Advice on miscarriage

Miscarriage - NHS

A miscarriage is the loss of a pregnancy during the first 23 weeks.

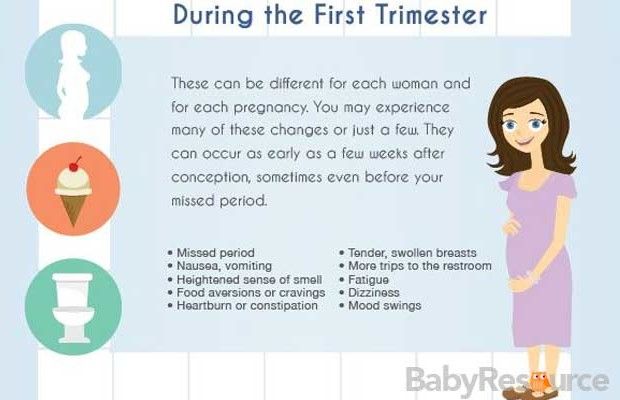

Symptoms of a miscarriage

The main sign of a miscarriage is vaginal bleeding, which may be followed by cramping and pain in your lower abdomen.

If you have vaginal bleeding, contact a GP or your midwife.

Most GPs can refer you to an early pregnancy unit at your local hospital straight away if necessary.

You may be referred to a maternity ward if your pregnancy is at a later stage.

But bear in mind that light vaginal bleeding is relatively common during the first trimester (first 3 months) of pregnancy and does not necessarily mean you're having a miscarriage.

Causes of a miscarriage

There are potentially many reasons why a miscarriage may happen, although the cause is not usually identified.

The majority are not caused by anything you have done.

It's thought most miscarriages are caused by abnormal chromosomes in the baby.

Chromosomes are genetic "building blocks" that guide the development of a baby.

If a baby has too many or not enough chromosomes, it will not develop properly.

In most cases, a miscarriage is a one-off event and most people go on to have a successful pregnancy in the future.

Preventing a miscarriage

The majority of miscarriages cannot be prevented.

But there are some things you can do to reduce the risk of a miscarriage.

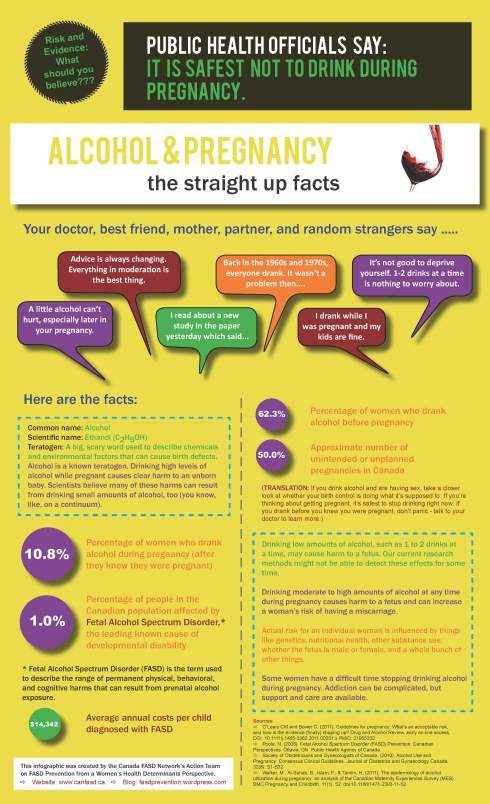

Avoid smoking, drinking alcohol and using drugs while pregnant.

Being a healthy weight before getting pregnant, eating a healthy diet and reducing your risk of infection can also help.

What happens if you think you're having a miscarriage

If you have the symptoms of a miscarriage, you'll usually be referred to a hospital for tests.

In most cases, an ultrasound scan can determine if you're having a miscarriage.

When a miscarriage is confirmed, you'll need to talk to your doctor or midwife about the options for the management of the end of the pregnancy.

Often the pregnancy tissue will pass out naturally in 1 or 2 weeks.

Sometimes medicine to assist the passage of the tissue may be recommended, or you can choose to have minor surgery to remove it if you do not want to wait.

After a miscarriage

A miscarriage can be an emotionally and physically draining experience.

You may have feelings of guilt, shock and anger.

Advice and support are available at this time from hospital counselling services and charity groups.

You may also find it beneficial to have a memorial for the baby you lost.

You can try for another baby as soon as your symptoms have settled and you're emotionally and physically ready.

It's important to remember that most miscarriages are a one-off and are followed by a healthy pregnancy.

How common are miscarriages?

