Death after birth

What is a neonatal death?

What is a neonatal death? | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content4-minute read

Listen

A neonatal death is when a baby dies within the first 4 weeks after they are born. Dealing with a neonatal death can be very difficult for the whole family, but there is help and support available.

What is a neonatal death?

A neonatal death (also called a newborn death) is when a baby dies during the first 28 days of life. Most neonatal deaths happen in the first week after birth.

Neonatal death is different from stillbirth. A stillbirth is when the baby dies at any time between 20 weeks of pregnancy and the due date of birth.

Globally around 2.4 million children die in the first 28 days after birth. This is around half of all child deaths under the age of 5.

Neonatal death is rare in Australia, and rates are falling — there are about 700 neonatal deaths a year in Australia.

What are the causes of a neonatal death?

It’s not always known why a baby dies. However, the risk of neonatal death may be greater if a baby is born prematurely, is low birthweight, or has birth defects.

Prematurity and low birthweight cause about 1 in 4 neonatal deaths. Premature babies can develop life-threatening complications such as breathing problems, bleeding on the brain, infections and problems in their intestines (necrotising enterocolitis).

Low birthweight — if the baby weighs less than 2.5kg at birth — can also cause serious health problems such as difficulty breathing and feeding.

The most common birth defects that cause neonatal death include heart defects, lung defects, genetic conditions and brain conditions such as neural tube defect or anencephaly.

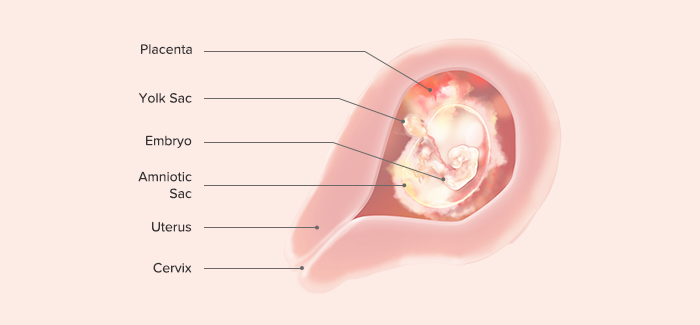

Sometimes a neonatal death may be caused by problems during the pregnancy, such as pre-eclampsia, problems with the placenta, or infections. It can also be caused by complications during the labour — for example, if the baby didn’t get enough oxygen.

It can also be caused by complications during the labour — for example, if the baby didn’t get enough oxygen.

What happens after a neonatal death?

If your baby dies, you might want to spend some time with them. You should take as long as you like. Some parents create memories of the baby by taking photos, handprints and footprints.

When you are ready to say goodbye, the hospital or a funeral director will take your baby to a funeral home. There will then be a burial or cremation.

By law, you must register both the birth and the death with Births, Deaths and Marriages in your state or territory.

In Australia, not all neonatal deaths are investigated by conducting an autopsy, also known as a post mortem examination. An autopsy is an examination to try to work out why the baby has died.

An autopsy cannot be done without the parents’ consent and it is up to you whether to agree to an autopsy after a neonatal death. The only time when an autopsy may be carried out without consent is if the case is referred to a coroner. This might happen if the death occurred in suspicious circumstances or if it was something to do with the health care the baby received.

This might happen if the death occurred in suspicious circumstances or if it was something to do with the health care the baby received.

An autopsy is done by a trained pathologist. If you agree to an autopsy, you can decide how detailed you would like it to be — whether it involves just examining the baby or removing organs to test why the death has happened.

Sometimes no cause of death can be found, even after an autopsy. It’s a good idea to discuss the benefits and downsides of an autopsy with a doctor, midwife or social worker. They will guide you through what needs to be done and will answer any questions you might have.

Learn more here about what happens after a neonatal death and what changes might occur to your body.

Where to find help

The death of a newborn baby can be devastating, both for the parents and for the whole family. So it’s important to get as much support as possible to help you through this difficult time.

Your doctor, midwife, maternal child health nurse or social worker will be able to guide you through what happens after the baby has died.

Sands Australia provides information and support for anyone who has experienced stillbirth or newborn death. You can speak to someone 24 hours a day on their helpline, 1300 072 637.

Red Nose Grief and Loss has information and resources. You can call their helpline 24 hours a day on 1300 308 307.

Lifeline supports anyone having a personal crisis — call 13 11 14 or chat online.

You can call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby on 1800 882 436 to talk to a maternal child health nurse.

Sources:

World Health Organization (Newborn deaths and illnesses), Raising Children Network (Neonatal death - a guide), March of Dimes (Neonatal death), The Royal Women’s Hospital Melbourne (Learning why a baby has died), Queensland Courts (Reportable deaths), Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Stillbirth and neonatal deaths in Australia), Sands (Stillborn and newborn death), myDr (Low-birth-weight babies)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: April 2021

Back To Top

Related pages

- Your body after stillbirth or neonatal death

- Dealing with a neonatal death

- Birth trauma (emotional)

Need more information?

Baby and Infant Death

Baby and Infant Death A neonatal death is when a baby is born alive but dies within the first 28 days of life

Read more on Gidget Foundation Australia website

Death of a baby - Better Health Channel

Miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death is a shattering event for those expecting a baby, and for their families. Grief, relationship stresses and anxiety about subsequent pregnancies are common in these circumstances.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

When Your Baby is Stillborn or Dies Soon After Birth | Guiding Light - Red Nose Grief and Loss

Read more on Red Nose website

Breast care for breastfeeding mothers after the death of a child | Sydney Children's Hospitals Network

Time after the death of your infant can be physically and emotionally exhausting

Read more on Sydney Children's Hospitals Network website

Smoking | Red Nose Australia

Read more on Red Nose website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Maternal Mortality in the United States: A Primer

In 2017, at a time when maternal mortality was declining worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the U.S. was one of only two countries (along with the Dominican Republic) to report a significant increase in its maternal mortality ratio (the proportion of pregnancies that result in death of the mother) since 2000. While U.S. maternal deaths have leveled in recent years, the ratio is still higher than in comparable countries, and significant racial disparities remain.

