Down's syndrome screening results

Screening for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome

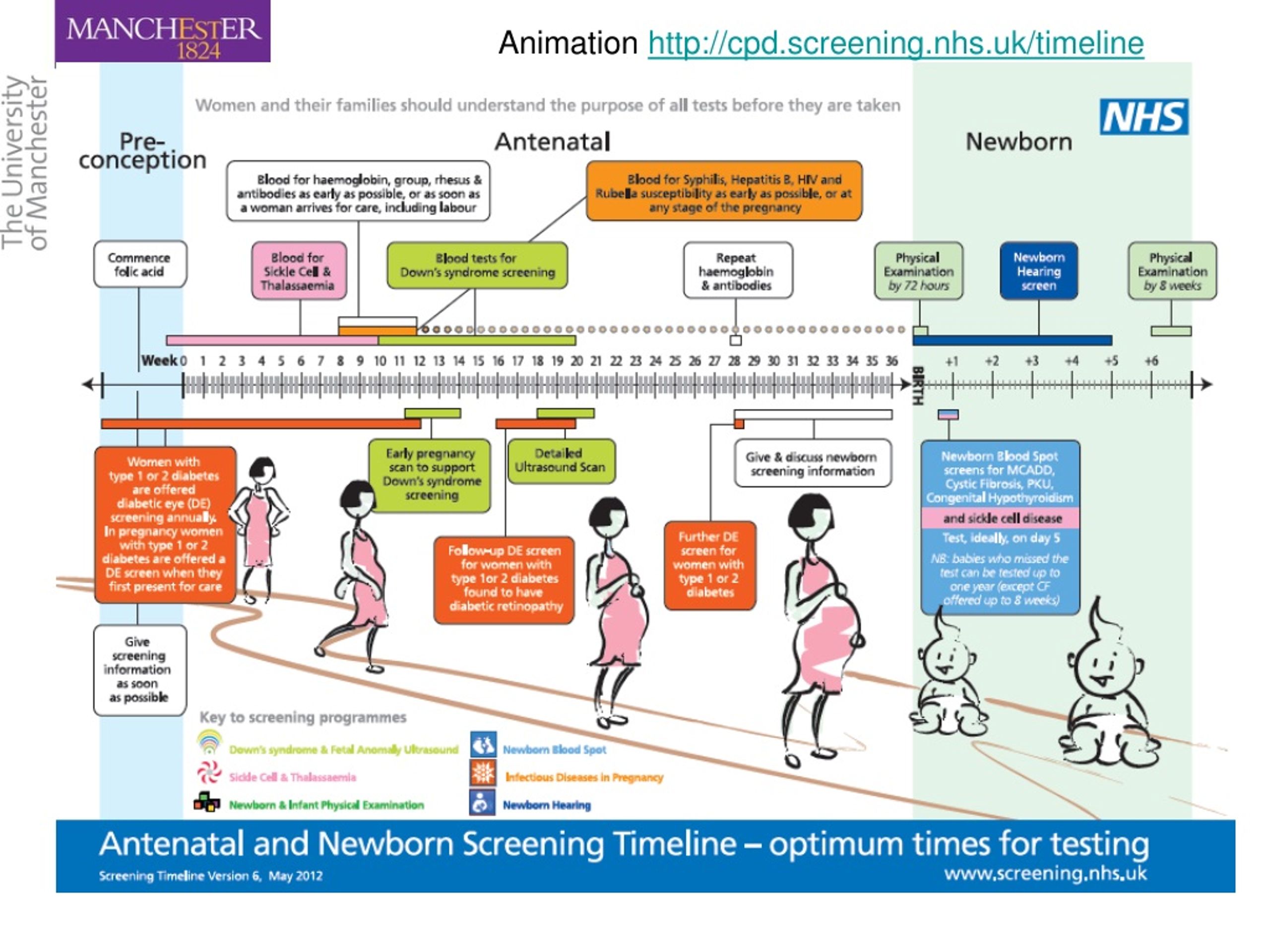

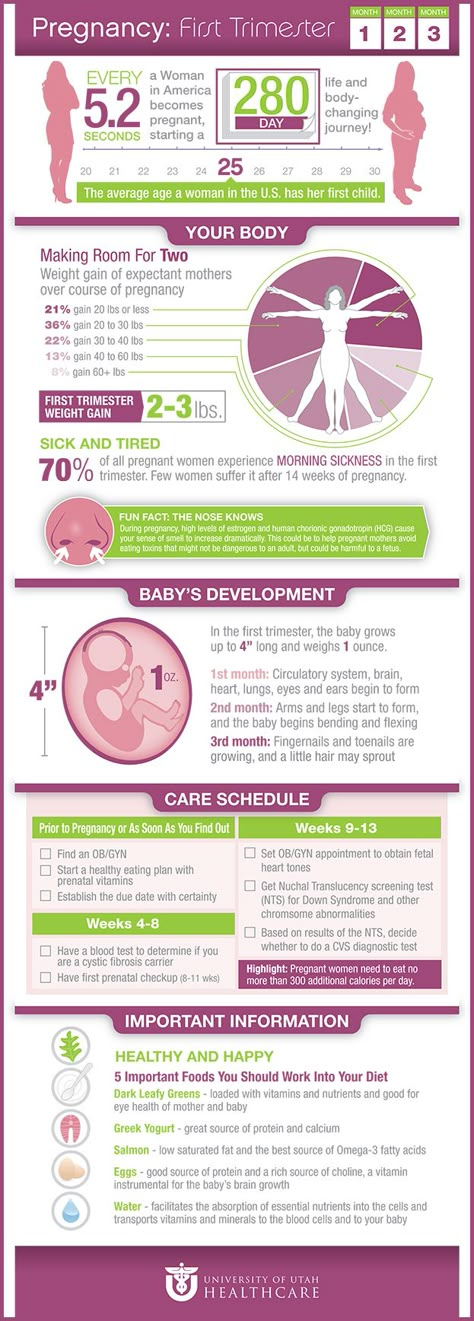

You will be offered a screening test for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome between 10 and 14 weeks of pregnancy. This is to assess your chances of having a baby with one of these conditions.

