C section timing

C-sections - everything you need to know

Tommy's PregnancyHub

A caesarean section (c-section) may be planned or unplanned. Find out why you may need a c-section and what to do if you would like to have one.

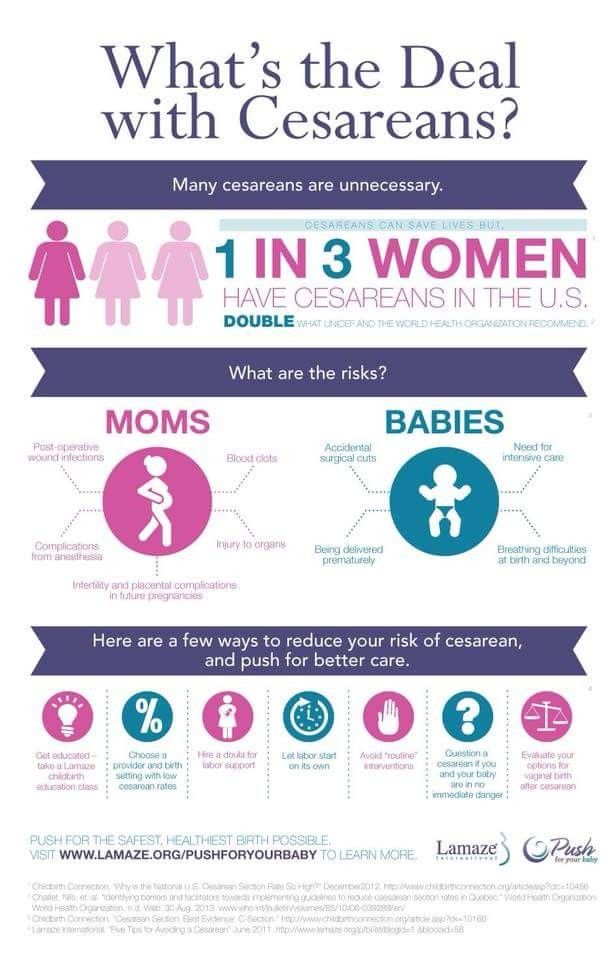

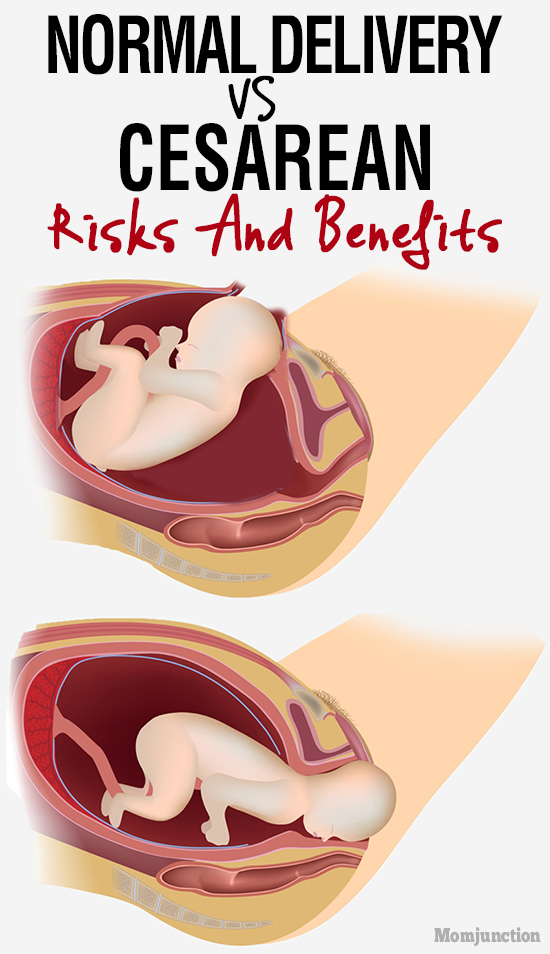

A caesarean section (c-section) is an operation to deliver your baby. A doctor makes a cut just below your bikini line, through your abdomen and womb, and lifts your baby out through it.

You may have a planned (elective) c-section if you know you will need a c-section before you go into labour.

You may have an unplanned (emergency) c-section if this is the safest way to deliver your baby.

About 1 in 4 women who give birth in the UK have a c-section. Most of these are emergency c-sections.

What is a planned c-section?

Sometimes, a c-section may be safer for you or your baby than a vaginal birth. For example, your doctor or midwife may offer you a planned c-section if:

- there are problems with the placenta, such as a low-lying placenta (placenta praevia)

- your baby is lying in a difficult position for labour, such as bottom down (breech)

- you are expecting twins who share a placenta or if either baby is lying in a difficult position for labour

- you are expecting more than 2 babies.

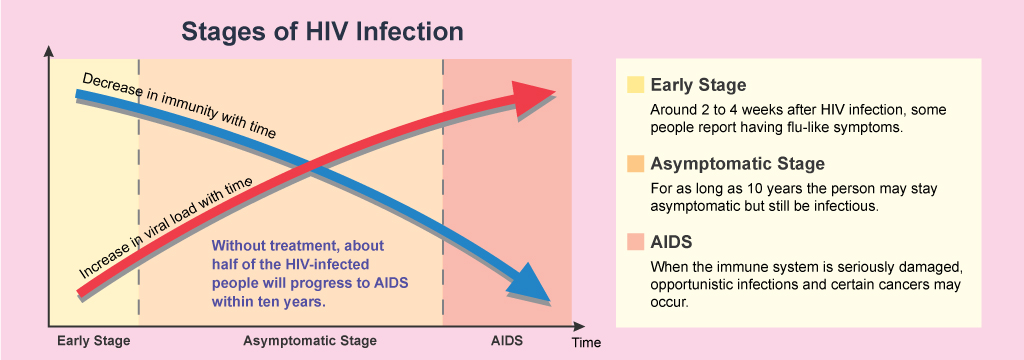

If you have HIV or genital herpes, your doctor will explain your birth options. Some women may need a c-section to reduce the risk of passing the virus to the baby.

