Can ecv bring on labour

External cephalic version (ECV) | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

External cephalic version (ECV) | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content4-minute read

Listen

Giving birth is more challenging for babies who are bottom-down, or breech, when labour starts. This page explains external cephalic version (ECV), which tries to turn breech babies to the head-down position ready for a normal vaginal birth.

The breech position

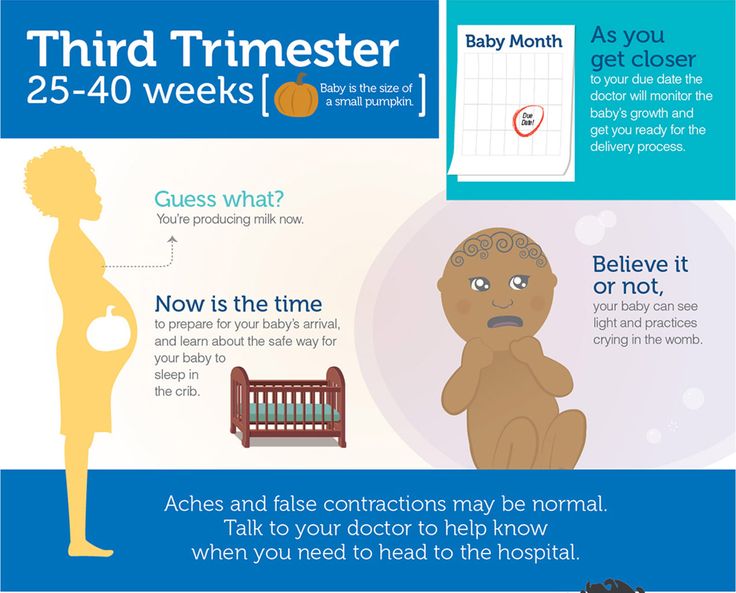

Throughout your pregnancy, your baby repeatedly turns around and changes position. Most babies will settle into a head-down, or 'cephalic', position by 36 weeks of pregnancy. But about 3 in 100 babies are in a breech position at 36 weeks. For these babies, birth would be more difficult than if they were in the cephalic position.

Some breech babies turn naturally in the last month of pregnancy. If this is your first baby, the chance of the baby turning itself after 36 weeks is about 1 in 8. If this is your second or subsequent baby, the chance is about 1 in 3.

If your baby is still in a breech position at 36 weeks, your doctor or midwife might suggest you consider an external cephalic version, or ECV. The aim is to turn your baby so that it is head-down when labour starts.

An ECV is performed after 37 weeks of pregnancy.

Can anyone have an ECV?

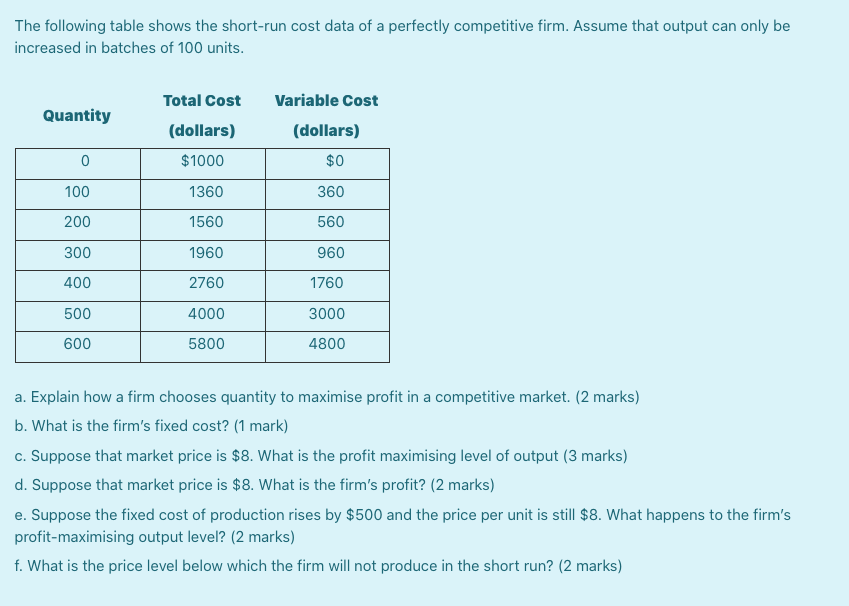

Most women can have an ECV if they have a healthy pregnancy with a normal amount of amniotic fluid. However, an ECV is not recommended if:

