Babies passing away

What is a neonatal death?

What is a neonatal death? | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content4-minute read

Listen

A neonatal death is when a baby dies within the first 4 weeks after they are born. Dealing with a neonatal death can be very difficult for the whole family, but there is help and support available.

What is a neonatal death?

A neonatal death (also called a newborn death) is when a baby dies during the first 28 days of life. Most neonatal deaths happen in the first week after birth.

Neonatal death is different from stillbirth. A stillbirth is when the baby dies at any time between 20 weeks of pregnancy and the due date of birth.

Globally around 2.4 million children die in the first 28 days after birth. This is around half of all child deaths under the age of 5.

Neonatal death is rare in Australia, and rates are falling — there are about 700 neonatal deaths a year in Australia.

What are the causes of a neonatal death?

It’s not always known why a baby dies. However, the risk of neonatal death may be greater if a baby is born prematurely, is low birthweight, or has birth defects.

Prematurity and low birthweight cause about 1 in 4 neonatal deaths. Premature babies can develop life-threatening complications such as breathing problems, bleeding on the brain, infections and problems in their intestines (necrotising enterocolitis).

Low birthweight — if the baby weighs less than 2.5kg at birth — can also cause serious health problems such as difficulty breathing and feeding.

The most common birth defects that cause neonatal death include heart defects, lung defects, genetic conditions and brain conditions such as neural tube defect or anencephaly.

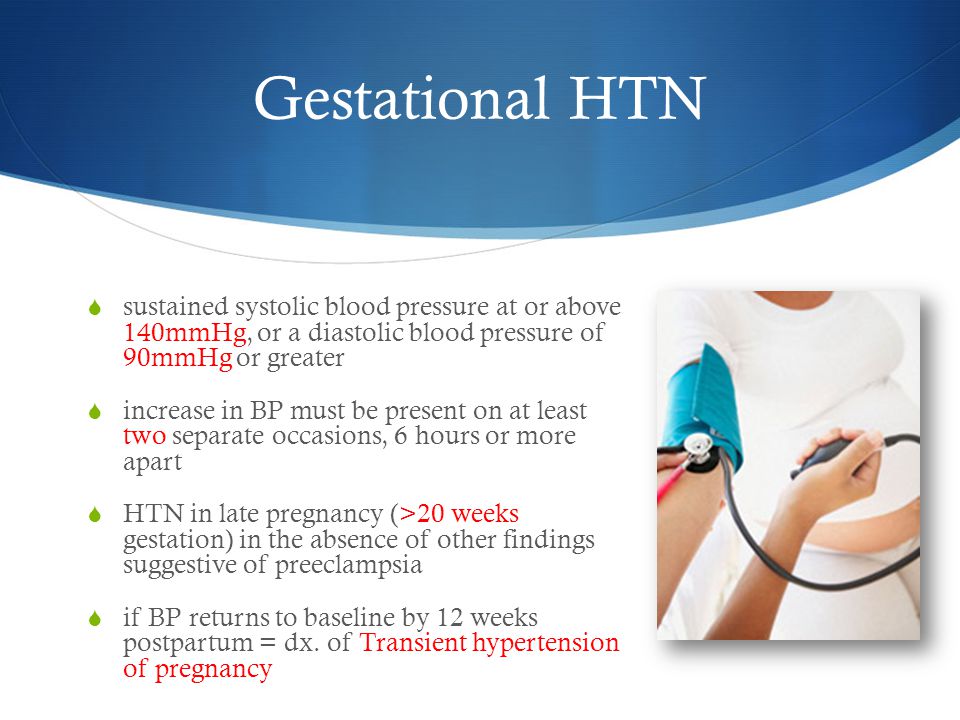

Sometimes a neonatal death may be caused by problems during the pregnancy, such as pre-eclampsia, problems with the placenta, or infections. It can also be caused by complications during the labour — for example, if the baby didn’t get enough oxygen.

It can also be caused by complications during the labour — for example, if the baby didn’t get enough oxygen.

