How does child labour affect society

Child labour | UNICEF

Programme

Nearly 1 in 10 children are subjected to child labour worldwide, with some forced into hazardous work through trafficking.

UNICEF/UN0263808/Lister

Economic hardship exacts a toll on millions of families worldwide – and in some places, it comes at the price of a child’s safety. Roughly 160 million children were subjected to child labour at the beginning of 2020, with 9 million additional children at risk due to the impact of COVID-19.

This accounts for nearly 1 in 10 children worldwide. Almost half of them are in hazardous work that directly endangers their health and moral development.

Children may be driven into work for various reasons. Most often, child labour occurs when families face financial challenges or uncertainty – whether due to poverty, sudden illness of a caregiver, or job loss of a primary wage earner.

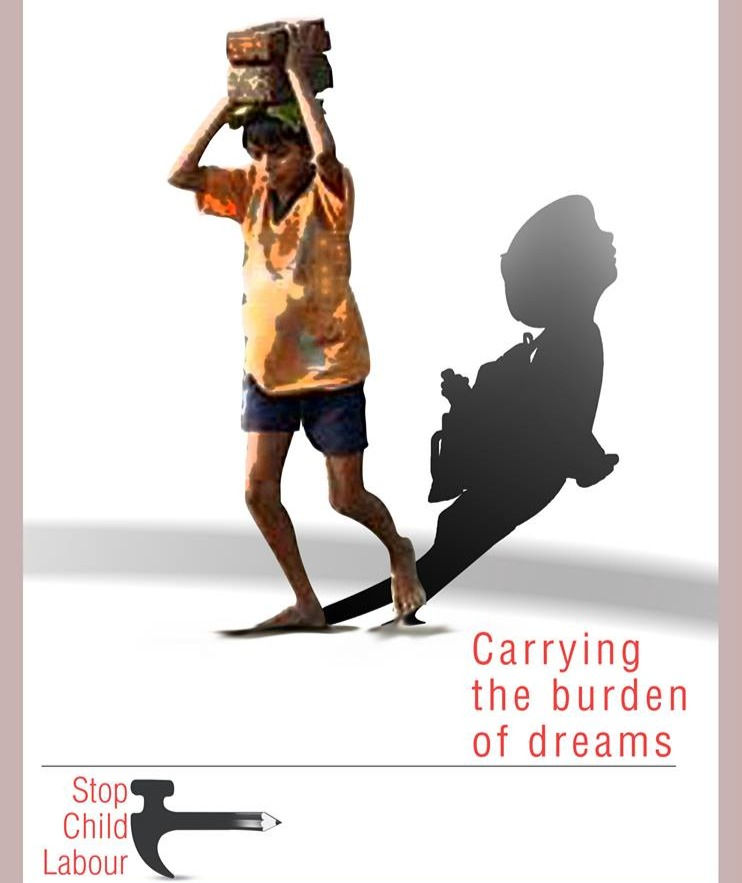

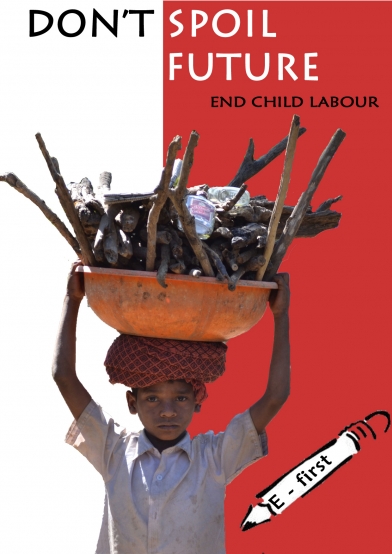

The consequences are staggering. Child labour can result in extreme bodily and mental harm, and even death. It can lead to slavery and sexual or economic exploitation. And in nearly every case, it cuts children off from schooling and health care, restricting their fundamental rights and threatening their futures.

Migrant and refugee children – many of whom have been uprooted by conflict, disaster or poverty – also risk being forced into work and even trafficked, especially if they are migrating alone or taking irregular routes with their families.

Trafficked children are often subjected to violence, abuse and other human rights violations. And some may be forced to break the law. For girls, the threat of sexual exploitation looms large, while boys may be exploited by armed forces or groups.

Children on the move risk being forced into work or even trafficked – subjected to violence, abuse and other human rights violations.

Whatever the cause, child labour compounds social inequality and discrimination, and robs girls and boys of their childhood. Unlike activities that help children develop, such as contributing to light housework or taking on a job during school holidays, child labour limits access to education and harms a child’s physical, mental and social growth. Especially for girls, the “triple burden” of school, work and household chores heightens their risk of falling behind, making them even more vulnerable to poverty and exclusion.