“Don’t be afraid to ask your consultant for more information. I wasn’t well informed about my placenta praevia and unfortunately was one of the small minority of women whose placenta haemorrhages. I felt this wasn’t clearly explained enough as a risk and I could have been better prepared.”

Emily

If you are offered a c-section because of medical reasons, it is your choice whether to have one or not. You do not have to have one if you don’t want one.

You may want to have a c-section, even if there’s no medical need. Read more about your options for giving birth.

If you decide to have a planned c-section, you will see an obstetrician. This is a doctor who specialises in care during pregnancy, labour and after birth. They will explain the benefits and risks of a c-section and your other birth options. You will also see a midwife at your antenatal appointments where you can discuss your options.

You will also see a midwife at your antenatal appointments where you can discuss your options.

You will usually have a planned c-section at 39 weeks of pregnancy. The aim is to do the c-section before you go into labour. Babies born earlier than 39 weeks are more likely to need help with their breathing. Sometimes there’s a medical reason for delivering the baby earlier than this. For example, if you’re expecting more than 1 baby.

What is an emergency c-section?

You may have an unplanned emergency c-section if your baby needs to be delivered quickly. This may happen if your labour is not progressing or there’s any concern about your or your baby’s wellbeing.

The word ‘emergency’ makes it sound rushed, but there’s often time to decide whether you want a c-section. Your doctor and midwife will explain what your options are. If your or your baby’s health is at risk, you may need to have a c-section more quickly.

"Everything I had ever heard about c-sections had been negative and scary.

So, when I was told I needed an emergency c-section, I was very anxious. But it went well and I had a good experience, which I hadn’t thought was possible."

C-section myths

There’s no strong evidence that any of these things affect your chances of needing a c-section:

- walking around during labour

- not lying on your back during labour

- being in water during labour

- drinking raspberry leaf tea

- the midwife or doctor breaking your waters early

- having an epidural.

There is no evidence that your height or the size of your baby can predict whether you will need a c-section. Being short or having a small pelvis or small feet does not affect whether you can have a vaginal birth. But you may be more likely to have a c-section if you’re overweight or over the age of 40.

You may be less likely to have a c-section if you:

- give birth in a midwife-led unit, or

- have continuous support during labour from a midwife or someone trained to support you, such as a doula.

Read about what happens during a c-section.

Read about preparing for a c-section.

Read about your options for giving birth.

Review dates

Reviewed: 16 July 2021 | Next review: 16 July 2024

Tags

- Mum

- Dad

- Singleton

- Multiple

- During pregnancy

Back to top

Health implications resulting from the timing of elective cesarean delivery

- Journal List

- Reprod Biol Endocrinol

- v.8; 2010

- PMC2902487

Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010; 8: 68.

2010; 8: 68.

Published online 2010 Jun 21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-68

1 and 1

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Background

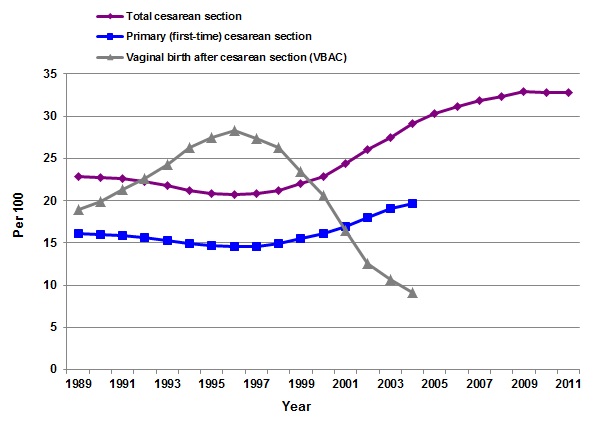

The literature is nearly unanimous in recommending elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks of gestation because of the lower rates of neonatal respiratory complications compared to 38 weeks. However, elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or more may have maternal and other fetal consequences compared to delivery at 38 weeks, which are not always addressed in these studies.

Discussion

Between 38 and 39 weeks of gestation, approximately 10% - 14% of women go into spontaneous labor; meaning that a considerable number of women scheduled for an elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks will deliver earlier in an unscheduled, frequently emergency, cesarean delivery. The incidence of maternal morbidity and mortality is higher among women undergoing non-elective cesarean deliveries than among those undergoing elective ones. Complications may be greater among women after numerous repeat cesarean deliveries and among older women. Other than reducing the frequency of non-elective cesarean deliveries, bringing forward the timing of elective cesarean delivery to 38 weeks, may occasionally prevent intrauterine fetal demise which has been shown to increase with increasing gestational age and to avoid other fetal consequences related to the emergency delivery. All these considerations need to be weighed against the medical and the economic impact of the increase in neonatal morbidity resulting from births at 38 weeks compared to 39 weeks.

Complications may be greater among women after numerous repeat cesarean deliveries and among older women. Other than reducing the frequency of non-elective cesarean deliveries, bringing forward the timing of elective cesarean delivery to 38 weeks, may occasionally prevent intrauterine fetal demise which has been shown to increase with increasing gestational age and to avoid other fetal consequences related to the emergency delivery. All these considerations need to be weighed against the medical and the economic impact of the increase in neonatal morbidity resulting from births at 38 weeks compared to 39 weeks.

