Gay at birth

What causes sexual orientation?

In This Section

- Sexual Orientation

- What causes sexual orientation?

- How do I know my sexual orientation?

- What's "coming out"?

- What is homophobia?

Sexual orientation is a natural part of who you are — it’s not a choice. Your sexual orientation can change over your lifetime.

What causes sexual orientation?

It’s not completely known why someone might be lesbian, gay, straight, or bisexual. But research shows that sexual orientation is likely caused partly by biological factors that start before birth.

People don’t decide who they’re attracted to, and therapy, treatment, or persuasion won’t change a person’s sexual orientation. You also can’t “turn” a person gay. For example, exposing a boy to toys traditionally made for girls, such as dolls, won’t cause him to be gay.

You probably started to become aware of who you’re attracted to at a very young age. This doesn’t mean that you had sexual feelings, just that you could identify people you found attractive or liked. Many people say that they knew they were lesbian, gay, or bisexual even before puberty.

Although sexual orientation is usually set early in life, it isn’t at all uncommon for your desires and attractions to shift throughout your life. This is called “fluidity.” Many people, including sex researchers and scientists, believe that sexual orientation is like a scale with entirely gay on one end and entirely straight on the other. Lots of people would be not on the far ends, but somewhere in the middle.

This is called “fluidity.” Many people, including sex researchers and scientists, believe that sexual orientation is like a scale with entirely gay on one end and entirely straight on the other. Lots of people would be not on the far ends, but somewhere in the middle.

How many people are LGBTQ?

LGBTQ stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning.

Although researchers try to study how many people are LGBTQ, it’s very difficult to get an accurate number. This is because gender identity, sexual orientation, sexual identity, and sexual behavior are complicated for people. Let’s break it down:

-

Gender identity is who you feel you are inside and how you express those feelings through how you act, talk, dress, etc.

-

Sexual attraction is the romantic or sexual feelings you have toward others.

-

Sexual identity is how you label yourself (for example, using labels such as queer, gay, lesbian, straight, or bisexual).

-

Sexual behavior is who you have sex with and what kinds of sex you like to have.

Sometimes all of these things are in line for a person. For example, a woman may feel attracted only to women, identify as a lesbian, and have sexual relationships with only women.

But these things don’t always line up. Not everyone who has sexual feelings or attractions to the same gender will act on them. Some people may engage in same gender sexual behavior but not identify themselves as bisexual, lesbian, or gay. In some situations, coming out as LGBTQ can provoke fear and discrimination, and not everyone is comfortable coming out. For some people, sexual orientation can shift at different periods in their lives and the labels they use for themselves may shift, too.

So it’s difficult to measure how many people are LGBTQ when sexual orientation and gender are so complex for so many people. And not everyone feels safe or comfortable telling someone else that they’re LGBTQ.

Recent research suggests that 11% of American adults acknowledge at least some same-sex attraction, 8.2% report that they’ve engaged in same-sex behavior, but only 3.5% identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual. This shows that what people feel or do is not always the same as how they identify themselves.

We couldn't access your location, please search for a location.

Zip, City, or State

Please enter a valid 5-digit zip code or city or state.

Please fill out this field.

Service All Services Abortion Abortion Referrals Birth Control COVID-19 Vaccine HIV Services Men's Health Care Mental Health Morning-After Pill (Emergency Contraception) Pregnancy Testing & Services Primary Care STD Testing, Treatment & Vaccines Transgender Hormone Therapy Women's Health Care

Filter By All Telehealth In-person

Please enter your age and the first day of your last period for more accurate abortion options. Your information is private and anonymous.

Your information is private and anonymous.

I'm not sure This field is required.

AGE This field is required.

Or call 1-800-230-7526

‘I am gay – but I wasn’t born this way’

Loading

In Depth | Sexual Revolutions

‘I am gay – but I wasn’t born this way’

(Image credit: Getty Images)

By Brandon Ambrosino / Images by Ignacio Lehmann28th June 2016

Is sexuality purely the result of our biology? Brandon Ambrosino argues that simplistic explanations have ignored the fluid, shape-shifting nature of our desires.

“You can’t be gay.”

She was on top of me.

It wasn’t a command — it was a challenge. You so obviously cannot be gay, was her implication, because this is good sex.

It was 2006, a full five years before Lady Gaga would set the Born This Way argument atop its unassailable cultural perch, but even then the popular understanding of orientation was that it was something you were born with, something you couldn’t change. If you happened to engage in activity that ran counter to your sexual identity, then you had two options: you were lying to yourself and everyone else, or you were just experimenting.

If you happened to engage in activity that ran counter to your sexual identity, then you had two options: you were lying to yourself and everyone else, or you were just experimenting.

The sexual categories were rigid. Fixed. They weren’t subject to human imagination or experimentation – to the frustration of many sociologists, and kids, like myself, who found themselves inexplicably in bed with a player from the other team.