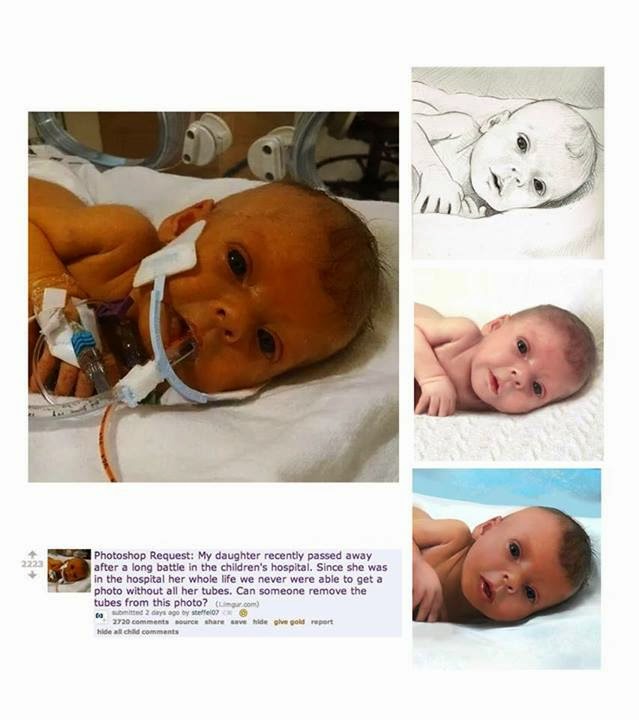

What happens after a neonatal death?

If your baby dies, you might want to spend some time with them. You should take as long as you like. Some parents create memories of the baby by taking photos, handprints and footprints.

When you are ready to say goodbye, the hospital or a funeral director will take your baby to a funeral home. There will then be a burial or cremation.

By law, you must register both the birth and the death with Births, Deaths and Marriages in your state or territory.

In Australia, not all neonatal deaths are investigated by conducting an autopsy, also known as a post mortem examination. An autopsy is an examination to try to work out why the baby has died.

An autopsy cannot be done without the parents’ consent and it is up to you whether to agree to an autopsy after a neonatal death. The only time when an autopsy may be carried out without consent is if the case is referred to a coroner. This might happen if the death occurred in suspicious circumstances or if it was something to do with the health care the baby received.

This might happen if the death occurred in suspicious circumstances or if it was something to do with the health care the baby received.

An autopsy is done by a trained pathologist. If you agree to an autopsy, you can decide how detailed you would like it to be — whether it involves just examining the baby or removing organs to test why the death has happened.

Sometimes no cause of death can be found, even after an autopsy. It’s a good idea to discuss the benefits and downsides of an autopsy with a doctor, midwife or social worker. They will guide you through what needs to be done and will answer any questions you might have.

Learn more here about what happens after a neonatal death and what changes might occur to your body.

Where to find help

The death of a newborn baby can be devastating, both for the parents and for the whole family. So it’s important to get as much support as possible to help you through this difficult time.

Your doctor, midwife, maternal child health nurse or social worker will be able to guide you through what happens after the baby has died.

Sands Australia provides information and support for anyone who has experienced stillbirth or newborn death. You can speak to someone 24 hours a day on their helpline, 1300 072 637.

Red Nose Grief and Loss has information and resources. You can call their helpline 24 hours a day on 1300 308 307.

Lifeline supports anyone having a personal crisis — call 13 11 14 or chat online.

You can call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby on 1800 882 436 to talk to a maternal child health nurse.

Sources:

World Health Organization (Newborn deaths and illnesses), Raising Children Network (Neonatal death - a guide), March of Dimes (Neonatal death), The Royal Women’s Hospital Melbourne (Learning why a baby has died), Queensland Courts (Reportable deaths), Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Stillbirth and neonatal deaths in Australia), Sands (Stillborn and newborn death), myDr (Low-birth-weight babies)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: April 2021

Back To Top

Related pages

- Your body after stillbirth or neonatal death

- Dealing with a neonatal death

- Birth trauma (emotional)

Need more information?

Baby and Infant Death

Baby and Infant Death A neonatal death is when a baby is born alive but dies within the first 28 days of life

Read more on Gidget Foundation Australia website

Death of a baby - Better Health Channel

Miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death is a shattering event for those expecting a baby, and for their families. Grief, relationship stresses and anxiety about subsequent pregnancies are common in these circumstances.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

When Your Baby is Stillborn or Dies Soon After Birth | Guiding Light - Red Nose Grief and Loss

Read more on Red Nose website

Breast care for breastfeeding mothers after the death of a child | Sydney Children's Hospitals Network

Time after the death of your infant can be physically and emotionally exhausting

Read more on Sydney Children's Hospitals Network website

Smoking | Red Nose Australia

Read more on Red Nose website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) (for Parents)

What Is SIDS?

