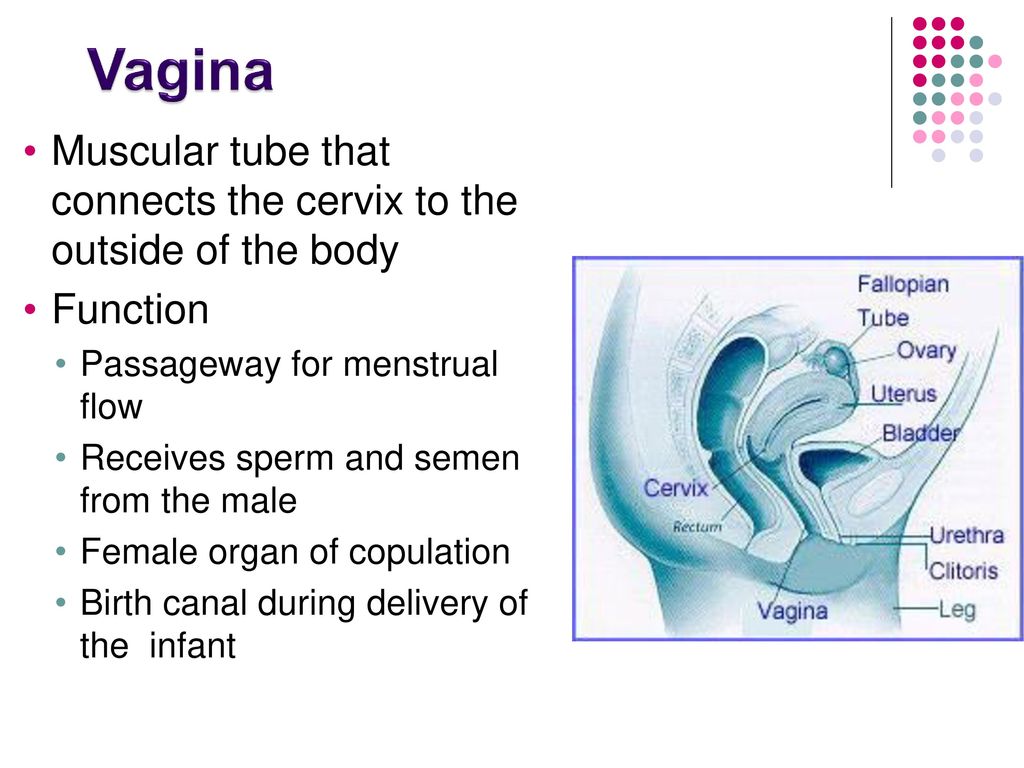

Female birth canal

Your baby in the birth canal Information | Mount Sinai

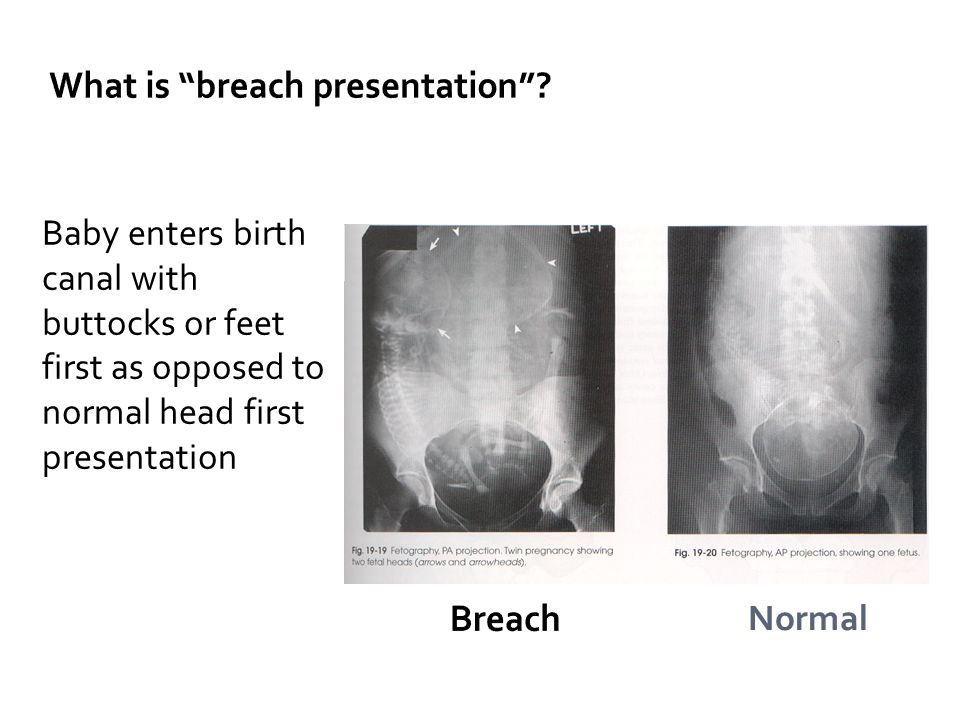

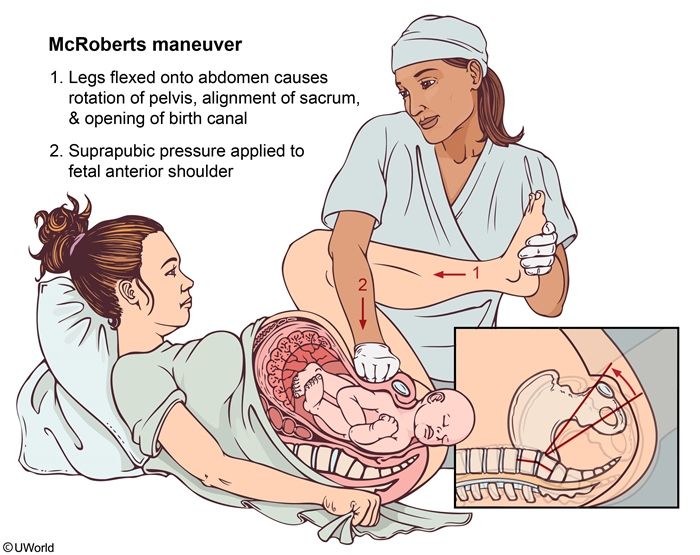

Shoulder presentation; Malpresentations; Breech birth; Cephalic presentation; Fetal lie; Fetal attitude; Fetal descent; Fetal station; Cardinal movements; Labor-birth canal; Delivery-birth canal