Summary

Until prospective randomized trials are conducted, we are unlikely to be able to precisely answer all risk:benefit questions as to the best timing of scheduled elective cesarean delivery. Older women, and women with numerous prior cesarean deliveries, are of particular concern. It is reasonable to inform the pregnant women of the risk of each of the above options and to respect her autonomy and decision-making.

The literature is nearly unanimous in recommending elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks of gestation because of lower rates of neonatal respiratory complications compared to 38 weeks. However, elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or more may have maternal and other fetal consequences compared to delivery at 38 weeks, which are not always addressed in these studies. Delaying delivery for an additional week increases the time that the woman and her fetus is vulnerable to a number of unexpected complications and increases the proportion of women who will deliver by non-elective cesarean delivery rather than an elective one.

The outcome of this particular group of women is less addressed in the literature when discussing the advantages of elective cesarean deliveries since the majority of published studies on elective cesarean delivery exclude from statistical analysis women who delivered non-electively before the scheduled date of delivery. Other studies combined this cohort of patients with those that delivered electively so that it is impossible to isolate the contribution of non-elective delivery to the outcome. A design centered on the actual delivery route will allow investigators to distinguish between labored and unlabored cesarean deliveries. In studies limited to unlabored cesareans, women who present in labor before their scheduled date of delivery are, by definition, excluded. Excluding these women may overestimate potential benefits and also potential harms because the studies then cannot account for any effect that labor has on outcomes of interest. Landon et al [1] investigated maternal and perinatal outcomes among women who underwent an elective repeat cesarean delivery. Women who were designated for an elective cesarean delivery but presented in early labor were excluded from the study. The authors stated that exclusion from the study of women who presented in early labor and subsequently underwent repeated cesarean delivery probably lowered the risk of complications in the group of women undergoing elective repeated cesarean delivery [1].

A design centered on the actual delivery route will allow investigators to distinguish between labored and unlabored cesarean deliveries. In studies limited to unlabored cesareans, women who present in labor before their scheduled date of delivery are, by definition, excluded. Excluding these women may overestimate potential benefits and also potential harms because the studies then cannot account for any effect that labor has on outcomes of interest. Landon et al [1] investigated maternal and perinatal outcomes among women who underwent an elective repeat cesarean delivery. Women who were designated for an elective cesarean delivery but presented in early labor were excluded from the study. The authors stated that exclusion from the study of women who presented in early labor and subsequently underwent repeated cesarean delivery probably lowered the risk of complications in the group of women undergoing elective repeated cesarean delivery [1].

Thomas et al reported that 10% of women go into spontaneous labor between 38 and 39 weeks of gestation [2]. Obstetrical data from 25,533 women delivered between the years 2003 to 2008 in our delivery ward (Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, HaEmek Medical Center in Afula, Israel, a university teaching hospital) revealed that 14% of ongoing pregnancies went into spontaneous labor between 38 to 39 weeks (unpublished data). The meaning of these numbers is that over 10% of elective cesarean deliveries scheduled to 39 weeks will likely convert to non-elective ones between 38 to 39 weeks.

Obstetrical data from 25,533 women delivered between the years 2003 to 2008 in our delivery ward (Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, HaEmek Medical Center in Afula, Israel, a university teaching hospital) revealed that 14% of ongoing pregnancies went into spontaneous labor between 38 to 39 weeks (unpublished data). The meaning of these numbers is that over 10% of elective cesarean deliveries scheduled to 39 weeks will likely convert to non-elective ones between 38 to 39 weeks.

A search of PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases up to December 2009, did not detect any randomized controlled trial that compared the timing of elective cesarean delivery at 38 or 39 weeks and which investigated both perinatal and maternal outcomes.

In this report we address some of the maternal and perinatal consequences resulting from scheduling elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks rather than 38 weeks. We claim that scheduling elective cesarean delivery at 38 weeks is a viable alternative with potential benefits particularly for older women and women with numerous prior cesarean deliveries.

Women assigned to an elective cesarean delivery may go into labor prior to the scheduled date of surgery. Laboring women might present during the early stages of labor, with or without membrane ruptures, or alternatively they may present during advanced stages of labor. Maternal and neonatal outcomes may be adversely affected when cesarean delivery is preceded by labor, even if labor is not advanced.

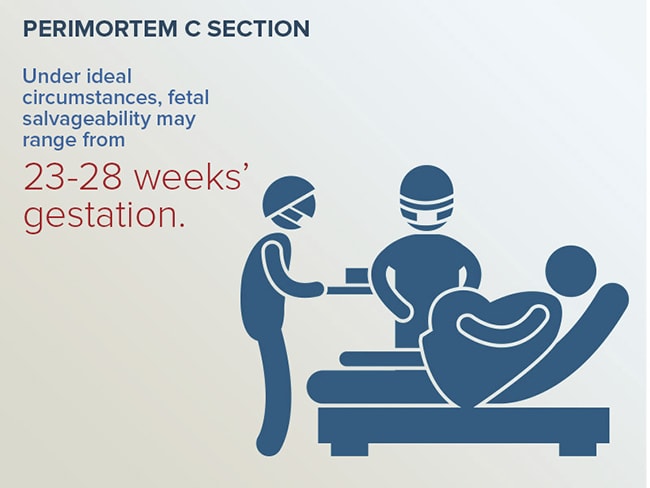

Fetal and neonatal consequences

The implication of scheduling delivery to 39 weeks is that a proportion of elective cesarean deliveries will convert to non-elective ones, which may increase the risk of traumatic injury to the fetus/newborn [3]. The reported incidence of iatrogenic fetal trauma during cesarean delivery is 0.1% to 1.9% of births [4]. Several risk factors for fetal injury at the time of the cesarean delivery have been identified through various case reports. These include lack of surgical experience, labor with thinning of the lower uterine segment exposing the fetus to injury with the scalpel, and a lack of amniotic fluid secondary to rupture of the membranes making the underlying fetal parts more accessible [5,6]. Fetal lacerations, finger injuries and amputations, penetrating brain injuries, skull fractures and long bone fractures have all been reported from the use of the scalpel or scissors at the time of cesarean delivery [3]. Although traumatic delivery is still associated with cesarean delivery, it is almost unheard of with elective cesarean delivery of the vertex fetus at term [3].