Understanding the evidence on maternal mortality and its causes is a key step in crafting health care delivery and policy solutions at the state or federal level. This data brief draws on a range of recent and historical data sets to present the state of maternal health in the United States today.

This data brief draws on a range of recent and historical data sets to present the state of maternal health in the United States today.

Highlights

- The most recent U.S. maternal mortality ratio, or rate, of 17.4 per 100,000 pregnancies represented approximately 660 maternal deaths in 2018. This ranks last overall among industrialized countries.

- More than half of recorded maternal deaths occur after the day of birth.

- The maternal death ratio for Black women (37.1 per 100,000 pregnancies) is 2.5 times the ratio for white women (14.7) and three times the ratio for Hispanic women (11.8).

- A Black mother with a college education is at 60 percent greater risk for a maternal death than a white or Hispanic woman with less than a high school education.

- Causes of death vary widely, with death from hemorrhage most likely during pregnancy and at the time of birth and deaths from heart conditions and mental health–related conditions (including substance use and suicide) most common in the postpartum period.

- State ratios vary widely: in 2018, some states reported more than 30 maternal deaths per 100,000 births, while others reported fewer than 15.

There are three commonly used measures of maternal deaths in the United States. It is important to note that, while they all capture some aspect of maternal deaths, they are not equivalent.

Pregnancy-associated mortality: Death while pregnant or within one year of the end of the pregnancy, irrespective of cause. This is the starting point for analyses of maternal deaths.

Pregnancy-related mortality: Death during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy from: a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy. Used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to report U.S. trends, this measure is typically reported as a ratio per 100,000 live births. In this brief, when we discuss causes of maternal deaths and current rates, we will generally be using pregnancy-related mortality as our index.

In this brief, when we discuss causes of maternal deaths and current rates, we will generally be using pregnancy-related mortality as our index.

Maternal mortality ratio: Death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes. Used by the World Health Organization in international comparisons, this measure is reported as a ratio per 100,000 live births. When we examine historical trends, we will be using maternal mortality as our index.

There are various causes of maternal mortality; deaths during delivery are significant but only a part of the problem. Slightly more than half (52%) of all deaths occur after the day of delivery, while almost a third occur during pregnancy. There have been considerable efforts to improve clinical care, but efforts that focus on the birth hospitalization will only solve a portion of the problem. To improve outcomes, it will also be critical to address causes of maternal mortality that arise during pregnancy (such as hypertension, or high blood pressure) and in the postpartum period (such as cardiomyopathy, or weakened heart muscle), through upgrades to women’s health care before, during, and after pregnancy.

To improve outcomes, it will also be critical to address causes of maternal mortality that arise during pregnancy (such as hypertension, or high blood pressure) and in the postpartum period (such as cardiomyopathy, or weakened heart muscle), through upgrades to women’s health care before, during, and after pregnancy.

For decades in the U.S. and around the world, maternal mortality dropped as women gained healthier living conditions, better maternity services, safer surgical procedures, and access to antibiotics. Then, 20 years ago, the U.S. maternal mortality ratio began to rise.

Systematic, comprehensive collection of data on maternal mortality in the U.S. began in the early 20th century in individual states. In 1915, the state data began to be compiled into a national estimate; by 1933, all states were participating and the nationally reported ratio was 619 deaths per 100,000 live births. By way of contrast, the ratio in 1927 for England and Wales was 411 per 100,000 and for Italy was 264 per 100,000.

For most of the 20th century, maternal mortality ratios dropped rapidly around the world with the introduction of healthier living conditions, improved maternity services, safer surgical procedures, and antibiotics. By 1960 the U.S. ratio was 37 per 100,000 live births. During the 1980s and into the 1990s, clinical interventions as well as public health efforts further reduced maternal mortality; it declined until the late 1990s, when it leveled off at about nine deaths per 100,000. After 1997, the U.S. ratio began rising again until 2008, when it plateaued at around 14 deaths per 100,000 births.

The focus on improving maternity care in hospitals has had consequences, for example by diminishing the importance of community-based care and overlooking persistent racial and ethnic disparities.

Black–white disparities in maternal mortality have existed since the beginning of the collection of such data. In 1915, the maternal mortality ratio for Black mothers (1,065 per 100,000 births) was 1. 8 times that of white mothers (601).

8 times that of white mothers (601).

As white maternal mortality ratios declined more rapidly than those for Black mothers after World War II, the disparity increased until the maternal mortality ratio for Black mothers was four times that of white mothers. Since the early 1970s, Black mothers have been three to four times more likely to die than white mothers. In the recently reported 2018 maternal mortality data, the Black–white disparity was 2.5 (37.1 for Black mothers vs 14.7 for whites) — the same as the disparity seen in the 1940s.

This figure, drawing on a decade (2007–16) of data on causes of maternal deaths broken down by race/ethnicity, illustrates the diversity of factors that contribute to maternal deaths in different groups. The percentages represent the distribution of causes of deaths within each group.

The same study also reported widely disparate pregnancy-related mortality ratios for each group, specifically: white (12.7), Black (40.8), American Indian/Alaska Native (29. 7), Asian Pacific Islander (13.5), and Hispanic (11.5). For example, hemorrhage (severe bleeding) is a cause of death most frequently seen in pregnancy and at the time of birth. It was the leading cause of death among American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) and Asian Pacific Islanders (APIs), accounting for twice the proportion of deaths as seen among white or Black people. Cardiomyopathy, most commonly seen in the postpartum period, accounts for one of seven deaths among Black and AIAN people, but less than half that proportion among Hispanic and API people.