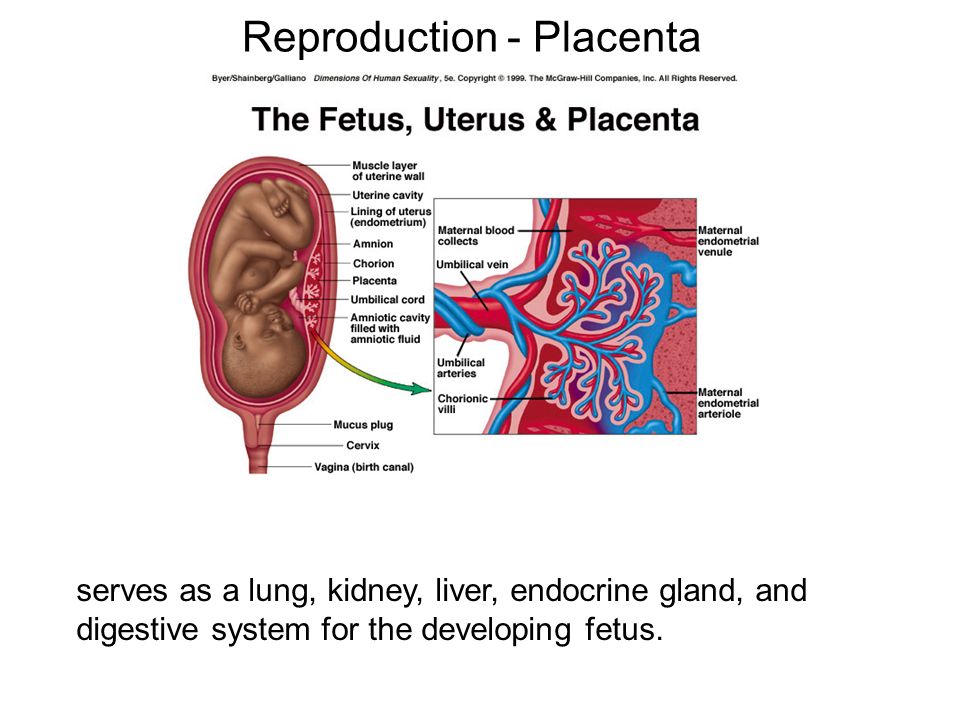

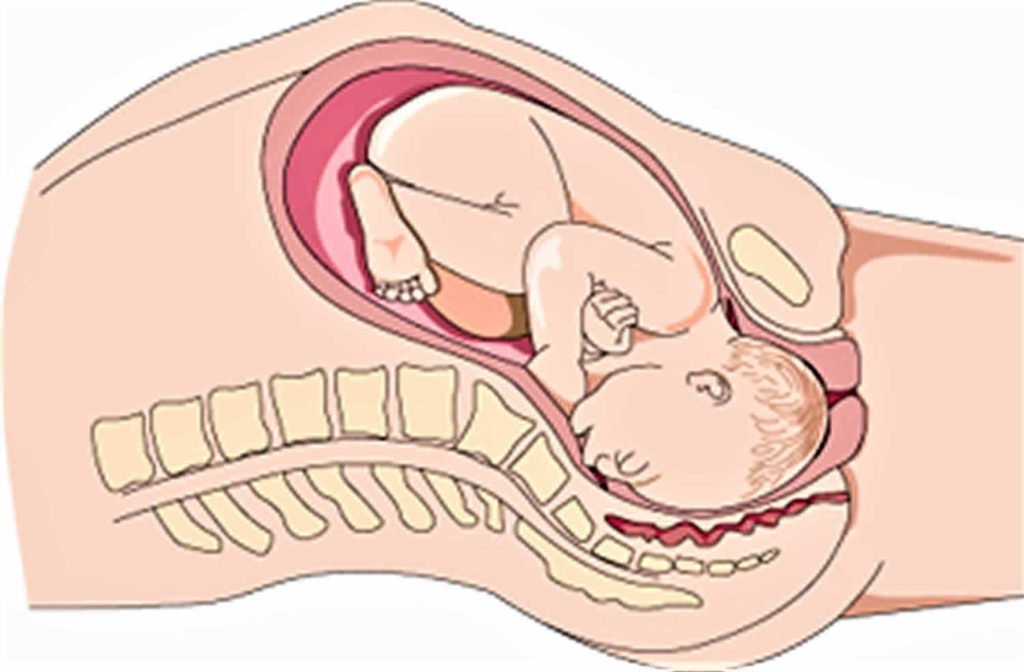

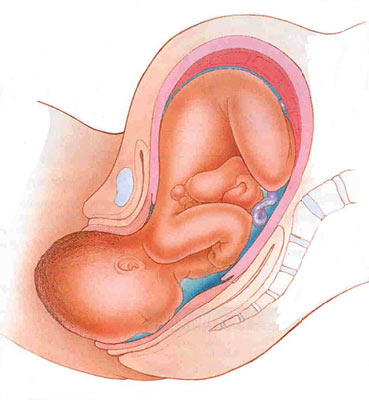

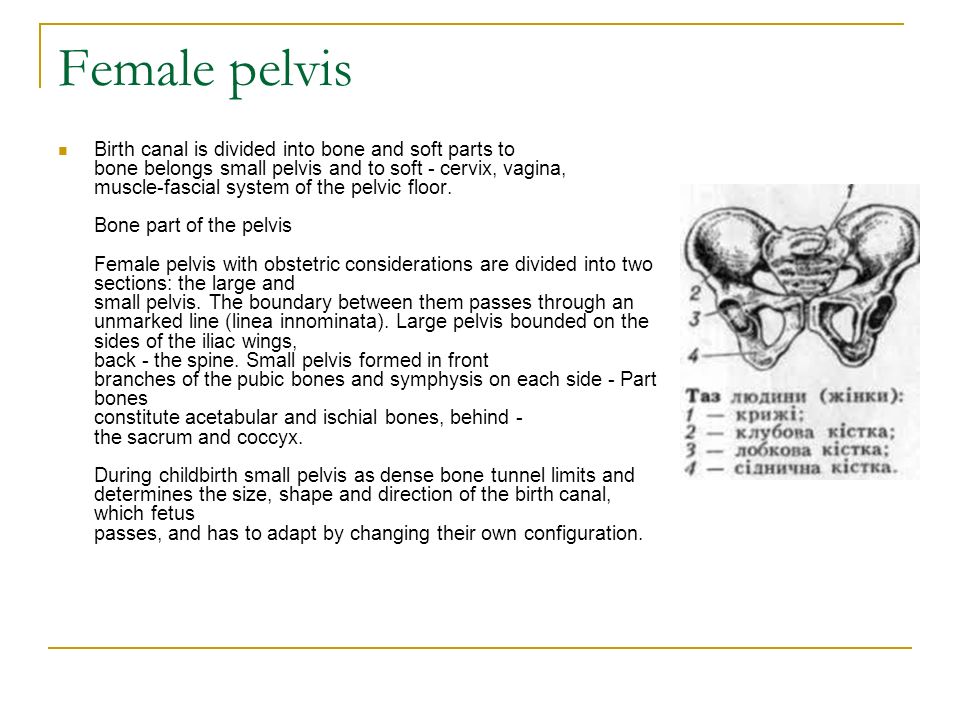

During labor and delivery, your baby must pass through your pelvic bones to reach the vaginal opening. The goal is to find the easiest way out. Certain body positions give the baby a smaller shape, which makes it easier for your baby to get through this tight passage.

The best position for the baby to pass through the pelvis is with the head down and the body facing toward the mother's back. This position is called occiput anterior.

Childbirth is really a series of four stages that culminate in the actual birth and short period thereafter. For more specific information regarding emergency delivery see the information on childbirth, emergency delivery.