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the sudden and unexplained death of a baby younger than 1 year old. Most SIDS deaths are associated with sleep, which is why it's sometimes still called "crib death."

Can SIDS Be Prevented?

A lack of answers is part of what makes SIDS so frightening. SIDS is the leading cause of death among infants 1 month to 1 year old, and remains unpredictable despite years of research.

Even so, the risk of SIDS can be greatly reduced. Most important: Babies younger than 1 year old should be placed on their backs to sleep — never on their stomachs or on their sides. Sleeping on the stomach or side increases the risk for SIDS.

Sleeping on the stomach or side increases the risk for SIDS.

Who Is at Risk for SIDS?

Most SIDS deaths happen in babies between 1 and 4 months old, and cases rise during cold weather.

Babies might have a higher risk of SIDS if:

- their mother smoked, drank, or used drugs during pregnancy and after birth

- their mother had poor prenatal care

- they were born prematurely or at a low birth weight

- there's a family history of SIDS

- their mothers were younger than 20 when they gave birth

- they are around tobacco smoke after birth

- they get overheated

- they sleep on a soft surface

- they sleep with soft objects or loose blankets and pillows

- they sleep in a parent’s bed

Doctors diagnose most health problems based on the symptoms they cause. But SIDS is diagnosed after all other possible causes of death have been ruled out. This review helps tell true SIDS deaths from those due to accidents, abuse, and previously undiagnosed conditions, such as heart problems.

Why Is Stomach Sleeping Dangerous?

SIDS is more likely in babies placed on their stomachs to sleep than babies sleeping on their backs. Babies also should not be placed on their sides to sleep. A baby can easily roll from a side position onto the belly during sleep.

Some researchers believe that stomach sleeping may block the airway. Stomach sleeping can increase "rebreathing" — when babies breathe in their own exhaled air — particularly if the baby is sleeping on a soft mattress or with bedding, stuffed toys, or a pillow near their face. As the baby rebreathes exhaled air, the oxygen level in the body drops and the level of carbon dioxide rises.

Infants who die from SIDS may have a problem with the part of the brain that helps control breathing and waking during sleep. If a baby is breathing stale air and not getting enough oxygen, the brain usually triggers the baby to wake up and cry to get more oxygen. If the brain is not picking up this signal, oxygen levels will fall and carbon dioxide levels will rise.

In response, the AAP's (American Academy of Pediatrics) "Back to Sleep" campaign recommended that all healthy infants younger than 1 year old be placed on their backs to sleep.

Babies should be placed on their backs until 12 months of age. Older infants may not stay on their backs all night long, and that's OK. Once babies consistently roll over from front to back and back to front, it's fine for them to be in the sleep position they choose. Do not use positioners, wedges, and other devices that claim to reduce the risk of SIDS.

Common Concerns

Some parents might worry about "flat head syndrome" (positional plagiocephaly). This is when babies develop a flat spot on the back of their heads from spending too much time lying on their backs. Since the "Back to Sleep" campaign, this has become more common. But it's easily treatable by changing a baby's position in the crib and allowing for more supervised "tummy time" while babies are awake.

Some parents may worry that babies put to sleep on their backs could choke on spit-up or vomit. There's no increased risk of choking for healthy infants or most babies with gastroesophageal reflux (GER) who sleep on their backs. Doctors may recommend that babies with some types of rare airway problems sleep on their stomachs.

There's no increased risk of choking for healthy infants or most babies with gastroesophageal reflux (GER) who sleep on their backs. Doctors may recommend that babies with some types of rare airway problems sleep on their stomachs.

Parents should talk to their child's doctor if they have questions about the best sleeping position for their baby.

What Is "Safe to Sleep"?

Since the AAP's recommendation, the rate of SIDS has dropped greatly. Still, it is the leading cause of death in young infants. The Safe Sleep campaign reminds parents and caregivers to put infants to sleep on their backs and provide a safe sleep environment.

Here's how parents can help reduce the risk of SIDS and other sleep-related deaths:

- Get early and regular prenatal care.

- Place your baby on a firm, flat mattress to sleep, never on a pillow, waterbed, sheepskin, couch, chair, or other soft surface.