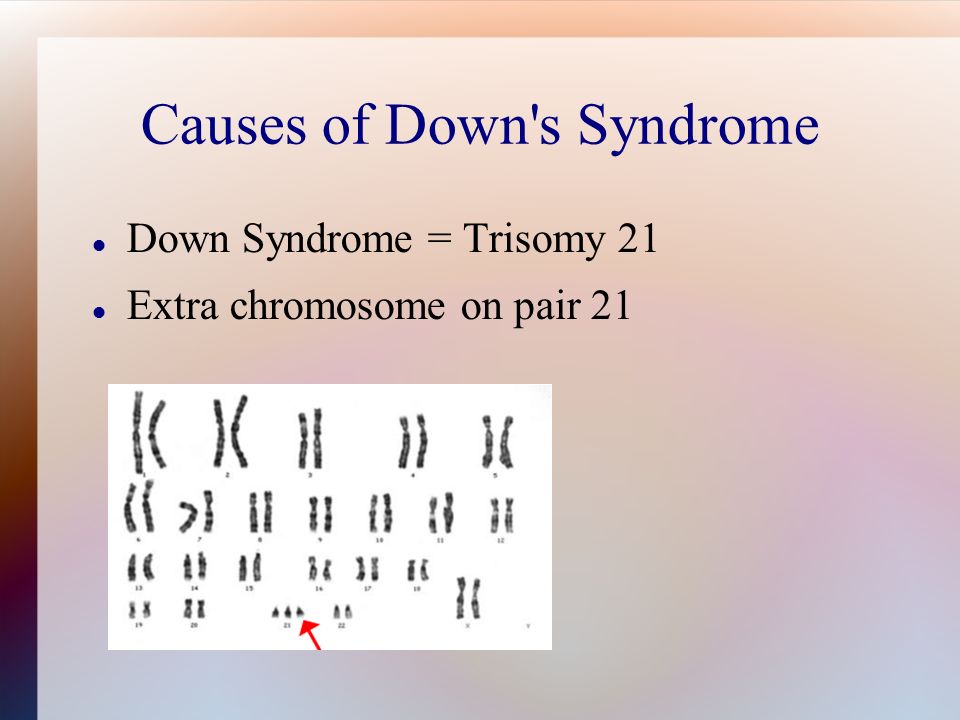

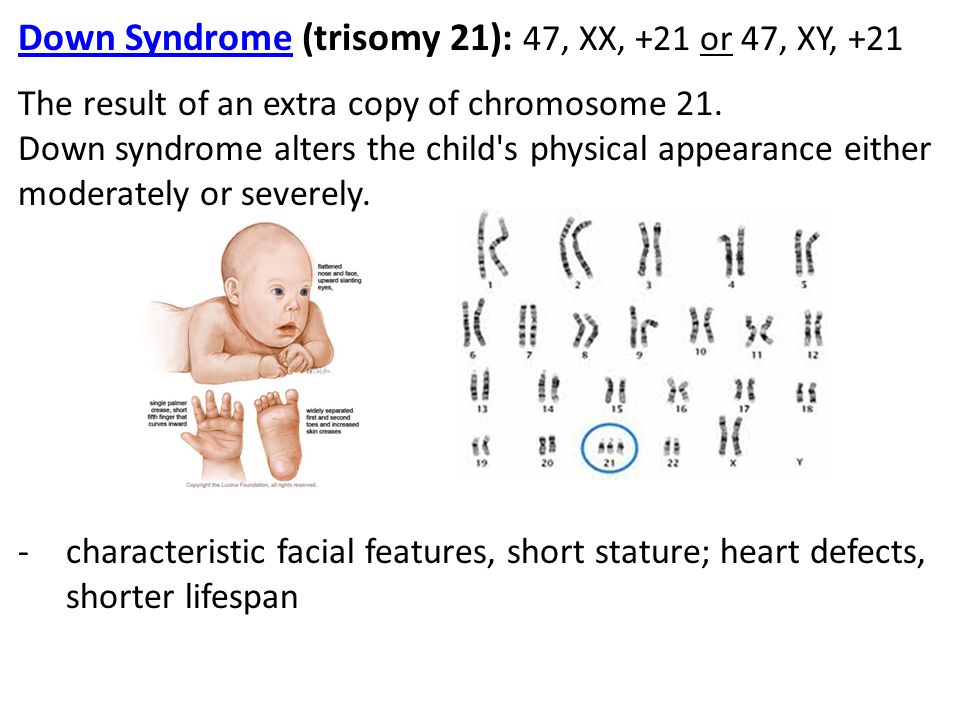

Down's syndrome is also called trisomy 21 or T21. Edwards' syndrome is also called trisomy 18 or T18, and Patau's syndrome is also called trisomy 13 or T13.