- you need a caesarean for other reasons

- you have had vaginal bleeding in the previous 7 days

- the baby's heart rate is not normal

- a complicated pregnancy

- you are having twins or triplets

- you have an unusually shaped uterus

- you recently had vaginal bleeding

- you have placenta praevia (your placenta is growing close to, or on, your cervix)

- other health conditions, like high blood pressure or diabetes

ECV might also not be recommended if your unborn baby is unwell or not growing well.

If you have had a caesarean section before, an ECV can still be performed but there are special considerations that need to be discussed with your doctor.

How is an ECV performed?

A health professional with appropriate expertise, usually an obstetrician, puts their hands on your abdomen to try to turn your baby into a head-down position.

A cardiotocograph, or CTG, will monitor your baby’s wellbeing for 20 to 30 minutes before the procedure.

A small needle will be inserted into your hand so that medication to relax your uterus can be administered directly into your vein.

An obstetrician will then perform an ultrasound to confirm the position of the baby, and then attempt to turn the baby by pressing their hands firmly on your abdomen. Some women find this uncomfortable, while others don’t. The pressure on your abdomen lasts a few minutes. If the first attempt is unsuccessful, the obstetrician might try again.

The CTG might be applied again after the procedure to assess your baby’s wellbeing before you leave.

It usually takes about 3 hours from start to finish.

Where would I have an ECV?

Although complications from an ECV are rare, it is recommended that the procedure is done by an experienced health professional, in a hospital where there are facilities for emergency caesarean section. About 1 in 1,000 women go into labour after an ECV. About 1 in 200 women need an immediate caesarean section.

Will ECV work?

ECV can work, although there is no guarantee of success. If it does work, there is a small chance the baby will turn again to the breech position. But overall, ECV improves a woman’s chances of having a vaginal birth.

What happens if ECV doesn’t work?

A vaginal birth may still be possible, depending on your individual clinical circumstances and the type of breech position your baby is in. Talk to your doctor or midwife about your options.

What other methods are there to potentially turn my baby from a breech position?

