How do i get my child to read

14 Ways to Encourage Grade-Schoolers to Read

It’s easier for kids to build reading skills when they enjoy reading. They practice more, and they feel more motivated to take on reading challenges. Try these tips to encourage your child to read — and hopefully build a love of reading.

1. Read it again and again.

Encourage your child to read familiar books. If your child wants to take the same book out of the library for the 100th time, that’s just fine. Re-reading helps build speed and accuracy. And that can help build confidence for kids who learn and think differently.

2. Make reading real.

Connect what your child reads with what’s happening in real life. For example, if you’re reading a story about basketball, ask questions about when your child learned to shoot hoops and how similar it was to the kids’ experience in the story.

You can also look for follow-up activities that make stories come to life. If the book references kites, ask your child to brainstorm fun kite-related activities, like how to make a kite. Hands-on activities like these can keep kids engaged with the topic.

3. Don’t leave home without something to read.

Bring along a kid-friendly book or magazine any time you know your child will have to wait in a doctor’s office, at the DMV, or anywhere else. Stories can help keep your child occupied. And the experience will show that you can always fit in time to read.

4. Dig deeper into the story.

Help your child engage with a story by asking questions about the characters’ thoughts, actions, or feelings: “Why does Jack think it’s a good idea to buy the magic beans? How does his mother feel after she finds out?” Encourage your child to connect to the story through experiences you may have had together.

5. Make reading a free-time activity.

Try to avoid making TV the reward and reading the punishment. Remind your child there are fun things to read besides books. And set a good example for your child by spending some of your free time reading instead of watching TV — and then talking about why you enjoyed it.

6. Take your time.

When your child is sounding out an unfamiliar word, leave plenty of time to do it, and praise the effort. Treat mistakes as an opportunity for improvement. Imagine your child misreads listen as list. Try re-reading the sentence together and ask which word makes more sense. Point out the similarities between the two words and the importance of noticing the final syllable.

7. Pick books at the right level.

Help your child find books that aren’t too hard or too easy. Kids have better reading experiences when they read books at the right level. You can check your choices by having your child read a few pages to you. Then ask questions about what was read. If your child struggles with reading the words or retelling the story, try a different book.

8. Play word games.

Use word games to help make your child more aware of the sounds in words. Say tongue twisters like “She sells seashells by the seashore. ” Sing songs that use wordplay, like Schoolhouse Rock’s “Conjunction Junction.” Or swap out the letters in words to turn them into new words. (For example, map can become nap or rap if you change the first letter, man if you change the final letter, and mop if you change the middle.)

” Sing songs that use wordplay, like Schoolhouse Rock’s “Conjunction Junction.” Or swap out the letters in words to turn them into new words. (For example, map can become nap or rap if you change the first letter, man if you change the final letter, and mop if you change the middle.)

9. Read to each other.

Take turns reading aloud during story time. As your child grows as a reader, you can gradually read less and let your child take the lead more often. If you have younger kids, too, encourage your older one to take on the responsibility of reading to them.

10. Point out the relationships between words.

Talk about words whenever you can. Explain how related words have similar spellings and meanings. Show how a noun like knowledge, for example, relates to a verb like know. Point out how the “wild” in wild and wilderness are spelled the same but pronounced differently.

11. Make books special.

Kids who have trouble with reading may try to avoid it because it makes them feel anxious or frustrated. Try to create positive feelings around reading by making it a treat. Get your child a library card or designate special reading time for just the two of you. Give books as gifts or rewards.

12. Make reading creative.

Change up reading activities to play to your child’s strengths. If your child loves to draw or make things, create a book together. Fold paper and staple it to resemble a book. Work together to write sentences on each page and have your child add illustrations or pictures. Then read it out loud together.

13. Let your child choose.

Some kids prefer nonfiction books. Some love only fantasy or graphic novels. Or maybe your child prefers audiobooks or reading things online. The important thing is to practice reading, no matter where or how it happens.

14. Look for a series of books.

Ask a librarian or a teacher for suggestions about popular book series your child might like. Reading a series of books helps kids get familiar with the tone, characters, and themes. This familiarity can make the next books in the series easier to grasp.

Reading a series of books helps kids get familiar with the tone, characters, and themes. This familiarity can make the next books in the series easier to grasp.

Get tips on fun books for reluctant readers. You can also check out book picks from our community.

