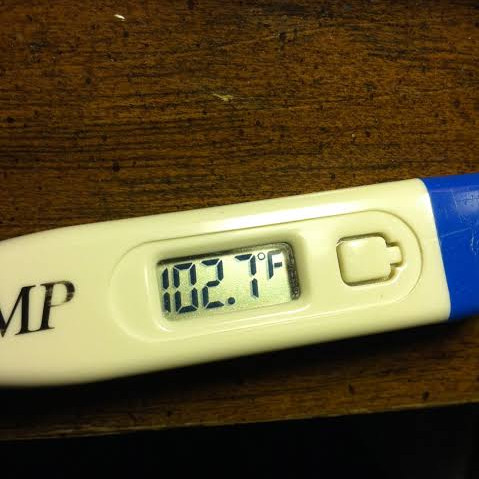

Baby 100.6 fever

What should I do if my baby has a fever?

Something’s not right with your little one. While usually a good eater, your baby won’t take a bottle or breastfeed. They have no interest in their favorite toy even when you make it dance before their eyes. And when you reach out to console them, their skin is hot to the touch. Is it a fever?

As a parent, you know when your baby isn’t acting normal. And if you think your baby has a fever, it’s understandable to be a little nervous. You’d rather feel sick yourself than have your little one be under the weather.

Try not to worry. Every baby will likely have a fever at some point in their young lives, and most fevers are mild and can be treated at home.

Still, it’s important to know the signs of fever in babies, how to take their temperature, what’s considered a fever, and when to call your baby’s doctor or seek immediate care for fever symptoms.

Common signs of a fever in babies

So, what are signs that baby may have a fever? These are some of the first cues:

- Baby’s forehead or neck feels warm when you use the back of your hand to check (their body temperature should be about the same as yours).

- If your child is acting normal, but their temperature is elevated, don’t worry just yet. Sometimes little ones can run quick fevers but not be sick. So, monitor them for any symptoms listed below.

- Baby doesn’t look like themselves. Maybe they’re shivering, sweating or have flushed red cheeks.

- Baby is acting differently. For example, they may:

- Seem weaker or sleepier than usual

- Be extra fussy

- Have a decreased appetite or poor eating

- Show no interest in playing

- Have trouble sleeping

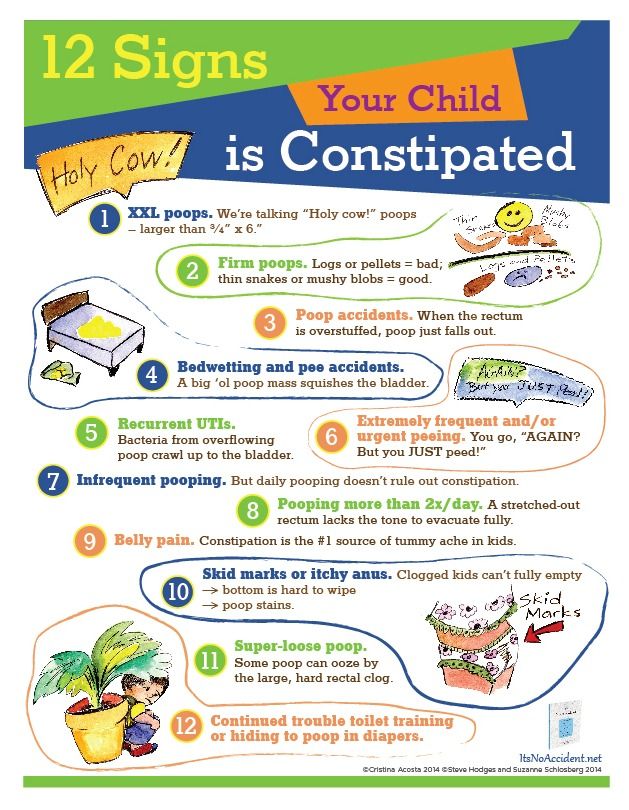

- Baby isn’t peeing like normal. When you change their diaper, you notice changes in urine color, odor or amount.

- Baby is vomiting.

Causes of fever in babies

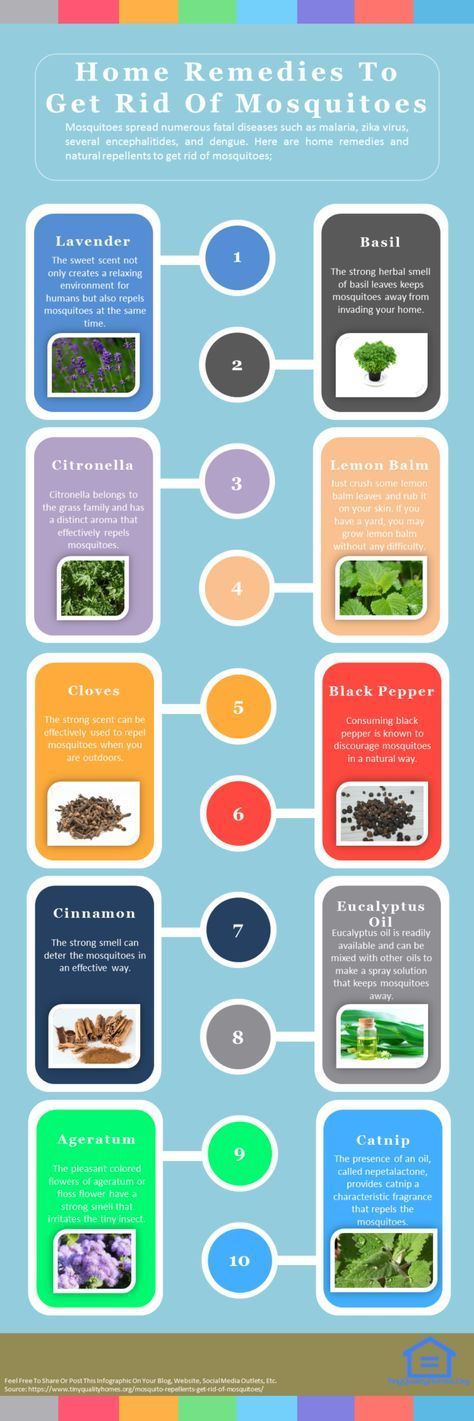

A fever is not an illness and is often, but not always, a sign that baby’s immune system is fighting something. Here are some of the most common reasons for fevers:

