Making friends for children

10 Practical Ways to Help Kids Make New Friends

Friendliness, and the confidence to make friends, is important for all children to develop so they can get along with others. Sometimes as adults who have had so many experiences meeting new people, we may forget how hard it can be for our kids to put themselves out there and talk to people they do not know. We may not give a second thought to a situation where we need to make a new friend if a best friend is absent, but this may feel like a huge deal to our young child.

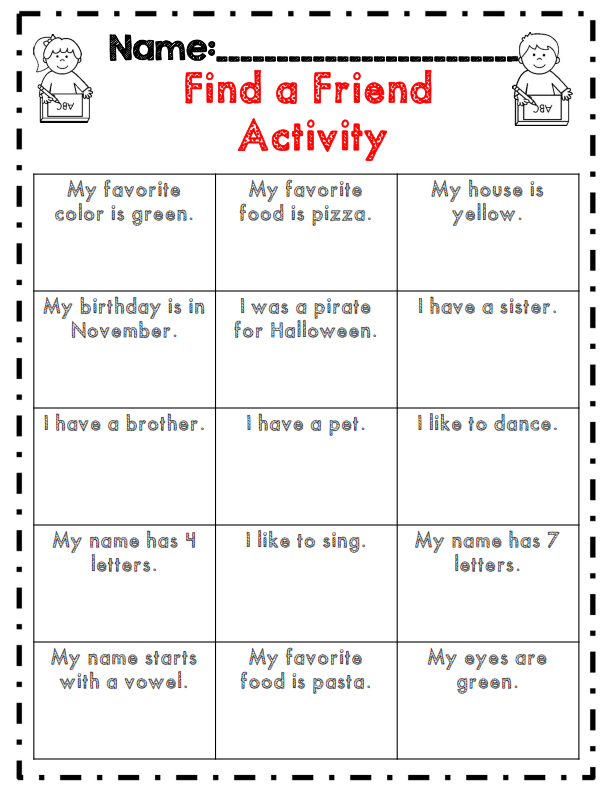

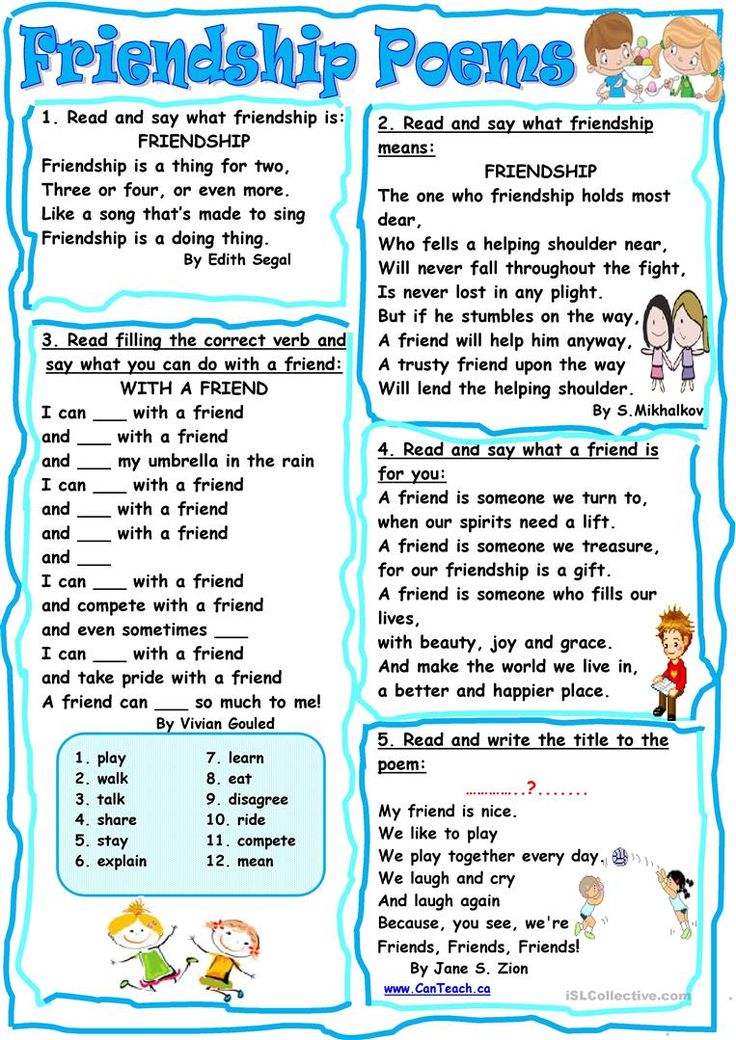

Making new friends can be easier if children are prepared ahead of time with ideas for interacting with others. Here are 10 activities to help kids make friends:

1) Learn a joke.

Jokes are a fun way to ease up tension. Even small children might enjoy saying, “Do you know any jokes?” and then sharing one or two with a new friend. Check out this set of 30 jokes if you would like to learn some new ones to teach your kids.

2) Practice introductions and asking questions.

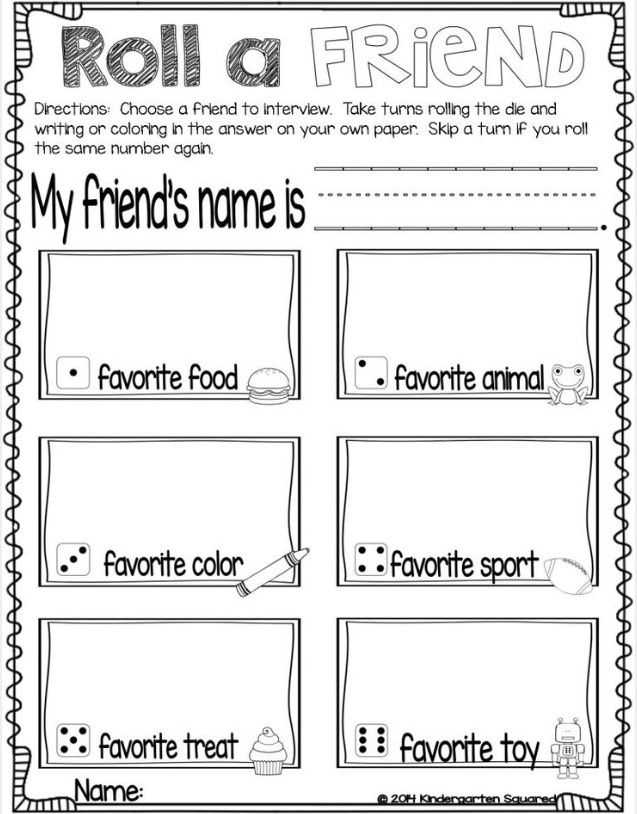

Help your child make-believe that they are meeting a new friend by using a puppet. Encourage your child to find out more about the puppet by asking them their name, their favorite games, favorite foods, etc. This will help your child realize that questions are a way to find things in common with someone new, and can instil confidence to begin a conversation in the future.

3) Write a list of simple games.