7), Asian Pacific Islander (13.5), and Hispanic (11.5). For example, hemorrhage (severe bleeding) is a cause of death most frequently seen in pregnancy and at the time of birth. It was the leading cause of death among American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) and Asian Pacific Islanders (APIs), accounting for twice the proportion of deaths as seen among white or Black people. Cardiomyopathy, most commonly seen in the postpartum period, accounts for one of seven deaths among Black and AIAN people, but less than half that proportion among Hispanic and API people.

To reduce such disparities, it is critical to understand the particular risks that women face and then address all relevant factors, including access to treatment before and after birth, the quality of clinical care, the effects of structural racism, and social determinants of health.

While educational advancement is typically seen as protective in terms of health, that’s not the case for Black mothers. Education exacerbates rather than mitigates Black–white differences in maternal deaths. Five times as many Black mothers with a college education die as white mothers with a college education. Mortality ratios for white mothers decrease with higher education, but the difference in mortality risk for a Black mother with less than a high school education and one with a college degree is minimal. This leads to the startling finding that maternal deaths are more common among Black mothers with a college education than they are among white mothers with less than a high school education (40.2 vs. 25.0). Mortality ratios for Hispanic mothers decrease slightly with education but are generally lower at each level.

Five times as many Black mothers with a college education die as white mothers with a college education. Mortality ratios for white mothers decrease with higher education, but the difference in mortality risk for a Black mother with less than a high school education and one with a college degree is minimal. This leads to the startling finding that maternal deaths are more common among Black mothers with a college education than they are among white mothers with less than a high school education (40.2 vs. 25.0). Mortality ratios for Hispanic mothers decrease slightly with education but are generally lower at each level.

It is important to understand the clinical causes of pregnancy-related mortality. According to a recent CDC report, the majority relate to cardiovascular conditions such as heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy) (11%), blood clots (9%), high blood pressure (8%), stroke (7%), and a category combining other cardiac conditions (15%). Infection (13%) and severe postpartum bleeding (11%) are also leading causes. When many of these conditions are identified early, there are clinical interventions that can save lives. And a number of these conditions, particularly cardiomyopathy, occur up to a year after childbirth.

When many of these conditions are identified early, there are clinical interventions that can save lives. And a number of these conditions, particularly cardiomyopathy, occur up to a year after childbirth.

Improvements in hospital care have, according to a recent study, decreased the number of maternal deaths occurring at the time of birth hospitalization. Pregnancy-related mortality ratios associated with hospital care (such as hemorrhage, eclampsia, and infection) have declined in recent years.

In addition to hospital-focused interventions, key efforts involve identifying higher-risk women earlier, enrolling women in insurance, and keeping them in care after childbirth. Additionally, many new mothers feel torn between the economic pressure to return to work and the need to focus primarily on their infant’s health, perhaps at the cost of their own care.

The causes of maternal death vary considerably and depend on when mothers die. These data are based on a report from maternal mortality review committees.

During pregnancy, hemorrhage and cardiovascular conditions are the leading causes of death. At birth and shortly after, infection is the leading cause. In the postpartum period, often during the time when new parents are out of the hospital and beyond the traditional six- or eight-week post-pregnancy visit, cardiomyopathy (weakened heart muscle) and mental health conditions (including substance use and suicide) are identified as leading causes.

The diversity of causes at different times throughout pregnancy until one year postpartum can best be addressed through integrated care delivery models. Those that leverage telehealth, midwives, and doulas can improve access to care. Since almost 7 percent of non-Hispanic Black women in 2018 did not start prenatal care until their third trimester, and an additional 3 percent report no prenatal care at all, efforts to enroll women into insurance early in pregnancy would be an appropriate place to begin. The large proportion of deaths occurring after birth also suggests too many mothers are lost to care after they’ve given birth, a problem exacerbated by current Medicaid policies that drop expanded coverage for pregnant women 60 days after birth.

Given that large-scale policy changes may take longer to implement, there are also more immediate practice changes that can reduce disparities and save lives in the short term; these include increasing support for programs like community-based doulas and wraparound services, which have been found to act as effective buffers against larger social determinants of health.

The varying conditions require different approaches to treatment. Therefore, providing women with optimal care, including mental health care, throughout the 21 months from conception through the year after they have given birth is essential.

State maternal mortality ratios vary widely. The recent report on maternal deaths in 2018 included ratios for the 25 states reporting at least 10 maternal deaths. A cluster of states in the South (Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Oklahoma) reported ratios of greater than 30 per 100,000 live births, while California, Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania all reported ratios less than half the figures in those states.

It is striking that the data are missing for approximately half of all U.S. states and territories. It is expected that with subsequent annual reports, multiple years can be combined to enable the comparison of all states.

Black women are more likely than white women to report that their concerns and preferences regarding birth were disregarded; women with Medicaid coverage reported inadequate postpartum care and support.

Listening to Mothers is a series of national surveys fielded by the nonprofit National Partnership for Women and Families. Below is a summary of some of the key findings from the Listening to Mothers 2011–12 survey, as well as a California survey conducted in 2016, about the experiences of mothers who had hospital births in the United States.

Compared with white women, non-Hispanic Black women were more likely to report:

- Being treated unfairly and with disrespect by providers because of their race

- Not having decision autonomy during labor and delivery

- Feeling pressured to have a cesarean section

- Not exclusively breastfeeding at one week and six months.

Compared with women with private health insurance, women with Medicaid coverage were more likely to report:

- No postpartum visit

- Returning to work within two months of birth

- Less postpartum emotional and practical support at home

- Not having decision autonomy during labor and delivery

- Being treated unfairly and with disrespect by providers because of their insurance status

- Not exclusively breastfeeding at one week and six months.

As these findings illustrate, different women have different experiences with maternity care, childbirth, and parenting. For example, both Black women and those with Medicaid coverage were less likely than white women and those with private health coverage to say they had autonomy about childbirth decisions and were treated with respect by their providers.