My sexual journey through college was anything but run-of-the-mill. I came out at a conservative Christian college in the US and was in a gay relationship for around two years with a basketball player who ended up marrying a woman. During that time, we both pal’d around with girls on the side. I even went so far as to fall in love with one. To this day, she and I joke about how she was the only girl I was ever in love with, and how I would’ve been quite happy marrying her.

As a writer, this kind of complicated story is incredibly interesting to me – mostly because it shows that my own personal history resists the kind of easy classifications that have come to dominate discussions of sexuality. Well, you must have been gay the whole time, some might think, and because of some religious shame, you decided to lie to yourself and experiment with a girl. But that was nothing more than a blip in the road. After all, most kids experiment with heterosexuality in college, don’t they?

Well, you must have been gay the whole time, some might think, and because of some religious shame, you decided to lie to yourself and experiment with a girl. But that was nothing more than a blip in the road. After all, most kids experiment with heterosexuality in college, don’t they?

If so, that ‘blip in the road’ has always been a thorn in my flesh. How do I explain that I was honestly in love with a woman? Some people might argue that I am innately bisexual, with the capacity to love both women and men. But that doesn’t feel like an accurate description of my sexual history, either.

I’m only speaking for myself here. But what feels most accurate to say is that I’m gay – but I wasn’t born this way.

Many people may find their desires changing direction - and it can't just be explained as experimentation (Credit: Ignacio Lehmann)

In 1977, just over 10% of Americans thought gayness was something you were born with, according to Gallup. That number has steadily risen over time and is currently somewhere between 42% and 50%, depending on the poll. Throughout the same period, the number of Americans who believe homosexuality is “due to someone’s upbringing/environment” fell from just under 60% to 37%.

Throughout the same period, the number of Americans who believe homosexuality is “due to someone’s upbringing/environment” fell from just under 60% to 37%.

These ideas reached critical mass in pop culture, first with Lady Gaga’s 2011 Born This Way and one year later with Macklemore’s Same Love, the chorus of which has a gay person singing “I can’t change even if I tried, even if I wanted to.” Videos started circulating on the internet featuring gay people asking straight people “when they chose to be straight.” Around the same time, the Human Rights Campaign declared unequivocally that “Being gay is not a choice,” and to claim that it is “gives unwarranted credence to roundly disproven practices such as conversion or reparative therapy.”

As Jane Ward notes in Not Gay: Sex Between Straight White Men, what’s interesting about many of these claims is how transparent their speakers are with their political motivations. “Such statements,” she writes, “infuse biological accounts with an obligatory and nearly coercive force, suggesting that anyone who describes homosexual desire as a choice or social construction is playing into the hands of the enemy. ” People who challenge the Born This Way narrative are often cast as homophobic, and their thinking is considered backward – even if they are themselves gay.

” People who challenge the Born This Way narrative are often cast as homophobic, and their thinking is considered backward – even if they are themselves gay.

Take, for example, Cynthia Nixon of Sex and The City fame. In a 2012 interview with New York Times Magazine, the actress casually mentioned that homosexuality was, for her, a choice. “I understand that for many people it’s not, but for me it’s a choice, and you don’t get to define my gayness for me.”

The blogger John Aravosis was one of many critics who pounced on Nixon. “Every religious right hatemonger is now going to quote this woman every single time they want to deny us our civil rights.” Aravosis leveled the same accusations against me in 2014 when I wrote a piece for The New Republic discussing my own complicated sexual history. Calling me “idiotic” and “patently absurd”, Aravosis wrote, “The gay haters at the religious right couldn’t have written it any better.”

Gay rights do not have to hinge on a genetic explanation for sexuality (Credit: Ignacio Lehmann)

For Aravosis, and many gay activists like him, the public will only accept and affirm gay people if they think they were born gay. And yet the available research does not support this view. Patrick Grzanka, Assistant Professor of Psychology at University of Tennessee, for instance, has shown that some people who believe that homosexuality is innate still hold negative views of gays. In fact, the homophobic and non-homophobic respondents he studied shared similar levels of belief in a Born This Way ideology.

And yet the available research does not support this view. Patrick Grzanka, Assistant Professor of Psychology at University of Tennessee, for instance, has shown that some people who believe that homosexuality is innate still hold negative views of gays. In fact, the homophobic and non-homophobic respondents he studied shared similar levels of belief in a Born This Way ideology.

As Samantha Allen notes at The Daily Beast, the growing public support for gays and lesbians has grown out of proportion with the rise in the number of people who believe homosexuality is fixed at birth; it would be unlikely that this small change in opinion could explain the spike in support for gay marriage, for instance. Instead, she suggests it hinges on the fact that far more people are now personally acquainted with someone who is gay. In 1985, only 24% of American respondents said they had a gay friend, relative or co-worker — in 2013, that number was at 75%. “It doesn’t seem to matter as much whether or not people believe that gay people are born that way as it does that they simply know someone who is currently gay,” Allen concludes.

