Can babies sense anger

Can Babies Sense Stress: From Their Mother?

Our editorial team personally selects each featured product. If you buy something through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission, at no cost to you.

As parents and caregivers, we’ve all experienced it. The “this isn’t what I signed up for” feeling you get when your baby wakes for the third time in the middle of the night and it seems like nothing will soothe them. You’re exhausted, overwhelmed, and just plain stressed.

These feelings, and the accompanying stress, are completely normal, but does that stress response have an affect on your baby?

Our team of experts here at Milk Drunk have done the research for you. We’ll tell you everything you need to know about how babies sense stress, how they respond to it, and what you can do to relieve your own stress response so both you and your baby feel better.

Table of Contents

- Stress as a New Parent

- Can babies sense stress and anxiety?

- Does Your Response to Stress Make a Difference?

- How Do Stress and Anxiety Affect A Baby?

- Three Different Types of Stress

- Signs Your Baby is Stressed or Anxious

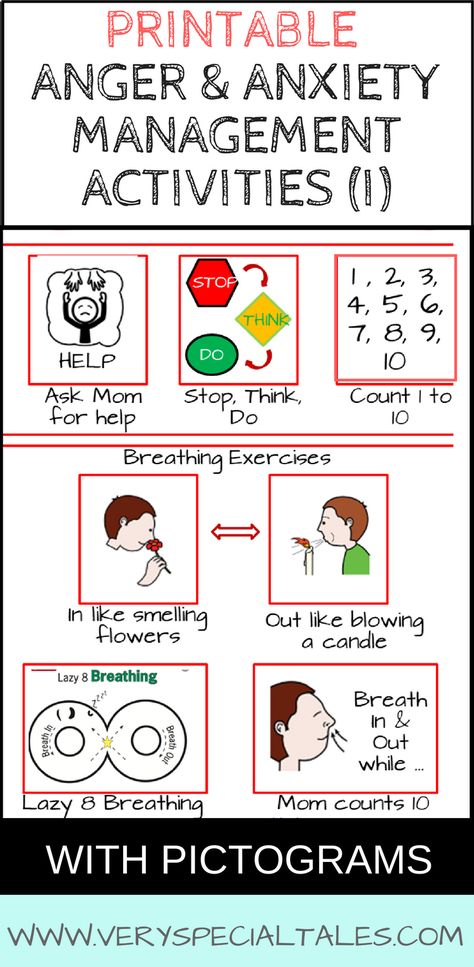

- How Can I Help Prevent or Alleviate My Baby’s Stress?

- How To Cope With Stress and Anxiety as a New Parent

Stress as a New Parent

They’ve only been here a few weeks, but the stress of acclimating to a new baby combined with the rest of your life responsibilities has you stressed to the max.

Whether you’re caring for your child alone or with a partner, or are a caregiver for a newborn, you should know that babies do sense stress and anxiety. Here’s how.

Can babies sense stress and anxiety?

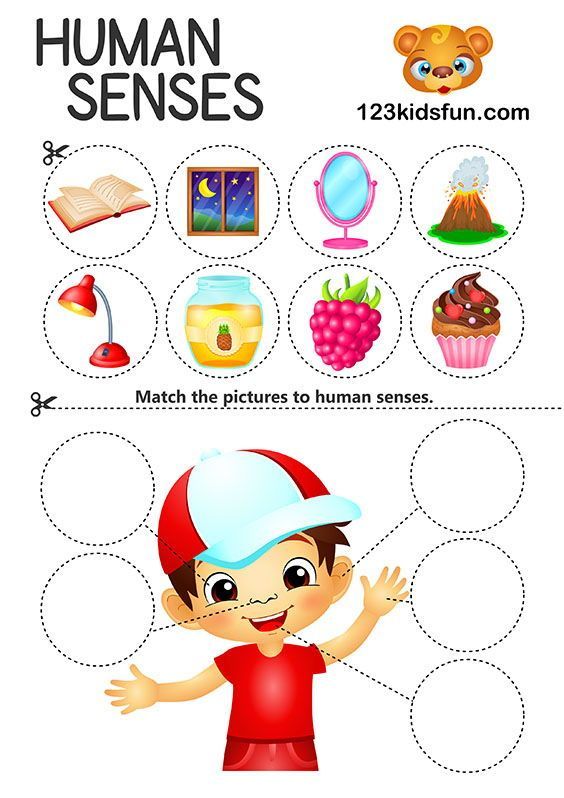

Babies sense stress. While most caregivers and parents tend to think the ability to sense stress only happens later in their child’s life (after a year or so of age), studies show babies can sense their caretaker’s stress as early as three months of age.

Babies, especially young babies, are like sponges, taking in their environment and those in it all day long. Babies are constantly trying to make sense of what they are seeing and hearing around them.