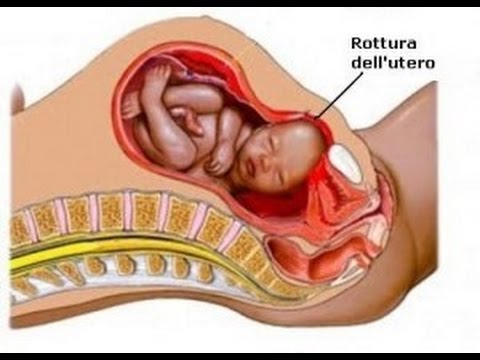

Emergency measures are indicated when childbirth is imminent and no health care professional is present. Indications of late labor include rupturing of the amniotic sac, dilation of the cervix, and appearance of the baby's head at the vaginal opening.

Emergency measures are indicated when childbirth is imminent and no health care professional is present. Indications of late labor include rupturing of the amniotic sac, dilation of the cervix, and appearance of the baby's head at the vaginal opening.

Cephalic (head first) presentation is considered normal, but a breech (feet or buttocks first) delivery can be very difficult, even dangerous for the mother and the baby.

In a normal pregnancy, the baby is positioned head down in the uterus.

The term fetal presentation refers to the part of your baby's body that is closest to the birth canal. In most full-term pregnancies, the baby is positioned head down, or cephalic, in the uterus.

Information

Certain terms are used to describe your baby's position and movement through the birth canal.

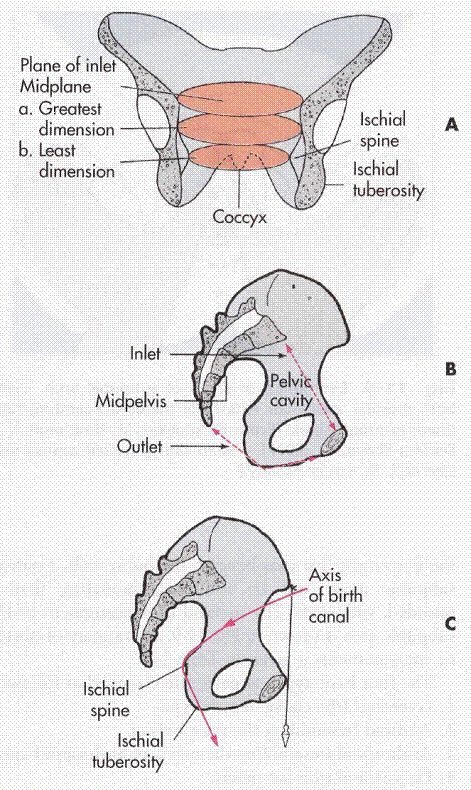

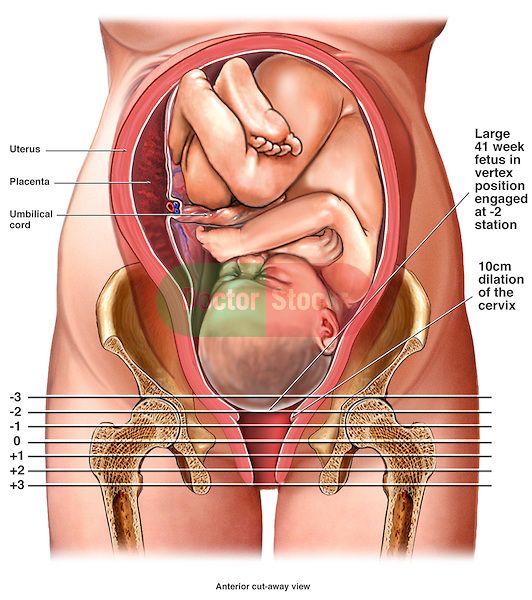

FETAL STATION

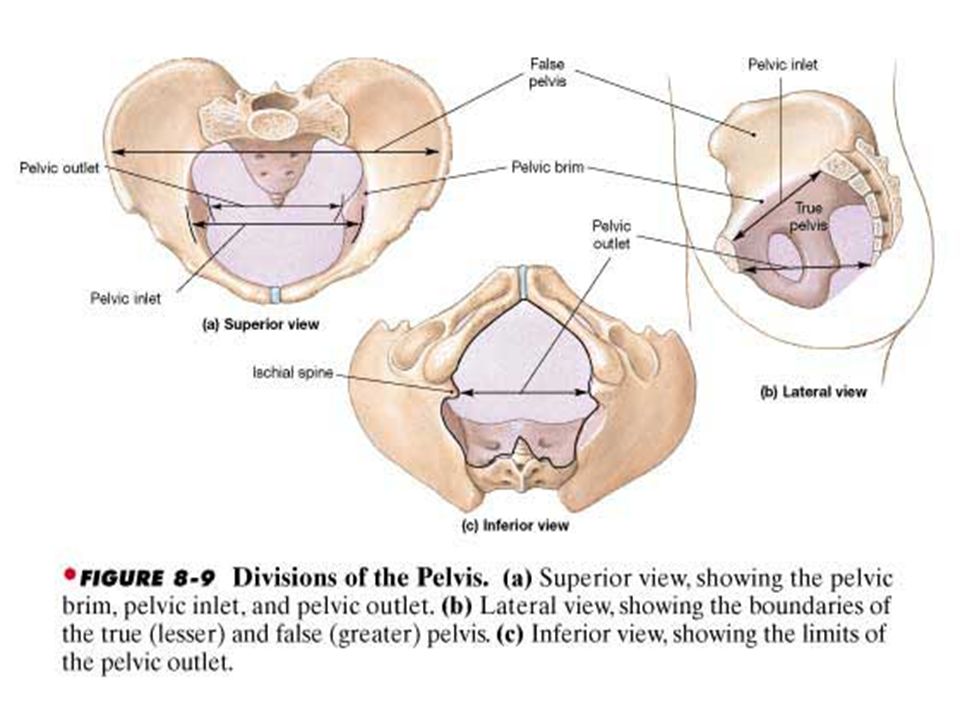

Fetal station refers to where the presenting part is in your pelvis.

- The presenting part. The presenting part is the part of the baby that leads the way through the birth canal. Most often, it is the baby's head, but it can be a shoulder, the buttocks, or the feet.

- Ischial spines. These are bone points on the mother's pelvis. Normally the ischial spines are the narrowest part of the pelvis.

- 0 station. This is when the baby's head is even with the ischial spines. The baby is said to be "engaged" when the largest part of the head has entered the pelvis.

- If the presenting part lies above the ischial spines, the station is reported as a negative number from -1 to -5.

In first-time moms, the baby's head may engage by 36 weeks into the pregnancy. However, engagement may happen later in the pregnancy, or even during labor.

FETAL LIE

This refers to how the baby's spine lines up with the mother's spine. Your baby's spine is between his head and tailbone.

Your baby will most often settle into a position in the pelvis before labor begins.

- If your baby's spine runs in the same direction (parallel) as your spine, the baby is said to be in a longitudinal lie. Nearly all babies are in a longitudinal lie.

- If the baby is sideways (at a 90-degree angle to your spine), the baby is said to be in a transverse lie.

FETAL ATTITUDE

The fetal attitude describes the position of the parts of your baby's body.

The normal fetal attitude is commonly called the fetal position.

- The head is tucked down to the chest.

- The arms and legs are drawn in towards the center of the chest.