In spite of these studies, those who push against Born This Way narratives have been heavily criticised by gay activists. “They tell me my own homo-negativity is being manifested in my work,” says Grzanka. Similarly, Ward has received her own hatemail for pushing against the ruling LGB narratives, with some gays telling her she’s “worse than Ann Coulter,” the controversial US author of books like If Democrats Had Any Brains, They’d Be Republicans. And when I published my essay on choosing to be gay, an irate American lesbian activist wrote me that it had “just been confirmed” to her that my writing was “directly responsible for four gay deaths in Russia.”

While I can understand why some contemporary activists (and the journalists who seem beholden to their agendas) might chalk up recent gains in LGB acceptance to Born This Way’s cultural infiltration, activism must be founded upon facts and truths, or the whole program will eventually turn out to be a sham. Drowning out every voice that dares to question dominant cultural narratives is not the same thing as invalidating the arguments those voices are making.

As Ward says, “Just because an argument is politically expedient doesn’t make it true.”

It is only in recent history that we have started to label sexual orientations with rigid categories (Credit: Ignacio Lehmann)

So what does the science say about Born This Way?

Let’s first be clear that whatever the origins of our sexual orientation, there is a unanimous opinion that gay “conversion therapy” should be rejected. These efforts are potentially harmful, according to the APA, “because they present the view that the sexual orientation of lesbian, gay and bisexual youth is a mental illness of disorder, and they often frame the inability to change one’s sexual orientation as a personal and moral failure.” Little wonder these therapies have been shown to provoke anxiety, depression and even suicide.

In other words, the question of the efficacy of conversion therapies is a non-issue. We condemn these efforts not just because we don’t think they work — perhaps anyone could be tortured into liking or disliking anything? — but because they’re immoral.

The question of what leads to homosexuality in the first place, however, is obscure, even to the experts. The APA, for example, while noting that most people experience little to no choice over their orientations, says this of homosexuality’s origins:

“Although much research has examined the possible genetic, hormonal, developmental, social and cultural influences on sexual orientation, no findings have emerged that permit scientists to conclude that sexual orientation is determined by any particular factor or factors.”

Similarly, the American Psychiatric Association writes in a 2013 statement that while the causes of heterosexuality and homosexuality are currently unknown, they are likely “multifactorial including biological and behavioral roots which may vary between different individuals and may even vary over time.”

True, various eye-grabbing headlines over the years have claimed that some scientists have found something like The Gay Gene. In 1991, for example, neuroscientist Simon LaVey published findings that he claimed suggest that “sexual orientation has a biological substrate. ” According to LeVay’s research, a specific part of the brain, the third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH-3), is smaller in homosexual men than it is in heterosexual men.

” According to LeVay’s research, a specific part of the brain, the third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH-3), is smaller in homosexual men than it is in heterosexual men.

Try as they might, scientists have struggled to identity any particular genes that consistently predict the directions of our love and desire (Credit: Ignacio Lehmann)

Read more

You can spot the problem with this study a mile away: were the gay brains LeVay studied born that way, or did they become that way? LeVay himself pointed this out to Discover Magazine in 1994: “Since I looked at adult brains, we don't know if the differences I found were there at birth or if they appeared later.” Further, the brains LeVay studied belonged to AIDS victims, so he couldn’t even be sure if what he was seeing had something to do with the disease.

Another landmark paper on the origins of homosexuality was published in 1993 by a geneticist named Dean Hamer, who was interested to learn whether homosexuality could be inherited. Beginning from his observation that there are more gay relatives on a mother’s side than a father’s, Hamer turned his attention to the X chromosome (which is passed on by the mother). He then recruited 40 pairs of gay brothers and got to work. What he found was that 33 of those brothers shared matching DNA in the Xq28, a region in the X chromosome. Hamer’s conclusion? He believes there’s about “99.5% certainty that there is a gene (or genes) in this area of the X chromosome that predisposes a male to become a heterosexual.”

Beginning from his observation that there are more gay relatives on a mother’s side than a father’s, Hamer turned his attention to the X chromosome (which is passed on by the mother). He then recruited 40 pairs of gay brothers and got to work. What he found was that 33 of those brothers shared matching DNA in the Xq28, a region in the X chromosome. Hamer’s conclusion? He believes there’s about “99.5% certainty that there is a gene (or genes) in this area of the X chromosome that predisposes a male to become a heterosexual.”

A 2015 study sought to confirm Hamer’s findings, this time with a much larger sample: 409 pairs of gay brothers. Researchers were pleased with their findings, which they claimed “support the existence of genes on… Xq28 influencing development of male sexual orientation.”

But not everyone finds the results convincing, according to Science. For one thing, the study relied on a technique called genetic linkage, which has been widely replaced by genome-wide association studies. It’s also noteworthy that Sanders himself urged his study to be viewed with a certain caution. “We don’t think genetics is the whole story,” he said. “It’s not.”

It’s also noteworthy that Sanders himself urged his study to be viewed with a certain caution. “We don’t think genetics is the whole story,” he said. “It’s not.”

And as Allen points out, there have also been studies that found no “X-linked gene underlying male homosexuality.” Perhaps predictably, these studies haven’t received as much media coverage.