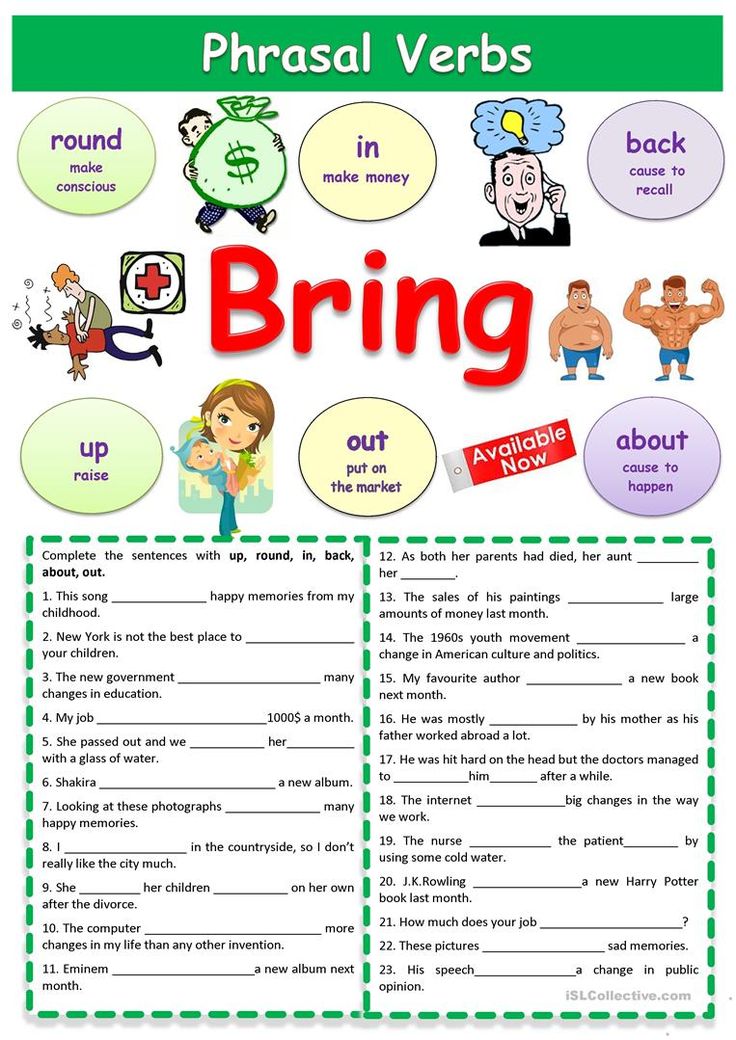

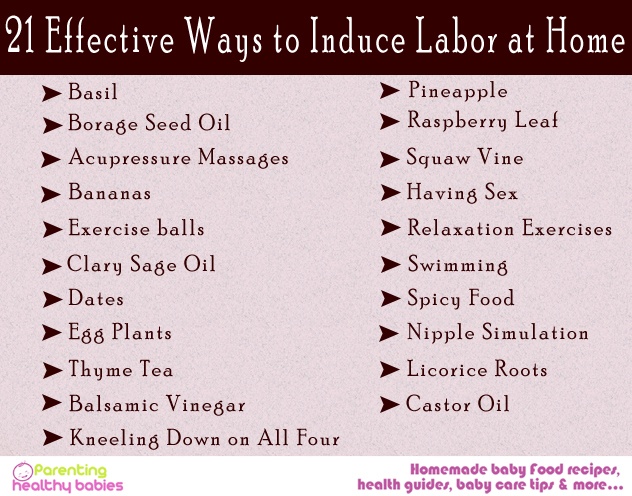

Some people think that you might be able to encourage your baby to turn by holding yourself in certain positions, such as kneeling with your bottom in the air and your head and shoulders flat to the ground. Other options you might hear include acupuncture, a Chinese herb called moxibustion and chiropractic treatment. There is no good evidence that these work. Discuss with your doctor or midwife before having any treatment during pregnancy.

Other options you might hear include acupuncture, a Chinese herb called moxibustion and chiropractic treatment. There is no good evidence that these work. Discuss with your doctor or midwife before having any treatment during pregnancy.

Sources:

Mater Hospital Brisbane (Pregnancy: External Cephalic Version), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Breech Presentation at the End of your Pregnancy), BioMed Central (Does moxibustion work? An overview of systematic reviews (BMC Research Notes 20103:284)), Department of Health (Clinical practice guidelines: Pregnancy care), SA Department for Health and Ageing (Perinatal practice guideline: Breech presentation), NSW Health (External Cephalic Version (ECV) for Breech Presentation)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: April 2020

Back To Top

Related pages

- Breech birth

- Breech pregnancy

Need more information?

External Cephalic Version for Breech Presentation - Maternal, child and family health

This information brochure provides information about an External Cephalic Version (ECV) for breech presentation

Read more on NSW Health website

Breech presentation and turning the baby

In preparation for a safe birth, your health team will need to turn your baby if it is in a bottom first ‘breech’ position.