Abnormal fetal attitudes include a head that is tilted back, so the brow or the face presents first. Other body parts may be positioned behind the back. When this happens, the presenting part will be larger as it passes through the pelvis. This makes delivery more difficult.

DELIVERY PRESENTATION

Delivery presentation describes the way the baby is positioned to come down the birth canal for delivery.

The best position for your baby inside your uterus at the time of delivery is head down. This is called cephalic presentation.

- This position makes it easier and safer for your baby to pass through the birth canal. Cephalic presentation occurs in about 97% of deliveries.

- There are different types of cephalic presentation, which depend on the position of the baby's limbs and head (fetal attitude).

If your baby is in any position other than head down, your doctor may recommend a cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation is when the baby's bottom is down. Breech presentation occurs about 3% of the time. There are a few types of breech:

- A complete breech is when the buttocks present first and both the hips and knees are flexed.

- A frank breech is when the hips are flexed so the legs are straight and completely drawn up toward the chest.

- Other breech positions occur when either the feet or knees present first.

The shoulder, arm, or trunk may present first if the fetus is in a transverse lie. This type of presentation occurs less than 1% of the time. Transverse lie is more common when you deliver before your due date, or have twins or triplets.

CARDINAL MOVEMENTS OF LABOR

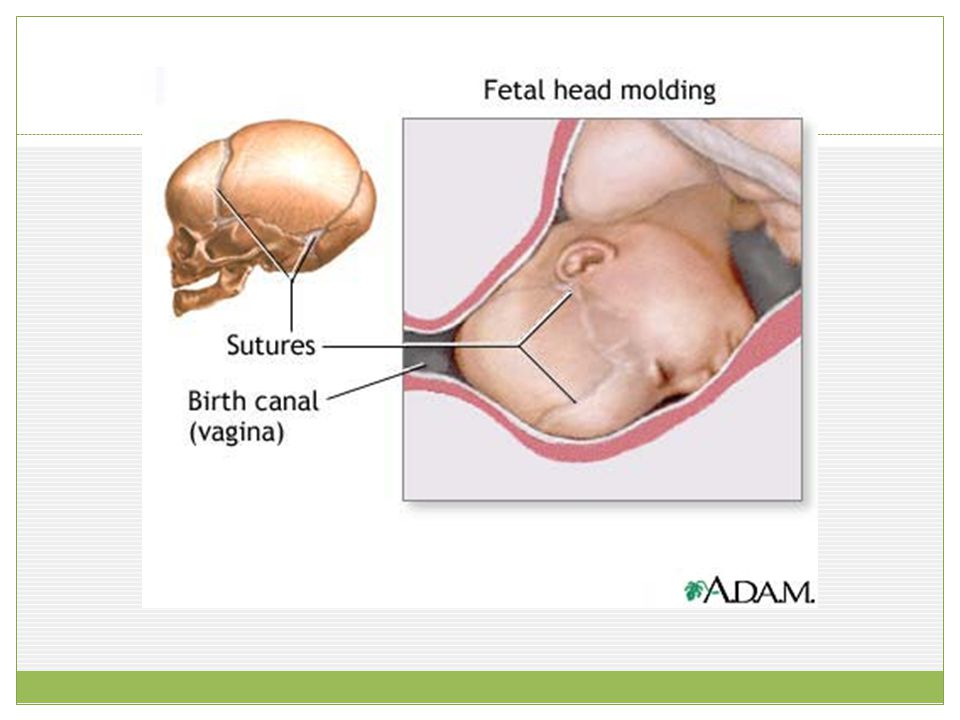

As your baby passes through the birth canal, the baby's head will change positions. These changes are needed for your baby to fit and move through your pelvis. These movements of your baby's head are called cardinal movements of labor.

Engagement

- This is when the widest part of your baby's head has entered the pelvis.

- Engagement tells your health care provider that your pelvis is large enough to allow the baby's head to move down (descend).

Descent

- This is when your baby's head moves down (descends) further through your pelvis.

- Most often, descent occurs during labor, either as the cervix dilates or after you begin pushing.

Flexion

- During descent, the baby's head is flexed down so that the chin touches the chest.

- With the chin tucked, it is easier for the baby's head to pass through the pelvis.

Internal Rotation

- As your baby's head descends further, the head will most often rotate so the back of the head is just below your pubic bone. This helps the head fit the shape of your pelvis.

- Usually, the baby will be face down toward your spine.

- Sometimes, the baby will rotate so it faces up toward the pubic bone.

- As your baby's head rotates, extends, or flexes during labor, the body will stay in position with one shoulder down toward your spine and one shoulder up toward your belly.

Extension

- As your baby reaches the opening of the vagina, usually the back of the head is in contact with your pubic bone.

- At this point, the birth canal curves upward, and the baby's head must extend back. It rotates under and around the pubic bone.

External Rotation

- As the baby's head is delivered, it will rotate a quarter turn to be in line with the body.

Expulsion

- After the head is delivered, the top shoulder is delivered under the pubic bone.

- After the shoulder, the rest of the body is usually delivered without a problem.

Barth WH. Malpresentations and malposition. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 17.

8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 17.

Kilpatrick SJ, Garrison E, Fairbrother E. Normal labor and delivery. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 11.

Last reviewed on: 12/3/2020

Reviewed by: LaQuita Martinez, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Emory Johns Creek Hospital, Alpharetta, GA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

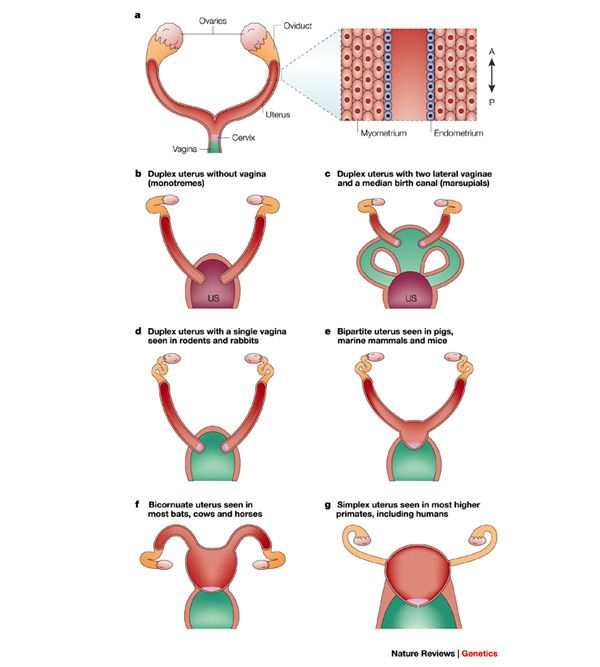

Human variation in the shape of the birth canal is significant and geographically structured