Unlike activities that help children develop, such as contributing to light housework or taking on a job during school holidays, child labour limits access to education and harms a child’s physical, mental and social growth. Especially for girls, the “triple burden” of school, work and household chores heightens their risk of falling behind, making them even more vulnerable to poverty and exclusion.

Key facts

- The number of children in child labour has risen to 160 million worldwide – an increase of 8.4 million children in the last four years – with 9 million additional children at risk due to the impact of COVID-19.

- Progress to end child labour has stalled for the first time in 20 years, reversing the previous downward trend that saw child labour fall by 94 million between 2000 and 2016.

- The incidence of hazardous work in countries affected by armed conflict is 50% higher than the global average.

- 30 million children live outside their country of birth, increasing their risk of being trafficked for sexual exploitation and other work.

UNICEF’s response

UNICEF/UNI281125/Herwig Children largely from the ethnic Dom community learn in a UNICEF-supported centre in Jordan, in 2019. With many of their families living in poverty, these children become especially vulnerable to negative coping mechanisms, like working on the street. Centres play a key role in identifying children who face challenges and helping them to enroll in formal and non-formal education.

UNICEF works to prevent and respond to child labour, especially by strengthening the social service workforce. Social service workers play a key role in recognizing, preventing and managing risks that can lead to child labour. Our efforts develop and support the workforce to identify and respond to potential situations of child labour through case management and social protection services, including early identification, registration and interim rehabilitation and referral services.

We also focus on strengthening parenting and community education initiatives to address harmful social norms that perpetuate child labour, while partnering with national and local governments to prevent violence, exploitation and abuse.

With the International Labour Organization (ILO), we help to collect data that make child labour visible to decision makers. These efforts complement our work to strengthen birth registration systems, ensuring that all children possess birth certificates that prove they are under the legal age to work.

Children removed from labour must also be safely returned to school or training. UNICEF supports increased access to quality education and provides comprehensive social services to keep children protected and with their families.

To address child trafficking, we work with United Nations partners and the European Union on initiatives that reach 13 countries across Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America.

More from UNICEF

COVID-19 and child labour

A time of crisis, a time to act

See the full report

A second chance: out of juvenile detention and in school

How virtual courts can create a more child-friendly justice system

Read the story

Mobile teams provide support to traumatized families

Child protection specialists in Ukraine such as Olga are helping fleeing mothers and their children cope with trauma and an uncertain future

See the story

Trying to make sense of a senseless war

UNICEF is supporting families devastated by war in Ukraine. Spokesperson James Elder reflects on what he has seen so far

Spokesperson James Elder reflects on what he has seen so far

Read the story

Resources

Child Labour - Humanium

In the last decade, child labour has decreased by 38%; however, 152 million children are still affected and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation. Child labour reaches many different corners across the world, often occurring in various sectors that can have detrimental educational, health and psychological impacts on children’s well-being. There are various drivers of child labour such as poverty, armed conflict, inadequate laws and regulations, social inequality, discrimination and ingrained cultural traditions to name a few.