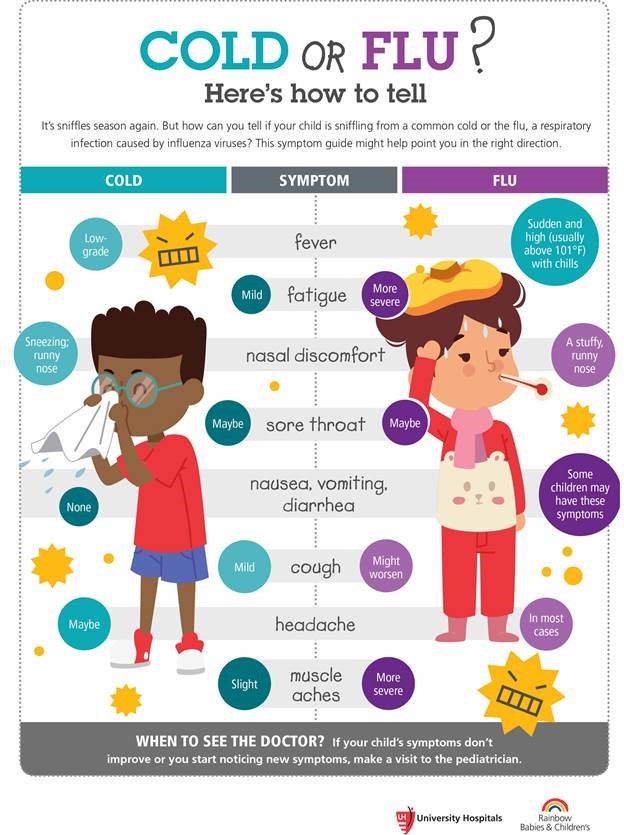

- A cold or flu

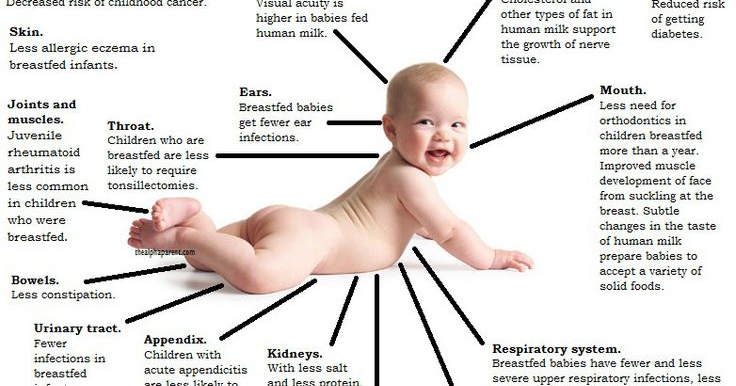

- Ear infection

- Urinary infection

- Pneumonia

- Bacterial infection caused by a severe diaper rash

- A mild side effect of recent vaccinations

- They’re overheated

How to take your baby’s temperature

If your baby is showing any signs of a fever, take their temperature. The best way to do this – and the thermometer to use – depends on your baby’s age.

The best way to do this – and the thermometer to use – depends on your baby’s age.

Finding the right thermometer

The best temperature readings come from direct contact with your baby. So, for the first six months of their life, you should always use a digital thermometer.

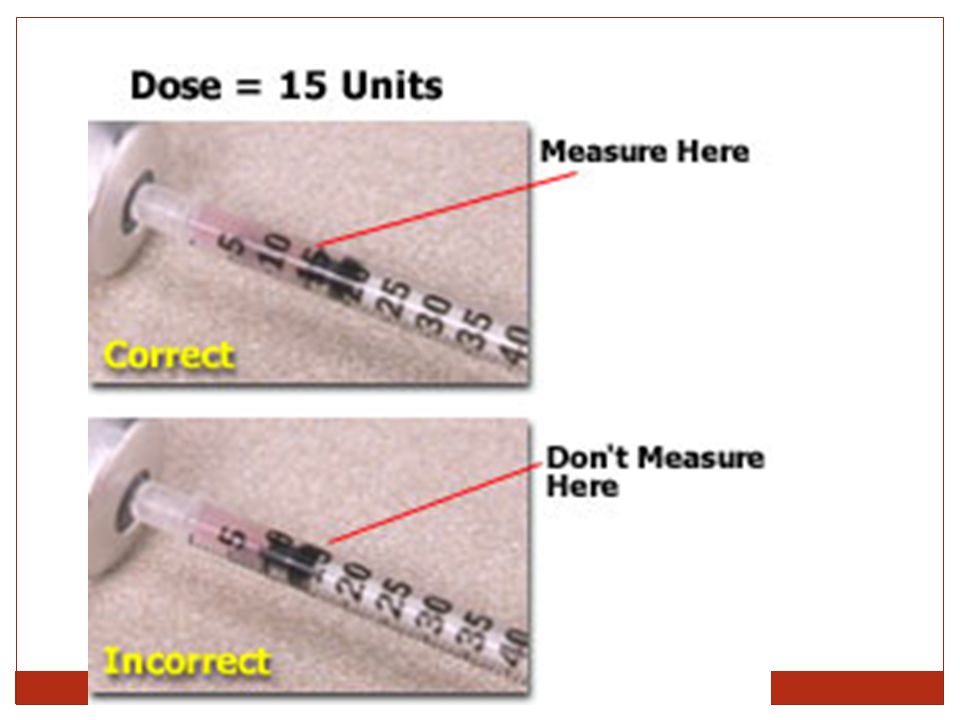

You’ve probably used a digital thermometer to take your own temperature by placing it under your tongue. But you’ll take your baby’s temperature by placing the thermometer in either their armpit or rectum.

So, look for one that is labeled for rectal use. You may also find an all-in-one thermometer that can be used orally, rectally or in their armpit. If you opt for an all-in-one thermometer for rectal use, make sure to label it. The same thermometer should never be used for both rectal and oral temperatures.

Once your baby is over 6 months old, you can use remote thermometers for the forehead and ear canal to take their temperature. Thermometers not recommended for any age baby include plastic strip thermometers, pacifier thermometers and smartphone temperature apps.

How to take your baby’s temperature rectally

A rectal temp is considered the gold standard for accurately knowing an infant’s temperature until they’re over 6 months old. Here’s how to get an accurate reading:

Using a digital thermometer to measure rectal temperature

- Clean the digital thermometer by washing it with soap and water, or wiping with rubbing alcohol.

- Lay your baby down either on their back or belly with legs bent toward their chest.

- Apply petroleum jelly to the metal tip of the thermometer and gently glide it into the rectal opening – usually about half an inch, but follow your specific thermometer’s instructions carefully.

- Turn on the thermometer.

- Hold the thermometer in place until it beeps – usually about two minutes.

- Slide out the thermometer.

- Make note of the temperature.

- Clean the thermometer before storing.

If you’re uncomfortable taking your baby’s temperature rectally, you can call a nurse line and ask to be walked through the process over the phone (both your clinic and health plan likely offer this kind of service).

How to take your baby’s temperature under their arm

Taking your baby’s temperature under their arm is very simple. Just know that this type of reading is less accurate, and can be affected by the amount of clothing your baby is wearing and the temperature in the room.

