Childbirth shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

Shoulder dystocia | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content4-minute read

Listen

What is shoulder dystocia?

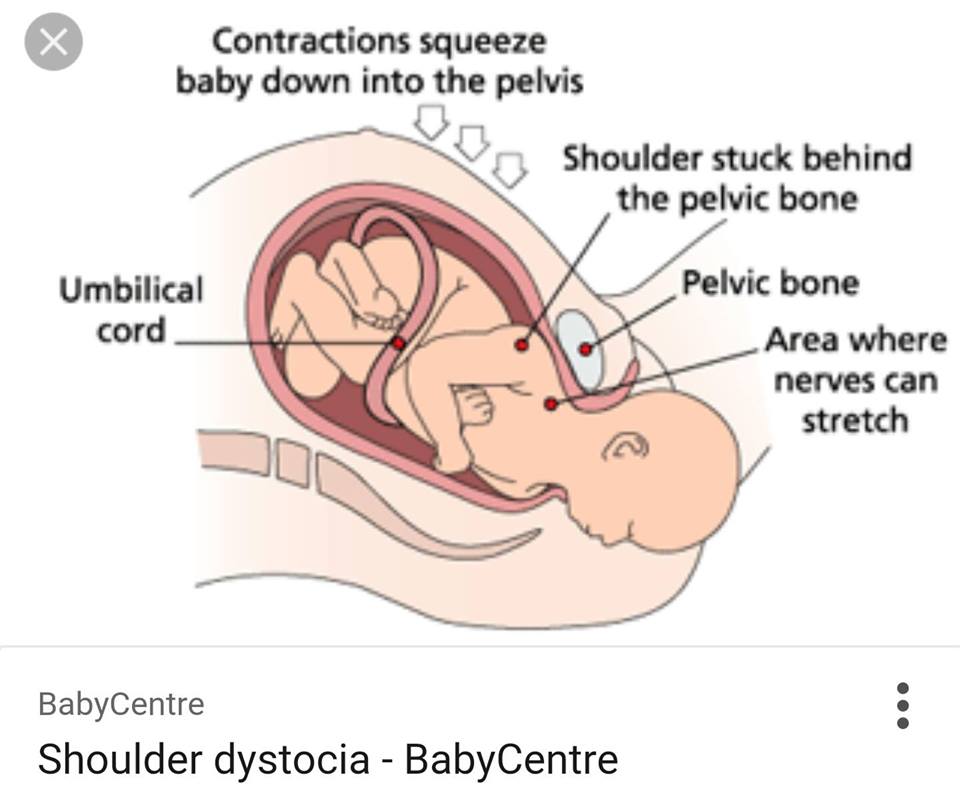

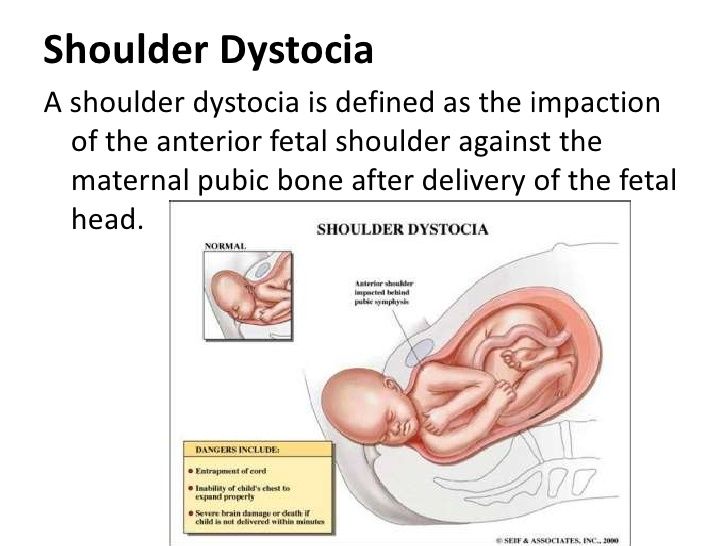

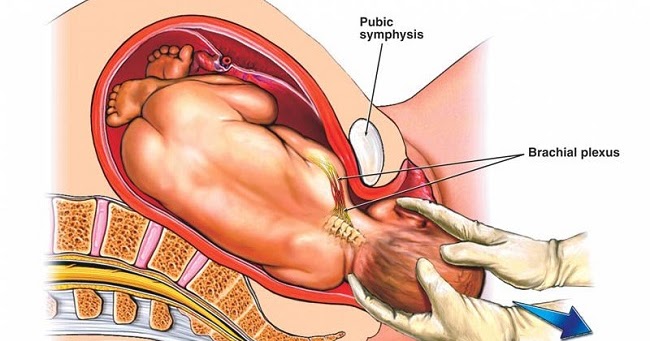

Shoulder dystocia happens when one of the baby’s shoulders gets stuck behind the mother’s pubic bone (the bone behind the pubic hair) or sacrum (the bone at the back of the pelvis, above the tailbone) during birth.

During the second stage of labour, there is normally a pause after the baby’s head has been born but before the body comes out. When shoulder dystocia occurs, this delay is longer delay than normal. The baby will need emergency help to be born.

Shoulder dystocia happens in about 1 in every 200 births. It is more common during a vaginal birth, but a baby’s shoulder can also get stuck during a caesarean.

Shoulder dystocia is a medical emergency. While the baby is stuck, they cannot breathe and the umbilical cord may be squeezed. They will need help to be born quickly so they can get enough oxygen. It can also cause a fracture of the baby’s collarbone or upper arm, nerve damage affecting the shoulders, arms, hands or fingers, brain damage or speech disability. Sadly, there is a risk that lack of oxygen during birth can lead to brain damage or even death.

Sometimes shoulder dystocia can lead to complications for the mother, including tears, a haemorrhage, infection, or damage to the nerves causing incontinence.

These complications are very rare, and doctors and midwives are highly trained to deal with shoulder dystocia if it happens.

Why does shoulder dystocia happen?

Shoulder dystocia can happen during any vaginal birth. It is usually because the baby is too big, because it is in the wrong position, or because the mother is in a position that restricts the room in the pelvis.

