Baby outside the womb

We may one day grow babies outside the womb, but there are many things to consider first

This is one of our occasional Essays on Health. It’s a long read. Enjoy!

The idea of growing babies outside the body has inspired novels and movies for decades.

Now, research groups around the world are exploring the possibility of artificial gestation. For instance, one group successfully grew a lamb in an artificial womb for four weeks. Australian researchers have also experimented with artificial gestation for lambs and sharks.

And in recent weeks, researchers in The Netherlands have received €2.9m (A$4.66m) to develop a prototype for gestating premature babies.

So it’s important to consider some of the ethical issues this technology might bring.

Read more: From frozen ovaries to lab-grown babies: the future of childbirth

What is an artificial womb?

Growing a baby outside the womb is known as ectogenesis (or exogenesis). And we’re already using a form of it. When premature infants are transferred to humidicribs to continue their development in a neonatal unit, that’s partial ectogenesis.

But an artificial womb could extend the period a fetus could be gestated outside the body. Eventually we might be able to do away with human wombs altogether.

This may sound far-fetched, but many scientists working in reproductive biotechnology believe that with the necessary scientific and legal support, full ectogenesis is a real possibility for the future.

What would an artificial womb contain?

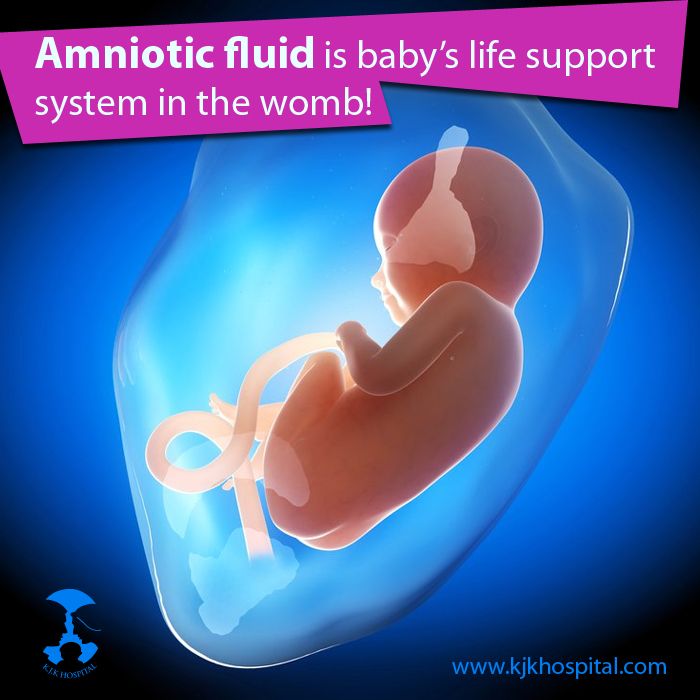

An artificial womb would need an outer shell or chamber. That’s somewhere to implant the embryo and protect it as it grows. So far, animal experiments have used acrylic tanks, plastics bags and uterine tissues removed from an organism and artificially kept alive.

An artificial womb would also need a synthetic replacement for amniotic fluid, a shock absorber in the womb during natural pregnancy.

Finally, there would have to be a way to exchange oxygen and nutrients (so oxygen and nutrients in and carbon dioxide and waste products out). In other words, researchers would have to build an artificial placenta.

Animal experiments have used complex catheter and pump systems. But there are plans to use a mini version of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, a technique that allows blood to be oxygenated outside the body.

Read more: The business of IVF: how human eggs went from simple cells to a valuable commodity

Once these are in place, artificial gestation could one day become as common as IVF is today, a technique considered revolutionary a few decades ago.

And just as in the case of IVF, there are many who are concerned about what this new realm of reproductive medicine might mean for the future of creating a family.

So what are some of the ethical considerations?

Artificial wombs could help premature babies

The main discussion about artificial wombs has focused on their potential benefit in increasing the survival rate of extremely premature babies.

Currently, those born earlier than 22 weeks gestation have little-to-no hope of survival. And those born at 23 weeks are likely to suffer a range of disabilities.

Using a sealed “biobag”, which mimics the maternal womb might help extremely premature babies survive and improve their quality of life.

A biobag provides oxygen, a type of substitute amniotic fluid, umbilical cord access and all necessary water and nutrients (and medicine, if required). This could potentially allow the gestational period to be prolonged outside the womb until the baby has developed sufficiently to live independently and with good health prospects.

Premature lambs survived for four weeks in a ‘biobag’ at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Tech Insider/YouTube).

An artificial womb might provide an optimum environment for the fetus to grow, providing it with the appropriate balance of hormones and nutrients. It would also avoid exposing the growing fetus to external harms such as infectious diseases.

The technology might also make it easier to perform surgery on the fetus if needed.

And it could see the end of long-term hospital stays for premature infants, saving health care dollars in the process. This is particularly noteworthy considering some of the largest private insurance payments are currently for neonatal intensive care unit expenses.

