Dating ultrasound accuracy

Methods for Estimating the Due Date

Number 700 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 611, October 2014. Reaffirmed 2022)

Committee on Obstetric Practice

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine

Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine

This Committee Opinion was developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice, in collaboration with members Christian M. Pettker, MD; James D. Goldberg, MD; and Yasser Y. El-Sayed, MD; the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine’s liaison member Joshua A. Copel, MD; and the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine.

This document reflects emerging clinical and scientific advances as of the date issued and is subject to change. The information should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed.

ABSTRACT: Accurate dating of pregnancy is important to improve outcomes and is a research and public health imperative. As soon as data from the last menstrual period, the first accurate ultrasound examination, or both are obtained, the gestational age and the estimated due date (EDD) should be determined, discussed with the patient, and documented clearly in the medical record. Subsequent changes to the EDD should be reserved for rare circumstances, discussed with the patient, and documented clearly in the medical record. A pregnancy without an ultrasound examination that confirms or revises the EDD before 22 0/7 weeks of gestational age should be considered suboptimally dated. When determined from the methods outlined in this document for estimating the due date, gestational age at delivery represents the best obstetric estimate for the purpose of clinical care and should be recorded on the birth certificate. For the purposes of research and surveillance, the best obstetric estimate, rather than estimates based on the last menstrual period alone, should be used as the measure for gestational age.

Recommendations

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, and the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine make the following recommendations regarding the method for estimating gestational age and due date:

Ultrasound measurement of the embryo or fetus in the first trimester (up to and including 13 6/7 weeks of gestation) is the most accurate method to establish or confirm gestational age.

If pregnancy resulted from assisted reproductive technology (ART), the ART-derived gestational age should be used to assign the estimated due date (EDD). For instance, the EDD for a pregnancy that resulted from in vitro fertilization should be assigned using the age of the embryo and the date of transfer.

As soon as data from the last menstrual period (LMP), the first accurate ultrasound examination, or both are obtained, the gestational age and the EDD should be determined, discussed with the patient, and documented clearly in the medical record. Subsequent changes to the EDD should be reserved for rare circumstances, discussed with the patient, and documented clearly in the medical record.

When determined from the methods outlined in this document for estimating the due date, gestational age at delivery represents the best obstetric estimate for the purpose of clinical care and should be recorded on the birth certificate. For the purposes of research and surveillance, the best obstetric estimate, rather than estimates based on the LMP alone, should be used as the measure for gestational age.

A pregnancy without an ultrasound examination that confirms or revises the EDD before 22 0/7 weeks of gestational age should be considered suboptimally dated.

Introduction

An accurately assigned EDD early in prenatal care is among the most important results of evaluation and history taking. This information is vital for timing of appropriate obstetric care; scheduling and interpretation of certain antepartum tests; determining the appropriateness of fetal growth; and designing interventions to prevent preterm births, postterm births, and related morbidities. Appropriately performed obstetric ultrasonography has been shown to accurately determine fetal gestational age 1. A consistent and exacting approach to accurate dating is also a research and public health imperative because of the influence of dating on investigational protocols and vital statistics. This Committee Opinion outlines a standardized approach to estimate gestational age and the anticipated due date. It is understood that within the ranges suggested by different studies, no perfect evidence exists to establish a single-point cutoff in the difference between clinical and ultrasonographic EDD to prompt changing a pregnancy’s due date. However, there is great usefulness in having a single, uniform standard within and between institutions that have access to high-quality ultrasonography (as most, if not all, U.S. obstetric facilities do). Accordingly, in creating recommendations and the associated summary table, single-point cutoffs were chosen based on expert review.

It is understood that within the ranges suggested by different studies, no perfect evidence exists to establish a single-point cutoff in the difference between clinical and ultrasonographic EDD to prompt changing a pregnancy’s due date. However, there is great usefulness in having a single, uniform standard within and between institutions that have access to high-quality ultrasonography (as most, if not all, U.S. obstetric facilities do). Accordingly, in creating recommendations and the associated summary table, single-point cutoffs were chosen based on expert review.

Background

Traditionally, determining the first day of the LMP is the first step in establishing the EDD. By convention, the EDD is 280 days after the first day of the LMP. Because this practice assumes a regular menstrual cycle of 28 days, with ovulation occurring on the 14th day after the beginning of the menstrual cycle, this practice does not account for inaccurate recall of the LMP, irregularities in cycle length, or variability in the timing of ovulation. It has been reported that approximately one half of women accurately recall their LMP 2 3 4. In one study, 40% of the women randomized to receive first-trimester ultrasonography had their EDD adjusted because of a discrepancy of more than 5 days between ultrasound dating and LMP dating 5. Estimated due dates were adjusted in only 10% of the women in the control group who had ultrasonography in the second trimester, which suggests that first-trimester ultrasound examination can improve the accuracy of the EDD, even when the first day of the LMP is known.

It has been reported that approximately one half of women accurately recall their LMP 2 3 4. In one study, 40% of the women randomized to receive first-trimester ultrasonography had their EDD adjusted because of a discrepancy of more than 5 days between ultrasound dating and LMP dating 5. Estimated due dates were adjusted in only 10% of the women in the control group who had ultrasonography in the second trimester, which suggests that first-trimester ultrasound examination can improve the accuracy of the EDD, even when the first day of the LMP is known.

Accurate determination of gestational age can positively affect pregnancy outcomes. For instance, one study found a reduction in the need for postterm inductions in a group of women randomized to receive routine first-trimester ultrasonography compared with women who received only second-trimester ultrasonography 5. A Cochrane review concluded that ultrasonography can reduce the need for postterm induction and lead to earlier detection of multiple gestations 6. Because decisions to change the EDD significantly affect pregnancy management, their implications should be discussed with patients and recorded in the medical record.

Because decisions to change the EDD significantly affect pregnancy management, their implications should be discussed with patients and recorded in the medical record.