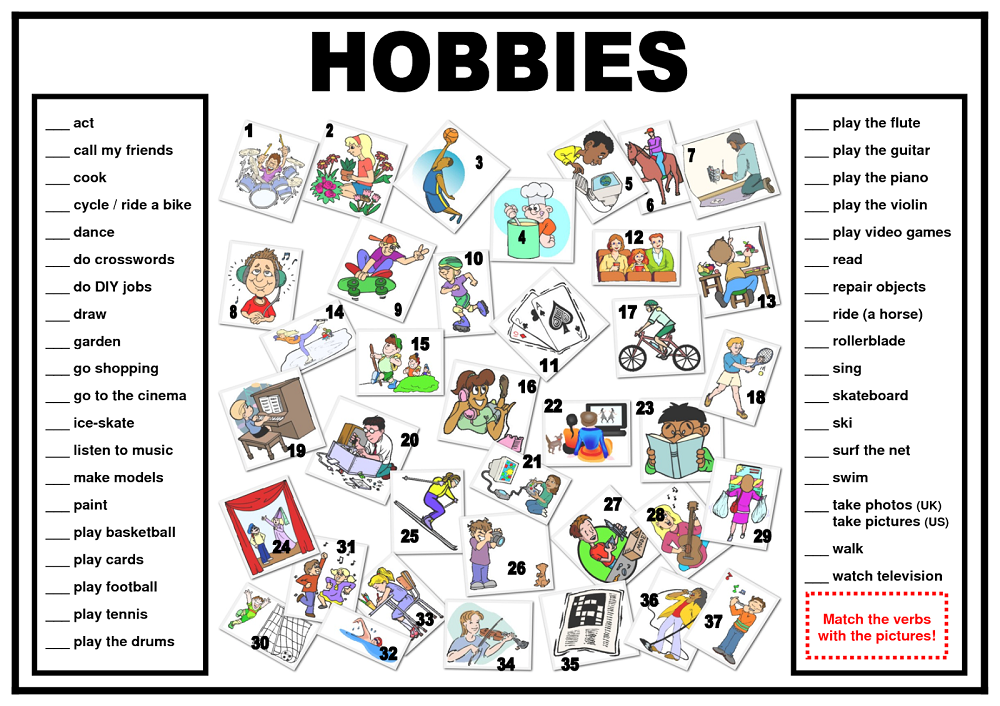

Sometimes children can be anxious about what they will play with other kids (“What will we do?!”). Take out a piece of paper and make a list of five or more games that you child would like to play with someone else. This way they are ready to go up and ask someone to play a game with them, or they are prepared with some ideas if someone new comes up to them.

4) Look for what other children are interested in.

Show your child that sometimes you can find clues about what someone likes by what they are wearing or doing. For example, if a person has a dinosaur back pack or always goes straight to the puzzles, you may like to begin a conversation about one of these topics. Help your child look through storybooks or magazines and find clues about peoples’ interests. This can give you a topic to talk about.

For example, if a person has a dinosaur back pack or always goes straight to the puzzles, you may like to begin a conversation about one of these topics. Help your child look through storybooks or magazines and find clues about peoples’ interests. This can give you a topic to talk about.

5) Smile!

Look in the mirror to see what you look like when you are smiling. Doesn’t that look inviting? Help your child practice smiling and let them know how this is a great way to invite someone into conversation.

6) Practice making a new friend at the park.

If your child is hesitant to make new friends at school, use the park as a place to practice creating friendships. It may be less intimidating outside the classroom environment to talk to someone new. You may like to help your child by walking with them and asking a new friend’s name, before letting your child take control of the conversation.

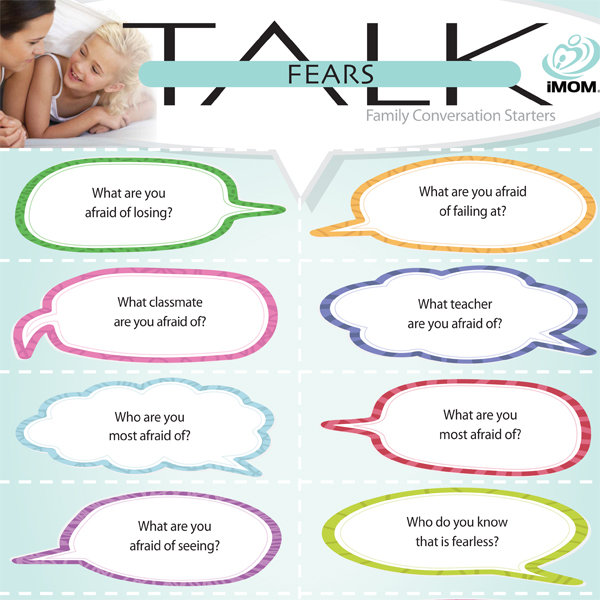

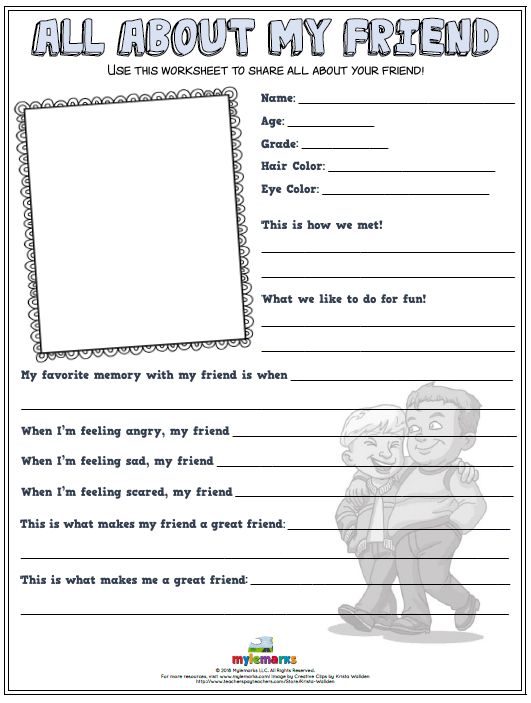

7) Ask extended family for stories.

Get grandparents, aunties and uncles to share experiences of making friendships when they were little. Did they have lots of friends? What did they like to play with their friends? What did they think made a good friend? Looking at pictures of relatives when they were children can form a very special memory as well.

8) Play “What If?”

This is a fun and silly game to help ease anxiety – think about the best and worst thing that could happen if you do what you fear. In the case of making friends, it may be “What would happen if you go up and ask others to play?” to which your child will share their expectations. If the child thinks of a negative experience, ask them what they would do afterwards. Sometimes envisioning what would happen, and sharing ways to deal with it, can give someone the confidence to try… because they realize that it is not a very big deal if things don’t go perfectly.

9) Read books.

Use stories to help your child realize that making friends is something everyone has to do, and is a natural part of life. Here is a list of books about making friends from My Little Bookcase. You can also create your own storybook using pictures of your child and showing ways they can interact with others to form friendships.

Here is a list of books about making friends from My Little Bookcase. You can also create your own storybook using pictures of your child and showing ways they can interact with others to form friendships.

10) Make a plan.

Help your child visualize creating friendships by talking through situations. Talk about what they do when they go into class or to a playground, and brainstorm ways they can go up to others and talk to them. You may like to draw out a storyboard of action steps they can take to meet new people, including what they will do if someone answers “no” when they ask to play.

In Make Friends: Life Skills for Kids from Lessons Learnt Journal, there is a lovely video of four mothers (and teachers) discussing other ways they have helped their children develop friendships.

Do you or your children have any favorite strategies for making new friends? Please share your success stories and ideas in the comments.

Filed Under: Blog, Character Building Activities, Home Activities Tagged With: Friendliness

About Chelsea Lee Smith

Author, certified parent educator, and mother of three with a background in Communications and Counselling, Chelsea provides resources to parents and teachers who want to incorporate personal growth into everyday moments. Follow her @momentsaday on Facebook, Pinterest and Instagram.

