How did lewis hine change child labor

How Photography Ended Child Labour in the USA

Gina Mussio

28 October 2016

Photography is a powerful art form. It’s caused us to change the way we view things and continues to change what we know to be true. Lewis Hine might be one of the form’s greatest actors for change: through his work the American photographer has changed American consciences, using his camera as a tool to document the harsh conditions of American workers, particularly children – and ultimately bringing about reform in U.S. child labor laws.

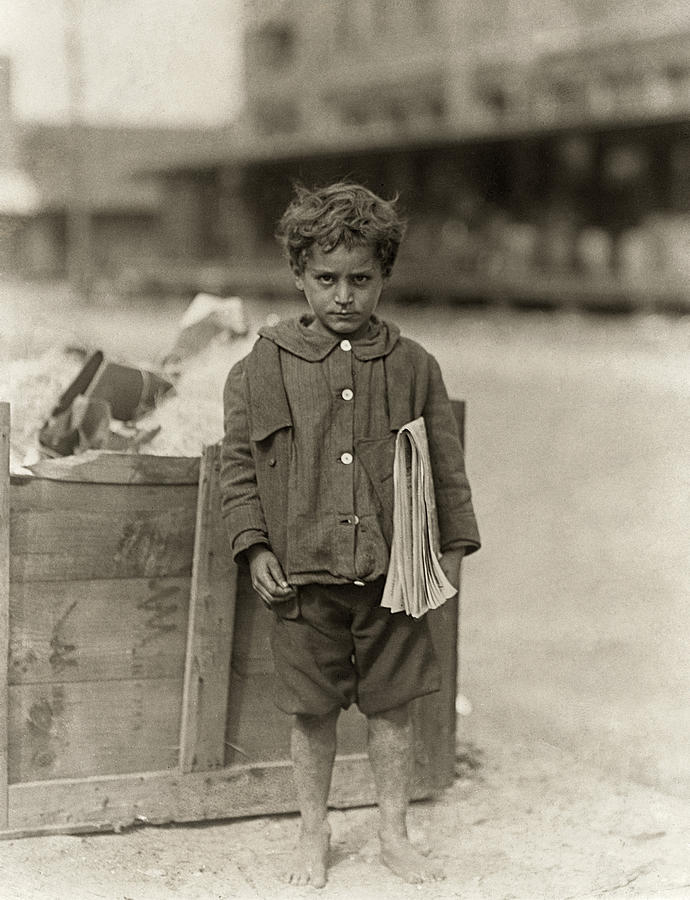

Lewis Hine, ‘Maud and Grade Daly, five and three years old, shrimp pickers, Bay St Louis, Mississippi | Courtesy of Library of Congress

Born in 1874 in Wisconsin, Hine didn’t start off as a photographer. After his graduation from the University of Chicago in 1901 he taught botany and nature studies at the Ethical Culture School in New York City. It was there, after a colleague suggested he use photography as a tool for his classes, that Lewis Hine as a photographer was born.

With a constant interest in social welfare and reform movements, Hine was particularly drawn to the conditions of immigrants in the United States. In 1905 he began his first documentary series on immigration, focusing on the waves of newly arrived immigrants at Ellis Island. He photographed this ‘new immigration’, the recent influx of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, from 1904 until 1909. The families that left Ellis Island and poured into cities, factories and farms heavily influenced his subsequent work in child welfare and the social conditions of the American working class.