It is impossible to predict whether shoulder dystocia will happen, but there are some things that make it more likely, including when you:

- experienced shoulder dystocia during a previous labour

- are having a large baby (called ‘fetal macrosomia’)

- are having twins or multiple babies

- are very overweight

- have diabetes

- have had labour induced, or other interventions are used during labour

Shoulder dystocia can also happen if the labour goes very quickly or very slowly.

What to expect if shoulder dystocia happens

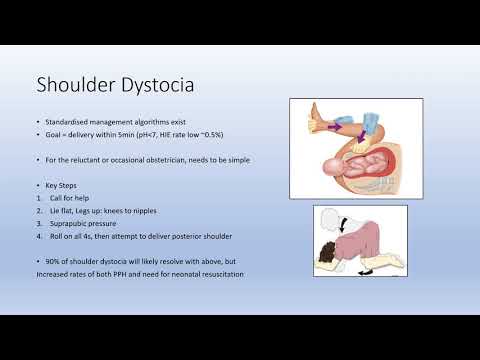

If your doctor or midwife suspects shoulder dystocia, they will first tell you to stop pushing. They will immediately call for help, since you may need other specialist doctors to care for you or the baby.

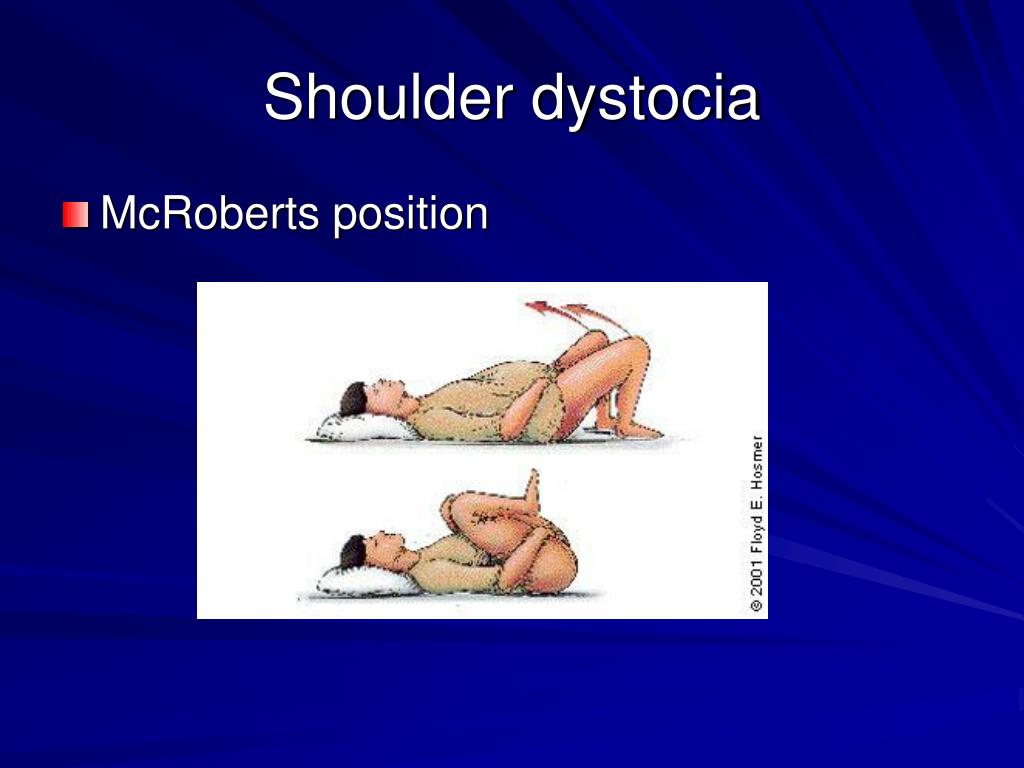

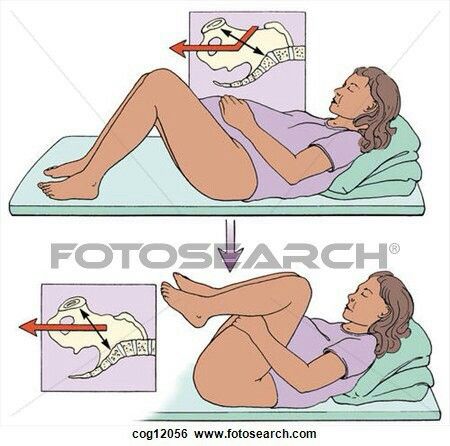

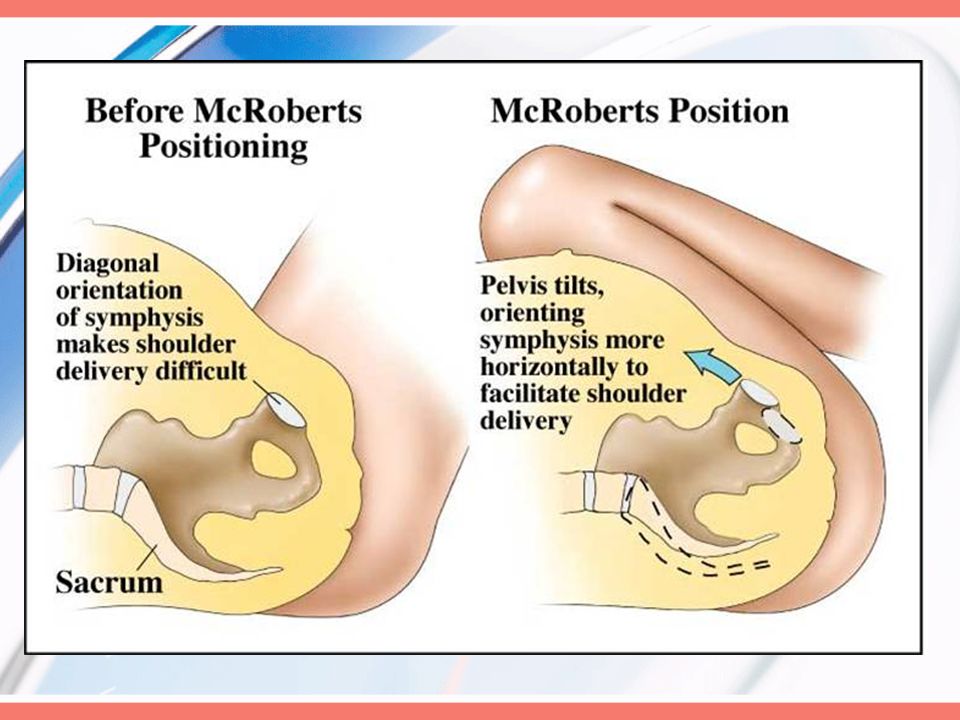

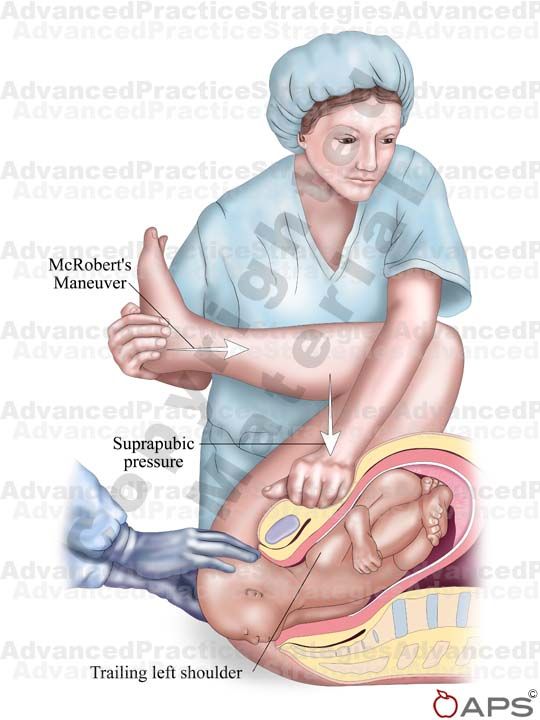

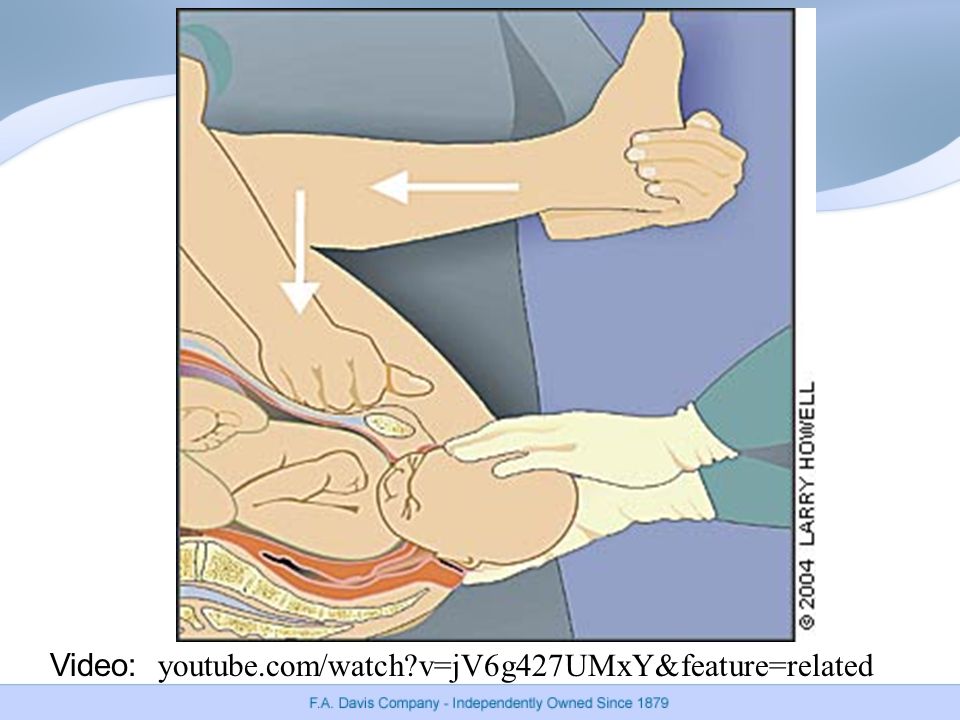

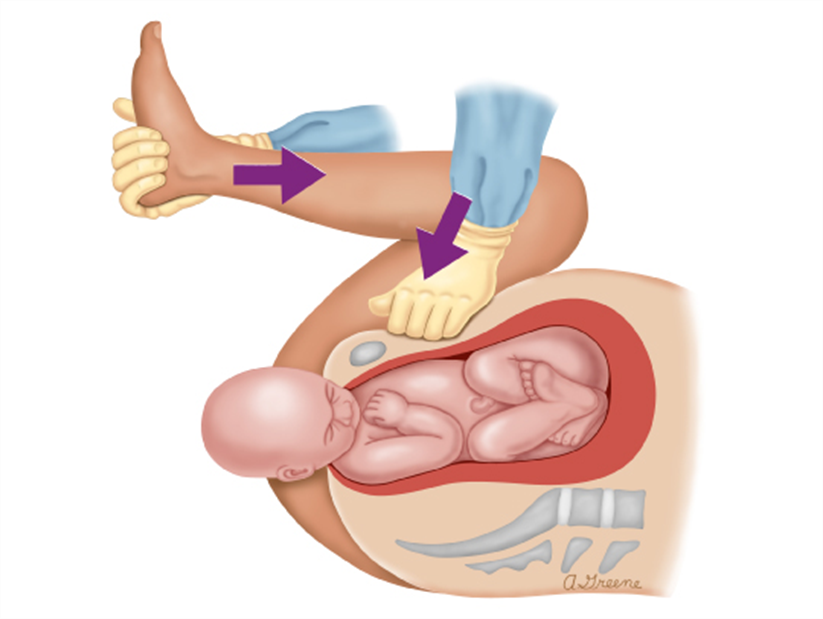

Sometimes, simply changing your position can free the shoulder. You might be asked to lie flat on your back with your knees pulled back as far as they can go. The midwife or doctor will gently press on your tummy to help free the baby’s shoulder. This is called the 'McRoberts manoeuvre'.

This is called the 'McRoberts manoeuvre'.