Miscarriages are much more common than most people realise.

Among people who know they're pregnant, it's estimated about 1 in 8 pregnancies will end in miscarriage.

Many more miscarriages happen before a person is even aware they're pregnant.

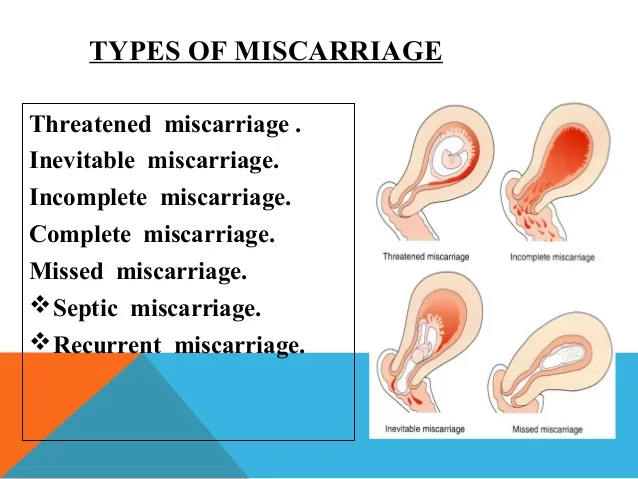

Losing 3 or more pregnancies in a row (recurrent miscarriages) is uncommon and only affects around 1 in 100 women.

Page last reviewed: 09 March 2022

Next review due: 09 March 2025

Miscarriage - Afterwards - NHS

A miscarriage can have a profound emotional impact on you and also on your partner, friends and family.

Advice and support are available during this difficult time.

Remembrance

It's usually possible to arrange a memorial and burial service if you want one. In some hospitals or clinics it may be possible to arrange a burial within the grounds.

You can also arrange to have a burial at home, although you may need to consult your local authority before doing so.

Cremation is an alternative to burial and can be performed at either the hospital or a local crematorium. However, not all crematoriums provide this service and there will not be any ashes for you to scatter afterwards.

However, not all crematoriums provide this service and there will not be any ashes for you to scatter afterwards.

You do not need to formally register a miscarriage. However, some hospitals can provide a certificate to mark what has happened if you want one.

Emotional impact

Sometimes the emotional impact is felt immediately after the miscarriage, whereas in other cases it can take several weeks. Many people affected by a miscarriage go through a bereavement period.

It's common to feel tired, lose your appetite and have difficulty sleeping after a miscarriage. You may also feel a sense of guilt, shock, sadness and anger – sometimes at a partner, or at friends or family members who have had successful pregnancies.

Different people grieve in different ways. Some people find it comforting to talk about their feelings, while others find the subject too painful to discuss.

Some people come to terms with their grief after a few weeks of having a miscarriage and start planning for their next pregnancy. For others, the thought of planning another pregnancy is too traumatic, at least in the short term.

If you're in a relationship, it can help to make sure you're both open about how you are feeling.

Your partner may also be affected by the loss.

Men sometimes find it harder to express their feelings, particularly if they feel their main role is to support the mother and not the other way round.

Miscarriage can also cause feelings of anxiety or depression, and can lead to relationship problems.

Getting support

If you're worried that you or your partner are having problems coping with grief, you may need further treatment and counselling. There are support groups that can provide or arrange counselling for people who have been affected by miscarriage.

Read more about dealing with grief and counselling, and find bereavement support services in your area.

Your GP can provide you with support and advice. The following organisations can also help:

- The Miscarriage Association is a charity that offers support to people who have lost a baby. They have a helpline (01924 200 799) and an email address ([email protected]) and can put you in touch with a support volunteer.

- Cruse Bereavement Care helps people understand their grief and cope with their loss. They have a helpline (0808 808 1677) and a network of local branches where you can find support.

When can I have sex again after a miscarriage?

You should avoid having sex until all of your miscarriage symptoms have gone. Your periods should return within 4 to 8 weeks of your miscarriage, although it may take several months to settle into a regular cycle.

If you do not want to get pregnant, you should use contraception immediately. If you do want to get pregnant again, you may want to discuss it with your GP or hospital care team. Make sure you are feeling physically and emotionally well before trying for another pregnancy.

The Miscarriage Association has information on thinking about another pregnancy that you may find helpful. It's important to remember that most miscarriages are a one-off and are followed by a healthy pregnancy.

Although it's not usually possible to prevent a miscarriage, there are some ways you can reduce the risk. See preventing miscarriage for more information and advice.