Besides the individual critiques leveled against each new study announcing some gay gene discovery, there are major methodological criticisms to make about the entire enterprise in general, as Grzanka points out: “If we look at the ravenous pursuit, particularly among American scientists, to find a gay gene, what we see is that the conclusion has already been arrived at. All science is doing is waiting to find the proof.”

The other problem with Born This Way science is summed up nicely by Simon Copland: “Scientists are asking whether homosexuality is natural when we can’t even agree exactly what homosexuality is.”

Grzanka agrees. “If you know anything about social constructionism, then you know these sexual categories are very recent. How then could they be rooted in our genome?” Our desires may express themselves in many different ways that do not all conform to existing notions of ‘gay’, ‘straight’ or ‘bisexual’.

“If you know anything about social constructionism, then you know these sexual categories are very recent. How then could they be rooted in our genome?” Our desires may express themselves in many different ways that do not all conform to existing notions of ‘gay’, ‘straight’ or ‘bisexual’.

This is one of the best takeaways of Ward’s Not Gay, a penetrating analysis of sex between straight white men. Gay men make up only a fraction of the US population — yet Ward says that there are many men not included in that number who engage in homosexual behavior. Why, then, do some men who have sex with men identify as gay, and others identify as heterosexual? This question interests her far more than ‘how were they born?’.

Ward stresses that not all straight-identifying men who have sex with men are bisexual or closeted, and we do a disservice if we force those words on them. That’s because terms like ‘heterosexual’ and ‘straight’ and ‘bisexual’ and ‘gay’ come with all sorts of cultural baggage attached. Crucially, she argues, “whether or not this baggage is appealing is a separate matter altogether from the appeal of homosexual or heterosexual sex.”

Crucially, she argues, “whether or not this baggage is appealing is a separate matter altogether from the appeal of homosexual or heterosexual sex.”

Even if you accept that sexual desire may exist on a kind of spectrum, the predominant idea is still that these desires are innate and immutable – but this runs counter to what we know about human taste, says Ward. “Our desires are oriented and re-oriented based on our experiences throughout our lives.”

Gay or not, our desires are oriented and re-oriented throughout our lives (Credit: Ignacio Lehmann)

In fact, the straight-identified men Ward studied for her book sometimes found themselves in situations that sparked the desire for homosexual sex: fraternities, deployments, public restrooms, etc. But Ward doesn’t conclude these are somehow repressed or latent gay men. Rather, she argues that they — like all of us — have come to desire bodies and genitals within specific social contexts pregnant with “significant cultural and erotically charged meanings. ” In other words, what they want isn’t the “raw fact” of a man’s body, but what it represents in a certain context.

” In other words, what they want isn’t the “raw fact” of a man’s body, but what it represents in a certain context.

Why might we be uncomfortable asking whether and how much control we each possess over our “full range of erotic possibilities,” as Ward calls it? “What would it mean to think about people’s capacity to cultivate their own sexual desires, in the same way we might cultivate a taste for food?” she asks. Ward thinks this question is the next frontier of queer thought.

When I first said I chose to be gay, a queer American journalist challenged me to name the time and date of my choice. But this is an absurd way to look at desire. You might as well ask someone to name the exact moment they began liking Chaucer or disliking Hemingway. When did I begin to prefer lilies to roses? What time did the clock read at the exact moment I fell in love with my partner? All of our desires are continually being shaped throughout our lives, in the very specific contexts in which we discover and rehearse them.![]()

Thinking back to my college romances with women and men, I can begin to understand how my own experiences might have helped me to ‘cultivate’ my desire for homosexuality. I want to be very clear: I’m not claiming I simply began to ‘grow into’ my homosexuality, or that as I became more comfortable with being gay, I allowed myself the freedom to express what had always been latent within me. I’m claiming that at some point during college, my sexual and romantic desires became reoriented toward men. These desires suggested to me a queer identity, which I at first reluctantly accepted and then passionately embraced. This new identity in turn helped reinforce and grow new gay desires within me.

Granted, none of this means that there were no genetic or prenatal factors that went into the construction of my or any other sexual orientation. It just means that even if those factors exist, many more factors do too. So why not encourage conversations about those other things?

Humans aren’t who and what we are because of one gene. We’re who and what we are for a variety of reasons, and some of it might have something to do with how our genes randomly interact with our environments. But that’s not the whole story, and to engage in discourse that pretends it is — regardless of the nobility of the intentions — could have “profound and very negative consequences” for the LGBT community, says Grzanka.

We’re who and what we are for a variety of reasons, and some of it might have something to do with how our genes randomly interact with our environments. But that’s not the whole story, and to engage in discourse that pretends it is — regardless of the nobility of the intentions — could have “profound and very negative consequences” for the LGBT community, says Grzanka.

“Limiting our understanding of any complex human experience is always going to be worse than allowing it to be complicated,” he says.

Early gay rights activists compared sexuality to religion - a crucial part of our life that we should be free to practise however we like (Credit: Ignacio Lehamann)

So what are we to do with the Born This Way rhetoric? I would suggest that it’s time to build a more nuanced argument — regardless of how good a pop song the current one makes.