Read more on WA Health website

Breech pregnancy

When a baby is positioned bottom-down late in pregnancy, this is called the breech position.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Malpresentation

Malpresentation is when your baby is in an unusual position as the birth approaches. Sometimes it’s possible to move the baby, but a caesarean maybe safer.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Labour complications

Even if you’re healthy and well prepared for childbirth, there’s always a chance of unexpected problems. Learn more about labour complications.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Pregnancy at week 35

You'll probably be having lots of Braxton Hicks contractions by now. It's your body's way of preparing for the birth. They should stop if you move position.

They should stop if you move position.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Anatomy of pregnancy and birth - pelvis

The pelvis helps carry your growing baby and is especially tailored for vaginal births. Learn more about the structure and function of the female pelvis.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Rhesus D negative in pregnancy

Find out what being Rhesus D negative could mean for your baby and how it is treated.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Placental abruption - Better Health Channel

Placental abruption means the placenta has detached from the wall of the uterus, starving the baby of oxygen and nutrients.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Glossary of pregnancy and labour

Glossary of common terms and abbreviations used in pregnancy and labour.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

OKNeed further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

External Cephalic Version (ECV) - 5 Things to Consider Before Having One

You’re nearing full term and getting excited for the big day.

You’re about to meet your bundle of joy!

Then, at your prenatal appointment you’re told baby isn’t head down.

Now you’re not sure how birth will unfold.

You’ve already envisioned your birth experience and this new found information could change everything.

As the news begins to settle in you want to know what this can mean for birth. When you think of your baby not being head down you think C-section because that’s what we hear so often. You aren’t sure if baby will turn, if baby can turn or what your maternity care provider can do to help.

Is a C-section birth your only option?

Sometimes a C-section might be necessary, but it isn’t always.

If baby isn’t head down you have a few options:

- Use alternative methods to facilitate movement, such as chiropractic care, acupuncture and at-home exercises to encourage optimal fetal positioning. If it results in a successful turn, you will likely wait for labour to begin spontaneously

- Waiting for labour to begin spontaneously while hoping baby will turn right before or during labour (which is known to happen). Also being prepared for a vaginal breech birth or unscheduled c-section for a breech or transverse baby

- Scheduled c-section around the estimated due date, or an emergency c-section if labour begins prior to the scheduled c-section

- Attempt an external cephalic version (ECV) to get baby head down.

If successful, some women will then opt for an induction, so baby is born before possibly turning again. Other women wait for labor to begin spontaneously

If successful, some women will then opt for an induction, so baby is born before possibly turning again. Other women wait for labor to begin spontaneously

An ECV is when your healthcare provider uses their hands externally on your belly to manually turn the baby into a head down position.

When deciding whether or not to attempt an ECV there are somethings to keep in mind.

Here are 5 things to consider when deciding about an ECV:

#1: Are You a Candidate For an ECV?