Using a digital thermometer to measure armpit temperature

- Remove baby’s clothes so their chest is bare.

- Place the digital thermometer in one of their armpits.

- Fold their arm over the thermometer.

- Turn on the thermometer.

- Hold their arm in place until the thermometer beeps, which usually happens in less than two minutes.

- Remove the thermometer.

- Make note of the temperature, adding one degree to the reading.

How to take your baby’s temperature with a remote forehead thermometer

If your baby is older than 6 months, a temporal artery thermometer (TAT) can be an easy way to measure your baby’s forehead temperature from a distance.

A TAT uses infrared light to read the temperature of the temporal artery, which is located in your baby’s forehead.

The benefit of a TAT is that it can quickly record a temperature, and your little one won’t need to hold still for a whole minute or two. But readings can be less accurate than digital thermometers.

Using a temporal artery thermometer

- Make sure baby’s forehead is clean and dry.

- Hold thermometer in front of the baby’s forehead at the correct distance. (This distance is different for every thermometer, so make sure to follow the directions for your specific model.)

- Hold down the button and wait for the thermometer to beep. This shouldn’t take more than a couple seconds.

- Make note of the temperature.

How to take baby’s temperature with a remote in-ear thermometer

Another option for babies 6 months and older is an in-ear thermometer. Also called a tympanic thermometer, this type of thermometer measures the temperature of the ear drum using infrared light.

A tympanic thermometer is similar to a TAT but has a small cone-shaped probe to use in the ear canal. Some TATs have probe attachments that allow them to be used in-ear.

Using a tympanic thermometer

- Check the inside of baby’s ear to make sure it’s clean.

- Clean the tip of the probe with rubbing alcohol.

- Gently tug your baby’s ear straight back to make room for the probe.

- Gently ease the probe into the ear canal.

- Press the button and hold thermometer in place until it flashes or beeps. This is usually just a second or two.

- Remove thermometer.

- Take note of the temperature.

If used correctly, in-ear thermometers can provide reliable temperature readings in older babies. But they aren’t as accurate if your baby has earwax buildup or a small, curved ear canal.

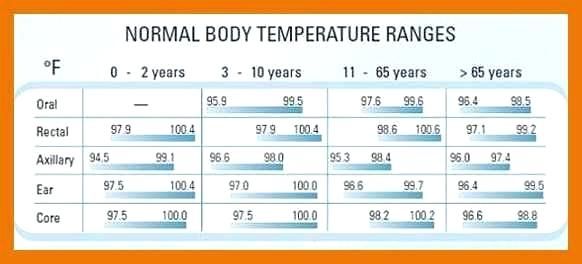

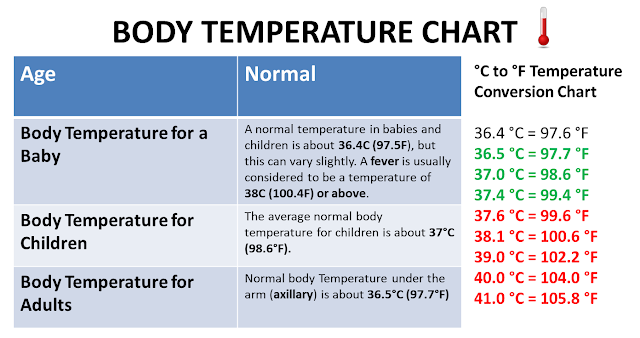

What is a normal temperature for a baby?

Some changes in your baby’s temperature are completely normal. A baby’s temperature naturally goes up throughout the day or when lying in a warm blanket. Likewise, their temperature may go down on colder days or after spending time in the bath.

Likewise, their temperature may go down on colder days or after spending time in the bath.

Generally, a normal temperature for a baby is between 97 degrees and 100.3 degrees Fahrenheit. If something’s off with your baby’s internal systems, you’ll typically see bigger spikes or drops in temperatures that don’t go away on their own, and the baby will start to act sick.

Baby temperature chart

| Baby’s temperature | What does it mean? |

|---|---|

| Lower than 95 degrees Fahrenheit | Baby’s temperature is too low |

| 97 – 100.3 degrees Fahrenheit | Baby’s temperature is within normal range |

| 100.4 – 103.9 degrees Fahrenheit | Baby has a fever |

| Greater than 104 degrees Fahrenheit | Baby has a high fever |

Low-grade fevers or mild fevers in babies are often described by several different ranges. Some people may consider anything between 98.6 degrees and 100.3 degrees a mild fever. Others may think temperatures between 99.5 degrees and 102.2 degrees indicate a mild fever.

Some people may consider anything between 98.6 degrees and 100.3 degrees a mild fever. Others may think temperatures between 99.5 degrees and 102.2 degrees indicate a mild fever.

Among most doctors, a mild or low-grade fever in babies is between 100 and 102 degrees. But, unless your baby’s behavior has changed or there are other concerning symptoms, no treatment may be necessary.

Baby fever treatment based on age

If baby has a fever, does that mean you should immediately call your baby’s doctor? Not necessarily. A lot depends on your baby’s age and the type of fever they have. Here’s a quick rundown of treatment, depending on your baby’s age.

If your baby is less than 3 months old

What’s considered a fever in a newborn? While a fever is a fever, regardless of age, doctors want to see younger babies with fevers sooner. That’s because young babies can get very sick, very quickly and it’s important to identify the cause and start treatment as soon as possible.

So, call your baby’s doctor or nurse line if their temperature is 100.4 degrees or higher. If your baby is less than two months old, the doctor will want to see baby as soon as possible. Also, anytime your baby is acting ill – whether a fever is present or not – call in.

You can help your baby feel comfortable at home by keeping them in lightweight clothing and not over-bundling with blankets. Also, try to increase the frequency of breastfeeding or bottle feeding to prevent dehydration.

Watch out for low body temp in infants

What should you do if your baby’s temperature is low? If your baby is cold, warm them up! Cuddling under a warm blanket or an extra layer of clothing are good choices to warm up your baby. But you should call your doctor if their temperature drops below 97 degrees.

Small babies are less able to regulate their body temperature. In other words, sometimes when babies get cold, they stay cold or get even colder.

If a baby’s temp stays low for a long period of time, it can affect their metabolism and breathing, as well as increase their overall risk of serious complications. So if your baby is cold to the touch, or has blue lips or fingers, take their temperature. If it’s low, give your baby’s doctor a call.

So if your baby is cold to the touch, or has blue lips or fingers, take their temperature. If it’s low, give your baby’s doctor a call.

If your baby is 3–6 months

If your baby has a mild fever, but they’re acting normal, you may not need to see the doctor. Usually the best course of action is keeping baby comfortable, dressing them in light clothing and making sure they are getting enough to drink.

