

When we started crying, the LRA told us that if we cried, we would also be killed. The man pleaded with us, ‘You forgive me, you sympathize with me, please let me live.' But the commander told him, ‘If you speak again, we will cut you to pieces with a machete.'

Susan, a 16 year old abducted by the LRA, was threatened with a gun when she refused to participate in the killing of a fellow abductee, a boy from her village:

One boy tried to escape, but he was caught. They made him eat a mouthful of red pepper, and five people were beating him. His hands were tied, and then they made us, the other new captives, kill him with a stick. I felt sick. I knew this boy from before. We were from the same village. I refused to kill him and they told me they would shoot me. They pointed a gun at me, so I had to do it. The boy was asking me, "Why are you doing this?" I said I had no choice. After we killed him, they made us smear his blood on our arms. I felt dizzy.

There was another dead body nearby, and I could smell the body. I felt so sick. They said we had to do this so we would not fear death and so we would not try to escape.

I feel so bad about the things that I did ... It disturbs me so much--that I inflicted death on other people ... When I go home I must do some traditional rites because I have killed. I must perform these rites and cleanse myself. I still dream about the boy from my village who I killed. I see him in my dreams, and he is talking to me and saying I killed him for nothing, and I am crying.

In combat operations many child soldiers who expressed fear or reservation were beaten by their commanders into pressing ahead to the front lines. Even children without weapons were sent forward to engage the enemy. Former child recruits witnessed large numbers of children killed in such actions. Timothy, a 14 year old captured by the LRA, recounted his experience in Sudan:

I was good at shooting.

I went for several battles in Sudan. The soldiers on the other side would be squatting, but we would stand in a straight line. The commanders were behind us. They would tell us to run straight into gunfire. The commanders would stay behind and would beat those of us who would not run forward. You would just run forward shooting your gun. I don't know if I actually killed any people, because you really can't tell if you're shooting people or not. I might have killed people in the course of the fighting . . . . I remember the first time I was in the front line. The other side started firing, and the commander ordered us to run towards the bullets. I panicked. I saw others falling down dead around me. The commanders were beating us for not running, for trying to crouch down. They said if we fall down, we would be shot and killed by the soldiers.

In Sudan we were fighting the Dinkas, and other Sudanese civilians. I don't know why we were fighting them. We were just ordered to fight.

Charles, a 15 year old abducted by the LRA reported,

After training in Sudan, the rebels sent me back to Uganda.

I was to be part of a group that would attack trading centers in Kitgum and abduct new children. I was well-armed, a soldier already. As we were returning, we were attacked by government soldiers. The frontline was somewhere ahead of where I was, and the commander said, "Run, run to the front-line!" It didn't matter whether you had a gun or not. If you did not run they would beat you with sticks. Many children without guns had to run to the front.

You are not allowed to appear to be thinking too much. If you had a gun, you had to be firing all the time or you would be killed. And you were not allowed to take cover. The order from the Holy Spirit was not to take cover. You must have no fear, and stand up as you run into fire. This was because they said you would be protected by the Holy Spirit if you stood tall and had no fear. But if you took cover, the Holy Spirit would be angry and you would be shot dead by all the bullets.

So many, so many were killed.

See: The Scars of Death: Children Abducted by the Lord's Resistance Army in Uganda, September 1997, and Stolen Children: Abduction and Recruitment in Northern Uganda, March 2003.

Conclusion

For many child soldiers, carrying out violent acts against other fighters or civilians is an inescapable part of their experience. Even though some children initially "volunteer" to serve as soldiers, they quickly learn that the penalties for leaving their group are severe, and may include death. They realize that they are at the mercy of their commanders, and do what they believe they must in order to survive. Children who engage in violence often believe they have no choice but to follow orders, particularly if they have witnessed other children killed for disobedience, or have been beaten or threatened themselves.

For children who eventually leave these armed forces and groups, rehabilitation and reintegration into their home communities can be extremely difficult. They may be stigmatized as a former child soldier, be rejected by family and communities members for acts that they have committed as a fighter, and in some instances, be subject to reprisals for their actions or group affiliation. They often have no marketable job skills, may be vulnerable to re-recruitment as a child soldier, or turn to a life of crime. Sustained support is essential to help them successfully reintegrate into their home communities. This includes access to educational and vocational training programs, reuniting the child with family or extended family members where possible, and in some cases, participating in restorative justice processes to help the child acknowledge their actions and gain reacceptance by the community.

They often have no marketable job skills, may be vulnerable to re-recruitment as a child soldier, or turn to a life of crime. Sustained support is essential to help them successfully reintegrate into their home communities. This includes access to educational and vocational training programs, reuniting the child with family or extended family members where possible, and in some cases, participating in restorative justice processes to help the child acknowledge their actions and gain reacceptance by the community.

Human Rights Topics for Upper Primary and Lower and Upper Secondary Schools - The ABC of Teaching Human Rights in Schools

Chapter III

Human Rights Topics for Senior Primary Schools and junior and senior secondary schools

War, peace and human rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights emerged as a reaction to the horrific events of World War II. The preamble states that “disregard for and contempt for human rights have led to barbaric acts that outrage the conscience of mankind” and emphasizes that “recognition of the inherent dignity and equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the basis of freedom, justice and world peace. "

"

Peace, disarmament, development and human rights are interrelated issues. An integrated approach to the teaching of human rights is to awaken the desire for peace and disarmament, as well as for development and respect for the environment.