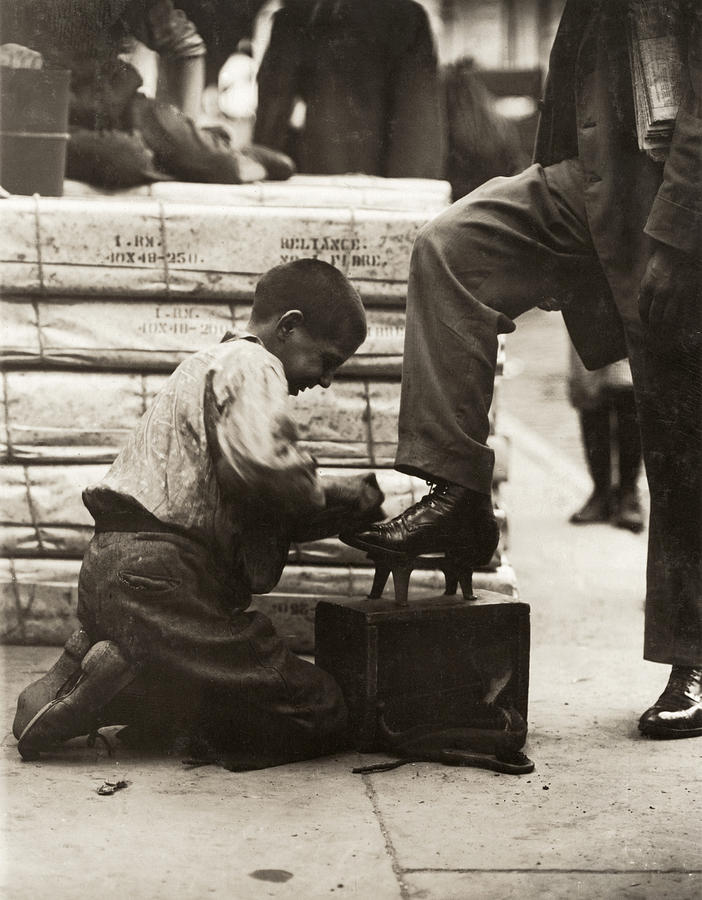

Often photographers and photojournalists find a cause to support with their photography, Lewis Hine found photography to support his cause. Hine traveled the country, taking pictures of children working in factories, mines, farms, and shops. He interviewed and photographed children working as newsboys, sales ‘men’ and seafood workers.

Lewis Hine, Group of Breaker Boys | Courtesy of UMBC Photographers & Collections Index

He was a good teacher, used to working with children, and gained their trust quickly. If a child didn’t know his or her age or refused to give it, he surreptitiously measured their height using the buttons on his vest and calculated the age accordingly.

If a child didn’t know his or her age or refused to give it, he surreptitiously measured their height using the buttons on his vest and calculated the age accordingly.