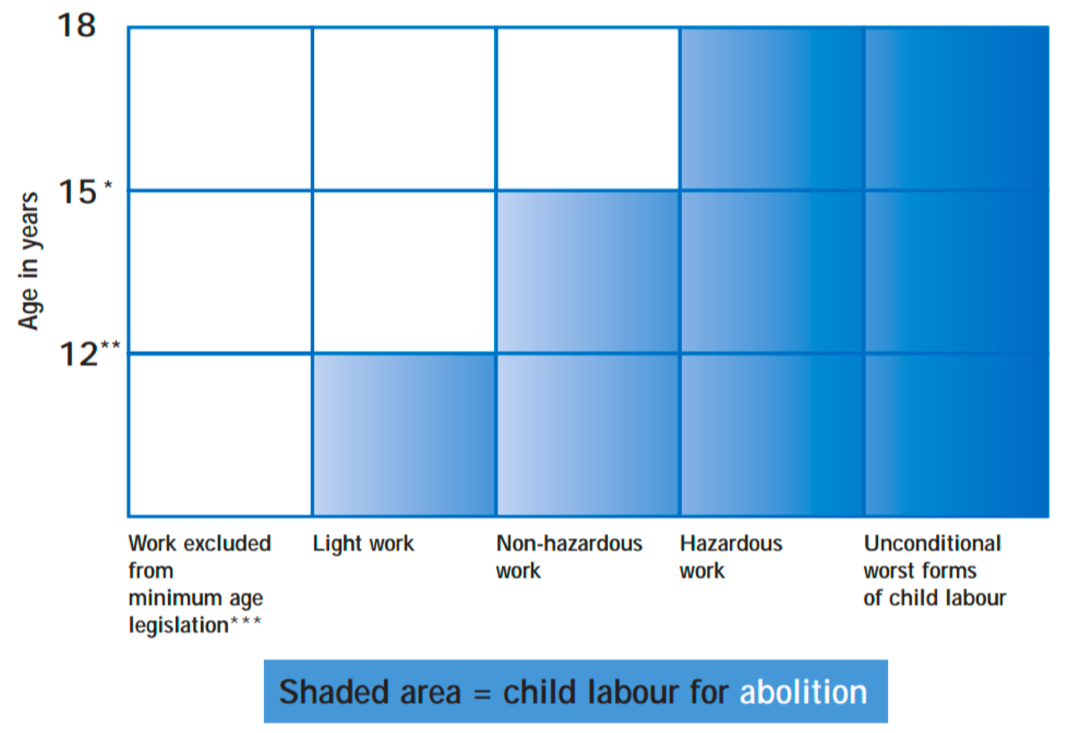

Defining child labourThe International Labour Organization (ILO) defines child labour as “work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children; and/or interferes with their schooling by: depriving them of the opportunity to attend school; obliging them to leave school prematurely; or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work” (ILO, n. d).

d).

Not all forms of work undertaken by children are considered to be child labour. This varies from country to country and depends on the child’s age, the type of work performed, the number of hours put into work, the conditions they work under and whether it interferes with their schooling. There are activities that children can engage in – such as helping their family in the house, or assisting in a family business to earn an allowance during the school holidays – that can be positive for their development and provide children with skills and experience in order to prepare them for adulthood (ILO).

Defining the ´worst forms of child labour´Under Article 3 of ILO Convention No. 182, the worst forms of child labour are defined as (ILO, 1999):

- all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict;

- the use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution, for the production of pornography or for pornographic performances;

- the use, procuring or offering of a child for illicit activities, in particular for the production and trafficking of drugs as defined in the relevant international treaties;

- work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.

The worst forms of child labour include (ILO):

- Child trafficking

- Sexual exploitation (which includes pornography and prostitution)

- Drug trafficking

- Debt bondage (also referred to as bonded labour)

- Slavery

- Forced labour

- Organized child begging

Hazardous child labour is defined under Article 3(d) of ILO Convention No. 182 as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children” (ILO). Child labour is considered hazardous when a child is working in an unhealthy or dangerous environment where they are at risk of falling ill, psychological and physical injury and in some cases, death (ILO).

Hazardous child labour is the largest category of child labour; it is estimated that approximately 73 million children are working in dangerous environments which include the mining, agriculture, manufacturing and construction sector, including work undertaken in bars, nightclubs, restaurants, markets and domestic services. Hazardous working conditions can cause lifelong illnesses that may not develop until later into adulthood (ILO).

Hazardous working conditions can cause lifelong illnesses that may not develop until later into adulthood (ILO).

Defining ´forced´ child labour

Under international law, ´forced´ labour is defined as “work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty for its non-performance and for which the worker does not offer himself voluntarily” (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019).

This can take two forms: (1) children are forced into labour by their parents/caregivers and their parents are aware of their working conditions; (2) children are forced into labour as a result of trafficking, coercion or deceptive recruitment. In relation to the latter category, these children may have migrated alone or were victims of human trafficking, leaving their parents unaware of their working conditions (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019).

There are three main categories of forced labour (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019):

- Exploitation – which includes slavery, slavery-like practices, forced domestic labour and bonded labour.

- Commercial sexual exploitation

- State-imposed forced labour

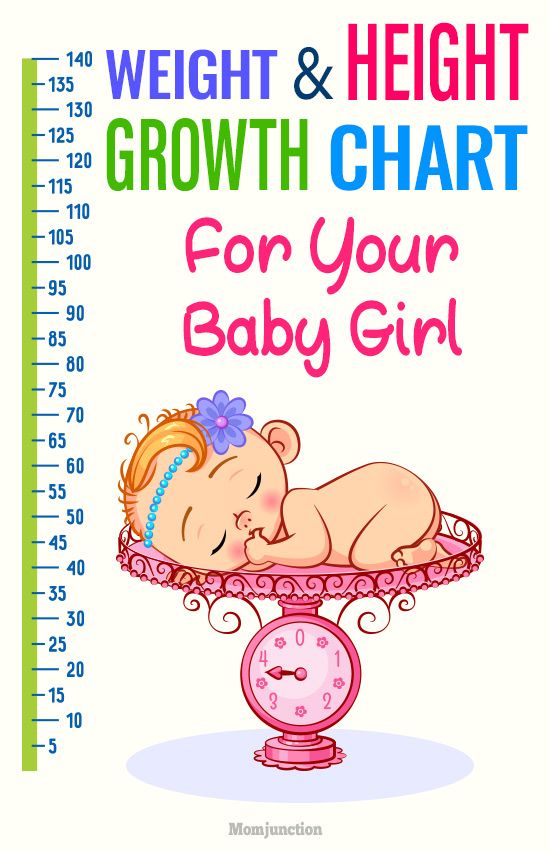

The global estimates of child labour as reported by the ILO at the beginning of 2020 were 160 million children – 97 million boys and 63 million girls engaged in child labour. Out of the 160 million children, 79 million children were engaged in hazardous work (ILO, 2020).