Clinical Considerations in the First Trimester

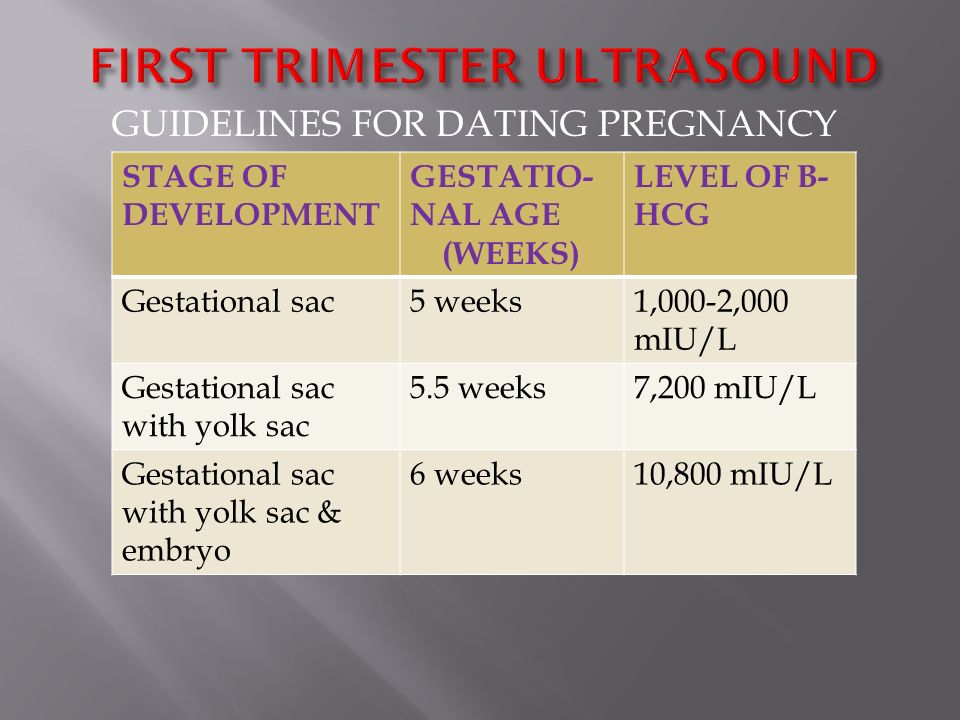

Ultrasound measurement of the embryo or fetus in the first trimester (up to and including 13 6/7 weeks of gestation) is the most accurate method to establish or confirm gestational age 3 4 7 8 9 10. Up to and including 13 6/7 weeks of gestation, gestational age assessment based on measurement of the crown–rump length (CRL) has an accuracy of ±5–7 days 11 12 13 14. Measurements of the CRL are more accurate the earlier in the first trimester that ultrasonography is performed 11 15 16 17 18. The measurement used for dating should be the mean of three discrete CRL measurements when possible and should be obtained in a true midsagittal plane, with the genital tubercle and fetal spine longitudinally in view and the maximum length from cranium to caudal rump measured as a straight line 8 11. Mean sac diameter measurements are not recommended for estimating the due date. Beyond measurements of 84 mm (corresponding to approximately 14 0/7 weeks of gestation), the accuracy of the CRL to estimate gestational age decreases, and in these cases, other second-trimester biometric parameters (discussed in the following section) should be used for dating. If ultrasound dating before 14 0/7 weeks of gestation differs by more than 7 days from LMP dating, the EDD should be changed to correspond with the ultrasound dating. Dating changes for smaller discrepancies are appropriate based on how early in the first trimester the ultrasound examination was performed and clinical assessment of the reliability of the LMP date Table 1. For instance, before 9 0/7 weeks of gestation, a discrepancy of more than 5 days is an appropriate reason for changing the EDD. If the patient is unsure of her LMP, dating should be based on ultrasound examination estimates (ideally obtained before or at 13 6/7 weeks of gestation), with the earliest ultrasound examination of a CRL measurement prioritized as the most reliable.

Mean sac diameter measurements are not recommended for estimating the due date. Beyond measurements of 84 mm (corresponding to approximately 14 0/7 weeks of gestation), the accuracy of the CRL to estimate gestational age decreases, and in these cases, other second-trimester biometric parameters (discussed in the following section) should be used for dating. If ultrasound dating before 14 0/7 weeks of gestation differs by more than 7 days from LMP dating, the EDD should be changed to correspond with the ultrasound dating. Dating changes for smaller discrepancies are appropriate based on how early in the first trimester the ultrasound examination was performed and clinical assessment of the reliability of the LMP date Table 1. For instance, before 9 0/7 weeks of gestation, a discrepancy of more than 5 days is an appropriate reason for changing the EDD. If the patient is unsure of her LMP, dating should be based on ultrasound examination estimates (ideally obtained before or at 13 6/7 weeks of gestation), with the earliest ultrasound examination of a CRL measurement prioritized as the most reliable.

If pregnancy resulted from ART, the ART-derived gestational age should be used to assign the EDD. For instance, the EDD for a pregnancy that resulted from in vitro fertilization should be assigned using the age of the embryo and the date of transfer. For example, for a day-5 embryo, the EDD would be 261 days from the embryo replacement date. Likewise, the EDD for a day-3 embryo would be 263 days from the embryo replacement date.

Clinical Considerations in the Second Trimester

Using a single ultrasound examination in the second trimester to assist in determining the gestational age enables simultaneous fetal anatomic evaluation. However, the range of second-trimester gestational ages (14 0/7 weeks to 27 6/7 weeks of gestation) introduces greater variability and complexity, which can affect revision of LMP dating and assignment of a final EDD. With rare exception, if a first-trimester ultrasound examination was performed, especially one consistent with LMP dating, gestational age should not be adjusted based on a second-trimester ultrasound examination. Ultrasonography dating in the second trimester typically is based on regression formulas that incorporate variables such as

Ultrasonography dating in the second trimester typically is based on regression formulas that incorporate variables such as

the biparietal diameter and head circumference (measured in transverse section of the head at the level of the thalami and cavum septi pellucidi; the cerebellar hemispheres should not be visible in this scanning plane)

the femur length (measured with full length of the bone perpendicular to the ultrasound beam, excluding the distal femoral epiphysis)

the abdominal circumference (measured in symmetrical, transverse round section at the skin line, with visualization of the vertebrae and in a plane with visualization of the stomach, umbilical vein, and portal sinus) 8

Other biometric variables, such as additional long bones and the transverse cerebellar diameter, also can play a role.

Gestational age assessment by ultrasonography in the first part of the second trimester (between 14 0/7 weeks and 21 6/7 weeks of gestation, inclusive) is based on a composite of fetal biometric measurements and has an accuracy of 7–10 days 19 20 21 22. If dating by ultrasonography performed between 14 0/7 weeks and 15 6/7 weeks of gestation (inclusive) varies from LMP dating by more than 7 days, or if ultrasonography dating between 16 0/7 weeks and 21 6/7 weeks of gestation varies by more than 10 days, the EDD should be changed to correspond with the ultrasonography dating Table 1.Between 22 0/7 weeks and 27 6/7 weeks of gestation, ultrasonography dating has an accuracy of ± 10–14 days 19. If ultrasonography dating between 22 0/7 weeks and 27 6/7 weeks of gestation (inclusive) varies by more than 14 days from LMP dating, the EDD should be changed to correspond with the ultrasonography dating Table 1. Date changes for smaller discrepancies (10–14 days) are appropriate based on how early in this second-trimester range the ultrasound examination was performed and on clinician assessment of LMP reliability. Of note, pregnancies without an ultrasound examination that confirms or revises the EDD before 22 0/7 weeks of gestational age should be considered suboptimally dated (see also Committee Opinion 688, Management of Suboptimally Dated Pregnancies 23).

If dating by ultrasonography performed between 14 0/7 weeks and 15 6/7 weeks of gestation (inclusive) varies from LMP dating by more than 7 days, or if ultrasonography dating between 16 0/7 weeks and 21 6/7 weeks of gestation varies by more than 10 days, the EDD should be changed to correspond with the ultrasonography dating Table 1.Between 22 0/7 weeks and 27 6/7 weeks of gestation, ultrasonography dating has an accuracy of ± 10–14 days 19. If ultrasonography dating between 22 0/7 weeks and 27 6/7 weeks of gestation (inclusive) varies by more than 14 days from LMP dating, the EDD should be changed to correspond with the ultrasonography dating Table 1. Date changes for smaller discrepancies (10–14 days) are appropriate based on how early in this second-trimester range the ultrasound examination was performed and on clinician assessment of LMP reliability. Of note, pregnancies without an ultrasound examination that confirms or revises the EDD before 22 0/7 weeks of gestational age should be considered suboptimally dated (see also Committee Opinion 688, Management of Suboptimally Dated Pregnancies 23).