Artificial wombs could help with infertility and fertility

This emerging reproductive technology may allow women who are infertile, either due to physiological or social reasons, with the chance of having a child. It may also offer opportunities for transgender women and other women born without a uterus, or those who have lost their uterus due to cancer, injury or medical conditions, to have children.

Similarly, it could allow single men and gay male couples to become parents without needing a surrogate.

Artificial wombs could allow gay men to become parents without needing a surrogate. from www.shutterstock.comWill this lead to a broader discussion about gender roles and equality in reproduction? Will it remove potential risks and expectations of pregnancy and childbirth currently only affecting women? Will this eliminate commercial surrogacy?

Equally, artificial wombs could help fertile women who for health or personal reasons choose not to be pregnant. It would allow those whose career choices, medication or lifestyle might otherwise expose a developing fetus to malformation or abnormality.

Artificial wombs may harm women, reinforce inequality and lead to discrimination

The prospect of artificial wombs might offer hope for many, but it also highlights a number of potential hazards.

For some women, using an artificial womb for gestation to continue might seem like a welcome alternative to terminating a pregnancy. But there are fears that other women thinking about an abortion might be compelled to use an artificial womb to continue gestation.

But there are fears that other women thinking about an abortion might be compelled to use an artificial womb to continue gestation.

Whether artificial wombs should be allowed to influence a woman’s right to choose is already under debate.

Read more: What's Mother's Day if you've been born in a machine and raised by robots?

Artificial wombs might also further increase the gap between rich and poor. Wealthy prospective parents may opt to pay for artificial wombs, while poorer people will rely on women’s bodies to gestate their babies. Existing disparities in nutrition and exposure to pathogens between pregnancies across socio-economic divides could also be exacerbated.

Artificial wombs might further increase the gap between rich and poor. from www.shutterstock.comThis raises issues of distribution of access. Will artificial wombs receive government funding? If it does, who should decide who gets subsidised access? Will there be a threshold to meet?

Other issues concern potential discrimination individuals born via an artificial womb may face. How do we prevent discrimination or invasive publicity and ensure individuals’ origin stories are not subject to negative public curiosity or ridicule?

How do we prevent discrimination or invasive publicity and ensure individuals’ origin stories are not subject to negative public curiosity or ridicule?

Others might consider artificial wombs to be deeply repugnant and fundamentally against the natural reproductive order.

Preparing for future wombs

Currently, there is no prototype of an artificial womb for humans. And the technology is very much in its infancy. Yet we do need to consider ethical and legal issues before rushing headlong into this reproductive technology.

Not only do we need to ensure the technology is safe and works, we need to consider whether it’s the right path to take for different circumstances.

It might be easier to defend using artificial wombs in emergency situations, such as saving the lives of extremely premature neonates. However, using them in other circumstances might need broader social and policy considerations.

Read more: We must develop 'techno-wisdom' to prevent technology from consuming us

Without first establishing clear regulatory and ethico-legal frameworks, the development and release of artificial wombs could be problematic. We need to clearly outline pregnancy termination rights, parenthood and guardianship issues, limitations to experimentation, and other issues before the technology is fully realised and available. We need to do this soon rather than allowing the law to lag behind the science.

We need to clearly outline pregnancy termination rights, parenthood and guardianship issues, limitations to experimentation, and other issues before the technology is fully realised and available. We need to do this soon rather than allowing the law to lag behind the science.

We recommend:

approved protocols for testing artificial wombs that gradually extend the gestation period

funding that prevents discrimination on socio-economic grounds. This might be in the form of government funding to ensue a wide range of groups have access to the technology

clear legal guidelines for the status of ectogenetic embryos and fetuses, including what happens if prospective parents die, divorce or disagree on how to proceed

guidelines for access that calm public fears about misuse of emerging reproductive technologies.

It is easy to get carried away with visions of utopian or dystopian societies. As radical and futuristic as artificial wombs might sound, it is important to pause and reflect on the present.

While this technology may solve some existing problems concerning inequality in reproduction, there are many other issues that demand our immediate attention.

Improving maternal health services, equal opportunity in the workplace, and reducing the impact of poor social determinants of health on fetal outcomes are all pressing concerns we must address now before we can consider what the future of reproductive biotechnology might hold.

Read more: Where we come from determines how we fare – the fetal origins of adult disease

‘Parents can look at their foetus in real time’: are artificial wombs the future? | Pregnancy

The lamb is sleeping. It lies on its side, eyes shut, ears folded back and twitching. It swallows, wriggles and shuffles its gangly legs. Its crooked half-smile makes it look content, as if dreaming about gambolling in a grassy field. But this lamb is too tiny to venture out. Its eyes cannot open. It is hairless; its skin gathers in pink rolls at its neck. It hasn’t been born yet, but here it is, at 111 days’ gestation, totally separate from its mother, alive and kicking in a research lab in Philadelphia. It is submerged in fluid, floating inside a transparent plastic bag, its umbilical cord connected to a nexus of bright blood-filled tubes. This is a foetus growing inside an artificial womb. In another four weeks, the bag will be unzipped and the lamb will be born.

