Can you be born with eczema

Eczema in early life: Genetics, the skin barrier, and lessons learned from birth cohort studies

1. Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008 Apr 3;358(14):1483–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Cork MJ, Robinson DA, Vasilopoulos Y, Ferguson A, Moustafa M, MacGowan A, et al. New perspectives on epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis: gene-environment interactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Jul;118(1):3–21. quiz 2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 May;113(5):832–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Williams H, Flohr C. How epidemiology has challenged 3 prevailing concepts about atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Jul;118(1):209–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson W, Anderson HR. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Apr;121(4):947–54. e15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Strachan D, Sibbald B, Weiland S, Ait-Khaled N, Anabwani G, Anderson HR, et al. Worldwide variations in prevalence of symptoms of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1997 Nov;8(4):161–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Williams HC. Atopic dermatitis—the epidemiology, causes and prevention of atopic eczema. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

8. Shelov SP, Hannemann R, editors. The Complete and Authoritative Guide. 4. New York: NY Bantam Books; 2004. Caring for your baby and young child:brith to age 5. [Google Scholar]

9. Brown S, Reynolds NJ. Atopic and non-atopic eczema. Bmj. 2006 Mar 11;332(7541):584–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Recent insights into atopic dermatitis and implications for management of infectious complications. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Jan;125(1):4–13. quiz 4–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Jan;125(1):4–13. quiz 4–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. 10. Atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Feb;117(2 Suppl Mini-Primer):S475–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Ong PY, Ohtake T, Brandt C, Strickland I, Boguniewicz M, Ganz T, et al. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2002 Oct 10;347(15):1151–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Leung DY. Our evolving understanding of the functional role of filaggrin in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009 Sep;124(3):494–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Matsuoka S, Nakayama R, Nakayama H, Yamashita K, Kuroda Y. Prevalence of specific allergic diseases in school children as related to parental atopy. Pediatrics International. 2002;41(1):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Wadonda-Kabondo N, Sterne JA, Golding J, Kennedy CT, Archer CB, Dunnill MG. Association of parental eczema, hayfever, and asthma with atopic dermatitis in infancy: birth cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2004 Oct;89(10):917–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Dis Child. 2004 Oct;89(10):917–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Larsen FS, Holm NV, Henningsen K. Atopic dermatitis. A genetic-epidemiologic study in a population-based twin sample. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986 Sep;15(3):487–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Schultz Larsen F. Atopic dermatitis: a genetic-epidemiologic study in a population-based twin sample. Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5 part 1):719–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

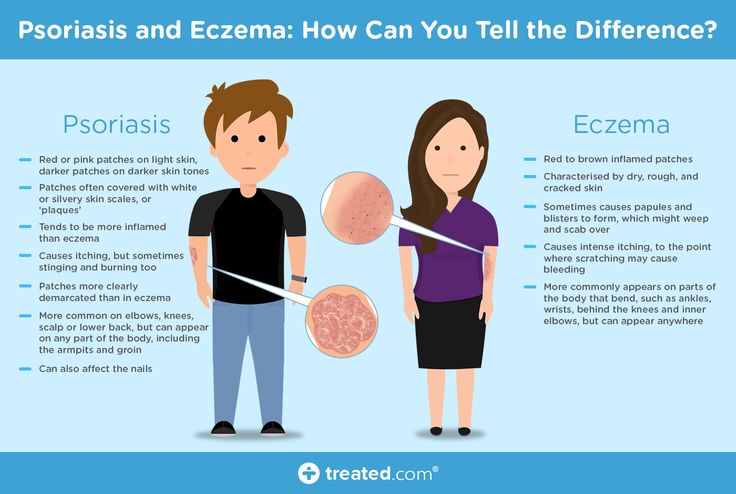

18. Cookson WO, Ubhi B, Lawrence R, Abecasis GR, Walley AJ, Cox HE, et al. Genetic linkage of childhood atopic dermatitis to psoriasis susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2001 Apr;27(4):372–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Lee YA, Wahn U, Kehrt R, Tarani L, Businco L, Gustafsson D, et al. A major susceptibility locus for atopic dermatitis maps to chromosome 3q21. Nat Genet. 2000;26(4):470–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Cookson W. The immunogenetics of asthma and eczema: a new focus on the epithelium. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004 Dec;4(12):978–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004 Dec;4(12):978–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Haagerup A, Bjerke T, Schiotz PO, Dahl R, Binderup HG, Tan Q, et al. Atopic dermatitis -- a total genome-scan for susceptibility genes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84(5):346–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Nomura I, Gao B, Boguniewicz M, Darst MA, Travers JB, Leung DY. Distinct patterns of gene expression in the skin lesions of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: a gene microarray analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003 Dec;112(6):1195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Vickery BP. Skin barrier function in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007 Feb;19(1):89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Brown SJ, Irvine AD. Atopic eczema and the filaggrin story. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008 Jun;27(2):128–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Cork MJ, Danby SG, Vasilopoulos Y, Hadgraft J, Lane ME, Moustafa M, et al. Epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009 Aug;129(8):1892–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Bieber T, Novak N. Pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: new developments. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2009 Jul;9(4):291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bieber T, Novak N. Pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: new developments. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2009 Jul;9(4):291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Barnes KC. An update on the genetics of atopic dermatitis: scratching the surface in 2009. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Jan;125(1):16–29. e1–11. quiz 30–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Greisenegger E, Novak N, Maintz L, Bieber T, Zimprich F, Haubenberger D, et al. Analysis of four prevalent filaggrin mutations (R501X, 2282del4, R2447X and S3247X) in Austrian and German patients with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009 Oct 23; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. McGrath JA, Uitto J. The filaggrin story: novel insights into skin-barrier function and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008 Jan;14(1):20–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Weidinger S, Baurecht H, Wagenpfeil S, Henderson J, Novak N, Sandilands A, et al. Analysis of the individual and aggregate genetic contributions of previously identified serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal type 5 (SPINK5), kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7), and filaggrin (FLG) polymorphisms to eczema risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Sep;122(3):560–8. e4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Sep;122(3):560–8. e4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. McKinley-Grant LJ, Idler WW, Bernstein IA, Parry DA, Cannizzaro L, Croce CM, et al. Characterization of a cDNA clone encoding human filaggrin and localization of the gene to chromosome region 1q21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jul;86(13):4848–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Gan SQ, McBride OW, Idler WW, Markova N, Steinert PM. Organization, structure, and polymorphisms of the human profilaggrin gene. Biochemistry. 1990 Oct 9;29(40):9432–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Smith FJ, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Zhao Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris. Nat Genet. 2006 Mar;38(3):337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006 Apr;38(4):441–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nat Genet. 2006 Apr;38(4):441–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Barker JN, Palmer CN, Zhao Y, Liao H, Hull PR, Lee SP, et al. Null mutations in the filaggrin gene (FLG) determine major susceptibility to early-onset atopic dermatitis that persists into adulthood. J Invest Dermatol. 2007 Mar;127(3):564–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Burgess JA, Lowe AJ, Matheson MC, Varigos G, Abramson MJ, Dharmage SC. Does eczema lead to asthma? J Asthma. 2009 Jun;46(5):429–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Marenholz I, Nickel R, Ruschendorf F, Schulz F, Esparza-Gordillo J, Kerscher T, et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations predispose to phenotypes involved in the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Oct;118(4):866–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Henderson J, Northstone K, Lee SP, Liao H, Zhao Y, Pembrey M, et al. The burden of disease associated with filaggrin mutations: a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Apr;121(4):872–7. e9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

