How common core is slowly changing my child

How Common Core is Slowly Changing My Child

A Letter to Commissioner King and the New York State Education Department:

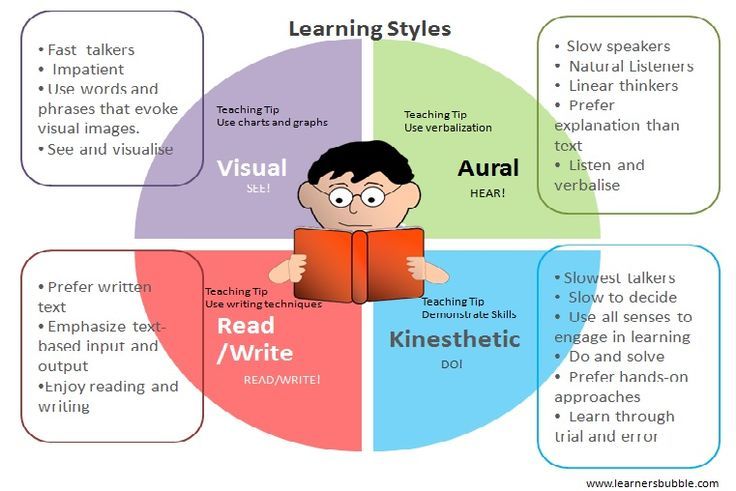

I have played your game for the past two years. As an educator, I have created my teaching portfolio with enough evidence so I can prove that I am doing my job over the course of the school year. I am testing my students on material that they haven’t yet learned in September, and then re-testing them midway through the year, and then again at the end of the year to track and show their growth. Between those tests, I am giving formative assessments. I am taking pictures of myself at community events within my district to prove that I support my school district and the community. I am teaching using the state-generated modules that you have created and assumed would work on all students, despite learning style, learning ability, or native language. I am effectively proving that I am worthy of keeping my job and that my bachelors and masters degrees weren’t for naught. I have adapted, just as all teachers across the state have, because that’s what we do. We might not agree, we might shake our head at the amount of time creative instruction has turned into testing instruction, but we play the game.

Today, things got really personal. Today I saw just how this Common Core business is affecting kids. Not my kids in my classroom; I know how it’s affecting them and I am doing the best that I can to make this as painless as possible on them. Today, my third grade son came home an angry, discouraged kid because of school. On the contrary, my oldest son is doing pretty well with the Common Core. He’s had some difficulties, but for the most part he’s just rolling with it and we’re doing OK. But my younger son is not my older son; which just proves that this one-size-fits-all curriculum that you are throwing at these elementary kids is bull.

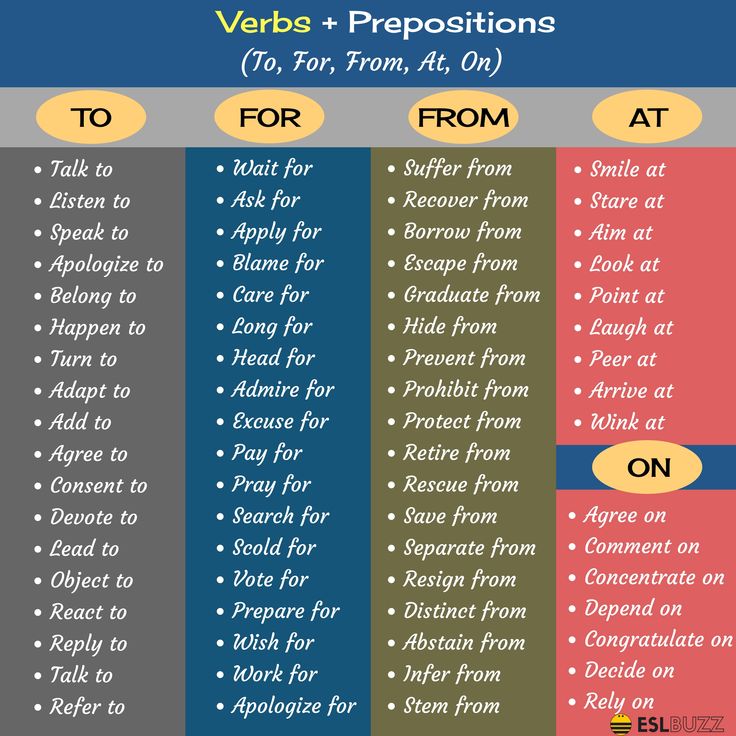

That’s right, NYS, I call bull. When my eight year old boy, who loves to read to his little sister and is excited to go to back to school come July of every summer, calls himself dumb because he is bringing home failing test grades, then this has turned personal. My son isn’t dumb, Commissioner King. He works hard to learn, he writes stories and songs, builds entire football stadiums out of Legos in record time, and he can explain how to divide in his own words. He. Is. Not. Dumb. But when he gets consistently failing grades on the module assessments, what message do you think he’s getting? These module assessments, sir, that have words like ‘boughten’ on them and the children have to infer what ‘boughten’ means. Did you know that boughten is no longer used as a form of the verb to buy? According to the grammarist.com website, boughten is as foreign to modern language as the word thou.

My son isn’t dumb, Commissioner King. He works hard to learn, he writes stories and songs, builds entire football stadiums out of Legos in record time, and he can explain how to divide in his own words. He. Is. Not. Dumb. But when he gets consistently failing grades on the module assessments, what message do you think he’s getting? These module assessments, sir, that have words like ‘boughten’ on them and the children have to infer what ‘boughten’ means. Did you know that boughten is no longer used as a form of the verb to buy? According to the grammarist.com website, boughten is as foreign to modern language as the word thou.

“Boughten is an archaic participial inflection of the verb to buy. It was once a fairly common colloquial form—it was used to describe something bought instead of homemade—and it still appears occasionally, but it is widely seen as incorrect and might be considered out of place in formal writing”

So, when my son is faced with answering questions on outdated language, on topics such as a ‘sorrel mare’ and the reading passages take place in foreign war-torn lands, when these children haven’t even mastered the basics of their own country yet, what do expect him to feel like? Do you expect him to feel like he’s just on the road to become college and career ready, which is the basis of the common core, and these challenges will only make him stronger?

No, sir, I’ll tell you what it does. It beats him down. It discourages him. It exhausts him. It makes him dread going to school and then lash out in anger at the nightly homework that is associated with these common core modules. It is turning him off of school and if this trend continues, he will be far from college and career ready because he will want nothing to do with college.

It beats him down. It discourages him. It exhausts him. It makes him dread going to school and then lash out in anger at the nightly homework that is associated with these common core modules. It is turning him off of school and if this trend continues, he will be far from college and career ready because he will want nothing to do with college.

I understand that we want to compete globally in the area of education. High school and college students should absolutely be challenged and learn to become a valuable, contributing member to their chosen career. Attributes such as creativeness, leadership, self-directedness, and being a team player are all skills that our next generation need to possess. But let’s work backwards: our high school teachers signed up for this. We can get our kids college and career ready; and if we don’t, shame on us. Our goal as high school teachers is send productive citizens into the world. Some years are better than others. Some kids have the advantage of supportive homes, while many do not. But we know where they need to be, and if our colleges and universities are unhappy with the product they are receiving then the communication between the the high schools and post-secondary schools needs to improve. We don’t need to throw it on the elementary teachers and students. No, those teachers need to instill a love of school so when children get to our middle and high schools they are not burnt out. They are encouraged, excited, confident, and motivated.

But we know where they need to be, and if our colleges and universities are unhappy with the product they are receiving then the communication between the the high schools and post-secondary schools needs to improve. We don’t need to throw it on the elementary teachers and students. No, those teachers need to instill a love of school so when children get to our middle and high schools they are not burnt out. They are encouraged, excited, confident, and motivated.

Creating modules that are a scripted nightmare for both the teacher and student is not the answer. You are ruining children. You are killing their spirit. You are making them believe they are dumb because they can’t multiply and divide on the exact day that the module says they should be multiplying and dividing. You are creating a generation of disengaged children who now feel insufficient.

This mom is angry. This educator is pessimistic. This state is in trouble.

Sincerely,

Mrs. Momblog

Advocating for your child too? Join Mrs. Momblog on Facebook for more. Please click the link below:

Momblog on Facebook for more. Please click the link below:

https://www.facebook.com/MrsMomblog?ref=hl

Please like and share from within this blog. Thank you!

Like this:

Like Loading...

This entry was posted in Uncategorized and tagged Commissioner King, common core, education, homework, modules, NYS. Bookmark the permalink.

What Happened to the Common Core?