If a screening test shows that you have a higher chance of having a baby with Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome, you'll be offered further tests to find out for certain if your baby has the condition.

What are Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome?

Down's syndrome

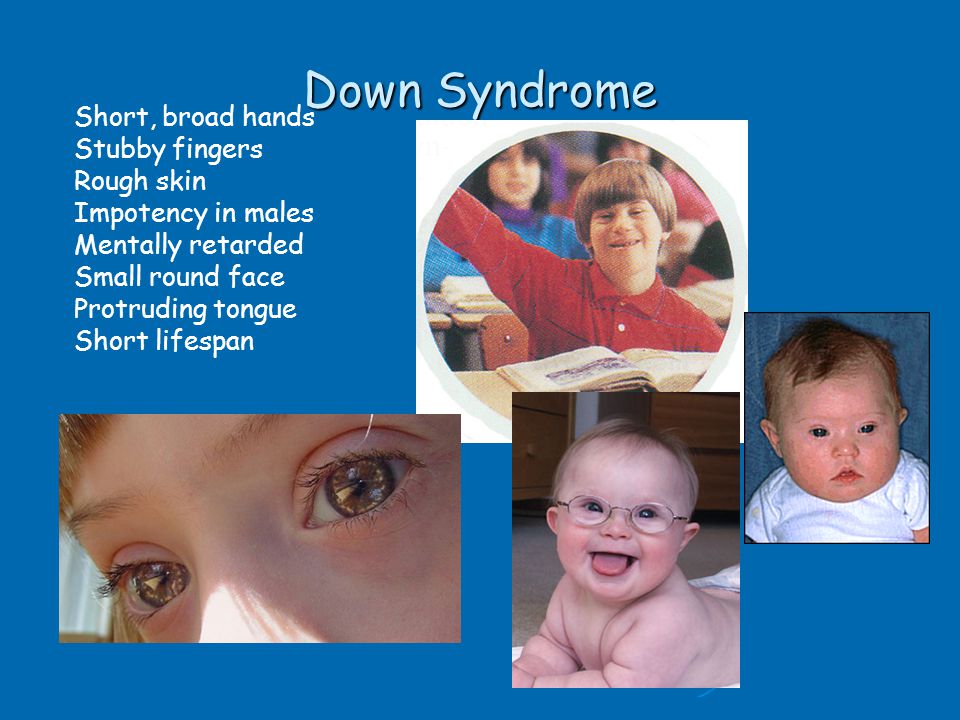

Down's syndrome causes some level of learning disability.

People with Down's syndrome may be more likely to have other health conditions, such as heart conditions, and problems with the digestive system, hearing and vision. Sometimes these can be serious, but many can be treated.

Read more about Down's syndrome

Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome

Sadly, most babies with Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome will die before or shortly after birth. Some babies may survive to adulthood, but this is rare.

All babies born with Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome will have a wide range of problems, which can be very serious. These may include major complications affecting their brain.

Read more about Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome.

What does screening for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome involve?

Combined test

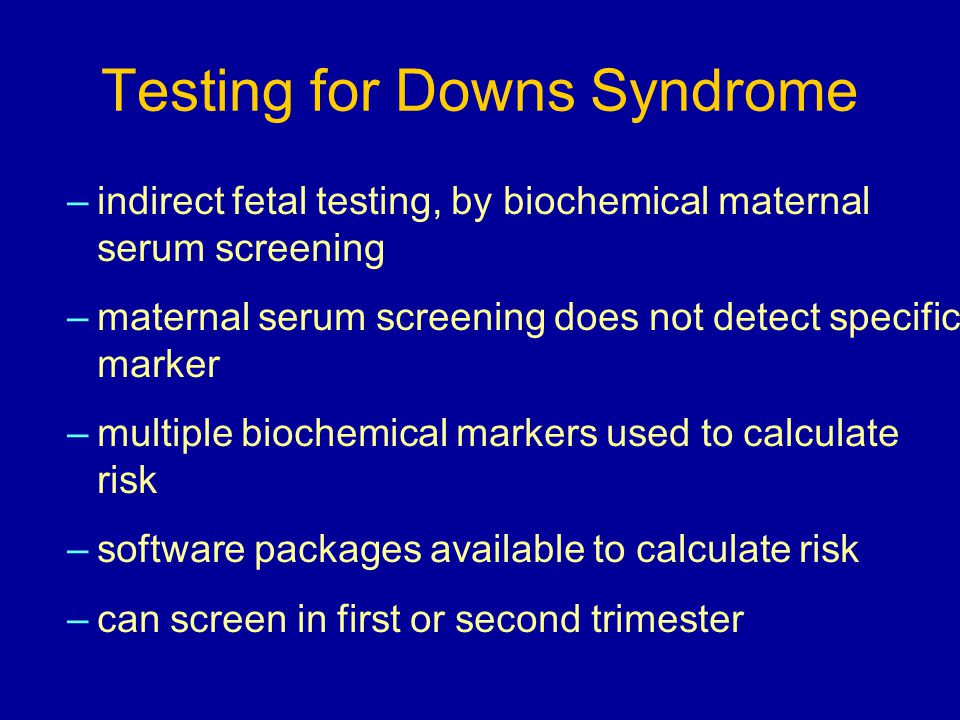

A screening test for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome is available between weeks 10 and 14 of pregnancy. It's called the combined test because it combines an ultrasound scan with a blood test. The blood test can be carried out at the same time as the 12-week scan.