Clinical Considerations in the Third Trimester

Gestational age assessment by ultrasonography in the third trimester (28 0/7 weeks of gestation and beyond) is the least reliable method, with an accuracy of ± 21–30 days 19 20 24. Because of the risk of redating a small fetus that may be growth restricted, management decisions based on third-trimester ultrasonography alone are especially problematic; therefore, decisions need to be guided by careful consideration of the entire clinical picture and may require close surveillance, including repeat ultrasonography, to ensure appropriate interval growth. The best available data support adjusting the EDD of a pregnancy if the first ultrasonography in the pregnancy is performed in the third trimester and suggests a discrepancy in gestational dating of more than 21 days.

Conclusion

Accurate dating of pregnancy is important to improve outcomes and is a research and public health imperative. As soon as data from the LMP, the first accurate ultrasound examination, or both are obtained, the gestational age and the EDD should be determined, discussed with the patient, and documented clearly in the medical record. Subsequent changes to the EDD should be reserved for rare circumstances, discussed with the patient, and documented clearly in the medical record. When determined from the methods outlined in this document for estimating the due date, gestational age at delivery represents the best obstetric estimate for the purpose of clinical care and should be recorded on the birth certificate. For the purposes of research and surveillance, the best obstetric estimate, rather than estimates based on the LMP alone, should be used as the measure for gestational age. A pregnancy without an ultrasound examination that confirms or revises the EDD before 22 0/7 weeks of gestational age should be considered suboptimally dated.

Subsequent changes to the EDD should be reserved for rare circumstances, discussed with the patient, and documented clearly in the medical record. When determined from the methods outlined in this document for estimating the due date, gestational age at delivery represents the best obstetric estimate for the purpose of clinical care and should be recorded on the birth certificate. For the purposes of research and surveillance, the best obstetric estimate, rather than estimates based on the LMP alone, should be used as the measure for gestational age. A pregnancy without an ultrasound examination that confirms or revises the EDD before 22 0/7 weeks of gestational age should be considered suboptimally dated.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, and the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine recognize the advantages of a single dating paradigm being used within and between institutions that provide obstetric care. Table 1 provides guidelines for estimating the due date based on ultrasonography and the LMP in pregnancy, and provides single-point cutoffs and ranges based on available evidence and expert opinion.

Copyright May 2017 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on the Internet, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Requests for authorization to make photocopies should be directed to Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400.

ISSN 1074-861X

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 409 12th Street, SW, PO Box 96920, Washington, DC 20090-6920

Methods for estimating the due date. Committee Opinion No. 700.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e150–4.

Pregnancy Dating - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf

John A. Morgan; Danielle B. Cooper.

Author Information and Affiliations

Last Update: September 12, 2022.

Continuing Education Activity

The most important step in the initial evaluation of any pregnant patient is establishing an accurate delivery date (due date). Accurate knowledge of the gestational age is important for numerous reasons. A patient's gestational age determines the appropriate intervals for prenatal care visits, as well as the timing of certain interventions. This activity describes the different methods to date a pregnancy.

Objectives:

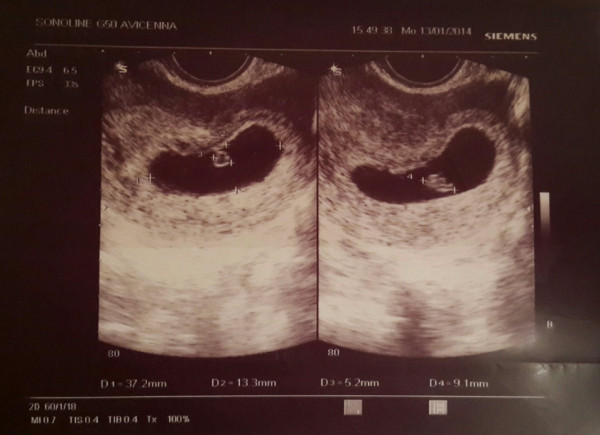

Identify the technique of performing a transvaginal ultrasound for pregnancy dating.

Describe the indications for dating a pregnancy.

Review the clinical significance of dating a pregnancy.

Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving pregnancy dating and improving patient outcomes.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

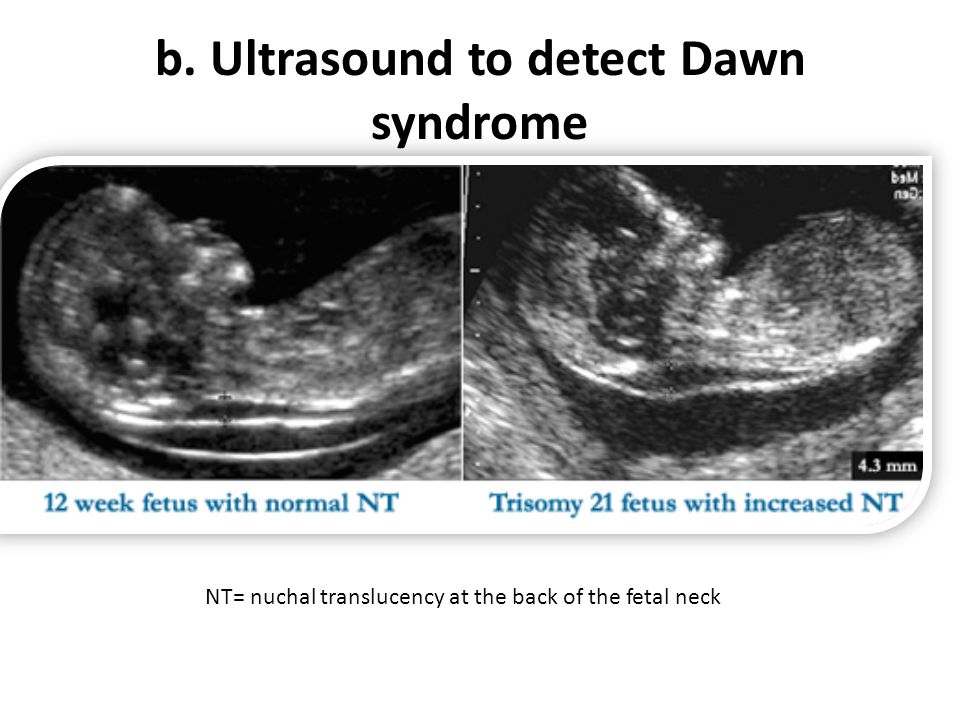

The most important step in the initial evaluation of any pregnant patient is establishing an accurate delivery date (due date)[1]. Accurate knowledge of the gestational age is important for numerous reasons. A patient’s gestational age determines the appropriate intervals for prenatal care visits, as well as the timing of certain interventions[1]. For example, certain antenatal screening tests like the quadruple marker screen (screening test for fetal aneuploidy and open neural tube defects) must be performed with accurate knowledge of the gestational age for an accurate calculation of lab values. In patients with a history of preterm labor and delivery, screening tests and interventions early in pregnancy can be used to prevent preterm labor in any subsequent pregnancy[1]. As pregnancy progresses, accurate and optimal pregnancy dating is important when deciding on the timing of both medically indicated and elective deliveries[1].

Accurate knowledge of the gestational age is important for numerous reasons. A patient’s gestational age determines the appropriate intervals for prenatal care visits, as well as the timing of certain interventions[1]. For example, certain antenatal screening tests like the quadruple marker screen (screening test for fetal aneuploidy and open neural tube defects) must be performed with accurate knowledge of the gestational age for an accurate calculation of lab values. In patients with a history of preterm labor and delivery, screening tests and interventions early in pregnancy can be used to prevent preterm labor in any subsequent pregnancy[1]. As pregnancy progresses, accurate and optimal pregnancy dating is important when deciding on the timing of both medically indicated and elective deliveries[1].