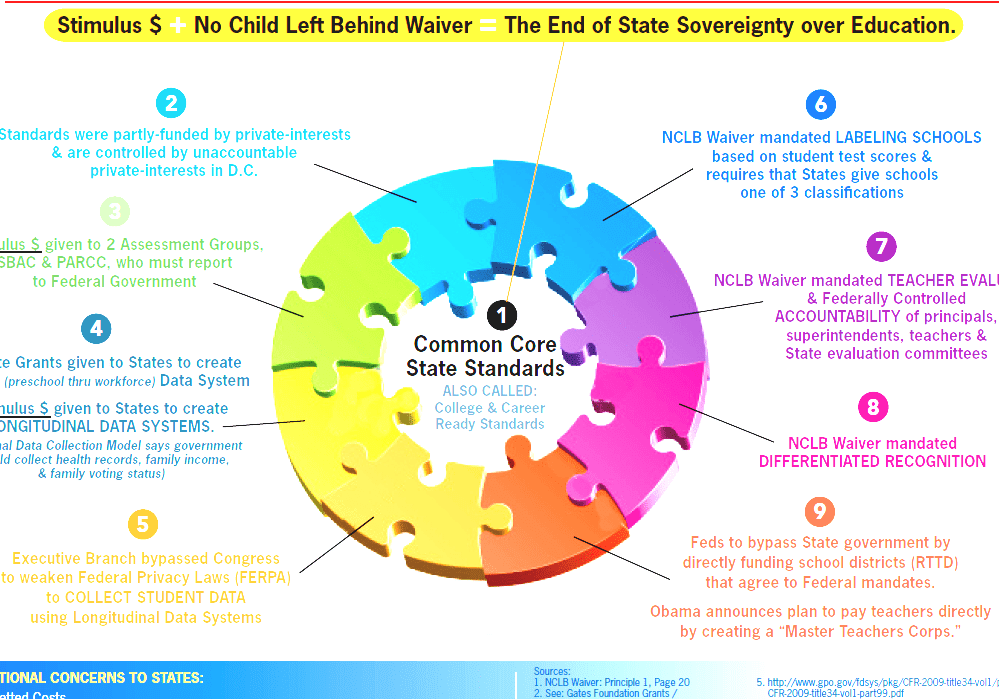

The Common Core. Just last year, according to a Gallup poll, most Americans had never heard of the Common Core State Standards Initiative, or "Common Core," new guidelines for what kids in grades K–12 should be able to accomplish in reading, writing, and math.

Designed to raise student proficiencies so the United States can better compete in a global market, the standards were drafted in 2009 by a group of academics and assessment specialists at the request of the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers. With widespread bipartisan support from such ideological opponents as U. S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, as well as the business community, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, in 2010 the standards sailed remarkably fast through adoption in 40 states and the District of Columbia. Five more states embraced them over the next two years.

S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, as well as the business community, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, in 2010 the standards sailed remarkably fast through adoption in 40 states and the District of Columbia. Five more states embraced them over the next two years.

The public paid little attention — until the 2014–15 deadline for standardized testing of the new standards loomed. And suddenly, America woke up.

Today, the Common Core is not only on the public radar, but the focus of a growing nationwide resistance from an unusual coalition of right-wingers, liberals, teachers, and parents, for a variety of very different reasons. The Tea Party, dubbing the standards as "Obamacore," paints them as an intolerable intrusion of the federal government into local control of schools. Parents sick of the testing culture are drawing a line with the new Core assessments, and some states are balking at the increased time and costs of these tests. Teachers' unions are split: Some local groups, including the Chicago Teachers Union and the New York State United Teachers, oppose the new standards entirely, while the two national unions — the National Educators Association (NEA) and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) — support the Core but want delays in implementation.

Teachers' unions are split: Some local groups, including the Chicago Teachers Union and the New York State United Teachers, oppose the new standards entirely, while the two national unions — the National Educators Association (NEA) and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) — support the Core but want delays in implementation.

Some parents find the new standards impossibly frustrating, especially the math component, famously skewered by comedian Louis C.K., whose mother was a math teacher, for making his daughters hate school. Critics complain that this massive change to American education — one of the most significant shifts ever — was rushed through without any real democratic process or empirical data supporting the value. Some worry that corporate interests are the real force behind the Core, since they'll reap huge profits from selling new tests and preparation materials, and many are deeply suspicious of the hundreds of millions of dollars the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation poured into supporting the effort.

As all these concerns converged, the tide began to turn.

In March, Indiana, one of the first states to adopt the Common Core, became the first to back out. In June, South Carolina and Oklahoma followed, and other states are considering at least slowing implementation. In Louisiana, Governor Bobby Jindal, formerly a strong Core proponent, has done a complete flip and is now battling his state's education superintendent in efforts to scuttle the new standards. Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker recently asked the state legislature to drop the standards.

Proponents — once elated at how fast the standards were adopted — suddenly find themselves scrambling to stem a mutiny. They are asking skeptics to simply give the standards a chance, insisting that their emphasis on reasoning and critical thinking will better prepare students for college and the workforce. Importantly, they worry that suddenly dropping or stalling the Common Core after four years of preparation, without offering a reasonable substitute, will seriously derail teachers and kids.

But with so much controversy and division, the question today is: Will the Core survive?

High Expectations

As former Secretary of Education for Massachusetts, Professor Paul Reville was instrumental in the Commonwealth's adoption of the Common Core, and he remains a stalwart supporter.

"On the whole, I think the Common Core is a good thing for the country," says Reville, former executive director of the Pew Forum on Standards-Based Reform. "The idea that we should have uniform high expectations for students all across the country is an important idea that states recognized and pioneered within their own boundaries long ago."

The central concept, he says, is that the nation's 40 million K–12 students should be offered the same high-standard education no matter where they go to school; a child in Mississippi, say, should finish each grade with the same general proficiencies as one in Maine — and ready to compete in an increasingly competitive global marketplace. This notion was extremely attractive to most of the nation's governors, who worried that curricula developed independently in the nation's 14,000 school districts varied so dramatically that some children were significantly disadvantaged simply by geographical accident.

This notion was extremely attractive to most of the nation's governors, who worried that curricula developed independently in the nation's 14,000 school districts varied so dramatically that some children were significantly disadvantaged simply by geographical accident.

"What [the Core] is saying is that if children's education is important to our future, then irrespective of where they're born, we ought to have high expectations for all of them, the kind of expectations that prepare them for 21st century employment and citizenship," says Reville.

Amity Conkright, Ed.M.'11, has worked more closely with the new standards than most: She is an ELA Common Core curriculum writer for the Lake Elsinore Unified School District in California. She, too, is an unabashed proponent.

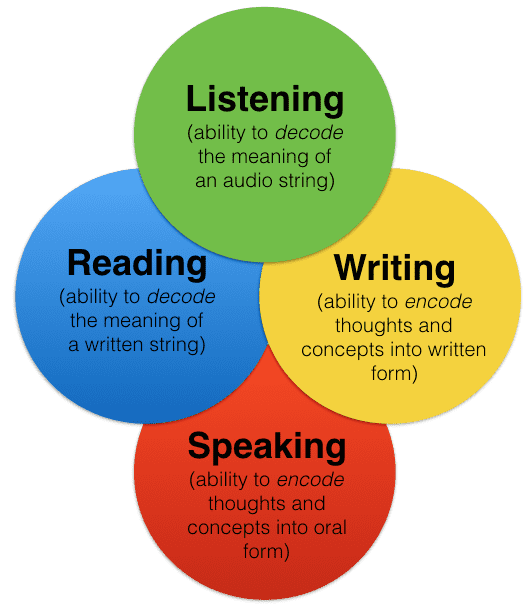

"Common Core requires a greater rigor than we've seen in the past, with more text complexity, and the reading levels have increased," she says. "It also highlights skills you are going to need in real life — technical skills, writing skills. I think they've upped the game."

I think they've upped the game."