It's called the combined test because it combines an ultrasound scan with a blood test. The blood test can be carried out at the same time as the 12-week scan.

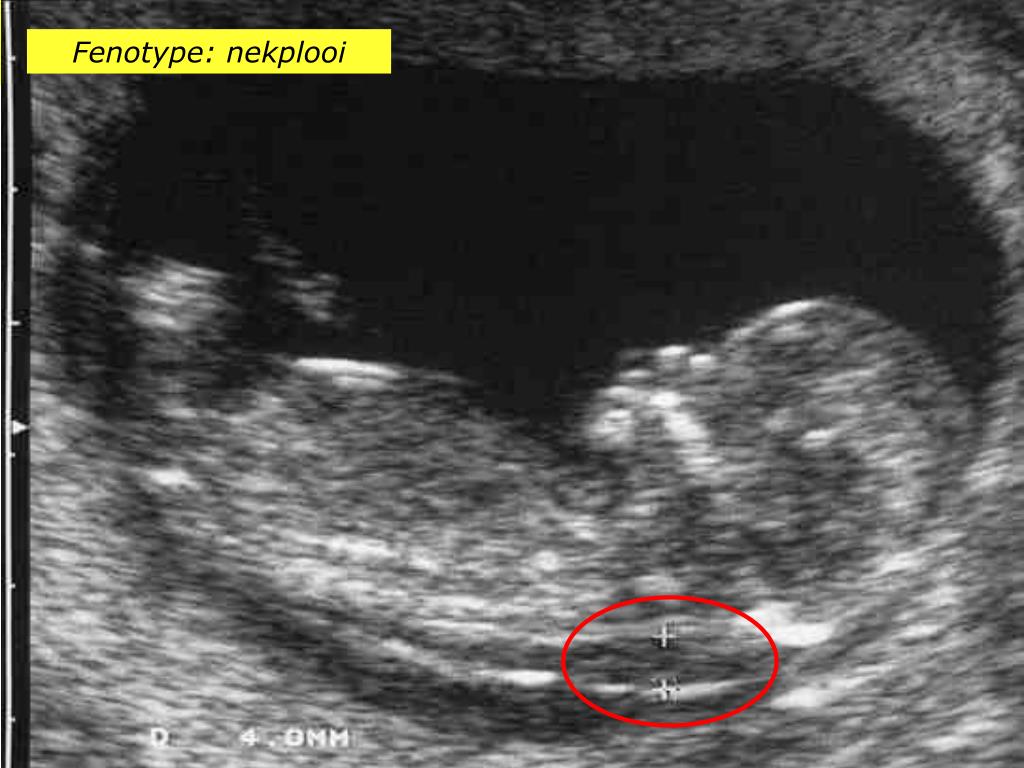

If you choose to have the test, you will have a blood sample taken. At the scan, the fluid at the back of the baby's neck is measured to determine the "nuchal translucency". Your age and the information from these 2 tests are used to work out the chance of the baby having Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome.

Obtaining a nuchal translucency measurement depends on the position of the baby and is not always possible. If this is the case, you will be offered a different blood screening test, called the quadruple test, when you're 14 to 20 weeks pregnant.

Quadruple blood screening test

If it was not possible to obtain a nuchal translucency measurement, or you're more than 14 weeks into your pregnancy, you'll be offered a test called the quadruple blood screening test between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy. This only screens for Down's syndrome and is not as accurate as the combined test.

This only screens for Down's syndrome and is not as accurate as the combined test.

20-week screening scan

For Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome, if you are too far into your pregnancy to have the combined test, you'll be offered a 20-week screening scan. This looks for physical conditions, including Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome.

Can this screening test harm me or my baby?

The screening test cannot harm you or the baby, but it's important to consider carefully whether to have this test.

It cannot tell you for certain whether the baby does or does not have Down's syndrome, Edward's syndrome or Patau's syndrome, but it can provide information that may lead to further important decisions. For example, you may be offered diagnostic tests that can tell you for certain whether the baby has these conditions, but these tests have a risk of miscarriage.

Do I need to have screening for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome?

You do not need to have this screening test – it's your choice. Some people want to find out the chance of their baby having these conditions while others do not.

You can choose to have screening for:

- all 3 conditions

- Down's syndrome only

- Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome only

- none of the conditions

What if I decide not to have this test?

If you choose not to have the screening test for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome, you can still choose to have other tests, such as a 12-week scan.

If you choose not to have the screening test for these conditions, it's important to understand that if you have a scan at any point during your pregnancy, it could pick up physical conditions.

The person scanning you will always tell you if any conditions are found.

Getting your results

The screening test will not tell you whether your baby does or does not have Down's, Edwards' or Patau's syndromes – it will tell you if you have a higher or lower chance of having a baby with one of these conditions.

If you have screening for all 3 conditions, you will receive 2 results: 1 for your chance of having a baby with Down's syndrome, and 1 for your joint chance of having a baby with Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome.

If your screening test returns a lower-chance result, you should be told within 2 weeks. If it shows a higher chance, you should be told within 3 working days of the result being available.

This may take a little longer if your test is sent to another hospital. It may be worth asking the midwife what happens in your area and when you can expect to get your results.

You will be offered an appointment to discuss the test results and the options you have.