Anatomy and Physiology

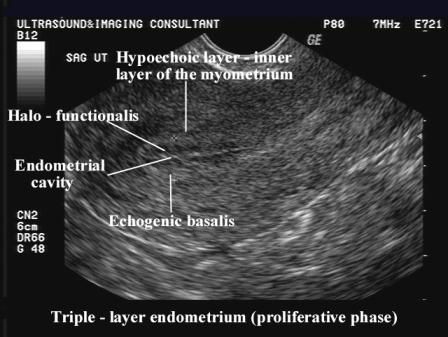

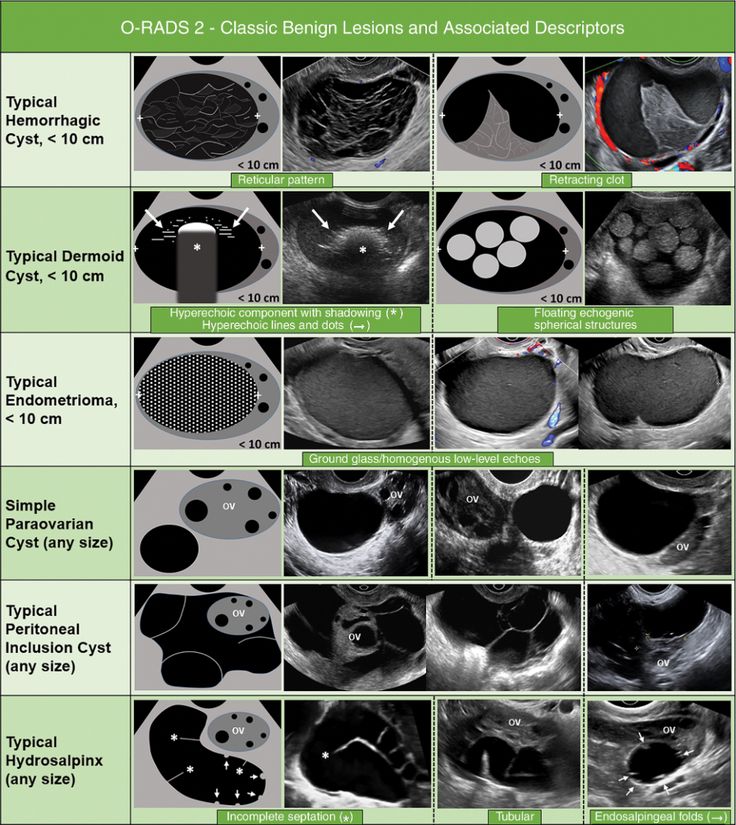

Pregnancy ultrasound involves an anatomic survey of uterus and adnexa[2]. On the initial ultrasound, it is important to establish the location of the gestational sac, confirm the intrauterine location and document the presence or absence of yolk sac, fetal pole, and fetal number[2]. If a fetal pole is seen, the presence of fetal heart tones should be documented[2]. If ultrasound is performed beyond 18 weeks of gestation, a full fetal anatomic survey is possible[2].

If a fetal pole is seen, the presence of fetal heart tones should be documented[2]. If ultrasound is performed beyond 18 weeks of gestation, a full fetal anatomic survey is possible[2].

Indications

For appropriate management of any pregnancy, practitioners must establish gestational age[1]. All pregnancies should have either abdominal or transvaginal ultrasound to confirm or establish a gestational age before 22 0/7 weeks[1]. Any pregnancy that does not meet this criterion should be considered sub-optimally dated[3].

Contraindications

Ultrasound has been used in obstetrics for over 50 years and is safe when used appropriately[2]. Energy used to obtain ultrasound images does have an effect on tissue. For this reason, ultrasound should only be used when it is clinically indicated and for the shortest amount of time possible[4].