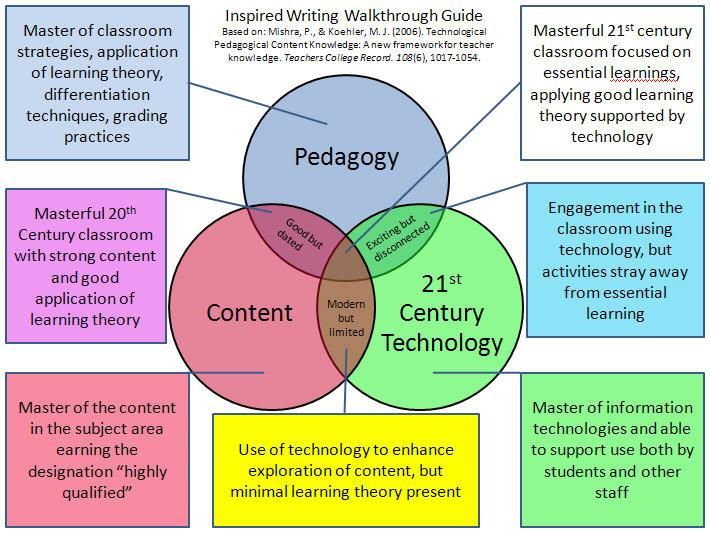

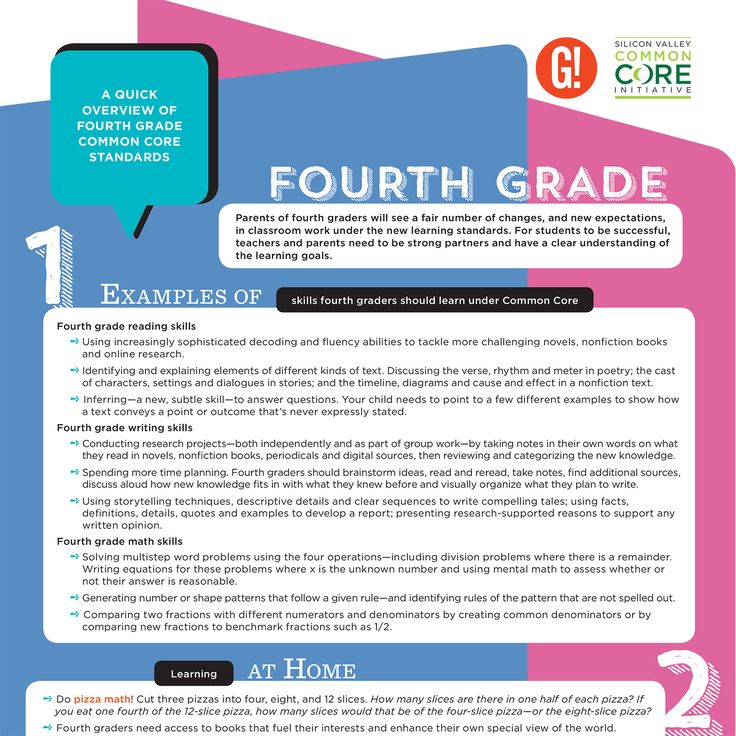

Educators, business leaders, and politicians had applauded — at least in theory — the Core's focus on reasoning, analysis, and problemsolving. In contrast to rote memorization, this approach is designed to prepare students for the critical thinking skills that modern employers seek. But once implementation began, teachers and parents were surprised by some changes the Core required, including less emphasis on literature: half of grade-school reading assignments must be nonfiction, and by 12th grade, that rises to 70 percent.

Still, it's the math component that has drawn the most criticism. In order to help students develop problemsolving skills useful in many areas of life, the Core's focus on "conceptual" math requires students to understand the reasoning behind the correct answers to math problems. It's a major shift, and many parents are finding it near impossible to help their children do their homework. And it's a major modification for teachers, too.

"We are asking teachers to significantly change their practices," says Professor Jal Mehta. "If you are a math teacher and you've been teaching a specific set of algorithms to teach geometry, now Common Core wants you to teach it in a much more conceptual way. That's a really big shift."

Even so, "My impression is that very few educators oppose the Common Core per se," says Professor (emeritus) Robert Schwartz, C.A.S.'68, a former president of Achieve, Inc., an independent, nonprofit created by governors and corporate leaders to help states improve schools. "While people might legitimately take issue with one or another aspect of the standards, it is hard to argue that these standards don't represent a significant improvement over most current state standards, and even harder to argue that we won't be better off in having one set of standards…rather than 50 sets."

Pockets of Resistance

What proponents didn't fully predict — perhaps because the standards sailed through with such widespread support — was the rise of so many different pockets of resistance uniting into a nationwide movement to kill the Core.

The discussion has become far messier because debate over the Core has become enmeshed — even conflated — with growing opposition to high-stakes testing. It's been 13 years since a culture of consequential student testing was launched in the George W. Bush administration as part of the No Child Left Behind initiative. The Common Core requires new assessments to measure student performance, with two primary options, each backed by a consortium of states: PARCC (Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers) and the Smarter Balanced Assessment. Once the new tests connected to the Core kicked in, the opposition attracted many new adherents and the battle got a lot fiercer.

Already, some states that committed to these tests have backed out, in some cases because the cost of these tests is significantly higher than before; some are creating their own assessments. From New York to Florida, organized "opt-out" groups are springing up to fight the testing culture with rallies and other protests, and an estimated 35,000 kids in New York refused to take the Common Core assessments this year.

Professor Daniel Koretz points out that there was a movement in New York City by parents to opt out of standardized testing even before the Common Core. But, he adds, "The Common Core gives it more impetus because it's a harder test, which makes people more upset." Proficiency scores plummeted in New York state two years running, for example, after students started taking Core-aligned tests.

The Core presents a chance that various groups, including people with legitimate concerns about high-stakes testing, don't want to miss, some believe. Transition to the Core is an opportunity to "push for a pause on current high-stakes testing policies and a Delay in implementing new ones," which is how the Core/testing issues have become conflated, says Associate Professor Martin West, who recently served as a senior adviser to U.S. Senator Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.).

But for Core proponents, the timing couldn't be worse: Just as states began implementing the new standards, 40 states receiving No Child waivers are also launching new systems to evaluate teachers, which will incorporate some measures of student achievement, including, where available, scores from standardized tests.

"That's providing the opportunity for opponents of that change in high-stakes testing to use the Common Core and its implementation as a justification for delay," West says, which is why "there are more and more examples of state and local [teachers' unions] coming out in strong opposition to the Common Core."

The Right Wing and "Obamacore"

And then there's the political issue.

"What is capturing most media attention is the opposition coming from the Tea Party and others on the right," says Schwartz. Now that Obamacare has become more successful than critics predicted, "Obamacore" is their next target, he says, "fueled by right-wing talk show hosts feeding listeners a steady stream of misinformation." It's putting enormous pressure on governors and legislatures in Red states to retreat from their support of the Core, including Jindal, and "there will probably be others before this is over," he adds.

The super-right wing criticism isn't terribly valid, in Reville's opinion, because "it comes from a political place: 'Since the Obama administration promoted it, we will be opposed automatically. '" For that reason, he says, "Those objections ought to be taken with a large grain of salt."

'" For that reason, he says, "Those objections ought to be taken with a large grain of salt."

But teasing out the various interests — and what they really represent — isn't easy. That's why the Common Core debate "makes the most sense to people who've studied the Cold War because it's really a proxy fight," says Rick Hess, Ed.M.'90, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute.

"On the right, the Common Core is really a proxy fight over Obamacare and concerns about slippery slopes and federal involvement in state and local self-determination," says Hess. On the left, it serves as a proxy fight over standardized testing being tied to teacher evaluations. Teachers' unions "have consistently supported Common Core as a set of instructional standards," he notes, but dislike the testing component, which is "super-sized" under the Core.

Anna Klafter, Ed.M.'13, chief academic officer of TechBoston Academy in Boston, finds the new standards themselves "fine and good; they are things all kids should know, and the standards are broad and wide enough that a good teacher can get creative [and] they don't restrain a good teacher. " But the new assessments are still missing the point.

" But the new assessments are still missing the point.

"They are moving from rote memorization in the move from the MCAS to the PARCC, the Common Core assessment," she says, referring to the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System state test. "It's attempting to touch on some more critical thinking and prepare students for more real-life knowledge versus algebraic equations or whatnot." But at the same time, she worries, the new tests are "still far from a true measure of what our kids can do … because they are a high-stress, high-stakes, pen-and-paper situation."

Joshua Starr, Ed.M.'98, Ed.D.'01, the superintendent of schools in Montgomery County, Md., agrees. "I do think the PARCC questions, from what I've seen of the samples, are solid. It might be a good test," he says. "But it's the policies associated with the testing that I'm against." Evaluating teachers based on the student test results is bad for everyone: "It's like if the measure of your health and wellness were what you weighed every day — and so, if you were held accountable only for what you weighed, you'd be tempted to take diet pills," he says. "We've been on diet pills in American education for the last 14 years, and it's not healthy and sustainable. It's not good for teachers and kids, and I'm encouraging people to get off diet pills."

"We've been on diet pills in American education for the last 14 years, and it's not healthy and sustainable. It's not good for teachers and kids, and I'm encouraging people to get off diet pills."

Schwartz says opposition within the education community mainly centers on implementation of the new standards, and the pressure on teachers. "Will teachers be given the time and support to change their practice in ways that align with the more intellectually ambitious modes of instruction envisioned by Common Core?" he asks. In a profession that already feels under siege, the decision in most states — encouraged by the U.S. Department of Education — to press ahead with using student test scores as a significant component of a teacher's evaluation "just fuels the perception that we care more about weeding out weak teachers than giving the vast majority of teachers the time and support they need to make a successful transition to Common Core," says Schwartz. That message may be getting through to Core proponents:

For parents tired of the testing culture, the growing attention to the Core has prompted great pushback to the testing culture. They're asking why so much school time is spent on tests that aren't much used to assist individual children but rather to compare schools and districts in an to attempt to close the achievement gap, says Hess. "Again, it's a proxy fight," he notes. "A lot of this angst is less about the Common Core in particular, but [Common Core] is short hand for testing, and I think certainly there's an appetite for less testing."

They're asking why so much school time is spent on tests that aren't much used to assist individual children but rather to compare schools and districts in an to attempt to close the achievement gap, says Hess. "Again, it's a proxy fight," he notes. "A lot of this angst is less about the Common Core in particular, but [Common Core] is short hand for testing, and I think certainly there's an appetite for less testing."

Common Concerns

One misperception about the Core is that it mandates a national curriculum. In fact, the Core sets goals and standards but leaves curricula and materials in the control of local states and school districts. Proponents also take issue with the perception that the Core was federally mandated, since states chose to adopt them, albeit incentivized with federal money.

But these arguments don't convince conservative politicians like Jindal, a probable 2016 presidential candidate, or even some at the Ed School.