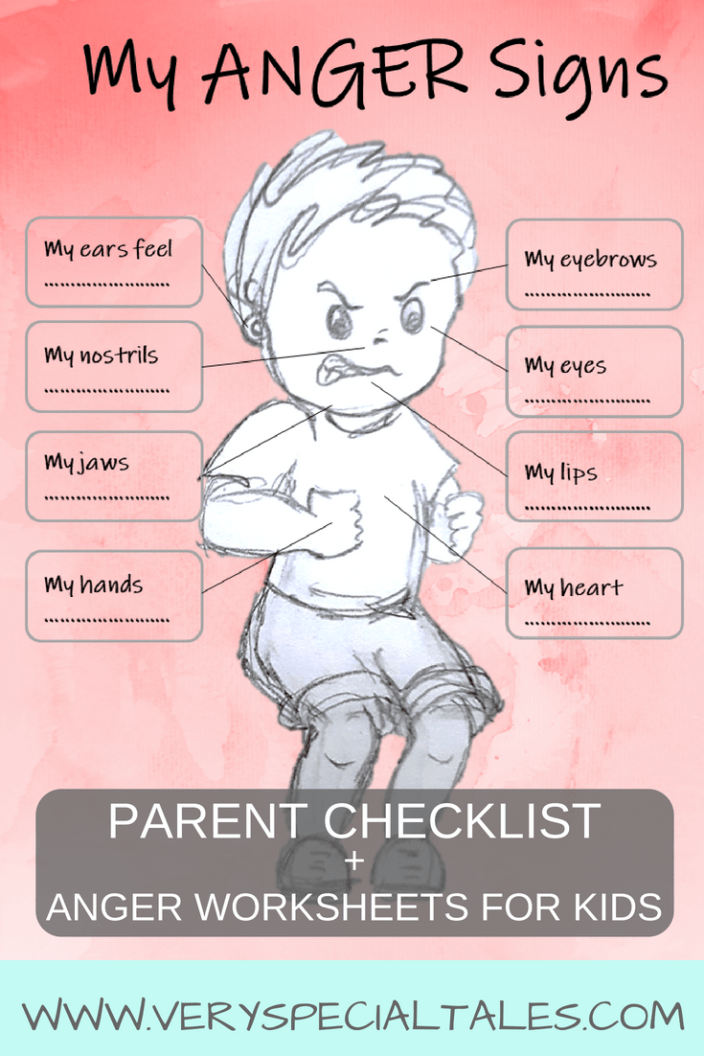

A caregiver’s facial expression or tone of voice can give a baby a pretty good idea of whether they are sad, angry, or happy. In fact, babies are even capable of having these strong feelings (sadness, anger, stress, and anxiety) themselves from as early as three to five months of age.

Does Your Response to Stress Make a Difference?

Yes — when you’re stressed, your baby senses it.

The way you handle your stress determines how your baby will respond to it, too.

Keeping a level head when you’re feeling anxious and stressed will help keep your baby calm, which in turn, can help you feel less stressed.

How Do Stress and Anxiety Affect A Baby?

There are different types of stress, and not all of them are harmful. However, repeated exposure to toxic stress can take a toll not only on you as a caregiver and/or parent, but also on your baby.

Here’s how to determine what you’re feeling, and how your baby can be impacted by those feelings.

Three Different Types of Stress

The CDC categorizes stress into three different types.

- Positive stress. This is low-level anxiety that can make a person slightly nervous but also help them be more productive and even elicits feelings of excitement.

- Tolerable stress. This is slightly more intense than positive stress, yet still manageable.

Think of it like the stress you feel while rushing to try to get to an appointment on time, or waiting for the outcome of a test.

Think of it like the stress you feel while rushing to try to get to an appointment on time, or waiting for the outcome of a test.

- Toxic stress. This level of stress is harmful. It includes intense anxiety, feelings of impending doom, and overwhelming feelings of dread. This type of stress is especially harmful if it is experienced long term.

Babies exposed to high levels of toxic stress have higher levels of cortisol, and are more likely to develop behavioral problems later in life. In some extreme cases, babies exposed to prolonged toxic stress can even have shorter lifespans and altered brain growth.

Exposure to stress can even elevate your baby’s heart rate, and cause cardiac stress. Studies show that when a mother is experiencing an elevated heart rate due to stress, her baby will experience cardiac stress as well.

Knowing the signs of a baby in distress can help you refocus, and regain composure so both you and your baby can feel better.

If you think your baby may be experiencing stress, you can look for some tell-tale signs.

While you might assume crying is the first and foremost sign of stress in a baby, this is not necessarily the case. Crying is a cue, but it isn’t always the only cue or the most prevalent cue.

Here are some signs you might notice in a baby that is experiencing stress:

- No eye contact. Your baby may refuse to make eye contact with you, or simply look away from your direct gaze.

- Sneezing and yawning. If your baby begins sneezing or yawning excessively and it is not likely they are in need of a nap or that they are experiencing an allergy, it could be a stress response.

- Spreading fingers wide. Newborns, especially, tend to hold their hands in fists. If your baby is spreading their fingers wide, it can be indicative of a stress response.

- Does not seem relaxed.

You know your baby better than anyone, and you know when your baby is happy and relaxed. If your baby doesn’t seem relaxed and is displaying behavior that is contrary to her normal behavior, they could be experiencing stress and anxiety.

You know your baby better than anyone, and you know when your baby is happy and relaxed. If your baby doesn’t seem relaxed and is displaying behavior that is contrary to her normal behavior, they could be experiencing stress and anxiety.

Every baby is different, and every baby will respond to stress differently, so this isn’t meant to be an exhaustive list of symptoms.

Ultimately, if you’re stressed and it shows, assume your baby can sense it, too. Then, look for ways to reduce your own stress and anxiety.

How Can I Help Prevent or Alleviate My Baby’s Stress?

You’re going to feel stress, especially adjusting to life with a baby. However, you can learn to manage your stress better.

In the meantime, there are actions you can take to help soothe your baby and alleviate their stress.

Here’s what you can do to calm a baby that is experiencing stress.

- Physical touch.

Offer lots of physical attention but pay attention and learn what your baby likes and how much is too much. A nurturing touch can release oxytocin, the “love hormone,” which has a calming effect on your baby.

Offer lots of physical attention but pay attention and learn what your baby likes and how much is too much. A nurturing touch can release oxytocin, the “love hormone,” which has a calming effect on your baby.

- Communication. Engage with your baby in one-on-one communication. Just like physical touch, calm, friendly talk and reassuring body language can produce a calming effect in babies.

- Walk and move. Hold your baby while moving for the most effective way to calm them — babies LOVE to be carried around while you’re moving! It goes without saying you shouldn’t rock or bounce your baby when you are stressed or angry. The number one trigger for shaken baby syndrome is frustration with a baby’s crying. If you feel angry or frustrated with your baby, place them in a safe place, like their crib, and walk away until you can settle down.