According to an ILO report from 2019, approximately 9 in 10 children living in Africa, Asia and the Pacific are involved in child labour. Africa is the highest rank continent, where 1 in 5 children are involved in child labour (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019).

Globally, child labour progress remains uneven. Across Africa, 72 million children are engaged in child labour and 62 million across Asia and the Pacific. 70% of children engaged in child labour globally work in the agricultural sector, predominantly in livestock herding and subsistence and commercial farming (ILO, 2021).

Despite laws and regulations protecting children from child labour, it still exists. Globally, there are numerous reasons children are pushed into work, with poverty being the greatest driving force. The main causes of child labour include:

1. Poverty and unemployment

Children need to support their families and their survival is dependent on them working. This vulnerability is taken advantage of by criminal gangs or traffickers.

2. Inadequate or weak national educational systems

Inadequate or weak national educational systems play a significant role in child labour. Communities that have inadequate educational facilities, including a lack of teachers and resources, create an unstable environment in which children do not have access education, which in turn pushes them towards child labour. Some families are unable to afford school fees, pushing them towards child labour as a more lucrative use of children’s time. Some cultures place less emphasis on girls going to school and prefer that girls are prepared to carry out household tasks (ILO).

Some cultures place less emphasis on girls going to school and prefer that girls are prepared to carry out household tasks (ILO).

3. Ingrained cultural traditions and attitudes surrounding child labour

Various cultural norms and traditions around the world tacitly encourage child labour by promoting the importance of work to a child’s development. For example, certain cultures believe that working is important for character and skill development, regardless of the effects this might have on a child’s realization of their human rights. Children are expected to follow in their parents’ footsteps and learn a particular trade in order to support their families.

Other traditions encourage children to work to pay off debts borne from social occasions and religious events. These widespread and varied manifestations of bonded labour take advantage of children’s vulnerable position within wider societies and cultural expectations. In this way, children are often framed as family supporters, rather than dependents.

4. Violation of existing laws and regulations on child labour

5. Inadequate enforcement of laws and regulations

6. Civil or political unrest or natural disasters

Child labour in different sectorsChild labour is prevalent in various sectors including:

1. Agriculture sector

Traditional societal attitudes towards children’s participation in agriculture, lack of agricultural technology, the high costs of adult labour and poverty are some of the main drivers of child labour in the agriculture sector. This sector is one of the most dangerous for children in terms of occupational diseases, non-fatal accidents and work-related fatalities (ILO). Not all child participation in the agricultural activity is considered child labour. Tasks which are low-risk, age-appropriate and do not interfere with a child’s time (education or leisure) fail to meet the child labour threshold. These activities must be non-hazardous and can often benefit families and communities by providing children with vital social and technical skills as well as enhancing local food security (ILO).

The sub-sectors that exist within the agriculture industry include (ILO):

- Fishing

- Livestock production

- Farming

- Forestry

2. Domestic work also referred to as household work

Domestic work can be defined as instances in which a child under the age of 18 years works within the home of their employer to carry out household chores. Whilst the cultural norm is for girls to work inside the house, boys are more likely to work outside the house (i.e. looking after livestock or gardening). Child domestic workers sometimes live in the home of their employers and may or may not get paid for their work (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019).

3. Factory work, predominantly in the garment and textile sector

In countries such as Zimbabwe, Indonesia, India, Argentina, Brazil and Malawi, factory child labour is prevalent within the tobacco industries (World Vision). More commonly, child labour in factories often relates to the garment industry and is especially prevalent in Asian countries such as Cambodia and Bangladesh. The rise in fast fashion has pushed companies to find cheaper sources of labour, children. Children work at all stages of the supply-chain production from cotton picking, harvesting, yarn spinning and factory work. This is prevalent in countries such as Egypt, Pakistan, China, Thailand, India, Bangladesh and Uzbekistan (Moulds).

The rise in fast fashion has pushed companies to find cheaper sources of labour, children. Children work at all stages of the supply-chain production from cotton picking, harvesting, yarn spinning and factory work. This is prevalent in countries such as Egypt, Pakistan, China, Thailand, India, Bangladesh and Uzbekistan (Moulds).

4. Industry and manufacturing (which includes working in mining, quarrying and construction)

Child labour in mines and quarries is prevalent in countries such as Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Niger, Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Zambia and Zimbabwe (Child Labour Platform & ILO, 2019).