The charity Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC) offers lots of information about screening results and your options if you get a higher-chance result.

Possible results

Lower-chance result

If the screening test shows that the chance of having a baby with Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome is lower than 1 in 150, this is a lower-chance result. More than 95 out of 100 screening test results will be lower chance.

A lower-chance result does not mean there's no chance at all of the baby having Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome.

Higher-chance result

If the screening test shows that the chance of the baby having Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome is higher than 1 in 150 – that is, anywhere between 1 in 2 and 1 in 150 – this is called a higher-chance result.

Fewer than 1 in 20 results will be higher chance. This means that out of 100 pregnancies screened for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome, fewer than 5 will have a higher-chance result.

A higher-chance result does not mean the baby definitely has Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome.

Will I need further tests?

If you have a lower-chance result, you will not be offered a further test.

If you have a higher-chance result, you can decide to:

- not have any further testing

- have a second screening test called non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) – this is a blood test, which can give you a more accurate screening result and help you to decide whether to have a diagnostic test or not

- have a diagnostic test, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS) straight away – this will tell you for certain whether or not your baby has Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome, but in rare cases can cause a miscarriage

You can decide to have NIPT for:

- all 3 conditions

- Down's syndrome only

- Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome only

You can also decide to have a diagnostic test after NIPT.

NIPT is completely safe and will not harm your baby.

Discuss with your healthcare professional which tests are right for you.

Whatever results you get from any of the screening or diagnostic tests, you will get care and support to help you to decide what to do next.

If you find out your unborn baby has Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome

If you find out your baby has Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome or Patau's syndrome a specialist doctor (obstetrician) or midwife will talk to you about your options .

You can read more about what happens if antenatal screening tests find something.

You may decide to continue with the pregnancy and prepare for your child with the condition.

Or you may decide that you do not want to continue with the pregnancy and have a termination.

If you are faced with this choice, you will get support from health professionals to help you make your decision.

For more information see GOV.UK: Screening tests for you and your baby

The charity Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC) runs a helpline from Monday to Friday, 10am to 5.30pm on 020 7713 7486.

The Down's Syndrome Association also has useful information on screening.

The charity SOFT UK offers information and support through diagnosis, bereavement, pregnancy decisions and caring for all UK families affected by Edwards' syndrome (T18) or Patau's syndrome (T13).

Edwards' syndrome (trisomy 18) - NHS

Edwards' syndrome, also known as trisomy 18, is a rare but serious condition.

Edwards' syndrome affects how long a baby may survive. Sadly, most babies with Edwards' syndrome will die before or shortly after being born.

A small number (about 13 in 100) babies born alive with Edwards' syndrome will live past their 1st birthday.

Cause of Edwards' syndrome

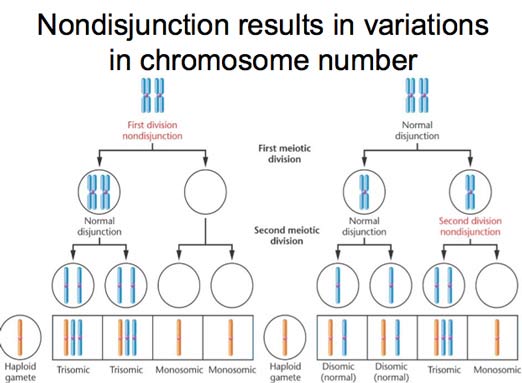

Each cell in your body usually contains 23 pairs of chromosomes, which carry the genes you inherit from your parents.

A baby with Edwards' syndrome has 3 copies of chromosome number 18 instead of 2. This affects the way the baby grows and develops. Having 3 copies of chromosome 18 usually happens by chance, because of a change in the sperm or egg before a baby is conceived.

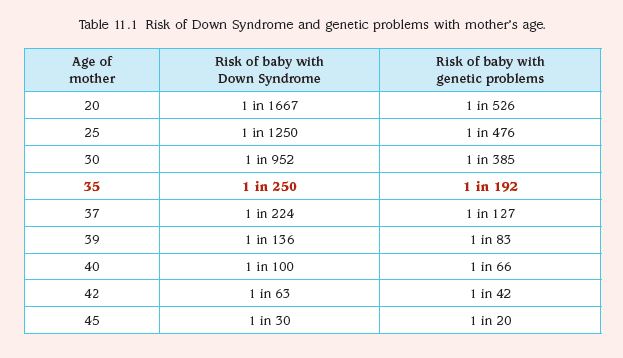

Your chance of having a baby with Edwards' syndrome increases as you get older, but anyone can have a baby with Edwards' syndrome. The condition does not usually run in families and is not caused by anything the parents have or have not done.

Speak to a GP if you want to find out more. They may be able to refer you to a genetic counsellor.

They may be able to refer you to a genetic counsellor.

The symptoms, and how seriously your baby is affected, usually depend on whether they have full, mosaic, or partial Edwards' syndrome.

Full Edwards' syndrome

Most babies with Edwards' syndrome have an extra chromosome 18 present in all cells. This is called full Edwards' syndrome.

The effects of full Edward's syndrome are often more severe. Sadly, most babies with this form will die before they are born.

Mosaic Edwards' syndrome

A small number of babies with Edwards' syndrome (about 1 in 20) have an extra chromosome 18 in just some cells. This is called mosaic Edwards' syndrome (or sometimes mosaic trisomy 18).