- Cover the mattress with a fitted sheet and no other bedding.

Keep soft objects and loose bedding out of the sleep area.

Keep soft objects and loose bedding out of the sleep area. - Do not use bumper pads in cribs. Bumper pads can be a suffocation or strangulation hazard.

- Practice room-sharing without bed-sharing. Experts recommend that infants sleep in their parents' room — but on a separate surface, like a bassinet or crib next to the bed — until the child's first birthday, or for at least 6 months, when the risk of SIDS is highest.

- Breastfeed, if possible. Exclusive breastfeeding or feeding with expressed milk is most protective, but any breastfeeding has been shown to reduce the risk of SIDS.

- Offer a pacifier to your baby at sleep time, but don’t force it. If the pacifier falls out during sleep, you don’t have to replace it. If you're breastfeeding, wait until breastfeeding is firmly established.

- To avoid overheating, dress your baby for the room temperature and don't overbundle. Don't cover your baby's head while they're sleeping. Watch for signs of overheating, such as sweating or feeling hot to the touch.

- Don't smoke during pregnancy or after birth. Infants of moms who smoked during pregnancy are more at risk for SIDS than those whose mothers were smoke-free; exposure to secondhand smoke also raises a baby's risk, and that risk is very high if a parent who smokes shares the bed with a baby.

- Do not use alcohol or drugs during pregnancy or after birth. Parents who drink or use drugs should not share a bed with their infant.

- Don’t let your baby fall asleep on a product that isn’t specifically designed for sleeping babies, such as a sitting device (like a car seat), a feeding pillow (like the Boppy pillow), or an infant lounger (like the Dock-a-Tot, Podster, and Bummzie).

- Don’t use products or devices that claim to lower the risk of SIDS, such as sleep positioners (like wedges or incliners) or monitors that can detect a baby’s heart rate and breathing pattern. No known products can actually do this.

- Don’t use weighted blankets, sleepers, or swaddles on or around your baby.

- Make sure that all sleep surfaces and products you use to help your baby sleep have been approved by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) and meet federal safety standards.

- Make sure your baby gets all recommended immunizations. Studies have shown that babies who receive their vaccines have a lower risk of SIDS.

For parents and families who have experienced a SIDS death, many groups, including First Candle, can provide grief counseling, support, and referrals.

Forensic scientist - about when and why children die

Richard Shepherd, one of the most famous forensic experts in the UK, claims that the most dangerous age for a child is the period up to a year. Why? He answers this question in The Seven Ages of Death. Journey of a Medical Examiner through Life" (published by Bombora Publishing House). And there are many different reasons, including far from the most obvious ones.

Fergusson (infant with congenital disease . - Note ed. .) died at the age of six months from a cause we have yet to establish. Nevertheless, every child, even if he lived such a short life, is an incredible achievement of nature. Long before our lives begin, the sperm and eggs of our parents are formed from progenitor cells in an amazing process called meiosis. What makes it so amazing? That sperm and eggs are not just exact copies of parental cells. As a result of meiosis, only half of their chromosomes remain in sperm and eggs so that they can, God willing, unite into a single whole. Moreover, meiosis includes an additional, rather risky process called "crossing over", during which the chromosomes in each pair exchange DNA fragments before separating. The artist, who carefully applied each color individually to the canvas, now picks up a palette and mixes them, creating completely new shades. This is how unique characteristics are set, and as a result, the DNA of female eggs differs from the DNA of other cells of the mother.

- Note ed. .) died at the age of six months from a cause we have yet to establish. Nevertheless, every child, even if he lived such a short life, is an incredible achievement of nature. Long before our lives begin, the sperm and eggs of our parents are formed from progenitor cells in an amazing process called meiosis. What makes it so amazing? That sperm and eggs are not just exact copies of parental cells. As a result of meiosis, only half of their chromosomes remain in sperm and eggs so that they can, God willing, unite into a single whole. Moreover, meiosis includes an additional, rather risky process called "crossing over", during which the chromosomes in each pair exchange DNA fragments before separating. The artist, who carefully applied each color individually to the canvas, now picks up a palette and mixes them, creating completely new shades. This is how unique characteristics are set, and as a result, the DNA of female eggs differs from the DNA of other cells of the mother. Differences between generations are set long before the final mixing of DNA, when sperm and egg finally meet.