1. Schultz AH. 1949. Sex differences in the pelves of primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 7, 401–424. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330070307) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Leutenegger W. 1974. Functional aspects of pelvic morphology in simian Primates. J. Hum. Evol. 3, 207–222. ( 10.1016/0047-2484(74)90179-1) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Rosenberg K, Trevathan W. 1995. Bipedalism and human birth: the obstetrical dilemma revisited. Evol. Anthropol. 4, 161–168. ( 10.1002/evan.1360040506) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Rosenberg K, Trevathan W. 1995. Bipedalism and human birth: the obstetrical dilemma revisited. Evol. Anthropol. 4, 161–168. ( 10.1002/evan.1360040506) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Trevathan W, Rosenberg K. 2000. The shoulders follow the head: postcranial constraints on human childbirth. J. Hum. Evol. 39, 583–586. ( 10.1006/jhev.2000.0434) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Dunsworth HM, Warrener AG, Deacon T, Ellison PT, Pontzer H. 2012. Metabolic hypothesis for human altriciality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15 212–15 216. ( 10.1073/pnas.1205282109) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Wall-Scheffler CM. 2012. Energetics, locomotion, and female reproduction: implications for human evolution. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 41, 71–85. ( 10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145739) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Warrener AG, Lewton KL, Pontzer H, Lieberman DE. 2015. A wider pelvis does not increase locomotor cost in humans, with implications for the evolution of childbirth. PLoS ONE 10, e0118903 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0118903) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

PLoS ONE 10, e0118903 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0118903) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Washburn SL. 1960. Tools and human evolution. Sci. Am. 203, 3–15. ( 10.1038/scientificamerican0960-62) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Abitbol MM. 1991. Ontogeny and evolution of pelvic diameters in anthropoid primates and in Australopithecus afarensis (AL 288-1). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 85, 135–148. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330850203) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Ruff C. 1995. Biomechanics of the hip and birth in early Homo. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 98, 527–574. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330980412) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Rosenberg KR. 1992. The evolution of modern human childbirth. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 35, 89–124. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330350605) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Caldwell WE, Moloy HC. 1933. Anatomical variations in the female pelvis and their effect in labor with a suggested classification. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 26, 479–505. ( 10.1016/S0002-9378(33)90194-5) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Gynecol. 26, 479–505. ( 10.1016/S0002-9378(33)90194-5) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Greulich WW, Thoms H. 1938. The dimensions of the pelvic inlet of 789 white females. Anat. Rec. 72, 45–51. ( 10.1002/ar.1090720105) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Jagani N, Schulman H, Chandra P, Gonzalez R, Fleischer A. 1981. The predictability of labor outcome from a comparison of birth weight and X-ray pelvimetry. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 139, 507–511. ( 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90508-1) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Stålberg K, Bodestedt Å, Lyrenås S, Axelsson O. 2006. A narrow pelvic outlet increases the risk for emergency cesarean section. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 85, 821–824. ( 10.1080/00016340600593521) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Steer CM. 1975. Moloy's evaluation of the pelvis in obstetrics, 3rd edn New York, NY: Plenum Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

17. Kurki HK. 2013. Skeletal variability in the pelvis and limb skeleton of humans: does stabilizing selection limit female pelvic variation? Am. J. Hum. Biol. 25, 795–802. ( 10.1002/ajhb.22455) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Hum. Biol. 25, 795–802. ( 10.1002/ajhb.22455) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Wells JCK, DeSilva JM, Stock JT. 2012. The obstetric dilemma: an ancient game of Russian roulette, or a variable dilemma sensitive to ecology? Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 149, 40–71. ( 10.1002/ajpa.22160) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Handa VL, Lockhart ME, Fielding JR, Bradley CS, Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Ye W, Richter HE. 2008. Racial differences in pelvic anatomy by magnetic resonance imaging. Obstet. Gynecol. 111, 914–920. ( 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318169ce03) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Kurki HK. 2013. Bony pelvic canal size and shape in relation to body proportionality in humans. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 151, 88–101. ( 10.1002/ajpa.22243) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Patriquin ML, Steyn M, Loth SR. 2002. Metric assessment of race from the pelvis in South Africans. Forensic Sci. Int. 127, 104–113. ( 10.1016/S0379-0738(02)00113-5) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Cowgill LW, Eleazer CD, Auerbach BM, Temple DH, Okazaki K. 2012. Developmental variation in ecogeographic body proportions. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 148, 557–570. ( 10.1002/ajpa.22072) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Cowgill LW, Eleazer CD, Auerbach BM, Temple DH, Okazaki K. 2012. Developmental variation in ecogeographic body proportions. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 148, 557–570. ( 10.1002/ajpa.22072) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Holliday TW, Hilton CE. 2010. Body proportions of circumpolar peoples as evidenced from skeletal data: Ipiutak and Tigara (Point Hope) versus Kodiak Island Inuit. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 142, 287–302. ( 10.1002/ajpa.21226) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Ruff C. 1994. Morphological adaptation to climate in modern and fossil hominids. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 37, 65–107. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330370605) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Weaver TD, Hublin JJ. 2009. Neandertal birth canal shape and the evolution of human childbirth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8151–8156. ( 10.1073/pnas.0812554106) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Prasad M, Al-Taher H. 2002. Maternal height and labour outcome. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 22, 513–515. ( 10.1080/0144361021000003654) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22, 513–515. ( 10.1080/0144361021000003654) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Fischer B, Mitteroecker P. 2015. Covariation between human pelvis shape, stature, and head size alleviates the obstetric dilemma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 5655–5660. ( 10.1073/pnas.1420325112) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Kurki HK. 2007. Protection of obstetric dimensions in a small-bodied human sample. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 133, 1152–1165. ( 10.1002/ajpa.20636) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Betti L, Balloux F, Hanihara T, Manica A. 2009. Ancient demography, not climate, explains within-population phenotypic diversity in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 809–814. ( 10.1098/rspb.2008.1563) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Betti L, Balloux F, Hanihara T, Manica A. 2010. The relative role of drift and selection in shaping the human skull. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 141, 76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Betti L, von Cramon-Taubadel N, Manica A, Lycett SJ. 2013. Global geometric morphometric analyses of the human pelvis reveal substantial neutral population history effects, even across sexes. PLoS ONE 8, e55909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Betti L, von Cramon-Taubadel N, Manica A, Lycett SJ. 2013. Global geometric morphometric analyses of the human pelvis reveal substantial neutral population history effects, even across sexes. PLoS ONE 8, e55909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Harvati K, Weaver TD. 2006. Human cranial anatomy and the differential preservation of population history and climate signatures. Anat. Rec. A 288A, 1225–1233. ( 10.1002/ar.a.20395) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Roseman CC. 2004. Detecting interregionally diversifying natural selection on modern human cranial form by using matched molecular and morphometric data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 12 824–12 829. ( 10.1073/pnas.0402637101) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Betti L. 2017. Human variation in pelvic shape and the effects of climate and past population history. Anat. Rec. 300, 687–697. ( 10.1002/ar.23542) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Betti L, von Cramon-Taubadel N, Manica A, Lycett SJ. 2014. The interaction of neutral evolutionary processes with climatically-driven adaptive changes in the 3D shape of the human os coxae. J. Hum. Evol. 73, 64–74. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.02.021) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2014. The interaction of neutral evolutionary processes with climatically-driven adaptive changes in the 3D shape of the human os coxae. J. Hum. Evol. 73, 64–74. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.02.021) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Phenice TW. 1969. A newly developed visual method of sexing the os pubis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 30, 297–301. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330300214) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Sutherland LD, Suchey JM. 1991. Use of the ventral arc in pubic sex determination. J. Forensic Sci. 36, 501–511. ( 10.1520/JFS13051J) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. McFadden C, Oxenham MF. 2016. Revisiting the Phenice technique sex classification results reported by MacLaughlin and Bruce (1990). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 159, 182–183. ( 10.1002/ajpa.22839) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Ubelaker D, Volk C. 2002. A test of the Phenice method for the estimation of sex. J. Forensic Sci. 47, 19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Ruff C. 2010. Body size and body shape in early hominins - implications of the Gona pelvis. J. Hum. Evol. 58, 166–178. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.10.003) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Ruff C. 2010. Body size and body shape in early hominins - implications of the Gona pelvis. J. Hum. Evol. 58, 166–178. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.10.003) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Auerbach BM, Ruff CB. 2004. Human body mass estimation: a comparison of ‘morphometric’ and ‘mechanical’ methods. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 125, 331–342. ( 10.1002/ajpa.20032) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. McHenry HM. 1992. Body size and proportions in early hominids. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 87, 407–431. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330870404) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Grine FE, Jungers WL, Tobias PV, Pearson OM. 1995. Fossil Homo femur from Berg Aukas, northern Namibia. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 97, 151–185. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330970207) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Ruff CB, Scott WW, Liu AYC. 1991. Articular and diaphyseal remodeling of the proximal femur with changes in body mass in adults. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 86, 397–413. ( 10.1002/ajpa. 1330860306) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1330860306) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Manica A, Prugnolle F, Balloux F. 2005. Geography is a better determinant of human genetic differentiation than ethnicity. Hum. Genet. 118, 366–371. ( 10.1007/s00439-005-0039-3) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. 2005. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978. ( 10.1002/joc.1276) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Lazaridis I, et al. 2014. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature 513, 409–413. ( 10.1038/nature13673) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Font-Porterias N, Solé-Morata N, Serra-Vidal G, Bekada A, Fadhlaoui-Zid K, Zalloua P, Calafell F, Comas D. 2018. The genetic landscape of Mediterranean North African populations through complete mtDNA sequences. Ann. Hum. Biol. 45, 98–104. ( 10. 1080/03014460.2017.1413133) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1080/03014460.2017.1413133) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Henn BM, et al. 2012. Genomic ancestry of North Africans supports back-to-Africa migrations. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002397 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002397) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Auerbach BM, Ruff CB. 2006. Limb bone bilateral asymmetry: variability and commonality among modern humans. J. Hum. Evol. 50, 203–218. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.09.004) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Pagani L, et al. 2016. Genomic analyses inform on migration events during the peopling of Eurasia. Nature 538, 238–242. ( 10.1038/nature19792) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Prugnolle F, Manica A, Balloux F. 2005. Geography predicts neutral genetic diversity of human populations. Curr. Biol. 15, R159–R160. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.038) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Li H, Durbin R. 2011. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature 475, 493–496. ( 10.1038/nature10231) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Nature 475, 493–496. ( 10.1038/nature10231) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Manica A, Amos W, Balloux F, Hanihara T. 2007. The effect of ancient population bottlenecks on human phenotypic variation. Nature 448, 346–348. ( 10.1038/nature05951) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Relethford JH, Blangero J. 1990. Detection of differential gene flow from patterns of quantitative variation. Hum. Biol. 62, 5–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Relethford JH, Crawford MH, Blangero J. 1997. Genetic drift and gene flow in post-famine Ireland. Hum. Biol. 69, 443–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Cheverud JM. 1988. A comparison of genetic and phenotypic correlations. Evolution 42, 958–968. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1988.tb02514.x) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Purcell S, et al. 2007. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575. ( 10. 1086/519795) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1086/519795) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. 2010. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 564–567. ( 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. R Core Team. 2017. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