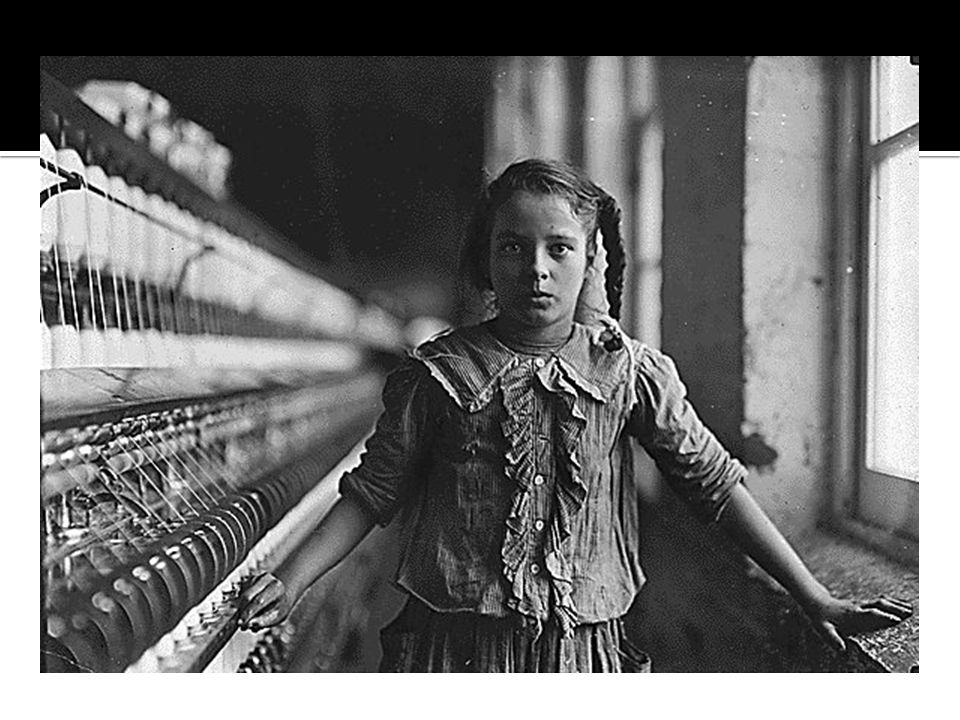

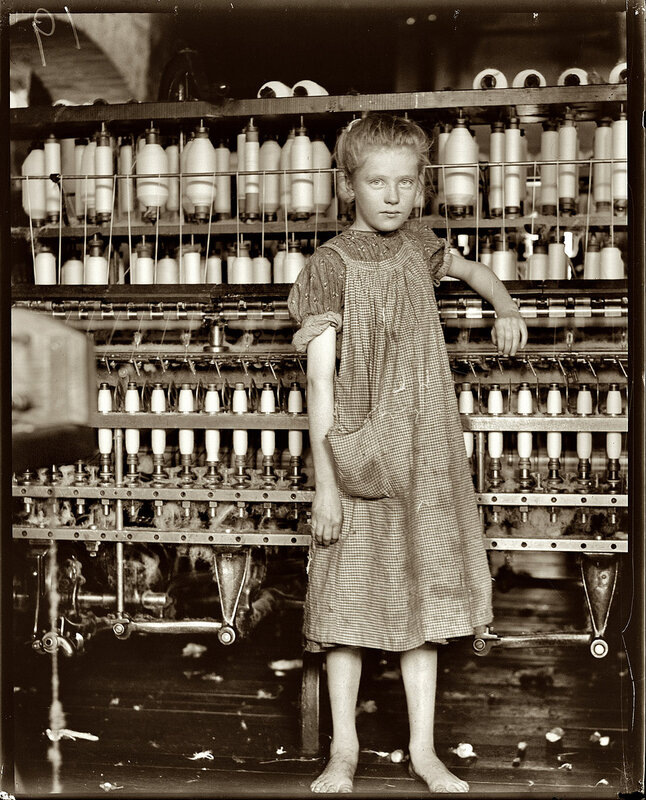

In one photo caption of a young girl with two pig-tailed braids looking straight at the camera, Hine wrote: ‘One of the spinners in Whitnel Cotton Mill. She was 51 inches high. Has been in the mill one year. Sometimes works at night. Runs 4 sides – 48 cents a day. When asked how old she was, she hesitated, then said, ‘I don’t remember’, then added confidentially, ‘I’m not old enough to work, but do just the same’. Out of 50 employees, there were ten children about her size’. Another photograph, taken in Jersey City, New Jersey, shows a small body crumpled across two stairs, newspapers being used as a makeshift pillow; a young newsboy is taking a break for some sleep.

In 1910 there were approximately two million children under the age of 15 working in the U.S. But by the early 1900s child labor was beginning to be seen by many as child slavery. Hine said, ‘There is work that profits children, and there is work that brings profit only to employers. The object of employing children is not to train them, but to get high profits from their work’.

Hine said, ‘There is work that profits children, and there is work that brings profit only to employers. The object of employing children is not to train them, but to get high profits from their work’.

Lewis Hine, Seven year old Rosie, oyster shucker, Bluffton, South Carolina, 1913 | Courtesy of Library of Congress

Hine’s documentary project and passion for reform continued to grow and in 1908 he quit teaching to work as an investigative photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), an organization established to abolish child labor. Hine was one of many photographers hired by the organization to investigate and gather evidence of the squalid conditions many children worked in. His photos formed exhibitions, were made into slides for lectures and printed in magazine articles and pamphlets, directly influencing the state of children in the U.S.

Eventually these efforts led the Children’s Bureau to be transferred to the Department of Labor, an important step in the fight against child labor. Finally in 1916 Congress passed the Keating-Owens Act, establishing a minimum age of 14 for workers in manufacturing and 16 for workers in mining and an eight-hour workday maximum, among other things. Unfortunately this law was deemed unconstitutional in that congressional control of interstate commerce did not control conditions of labor. While it was a blow to the child labou movement, by 1920 the number of child workers was nearly half of that in 1910.

Finally in 1916 Congress passed the Keating-Owens Act, establishing a minimum age of 14 for workers in manufacturing and 16 for workers in mining and an eight-hour workday maximum, among other things. Unfortunately this law was deemed unconstitutional in that congressional control of interstate commerce did not control conditions of labor. While it was a blow to the child labou movement, by 1920 the number of child workers was nearly half of that in 1910.

Lewis Hine, Child Labourer | Courtesy of Library of Congress

Hine continued to work for social reform over the years, photographing for sociological studies, magazines and for the American Red Cross in Europe right after World War I. In 1926 he went back to Ellis Island to update his record, observing and documenting what reforms had and had not been made.

Hine once said, ‘There were two things I wanted to do. I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected; I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated’. His records of child laborers were stark proof of what needed to be corrected and his following project sought to bring out the dignity in work. He spent all of 1930 documenting the construction of the Empire State Building, taking hundreds of photos of the workers and work conditions. In 1932 he compiled his records into an exhibition and a book titled Men at Work.

His records of child laborers were stark proof of what needed to be corrected and his following project sought to bring out the dignity in work. He spent all of 1930 documenting the construction of the Empire State Building, taking hundreds of photos of the workers and work conditions. In 1932 he compiled his records into an exhibition and a book titled Men at Work.

By that point, interest in Hine’s work was dying down, his age and individuality working against him in his later years. While many of his submissions were rejected, Hine kept at it, still using his art to raise questions and fight for social reform. In 1939, a year before his death, Hine found renewed respect for his social photography with a large exhibition of his work at the Riverside Museum in New York and in the 1980s the NCLC created the Lewis Hine Award to honor the investigative photographer. Still today the award is given annually to ten recipients for their extraordinary service to young people.

Today Hine’s work, a collection of more than 5,100 photographs and 355 glass negatives, are housed in the Library of Congress. Hine’s photographs were instrumental for the state of American workers and American children, ultimately helping to reform the child labor laws in the U.S. His use of free speech and free press influenced and awakened Americans’ consciences, effectively proving that the camera can be a powerful tool to promote social change.

Hine’s photographs were instrumental for the state of American workers and American children, ultimately helping to reform the child labor laws in the U.S. His use of free speech and free press influenced and awakened Americans’ consciences, effectively proving that the camera can be a powerful tool to promote social change.

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel – and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way.

That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Epic Trips, Mini Trips and Sailing Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travellers and friends who want to explore the world together.