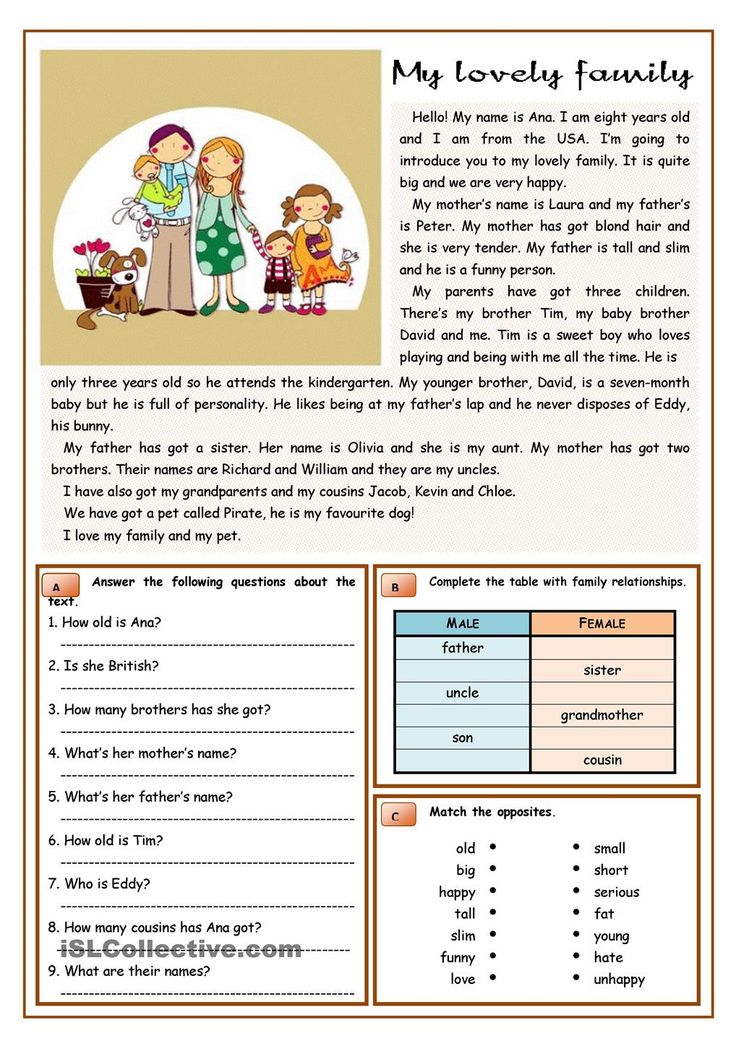

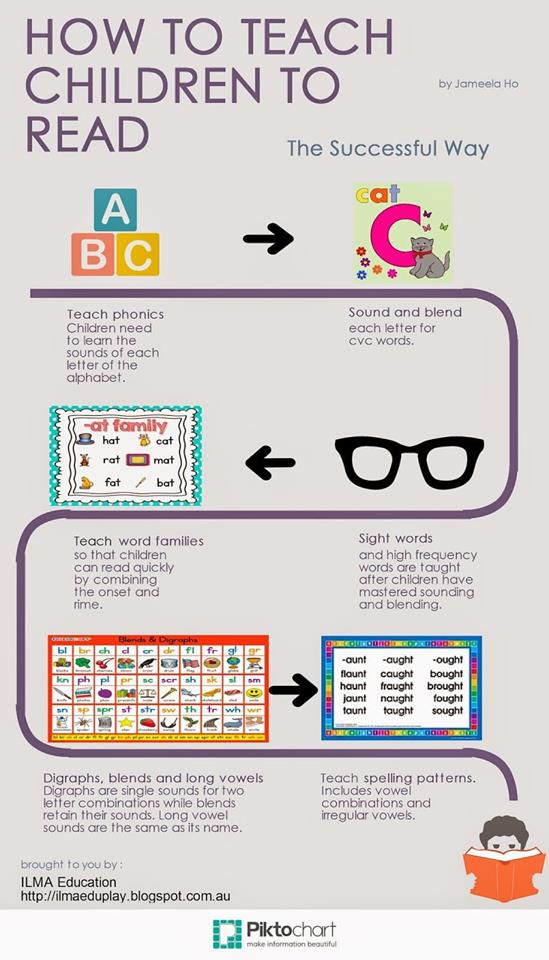

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

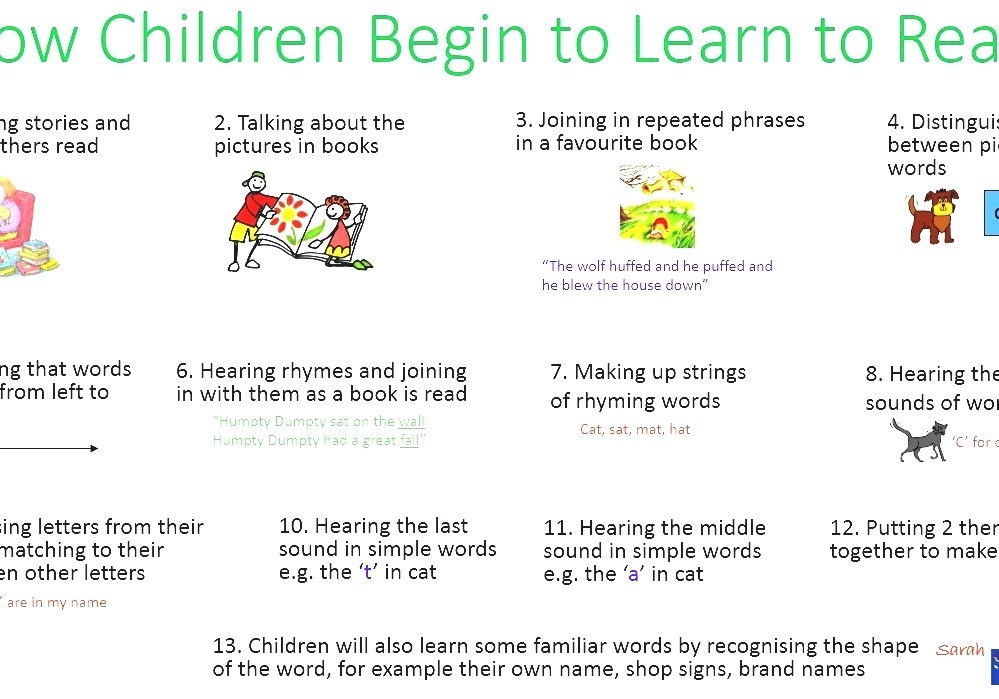

How do kids actually learn how to read?

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

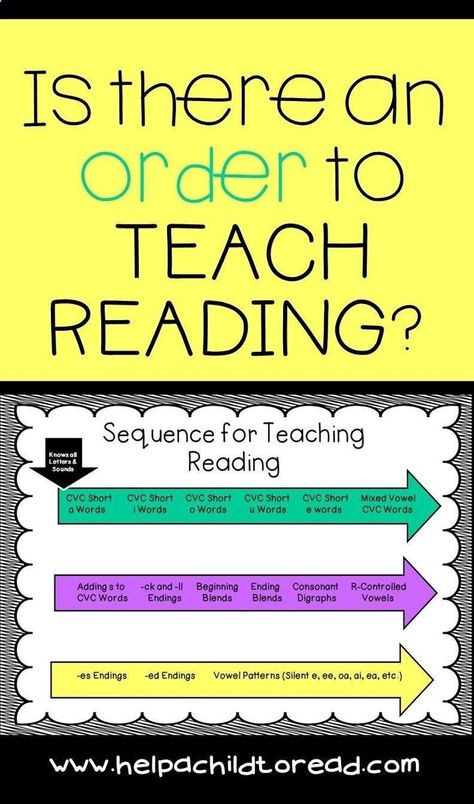

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

“But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction.” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

“If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons.”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

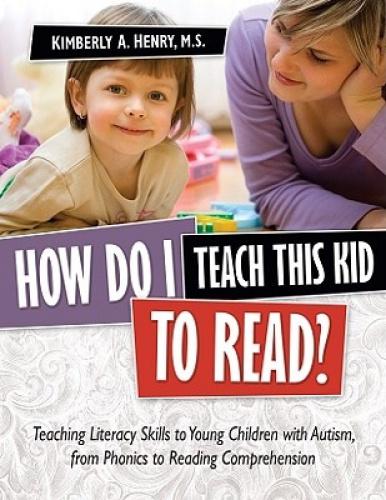

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed.”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun. ’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

7 tips on how to help your child fall in love with reading (voluntarily!)

For one child, a book is really the best gift, while another will cringe at the sight of another volume. They force you at school, now at home too. But you don’t need to force it, even a school reading list for the summer. How to really captivate a child with books - says a specialist in children's reading and writer Yulia Kuznetsova.

They force you at school, now at home too. But you don’t need to force it, even a school reading list for the summer. How to really captivate a child with books - says a specialist in children's reading and writer Yulia Kuznetsova.

1. Do not force a child to read

The desire to read is formed from within, so I am sure that forcing a child to read at five or six years old is a dangerous path. The word "should" should be applied to children's reading in general with caution and at a more serious age, from grade 5-6 and only in relation to school literature.