Finding a cause

It's natural to want to know why a miscarriage happened, but unfortunately this is not always possible. Many miscarriages are thought to be caused by a one-off problem with the development of the foetus.

Read more about the causes of miscarriage.

Page last reviewed: 09 March 2022

Next review due: 09 March 2025

Miscarriage, The role of IVF and PGD in prevention

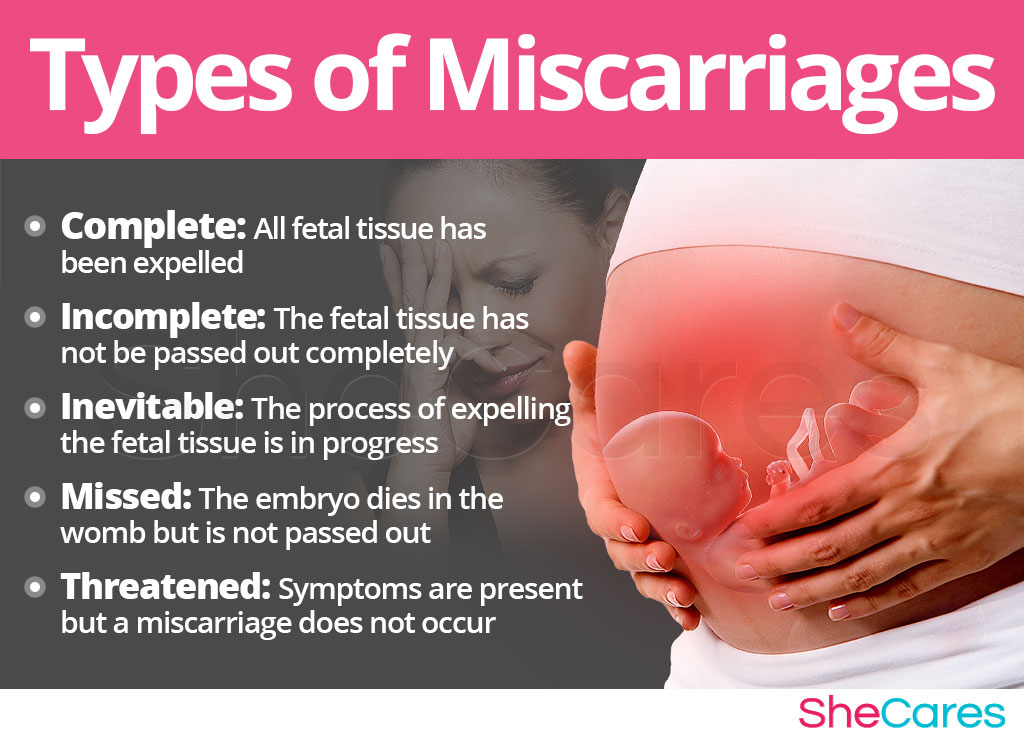

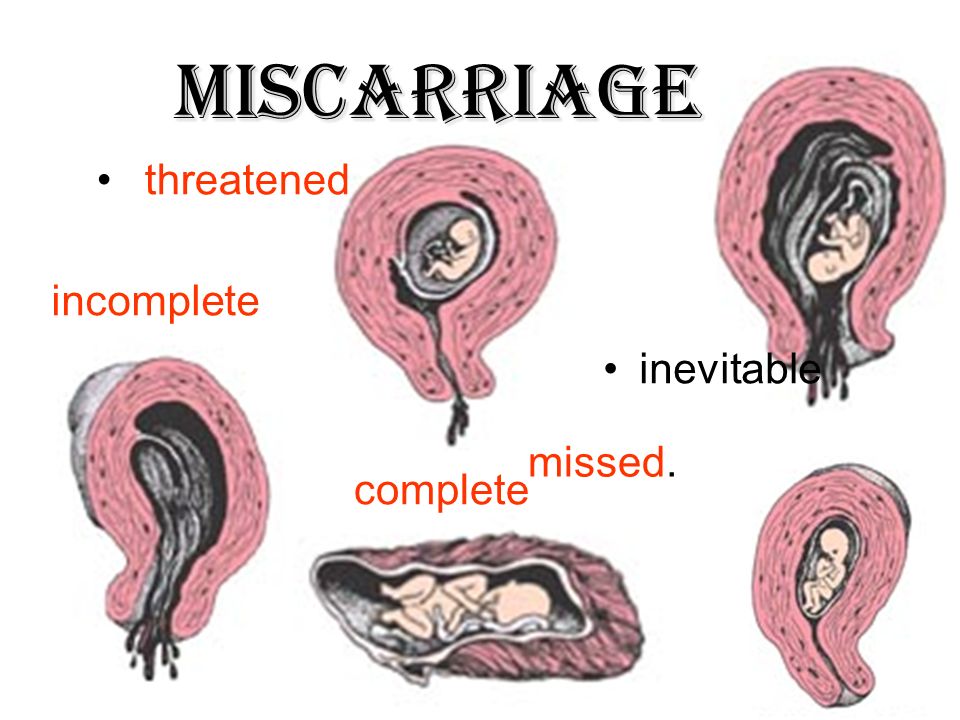

Miscarriage is a spontaneous termination of pregnancy that occurs at any time up to 22 weeks, later - miscarriage is classified as preterm birth. The percentage of pregnant women who, for one reason or another, experience non-embroidery fluctuates between 10-25%.

Successful infertility treatment, unfortunately, does not always result in the birth of a child. The termination of a long-awaited pregnancy becomes a real tragedy for a married couple and for their doctor. nine0003

The reasons for early termination of pregnancy are often unknown, although chromosomal abnormalities are usually implied. If a woman has had a miscarriage in the second trimester or two or more in the first trimester, tests are recommended to help determine the cause.

Make an appointment

Most cases of miscarriage are observed in women who have been treated for infertility, including IVF. However, the IVF procedure itself cannot in any way be the cause of a miscarriage. nine0003

Causes of miscarriage:

Chromosomal problems

Up to 70% of all miscarriages occurring in the first trimester are due to abnormalities of the somatic chromosomes in the fetus. Most fetal chromosomal abnormalities result from the involvement of a defective egg or sperm in fertilization.

