How does an autistic child see the world

How people with autism see the world - News at Curtin

“Too fast!” cried Dr Susan Morris’ son as he tearfully learned to ride a bicycle. He frequently lost his balance and struggled to tell whether his bicycle was moving forward or was stationary. Later diagnosed with high-functioning autism, he continued to misinterpret visual cues in daily life, leading his mother to question whether autism and visual motion processing are intrinsically linked.

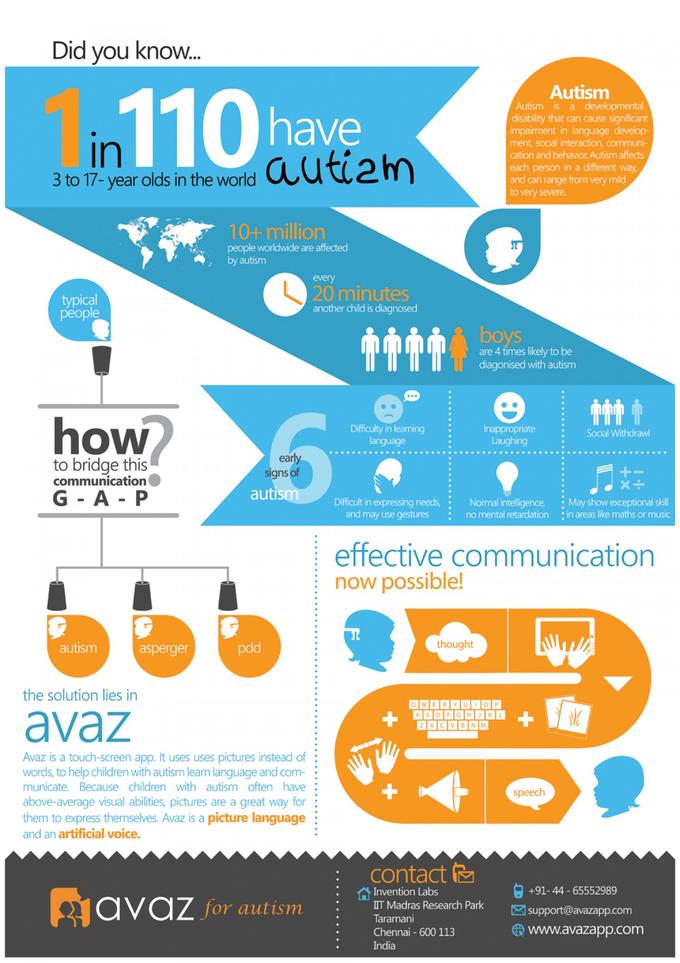

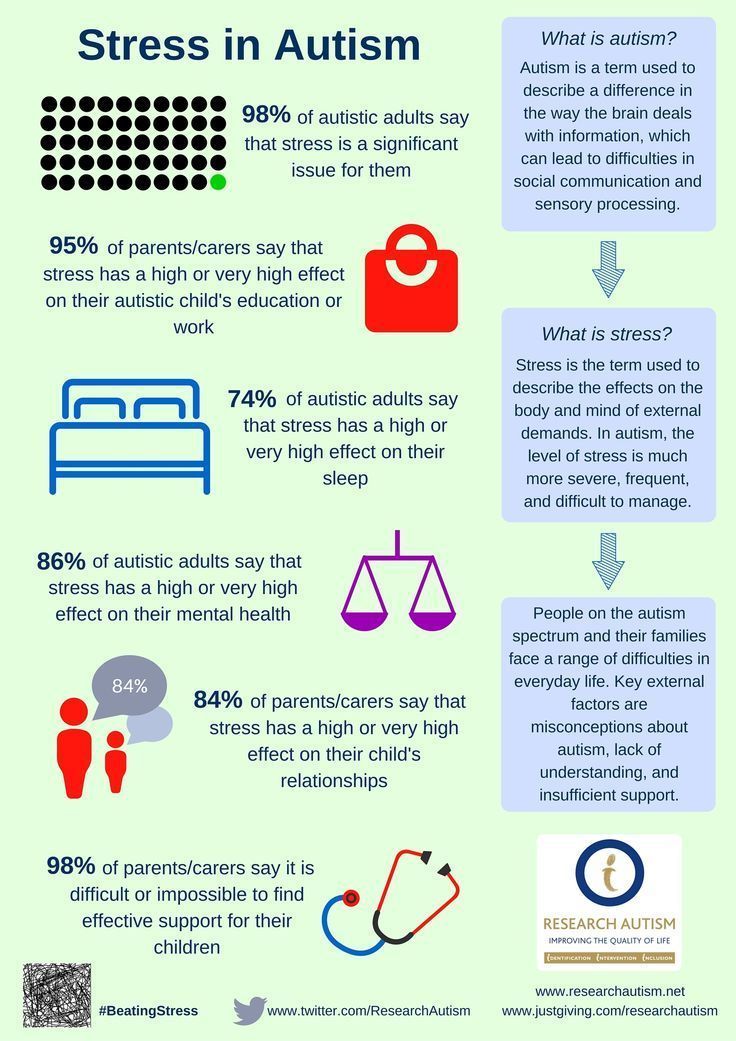

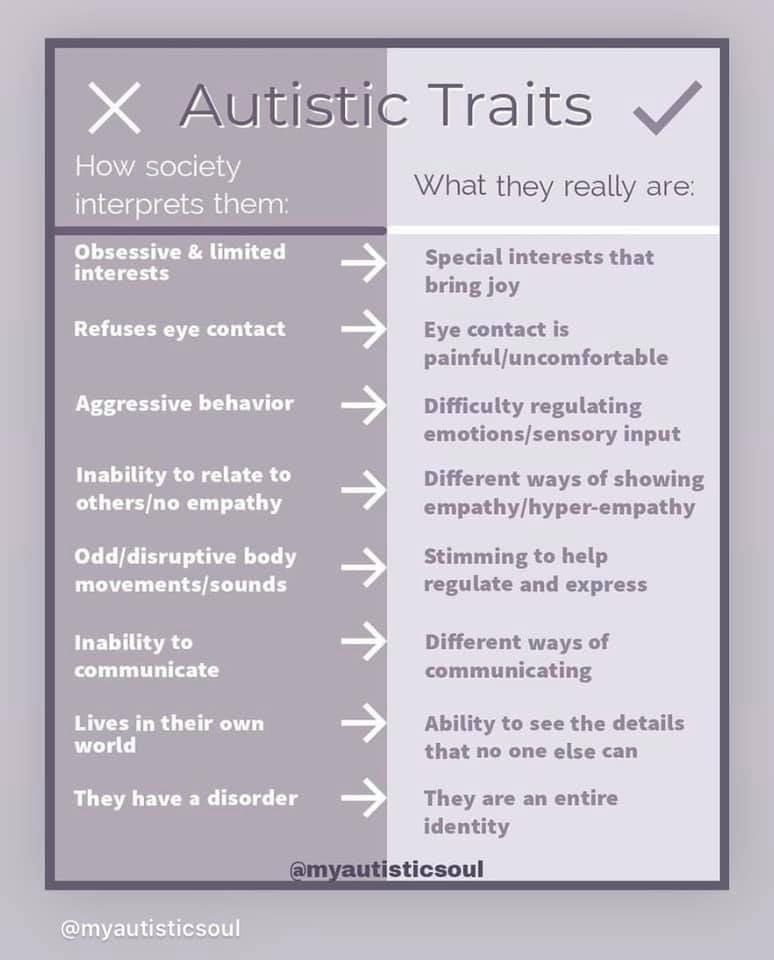

For people on the autism spectrum, the world is a bewildering place. With oversensitive sensory systems, they battle to process the maelstrom of information flowing into their brains. Often the result is sensory overload, leading to signature behaviours such as tantrums, anxiety and social withdrawal.

“Their natural ability to pare down information appears to be missing – the ‘filters’ are not working. And so whatever their behaviours are, it is to manage those filters, and keep the world constant and predictable,” Morris explains.

As a researcher in sensorimotor control, Morris has dedicated her research to exploring links between visual motion processing and autism, determined to develop interventions that reduce the disability it causes.

She has discovered that people on the autism spectrum have increased sensitivity to visual motion in their peripheral field of vision, which affects how they perceive their environment and where they place themselves in time and space.

“Most people with autism have motor coordination problems. Sensory responses influence motor responses and they feed back on each other in a loop.”

Her team’s first study determined how people used visual processing for postural control, by inducing postural illusion using muscle stimulation.

She realised that while everyone in the study leaned forward in response to the stimulation with their eyes closed, only the ‘neurotypical’ adults corrected their posture when their eyes were open.

“The people with autism did not use their vision to stabilise themselves – and that affected their motor control and movement,” she says.