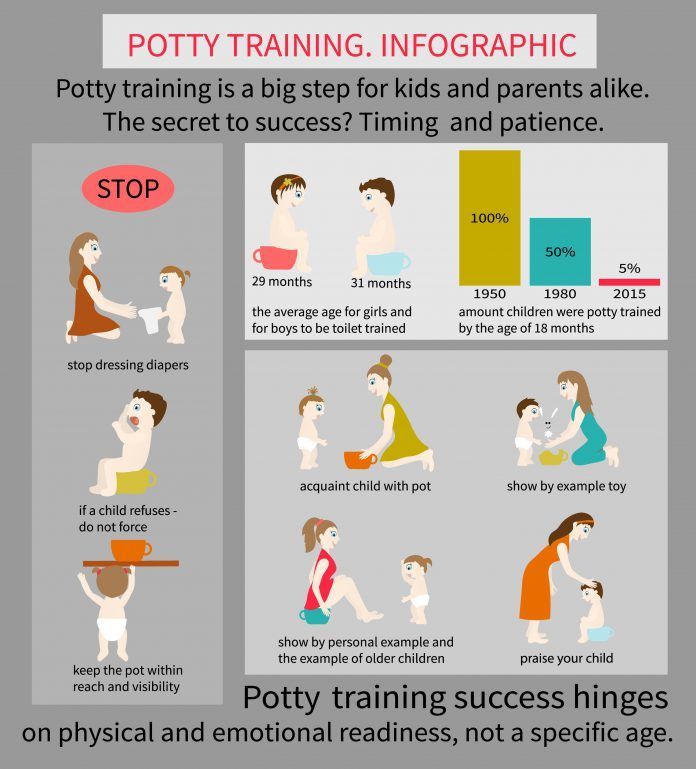

While ECVs are considered a safe option for some, the risks may not outweigh the benefits for others. Most providers will not perform an ECV before full term for a couple reasons. One, it could cause labor to begin or delivery could become necessary. Two, many babies turn on their own before being full-term. Only around 4% of babies are breech at full-term gestation.

If you have a breech or transverse pregnancy with only one baby you might be a candidate for an ECV. Most providers will not perform an ECV for multiples as there is more potential for complications.

You need to have no signs of placental concerns such as previa, bleeding or intrauterine growth restriction. Adequate fluid levels (you bag of waters must be intact) and baby having a good heart rate are also necessary for ECV.

You also need to be healthy with no signs of pregnancy induced hypertension or other pregnancy complications.

#2: Understanding How an ECV is Performed

Sometimes fear is simply that of the unknown. When you first hear baby isn’t head down a lot of the concern is not knowing how things will unfold. With an ECV, the fear can be similar, you aren’t sure what is going to happen.

Every provider is different so the steps may vary, but ECVs are pretty similar among most providers. Your ECV might unfold like this:

- Some providers will draw labs to be sure of blood type and iron levels in case an emergency birth becomes necessary

- A non-stress test is done to ensure baby is likely to tolerate the procedure well

- An ultrasound is done to determine baby’s exact position

- Baby’s heart rate is monitored before, during and after the ECV attempt

- Some providers offer or recommend an epidural for the procedure

- One or two healthcare providers will place their hand on your belly and attempt to gently maneuver baby into a head down position

- Following the procedure, successful or not, another non-stress test might be performed to be sure baby handled the procedure well

ECV are successful about 65% of the time. The procedure is stopped if it seems baby will not safely turn, if the mother-to-be is too uncomfortable, if any placental concerns arise or if baby’s heart rate becomes concerning.

The procedure is stopped if it seems baby will not safely turn, if the mother-to-be is too uncomfortable, if any placental concerns arise or if baby’s heart rate becomes concerning.

#3: Are You Comfortable With Attempting The Procedure?

An ECV can be physically uncomfortable for some as well as emotionally taxing. Being okay with the potential for discomfort and even pain (though many mamas do not report pain) is part of the decision making process.

Some providers will administer an epidural for an ECV. An epidural can eliminate pain and discomfort, but also weighing the benefit and risks of an epidural is important. An epidural can also help mama to relax, as well as her uterus. In rare cases, the relaxation alone can facilitate baby moving without the ECV being performed. An epidural might also be helpful in the case of emergency complications.

Baby is manually moved and guided from the outside. For some parents this is concerning. If an ECV is desired, choosing a care provider that is comfortable, confident and experienced with ECV can eliminate some concerns.

#4: Are You Prepared to Have Baby Today?

On the day of your ECV, it’s important to be prepared to give birth that day, just in case. If the version is successful, some (but not all) providers will offer an induction so baby does not have the opportunity to turn again.

If baby’s heart rate drops, there are signs of cord concerns, or there are any concerns about the placenta, an emergency c-section may become necessary.

If the version is successful and you and baby tolerate it well, you might be sent home to wait until labor begins on its own. Some babies do turn back to breech/transverse positions following a version. In this case some will attempt a second ECV.

Before the version, weigh the benefits and risks of this so you aren’t having to make a stressful decision in the moment.

#5: External Cephalic Version Risks

Knowing the benefits and the risks of an ECV will help you make an informed decision.