If a child does not feel like reading by himself, there is nothing wrong with that. My middle son did not take reading aloud until he was three years old. While I was reading to my eldest daughter, he was crawling around on the sofa, pinching our hair - it only annoyed me. Then suddenly, at the age of four, he fell in love with reading aloud. At the age of five, we began to teach him to read, at first he did not particularly like to do this either. And by the age of six, reading began, this is a spontaneous process.

And by the age of six, reading began, this is a spontaneous process.

Often parents are afraid that their child will go to school without being able to read. It all depends on the teacher. Now I hear about cases when teachers say: “I don’t need parents to bring the child to some level, otherwise he will be simply bored in the lessons.”

2. Surrounding children with books is good advice, but it doesn't always work

My experience is very different. When I came back from book festivals and brought bags of books to children, we had the following dialogue: "I brought you gifts" - "What gifts?" - "Books" - "I see, but did you bring normal gifts?"

When there are many books in the family, the following stories may come up. You ask: "Do you want to read a book?" - "Not". They closed the book and put it in the fridge. After a while, you ask again, you get the same answer, and you put the book on the windowsill. It turns out that these “I don’t want” lie all over the apartment.

It seems to me that we should remember our book experience, when there were always not enough books in childhood. Especially the ones you really wanted to read. I run courses for children where we do group calculations, we have our own library that fits on a chair. These are books from my home library that have gone through a rigorous selection: they will definitely appeal to children who do not like and do not want to read. Children come, sit down, see some books, they are interested in taking them and looking at them, but I don’t let them do it. They say, “Please, please, can I? If I don’t take it now, then Petya will take this book later.” I say: "No, now we have a lesson, we are doing other interesting things." And when they see that the books cannot be freely approached, then after the lesson they scatter in a second. A mob runs up, they take everything apart and take it home. Moreover, the children know that next time I will ask what this book was about.

3.

Talk with your children about the books you read yourself

Talk with your children about the books you read yourself Parents who read in front of their children are very rare. Use these moments to talk to him about the book you are reading right now, or even try reading out snippets. For example, my daughter once loved sheep very much, and I was reading Sheep Hunt by Haruki Murakami just at that time. When she found out about this, she said: “Sheep are being killed there, I feel sorry for them.” I offered to read a fragment of the book aloud to her so that she would see that no one was being killed there. I read the description of the pasture to her, and she was so delighted: her mother let her touch her book.

You can discuss books with other adults in front of children. I discuss books on the phone with my mother

We have similar tastes, my mother likes modern Russian women's prose, for example, Marina Stepanova. We call her and discuss some books, and the children hear it all.

4. Read aloud. And record reading on a voice recorder

Parents spend the whole day at work, and if after that they read aloud to their children for at least ten minutes, this becomes a powerful lock that holds relationships together. You can also not only read aloud, but also record reading on a voice recorder. The phone is not suitable for this, because it will switch attention to itself all the time. There is only one button on the voice recorder - turn it on and off.

You can also not only read aloud, but also record reading on a voice recorder. The phone is not suitable for this, because it will switch attention to itself all the time. There is only one button on the voice recorder - turn it on and off.

Dad sits down, reads aloud to them, all this is recorded on a dictaphone. One chapter in a children's book lasts an average of 10-15 minutes, this time is enough for the event called "evening reading" to take place. When dad leaves for a business trip, the children listen to the recordings. They turn it on when they eat, when they draw. This is not just a text, this is a memory of how good it was with dad in the evening.

5. Don't ignore audiobooks - they help with text

Audiobooks are a relief for children who are not very confident and see mostly letters, not images. They first get used to, and then return to a paper book. This mechanism also works with films (yes, yes). Children first watch the movie, find out how it all ends there, and then take the book and read it. It happens that children take the book even after performances. The host of the theater studio told how she staged "Uncle Vanya" with teenagers, and then a boy came to her and asked: "Is it possible to read this somewhere?" So a well-read audiobook, especially if you listen to it with your parents and discuss the plot, can also help instill a love of reading.

It happens that children take the book even after performances. The host of the theater studio told how she staged "Uncle Vanya" with teenagers, and then a boy came to her and asked: "Is it possible to read this somewhere?" So a well-read audiobook, especially if you listen to it with your parents and discuss the plot, can also help instill a love of reading.

6. Write a book about your child - this is another way to help him start reading

Take a picture or draw your child, stick it on a piece of paper and write: "This is Kolya." Then take a picture of how he eats and write: "Kolya eats." Then you can take a picture of how he sleeps, plays, and so on. Make such a book and show a child at the age of three - let him look at all this. When he is four years old, he will understand that letters can somehow be put together into words and will start trying to do it. Reading about yourself is always more interesting. My daughter is 12 years old, and she sits down with pleasure herself and reads a book about what she did nine years ago: she sculpted hedgehogs, kneaded the dough, molded cookies from it.

