How do you know your child has an ear infection

Ear Infections in Babies and Toddlers

Featured Expert:

Ear infections in babies and toddlers are extremely common. In fact, according to the National Institutes of Health, five out of six children will experience an ear infection before their third birthday.

"Many parents are concerned that an ear infection will affect their child's hearing irreversibly—or that an ear infection will go undetected and untreated," says David Tunkel, M.D., Johns Hopkins Medicine pediatric otolaryngologist (ENT). "The good news is that most ear infections go away on their own, and those that don't are typically easy to treat."

Childhood Ear Infections Explained

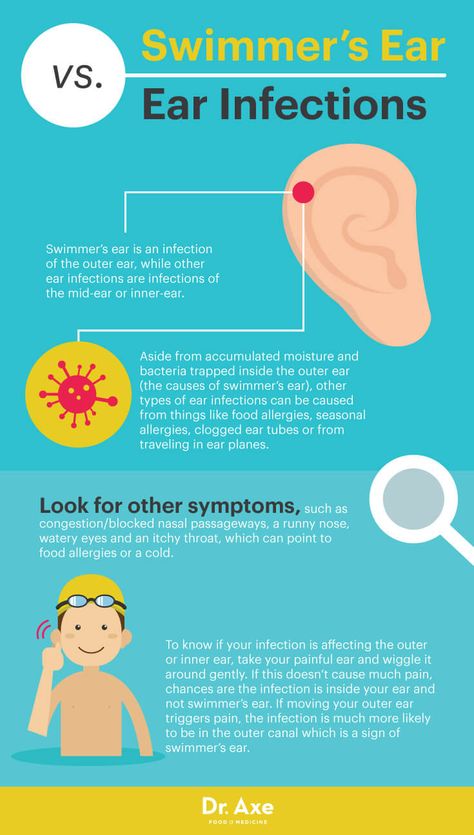

Ear infections happen when there is inflammation— usually from trapped bacteria—in the middle ear, the part of the ear connects to the back of the nose and throat. The most common type of ear infection is otitis media, which results when fluid builds up behind the eardrum and parts of the middle ear become infected and swollen.

If your child has a sore throat, cold, or an upper respiratory infection, bacteria can spread to the middle ear through the eustachian tubes (the channels that connect the middle ear to the throat). In response to the infection, fluid builds up behind the eardrum.

Children are more likely to suffer from ear infections than adults for two reasons:

- Their immune systems are underdeveloped and less equipped to fight off infections.

- Their eustachian tubes are smaller and more horizontal, which makes it more difficult for fluid to drain out of the ear.

"In some cases, fluid remains trapped in the middle ear for a long time, or returns repeatedly, even when there's no infection," Tunkel explains.

Ear Infection Signs and Symptoms

The telltale sign of an ear infection is pain in and around the ear. Young children can develop ear infections before they are old enough to talk. That means parents are often left guessing why their child appears to be suffering. When your child can't say "my ear hurts," the following signs suggest an ear infection could be the culprit:

Young children can develop ear infections before they are old enough to talk. That means parents are often left guessing why their child appears to be suffering. When your child can't say "my ear hurts," the following signs suggest an ear infection could be the culprit:

- Tugging or pulling the ear

- Crying and irritability

- Difficulty sleeping

- Fever, especially in younger children

- Fluid draining from the ear

- Loss of balance

- Difficulty hearing or responding to auditory cues

Signs that require immediate attention include high fever, severe pain, or bloody or pus-like discharge from the ears.

Pediatric Otolaryngology

Our pediatric otolaryngologists provide compassionate and comprehensive care for children with common and rare ear, nose, and throat conditions. As part of the Johns Hopkins Children's Center, you have access to all the specialized resources of a children's hospital.

Learn more about Pediatric Otolaryngology

Ear Infection Treatments

Most ear infections go away without treatment. "If your child isn't in severe pain, your doctor may suggest a 'wait-and-see' approach coupled with over-the-counter pain relievers to see if the infection clears on its own," Tunkel says.

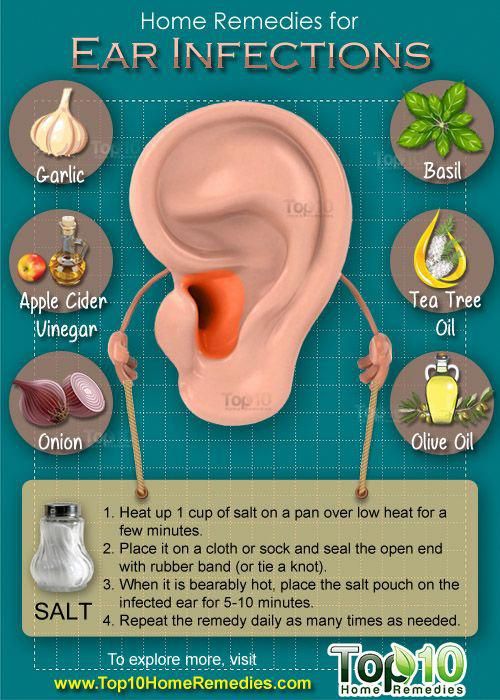

The reason: Treating an infection with antibiotics may cause the bacteria causing the infections to become resistant to those antibiotics—and that makes treating future infections more difficult. Equally important, in most cases antibiotics aren't necessary. Otitis media tends to get better without them. While you may be tempted to treat your child's ear infection with homeopathic or natural medicine, Tunkel warns they aren’t well studied.