But if your baby’s temperature is above 102 degrees, definitely call. When you talk to the nurse line or doctor, they will want to know if your baby is not eating or sleeping well, or if they seem less comfortable than normal. Using this information, the nurse or doctor will provide a recommendation on what to do next, which may include giving your child a dose of Tylenol to help with comfort.

A mild fever can actually be a good thing because it shows that baby’s immune system is working the way it should. Making sure that baby is getting enough liquids will help keep them comfortable – and hydrated – so continue with frequent feedings.

And as a heads up, you’ll probably start to see more crying, crankiness and mild fevers when your baby starts teething, which usually happens at around 6 months. Teething time can be a challenge, so try out different ways to make your baby more comfortable and teething easier, including a solid teething ring, a wet washcloth or a refrigerated pacifier.

If your baby is 6–24 months

If your baby is drinking plenty of fluids, still sleeping well and continuing to play, there may be no need to treat a mild fever. You probably will only need to come in if your little one has a temp of 102 degrees or higher that lasts longer than a day. Give the nurse line a call if you’d like help determining if you should schedule an appointment. They can also recommend which medicines to use and how much, if necessary.

When to call your baby’s doctor or seek care for a fever

Here are some guidelines for when to seek care based on your baby’s age and temperature. But if you’re concerned about your baby and their temperature is normal, call anyway. The pediatric team at HealthPartners is always here for you and your little one.

The pediatric team at HealthPartners is always here for you and your little one.

Call your baby’s doctor or nurse line within 24 hours if:

- Your baby is 2 to 3 months old and has a temperature of 100.4 degrees or higher, or a temperature lower than 97 degrees.

- Your baby is 3 to 6 months old and has a temperature of 102 degrees or higher.

- Your baby is 6 to 24 months old and has a temperature of 102 degrees or higher that lasts longer than a day.

Call your baby’s doctor or go to urgent care or the emergency room right away if:

- Baby is under 2 months old and has a fever.

- Baby is unvaccinated and has a fever.

- Baby is nonstop crying or cries when touched or moved.

- Baby is having difficulty breathing.

- Baby is struggling to swallow fluids.

- Baby is shaking or has chills that last more than 30 minutes.

- Baby keeps vomiting.

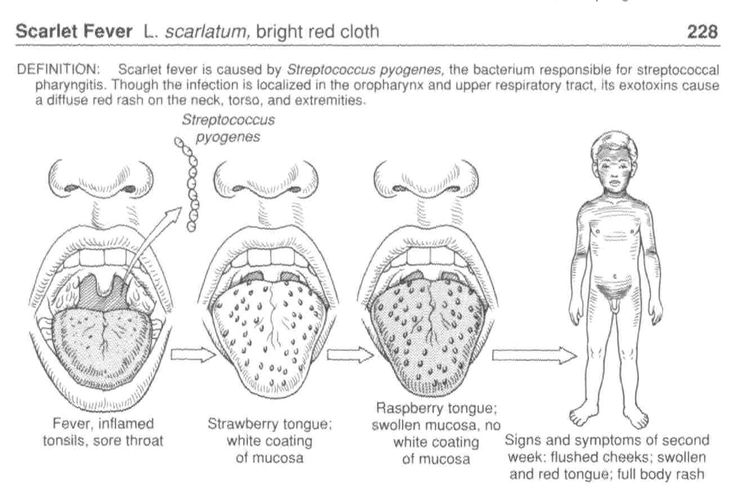

- Baby has an unusual skin rash that worsens.

- Baby stops peeing.

Call 911 for immediate emergency care if:

- Baby isn’t moving.

- Baby can’t wake up.

- Baby has severe trouble breathing such as struggling for breath or can barely cry or speak.

- Baby has purple or blood-colored spots or dots on their skin.

Nervous about your baby’s fever? We can help.

If you’re not sure if you should be concerned about your baby’s temperature, call us. We’re here to help.

HealthPartners members and patients can call 800-551-0859. Park Nicollet patients can call their clinic directly during regular business hours, or 952-993-4665 if it’s after hours. For questions and advice on new baby care, you can also call our 24/7 BabyLine at 612-333-2229.

When Your Newborn Has a Fever

As adults, we have a tightly controlled thermostat to help regulate our body temperature. When we’re cold, we shiver to help raise our temperature, and when we’re too hot, we sweat to help cool ourselves down. These mechanisms, on the other hand, are not completely developed in newborns. What’s more, newborns lack the insulating fat layer that older babies and children develop.

These mechanisms, on the other hand, are not completely developed in newborns. What’s more, newborns lack the insulating fat layer that older babies and children develop.

Because a newborn's temperature regulation system is immature, fever may or may not occur with infection or illness. However, fever in babies can be due to other causes that may be even more serious. Call your baby's doctor immediately if your baby younger than 2 months old has a rectal temperature of 100.4 degrees or higher. This requires an urgent evaluation by your doctor

In older infants and young children, a fever is any rectal temperature of 101 degrees or higher. Call the doctor if your 3-6 month old has a temperature of 101 or greater. With babies and children older than 6 months, you may need to call if the temperature is greater than 103, but more than likely, associated symptoms will prompt a call. A rectal temperature between 99 and 100 degrees is a low-grade fever, and usually does not need a doctor's care.

Fever in newborns may be due to:

-

InfectionFever is a normal response to infection in adults, but only about half of newborns with an infection have a fever. Some, especially premature babies, may have a lowered body temperature with infection or other signs such as a change in behavior, feeding, or color.

-

OverheatingWhile it’s important to keep your baby from becoming chilled, your baby can also become overheated with many layers of clothing and blankets. This can occur at home, near heaters, or near heat vents. It can also occur if your baby is over-bundled in a heated car. Never leave your baby alone in a closed car, even for a minute. The temperature can rise quickly and cause heat stroke and death.If your baby is overheated, he or she may have a hot, red, or flushed face, and may be restless. To prevent overheating, keep rooms at a normal temperature, about 72 to 75 degrees, and dress your baby the same way you feel comfortable at that temperature.

-

Low fluid intake or dehydrationSome babies may not take in enough fluids, which causes a rise in body temperature. This may happen around the second or third day after birth. If fluids are not replaced with increased feedings, dehydration (excessive loss of body water) can develop and cause serious complications. Intravenous (IV) fluids may be needed to treat dehydration.

In extremely rare cases, fever can signal a life-threatening disease called bacterial meningitis. If your infant has a fever greater than 101 degrees and is lethargic or you can't get him or her to wake up normally, you should take your infant to the emergency room immediately.

Taking Baby’s Temperature

For babies and toddlers up to 3 years old, taking the temperature rectally, by placing a thermometer in the baby’s anus, is best. This method is accurate and will give a quick reading of your baby's internal temperature.