Subscribe To The Newsletter

E-MailHelp kids make friends: 12 evidence-based tips

© 2009 – 2020 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

How can we help kids make friends? It might seem we can do very little. Making friends is a very personal business, after all. But building a friendship depends on a child’s emotional skills, self-regulation skills, and social competence. And parents can play an important role in the development of these abilities.

For example, many children have trouble making friends because they feel shy or anxious. If we show these kids how to respond to friendly overtures — and provide them with easy, safe opportunities for interacting with friendly people — we can help them build crucial social connections.

If we show these kids how to respond to friendly overtures — and provide them with easy, safe opportunities for interacting with friendly people — we can help them build crucial social connections.

Likewise, there are children who struggle because they lack adequate impulse control, or behave in ways that antagonize others. These kids will find it much easier to make friends if we help them develop their self-regulation skills.

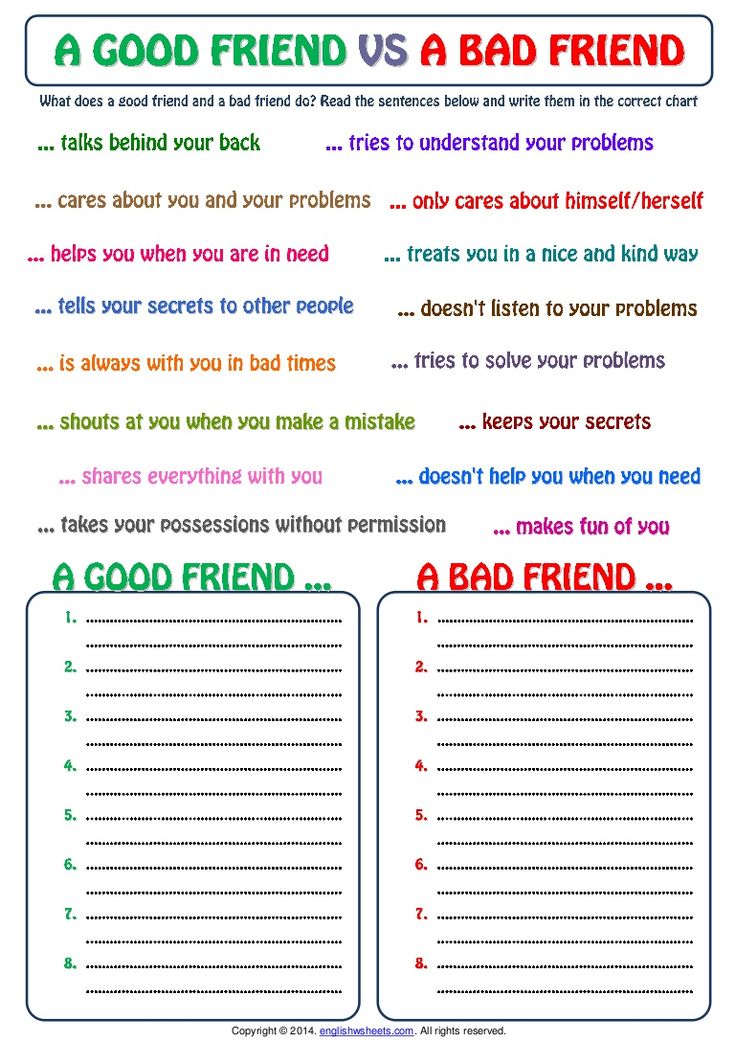

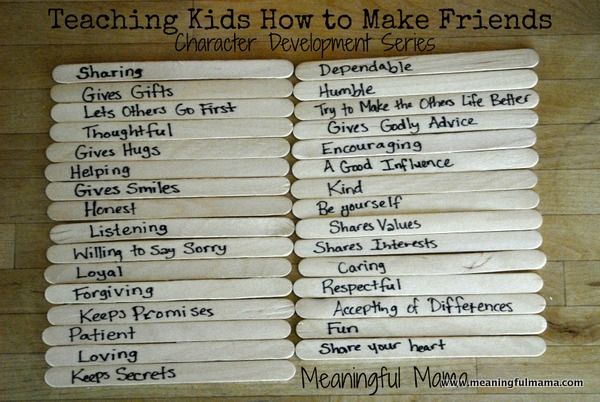

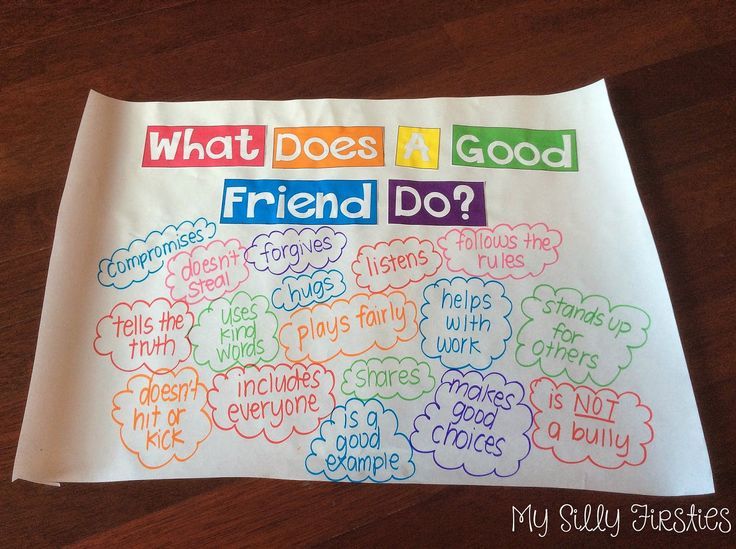

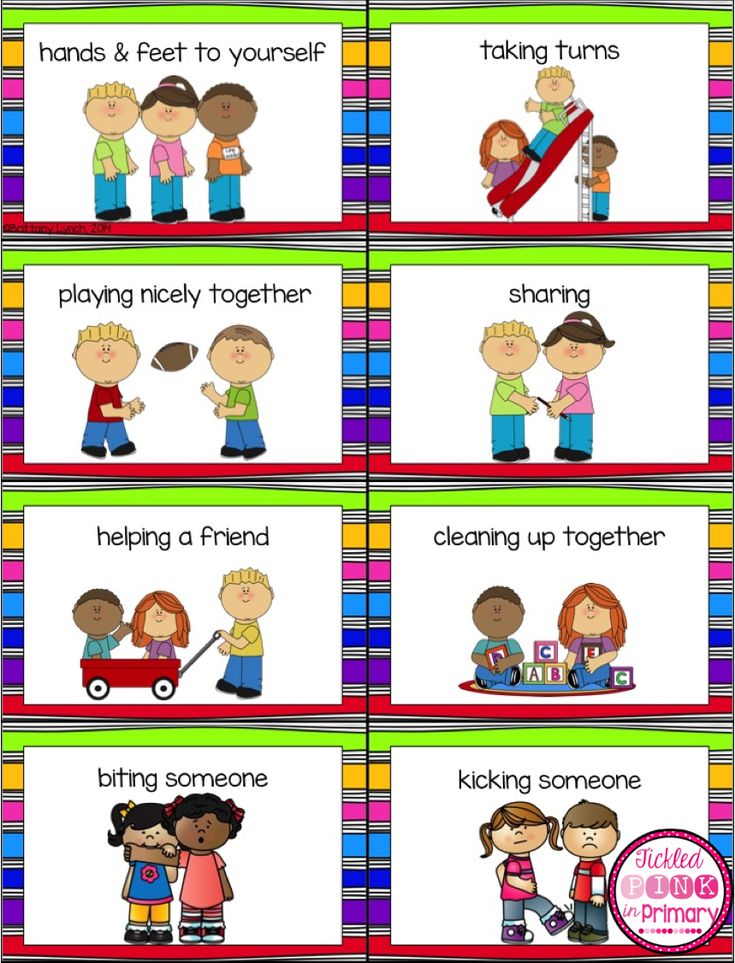

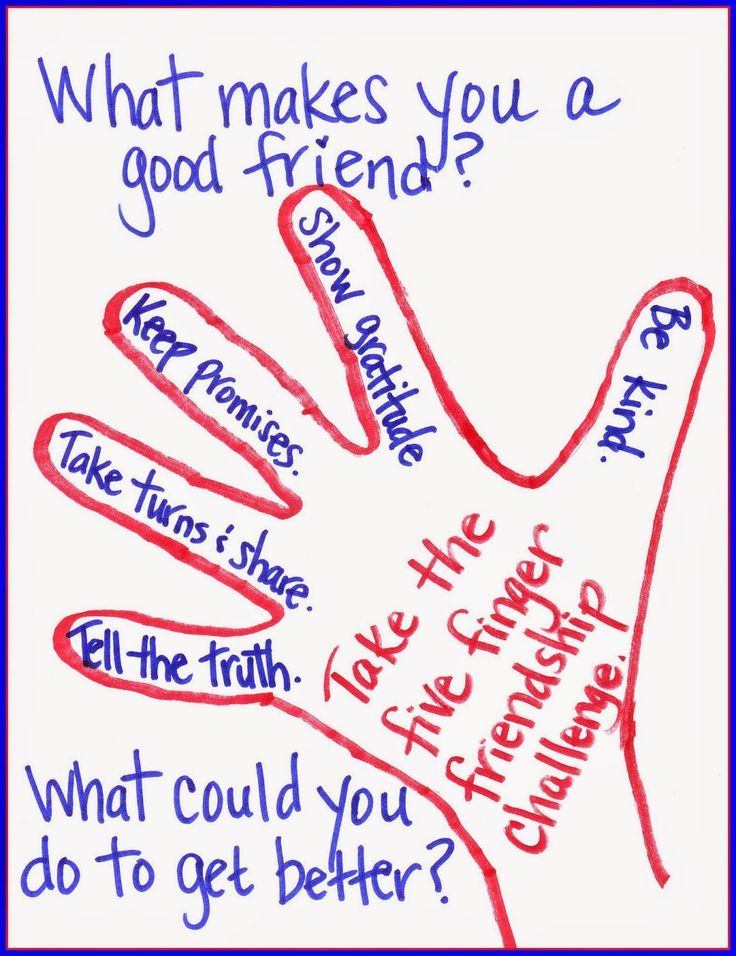

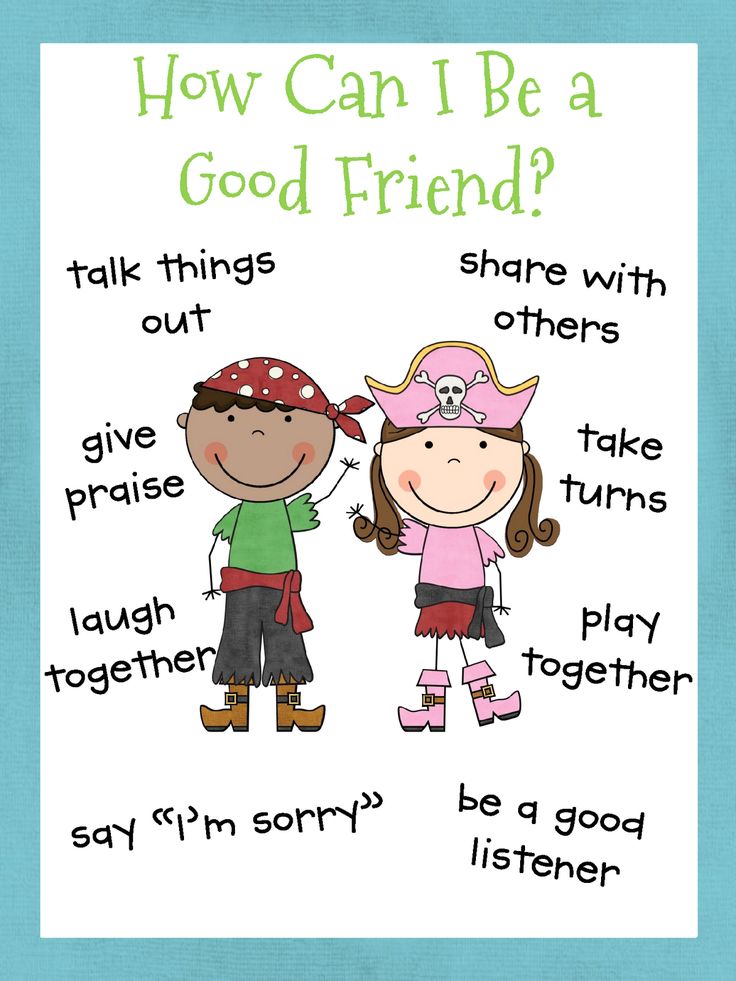

And just about every child will benefit from coaching and practice in the social arts. All around the world, successful friendship depends on the same, fundamental skills. To be successful, kids must

- regulate their own, negative emotions;

- understand other people’s emotions and perspectives;

- show sympathy, and offer help to friends in need;

- feel secure and trusting of other people;

- know how to handle introductions, and participate in conversation;

- be capable of cooperation, negotiation, and compromise;