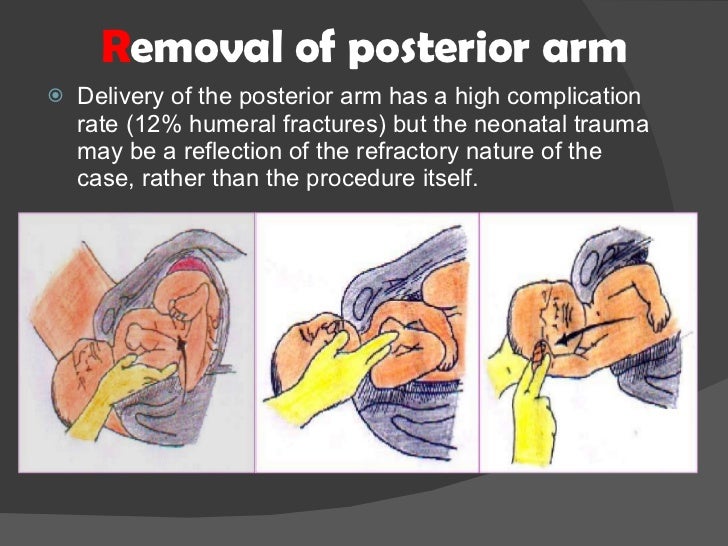

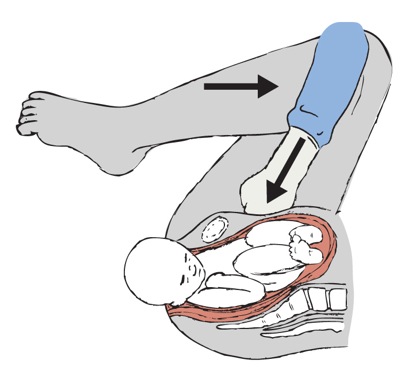

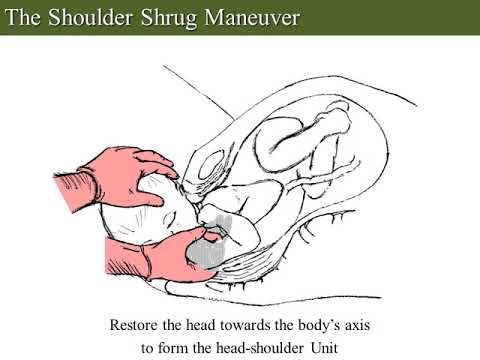

Another position that can work for you to get onto all fours. Sometimes, the midwife or doctor will need to put their hand inside your vagina to free the baby’s body. You will need an episiotomy first.

In very rare cases, the doctor will need to break the baby’s collarbone to get them out. It will heal quickly afterwards. The other option is for you to have a caesarean under general anaesthetic. Once the anaesthetic has taken effect, the baby will be pushed back into your uterus and delivered through your tummy. Both of these options are a last resort.

After the birth

Most babies recover from shoulder dystocia very well. But because they may have been injured or deprived of oxygen, they may need to be watched more closely or spend time in the neonatal intensive care unit. Some babies will need physiotherapy, and you may need help with breastfeeding if your baby has been injured.

If you had a tear or haemorrhage, it will take some time for you to recover. It can also be hard emotionally if you have had a difficult birth. You might feel shocked, guilty or worried about your baby. Midwives, your doctor or a maternal child health nurse can help you deal with these feelings.

It can also be hard emotionally if you have had a difficult birth. You might feel shocked, guilty or worried about your baby. Midwives, your doctor or a maternal child health nurse can help you deal with these feelings.

Your doctor will talk to you about why the shoulder dystocia might have happened. As you are at greater risk of it happening again, they may suggest you consider a planned caesarean next time around.

Preventing shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia is unpredictable so there is very little you can do to prevent it. Managing conditions like diabetes and watching your weight during pregnancy can help. If your baby is big, it may be a good idea to give birth lying on your side or on all fours.

For more information

If you are worried about shoulder dystocia or if you have experienced a difficult birth, call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby on 1800 882 436 to talk to a maternal child health nurse.

Sources:

Mater Mothers’ Hospital (Shoulder dystocia), Journal of Prenatal Medicine (Shoulder dystocia: an Evidence-Based approach), The Royal Women's Hospital (Shoulder Dystocia Guidelines), Elsevier Patient Education (Shoulder dystocia), RANZCOG (Shoulder dystocia)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: March 2021

Back To Top

Related pages

- Interventions during labour

- Giving birth - stages of labour

Need more information?

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

OKNeed further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Shoulder dystocia: an Evidence-Based approach

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Shoulder dystocia. ACOG practice bulletin clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 40, November 2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1045–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Gherman RB, Chauhan S, Ouzounian JG, et al. Shoulder dystocia: the unpreventable obstetric emergency with empiric management guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:657–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shoulder dystocia: the unpreventable obstetric emergency with empiric management guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:657–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. RCOG Guideline No. 42. 2005. Dec.

4. Gherman RB. Shoulder dystocia: prevention and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2005;32:297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Spong CY, Beall M, Rodrigues D, et al. An objective definition of shoulder dystocia: prolonged head-tobody delivery intervals and/or the use of ancillary obstetric maneuvers. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:433–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Amy G. Gottlirb, Henry L. Galan. Shoulder dystocia: an update. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2007:501–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Gherman RB, Ouzounain JG, Goodwin TM. Obstetric maneuvres for shoulder dystocia and associated fetal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1126–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Gherman RB. Shoulder dystocia: an evidencebased evaluation of the obstetric nightmare. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:345–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:345–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Ouzounian JG, Miller DA, Paul RH. Spontaneous vaginal delivery: a risk factor for Erbʼs palsy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:423–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Mavroforou A, Koumantakis E, Michalodimitrakis E. Physiciansʼ liability in obstetric and gynecology practice. Med-Law. 2005;24:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Anthony Noble. Brachial plexus injuries and shoulder dystocia: Medico-legaI commentary and implications. Journal oJ Obstetnʼcs and Gynaecology. 2005 Feb 2005;25(2):105–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Clinical Negligence Sscheme for Trusts. Maternity: Clinical Risk Management Standards. London. NHS LitigationAuthority. 2010 [Google Scholar]