That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Epic Trips, Mini Trips and Sailing Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travellers and friends who want to explore the world together.Epic Trips are deeply immersive 8 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and enough down time to really relax and soak it all in. Our Mini Trips are small and mighty - they squeeze all the excitement and authenticity of our longer Epic Trips into a manageable 3-5 day window. Our Sailing Trips invite you to spend a week experiencing the best of the sea and land in the Caribbean and the Mediterranean.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm – and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet.

That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.Children in the machine | Europeana

Blog post

Lewis Hine's photography and child labour reform

by

Adrian Murphy (opens in new window) (Europeana Foundation)Pioneering photographer Lewis Hine's images of industry and labour led to reform and changing laws.

Born in 1874, Lewis Hine was initially a teacher and sociologist. In the early 1900s, Hine led his sociology classes to Ellis Island, photographing some of the thousands of immigrants arriving there.

RELATED: Exhibition: Leaving Europe - a new life in America

Through these photographs, Hine began to realise that documentary photography could be a tool for social change and reform.

In 1907, Hine was the staff photographer of the Russell Sage Foundation for whom he photographed people and life in steel-making districts of Pittsburgh.

One year later, he became the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee, leaving his teaching position.

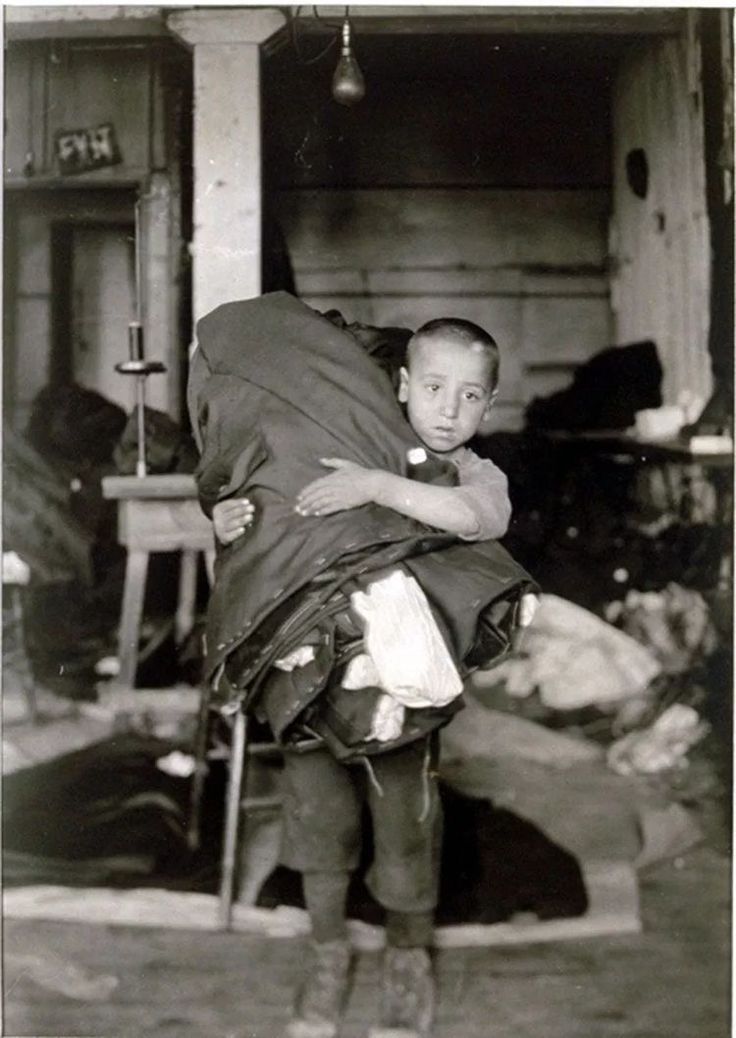

Over the next decade, Hine photographed industrial conditions, revealing the extent to which children worked in the mills, mines, canneries and factories of the United States. Children from poor and migrant families, as young as five years old, were working long hours in dangerous and dirty conditions.

In many cases, photography was forbidden in mines and factories. These were scenes that weren’t meant to be seen; revealing these conditions was met with considerable opposition.

Hine adopted many personas - fire inspector, postcard vendor, bible salesman - so he could be allowed in, and travelled hundreds and thousands of miles taking almost 5,000 photographs.

Girl Carrying Homework thro Greenwich Village, Lewis Hine, Rijksmuseum, Public Domain Mark

These photographs supported the Committee's lobbying to end child labour, and inspired a wave of moral outrage. By 1912, a Children's Bureau in the Department of Labor and Department of Commerce had been created, following NCLC's lobbying. Finally, in 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed bringing child labour to an ultimate end.

By 1912, a Children's Bureau in the Department of Labor and Department of Commerce had been created, following NCLC's lobbying. Finally, in 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed bringing child labour to an ultimate end.

RELATED: Exhibition: Industrial Photography in the Machine Age

Lewis Hine's photographs were instrumental in changing child labor laws in the United States. His photographs - whether of children working, migrants at Ellis Island or wider industrial conditions - emphasise the human side of modern industry and remain powerful today.