Your best bet is to work with your child's health care provider to determine the appropriate course of action. In nearly every case, treatment decisions depend on the child’s age, degree of pain and presenting symptoms.

Under 6 months

Babies under six months almost always receive antibiotics. At this age, children are not fully vaccinated. Equally important, there's no research about the safety of skipping antibiotics for babies under 6 months of age — and complications from ear infections can be more severe when they occur in young babies. Bacteria trapped behind the eardrum can spread to other parts of the body and cause serious infections.

6 months to 2 years

For children between the ages of 6 months and 2 years, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends shared decision-making between parents and providers about whether to treat ear infections that are not severe. The best course is often to watch the child for two to three days before prescribing antibiotic treatment. If the child is in pain, or the ear infection is advanced, your child's doctor may suggest immediate antibiotic treatment.

Over 2 years

With children over the age of 2, ear infections that are not severe are likely to clear on their own, without treatment. "In the meantime, you can treat pain with over-the-counter medications, such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen," Tunkel says. If there's no improvement after two to three days, antibiotics may be warranted.

"In the meantime, you can treat pain with over-the-counter medications, such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen," Tunkel says. If there's no improvement after two to three days, antibiotics may be warranted.

Unfortunately, some children suffer from recurrent ear infections, sometimes up to five or six a year. Kids who get repeated infections may benefit from a surgical procedure where doctors insert small tubes in the eardrums to improve air flow and prevent fluid buildup. "Tubes don't prevent all ear infections, but they make managing them significantly easier," Tunkel explains.

Ear Infection Prevention

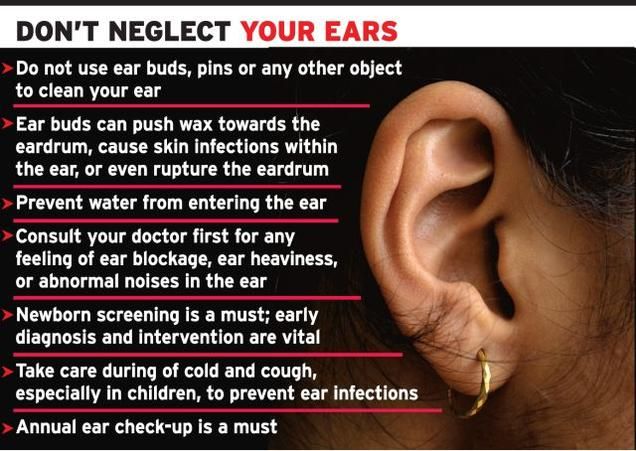

There are several steps you can take to reduce your child's risk of developing ear infections, including:

- Vaccinate your child: Children who are up-to-date on their vaccines get fewer ear infections than their unvaccinated counterparts. The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) protects against 13 types of infection-causing bacteria.

- Consider breastfeeding: Breast milk contains antibodies that may help reduce the risk of ear infections and a host of other ailments. Whether you feed milk or formula, make sure your child sits up during feedings to prevent fluid from flowing into the middle ear.

- Wash your hands frequently: The best way to protect your child against cold and flu is to keep your hands clean. Wash your hands with soap and water and scrub them clean for a full 20 seconds each time you visit the sink.

- Steer clear of sick people: Don't allow your child to spend time with children or adults who are sick.

- Avoid secondhand smoke: Studies show that children who are exposed to secondhand smoke are up to three times more likely to develop ear infections than those who don't have those exposures.

Whether your child has ear infections or not, it's important to ensure they're able to hear well. "No child is too young to have a hearing test," Tunkel says. "We use a variety of techniques to test infant hearing and we can identify a hearing problem even in newborns."

"No child is too young to have a hearing test," Tunkel says. "We use a variety of techniques to test infant hearing and we can identify a hearing problem even in newborns."

Ear Infections in Children, Babies & Toddlers

What is an ear infection?

An ear infection is an inflammation of the middle ear, usually caused by bacteria, that occurs when fluid builds up behind the eardrum. Anyone can get an ear infection, but children get them more often than adults. Five out of six children will have at least one ear infection by their third birthday. In fact, ear infections are the most common reason parents bring their child to a doctor. The scientific name for an ear infection is otitis media (OM).

What are the symptoms of an ear infection?