"The proponents of Common Core are trying to bill this as a state-led, state-initiated effort, and, at best, it might have been state-initiated initially, although I find that is only part of the story," says current doctoral student Chris Buttimer, Ed. M.'09. "This is clearly coming down from the Arne Duncan administration as well. I think [Common Core] is essentially a federal initiative at this point, having been created by a small group of people, including very few if any teachers, working in conjunction with the Duncan administration, and it has been at the very least aggressively encouraged for states to adopt, particularly through the Race to the Top funding."

M.'09. "This is clearly coming down from the Arne Duncan administration as well. I think [Common Core] is essentially a federal initiative at this point, having been created by a small group of people, including very few if any teachers, working in conjunction with the Duncan administration, and it has been at the very least aggressively encouraged for states to adopt, particularly through the Race to the Top funding."

Professor (emeritus) Eleanor Duckworth is also concerned that few teachers helped in the development of the standards, "so I don't have a lot of faith in the standards they would come up with," she says. Moreover, she adds, "I don't support the idea of top-down standards being delivered for the entire country."

Buttimer is among a not-insubstantial group, many very prominent on the Web, who are deeply suspicious of corporations and other big-money interests behind the switch to the Core. They are convinced that Gates and the Koch brothers have financial motives lurking behind their stated interests in helping U. S. students become more globally competitive. And in their eyes, the testing and textbook companies are clearly self-interested.

S. students become more globally competitive. And in their eyes, the testing and textbook companies are clearly self-interested.

"Standards in the United States have not been and will not be decoupled from testing, nor from the profit motive that's at least partly driving the creation of standards-based reform and test-based accountability," says Buttimer.

While Hess doesn't disagree that testing corporations will benefit, he finds the argument that the profit-motive is the primary force behind the adoption of the Core "silly," noting, "The corporations are making money off the old tests and will make it off the new tests."

And for those who see the Core as a major step forward in American education, all of this criticism is extremely frustrating.

"The whole controversy about the Common Core and the assessments risks becoming an enormous distraction from the much more difficult work, the central education reform work of devising effective strategies for educating children to higher levels," says Reville. "There are lots of education pundits out there who embrace the diversion of an endless standards debate because they are clueless about how to actually improve student learning."

"There are lots of education pundits out there who embrace the diversion of an endless standards debate because they are clueless about how to actually improve student learning."

How Strong Is the Opposition?

Still, Reville and others concede, opposition is real and growing.

"What's hard to judge is how strong those forces are in comparison to economic leaders, governors, the Council of Chief State School Officers, and superintendents, many of whom have been supportive of the Common Core," Mehta says. "How it plays out will depend a lot on the politics of particular states and whether there will be a pendulum swing. I think it's too soon to know for sure."

West, for one, believes the strength of the resistance may be overblown. "I don't think we should overstate the extent to which the backlash has undermined the Common Core momentum," he says. While several states have formally withdrawn, the vast majority have not. "I certainly think [the standards] can still be saved," he says. "In fact, you might say they don't need saving."

"In fact, you might say they don't need saving."

What many want to avoid now is the scuttling of a new approach that may work very well — especially when the shift to the Core is so far along.

"Do I think it's perfect? No. Do I want to lose Common Core? No. I don't want to lose the tremendous effort our teachers in Vermont have put into it," says Vermont's Secretary of Education, Rebecca Holcombe, Ed.M.'90, Ed.M.'04, who is also a current doctoral student. "My fear is, to lose the Common Core, we'll lose five years. We don't want to lose the work and destabilize our system by going back and trying something else, given the current absence of anything more substantive."

And there are steps that would go a long way toward restoring confidence in the new system, some believe.

"I think the solution would start with an understanding of the scale of the undertaking, and trying to explain that to the public," says Mehta, "that we're trying to educate children in a way we haven't done before in America, a way that will ultimately make them more prepared for college and a career but that it will take a long time, and it will be slow. "

"

The valid concerns of parents about too much testing also should be taken seriously. If families feel their own kids are spending too much time taking tests that aren't helping them, "that will create real and growing headwinds," says Hess. On the other hand, if parents see concrete examples of teachers using Common Core assessments to assist the development of their own children — "If you see them saying, 'Here are things we can do for your kid,' — then you'll start to see a lot more parental comfort," he says.

Valid criticism should be respected and used to spur continued improvements to the Core, Reville agrees. "I think the opposition is gathering strength, and so proponents of Common Core and the new assessments will have to listen to that and respond," he says. "I don't think you're going to see whole-scale abandonment of the Common Core or the assessments. I do think you will see some reconsideration about both the quantity and quality of testing. These concerns will likely be reflected in the work surrounding the new assessments. "

"

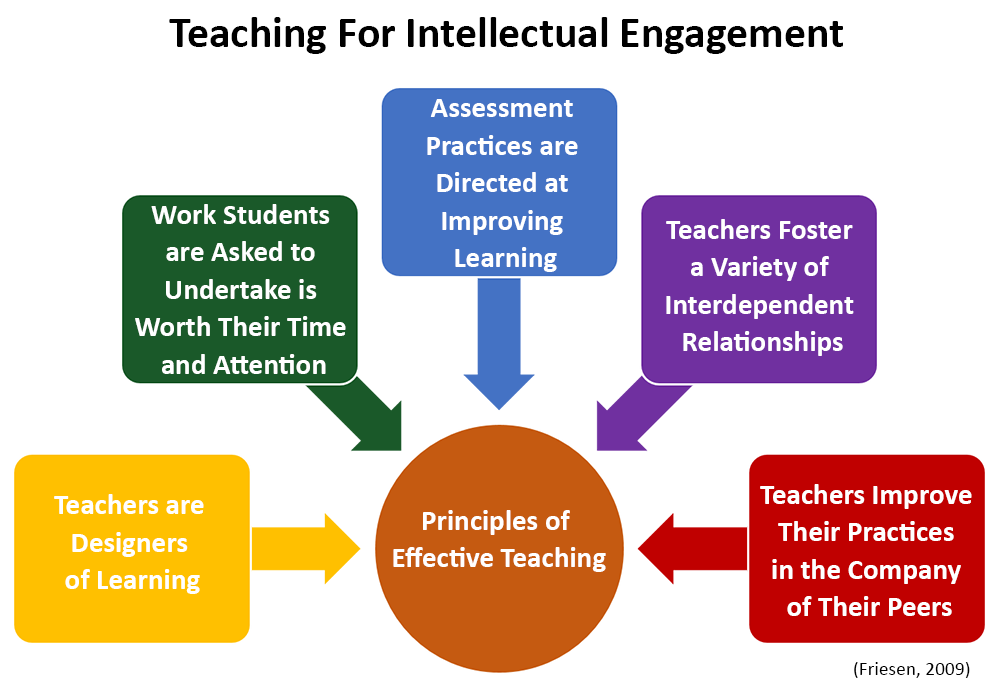

But if the Core is to succeed, there's another challenge, says Mehta. "It will only work if there is really significant time, money, and political will put into supporting teachers' ability to help students meet the standards," he says. "In the absence of that, we'll have No Child Left Behind redux. Common Core standards are significantly more demanding, so if we raise standards and don't increase support and capacity building, the schools won't meet the standards, which over time will lead to either lowering of standards or increased resistance on the part of teachers and schools."

Buttimer shares this view. "As a former teacher, I don't necessarily have an issue with the contents of the standards themselves, at least for middle and high school," he says. However, "We're setting high standards without helping teachers and students get to those standards" through professional development and other capacity-building support. By tying teacher performance to results without supporting them to make the change, "We've skipped right to the evaluate-and-punish stage. "

"

Indeed, Schwartz notes that California, which has made a "massive investment in professional development but also suspended state testing," is a state that "seems most on track for successful implementation of the Core."

It is a sad irony, he believes, that opposition to testing is rising "just at the point when we are finally going to have a set of tests coming from the two testing consortia that promise to be substantially better than the state tests currently in use. Will we be smart enough to slow down implementation, make the necessary investments in teacher learning, and move toward a system with fewer but better tests?"

That's why, Mehta says, it's critical to "try to create substantive support for teachers to learn how to teach the standards, to help teams of teachers work together and share what works. And then celebrate small moments of progress, and go back to the public and say, 'We're making progress,' and use that to build support for the policy. We have to get away from our impatience mentality. "

"

— Elaine McArdle is a freelance writer who writes frequently for Ed. Her last piece looked at what happens to learning during conflict.

[PLEASE NOTE: An earlier version of this article mistakenly referred to the American Federation of Teachers as the Teachers Federation of America.]