It is hairless; its skin gathers in pink rolls at its neck. It hasn’t been born yet, but here it is, at 111 days’ gestation, totally separate from its mother, alive and kicking in a research lab in Philadelphia. It is submerged in fluid, floating inside a transparent plastic bag, its umbilical cord connected to a nexus of bright blood-filled tubes. This is a foetus growing inside an artificial womb. In another four weeks, the bag will be unzipped and the lamb will be born.

When I first see images of the Philadelphia lambs on my laptop, I think of the foetus fields in The Matrix, where motherless babies are farmed in pods on an industrial scale. But this is not a substitute for full gestation. The lambs didn’t grow in the bags from conception; they were taken from their mothers’ wombs by caesarean section, then submerged in the Biobag, at a gestational age equivalent to 23-24 weeks in humans. This isn’t a replacement for pregnancy yet, but it is certainly the beginning.

The team who made these artificial wombs say they are driven only by the desire to save the most vulnerable humans on Earth. Emily Partridge, Marcus Davey and Alan Flake are neonatologists, developmental physiologists and surgeons who work with extremely premature babies at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). After three years of tweaking, their latest prototype is designed to give babies born too soon a greater chance of survival than ever before.

Emily Partridge, Marcus Davey and Alan Flake are neonatologists, developmental physiologists and surgeons who work with extremely premature babies at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). After three years of tweaking, their latest prototype is designed to give babies born too soon a greater chance of survival than ever before.

The Biobag was born into public consciousness in April 2017, when the CHOP team published their research in the journal Nature Communications. They had found a way to gestate sheep foetuses outside maternal bodies; foetuses that would eventually become lambs no different from those that had grown in ewes’ wombs. (Sheep are the go-to animals in obstetric research because they have a long gestation period and the foetuses are around the same size as ours.)

Their invention consists of a replacement placenta: an oxygenator plugged into the lamb’s umbilical cord, which also removes carbon dioxide and delivers nutrients. Blood is pumped entirely by the beating of the foetus’s heart, just as it would be in the womb. The bag acts like an amniotic sac filled with warm, sterile, lab-made fluid that the lamb breathes and swallows, just as a human foetus would.

CHOP’s communications department released a very slick short film, Recreating The Womb, to coincide with the paper’s release. There is not a foetus in sight. Instead there are neat diagrams of lambs in Biobag systems, slightly awkward footage of Partridge, Flake and Davey pretending to do lambless lamb research in a pristine lab and heartbreaking clips of impossibly small super-premature babies. Then there are carefully edited interviews with the team. “In the future, we envision the system will be in the neonatal intensive care unit and will look pretty much like a traditional incubator,” Davey says. The Biobags would be kept in a darkened environment to mimic the human womb, but the babies would be visible as never before: “Parents can actually look at their foetus in real time,” Flake adds.