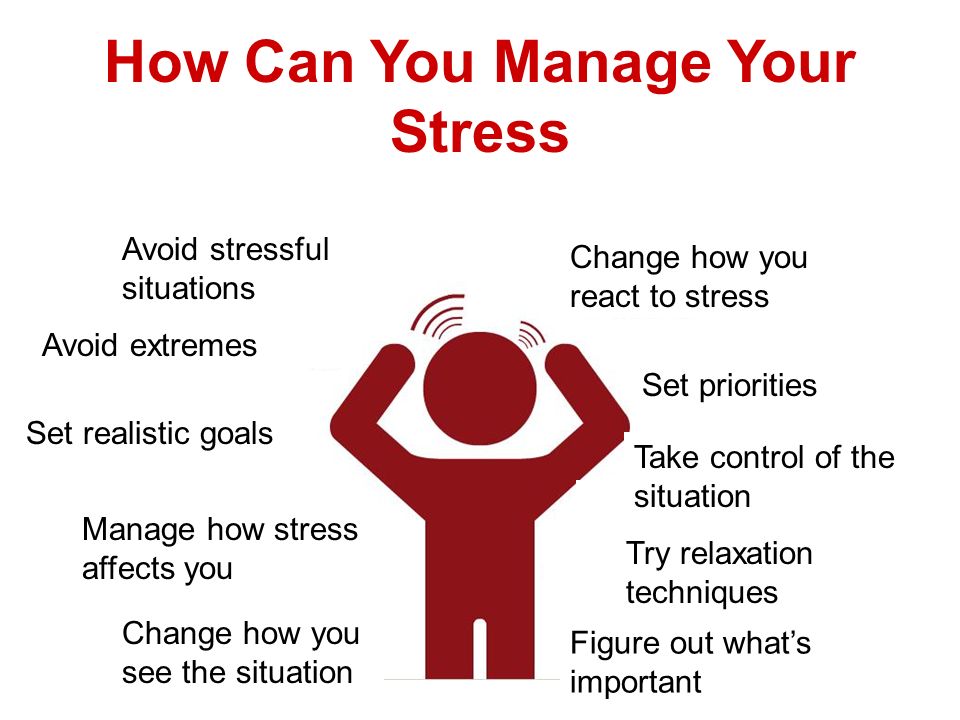

How To Cope With Stress and Anxiety as a New Parent

Becoming a new parent is wonderful and scary at the same time. There are so many changes, and just when you feel you’ve got something “right,” your baby hits a new milestone and all the rules change.

There are so many changes, and just when you feel you’ve got something “right,” your baby hits a new milestone and all the rules change.

Stress and anxiety are a completely normal aspect of parenthood and caregiving. Don’t beat yourself up over it! Just realize it may take a toll on your baby as well as you and/or your partner.

There are steps you can take to lower your stress level and help both you and your baby rest easier.

- Determine the cause of your stress. Parenting and caregiving is overwhelming on its own, but are there outside circumstances making it worse? Do a little digging and try to find out the source of your anxiety.

- Self care is good baby care. The old adage “you can’t pour from an empty cup” is true. To take the best possible care of your baby, you must first take care of yourself. Take a relaxing bath, eat healthfully, schedule in sleep when you can, drink water, avoid excess alcohol, and get in some physical exercise.

Even 30 minutes a day to yourself for a nap or yoga can alleviate stress and make a huge difference in your mental health.

Even 30 minutes a day to yourself for a nap or yoga can alleviate stress and make a huge difference in your mental health.

- Ask for help. It truly takes a village to raise a child, so ask for help when you need it! Turn to someone you trust for support and assistance. Other family members, close friends and neighbors are great ideas for lending a helping hand. If you seem to experience toxic stress frequently, seek professional help from a therapist to help you understand the source of your stress and help you develop healthy ways to cope.

You’ve Got This!

It’s okay to feel overwhelmed and stressed, but learning to cope with stress in a healthy way is a good idea for you and your baby.

Seek out resources to help you manage your stress and always rely on the team at Milk Drunk for support and up to date information on issues like stress, postpartum depression, and other baby-related issues.

Sources:

https://www.zerotothree. org/resources/1709-babies-and-stress-the-facts

org/resources/1709-babies-and-stress-the-facts

https://www.webmd.com/parenting/baby/features/stress-and-your-baby

https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2014/02/111661/stress-contagious-study-shows-babies-can-catch-it-their-mothers

https://www.dontshake.org/

https://www.parentingscience.com/stress-in-babies.html

The content on this site is for informational purposes only and not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Discuss any health or feeding concerns with your infant's pediatrician. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay it based on the content on this page.

Can babies sense stress in others? Yes they can!

© 2018 – 2022 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

Can babies sense stress in the people who care for them? Yes, they can. And babies don’t just detect our tension. They are negatively affected by it. It’s one more reason to look after your own well-being, and calm down before interacting with your child. Here’s what every caregiver needs to know.

Here’s what every caregiver needs to know.

Empathic stress: How just witnessing somebody else’s troubles can raise your cortisol levels

You’ve probably experienced it yourself: Becoming unsettled because someone else is stressed-out.

Is this a superficial reaction? Hardly. In a series of experiments on adults, Veronika Engert and her colleagues discovered they could induce a “full-blown physiological stress response” by merely asking people to watch someone else get stressed.

More than 200 volunteers participated. They took turns sitting in an observation area, watching through a one-way mirror as their domestic partners experienced a moderately stressful social situation — being tested on their mental arithmetic skills for a panel of judges.

For 40% of the study participants, just seeing their partner under this pressure was enough to raise their own levels of the stress hormone, cortisol. And about 10% of the volunteers responded even when the person being tested was a complete stranger (Engert et al 2014).

“The fact that we could actually measure this empathic stress in the form of a significant hormone release was astonishing,” says Engert, “particularly given how tricky it can be to trigger stress-hormone changes in a laboratory setting. If people react like this in a contrived, relatively low-stakes situation, what might they be like in the real world?”