How I Reprogrammed My Brain to Understand Math / Sudo Null IT News

Sorry Educational Reformers - We Still Need Cramming and Repetition

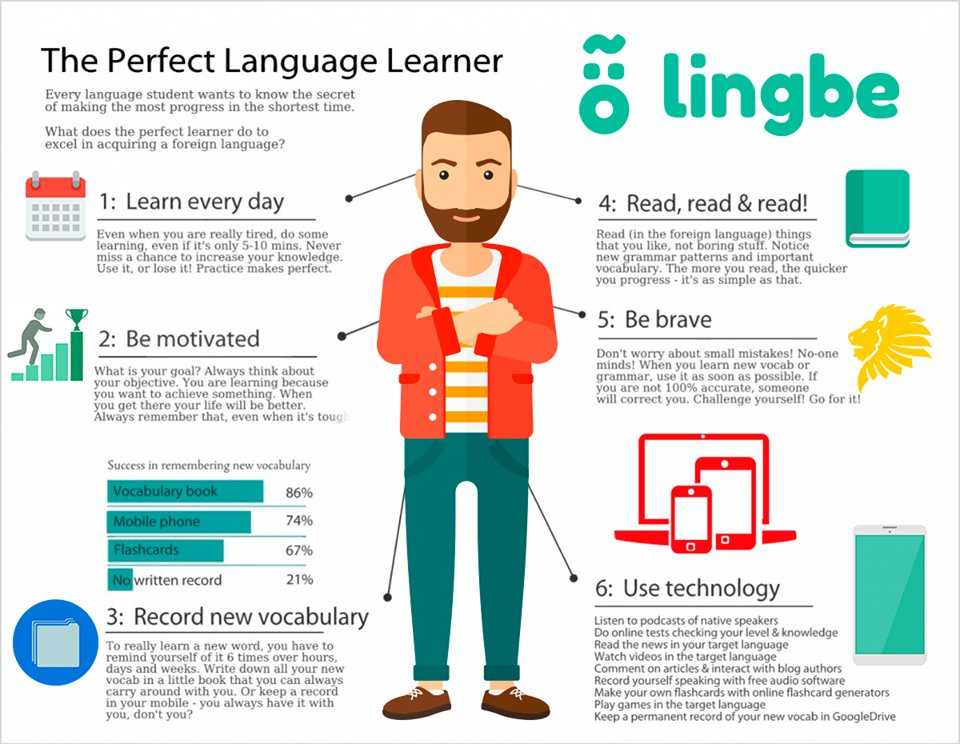

I was a cranky child who grew up on the lyrical side of life, and my attitude to mathematics and science was as if they were symptoms of the plague. And therefore it is strange that I turned into a person who daily deals with triple integrals, Fourier transforms and, the pearl of mathematics - the Euler equation. It's hard to believe that I've gone from a matophobe to a professor of applied sciences.

One day one of my students asked me how I did it - how I changed my brain. I wanted to answer - damn it, with difficulty! I still flunked exams in mathematics and physics in elementary, middle and high schools. I enrolled in a math underachievement class after I served in the military at age 26. At an exhibition of examples of neuroplasticity in adults, I would be the first specimen.

I enrolled in a math underachievement class after I served in the military at age 26. At an exhibition of examples of neuroplasticity in adults, I would be the first specimen.

Studying mathematics and science as an adult opened the door for me to engineering. But these severe adult changes in the brain gave me an inside look at the neuroplasticity associated with adult learning. Fortunately, my Systems Engineering PhD, during which I studied STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math), and my subsequent research on human thinking, helped me understand recent breakthroughs in neuroscience and cognitive psychology related to learning.

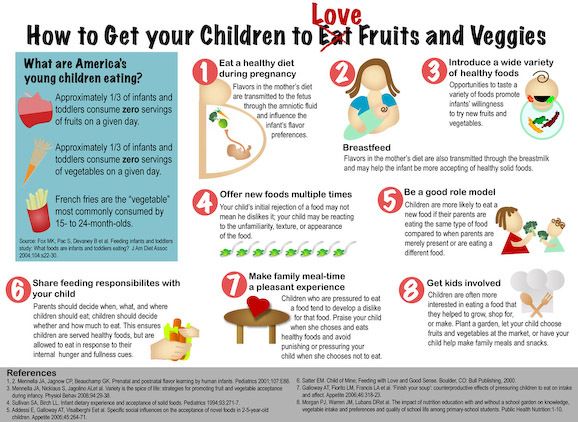

In the years since my doctorate, thousands of students have passed through my class—raised in primary and secondary school with the belief that understanding mathematics through active discussion is the talisman of learning. If you can explain what you've learned to others—say, by drawing a picture—then you probably really get it.

Japan became an example of this "understanding-focused" technique and an object of imitation. But the end of the story often disappears from the discussion: in Japan, the Kumon teaching method was also invented, which is based on memorization, repetition and cramming to achieve excellent mastery of the material by the student. This intensive post-secondary program is preferred by thousands of parents in Japan and around the world, complementing the co-education of children with plenty of practice, repetition, and a cleverly designed cramming system to ensure that they master the material.

But the end of the story often disappears from the discussion: in Japan, the Kumon teaching method was also invented, which is based on memorization, repetition and cramming to achieve excellent mastery of the material by the student. This intensive post-secondary program is preferred by thousands of parents in Japan and around the world, complementing the co-education of children with plenty of practice, repetition, and a cleverly designed cramming system to ensure that they master the material.

In the US, a focus on understanding sometimes replaces, rather than complements, older teaching methods that scientists confirm work with the natural processes of the brain when learning complex things like math and science.

The latest wave of math education reform includes the Common Core, an attempt to impose rigid common standards across the US, although critics say these standards fall short of what other, more advanced countries achieve. Outwardly, the standards have some perspective. In mathematics, students are supposed to have equal opportunities in conceptual understanding, practical and procedural skills.

In mathematics, students are supposed to have equal opportunities in conceptual understanding, practical and procedural skills.

The devil, as usual, is in the details of implementation. In today's educational climate, memorization and repetition of STEM disciplines, as opposed to learning language and music, are often viewed as unworthy activities that waste the time of students and teachers. Many teachers have long believed that understanding concepts in STEM disciplines has the highest priority. Of course, it's easier for teachers to engage students in discussions about math topics (and this process, if properly guided, can greatly help in understanding problems) than to tinker with grading homework. As a result, although procedural skills and fluency should be taught in the same doses as conceptual understanding, this is often not the case.

The problem with focusing only on understanding is that math and science students can often pick up the basic concepts of an important idea, but the understanding quickly slips away without being reinforced through practice and repetition. Even worse, students often think they understand something when they don't. Such an approach can often bring only the illusion of understanding. As one of the underperforming students recently told me, “I don’t understand why I did so badly on the assignment. I understood everything in the class.” It seemed to him that he understood everything, and it is possible that he did, but he did not use what he understood in practice so that it would be fixed in the brain. He has not developed procedural proficiency or the ability to apply knowledge.

Even worse, students often think they understand something when they don't. Such an approach can often bring only the illusion of understanding. As one of the underperforming students recently told me, “I don’t understand why I did so badly on the assignment. I understood everything in the class.” It seemed to him that he understood everything, and it is possible that he did, but he did not use what he understood in practice so that it would be fixed in the brain. He has not developed procedural proficiency or the ability to apply knowledge.

There is an interesting relationship between teaching sports discipline and teaching mathematics and exact sciences. When you learn how to hit with a golf club, you perfect your stroke with years of practice. Your body knows what to do just when you think about it - you don't have to remember all the components of a complex swing to hit the ball.

In the same way, when you understand why you do something in mathematics, you don't have to explain the same thing to yourself every time. You don't have to carry 25 marbles with you, lay them out 5 rows by 5 columns on the table to make sure 5 x 5 = 25. At some point you just know it. You remember that when multiplying the same numbers to different powers, you can simply add the powers (10 4 x 10 5 = 10 9 ). By using this procedure often and on different occasions, you will find that you understand why and how it works. A better understanding of a topic comes from creating a meaningful pattern in the brain.

You don't have to carry 25 marbles with you, lay them out 5 rows by 5 columns on the table to make sure 5 x 5 = 25. At some point you just know it. You remember that when multiplying the same numbers to different powers, you can simply add the powers (10 4 x 10 5 = 10 9 ). By using this procedure often and on different occasions, you will find that you understand why and how it works. A better understanding of a topic comes from creating a meaningful pattern in the brain.

I learned all this about mathematics and about the process of learning itself, not in the classroom, but in the course of my life, as a person who read Madeleine Lengle and Dostoyevsky as a child, studied languages in one of the world's leading language institutes, and then abruptly who changed his path and became a professor of technical sciences.

As a young girl with a passion for learning languages and lacking the money and skills, I couldn't afford to pay for college. That's why I joined the army after high school. I enjoyed learning languages at school, and it seemed like the army was the place where a person could get money for learning languages by attending the highly regarded language institute of the Ministry of Defense - a place where learning languages was turned into a science. I chose Russian because it was very different from English, but it was not so difficult to study it all my life and eventually reach the level of a 4-year-old child. Besides, I was drawn to the Iron Curtain - couldn't I have used my knowledge of Russian to look beyond it?

That's why I joined the army after high school. I enjoyed learning languages at school, and it seemed like the army was the place where a person could get money for learning languages by attending the highly regarded language institute of the Ministry of Defense - a place where learning languages was turned into a science. I chose Russian because it was very different from English, but it was not so difficult to study it all my life and eventually reach the level of a 4-year-old child. Besides, I was drawn to the Iron Curtain - couldn't I have used my knowledge of Russian to look beyond it?

After the army, I became an interpreter on Soviet trawlers in the Bering Sea. Working for the Russians was interesting and exciting – but it was also the outwardly embellished work of a migrant. During the fishing season, you go out to sea, make good money, get drunk occasionally, and then return to the port at the end of the season and hope to be hired again next year. For a Russian-speaking person, there was practically only one alternative to this - work for the NSA. My army contacts encouraged me to do this, but I didn't have the heart for it.