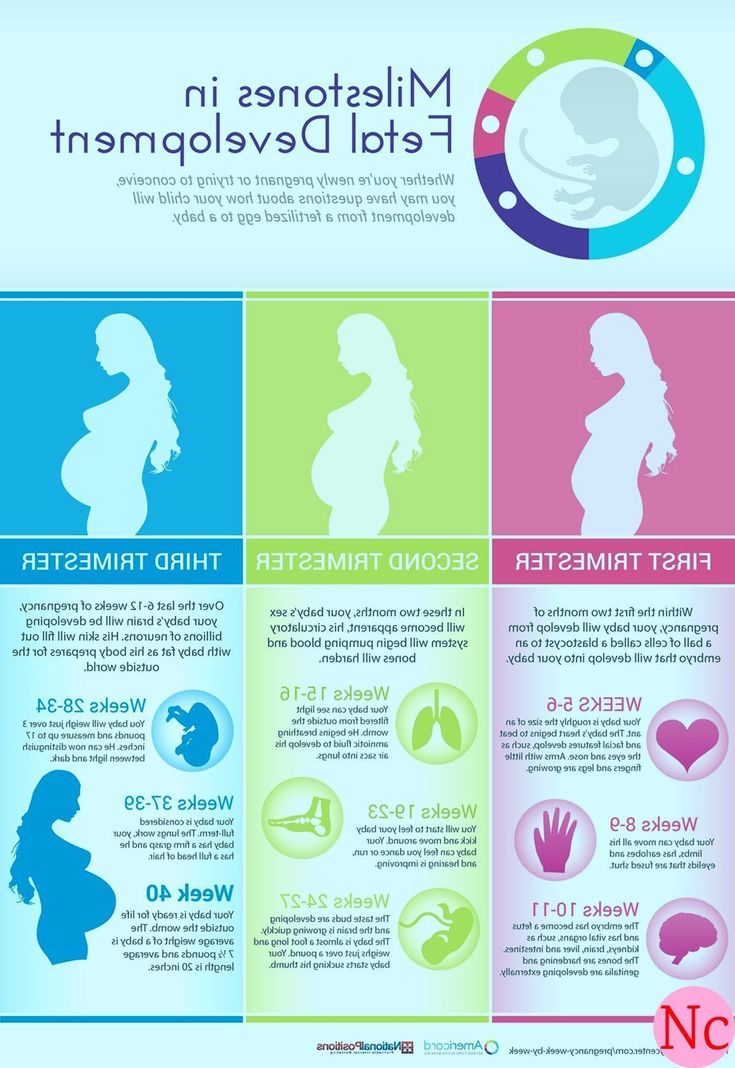

Normal human pregnancy is 40 weeks; any baby born before 37 weeks is considered premature. The 23-24-week period is the border of viability, after which modern medicine currently has a hope of keeping babies alive, and doctors will attempt to resuscitate a newborn. To the NHS, a baby born dead at 24 weeks is classed as a stillbirth, whereas a dead baby born at 23 weeks and six days is a miscarriage. It is a brutal boundary.

A lamb cannulated at 107 days’ gestation, on day four in a Biobag. Photograph: nature.com/Children’s Hospital of PhiladelphiaIn countries with good hospitals, there is a 24% chance of keeping a baby born at 23 weeks alive. But 87% of those who make it will experience major complications, such as lung disease, bowel problems, brain damage and blindness. While more extremely premature babies are surviving in wealthier countries, the number growing up with chronic conditions has also increased dramatically. Preterm birth is the greatest cause of death and disability among children under five in the developed world.

Incubators deal with some of the functions a premature newborn needs help with, but they don’t allow for the process of gestation to continue; the Biobag does, treating the baby as a foetus who has not yet been born. Women at risk of going into very early labour could have their babies transferred into an artificial womb. It sounds extreme, but if it could mean a healthy future instead of illness and disability, who could deny it to them?

The CHOP researchers want their device to be seen as ethically unremarkable. “Our goal is not to extend the limits of viability, but to offer the potential for improved outcomes for those infants already being routinely resuscitated,” their paper says. Extending the current limits of a foetus’s viability would create an ethical minefield. The legal abortion limit in the UK was brought down from 28 to 24 weeks in 1990 because advances in neonatal care meant foetuses born then were more likely to live. If artificial wombs help ever smaller babies survive, that could have profound implications for women. But women are not mentioned in CHOP’s work.

The application to patent the Biobag, filed in 2014, is revealing. There’s no coyness about extending the limits of human viability here: it explicitly says possible “subjects” include “pre-viable foetuses (eg 20–24 weeks)”.

I am not allowed to go to Philadelphia to see the team’s work. I so nearly was: Flake told me I was welcome, and we fixed a date. But then I was suddenly unwelcome. They want to be able to put human babies inside the Biobag within a couple of years, and the prospect of my visit had made the legal department twitchy. “There is a lot of caution to do anything that could jeopardise FDA approval,” a press officer told me.

“This is not a new field,” says Matt Kemp, wearily. He runs the perinatal lab at the Women & Infants Research Foundation (WIRF) in Western Australia, and his team’s artificial womb, Ex-Vivo Uterine Environment or EVE therapy, reported its first great successes in a paper published a few months after CHOP’s. The Biobag stole EVE’s thunder, and though Kemp makes little reference to it, he does sound somewhat narked.

“The Karolinska Institute in Sweden published a paper in 1958 showing the use of this sort of platform with pre-viable human foetuses,” he says. “Groups in Canada in the early 60s experimented with sheep using this system. As early as 1963, the Japanese did seminal work in the field... Anyone who tells you they have done this for the first time is being disingenuous.” He doesn’t name names.

In the incubator there is a lamb, its chest rising and falling, submerged in yellowish fluid in a transparent bag

There is no patent application for EVE (“It’s not patentable,” Kemp says, exasperated, “this has all been in the public domain since 1958”), so he is happy to answer questions – unless they are about the reason he decided to name his artificial womb after the first woman and the mother of mankind. He doesn’t want to get drawn into discussions about the symbolism of his work: “It was just a convenient way of describing it, I guess. ”

Kemp has been developing EVE since 2013, with researchers at Tohoku University hospital in Sendai, Japan. No official images have been released, but I found a YouTube video uploaded to the WIRF channel. It looked as if it wasn’t supposed to be online (and has since been removed): it was clearly filmed on a phone and had had only 56 views in a year. After CHOP’s carefully sanitised images, this 44-second clip made my jaw drop.

It begins with beeping monitors in a neonatal intensive care unit; a healthy heartbeat thumping in red on a black screen. The camera pans to an incubator beside it and instead of a baby there is a lamb, its chest rising and falling, lying in yellowish fluid in a transparent bag from which protrudes a mass of tubes, like veins filled with blood. This is what an artificial womb really looks like.