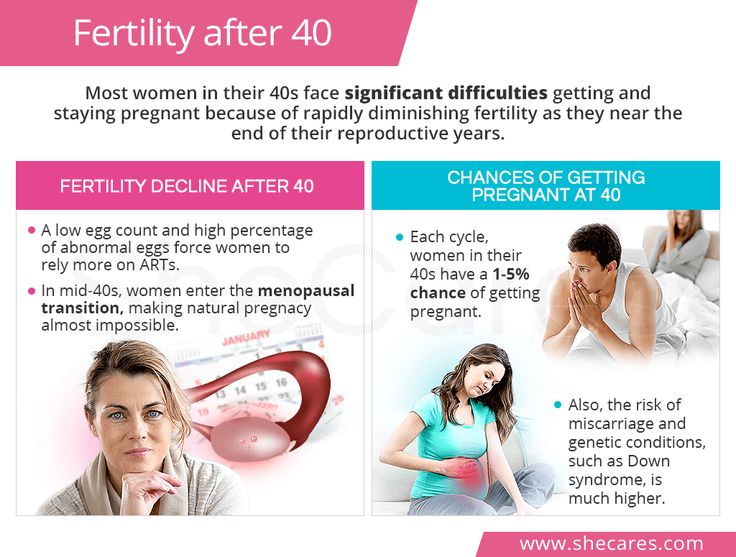

In such cases, the resulting embryo has a chromosomal abnormality, which leads to an undeveloped pregnancy. Chromosomal abnormalities increase with age. nine0003

Women over 35 have a higher risk of miscarriage than younger women. Recent studies show that a father's age over 40 also increases the risk of miscarriage.

Pathology of the uterus

In 10-15% of cases, uterine anomalies (congenital malformations, septa in the uterine cavity, fibroids, adenomyosis, cicatricial postoperative changes) are the cause of miscarriage, both in the first and second trimesters.

Isthmic-cervical insufficiency (weakness of the muscular ring of the cervix) can lead to miscarriage, usually between 16 and 18 weeks of pregnancy. nine0003

Hormonal causes

If the body produces too much or too little of certain hormones, the risk of miscarriage increases. Hyperandrogenism, luteal phase deficiency, hypo- and hyperthyroidism, hyperprolactemia, diabetes mellitus can cause abortion.

Autoimmune problems

While everyone's body produces proteins called antibodies to fight infections, some people's bodies produce antibodies (autoantibodies) that can attack the body's own tissues, causing a range of health problems. nine0003

They can cause infertility or miscarriage.

Certain types of autoantibodies (such as anticardiolipin or lupus anticoagulant) cause blood clots that can block the blood supply to the uterus. Mutations in the blood coagulation system can also be the cause of recurrent miscarriage.