When we consider causes of racial and other disparities in maternal mortality, it is essential to consider women’s interactions with the maternity care system and understand how bias and racism manifest in these experiences. Because experiences of pregnancy and parenthood differ by race and insurance coverage, our health care systems need to address structural factors — including racism and bias — that affect treatment while meeting the full needs of all pregnant and birthing people.

Because experiences of pregnancy and parenthood differ by race and insurance coverage, our health care systems need to address structural factors — including racism and bias — that affect treatment while meeting the full needs of all pregnant and birthing people.

Discussion

As these charts show, relatively high maternal mortality ratios in the U.S. as compared with other countries, and disparities between Black and white women, are not new problems, nor are they improving. Even if you looked just at non-Hispanic white women in cross-national comparisons of maternal mortality, the U.S. would still be in last place. Even with varying ways to measure maternal mortality, the U.S. does not perform well on any analysis of this sentinel measure of a society’s health.

Preventing maternal mortality is complicated by the multifactorial nature of the problem. The causes vary across racial and ethnic groups as well as timing — whether during pregnancy, at birth, or postpartum. And a woman’s chance of dying in childbirth is more than twice as high in some states.

The fact that the U.S. has the highest maternal mortality ratio among wealthy countries even when we limit the U.S. data only to white women suggests that our maternal health care system needs dramatic change. The U.S. has to intentionally focus on disparities between Black and white women, in particular by naming and seeking to reduce the impacts of structural racism.

Structural racism leads to disparities in income, housing, safety, education, and other circumstances that are associated with poorer health and increased rates of chronic disease. These, in turn, place Black women at greater risk than white women of pregnancy-related deaths from cardiomyopathy and hypertension, among other causes.

Racism in the health care sector compounds the issue, with Black women less likely to have access to treatment and receive good-quality care. And the intersection of sexism and racism can mean women of color are not listened to or respected by their providers, contributing to preventable morbidity and mortality due to delayed diagnosis or care. This has been reported by women in multiple surveys and illustrated by the high-profile cases of Serena Williams, Shalon Irving, and Kira Johnson.

This has been reported by women in multiple surveys and illustrated by the high-profile cases of Serena Williams, Shalon Irving, and Kira Johnson.

Moreover, although recent efforts to improve hospital maternity care have been valuable, only a third of pregnancy-related deaths occur at the time of birth. We need to improve women’s health services before and after pregnancy — not just at the time of birth.

Policies are also needed to promote continuous health insurance coverage before and after pregnancy. In particular, the large proportion of maternal deaths that occur after childbirth suggests that too many women are losing connections to health care after giving birth.

High maternal mortality in the U.S. is not the result of any single factor, and reducing it will require an integrated effort involving policy and practice changes to improve hospital and community care for all women while advancing racial equity.

How We Conducted This Study

The figures cited in this study are based on data from a wide range of contemporary and historical sources. The historical data are drawn from early national vital statistics reports. The current breakdowns of maternal death by timing of deaths and causes of death are from the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System and the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application, both developed by CDC. The 2018 state ratios were published by the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System. The Listening to Mothers survey methods and results are all available from the National Partnership for Women and Families website.

The historical data are drawn from early national vital statistics reports. The current breakdowns of maternal death by timing of deaths and causes of death are from the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System and the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application, both developed by CDC. The 2018 state ratios were published by the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System. The Listening to Mothers survey methods and results are all available from the National Partnership for Women and Families website.

The National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) provides the official reports of maternal mortality, and in 2020, after a decade-long hiatus, reported a national ratio (17.4 deaths per 100,000 births) for 2018. Meanwhile, the CDC has been publishing a pregnancy-related mortality ratio for more than two decades. However, the CDC data cannot be used to make international comparisons because the CDC reports deaths up to one year postpartum, while other countries report deaths that occur up to 42 days postpartum. While the CDC data could be truncated at 42 days for comparison, the CDC is not allowed to report those rates, because the NVSS is the only governmental body allowed to report an official maternal mortality ratio. Finally, CDC has developed the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application system, for which data from states’ maternal mortality review committees are gathered to produce multistate reports on maternal deaths.

While the CDC data could be truncated at 42 days for comparison, the CDC is not allowed to report those rates, because the NVSS is the only governmental body allowed to report an official maternal mortality ratio. Finally, CDC has developed the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application system, for which data from states’ maternal mortality review committees are gathered to produce multistate reports on maternal deaths.

The major limitation in examining maternal mortality is that there is no single national system in the U.S. for collecting maternal mortality data. Rather, there is a federal system wherein deaths are reported at the local and state levels and those reports conveyed to federal officials. Therefore, the system relies on the quality of data collected locally and the quality-control processes for converting those reports into national data. Documentation and analysis of maternal mortality over time have been hampered by limited funding, changing definitions, and inconsistent reporting by states. These shortcomings have resulted in notable gaps in our understanding of the problem, including the degree of difference in maternal mortality between urban and rural areas, though there is considerable evidence reporting the growing problem of gaps in maternal health services in rural areas.

These shortcomings have resulted in notable gaps in our understanding of the problem, including the degree of difference in maternal mortality between urban and rural areas, though there is considerable evidence reporting the growing problem of gaps in maternal health services in rural areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ebere Oparaeke, M.P.H., and Ruby Barnard Mayers, M.P.H., for research and technical support, and Jodie Katon, Ph.D., for her careful review.

Every 11 seconds a woman or child dies during pregnancy and childbirth

According to a new report prepared by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO). The document provides statistical data on child and maternal mortality worldwide.

Since 2000, child mortality has been cut by almost half and maternal mortality by a third, largely due to affordable and quality health care. Yet globally, 2.8 million pregnant women and babies die every year. In 2017, 29 people died due to complications related to pregnancy and childbirth.0 thousand women. In 2018, 6.2 million children did not reach the age of 15. 5.3 million of them died in the first five years of life and half in the first 12 months after birth.