In a subsequent study, Engert and her colleagues found evidence to help answer this question. This time, they didn’t just take cortisol samples in the laboratory. They also collected samples when people were at home. And there was a clear link: Folks who experienced the most “empathic stress” in the lab were the same individuals who showed lots of cortisol synchrony with their partners at home (Engert et al 2018).

But what about babies? How early in life might children experience this “second hand stress?”

Nobody yet has performed the same hormonal test on babies, but Sara Waters and her colleagues have come close. Instead of measuring cortisol levels, they monitored another physiological marker: the changes in heart rate that accompany the stress response.

Instead of measuring cortisol levels, they monitored another physiological marker: the changes in heart rate that accompany the stress response.

The researchers fitted 69 babies (aged 12-14 months) and their mothers with cardiovascular sensors. Then the families were temporarily separated, and the mothers were randomly divided into three groups:

- The “no-stress” group. Mothers in this group were asked to perform a brief, non-stressful task.

- The “low-stress” group. Mothers in this group were asked to deliver a speech in front of a panel of friendly judges — individuals who offered encouraging nonverbal signals as they listened (like smiles).

- The “high-stress” group. Mothers in this group were asked to deliver a speech in front of a panel of disapproving judges. These evaluators responded to the speech with negative nonverbal feedback, like frowns, crossed arms, and disapproving shakes of the head.

After about ten minutes, when the tasks were completed, the mothers were reunited with their babies, and the researchers examined changes in heart function.

What happened?

Not surprisingly, the mothers who showed signs of the most stress were those in the high-stress condition — the women who’d delivered speeches to the disapproving judges. But the interesting thing is that their stress responses were mirrored by their babies.

Infants of mothers in the high-stress condition experienced–within minutes of being reunited — matching changes in heart rate. And this stress contagion effect grew stronger over time.

There was also a measurable behavioral effect. Compared with the babies whose mothers had been assigned to the “no-stress” condition, the babies whose mothers had performed public speaking became more reluctant to interact with strangers (Waters et al 2014).

How exactly did the mothers’ stress get transmitted to their babies?

It’s likely that the infants were responding to information on multiple channels. For example, we know that babies are sensitive to the emotional tone of our voices. (Read more about it in my article, “Better baby communication: Why your baby prefers to hear infant-directed speech.”)

(Read more about it in my article, “Better baby communication: Why your baby prefers to hear infant-directed speech.”)

As I note elsewhere, there is also evidence that babies mirror our brain states when we gaze into their eyes. And it appears that touch is an importand channel too.

Waters and her colleagues tested this possibility in a follow-up study that was much like the first. In this second study, 105 mother-infant pairs experienced brief separations, during which some of the mothers were stressed. But this time, the researchers added a couple of twists.

1. On being reunited with their mothers, some babies were specifically assigned to be held (placed on their mothers’ laps), while other infants were assigned to a “no touch” condition.

Babies in the “no touch” condition were seated in high chairs alongside their mothers, and allowed to interact by sight and sound. But their mothers were under strict orders not to touch the babies.

2. The experiment didn’t end with the mother-infant reunions. Instead, after about 5 minutes of private “together-time,” an adult came into the room.

This adult engaged in “innocuous small talk” with the mother, and then, after several minutes, attempted to play with the baby.

But the identity of the adult varied. If you were a mother who had experienced the “no stress” condition, the adult was a friendly lab assistant. If you were a mother who had experienced the stressful public speaking condition, the adult was one of your judges — one of the people who had thrown you all those disapproving looks.

How did babies respond?

You might expect that the “no touch” policy would be frustrating for the babies, and that seems to have been the case. For example, during the first few minutes after being reunited, babies in the “no touch” condition were more likely to share their mothers’ physiological distress.

But for families in the stressed condition, everything changed after that adult judge came into the room. The mothers’ physiological stress levels increased, and the babies seemed to notice — if they were sitting on their mothers’ laps.

The mothers’ physiological stress levels increased, and the babies seemed to notice — if they were sitting on their mothers’ laps.

The babies being held by their mothers became ever-more likely to mirror their mothers’ physiological stress responses. The babies in the no-touch condition did not (Waters et al 2017).

It’s as if physical touch were a high fidelity cable – a conduit allowing for the efficient transfer of contagious stress. Without this tactile connection, the babies were less likely to track their mothers’ physiological reactions.

This really shouldn’t surprise us. Not if we think about the evolutionary importance of stress contagion.

A wide variety of mammals, birds – even fish – learn about fear through social observation (Manassa and McCormic 2012). These animals don’t wait to get bitten before deciding that a predator is scary. They notice the others react with alarm, and take a hint.

And experiments indicate that many creatures experience feelings of empathy for others. Meticulous experiments on rodents show that you can cause a cortisol spike by merely exposing an animal to a social partner who was recently stressed (Carnevali et al 2020). Rats act agitated or distressed when they see other creatures in pain (Langford et al 2006). Juvenile mice have shown lasting, despair-like behavior after witnessing their mothers in a stressful situation (Warren et al 2020).

Meticulous experiments on rodents show that you can cause a cortisol spike by merely exposing an animal to a social partner who was recently stressed (Carnevali et al 2020). Rats act agitated or distressed when they see other creatures in pain (Langford et al 2006). Juvenile mice have shown lasting, despair-like behavior after witnessing their mothers in a stressful situation (Warren et al 2020).

Should we assume lesser abilities from our own children? The brain of a human newborn is massive compared with that of a mouse. At birth, babies are already attuned to social information, and within a few weeks they may become savvy enough to notice — and be disturbed by — the sight of apathetic, unresponsive faces.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that babies can read your every thought. Nor does it mean that we’ll cause lasting harm if we sometimes pick up our babies while we are feeling upset. But babies are far from clueless. They are sensitive to our emotional states. As I note elsewhere, there is evidence that long-term exposure to second-hand stress — like the angry squabbling of adult domestic partners — can alter the development of a baby’s stress response system (Towe-Goodman et al 2012; Graham et al 2013).