61. Ruff C. 2017. Mechanical constraints on the hominin pelvis and the ‘obstetrical dilemma’. Anat. Rec. 300, 946–955. ( 10.1002/ar.23539) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Grabowski MW. 2013. Hominin obstetrics and the evolution of constraints. Evol. Biol. 40, 57–75. ( 10.1007/s11692-012-9174-7) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Grabowski MW, Polk JD, Roseman CC. 2011. Divergent patterns of integration and reduced constraint in the human hip and the origins of bipedalism. Evolution 65, 1336–1356. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01226.x) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01226.x) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Abou Zahr C, Wardlaw T. 2004. Maternal mortality in 2000: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

65. Wells JCK. 2017. The new ‘obstetrical dilemma’: stunting, obesity and the risk of obstructed labour. Anat. Rec. 300, 716–731. ( 10.1002/ar.23540) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. Noback ML, Harvati K, Spoor F. 2011. Climate-related variation of the human nasal cavity. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 145, 599–614. ( 10.1002/ajpa.21523) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Tilkens MJ, Wall-Scheffler C, Weaver TD, Steudel-Numbers K. 2007. The effects of body proportions on thermoregulation: an experimental assessment of Allen's rule. J. Hum. Evol. 53, 286–291. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.04.005) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Holliday TW. 1997. Body proportions in Late Pleistocene Europe and modern human origins. J. Hum. Evol. 32, 423–447. ( 10.1006/jhev.1996.0111) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Hum. Evol. 32, 423–447. ( 10.1006/jhev.1996.0111) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. Katzmarzyk PT, Leonard WR. 1998. Climatic influences on human body size and proportions: ecological adaptations and secular trends. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 106, 483–503. ( 10.1002/(sici)1096-8644(199808)106:4%3C483::aid-ajpa4%3E3.0.co;2-k) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Nielsen R, Akey JM, Jakobsson M, Pritchard JK, Tishkoff S, Willerslev E. 2017. Tracing the peopling of the world through genomics. Nature 541, 302–310. ( 10.1038/nature21347) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. Schiffels S, Durbin R. 2014. Inferring human population size and separation history from multiple genome sequences. Nat. Genet. 46, 919–925. ( 10.1038/ng.3015) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. von Cramon-Taubadel N, Lycett SJ. 2008. Brief communication: human cranial variation fits iterative founder effect model with African origin. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 136, 108–113. ( 10.1002/ajpa.20775) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 136, 108–113. ( 10.1002/ajpa.20775) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

73. Leary S, et al. 2006. Geographical variation in relationships between parental body size and offspring phenotype at birth. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 85, 1066–1079. ( 10.1080/00016340600697306) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Giroux CL, Wescott DJ. 2008. Stature estimation based on dimensions of the bony pelvis and proximal femur. J. Forensic Sci. 53, 65–68. ( 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00598.x) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Berge C, Goularas D. 2010. A new reconstruction of Sts 14 pelvis (Australopithecus africanus) from computed tomography and three-dimensional modeling techniques. J. Hum. Evol. 58, 262–272. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.11.006) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

76. Kibii JM, Churchill SE, Schmid P, Carlson KJ, Reed ND, de Ruiter DJ, Berger LR. 2011. A partial pelvis of Australopithecus sediba. Science 333, 1407–1411. ( 10.1126/science.1202521) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Science 333, 1407–1411. ( 10.1126/science.1202521) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Marchal F. 2000. A new morphometric analysis of the hominid pelvic bone. J. Hum. Evol. 38, 347–365. ( 10.1006/jhev.1999.0360) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