e9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Weidinger S, O’Sullivan M, Illig T, Baurecht H, Depner M, Rodriguez E, et al. Filaggrin mutations, atopic eczema, hay fever, and asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 May;121(5):1203–9. e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Brown SJ, Relton CL, Liao H, Zhao Y, Sandilands A, Wilson IJ, et al. Filaggrin null mutations and childhood atopic eczema: a population-based case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Apr;121(4):940–46. e3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Howell MD, Kim BE, Gao P, Grant AV, Boguniewicz M, Debenedetto A, et al. Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007 Jul;120(1):150–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. O’Regan GM, Sandilands A, McLean WH, Irvine AD. Filaggrin in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009 Sep;124(3 Suppl 2):R2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Walley AJ, Chavanas S, Moffatt MF, Esnouf RM, Ubhi B, Lawrence R, et al. Gene polymorphism in Netherton and common atopic disease. Nat Genet. 2001 Oct;29(2):175–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gene polymorphism in Netherton and common atopic disease. Nat Genet. 2001 Oct;29(2):175–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. O’Regan GM, Sandilands A, McLean WH, Irvine AD. Filaggrin in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Sep 4; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Kato A, Fukai K, Oiso N, Hosomi N, Murakami T, Ishii M. Association of SPINK5 gene polymorphisms with atopic dermatitis in the Japanese population. Br J Dermatol. 2003 Apr;148(4):665–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Kawashima T, Noguchi E, Arinami T, Yamakawa-Kobayashi K, Nakagawa H, Otsuka F, et al. Linkage and association of an interleukin 4 gene polymorphism with atopic dermatitis in Japanese families. J Med Genet. 1998 Jun;35(6):502–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Rafatpanah H, Bennett E, Pravica V, McCoy MJ, David TJ, Hutchinson IV, et al. Association between novel GM-CSF gene polymorphisms and the frequency and severity of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003 Sep;112(3):593–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Kiyohara C, Tanaka K, Miyake Y. Genetic susceptibility to atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2008 Mar;57(1):39–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. He JQ, Chan-Yeung M, Becker AB, Dimich-Ward H, Ferguson AC, Manfreda J, et al. Genetic variants of the IL13 and IL4 genes and atopic diseases in at-risk children. Genes Immun. 2003 Jul;4(5):385–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Sehra S, Yao Y, Howell MD, Nguyen ET, Kansas GS, Leung DY, et al. IL-4 regulates skin homeostasis and the predisposition toward allergic skin inflammation. J Immunol. 2010 Mar 15;184(6):3186–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Howell MD, Gallo RL, Boguniewicz M, Jones JF, Wong C, Streib JE, et al. Cytokine milieu of atopic dermatitis skin subverts the innate immune response to vaccinia virus. Immunity. 2006 Mar;24(3):341–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Kim BE, Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD. Loricrin and involucrin expression is down-regulated by Th3 cytokines through STAT-6. Clin Immunol. 2008 Mar;126(3):332–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Immunol. 2008 Mar;126(3):332–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Tsunemi Y, Saeki H, Nakamura K, Sekiya T, Hirai K, Kakinuma T, et al. Interleukin-13 gene polymorphism G4257A is associated with atopic dermatitis in Japanese patients. J Dermatol Sci. 2002 Nov;30(2):100–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Liu X, Nickel R, Beyer K, Wahn U, Ehrlich E, Freidhoff LR, et al. An IL13 coding region variant is associated with a high total serum IgE level and atopic dermatitis in the German multicenter atopy study (MAS-90) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(1 Pt 1):167–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Hummelshoj T, Bodtger U, Datta P, Malling HJ, Oturai A, Poulsen LK, et al. Association between an interleukin-13 promoter polymorphism and atopy. Eur J Immunogenet. 2003 Oct;30(5):355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Hoffjan S, Ostrovnaja I, Nicolae D, Newman DL, Nicolae R, Gangnon R, et al. Genetic variation in immunoregulatory pathways and atopic phenotypes in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Mar;113(3):511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Mar;113(3):511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Van der Pouw Kraan TCTM, Van der Zee JS, Boeije LCM, de Groot ER, Stapel SO, Aarden LA. The role of IL-13 in IgE synthesis by allergic asthma patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;111(1):129–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Callard RE, Hamvas R, Chatterton C, Blanco C, Pembrey M, Jones R, et al. An interaction between the IL-4Ralpha gene and infection is associated with atopic eczema in young children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002 Jul;32(7):990–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Oiso N, Fukai K, Ishii M. Interleukin 4 receptor alpha chain polymorphism Gln551Arg is associated with adult atopic dermatitis in Japan. Br J Dermatol. 2000 May;142(5):1003–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Hosomi N, Fukai K, Oiso N, Kato A, Ishii M, Kunimoto H, et al. Polymorphisms in the promoter of the interleukin-4 receptor alpha chain gene are associated with atopic dermatitis in Japan. J Invest Dermatol. 2004 Mar;122(3):843–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004 Mar;122(3):843–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Soderhall C, Bradley M, Kockum I, Luthman H, Wahlgren CF, Nordenskjold M. Analysis of association and linkage for the interleukin-4 and interleukin-4 receptor b;alpha; regions in Swedish atopic dermatitis families. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002 Aug;32(8):1199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Novak N, Kruse S, Kraft S, Geiger E, Kluken H, Fimmers R, et al. Dichotomic nature of atopic dermatitis reflected by combined analysis of monocyte immunophenotyping and single nucleotide polymorphisms of the interleukin-4/interleukin-13 receptor gene: the dichotomy of extrinsic and intrinsic atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2002 Oct;119(4):870–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Yamamoto N, Sugiura H, Tanaka K, Uehara M. Heterogeneity of interleukin 5 genetic background in atopic dermatitis patients: significant difference between those with blood eosinophilia and normal eosinophil levels. J Dermatol Sci. 2003 Nov;33(2):121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Saarinen J, Kalkkinen N, Welgus HG, Kovanen PT. Activation of human interstitial procollagenase through direct cleavage of the Leu83-Thr84 bond by mast cell chymase. J Biol Chem. 1994 Jul 8;269(27):18134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saarinen J, Kalkkinen N, Welgus HG, Kovanen PT. Activation of human interstitial procollagenase through direct cleavage of the Leu83-Thr84 bond by mast cell chymase. J Biol Chem. 1994 Jul 8;269(27):18134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Kofford MW, Schwartz LB, Schechter NM, Yager DR, Diegelmann RF, Graham MF. Cleavage of type I procollagen by human mast cell chymase initiates collagen fibril formation and generates a unique carboxyl-terminal propeptide. J Biol Chem. 1997 Mar 14;272(11):7127–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Taipale J, Lohi J, Saarinen J, Kovanen PT, Keski-Oja J. Human mast cell chymase and leukocyte elastase release latent transforming growth factor-beta 1 from the extracellular matrix of cultured human epithelial and endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995 Mar 3;270(9):4689–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Mao XQ, Shirakawa T, Enomoto T, Shimazu S, Dake Y, Kitano H, et al. Association between variants of mast cell chymase gene and serum IgE levels in eczema. Hum Hered. 1998 Jan–Feb;48(1):38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hum Hered. 1998 Jan–Feb;48(1):38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Weidinger S, Rummler L, Klopp N, Wagenpfeil S, Baurecht HJ, Fischer G, et al. Association study of mast cell chymase polymorphisms with atopy. Allergy. 2005 Oct;60(10):1256–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Mao XQ, Shirakawa T, Yoshikawa T, Yoshikawa K, Kawai M, Sasaki S, et al. Association between genetic variants of mast-cell chymase and eczema. Lancet. 1996 Aug 31;348(9027):581–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Kawashima T, Noguchi E, Arinami T, Kobayashi K, Otsuka F, Hamaguchi H. No evidence for an association between a variant of the mast cell chymase gene and atopic dermatitis based on case-control and haplotype-relative-risk analyses. Hum Hered. 1998 Sep–Oct;48(5):271–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Tanaka K, Sugiura H, Uehara M, Sato H, Hashimoto-Tamaoki T, Furuyama J. Association between mast cell chymase genotype and atopic eczema: comparison between patients with atopic eczema alone and those with atopic eczema and atopic respiratory disease. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999 Jun;29(6):800–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Exp Allergy. 1999 Jun;29(6):800–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Badertscher K, Bronnimann M, Karlen S, Braathen LR, Yawalkar N. Mast cell chymase is increased in chronic atopic dermatitis but not in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2005 Apr;296(10):503–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Dobrovolskaia MA, Vogel SN. Toll receptors, CD14, and macrophage activation and deactivation by LPS. Microbes Infect. 2002 Jul;4(9):903–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Wright SD, Ramos RA, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ, Mathison JC. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990 Sep 21;249(4975):1431–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K. Lipopolysaccharide recognition: CD14, TLRs and the LPS-activation cluster. Trends Immunol. 2002 Jun;23(6):301–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Biagini Myers JM, Wang N, Lemasters GK, Bernstein DI, Epstein TG, Lindsey MA, et al. Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Childhood Eczema Development and Allergic Sensitization in the CCAAPS Cohort. J Invest Dermatol. 2009 Sep 17; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Invest Dermatol. 2009 Sep 17; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Lange J, Heinzmann A, Zehle C, Kopp M. CT genotype of promotor polymorphism C159T in the CD14 gene is associated with lower prevalence of atopic dermatitis and lower IL-13 production. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005 Aug;16(5):456–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Gern JE, Reardon CL, Hoffjan S, Nicolae D, Li Z, Roberg KA, et al. Effects of dog ownership and genotype on immune development and atopy in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Feb;113(2):307–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Litonjua AA, Belanger K, Celedon JC, Milton DK, Bracken MB, Kraft P, et al. Polymorphisms in the 5′ region of the CD14 gene are associated with eczema in young children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 May;115(5):1056–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Sugarman JL. The epidermal barrier in atopic dermatitis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008 Jun;27(2):108–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Cork M. The importance of skin barrier function. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 1997;8(S1):S7–S13. [Google Scholar]

Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 1997;8(S1):S7–S13. [Google Scholar]

82. Ong PY, Leung DY. Immune dysregulation in atopic dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2006 Sep;6(5):384–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;92( suppl):44–7. [Google Scholar]

84. Gupta J, Grube E, Ericksen MB, Stevenson MD, Lucky AW, Sheth AP, et al. Intrinsically defective skin barrier function in children with atopic dermatitis correlates with disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Mar;121(3):725–30. e2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Nemoto-Hasebe I, Akiyama M, Nomura T, Sandilands A, McLean WH, Shimizu H. Clinical severity correlates with impaired barrier in filaggrin-related eczema. J Invest Dermatol. 2009 Mar;129(3):682–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Hudson TJ. Skin barrier function and allergic risk. Nat Genet. 2006 Apr;38(4):399–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Braff MH, Gallo RL. Antimicrobial peptides: an essential component of the skin defensive barrier. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;306:91–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Antimicrobial peptides: an essential component of the skin defensive barrier. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;306:91–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. McGirt LY, Beck LA. Innate immune defects in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Jul;118(1):202–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Wahn U. The Allergic March. World Allergy Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

90. Kramer U, Lemmen CH, Behrendt H, Link E, Schafer T, Gostomzyk J, et al. The effect of environmental tobacco smoke on eczema and allergic sensitization in children. Br J Dermatol. 2004 Jan;150(1):111–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Schafer T, Dirschedl P, Kunz B, Ring J, Uberla K. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and lactation increases the risk for atopic eczema in the offspring. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997 Apr;36(4):550–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Wang IJ, Hsieh WS, Wu KY, Guo YL, Hwang YH, Jee SH, et al. Effect of gestational smoke exposure on atopic dermatitis in the offspring. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008 Nov;19(7):580–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008 Nov;19(7):580–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Miyake Y, Ohya Y, Tanaka K, Yokoyama T, Sasaki S, Fukushima W, et al. Home environment and suspected atopic eczema in Japanese infants: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007 Aug;18(5):425–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Magnusson LL, Olesen AB, Wennborg H, Olsen J. Wheezing, asthma, hayfever, and atopic eczema in childhood following exposure to tobacco smoke in fetal life. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005 Dec;35(12):1550–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Noakes P, Taylor A, Hale J, Breckler L, Richmond P, Devadason SG, et al. The effects of maternal smoking on early mucosal immunity and sensitization at 12 months of age. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007 Mar;18(2):118–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Muizzuddin N, Marenus K, Vallon P, Maes D. Effect of cigarette smoke on skin. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1997;48(5):235–42. [Google Scholar]