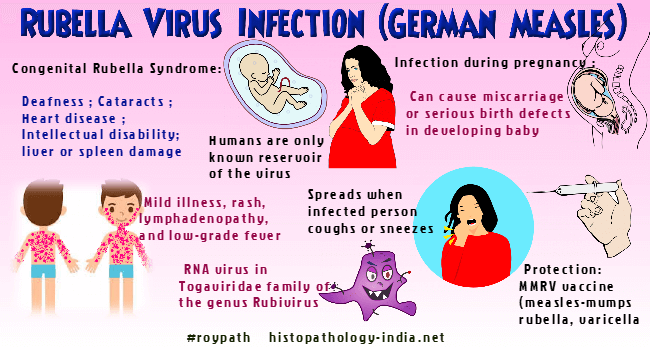

Infections and other factors

Termination of pregnancy due to an inflammatory process is caused by the penetration of infectious agents from the mother's body through the placenta to the fetus. The infection is most dangerous during pregnancy. nine0003

The infection is most dangerous during pregnancy. nine0003

The presence of microorganisms in the mother may be asymptomatic or accompanied by characteristic signs of an inflammatory disease. Bacteria (gram-negative and gram-positive cocci, listeria, treponema and mycobacteria), protozoa (toxoplasma, plasmodia) and viruses can enter the fetus from the mother.

Spouses should also discuss the possible impact of chemicals in their workplace with their doctor.

A woman is not advised to try to conceive until she is physically and emotionally ready for it and has completed all the tests recommended to determine the cause of the miscarriage. nine0003

From a medical point of view, conception is safe from the moment of at least one menstrual cycle (unless investigations or treatment of the causes of previous miscarriage are performed). However, it may take a much longer time before a woman is emotionally ready for pregnancy. Fortunately, the vast majority of women who have had one or two miscarriages successfully carry on with their next pregnancy.

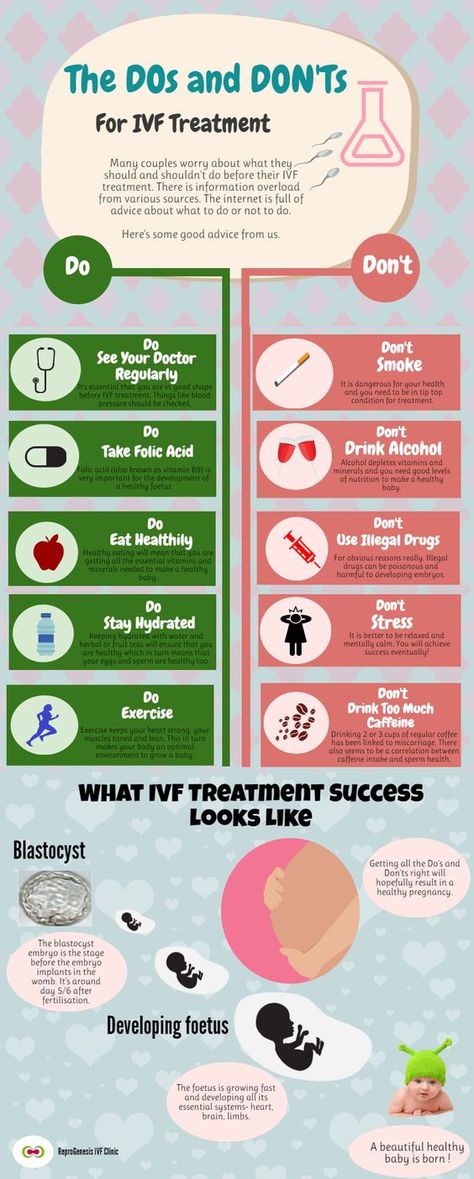

In difficult cases, there are special treatments using preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). PGD allows for genetic testing of the embryo before it is transferred into the uterine cavity. This technique is carried out as part of the IVF program and allows you to transfer into the uterine cavity only "healthy" embryos that do not have certain genetic diseases. nine0003

They can not only lead to miscarriage, but also provoke infertility.

When can I get pregnant after a miscarriage?

A woman is not advised to try to conceive until she is physically and emotionally ready for it and has completed all the tests recommended to determine the cause of the miscarriage.

From a medical point of view, conception is safe from the moment of passing at least one menstrual cycle (unless investigations or treatment of the causes of previous miscarriage are performed). nine0003

However, it may take a much longer time before a woman is emotionally ready for pregnancy. Fortunately, the vast majority of women who have experienced one or two miscarriages do not suffer from infertility and successfully carry their next pregnancy to term.

Fortunately, the vast majority of women who have experienced one or two miscarriages do not suffer from infertility and successfully carry their next pregnancy to term.