- know how to apologize, and make amends; and

- be understanding (and forgiving) of other people’s mistakes.

It’s a long list, and honing these skills requires experience, effort, practice.

But that’s precisely why parents and teachers can be helpful. Making friends isn’t a magic trick. It’s something we learn. Something we can help our children learn.

So here is an evidence-based guide — 12 concrete ways that we can help kids make friends.

1. Show your child warmth and respect. Don’t try to control your child through threats, punishments, or emotional “blackmail.”

It might not seem of immediate relevance to your child’s ability to make friends. But the way parents treat children has an impact on their emotional development and social behavior. And this, in turn, can affect their peer relationships.

For example, consider authoritarian parenting, an approach to care-giving that emphasizes absolute obedience, low levels of warmth, and an attempt to control behavior through threats, punishments, or shaming.

In research conducted throughout the world, authoritarian parenting has been linked with the development of behavior problems (Lansford et al 2018). And kids with behavior problems have more trouble making friends.

And kids with behavior problems have more trouble making friends.

It also appears that parental psychological control — the attempt to manipulate children through guilt trips, shaming, or the withdrawal of affection — sets children up for developing poor-quality friendships (e.g., Cook et al 2012).

By contrast, when parents show warmth, and use positive discipline strategies — reasoning with children, and discussing the reasons for rules — kids tend to become more prosocial over time.

They are more likely to treat others with kindness and sympathy (Pastorelli et al 2015).

They tend to be less aggressive, more self-reliant, and better-liked by peers (Brotman et al 2009; Sheehan and Watson 2008; Hastings et al 2007).