Fetal lacerations, finger injuries and amputations, penetrating brain injuries, skull fractures and long bone fractures have all been reported from the use of the scalpel or scissors at the time of cesarean delivery [3]. Although traumatic delivery is still associated with cesarean delivery, it is almost unheard of with elective cesarean delivery of the vertex fetus at term [3].

In the term breech trial, 6% of women who were assigned to a planned cesarean delivery, delivered vaginally because cesarean delivery was not possible due to imminent vaginal delivery [7]. Delaying an elective cesarean delivery scheduled for breech presentation may expose some of the fetuses to preventable morbidity and mortality associated with vaginal breech delivery in cases where vaginal delivery is imminent at admission.

An accumulative increased risk of intrauterine fetal death has been reported with increasing gestational age. The timing of fetal death for stillborn infants born between 23 and 40 weeks is evenly distributed with nearly 5% of all stillbirths occurring per week of gestation [8]. This is important when considering all stillborn infants at 38 weeks and beyond, where significant complications of prematurity would be very rare if only these fetuses had simply been delivered earlier. Furthermore, it has been reported that a fairly stable rate of fetal death of 0.6 per 1000 live births occurs from 33 weeks to 39 weeks of gestation. However, at 39 weeks, the rate increases significantly to 1.9 per 1000 live births [9]. De la Vega and coworkers in a mixed risk population with unrestricted access to testing for fetal wellbeing and sonographic evaluations concluded that, despite intensive surveillance, they were still unable to reduce the rate of fetal death. The investigators suggested that this is probably due to occurrence of acute placental and cord accidents that cannot be detected through antenatal fetal surveillance and are simply unavoidable [10]. The sudden death of a fetus in utero has medical, social and economic implications. It is particularly tragic when it occurs shortly before the expected date of delivery.

This is important when considering all stillborn infants at 38 weeks and beyond, where significant complications of prematurity would be very rare if only these fetuses had simply been delivered earlier. Furthermore, it has been reported that a fairly stable rate of fetal death of 0.6 per 1000 live births occurs from 33 weeks to 39 weeks of gestation. However, at 39 weeks, the rate increases significantly to 1.9 per 1000 live births [9]. De la Vega and coworkers in a mixed risk population with unrestricted access to testing for fetal wellbeing and sonographic evaluations concluded that, despite intensive surveillance, they were still unable to reduce the rate of fetal death. The investigators suggested that this is probably due to occurrence of acute placental and cord accidents that cannot be detected through antenatal fetal surveillance and are simply unavoidable [10]. The sudden death of a fetus in utero has medical, social and economic implications. It is particularly tragic when it occurs shortly before the expected date of delivery.

Maternal consequences

Hansen et al reported in a cohort study that a significant reduction in neonatal respiratory morbidity may occur if elective caesarean delivery is postponed to 39 weeks. Carrying out elective cesarean deliveries at a later gestational age resulted in higher rates of laboring cesarean deliveries since some women went into spontaneous labor. Twenty-five percent of women entered labor before the 39th week in their cohort. They also stated that compared with elective cesarean deliveries, laboring cesarean deliveries may carry an increased risk of complications such as uterine rupture, infections, or even maternal mortality [11].

Severe maternal morbidities including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid embolism, puerperal infection, severe hemorrhage, uterine rupture or inversion and intestinal obstruction have been reported to be significantly more frequent in non-elective than in elective cesarean deliveries. Operative interventions after delivery were also significantly more frequent after a non-elective cesarean delivery [12]. Operator experience and the emergency nature of the cesarean delivery were found to be risk factors for bladder injury during cesarean delivery [13].

Operator experience and the emergency nature of the cesarean delivery were found to be risk factors for bladder injury during cesarean delivery [13].

The overall risk of uterine rupture among women who go into spontaneous labor is higher compared to women who had an elective cesarean delivery. The risk of rupture is greater among parous women with multiple prior cesarean deliveries, a situation commonly encountered in some regions [14]. Other than maternal morbidity, a ruptured uterus carries a greater risk for perinatal morbidity and mortality [14].

Although uterine rupture occurs primarily among women during a trial of labor, women assigned to an elective cesarean delivery will occasionally present in the advanced stages of labor before their scheduled date of operation.

Failed intubation and pulmonary aspiration are the leading causes of anesthesia related maternal morbidity and mortality. Fasting for a period of six to eight hours is recommended before an elective cesarean delivery [15]. Women scheduled for an elective cesarean delivery and who go into spontaneous labor may present while not in the fasting state. Performing an immediate operation because the woman is in labor may increase anesthesia related morbidity and mortality. Alternatively, delaying the procedure six to eight hours may increase the likelihood of progression into advanced labor which may further complicate the operation. Furthermore, in women whose indication for a cesarean delivery is human immunodeficiency virus infection or genital herpes, the risk of neonatal infection may increase if abdominal delivery is delayed.

Women scheduled for an elective cesarean delivery and who go into spontaneous labor may present while not in the fasting state. Performing an immediate operation because the woman is in labor may increase anesthesia related morbidity and mortality. Alternatively, delaying the procedure six to eight hours may increase the likelihood of progression into advanced labor which may further complicate the operation. Furthermore, in women whose indication for a cesarean delivery is human immunodeficiency virus infection or genital herpes, the risk of neonatal infection may increase if abdominal delivery is delayed.