Europe at Work - Share your story

When you were a child, did you have to work? Share your story and help us tell the story of Europe through our working lives in the past and the present.

This blog post is a part of the Europeana Common Culture project, which explores varied aspects of our shared cultural heritage across Europe.

Child labor through the eyes of Lewis Hine

Childhood Lewis Hine worked in a factory. After saving money for his studies, he became a sociologist, receiving education at the Universities of Chicago and New York. Then he taught at the School ethical culture by taking pictures of their own students. With them he visited Ellis Island, where hundreds of thousands of migrants arrived on steamboats. On the in his first pictures we see people who have just arrived in the crucible of the New World. Their poverty, confusion, and unrealizable hope for a better future - for themselves, Or at least for their children. New Americans - new American workers.

After saving money for his studies, he became a sociologist, receiving education at the Universities of Chicago and New York. Then he taught at the School ethical culture by taking pictures of their own students. With them he visited Ellis Island, where hundreds of thousands of migrants arrived on steamboats. On the in his first pictures we see people who have just arrived in the crucible of the New World. Their poverty, confusion, and unrealizable hope for a better future - for themselves, Or at least for their children. New Americans - new American workers.

From these pictures the history of social photography of the twentieth century begins, but they drew upon themselves attention back then, a hundred years ago. Hine filmed steel workers and families poor people from the Jewish-Slavic ghettos. In the twenties he performed the famous a series of "working portraits", taking pictures of people of different professions. And in the thirties captured the construction of the Empire State Building, the tallest building of its time, which was erected by European migrants and Indian assemblers from Mohawk reservations. Photo of migrant workers sitting on construction beams, shaking his feet over the abyss, has become one of the symbols of this era.

Photo of migrant workers sitting on construction beams, shaking his feet over the abyss, has become one of the symbols of this era.

Before the end of his days, Lewis Hine photographed working people - until he died in poverty, losing her apartment and living on welfare. But the most famous of his photographic projects dedicated to the work of small American workers. In 1908 Hein becomes staff photographer for the US National Child Labor Committee - NCLC. This public organization, created with the support of the class Trade Union "Industrial Workers of the World", began the first in the history of the United States campaign to limit and ban child labor in the industrial production. The work of children was then the daily norm. Thanks to low wages, it brought high profits, and was actively used in all industrial sectors. There were plants and factories, entirely staffed by child workers, and a number of large companies openly used minors as the main contingent of the labor force at their enterprises. The exploitation of child laborers was habitual as for the capitalists, as well as for the children themselves, and was carried out with the full consent of their own parents. Fathers and mothers had no choice - but there was a constant the need for an extra penny for a piece of bread. Working hands, even the most small and weak, had to feed their own "extra" mouth. And a child from a working-class family started working as soon as possible employment.

The exploitation of child laborers was habitual as for the capitalists, as well as for the children themselves, and was carried out with the full consent of their own parents. Fathers and mothers had no choice - but there was a constant the need for an extra penny for a piece of bread. Working hands, even the most small and weak, had to feed their own "extra" mouth. And a child from a working-class family started working as soon as possible employment.

Child labor was obvious reality - but only until the campaign for his cancellation. US public opinion: professors, priests, financiers and popular writers - flatly refused to believe in mass industrial exploitation of American children. They were ready to admit only special cases illegal use of child labor - which, in their opinion, not only were a negative phenomenon, but, on the contrary, contributed to the mental and physical development of young workers. Legislative prohibition of labor activities up to the age of 16 would have a significant impact on income industrial monopolies.