So how exactly can we enforce good behavior without resorting to threats and punishments? For help, see my article about “positive parenting.” And to learn more about the effects of different parenting styles, see this Parenting Science guide.

2. Be your child’s “emotion coach.”

All of us experience negative emotions and selfish impulses. Does it prevent us from maintaining good friendships? No. Not if we know how to keep these responses under control.

So children need to learn how to regulate their own emotions. And parents? We can either help them, or make things more difficult.

For example, in one study, researchers asked parents — the mothers of 5-year-olds — how they responded to their children’s negative emotions. Then the researchers tracked child outcomes over the course of several years. What happened?

Kids were more likely to develop strong self-regulation skills if they had grown up with a parent who talked with them — sympathetically and constructively — about how to cope with bad moods and difficult feelings (Blair et al 2013). And the stronger a child’s self-regulation skills, the more likely that child was to develop positive peer relationships as her or she got older.

On the flip side, studies suggest that kids develop weaker self-regulation skills when their parents react dismissively (“You’re just being silly!”) or punitively (“Go to your room!”) to their children’s negative emotions (Davidov and Grusec 1996; Denham 1997; Denham et al 1997; Denham 1989; Denham and Grout 1993; Eisenberg et al 1996).

So when kids get upset, it’s worth taking the time to understand their feelings, and to actively teach them how to handle these feelings in a healthy, constructive way. For tips, see my article, “Emotion coaching.”

3. Nurture your child’s ability to empathize and “read minds.”

Kids need to do more than control their own, negative emotions. They also need to understand the emotions and perspectives of others.

Aren’t these things supposed to come naturally? Maybe, but “naturally” doesn’t mean “automatically, without encouragement and support.” There are concrete things that parents and teachers can do to help kids develop their emotion-savvy.

For more information see my evidence-based for nurturing empathy, as well as these activities for boosting a child’s face-reading skills.

It’s hard for kids to make friends if they feel very anxious. But what can we do about it?

Sensitive, responsive parenting is especially important for socially-anxious children. They need to know that we’ll be there for them when they need us. And, as I note elsewhere, studies suggest that sensitive, responsive parenting helps kids develop the kind of secure attachment relationships that promote confidence and independence.

They need to know that we’ll be there for them when they need us. And, as I note elsewhere, studies suggest that sensitive, responsive parenting helps kids develop the kind of secure attachment relationships that promote confidence and independence.

But when kids are really struggling with anxiety, they need additional support.

They perceive the world to be especially threatening, and unless we address that, they’re likely to experience ongoing emotional problems — problems that can interfere with the development of social skills (Pearcy et al 2020), and make it very difficult for a child to make friends (Lessard and Juvonen 2018).

So if your child is suffering from high levels of anxiety, talk about your concerns with your pediatrician or school counselor. Child psychologists have developed effective treatments for clinical anxiety, including cognitive behavioral therapy, an approach designed to re-train your child’s misperceptions and overreactive emotional responses (Seligman and Ollendick 2011).

But it’s also important to keep in mind: Sometimes, the threats are very real.

For example, your child might attend a school where aggressive behavior problems are common. Your child might be aware of peers or neighbors who have suffered violence. Or maybe your child is being exposed to harassment, peer rejection, or bullying.

If that’s your child’s situation, it makes sense to do what you can to improve your child’s environment. This includes taking action to stop violence, harassment, and bullying. But it may also include finding your child a new social outlet — like a club or playgroup — that is especially welcoming and secure.

5. Address your child’s aggressive or disruptive behavior problems.

As I mentioned above, such behavior problems can pose a major social barrier to making friends. Kids tend to avoid or shun peers who act out in aggressive ways.

What should you do if your child has trouble with disruptive outbursts or aggressive behavior?

For advice about coping as a parent, see my article, “Taming aggression in children: 5 crucial strategies for effective parenting. ”

”

In addition, see my article, “Disruptive behavior problems: 12 evidence-based tips for handling aggression, defiance, and acting out.”