97. Mimura J, Yamashita K, Nakamura K, Morita M, Takagi TN, Nakao K, et al. Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells. 1997 Oct;2(10):645–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells. 1997 Oct;2(10):645–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Tauchi M, Hida A, Negishi T, Katsuoka F, Noda S, Mimura J, et al. Constitutive expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in keratinocytes causes inflammatory skin lesions. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Nov;25(21):9360–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Flohr C, Pascoe D, Williams HC. Atopic dermatitis and the ‘hygiene hypothesis’: too clean to be true? Br J Dermatol. 2005 Feb;152(2):202–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. McNally NJ, Williams HC, Phillips DR, Strachan DP. Is there a geographical variation in eczema prevalence in the UK? Evidence from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study. Br J Dermatol. 2000 Apr;142(4):712–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smith C, Collins J, Heatlie H, Frischer M, et al. Siblings, multiple births, and the incidence of allergic disease: a birth cohort study using the West Midlands general practice research database. Thorax. 2001 Oct;56(10):758–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thorax. 2001 Oct;56(10):758–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Karmaus W, Botezan C. Does a higher number of siblings protect against the development of allergy and asthma? A review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002 Mar;56(3):209–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Williams HC, Strachan DP, Hay RJ. Childhood eczema: disease of the advantaged? Bmj. 1994 Apr 30;308(6937):1132–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. Bmj. 1989 Nov 18;299(6710):1259–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Loza MJ, Peters SP, Penn RB. Atopy, asthma, and experimental approaches based on the linear model of T cell maturation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005 Jan;35(1):8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Langan SM, Flohr C, Williams HC. The role of furry pets in eczema: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2007 Dec;143(12):1570–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Wang M, Karlsson C, Olsson C, Adlerberth I, Wold AE, Strachan DP, et al. Reduced diversity in the early fecal microbiota of infants with atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Jan;121(1):129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reduced diversity in the early fecal microbiota of infants with atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Jan;121(1):129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Bjorksten B, Sepp E, Julge K, Voor T, Mikelsaar M. Allergy development and the intestinal microflora during the first year of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001 Oct;108(4):516–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Kalliomaki M, Kirjavainen P, Eerola E, Kero P, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Distinct patterns of neonatal gut microflora in infants in whom atopy was and was not developing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001 Jan;107(1):129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Penders J, Thijs C, van den Brandt PA, Kummeling I, Snijders B, Stelma F, et al. Gut microbiota composition and development of atopic manifestations in infancy: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Gut. 2007 May;56(5):661–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Kulig M, Bergmann R, Klettke U, Wahn V, Tacke U, Wahn U. Natural course of sensitization to food and inhalant allergens during the first 6 years of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999 Jun;103(6):1173–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999 Jun;103(6):1173–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Lau S, Nickel R, Niggemann B, Gruber C, Sommerfeld C, Illi S, et al. The development of childhood asthma: lessons from the German Multicentre Allergy Study (MAS) Paediatr Respir Rev. 2002 Sep;3(3):265–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Ohshima Y, Yamada A, Hiraoka M, Katamura K, Ito S, Hirao T, et al. Early sensitization to house dust mite is a major risk factor for subsequent development of bronchial asthma in Japanese infants with atopic dermatitis: results of a 4-year followup study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002 Sep;89(3):265–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. van der Hulst AE, Klip H, Brand PLP. Risk of developing asthma in young children with atopic eczema: A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(3):565–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Host A, Halken S, Jacobsen HP, Christensen AE, Herskind AM, Plesner K. Clinical course of cow’s milk protein allergy/intolerance and atopic diseases in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13( Suppl 15):23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13( Suppl 15):23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Golding J. The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)--study design and collaborative opportunities. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004 Nov;151( Suppl 3):U119–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Pembrey M. The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC): a resource for genetic epidemiology. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004 Nov;151( Suppl 3):U125–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Emenius G, Pershagen G, Berglind N, Kwon HJ, Lewne M, Nordvall SL, et al. NO2, as a marker of air pollution, and recurrent wheezing in children: a nested case-control study within the BAMSE birth cohort. Occup Environ Med. 2003 Nov;60(11):876–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Mai XM, Neuman A, Ostblom E, Pershagen G, Nordvall L, Almqvist C, et al. Symptoms to pollen and fruits early in life and allergic disease at 4 years of age. Allergy. 2008 Nov;63(11):1499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

120. Wickman M, Kull I, Pershagen G, Nordvall SL. The BAMSE project: presentation of a prospective longitudinal birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13( Suppl 15):11–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wickman M, Kull I, Pershagen G, Nordvall SL. The BAMSE project: presentation of a prospective longitudinal birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13( Suppl 15):11–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Kull I, Bohme M, Wahlgren CF, Nordvall L, Pershagen G, Wickman M. Breast-feeding reduces the risk for childhood eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 Sep;116(3):657–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. Mai XM, Almqvist C, Nilsson L, Wickman M. Birth anthropometric measures, body mass index and allergic diseases in a birth cohort study (BAMSE) Arch Dis Child. 2007 Oct;92(10):881–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Arshad SH, Hide DW. Effect of environmental factors on the development of allergic disorders in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992 Aug;90(2):235–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Wijga A, Smit HA, Brunekreef B, Gerritsen J, Kerkhof M, Koopman LP, et al. Are children at high familial risk of developing allergy born into a low risk environment? The PIAMA Birth Cohort Study. Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001 Apr;31(4):576–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001 Apr;31(4):576–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Lodrup Carlsen KC. The environment and childhood asthma (ECA) study in Oslo: ECA-1 and ECA-2. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13( Suppl 15):29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Laubereau B, Brockow I, Zirngibl A, Koletzko S, Gruebl A, von Berg A, et al. Effect of breast-feeding on the development of atopic dermatitis during the first 3 years of life--results from the GINI-birth cohort study. J Pediatr. 2004 May;144(5):602–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127. Heinrich J, Bolte G, Holscher B, Douwes J, Lehmann I, Fahlbusch B, et al. Allergens and endotoxin on mothers’ mattresses and total immunoglobulin E in cord blood of neonates. Eur Respir J. 2002 Sep;20(3):617–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

128. Devereux G, Barker RN, Seaton A. Antenatal determinants of neonatal immune responses to allergens. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002 Jan;32(1):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

129. Kurukulaaratchy R, Fenn M, Matthews S, Hasan Arshad S. The prevalence, characteristics of and early life risk factors for eczema in 10-year-old children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003 Jun;14(3):178–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kurukulaaratchy R, Fenn M, Matthews S, Hasan Arshad S. The prevalence, characteristics of and early life risk factors for eczema in 10-year-old children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003 Jun;14(3):178–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

130. Kerkhof M, Koopman LP, van Strien RT, Wijga A, Smit HA, Aalberse RC, et al. Risk factors for atopic dermatitis in infants at high risk of allergy: the PIAMA study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003 Oct;33(10):1336–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

131. Brockow I, Zutavern A, Hoffmann U, Grubl A, von Berg A, Koletzko S, et al. Early allergic sensitizations and their relevance to atopic diseases in children aged 6 years: results of the GINI study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19(3):180–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

132. Filipiak B, Zutavern A, Koletzko S, von Berg A, Brockow I, Grubl A, et al. Solid food introduction in relation to eczema: results from a four-year prospective birth cohort study. J Pediatr. 2007 Oct;151(4):352–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

133. Morgenstern V, Zutavern A, Cyrys J, Brockow I, Koletzko S, Kramer U, et al. Atopic diseases, allergic sensitization, and exposure to traffic-related air pollution in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Jun 15;177(12):1331–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Morgenstern V, Zutavern A, Cyrys J, Brockow I, Koletzko S, Kramer U, et al. Atopic diseases, allergic sensitization, and exposure to traffic-related air pollution in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Jun 15;177(12):1331–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134. Sausenthaler S, Kompauer I, Borte M, Herbarth O, Schaaf B, Berg A, et al. Margarine and butter consumption, eczema and allergic sensitization in children. The LISA birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006 Mar;17(2):85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

135. Bockelbrink A, Heinrich J, Schafer I, Zutavern A, Borte M, Herbarth O, et al. Atopic eczema in children: another harmful sequel of divorce. Allergy. 2006 Dec;61(12):1397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

136. Martindale S, McNeill G, Devereux G, Campbell D, Russell G, Seaton A. Antioxidant intake in pregnancy in relation to wheeze and eczema in the first two years of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Jan 15;171(2):121–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

137. Seaton A, Godden DJ, Brown K. Increase in asthma: a more toxic environment or a more susceptible population? Thorax. 1994 Feb;49(2):171–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seaton A, Godden DJ, Brown K. Increase in asthma: a more toxic environment or a more susceptible population? Thorax. 1994 Feb;49(2):171–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

138. Nickel R, Lau S, Niggemann B, Gruber C, von Mutius E, Illi S, et al. Messages from the German Multicentre Allergy Study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13( Suppl 15):7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

139. Bergmann RL, Bergmann KE, Lau-Schadensdorf S, Luck W, Dannemann A, Bauer CP, et al. Atopic diseases in infancy. The German multicenter atopy study (MAS-90) Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1994;5(6 Suppl):19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

140. Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Gruber C, Niggemann B, et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 May;113(5):925–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

141. von Mutius E. The “Atopic March”: MAS study. Revue Française d’Allergologie et d’Immunologie Clinique. 2003;43(7):427–30. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

142. Bufford JD, Reardon CL, Li Z, Roberg KA, Dasilva D, Eggleston PA, et al. Effects of dog ownership in early childhood on immune development and atopic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008 Aug 12; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