The team’s second study compared the way in which people with autism processed optic flow, using streamed images of moving stars that filled their primary and peripheral vision, creating a visual illusion of self-movement.

“When the stars flow out, it feels like you are going through space and your body will naturally lean backwards. When the stars flow the opposite way, it’s like you are driving backwards through space, and you lean forwards into it.”

She observed that while everyone leaned when exposed to the whole visual field, the results were different when motion was limited to the periphery.

In the forward direction, all the adults ignored movement on the periphery – behaviour Morris believes is learned from daily activities such as driving in a car. However, in the backward direction only the adults with autism leaned forwards.

“When only part of the visual field moved, the neurotypical adults saw peripheral optic flow as something moving, whereas the adults with autism perceived it as self-motion. ”

”

Morris likens this experience to linear vection, where an observer feels like they have moved and the stimulus has stayed stationary.

“Imagine you are on a train and then out of the window you see the train next to you start to move. For a moment you’re unsure if you’re moving or the train outside the window is moving. Perhaps this is the experience of people with autism most of the time.”

Morris is repeating the experiment with children aged between eight and 10 years to find out at which point in life people naturally learn to filter peripheral motion.

“Children have had less exposure to peripheral optic flow and so this study may determine whether visual development in individuals with autism is due to immaturity in visual information processing, or the result of a different developmental trajectory.”

While her findings could inform intervention strategies, Morris believes an individual’s brain chemistry is another consideration – specifically the activity of inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

“GABA has been demonstrated to be lower in people with autism. If GABA is not working properly, inhibitory circuits don’t work with the same timing or in the same amount as the excitatory circuits – and as a result, excitatory circuits are not switched off.”

GABA imbalance has also been linked to other brain processing disorders such as ADHD, dyslexia, central auditory processing disorder and social anxiety disorders.

“Are these conditions discrete?” Morris ventures. “People with visual disorders quite often have autistic characteristics. The fundamental underlying issue may be similar, which is related to processing information. Maybe they are all spectrums of a common problem.”

Undoubtedly, this conjecture is a topic for wider discussion, but for now Morris is developing therapies that “reduce the overwhelm” and encourage adaptation, so people with autism can lead relatively normal lives.

Now with her son fast approaching adulthood, Morris remains resolute about making a difference. When asked where her end point is, her reply is simple:

When asked where her end point is, her reply is simple:

“How we see the world impacts incredibly on where we go. This project is ongoing – for the rest of my career!”

Learn about the Curtin Autism Research Group

How People With Autism See the World

US Markets Loading... H M S In the news

Chevron iconIt indicates an expandable section or menu, or sometimes previous / next navigation options.HOMEPAGETech News

Save Article IconA bookmarkShare iconAn curved arrow pointing right. Read in app Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042

doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042 People with autism see the world differently.

They typically don't look at faces as closely; they can be more easily overwhelmed by too many stimuli; and they may fixate intensely on one thing at a time.

Previous research found these and other differences, but a new study helps you see the world how many people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) might.

The study, published in October in the journal Neuron, tracked 39 participants' eyes as they looked at 700 different images. Half of the participants had been officially diagnosed with ASD, and the other half were "neurotypical," meaning they didn't meet enough diagnostic criteria to be considered autistic.

"Among other findings, our work shows that the story is not as simple as saying 'people with ASD don't look normally at faces. ' They don't look at most things in a typical way," study co-author Ralph Adolphs, a neuroscientist at CalTech, said in a press release.

' They don't look at most things in a typical way," study co-author Ralph Adolphs, a neuroscientist at CalTech, said in a press release.

These images show what participants' eyes gravitated toward, with the reddish areas showing the most looked-at spots. In every image, the participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right.

In the study, people with autism tended to focus on the center of images, even when other objects were in a photo.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j. neuron.2015.09.042

neuron.2015.09.042 People with autism also looked at the edges and patterns in the images rather than faces.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042Participants only viewed each image for three seconds, so it captured their first instincts.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042 People with autism tended not to follow the object of people's gazes in the photos, while neurotypical participants did.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042

doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042 You can see how the changes in attention between neurotypical participants and those with autism differ.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j. neuron.2015.09.042