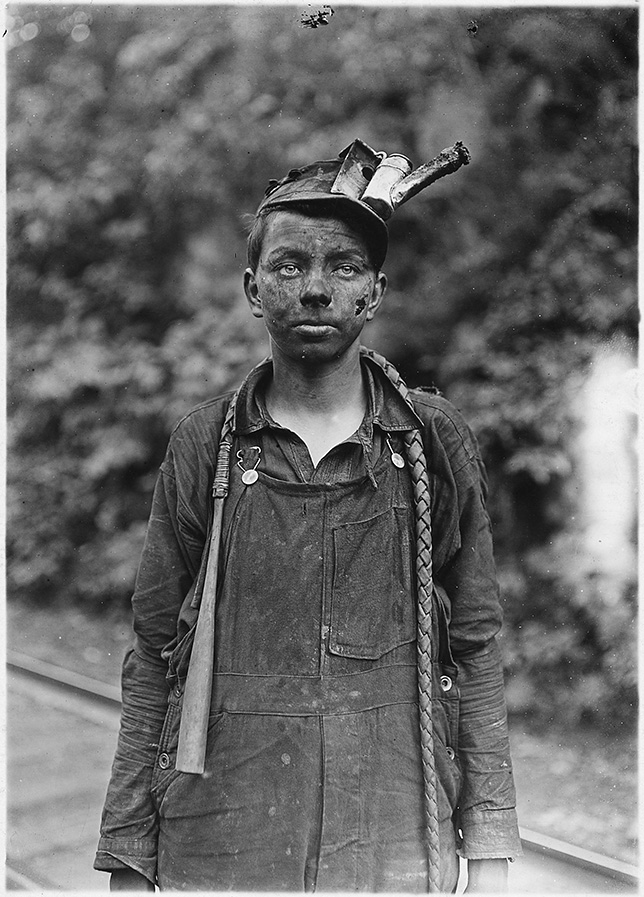

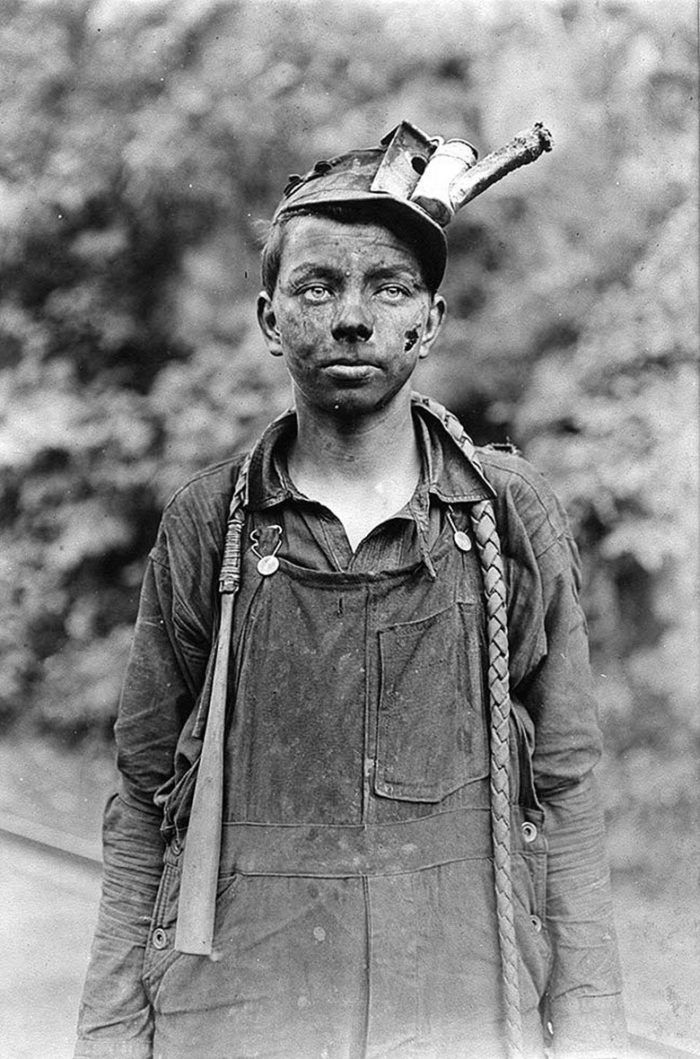

From 1908 to 1912 Lewis Hine travels across the US, from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast. He films underage workers who wouldn't fit the word "child" - miners, weavers, port loaders, stokers, laborers, cleaners. He photographs them at their workplaces and at work. He was threatened beaten, lynched, refused to be allowed into the factories, forcibly expelled for territory of workers' settlements. His photographs were feared - published on the strips newspapers and magazines, they told the truth about America's child labor.

There are many of these pictures. Some of them have concise accompanying captions made by Hine himself:

- “Loader Owens. 12 years. Can not read. Doesn't know the alphabet. He says: “Yes, I want to study, but I can’t, that’s all busy time with work. Has been working at the factory for 4 years.

- "One of the textile workers factories. Sometimes works at night. Does all the work - for 48 cents a day. Answering about her age, she hesitates, says: "I don't remember. " Then says: "I'm not old enough to work, but I do it as well as adults." From fifty workers here ten children of her age.

" Then says: "I'm not old enough to work, but I do it as well as adults." From fifty workers here ten children of her age.

Focused faces, stiff postures. Lewis Hine called his portraits "the gallery of the lost generation". famous shot "Vision", depicting a little girl who turned away from the weaving machine to the factory window, became a symbol of the selected, converted into capital childhood. Over time, this photo will turn into a symbol of the fight against child abuse. labor.

Ukrainian migrant children were like that too. Them terrible work succinctly depicts the study of Julian Bachinsky, published in Lviv at 1914th year:

“Rocks are practical, as they are officially respected in In the United States, as a rule, small children, є litas from 14 to 16 years. However for the children of immigrants, the norms do not have an exclusive force. Immigrants are trying beruchi zagalom, hang z-pіd tsієї norms, and soon, less here, in yakіy you can afford to give your children a job before the 14th fate of life, and then not less at 13 or 12 rokiv, ale y at 10 and 9, of course, at great Skoda physical and spiritual development of the child..jpg) Robots, before which small children are taken I earn a living, dearly. Vzagali, take up to all possible robot...”.

Robots, before which small children are taken I earn a living, dearly. Vzagali, take up to all possible robot...”.