143. Lemanske RF., Jr The childhood origins of asthma (COAST) study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13( Suppl 15):38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

144. Singh A, Gangnon R, Evans M, Roberg KA, Tisler C, Da Silva DF, et al. Risk factors for the persistent expression of atopic dermatitis in a high risk birth cohort [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):S178. [Google Scholar]

145. Shanovich KM, Evans MD, Tisler CJ, Roberg KA, Anderson EL, Pappas TE, et al. The Amount of Food-Specific IgE at Age 1 Year is Associated with the Risk of Asthma at Age 6 Years [abstract] The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2008;121(2):S238. [Google Scholar]

146. Tisler CJ, Roberg KA, Anderson EL, Salazar LE, Grabher RA, DaSilva DF, et al. Asthma at Age 6 is Associated with an Early and Variable Pattern of Allergic Sensitization in Childhood [abstract] The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;119(1):S69. [Google Scholar]

Asthma at Age 6 is Associated with an Early and Variable Pattern of Allergic Sensitization in Childhood [abstract] The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;119(1):S69. [Google Scholar]

147. Virnig CM, Roberg K, Anderson E, Salazar LEP, Grabher RA, Tisler C, et al. Allergen Sensitization as a Predictor of Wheezing Phenotype at Age Six Years [abstract] The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;119(1):S69. [Google Scholar]

148. LeMasters GK, Wilson K, Levin L, Biagini J, Ryan P, Lockey JE, et al. High prevalence of aeroallergen sensitization among infants of atopic parents. J Pediatr. 2006 Oct;149(4):505–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

149. Schroer KT, Biagini Myers JM, Ryan PH, Lemasters GK, Bernstein DI, Villareal M, et al. Associations between Multiple Environmental Exposures and Glutathione S-transferase P1 on Persistent Wheezing in a Birth Cohort. J Pediatr. 2008 Oct 23; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

150. Gern JE, Visness CM, Gergen PJ, Wood RA, Bloomberg GR, O’Connor GT, et al. The Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) birth cohort study: design, methods, and study population. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) birth cohort study: design, methods, and study population. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Can you get eczema as an adult?

Diseases & conditions

- Coronavirus Resource Center

- Acne

- Eczema

- Hair loss

- Psoriasis

- Rosacea

- Skin cancer

- A to Z diseases

- A to Z videos

- DIY acne treatment

- How dermatologists treat

- Skin care: Acne-prone skin

- Causes

- Is it really acne?

- Types & treatments

- Childhood eczema

- Adult eczema

- Insider secrets

- Types of hair loss

- Treatment for hair loss

- Causes of hair loss

- Hair care matters

- Insider secrets

- What is psoriasis

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Skin, hair & nail care

- Triggers

- Insider secrets

- What is rosacea

- Treatment

- Skin care & triggers

- Insider secrets

- Types and treatment

- Find skin cancer

- Prevent skin cancer

- Raise awareness

- Español

Featured

How Natalie cleared her adult acneNatalie tried many acne products without success. Find out how a board-certified dermatologist helped Natalie see clear skin before her wedding.

Find out how a board-certified dermatologist helped Natalie see clear skin before her wedding.

This contagious skin disease will usually clear on its own, but sometimes dermatologists recommend treating it. Find out when.

Everyday care

- Skin care basics

- Skin care secrets

- Injured skin

- Itchy skin

- Sun protection

- Hair & scalp care

- Nail care secrets

- Basic skin care

- Dry, oily skin

- Hair removal

- Tattoos and piercings

- Anti-aging skin care

- For your face

- For your skin routine

- Preventing skin problems

- Bites & stings

- Burns, cuts, & other wounds

- Itch relief

- Poison ivy, oak & sumac

- Rashes

- Shade, clothing, and sunscreen

- Sun damage and your skin

- Aprenda a proteger su piel del sol

- Your hair

- Your scalp

- Nail care basics

- Manicures & pedicures

Featured

Practice Safe SunEveryone's at risk for skin cancer. These dermatologists' tips tell you how to protect your skin.

These dermatologists' tips tell you how to protect your skin.

Find out what may be causing the itch and what can bring relief.

Darker Skin Tones

- Skin care secrets

- Hair care

- Hair loss

- Diseases & Conditions

- Acne

- Dark spots

- Dry skin

- Light spots

- Razor bumps

- Caring for Black hair

- Scalp psoriasis

- Weaves & extensions

- Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia

- Frontal fibrosing alopecia

- Hairstyles that pull can cause hair loss

- Acanthosis nigricans

- Acne keloidalis nuchae

- Hidradenitis suppurativa

- Keloid scars

- Lupus and your skin

- Sarcoidosis and your skin

- Skin cancer

- Vitiligo

- More diseases & conditions

Featured

Fade dark spotsFind out why dark spots appear and what can fade them.

If you have what feels like razor bumps or acne on the back of your neck or scalp, you may have acne keloidalis nuchae. Find out what can help.

Cosmetic treatments

- Your safety

- Age spots & dark marks

- Cellulite & fat removal

- Hair removal

- Scars & stretch marks

- Wrinkles

- Younger-looking skin

Featured

Laser hair removalYou can expect permanent results in all but one area. Do you know which one?

Do you know which one?

If you want to diminish a noticeable scar, know these 10 things before having laser treatment.

BotoxIt can smooth out deep wrinkles and lines, but the results aren’t permanent. Here’s how long botox tends to last.

Public health programs

- Skin cancer awareness

- Free skin cancer screenings

- Kids' camp

- Good Skin Knowledge

- Shade Structure grants

- Skin Cancer, Take a Hike!™

- Awareness campaigns

- Flyers & posters

- Get involved

- Lesson plans and activities

- Community grants

Featured

Free materials to help raise skin cancer awarenessUse these professionally produced online infographics, posters, and videos to help others find and prevent skin cancer.

Free to everyone, these materials teach young people about common skin conditions, which can prevent misunderstanding and bullying.

Find a dermatologist

- Find a dermatologist

- What is a dermatologist?

- FAAD: What it means

- How to select a dermatologist

- Telemedicine appointments

- Prior authorization

- Dermatologists team up to improve patient care

Featured

Find a DermatologistYou can search by location, condition, and procedure to find the dermatologist that’s right for you.

A dermatologist is a medical doctor who specializes in treating the skin, hair, and nails. Dermatologists care for people of all ages.

90,000 is useful to know about eczema (EKSEM) It is useful to know about eczema ( EKSEM)

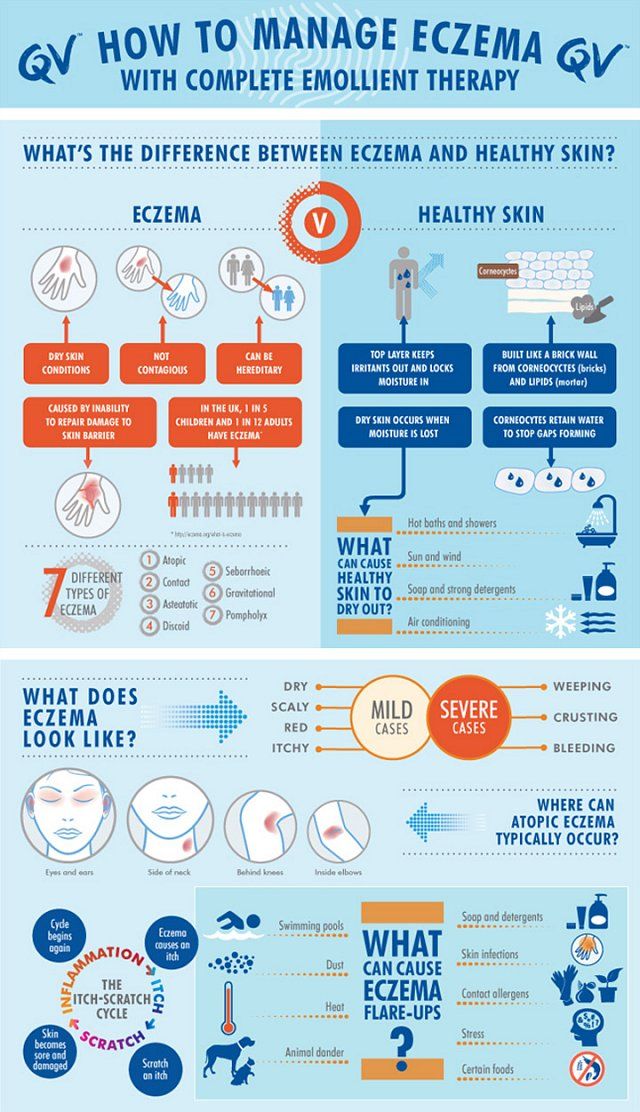

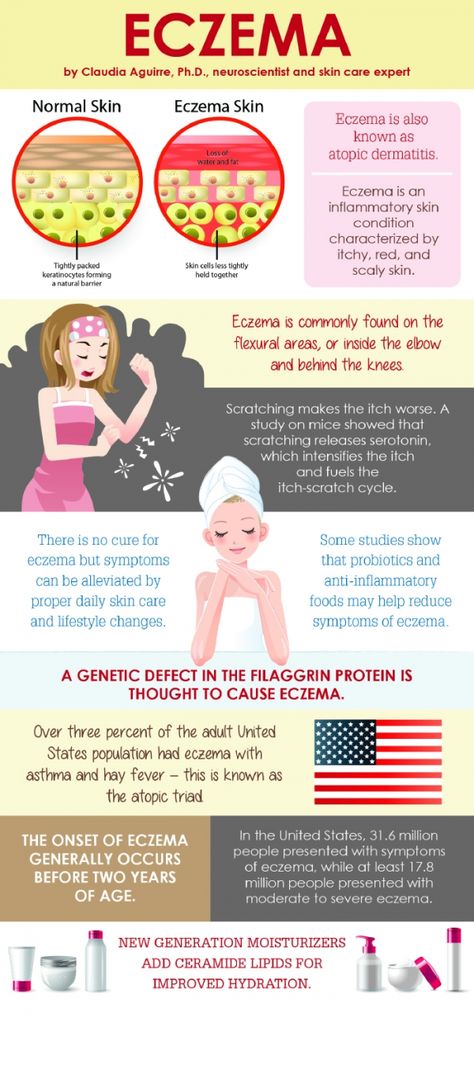

What is eczema?