78. Arsuaga J-L, Lorenzo C, Carretero J-M, Gracia A, Martinez I, Garcia N, Bermudez de Castro J-M, Carbonell E. 1999. A complete human pelvis from the Middle Pleistocene of Spain. Nature 399, 255–258. ( 10.1038/20430) [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

79. Bonmatí A, Gómez-Olivencia A, Arsuaga J-L, Carretero JM, Gracia A, Martínez I, Lorenzo C, Bérmudez de Castro JM, Carbonell E. 2010. Middle Pleistocene lower back and pelvis from an aged human individual from the Sima de los Huesos site, Spain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 18 386–18 391. ( 10.1073/pnas.1012131107) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

80. Tague RG, Lovejoy CO. 1986. The obstetric pelvis of A.L. 288-1 (Lucy). J. Hum. Evol. 15, 237–255. ( 10.1016/S0047-2484(86)80052-5) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Evol. 15, 237–255. ( 10.1016/S0047-2484(86)80052-5) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

81. Betti L, Manica A. 2018. Data from: Human variation in the shape of the birth canal is significant and geographically structured Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.1gk3014) [CrossRef]

The vagina after childbirth - why it stretches, how it changes and recovers

After childbirth, your body may look and feel different ...

After childbirth, everything changes quickly. Your family has grown - now you have a child who needs to be loved and raised, who needs to be taken care of. You can experience joy, surprise, admiration and fear - all at the same time. In addition to the biggest change (in front of you is a completely new person who can’t even hold his head), there are also those that concern you yourself.

Becoming a mother, you face changes - internal and external, physical and psychological. Your body is no longer the same as it was before pregnancy, and that's okay! The vagina also changes after childbirth - this is a completely natural part of the process of bearing a child and childbirth. You may get a few new stretch marks, and your breasts may lose their usual shape. Let's find out more about how the intimate area (vagina, vulva, and bikini area) can change after childbirth, so you know what to expect.

You may get a few new stretch marks, and your breasts may lose their usual shape. Let's find out more about how the intimate area (vagina, vulva, and bikini area) can change after childbirth, so you know what to expect.

So, what changes happen to the bikini area and vagina after childbirth?

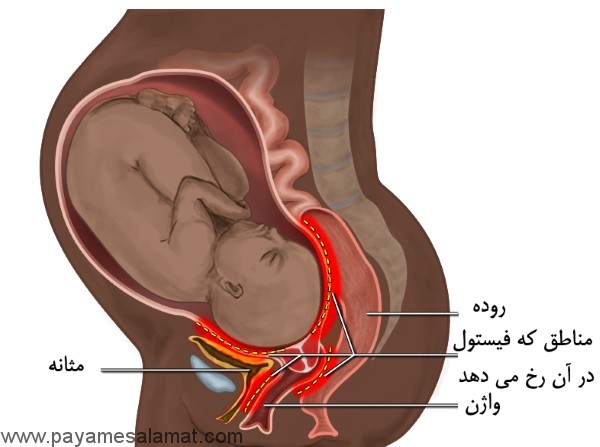

The intimate area, and especially the vagina, changes after childbirth, and this is natural. In order for the baby to pass through the birth canal, the entrance to the vagina must stretch. Its walls move apart and expand, almost like an umbrella. Sometimes the perineum — the area between the entrance to the vagina and the anus — is torn, or the doctor cuts it open to allow the baby to come out. This is called an episiotomy. The very thought of an episiotomy can be daunting, but be aware that you will be asked for consent prior to surgery, offered anesthesia (usually a local anesthetic to numb the area), and then sutured [1].

9 out of 10 women who give birth vaginally for the first time have some kind of tear, incision or episiotomy [2], so this is a common occurrence that most women in labor experience. Although the thought of such traumas can be scary, talking with those who have gone through it will help you reassure yourself that everything will be fine. You can also discuss this with your doctor so you know exactly what to expect and how to deal with it.

Although the thought of such traumas can be scary, talking with those who have gone through it will help you reassure yourself that everything will be fine. You can also discuss this with your doctor so you know exactly what to expect and how to deal with it.

You may feel like your vagina has become wider after childbirth

After the baby has passed through the vagina, it may seem wider than before. It may also feel like the vagina is looser, softer, and “opener” [3]. Also, the vagina after childbirth can be traumatized and swollen, but this will most likely pass in a few days.

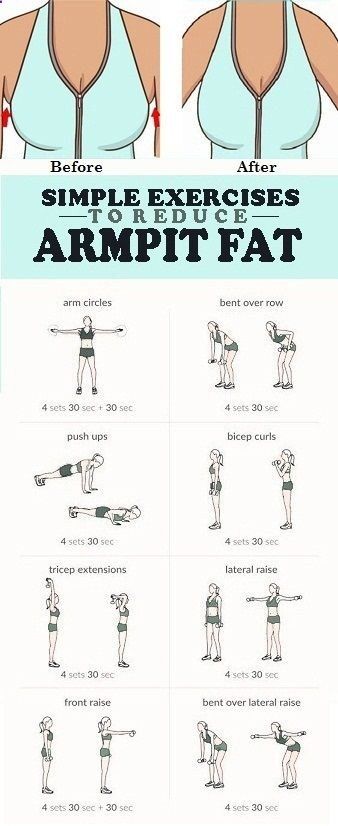

And although the vagina is unlikely to be the same as before, this is not surprising, and therefore nothing to worry about. Pelvic floor exercises will help tighten the muscles surrounding the vagina in no time! They can be performed without interruption from everyday activities: in line, while watching TV, when the child is sleeping, driving or on the bus while going on business. It is better to start doing such exercises during pregnancy.

It is better to start doing such exercises during pregnancy.

Pelvic floor exercises are also a great way to reduce urinary incontinence, which many women experience after childbirth. .

You may be worried about vaginal dryness after childbirth

After childbirth, the level of the hormone estrogen in the body decreases compared to what it was during pregnancy. This is why you feel dryness in the vagina after childbirth. If you are breastfeeding, your estrogen levels will be lower than if you are formula feeding.

If vaginal dryness after childbirth bothers you, especially after returning to a regular sex life, use a lubricant and see how much more comfortable you feel! Of course, often sex is far from the main thing that worries after the birth of a child; during this period, reduced libido is completely normal [4]! Talk to your partner - together you will work through your insecurities and figure out how to make sex as comfortable as possible for you when you are ready for it. If dryness continues to bother you or you experience pain, see your doctor for advice.

If dryness continues to bother you or you experience pain, see your doctor for advice.

Vulva pain

Your vulva has been through a lot, especially if your perineum was stitched up after a tear or an episiotomy during childbirth. You may be experiencing pain, but it will likely go away within 6-12 weeks after giving birth. Painkillers can be used, but check with your doctor first if you're breastfeeding. Be patient a little: your condition will improve every day, and, in the end, the pain will be left behind.

While the body is recovering, it is important to maintain intimate hygiene by controlling postpartum discharge. Change your pads frequently, wash your hands before changing them, and bathe or shower regularly. After a while everything should be back to normal.

It is important that a new mother takes care of herself, both physically and mentally.