Preparation for pregnancy in case of recurrent miscarriage

If there have already been 2 or more cases of spontaneous abortion, preparation is necessary before the next conception of a child. The reproductive specialist will prescribe a series of studies aimed at identifying the cause of miscarriage. Many diagnostic measures are similar to those prescribed for infertility. Woman to be:

- take a blood test for hormones - to identify the endocrine factor;

- get swabs and blood tests for infections;

- visit a hemostasiologist;

- pass an extended coagulogram;

- get advice from a geneticist;

- undergo instrumental studies to diagnose possible inflammatory diseases of the genital organs and detect uterine factor.

A man should also visit a geneticist, as well as pass a spermogram and analysis for sperm DNA fragmentation. It is likely that it is the male germ cells that carry defective genetic material. It can cause both infertility and miscarriage. nine0003

It is likely that it is the male germ cells that carry defective genetic material. It can cause both infertility and miscarriage. nine0003

The choice of investigations in a woman largely depends on the trimester in which the miscarriage occurs. So, in the first trimester, the endocrine factor becomes the cause of miscarriage much more often, so the most important are the studies of the level of hormones in the blood. In the second trimester, disorders in the hemostasis system or uterine factor (isthmic-cervical insufficiency) often come to the fore.

Further preparation for pregnancy may involve:

- hormonal correction;

- treatment of inflammatory diseases of the pelvic organs;

- elimination of disturbances in the hemostasis system;

- surgical treatment if there is a uterine miscarriage factor;

- IVF with PGD in case of suspicion of a genetic factor.

What can a woman do to prevent miscarriage?

Episodes of abortion do not always indicate a pathological process. It is likely that the examination will not reveal violations, and then the next pregnancy will end in childbirth. nine0003

It is likely that the examination will not reveal violations, and then the next pregnancy will end in childbirth. nine0003

In order to increase the chances of success, you need to:

- undergo a medical examination in a timely manner;

- eliminate heavy physical exertion;

- normalize sleep and wakefulness;

- exclude alcohol and smoking;

- avoid crowded places in order to prevent SARS infection;

- monitor the state of somatic health;

- avoid stress. nine0081

The greatest risk of miscarriage is present in the first trimester of pregnancy (80% of all spontaneous abortions). Therefore, it is during this period that a woman should more carefully monitor her health, lifestyle, daily routine.

The role of IVF and PGD in the prevention of miscarriage

IVF is the most effective method to overcome infertility. As part of this procedure, preimplantation genetic diagnosis can be performed. The essence of the method is to study one of the cells of the embryo to identify chromosomal and gene mutations. They are the most common cause of habitual miscarriage. nine0003

They are the most common cause of habitual miscarriage. nine0003

The risk group includes women over 35 years of age, as well as patients with relatives with genetic pathologies, working in hazardous industries, having bad habits.

IVF with PGD is recommended in cases where a woman has several episodes of spontaneous abortion, and the cause of this phenomenon cannot be determined. This procedure may also be recommended by a geneticist based on the results of an examination of a married couple.

IVF in this case will not only increase the chances of successful childbearing, but will also facilitate the process of achieving pregnancy, because in vitro fertilization is one of the most effective methods of overcoming infertility. nine0003

In turn, PGD will allow to examine embryos for mutations and select a “healthy” embryo for transfer to the uterus. This virtually eliminates the risk of genetic and chromosomal abnormalities that can lead to miscarriage.

Webinar on "Miscarriage"

Preconception preparation for women with a history of miscarriage | Pustotina

1. BergheLLa V. Early pregnancy loss: in book Obstetric Evidence Based Guidelines. second edition. New York: CRC Press, 2012: 142-149.

BergheLLa V. Early pregnancy loss: in book Obstetric Evidence Based Guidelines. second edition. New York: CRC Press, 2012: 142-149.

2. Howard JA. carp. Recurrent pregnancy Loss: causes, controversies and treatment. second edition. New York: CRC Press; 2015: 1-16.

3. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy Loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril, 2012, 98(5): 1103-11.

4. Jaslow CR, Carney JL, Kutteh WH. Diagnostic factors identified in 1020 women with two versus three or more recurrent pregnancy losses. Fertil Steril, 2010, 93: 1234-43. nine0003

5. Clinical guidelines. Obstetrics and gynecology. 4th ed., revised. and additional Ed. V.N. Serov, G.T. Dry. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2014: 62-104.

6. Lathi RB, Gray Hazard FK, Heerema-McKenney A et al. First trimester miscarriage evaluation. Semin Reprod Med, 2011:29:463-9.