Women with severe urinary incontinence have a marked deterioration in their quality of life, most substantially curtail activities, many become homebound, and for some, urinary incontinence is the defining event that prompts nursing home admission. In the United States each year, an estimated 135,000 women undergo surgery for urinary incontinence [16]. An estimate of direct costs for urinary incontinence in the United States has been reported to be $16 billion per year [17]. Given the substantial public health burden of pelvic floor disorders, much research has been focused on identifying risk factors, especially modifiable risk factors, for the development of pelvic floor disorders. Retrospective and cross-sectional studies implicate childbirth as a major risk factor for urinary incontinence in younger women [18]. Whether, and to what degree, cesarean delivery may protect child-bearing women from developing urinary incontinence is an unresolved issue. Several prospective studies evaluated the risk of postpartum urinary incontinence by delivery type, grouping all cesarean deliveries together and reported inconsistent results. In one study, however, elective cesarean deliveries were separated form non-elective ones. Chin et al assessed the impact of delivery on the pelvic floor and to what degree cesarean deliveries could prevent pelvic floor injury. Five hundred thirty nine women were divided into three groups according to the delivery method adopted: elective cesarean delivery, non-elective cesarean delivery, and vaginal delivery.

Given the substantial public health burden of pelvic floor disorders, much research has been focused on identifying risk factors, especially modifiable risk factors, for the development of pelvic floor disorders. Retrospective and cross-sectional studies implicate childbirth as a major risk factor for urinary incontinence in younger women [18]. Whether, and to what degree, cesarean delivery may protect child-bearing women from developing urinary incontinence is an unresolved issue. Several prospective studies evaluated the risk of postpartum urinary incontinence by delivery type, grouping all cesarean deliveries together and reported inconsistent results. In one study, however, elective cesarean deliveries were separated form non-elective ones. Chin et al assessed the impact of delivery on the pelvic floor and to what degree cesarean deliveries could prevent pelvic floor injury. Five hundred thirty nine women were divided into three groups according to the delivery method adopted: elective cesarean delivery, non-elective cesarean delivery, and vaginal delivery. Only elective cesarean delivery was protective. They concluded that the key to the best protection against postpartum urinary incontinence seems to lie in the timing of the cesarean delivery; that is, the cesarean delivery has to be performed before labor or uterine contractions have commenced [19].

Only elective cesarean delivery was protective. They concluded that the key to the best protection against postpartum urinary incontinence seems to lie in the timing of the cesarean delivery; that is, the cesarean delivery has to be performed before labor or uterine contractions have commenced [19].

Delaying delivery until 39 weeks may increase the risk for pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and eclampsia that are known to increase in incidence from 37 to 43 weeks when calculated according to ongoing pregnancies [20].

Data suggests an increased risk of maternal mortality with non-elective cesarean deliveries as compared with elective ones. The Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths, 1997 to 1999, reported a significantly higher maternal mortality rate with emergency and urgent cesarean deliveries [21]. Another publication reporting on deliveries in Israel between 1984 and 1992 compared maternal mortality among vaginal deliveries, emergency and elective cesarean deliveries. The authors reported maternal mortality rates of 2.8, 3.6, and 30 per 100,000 deliveries for elective cesarean delivery, vaginal delivery, and emergency cesarean delivery, respectively [22].

The authors reported maternal mortality rates of 2.8, 3.6, and 30 per 100,000 deliveries for elective cesarean delivery, vaginal delivery, and emergency cesarean delivery, respectively [22].

Advance maternal age

More women are postponing pregnancy into the fourth and fifth decades of life for a variety of reasons. Advanced maternal age, traditionally defined as over 35 years, has been associated with increased obstetric morbidity and interventions.

Older women are more likely to have elective cesarean deliveries [23]. The risk for severe complications in non-elective cesarean deliveries is even higher among older women than in younger ones [12]. Furthermore, perinatal complications are reported to be higher among this population [24]. Intrauterine fetal death and perinatal mortality are significantly higher in older women even after excluding deaths due to congenital malformations and adjusting for existing illnesses or pregnancy complications [25]. The highest rate of stillbirth was reported to occur among older women after 38 weeks of gestation [26].

Health Care Provider Type and Professional Resources

The availability of resources, such as operating rooms and staff, may influence a health care provider's decision regarding when to schedule the date of the elective cesarean delivery. Non-elective cesarean deliveries, which by definition are poorly timed, may result in a patient that presents in the non fasting state, at a time that the hospital is staffed with less experienced surgeons and anesthetists whose skills are further compromised due to demanding working hours. All these factors present additional challenges to the patients' safety. One of the advantages of scheduled operations is the greater ease of balancing staffing levels with clinical volume. Inadequate levels of staffing, as well as fatigue among health care providers, may contribute to increased patient morbidity [27,28].

Multiple chance events may influence outcome. For example, an elective cesarean delivery at 38 weeks may result in the delivery of an iatrogenically premature infant at risk for respiratory morbidity. On the other hand, delaying delivery to 39 weeks may result in an unexplained stillbirth, or spontaneous onset of labor with intrapartum complications that may compromise maternal and neonatal well-being. Decision analysis is a quantitative methodology for evaluating competing strategies under conditions of uncertainty.

On the other hand, delaying delivery to 39 weeks may result in an unexplained stillbirth, or spontaneous onset of labor with intrapartum complications that may compromise maternal and neonatal well-being. Decision analysis is a quantitative methodology for evaluating competing strategies under conditions of uncertainty.