My army contacts encouraged me to do this, but I didn't have the heart for it.

I began to realize that while knowing another language was good, it was a skill with limited capabilities and potential. Because of my ability to inflect words in Russian, my house was not besieged. Unless I was prepared to endure seasickness and occasional malnutrition on stinking trawlers in the middle of the Bering Sea. I couldn't help but think of the West Point engineers I worked with in the military. Their mathematical approach to problem solving was clearly useful in the real world—more useful than my failures in mathematics.

So, at the age of 26, when I was leaving the army and assessing the possibilities, I suddenly thought: if I want to do something new, why not try something that would open up a whole new world of opportunities for me? Technical sciences, for example? And this meant that I had to learn a new language - the language of numeration.

With my poor understanding of the simplest mathematics, after the army I took up algebra and trigonometry in the course for the underachievers. Trying to reprogram the brain sometimes seemed like a stupid idea - especially when I looked at the faces of my younger classmates. But in my case, and I learned Russian in adulthood, I hoped that some aspects of language learning could be applied to the study of mathematics and the exact sciences.

Trying to reprogram the brain sometimes seemed like a stupid idea - especially when I looked at the faces of my younger classmates. But in my case, and I learned Russian in adulthood, I hoped that some aspects of language learning could be applied to the study of mathematics and the exact sciences.

While studying Russian, I tried not only to understand something, but also to achieve fluency in it. Fluency in a subject as vast as language requires a degree of familiarity that can only be developed by repeated and varied work in different areas. My classmates who studied the language concentrated on simple understanding, and I tried to achieve internal fluency with the words and structure of the language. It was not enough for me that the word "understand" means "to understand". I practiced with the verb, constantly using it at different tenses, in sentences, and then I understood not only where it can be used, but also where it should not be used. I practiced quickly recalling these aspects and options. Through practice, one can understand and translate dozens and hundreds of words from another language. But if you don't have fluency, then when someone quickly spits out a bunch of words at you, like in a normal conversation, you have no idea what this person is saying, although technically you seem to understand all the words and structure. And you certainly can't speak fast enough for native speakers to enjoy listening to you.

Through practice, one can understand and translate dozens and hundreds of words from another language. But if you don't have fluency, then when someone quickly spits out a bunch of words at you, like in a normal conversation, you have no idea what this person is saying, although technically you seem to understand all the words and structure. And you certainly can't speak fast enough for native speakers to enjoy listening to you.

This approach, focusing on fluency rather than mere understanding, has propelled me to the top of the class. I didn't understand it at the time, but this approach gave me an intuitive understanding of the basics of learning and developing expert skills - chunking [chunking].

Chunking was first proposed in Herbert Simon's revolutionary work in the analysis of chess. Various mental analogues of chess templates served as pieces. Neuroscientists have gradually come to understand that experts, say in chess, are experts in that they can store thousands of pieces of knowledge in long-term memory. Chess masters can remember tens of thousands of different chess patterns. In any field, an expert can recall one or more pieces of neural subroutines that are well connected together in order to analyze and respond to a new situation. This level of real understanding and the ability to use this understanding in new situations is acquired only from familiarity with the subject, obtained through repetition, memorization and practice.

Chess masters can remember tens of thousands of different chess patterns. In any field, an expert can recall one or more pieces of neural subroutines that are well connected together in order to analyze and respond to a new situation. This level of real understanding and the ability to use this understanding in new situations is acquired only from familiarity with the subject, obtained through repetition, memorization and practice.

A study of chess masters, paramedics, and fighter pilots has shown that in stressful situations, conscious analysis of the situation gives way to rapid subconscious data processing, with experts accessing a deeply integrated set of mental patterns—pieces. At some point, a conscious understanding of why you do what you do only starts to slow you down and interrupts the flow, leading to worse decisions. I was right to intuitively feel the connection between learning a new language and mathematics. The daily and continuous study of the Russian language excited and strengthened the neural circuits in my brain, and I gradually began to tie together Slavonic pieces that could easily be recalled from memory. By alternating learning, practicing so that I knew not only when to use a word but also when not to use it, or to use a different variant of it, I used the same approaches that are used to learn mathematics.

By alternating learning, practicing so that I knew not only when to use a word but also when not to use it, or to use a different variant of it, I used the same approaches that are used to learn mathematics.

I started studying mathematics and science as an adult with the same strategy. I was looking at the equation - for a simple example, let's take Newton's second law, F = ma. I practiced feeling the meaning of each letter: "f", meaning force, is a push, "m", mass, is a heavy resistance to pushing, "a" was a joyful sensation of acceleration. (In the case of the Russian language, I also practiced the pronunciation of the Cyrillic letters). I memorized the equation, carried it in my head and played with it. If m and a are large, what will happen to f in the equation? If f is large and a is small, what is m? How do units of measure converge on both sides? Play with the equation - how to connect the verb with other words. I began to perceive that the vague outline of the equation was like a metaphorical poem, in which there were all sorts of beautiful symbolic representations. And although then I would not have expressed it this way, but for a good study of mathematics and the exact sciences, I needed to slowly and daily build strong nervous chunky subroutines.

And although then I would not have expressed it this way, but for a good study of mathematics and the exact sciences, I needed to slowly and daily build strong nervous chunky subroutines.

Over time, professors of mathematics and science told me that building well-recorded bits of experience through practice and repetition was vital to success. Understanding does not lead to fluency. Fluency leads to understanding. In general, I believe that real understanding of a complex topic comes solely from fluency.

Entering a new field for me, becoming an electrical engineer, and eventually a professor of engineering, I left the Russian language behind. But 25 years after I last raised a glass on Soviet trawlers, my family and I decided to take a trip along the Trans-Siberian through all of Russia. And although I was looking forward to the long-desired trip with pleasure, I was also worried. All this time I practically did not speak Russian. What if I forgot everything? What have all those years of achieving fluency given me?

Of course, when I boarded the train for the first time, I found myself speaking Russian at the level of a two-year-old child. I searched for words, my declensions and conjugations were confused, and my previously almost perfect accent sounded terrible. But the foundation did not go away, and gradually my Russian improved. Even rudimentary knowledge was enough for daily needs. Soon the tour guides began to approach me for help in translating for other passengers. Arriving in Moscow, we got into a taxi. The driver, as I later realized, tried to deceive us by going the other way and getting stuck in a traffic jam, believing that foreigners who did not understand would calmly endure an extra hour of the counter. Suddenly, Russian words that I hadn't used for decades flew out of my mouth. Consciously, I didn't even remember that I knew them.

I searched for words, my declensions and conjugations were confused, and my previously almost perfect accent sounded terrible. But the foundation did not go away, and gradually my Russian improved. Even rudimentary knowledge was enough for daily needs. Soon the tour guides began to approach me for help in translating for other passengers. Arriving in Moscow, we got into a taxi. The driver, as I later realized, tried to deceive us by going the other way and getting stuck in a traffic jam, believing that foreigners who did not understand would calmly endure an extra hour of the counter. Suddenly, Russian words that I hadn't used for decades flew out of my mouth. Consciously, I didn't even remember that I knew them.

Fluency, when needed, was at hand - and helped us out. Fluency allows understanding to be built into consciousness, and to emerge as needed.

Looking at the lack of people specializing in the exact sciences and mathematics in our country, and our current teaching techniques, and remembering my own path, with my current knowledge of the brain, I understand that we can achieve more. As parents and teachers, we can use simple techniques to deepen understanding and turn it into a useful and flexible tool.

As parents and teachers, we can use simple techniques to deepen understanding and turn it into a useful and flexible tool.

I have discovered that having a basic and deeply learned fluency in maths and science - rather than just "understanding" - is extremely important. It opens the way to the most interesting activities in life. Looking back, I realize that I didn't have to blindly follow my original inclinations and passions. The same "runaway" part of me that loved literature and language ended up loving math and science - and ultimately transformed and enriched my life.

Pediatric orthopedic traumatologist

New parents always have many questions about the development of their child. We asked the most frequently asked questions to the traumatologist-orthopedist of the Evromed clinic, Dmitry Olegovich Sagdeev.

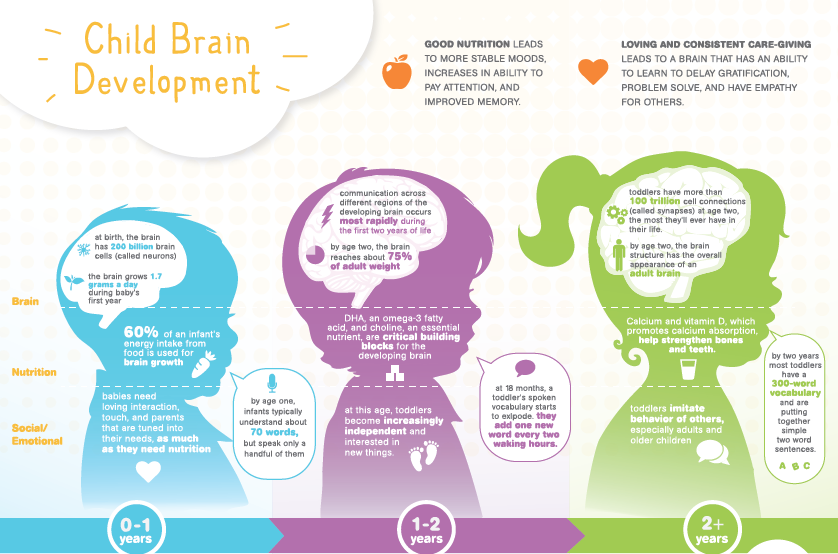

- A small child is recommended to be shown to an orthopedist quite often: a month, three months, six months, a year ... What is the reason for this, what exactly does the orthopedist evaluate?