7. Berghella V. Preconception care: in book Obstetric Evidence Based Guidelines. 2nd Edition. Ed. by Berghella V. 2012: 1-11.

2nd Edition. Ed. by Berghella V. 2012: 1-11.

8. Jack BW, Culpepper L, Babcock J et al. Addressing preconception risks identified at the time of a negative pregnancy test: a randomized trial. J Fam Practice, 1998, 47: 33-38.

9. Rumbold A, Middleton P, Pan N, Crowther CA. Vitamin supplementation for preventing miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011, 1: CD004073.

10. Ota E, Hori H, Mori R et al. Antenatal dietary education and supplementation to increase energy and protein intake. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015, 6: CD000032.

11. Lund M, Kamper-Jcrgensen M, Nielsen HS et al. Prognosis for live birth in women with recurrent miscarriage: What is the best measure of success? Obstet Gynecol, 2012, 119: 37-43.

12. Boue A, Gallano P. A collaborative study of the segregation of inherited chromosome structural arrangements in 1356 prenatal diagnoses. Prenat Diagn., 1984, 4:45-67.

13. Grati FR, Barlocco A, Grimi B et al. Chromosome abnormalities investigated by non-invasive prenatal testing account for approximately 50% of fetal unbalances associated with relevant clinical phenotypes. Am J Med Genet A, 2010, 152A: 1434-42.

Am J Med Genet A, 2010, 152A: 1434-42.

14. Carp HJA, Feldman B, Oelsner G et al. Parental karyotype and subsequent live births in recurrent miscarriage. Fertil Steril, 2004, 81: 1296-301.

15. Werner M, Reh A, Grifo J et al. Characteristics of chromosomal abnormalities diagnosed after spontaneous abortions in an infertile population. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2012, 29: 817-20.

16. Sugiura-Ogasawara M, Ozaki Y, Katano K et al. Abnormal embryonic karyotype is the most frequent cause of recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod, 2012, 27:2297-303.

17. Chen I, Jhangri GS, Chandra S Relationship between interpregnancy interval and congenital anomalies. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2014, 210(6): 564.e18. nine0003

18. Sugiura-Ogasawara M, Ozaki Y, Katano K et al. Uterine anomaly and recurrent pregnancy loss. Semin Reprod Med, 2011, 29:514-21.

19. Jaslow CR, Kutteh WH. Effect of prior birth and miscarriage on the prevalence of acquired and congenital uterine anomalies in women with recurrent miscarriage: A cross-sectional study. Fertil Steril, 2013, 99: 1916-22.

Fertil Steril, 2013, 99: 1916-22.

20. Ziakas PD, Pavlou M, Voulgarelis M. Heparin treatment in antiphospholipid syndrome with recurrent pregnancy loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 115: 1256-62. nine0003

21. Laskin CA, Bombardier C, Hannah ME, et al. Prednisone and aspirin in women with autoantibodies and unexplained recurrent fetal loss. N Engl J Med, 1997, 337: 148-53.

22. Porter TF, LaCoursiere Y, Scott JR. Immunotherapy for recurrent miscarriage. The Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, 2006: CD000112.

23. Hutton B, Sharma R, Fergusson D et al. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of recurrent miscarriage: A systematic review. BJOG, 2007, 114: 134-42. nine0003

24. Silver R, Zhao Y, Spong Y et al. Prothrombin gene G20210A mutation and obstetric complications. Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 115:14-20.

25 Said JM, Higgins J, Moses E et al. Inherited thrombophilia polymorphisms and pregnancy outcomes in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 115: 5-13.

Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 115: 5-13.

26. Virkus RA, Lokkegaard E, Lidegaard O et al. Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism in 1.3 Million Pregnancies: A Nationwide Prospective Cohort. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(5): e96495.

27. Lockwood C, Wendel G, Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. practice bulletin no. 124: Inherited thrombophilias in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol, 2011, 118: 730-40.

28. Airoldi JA. Inherited thrombophilia: in book Maternal-Fetal Evidence Based Guidelines. 2nd Edition. Ed. by Berghella V. 2012: 207-2014.

29. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Inherited thrombophilias in pregnancy. Practice Bulletin No. 113. Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 116: 212-222. nine0003

30. Vollset SE, Refsum H, Irgens LM, et al. Plasma total homocysteine, pregnancy complications, and adverse pregnancy outcomes: the Hordaland Homocysteine study. Am J Clin Nutr, 2000, 71: 962-968.