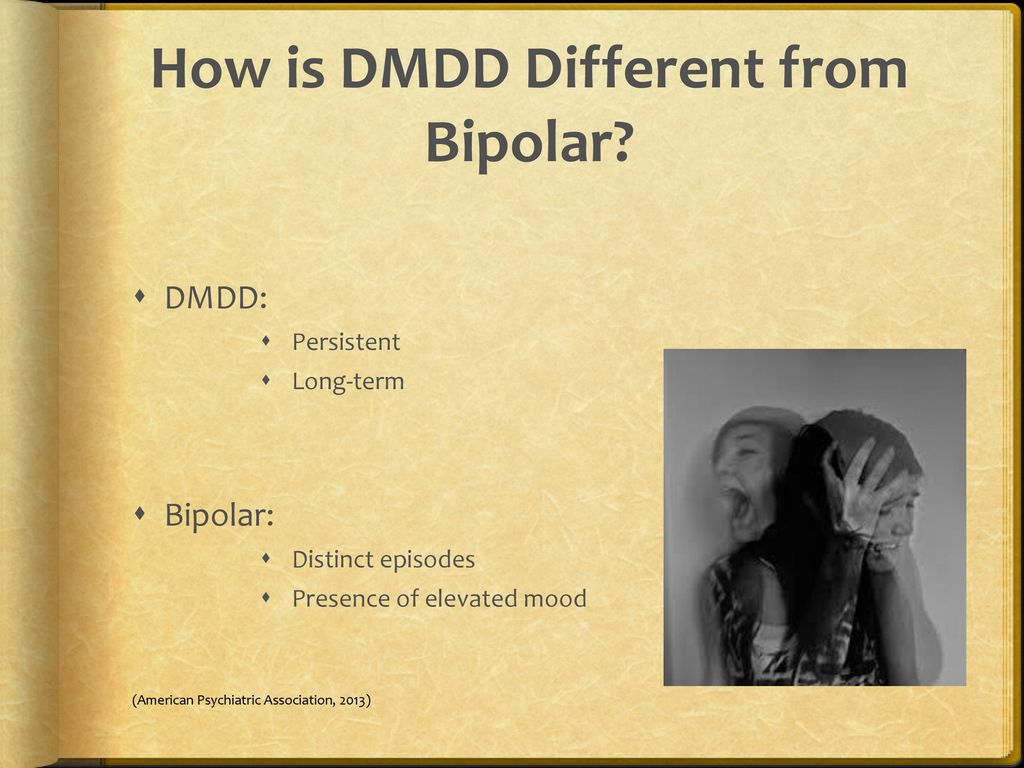

There are three main types of ear infections. Each has a different combination of symptoms.

- Acute otitis media (AOM) is the most common ear infection. Parts of the middle ear are infected and swollen and fluid is trapped behind the eardrum.

This causes pain in the ear—commonly called an earache. Your child might also have a fever.

This causes pain in the ear—commonly called an earache. Your child might also have a fever. - Otitis media with effusion (OME) sometimes happens after an ear infection has run its course and fluid stays trapped behind the eardrum. A child with OME may have no symptoms, but a doctor will be able to see the fluid behind the eardrum with a special instrument.

- Chronic otitis media with effusion (COME) happens when fluid remains in the middle ear for a long time or returns over and over again, even though there is no infection. COME makes it harder for children to fight new infections and also can affect their hearing.

How can I tell if my child has an ear infection?

Most ear infections happen to children before they’ve learned how to talk. If your child isn’t old enough to say “My ear hurts,” here are a few things to look for:

- Tugging or pulling at the ear(s)

- Fussiness and crying

- Trouble sleeping

- Fever (especially in infants and younger children)

- Fluid draining from the ear

- Clumsiness or problems with balance

- Trouble hearing or responding to quiet sounds

What causes an ear infection?

An ear infection usually is caused by bacteria and often begins after a child has a sore throat, cold, or other upper respiratory infection. If the upper respiratory infection is bacterial, these same bacteria may spread to the middle ear; if the upper respiratory infection is caused by a virus, such as a cold, bacteria may be drawn to the microbe-friendly environment and move into the middle ear as a secondary infection. Because of the infection, fluid builds up behind the eardrum.

If the upper respiratory infection is bacterial, these same bacteria may spread to the middle ear; if the upper respiratory infection is caused by a virus, such as a cold, bacteria may be drawn to the microbe-friendly environment and move into the middle ear as a secondary infection. Because of the infection, fluid builds up behind the eardrum.