‘Incubators deal with some of the functions a premature newborn needs help with, but they don’t allow for the process of gestation to continue.’ Photograph: Liz McBurney/The GuardianThe big difference between the work of WIRF and CHOP is the age of the lambs. The youngest foetus put into the Biobag was 106 days; EVE’s was 95. Kemp is cautious about translating this into human terms, but it’s between 21 and 23 weeks. No one else has ever reported working with foetuses this young. And while CHOP grew their lambs for several weeks, often to term, and let some live, Kemp’s team kept them in the artificial womb for a week, then killed all of them to analyse their organs. He says they could easily have kept them alive for longer: “These are stable, healthy animals.”

Even in a week, the lambs change dramatically, putting on weight and flexing and swallowing. “I’ve never been pregnant,” Kemp says, “but my wife says a foetus does those movements. It kicks, has a wee wiggle and goes back to sleep.”

But clinical trials involving human babies are a long way off. “Anyone who tells you they are going to be doing this in two years either has a wealth of data that is not in the public domain or is being a bit sensationalist.”

Is he talking about anyone in particular?

I lost a baby at 20 weeks.If a fake womb might save a sick foetus, could it also save a healthy 20-week-old?

“I am not,” he says firmly. “All the experiments to date have been done on foetuses that come from healthy pregnancies. That’s simply not the case for a 21- or 22-week human foetus. These are not going to be healthy babies. Getting this into clinical use is going to be incredibly difficult. To create an argument an ethical committee will buy, you’ve got to have an odds-on chance of delivering an outcome far better than the technology currently in use,” he says. “What is the likely first demographic? A very sick 21-week foetus.”

This floors me. I lost a baby at 20 weeks – a son, who would have been my second child. There was nothing wrong with him. He was perfect. I got appendicitis when I was nearly 19 weeks pregnant. I spent a week in hospital while obstetricians and gynaecologists scanned and poked, trying to work out why I was ill. And then I went into labour. It happens: if you are pregnant, a serious infection can cause your cervix to open. In between contractions, the obstetrician told me if I had been 24 weeks pregnant, everything would have been different. Even though my son was a proper baby, who was wrapped up and given to me to hold, he died while I was giving birth to him. A miscarriage, not a stillbirth.

This happened three years ago. Since then, I’ve had my appendix out, and had a daughter. But, like anyone who has lost a baby, I will always be haunted by what could have been done differently. If an artificial womb might save the life of a very sick 21-week-old foetus, could it also save a 20-week-old who was perfectly healthy, but unlucky enough to be inside a woman who was ill?

I swallow hard. “If the first time you put a human foetus in your system,” I say, “it will be one not viable otherwise, questions will come up about pushing the boundaries of viability. Can’t you imagine parents of even more premature babies wanting their child to have any chance an artificial womb might offer?”

“This is a really easy question,” he says. “This is a human – or a foetus, or a baby – that’s sick. If you had a three-year-old that was unwell and somebody was developing a new therapy, would you have any qualms about that?”

“Of course not.”

“So there you go. From our perspective, this is no different.”

In other words, so long as they have a chance to save a baby’s life, they will try to do it. But there are limits.

“We don’t think we are shifting the border of viability further and further: if you can’t get a catheter in and the heart is not sufficiently developed to drive blood through the system, it’s not going to work. So any concerns about harvesting eggs and putting them into these artificial devices are completely abrogated by that. It’s just not practically possible.”

Dr Anna Smajdor, a bioethicist at Oslo university who believes that pregnancy is barbaric. Photograph: courtesy of Anna SmajdorAs we get better at extending the lives of embryos outside the womb, and keeping ever more premature babies alive, there will come a time when those two points meet. The obstacles will be legal and ethical, not technological. IVF was once science fiction, then an ethical conundrum, then the cutting edge of assisted reproduction. Now it’s a normal part of making families. Once bags and tubes can replace a womb, pregnancy and birth will be fundamentally redefined. If gestation no longer has to take place inside a woman’s body, it will no longer be female. And the meaning of motherhood will also be changed, for ever.

“Pregnancy is barbaric,” Dr Anna Smajdor declares. “If there were any disease that caused the same problems, we would regard it as very serious.” I am sitting in her office at the University of Oslo, opposite a calendar featuring photographs of her cats. She is a bioethicist and associate professor of practical philosophy, but has the air of a mischievous teenager.

“The number of women who suffer tears and incontinence, and things that damage them for the rest of their lives is really high, yet it’s not adequately recognised,” she continues. “This is all tied up with the strong value we attach not just to motherhood, but to giving birth.”

I’ve been eager to meet Smajdor since I read her groundbreaking academic papers on artificial wombs. She argues that ectogenesis – reproduction outside the human body – would allow reproductive labour to be redistributed fairly in society, so there is a moral imperative for more research.

“There’s an unquestioned assumption that women will have babies, and a failure to notice how bizarre it is that we have to produce new human beings out of our own bodies. And how dangerous that is.”