So reducing our own stress levels isn’t just good for our health. It’s good for our babies, too. Before we interact with our babies, we should take a moment to calm ourselves down.

For tips on handling stress, see these Parenting Science articles:

- Stress in babies: How to keep babies calm, happy, and emotionally healthy

- Parenting stress: 10 evidence-based tips for making life better

References: Can babies sense stress?

Carnevali L, Montano N, Tobaldini E, Thayer JF, Sgoifo A. 2020. The contagion of social defeat stress: Insights from rodent studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 111:12-18.

Engert V, Plessow F, Miller R, Kirschbaum C, and Singer T. 2014. Cortisol increase in empathic stress is modulated by social closeness and observation modality. Psychoneuroendocrinology 45: 192-201.

Engert V, Ragsdale AM, Singer T. 2018. Cortisol stress resonance in the laboratory is associated with inter-couple diurnal cortisol covariation in daily life. Horm Behav. 98:183-190.

Horm Behav. 98:183-190.

Graham AM, Fisher PA, and Pfeifer JH. 2012. What sleeping babies hear: a functional MRI study of interparental conflict and infants’ emotion processing. Psychological Science 24(5):782-789.

Langford DJ, Crager SE, Shehzad Z, Smith SB, Sotocinal SG, Levenstadt JS, Chanda ML, Levitin DJ, and Mogil JS. 2006. Social Modulation of Pain as Evidence for Empathy in Mice. Science. 312(5782):1967-70.

Manassa RP, McCormick MI. 2012. Social learning and acquired recognition of a predator by a marine fish. Anim Cogn. 15(4):559-65.

Towe-Goodman NR, Stifter CA, Mills-Koonce WR, Granger DA and Family Life Project Key Investigators. 2012. Interparental aggression and infant patterns of adrenocortical and behavioral stress responses. Dev Psychobiol. 54(7):685-99.

Warren BL, Mazei-Robison MS, Robison AJ, Iñiguez SD. 2020. Can I Get a Witness? Using Vicarious Defeat Stress to Study Mood-Related Illnesses in Traditionally Understudied Populations. Biol Psychiatry 88(5):381-391.

Waters SF, West TV, Mendes WB. 2014. Stress contagion: physiological covariation between mothers and infants. Psychol Sci. 25(4):934-42.

Waters SF, West TV, Karnilowicz HR, Mendes WB. 2017. Affect contagion between mothers and infants: Examining valence and touch. J Exp Psychol Gen. 146(7):1043-1051.

A few paragraphs in this article, “Can babies sense stress?” appeared previously in a post for BabyCenter, entitled “You’re baby knows, and feels, when you’re stressed” (2014).

Content last modified 4/2022

image of infant looking out of window by istock / iEverest

Helping Toddlers Understand Their Emotions - Child Development

Not so long ago, there was a common belief that young children, until they reach the age of two, until they start talking, are almost nothing as individuals, think almost nothing and do not experience any feelings. The very idea that a six-month-old baby could feel fear or anger, sadness or grief, sounded ridiculous. But thanks to the boom in early life psychology research over the past thirty years, we know that babies and toddlers are deeply sentient beings. nine0003