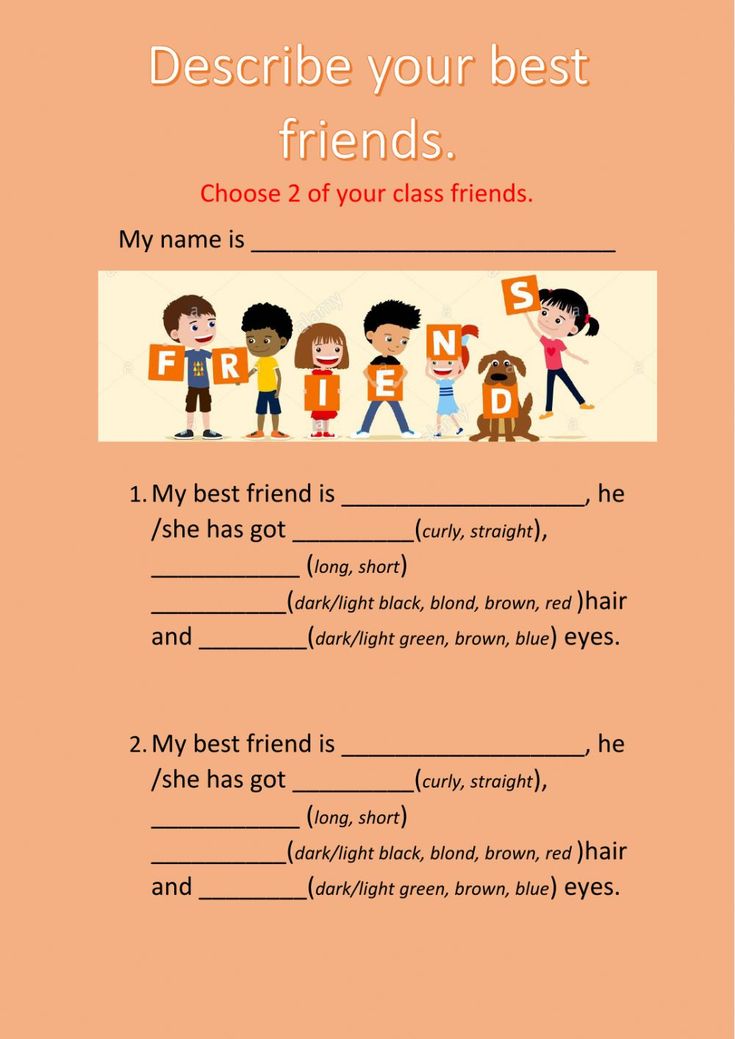

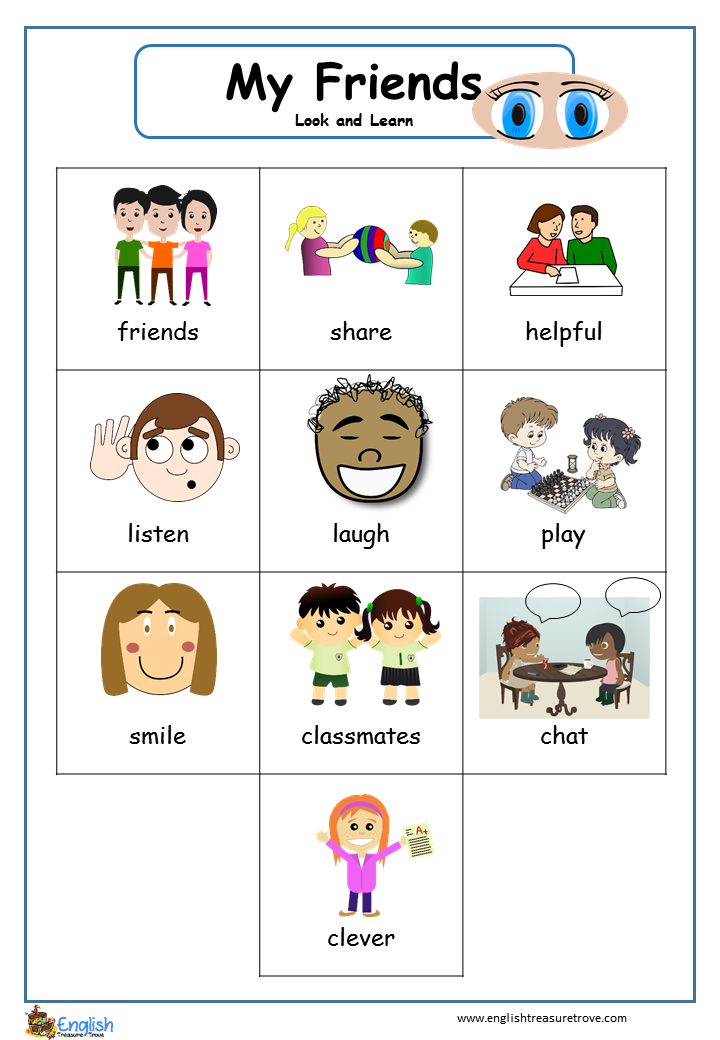

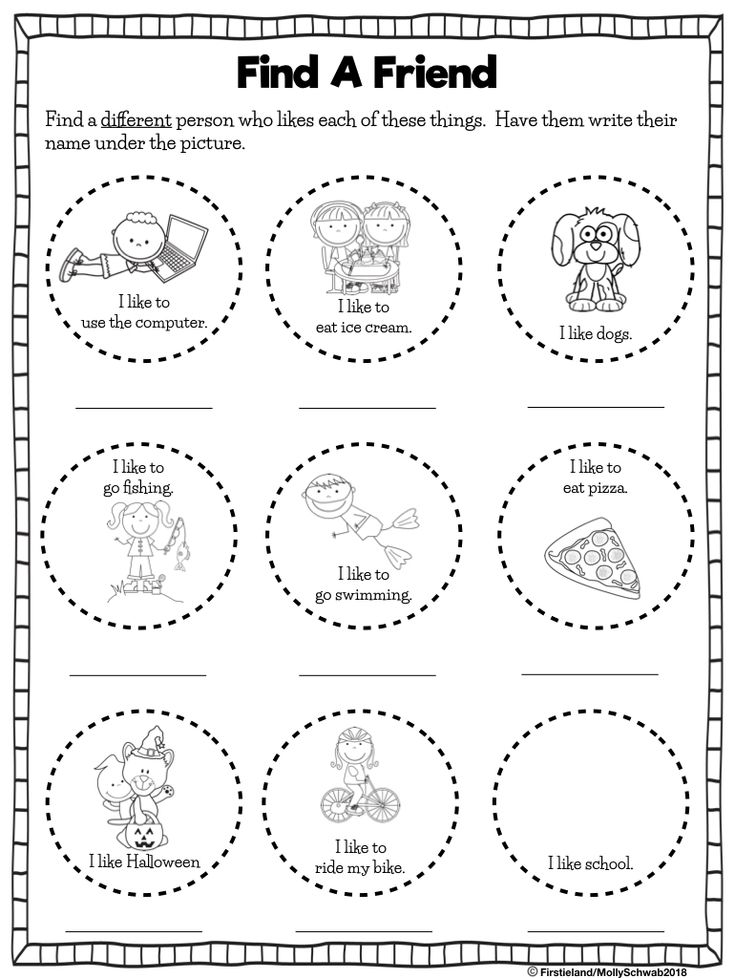

6. Teach your child these crucial conversation skills.

To make new friends, kids need to learn how to introduce themselves to others, and think of appropriate things to say.

They also need to learn how to listen well. And they need to learn how to provide conversational feedback — to show that they understand what another person is expressing.

How do we foster these skills?

We can help by modeling good communication skills at home, and engaging our kids in pleasant, reciprocal conversations (Feldman et al 2013).

In addition, we can help by actively teaching kids what to do and say.

For instance, kids benefit when we teach them the art of “active listening.”

That’s when a person makes it clear that he or she is paying attention — by making appropriate eye contact, orienting the body in the direction of the speaker, remaining quiet, and making relevant verbal responses (Bierman 1986).

And according to psychologists Fred Frankel and Robert Myatt (2003), we can train kids to become better conversationalists by offering them these concrete tips:

- When starting a conversation with someone new, trade information about your “likes” and “dislikes.”

- Don’t be an interviewer. Don’t merely ask questions. Offer information about yourself.

- Don’t be a conversation hog. When engaged in conversation, only answer the question at hand. When you’re done, give your partner the chance to talk.

Does your child need more opportunities to practice? Try a phone call, or an online video chat.

Studies suggest that kids get along better when they are engaged in cooperative activities — activities in which kids work toward a common goal (Roseth et al 2008). This is true in the classroom, and it’s also true when children play (Gelb and Jacobson 1988).

So if children are struggling socially, it’s probably a good idea to steer them away from competitive games, at least until they develop better social skills (Frankel and Myatt 2002).

And Fred Frankel and Robert Myatt offer this additional advice: If your child has a play date, remove toys and games that might spark conflict. For example, they recommend that parents put away toy weapons, as well as any items that could provoke competition or envy. If your child has a prized possession that he or she can’t bear to share, it’s best to hide it until the play date is over.

Want to learn more about the benefits of cooperative play? See this Parenting Science article.

And for a list of specific social activities to try, see my page, “Social skills activities for children and teens.”

To see what I mean, let’s get really specific.

Suppose a child, Sophie, sees several kids playing together. Sophie wants to join them, but she doesn’t know how. What should she do?

Victoria Finnie and Alan Russell presented the mothers of preschool children with this hypothetical scenario, asking them to weigh in (Finnie and Russell 1988). And interestingly, the mothers who came up with the best advice were also the mothers whose children demonstrated the best social skills.

What did these sage mothers say?

- Before making your approach, watch what the other kids are doing. What can you do to fit in?

- Try joining the game by doing something relevant. For example, if kids are playing a restaurant game, see if you can become a new customer.

- Don’t be disruptive or critical or try to change the game.

- If the other kids don’t want you to join in, don’t try to force it. Just back off and find something else to do.

It’s good advice we can pass along to our own kids. And we shouldn’t miss the bigger message from this study: Children benefit when we help them come up with concrete strategies for dealing with awkward social situations.