Describing the labor of American children miners of Ukrainian origin, Bachinsky writes:

between vugillya stone. In long rows to sit stench one on the other over rolls and sort out the vugillya, which zsovuєtsya down, and wiggle z-pomіzh new stone. Tse heavy work and dressing, especially in mountainous surfaces "brehi" (conveyor), deviate stones between coarse stones vugіllya, there they often grind their fingers to the point of blood. Quietly "nonsense" send relatives of children, zvichayno, in 12 years of life, even if you want i at 10, and navit i at 8 rokiv. Date of payment of the day - due date until late: 11- і 12-year-olds are 50 and 60 cents, 13-14-year-olds - 75 and 90 cents. working day trivaє 9, decoudi 8 years.

These little miners can be seen on Hein's photographs. The latest Ukrainian edition of Bachinsky's book illustrates it was his picture - a photograph of children on a stone cutter of a coal conveyor.

Since then many decades, but the labor exploitation of children is still flourishes. Back in the middle of the last decade, at the international trade union conferences during the World Day of Protest Against Child Labor, the total number of children working on the planet was announced. There are at least 246 million - aged 5 to 17 years. About 179million - every eighth child in the world - are subject to the worst forms of child labour, which "threatens their physical, mental and moral health."

We can see the extent of child labor in market Ukraine. Study, conducted by the International Labor Organization, the State Statistics Committee and the Ministry of Labor, found 416 thousand children (156 thousand girls and 260 thousand boys), regularly employed in various types of work. At least a quarter of that numbers represent children aged 7-12 whose work prohibited by law. Every second child works in unfavorable conditions, a quarter of 7-12 year olds do hard physical work, and 18% of minors work requires increased mental stress.

Parents are usually calm to the labor of their own children - although two-thirds of their sons and daughters have an unsatisfactory or poor health. After all, they are forced to work by economic reasons, and only 14% of children are engaged in it "in order to acquire a labor experience." 82% of young workers were hired only by oral agreements, and a third of the total number of children employed in the labor force Ukraine receive a salary produced products - or do not receive it at all.

Child labor filmed in our time - on digital cameras and high-speed film, fixing shades of color. But as long as this situation continues, our world will remain black and white - as if in a photo of Hine.

Horrible child labor conditions in Lewis Hine's photographs Hine has become a symbol of the fight against the exploitation of child labor in factories and factories in the United States. After all, he knew this world like no one else: after the death of his father, Hine went to work in a factory in order to earn money for training.

In 1908 Hine was hired by the US National Child Labor Committee to work as a photojournalist. His published series of photographs shocked America because the use of child labor and its conditions were carefully hidden from the public. Working for the committee turned out to be really dangerous - the photographer, whose work showed the horror of life and the conditions in which children were kept, was threatened with physical violence and even death. Therefore, Hine entered the factories under any pretext that seemed convincing enough to the police or the guards. Often he posed as a fire inspector, a postcard and bible salesman, and an industrial photographer. His efforts were not in vain - a law was passed to protect the rights of working children.

Hine also documented the lives of immigrants, spoke about the work of the American Red Cross in Europe during the First World War, and took the famous series of photographs about the construction of the Empire State Building skyscraper. True, the famous photographer did not wait for a response of gratitude from the American society and the government - he died after an operation in a New York hospital for the poor.

True, the famous photographer did not wait for a response of gratitude from the American society and the government - he died after an operation in a New York hospital for the poor.

To this day, Hein's photographs are popular as a symbol of that era. His work still causes pain and shame that such a thing could ever happen in our history. And recently for Time magazine, photo editor Sanna Dallaway colorized Lewis Hine's most famous and significant works.