To demonstrate her point, she tells me about a colleague having a wisdom tooth out. Smajdor suggested they film it, as a beautiful experience to savour: “Here it comes! And look, here’s the stitching! Wow – you did that without any painkillers!”

The comparison is completely perverse, but I can see her point. Our attitude to birth is very strange. There is blood, pain and stitching even if it all goes well, and we are meant to ignore it. Maternal mortality and stillbirth rates are going down globally, but Smajdor says that isn’t necessarily all good news. “The more medicine advances, the more women get scathed. I see a trajectory towards knowing so much about the foetus, and what’s good or bad for it, that women become almost ectogenetic gestators themselves, their whole function about maximising what’s good for the baby.”

Pregnancy is remarkable, but I have never felt more like a thing, being acted on by doctors

I have definitely felt like an ectogenetic gestator. I have had to lie back while a 20cm needle was plunged into my belly so doctors could extract my son’s DNA because something on a scan made them think he might have Down’s syndrome. (He didn’t, but then I got appendicitis.) I have had to stop myself from gagging while forcing down a cloying glucose concoction because a late scan of my daughter showed I might have gestational diabetes. (I didn’t.) I have had to lie with my legs clamped apart while a surgeon stitched up my cervix because a scan showed I was at risk of going into another early labour. Being pregnant is a remarkable experience, and I loved carrying my first child, but I have never felt more like a thing, being acted upon purely because my very dedicated doctors knew too much about what might be going on inside me.

Smajdor was “not very surprised” when she saw CHOP’s lambs. “Those people were clever in their – ” she chooses the word carefully – “marketing. And, of course, being unwilling to talk about ectogenesis is part of the PR approach.” Instead of pouring resources into saving premature babies, she says we should be growing them in artificial wombs from the start, “because it’s a trauma for the foetus, being removed from the uterus, even if it then goes into a Biobag and survives”.

Smajdor uses provocative ideas to raise difficult questions. It works: she has made me think about how messed up our notions of what “normal” childbirth, pregnancy and motherhood are.

If perfect ectogenesis could ever exist, there is a long list of women who would want to use it: women with epilepsy, bipolar disorder or cancer, for whom pregnancy would mean risking either their own or their foetuses’ lives by stopping or starting medication; women who have had their wombs removed for medical reasons. Ectogenesis will also help women in circumstances much less likely to attract public sympathy: social surrogacy clients and older women, whose male equivalents have babies without a thought. You could conceive an embryo while you’re young and grow it in a bag after you retire.

But perhaps the people most likely to be emancipated by this technology are those not born female: single men, gay men and trans women desperate for their own biological children. I ask Smajdor about the benefits of ectogenesis for them.

“I don’t support anyone’s right to have a child. I support people’s right not to have their body interfered with.” Then she leaves the world of philosophical logic for a moment. “Assuming we could get perfect ectogenesis, it seems like a thing we should do, in a fully just society. The problem is that our societies are not fully just. In a society that believes natural reproduction is the most amazing part of a woman’s life, ectogenesis is going to be very problematic, and more likely to be used in ways that are detrimental to women. ”

“What kind of ways?”

“When we talk about rescuing very premature babies, there’s a risk of a desire to rescue babies because their mother is not fit to carry the foetus,” Smajdor says. Across the world, inappropriate behaviour during pregnancy is increasingly viewed as child abuse. Since the 50s, dozens of US states have prosecuted women for using drugs while pregnant. If you can save a baby from the dangers of premature birth, would you not be prepared to save it from a reckless mother?

It’s easy to imagine a future where the kind of “help” already offered by employers in Silicon Valley and beyond, enabling staff to freeze their eggs so they can focus on their careers, might include the option to grow their babies in an artificial womb. Using a real womb, inside the body, could ultimately become a sign of poverty, of chaotic lives, of unplanned pregnancy, or of being a borderline-dangerous “freebirther”, choosing to have a baby without any medical input.

The greatest existential threat faced by unborn babies today doesn’t come from women “unfit” to be pregnant, but from unwilling mothers. Once a woman’s body is no longer the incubator, abortion can be both pro-choice and pro-life. In the ectogenetic future, foetuses aborted by mothers who didn’t want them to exist could be “rescued” and adopted. In that world, some women might seek out backstreet abortions that would end their babies’ lives, rather than legal ones that would allow them to live. It’s a horrifying thought. But it could happen if the foetus’s right to life trumps that of a woman to refuse to become a mother.

Artificial wombs will be an incredibly powerful new technology. How that power will manifest itself depends on who is demanding, making, controlling and paying for the technology. Once IVF became mainstream, research into treating fertility problems such as blocked fallopian tubes all but stopped. Why bother, if the problem can be circumvented by assisted reproduction? The same could happen with research that makes it easier and safer for women to have babies without being sliced, probed and torn. What’s the point, if the solution is already there?