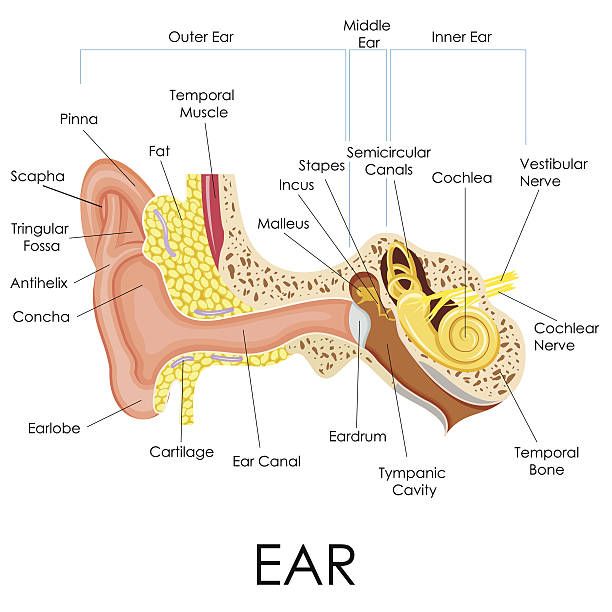

Image

Source: NIH/NIDCDThe ear has three major parts: the outer ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear. The outer ear, also called the pinna, includes everything we see on the outside—the curved flap of the ear leading down to the earlobe—but it also includes the ear canal, which begins at the opening to the ear and extends to the eardrum. The eardrum is a membrane that separates the outer ear from the middle ear.

The middle ear—which is where ear infections occur—is located between the eardrum and the inner ear. Within the middle ear are three tiny bones called the malleus, incus, and stapes that transmit sound vibrations from the eardrum to the inner ear. The bones of the middle ear are surrounded by air.

The bones of the middle ear are surrounded by air.

The inner ear contains the labyrinth, which help us keep our balance. The cochlea, a part of the labyrinth, is a snail-shaped organ that converts sound vibrations from the middle ear into electrical signals. The auditory nerve carries these signals from the cochlea to the brain.

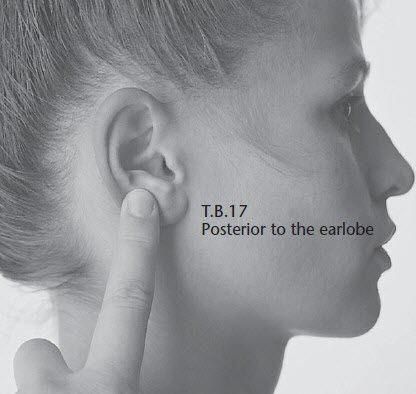

Other nearby parts of the ear also can be involved in ear infections. The eustachian tube is a small passageway that connects the upper part of the throat to the middle ear. Its job is to supply fresh air to the middle ear, drain fluid, and keep air pressure at a steady level between the nose and the ear.

Adenoids are small pads of tissue located behind the back of the nose, above the throat, and near the eustachian tubes. Adenoids are mostly made up of immune system cells. They fight off infection by trapping bacteria that enter through the mouth.

Why are children more likely than adults to get ear infections?

There are several reasons why children are more likely than adults to get ear infections.

Eustachian tubes are smaller and more level in children than they are in adults. This makes it difficult for fluid to drain out of the ear, even under normal conditions. If the eustachian tubes are swollen or blocked with mucus due to a cold or other respiratory illness, fluid may not be able to drain.

A child’s immune system isn’t as effective as an adult’s because it’s still developing. This makes it harder for children to fight infections.

As part of the immune system, the adenoids respond to bacteria passing through the nose and mouth. Sometimes bacteria get trapped in the adenoids, causing a chronic infection that can then pass on to the eustachian tubes and the middle ear.

How does a doctor diagnose a middle ear infection?

The first thing a doctor will do is ask you about your child’s health. Has your child had a head cold or sore throat recently? Is he having trouble sleeping? Is she pulling at her ears? If an ear infection seems likely, the simplest way for a doctor to tell is to use a lighted instrument, called an otoscope, to look at the eardrum. A red, bulging eardrum indicates an infection.

A red, bulging eardrum indicates an infection.

A doctor also may use a pneumatic otoscope, which blows a puff of air into the ear canal, to check for fluid behind the eardrum. A normal eardrum will move back and forth more easily than an eardrum with fluid behind it.

Tympanometry, which uses sound tones and air pressure, is a diagnostic test a doctor might use if the diagnosis still isn’t clear. A tympanometer is a small, soft plug that contains a tiny microphone and speaker as well as a device that varies air pressure in the ear. It measures how flexible the eardrum is at different pressures.

How is an acute middle ear infection treated?

Many doctors will prescribe an antibiotic, such as amoxicillin, to be taken over seven to 10 days. Your doctor also may recommend over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, or eardrops, to help with fever and pain. (Because aspirin is considered a major preventable risk factor for Reye’s syndrome, a child who has a fever or other flu-like symptoms should not be given aspirin unless instructed to by your doctor. )

)

If your doctor isn’t able to make a definite diagnosis of OM and your child doesn’t have severe ear pain or a fever, your doctor might ask you to wait a day or two to see if the earache goes away. The American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidelines in 2013 that encourage doctors to observe and closely follow these children with ear infections that can’t be definitively diagnosed, especially those between the ages of 6 months to 2 years. If there’s no improvement within 48 to 72 hours from when symptoms began, the guidelines recommend doctors start antibiotic therapy. Sometimes ear pain isn’t caused by infection, and some ear infections may get better without antibiotics. Using antibiotics cautiously and with good reason helps prevent the development of bacteria that become resistant to antibiotics.