nine0003

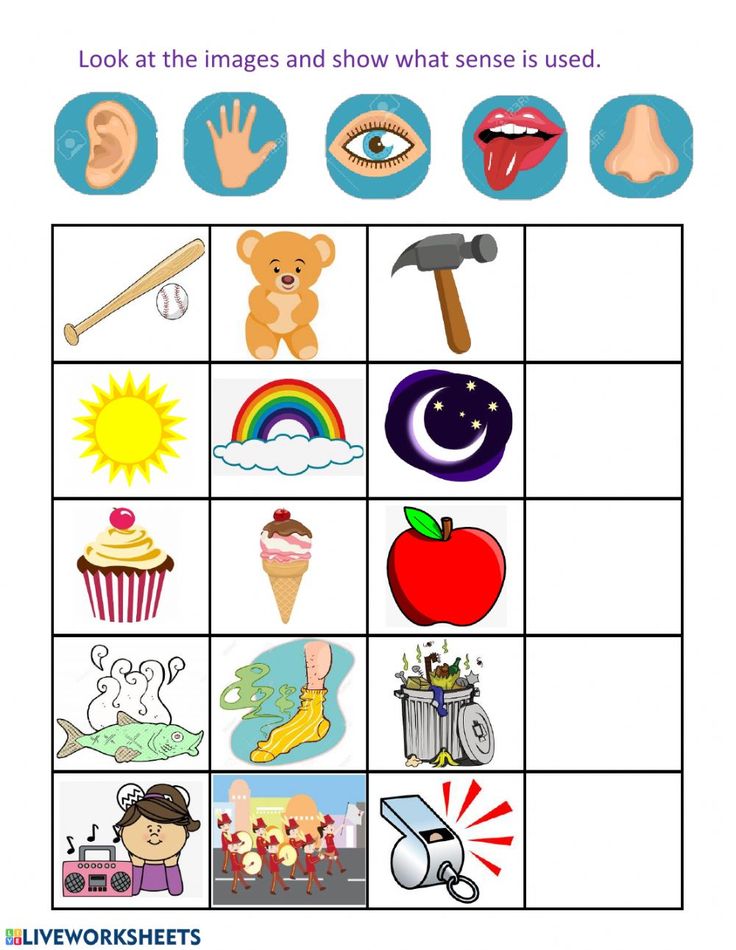

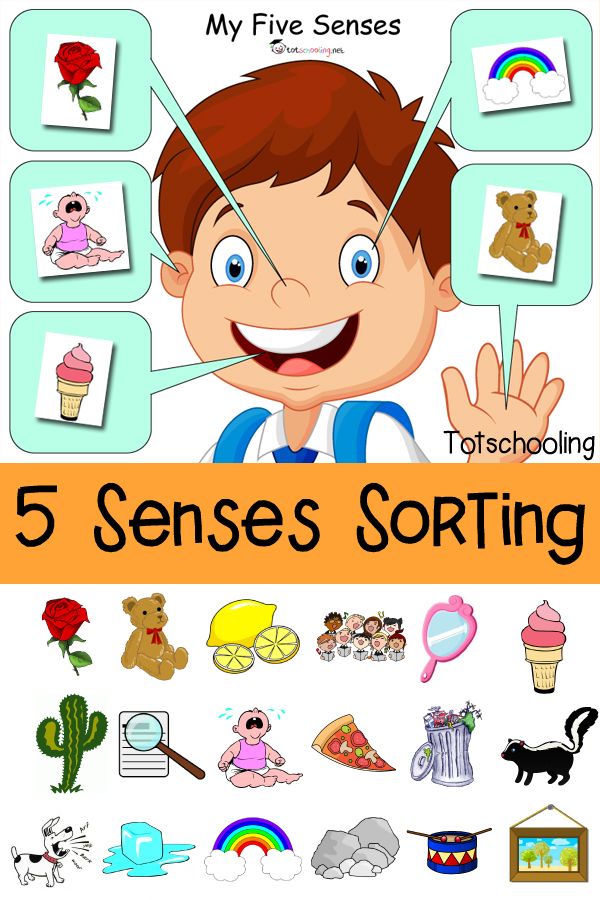

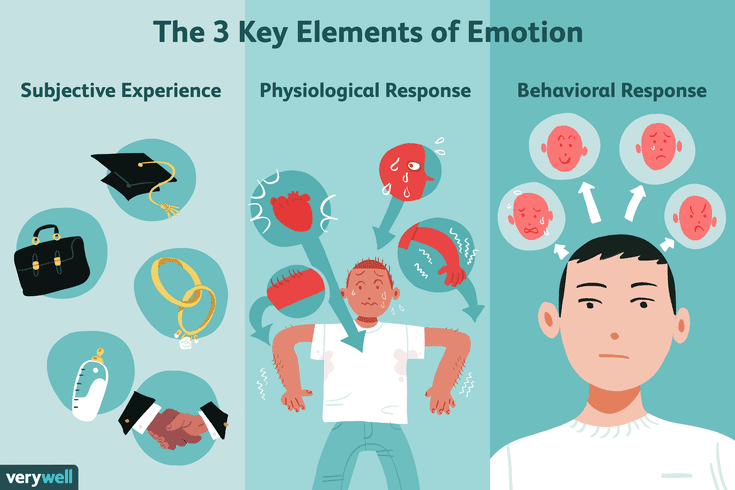

From the very first months of life, long before they begin to use words to express themselves, children experience peaks of joy, excitement and delight. They also feel fear, grief, sadness, hopelessness and anger - emotions that many adults still find impossible for toddlers. Research has also shown that children's ability to effectively manage their full range of emotions (i.e., self-regulation) is one of the most important success factors in school, work, and personal relationships over the long term. nine0003

Therefore, it is very important to help the child learn to cope with his feelings, not to be afraid, but to accept them, and all without exception. Feelings are not right or wrong, they just are. Sadness and joy, anger and love can coexist and are part of the full range of emotions children experience. By helping your child understand his feelings, you give him the tools to effectively manage himself.

The main obstacle for parents in trying to help their baby is that they often start with the assumption that a truly happy child is always happy. But, in order for the baby to develop strength and resilience, he needs to go through difficult trials, win the fight and cope with sadness and sadness. Ultimately, this brings children a sense of contentment and well-being. nine0003

But, in order for the baby to develop strength and resilience, he needs to go through difficult trials, win the fight and cope with sadness and sadness. Ultimately, this brings children a sense of contentment and well-being. nine0003

What can parents do?

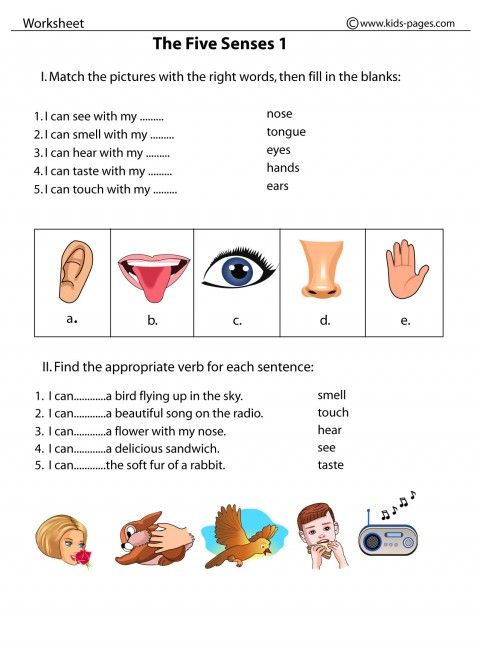

- Starting from the very first months of life, learn to recognize their cues - the sounds they make, facial expressions and gestures - and respond sensitively to them. Your reaction will let the child know that you understand his feelings and they are very important to you. For example, this may mean that you should stop tickling a four-month-old baby as soon as he begins to arch his back and turn away from you. After all, in this way he signals to you that he needs a break. Also, do not bring a nine-month-old child to the window to wave to his mother if he is sad that she has gone to work. nine0018