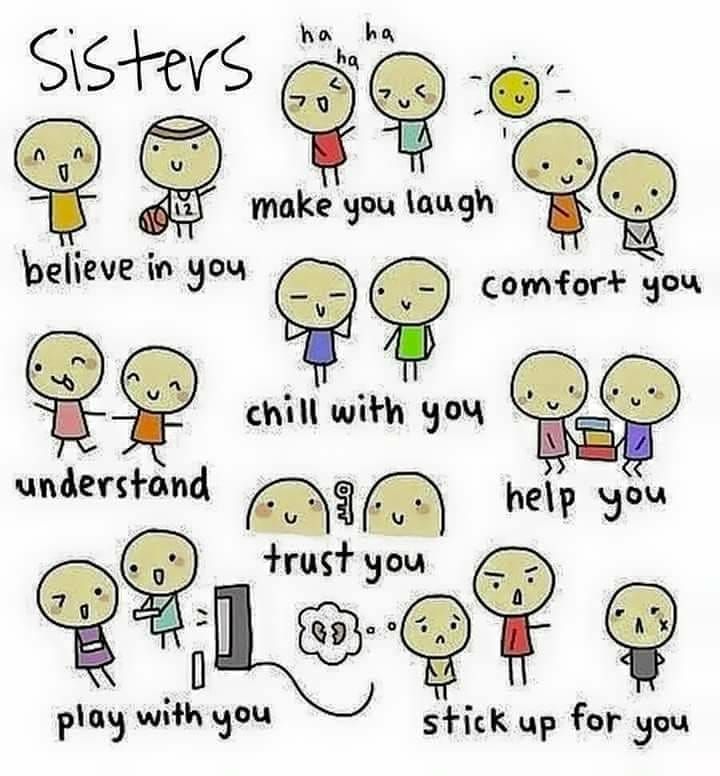

9. Help kids learn the art of compromise and negotiation.

To build positive relationships with peers, kids need to be able to think of peaceful ways to resolve conflicts. They need to be able to understand what other people need and want; they must be capable of anticipating the consequences of various actions.

Kids who grow up with siblings have a built-in advantage for developing these skills. They get lots of opportunities to practice the art of negotiation.

But you don’t have to have siblings to learn good social skills, and all kids — regardless of their family composition — benefit from a little guidance and instruction. Studies suggest that kids can hone their skills through role-playing exercises and activities that ask them to come up with solutions to hypothetical social clashes (Shure and Spivak 1980; Shure and Spivak 1982; Vestal and Jones 2004; Boyle D and Hassett-Walker 2008.).

So it seems a good bet that we can help children become better social problem-solvers by actively walking them through the process. The next time your child butts heads with someone else, consider it learning opportunity. Help your child think of a solution that will be acceptable to both sides.

10. Teach your child how to express remorse and make amends.

It happens to everyone. We mess up. We make a bad judgment. We cause harm or bad feelings.

We mess up. We make a bad judgment. We cause harm or bad feelings.

What happens next? If we are shamed or “cancelled” for our mistakes, we tend to focus on our own negative emotions. We may feel humiliation, resentment, and even anger. And that doesn’t help us repair our social relationships. Far from it.

By contrast, consider what happens if we feel a sense of guilt. Feeling guilty can be constructive. We reflect on how our actions have affected others. We empathize with our victims. And it inspires us to try to repair the damage we’ve caused.

The difference is crucial for making and keeping friends.

Studies confirm that children — even children as young as 4 years — are more likely to forgive a peer for wrongdoing if that peer actively apologizes. And as children get a bit older (and more sophisticated), they pay attention to signs that the perpetrator is remorseful. In fact, they don’t always require an explicit apology — not if they observe signs of remorse (Oostenbroek and Vaish 2019).

But what’s the most effective way to repair a relationship? Don’t just apologize, or act remorseful. Make amends.

In an experiment on 6- and 7-year-olds, researchers observed how children responded to a transgressor who knocked down a tower they’d been building. Kids were forgiving if the transgressor apologized, but they still felt upset. The only thing that made these kids feel better was if the transgressor actively helped them re-build their tower (Drell and Jaswal 2015).

So that’s what we should aim for — teaching our kids how to repair relationships and improve bad feelings. From an early age, we should coach them on how to deliver apologies, and how to make amends for their mistakes.

11. Encourage your child to be understanding, and forgiving of other people’s mistakes.

Kids can be forgiving, but it doesn’t always come naturally. In fact, some children have an ongoing problem with vindictiveness. They tend to assume that other people are hostile, and they may brood about perceived slights and insults.

If that’s your child’s problem, you’ll want to help change his or her perceptions of other people. Help your child consider a transgressor’s point of view, and ask your child to think of alternative explanations for problematic behavior.

Maybe it was a careless accident. Maybe the transgressor was stressed-out about something, or feeling tired or ill. Maybe the transgressor was simply having a bad day, and you happened to get in his way.

When adults ask kids to think about such alternative explanations, kids are more likely to give perpetrators the benefit of the doubt (Van Djik et al 2019).

Of course, not every child needs such prodding. Some kids are too indulgent towards wrong-doers. They blame themselves when they get victimized, and remain in relationships that leave them perpetually exploited or mistreated (Luchies et al 2010).

So we need to be mindful of the situation, and give each child the type of support he or she needs.

Studies in a variety of cultures suggest that children are better off when their parents stay informed about their social activities (Parke et al 2002).

Called “parental monitoring,” this includes doing things like

- supervising where young children play;

- helping children find opportunities to meet and socialize with friendly, prosocial peers;

- talking to your children’s friends when they come to visit, and

- asking your kids to tell you about things they’ve done in their free time.

There’s also evidence in favor of setting certain limits, like insisting that your adolescent tell you in advance about the details of an evening out.

Who will you be hanging out with? What will you be doing? Where will you go?

But parents need to tread carefully. They can embarrass their children — and scare off potential friends — by becoming too intrusive.

And if kids perceive us to be too controlling, they are more likely to reject our guidance. In fact, in one study, adolescents actually became more likely to choose a delinquent peer as a friend if they thought their parents were overplaying their authority (Tilton-Weaver et al 2013).

So it’s important to give your child a sense of autonomy, and communicate your concerns in a way that seems reasonable and respectful. Otherwise your child may come to view your authority as illegitimate, and behave accordingly.

For more information, see my article, “Why kids rebel: What children believe about the legitimacy of adult authority.”

References: How to help kids make friends

Beirman KL. 1986. Process of change during social skills training with preadolescents and its relation to treatment outcome. Child Dev 57(1): 230-240.

Blair BL, Perry NB, O’Brien M, Calkins SD, Keane SP, and Shanahan L. 2013. The Indirect Effects of Maternal Emotion Socialization on Friendship Quality in Middle Childhood. Dev Psychol. 2013 Jun 24. [Epub ahead of print]

Brotman LM, O’Neal CR, Huang KY, Gouley KK, Rosenfelt A, and Shrout PE. 2009. An experimental test of parenting practices as a mediator of early childhood physical aggression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 50(3):235-45.

50(3):235-45.

Chen X and Rubin KH 1994. Family conditions, parental acceptance, and social competence and aggression in Chinese children. Social Development 3: 269-290.

Cook EC and Fletcher AC. 2012. A Process Model of Parenting and Adolescents’ Friendship Competence. Soc Dev. 21(3):461-481.

Davidov M and Grusec JE. 2006. Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Dev. 77(1):44-58.

Dekovic M and Gerris JRM. 1994. Developmental analysis of social cognitive and behavioral differences between popular and rejected children. Journal of applied developmental psychology. 15(3): 367-386.

Denham SA. 1997. “When I have a bad dream, my Mommy holds me”: Preschoolers conceptions of emotions, parental socialization, and emotional competence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 20: 301-319.

Denham, SA, Mitchell-Copeland J, Strandberg K, Auerbach S and Blair K. 1997. Parental contributions to preschoolers’ emotional competence: Direct and indirect effects. Motivation and Emotion 21:65–86.