13. Elizabeth G. Baxley, Robert W. Gobbo. Shoulder Dystocia American Family Physician. 2004;69(7):1707–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Mansor A, Arumugam K, Omar SZ. Macrosomia is the only reliable predictor of shoulder dystocia in babies weighing 3. 5 kg or more. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010 Mar;149(1):44–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5 kg or more. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010 Mar;149(1):44–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. D Maticot-Baptista, A Collin, A Martin, R Maillet, D Riethmuller. Prevention of shoulder dystocia by an ultrasound selection at the beginning of labour of foetuses with large abdominal circumference. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2007 Feb 2007;36(1):42–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. E. Verspyck, F. Goffinet, M.F. Hellot, J. Milliez, L. Marpeau. Newborn shoulder width : determinant factors and predictive value for shoulder dystocia. Journal de gynécologie obstétrique et de biologie de la reproduction. 2000;29:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Schild RL, Fimmers R, Hansmann M. Fetal weight estimation by three-dimensional ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16((5)):445–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Fetal macrosomia. ACOG practice bulletin clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 22. Washington, DC. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2000 [Google Scholar]

Number 22. Washington, DC. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2000 [Google Scholar]

19. Rouse DJ, Owen J. Prophylactic caesarean delivery for fetal macrosomia diagnosed by means of ultrasonography-A Faustian bargain? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:332–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Sokol RJ, Blackwell SC. for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 40: shoulder dystocia. November 2002 (replaces practice pattern no. 7, October 1997) Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;80:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Mocanu EV, Greene RA, Byrne BM, Turner MJ. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes of babies weighing more than 4.5 kg: an analysis by parity. . Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;92:229–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Acker D., Sachs B., Friedman E. Risk factors for shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:762–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Dildy GA, Clark SL. Shoulder dystocia: risk identification. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43(2):265–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shoulder dystocia: risk identification. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43(2):265–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Nesbitt TS, Gilbert WM, Herrchen B. Shoulder dystocia and associated risk factors with macrosomic infants born in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(2):476–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. McFarland MB, Tryloich CG, Langer O. Anthropometric differences in macrosomic infants of diabetic and nondiabetic mothers. J Matern Fetal Med. 1998;7(6):292–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, et al. Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in pregnant women (ACHOIS) Trial Group. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2477–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Acker D., Gregory K, Sachs B, Friedman E. Risk factors for Erb-Duchenne Palsy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Bingham J, Chauhan SP, Hayes E, Gherman R, Lewis D. Recurrent shoulder dystocia: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010 Mar;65(3):183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010 Mar;65(3):183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Eva A. Overland, Anny Spydslaug, Christopher S. Nielsen, Anne Eskild. Risk of shoulder dystocia in second delivery: does a history of shoulder dystocia matter? American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009 May;200(5):506.e1–506.e6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Manish Gupta, Christine Hockley, Maria A. Quigley, Peter Yeh, Lawrence Impey. Antenatal and intrapartum prediction of shoulder Dystocia. European. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2010 Aug;151(2):134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. McFarland MB, Langer O, Piper JM, et al. Perinatal outcome and the type and number of maneuvers in shoulder dystocia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;55:219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Souter I, Neumann K, Ouzounian JG, Paul RH. The McRobertʼs maneuver for the alleviation of shoulder dystocia:how successful is it? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;178:656–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. OʼLeary JA. Cephalic replacement for shoulder dystocia: present status and future role of Zavanelli maneuver. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:847–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Goodwin TM, Banks E, Millar LK, et al. Catastrophic shoulder dystocia and emergency symphysiotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(2):463–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Benjamin K. Part 1. Injuries to brachial plexus: mechanisms of injury and identification of risk factors. Adv Neonatal Care. 2005;5(4):181–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Baskett TF, Allen AC. Perinatal implications of shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:14–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Suneet P. Chauhan, Jill Cole, M Ryan Laye, Ken Choi, Maureen Sanderson, R Clifton Moore, Everett Fagann, Holly L King, John C Morrison. Shoulder Dystocia with and without Brachial Plexus Injury: Experience from Three Centers. Am J Perinatol. 2007 Jun;24(6):365–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Doumouchtsis S.K., Arulkumaran S. Are All Brachial Plexus Injuries Caused by Shoulder Dystocia? Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2009 Sep [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Doumouchtsis S.K., Arulkumaran S. Are All Brachial Plexus Injuries Caused by Shoulder Dystocia? Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2009 Sep [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Sandmire HF, DeMott Erb. Erbʼs palsy causation: a historical perspective. Birth. 2003;29:52–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Rouse DJ, Owen J, Goldenberg RL, et al. The effectiveness and costs of elective cesarean delivery for fetal macrosomia diagnosed by ultrasound. JAMA. 1996;276(18):1480–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Associated factors in 1611 cases of brachial plexus injury. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:536–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Graham EM, Forouzan I, Morgan MA. A retrospective analysis of Erbʼs palsy cases and their relation to birth weight and trauma at delivery. J Matern Fetal Med. 1997;6:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Kjos SL, Henry OA, Montoro M, Buchanan TA, Mestman JH. Insulin-requiring diabetes in pregnancy: a randomized trial of active induction of labor and expectant management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:611–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:611–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Herbst MA. Treatment of suspected fetal macrosomia: a cost-effective analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 005;193:1035–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pregestational diabetes mellitus. ACOG practice bulletin clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 60. Washington, DC. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2005 [Google Scholar]

46. Gross TL, Sokol RJ, Williams T, Thompson K. Shoulder dystocia: a fetal-physician risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1408–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Kwek K, Yeo GSH. Shoulder dystocia and injuries: prevention and management. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18:123–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Wood C, Ng KH, Hounslaw D, et al. Timedan important variable in normal delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1973;80:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Stallings SP, Edwards RK, Johnson JWC. Correlation of head-to-body delivery intervals in shoulder dystocia and umbilical artery acidosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:268–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Correlation of head-to-body delivery intervals in shoulder dystocia and umbilical artery acidosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:268–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Allen RH, Rosenbaum TC, Ghidini A, et al. Correlating head-to-body delivery intervals with neonatal depression in vaginal births that result in permanent brachial plexus injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:839–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Focus Group Shoulder Dystocia. In: Confidential Enquiries into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy. Fifth Annual Report. London. Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium. 1998:73–9. [Google Scholar]

52. Gobbo R, Baxley EG. Shoulder Distocia. In: ALSO: advanced life support in obstetrics provider course syllabus. Leawood, Kan American Academy of Family Physicians. 2000.