In my lessons I set aside 15 minutes and we write a book about ourselves. I give simple phrases that need to be completed: "Once I went ...", "And suddenly I saw ...", "Here I meet ...". It takes a little time, but it works very well. Children can write whole volumes about themselves.

In fact, for students who have difficulty in reading, it can be like writing classes - this is a good way to overcome reading difficulties. It seems that the child is learning to write, but at the same time learning to read. I had a girl on the course who stuttered and skipped words when reading. But when I read my text, I did not miss a single word. For her it was very important.

7. Do not be afraid that the child will not read the school list of literature for the summer

Take the list of literature, a pen and first of all cross out the books that the child definitely does not need. During communication with the teacher, you can understand what he wanted, including this or that book in the list. For example, in the first grade in our textbook there was a fragment from The Hobbit. The teacher decided that since there is a piece from Tolkien, then you need to read the whole book. I say, "Sorry, guys," and cross it out. We tried to watch a movie based on the book, but the children didn't get it: they were just scared.

For example, in the first grade in our textbook there was a fragment from The Hobbit. The teacher decided that since there is a piece from Tolkien, then you need to read the whole book. I say, "Sorry, guys," and cross it out. We tried to watch a movie based on the book, but the children didn't get it: they were just scared.

Then cross out all the books that the children know by heart. In the first grade, along with The Hobbit, we came across Little Red Riding Hood. I crossed out this book because we know it very well. Next, we select books that can be replaced with audiobooks and films. If the child is not drawn to reading Pinocchio, just show him the film. The plot will be postponed, and when the text from the book comes across to him in the textbook, the child will cope with it, because he will be six months or a year older.

Then choose the books you will read aloud. It was the same with Garin-Mikhailovsky's The Childhood of the Theme. My daughter got it in the second grade, and I realized that she would not pull it.

There remains a small sample of books that the child can read on his own. You take this list and say: “Look, here the teacher recommended these books. Which of these would be the most interesting for you to read?”. He chooses and you start reading. One summer, our son read one or two books, but at the very least, we replenished our cultural baggage. Often parents are afraid that they will come to school in September and they will be asked if the child has read the entire list. Just answer that you didn't read everything. There is nothing terrible in this.

What else to read about children's reading:

- Marina Aromshtam "Read!" - a book that will give parents answers to many questions.

- Yulia Kuznetsova Calculation. How to help your child love reading ”- a book about how parents can help children love books.

- Aidan Chambers “Tell me. We read, think, discuss” - the author tells how to communicate with children through books.

What questions can be asked to children so that they talk about what they read and at the same time do not feel that they are being examined ( an excerpt from the book read here ).

What questions can be asked to children so that they talk about what they read and at the same time do not feel that they are being examined ( an excerpt from the book read here ). - Daniel Pennack "Like a Novel" - for parents who are worried that their child does not read.

- Papmambuk - is an excellent site with useful materials about children's reading.

Listen to the full interview with Yulia Kuznetsova here. The conversation took place on the air of "Radio School" - the "Mela" project and the radio station "Moscow Speaks" about education and upbringing. The guests of the studio are teachers, psychologists, scientists and other experts. The program airs on Sundays at 4:00 pm on the radio "Moscow Speaking".

Illustrations: Shutterstock (oriol san julian, Kat Buslaeva)

How to get your child to read? - ABC of education

Is it possible to convince a child to read? Is it worth spending time talking about the benefits of reading, or is it better to force it hard? What should a parent do if they give up in despair because their child doesn't read and has a reputation for laziness at school? We talk about myths, stereotypes and mistakes of parents with child neuropsychologist Maria Chibisova.