According to our data, 14% of all women booked for an elective cesarean delivery at exactly 39 weeks and 0 days, would be expected to go into spontaneous labor between 38 to 39 weeks (unpublished data). For an average hospital with 4500 births a year, such as ours, and a 10% elective cesarean delivery rate, scheduling delivery at 38 weeks rather than 39 weeks will result in an additional 10 neonates with respiratory morbidity a year, assuming an additional 2% neonatal morbidity for those delivered at 38 weeks [29]. On the other hand, 63 non-elective cesarean deliveries will be prevented. In fact, since it is not feasible to book all women to exactly 39 weeks and 0 days, particularly in public medical centers, the number of non-elective operations that would be prevented may actually be higher. Other than decreasing the risk of non-elective cesareans, scheduling elective cesarean deliveries to 38 weeks may prevent cases of fetal death especially among older women.

Other than decreasing the risk of non-elective cesareans, scheduling elective cesarean deliveries to 38 weeks may prevent cases of fetal death especially among older women.

Until prospective randomized trials are conducted, we are unlikely to be able to precisely answer all risk:benefit questions as to the best timing of scheduled elective cesarean delivery. We believe that if dating is confirmed with an ultrasound study prior to 20 weeks of gestation, scheduling cesarean delivery to 38+0-6 weeks may be another reasonable and alternative option to 39 weeks. This is particularly true among a selected group of women, namely older women and women where a complicated cesarean delivery is anticipated. It is reasonable to inform women of the risks entailed with each of the above options. The clinician's role should be to provide the best evidence-based counseling possible to the woman, and to respect her autonomy and decision-making.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

RS and ES contributed to the formation, drafting and editing of this article. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

RS is a senior obstetrician, head of delivery ward, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology HaEmek Medical Center, Afula, Israel; ES is a professor and associate Dean, Rappaport Faculty of Medicine Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology HaEmek Medical Center, Afula, Israel.

- Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker S, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, Carpenter M, Peaceman AM, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai B, Langer O, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM, Gabbe SG. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2581–2589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040405. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Paranjothy S.

The national sentinel caesarean section audit report. London: RCOG Press; 2001. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit. [Google Scholar]

The national sentinel caesarean section audit report. London: RCOG Press; 2001. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit. [Google Scholar] - Hankins GD, Clark SM, Munn MB. Cesarean section on request at 39 weeks: impact on shoulder dystocia, fetal trauma, neonatal encephalopathy, and intrauterine fetal demise. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30:276–287. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.07.009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aburezq H, Chakrabarty KH, Zuker RM. Iatrogenic fetal injury. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1172–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puza S, Roth N, Macones GA, Mennuti MT, Morgan MA. Does cesarean section decrease the incidence of major birth trauma? J Perinatol. 1998;18:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas DM, Ayres AW. Laceration at cesarean section. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:196–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial.

Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356:1375–1383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02840-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356:1375–1383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02840-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Dubard MB, Davis RO. Risk factors for fetal death in white, black, and Hispanic women. Collaborative Group on Preterm Birth Prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:490–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkin PL, Wood L, Redman CWG. Risk of unexplained stillbirth at different gestational ages. Lancet. 1987;1:1192–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Vega A, Verdiales M. Failure of intensive fetal monitoring and ultrasound in reducing the stillbirth rate. P R Health Sci J. 2002;21:123–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AK, Wisborg K, Uldbjerg N, Henriksen TB. Risk of respiratory morbidity in term infants delivered by elective cesarean section: cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:85–87. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39405.539282.BE. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa N, Ekblad U, Gissler M.

Severe maternal morbidity and the mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:662–668. doi: 10.1080/00016340802108763. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Severe maternal morbidity and the mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:662–668. doi: 10.1080/00016340802108763. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Rahman MS, Gasem T, Al Suleiman SA, Al Jama FE, Burshaid S, Rahman J. Bladder injuries during cesarean section in a University Hospital: a 25-year review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:349–352. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0733-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DA, Diaz FG, Paul RH. Vaginal birth after cesarean: a 10-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstetric analgesia and anesthesia. ACOG practice bulletin Number 36, July 2002. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78:321–335. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00268-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Waetjen LE, Subak LL, Shen H, Lin F, Wang TH, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS. Stress urinary incontinence surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:671–676.

doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)03124-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)03124-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Wilson L, Brown JS, Shin GP, Luc K, Subak LL. Annual direct cost of urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:398–406. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01464-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hunskaar S, Burgio K, Clark A, Lapitan MC, Nelson R, Sillen U, Thom D. In: Incontinence. 3rd International Consultation on Incontinence. 3. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editor. Vol. 1. Plymouth: Health Publication Ltd; 2005. Epidemiology of urinary incontinence (UI) and faecal incontinence (FI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) pp. 255–313. [Google Scholar]

- Chin HY, Chen MC, Liu YH, Wang KH. Postpartum urinary incontinence: a comparison of vaginal delivery, elective, and emergent cesarean section. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:631–635. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0085-y. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey AB, Stotland NE, Escobar GJ. What is the best measure of maternal complications of term pregnancy: ongoing pregnancies or pregnancies delivered? Am J Obstet Gynecol.

2003;189:1047–1052. doi: 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00897-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2003;189:1047–1052. doi: 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00897-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Department of Health, Scottish Executive Health Department, and Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, Northern Ireland. Why Mothers Die. Fifth Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom, 1997-1999. London: RCOG Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yoles I, Maschiach S. Increased maternal mortality in cesarean delivery as compared to vaginal delivery? Time for re-evaluation [abstract] Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:s78. [Google Scholar]

- Ecker JL, Chen KT, Cohen AP, Riley LE, Lieberman ES. Increased risk of cesarean delivery with advancing maternal age: indications and associated factors in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:883–887. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117364. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Usta IM, Nassar AH. Advanced maternal age. Part I: obstetric complications. Am J Perinatol. 2008;5:521–534. doi: 10.