- The orthopedist watches how the child's musculoskeletal system develops during periods of its active development in order to notice possible deviations in its development in time and correct them. At an early stage - a month - we do an ultrasound of the hip joints, so as not to miss any congenital pathology. At three to four months, ultrasound is repeated for control in order to see the dynamics of joint development.

At an early stage - a month - we do an ultrasound of the hip joints, so as not to miss any congenital pathology. At three to four months, ultrasound is repeated for control in order to see the dynamics of joint development.

According to the results of an ultrasound examination, the doctor may suspect violations of the formation and dynamics of the development of the hip joint.

The doctor of ultrasound diagnostics evaluates the formation of the joint according to a special scale (Graf's scale), and then the orthopedist determines whether correction is required with therapeutic exercises, whether any physiotherapy is needed, etc.

The earlier deviations in the development of the child are detected, the more effective the treatment will be.

At about six months, the child begins to sit down, then he will get up, walk, and it is important to know how his hip joint is formed and, if there are violations, to have time to correct them before that moment.

Hip dysplasia is a defect in the formation of the hip joint, which in severe forms leads to the formation of subluxation or dislocation of the femoral head.

- When hip dysplasia is detected, orthopedic structures are usually prescribed: Freik pillows, Vilensky splints, etc. They look pretty scary, and parents are afraid that the child will be uncomfortable in them.

- The child will not experience discomfort. He still does not have a stable understanding of what position his lower limbs should be in, so the design will not interfere with him.

At the same time, due to the impact of these structures, the child's legs are located at a certain angle, and in this position the femoral head is centered in the cavity, it is in the correct position, any deforming load is removed from it, which allows the joint to develop properly. If this is not done, then a constant deforming load will be placed on the head of the femur, which will ultimately lead to subluxation and dislocation of the hip. This will be a severe degree of hip dysplasia.

This will be a severe degree of hip dysplasia.

- In addition to dysplasia, ultrasound always looks at the formation of ossification nuclei in the hip joint. Why is their proper development so important to us?

The head of the femur is made up of cartilage. The ossification nucleus is located inside the femoral head and, gradually increasing, it seems to reinforce it from the inside and give the structure stability under axial load. In the absence of the ossification nucleus, any axial load on the thigh leads to its deformation, as a result of which subluxation and further dislocation of the hip may develop. Accordingly, if the core of ossification does not develop or develops with a delay, any axial loads are strictly prohibited: you can’t stand, and even more so, you can’t walk.

- Can I sit down?

- With a slow rate of ossification (ossification, bone formation), sitting is not prohibited, provided that the roof of the acetabulum is normally formed, the femoral head is centered. This is determined by ultrasound.

This is determined by ultrasound.

— What influences the formation of ossification nuclei, how can their development be stimulated?

- First of all - activity. Therefore, we recommend that you engage in therapeutic exercises with your child immediately from birth. Mom needs to do gymnastics with the child every day. Moreover, it is important that this should be a normal load, the so-called static load - when the child lies, and the mother spreads his arms and legs. I categorically do not recommend the “dynamic gymnastics” that is gaining popularity now - a set of exercises in which the child is twisted, twirled, swayed, rotated by the arms and legs, etc. to dislocation with rupture of the ligaments of the joint.

From 2.5 months, the child can and even needs to visit the pool. Individual lessons with a trainer in the water are very useful for the development of the musculoskeletal system, cardiovascular and respiratory systems, muscle training, and strengthening of the immune system.

As an auxiliary procedure, massage is useful.

Vitamin D is also needed, it stimulates the development of bone tissue. Vitamin D is recommended to be given to almost all children under two years of age, and to some even later. This issue is resolved jointly by a pediatrician and an orthopedist, doctors select the dosage of the drug and the duration of its administration. There is little sunlight in our region, which provokes vitamin D deficiency in almost all children, which leads to rickets. In Siberia, most children who do not take vitamin D have some degree of rickets.

If there are indications, the doctor may prescribe physiotherapy: magnetotherapy, electrophoresis, applications with polymineral mud wipes. These are effective, time-tested methods.

- Doctors say that the child should not be planted before he sits down on his own, put, stimulated for early standing, walking. What is it connected with?

- This is due to the fact that in a small child the musculoskeletal system is still immature, and both it and the central nervous system are not ready for active axial loads. If we begin to actively verticalize the child, stimulate him to sit, stand, this can lead to spinal deformity, disruption of the formation of joints. At the start, they should develop without axial loads, as laid down by nature. The systems, and, first of all, the central nervous system, must mature so that the signal from the brain from the so-called “central computer” to the periphery reaches the periphery undistorted and the response from the periphery to the center is also adequate. No need to rush. When these structures are ready, the child himself will sit down, and crawl, and stand up.

If we begin to actively verticalize the child, stimulate him to sit, stand, this can lead to spinal deformity, disruption of the formation of joints. At the start, they should develop without axial loads, as laid down by nature. The systems, and, first of all, the central nervous system, must mature so that the signal from the brain from the so-called “central computer” to the periphery reaches the periphery undistorted and the response from the periphery to the center is also adequate. No need to rush. When these structures are ready, the child himself will sit down, and crawl, and stand up.

- What are the age norms when a child sits down, gets up?

— There are indeed certain norms, but we should not focus too much on them. Each child develops according to his own individual program, there is no need to adjust everyone to one standard. To assess its development, it is necessary to take into account many different circumstances, ranging from the characteristics of the course of pregnancy and the birth of a child. I think doctors need more time and norms to adequately assess whether the child is developing correctly or not, and if there is a delay, see it in time and help the baby.

I think doctors need more time and norms to adequately assess whether the child is developing correctly or not, and if there is a delay, see it in time and help the baby.

Children begin to sit down at about six months, crawl - at 7-8 months. Classical development: the child first sat down, then crawled, then begins to get up, move around with support. Then, when he felt that he was ready, he broke away from the support and took the first independent steps. This happens when the musculoskeletal system has matured, the central nervous system and the vestibular apparatus have adapted. And all these systems have learned to work together correctly.

Some babies start crawling before they sit down, others will get up before they can crawl. It happens that a child does not crawl at all, but immediately got up and went. All these are features of individual development.

- Why are such devices as a walker bad, allowing the child to "go" much earlier, entertaining him?

- Walkers knock down the "program" of the correct interaction between the central nervous system, the vestibular apparatus and the musculoskeletal system. In walkers, the child occupies an unnatural position, he does not take a full step in them, but simply hangs, pushes off with his toes and moves in space. His brain and muscles remember this incorrect program of vertical position and movement, and later, when the child tries to start walking without a walker, these incorrect settings work for him, the wrong muscle groups that should keep him in an upright position turn on, and the child falls. After a walker, it is very difficult for a child to maintain balance on his own, and subsequently it is quite difficult to correct this.

In walkers, the child occupies an unnatural position, he does not take a full step in them, but simply hangs, pushes off with his toes and moves in space. His brain and muscles remember this incorrect program of vertical position and movement, and later, when the child tries to start walking without a walker, these incorrect settings work for him, the wrong muscle groups that should keep him in an upright position turn on, and the child falls. After a walker, it is very difficult for a child to maintain balance on his own, and subsequently it is quite difficult to correct this.

- Another problem associated with the fact that the child was placed before he was ready is flat feet. Right?

- Flat feet can be congenital and functional (acquired).

If the child is placed too early, he may develop an incorrect foot placement. And often as a result, doctors diagnose flat-valgus deformity of the feet. This flat-valgus planting of the feet is usually not pathological. On examination, the doctor determines whether the foot is movable or rigid (inactive), and if the foot is movable, it is easily brought into the correction position, then we are not talking about deformity, this is just an incorrect setting, which is corrected by therapeutic exercises, the correct distribution of loads.

On examination, the doctor determines whether the foot is movable or rigid (inactive), and if the foot is movable, it is easily brought into the correction position, then we are not talking about deformity, this is just an incorrect setting, which is corrected by therapeutic exercises, the correct distribution of loads.

All these attitudes that mothers complain about: raking with toes, an apparent curvature of the limbs - this is a consequence of the transition of the child from a horizontal position to a vertical one and his adaptation to upright posture. During the prenatal period of development, the fetus is tightly “packed” inside the uterus: the arms are pressed to the body, and the legs are folded in a rather unnatural way for a person - the feet are turned inward, the bones of the lower leg and thigh are also twisted inward, and the hips in the hip joints, on the contrary, turn outward as much as possible . When the baby is just learning to stand, the incorrect position of the feet is imperceptible, because the turn of his legs in the hip joints and the twisting of the bones of the thighs and lower legs occurred in opposite directions - that is, they compensated for each other, and the feet seem to stand straight. Then the ratio in the hip joint begins to change - the head of the femur is centered, and this happens a little faster than the change in the rotation of the bones of the legs. And during this period, parents notice "clubfoot" and begin to worry. But in fact, in most cases, this is an absolutely normal stage of development, and there is no need to panic that the child somehow walks unevenly, puts his foot in the wrong way. Nature is smart, it has provided the whole mechanism for the development of the lower extremities, and you should not interfere in this process. Of course, if this worries you, then it makes sense to consult a doctor to determine whether these changes are physiological or pathological. If pathology - we treat, if physiology - no need to treat.