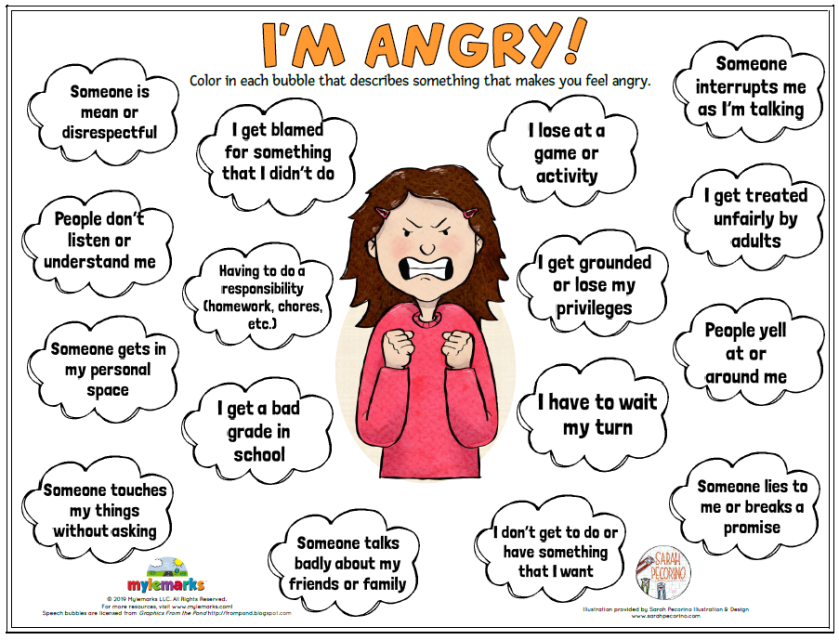

- Recognize and name emotions and help your baby deal with them. Emotions such as anger, sadness, frustration and disappointment can overwhelm the baby.

Calling them by their proper names will help children learn to identify them and understand that these feelings are normal. This means acknowledging that a one and a half year old is angry about having to leave the playground, while a two year old is annoyed that his tower of bricks is constantly falling, and a three year old is sad that his grandmother and grandfather is leaving. nine0018

Calling them by their proper names will help children learn to identify them and understand that these feelings are normal. This means acknowledging that a one and a half year old is angry about having to leave the playground, while a two year old is annoyed that his tower of bricks is constantly falling, and a three year old is sad that his grandmother and grandfather is leaving. nine0018 - Do not be afraid of feelings, they are not the problem. The problem is what we do or don't do with them. Listen openly and calmly as your child shares difficult experiences with you. When you ask a child about his feelings and acknowledge their presence, you let the baby know that his emotions are very valuable and important to you. Recognizing and identifying feelings is the first step towards managing them in a healthy and acceptable way.

- Avoid minimizing feelings or dissuading children of their feelings. nine0012 The natural reaction of parents is to want the child to calm down as soon as possible so that all his negative feelings and emotions go away as soon as possible.

"Do not be sad. You will see your friend another time." But the feelings do not go away, children need to express them in one way or another. Recognizing strong, deep feelings helps the child learn to manage them. “You are sad because your friend needs to go home. You love to play with him so much. Let's go to the window, wave goodbye to him and plan a new meeting with him in the near future. When feelings are minimized or ignored, children often express them through aggressive words and actions or hide them in themselves, which can eventually lead to the development of anxiety or depression. nine0018

"Do not be sad. You will see your friend another time." But the feelings do not go away, children need to express them in one way or another. Recognizing strong, deep feelings helps the child learn to manage them. “You are sad because your friend needs to go home. You love to play with him so much. Let's go to the window, wave goodbye to him and plan a new meeting with him in the near future. When feelings are minimized or ignored, children often express them through aggressive words and actions or hide them in themselves, which can eventually lead to the development of anxiety or depression. nine0018 - Teach children how to deal with their feelings. If a one and a half year old baby is angry that play time is over, advise him to stamp his foot with all his strength or draw on paper with a red pencil how angry he is. Help a 2-year-old who is frustrated about not being able to hit the basket with a ball to come up with some other ways to solve the problem. Take your three-year-old child to a new kindergarten in advance if he is afraid of such an innovation in his life.

Introduce him to the group and caregivers, let him play on the playground, and thus the unfamiliar environment will become familiar. nine0018

Introduce him to the group and caregivers, let him play on the playground, and thus the unfamiliar environment will become familiar. nine0018 - Teach children how to deal with their feelings. If a one and a half year old baby is angry that play time is over, advise him to stamp his foot with all his strength or draw on paper with a red pencil how angry he is. Help a 2-year-old who is frustrated about not being able to hit the basket with a ball to come up with some other ways to solve the problem. Take your three-year-old child to a new kindergarten in advance if he is afraid of such an innovation in his life.

Our children's emotional responses often trigger our own emotional responses, which need to be disposed of and anything that could cause the child's suffering to be smoothed out. It is very important for parents to be able to manage their own emotions and avoid the temptation to react violently, otherwise they will simply miss the opportunity to help children learn effective skills for managing feelings and emotions.

View your child's experience as an opportunity to teach him to identify and manage his emotions, positive and negative, and this will certainly add depth and brightness to his life. Demonstrate to your child that in a full and multifaceted life there are both ups and downs, and this is absolutely natural. Feelings are not "good" or "bad" - they just are. Remember that in moments of joy and in the struggle with difficulties, you are the true leader for your child. And this guide starts from the first day of your baby's life. nine0003

And this guide starts from the first day of your baby's life. nine0003

Let him be angry! When anger is good for a child

Photos: Depositphotos / Illustration: Yulia Zamzhitskaya

Faced with children's anger or destructive behavior, parents and teachers often get lost. From generation to generation, attitudes are passed on: “you can’t be rude to your elders”, “fighting is bad”, “shouting loudly is indecent”. But sometimes it is simply necessary to give vent to negative emotions. In what cases anger and anger are useful for a child, we deal with a psychologist Irina Lagunina .

Anger is born together with a child

Experts observe the first manifestations of anger already in newborns. For example, when a child reacts with loud crying to the lack of milk. The fact is that the nervous system is formed even before birth.