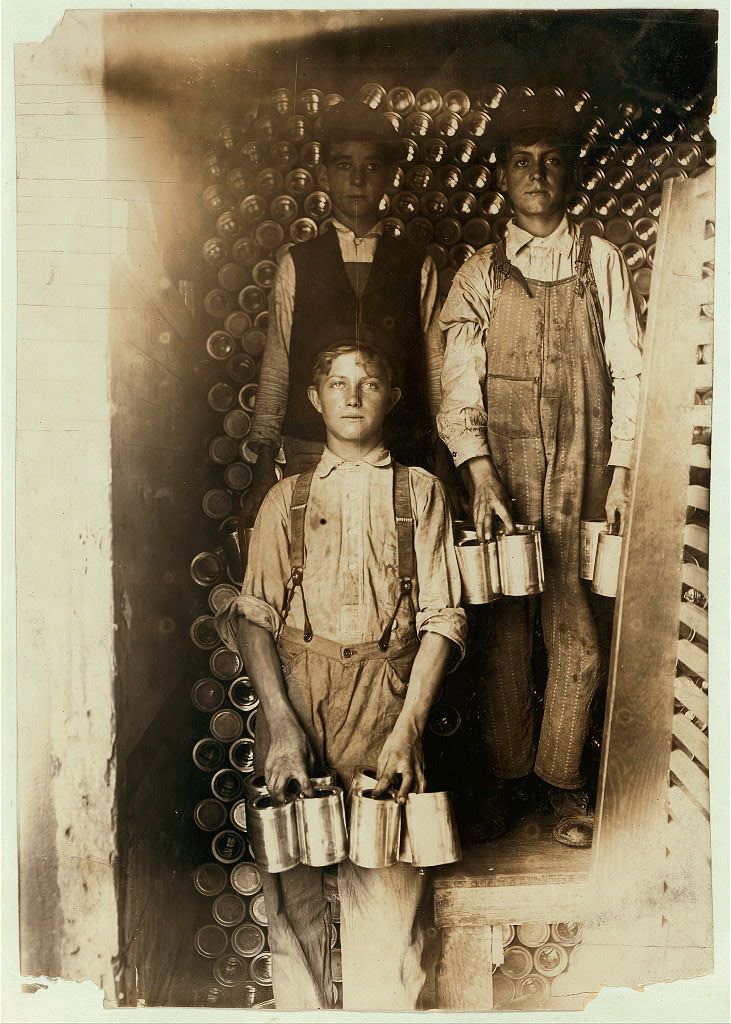

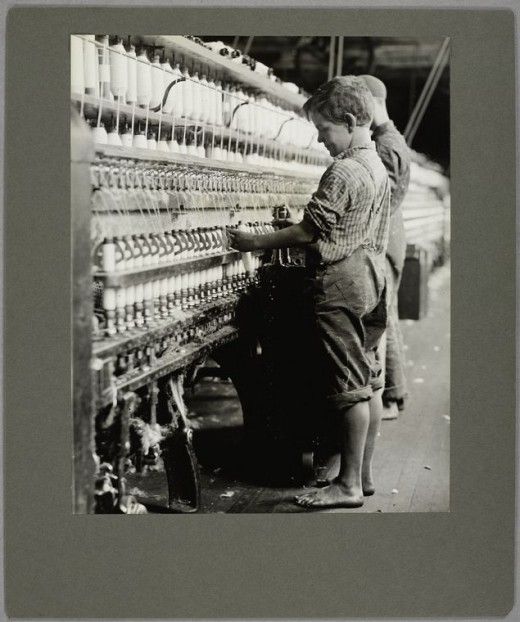

Jewel and Harold Walker, 6 and 5 years old. Up to 11 kg of cotton is harvested every day. 1916 Comanche County, Oklahoma. Photo in color. Coal crushers at Pennsylvania Coal Co.'s Ewen Breaker plant. in Pittston, Pennsylvania, 1911. A black school in Kentucky, 1916. Only a third of the students are present at the lesson, since, according to the teacher, the rest work on tobacco plantations. Workers at the Seaconnet Mill textile factory. Photographer Lewis Hein recorded the stories of the heroes of his work. He noted the height and age of working children, as well as education. In this photograph, none of the boys could read or write. Sadie Pfeiffer, 121 cm, works at Lancaster Cotton Mills for six months, 1908 year. Julia stays at home with the younger children. Other children, older ones, work in the factory. 1911 Bayou La Batre, Alabama. Lunch break at the Economy Glass Works in Morgantown, West Virginia, 1908 Textile Mill Bibb Mill No. 1. Some of the boys were so small that they had to climb onto a winder to connect broken threads. Macon, Georgia, January 1909. 7-year-old Fanny, 121 cm tall, with her sister at a factory in Elk Mills. Her older sister said that Fanny helps her a lot, although not all day. The sisters start working at 6 o'clock in the morning. In their family 19children. The boy works at the J.S. cannery. Farrand Packing Company in Baltimore, Maryland, July 1909. 11-year-old boys who earn between two and four dollars a week, including working at night. Newspaper sellers, St. Louis, 1910 All three smoke. 15-year-old Frank Weigel fell asleep on an 18-hour shift and as a result received a work injury - the fingers that fell into the machine were amputated.

In this photograph, none of the boys could read or write. Sadie Pfeiffer, 121 cm, works at Lancaster Cotton Mills for six months, 1908 year. Julia stays at home with the younger children. Other children, older ones, work in the factory. 1911 Bayou La Batre, Alabama. Lunch break at the Economy Glass Works in Morgantown, West Virginia, 1908 Textile Mill Bibb Mill No. 1. Some of the boys were so small that they had to climb onto a winder to connect broken threads. Macon, Georgia, January 1909. 7-year-old Fanny, 121 cm tall, with her sister at a factory in Elk Mills. Her older sister said that Fanny helps her a lot, although not all day. The sisters start working at 6 o'clock in the morning. In their family 19children. The boy works at the J.S. cannery. Farrand Packing Company in Baltimore, Maryland, July 1909. 11-year-old boys who earn between two and four dollars a week, including working at night. Newspaper sellers, St. Louis, 1910 All three smoke. 15-year-old Frank Weigel fell asleep on an 18-hour shift and as a result received a work injury - the fingers that fell into the machine were amputated.