There are several reasons for this. Firstly, and most importantly, it’s just not the truth, as we currently understand it. The evidence to date offers no consensus that the Born This Way argument is the beginning and end of the story. We should stop pretending that it does.

We should stop pretending that it does.

Secondly, the entire search for a gay gene is predicated upon the assumption that homosexuality is not the natural or ‘default’ state of a developing human. ‘Something had to happen to make that man gay!’

But why cede such enormous ground to those who believe something has ‘gone wrong’ inside gay bodies and brains? For that matter, why play their game and pretend the only forms of difference that deserve justice are those we were born with? “That’s a very narrow understanding of what justice looks like,” says Ward.

What about the concern that homophobes will want to ‘encourage’ gay people to be straight if there’s no biological basis for sexuality? Let’s turn it around. Is it not equally true that ‘finding a gay gene’ might inspire the same homophobes to ‘find a cure’ for homosexuals? It doesn’t take too much creativity to imagine a scenario in which homophobic parents, upon being informed their fetus has ‘the gay gene’, choose what to them may seem the lesser of two evils: abortion.

Finally, I would argue that the Born This Way narrative can actively damage our perceptions of ourselves. In my sophomore year of college, I attended a Gay Student Alliance event at a nearby campus. It was the last meeting before Thanksgiving break, and the theme was coming out to your families. The idea was that the students would rehearse the coming out speech that they’d deliver while they were home. Student after student, while sobbing hysterically, said something like this: “Mom, you see how much pain this is causing me! Of course, I’d want to be straight if it were up to me. This is just who I am! You have to accept that because I can’t change that.”

I wanted to grab each of them and say, “Being gay is not a handicap. It’s OK to be queer even if you choose to be queer — and you should want to be queer! Because we are beautiful and fabulous.”

Ward sees this as a self-hating narrative. “Could you imagine if the dominant narrative of people of color was, ‘Well, of course I’d want to be white if I could. Wouldn’t everyone want to be white?’ That’s so racist! We’d never accept that story.”

Wouldn’t everyone want to be white?’ That’s so racist! We’d never accept that story.”

According to surveys, less than half of Generation Z identify as "100% heterosexual", suggesting more and more people have embraced their sexual fluidity (Credit: Ignacio Lehmann)

Perhaps it is time to look to the beginning of the gay rights movement. “Queer Nation and earlier movements in the US were not fundamentally organized around Born This Way explanations,” says Grzanka. “They were organized around sexual liberation, and the radical notion of challenging heteronormativity.”

Gay and lesbian activists, says Ward, used to draw on religion parallels to argue for inclusion. “People aren’t born with their religions. They’re born into religious cultures, and they can convert if they’d like. But there are still legal protections for them.” Eventually activists decided that argument wasn’t working fast enough, particularly in the shadow of the AIDS epidemic. “Then there was a shift, and the leaders of the movement chose to jump on board with a less nuanced argument that people already understood: just like race, people are born with their homosexuality. ”

”

Fortunately, we have now made enormous strides in understanding and affirming our queer sexualities. Some experts have even started using categories like ‘mostly straight’ and ‘mostly gay’ to try and expand our limited ways of viewing human sexuality. A recent UK poll from J. Walter Thompson Innovation group found that only 48% of Generation Z (ages 18-24) identify as “100% heterosexual.” Respondents were asked to rate themselves on a scale from zero (which signified “completely straight”) to six (“completely homosexual”). More than a third chose a number between one and five.

In response to the poll, one of my Facebook friends quipped about how natural selection must be working in overtime, what with making all of us gay! Indeed, as Ward notes, the Generation Z findings don’t signal some evolutionary shift over the last 15 years. Rather, they show that the times — the ‘nurture’ part of the nature/nurture dichotomy — are changing. Homosexuality isn’t considered taboo. Heterosexuality isn’t (always) considered the compulsory norm. And importantly, each isn’t always constructed in opposition to the other.

And importantly, each isn’t always constructed in opposition to the other.

I’m thankful for a new generation that is capable of imagining sexuality in a way that transcends the gay/straight binary, that couldn’t care less about what happened to their bodies and minds to make them who they are today. I’m hopeful that for this generation, sexual histories like mine and Cynthia Nixon’s aren’t seen as threatening, but liberating.

I don’t think I was born gay. I don’t think I was born straight. I was born the way all of us are born: as a human being with a seemingly infinite capacity to announce myself, to re-announce myself, to try on new identities like spring raincoats, to play with limiting categories, to challenge them and topple them, to cultivate my tastes and preferences, and, most importantly, to love and to receive love.

--

This story is part of our Sexual Revolutions series on our evolving understanding of sex and gender.

Brandon Ambrosino is a freelance journalist. He Tweets as @BrandonAmbro. Ignacio Lehmann is an Argentinian photographer who has travelled the globe for his 100 World Kisses project.