The sub-sectors that exist within the mining industry include (ILO):

- Gold mining

- Salt mining

- Stone quarrying

- Artisanal mining

Child labour can have a range of both mental and physical health effects on a child that often continue into adulthood, these vary and include long-term health issues due to abuse, injuries, malnutrition, exhaustion, psychological harm or exposure to chemicals, among others. The mental and physical effects vary depending on the sector that children are working in (Dubay, 2021).

The mental and physical effects vary depending on the sector that children are working in (Dubay, 2021).

- In agriculture, children are often exposed to working with hazardous toxic fertilizers and pesticides, as well as heavy and dangerous tools or blades (Dubay, 2021).

- In domestic work, children face the risk of being abused by their employers, working excessively long hours or being isolated from their friends and family (Dubay, 2021).

- In construction, children face the risk of injury from working with dangerous and heavy loads and lack adequate personal protective equipment (Dubay, 2021).

- In mining, children are exposed to working with explosives, poisonous chemicals and face the risk of being placed in dangerous environments such as mines which are regularly the source of collapses that can lead to serious injury or death (Dubay, 2021).

- In manufacturing, children are exposed to unhealthy toxins, hazardous chemicals and poor health and safety working regulations (Dubay, 2021).

The involvement of boys in child labour is much higher than girls, with approximately 11.2% boys in child labour compared to 7.8% of girls. According to the most recent ILO-UNICEF 2020 report on child labour, it is estimated that there 89.3 million children engaged in child labour between the ages of 5 – 11 years old, 35.6 million between the ages of 12 – 14 and 35 million between the ages of 15 – 17 years (ILO, 2020). This gender gap increases with age as girls are more likely to be involved in unpaid and under-reported domestic child labour. In countries such as Congo, Yemen, Nepal, Peru, Mozambique, Chad and Somalia more girls are involved in child labour than boys (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019).

It is worth noting that statistics estimating the prevalence of girls and boys in child labour across the globe are subject to a few limitations. Primarily, reliable data sources on child participation in work are limited. Further, the definition upon which these estimates are typically based does not include work within children’s homes, despite the fact that girls shoulder a disproportionate burden of household labour in many societies. Recent research by the ILO attempting to include this overlooked portion of child labour purports that involvement in household chores for more than 21 hours a week is considered child labour. Once this fact is taken into account, the global gender gap in child labour prevalence is reduced by almost half (ILO).

Further, the definition upon which these estimates are typically based does not include work within children’s homes, despite the fact that girls shoulder a disproportionate burden of household labour in many societies. Recent research by the ILO attempting to include this overlooked portion of child labour purports that involvement in household chores for more than 21 hours a week is considered child labour. Once this fact is taken into account, the global gender gap in child labour prevalence is reduced by almost half (ILO).

It is more common for child labour to occur in rural areas. According to an ILO study in 2020, 122.7 million rural children were involved in child labour and 37.3 million urban children (ILO, 2020). The most common type of child labour is family-based and this accounts for 72% of all child labour. Family-based child labour is often considered hazardous with 1 in 4 children between the ages of 5-11 years engaged in work that is likely to cause harm to their health (ILO, 2020).

Poverty, being the main driver of child labour, pushes children into work which forces them to leave school early. Globally, one-third of children engaged in child labour are excluded from school and there is a strong correlation between a child’s participation in hazardous work and low school attendance (ILO, 2020).

There are several reasons why child labour affects children’s education. For example, the work may be very demanding, they are unable to access education or free schooling, an alternative does not exist or their families push them to work as in certain cultures family perceptions around work and gaining money are more important than education (ILO, 2020).

Globally, as of 2020, the percentage of children between the ages of 5 – 14 years that do not attend school include: 15.5% in Latin America and the Caribbean, 28.1% in Northern Africa and Western Asia, 28.1% Sub-Saharan Africa, 35.3% in Central and Southern Asia and 37.2% in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (ILO, 2020).

Child migration, often accompanied by family members, can lead to new child labour vulnerabilities. One of the most common drivers of child migration is the availability of seasonal work opportunities in agriculture and brick kilns for parents. Unfortunately, children frequently accompany their parents to support their work and increase the household income as for many migrant working families, this extra output is essential (van de Glind, 2010).

Child labour and COVID-19In the last two decades, significant improvements have been made in the fight to end child labour. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has threatened to undermine these developments and could potentially reverse many years of progress to eradicate child labour. Prior to the pandemic, the amount of children involved had increased by 8.9 million in just four years. This increase is attributed to rising global poverty levels and is expected to continue into 2022 (ILO, 2020).

Due to an increase in unemployment since the pandemic, families are more inclined to push their children into child labour as a coping mechanism. This is further exacerbated by school closures which leave children vulnerable and at a greater risk of child labour. Non-governmental organisations working within the African region have noted that school closures have pushed children into work as they are expected to help look after their families (ILO, 2020).