Women gain so much more than we lose by bearing children: the creative power of being a mother, the right to choose whether to become a parent at all. Can the freedom to have babies without being pregnant be worth sacrificing any of this?

Full ectogenesis will not exist for decades, but artificial wombs are coming. We need to ensure that, when they do arrive, it’s in a society that values women for more than just their reproductive capacity, and that they are put to use for the benefit of people who can’t be pregnant for biological rather than social reasons. We do still have time. But the race to innovate means maybe not enough.

“This certainly is a project that would have sounded more like science fiction,” Emily Partridge says at the end of the CHOP video. “But over three years of doggedly pursuing it, it has become very real.”

This is an edited extract from Sex Robots & Vegan Meat: Adventures At The Frontier Of Birth, Food, Sex & Death, by Jenny Kleeman, published on 9 July by Picador at £16. 99. To order a copy for £14.61, go to guardianbookshop.com.

Little Nastya was born on Epiphany Eve. While the baby is sleeping, Evgenia's mother tells what a miracle the birth of her third child was for her.

“It was hard, hard and scary. You think in your head that the case is really unique, they barely survived, ”says Evgenia Baturina.

Evgenia did not know that she was pregnant. When she felt severe pain in her stomach, she went to the antenatal clinic at the place of residence, in Boguchar. The doctor diagnosed pregnancy, and, to the surprise of the future mother, the 34th week. The woman was admitted to the hospital, but the pain began to intensify. Doctors also could not determine the position of the fetus. And they decided to urgently hospitalize the pregnant woman in a perinatal center in Voronezh.

“She was transferred to us with a different diagnosis and impaired blood flow in the fetus. We didn't prepare at all. We found out that she had such a pregnancy during the abdominal excision, ”said Galina Nikonova, head of the obstetric remote center of the Voronezh Regional Hospital.

What the doctors saw during the operation was shocking. The almost fully formed fetus was not inside the uterus, but outside. The placenta attached to the appendages without damaging the vital organs. All this time the child developed normally. The emergency operation lasted an hour and a half - not much for such a difficult case, and the doctors performed it flawlessly.

The baby does not yet know how unique she is. But now she is already being cared for in the usual way, like all the other babies in the perinatal center.

Two kilograms one hundred grams - the baby was born at the 38th week of pregnancy. Five days of resuscitation monitoring with light respiratory support, then another week in the therapy department, and it became clear to the doctors that the child could be transferred to the ward with the mother. Today, their health is no longer a matter of concern to doctors.

“Statistically, 50% of these children are definitely born with some kind of anomaly. The fact that an almost full-term baby was born here, without any violations, this will probably be an isolated case in world practice, ”said Tatyana Gushchina, head of the obstetric department of the perinatal center in Voronezh.

There are only 17 such cases in the world when healthy babies were born. After all, an ectopic pregnancy is dangerous for both the mother and the child.

“Fertilization does not take place in the uterus. It takes place in the fallopian tube. For some reason, the fertilized egg fell out of the tube and stayed where it was not supposed to live, ”says Galina Nikonova, head of the obstetric remote center of the Voronezh Regional Hospital.

“A unique rare case. A fetal egg can attach to the liver, spleen, ovaries, intestines, and peritoneum. And, of course, delivery is very dangerous, because it threatens with great blood loss, ”says the head of the Institute of Obstetrics. Kulakova Roman Shmakov.

As a result of the operation, the doctors were able to save not only the life and health of the child, but also the reproductive functions of the mother. Now they are being prepared for release. At home in Boguchar, little Nastya is waiting for a large family: Evgenia has a son, an adult daughter, and even a grandson has already appeared.

"Real miracle". A resident of Voronezh was able to bear a child outside the uterus | HEALTH: Medicine | HEALTH

Faina Mania

Approximate reading time: 7 minutes

13435

A 38-year-old woman was unaware of her situation for a long time / Faina Mania / AiF

Voronezh doctors performed a unique operation - a child born outside the uterus was born in the perinatal center of VOKB No. 1. A 38-year-old resident of Boguchar, Voronezh Region, Evgeniya Baturina , unaware of anything, carried the baby in the abdominal cavity. At the same time, the girl, who was named Anastasia, was born completely healthy. This case is considered unique even by world standards.

AiF-Voronezh talked to the happy mother and the doctors.

"One in a Million"

According to the world statistics, the development of a child in the abdominal cavity occurs in approximately 0.4% of cases of ectopic pregnancy. In this case, the outcome is almost always unfavorable - the fetus does not survive under these conditions. Such a pregnancy is extremely dangerous for a woman. Maternal mortality reaches 20%.

Interestingly, for a long time Evgenia had no idea about her situation. As soon as she felt pain in her stomach, she went to the doctor at the Boguchar district hospital. Evgenia Baturina found out about her pregnancy at the 34th week. At the same time, ultrasound did not show that this was a very difficult case.