Underarm temperature measurements may be used for babies ages 3 months and older. Other types of thermometers, such as ear thermometers, may not be accurate for newborns and require careful positioning to get a precise reading. Skin strips that are pressed on the skin to measure temperature are not recommended for babies. Touching your baby's skin can let you know if he or she is warm or cool, but you cannot measure body temperature simply by touch.

Oral and rectal thermometers have different shapes and one should not be substituted for the other. Do not use oral thermometers rectally as these can cause injury. Rectal thermometers have a security bulb designed specifically for safely taking rectal temperatures. To take your infant’s rectal temperature, follow these steps:

-

Place your baby across your lap or changing table, on his or her stomach, facing down. Place your hand nearest your baby's head on his or her lower back and separate your baby's buttocks with your thumb and forefinger.

-

Using your other hand, gently insert the lubricated bulb end of the thermometer one-half inch to one inch, or just past the anal sphincter muscle. Stop immediately if the thermometer meets resistance.

-

The thermometer should be pointed toward your baby’s navel.

-

Hold the thermometer with one hand on your baby's buttocks so the thermometer will move with your baby. Use the other hand to comfort your baby and prevent moving.

-

Never leave your baby unattended with a rectal thermometer inserted. Movement or a change in position can cause the thermometer to break.

-

Hold the thermometer for at least 1 minute or until an electronic thermometer beeps or signals.

-

Remove the thermometer.

-

Wipe the bulb.

-

Read the thermometer immediately and write down the temperature, date, and time of day.

-

Disinfect the thermometer with rubbing alcohol or an antiseptic solution.

If your baby's temperature is 100.4 degrees or higher, make sure he or she is not crying or dressed too warmly. Retake your baby's temperature again in about 30 minutes. If the temperature is still high, call your baby's doctor immediately.

How to Treat a Fever

If your baby’s temperature doesn’t warrant a call to the doctor, there are steps you can take at home to help lower the fever:

-

Bathe your baby in lukewarm water. Never use cold water or alcohol to bathe your baby because it may cause shivering and actually increase body temperature.

-

Dress your baby in light, comfortable clothing.

-

Make sure your baby is getting enough fluids to prevent dehydration.

-

NEVER give your baby aspirin to treat a fever.

Aspirin has been linked to Reye's syndrome, a rare but potentially serious illness that affects the nervous system and can be debilitating or even fatal in children.

Aspirin has been linked to Reye's syndrome, a rare but potentially serious illness that affects the nervous system and can be debilitating or even fatal in children. -

Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are the two medications for children that help fight fever. Acetaminophen can be given to infants over 3 months without calling the doctor but children less than 6 months old should not be given ibuprofen. Read the instructions on the package or ask your doctor to be sure you give appropriate doses. Do not give more than the recommended dose of either medication. If your child is vomiting or dehydrated be sure to consult your pediatrician.

High temperature in a child can cause febrile convulsions

09/12/2022 09/12/2022 health

First of all, it is important to know that fever is a sign of the immune system. Against the background of a temperature of 38-39 degrees, more favorable conditions are created for the production of their own protective antiviral interferons.

High fever in infants up to 3 months

If the temperature rises in infants up to 3 months, you should immediately call an ambulance. If the child is older, you can more calmly observe his condition and act according to the situation.

In infants, the body temperature is normal, as usual, up to 37, but during physiological stress it can rise to 37.5, and this is also the norm. An increase above 38 requires observation. Physiological temperature rises up to 37.5 can occur in a baby after eating, defecation, crying, screaming, sleeping, due to too hot clothes. So the temperature needs to be measured outside of these situations. The child needs to be unwound, ventilated for five minutes and only then measure the temperature.

How to control the temperature?

- Provide a cool room temperature and 50-60% humidity.

- Give the child plenty to drink: at elevated temperatures, fluid is lost excessively through sweating and breathing.

- It is useful to bathe a child, as water procedures have an antipyretic effect.

The water should be warm: two degrees lower than the body temperature, for example, if the child has a temperature of 39, then the water should be 37 degrees. You can take a shower or bath as many times as you like at any body temperature, the child can be in the water as long as he wants, then he needs to be allowed to dry himself in a cool, ventilated room. It is at the moment of evaporation of liquid from the surface of the body that the main decrease in temperature occurs. This kind of physical cooling reduces the need for antipyretic drugs.

The water should be warm: two degrees lower than the body temperature, for example, if the child has a temperature of 39, then the water should be 37 degrees. You can take a shower or bath as many times as you like at any body temperature, the child can be in the water as long as he wants, then he needs to be allowed to dry himself in a cool, ventilated room. It is at the moment of evaporation of liquid from the surface of the body that the main decrease in temperature occurs. This kind of physical cooling reduces the need for antipyretic drugs.

When should the temperature be reduced with drugs?

Children of the first year of life: from about 38.5 degrees

Children from one year and older: 39-39.5

The main guideline is the child's well-being. If the child does not tolerate temperature well and does not feel well, then it is possible to give an antipyretic at lower temperatures. With good tolerance, it is advisable not to bring down the temperature below the numbers indicated above. The main thing is to give the child more water, maintain the microclimate and observe.

The main thing is to give the child more water, maintain the microclimate and observe.

Safe and effective antipyretics

Two drugs are considered safe: Ibuprofen and Paracetamol (active ingredients are indicated). The dosage is selected by weight.

Ibuprofen : 10 milligrams per kilogram of body weight, i.e. if a child weighs 10 kg, he should be given 100 milligrams of ibuprofen. If there are 100 milligrams in 5 milliliters of ibuprofen syrup, 5 milliliters should be given. Can be given every 8 hours (at least 6), i.e. 3 times a day (maximum 4)

Paracetamol : 15 milligrams per kilogram of weight, that is, if the child weighs 10 kilograms, then we give 150 milligrams of paracetamol. If the syrup has 120 milligrams in 5 milliliters, then you need to give about 6 milliliters. Can be given every 6 hours: 4 times a day.

It is advisable to limit yourself to taking one of the drugs. Only in the most extreme cases, when the child is ill with a rapidly rising and difficult temperature, for example, with roseola, can the drugs be alternated every 4 hours.

The drug should work within one and a half hours. A success is considered to be a decrease in temperature by at least a degree. It is not necessary to bring down the temperature to normal. To enhance the effect during these one and a half hours, you can do water procedures.

Fever without additional symptoms and urinalysis

In the first days of illness, if there is a fever but no other symptoms, it is better to take the child to the doctor and take a urinalysis so as not to miss a urinary tract infection. If the urinalysis indicators are good, the child is examined, urinary tract infection and signs of a complicated course of a viral disease are excluded, you can safely observe. With many infections, it sometimes happens that catarrhal symptoms: runny nose, sore throat, cough, do not appear from the first day of the disease.

What not to do?