Some of the benefits of an ECV include:

- The ability to have a low risk vaginal birth with baby head down

- Possibly avoid a c-section which eliminates the risks associated with surgery

- When successful, mama and baby reap the benefits of a vaginal birth

- The possibility of a faster birth recovery than a c-section or vaginal birth with complications

- When induction or c-section birth isn’t necessary and an ECV is successful, baby is able to be born spontaneously

Some risks associated with an ECV:

- Complications during an ECV can necessitate an emergency c-section

- A small risk of placental abruption, and risks associated with that

- Cord compression, twisting, etc

- Fetal distress

- Premature rupture of membranes (water breaking before labour begins)

When pregnancy and birth deviate from what we expected, it can certainly hit us for six. Fortunately, there are several options available to help baby safely arrive earth-side. Making a decision can be difficult, but weighing your birth preferences, benefits and risks can help you decide if an ECV might be for you.

Fortunately, there are several options available to help baby safely arrive earth-side. Making a decision can be difficult, but weighing your birth preferences, benefits and risks can help you decide if an ECV might be for you.

Induction of labor or induction of labor

The purpose of this information material is to familiarize the patient with the induction of labor procedure and to provide information on how and why it is performed.

In most cases, labor begins between the 37th and 42nd weeks of pregnancy. Such births are called spontaneous. If medications or medical devices are used before the onset of spontaneous labor, then the terms "stimulated" or "induced" labor are used in this case. nine0003

Labor should be induced when further pregnancy is for some reason unsafe for the mother or baby and it is not possible to wait for spontaneous labor to begin.

The purpose of stimulation is to start labor by stimulating uterine contractions.

When inducing labor, the patient must be in the hospital so that both mother and baby can be closely monitored.

Labor induction methods

The choice of labor induction method depends on the maturity of the cervix of the patient, which is assessed using the Bishop scale (when viewed through the vagina, the position of the cervix, the degree of its dilatation, consistency, length, and the position of the presenting part of the fetus in the pelvic area are assessed). Also important is the medical history (medical history) of the patient, for example, a past caesarean section or operations on the uterus.

The following methods are used to induce (stimulate) labor:

- Oral misoprostol is a drug that is a synthetic analogue of prostaglandins found in the body. It prepares the body for childbirth, under its action the cervix becomes softer and begins to open.

- Balloon Catheter - A small tube is placed in the cervix and the balloon attached to the end is filled with fluid to apply mechanical pressure to the cervix. When using this method, the cervix becomes softer and begins to open.

The balloon catheter is kept inside until it spontaneously exits or until the next gynecological examination. nine0022

The balloon catheter is kept inside until it spontaneously exits or until the next gynecological examination. nine0022 - Amniotomy or opening of the fetal bladder - in this case, during a gynecological examination, when the cervix has already dilated sufficiently, the fetal bladder is artificially opened. When the amniotic fluid breaks, spontaneous uterine contractions will begin, or intravenous medication may be used to stimulate them.

- Intravenously injected synthetic oxytocin - acts similarly to the hormone of the same name produced in the body. The drug is given by intravenous infusion when the cervix has already dilated (to support uterine contractions). The dose of the drug can be increased as needed to achieve regular uterine contractions. nine0022

When is it necessary to induce labor?

Labor induction is recommended when the benefits outweigh the risks.

Induction of labor may be indicated in the following cases:

- The patient has a comorbid condition complicating pregnancy (eg, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, or some other condition).

- The duration of pregnancy is already exceeding the norm - the probability of intrauterine death of the fetus increases after the 42nd week of pregnancy. nine0022

- Fetal problems, eg, problems with fetal development, abnormal amount of amniotic fluid, changes in fetal condition, various fetal disorders.

- If the amniotic fluid has broken and uterine contractions have not started within the next 24 hours, there is an increased risk of inflammation in both the mother and the fetus. This indication does not apply in case of preterm labor, when preparation of the baby's lungs with a special medicine is necessary before delivery. nine0022

- Intrauterine fetal death.