If your doctor prescribes an antibiotic, it’s important to make sure your child takes it exactly as prescribed and for the full amount of time. Even though your child may seem better in a few days, the infection still hasn’t completely cleared from the ear. Stopping the medicine too soon could allow the infection to come back. It’s also important to return for your child’s follow-up visit, so that the doctor can check if the infection is gone.

Stopping the medicine too soon could allow the infection to come back. It’s also important to return for your child’s follow-up visit, so that the doctor can check if the infection is gone.

How long will it take my child to get better?

Your child should start feeling better within a few days after visiting the doctor. If it’s been several days and your child still seems sick, call your doctor. Your child might need a different antibiotic. Once the infection clears, fluid may still remain in the middle ear but usually disappears within three to six weeks.

What happens if my child keeps getting ear infections?

To keep a middle ear infection from coming back, it helps to limit some of the factors that might put your child at risk, such as not being around people who smoke and not going to bed with a bottle. In spite of these precautions, some children may continue to have middle ear infections, sometimes as many as five or six a year. Your doctor may want to wait for several months to see if things get better on their own but, if the infections keep coming back and antibiotics aren’t helping, many doctors will recommend a surgical procedure that places a small ventilation tube in the eardrum to improve air flow and prevent fluid backup in the middle ear. The most commonly used tubes stay in place for six to nine months and require follow-up visits until they fall out.

The most commonly used tubes stay in place for six to nine months and require follow-up visits until they fall out.

If placement of the tubes still doesn’t prevent infections, a doctor may consider removing the adenoids to prevent infection from spreading to the eustachian tubes.

Can ear infections be prevented?

Currently, the best way to prevent ear infections is to reduce the risk factors associated with them. Here are some things you might want to do to lower your child’s risk for ear infections.

- Vaccinate your child against the flu. Make sure your child gets the influenza, or flu, vaccine every year.

- It is recommended that you vaccinate your child with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13). The PCV13 protects against more types of infection-causing bacteria than the previous vaccine, the PCV7. If your child already has begun PCV7 vaccination, consult your physician about how to transition to PCV13. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that children under age 2 be vaccinated, starting at 2 months of age.

Studies have shown that vaccinated children get far fewer ear infections than children who aren’t vaccinated. The vaccine is strongly recommended for children in daycare.

Studies have shown that vaccinated children get far fewer ear infections than children who aren’t vaccinated. The vaccine is strongly recommended for children in daycare. - Wash hands frequently. Washing hands prevents the spread of germs and can help keep your child from catching a cold or the flu.

- Avoid exposing your baby to cigarette smoke. Studies have shown that babies who are around smokers have more ear infections.

- Never put your baby down for a nap, or for the night, with a bottle.

- Don’t allow sick children to spend time together. As much as possible, limit your child’s exposure to other children when your child or your child’s playmates are sick.

What research is being done on middle ear infections?

Researchers sponsored by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) are exploring many areas to improve the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of middle ear infections. For example, finding better ways to predict which children are at higher risk of developing an ear infection could lead to successful prevention tactics.

Another area that needs exploration is why some children have more ear infections than others. For example, Native American and Hispanic children have more infections than do children in other ethnic groups. What kinds of preventive measures could be taken to lower the risks?

Doctors also are beginning to learn more about what happens in the ears of children who have recurring ear infections. They have identified colonies of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, called biofilms, that are present in the middle ears of most children with chronic ear infections. Understanding how to attack and kill these biofilms would be one way to successfully treat chronic ear infections and avoid surgery.

Understanding the impact that ear infections have on a child’s speech and language development is another important area of study. Creating more accurate methods to diagnose middle ear infections would help doctors prescribe more targeted treatments. Researchers also are evaluating drugs currently being used to treat ear infections, and developing new, more effective and easier ways to administer medicines.

NIDCD-supported investigators continue to explore vaccines against some of the most common bacteria and viruses that cause middle ear infections, such as nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) and Moraxella catarrhalis. One team is conducting studies on a method for delivering a possible vaccine without a needle.

Where can I find additional information about ear infections?

The NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations that provide information on the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, smell, taste, voice, speech, and language.

Use the following keywords to help you search for organizations that can answer questions and provide printed or electronic information on ear infections:

- Otitis media (ear infection)

- Speech-language development

- Early identification of hearing loss in children

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse

1 Communication Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20892-3456

Toll-free voice: (800) 241-1044

Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055

Email: nidcdinfo@nidcd. nih.gov

nih.gov

HOW TO RECOGNIZE OTITIS IN A CHILD AND HOW TO PREVENT IT? — clinic "Dobrobut"

Meanwhile, three-quarters of all children at least once have problems with the ears before the age of three.