In 2017, 29 people died due to complications related to pregnancy and childbirth.0 thousand women. In 2018, 6.2 million children did not reach the age of 15. 5.3 million of them died in the first five years of life and half in the first 12 months after birth.

Photo by UNICEF/Ayen

Baby in perinatal center

“In countries that provide everyone with safe, affordable and high-quality health care, women and children survive and thrive,” said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

In a joint statement, WHO and UNICEF called on all countries of the world to intensify their efforts to save women and children. Experts point out that infants are most at risk in poor countries, where pregnant women are malnourished, where there are no basic hygiene conditions and where there are not enough midwives. nine0003

For these reasons, women in sub-Saharan Africa are 50 times more likely to die during childbirth and pregnancy than women in wealthy regions. Similar statistics for child mortality.

“All over the world the birth of a child is a joyful event. Yet every 11 seconds it becomes a family tragedy for someone,” said Henriette Fauré, Executive Director of UNICEF

According to the report, one in 13 children in sub-Saharan Africa died under the age of five in 2018 , while in the countries of Europe as a whole - one of 196. UNICEF experts are also concerned about the high levels of maternal and child mortality in South Asia. The main reasons for such tragic statistics, according to the authors of the report, are the result, first of all, of poverty and inequality. In a joint statement, WHO and UNICEF called on all countries of the world to intensify measures aimed at saving women and children.

All over the world the birth of a child is a joyful event. However, every 11 seconds it becomes a family tragedy for someone

In 2015, the leaders of all countries adopted the Sustainable Development Goals, in one of them they promised to reduce the global maternal mortality rate to less than 70 cases per 100 thousand by 2050, and also to put an end to the unnecessary death of newborns and children under the age of 5 years. At the same time, all countries should strive to reduce neonatal mortality to 12 cases per 1000 births, and the death rate of children under 5 years of age to 25 cases. Today, WHO and UNICEF stressed that $200 billion a year would be needed to achieve these goals in all countries of the world without exception. nine0003

At the same time, all countries should strive to reduce neonatal mortality to 12 cases per 1000 births, and the death rate of children under 5 years of age to 25 cases. Today, WHO and UNICEF stressed that $200 billion a year would be needed to achieve these goals in all countries of the world without exception. nine0003

Investigation and court: Power structures: Lenta.ru

In the Sverdlovsk region, the court put an end to the high-profile case of the tragic death of a 22-year-old woman who died shortly after giving birth in a hospital in the city of Nizhniye Sergi. Anna Malikova, who at that time was the acting head of the obstetric and gynecological department of the city hospital, was accused of the fact that her patient died as a result of a medical error. But the court considered that there was no corpus delicti in the actions of the doctor and the woman died through no fault of hers. However, some episodes of this case leave questions that could not be answered during the trial. The incident called into question the reliability of the regional health care system, and the court decision did little to remedy the situation. Igor Nadezhdin, correspondent of Lenta.ru, dealt with the details of the high-profile case. nine0003

The incident called into question the reliability of the regional health care system, and the court decision did little to remedy the situation. Igor Nadezhdin, correspondent of Lenta.ru, dealt with the details of the high-profile case. nine0003

22-year-old Alisa Tepikina, a resident of the city of Nizhniye Sergi, did not tolerate pregnancy very well: in November 2018, she had stitches in her uterus to avoid premature birth. Alice suffered from toxicosis, during pregnancy she gained a lot of weight, but she complied with all the doctors' prescriptions.

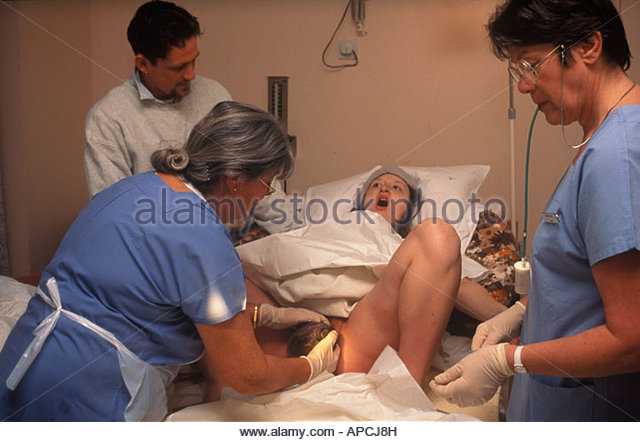

According to the local gynecologist, she was due to give birth on March 3-5, 2019. On February 25, at 09:00, Alice came to the Nizhneserginsky hospital as planned.

I brought my wife exactly at 09:00, as scheduled. On that day, she was to have the stitches removed from her uterus and be kept under observation. But already at 09:15 I received an SMS from Alice that she was being prepared for childbirth and that she would give birth before midnight. It was unexpected

It was unexpected

Nikolay Tepikin

At 09:30 am, Alisa was given an intravenous catheter, and at about 12:40 pm the stitches were removed and her water broke. Then she said that she was put on a drip, after which she was forced to walk, despite the pain. At 03:52, Alice wrote to her husband that the dilatation is almost complete - and now they are waiting for the baby's head to drop down. This was the last message from her. nine0003

Alisa and Nikolai Tepikin

Photo: Nikolai Tepikin's VKontakte page

According to the history of childbirth, at 05:00 Alice began to push, and at 05:50 she gave birth to a healthy girl weighing 3 kilograms 260 grams and height 49 centimeters. As the doctors wrote, “the girl was born alive, full-term, with the umbilical cord wrapped around the leg, torso and neck. She screamed right away." But it is from the moment of birth that oddities begin in this matter.