Eczema is a general name for various skin diseases accompanied by itching. The most common forms of eczema are atopic, occupational (contact), seborrheic, and childhood. Atopy means "difference". In this case, it refers to differences in skin properties and describes hereditary allergic eczema. nine0010

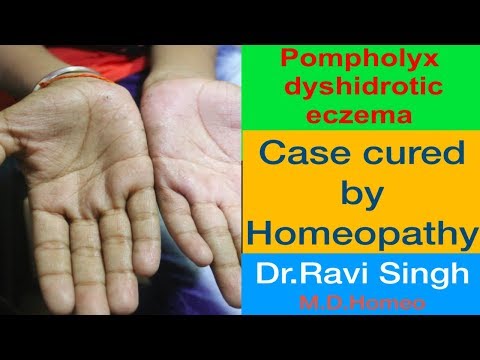

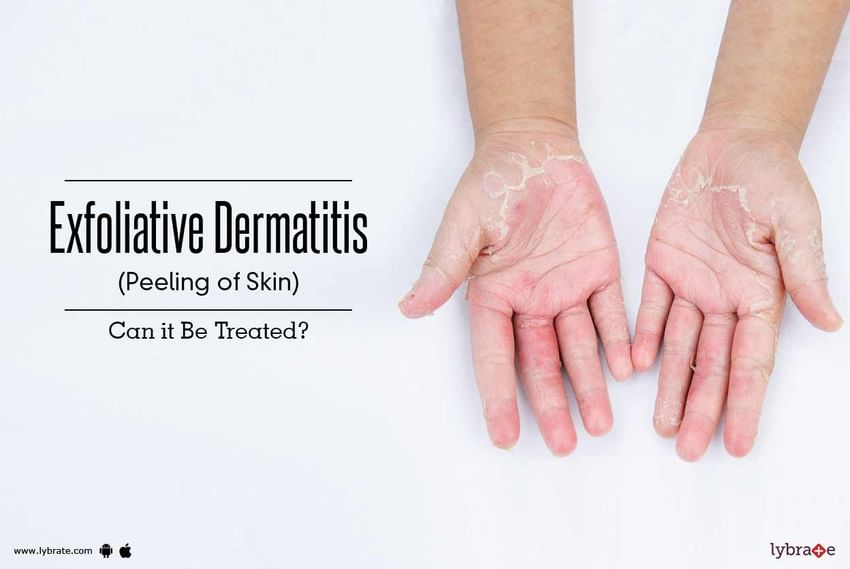

Eczema may be chronic ie. with a prolonged, or acute form of the course of the disease and in most cases is characterized by improvement in the summer and deterioration in winter. The chronic form is characterized by the appearance of a rash with itching. The result of scratching is often the formation of thickened areas of the skin that crack easily. Acute eczema is characterized by itching, redness and swelling of the skin with the possible formation of watery blisters.

The chronic form is characterized by the appearance of a rash with itching. The result of scratching is often the formation of thickened areas of the skin that crack easily. Acute eczema is characterized by itching, redness and swelling of the skin with the possible formation of watery blisters.

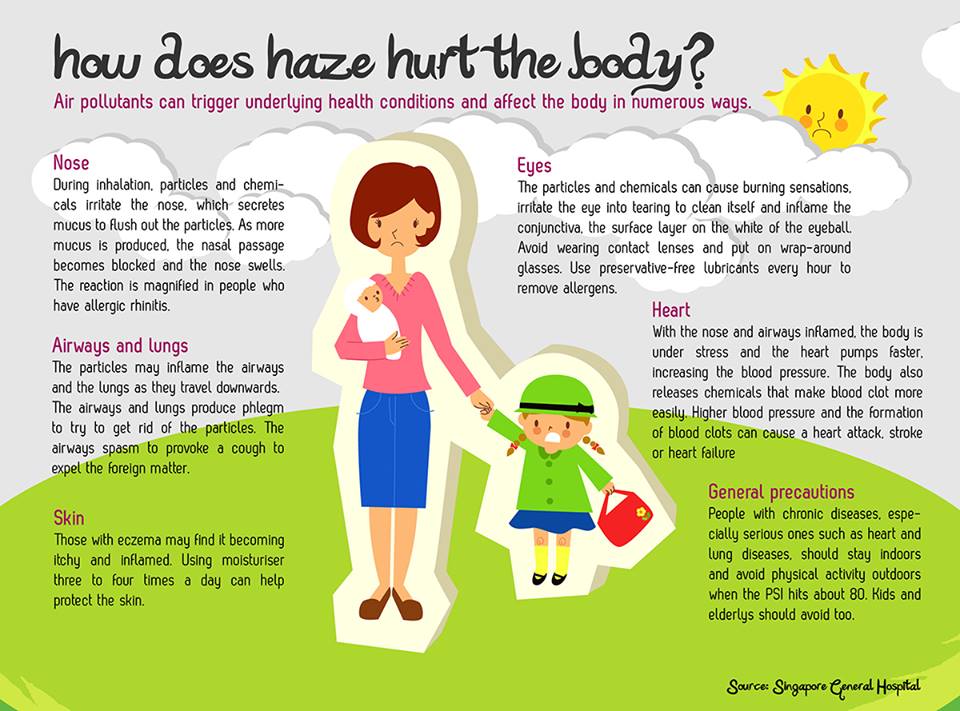

In eczema, there is a deterioration in the body's defense against infections, which easily leads to infectious inflammation, which can lead to a worsening of eczema.

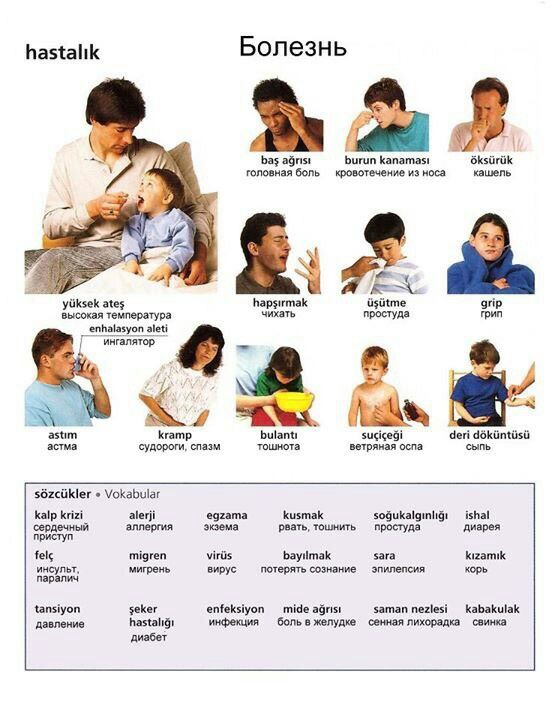

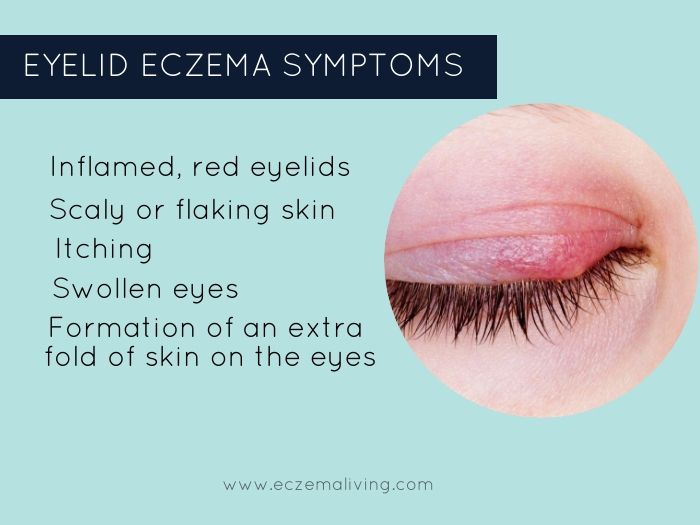

Symptoms of eczema

Atopic eczema results in itchy, dry skin.

New or recurrent contact eczema is characterized by itching, redness and swelling of the skin with the formation of small and large blisters, as well as wet sores in places of direct exposure to the allergen. With prolonged contact eczema, the skin becomes increasingly dry and cracked. Severe itching is common. In the initial stage, eczema is observed only on the area of \u200b\u200bthe skin that was exposed to the allergen, but then the rash can spread to other areas. nine0010

nine0010

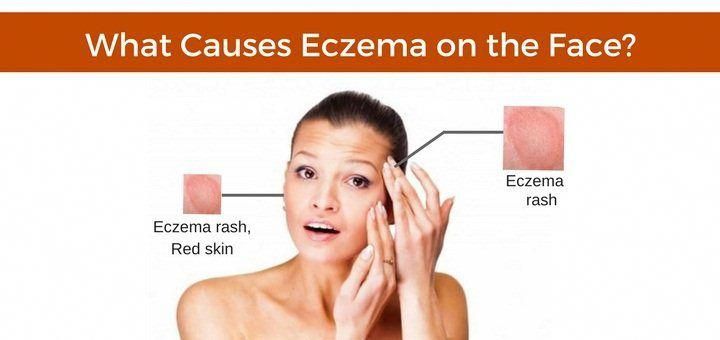

With seborrheic eczema in infants, there is the formation of areas with oily, red skin, covered with oily crusts, on the forehead, head, face, as well as in the folds of the skin on the neck and in the perineum. In adults, it appears as scaly, red, oily skin on the central areas of the face, on the head, behind the ears, and on the chest.