53. Athukorala C, Middleton P, Crowther CA. Intrapartum interventions for preventing shoulder dystocia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;(4) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Poggi SH, Allen RH, Patel CR, Ghidini A, Pezzullo JC, Spong CY. Randomized trial of McRoberts versus lithotomy positioning to decrease the force that is applied to the fetus during delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:874–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poggi SH, Allen RH, Patel CR, Ghidini A, Pezzullo JC, Spong CY. Randomized trial of McRoberts versus lithotomy positioning to decrease the force that is applied to the fetus during delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:874–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Beall MH, Spong CY, Ross MG. A randomized controlled trial of prophylactic maneuvers to reduce head-to-body delivery time in patients at risk for shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Gross TL, Sokol RJ, Williams T, Thompson K. Shoulder dystocia: a fetal-physician risk. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1408–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Hinshaw K. Shoulder dystocia. In: Johanson R, Cox C, Grady K, Howell C, editors. Managing Obstetric Emergencies and Trauma: The MOET Course Manual. London. RCOG Press. 2003:165–74. [Google Scholar]

58. Gherman RB, Tramont J, Muffley P, et al. Analysis of McRobertsʼ maneuver by x-ray pelvimetry. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:43–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Gonik B, Zhang N, Grimm M. Prediction of brachial plexus stretching during shoulder dystocia using a computer simulation model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gonik B, Zhang N, Grimm M. Prediction of brachial plexus stretching during shoulder dystocia using a computer simulation model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA, Malinow A, et al. Use of McRobertsʼ position during delivery and increase in pushing efficiency. Lancet. 2001;358:470–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Lurie S, Ben-Arie Ben-Arie, Hagay A. The ABC of shoulder dystocia management. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;20:195–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Ginsberg NA, Moisidis C. How to predict recurrent shoulder dystocia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1427–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Rubin A. Management of shoulder dystocia. JAMA. 1964;189:835–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Baxley EG. Shoulder dystocia. ALSOseries. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1707–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Poggi SH, Spong CY, Allen RH. Prioritizing posterior arm delivery during severe shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5):1068–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5):1068–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Thompson KA, Satin AJ, Gherman RB. Spiral fracture of the radius: an unusual case of shoulder dystocia-associated morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:36–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Kovavisarach E. The ʻʻall-foursʼʼ maneuver for the management of shoulder dystocia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(2):153–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. The ʻ4kg and overʼenquiries. In:Confidential En-quiries into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy. SixthAnnual Report. London: Maternal and Child HealthResearch Consortium; 1999. pp. 35–47.

69. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal College of Midwives. Towards Safer Child-birth.Minimum Standards for the Organisation ofLabour Wards: Report of a Joint Working Party. RCOG Press. 1999 [Google Scholar]

70. Black RS, Brocklehurst P. A systematic review of training in acute obstetric emergencies. BJOG. 2003;110:837–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Deering S, Poggi S, Macedonia C, Gherman R, Satin AJ. Improving resident competency in the management of shoulder dystocia with simulation training. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deering S, Poggi S, Macedonia C, Gherman R, Satin AJ. Improving resident competency in the management of shoulder dystocia with simulation training. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Crofts JF, Attilakos G, Read M, Sibanda T, Draycott TJ. Shoulder dystocia training using a new birth training mannequin. BJOG. 2005;112:997–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Possible causes of birth injuries of the brachial plexus » Obstetrics and Gynecology

Purpose of the study. To highlight the literature data describing the causes and mechanism of development of birth damage to the brachial plexus in the absence of such a complication as fetal shoulder dystocia.

Material and methods. Using medical search engines (PubMed, Cochrane, Sage, Wiley Online), 27 literature sources were found and analyzed.

Results. The literature describes a large number of cases of birth paralysis in the absence of risk factors, complications of childbirth, provision of benefits. Possible mechanisms of injury are theoretically substantiated.

Possible mechanisms of injury are theoretically substantiated.

Conclusion. The occurrence of damage to the brachial plexus during childbirth is often not associated with the development of shoulder dystocia and the actions of obstetricians. There are a number of other reasons. The development of damage to the brachial plexus in such cases is excellent in mechanism, the clinical picture can often be different. No correlation with risk factors.

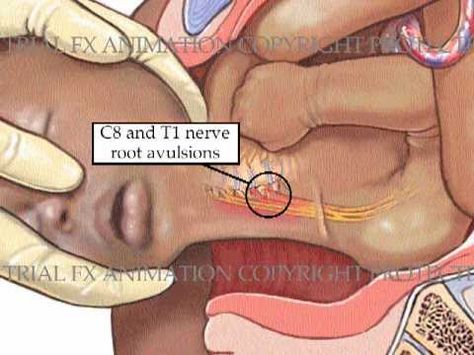

Birth injury of the brachial plexus is a relatively rare injury with serious consequences. The clinical manifestation of this injury is flaccid paralysis of the upper limb. There are Erb-Duchene palsy, in the structure of which there is an upper type of damage (C5-C6) and an average type of damage (C5-C7), Dejerine-Klumpke paralysis (lower type), caused by damage to the C8-Th2 roots of the spinal cord, and total paralysis - damage to C5-Th2 roots.

The incidence of birth injuries of the brachial plexus, according to different authors, ranges from 0. 38 to 5.1 per 1000 newborns [1–7].

38 to 5.1 per 1000 newborns [1–7].

The most common (up to 97%) complication of labor leading to damage to the brachial plexus is fetal shoulder dystocia [8]. With the development of this complication, damage to the brachial plexus occurs in 4–40% of cases [9]. Risk factors are: fetal macrosomia, maternal diabetes mellitus, discrepancy between the size of the fetus and the clinical size of the mother's pelvis [10, 11]. Unfortunately, it is often impossible to prevent the development of shoulder dystocia [9, 12].

The right upper limb is affected more often, which is associated with the biomechanics of labor in the most common (2nd position, anterior view, occipital insertion) position of the fetus [13].

It is generally accepted that traction of the fetus by the head with its deviation away from the axis of the body in conditions of shoulder dystocia leads to damage to the nerves of the brachial plexus. However, the results of studies conducted over the past 25 years indicate that there are a number of other equally significant reasons. Only about 50% of injuries are associated with the development of shoulder dystocia during childbirth [14, 15].

Only about 50% of injuries are associated with the development of shoulder dystocia during childbirth [14, 15].