"Doctor pulled after her hands"

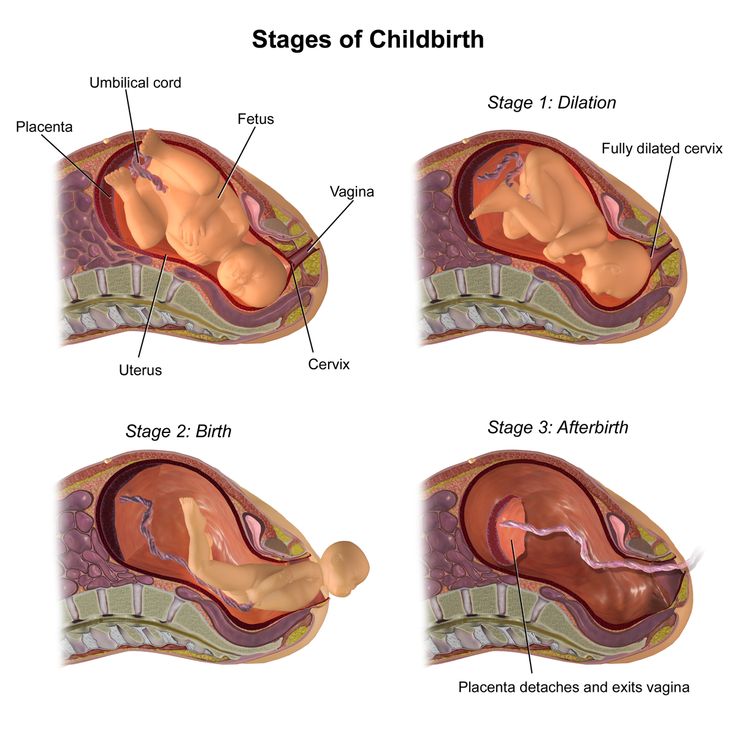

As the representative of the victims, a lawyer and an anesthesiologist-resuscitator Vadim Karataev, explains in an interview with Lenta. ru, after the birth of a child, the afterbirth (placenta) should separate. Previously, in domestic obstetrics, it was believed that the afterbirth should come out on its own, and no later than 30 minutes later - this, they say, is less traumatic.

ru, after the birth of a child, the afterbirth (placenta) should separate. Previously, in domestic obstetrics, it was believed that the afterbirth should come out on its own, and no later than 30 minutes later - this, they say, is less traumatic.

But recently, in the regulatory documents, tactics have changed from passive to active: clamping the umbilical cord, then intramuscular injection of oxytocin to prevent bleeding, and, finally, trial tractions ([sipping - approx. "Tapes.ru" ) for the umbilical cord after the appearance of signs of its separation

Vadim Karataev

Anna Malikova, acting head of the obstetrics and gynecology department of the Nizhneserginsky hospital, at the very first interrogation - still as a witness - told the investigators that the placenta had separated on its own at 06:00, but not completely - one half of it remained in the uterine cavity.

Anna Malikova

Frame: NTV

Both during the investigation and at the trial, Malikova claimed that she did not try to remove the placenta in the case of Alisa Tepikina. However, according to the representative of the victims, lawyer Boris Chentsov, the only witness, a nurse, told the investigators that Malikova pulled the last with her hands. nine0003

However, according to the representative of the victims, lawyer Boris Chentsov, the only witness, a nurse, told the investigators that Malikova pulled the last with her hands. nine0003

The nurse confirmed her testimony at the only confrontation held during the investigation

According to Malikova herself, having found the afterbirth partially released, she immediately called the anesthesiologist on duty Tashtanbaev. It was Tashtanbaev who first suspected massive blood loss in the patient and began to insist on her transfer from the delivery room to the intensive care unit. But Malikova (namely, the obstetrician-gynecologist is considered the main one in the delivery room) categorically refused to follow this recommendation.

At 6:11 am (according to medical records), Dr. Malikova called the surgeon on duty, Igor Torop. He immediately came to the delivery room and soon strongly advised his colleague to contact the obstetricians of the Territorial Center for Disaster Medicine (TCMC) for consultation.

The obstetrician-gynecologist [Malikova] informed me that the patient had placental accreta and that she needed to go for an operation. But my question is what operation? - Anna Malikova did not answer clearly. I do not have a certificate of an obstetrician-gynecologist, I do not know the tactics of managing patients with obstetric pathology, and the nature and extent of the surgical intervention were not objectively explained. The patient herself at that moment was under anesthesia and had no contact. nine0003

I called the Malikov Center only at 06:33. The dispatcher immediately sent a team to Nizhniye Sergi and gave the phone number of the obstetrician-gynecologist, Dr. Oleg Patsuk. While he was on the road, Malikova phoned him at least seven times.

On the way, we called up at least seven times, but Dr. Malikova never told me personally about the bleeding. Moreover, at the first call, even before the decision to leave, she explained in a very calm voice that there were no signs of separation of the placenta and bleeding. nine0003

nine0003

I suspected that the doctor was hiding something and decided to go to the place to find out personally. At the same time, he instructed to continue attempts to separate the placenta, and, if necessary, deploy the operating room and start blood transfusion.

From the moment of the first conversation with Dr. Pacuk, as almost all witnesses explain, Malikova forbade anyone to approach the patient: “The doctors of the TCMC are coming, they forbade touching the patient,” she told everyone.

Malikova herself at that time, as witnesses say, did nothing. Dr. Tashtanbaev, an anesthesiologist-resuscitator on duty, insistently suggested several times to transfer the patient to intensive care, as her blood counts were clearly falling, but Malikova forbade this

Boris Chentsovattorney, representative of the victims

Meanwhile, at 07:35 on February 26, 2019, the head of the intensive care unit, Dr. Galina Medvedeva, a doctor with 30 years of clinical experience, came to work at the Nizhneserginsky Central District Hospital. She saw Alisa Tepikina being taken from the delivery room to the intensive care unit, and decided to examine her herself.

She saw Alisa Tepikina being taken from the delivery room to the intensive care unit, and decided to examine her herself.