Then the ratio in the hip joint begins to change - the head of the femur is centered, and this happens a little faster than the change in the rotation of the bones of the legs. And during this period, parents notice "clubfoot" and begin to worry. But in fact, in most cases, this is an absolutely normal stage of development, and there is no need to panic that the child somehow walks unevenly, puts his foot in the wrong way. Nature is smart, it has provided the whole mechanism for the development of the lower extremities, and you should not interfere in this process. Of course, if this worries you, then it makes sense to consult a doctor to determine whether these changes are physiological or pathological. If pathology - we treat, if physiology - no need to treat.

For the prevention of incorrect installation of the foot, passive therapeutic exercises, the choice of the correct orthopedic regimen, are necessary.

A small child cannot yet actively fulfill the direct wishes of his parents and do gymnastics himself, therefore, at this stage, a passive effect is recommended: walking barefoot on uneven surfaces, on grass, on sand, on pebbles (of course, we make sure that the child is not injured, that the surfaces are safe). As the child grows up (after about three years), we move on to active exercise therapy in a playful way. For example, we run on our heels to wash our faces, to have breakfast on our toes, we go to the bedroom like a penguin, watch cartoons like a bear. Try to make it interesting for the child to do this, and then he will get used to it and will be happy to do the exercises himself.

As the child grows up (after about three years), we move on to active exercise therapy in a playful way. For example, we run on our heels to wash our faces, to have breakfast on our toes, we go to the bedroom like a penguin, watch cartoons like a bear. Try to make it interesting for the child to do this, and then he will get used to it and will be happy to do the exercises himself.

It is important for the correct installation of the foot and the selection of shoes. Shoes should be light, with an elastic sole, arch support - lined arch. If the arch on the sole is laid out, no additional insoles are needed (unless the doctor has prescribed). The height of the shoe is up to the ankle (you don’t need to buy high berets), so that the ankle can work freely and the short muscles of the lower leg can develop correctly - the very ones that hold the transverse and longitudinal arch of the foot.

For a child starting to walk, it is optimal that the shoes have a closed heel and toe - this is how the toes are protected from possible injuries if the child stumbles.

Is real flat feet treated differently?

- Yes, “real” flat feet cannot be cured by gymnastics. If this is congenital flat feet, then it is treated quite difficult and multi-stage. There are many surgical techniques that the doctor selects depending on the severity of the case and its characteristics. Treatment begins with staged plaster casts. There are minimally invasive surgical aids on the tendon-ligamentous apparatus with the subsequent use of special devices - brace. There are also various surgical benefits associated with intervention on the joints of the foot, aimed at correcting the ratio of the bones of the foot and eliminating plano-valgus deformity.

Why treat flat feet and clubfoot?

- Because these violations lead to the deformation of the entire skeleton. From the bottom up, like a snowball, there are violations. Incorrect support leads to incorrect installation of the hip, the position of the pelvis changes, the knee joints suffer, receiving a modified load. To even out the load on the knee joint, the hip begins to rotate, trying to bring some kind of support position. The hip turned around, began to dislocate from the hip joint. To prevent him from dislocating, the pelvis tilted. The pelvis tilted - the angle of inclination of the spine changed. Accordingly, the spine bent to leave the head straight. As a result: gross violations of gait and the entire musculoskeletal system, scoliotic deformities of the spine. These conditions do not pose a threat to life, but the quality of life in a person with orthopedic problems suffers greatly.

To even out the load on the knee joint, the hip begins to rotate, trying to bring some kind of support position. The hip turned around, began to dislocate from the hip joint. To prevent him from dislocating, the pelvis tilted. The pelvis tilted - the angle of inclination of the spine changed. Accordingly, the spine bent to leave the head straight. As a result: gross violations of gait and the entire musculoskeletal system, scoliotic deformities of the spine. These conditions do not pose a threat to life, but the quality of life in a person with orthopedic problems suffers greatly.

- Another very common diagnosis that is made to newborn children is torticollis. How serious is this pathology?

- Many children are diagnosed with neurogenic functional torticollis, often they are diagnosed with subluxation of the first cervical vertebra (C1). Most often, this is a functional disorder that resolves on its own with minimal intervention from us, and it does not pose any threat to the health of the child.

Children with functional torticollis are observed jointly by a neurologist and an orthopedist, usually corrective styling, an orthopedic pillow and a soft fixing collar are enough to resolve this situation without any complications.

Functional torticollis is important to separate from congenital muscular torticollis. If the latter is suspected, an ultrasound of the sternocleidomastoid muscles of the neck is performed in two months, which allows us to make the correct diagnosis with a high dose of probability. If an ultrasound examination reveals any changes in the sternocleidomastoid muscle, then we begin to conduct a comprehensive treatment aimed at eliminating torticollis and restoring the functional ability of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The treatment includes fixing the head with an orthopedic collar, physiotherapy courses are prescribed, aimed at improving muscle nutrition and restoring their structure. With unsuccessful conservative treatment, if the deformity increases, then after a year, surgical treatment of congenital muscular torticollis is performed.

If you have any doubts, questions, worries, do not be afraid to consult a doctor. A pediatric orthopedist, neurologist, pediatrician are specialists who are always ready to answer your questions and help your baby grow up healthy.

Elbow subluxation

A very common injury in children is subluxation of the head of the radius in the elbow joint. Three bones join at the elbow joint: the humerus, ulna, and radius. To hold these bones, there are ligaments. In young children, the ligaments are very elastic, loose and can easily slide over the bone. With age, the ligaments become stronger, and subluxation no longer occurs so easily.

This injury happens when the child is pulled sharply by the arm: dad twisted, just abruptly lifted the child by the wrists (the child must be lifted, supporting the armpits) or it even happens that the parent of the child is leading the hand, the baby slipped, hung on the arm - and subluxation occurs .

At the moment of injury, you can hear how the joint clicked. Usually, with an injury, the child experiences short-term sharp pain, which disappears almost immediately. The main sign of injury is that the child stops bending the arm at the elbow - children keep the injured arm fully extended.

Usually, with an injury, the child experiences short-term sharp pain, which disappears almost immediately. The main sign of injury is that the child stops bending the arm at the elbow - children keep the injured arm fully extended.

As soon as possible after the injury, the child should be shown to a traumatologist who will set the subluxation and return the ligament to its place.

When should I contact a traumatologist?

Children often fall, hit, get injured in one way or another. How to determine when you can get by with a band-aid and iodine, and when you need to go to the emergency room?

- Any cut, stab wound should be shown to the doctor. Do not fill the wound with brilliant green or iodine! This will add a chemical burn to the cut. It is not necessary to apply cotton wool to an open wound - its fibers are then extremely difficult to remove from the wound. If the injury site is heavily soiled, rinse with clean water.

Then cover the wound with a clean cloth (sterile bandage, handkerchief, etc.), apply a pressure bandage, and go to the emergency room as soon as possible. The doctor will carry out the primary surgical treatment of the wound, thoroughly clean it (you are unlikely to be able to do this on your own), restore the integrity of all structures and apply a bandage.

Then cover the wound with a clean cloth (sterile bandage, handkerchief, etc.), apply a pressure bandage, and go to the emergency room as soon as possible. The doctor will carry out the primary surgical treatment of the wound, thoroughly clean it (you are unlikely to be able to do this on your own), restore the integrity of all structures and apply a bandage. - If there is noticeable swelling at the site of injury. This may indicate that this is not just a bruise, but also a fracture, dislocation or rupture of the ligaments.

- If the child has lost consciousness, even briefly. This may indicate a traumatic brain injury, which can have serious consequences.

- If the child vomited after the injury. Vomiting, nausea, pallor also indicate the possibility of a traumatic brain injury.

- If a child hits his head. The consequences of a blow to the head may not be immediately noticeable, and at the same time have very serious consequences.

- If the child hits the stomach.

A blow to the stomach may damage internal organs and cause internal bleeding.

A blow to the stomach may damage internal organs and cause internal bleeding. - If a child falls from a height (from a chair, table, etc.), falls off a bicycle, etc. It happens that outwardly it does not manifest itself in any way, but internal organs are damaged.

- If the child is worried, behaves unusually.

In general - in case of any doubt, it is better to play it safe and see a doctor. Injuries in children is such a question when it is better, as they say, to overdo it than underdo it. There is no need to be shy, to be afraid that you are distracting ambulance doctors or emergency room doctors for nothing. Your child's health is the most important!

Beware of the trampoline!

Trampoline is a very popular entertainment among modern children. Unfortunately, this fun can lead to serious problems. The most common injury that children and teenagers get on trampolines is a compression fracture of the spine. Recently, there have been a lot of cases of compression fractures of the spine, including those who are professionally involved in trampoline sports.