Ask your partner or loved ones for help to be able to take some time for yourself, even when everything is upside down: turn on pleasant music, light a few candles and relax in the bath.

What does the belly and body look like after childbirth?

Not only the intimate area (vagina, vulva and bikini area) changes after childbirth. Your whole body is being rebuilt: first it was growing life, and now it is adapting to nourish it. Here are a couple of completely natural changes that you can see in the mirror:

What your belly looks like after giving birth This is because the muscles and skin have stretched.

Even if you think you need to get back in shape as soon as possible, it's important to remember that not having a flat abs is completely normal. You've been busy carrying the little man and taking care of him, thank you! Eat right, exercise when you are ready, and you will soon feel healthy and strong, and your stomach will gradually decrease in size. It's not a race, and there's no need to compare yourself to other new moms or Instagram bloggers. Move at your own pace and everything will work out when the time is right.

Stretch marks after pregnancy

Stretch marks appear when the skin is stretched and torn in places. They can be pink, red, brown, black, silver, or even purple depending on skin type, and appear on the abdomen, upper thighs, and chest. This happens to 8 out of 10 pregnant women [5], so you are not alone. Over time, they will become paler, not as noticeable. Think of stretch marks as a great reminder of how strong you are.

Your body is capable of many things - it can change, grow and regenerate to give new life. At first, after childbirth, it will look a little strange, but this is not surprising. Be proud of what you've been through, take care of yourself, take the time to take care of yourself, and don't neglect your health and well-being. Even when your sweet little one is screaming, remember that you can handle everything, and even if everything is falling apart, your partner, friends and family will always come to the rescue.

If you want to know more about what can happen after childbirth, read our articles on postpartum discharge and when to expect your first period after pregnancy.

Medical disclaimer

The medical information contained in this article is for reference only and should not be used for any diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. Consult a doctor about a specific disease

Links:

note-1 [1] https://www.nct.org.uk/labour-birth/you-after-birth/episiotomy-during-childbirth

note-2 [2] https:// www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/tears/tears-childbirth/

note-3 [3] https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/sexual-health/vagina-changes- after-childbirth/

note-4 [4] https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/loss-of-libido/

note-5 [5] https://www.nhs. uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/stretch-marks-pregnant/

What will help in childbirth - articles from the specialists of the clinic "Mother and Child"

Vovk Lyudmila Anatolyevna

Reproductologist, Obstetrician-gynecologist

Lapino-1 Clinical Hospital "Mother and Child"

We walk and dance

If earlier in the maternity hospital, with the onset of labor, a woman was put to bed, now, on the contrary, obstetricians recommend that the expectant mother move . For example, you can just walk: the rhythm of steps soothes, and gravity helps the neck to open faster. You need to walk as fast as it is convenient, without sprinting up the stairs, it’s better to just “cut circles” along the corridor or ward, from time to time (during the aggravation of the fight) resting on something. The gait does not matter - you can roll over like a duck, rotate your hips, walk with your legs wide apart. It is worth trying and dancing, even if you think that you do not know how. For example, you can swing your hips back and forth, describe circles and figure eights with your fifth point, sway in a knee-elbow position. The main thing is to move smoothly and slowly, without sudden movements.

For example, you can just walk: the rhythm of steps soothes, and gravity helps the neck to open faster. You need to walk as fast as it is convenient, without sprinting up the stairs, it’s better to just “cut circles” along the corridor or ward, from time to time (during the aggravation of the fight) resting on something. The gait does not matter - you can roll over like a duck, rotate your hips, walk with your legs wide apart. It is worth trying and dancing, even if you think that you do not know how. For example, you can swing your hips back and forth, describe circles and figure eights with your fifth point, sway in a knee-elbow position. The main thing is to move smoothly and slowly, without sudden movements.

Showering and bathing

For many people, water is a great way to relieve fatigue and tension, and it also helps with painful contractions. You can just stand in the shower, or you can lie down in the bath. Warm water will warm the muscles of the back and abdomen, they will relax, and the birth canal will relax - as a result, the pain may decrease. Well, if it does not decrease, then in any case, the water will relieve stress and at least for a while distract from the pain. So if there is a shower or jacuzzi bath in the delivery room, do not be shy and try this method of pain relief for contractions. The only thing is that the water should not be too hot, even if it seems that heat helps to better endure contractions.

Well, if it does not decrease, then in any case, the water will relieve stress and at least for a while distract from the pain. So if there is a shower or jacuzzi bath in the delivery room, do not be shy and try this method of pain relief for contractions. The only thing is that the water should not be too hot, even if it seems that heat helps to better endure contractions.

Swinging on the ball

Until recently, fitball (rubber inflatable ball) in the rodblock was something outlandish, and today is found in many maternity hospitals. And if you find a fitball in your rodblock, be sure to use it. You can sit on the ball astride and swing, rotate the pelvis, spring, roll from side to side. You can also kneel down, lean on the ball with your hands and chest and sway back and forth. All these movements on the ball will relax the muscles, increase the mobility of the pelvic bones, improve the opening of the neck, and reduce the pain of contractions. And while the woman is sitting on the ball, her partner (usually her husband) can massage her neck area for additional relaxation.

And while the woman is sitting on the ball, her partner (usually her husband) can massage her neck area for additional relaxation.

For comfort, the ball should be soft, slightly deflated, and large, with a diameter of at least 75 cm.

Hanging on a rope or wall bar

When the contractions become very strong and painful, you can take poses in which the stomach is, as it were, in a “suspended” state. Some advanced maternity hospitals have wall bars and ropes attached to the ceiling for this. During contraction, you can hang on them, as a result, the weight of the uterus will put less pressure on large blood vessels, and this will improve uteroplacental blood flow. In addition, in the “suspended” position, the load from the spine will be removed, which will also reduce pain.

Do not hang on a rope or a wall only if there is a desire to push, and the cervix has not yet opened and the efforts must be restrained.

Lying comfortably

If a woman in childbirth wants not to move, but, on the contrary, to lie down, then, of course, she can lie down. In modern maternity hospitals, instead of traditional ones, there are transforming beds: you can change their height, lower or raise the headboard or foot end, adjust the tilt level, push or push some part of the bed. There are also handrails in transforming beds (to use them to rest or even hang on them), and leg supports, and retractable pillows, and special backs - in general, everything in order to fit the bed under you and take it with it comfortable position. Moreover, this can be done without any physical effort - using the remote control.

In modern maternity hospitals, instead of traditional ones, there are transforming beds: you can change their height, lower or raise the headboard or foot end, adjust the tilt level, push or push some part of the bed. There are also handrails in transforming beds (to use them to rest or even hang on them), and leg supports, and retractable pillows, and special backs - in general, everything in order to fit the bed under you and take it with it comfortable position. Moreover, this can be done without any physical effort - using the remote control.

We use everything we have

In any roadblock, even if it is minimally equipped, you can still find something useful. For example, if during a fight you want to take a position with a support, you can lean forward and rest against something that turns up under your arm - a table, a headboard, a window sill. The main thing is that the support must be very stable. You can also get on all fours in the “cat pose” and focus on your hands, and to make it more convenient, put a pillow and a folded blanket under your chest.