Do not run to take a blood test during the first two days of fever. Changes in the blood take time, so the test results can only be misleading.

Profebrile convulsions

Febrile seizures occur in 1 in 20 children when the temperature rises to 38-39 degrees in children from 6 months (sometimes earlier) to 5-6 years: more often between the ages of 12 and 24 months. Such convulsions are usually short (1-2 minutes) and end on their own. After the “exit” from convulsions, the child may be lethargic, drowsy, disoriented, and experience a headache.

Despite the frightening picture, febrile convulsions do not harm the child, do not impair the intelligence and development of the baby. Their appearance is not equal to epilepsy, although the risk of developing this disease in this case is slightly higher.

Seizures may occur due to severe fever during infection or after vaccination. They appear in the first hours of the disease and may be its first symptom. May recur, most often in the first year after the attack. The chance is higher if the parents have had seizures.

Seizure treatment and prevention

If the attack ended on its own, no special treatment is required. An anticonvulsant medication may be needed to treat a prolonged seizure. Preventive therapy is not needed. Previously, it was believed that if convulsions occurred at least once, it is necessary to bring down the temperature already from 37.5. Today, this postulate has been refuted: lowering the temperature cannot prevent convulsions in a child prone to them.

What to do if an attack has already developed?

- Don't panic

- Place the child on a hard surface with the head turned to the side

- Uncover the child and fan it so that the fever subsides

- Be close, make sure that the child is not injured

- Try to film the attack on video, fix or remember everything that happens: the child's posture, the position of the limbs, facial expressions, eye movement, consciousness, the duration of the attack

- Call ambulance

Never

- Do not put a spoon or other object into the mouth to hold the tongue: the tongue does not sink during convulsions

- Do not give Ibuprofen/Paracetamol or other drugs at the time of an attack

- Do not restrain a child by force

After an attack

Urgently see a doctor - preferably in the emergency department of a children's hospital - to identify the causes of fever and exclude a serious infection: meningitis, encephalitis.

In any case, a child with a fever should be seen by a doctor. Timely examination will help to exclude dangerous conditions and bring the disease under control.

The article was prepared jointly with the head of the pediatric department of Lahta Junior Tatyana Maksimova

Fever in children. Causes of development and methods of treatment

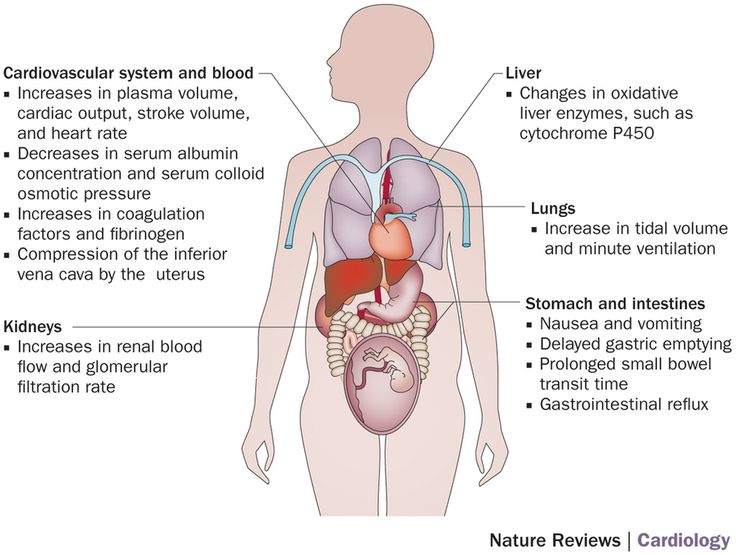

Body temperature is regulated by thermosensitive neurons localized in the preoptic and anterior hypothalamus. These neurons are responsible for changes in body temperature in the same way as neural connections with cold and heat receptors located in the skin and muscles. Thermoregulatory responses are highly variable, mediated through a variety of mechanisms, and include directing blood flow in the skin vasculature, increased or decreased sweat secretion, regulation of extracellular fluid volume (via arginine vasopressin), or behavioral responses such as seeking warmth or cool ambient temperature. Normally, there is a circadian temperature rhythm or diurnal variations in body temperature within adjustable limits. Body temperature is lower in the morning and approximately 1°C higher in the afternoon and late afternoon.

Fever is a controlled increase in body temperature through mechanisms that regulate normal temperature. The difference is that the "thermostat" of the body is reset to a high temperature. Depending on which disease accompanies fever (infectious, connective tissue disease, malignant process), regulatory mechanisms are triggered in response to endogenous pyrogens, which, in turn, trigger the production of cytokines such as interleukin (IL) 1β and IL-6 , tumor necrotizing factor α, β-interferons and interferon-γ. Stimulated leukocytes and other cells produce lipids that also serve as endogenous pyrogens. The most well-studied lipid mediator is prostaglandin E2. Most endogenous pyrogenic molecules are too large to cross the blood-brain barrier. However, near the hypothalamus, the functions of the blood-brain barrier are insufficient, which allows neurons to contact circulating factors through a network of capillaries.

Microbes, microbial toxins and other microbial waste products are among the most common exogenous pyrogens that, when ingested, stimulate the functions of macrophages and other cells to produce endogenous pyrogens leading to fever. Endotoxin can directly influence thermoregulation in the hypothalamus and stimulate the release of endogenous pyrogens. Some substances formed in the body are not pyrogens, but are able to stimulate the formation of endogenous pyrogens. Such substances include antigen-antibody complexes in the presence of complement, as well as complement components, lymphocyte products, bile acids, and androgenic steroid metabolites. Fever can be the result of infections, vaccination, exposure to biological agents (granulocyte - macrophage - colony stimulating factor, interferons, interleukins), tissue damage (heart attack, pulmonary embolism, trauma, intramuscular injections, burns), malignant diseases (leukemia, lymphoma, metastatic diseases) , taking certain drugs (drug fever, cocaine, amphotericin B), diffuse connective tissue diseases, rheumatic diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis), granulomatous diseases (sarcoidosis), endocrine (thyrotoxicosis, pheochromocytoma), metabolic disorders (uremia, gout) , genetic disorders (familial Mediterranean fever) and other unknown and poorly understood causes.

An increase in body temperature in response to microbial attack represents a response that has been observed in reptiles, fish, birds, and mammals. In humans, an increase in body temperature is accompanied by a decrease in the reproduction of microorganisms and an increase in the inflammatory response. Most of the evidence to date suggests that fever is an adaptive response and should only be treated in selected situations.

Although the nature of the temperature curve alone is not often helpful in making a specific diagnosis, observation of fever can provide useful information to the clinician. In general, a single isolated peak is not associated with an infectious disease. Such a peak can be observed with parenteral administration of blood products, drugs, certain procedures or catheter manipulations with an infected skin surface. Temperatures above 41°C are rarely due to an infectious cause. Very high fever (> 41°C) is most commonly central fever (due to CNS dysfunction involving the hypothalamus), malignant hyperthermia, drug fever, fever due to overheating.