Differences between generations are set long before the final mixing of DNA, when sperm and egg finally meet.

Only when you mix too many different colors with a brush, in addition to bright and beautiful colors, you can also get a complete daub - it is during this most important stage of meiosis that all kinds of chromosomal anomalies appear. Moreover, for women, this crossing-over, on which the future child will be so dependent, actually occurs long before the conception of the child itself. It occurs even during the intrauterine development of the expectant mother, in the very first weeks of the grandmother's pregnancy. It is hard to believe that events in a grandmother's life can have such long-term consequences for the child she is carrying - there are many debates about how much meiosis is influenced by external factors ...

But if someone says, for example, that the Chernobyl disaster of 1986 may continue to make itself felt even two generations later, it is clearly not worth rushing to reject this idea.

After the fertilization of the egg by the spermatozoon, further events in terms of metabolism and energy can be compared to a nuclear explosion. At the moment of conception, when the two halves of DNA from each of the parents unite into a single whole, a process of rapid division and development begins, truly impressive in its scale. Now we are dealing with mitosis, in which cells make exact copies of themselves, as opposed to meiosis, which produces sex cells with mixed DNA.

This staggering speed, however, is associated with the risk of errors that could end a child's life before birth.

Congenital pathologies - disorders with which a child already comes into this world - have many different causes

First of all, these are external factors. This may be a lack of amniotic fluid necessary to protect the child, as a result of which certain parts of his body are compressed and remain in a flattened state. Or the mother (perhaps even the grandmother) may have been exposed to radiation or mercury fumes, or exposed the child herself to such threats as, for example, the influence of alcohol. Another serious factor is viruses. Yes, the Spanish flu pandemic18 years claimed the lives of between 50 and 100 million people around the world, with the younger generation suffering the most. In the United States, about a third of all women, both pregnant and of childbearing age, have been infected. In the United States, long-term medical studies of children whose mothers had the flu during pregnancy showed that years later this could lead to negative consequences for their health. Thus, the children of women who had the flu in early pregnancy were more likely to develop diabetes. Influenza transferred in the first trimesters of pregnancy significantly increased the likelihood of cardiovascular diseases in children in the future, even in old age. Those who had been ill in the last months of pregnancy had children who, in old age, more often encountered kidney diseases.

Another serious factor is viruses. Yes, the Spanish flu pandemic18 years claimed the lives of between 50 and 100 million people around the world, with the younger generation suffering the most. In the United States, about a third of all women, both pregnant and of childbearing age, have been infected. In the United States, long-term medical studies of children whose mothers had the flu during pregnancy showed that years later this could lead to negative consequences for their health. Thus, the children of women who had the flu in early pregnancy were more likely to develop diabetes. Influenza transferred in the first trimesters of pregnancy significantly increased the likelihood of cardiovascular diseases in children in the future, even in old age. Those who had been ill in the last months of pregnancy had children who, in old age, more often encountered kidney diseases.

The influenza virus is supposed to have stressed the fetus

And one of the many theories is that the blood supply is switched from the vital organs to the brain of the fetus to provide additional protection. This guarantees the survival of the child, but can program certain organs to fail after fifty, sixty or more years. And since the development of various organs occurs at different stages of pregnancy, the specific consequences depend heavily on the trimester in which the mother caught the flu.

This guarantees the survival of the child, but can program certain organs to fail after fifty, sixty or more years. And since the development of various organs occurs at different stages of pregnancy, the specific consequences depend heavily on the trimester in which the mother caught the flu.

You may now be worried that a new pandemic might have similar effects. Well, perhaps COVID-19 will not affect the long-term health of children conceived and born during this period at all, most often it hits the elderly. Long-term studies will clarify everything, only now, unfortunately, I will no longer have the opportunity to familiarize myself with their results.

Illustration: shutterstock / MicroOne The second, no less devastating cause of congenital pathologies is inherited family genes. Associated diseases may not be noticeable at birth because some genes lie dormant for many years before leading to disease or death. Most appear in the first years of life, however, Huntington's chorea (A hereditary disease of the nervous system. Usually begins at the age of 35–50 years. At the very beginning, problems arise due to sudden, sharp, uncontrollable movements. In other cases, the patient, on the contrary, moves too much slowly. Speech becomes slurred, coordination of movements and all functions that require muscle control are gradually disturbed: a person begins to grimace, has difficulty chewing and swallowing. Due to rapid eye movement, sleep is disturbed. All this is combined with mental disorders), for example, can give know about yourself only forty, fifty or even sixty years later.