Eliminating and preventing child labourIn 2019, the International Labour Organization (ILO) in partnership with Alliance 8.7 launched the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour for 2021. The aim of 2021 is to urge governments to encourage legislative and practical actions towards the eradication of child labour and to achieve Target 8.7 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (ILO, 2021).

Although global progress has been made towards reducing child labour, the lofty target of eliminating the practice by 2025 remains unmet. The response to this persistent challenge must be unified, intersectional and backed by actionable legislation. In particular, minimum working age requirements and their enforcement are a fundamental component of child labour responses.

The response to this persistent challenge must be unified, intersectional and backed by actionable legislation. In particular, minimum working age requirements and their enforcement are a fundamental component of child labour responses.

Beyond legal and regulatory frameworks, governments and civil society must work to design and implement policies which provide families and children with alternative livelihoods, steering them away from the trappings of child labour. These initiatives must ensure that children are at the heart of all decision-making processes, and that any useful interventions are accessible to the children themselves (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019).

To upscale the fight against child labour, greater research and public awareness campaigns are required. Governments around the world must acknowledge the scale of this challenge, its evolution and the ways in which families and children are hampered by its presence (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019). Summarily, governments should work to ensure (Thevenon & Edmonds, 2019):

- The existence of minimum working age legislation and their enforcement

- The development of tools and mechanisms to monitor child labour

- Functional public awareness raising campaigns

- Support to community-led initiatives

- Greater protection for vulnerable children and families

- Affordable, fair, quality and accessible education for all

- The promotion of positive cultural and societal norms against child labour

There are various international legal instruments that recognize and respond to child labour. In particular:

In particular:

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

- The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

- ILO Convention No. 138 (on minimum age for admission to employment) (1973) Recommendation No. 146

- ILO Convention No. 182 (concerning the prohibition and immediate action for the elimination of the worst forms of child labor) (1999) Recommendation No. 190

- ILO Convention No. 189 (concerning decent work for domestic workers) (2011) Recommendation No. 201

- United Nations optional protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (2000)

- United Nations optional protocol on the involvement of children in armed conflict (2000)

- United Nations resolution ¨A world fit for children¨ A/RES/S-27/2

Written by Vanessa Cezarita Cordeiro

Last updated on 31 August 2021

For more information:

International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour

Alliance 8. 7

7

World Day Against Child Labour 12 June

References:

Child Labour Platform & International Labour Organization. (2019, May). “Child labour in mining and global supply chains.”

Council of Europe. (2013, August 20). “Child labour in Europe: a persisting challenge.”

GPE Secretariat. (2016, June 12). “Child labour hinders children’s education.”

Human Rights Watch. (2021, May 26). “COVID-19 pandemic fueling child labour.”

International Labour Organization, Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, C182, 17 June 1999.

International Labour Organization. ¨Causes¨.

International Labour Organization. ¨Hazardous child labour¨.

International Labour Organization. ¨The worst forms of child labour¨.

International Labour Organization. ¨What is child labour¨.

International Labour Organization. (2020, June 10). ¨Child labour: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward.¨

International Labour Organization. (2021, January 15). “2021: International year for the elimination of child labour.”

“2021: International year for the elimination of child labour.”

International Labour Organization. “Child labour in Africa.”

International Labour Organization. “Child labour in agriculture”.

Moulds, J. “Child labour in the fashion supply chain.”

Thevenon, O., & Edmonds, E. (2019). ¨Child labour: causes, consequences and policies to tackle it.¨ Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

UNICEF., & ILO. (2020). ¨COVID-19 and child labour: A time of crisis, a time to act.¨

UNICEF. (2021, June 9). “Child labour rises to 160 million – first increase in two decades.”

Van de Glind, H. (2010, September). “Migration and child labour exploring child migrant vulnerabilities and those of children left-behind: working paper.”

World Vision. “What are the dangers of child labour.”

World Vision. “Where does child labour happen.”

World Day Against Child Labor - Background

All children have the right to be protected from working in hazardous conditions that could harm their health and education. Figure ILO

Figure ILO

The International Labor Organization (ILO) first celebrated World Day against Child Labor in 2002.

Its purpose is to draw attention to this problem and the need for measures to eliminate it. Every year on June 12, governments, employers' and workers' organizations, civil society representatives, and millions of people around the world join forces to fight child labour.

In 2015, 17 Sustainable Development Goals were adopted and Goal 8 calls for an end to forced labor and all forms of child labor by 2030. We must work together to achieve this goal.

Child labor

One of the main objectives of the International Labor Organization when it was founded in 1919 was the abolition of child labor. Historically, the main instrument by which the ILO has sought to achieve the goal of abolishing child labor has been the adoption and enforcement of labor standards embodying the concept of a minimum age for employment or employment. In addition, since 1919, the ILO has traditionally assumed in its standard-setting activities that minimum age standards should be linked to schooling. Approved at 1973, the Minimum Age Convention (Convention No. 138) embodies this tradition by providing that the minimum age for entry into employment should not be lower than the minimum age for completion of compulsory schooling.