“When a woman sees a doctor at a short term, of course, first of all, it is checked whether this is a uterine pregnancy or not. In this case, the woman applied for a long time. Uzist saw a large fruit. I think he could not even imagine that a child could reach such a size while outside the womb. So it is impossible to blame the doctors of ultrasound diagnostics for not making a diagnosis right away. After all, they faced a one-in-a-million case. Yes, it was a fetus that was essentially "nowhere", just in the stomach. And if they found out about this at a short time, then, of course, they would not continue the pregnancy. Nature is such that pregnancy cannot develop outside the uterus. The fact that in this case the child grew up to 36 weeks and was born alive and healthy is a real miracle,” says head of the remote obstetric advisory center VOKB No. 1 Galina Nikonova .

The fact that the pregnancy was ectopic was already known on the operating table during the caesarean section. The woman was transported to Voronezh from the district hospital for a completely different reason.

“She was admitted to the Voronezh perinatal center at the 36th week of pregnancy. The fetus was in a transverse position, the woman complained of pain. Soon it became known about intra-abdominal bleeding. It was impossible to leave her in the district hospital. It was decided to urgently transport the patient, notes obstetrician-gynecologist of the perinatal center VOKB No. 1 Tatyana Gushchina . - What kind of diagnoses we did not put on her in absentia - starting with placental abruption and ending with uterine rupture. But that we are talking about an ectopic pregnancy, we could not even think. The patient arrived in Voronezh in a condition close to critical. And only when we started the operation, it became clear what we were dealing with. The situation was out of the ordinary. It was necessary to act quickly. A team of qualified doctors was urgently assembled. In total, 11 people participated in the operation, which lasted an hour and a half. A great role in the fact that the operation was successful was played by the coordinated work of all the staff of the perinatal center.

As a result, late in the evening on January 17, a healthy girl Anastasia was born without any deviations, weighing 2150 grams and 46 centimeters tall. Mom is fine too. In addition, the woman also has a fertile function.

“There are only 17 such cases worldwide”

According to the doctors, the woman was really lucky. If, for example, the placenta was attached to the vessels of the intestine, the result would not be so joyful. In this case, several meters of the intestine would have to be resected (removed - ed.), and the mother would have remained disabled. There was a high probability of a fatal outcome for both - both the mother and the baby.

“For the first time in 44 years of work, I have encountered for the first time a healthy child born in such a situation. When it turned out what we were dealing with, I confess, I was scared, - says Galina Nikonova. – In this situation, another logical question arises. How could a woman, being at such an impressive time, not notice her position? Despite being pregnant, she was menstruating. And all because the uterus was not involved in the process. Perhaps the placenta gave some kind of failure, but they were insignificant.

The resident of Boguchar herself, for whom this child was the third, admits that she did not have any special feelings. She continued to work until the moment when she first went to the doctor. And on the 34th week, I had to urgently go on maternity leave.

“I didn't feel sick, I didn't feel bad. I myself am not very thin, so the increase in the abdomen was not evident. Only when everything inside began to hurt, I went to the hospital, - Evgenia Baturina admits. - When I found out about the pregnancy, of course, I was shocked. Couldn't believe it. Moreover, I was pregnant twice before - I have 19-year-old daughter and six-year-old son - but the sensations were completely different. I worked until the last - a confectioner in a local restaurant. On December 19, she was registered for pregnancy, and almost a month later Anastasia was born. I found out exactly what kind of pregnancy I had only after the operation. So I didn't get scared. But I still can't believe it. Doctors repeat: "This is a real miracle." And indeed, some kind of miracle. Many thanks to the doctors for saving me and my daughter. In Boguchar, probably, they would not have been able to save. Now I can say for sure that I will not give birth again.

The mother says that she and her daughter are now feeling well and are preparing for discharge. The baby is gradually gaining weight - in two and a half weeks she recovered by 300 grams. Now Evgenia is striving to return as soon as possible to her native Boguchar, where her husband, children and grandson are waiting for her.

“What is unique about this case? There are several components. Firstly, we encountered an ectopic pregnancy, which has grown to such a period. Secondly, despite the fact that the child was in abnormal conditions, his development was fully consistent with the period. Thirdly, the obstetric service worked in such a way that it was able to take the situation into its own hands at the last critical moment and prevent massive bleeding and death of the mother and child. Fourthly, the child was born healthy, emphasizes chief freelance neonatologist of the Department of Health of the Voronezh Region Lyudmila Ippolitova . – Yes, in our practice there were cases of ectopic pregnancy, but they all ended in the death of the fetus. According to open sources, over the past 150 years there have been only 17 such cases in the world with a successful delivery. And now we have witnessed another miracle.”

See also:

- "We had little chance." Moms - about the fight for the health of premature babies →

- "Protection function is activated". Why pregnancy changes a woman →

- In Voronezh, a baby born outside the uterus was born →

Voronezh birth of a child

Next article

You may also be interested in

- “Now there is no concept of “old-term woman”.