Join 600,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, Google+, LinkedIn and Instagram. If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Scientists: "re-educate" gays and lesbians will not work. They are born

Komsomolskaya Pravda

Nauokanauka: Club of curious

Yaroslav Korobatov

September 5, 2019 1:00

We deal with the biologist Alexander Panchin in the sensational study, which confirmed that Gay Gena does not exist

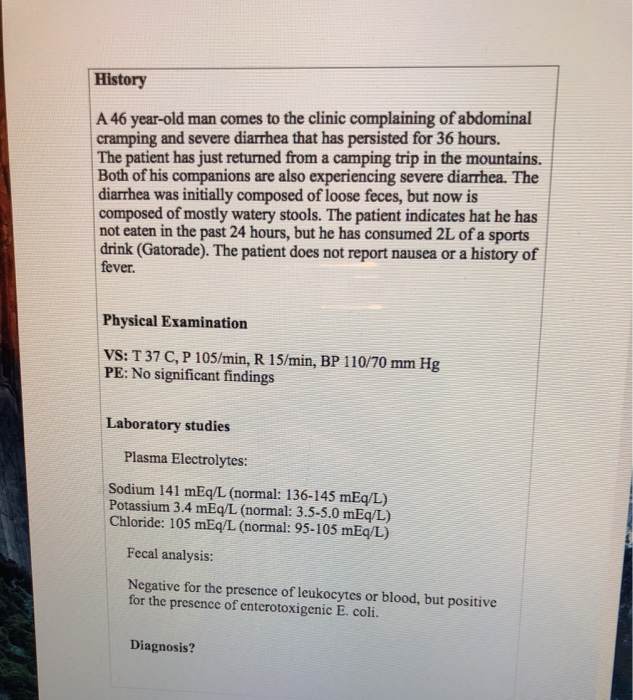

One of the modern theories of the formation of homosexual orientation suggests that prenatal development factors are responsible for this Photo: REUTERS

Not so long ago, a study was published in the journal Science about the relationship between genetics and non-traditional sexual orientation. It excited inquisitive Internet users. Everyone perceived its results in their own way. Some, having read that the "gay gene" does not exist, realized that it was time to "re-educate" representatives of sexual minorities. Others regarded the publication as the first proof of the genetic nature of this phenomenon. What do scientists really want to say? We decided to figure this out together with Candidate of Biological Sciences Alexander Panchin , Senior Researcher at the Molecular Evolution Sector of the Institute for Information Transmission Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences and a well-known popularizer of science.

It excited inquisitive Internet users. Everyone perceived its results in their own way. Some, having read that the "gay gene" does not exist, realized that it was time to "re-educate" representatives of sexual minorities. Others regarded the publication as the first proof of the genetic nature of this phenomenon. What do scientists really want to say? We decided to figure this out together with Candidate of Biological Sciences Alexander Panchin , Senior Researcher at the Molecular Evolution Sector of the Institute for Information Transmission Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences and a well-known popularizer of science.

People confuse genetic and congenital

- Alexander, the news that genes are only 25 percent responsible for non-traditional sexual behavior was perceived by many as a statement that gays are not born, but become. Is this the correct conclusion from what the authors wrote?

- No, this does not follow from the study. This is probably where people get confused between "genetic" and "innate". Not everything that is innate is genetic. One of the modern theories of the formation of homosexual orientation suggests that prenatal development factors are responsible for this. For example, such an effect is known: if a woman has already given birth to boys, then the likelihood that subsequent sons will have a homosexual orientation increases. And it increases significantly. This phenomenon is explained by the immunological hypothesis of sexual orientation, which states that during the development of a male fetus, the mother may form antibodies to some male-specific antigens. And these antibodies trigger a mechanism that affects the development of the brain. But genetics has nothing to do with these factors of intrauterine development. It is also worth adding that an estimate of 8-25 percent is by no means the contribution of all genetic factors to people's sexual behavior. The authors of the study looked at variations only in some (by far not all!) DNA regions.

This is probably where people get confused between "genetic" and "innate". Not everything that is innate is genetic. One of the modern theories of the formation of homosexual orientation suggests that prenatal development factors are responsible for this. For example, such an effect is known: if a woman has already given birth to boys, then the likelihood that subsequent sons will have a homosexual orientation increases. And it increases significantly. This phenomenon is explained by the immunological hypothesis of sexual orientation, which states that during the development of a male fetus, the mother may form antibodies to some male-specific antigens. And these antibodies trigger a mechanism that affects the development of the brain. But genetics has nothing to do with these factors of intrauterine development. It is also worth adding that an estimate of 8-25 percent is by no means the contribution of all genetic factors to people's sexual behavior. The authors of the study looked at variations only in some (by far not all!) DNA regions. If we take the cumulative contribution, then the genes explain the variation in sexual behavior in 34-39percent of men and 18-19 percent of women. That will be more accurate.

If we take the cumulative contribution, then the genes explain the variation in sexual behavior in 34-39percent of men and 18-19 percent of women. That will be more accurate.

- It turns out that the manifestation of an innate trait - in this case, same-sex orientation - is the "zone of responsibility" of natural mechanisms? And it does not depend either on the personal will and choice of a person, or on his lifestyle and upbringing?