Usually begins at the age of 35–50 years. At the very beginning, problems arise due to sudden, sharp, uncontrollable movements. In other cases, the patient, on the contrary, moves too much slowly. Speech becomes slurred, coordination of movements and all functions that require muscle control are gradually disturbed: a person begins to grimace, has difficulty chewing and swallowing. Due to rapid eye movement, sleep is disturbed. All this is combined with mental disorders), for example, can give know about yourself only forty, fifty or even sixty years later.

Genetic errors are the third and most common cause of congenital health problems. They occur during the formation of spermatozoa (which could have been just two weeks ago) or eggs (formed much earlier, even during the intrauterine development of a woman). Or something could go wrong during the period of intense cell division after conception. Mistakes during pregnancy most often occur in the first four weeks. The organs are located so close to each other and develop so interdependently that a mistake at this stage is often fatal for the fetus. Moreover, even if a miscarriage does not occur and the fetus lasts until birth, these early mistakes can lead to severe brain or heart defects, dooming to a very short life.

The organs are located so close to each other and develop so interdependently that a mistake at this stage is often fatal for the fetus. Moreover, even if a miscarriage does not occur and the fetus lasts until birth, these early mistakes can lead to severe brain or heart defects, dooming to a very short life.

On the other hand, errors later in pregnancy can lead to congenital abnormalities that are not immediately noticeable or never detected at all. When autopsying older people, I sometimes stumbled upon a heart with a congenital defect that was not the cause of death or illness - I'm sure no one even suspected its existence.

The safe birth of a child does not at all mean that his dangerous journey has come to an end.

Those who survive childbirth are in for perhaps the most dangerous year of their entire lives. After that, the risk of death decreases sharply, and until the age of fifty-five we will not even come close to the level of danger of the first year of life. By this time, bad habits, age-related diseases, accidents begin to make themselves known - probably due to a lack of awareness of the body's capabilities declining with age, unnatural phenomena like air pollution or a spouse capable of killing, or even all the same congenital pathologies that have gone unnoticed.

By this time, bad habits, age-related diseases, accidents begin to make themselves known - probably due to a lack of awareness of the body's capabilities declining with age, unnatural phenomena like air pollution or a spouse capable of killing, or even all the same congenital pathologies that have gone unnoticed.

<…>

After this dangerous first year of life, the child's chance of dying drops by more than 95%. By the age of four, congenital pathologies, as a rule, make themselves felt, but children are less susceptible to infectious diseases. It turns out that the period from five to nine years is the safest throughout life, and from ten to fourteen it is not particularly behind it.

Illustration: shutterstock / Mary Long How do children die anyway? Of course, there is always the risk of severe infection: meningitis, sepsis and, increasingly, measles can still lead to death. According to statistics for 2018, infectious diseases accounted for 6% of childhood deaths. Accidents are responsible for about 15% of all deaths - perhaps curiosity overrides risk awareness as the child grows, but more often than not, children are simply too vulnerable pedestrians and cyclists.

Accidents are responsible for about 15% of all deaths - perhaps curiosity overrides risk awareness as the child grows, but more often than not, children are simply too vulnerable pedestrians and cyclists.

Meanwhile, cars are not the biggest killers of babies. With a huge margin, cancer is ahead of them. Since the 1960s, the prevalence of childhood cancer has steadily increased worldwide, increasing by about 11% from 2000 to 2017.

Reporting and diagnostics have certainly improved since the 1960s, but this dramatic growth cannot be explained by this alone. There is only one general agreement: the cause may well lie, at least in part, in the environment and be associated with certain aspects of modern life - for example, the spread of various chemicals or modern technologies that we mistakenly consider harmless.

The most common cancer in children is acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It is associated with the uncontrolled production of white blood cells in the bone marrow, as a result of which immature and useless white blood cells crowd out normal white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets - tiny cells involved in the blood clotting process - leading to the first and most noticeable symptoms of the disease - bruising and anemia. .

.

Leukemia is not considered a hereditary disease, although sometimes hereditary risk factors may occur

In most cases, the exact cause of the disease is simply unknown. The researchers made an interesting observation: only a few of the sick children attended a nursery in the first year of life; as a result, they were bypassed by viruses and bacteria, due to which coughs and colds constantly walk there. In infancy, they were isolated from infections.