Equipment

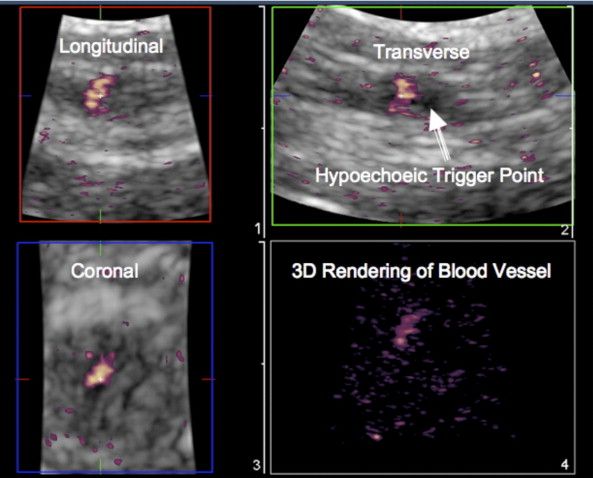

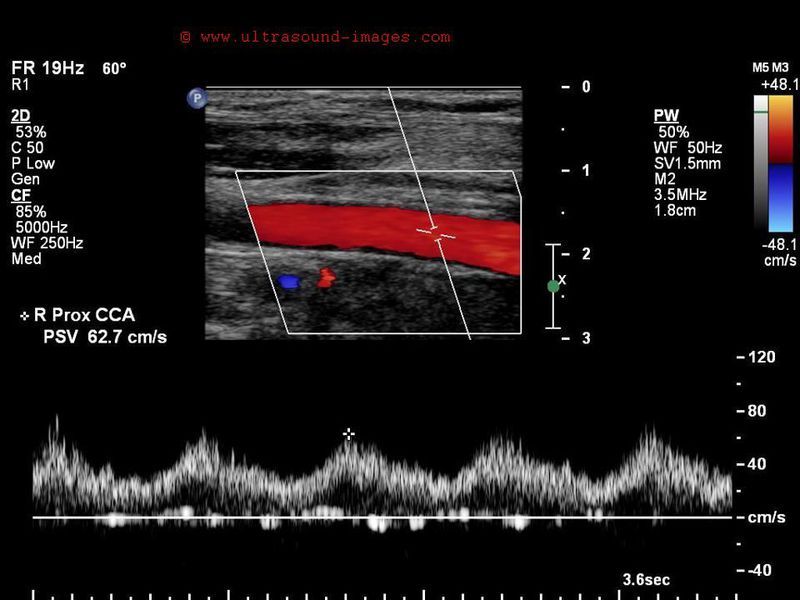

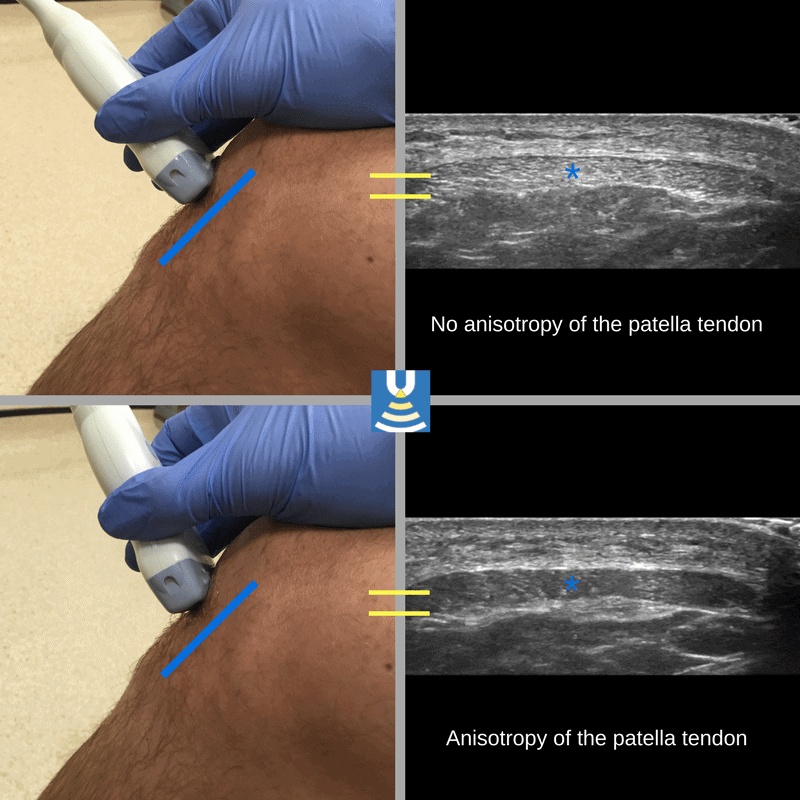

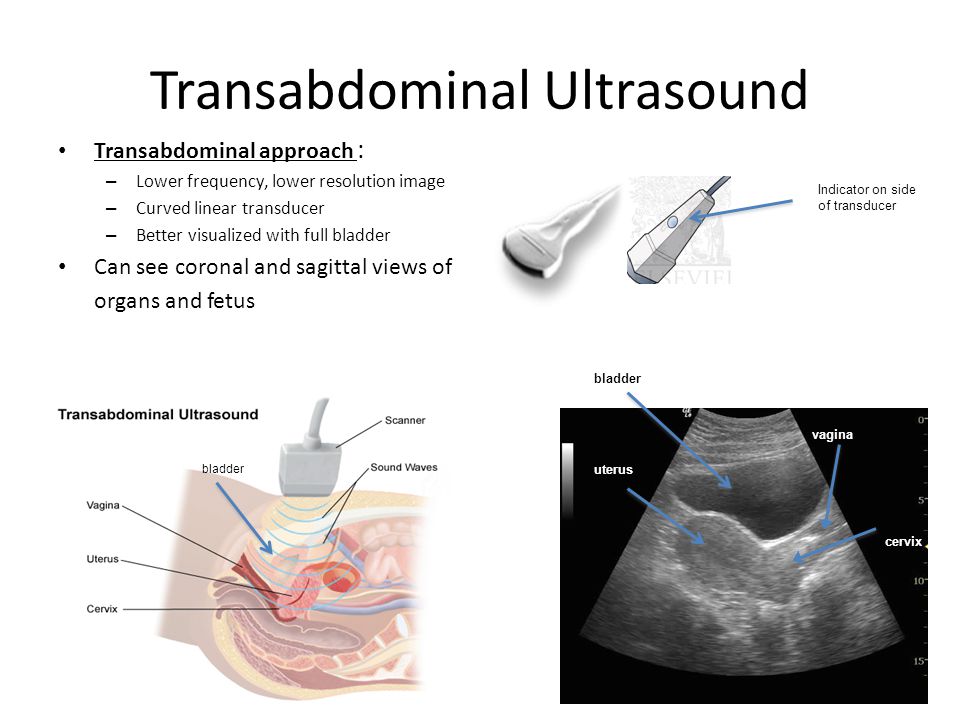

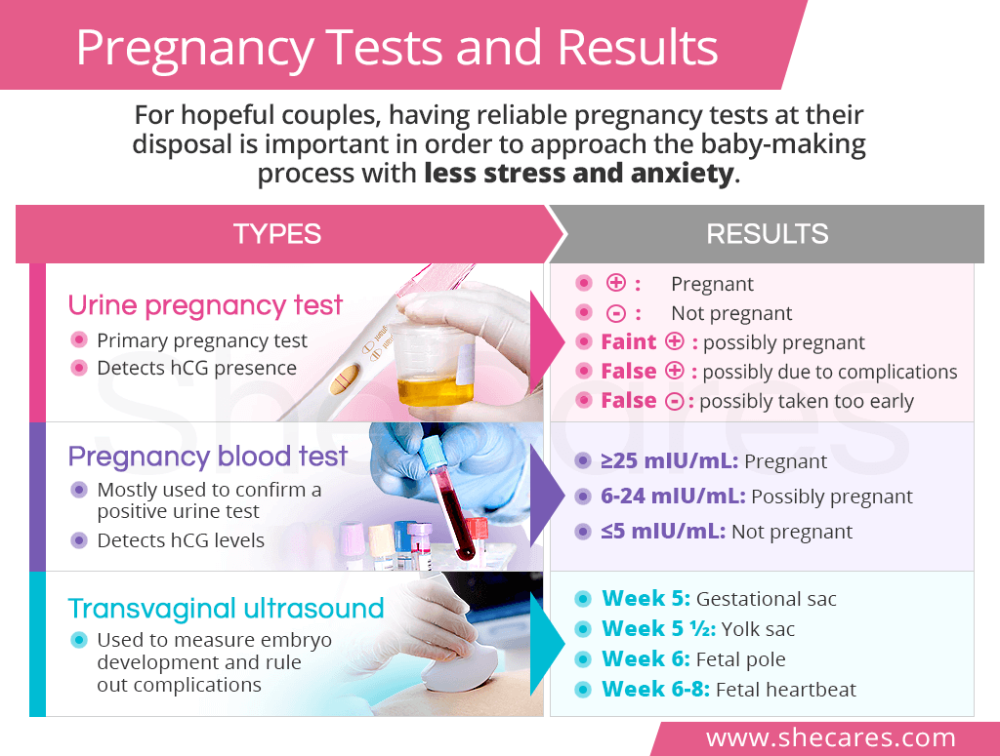

When using the patient's last menstrual period to establish pregnancy dating, Naegele's rule requires the use of a calendar[1]. Ultrasound is the most reliable method to establish pregnancy dating, particularly first-trimester ultrasound[1]. Transvaginal ultrasound utilizes 6 MHz to 10 MHz ultrasound probe. This probe has a higher frequency than transabominal ultrasound probes, which can show intrauterine structures approximately one week earlier in gestation[4]. Beyond eight weeks, transabdominal ultrasound is typically satisfactory for evaluation of pregnancy[4]. Transabdominal ultrasound utilizes a curvilinear ultrasound probe with a frequency of 3 MHz to 6 MHz which provides good penetration into the uterus[4]. Abdominal obesity or a retroverted uterus may cause difficulty during transabdominal approach. Both transabdominal and transvaginal approaches require the use of an acoustic gel[4].

Ultrasound is the most reliable method to establish pregnancy dating, particularly first-trimester ultrasound[1]. Transvaginal ultrasound utilizes 6 MHz to 10 MHz ultrasound probe. This probe has a higher frequency than transabominal ultrasound probes, which can show intrauterine structures approximately one week earlier in gestation[4]. Beyond eight weeks, transabdominal ultrasound is typically satisfactory for evaluation of pregnancy[4]. Transabdominal ultrasound utilizes a curvilinear ultrasound probe with a frequency of 3 MHz to 6 MHz which provides good penetration into the uterus[4]. Abdominal obesity or a retroverted uterus may cause difficulty during transabdominal approach. Both transabdominal and transvaginal approaches require the use of an acoustic gel[4].