Temperature below normal (< 36 °C) is most often associated with exposure to cold, hypothyroidism, antipyretic overdose.

Intermittent or intermittent fever (daily fluctuations in t° max and t° min of at least 1 ° C, but the minimum body temperature never drops to normal values) is defined as hectic or may be due to sepsis. The remaining persistent fever is persistent, and fluctuations in t ° do not exceed 0.5 ° C per day. With relapsing (laxative) fever, fluctuations in t ° exceed 0.5 ° C during the day, but it does not return to normal. Recurrent (relapsing) fever is separated by intervals of normal temperature, for example, in three-day malaria, fever is observed on the 1st and 3rd days ( Plasmodium vivax ), four days - on the 1st and 4th days ( Plasmodium malariae ). The biphasic nature of Bactrian camel fever indicates the presence of a single disease with two definite periods of fever of more than 1 week. The classic example is polio. Biphasic fever is also observed in leptospirosis, dengue fever, yellow fever, African hemorrhagic fever.

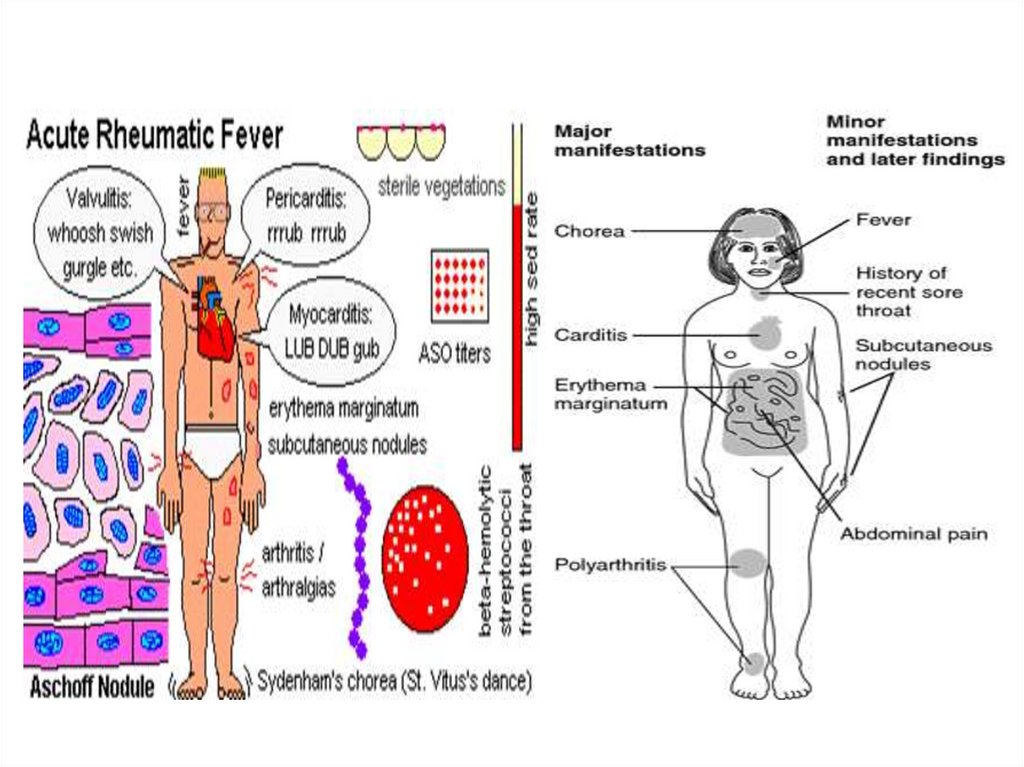

The dependence of heart rate on body temperature can be quite informative. Relative tachycardia, when the pulse rises in proportion to body temperature, is usually observed in non-communicable diseases or infections in which the toxin determines the clinical manifestations. Relative bradycardia (dissociation of pulse and temperature), when the pulse remains low during fever, suggests drug fever, typhoid, brucellosis, leptospirosis. Febrile bradycardia may also be the result of conduction disturbances involving the heart in acute rheumatic fever, Lyme disease, viral myocarditis, and infective endocarditis.

Most infections lead to various lesions causing an inflammatory response and subsequent release of endogenous pyrogens. The appointment of etiotropic antimicrobial therapy can lead to rapid elimination of bacteria. However, if tissue damage is severe, the inflammatory response and fever may continue for several days after eradication of all microbes.

Fever occurs in various infectious diseases with a wide range of severity. In healthy children, benign febrile illnesses include viral infections (rhinitis, pharyngitis, pneumonia), bacterial infections (otitis media, pharyngitis, impetigo), which usually respond well to antibiotic therapy and are not life-threatening. Risk groups include young children, with chronic diseases, immunodeficiency states. Some bacterial infections such as sepsis, meningitis, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, if left untreated, can be severe and have poor outcomes.

Fever without a specific focus usually presents a diagnostic dilemma for pediatricians, especially in children of the first 1.5–2 years of life, making it difficult to differentiate between serious bacterial infections and viral diseases.

Fever in children under 3 months of age always suggests the presence of a serious bacterial disease (sepsis, meningitis, urinary tract infection, gastroenteritis, osteomyelitis, otitis, omphalitis, mastitis, etc. ). Bacteremia may be due to group B streptococcus,

Regardless of age, a fever accompanied by a petechial rash indicates a high risk of life-threatening bacterial infections. 8-10% of patients with fever and petechiae had severe bacterial infections, 7-10% had meningococcal sepsis or meningitis. The disease caused by H.influenzae type B may also present with fever and petechial rash. Treatment tactics include hospitalization, blood and cerebrospinal fluid culture, and the appointment of appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

Many physicians use the term "fever of unknown origin" for patients presenting for examination who do not have an obvious infection or a non-infectious diagnosis. In most of these children, the appearance of additional symptoms after a relatively short period of time makes the infectious nature of the disease obvious. Therefore, this term is more often used in patients with fever that is not identifiable after 3 weeks in the outpatient setting or after 1 week in the hospital.

The causes of the so-called fever of unknown origin can be infectious processes and diseases of the connective tissue (autoimmune and rheumatic). It is necessary to exclude a neoplastic process. Most cases of fever of unknown or unrecognized origin are the result of an atypical course of common diseases. Since at the beginning there may be no clinical and laboratory signs of a certain disease, the diagnosis in some cases is made only after prolonged observation. Causes of fever of unknown origin in a more detailed examination included salmonellosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme disease, atypical protracted course of common viral diseases, infectious mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus infection, hepatitis, histoplasmosis. Inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatic fever, Kawasaki disease can also cause fever of unknown origin. In these cases, it is recommended to re-examine the patient after a certain period of time.