Why are ear infections so common in children?

Let's look into the middle ear to understand why small ears are so often affected by pathogens. The canal, which is called the Eustachian (auditory) tube, connects the nasopharynx and the middle ear cavity and performs many important functions: it helps to compare pressure, provides ventilation and protection. But it is in the nasopharynx that most bacteria find a nutrient medium for reproduction. Since the Eustachian tube in a child is short, wide and placed horizontally, the mucous discharge from the throat and nose, as well as any microorganisms in them, is easier to get through it into the middle ear cavity. The immune system of the child is not yet fully formed, and therefore vulnerable - it needs more time to fight many unfamiliar bacteria. This is how otitis often develops in many young children.

This is how otitis often develops in many young children.

Why is it important to properly treat children's ears?

Your child's hearing depends on the correct vibration of the eardrum and the condition of the other parts of the middle ear. Repeated infections can damage the eardrum, while the accumulation of fluid in the middle ear cavities negatively affects (sort of dampens) the vibration of the eardrum - eventually both interfere with the baby's normal hearing. That's why it's important to take otitis media treatment seriously, especially when your child is learning to speak. Partial hearing loss can lead to a delay in speech development or even pronunciation problems, later affecting the child's speech habits and learning success.

How to detect otitis media in a child?

It is unlikely that your baby will say: “Something unpleasant is happening in my ear and it hurts me. Please take me to the doctor! »But early diagnosis of otitis media and timely treatment have the best results and will prevent complications of otitis media.

Temperature . This is not an obligatory symptom of otitis media. The temperature in the baby rises against the background of a respiratory infection. But when the baby's temperature is above 37.5 ° C, be sure to consult your pediatrician. The following additional symptoms or a direct referral from your doctor will tell you about the need to contact a pediatric otolaryngologist.

Runny nose . The most common cause of otitis media is a cold that is accompanied by a runny nose. The same mucus secreted from the child's nose can also enter the Eustachian tube. As a rule, a runny nose in babies begins with an intensive production of a clear liquid secretion by the nasal mucosa, but after a few days it becomes yellow-green in color and becomes thicker. It is at this stage that it is important to thoroughly rinse the child's nose and remove mucus (if the child cannot do this on his own, nasal aspirators should be used) to prevent secretions from entering the middle ear cavity.

Bad sleep. If a child wakes up more often at night, cries, is naughty, or in some other way expresses that she is in pain, especially during ARVI, this is also an alarm signal.

Unusual behavior and feeling unwell. Parents can also pay attention to other manifestations of otitis media that make themselves felt by a change in the child's habitual behavior and a deterioration in her well-being in general:

However, as a rule, you can suspect an ear infection with a child crying sharply, caused by severe pain, especially when you touch her ears.

Should I see a doctor if I suspect otitis media?

Usually so. It is very difficult to prescribe the correct treatment in the presence of otitis without a preliminary examination. The doctor must determine the condition of the eardrum, check the nose and throat in order to select the correct appropriate complex therapy. In addition, the doctor will be able to advise you on how to prevent the development of the inflammatory process in the ear in the future and what painkillers can be used when the baby's ear starts to hurt (and this often happens in the middle of the night!).

The doctor must determine the condition of the eardrum, check the nose and throat in order to select the correct appropriate complex therapy. In addition, the doctor will be able to advise you on how to prevent the development of the inflammatory process in the ear in the future and what painkillers can be used when the baby's ear starts to hurt (and this often happens in the middle of the night!).

Mild to moderate ear infections can be completely cured with the use of topical anti-inflammatory agents. In this case, you need to carefully monitor the condition of the baby in order to notice the deterioration of the situation in time, and strictly follow the recommendations of the otolaryngologist. If the situation does not improve within two to three days, or in case of acute otitis media, at the first visit, the doctor may prescribe antibiotic therapy.

It is forbidden to treat a child with antibiotics without a doctor's prescription! Antibiotics are prescribed only when other treatments may not be effective. In this case, the doctor takes into account the age and weight of the child in order to correctly calculate the dosage and duration of the course of treatment.

In this case, the doctor takes into account the age and weight of the child in order to correctly calculate the dosage and duration of the course of treatment.

If a child twitches his ear, is he sick?

A child's habit of touching his ears does not necessarily indicate otitis media. The child may just be interested in exploring her ears, or she likes to pull on them, or her teething irritates the nerve endings and causes the child to constantly pull on her ears. But if the baby's increased interest in his ears is combined with crying, irritability, fever, runny nose, conjunctivitis, a cold in general, you should take this signal seriously. Very often, intuition helps attentive mothers to notice and recognize an ear infection in a child in time - especially when they already know what it is and how it can manifest itself.

How to prevent otitis in children?

Breastfeeding during the first year of life. Mother's milk provides the child's natural immunity and contains antibodies that can reduce the risk of developing various infections, including ear infections. If you are bottle feeding your baby, keep him upright (at least 30 degrees) and keep him upright for a few minutes after feeding. Milk can get into the middle ear if the baby is suckling lying down.