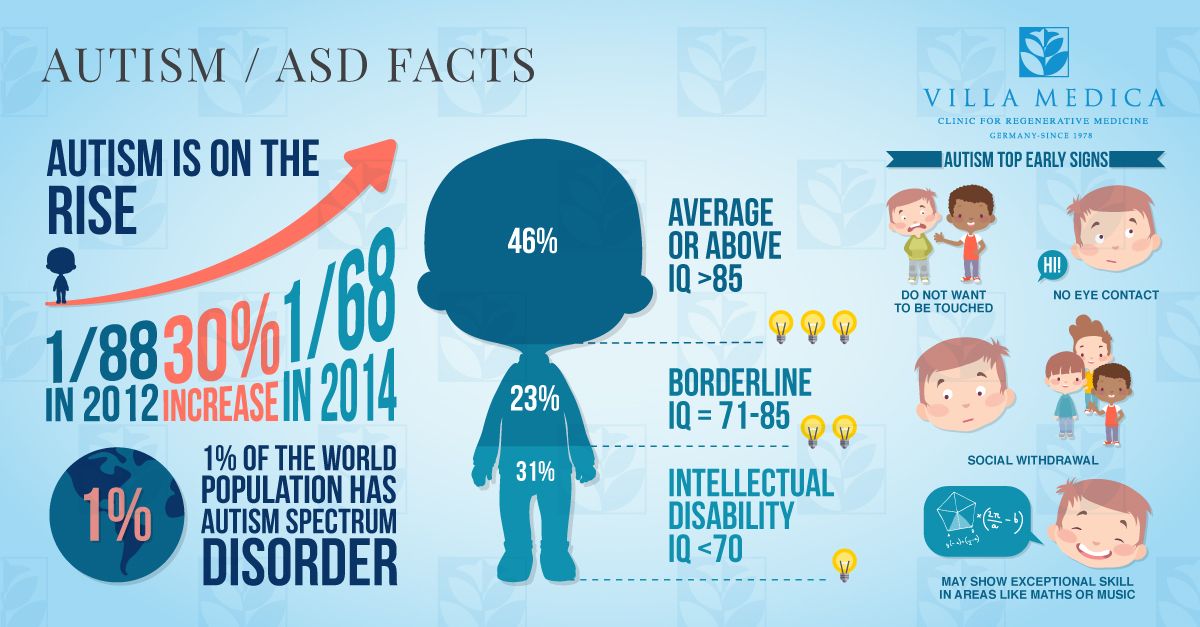

neuron.2015.09.042 About one in 68 children in the US have autism — a rate that's higher today than in the past due to new diagnostic criteria and a surge in awareness.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042Source: CDC

While doctors are getting better at diagnosing children with the disorder, it's still pretty difficult to do.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042 Researchers are looking at ways to diagnose autism earlier, so interventions can begin sooner rather than later. Eye-tracking could help.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042

doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042 Source: BabySibs

The BabySibs project, for example, is using eye-tracking software to find diagnosable differences between infants with autism and those who are neurotypical.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10. 1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042

1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042 Source: BabySibs

BabySibs researchers have found that babies with autism prefer to look at scrambled faces rather than normal pictures of faces.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042Source: BabySibs

Infants with autism actually prefer to listen to computer-generated sounds rather than speech, too, the BabySibs project found.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042 Source: 2013 study

If doctors and parents can identify children with autism sooner, hopefully they can receive the support they need to live more fulfilling lives.

Participants with autism are on the left and the neurotypical participants are on the right. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042

doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.042 Read next

LoadingSomething is loading.Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you're on the go.

Autism Health Child DevelopmentMore. ..

..

How autistics see us | PSYCHOLOGIES

73,633

Man among men

These are strange children. Their eyes elude us, and we ask ourselves if they see us at all. Their behavior is surprising, and even frightening: they can randomly wave their arms for a long time, spin around in one place or ask the same question many times in a monotone voice ... Autism - the name of the disorder they suffer from - often turns into an insulting mockery breaking the hearts of parents. nine0003

Over the past two decades, the number of people diagnosed with autism has been growing rapidly around the world. “For example, in the US, this diagnosis is made to one in 88 children,” says psychiatrist Brian King, director of the Seattle Center for Children with Autism (USA). “And in South Korea, even one in 38.” There are no exact figures for Russia, but, according to experts, in any class and in any group of kindergarten there is a child with one of the mild forms of autism.

A few months after birth, these children already seem unusual (although the diagnosis is made at a year and a half). Manifestations are extremely diverse, not without reason experts say: "If you know one person with autism, this does not mean that you know about autism." nine0003

Some children will acquire speech, others will not. Some will lag behind in mental development (about 45% of them), others will show a brilliant intellect or a phenomenal memory. Someone will make discoveries or write books, and someone will never be able to learn to read. But no matter how different they are, people with autism are able to open up if we make an effort to teach them how to communicate with us.