In children under 6 years of age, fever of unknown origin is associated with infection of the respiratory or urogenital tract, localized infection (abscess, osteomyelitis), juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, rarely leukemia. Adolescents are more likely to have tuberculosis, an inflammatory process in the intestines, an autoimmune process, and lymphoma. The empiric use of antibiotics should be avoided. In unclear cases, hospitalization may be required for x-ray and laboratory examinations, closer observation, temporary relief from the anxiety of the child and parents. Once fully adequately assessed, antipyretics may be indicated for fever control and symptomatic treatment.

Fever less than 38–38.5°C in previously healthy children generally does not require treatment. If this level is exceeded, the state of health of patients worsens, and the appointment of antipyretics improves the condition. Antipyretics generally do not change the course of infectious diseases in normal children and are symptomatic. Heat production associated with fever increases oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and cardiac output. Thus, fever may worsen heart failure in patients with heart disease or chronic anemia (eg, sickle cell anemia), pulmonary insufficiency in patients with chronic lung disease, and metabolic disorders in children with diabetes, congenital metabolic disorders. Moreover, in children between 6 months. and 5 years, the risk of febrile seizures is increased, and in children with idiopathic epilepsy, febrile illness may increase the frequency of seizures. Antipyretics are prescribed in high-risk patients, ie. having chronic cardiopulmonary diseases, metabolic, neurological diseases, and children with a high risk of developing febrile seizures. Hyperpyrexia (> 41°C) is associated with severe infections, hypothalamic disorders, and central nervous system hemorrhage and always requires antipyretics.

When choosing antipyretics for children, it is especially important to focus on drugs with the lowest risk of side effects. Currently, only paracetamol and ibuprofen fully meet the criteria for high efficacy and safety and are officially recommended by the World Health Organization and national programs in pediatric practice as antipyretics [1–3]. Acetaminophen, aspirin, and ibuprofen are hypothalamic cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors that inhibit the synthesis of PGE-2. These drugs are considered equivalent effective antipyretics. Since aspirin is associated with Reye's syndrome in children and adolescents, it is not recommended for use in the treatment of fever. Paracetamol and ibuprofen can be prescribed to children from the first months of life (from 3 months of age). Recommended single doses: paracetamol - 10-15 mg / kg, ibuprofen - 5-10 mg / kg. Re-use of antipyretics is possible not earlier than after 4-5 hours, but not more than 4 times a day.

It should be noted that the mechanism of action of these drugs is somewhat different. Paracetamol has an antipyretic, analgesic and very slight anti-inflammatory effect, since it blocks COX mainly in the central nervous system and does not have a peripheral effect, it is metabolized by the cytochrome P-450 system. The delay in the excretion of the drug and its metabolites can be observed in violation of the functions of the liver and kidneys. If a child has a deficiency of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and glutathione reductase, the administration of paracetamol can cause hemolysis of red blood cells, drug-induced hemolytic anemia.

Ibuprofen has a pronounced antipyretic, analgesic and anti-inflammatory effect. Ibuprofen is effective against fever in the same way as paracetamol [4–6]. A number of studies have shown that the antipyretic effect of ibuprofen at a dose of 7.5 mg/kg is higher than that of paracetamol at a dose of 10 mg/kg and acetylsalicylic acid at a dose of 10 mg/kg [7]. Ibuprofen blocks COX both in the central nervous system and in the focus of inflammation (peripheral mechanism), which determines its antipyretic and anti-inflammatory effect. As a result, the phagocytic production of mediators of the acute phase, including IL-1 (endogenous pyrogen), decreases. A decrease in the concentration of IL-1 also contributes to the normalization of temperature. The analgesic effect of ibuprofen is determined by both peripheral and central mechanisms, which makes it possible to effectively use ibuprofen for mild and moderate sore throat, pain with tonsillitis, acute otitis media, and toothache [8]. An indication for the appointment of ibuprofen is also hyperthermia after immunization.

Due to its high toxicity, amidopyrine has been excluded from the nomenclature of drugs. The use of analgin in many countries of the world is sharply limited due to the risk of developing agranulocytosis. In urgent situations, such as hyperthermic syndrome, acute pain in the postoperative period, and others that are not amenable to other therapy, parenteral use of analgin and metamizole-containing drugs is acceptable.

Comparison in double-blind, randomized trials with multiple doses of antipyretics showed that the incidence of adverse events was similar between ibuprofen and paracetamol (8–9%) [3]. The results of a large randomized study of more than 80,000 children showed that the use of ibuprofen compared with paracetamol does not increase the risk of hospitalization associated with gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure or anaphylaxis. When using ibuprofen and paracetamol in children with bronchial asthma [3], it has been shown that the use of ibuprofen, compared with acetaminophen, does not increase the risk of bronchospasm in children with bronchial asthma who do not have indications of aspirin intolerance, which indicates the relative safety of ibuprofen in children with bronchial asthma .

According to the experts of IC "MAKS" (Vladimir), paracetamol and ibuprofen are most often used in pediatric practice (Table 1).

We used Nurofen for children (ibuprofen) in 95 children aged 3 months and older. up to 10 years old. The indication was fever in acute respiratory infections, acute otitis media, tonsillopharyngitis, obstructive bronchitis, bronchiolitis, pneumonia. 43 children of the first three years of life were hospitalized in the regional children's hospital due to the severity of the condition. In 20 children, acute respiratory infections occurred against the background of mild to moderate bronchial asthma without indications of aspirin intolerance, in 37 children obstructive bronchitis and bronchiolitis were diagnosed. The average value of the initial axillary temperature was 39.1 ± 0.6 °С. Nurofen for children was prescribed at the rate of 5 mg/kg, on the first day - 3-4 times, on the second day - 2-3 times; the third day and beyond - according to indications. Most children were prescribed the drug for no more than 2 days. In 40-60 minutes after taking the drug, the temperature decreased to 37.9 ± 0.4 °C, after 90-120 minutes - to 37.3 ± 0.5 °C. Adverse events were noted in 2 children in the form of an allergic rash, in 1 child - abdominal pain, exacerbation or provocation of bronchospasm was not observed in any case. In 6 children, the effect of taking ibuprofen was minimal and short-lived: 2 children were prescribed diclofenac, 4 others received parenteral lytic mixture. The drug was rated as effective 90.7% of physicians and 93.7% of parents.

In 84 patients, short-term use of ibuprofen and paracetamol did not increase the risk of developing toxic changes in the kidneys [3]. An increase in the level of urea nitrogen and creatinine occurs in children who initially had a risk of developing complications from the side of the kidneys due to relevant diseases (renal failure, congenital heart failure, liver dysfunction) or a pronounced clinical picture of dehydration.