31. Wang X, Oin X, Demirtas H, Li J et al. Efficacy of folic acid supplementation in stroke prevention: a meta-analysis.:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/hemorrhage-in-miscarriage-meaning-2371523-FINAL-f2ab04cab1cc491e964a45e682f93da5.png) Lancet, 2007, 369: 1876-82.

Lancet, 2007, 369: 1876-82.

32. Penta M, Lukic A, Conte MP et al. Infectious agents in tissues from spontaneous abortions in the first trimester of pregnancy. New Microbiol, 2003, 26: 329-37.

33. Bothuyne-Oueste E et al. Is the bacterial vaginosis risk factor of prematurity? Study of a cohort of 1336 patients in the hospital of Arras. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod, 2012, 41(3): 262-270.

34. Gurtovoy B.L., Kulakov V.I., Voropaeva S.D. The use of antibiotics in obstetrics and gynecology. M.: Triada-X, 2004. 176 p.

35. Colao A et al., Pregnancy outcomes following cabergoline treatment: extended results from a 12-year observational study. Clinical Endocrinology, 2008, 68: 66-71. nine0003

36 Melmed F et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperprolactinemia: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. JCEM, 2013.

37. Clinical guidelines of the Russian Association of Endocrinologists (RAE). Hyperprolactinemia, 2013.

38. Poppe K, Velkeniers B, Glinoer D. Thyroid disease and female reproduction. Clin Endocrinol, 2007, 66: 309-21.

Thyroid disease and female reproduction. Clin Endocrinol, 2007, 66: 309-21.

39. Soldin OP, Chung SH, Colie C. The Use of TSH in Determining Thyroid Disease: How Does It Impact the Practice of Medicine in Pregnancy? J Thyroid Re, 2013: 148-157. nine0003

40. Melamed N, Hod M. Perinatal mortality in progestational diabetes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2009, 104: S20-4.

41. Ramin N, Thieme R, Fischer S et al. Maternal diabetes impairs gastrulation and insulin and IGF-I receptor expression in rabbit blastocysts. Endocrinology, 2010, 151: 4158-67.

42. Gutaj P, Zawiejska A, Wender-Ozegowska E et al. Maternal factors predictive of first-trimester pregnancy loss in women with pregestational diabetes. Pol Arch Med Wewn, 2013, 123:21-8. nine0003

43. Maryam K, Bouzari Z, Basirat Z et al. The comparison of insulin resistance frequency in patients with recurrent early pregnancy loss to normal individuals. BMC Res Notes, 2012, 5: 133.

44. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Disease State Clinical Review: Guide to the Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Part 2. Endocr. Pract., 2015, 21(12): 1415-1426. nine0003

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Disease State Clinical Review: Guide to the Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Part 2. Endocr. Pract., 2015, 21(12): 1415-1426. nine0003

45. Polycystic ovary syndrome in reproductive age (modern approaches to diagnosis and treatment): Clinical guidelines (treatment protocol). M.: Ministry of Health of Russia, 2015. 22 p.

46. Evidence-based Methodology Workshop on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome December 3-5, 2012. 2012. Bethesda, Maryland: National Institutes of Health, 2012. 14 p.

47. OiO et al. Association of methylenetetrahydro-folate reductase gene polymorphisms with polycystic ovary syndrome. Chin. J. Med. Genet., 2015, 32(3): 400-404. nine0003

48. Chakraborty P, Goswami SK, Rajani S et al. Recurrent pregnancy loss in polycystic ovary syndrome: Role of hyperhomocysteinemia and insulin resistance. PLoS One, 2013, 8: e64446.

49. Kamenov Z. Ovulation induction with myo-ino-sitol alone and in combination with clomi-phene citrate in polycystic ovarian syndrome patients with insulin resistance. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015; 31(2): 131-5

50. Lessey DA. Assessment of endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril, 2011, 96:522-529.

51. Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L for the World Endometriosis Society Montpellier. Consortium Consensus on current management of endo-metriosis. Hum Reprod, 2013, 28(6): 1552-1568.

52. Wetendorf M, DeMayo FJ. The progesterone receptor regulates implantation, decidualiza-tion, and glandular development via a complex paracrine signaling network. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2012, 357: 108-18.

53. Bergquist A, Ferno M. Oestrogen and progesterone receptors in endometriotic tissue and endometrium: Comparison of different cycle phases and ages. Hum Reprod, 1993, 8: 2211-7.

54. Clinical guidelines. Obstetrics and gynecology. 4th ed., rev. and enl. Ed. by V.N. Serov, G.