1055/s-0028-1085620. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1055/s-0028-1085620. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Jacobsson B, Ladfors L, Milsom I. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC. Life-table analysis of the risk of perinatal death at term and post term in singleton pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:489–496. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.109735. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J. UK Neonatal Staffing Study Group. Patient volume, staffing, and workload in relation to risk-adjusted outcomes in a random stratified sample of UK neonatal intensive care units: a prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2002;359:99–107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07366-X. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Minkoff H, Chervenak FA. Elective primary cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:946–950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb022734. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tita AT, Landon MB, Spong CY, Lai Y, Leveno KJ, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Meis PJ, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, Carpenter M, Peaceman AM, O'Sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Langer O, Thorp JM, Ramin SM, Mercer BM.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Timing of elective repeat cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:111–120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Timing of elective repeat cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:111–120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology : RB&E are provided here courtesy of BioMed Central

Dividing the common property of the spouses: in time for 3 years

Marina Frolova

Attorney at the Moscow Bar Association, Law Office No. 14 of the Moscow City Bar Association

25 August 2021

Tips

In the event of a divorce, you can apply to the court with a claim for the division of jointly acquired property within 3 years. But from what moment is this period counted?

"Is it possible to divide the jointly acquired property of the spouses five years after the divorce?" - a reader addressed the editorial office of AG with such a question.

Before answering this question, let's figure out what is the jointly acquired property of the spouses and how it is divided in the event of a divorce.

Joint property of the spouses - in half

Any movable and immovable property acquired in an official marriage is recognized as jointly acquired property of the spouses. This is what Art. 34 of the Family Code of the Russian Federation.

By default, when dividing jointly acquired property, the principle of equality of shares of spouses applies. That is, each of them owns half of what was acquired in a legal marriage, from pots to a yacht. At the same time, there are things that cannot be divided upon dissolution of a marriage: personal belongings of each of the spouses (except for luxury items and jewelry), gifts and property received by inheritance. Children's things remain with the spouse with whom the child will live after the dissolution of the marriage. Thus, in the event of a division of property in court, a gaming computer, an expensive watch, and a mink coat will also be divided. If during the period of marriage a prenuptial agreement was concluded, which establishes which of the spouses will receive this or that property during a divorce, then the court will be guided by this agreement.

If during the period of marriage a prenuptial agreement was concluded, which establishes which of the spouses will receive this or that property during a divorce, then the court will be guided by this agreement.

(On the controversial issues in the division of the real estate of the spouses, acquired with the money that one of them received from the sale of his inheritance, read the article “How are the “inheritance” meters divided during a divorce?”. About why the apartment donated by the husband to his wife will not be to share in half after a divorce, is described in the material "Relatives will help ... to lose their home. How debts on loans will be divided - you can read in the article" Real estate for a wife, debts for a husband?).

For the division of property - 3 years

You have determined what property is subject to division after the dissolution of the marriage. What's next? And then you need to understand what time period is set for filing a claim with the court. According to the general rule, the limitation period for filing a claim for the division of the common property of the spouses is 3 years (Article 38 of the Family Code of the Russian Federation, Article 169 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation).

According to the general rule, the limitation period for filing a claim for the division of the common property of the spouses is 3 years (Article 38 of the Family Code of the Russian Federation, Article 169 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation).

Here the question reasonably arises: from what moment to calculate the three-year limitation period? The answer to this question was given by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. According to paragraph 19Decree of the Plenum of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation of November 5, 1998 No. 15, the specified period must be calculated from the day when the person knew or should have known about the violation of his right.

I'll give you an example. You are officially divorced. After the divorce, it seemed to you that there was nothing to share with your ex-spouse: you didn’t buy expensive property in marriage, and you didn’t share kitchen utensils. And then, 5 years later, you find out that the ex-husband has a bank account for an impressive amount. The account was opened during the marriage for a long period of time, the amount of funds on it did not change. From the moment when you became aware of the existence of an account, the countdown of the three-year limitation period begins.

The account was opened during the marriage for a long period of time, the amount of funds on it did not change. From the moment when you became aware of the existence of an account, the countdown of the three-year limitation period begins.

Or another example. You had to go on a long business trip abroad. At this time, your spouse filed for divorce and sold the jointly acquired car. You return to the country and find out that the car has been sold. It is from the moment when you became aware of this that you can file a claim with the court to recover compensation.

Important: in court you will have to prove that you learned about the violation of your rights no more than 3 years before filing a claim.

Site and sections setup | Atlassian

Sign up for a free trial of Confluence Cloud before you start this tutorial. With this guide, you will set up your first project. Do not close the tab while you subscribe. We will wait for you.

This tutorial is for Confluence Cloud. If you're interested in the self-managed version of the product, go to >>

If you're interested in the self-managed version of the product, go to >>

If you're using the Confluence Data Center or Confluence Server variant, learn how to create and edit pages in Confluence in this tutorial.

Step 4: Organize the content

Now that the first section has been created, we can start structuring it. Our goal is to make the section easier to navigate so that team members and other stakeholders can quickly find the content they need.

For more information about navigation, see Tutorial 4: Navigating in Confluence.

Use parent pages to group similar content

In Confluence, you can nest pages within pages to create a content hierarchy within each section. This hierarchy, represented as a page tree, is displayed in the section's sidebar, to the left of the active page.

To use the page tree effectively, create a separate page for each task or project the team is involved in, and place related child pages on that page. If, for example, the team hosts bi-weekly retrospectives, you might create a top-level page called "Retrospectives" and include one page for each retrospective held.

If, for example, the team hosts bi-weekly retrospectives, you might create a top-level page called "Retrospectives" and include one page for each retrospective held.