Baby eczema is accompanied by the formation of red, smooth, sometimes wet areas of the skin in diaper wear areas. nine0010

Who can get eczema?

Atopic eczema primarily affects young children. It is estimated that about 15% of Norwegian children suffer from eczema. Often the disease occurs in children in the first months of life, in 60% of them it disappears by the age of four. However, recurrence of the disease may occur in adolescence or adulthood.

Contact eczema is uncommon in young children, but it has become more common since school age. Ear piercings, body piercings and base metal contact with the skin are responsible for a significant increase in nickel contact allergies. Getting a tattoo can lead to allergic contact eczema, which can occur weeks or even months after getting a tattoo. Hair coloring is also an increasingly common cause of eczema, especially as more and more young people dye their hair. nine0010

Getting a tattoo can lead to allergic contact eczema, which can occur weeks or even months after getting a tattoo. Hair coloring is also an increasingly common cause of eczema, especially as more and more young people dye their hair. nine0010

Seborrheic eczema is relatively common. Eczema can appear as early as the first months of life, but usually occurs in adults.

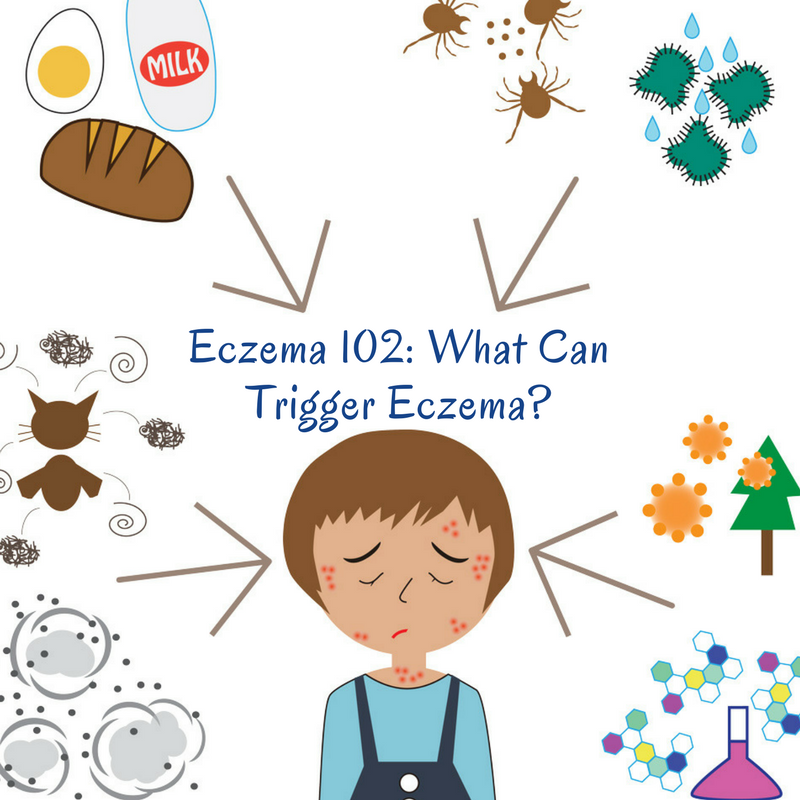

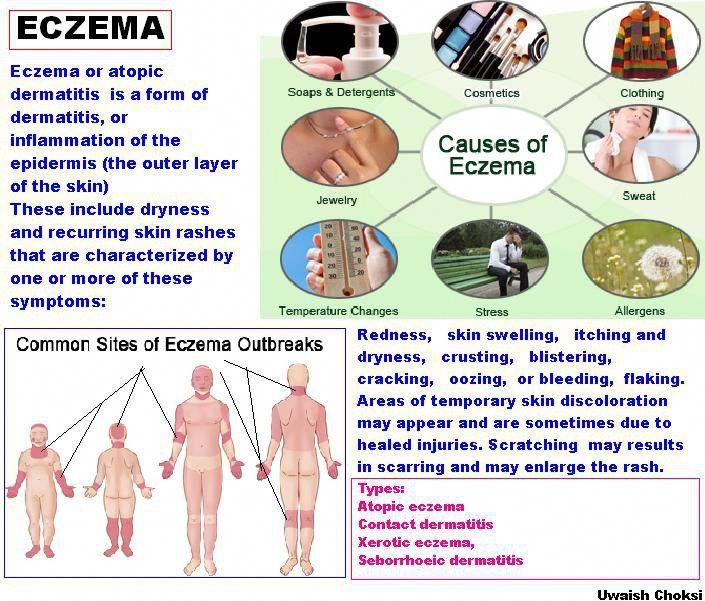

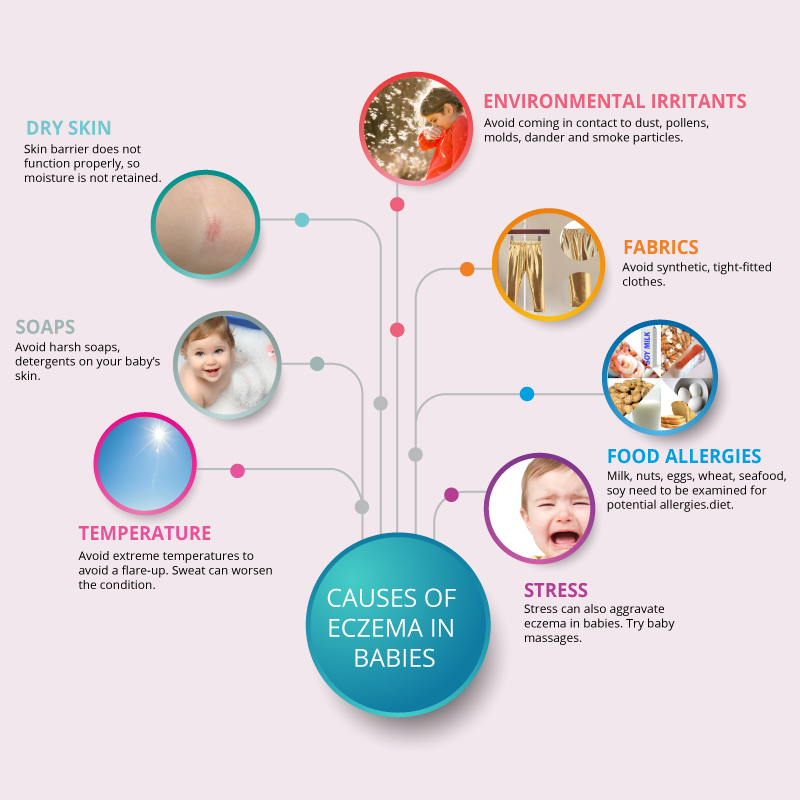

Causes of eczema

The cause of atopic eczema is unknown. Allergies can play a role, but only in conjunction with other factors. The disease has a connection with heredity and the environment. The presence of atopic diseases in other family members (asthma, eczema or allergic rhinitis) is common. In 20-30% of patients, allergies can be detected, which for some of them may be the cause of eczema. Food allergies are never the only cause of eczema. nine0010

Seborrheic eczema is not caused by hypersensitivity, but by a painful reaction in the sebaceous glands, possibly caused by a specific yeast usually found on the surface of the skin. This form of eczema is especially prone to people with oily skin and increased productivity of the sebaceous glands.

This form of eczema is especially prone to people with oily skin and increased productivity of the sebaceous glands.

Contact eczema occurs when the skin reacts to contact with certain substances. The reaction may be allergic or non-allergic. A non-allergic reaction occurs in direct contact with skin irritating substances such as detergents or disinfectants. An allergic reaction is caused by allergenic substances such as nickel, chromium, rubber, formaldehyde and perfumes. Paraphenylenediamine (PPD) is one of the substances frequently associated with allergic contact eczema. PPD is found in many types of hair dye. nine0010

Childhood eczema is caused by irritants found in urine and feces.

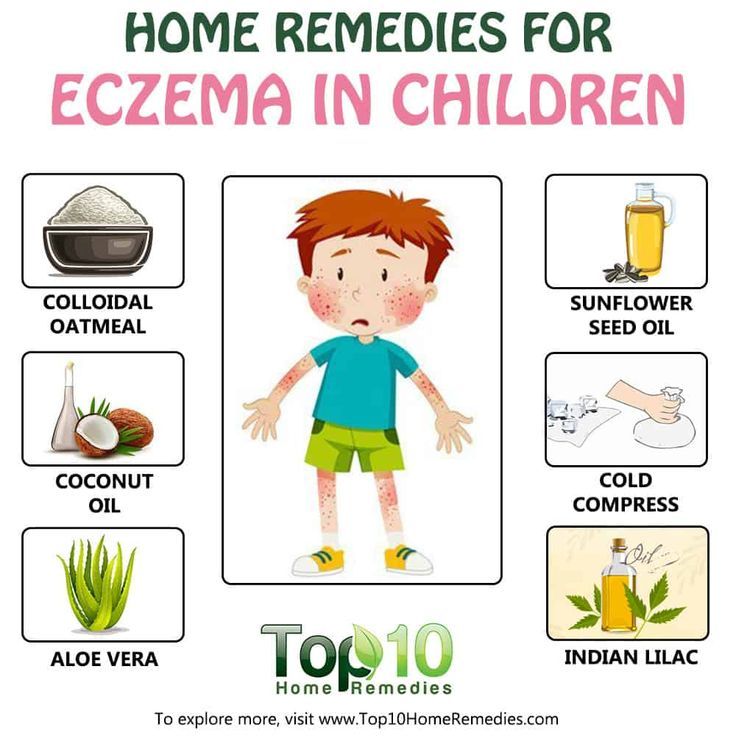

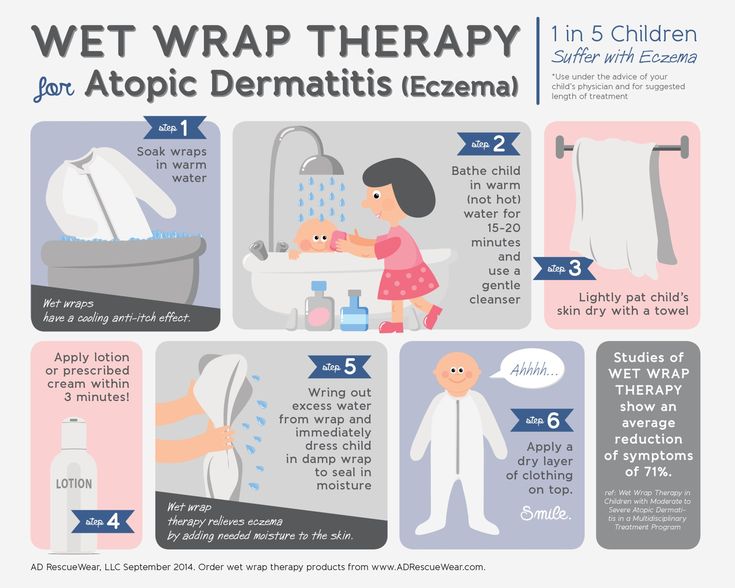

Treatment of eczema

In the treatment of eczema, hygiene, the systematic use of creams and ointments to prevent drying of the skin, refraining from scratching, reducing exposure to irritants, and refraining from eating foods known to be allergic, are the most important. Sunlight and salt baths work well for mild to moderate eczema. Regular bathing with calcium permanganates gives a good preventive effect. nine0010