What are the risks associated with labor induction?

Labor induction is not usually associated with significant complications.

Occasionally, after receiving misoprostol, a patient may develop fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, and too frequent uterine contractions (tachysystole). In case of too frequent contractions to relax the uterus, the patient is injected intravenously relaxing muscles uterus medicine. It is not safe to use misoprostol if you have had a previous caesarean section as there is a risk of rupture of the uterine scar.

In case of too frequent contractions to relax the uterus, the patient is injected intravenously relaxing muscles uterus medicine. It is not safe to use misoprostol if you have had a previous caesarean section as there is a risk of rupture of the uterine scar.

The use of a balloon catheter increases the risk of inflammation inside the uterus.

When using oxytocin, the patient may rarely experience a decrease in blood pressure, tachycardia (rapid heartbeat), hyponatremia (lack of sodium in the blood), which may result in headache, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, depression strength and sleepiness. nine0003

Induction of labor, compared with spontaneous labor, increases the risk of prolonged labor, the need for instrumentation

(use of vacuum or forceps), postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, the onset of too frequent uterine contractions and the associated deterioration of the fetus, prolapse umbilical cord, as well as premature detachment of the placenta.

If induction of labor is not successful

The time frame for induction of labor varies from patient to patient, on average labor begins within 24-72 hours. Sometimes more than one method is required. nine0003

The methods used do not always work equally quickly and in the same way on different patients. If the cervix does not dilate as a result of induction of labor, your doctor will tell you about your next options (which may include inducing labor later, using a different method, or delivering by caesarean section).

ITK833

This informational material was approved by the Women's Clinic on 01/01/2022.

Induction of labor at or near the end of pregnancy if a large fetus (macrosomia) is suspected

What is the problem?

Very large babies (or macrosomates weighing more than 4000 g at birth) may have difficult or sometimes traumatic births. One suggestion to reduce this injury is to induce labor before the baby grows too large. Estimating a baby's weight before birth is difficult and not entirely accurate. Clinical assessment is based on palpation of the uterus and determination of the height of the uterine fundus. Both methods are subject to significant variations. Ultrasound examination also does not give accurate results, so the assumption of a large fetus may not be confirmed at birth. This may worry parents. nine0003

Estimating a baby's weight before birth is difficult and not entirely accurate. Clinical assessment is based on palpation of the uterus and determination of the height of the uterine fundus. Both methods are subject to significant variations. Ultrasound examination also does not give accurate results, so the assumption of a large fetus may not be confirmed at birth. This may worry parents. nine0003

Why is this important?

Induction of labor too early can result in the baby being born prematurely or with insufficient organ maturity.

What evidence did we find?

We found four studies that evaluated labor induction at 37-40 weeks in women with suspected large fetuses. 1190 pregnant women without diabetes were examined. We searched for evidence up to 31 October 2015. These studies were of average to good quality, although it was not possible to "blind" the women or their caregivers into not knowing which group a woman belonged to. This could introduce a bias (bias, evaluation bias). nine0003

This could introduce a bias (bias, evaluation bias). nine0003

What does this mean?

The number of deliveries in which the baby's shoulders got stuck (shoulder dystocia) or a bone fracture occurred (usually the collarbone, which heals well without sequelae) was lower in the induced labor group. This evidence was rated as moderate quality evidence for shoulder dystocia and high quality evidence for fractures. There was no clear difference between the groups in terms of damage to the nerve plexuses that send signals from the spinal cord to the shoulder, forearm and hand (brachial plexus injury) of the child (low-quality evidence due to the very small number of such cases) or oxygen deprivation during time of birth. The labor induction policy reduced the average birth weight of a child by 178 g. Studies did not show any difference in the number of women who had a caesarean section or instrumental delivery. There is limited evidence that women in the induced labor group had more severe perineal injuries.