Medvedeva threw back the sheet and immediately saw an inverted uterus between her legs. According to the representative of the victims, Boris Chentsov, all witnesses describe the subsequent events in the same way. nine0003

Doctor Medvedeva, seeing the condition of the patient, began to say: “Yes, here you are…” But Malikova interrupted her: “I know. I was ordered not to touch it…” That is, the obstetrician-gynecologist not only did not allow the diagnosis to be announced, but also tried to forbid any manipulations with the patient

Boris ChentsovAttorney for the victims

But Medvedev did not listen: she, who herself worked as a gynecologist in the past, understood that that eversion of the uterus is always accompanied by massive blood loss. And she demanded that Tepika's blood transfusion be started immediately. nine0003

Transfusion into two veins started at 08:00, 2 hours and 10 minutes after delivery. And at 08:10 Alice's heart stopped. Around the functional bed on which Alice was lying, there were several doctors - and they immediately began cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Three minutes later, the patient was brought out of a state of clinical death.

And at 08:10 Alice's heart stopped. Around the functional bed on which Alice was lying, there were several doctors - and they immediately began cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Three minutes later, the patient was brought out of a state of clinical death.

I know that true uterine inversion is accompanied by massive blood loss, but by the time of my examination, blood components had not been ordered, although the transfusiologist was at the hospital from 07:05 on standby

From the testimony of Galina Medvedeva

“She was very cold”

At 08:30 a team from the territorial center for disaster medicine arrived at the Nizhneserginsk Central District Hospital from Yekaterinburg. On examining the patient, they found a complete inversion of the uterus and a diaper soaked with blood under it. To the clarifying question of the doctors “what is it?” Malikova replied: “I didn’t see it.”

According to Malikova, she learned about uterine inversion only during the consultation

Which, however, contradicts the testimony of the resuscitation manager Medvedeva and other witnesses. According to obstetrician-gynecologist Oleg Patsuk (work experience - more than 25 years), Alisa Tepikina's blood loss at that moment was about four liters. nine0003

According to obstetrician-gynecologist Oleg Patsuk (work experience - more than 25 years), Alisa Tepikina's blood loss at that moment was about four liters. nine0003

Later, he will tell his colleagues that he was a little mistaken: the true blood loss was a little less. First, Pacuk separated the placenta - it came off in one piece and with little effort. After that, it was not possible to set the uterus: in the end it had to be removed.

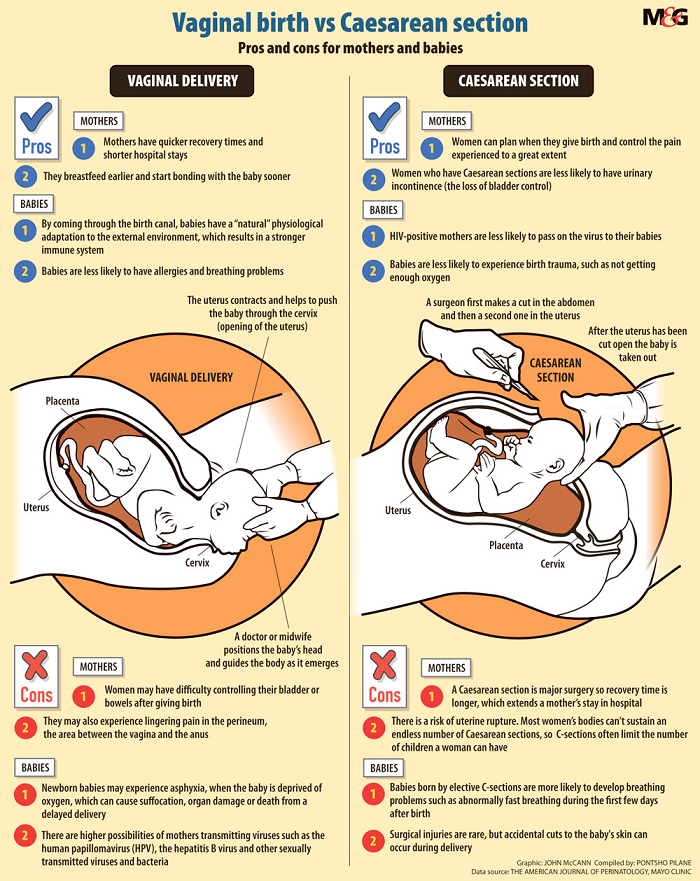

When the uterus is everted, the reproductive organ literally turns inside out and, as a rule, falls out along with the vagina. Doctors distinguish two types of this pathology: spontaneous and obstetric. The first is the consequences of some serious disease, as a result of which the ligamentous apparatus that holds the organ is destroyed, and at the slightest stress (for example, when sneezing), the eversion itself occurs. nine0003

The second is a "gross defect in the provision of medical care." As a rule, the doctor, trying to separate the placenta, inserts his hand into the uterus and captures not only the placenta itself, but also the smooth muscles of the uterus, and then pulls with effort. Correcting the eversion (as doctors say, repositioning) is quite simple: under general anesthesia, the everted uterus is put on a fist and inserted back.

Correcting the eversion (as doctors say, repositioning) is quite simple: under general anesthesia, the everted uterus is put on a fist and inserted back.

The main thing is to do it very quickly before the edema starts (five to ten minutes). Under anesthesia, not because the manipulation is painful, but because anesthesia relieves muscle spasms and does not interfere with the doctor's actions. If the uterus is not quickly returned to its place, then shock develops rapidly (both painful and hemorrhagic - from blood loss), which threatens the death of the mother. nine0003

This pathology, on the one hand, is quite rare (according to statistics, one case per 15 thousand births), but on the other hand, it is significant: it threatens the death of the woman in labor. In most cases, uterine inversion occurs in women who have given birth repeatedly - it is believed that their ligamentous apparatus that holds the uterus attached to the pelvic organs is weakened.