The following example shows how one of the Atlassian teams used this strategy to organize their section.

Create shortcuts for important pages

Confluence allows you to create unique section labels for all sections of your site : links pinned to the sidebar of a section, above the page tree. Use them to highlight important content so it's easy to find.

To create the first section shortcut, navigate to the desired section and select + Add shortcut in the sidebar. For more information about section shortcuts, editing and deleting them, see section Setting up a section.

Use tags for pages and attachments

Tags make it easy to identify related pages and attachments. This makes it easier for team members and other stakeholders to find the information they need.

- Open the page in Confluence.

- Select the tag icon () in the lower right corner.*

- Enter the name of the desired tag. If a tag with the same name already exists, it will appear in the auto-substitution menu.

- To add a label, select Add .

- To exit the dialog box, click Close .

* If you are not viewing, but editing the page, go to the menu ••• (Other actions) in the upper right corner and select the command Add labels (Add labels) .

Give labels clear, meaningful names. For example, a label for meeting minutes might be named meeting minutes or meeting . If you add this label to all meeting minutes pages, you can simply select this label to view all meeting minutes (from one section or from the entire Confluence site). You can also display all pages tagged with the same tag on a single page, or search for content by tag to make it easier to find related pages and attachments. For more information about tags, see Use tags to organize content.

For more information about tags, see Use tags to organize content.

Pro tip

If you add a tag to a page template, the tag will automatically be added to every page that is based on that template.

Keep content organized

Take time to review content in your section, delete or archive outdated content, and move pages around to maintain structure. If you are a site administrator, establish section maintenance rituals for your team members and encourage section administrators to set aside time to review and update sections with the right users involved.

- Get people to help you with the tabs in the section.

- Audit content and view analytics.

- Identify outdated and irrelevant pages and make a plan of action.

- Review your information architecture and align it to current needs.

See this blog post for details.

Step 5: Manage Users and Permissions

A Confluence administrator or site administrator with a paid Confluence subscription can manage users, groups, and permissions manually, or enable public registration and allow users to create their own accounts. For more information about access rights for the free plan, see our documentation.

For more information about access rights for the free plan, see our documentation.

Global Rights Management

Pro Tip

You must have Confluence Administrator rights to manage global rights.

Global permissions are valid for the entire site and allow you to control:

- assign users who can create sections or personal sections;

- assign users who will have the right to access user profiles.

- allow or deny access to the site to unlicensed users;

- access to the application site.

Allowed number of users

To change the global access rights for licensed users, follow these steps.

- Click the gear icon on the top navigation bar to go to site settings.

- In the sidenav settings go to Global Permissions (Global Permissions) (Menu security ).

- Make sure you are on the User groups or Guest access tab if you want to manage guest access, and then click the edit button .

- Select or clear the check box to grant or revoke the right.

- When finished, press the Save button (Save).

Changes to global permissions will only take effect after you press button save .

You can also search and filter user groups in edit mode.

Unlicensed users

Confluence unlicensed users can be managed in two ways.

Jira Service Management Unlicensed Access

- The JSM Access tab allows licensed Jira Service Management (JSM) agents to view the content of your Confluence site, even if those agents do not have a Confluence license. Read more

Anonymous access

- On the Anonymous access tab (Anonymous access), you can allow partition administrators to make their partitions available to all unlicensed users (so-called "anonymous users" or "all Internet users"). Read more

Managing section access rights

Professional advice

To edit access rights, you must be a section administrator. If you are a Confluence administrator, you can restore administrative access rights for any section of the site. For more information, see What are partition permissions.

If you are a Confluence administrator, you can restore administrative access rights for any section of the site. For more information, see What are partition permissions.

Access rights to the section allow:

- assign users who can view the content of the section;

- designate users who can comment on this content;

- designate users who can create, edit, and upload content.

The Confluence tool is public by default. This means that if you don't restrict access to sections, all users of the Confluence site will have access to the content of any section. Section administrators can set permissions when creating a new section or adjust them later. Anyone who has the right to edit a page can also restrict access to it.

To obtain access rights to a partition, follow these steps.

- Go to section.

- Select Space settings in the Confluence sidebar.

- In the section settings, select the tab Permissions (Rights).

* The Permissions tab is displayed only for administrators of this section.

You can manage access rights to sections of individual users or entire groups. If your site is public, you can also grant anonymous access to certain sections. For more information, see Setting up public access.

For more information about access rights to sections, see the article Assigning access rights to sections.

How to set the permissions for a partition?

Some Confluence clients use the same permissions scheme for all sections of the site, while others set permissions for sections differently, depending on their purpose or usage scenarios.

| Share customer support information with customers | Target audience

| Permissions

|

| Share policies, tutorials, and troubleshooting tips with your organization | Target Audience

| Permissions

|

| Collaborate on a project or initiative with others | Target Audience

| Access rights

|

| Share confidential information (employee, salary, or legal matters) | The target audience

| Access rights

|

Inviting team members to your site

Once your site and permissions are set up, you can invite team members to work with Confluence Cloud (and other Atlassian products on the site).

- Select the settings icon (gear) in the upper right corner (next to the avatar).

- Select User management from the sidebar.

- Select Invite users in the top right corner.

- Enter the email addresses of all team members you want to invite. You can enter up to 10 email addresses at a time.

- Select the role of the invited team members. It determines the level of access rights to the site as a whole.

- Select the products you want to share with team members.*

- Select the groups you want them to belong to.

- Customize your invitation and select Invite user .

* Only for team members with role Basic .

As a site administrator, you can change a user's role, permissions, and group at any time. You can also remove a user by revoking site access rights, deactivating or even deleting their account (if, for example, an employee leaves the company).