If you are bottle feeding your baby, keep him upright (at least 30 degrees) and keep him upright for a few minutes after feeding. Milk can get into the middle ear if the baby is suckling lying down.

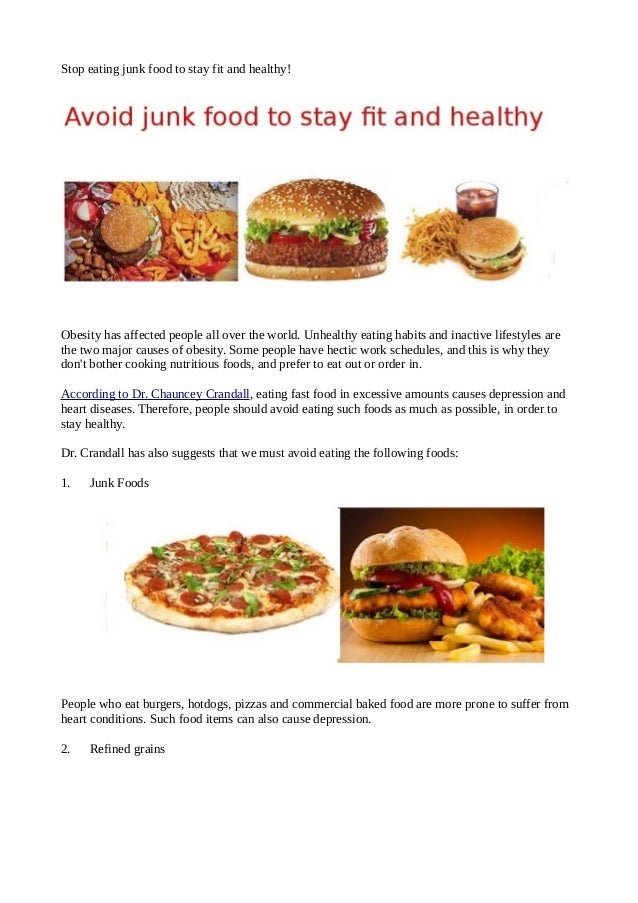

No allergens. Irritation of the nasal mucosa due to the influence of allergens leads to excessive production of mucus and swelling of the mucous membranes, which in turn causes blockage of fluid in the middle ear cavities. So get rid of any allergens. Even if your child is not allergic to certain pathogens, the room where she sleeps is not the place for pets, dust and the accumulation of soft toys in the crib. And it is absolutely forbidden to smoke in the presence of a child!

Avoid pacifiers. Studies have shown an association between frequency of pacifier use and otitis media. Try to discard the pacifier when the baby falls asleep and sleeps, especially if the baby is already over six months old.

Boost your immunity. Provide your child with a nutritious and balanced diet, plenty of time in the fresh air, and adopt healthy habits to strengthen the immune system.

Provide your child with a nutritious and balanced diet, plenty of time in the fresh air, and adopt healthy habits to strengthen the immune system.

Get vaccinated against the flu. Studies show that vaccinating a child to prevent influenza reduces the risk of SARS, and with it, otitis media.

Be patient. The good news is that as your baby gets older, their Eustachian tubes will get longer and narrower, making it harder for fluid to get into the middle ear. Meanwhile, the child's immune system becomes stronger, minimizing the risk of infection.