During the investigation and trial, different statistics were announced: some experts said that there was one case per 15,000 births, others that there were only two such cases for 46,000 births in the Sverdlovsk region, and both were in mothers of many children. All of them ended successfully: the women survived. The chief obstetrician-gynecologist of the Sverdlovsk region Anastasia Kuznetsova announced the third figure: in 2018 there were 49thousands of births, and two of them ended in uterine inversion. She did not say anything about the results of these situations.

All of them ended successfully: the women survived. The chief obstetrician-gynecologist of the Sverdlovsk region Anastasia Kuznetsova announced the third figure: in 2018 there were 49thousands of births, and two of them ended in uterine inversion. She did not say anything about the results of these situations.

At 11:10, Alisa Tepikina's heart stopped again, but it was restarted. At about 4:00 pm, an ambulance helicopter flew in from Yekaterinburg, but Tepikina's condition deteriorated sharply, and the doctors refused to transport her because of the threat to the life of a young woman.

Alice's relatives were told about the problems with her only at about seven o'clock in the morning on February 27, and they immediately rushed to the hospital. After a long wait, Medvedev, the head of intensive care, came out to them and said that the condition of the young mother was very serious. She noted that in 30 years of work she had never seen anything like it. Tepikina's parents became ill, both of them were helped. And Alice's husband managed to get into intensive care. nine0003

And Alice's husband managed to get into intensive care. nine0003

Alice was lying very cold, her eyes were covered with gauze. She didn't react to anything. And although I was told that she was alive, it seemed to me that already at that moment she was dead. During the autopsy, the pathologists named the cause of the woman's death as shock of mixed genesis against the background of complete exsanguination. A concomitant diagnosis is complete uterine eversion. The girl born to Alice turned out to be completely healthy and, according to doctors, fully full-term. nine0003

Nizhniye Sergi is a small town. Serious problems in childbirth very quickly became known to everyone, and social networks started talking about the quality of medicine. Moreover, the doctor Anna Malikova turned out to be in the center of attention of the townspeople.

Nizhniye Sergi

Photo: Mapio.net

She was born in 1991. From 2008 to 2016 she studied at the Ural Medical Academy, in 2017 she completed her residency in obstetrics and gynecology. Since September 2017, Malikova was assigned to the Nizhneserginsky hospital, that is, at the time of the tragedy, her medical experience was less than two years. nine0003

Since September 2017, Malikova was assigned to the Nizhneserginsky hospital, that is, at the time of the tragedy, her medical experience was less than two years. nine0003

However, despite this, since the summer of 2018, Malikova has been acting head of the obstetrics and gynecology department. Since March 2018, she also got a part-time job at the Pervouralsk Perinatal Center.

How a person with such little work experience could be appointed to a department, I cannot explain - this is not within my competence, moreover, it was done before I took office

Antonina Kuznetsova interrogation in court

Case in dark spots

The autopsy, which was carried out by the pathologist of the Nizhneserginsky hospital, raises many questions for any more or less competent specialist.

The very first and most important - why was there originally a pathological and anatomical, and not a forensic autopsy? By law, in case of any suspicion of illegal actions, a forensic expert must open it. nine0003

nine0003

And the death of a woman in labor always implies a criminal case

The leading diagnosis is: "Spontaneous eversion of the uterus." The pathologist, having examined the materials, removes the word "spontaneous" and fixes the anemia of all organs, that is, hemorrhagic shock.

It should be especially noted that in the first studies there are no signs of dysplasia (pathology) of the connective tissue, which will appear much later as the main cause of the tragedy. True, where they will come from is not clear. nine0003

Photo: Dmitry Lebedev / Kommersant

In addition, a certain genetic predisposition of the woman in labor to uterine inversion will surface later - supposedly her grandmother had a similar situation during childbirth. During the investigation and trial, this is completely refuted, but at the time of analysis of the case at the regional level, this false information will be the main focus.

A lot of doctors in the Sverdlovsk region talk about serious pressure from the regional Minister of Health and part-time head of the regional medical chamber Andrey Karlov. nine0003

nine0003

He publicly stated that forensic doctors are incompetent in assessing the actions of other doctors

Many experts say that if a medical error is suspected, instructions begin to come from the Ministry of Health. Some admit that they sign the protocols of medical commissions, although they themselves did not take part in the meetings.

It is interesting that in the materials on the case of Dr. Malikova there is a court order to seize medical records in the Nizhneserginsky hospital. As a rule, the chief doctor himself issues all the materials at the request of the investigation, but in this case it was necessary to go to court. This in itself is strange. For this reason, the forensic medical examination was assigned to another region - to Khanty-Mansiysk. nine0003

Dve pravda

The conclusion of the experts from Khanty-Mansiysk is clear: Alisa Tepikina did not have spontaneous uterine inversion. But in her case, there were tractions (sipping) performed by the doctor in the third stage of labor, and with a gross violation of the order of manipulation - the doctor did not hold the uterus through the anterior abdominal wall.

There is a direct causal relationship between the actions of an obstetrician-gynecologist and the onset of death

From the conclusions of experts in Khanty-Mansiysk

But in Khanty-Mansiysk, one negligence was made: an anesthesiologist-resuscitator was not included in the expert commission. Malikova's defense caught on to this and demanded that a new examination be appointed - in the Sverdlovsk region.

The new examination came to the opposite conclusions: according to its data, the cause of Alisa Tepikina's death was a short umbilical cord, connective tissue dysplasia (without emphasis on histological data) and "partial signs of placental separation". nine0003

Nizhniye Sergi hospital

Photo: 66.ru

Experts from Khanty-Mansiysk, who studied all the materials of the criminal case, say: the signs of the separation of the afterbirth of Schroeder, Alfred and Klein, described in the history of childbirth at 05:55, could not have been in fact deed.