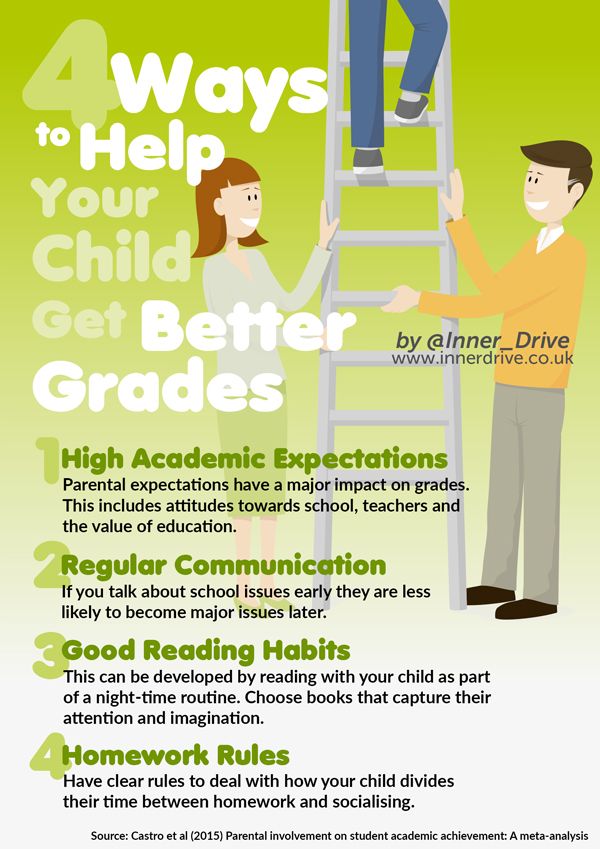

In the first grade, the child did not read well, with difficulty putting letters into words. Over time, the skill of reading developed, but neither at ten nor at fourteen years old does the child have the habit of reading. At the same time, everyone in the family has a higher education, everyone reads a lot and consider reading an inexhaustible resource and an extremely important skill. What to do?

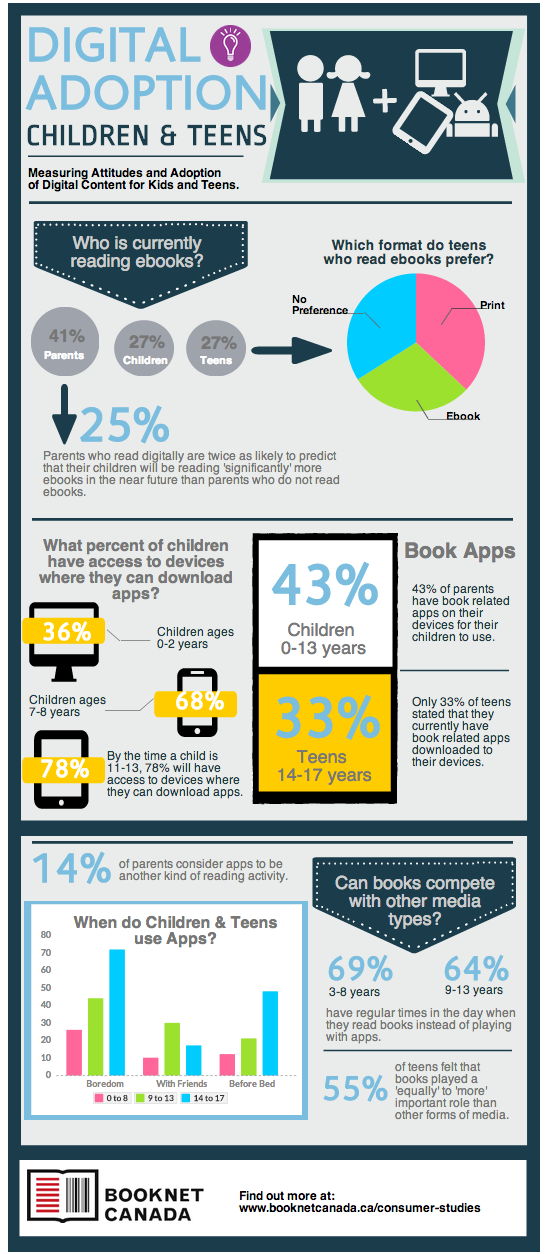

Reading books is good. But we must not forget and take into account the time in which we live. Today, information is perceived in a way that is different from what it was five to ten years ago. We used to read books, newspapers and magazines - this was the main way to get information. Today we get it through a computer and from the Internet. Therefore, the requirements of fathers and mothers regarding reading are often not entirely adequate and do not take into account the modern context. This is first.

Secondly, parents are often too emotional in their expectations. In annoying and strict conversations, expressions can slip through: “If you don’t read, you will grow up as a janitor ...”. By the forces of parents there is a substitution of meanings. Instead of "reading is interesting and great pleasure", we get: "reading is right, it is necessary."

In annoying and strict conversations, expressions can slip through: “If you don’t read, you will grow up as a janitor ...”. By the forces of parents there is a substitution of meanings. Instead of "reading is interesting and great pleasure", we get: "reading is right, it is necessary."

Expectations of this kind from relatives cause a child, first of all, tension, which gives rise to a complex of "conformity to expectations." The very fact of reading ceases to be a process for him and turns into a "fad". Reading, on the other hand, becomes a load, a voltage, and at the output it causes a protest.