Otitis in a child: symptoms, first aid

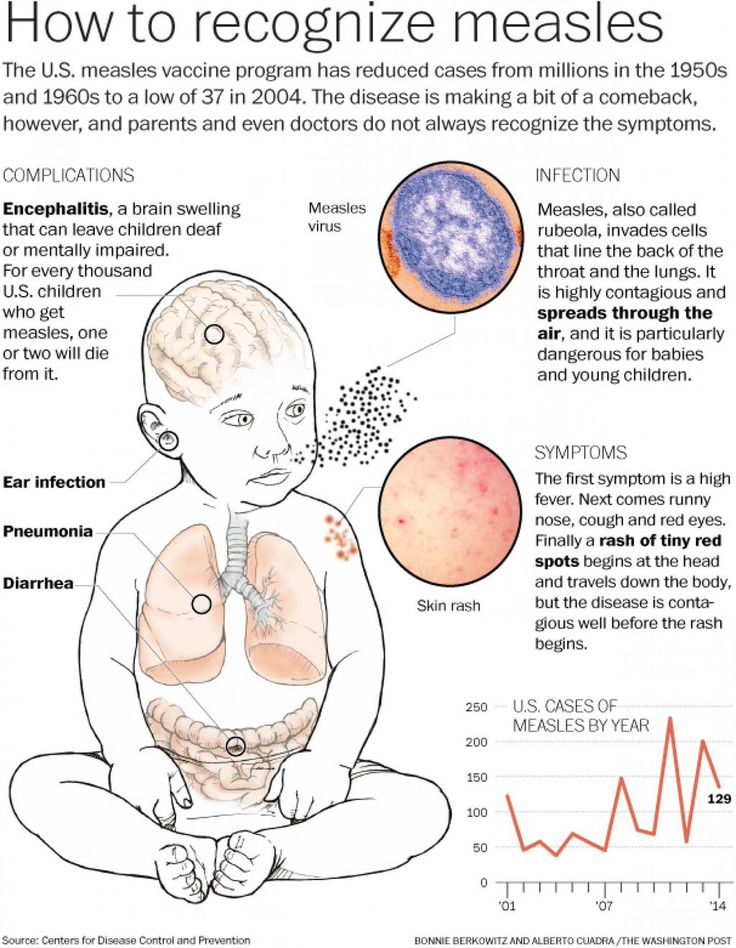

Children often get ARVI. Most infections pass quickly due to the protective functions of the baby's body, proper care, as well as adequate treatment. However, in some cases SARS occur with complications. Otitis media is one of the most common complications of viral respiratory infections in children. This is facilitated by the features of the anatomical structure in young children - a short, wide and more horizontal auditory tube, which connects the nasopharyngeal cavity and the middle ear, which means that the infection can easily penetrate from the nasopharynx. Otitis can cause infectious diseases such as measles, rubella. Sometimes it happens that frequent profuse regurgitation of the baby becomes the cause of otitis media, while the remnants of food can enter the middle ear through the auditory tube and cause inflammation. The cause of repeated otitis often becomes adenoiditis.

Otitis can cause infectious diseases such as measles, rubella. Sometimes it happens that frequent profuse regurgitation of the baby becomes the cause of otitis media, while the remnants of food can enter the middle ear through the auditory tube and cause inflammation. The cause of repeated otitis often becomes adenoiditis.

How otitis media manifests itself

In young children, it usually starts suddenly, with sharp pain in the ear. Older children may complain of hearing loss. Pain in the ear may be accompanied by a rise in temperature up to 40 0 C. It is more difficult to suspect otitis in infants, because. they can't complain about the pain. Parents may suspect otitis in a baby by the following signs:

- Crying, crying.

- Anxiety, capriciousness, sleep disturbances, refusal of the breast.

- Attempts to finger the ear, rolling the head on the pillow.

- Increased screaming and crying when pressing on the tragus of the ear.

Discharge from the ear is another symptom of otitis media. They can be serous or purulent, have an admixture of blood. Discharge from the ears with otitis occurs as a result of perforation (rupture) of the eardrum. Lack of treatment for this condition can lead to a persistent hearing loss in a baby, which once again confirms the need for immediate medical attention at the first sign of otitis media.

Treatment of otitis media and first aid

Treatment of otitis media must be prescribed by a doctor. No need to get involved in treatment without an examination by an otorhinolaryngologist. Usually otitis is treated with antibiotics, the course of treatment is 7-10 days. The toilet of the external auditory canal, the restoration of the patency of the Eustachian tube and the normalization of pressure in the tympanic cavity, local and general anti-inflammatory therapy, antibiotic therapy are among the main areas of treatment for otitis media. In some cases, the patient is shown paracentesis - a therapeutic puncture of the eardrum. Again, please note that only a doctor can prescribe specific drugs for your child.

In some cases, the patient is shown paracentesis - a therapeutic puncture of the eardrum. Again, please note that only a doctor can prescribe specific drugs for your child.

Help at home:

The use of vasoconstrictor nasal drops is an essential component of the treatment of otitis media. These drugs restore the patency of the auditory tube, which helps to normalize the pressure in the tympanic cavity.

- Put vasoconstrictor drops in your child's nose. Choose a drug that you have already taken.

- For fever and/or severe pain, give your child an age-appropriate antipyretic. Paracetamol and ibuprofen preparations effectively relieve pain in otitis media.

- Place with otitis indicated dry heat. It is enough to put on a hat or a scarf that covers the ears. Do not use hot compresses or heating pads unless directed by a doctor. Remember! Any thermal procedures are CONTRAINDICATED for suppuration and elevated temperature.

- If purulent or serous fluid is discharged from the ear, remove it with a cotton turunda soaked in 3% hydrogen peroxide solution.

Prophylaxis

It is necessary to treat the nose, nasopharynx and pharynx in time in children. This is especially true for enlarged adenoids. If the child is breathing heavily through his nose, sleeping with his mouth open, snoring, you need to contact an ENT doctor. If the doctor insists on removing the adenoids, consider and agree to this procedure. Treat other viral and bacterial diseases in a timely manner. For infants, the best prevention of otitis media is breastfeeding.

The following tips for caring for a child with SARS will help you reduce your chances of developing otitis:

- Never force your child to blow his nose. When you blow your nose, mucus enters the Eustachian tubes, which directly contributes to the development of otitis media.

- The eustachian tube is usually blocked by thick mucus.