The study suggested that exposure to infectious agents during the first years of life may have a protective function. Our immune system needs to be trained - it needs to become familiar with the main types of infectious pathogens that exist in order to cope with them faster in the future. This, in fact, is the main idea of vaccination. Evidence has emerged in favor of the fact that timely vaccination can provide children with additional protection against leukemia. The development of this type of cancer can be caused by a combination of a number of factors - genes, diet, bad luck, or some other variables that are not yet known. If you think about what has changed over the past 50 years, it can be noted that the houses have become much cleaner - maybe our immune system lacks the extra boost that the unsanitary conditions of past years provided it with?

If you think about what has changed over the past 50 years, it can be noted that the houses have become much cleaner - maybe our immune system lacks the extra boost that the unsanitary conditions of past years provided it with?

The same theory is used by some doctors to explain the exorbitant prevalence of asthma. This disease is the result of a malfunction of the immune system. More than a million children are currently being treated for it in the UK1 (about one in eleven, according to Asthma UK). It must be understood that, even if the incidence levels level off, given the growth in the population, at least three times more children now suffer from asthma than in the 1960s. Hygiene theory gives hope to asthmatic children and their parents (and anyone else who hates cleaning), but is especially encouraging to those who suffer from leukemia. According to this theory, if we change our approach to immunity, we may be able to defeat this most vicious childhood monster, and thoughtlessly refusing to vaccinate many more may doom many more to long-term chemotherapy or even early death.

Cover image: shutterstock / cosmaa

Children: reducing mortality

Children: reduction in mortality- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- 9000

- О

- П

- Р

- С

- Т

- У

- Ф

- Х

- Ц

- Ч

- Ш

- Щ

- Ъ

- Ы

- Ь

- Э

- Yu

- I

- WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Improving child survival and development

WHO/C. Gaggero

Gaggero

© A photo

","datePublished":"2020-09-08T22:00:00.0000000+00:00","image":"https://cdn.who.int/media/images/default-source/imported/ children-palliative-care-jpg.jpg?sfvrsn=a2eca396_4","publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"World Health Organization: WHO","logo":{"@type" :"ImageObject","url":"https://www.who.int/Images/SchemaOrg/schemaOrgLogo.jpg","width":250,"height":60}},"dateModified":"2020- 09-08T22:00:00.0000000+00:00","mainEntityOfPage":"https://www.who.int/ru/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/children-reducing-mortality","@context" :"http://schema.org","@type":"Article"};

Key Facts

- An estimated 5.2 million children under the age of five died globally in 2019, most from preventable and treatable causes. Of these, 1.5 million children aged 1–11 months and 1.3 million children aged 1–4 years died. Newborns (less than 28 days old) account for 2.4 million deaths.

- In addition, 500,000 older children (5–9 years) died in 2019.

- The leading causes of death in children under five years of age are complications of preterm birth, asphyxia/trauma, pneumonia, congenital malformations, diarrhea and malaria; all of these causes are preventable or treatable with simple, affordable interventions, including immunization, adequate nutrition, safe water and food supplies, and quality care from a skilled health worker when needed.

- Since 1990, one of the largest reductions in mortality (by 61%) has occurred among older children (5–9 years) due to a decrease in the incidence of infections. Injuries (including road traffic injuries and drowning) are the leading cause of death in older children.

Who is most at risk?

Children under five

Since 1990, significant progress has been made in reducing child mortality throughout the world. The global number of deaths of children under the age of five fell from 12.6 million to 1990 to 5. 2 million in 2019 Between 1990 and 2019, global under-five mortality decreased by 59%, from 93 deaths per 1,000 live births to 38. This means that if in 1990 every 11th child died under the age of five, then in 2019 - every 27th.

2 million in 2019 Between 1990 and 2019, global under-five mortality decreased by 59%, from 93 deaths per 1,000 live births to 38. This means that if in 1990 every 11th child died under the age of five, then in 2019 - every 27th.