This can lead to milder effects of the condition, depending on the number and type of cells that have the extra chromosome. Most babies with this type of Edward's syndrome who are born alive will live for at least a year, and they may live to adulthood.

Most babies with this type of Edward's syndrome who are born alive will live for at least a year, and they may live to adulthood.

Partial Edwards' syndrome

A very small number of babies with Edwards' syndrome (about 1 in 100) have only a section of the extra chromosome 18 in their cells, rather than a whole extra chromosome 18. This is called partial Edwards' syndrome (or sometimes partial trisomy 18).

How partial Edwards' syndrome affects a baby depends on which part of chromosome 18 is present in their cells.

Advice for new parents

There's support available for whatever you or your baby needs.

All babies born with Edwards' syndrome will have some level of learning disability.

Edwards' syndrome is associated with certain physical features and health problems. Every baby is unique and will have different health problems and needs. They will usually have a low birthweight and may also have a wide range of physical symptoms. They may also have heart, respiratory, kidney or gastrointestinal conditions.

Every baby is unique and will have different health problems and needs. They will usually have a low birthweight and may also have a wide range of physical symptoms. They may also have heart, respiratory, kidney or gastrointestinal conditions.

Despite their complex needs, children with Edwards' syndrome can slowly start to do more things.

Like any child they'll:

- have their own personality

- learn at their own pace

- have things that are important and unique to them

Try not to think too far ahead and enjoy time with your baby.

Screening for Edwards' syndrome

If you're pregnant, you'll be offered screening for Edwards' syndrome between 10 and 14 weeks of pregnancy. This looks at the chance of your baby having the condition.

This screening test is called the combined test and it works out the chance of a baby having Edwards' syndrome, Down's syndrome and Patau's syndrome.

During the test you'll have a blood test and an ultrasound scan to measure the fluid at the back of your baby's neck (nuchal translucency).

Read more about screening for Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome at 10 to 14 weeks

If it's not possible to measure the fluid at the back of your baby's neck, or you're more than 14 weeks pregnant, you'll be offered screening for Edwards' syndrome as part of your 20-week scan. This is sometimes known as the mid-pregnancy scan. It's an ultrasound scan that looks at how your baby is growing.

Screening cannot identify which form of Edwards' syndrome your baby may have, or how it will affect them.

Read more about the 20-week scan

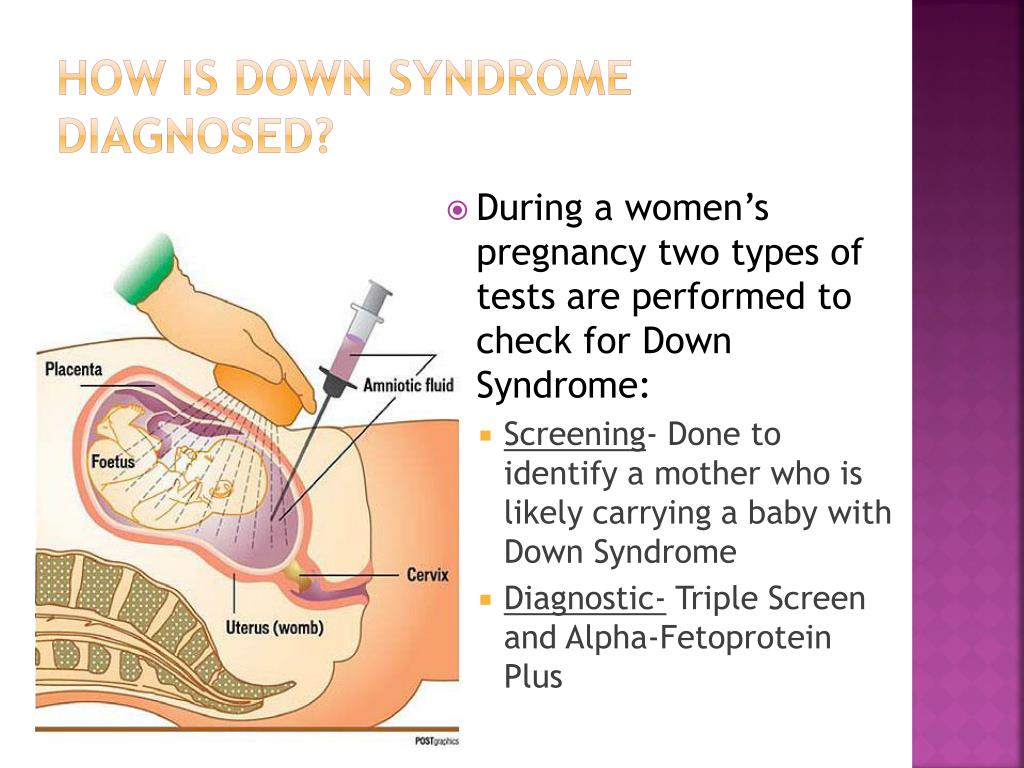

Diagnosing Edwards' syndrome during pregnancy

If the combined test shows that you have a higher chance of having a baby with Edwards' syndrome, you'll be offered a test to find out for certain if your baby has the condition.

This diagnostic test involves analysing a sample of your baby's cells to check if they have an extra copy of chromosome 18.

There are 2 different ways of getting this sample of cells:

- chorionic villus sampling, which collects a sample from the placenta

- amniocentesis, which collects a sample of the amniotic fluid from around your baby

These are invasive tests that increase your chance of having a miscarriage. Your doctor will discuss this with you.