- Let's say this: we know for sure that sexual orientation is influenced by genetic mechanisms and factors of intrauterine development. No one can really influence this. So far, no examples have been shown in the scientific literature that prove the possibility of changing the sexual orientation of an already born person. Maybe they are, but we don't know about it.

"Re-educating" gays and lesbians will not work. They are born this way.

- Yes, it is biologically meaningless. Because, again, we do not know how to influence the sexual orientation of a teenager or an adult. Another thing is that it is possible to change people's attitude towards representatives of sexual minorities. It is clear that if the media say that these people are somehow not correct, then they may be treated worse. It seems to me that such laws in themselves create problems in society that might not exist.

Another thing is that it is possible to change people's attitude towards representatives of sexual minorities. It is clear that if the media say that these people are somehow not correct, then they may be treated worse. It seems to me that such laws in themselves create problems in society that might not exist.

- But the authors of the study write: "...some of our findings also point to the importance of sociocultural context." For example, they found that same-sex orientation was associated with personality traits such as loneliness and risk-taking. Such people are more likely to have mental problems - they suffer more from depression, they are more likely to develop schizophrenia ...

- Statistical dependence does not necessarily mean the presence of causal relationships. A simple example: you can always find a relationship between the consumption of expensive products and life expectancy. But the point is not that the delicacies themselves are very useful, but simply this person has a lot of money and he can also afford good medicine. How can the behavioral characteristics of representatives of sexual minorities be explained? Obviously, how a person is perceived by society and how he feels in it is closely related to his sexual orientation. Maybe that's where the depression comes from. Here it is necessary to study exactly how personality traits are associated with sexual orientation. As far as I understand, this study did not set itself such a goal.

How can the behavioral characteristics of representatives of sexual minorities be explained? Obviously, how a person is perceived by society and how he feels in it is closely related to his sexual orientation. Maybe that's where the depression comes from. Here it is necessary to study exactly how personality traits are associated with sexual orientation. As far as I understand, this study did not set itself such a goal.

Even eye color is controlled by several genes

- Still, a study published in Science, is this an argument in favor of the genetic nature of this phenomenon, or rather not?

- And this is not about this or that at all. They did not have a global task to assess the overall contribution of genes. They looked for specific genetic variations that would be well associated with same-sex sexual behavior. As a result, they found several combinations, but still this does not allow to say in advance whether a person will be born with a traditional sexual orientation or not. In principle, after the release of the study, the global picture of the world did not change at all. The fact that there is no single gene that would trigger the mechanism of sexual behavior has long been known. Even something as simple as eye color is controlled by a few genes. And here we are talking about a much more complex phenomenon.

In principle, after the release of the study, the global picture of the world did not change at all. The fact that there is no single gene that would trigger the mechanism of sexual behavior has long been known. Even something as simple as eye color is controlled by a few genes. And here we are talking about a much more complex phenomenon.

- Researchers say there is "no gay gene" but a "complex genetic architecture" of sexual behavior. What is meant?

- Suppose you want to bake a cake. The taste of this cake will depend on the number of apples, the quality of the flour, the number of eggs you have added, the temperature inside the oven... That is, many factors will affect the final result. It's the same with genes, you have a lot of genetic variants, they all contribute to some extent, but each one does not dominate.

SEE ALSO

Homosexuality is only a quarter dependent on genes

It is believed that at all times in all human societies from 2 to 10 percent of citizens adhered to non-traditional sexual orientation. However, perhaps many of our readers are ready to argue with this statement. For example, among sports fans there is a widespread belief that among football and hockey referees the number of supporters of same-sex relationships is much higher than the average value (this is a joke - Auth). Nevertheless, people have long been tormented by the question: is homosexuality a genetic failure or the result of some life collisions? For example, cultural influence, female upbringing or, God forbid, promotion of homosexuality? Let's say a man watched a satanic film "Brokeback Mountain", kicked his wife out of the house and went all out with local cowboys... (details)

However, perhaps many of our readers are ready to argue with this statement. For example, among sports fans there is a widespread belief that among football and hockey referees the number of supporters of same-sex relationships is much higher than the average value (this is a joke - Auth). Nevertheless, people have long been tormented by the question: is homosexuality a genetic failure or the result of some life collisions? For example, cultural influence, female upbringing or, God forbid, promotion of homosexuality? Let's say a man watched a satanic film "Brokeback Mountain", kicked his wife out of the house and went all out with local cowboys... (details)

Age category of the site 18+

The online publication (website) is registered by Roskomnadzor, certificate El No. FS77-80505 dated March 15, 2021.

I.O. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF THE SITE - KANSKY VICTOR FYODOROVICH.

THE AUTHOR OF THE MODERN VERSION OF THE EDITION IS SUNGORKIN VLADIMIR NIKOLAEVICH.

Messages and comments from site readers are posted without preliminary editing. The editors reserve the right to remove them from the site or edit them if the specified messages and comments are an abuse of freedom mass media or violation of other requirements of the law.