Personnel

A physician typically selects the appropriate estimated delivery date for a pregnant patient. In certain circumstances, an ultrasound technician will be the first person to evaluate a pregnancy using ultrasound. Ultrasound reported estimated date of delivery, as well as other dating methods, should be compared by the treating clinician to choose the best clinical estimate of gestational age using the rules described below[1].

Ultrasound reported estimated date of delivery, as well as other dating methods, should be compared by the treating clinician to choose the best clinical estimate of gestational age using the rules described below[1].

Preparation

Patient preparation before ultrasound varies depending on which approach is used. For transabdominal ultrasound, a full bladder is helpful but not required[4]. For a transvaginal ultrasound, a full bladder can displace the uterus posteriorly and out of the field of view of the transvaginal ultrasound probe[4]. For this reason, it is recommended to perform transvaginal ultrasound with an empty bladder[4].

Abdominal ultrasound approach may be performed in the supine position[4]. The transvaginal approach should be performed with the patient in the lithotomy position, with the patient's buttocks at the end of the table allowing for a complete range of motion with the transvaginal ultrasound probe[4].

Technique

One method of estimating the delivery date is by using the patient's last menstrual cycle[1]. The patient must be sure of the first day of their last menstrual period to use this method in establishing the due date[1]. Adding seven days and then nine months to the patient’s last menstrual period (or 280 days) will give an estimated delivery date[1]. This technique assumes that the patient has a normal 28-day menstrual cycle and ovulates on day 14 of that cycle[1].

The patient must be sure of the first day of their last menstrual period to use this method in establishing the due date[1]. Adding seven days and then nine months to the patient’s last menstrual period (or 280 days) will give an estimated delivery date[1]. This technique assumes that the patient has a normal 28-day menstrual cycle and ovulates on day 14 of that cycle[1].

Fundal height measurement is a physical exam parameter that can be used to estimate gestational age[5]. The distance from the uterine fundus to the pubic symphysis defines fundal height measurement[5]. Measurement should be performed using a non-elastic tape measure, and the patient should have an empty bladder[5]. The most common use for fundal height measurement is recording the trend of this measurement to screen for appropriate fetal growth throughout gestation[5]. The usefulness of fundal height measurement in any circumstance has varied widely throughout the literature but can be helpful in resource-poor areas for an estimation of gestational age[5]. The assumption with fundal height measurement is that the measurement in centimeters from uterine fundus to pubic symphysis is equal to the patient's gestational age[5]. Uterine fibroids, amniotic fluid abnormalities, increased maternal body mass index (BMI), and fetal growth abnormalities are some examples of circumstances that can alter the accuracy of fundal height measurement[5].

The assumption with fundal height measurement is that the measurement in centimeters from uterine fundus to pubic symphysis is equal to the patient's gestational age[5]. Uterine fibroids, amniotic fluid abnormalities, increased maternal body mass index (BMI), and fetal growth abnormalities are some examples of circumstances that can alter the accuracy of fundal height measurement[5].

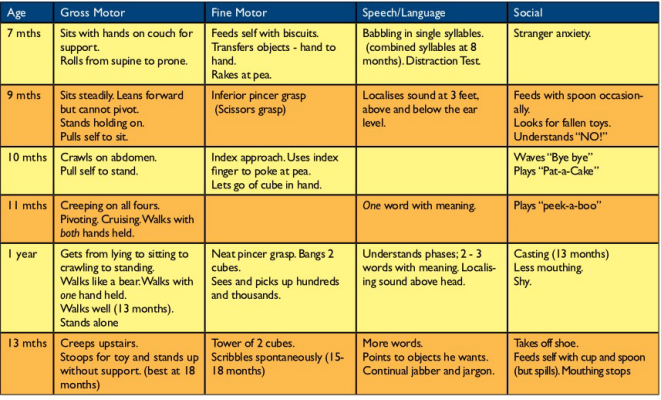

First-trimester ultrasound (ultrasound before 13 weeks and 6/7 days) is the most accurate method to establish or confirm gestation age in pregnancy[1]. First-trimester ultrasound can be performed either trans-vaginally or trans-abdominally. Crown-rump length is used for pregnancy dating the first trimester[1]. The average of three crown-rump length measurements is used to improve accuracy[1]. When the crown-rump length exceeds 84 mm (approximately 14 weeks and 0/7 days), the accuracy decreases, and full fetal biometry should be used to approximate the gestational age[1]. First-trimester ultrasound has an accuracy of +/- 5 to 7 days[1]. Last menstrual cycle, if known, should be used to estimate the gestational age before an ultrasound[1]. If the ultrasound is performed at less than 9 0/7 weeks, and the ultrasound dating differs by less than or equal to five days, the last menstrual period should be used for gestational age determination. If the estimated date of delivery in this circumstance differs by more than five days, the ultrasound determined estimated date of delivery should be used[1]. An ultrasound performed between 9 0/7 weeks and 13 6/7 weeks, can differ by seven days. If the ultrasound-determined estimated date of delivery differs by more than seven days, the ultrasound-estimated date of delivery should be used. If the ultrasound-estimated date of delivery differs by less than seven days, the last menstrual period should be used[1].

Last menstrual cycle, if known, should be used to estimate the gestational age before an ultrasound[1]. If the ultrasound is performed at less than 9 0/7 weeks, and the ultrasound dating differs by less than or equal to five days, the last menstrual period should be used for gestational age determination. If the estimated date of delivery in this circumstance differs by more than five days, the ultrasound determined estimated date of delivery should be used[1]. An ultrasound performed between 9 0/7 weeks and 13 6/7 weeks, can differ by seven days. If the ultrasound-determined estimated date of delivery differs by more than seven days, the ultrasound-estimated date of delivery should be used. If the ultrasound-estimated date of delivery differs by less than seven days, the last menstrual period should be used[1].

The performance of a first-trimester ultrasound is not always possible. Patients occasionally initiate prenatal care in the second trimester, or they may not present to a facility with ultrasound capability. In resource-poor areas, an initial ultrasound should be performed between 18 to 20 weeks[2]. Ultrasound between 18 to 20 weeks will allow both optimal dating criteria and detailed anatomical survey of the fetus[2]. Second-trimester ultrasound estimates estimated date of delivery with fetal measurements of biparietal diameter, head circumference, abdominal circumference and femur length[1].

In resource-poor areas, an initial ultrasound should be performed between 18 to 20 weeks[2]. Ultrasound between 18 to 20 weeks will allow both optimal dating criteria and detailed anatomical survey of the fetus[2]. Second-trimester ultrasound estimates estimated date of delivery with fetal measurements of biparietal diameter, head circumference, abdominal circumference and femur length[1].

The accuracy of second-trimester ultrasound (between 14 0/7 weeks and 27 6/7 weeks) is widely variable[2]. The earlier in the second trimester that an ultrasound is performed, the more accurate gestational age measurement[2]. If a first-trimester ultrasound has been used to confirm or establish an estimated date of delivery, a second-trimester ultrasound should not be used to adjust the estimated date of delivery[1]. If ultrasound is performed between 14 0/7 and 15 6/7 weeks and the date of delivery as estimated by the last menstrual period differs by more than seven days, the ultrasound-estimated date of delivery should be used for pregnancy management[1]. If ultrasound is performed between 16 0/7 and 21 6/7 weeks and the estimated date of delivery by last menstrual period differs by more than ten days, the ultrasound-estimated date of delivery should be used[1]. Pregnancies without confirmation or revision of gestational age by ultrasound before 22 0/7 weeks are considered sub-optimally dated[3]. Beyond 22 0/7 weeks until 27 6/7 weeks, if the last menstrual period-determined estimated date of delivery differs by more than 14 days, the ultrasound estimated date of delivery should be used[1].