They do not distinguish a person's voice from other sounds

The originality of an autist is primarily in the fact that he hears, sees, and feels reality in a different way. nine0003

“Due to genetic disorders, the brains of these children are overactive,” says Monika Zilbovicius, a psychologist at the French Institute for Health and Medical Research (Inserm). - He simply does not have time to combine, analyze everything that the child sees, hears, touches. The world is perceived fragmentary and distorted.

- He simply does not have time to combine, analyze everything that the child sees, hears, touches. The world is perceived fragmentary and distorted.

Perceptual impairment can cause a child to confuse a raised finger with a pencil, for example. For him, the human voice is no different from other sounds: he does not respond to his name (it seems to his parents that he does not hear), but he flinches when a car passes along the street. Such sensory confusion also occurs in relation to touch: “Masha is now 4 years old, she cannot stand the touch of soft materials like velvet, as if they burn her,” her mother says. “But she likes to touch and stroke the spiky washcloth.” nine0003

Their sensations are not connected

We all communicate with other people through the senses, they help to navigate the world and understand others. Data from the organs of sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell, entering the brain of a child with autism, are superimposed on each other, like bricks that are not cemented together. And as soon as something unexpected happens, such as a loud phone call or a strong desire to go to the toilet, the unstable pile of “sensory bricks” crumbles. There is panic. nine0003

And as soon as something unexpected happens, such as a loud phone call or a strong desire to go to the toilet, the unstable pile of “sensory bricks” crumbles. There is panic. nine0003

Nine-year-old Maxim, for example, cannot stand applause. This sound causes an acute anxiety in the boy, because of which he can completely lose control of himself. Anomaly of sensory perception is the cause of inexplicable crying in children with autism at an early age. Hence their desire to find a sensation that will calm the inner storm: to look at a spinning toy, to bite oneself, to sway.

Some stereotyped movements are typical of autism, such as the rapid flailing of the arms, which parents describe as a frightened bird or butterfly beating its wings. All these repetitive movements soothe such children, restoring their self-confidence and a sense of security. nine0003

Change is possible

“Autism is “growing differently”: these children think and learn in their own way, they perceive information differently,” says Joe Stevens, director of the EarlyBird autism program (UK). “We don't have a magic ball to see what the child will be like in the future. But everyone can achieve positive changes. Parents are their child's best teachers, but they need the support of professionals. There is only one reason for failure - if the child has not been selected the right assistance program for him. We need not to calm down, but to continue to look for tools that will allow him to communicate with the world.” nine0003

“We don't have a magic ball to see what the child will be like in the future. But everyone can achieve positive changes. Parents are their child's best teachers, but they need the support of professionals. There is only one reason for failure - if the child has not been selected the right assistance program for him. We need not to calm down, but to continue to look for tools that will allow him to communicate with the world.” nine0003

They don't pick up other people's emotions

We can communicate with other people because we are able to understand their feelings. From the very first months of life, the baby learns to distinguish the expression on the mother's face and to capture her emotional state. Gradually, he begins to establish connections between his feelings and what is happening in the outside world.

For example, when falling, children always look at the reaction of their parents. If the mother is frightened and frowns, the child understands that something bad has happened, but if she helps him up with a smile, then this event no longer looks dramatic for him. Over time, the child begins to recognize and name his various states with words. The perception of oneself is formed on the basis of the reactions of other people, and above all - the mother. nine0003

Over time, the child begins to recognize and name his various states with words. The perception of oneself is formed on the basis of the reactions of other people, and above all - the mother. nine0003

But a child with autism does not have this opportunity. “His brain receives only a partial image of those who address him,” explains Monika Zilbovicius. For example, he only sees the mouth and cheeks, but not the eyes. As a result, he simply does not have a chance to learn to distinguish between facial expressions of joy, anger, sadness and many other emotions that are an important part of our non-verbal communication.

Most children, by about the age of three, are able to attribute a certain mood to another. The child gradually catches that the thoughts, ideas, desires of others are different from his own, so gradually children begin to communicate and interact with others. Having learned to understand their behavior and desires, they find real pleasure in this interaction. nine0003

Their way of thinking is concrete

Again, a child diagnosed with autism has difficulty understanding emotions. Even when he has a high level of intelligence and uses speech correctly, others still confuse him, sometimes frighten him, and all too often remain incomprehensible.