That is why so many parents are faced with the fact that today's children have no interest in books at all, they do not perceive them.

But there is another side. Children have difficulty reading and get tired easily. Shouldn't they be forced to read so that a habit develops through regularity?

“How to make people read?” There shouldn't be such a wording. In this usage, you can immediately hear the negative connotation: reading is terrible, bad, difficult, and therefore you need to force it.

In this usage, you can immediately hear the negative connotation: reading is terrible, bad, difficult, and therefore you need to force it.

In fact, reading is one of the child's skills that can bring pleasure and is a positive moment in his life.

In general, there has been a tendency lately to escalate the situation not only around reading, but in general around teaching children, preparing them for school. Education began to take up too much time in a child's life, compared to how it used to be. Parents' emotions also increased in this regard. Emotions are very specific, which are imposed on the child: we want you to be an excellent student. Parents regularly transfer their own school experience, often negative, to the child. The process of schooling thus becomes very stressful. And reading here is the most telling example.

Many parents naively believe that if my child can read, he or she is ready for school. This is a huge mistake. And this is absolutely not true.

Why?

Reading and writing are the last things a preschooler should be able to do. The level of development of higher cognitive functions is primary: whether he is able to concentrate attention, how self-control and motivation are developed in him. This is no longer about game motivation, which still remains in the asset of any child by school, but about cognitive motivation. Is the child able, without any pressure from outside, on his own initiative and with natural interest, to sit and study something? Does he have the strength to do so?

Very often (before the first year of life) parents show the letters on the cards to the baby, hoping to teach him to read: “so small, but he will already know the letters!” But in fact, for parents, it is more the satisfaction of their ambitions than the natural needs of the child. Of course, he will not know anything, because purely physiologically at the age of one, the parts of the brain responsible for distinguishing signs, their retention and reproduction have not yet been formed. At best, if something succeeds, it is to develop a conditioned reflex.

At best, if something succeeds, it is to develop a conditioned reflex.

If a child develops harmoniously from the first years of life, if parents are attentive to the course of the process of his development, attentive to his needs in this development and give the child what he needs and is important at each specific period of life, then reading will appear by itself and problems will not occur with him.

How many examples we see when children themselves learn to read. Usually this happens at five or six years old, sometimes even at four. They begin to show interest in letters, in inscriptions on the street, they quickly grasp and remember. And for this you do not need to organize any special process. The emergence of this interest is a sign of the physiological formation of the brain, preparedness for the perception of this information. But in no case should you immediately load the child: oh, you started reading, now you will do it every day with us, like lessons. Reading should not turn into a "compulsory". It should be a pleasant pastime in which the child achieves success, an exciting game. The tasks that a parent sets for a child should be based not on expectations, but on opportunities.

It should be a pleasant pastime in which the child achieves success, an exciting game. The tasks that a parent sets for a child should be based not on expectations, but on opportunities.

It is even more impossible to force a child to read. Any violence always has consequences. At a minimum, reading will not be a voluntary and natural process. In the matter of reading, there must definitely be freedom. The child should enjoy reading. After all, reading is an occupation that, by definition, cannot but be liked. We must arouse interest in this process, support and help overcome difficulties. The main question that parents should face is not “how to force?”, But “how to help in reading?”

There is an opinion that if a child sees a parent with a book, he will certainly read it.

Not necessarily, but the proportion of probability does increase. If a child sees from an early age that a book is a common and necessary item in the house, everyone uses it, that through the book he himself receives positive emotions, the likelihood that he will continue to want to receive these emotions is very high.

If no one in the family reads, and parents demand from the child what they do not do themselves, then reading can become a field of resistance and war between the child and adults. The attitude towards reading should be normal, not strongly emotionally charged and rather positively colored.

If parents are engaged in their own development, and the child observes this, if he sees that father and mother are interested in a lot of things, including reading, reading for them is not hard work, but easy and pleasant leisure, then children are emotionally fed from this .

When a child is small, we are ready to be indulgent about the lack of interest in reading. But I would like the child to read after reaching a certain age, 10-14 years old, and the initiative would come from him, so that he would take the book himself. And it happens differently. The initiative does not come from one child, but it does come from another, but preference is given to literature not according to age: comics instead of the novel. With what it can be connected?

With what it can be connected?

Let's start with the older ones. Fourteen years is adolescence, when a person’s motivation is no longer cognitive at all. At this age, children usually begin to study worse and lose interest in learning. It's okay. It is not necessary to expect that the child's interest in books will be more and sincere than in communication. If the child develops normally, then he will prefer communication with peers to books. But if at the age of fourteen he sits with a book, then this rather indicates that he is leaving for his own world and, perhaps, is incompetent among his peers and in communications.