In addition, since 1919, the ILO has traditionally assumed in its standard-setting activities that minimum age standards should be linked to schooling. Approved at 1973, the Minimum Age Convention (Convention No. 138) embodies this tradition by providing that the minimum age for entry into employment should not be lower than the minimum age for completion of compulsory schooling.

The adoption by the ILO in 1999 of Convention No. 182 consolidated the global consensus on the abolition of child labour. Convention No. 182 provided the necessary focus without overriding the overall goal set out in Convention No. 138 of the effective abolition of child labour. Moreover, the concept of worst forms allows for prioritization and can be used as a first step towards addressing the underlying problem of child labour. This concept also helps to direct attention to the impact of work on children as well as the work they do.

Child labor, which is condemned by the international community, can be divided into three categories:

Not every activity performed by children should be classified as a type of child labor that should be eliminated. The participation of children or adolescents in work that does not affect their health and development or interfere with their schooling is generally seen as something positive. This includes activities such as helping parents around the house, helping out with the family business, or earning pocket money outside school hours and during school holidays. Such activities contribute to the development of children and the well-being of their families; they give them skills and experience and help prepare them to become productive members of society during their adult lives.

The participation of children or adolescents in work that does not affect their health and development or interfere with their schooling is generally seen as something positive. This includes activities such as helping parents around the house, helping out with the family business, or earning pocket money outside school hours and during school holidays. Such activities contribute to the development of children and the well-being of their families; they give them skills and experience and help prepare them to become productive members of society during their adult lives.

Child labor, which is condemned by the international community, can be divided into three categories:

- Indisputably the worst forms of child labor, which are internationally defined as slavery, child trafficking, bonded labor and other forms of forced labor, forced recruitment of children for use in armed conflicts, for the purposes of prostitution and pornography, as well as other illegal activities;

- labor performed by a child who has not reached the minimum age established for this type of work (in accordance with national legislation and on the basis of accepted international standards), which thus may interfere with the education of the child and his all-round development;

work that endangers the physical, mental or moral well-being and development of a child, either because of its nature or the conditions in which it is performed, which is known as "dangerous and harmful work".

- New global estimates and trends are presented in three categories: economically active children, child labor and children in hazardous and hazardous work.

The emerging global picture is thus very encouraging: child labor is declining, and the rate of decline is greater the more hazardous the work and the greater the vulnerability of children in these types of work.

One of the most effective ways to prevent the involvement of young children in hard work is to set age limits, according to which children can legally work and offer their services in the employment market. The main principles of the ILO Convention concerning the minimum age in employment and work are listed below.

- Hazardous work

Any form of work that is likely to harm the physical, mental or moral health of children, their safety or morals should not be performed by persons under 18 years of age. - Basic minimum age

The minimum age for employment must not be before the completion of compulsory schooling, which is usually 15 years.

- Light work

Children between the ages of 13 and 15 may do light work as long as it does not endanger their health or safety or interfere with their education, career guidance and training.

A better conceptual understanding of the problem of child labor has been provided at the same time as a better understanding of the outline of the problem and the causes that give rise to it. The 2002 global report noted that the vast majority of child labor (70%) is concentrated in the agricultural sector, and the informal sector accounts for the bulk of child labor compared to other sectors of the economy. In addition, gender plays a significant role in determining the different types of jobs that girls and boys perform. For example, girls are more involved in domestic work, while boys are very well represented in mines and mines. The situation worsens when many countries exclude home-based work from regulation.

Our understanding of the causes of child labor has become more refined as the problem has been examined from different scientific points of view. It has been very fruitful to consider the problem of child labor as a product of market forces - supply and demand, when the behavior of employers as well as individual households is taken into account. Undoubtedly, poverty and economic shocks play an important, if not key, role in defining the market for child labor. In turn, child labor contributes to the perpetuation of poverty. For example, according to the latest empirical research carried out by the World Bank in Brazil, entering the labor market at an early age reduces lifetime earnings by about 13-20%, which significantly increases the likelihood of remaining poor later in life.

It has been very fruitful to consider the problem of child labor as a product of market forces - supply and demand, when the behavior of employers as well as individual households is taken into account. Undoubtedly, poverty and economic shocks play an important, if not key, role in defining the market for child labor. In turn, child labor contributes to the perpetuation of poverty. For example, according to the latest empirical research carried out by the World Bank in Brazil, entering the labor market at an early age reduces lifetime earnings by about 13-20%, which significantly increases the likelihood of remaining poor later in life.