“One child is born more calm, the other less. If a mother during pregnancy had a high level of cortisol, a stress hormone, the baby will be more sensitive and, accordingly, more prone to expressing emotions, including anger, ”says the expert.

nine0003

Growing up, the child feels the psychological background in the family and builds an emotional life in accordance with the situation:

“If a boy or girl grows up with parents who have a lot of aggression, but they constantly suppress it, it will be difficult for them to learn to cope with emotions. The same thing happens with mental retardation, or the so-called minimal brain dysfunction, when the frontal lobes, which are responsible for controlling emotions, remain undeveloped for a long time. nine0003

Evolution left man only those properties and qualities that are necessary for survival. Including basic emotions , one of which is anger. It is no coincidence that Anger is one of the main characters in the Oscar-winning cartoon "Inside Out", where five emotions live in the head of the girl Riley and react to all the events of her life.

The emotion of anger performs two important functions :

- Helps to destroy the enemy in case of threat.

nine0018

nine0018 - Helps to remove the obstacle on the way to the desired resource.

A resource for a child is both toys and parental love and attention. The child's psyche gives out a basic, natural reaction in response to the lack or inability to get what they want. After all, this is the only force in the child's arsenal that can help correct the situation this very second.

“That is why, for example, a child reacts so violently to punishment or restriction of freedom. It's always a reason to be angry," says Irina Lagunina .

Where is the limit of adequate anger

Psychologists agree that it is more useful to show anger than to suppress it. It is suppressed anger that is one of the most common causes of psychosomatic illnesses.

Anger as a reaction to danger or resource constraints is a normal and useful emotion. But it is important to separate the emotion itself and the forms of its manifestation. As long as the child does not violate other people's boundaries, anger is adequate.

As long as the child does not violate other people's boundaries, anger is adequate.

Irina Lagunina :

“Most often, anger is manifested verbally — that is, the child screams, is indignant. Or it is expressed in motor activity: the baby can jump up, stomp his feet, wave his arms, bang his fist on the table, even fight in case of a threat. Speaking or shouting your anger, adding physicality to this is a completely normal story. ”

If, during anger, a child falls into uncontrolled aggression, strikes first without the slightest threat to himself, insults the opponent - such anger should not be encouraged. For parents and teachers, this is a signal that he needs help. nine0003

“I would suggest that adults not worry too much about childish anger. But, if the child is very irritable or aggressive, there is definitely a reason for this, and it needs to be found. There may be problems of a psychological or neurological nature.

Sometimes it makes sense to involve a specialist in order to figure out what is happening to the child.”

Teachers' Council - a community for those who teach and study . Professionals grow with us. nine0003

Do you want to keep up with the world and trends, be the first to learn about new approaches, methods, learn how to apply them in practice, or even undergo retraining and master a new specialty? Everything is possible in our Training Center.

There are already more than 40 online retraining and additional education courses on our platform.

See

Five Circumstances in which a Child Needs Anger

As a child grows up, he encounters circumstances in which adequately expressed anger plays an important role and really helps the child. nine0003

- Trouble call .

It happens that children find themselves in a difficult or even dangerous situation just because they could not scream and call for help in time. Showing anger in an extreme situation sometimes means saving your life and health.

Showing anger in an extreme situation sometimes means saving your life and health.

- Self defense .

Children who are forbidden to express anger show a high level of victimization — a tendency to become a victim of a crime. They are not able to defend themselves, to say “no”, therefore they become victims of physical and emotional abuse. The manifestation of anger helps the child to fight back the aggressor. nine0003

- Energy of achievements .

Anger can be transformed into useful energy, especially in a highly competitive environment such as sports. If adequate anger is forbidden to a child, he will be less competitive.

- Defending borders .

If toys are always taken from a child, they are pushed, hurt, and an adult forbids getting angry with the words “share the toy, you are not greedy”, “don’t cry, you are a boy”, “how can you fight!” - the baby finds himself in a situation of powerlessness, because he cannot protect what is important to him. This has a negative impact on later life. nine0003

This has a negative impact on later life. nine0003

- Manifestation .

Suppressed anger coexists with fear. A child who is forbidden a basic emotion is afraid to express himself in principle. In the future, he may have difficulties with self-realization.

To allow a child to be angry means to accept him completely, with all his manifestations, and to broadcast the simple thought that everything is all right with him.

Anger as a way to develop fine motor skills

If there are no signs of aggression towards others or deviant behavior in the child's destructive actions, they are useful. So, many "angry" actions develop fine motor skills, and hence cognitive abilities, speech. Useful:

- tear paper;

- drumming your fingers loudly on the table;

- something crumpled in the palms.

At an early age, for proper development, the baby needs to go through the stage of destruction: he disassembles the pyramids, destroys the sandcastles built by himself and other children, dismantles the designers, breaks toys. This is necessary in order to find out the structure of the objects of the surrounding world, to get acquainted with the concept of the part and the whole, with one's emotional and physical abilities. nine0003

This is necessary in order to find out the structure of the objects of the surrounding world, to get acquainted with the concept of the part and the whole, with one's emotional and physical abilities. nine0003

It is especially useful if, after satisfying the need for destruction, the parent or teacher, together with the child, restore the spoiled — collect the pyramid and scattered toys, scraps of paper. This will help build emotional intelligence.

Directing anger in the right direction

Irina Lagunina advises reinforcing adequate manifestations of childish anger, because during preschool and primary school age a child learns to be angry correctly. Good ways to serve:

- Personal example .

Through the personal example of significant adults, children learn faster than through instruction. If parents are used to suppressing strong emotions, the child copies their behavior, or gives out excessive aggression, because he does not see a model for the correct handling of emotions.

- Monitoring the psychological background in the family .

The atmosphere in which a child grows up serves to shape his emotional life. If there is a lot of anger at home, relatives constantly come into conflict with each other, the baby will accept this behavior as the norm and will show anger even where it is inadequate to the situation. nine0003

- Discuss what happened .

It is important to talk to the child not only about what actually happened, but also about the feelings that arose about it. Adequate emotions - to encourage, inadequate - to track and try to eliminate.

The expert emphasizes that children should not be required to be aware of their emotions. The main thing is to remember that safety and health are more important than exemplary behavior. And in order to develop in children the ability to adequately express the full range of normal emotions, including anger, it is important to first develop this ability in adults themselves.