Results from the diagnostic test

A specialist doctor (obstetrician) or midwife will explain what the screening results mean and talk to you about your options.

This is a very difficult situation and it's normal to feel a whole range of emotions. It may help to talk to your doctor, family and friends, or partner about what you're thinking and how you're feeling.

If you're told your baby has Edwards' syndrome, either before birth or afterwards, you'll be offered support and information.

You can visit the SOFT UK website for support and more information on Edwards' syndrome, and to contact other families affected by the condition.

You can also contact Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC), which has information about screening tests and how you might feel if you're told your baby does have, or might have, a problem.

ARC has a helpline that can be reached on 0845 077 2290, or 0207 713 7486 from a mobile, Monday to Friday, 10am to 5.30pm. The helpline is answered by trained staff, who can offer information and support.

Read more about what happens if antenatal screening tests find something

Diagnosing Edwards' syndrome after birth

If doctors believe your baby has Edwards' syndrome after they're born, a blood sample will be taken to see if there are extra copies of chromosome 18.

Treating Edwards' syndrome

There's no cure for Edwards' syndrome.

Treatment will focus on the symptoms of the condition, such as heart conditions, breathing difficulties and infections. Your baby may also need to be fed through a feeding tube, as they can often have difficulty feeding.

Edwards' syndrome has an impact on your baby's movements as they get older, and they may benefit from supportive treatment such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy.

Depending on your baby's specific symptoms, they may need specialist care in hospital or a hospice, or you may be able to look after them at home with the right support.

Advice for carers

Supporting someone with Edwards' syndrome can be both rewarding and challenging.

If you need help, or just want someone to talk to, there's lots of support available.

Your guide to social care and support provides lots of advice on how you can take time to look after yourself, including:

- getting a break from caring

- getting legal support and advocacy

- taking care of your wellbeing

Speak to parents and families

It can help to speak to other parents and families who know how you're feeling.

You can do this by:

- getting in touch with people on forums and social media

- going to a support group – ask your midwife or health visitor about available support groups

Information about your baby

If your baby is found to have Edwards' syndrome before or after their birth, their clinical team will pass the information about them to the National Congenital Anomaly and Rare Disease Registration Service (NCARDRS).

This helps scientists look for better ways to treat the symptoms of the condition. You can opt out of the register at any time.

Find out more about the register at GOV.UK

Having a child with Edwards' syndrome (trisomy 18)

3 families share their experience of having a child with Edwards' syndrome, also called trisomy 18. This video contains sensitive content that some may find upsetting.

Media last reviewed: 20 April 2022

Media review due: 20 April 2025

Page last reviewed: 25 September 2020

Next review due: 25 September 2023

Screening tests for Down syndrome in the first 24 weeks of pregnancy

Relevance

Down's syndrome (also known as Down's disease or Trisomy 21) is an incurable genetic disorder that causes significant physical and mental health problems and disability. However, Down syndrome affects people in completely different ways. Some have significant symptoms, while others have minor health problems and are able to lead relatively normal lives. There is no way to predict how badly a child might be affected.

Some have significant symptoms, while others have minor health problems and are able to lead relatively normal lives. There is no way to predict how badly a child might be affected.

Expectant parents during pregnancy are given the opportunity to have a screening test for Down syndrome in their baby to help them make a decision. If a mother is carrying a child with Down syndrome, then a decision should be made whether to terminate the pregnancy or keep it. The information gives parents the opportunity to plan life with a child with Down syndrome.

The most accurate screening tests for Down syndrome include amniotic fluid (amniocentesis) or placental tissue (chorionic villus biopsy (CVS)) to identify abnormal chromosomes associated with Down syndrome. Both of these tests involve inserting a needle into the mother's abdomen, which is known to increase the risk of miscarriage. Thus, screening tests are not suitable for all pregnant women. Therefore, more often take blood and urine tests of the mother, and also conduct an ultrasound examination of the child. These screening tests are not perfect because they can miss cases of Down syndrome and are also at high risk of being positive when the child does not have Down syndrome. Thus, if a high risk is identified using these screening tests, further amniocentesis or CVS is required to confirm the diagnosis of Down syndrome.

These screening tests are not perfect because they can miss cases of Down syndrome and are also at high risk of being positive when the child does not have Down syndrome. Thus, if a high risk is identified using these screening tests, further amniocentesis or CVS is required to confirm the diagnosis of Down syndrome.

What we did

We analyzed combinations of serum screening tests in the first (up to 14 weeks) and second (up to 24 weeks) trimesters of pregnancy with or without ultrasound screening in the first trimester. Our goal was to identify the most accurate tests for predicting the risk of Down syndrome during pregnancy. One ultrasound index (neckfold thickness) and seven different serological indexes (PAPP-A, total hCG, free beta-hCG, unbound estriol, alpha-fetoprotein, inhibin A, ADAM 12) were studied, which can be used separately, in ratios or in combination with each other, obtained before 24 weeks of gestation, thereby obtaining 32 screening tests for the detection of Down's syndrome. We found 22 studies involving 228615 pregnant women (including 1067 fetuses with Down syndrome).

What we found

During Down Syndrome screening, which included tests during the first and second trimesters that combined to determine overall risk, we found that a test that included neckfold measurement and PAPP- A in the first trimester, as well as the determination of total hCG, unbound estriol, alpha-fetoprotein and inhibin A in the second trimester, turned out to be the most sensitive, as it allowed to determine 9out of 10 pregnancies associated with Down syndrome. Five percent of pregnant women who were determined to be at high risk on this combination of tests would not have a child with Down syndrome. There have been relatively few studies evaluating these tests, so we cannot draw firm conclusions or recommendations about which test is best.