Information about the arms race and attempts to contain it would be appropriate here. Since the end of World War II, there have been 150 conflicts, which shows that armed violence continues in the world. Depending on the level of the class, it may be appropriate to conduct a study of international political and economic issues, which will enable students to understand why keeping the peace is such a hard thing. Development imbalances and environmental problems persist; not only are they sharp in nature, but they themselves can sow the seeds of war. A war - especially a nuclear war - even a small one, can lead to an ecological catastrophe.

a) World

Choose a clear day if possible. Ask the question: “Why do you think peace is so important in our world with its local conflicts and the threat of war?”

You can take the class for a walk to some pleasant place. Everyone should silently lie on their back and close their eyes for about three minutes. Gather the class, discuss the fundamental value of the world. How would they define the concept of "world"? What is the relationship between peace and human rights? (UDHR articles 1, 3, 28; CRC articles 3, 6)

Everyone should silently lie on their back and close their eyes for about three minutes. Gather the class, discuss the fundamental value of the world. How would they define the concept of "world"? What is the relationship between peace and human rights? (UDHR articles 1, 3, 28; CRC articles 3, 6)

b) Summit

Role-play a high-level discussion between leaders of all countries on an important issue, such as reducing the use of anti-personnel mines or protecting children from hazardous work. Organize a class discussion on this issue in which the groups stand together as the respective countries, with some groups trying to ban the practice and others opposing such a ban. Compare, where possible, with the discussions that led to the conclusion of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (1997) or the Convention on the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor (Convention No. 182 of the International Labor Organization, 1999). Emphasize that different countries and peoples can work together to enable us all to live in peace together. (See “Mimicking the Model UN” section below as an alternative.) (UDHR article 28; CRC articles 3, 4, 6)

(See “Mimicking the Model UN” section below as an alternative.) (UDHR article 28; CRC articles 3, 4, 6)

c) Packing our bags

who flee their home countries because of “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” (Article 1.A.2 of Refugee Convention 1951 years old).

Read the following script:

“You are a teacher at _____. Your partner disappeared and was later found murdered. Your name appears in a newspaper article listing suspected subversives. Later, you receive a letter threatening to kill you because you are allegedly involved in some kind of political activity. You make the decision to run. Pack your bag. You can only take five categories of items with you (e.g. toiletries, clothes, photographs) and only what you can carry in one bag yourself. You have five minutes to make a decision. Remember that you will never be able to return to the country where you lived.

”

Ask a few students to read out their lists. If they forget to mention a newspaper article or threatening letter (the only concrete evidence for authorities in a new country they have fled to because of “well-founded fear of being persecuted”), say, “Asylum denied.” After several such examples, explain the definition of a refugee and the importance of proof of persecution. Discuss the experience of making emotional decisions under stress.

Consider the issue of refugees in today's world:

- Where are most refugees located?

- Where did they run from and for what reason?

- Who is responsible for resolving their issues?

d) Child soldiers

In some parts of the world, boys and girls, even under the age of 14, are recruited into the military. Often, these children are abducted and forced into this dangerous work, which involves the possibility of death, injury and separation from their home environment and society as a whole. The new Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child prohibits the involvement of children in such armed conflicts (2000), as does the International Labor Organization Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labor (1999).

The new Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child prohibits the involvement of children in such armed conflicts (2000), as does the International Labor Organization Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labor (1999).

Discuss:

- Why do military forces tend to use children in times of war?

- Why are the human rights of these children being violated? Cite specific articles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- How can being in the military as a soldier affect girls and boys differently?

- If a child manages to survive and return to his or her community of origin, what are the first challenges they may face? In the short term? In the long run?

Students can do additional work or explore this issue in more detail as follows:

- learn about child soldiers in different parts of the world;

- Find out which organizations are working in the field of rehabilitation of former child soldiers and offer them your help;

- write letters calling on the government to ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which prohibits the involvement of children in armed conflict.

(UDHR articles 3, 4, 5; CRC articles 3, 6, 9, 11, 32, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39)

e) Humanitarian law

Parallel to international human rights law complementary legal system of international humanitarian law. The so-called “rules of war” set out in the Geneva Conventions of 1949 set standards for the protection of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked, as well as civilians living in areas of war or under enemy occupation. Armed forces in many countries train their personnel on the provisions of the Geneva Conventions, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) plays a leading role worldwide in educating the public in international humanitarian law, as well as providing humanitarian assistance during armed conflicts.

However, the realities of modern warfare have changed. Combatants are no longer just the armies of warring countries (international armed conflict), but also rebel armies, terrorists or competing political or ethnic groups (internal armed conflict). Moreover, most of the victims are no longer only military personnel, but also civilians, especially women, children and the elderly.

Moreover, most of the victims are no longer only military personnel, but also civilians, especially women, children and the elderly.