So, Acker et al. back in 1988, they suggested that in cases of rapid delivery, the rapid advance of the fetus into the small pelvis may be complicated by inadequate rotation of the shoulders (the shoulders of the fetus do not rise into the largest oblique diameter of the pelvis), which, in turn, can lead to damage to the brachial plexus in utero [16]. This point of view is shared by Sandmire and DeMott [17], stating that the incidence of brachial plexus injuries increases by 4.7 times in fast delivery. Alfonso [18] points to the conflict between the fetal posterior shoulder and the mother's sacral promontory as a possible cause of damage to the brachial plexus at the time of the fetus's advance into the small pelvis.

With the accumulation of experience, the fact that brachial plexus injuries during childbirth are not always accompanied by dystocia of the fetal shoulders has become indisputable.

Graham et al. in 1997 conducted a retrospective analysis of 14,358 births from 1987 to 1991 . [19].

Fifteen cases of damage to the brachial plexus during childbirth have been described: 14 of them by vaginal delivery and 1 by caesarean section. Only in 8 (53.3%) cases, the delivery was completed with complications (for example, shoulder dystocia). In this group, the weight of the children was higher than the gestational weight in seven (88%) of the eight newborns, averaging 4265±480 g (3550–5110 g). In the group of children born without complications, birth weight was significantly lower, on average 2906±745 g (1590–3950 g), weight corresponded to gestational age in six (86%) of seven cases. The authors conclude that damage to the brachial plexus is not always associated with a large fetal weight and trauma during childbirth, as previously thought.

Ouzounian et al. in 1997 published the data of their study, which identified four cases of severe damage to the brachial plexus in the absence of shoulder dystocia in labor, as well as four cases of severe damage to the brachial plexus of the posterior fetal handle with the development of anterior shoulder dystocia [20]. The authors conclude that damage to the brachial plexus during childbirth is not in all cases associated with traction.

The authors conclude that damage to the brachial plexus during childbirth is not in all cases associated with traction.

Buljina et al. it was noted that out of 32 children treated for damage to the brachial plexus during childbirth, 8 (22.77%) had no evidence of shoulder dystocia in their anamnesis [21].

Allen and Gurewitsch described a case of damage to the brachial plexus during childbirth in a child whose parents demanded non-intervention of medical personnel in the delivery process. The child was born in cephalic presentation through the birth canal. Traction by the head, vacuum extraction of the fetus was not used. The second period of contractions was 30 minutes. The weight of the fetus corresponded to the gestational age. However, Erb-Duchene paresis was diagnosed on the right (on the side of the posterior handle of the fetus), which resolved on the 4th day of the child's life. The authors conclude that damage to the brachial plexus of the posterior handle of the fetus is also possible during a normally ongoing labor process, natural delivery, in the absence of shoulder dystocia and traction behind the fetal head [22].

Torki et al. report 8 cases of severe damage to the brachial plexus during normal labor [23]. In none of these eight cases, any factors predisposing to the development of damage were identified. Seven out of eight newborns had a normal weight (3514±1043 g). One fetus weighing more than 4800 g on ultrasound (at birth 4940 g) was delivered by caesarean section. In the rest of the cases, children were born through the natural birth canal in cephalic presentation, six - without obstetric assistance (in one case, obstetric forceps were applied). The average duration of the second period of contractions was normal. The observation period for children was 1 month. At the time of the 1st month of life, all had a clinical picture of severe damage to the brachial plexus. The authors conclude that severe brachial plexus injury is possible in the absence of fetal shoulder dystocia and any other predisposing factors.

Gherman et al. in 1998, he conducted a study, the purpose of which was to find out whether the mechanism of development of brachial plexus injuries that arose with shoulder dystocia and in the absence of the latter differ in the mechanism of development. The authors evaluated the consequences of 17 cases of brachial plexus injury not associated with shoulder dystocia and 23 cases associated with dystocia in children aged 1 year. In the group of injuries not associated with dystocia, 7 (41.2%) of 17 children at the time of the 1st year of life had a pattern of persistent paresis, while in the group of injuries associated with dystocia, only 2 (8, 7%) of 23 children. In the first group, improvements came more slowly (6.4±0.9months versus 2.6 ± 0.7 in the second group), fractures of the clavicle were more common (12 out of 17 versus 5 out of 23), the posterior arm of the fetus was more often affected (10 out of 15 versus 4 out of 21). The authors conclude that injuries of the brachial plexus during childbirth that occurred in the absence of shoulder dystocia are a qualitatively different injury than injuries associated with dystocia [24].

The authors evaluated the consequences of 17 cases of brachial plexus injury not associated with shoulder dystocia and 23 cases associated with dystocia in children aged 1 year. In the group of injuries not associated with dystocia, 7 (41.2%) of 17 children at the time of the 1st year of life had a pattern of persistent paresis, while in the group of injuries associated with dystocia, only 2 (8, 7%) of 23 children. In the first group, improvements came more slowly (6.4±0.9months versus 2.6 ± 0.7 in the second group), fractures of the clavicle were more common (12 out of 17 versus 5 out of 23), the posterior arm of the fetus was more often affected (10 out of 15 versus 4 out of 21). The authors conclude that injuries of the brachial plexus during childbirth that occurred in the absence of shoulder dystocia are a qualitatively different injury than injuries associated with dystocia [24].

A similar study was conducted in 2006 by Gurewitsch et al., comparing two similar groups of children with brachial plexus injury. In the group of children with injuries of the brachial plexus in the absence of shoulder dystocia, the posterior arm of the fetus was also more often affected, however, in almost all cases, the picture of paresis was temporary. The authors conclude that injuries of the brachial plexus that are not associated with shoulder dystocia are rare and differ from injuries that occur during the development of dystocia [25].

In the group of children with injuries of the brachial plexus in the absence of shoulder dystocia, the posterior arm of the fetus was also more often affected, however, in almost all cases, the picture of paresis was temporary. The authors conclude that injuries of the brachial plexus that are not associated with shoulder dystocia are rare and differ from injuries that occur during the development of dystocia [25].