JSC "Publishing House "Komsomolskaya Pravda". TIN: 7714037217 PSRN: 1027739295781 127015, Moscow, Novodmitrovskaya d. 2B, Tel. +7 (495) 777-02-82.

Exclusive rights to materials posted on the website www.kp.ru, in accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation for the Protection of the Results of Intellectual Activity belong to JSC Publishing House Komsomolskaya Pravda, and do not be used by others in any way form without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Acquisition of copyright and contact with the editors: [email protected]

Science: Science and technology: Lenta.ru

An international team of scientists analyzed the entire human genome for the first time to find DNA that determines the sexual orientation of men. Scientists have discovered two genetic variants associated with homosexuality and encoding proteins involved in the functioning of the brain and thyroid gland. Lenta.ru figured out a study published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Scientists have discovered two genetic variants associated with homosexuality and encoding proteins involved in the functioning of the brain and thyroid gland. Lenta.ru figured out a study published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Sexual orientation is largely influenced by upbringing, early childhood experiences, propaganda and cultural influences. More and more researchers around the world are coming to this conclusion. The main causes of homosexuality are genetic, hormonal and characteristics of the intrauterine environment, no one can cope with them.

In the vast majority of people, combinations of XX and XY sex chromosomes provide a reliable indicator of sexual orientation. However, the human body is complex enough not to allow for variation. In a population there is always a proportion of men (3-4 percent) whose orientation does not correspond to the biological sex.

What evidence do you have

In August 1986, an article in the Archives of General Psychiatry by psychiatrists Richard Pillard and James Weinrich of Boston University demonstrated the heritability of homosexuality. The study involved 51 gay and 50 heterosexual men, and all of the volunteers had brothers. It turned out that gay men are four times more likely to have a homosexual brother than heterosexual men.

The study involved 51 gay and 50 heterosexual men, and all of the volunteers had brothers. It turned out that gay men are four times more likely to have a homosexual brother than heterosexual men.

In 1991 another article by Pillard was published in the same journal. This time, the study took into account whether gay brothers are identical or regular, heterozygous. If homosexuality is indeed an inherited trait, then homozygous twins (developed from the same egg fertilized by the same sperm) should be more likely to share the same sexual orientation than heterozygous brothers. And it turned out: in twins, this figure is 30 percent higher.

In 2010, a large-scale study of almost all twins in Sweden (about 7600 people) was carried out. According to the findings of scientists, homosexual behavior is associated with both hereditary factors and environmental factors (intrauterine conditions, illness and injury, and sexual experience). Orientation is also influenced by social factors, but to a lesser extent.

In terms of genetics, back in 1993, researchers from the National Institutes of Health, led by Dean Hamer, published an article in Science demonstrating the relationship of male homosexuality with the X chromosome. 114 gay families were studied and it was found that homosexual orientation is more common among maternal uncles and cousins than among paternal relatives. In 64 percent of cases, homosexuality, according to the findings of scientists, is associated with the genetic marker Xq28 (a region on the X chromosome that includes several genes).

Photo: Radovan Stoklasa / Reuters

These results were challenged by a Canadian team led by George Rice who found no statistically significant relationship between homosexuality and Xq28 in a study of 52 pairs of homosexual brothers. Rice's work has been criticized for methodological errors that failed to reveal this connection. In 2012, a large study involving 409 pairs of gay brothers by several independent groups of scientists confirmed Hamer's findings. Moreover, the connection of male homosexuality was revealed not only with Xq28, but also with the centromere of the 8th chromosome. "The results indicate that genetic differences in each of these regions influence the development of important psychological traits associated with male sexual orientation," the researchers noted. However, no specific genes were found then.

Moreover, the connection of male homosexuality was revealed not only with Xq28, but also with the centromere of the 8th chromosome. "The results indicate that genetic differences in each of these regions influence the development of important psychological traits associated with male sexual orientation," the researchers noted. However, no specific genes were found then.

Actively searching

In the new work, the same researchers for the first time resorted to genome-wide association search (GWAS), when the relationship between genomic variants and phenotypic traits is revealed. The genomes of two large groups of people are compared, one of which includes volunteers with the desired traits. Scientists are checking how significant differences are in the frequency distribution of gene variants that differ from each other by single nucleotide mutations. According to the authors, so far no paper has been published in peer-reviewed journals using GWAS to search for hereditary factors in homosexuality.

The study involved 1109 homosexual and 1231 heterosexual men from European countries. Orientation was determined from the words of the volunteers themselves. The scientists genotyped each participant's DNA samples to identify DNA differences across nearly 500,000 single nucleotide mutations, and performed a statistical analysis of the data.

Specialists were only interested in associations obtained at a significance level (p-value), which indicates the probability of a random result (if there is no connection) of 10 −5 –10 −7 , which is approximately an order of magnitude less than required. Such strict criteria are explained by the fact that at a higher level of significance there will be too many false associations. However, with a relatively small sample (two thousand people), an overly low p-value would not allow significant results to be achieved.

Photo: Carlos Jasso / Reuters

Who is the culprit

It turned out that homosexuality is associated with two areas.