Sunlight and salt baths work well for mild to moderate eczema. Regular bathing with calcium permanganates gives a good preventive effect. nine0010

However, in most cases a cortisone ointment is necessary. The indicated treatment will give the desired result, provided that the correct drug is applied to the appropriate area of \u200b\u200bthe body at the prescribed frequency. Once control of eczema is established, it is important to reduce the concentration of cortisone ointment, and, if necessary, increase the intervals between applications of the ointment. Proper use of cortisone ointment does not lead to negative effects. The attending physician will give you the necessary recommendations for the use and reduction of the concentration of the drug. nine0010

In general terms, we can say that it is necessary to use strong drugs for a sufficiently long period of time. By opting for weaker drugs, you will not be able to get eczema under control. In this case, the whole process of cortisone treatment may be in vain. Often this leads to increased eczema. It is important to remember that the bad effect of cortisone ointment is due to infection in the eczema itself, which should be treated with antibiotics, both locally and in general. nine0010

Often this leads to increased eczema. It is important to remember that the bad effect of cortisone ointment is due to infection in the eczema itself, which should be treated with antibiotics, both locally and in general. nine0010

In the event of a new flare-up of eczema in a child with a history of the condition, treatment may be initiated with cortisone group 2 or 3. Once the condition has stabilized, the application may be made less frequently (at intervals of 2-3 days). With further improvement in the condition, you can switch to a weaker ointment in order to eventually switch to applying the drug with an interval of 2-3 days.

After healing of eczema, it is recommended to continue applying the drug 1-2 times a week for at least 2-4 weeks, in order to achieve the best result. It is also recommended to use a moisturizer in the morning and evening, as well as every time after taking a bath or shower, even during periods without eczema. nine0010

Children suffering from eczema that regularly flares up and worsens benefit from calcium permanganate baths even during good times. During periods of active eczema, baths with calcium permanganate can be done every day or every other day.

During periods of active eczema, baths with calcium permanganate can be done every day or every other day.

Cortisone-free anti-eczema ointments (Elidel®, Protopic®) are good alternatives to try for chronic eczema. These ointments are applied daily, twice a day. The advantage of these ointments is that they do not affect the thickness of the skin even with prolonged use, and also that they can be used in cases where treatment with cortisone ointments does not lead to the desired result and control of eczema is not established by treatment with cortisone ointments without risk. side effects. nine0010

For skin infections, the infection itself must be treated first, and then the above remedies should be applied.

Medical light or climate treatments for eczema may work. However, some patients may experience a temporary increase in eczema, which is probably due to sweat irritation. In addition, such treatment requires a lot of money and time, which makes it unacceptable for school-age children. This treatment is carried out exclusively by doctors specializing in skin diseases. nine0010

This treatment is carried out exclusively by doctors specializing in skin diseases. nine0010

Achieving positive results depends on how well the patient is informed about the treatment. Eczema can be a very debilitating disease, but early treatment can in most cases bring it under control. Fortunately, the disease eventually subsides on its own, and 80% of patients recover by the age of 18. There is evidence to suggest that quality treatment of eczema leads to an improved prognosis.

Aggravating factors

Rough, tight clothing, rough wools, polyester, heavily dyed fabrics, humidity, stress, infections, food, chlorinated water, tobacco smoke, perfumes, allergies, alkaloid soaps, degreasing chemicals and exposure to heat.

The child knows what clothes cause itching!

Prevention of eczema

Prevention of eczema by controlling the mother's diet during pregnancy, or after the birth of the child, has no effect on the development of atopic eczema in the child. Research shows that symptoms of atopic eczema may be delayed in some cases in children who are breastfed for the first four to six months of life. nine0010

Research shows that symptoms of atopic eczema may be delayed in some cases in children who are breastfed for the first four to six months of life. nine0010

Where to get help

For mild sporadic eczema in children, getting advice from a nurse may be enough. In more complex cases, you should contact your doctor, who, if necessary, will write a referral to a specialist. The hospital free choice system in Norway allows for informed choice. On the Internet site www.frittsykehusvalg.no and free of charge on 800 41 004, you can find out about available eczema treatment sites and your rights in choosing a hospital. nine0010

People suffering from eczema and other skin diseases, as well as people who work with this group of patients, can communicate with specialists at the skin disease clinic, Villa Derma, Oslo University Hospital, by contacting the “skin phone” 23075803 , open for calls three hours a week according to the following schedule: Tuesday and Friday from 8 am to 9 am, Thursday from 12 am to 1 pm (check that this schedule is correct!).

Eczema Facts developed in collaboration with the Medical Board of the Norwegian Asthma and Allergy Association. nine0125

Eczema: what is it, symptoms, causes, types, treatment and diet

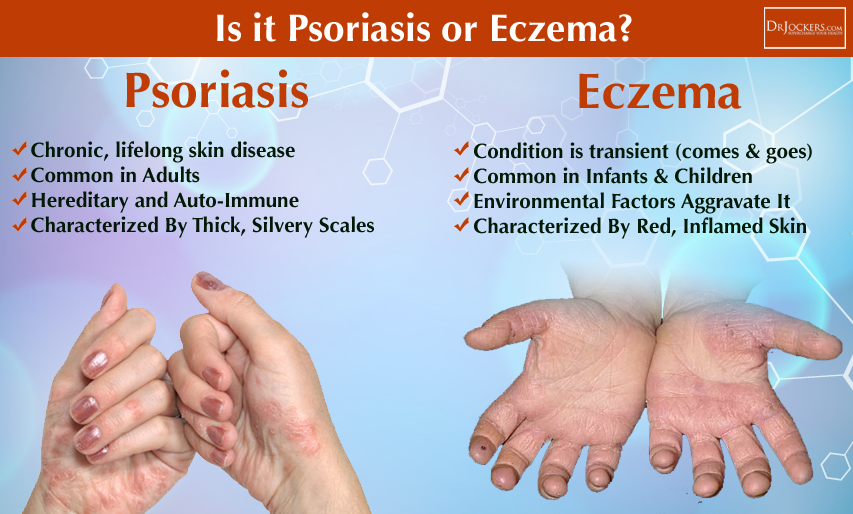

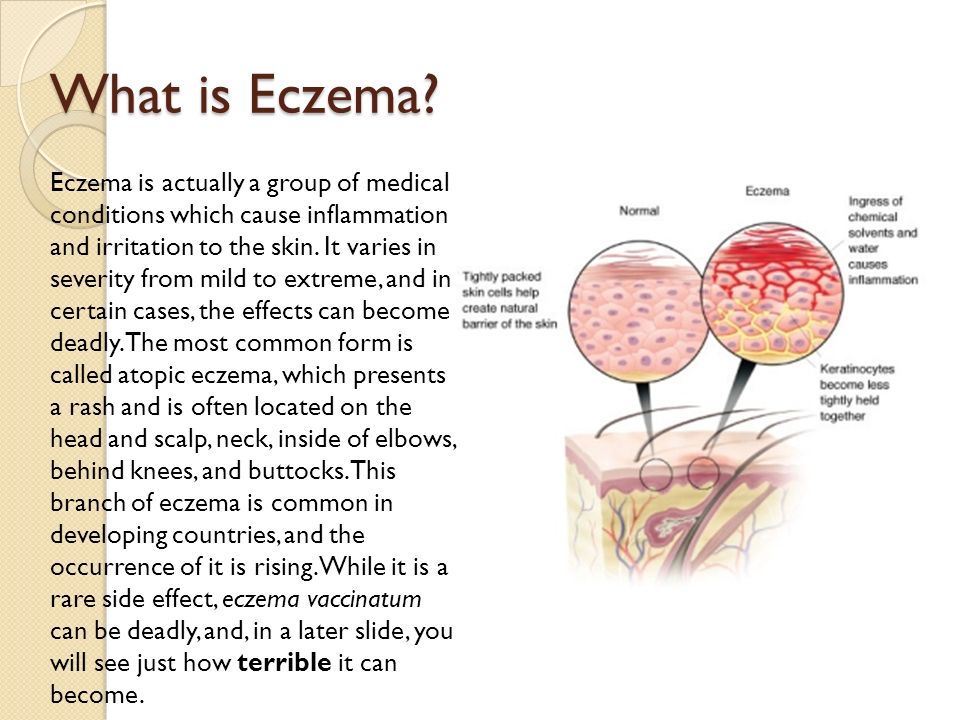

Eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of an allergic nature. The causes of the onset and development of pathology have not yet been studied, but it is believed that allergic diseases and genetic prerequisites are provoking factors. Treatment of eczema is carried out successfully today. You just need to turn to experienced professionals.