However, poverty is not a sufficient explanation for child labor, and it certainly cannot explain some of the by far worst forms of child labor. A human rights perspective is needed to focus the approach on issues of discrimination and social exclusion, which are the contributing factors to this phenomenon. The most vulnerable groups affected by child labor are often those populations that experience various forms of discrimination and social exclusion: girls, ethnic minorities, indigenous and tribal peoples, lower class or caste people, persons with disabilities, displaced individuals and populations in remote areas.

In 2002, the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Children unanimously endorsed a mainstream approach to place child labor on the development agenda. This means setting ambitious new goals for the global movement against child labor. Politically, this means that the issue of child labor is on the agenda of finance and planning ministries, because ultimately the global child labor movement must convince governments to take action to end child labor. The abolition of child labor becomes a set of policy options rather than a technocratic exercise. Moreover, everyday realities, characterized by instability and crisis, challenge attempts to achieve progress.

Child labor in Europe: a continuing challenge - Human Rights Comments -

© 2013 Volunteer Weekly

Many observers believed that child labor in Europe was a thing of the past. However, there is very strong evidence that child labor is still a significant problem and that it may increase with the advent of the economic crisis. Governments should monitor this situation and use the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the European Social Charter as recommendations for preventive and corrective action.

Governments should monitor this situation and use the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the European Social Charter as recommendations for preventive and corrective action.

In times of economic downturn, vulnerable people always suffer more than others. Therefore, the association between a decline in economic growth and an increase in child labor is not surprising. Due to the recession, many European countries have drastically reduced social assistance. And as unemployment rises, many families have found no other solution than to send their children to work.

Harmful and dangerous work

The prevalence of child labor in developing countries is a well-known problem: according to the International Labor Organization, more than 250 million children between the ages of 5 and 14 are currently working. However, when we began to analyze the situation in Europe, we found in my Office that there was very little information on this subject. In fact, it seems that this topic is taboo. However, we were able to gather enough information to paint a rather bleak picture.

However, we were able to gather enough information to paint a rather bleak picture.

According to UNESCO, 29% of children aged 7-14 work in Georgia. In Albania this figure is 19%. The government of the Russian Federation estimates that up to 1 million children work in the country. However, data are not yet available for most other countries. In Italy, a 2013 study shows that 5.2% of children under the age of 16 are employed.

Many of those children who work throughout Europe are engaged in highly hazardous work in agriculture, construction, small businesses or on the street. This is reported, for example, for Albania, Bulgaria, Georgia, Moldova, Romania, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine and Montenegro. Working in agriculture can involve dangerous equipment and tools, carrying heavy loads, and using harmful pesticides. And working on the streets leads to the fact that children are harassed and exploited.

In Bulgaria, child labor appears to be very common in the tobacco industry and some children work up to 10 hours a day. According to reports from Moldova, directors of schools, farms and agricultural cooperatives have signed agreements that require students to help with the harvest.

According to reports from Moldova, directors of schools, farms and agricultural cooperatives have signed agreements that require students to help with the harvest.

Other countries at risk are those that have been hit hard by austerity measures: Cyprus, Greece, Italy and Portugal. Quite a few children are reported to work long hours in the United Kingdom as well.

Roma children are at particular risk throughout Europe. Another particularly vulnerable group is unaccompanied migrants under the age of 18 coming from developing countries.

What to do

- Governments urgently need to focus on child labor issues, investigate, collect data and monitor. Most countries have legislation in place but do not track current practice.

- The guiding principle should be the best interests of the child, as provided for in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the standards of the European Social Charter.

- Authorities should carefully assess the potential impact on child labor of budget cuts in education and training.

- They should also analyze the impact on child labor due to cuts in social services and family support: the main reason why children are forced to work is poverty.

- Labor inspection institutions should be able to carry out their work properly.

- States must actively combat the sale of children for forced labor and exploitation. Those seven member states of the Council of Europe that have not yet ratified the Convention against Trafficking in Human Beings should do so, and all member states should cooperate with the GRETA monitoring group.

What will be the future of these children?

I am deeply concerned that so little attention has been paid to the risks of child labor in Europe. In most countries, officials are aware of this problem, but few are willing to deal with it. The very fact that data and figures are almost non-existent or very approximate is in itself a source of concern. It is impossible to fight a problem without knowing its extent, nature and consequences.

Of particular concern is that the need to work interferes with children's schooling: this quickly begins to affect their academic performance and many of them eventually leave school. And this only reproduces the vicious circle of poverty. A country can develop only when it chooses education for children, not work.

Many concrete measures need to be taken. Last year we saw one of these actions taken in Turkey, where the government passed a law that raises the compulsory education age to 17 in order to minimize the risk of labor exploitation. We need more initiatives like this.

When the problem of child labor is not addressed, it only jeopardizes the future of these children. This raises the question of what our societies will look like in the future when these children grow up without the opportunity to play and learn at school, and instead are exposed to various health risks from a very young age. We must act now for the future of these children and our own societies.