Even when he has a high level of intelligence and uses speech correctly, others still confuse him, sometimes frighten him, and all too often remain incomprehensible.

14-year-old Ella is doing well in the school curriculum. But it is extremely difficult for her to perceive the jokes of her classmates. “When we talk, we use metaphors, abstract images, we rely on intonation,” explains Christine Hull, clinical psychologist at the Autism Center in Atlanta (USA). “All this escapes the child with autism. For him, a word is just a word. Because the autistic mindset is concrete mindset.” nine0003

Ella sees that others are laughing at her words, but is unable to understand what made them laugh. “Children like Ella are not capable of metaphors, they are not able to understand them spontaneously,” the psychologist adds. - When a child hears that his mother "swallows books", he sees her literally swallowing sheets of paper. It is difficult for him to understand the implicitly expressed, and especially that which makes it so difficult to study at school - abstraction.

What is the cause of autism?

Autism is a congenital disorder of mental development. They can't get sick, and they can't be cured. “For a long time, experts assumed that autism could be the result of psychological trauma received in early childhood, when parents were cold and cruel in their treatment of the child,” says Brian King. - According to another version, vaccines for childhood vaccinations could provoke it. However, neither hypothesis was confirmed." nine0003

The cause of autism in genetic failures, emphasizes the psychiatrist. According to other data, in people with autism, there is a redundancy of neural connections between parts of the brain. As a result, their brains are overloaded and unable to cope with the flow of information. In addition, premature babies weighing less than 2 kg are 5 times more likely to develop autism spectrum disorders than other newborns.

It is difficult for them to learn the rules of behavior

A person with autism who does not "read" the experiences of others also finds it difficult to get others to understand his own feelings. His voice sounds monotonous, without modulations, he can say "thank you very much" in an angry tone that he himself does not feel, he can unwittingly make tactless remarks. nine0003

His voice sounds monotonous, without modulations, he can say "thank you very much" in an angry tone that he himself does not feel, he can unwittingly make tactless remarks. nine0003

Thus, Ella, in front of her other classmates, told her math teacher that she had a “hefty nose”. She didn't mean to offend her at all. But the inability to perceive other people's emotions often causes irritation or even anger.

“For them, living in society is like wandering through a dense forest,” emphasizes Christine Hull. Even people with “high-functioning” autism—those who graduate, work, and live with non-autistics—admit that they constantly feel insecure. “I had to learn by heart how to behave in every situation,” says one of the famous autistic Temple Grandin (Temple Grandin) in the book Opening the Doors of Hope. nine0003

They spend a lot of energy to live among us

One can cite as an example the young Muscovite Svetlana, who has matured and is already working as an engineer, but at 26 she has never learned to look her interlocutors in the eye: “Although no one does not notice, because I have trained to look at the point between the eyebrows when I am talking to a person. Always on the lookout, from a very early age they spend all their energy living among us, adapting to sounds and sights and finally understanding what we say. nine0003

Always on the lookout, from a very early age they spend all their energy living among us, adapting to sounds and sights and finally understanding what we say. nine0003

“Yes, they show empathy deficits, but that doesn't mean they're incapable of feeling emotions,” warns Christine Hull. - They need love, affection, warm relations just like we do. If not more! And he concludes with a smile: “And we must meet them halfway, give each of them the keys that he needs. Don't behave like people with autism towards them."