If ultrasound is performed between 16 0/7 and 21 6/7 weeks and the estimated date of delivery by last menstrual period differs by more than ten days, the ultrasound-estimated date of delivery should be used[1]. Pregnancies without confirmation or revision of gestational age by ultrasound before 22 0/7 weeks are considered sub-optimally dated[3]. Beyond 22 0/7 weeks until 27 6/7 weeks, if the last menstrual period-determined estimated date of delivery differs by more than 14 days, the ultrasound estimated date of delivery should be used[1].

Third-trimester ultrasound (beyond 28 0/7 weeks) is the most inaccurate method for pregnancy dating with an accuracy of +/- 21-30 days[1]. One major concern with third trimester dating ultrasound is underestimating the gestational age of a growth-restricted fetus[1]. Management decisions based on third-trimester ultrasound alone can be difficult for this reason[1].

Complications

Once the estimated date of delivery is established and confirmed with first or second-trimester ultrasound, it should be carefully documented in the medical record for use by other health care providers if needed. Changes to the estimated delivery date can have significant implications for pregnancy management, so before making a change to the patient's estimated date of delivery, the patient should be counseled on possible implications[1].

Changes to the estimated delivery date can have significant implications for pregnancy management, so before making a change to the patient's estimated date of delivery, the patient should be counseled on possible implications[1].

Clinical Significance

Establishing an accurate gestational age and estimated delivery date is the most important step in the management of any pregnancy[1]. Accurate knowledge of gestational age allows laboratory and screening tests to be performed at the appropriate time in the pregnancy[1]. Optimal dating, before 22 0/7 weeks, will enable accurate assessment of fetal growth as the pregnancy progresses[3]. Sub-optimally dated pregnancies, due to the error of ultrasound at advanced gestational age, can be difficult to manage because of the uncertainty of the pregnancy dating[3]. Elective delivery should not be performed in sub-optimally dated pregnancies[3]. In pregnancies with clear medical indications for delivery (pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, etc. ), delivery planning should be based on the best clinical estimation of gestational age[3]. Amniocentesis for fetal lung maturity should not be used routinely before planning delivery for sub-optimally dated pregnancy[3]. Even with proven fetal lung maturity, late preterm and early term infants have an increased risk of respiratory morbidity[3]. Elective delivery should be performed at 41 completed weeks, due to concerns that the fetus could be further along than estimated by third-trimester ultrasound[3]. Antepartum fetal testing can be performed after 39 weeks in patients with sub-optimal dating due to concerns for post-term pregnancy[3]. In a sub-optimally dated pregnancy, a repeat low transverse cesarean delivery, if desired by the patient, should be performed at 39 weeks based on the best estimate of gestational age[1].[6][7][8][9][7]

), delivery planning should be based on the best clinical estimation of gestational age[3]. Amniocentesis for fetal lung maturity should not be used routinely before planning delivery for sub-optimally dated pregnancy[3]. Even with proven fetal lung maturity, late preterm and early term infants have an increased risk of respiratory morbidity[3]. Elective delivery should be performed at 41 completed weeks, due to concerns that the fetus could be further along than estimated by third-trimester ultrasound[3]. Antepartum fetal testing can be performed after 39 weeks in patients with sub-optimal dating due to concerns for post-term pregnancy[3]. In a sub-optimally dated pregnancy, a repeat low transverse cesarean delivery, if desired by the patient, should be performed at 39 weeks based on the best estimate of gestational age[1].[6][7][8][9][7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Dating of pregnancy is done by the primary care provider, midwife, nurse practitioner, obstetrician and the obstetric nurse. Establishing an accurate gestational age and estimated delivery date is the most important step in the management of any pregnancy[1]. Accurate knowledge of gestational age allows laboratory and screening tests to be performed at the appropriate time in the pregnancy[1]. Optimal dating allows one to follow the pregnancy, anticipate any difficulties and predict the day of delivery. The more prepared the pregnancy team is, the better are the outcomes.[10] (level V)

Establishing an accurate gestational age and estimated delivery date is the most important step in the management of any pregnancy[1]. Accurate knowledge of gestational age allows laboratory and screening tests to be performed at the appropriate time in the pregnancy[1]. Optimal dating allows one to follow the pregnancy, anticipate any difficulties and predict the day of delivery. The more prepared the pregnancy team is, the better are the outcomes.[10] (level V)

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

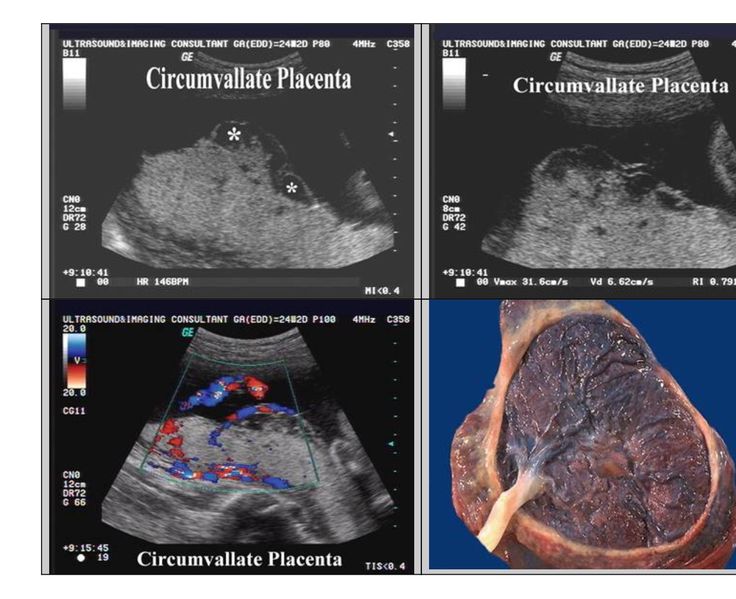

Figure

Timeline of pregnancy by weeks and months of gestational age. Contributed by Wikimedia Commons,"Medical gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014" (Public Domain)

Figure

Chart showing birth weights for gestational ages. Contributed by Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

References

- 1.

Committee Opinion No 700: Methods for Estimating the Due Date.

Obstet Gynecol. 2017 May;129(5):e150-e154. [PubMed: 28426621]

Obstet Gynecol. 2017 May;129(5):e150-e154. [PubMed: 28426621]- 2.

Reddy UM, Abuhamad AZ, Levine D, Saade GR., Fetal Imaging Workshop Invited Participants*. Fetal imaging: executive summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Radiology, Society for Pediatric Radiology, and Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Fetal Imaging workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 May;123(5):1070-1082. [PubMed: 24785860]

- 3.

Committee Opinion No. 688: Management of Suboptimally Dated Pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;129(3):e29-e32. [PubMed: 28225423]

- 4.

Hsu S, Euerle BD. Ultrasound in pregnancy. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2012 Nov;30(4):849-67. [PubMed: 23137399]

- 5.

Morse K, Williams A, Gardosi J. Fetal growth screening by fundal height measurement.

Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009 Dec;23(6):809-18. [PubMed: 19914874]

Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009 Dec;23(6):809-18. [PubMed: 19914874]- 6.

Rittenhouse KJ, Vwalika B, Keil A, Winston J, Stoner M, Price JT, Kapasa M, Mubambe M, Banda V, Muunga W, Stringer JSA. Improving preterm newborn identification in low-resource settings with machine learning. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0198919. [PMC free article: PMC6392324] [PubMed: 30811399]

- 7.

O'Gorman N, Salomon LJ. Fetal biometry to assess the size and growth of the fetus. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 May;49:3-15. [PubMed: 29605157]

- 8.

Lee AC, Panchal P, Folger L, Whelan H, Whelan R, Rosner B, Blencowe H, Lawn JE. Diagnostic Accuracy of Neonatal Assessment for Gestational Age Determination: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2017 Dec;140(6) [PubMed: 29150458]

- 9.

Wylomanski S, Winer N. [Role of ultrasound in elective abortions]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2016 Dec;45(10):1477-1489. [PubMed: 27814980]

- 10.

Santosa WB, Staines-Urias E, Tshivuila-Matala COO, Norris SA, Hemelaar J. Perinatal outcomes associated with maternal HIV and antiretroviral therapy in pregnancies with accurate gestational age in South Africa. AIDS. 2019 Aug 01;33(10):1623-1633. [PubMed: 30932959]

Routine ultrasound in late pregnancy (after 24 weeks gestation) to assess impact on infant and maternal outcomes

Cochrane Evidence Synthesis and Methods ►

the presence of complications or to identify problems that may not be detected otherwise. If such problems are identified, this could lead to changes in care and improved outcomes in infants. However, conducting the study in all women is controversial. Screening of all women may mean that interventions are on the rise, without benefit to mothers or children. Despite the study's popularity, women may not fully understand the purpose of the study, and may also have the wrong attitude about unwanted results. Available evidence suggests that routine ultrasonography after 24 weeks of gestation in low-risk or unselected women does not benefit the mother or her baby. The review included thirteen trials involving 34 980 women randomly assigned to screening or control groups (selective ultrasound, no ultrasound, or non-disclosure). The quality of the tests was satisfactory. There were no differences between groups in the number of women who had additional investigations, antenatal hospitalizations, preterm birth before 37 weeks, induction of labor, instrumental labor, or caesarean section. The weight of children and their condition at birth, as well as interventions such as resuscitation and specialized care, were similar in both groups. Survival of infants with or without congenital anomalies was similar with and without routine ultrasonography in late pregnancy. None of the trials reported on the effect of routine late pregnancy ultrasound on preterm birth before 34 weeks, maternal psychological well-being, or cognitive development of children at two years of age.

The review included thirteen trials involving 34 980 women randomly assigned to screening or control groups (selective ultrasound, no ultrasound, or non-disclosure). The quality of the tests was satisfactory. There were no differences between groups in the number of women who had additional investigations, antenatal hospitalizations, preterm birth before 37 weeks, induction of labor, instrumental labor, or caesarean section. The weight of children and their condition at birth, as well as interventions such as resuscitation and specialized care, were similar in both groups. Survival of infants with or without congenital anomalies was similar with and without routine ultrasonography in late pregnancy. None of the trials reported on the effect of routine late pregnancy ultrasound on preterm birth before 34 weeks, maternal psychological well-being, or cognitive development of children at two years of age.

Ultrasound protocols differed across all trials, as did the reasons for performing the examination after 24 weeks of gestation. The influence of ultrasound in the first and second trimesters is difficult to exclude, and the assessment of most indicators in late pregnancy is based on control data, which depends on the exact dating of early pregnancy. The trials were carried out during the introduction of the method into wide clinical practice, during which approaches to assessing fetal size and normal ultrasound signs were still being discussed. As ultrasound technology continues to evolve and become more accessible, it is important to be clear about its significance. Ultrasonography can be used to detect abnormality without any impact on the ability to fully evaluate clinical outcomes. The feeling of anxiety that arises in a pregnant woman about the health of her child can have serious long-term consequences. Beyond this, little is known about how the exposed child develops after birth and during the first years of life.

The influence of ultrasound in the first and second trimesters is difficult to exclude, and the assessment of most indicators in late pregnancy is based on control data, which depends on the exact dating of early pregnancy. The trials were carried out during the introduction of the method into wide clinical practice, during which approaches to assessing fetal size and normal ultrasound signs were still being discussed. As ultrasound technology continues to evolve and become more accessible, it is important to be clear about its significance. Ultrasonography can be used to detect abnormality without any impact on the ability to fully evaluate clinical outcomes. The feeling of anxiety that arises in a pregnant woman about the health of her child can have serious long-term consequences. Beyond this, little is known about how the exposed child develops after birth and during the first years of life.

Translation notes:

Translation: Khaidarova Chulpan Mustakimovna. Editing: Kukushkin Mikhail Evgenievich. Project coordination for translation into Russian: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia (branch of the Northern Cochrane Center on the basis of Kazan Federal University). For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]; [email protected]

Project coordination for translation into Russian: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia (branch of the Northern Cochrane Center on the basis of Kazan Federal University). For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]; [email protected]

Case Solved! New technology allows fingerprints to be dated » DailyTechInfo

Worldwide crime may be tightened up thanks to the work of a group of Dutch forensic experts who have discovered a way to date fingerprints fairly accurately. This achievement will provide police officers with the opportunity to successfully investigate even unsolved crimes that were committed several years ago.

"The police are constantly asking about the possibility of fingerprint dating," says Marcel de Puy of the Dutch Forensic Institute (NFI), "If, for example, a neighbor's fingerprints are found at a crime scene, we can now be sure to tell when they were left, on the night of the crime or the day before when the neighbor came in for a cup of coffee. "

"

Let us remind our readers that fingerprints are unique marks left by a person on any objects that he touched with his bare hands. These prints can be copied in various ways and compared with print designs stored in a specialized database. It should be noted that this technology has been used by the police to identify criminals and suspects since the early 1900s.

The actual prints consist of a complex mixture of fatty secretions and sweat, which includes certain types of amino acids, proteins and cholesterol as well. "The chemical composition of the print material can be analyzed thanks to the development of new technologies to do this," says de Puy, "Some components decompose and disappear over time, some do it quickly, others slowly. By determining the relative proportions of some chemical compounds, we get the ability to say with a fairly high accuracy the date, and in some cases the time, when this imprint was left.

"In the past, some forensic scientists have attempted to calculate the timing of fingerprints. Unfortunately, they failed because they focused on quantifying certain chemical compounds. We took the relative proportions of the compounds as a basis and achieved the desired result," explains de Puy.

Unfortunately, they failed because they focused on quantifying certain chemical compounds. We took the relative proportions of the compounds as a basis and achieved the desired result," explains de Puy.

At present, the chemical analysis procedure developed by the de Puy group makes it possible to date prints within several time intervals, giving different dating accuracy. The most accurate results, including time, are given by the analysis of prints left one to two days ago. The analysis of prints up to two weeks ago gives less accuracy, and the date of prints left even later can only be judged approximately.

The new technology has already begun to be tested in real crime scenes. In parallel, an accompanying database is being created, the data from which will be used to improve chemical analysis methods. These procedures will take about a year, after which the technology of dating prints can go into the category of indisputable evidence accepted by the courts of various countries.