Damage to the nerve trunks can also occur with pressure from the pubic symphysis on the shoulder and shoulder girdle of the fetus. Gonik et al. created a mathematical model for calculating the forces exerting pressure on the fetal neck and underlying nerve trunks in the second stage of labor [26, 27]. The authors calculated that the pressure resulting from the traction behind the head was, on average, 22.9 kPa. The pressure resulting from the action of the expelling forces of the uterus varied from 91.1 to 202.5 kPa, that is, it was higher by 4–9once. The authors conclude that the actions of obstetricians are not always the cause of damage to the brachial plexus during childbirth, it may spontaneously occur as a result of the action of endogenous forces (propulsive uterine contractions), which the obstetrician cannot safely control. This view is shared by Sandmire and DeMott [11, 15].

This view is shared by Sandmire and DeMott [11, 15].

It should be noted that, despite the extreme vigilance of obstetrician-gynecologists regarding the prevention of complications in childbirth, the departure from the previously accepted position on fully controlled childbirth, the more frequent use of caesarean section, the incidence of birth damage to the brachial plexus does not tend to decrease. Which, in turn, may indirectly indicate that in many cases the brachial plexus is damaged in utero [23]. Graham et al. give the following data: despite the increase in the frequency of caesarean section in their clinic from 5 to 20%, the incidence of brachial plexus injuries remained the same - 0.12% in the period from 1954 to 1959, 0.10% between 1987 and 1991 [19].

There are a number of other causes of damage to the brachial plexus during childbirth. Disturbed position of the fetus in the uterine cavity, anomalies in the development of the uterus (bicornuate uterus, the presence of an intrauterine septum), cervical ribs, Kaiser Wilhelm syndrome (a consequence of chronic feto-placental insufficiency), osteomyelitis of the proximal shoulder and cervical vertebrae, tumors of the brachial plexus and hemangiomas, congenital varicella -syndrome [18].

The cited literature data indicate that the occurrence of birth injuries of the brachial plexus is often not associated with the development of shoulder dystocia or the actions of obstetricians. There are a number of other reasons. The development of damage to the brachial plexus in such cases is excellent in mechanism, the clinical picture is also different. There is no correlation with risk factors - that is, the occurrence of damage is difficult to predict and take measures to prevent it in advance. Further research is needed to explain the causes of the development of brachial plexus damage during childbirth in the absence of shoulder dystocia in order to improve the system of prevention and care for this group of patients.

Khusainov Nikita Olegovich, post-graduate student of the department of arthrogryposis, FGBU Research Children's Orthopedic Institute named after. G.I. Turner of the Ministry of Health of Russia. Address: 196603, Russia, St. Petersburg, Parkovaya st. 64-68. Phone: 8 (812) 465-28-57, +7 (911) 902-55-34. E-mail: [email protected]

Petersburg, Parkovaya st. 64-68. Phone: 8 (812) 465-28-57, +7 (911) 902-55-34. E-mail: [email protected]

Oreshkov Anatoly Borisovich, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Leading Researcher department of arthrogryposis FGBU Research Children's Orthopedic Institute named after. G.I. Turner of the Ministry of Health of Russia. Address: 196603, Russia, St. Petersburg, Parkovaya st. 64-68. Phone: 8 (812) 465-28-57. E-mail: [email protected]

Obstructed childbirth, description of the disease on the Medihost.ru portal

Obstructed childbirth (or dystocia) is a violation of the birth process caused by anomalies in the development of the fetus or its incorrect presentation, anomalies of the pelvis in the woman in labor or a discrepancy between the size of the fetus and the birth canal.

Obstructed childbirth is a significant problem in obstetrics and gynecology, accounting for about 8% of maternal deaths worldwide¹. Given that 99% of all maternal deaths occur in developing countries², it becomes clear how great the chances of avoiding the death of a mother with high-quality medical support are.

Classification of obstructed labor

Obstructed labor is included in the ICD-10 classification of diseases in three sections at once, which determines their classification. There are the following types of obstructed labor:

- Caused by incorrect presentation or position of the fetus.

- Caused by maternal pelvic abnormalities.

- Other types of obstructed labor (specified and unspecified).

To put it simply, the two main causes of obstructed labor are the incorrect position of the fetus in the uterus and the birth canal that is too narrow (in a certain place or along its entire length). The remaining cases include the full range of possible disorders: fusion or adhesion of twins, tumors, hydrocephalus, etc., but they are extremely rare.

Let's dwell on the more common types of obstructed labor.

Fetal presentation: pathology and normal

Very often, the birth process is hampered by incorrect fetal presentation. Head presentation is considered normal: the position in which the baby's head comes out of the uterus (and out of the vagina) first. However, in some cases, the fetus may not be positioned correctly.

Head presentation is considered normal: the position in which the baby's head comes out of the uterus (and out of the vagina) first. However, in some cases, the fetus may not be positioned correctly.

There are breech, frontal and frontal presentations, as well as shoulder presentation. In the first case, the fetus is turned to the cervix with the buttocks or legs, the facial and frontal presentation suggests an incorrect position of the head, and in the case of the shoulder presentation, the fetus is located in the uterus "across" the birth canal.

All described cases are subject to correction, however, in order to implement it, it is necessary to identify risks in time and prepare for possible difficult childbirth. In this matter, a large degree of responsibility lies with the pregnant woman herself, which does not eliminate the need to improve one's qualifications for a doctor. We will return to risk factors in more detail below.

Causes and consequences of obstructed labor

As already mentioned, obstructed labor is most often caused by incorrect presentation and problematic structure of the woman's pelvis. In critical cases, obstructed labor can result in the death of the fetus or newborn, and even the death of the woman in labor.

In critical cases, obstructed labor can result in the death of the fetus or newborn, and even the death of the woman in labor.

So, for example, in the case of a very large (compared to the pelvis of the woman in labor) fetus, shoulder dystocia is possible - a pathology in which the fetus gets stuck at the exit from the vagina: the child's head is already outside, while the shoulder rests against the pubic bone.

If the pelvis is not wide enough, the fetus may get stuck in the birth canal. If the fetal head rests against the mother's sacrum, serious injuries to his skull are possible.

In the case of a breech presentation, there may be complications caused by the obstetrician's attempt to help the woman in labor and "pull out" the fetus. This type of presentation is also dangerous because it is very difficult for the doctor to make a decision on the need for a caesarean section in time: this question arises at the moment when the fetus has left the uterus to the shoulder girdle, and in most cases (with breech presentation) it is already too late to do a caesarean section .