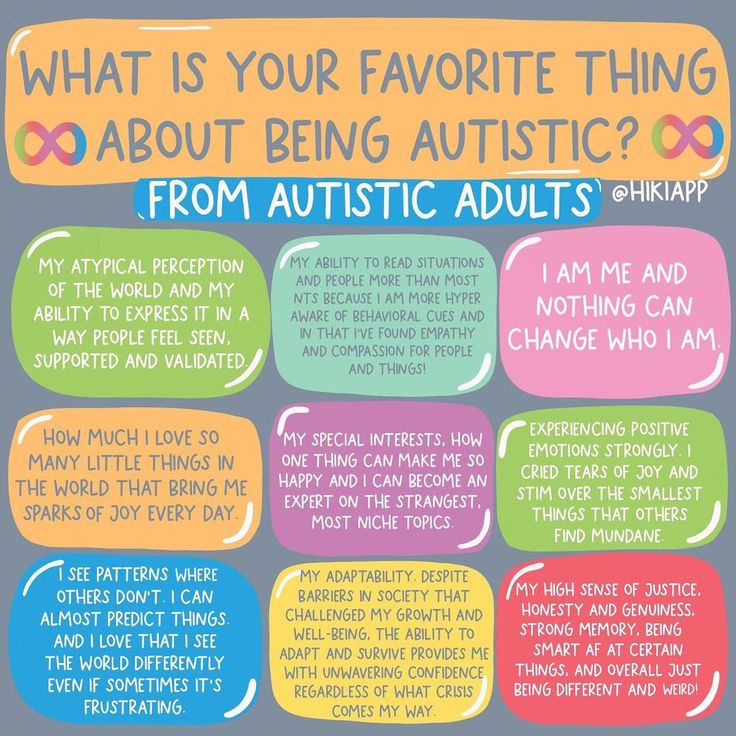

“We are different, but not worse”

Steve Summers, an adult with Asperger's Syndrome, wrote a poignant confession, which is published on the Autismum portal. nine0003

“I'm autistic and I'm tired. Tired of being rejected. Tired of being ignored. Tired of being expelled. Tired of being treated like an outcast. Tired of people who don't understand what autism is. From people who refuse to accept autistic people for who they are. Tired of other people's expectations that I will try and behave "normally". I'm not "normal". I am autistic. Do you want to help us? Listen to autistic people. Put more effort into learning about autism. Accept that we are different, but not worse. Don't try to turn us into a bad copy of your "normal" idea. Accept that it's okay for us to be ourselves. Accept that we are people with the same feelings as everyone else. Please be kind and support us. Please be proactive in communicating with us. We rarely get to step forward after a lifetime of rejection, exclusion, and bullying… I am autistic and I want to be appreciated and accepted for who I am.”

I'm not "normal". I am autistic. Do you want to help us? Listen to autistic people. Put more effort into learning about autism. Accept that we are different, but not worse. Don't try to turn us into a bad copy of your "normal" idea. Accept that it's okay for us to be ourselves. Accept that we are people with the same feelings as everyone else. Please be kind and support us. Please be proactive in communicating with us. We rarely get to step forward after a lifetime of rejection, exclusion, and bullying… I am autistic and I want to be appreciated and accepted for who I am.”

Material prepared with the support of the Naked Heart Foundation, organizer of the II International Forum Every Child Deserves a Family

Text: Galina Chermenskaya Photo source: Getty Images

relations — the answer of scientists

The reverse side of the holidays: why they please not everyone

“Why did you get divorced?”: Russian women named 5 main reasons for divorce

Obscene words, emoticons, lookism: what is wrong with male profiles in sex search applications

How to avoid conflicts with relatives on New Year's Eve: 7 tips from an etiquette expert

"How to overcome shyness when communicating with strangers?"

The psychology of curses: how not to become a victim of dark magic

Olivier and pajamas: how Russian women plan to celebrate the New Year

These images show how autistics see the world

They tend not to look in the face, fixate on a particular action, react faster to multiple stimuli, and have difficulty with social interaction. These are people with autism. nine0003