Other important information to consider

Ultrasounds by themselves have no adverse effects on women, and blood tests can cause discomfort, bruising, and, in rare cases, infection. However, some women who have a high-risk Down syndrome baby on screening and who have had an amniocentesis or CVS are at risk of miscarriage of a non-Down syndrome baby. Parents will need to weigh this risk when deciding whether to perform amniocentesis or CVS after a "high risk" screening test is identified.

However, some women who have a high-risk Down syndrome baby on screening and who have had an amniocentesis or CVS are at risk of miscarriage of a non-Down syndrome baby. Parents will need to weigh this risk when deciding whether to perform amniocentesis or CVS after a "high risk" screening test is identified.

Translation notes:

Translation: Abuzyarova Daria Leonidovna. Editing: Prosyukova Ksenia Olegovna, Yudina Ekaterina Viktorovna. Project coordination for translation into Russian: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia (branch of the Northern Cochrane Center on the basis of Kazan Federal University). For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]; [email protected]

Reliability of 1st trimester screening - an article from the Lek-Diagnostic clinic network

1st trimester screening: what is it?

Screening of the 1st trimester is a comprehensive examination aimed at assessing the rate of intrauterine development of the baby by comparing the indicators of a specific gestational age. At this stage, the probability of congenital pathological abnormalities, including Down syndrome, is determined. Screening of the 1st trimester includes two procedures: a biochemical blood test and an ultrasound examination.

At this stage, the probability of congenital pathological abnormalities, including Down syndrome, is determined. Screening of the 1st trimester includes two procedures: a biochemical blood test and an ultrasound examination.

Biochemical blood test

Using biochemistry, you can determine the level of hormones that affect the development of genetic abnormalities:

1. B-hCG - is produced from the beginning of pregnancy, from the 9th week the indicator begins to decline. The norm is 50 thousand-55 thousand. mIU/ml.

2. PAPP-A is an A-plasma protein. A natural indicator is 0.79-6.00 mU / l. during the 1st trimester screening period.

The procedure is carried out in the period from 11 to 13 weeks. A woman donates venous blood in the morning on an empty stomach. Among the contraindications: signs of multiple pregnancy, weight problems, diabetes. Biochemistry is mandatory for women after 35 years of age, with genetic anomalies in the family, with miscarriages or infectious diseases in the past.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is a safe and informative diagnostic method. It allows you to localize the location of the fetus, its physique, compliance with the size of the norm, and also to identify how correctly the limbs of the unborn child are located.

According to the results of the first ultrasound, the doctor:

Determines the date of conception, and also corrects the gestational age;

Establishes or refutes the fact of the presence of congenital pathologies;

Estimates the likelihood of pathological pregnancy.

Ultrasound is performed in two ways: transvaginally (the sensor is inserted into the vagina) or abdominally (the sensor is driven along the abdomen). It is optimal to perform the procedure at the 12th week of pregnancy.

Why are parents afraid of Down syndrome?

Down syndrome is a common genetic syndrome. Normally, a set of chromosomes in humans contains 23 pairs. With a genetic anomaly, a mutation of chromosome 21 leads to trisomy - the presence of an extra 21 chromosome. The pathology was first diagnosed in 1866 by John Down. At the moment, the probability of developing the syndrome is 1 in 700 children.

The pathology was first diagnosed in 1866 by John Down. At the moment, the probability of developing the syndrome is 1 in 700 children.

Why can't Down syndrome be seen on ultrasound?

It is impossible to make an accurate diagnosis of Down syndrome using ultrasound. Based on the results of the procedure, the specialist evaluates the condition of the fetus according to the following parameters:

1. Thickened neck fold. Normally, it is 1.6-1.7 mm. A thickness of 3 mm indicates the likelihood of chromosomal abnormalities.

2. KTR (fetal length). The normal figure varies from 43 to 65 mm (for a period of 12-13 weeks).

At the next stage, calculations are carried out, the risk of genetic abnormalities is examined. A probability higher than 1:360 is high - however, this is not a diagnosis, but an assumption.

What to do if you are at high risk for Down syndrome?

According to statistics, 70% of women carrying a child with Down syndrome are at risk. In this case, the woman is invited to undergo an additional examination at the medical genetic center. The specialist prescribes a series of tests and amniocentesis is practiced as an invasive diagnosis.

In this case, the woman is invited to undergo an additional examination at the medical genetic center. The specialist prescribes a series of tests and amniocentesis is practiced as an invasive diagnosis.

Features of invasive diagnostics

Amniocentesis is the analysis of amniotic fluid. The procedure is performed by puncturing the abdomen in the area of the embryonic membrane. Its result is a sample of amniotic fluid, which contains fetal cells.

Amniocentesis is performed by one of two methods:

1. Free hand method. An ultrasound sensor helps to avoid risks - a specialist performs a puncture in the place where the placenta is absent.

2. Method of puncture adapter. In this case, the ultrasound sensor fixes the needle, after which the trajectory along which it will go is determined.

The procedure takes 5 to 10 minutes. Many parents refuse to take it - in 1% of cases, the test provokes a miscarriage. However, with a high risk of genetic pathology, amniocentesis is a necessary procedure.