Against the backdrop of an overall accelerated downward trend in under-five mortality, this figure varies by region and country. Sub-Saharan Africa continues to be the region with the highest under-five mortality, with one in 13 children dying to their fifth birthday; this corresponds to a 20-year lag behind the global average of 1 to 13 in 1999 In 2019, more than 80% of the 5.2 million deaths of children under five years of age occurred in two regions, sub-Saharan Africa and Central and South Asia, although they account for only 52% of the global child population under the age of five. Half of all under-five deaths in 2019 occurred in just five countries: Ethiopia, Nigeria, India, Pakistan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nigeria and India alone account for almost a third of all deaths.

At the country level, older child mortality rates ranged from 0.2 to 16.8 deaths per 1,000 children aged five years and older. Countries with higher under-five mortality rates are mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. The countries with the highest death rates among children aged five to nine are India, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan and China.

Top 10 countries with the highest under-five mortality rates, 2019(thousand cases)

| Country | Deaths of children under five years of age | Lower limit | Upper limit |

| Nigeria | 858 | 675 | 1118 |

| India | 824 | 738 | 913 |

| Pakistan | 399 | 343 | 465 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 291 | 187 | 440 |

| Ethiopia | 178 | 146 | 216 |

| China | 132 | 116 | 152 |

| Indonesia | 115 | 97 | 139 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 103 | 78 | 172 |

| Angola | 93 | 43 | 172 |

| Bangladesh | 90 | 82 | 99 |

The leading causes of death in children under five years of age worldwide are infectious diseases, including pneumonia, diarrhea and malaria, as well as prematurity, birth asphyxia and trauma, and congenital malformations. Many children's lives can be saved with basic interventions such as skilled birth attendance, postnatal care, breastfeeding and proper nutrition, vaccinations and treatment of common childhood illnesses. Children who are malnourished, especially severe acute malnutrition, are at increased risk of death from common childhood diseases such as diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria. Nutritional factors contribute to approximately 45% of deaths in children under the age of five.

Many children's lives can be saved with basic interventions such as skilled birth attendance, postnatal care, breastfeeding and proper nutrition, vaccinations and treatment of common childhood illnesses. Children who are malnourished, especially severe acute malnutrition, are at increased risk of death from common childhood diseases such as diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria. Nutritional factors contribute to approximately 45% of deaths in children under the age of five.

Trends in mortality among older children are in line with the range of risks faced by this age group, characterized by a decrease in the prevalence of causes such as infectious diseases in children and an increase in the incidence of accidents and injuries, primarily drowning and road traffic injuries. In connection with the increased mortality of older children as a result of injuries, a slightly different set of measures should be applied to this age group to improve survival rates. The focus is shifting from health sector interventions in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases in early childhood to interventions in other sectors of government in areas such as education, transport and road infrastructure, water and sanitation, and public order. To prevent premature death among older children, all these measures must be taken in combination.

To prevent premature death among older children, all these measures must be taken in combination.

Global response: Sustainable Development Goal 3.2.1

Adopted by the United Nations in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to promote healthy lifestyles and promote the well-being of all children. SDG 3.2.1 is to end preventable deaths of newborns and children under five years of age by 2030. This goal has two targets:

- reduce neonatal mortality to no more than 12 per 1,000 live births in each country; and

- Reduce under-five mortality to no more than 25 per 1,000 live births in each country.

Task 3.2.1 is closely related to task 3.1.1. to reduce the global maternal mortality rate to below 70 per 100,000 live births and target 2.2.1 to eliminate all forms of malnutrition, as malnutrition is often the cause of death for children under five years of age. These challenges are reflected in the new Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health (Global Strategy), which aims to end preventable child deaths while addressing new child health priorities. Member States need to set their own targets, develop specific strategies to reduce child mortality and monitor progress towards reducing it.

Member States need to set their own targets, develop specific strategies to reduce child mortality and monitor progress towards reducing it.

In 2019, the SDG target of reducing under-five mortality was met in 122 countries and, on current trends, an additional 20 countries will be met by 2030. However, 53 countries need to accelerate progress, as they will not reach this target by 2030 at current rates. Thirty of these countries will need to double and 23 countries will need to triple their current rates of mortality reduction. Thanks to this SDG target, the number of deaths of children under five years of age since 2019by 2030 will be reduced by 11 million. In sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia, targeted efforts are still needed to prevent 80% of these deaths.

WHO action

WHO calls on Member States to ensure universal health coverage to realize the principle of equitable access to health care, so that all children can receive basic health care without financial hardship for their families.