These are people with autism. nine0003

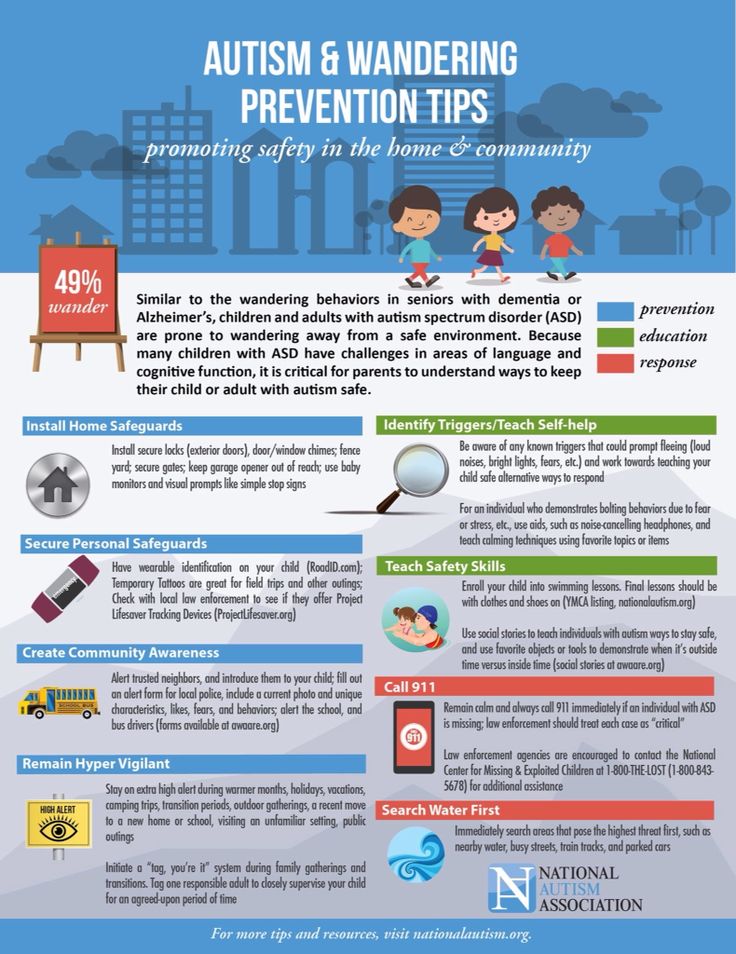

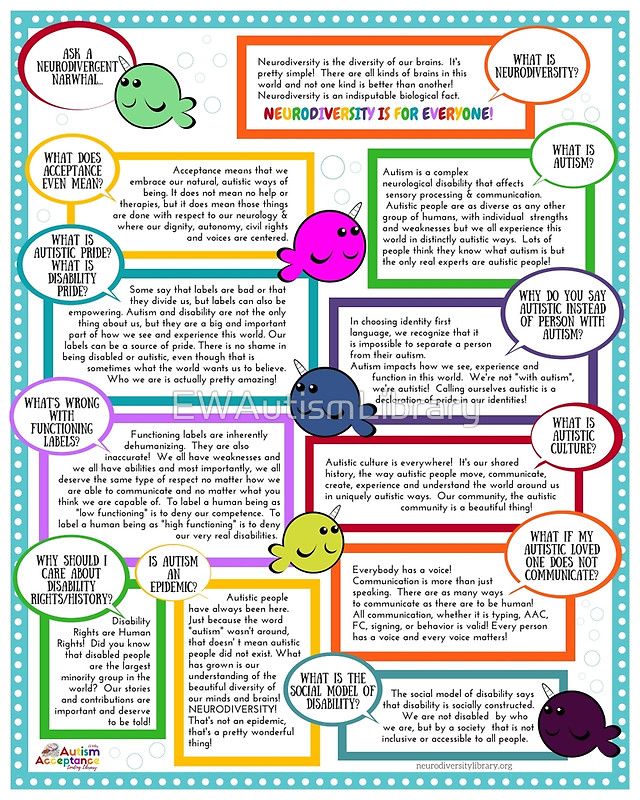

Scientists conduct various tests to determine the causes of the disease and its effective treatment. But this time, the study is designed to help everyone see the world as it appears to people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD/ASD).

The study, published in the October issue of the journal Neuron, involved 39 people. Half of them are officially diagnosed with autism, the other half are "neurotypicals" (those who do not have Asperger's syndrome or other disorders on the autism spectrum, people with Asperger's syndrome are called "neurotypical", in English "neurotypical" or abbreviated NT, although in English the same word is derisively used to refer to persons of average intelligence, from about 80 to 110, that is, ordinary people.) All subjects were shown 700 different images, and sensors that determine the direction of gaze recorded areas that were paid attention to by participants in both groups. nine0003

“Among other findings, our work indicates that things are not so simple. People with autism spectrum disorders not only don't look at faces. They look at most things differently,” study co-author Ralph Adolphs, a neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology, said in a press release.

People with autism spectrum disorders not only don't look at faces. They look at most things differently,” study co-author Ralph Adolphs, a neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology, said in a press release.

The red zones in the images are the most viewed areas, to which the eyes of the subjects constantly rushed.

Images viewed by autistics on the left and neurotypicals on the right. nine0003

According to research, people with autism tend to focus on the center of an image. Even when there are other objects in the frame.

Autistic people look away to the edge of the frame to avoid looking at faces.

Autistics on the left, neurotypicals on the right.

Participants were asked to look at each image for three seconds, so the first instinctive impulse was imprinted in the results.

Autistic people tend not to look at people in photographs, unlike neurotypicals. nine0015

This picture shows how differently attention is distributed among the participants in the experiment in both groups.