What is eczema?

This is a disease characterized by inflammatory processes and characterized by:

- A large number of provoking developmental factors

- Many variants of rash

- Tendency to relapse

- High treatment resistance

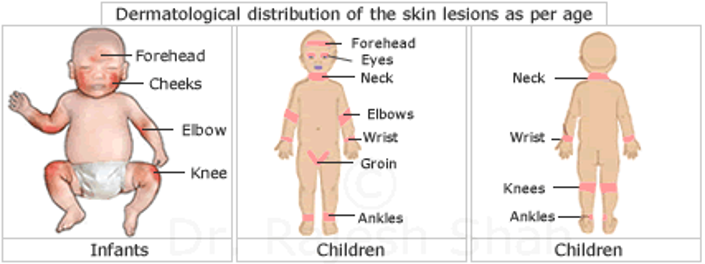

Typically, an eczema rash concentrates on areas such as:

- Neck

- Knees

- Elbows

- Ankles

Symptoms of pathology can periodically increase. Such attacks last from a couple of hours to several days.

Such attacks last from a couple of hours to several days.

Classification

In accordance with the characteristics of the course of the pathological condition, the following are distinguished:

- Acute eczema. Her symptoms usually persist for 1-2 months

- Subacute. Symptoms of this pathology are less pronounced. In this case, the pathology can accompany the patient up to 6 months

- Chronic. In this case, the disease can proceed for several years. Periods of relapses follow remissions

There are several types of pathology:

- True. Such eczema is characterized by a chronic course. Exacerbations occur frequently and are accompanied by the appearance of symmetrical foci of inflammation. At first, areas of the skin turn red and swell. After that, small bubbles form on them. Over time, they open with the release of exudate (a small amount of liquid)

- Microbial. This form of pathology is characterized by the formation of deep ulcers and fistulas.

Pathology is accompanied by severe itching. In the microbial form, foci of inflammation spread mainly to the legs

Pathology is accompanied by severe itching. In the microbial form, foci of inflammation spread mainly to the legs - Seborrheic. This form is characterized by rashes on the face (on the forehead, near the eyebrows, behind the ears) and the scalp. Complete restoration of the skin is possible only with correct therapy

- Children's. This form is characterized by a large amount of exudate

- Professional. This form of pathology is characterized by vivid manifestations. The rash can appear on various areas of the skin (usually those that come into contact with irritants). Irritants in occupational eczema can be either chemical or physical or mechanical. Usually, pathology is provoked by constant exposure to cosmetics, active chemicals, various plants, resins, metals (mainly nickel and chromium)

Reasons

Eczema, the treatment of which should only be carried out by professionals, is quite common.

Its causes include a number of internal and external factors.

Internal factors for the development of eczema:

- Nervous system disorders

- Pathologies of internal organs

- Genetic factors (heredity)

External factors provoking pathology: nine0010

- Increase or decrease in temperature

- Exposure to harsh chemicals

- Influence of extracts of various plants, etc.

Often, a combination of internal and external factors provokes pathology.

Eczema can be the body's response to:

- Contact with pollen

- Excessive sweating

- Immune system disorders

- Stress

- Taking medications

- Taking certain foods

Before starting the treatment of eczema, it is very important to identify the causes that provoked the onset of pathology. Only in this case, the therapy will be as effective as possible and will not drag on for a long time.

Symptoms

All types of eczema are characterized by the following symptoms:

- Appearance of individual inflamed areas on the skin

- Appearance of rash

- Itching

- Bubble Breaker

- Wounds and fissures that cause permanent discomfort

- Increase in body temperature during exacerbations

- General malaise and weakness

- Cracking of the skin, its pronounced dryness and loss of elasticity

Symptoms of the pathological condition largely depend on the stage of development of eczema. nine0010

nine0010

At the erythematous stage, the disease manifests itself in the form of inflamed areas. Gradually, the spots can merge into a separate affected area, which has an impressive area.

At the papular stage, the affected skin becomes unpleasant to the touch. It forms small nodules with clear boundaries and a bright red color.

At the vesicular stage, the nodules turn into vesicles.

At the stage of wetting, the bubbles gradually open, liquid is released from them. nine0010

In the cortical stage, the inflamed areas dry out. Yellowish crusts form on the skin.

At the stage of dry eczema, the skin begins to peel off. Formed crusts gradually disappear. Do not try to rip them off yourself! This can provoke the resumption of pathology.

Diagnostics

Treatment of eczema in adults is possible only after a thorough assessment of its symptoms and causes. That is why it is very important for a doctor to conduct a high-quality diagnosis. nine0010

nine0010

It begins with the collection of anamnesis.

The doctor explains:

- The first cases of manifestation of signs of a pathological process

- Presence of intolerance to certain foods and drugs

- Allergic reactions

At the first appointment, the dermatologist performs a dermatoscopy. This study is aimed at studying the condition of the skin, mucous membranes and scalp. nine0010

Then laboratory tests are carried out.

For the diagnosis of eczema are assigned:

- Urinalysis

- Blood tests

- Serum immunoglobulin test

During the examination, the specialist determines the general state of health of the patient, evaluates individual vital signs. If necessary, a consultation with a nutritionist and an immunologist-allergist is carried out. nine0010

In advanced situations, a comprehensive immunological and allergological examination with sampling is also prescribed. As part of such a diagnosis, doctors are able to identify irritating factors that can provoke symptoms of eczema and allow you to quickly begin to treat the pathology.

As part of such a diagnosis, doctors are able to identify irritating factors that can provoke symptoms of eczema and allow you to quickly begin to treat the pathology.

Treatment

The main task of the doctor after making a diagnosis such as eczema is to reduce or completely eliminate the factors that provoke the onset of symptoms. nine0010

Treatment of pathology is conditionally divided into several stages:

- Taking general medications

- Diet modification

- Use of topical agents in the form of ointments, emulsions, creams, etc.

- Physiotherapy

The following groups of drugs are used for therapy:

- Antihistamines. Such remedies are prescribed for acute eczema nine0138 Glucocorticosteroids. These hormonal drugs relieve inflammation and prevent the development of allergic reactions

- Diuretics. Such funds are recommended for severe edema

- Tranquilizers. These drugs allow you to eliminate itching, ensure a sound and healthy sleep of the patient, his good rest even with severe discomfort in the acute stage of eczema

- Enterosorbents.

These funds allow you to quickly remove all the products of intoxication from the intestines

These funds allow you to quickly remove all the products of intoxication from the intestines - Vitamins of group B, aimed at normalizing the functioning of the nervous system

- Antibiotics. These funds are prescribed if, as a result of the diagnosis, it turned out that eczema is provoked by the action of aggressive microorganisms

Locally, applications with pastes and ointments are usually prescribed, which have:

- Antipruritic

- Anti-inflammatory

- Antiseptic properties

Compositions of preparations for external use are often selected individually. In some cases, "talkers" are prescribed, which are prepared in pharmacies according to a doctor's prescription.

Important! It is strictly forbidden to use folk remedies, various oils, plant extracts, etc. for the treatment of eczema. They are able not to stop the development of the pathological process, but to provoke it.

With regard to physical therapy, patients are usually prescribed: nine0010

- UV

- Magnetotherapy

- Electrophoresis

Treatment of weeping eczema is carried out with the obligatory use of drugs that allow you to dry the skin and ensure the elimination of external signs of pathology. Treatment of other forms of the disease also has individual specificity. The attending physician will tell you about all the subtleties.

Treatment of other forms of the disease also has individual specificity. The attending physician will tell you about all the subtleties.

There are also general recommendations that should be followed by all patients suffering from the disease. nine0010

- Avoid skin contact with aggravating substances (if such substances are identified through tests and samples)

- Dieting. Cocoa, citrus fruits and chocolate should be completely excluded from the diet

- Skin care only with products recommended by a physician

- Elimination of nervous overload and stressful situations

Diet

The basis for the recovery of patients with eczema is often a properly selected diet. When selecting the products you need, the doctor takes into account both the general state of health and the stage and form of the pathology, as well as the presence of concomitant diseases. nine0010

There are also general recommendations regarding nutrition.

All patients during an exacerbation should:

- Avoid spicy, salty and smoked foods

- Refuse sweets

- Eliminate citrus fruits, eggs, alcoholic beverages, dairy products and processed foods from the diet

The diet should include:

- Greenery

- Lean cereals

- Vegetables

During periods of remission, it is desirable to use zucchini and pumpkin, watermelons, gooseberries, lingonberries, currants and cranberries, nuts. Patients who adhere strictly to the diet usually improve rapidly. After a month, the diet can be expanded.

With eczema, the following foods and drinks are strictly prohibited:

- Coffee and cocoa

- Sweets

- Fatty meat nine0138 Tomatoes

- Garlic

- Buns and other pastries

- Melon

- Grenades

- Beetroot

- Strawberry

- Honey

It is advisable to use only those products that are hypoallergenic. A complete list will be given to you by your doctor.

A complete list will be given to you by your doctor.

Benefits of treatment at MEDSI

- Comprehensive diagnosis of eczema. The examination includes laboratory tests, dermatoscopy and video dermatoscopy. Diagnostics is carried out on modern equipment. We have our own laboratory, which allows us to provide patients with test results in the CITO mode (urgently)

- Individual selection of methods for the treatment of eczema in adults and children. Therapy is prescribed taking into account the stage of the pathological process and the characteristics of its course

- Use of modern preparations. Patients are prescribed anti-inflammatory, disinfectant and other drugs that are newly developed, but already have proven effectiveness

- Carrying out modern physiotherapy procedures. Our clinics offer UVA therapy, ozone therapy, magnetotherapy. The combination of modern techniques allows to achieve pronounced treatment results in the shortest possible time

- Treatment of eczema with laser devices.