The human rights system and international humanitarian law complement each other in many ways. For example, both have a special focus on children recruited into the armed forces and recognize the need for special protection for children caught up in armed conflict.

Find out more about how human rights and humanitarian law apply in times of war:

- Learn about the history of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and the Geneva Conventions. How have the original Geneva Conventions of 1949 been adapted to the conditions of modern warfare?

- Find out about the humanitarian work of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) for war victims. Compare the seven basic principles of the ICRC (humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, voluntariness, unity and universality) with those of the Universal Declaration.

- Compare the provisions relating to children at war contained in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 (Geneva Convention Relating to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War) and the Additional Protocols of 1977. Why are both international human rights law and international humanitarian law necessary to protect children?

- Compare the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict and article 77 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Convention on the recruitment of children. Which of the two documents is more efficient? Are they both needed? Do you agree that a person who has reached the age of 15 is mature enough to serve in the armed forces?

- Review new reports of armed conflict in the world today. Are the Geneva Conventions respected in such conflicts? Are the provisions of the UDHR respected?

(UDHR articles 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 21; CRC articles 3, 6, 22, 30, 38, 39)

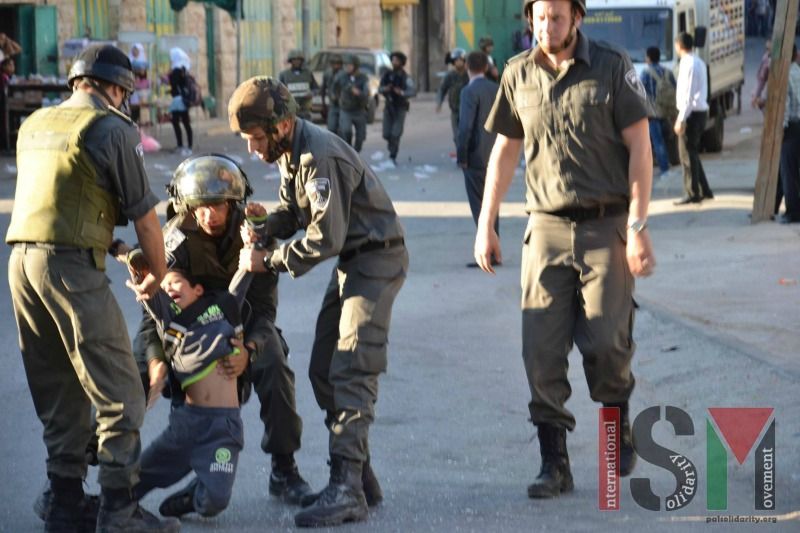

UNICEF: belligerents around the world grossly violate children's rights

From Afghanistan to Yemen, from Syria to northern Ethiopia, thousands of children are paying the price for adults' decisions to take up arms. Last week in Myanmar, 35 people died in violence, four of them children. This is one of the recent examples of how conflict robs children of childhood and even life.

Last week in Myanmar, 35 people died in violence, four of them children. This is one of the recent examples of how conflict robs children of childhood and even life.

“Year after year, parties to conflict show a complete disregard for the rights and well-being of children,” said UNICEF chief Henrietta Fore. “Because of such callousness, children suffer and die. Everything must be done to protect them.”

Year after year, parties to the conflict show a complete disregard for the rights and well-being of children

The UN does not yet have complete data for 2021, but in 2020, according to confirmed information, 26,425 gross violations of children's rights were committed. In the first quarter of this year, according to preliminary data, the number of such cases slightly decreased, but the number of kidnappings of children and cases of sexual abuse of minors continued to grow at an alarming rate - such crimes were committed, respectively, by 50 and 10 percent more than in the same period 2020 of the year.

Abductions occurred most frequently in Somalia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The DRC, Somalia and the Central African Republic (CAR) lead in cases of sexual violence against children.

This year, as UNICEF recalls, marks 25 years since the publication of a landmark report on the effects of war on children. It was this document that prompted the international community to take action to protect the young inhabitants of the planet caught in conflict.

See also:

Children in conflict countries continue to be killed, maimed and recruited as soldiers countries in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Latin America. These are only cases that the UN has been able to confirm - the real figures can be much higher.

The highest number of children affected by hostilities was found in Afghanistan - 28.5 thousand. This is 27 percent of the total number of such violations worldwide. Countries in the Middle East and North Africa lead in the number of attacks on schools and hospitals.

In October, UNICEF reported horrifying data from war-torn Yemen: 10,000 children have been killed or maimed there since March 2015 – four children every day. Headlines from Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Colombia, Libya, Mozambique and the Philippines may not be as catchy, but even there children suffer daily.

Despite all the measures taken, girls and boys continue to suffer unbearable suffering during the conflict and long after it. In 2020, for example, as a result of triggered explosive devices, including those left after the war, more than 3.9thousand children. Often one violation leads to another: for example, in 37 per cent of cases, children were abducted to be forcibly put under arms. This practice is especially rooted in Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic.

Children living in war can only be safe if the parties to the conflict take concrete action to protect them

On the last day of the outgoing year, UNICEF is calling on all parties to the conflict to formally commit themselves to take concrete action to protect the rights of children caught in hostilities.