Children aged 8-11 are a completely different story. This is the most learning age. Leading activity, that is, training, they should be normal. And here parents want their child to read serious books. What does it say? Only about their own ambitions: look at what a developed child we have, what an educated and intelligent family we have.

There is nothing wrong with comics. On the one hand, it is fashionable and accepted among peers, on the other hand, it is simple: large text, colorful pictures, no effort is needed.

On the one hand, it is fashionable and accepted among peers, on the other hand, it is simple: large text, colorful pictures, no effort is needed.

Of course, not the last role in reading (and interest in simply looking through comics) is played by difficulties of a physiological nature. Today, in many children, we observe precisely functional difficulties. As a rule, they are the result of a lack of attention, and severe fatigue, and difficulties in mastering the motor program.

In children who did not crawl until a year old, or crawled a little, writing and reading difficulties are found over time. During crawling (motor development), a motor program is assimilated when we learn how to put small elements into larger ones. Sounds into syllables, syllables into words, words into sentences. The basis of this process is the assimilation of the motor program.

Speech difficulties have also become common: children speak late and do not speak well. And poor pronunciation often turns into dyslexia, dysgraphia. When the process of literature itself is difficult for a child, this is a signal. . Why is it so? Parents must answer. If you do not deal with the child, do not compensate for the difficulties, do not study enough, then the probability of subsequently detecting difficulties in reading is 100%. Reading is the same process as speech, only more complex. While reading, we do not just acquire auditory images, but connect auditory images and visuo-letter ones. No wonder children refuse to read. What is hard to do, you don't want to do. What is easy, interesting and enjoyable, brings the child some kind of childish benefit - is positively fixed in the mind. The child is ready to return. It is useless to say: it will come in handy, it will be useful. You can, of course, say this, but it is naive to hope that this will influence and rebuild the child's view. Until the child himself really gets the benefits and benefits (of his nursery) from this, he will not understand all the benefits of reading.

When the process of literature itself is difficult for a child, this is a signal. . Why is it so? Parents must answer. If you do not deal with the child, do not compensate for the difficulties, do not study enough, then the probability of subsequently detecting difficulties in reading is 100%. Reading is the same process as speech, only more complex. While reading, we do not just acquire auditory images, but connect auditory images and visuo-letter ones. No wonder children refuse to read. What is hard to do, you don't want to do. What is easy, interesting and enjoyable, brings the child some kind of childish benefit - is positively fixed in the mind. The child is ready to return. It is useless to say: it will come in handy, it will be useful. You can, of course, say this, but it is naive to hope that this will influence and rebuild the child's view. Until the child himself really gets the benefits and benefits (of his nursery) from this, he will not understand all the benefits of reading. That is why it is important that the reading process is positively colored. Be sure that then the child will prefer to use this method of obtaining information again.

That is why it is important that the reading process is positively colored. Be sure that then the child will prefer to use this method of obtaining information again.

And if not physiology, then what else can be connected with the refusal of children to read, for example, poetry, voluminous novels?

We live in the era of the computer and TV. Information is given and received in a primitive and easy way. This way of perceiving information is a passive way. Everything is immediately provided to a person in a chewed form. It does not require any additional voltage. Take care of everything. The brain quickly learns to work on reduced energy consumption, not to overstrain. Reading is a process during which a person engages many higher mental functions.

But it is impossible to categorically dismiss everything: a computer, the Internet, a TV set, because sooner or later you will have to face the fact that “forbidden fruit is sweet”. Dissatisfaction due to prohibitions, incompetence among peers can already cause new problems. Parents should be able to be flexible and understand that they are free to prompt and guide the child here, offering, for example, educational computer games.

Parents should be able to be flexible and understand that they are free to prompt and guide the child here, offering, for example, educational computer games.

So we are degrading?

Well, not in that sense. But the fact that a computer or TV tires and overexcites the nervous system, but at the same time does not develop it and the brain, is a fact.

If we talk about the language, it really has become simpler. And it's getting harder and harder for kids to comprehend poetry. In addition, rhythmic organization plays an important role. If, for example, a child was not read much poetry in childhood, then the child will not have an interest in them, it will be difficult for him to perceive this genre even in middle age.

Therefore, start reading good poems to your child as early as possible, so that he wakes up with the pleasure of the sound of words, rhymes, and their understanding. Engage in his cognitive development. Play games for attention, reaction, memory, developing spatial thinking, fine and gross motor skills, etc.