Motivation and Emotion 21:65–86.

Denham SA 1989. Maternal affect and toddlers social-emotional competence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59: 368-376. Denham SA and Grout L. 1993. Socialization of emotion: Pathway to preschoolers affect regulation. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 17: 215-227.

Drell MB and Jaswal VK. 2015. Making Amends: Children’s Expectations about and Responses to Apologies. Social Development 25(4): 742-758.

Elicker J, Englund M and Sroufe LA 1992. Predicting peer competence and peer relationships in childhood from early parent-child relationships. In RD Parke and GW Ladd (eds), Family-Peer Relationships: Modes of Linkage. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. 1996. Parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: relations to children’s social competence and comforting behavior. Child Dev. 67(5):2227-47.

Feldman R, Bamberger E, and Kanat-Maymon Y. 2013. Parent-specific reciprocity from infancy to adolescence shapes children’s social competence and dialogical skills. Attach Hum Dev. 2013;15(4):407-23.

Attach Hum Dev. 2013;15(4):407-23.

Finnie V and Russell A. 1998. Preschool children’s social status and their mothers’ behavior and knowledge in the supervisory role. Developmental Psychology 24: 789-801.

Frankel FF and Myatt R. 2002. Children’s friendship training. Routledge.

Gelb R and Jacobson JL. 1988. Popular and unpopular children’s interactions during cooperative and competitive peer group activities. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 16(3):247-61.

Granot D and Mayseless O. 2001. Attachment security and adjustment to school in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 25:530–541.

Hastings PD, McShane KE, Parker R, Ladha F. 2007. Ready to make nice: parental socialization of young sons’ and daughters’ prosocial behaviors with peers. J Genet Psychol. 168(2):177-200.

Heyman GD, Fu G, and Lee K. 2008. Reasoning about the disclosure of success and failure to friends among children in the United States and China. Dev Psychol 44: 908-918.

Dev Psychol 44: 908-918.

Ladd GW and Golter B. 1988. Parents’ management of preschoolers’ peer relations: Is it related to children’s social competence? Developmental Psychology 24: 109-117.

Lansford JE, Godwin J, Bornstein MH, Chang L, Deater-Deckard K, Di Giunta L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Pastorelli C, Skinner AT, Sorbring E, Steinberg L, Tapanya S, Uribe Tirado LM, Alampay LP, Al-Hassan SM, Bacchini D. 2018. Parenting, culture, and the development of externalizing behaviors from age 7 to 14 in nine countries. Dev Psychopathol. 30(5):1937-1958.

Lessard LM and Juvonen J. 2018. Friendless Adolescents: Do Perceptions of Social Threat Account for Their Internalizing Difficulties and Continued Friendlessness? J Res Adolesc. 28(2):277-283.

Mrug S, Hoza B, and Bukowski WM. 2004. Choosing or being chosen by aggressive-disruptive peers: do they contribute to children’s externalizing and internalizing problems? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 32(1):53-65.

Oostenbroek J and Vaish A. 2019. The Emergence of Forgiveness in Young Children. Child Dev. 90(6):1969-1986.

2019. The Emergence of Forgiveness in Young Children. Child Dev. 90(6):1969-1986.

Pastorelli C, Lansford JE, Luengo Kanacri BP, Malone PS, Di Giunta L, Bacchini D, Bombi AS, Zelli A, Miranda MC, Bornstein MH, Tapanya S, Uribe Tirado LM, Alampay LP, Al-Hassan SM, Chang L, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Oburu P, Skinner AT, Sorbring E. 2016. Positive parenting and children’s prosocial behavior in eight countries. J. Child Psychol Psychiatry. 57(7):824-34.

Pearcey S, Gordon K, Chakrabarti B, Dodd H, Halldorsson B, Creswell C. 2020. Research Review: The relationship between social anxiety and social cognition in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13310. Online ahead of print.

Rose AJ and Asher SR. 2004. Children’s strategies and goals in response to help-giving and help-seeking tasks within a friendship. Child Dev 75(3): 749-763.

Seligman LD, Ollendick TH. 2011. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 20(2):217-38

Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 20(2):217-38

Sheehan MJ and Watson MW. 2008. Reciprocal influences between maternal discipline techniques and aggression in children and adolescents. Aggress Behav. 34(3):245-55.

Simons KJ, Paternite CE, and Shore C. 2001. Quality of parent/adolescent attachment and aggression in young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 21:182–203.

Tilton-Weaver LC, Burk WJ, Kerr M, Stattin H. 2013. Can parental monitoring and peer management reduce the selection or influence of delinquent peers? Testing the question using a dynamic social network approach. Dev Psychol. 49(11):2057-70.

van Dijk A, Thomaes S, Poorthuis AMG, Orobio de Castro B. 2019. Can Self-Persuasion Reduce Hostile Attribution Bias in Young Children? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 47(6):989-1000.

Vestal A and Jones N. 2004. Peace Building and Conflict Resolution in Preschool Children June 2004Journal of Research in Childhood Education 19(2):131-142

Whiting JWM and Whiting BB. 1973. Altruistic and egoistic behavior of children in six cultures. In: RA Levine and RS New (eds) Anthropology and Child Development: A cross-cultural reader. Blackwell.

1973. Altruistic and egoistic behavior of children in six cultures. In: RA Levine and RS New (eds) Anthropology and Child Development: A cross-cultural reader. Blackwell.

Xu Y, Farver JA, and Zhang Z. 2009. Temperament, harsh and indulgent parenting, and Chinese children’s proactive and reactive aggression. Child Dev. 80(1):244-58.

Content of “How to help kids make friends” last modified 10/ 2020

Image credits for “How to help kids make friends”

title image of two girls talking by wooden fence by YakobchukOlena / istock

image of mother and boy with seagulls by anurakpong /istock

image of father talking with girl on sofa by fizkes /istock

image of little girl looking at injured boy by Tsomka / shutterstock

image of pensive, anxious little girl by Ami Parikh / shutterstock

image of boy in conversation online by StockRocket / istock

image of girls holding hands in circle outdoors by Rawpixel.com / shutterstock

image of little girl feeling left out while other kids talk / ilona75 /istock

image of father reasoning with boy and girl on the grass by imtmphoto /istock

How to teach a child to make friends and keep friendships - Knife

Friends in preschool institutions usually appear due to geographical proximity, at the initiative of parents or by accident. A friend is a child living in the neighborhood, the son or daughter of your girlfriend, if they are close in age, a relative or just a child who was on the playground at the same time as you.

A friend is a child living in the neighborhood, the son or daughter of your girlfriend, if they are close in age, a relative or just a child who was on the playground at the same time as you.

Making friends is pretty easy: "Do you want to play?" Some of them last for a long time, but most are forgotten, and children practically do not regret them. nine0003

These first friendships are a training ground for cooperation and communication, because anyone who has watched a three-year-old hit her “friend” on the head with a scoop, push him out of line up a slide, or stuff a favorite toy down his pants knows what preschoolers are up to. there is a long way to go before they learn how to build the kind, mutually supportive relationship we usually call friendship.

This is a necessary initial stage, because when they come to school, children embark on one of the most important missions not only of middle childhood, but of all life - they learn to build and maintain relationships.

nine0010

nine0010 Older children spend less than half of their waking hours at school, and most of the remaining hours are devoted to developing the personal qualities and social skills needed to become an interesting, reliable, loyal, and helpful friend.

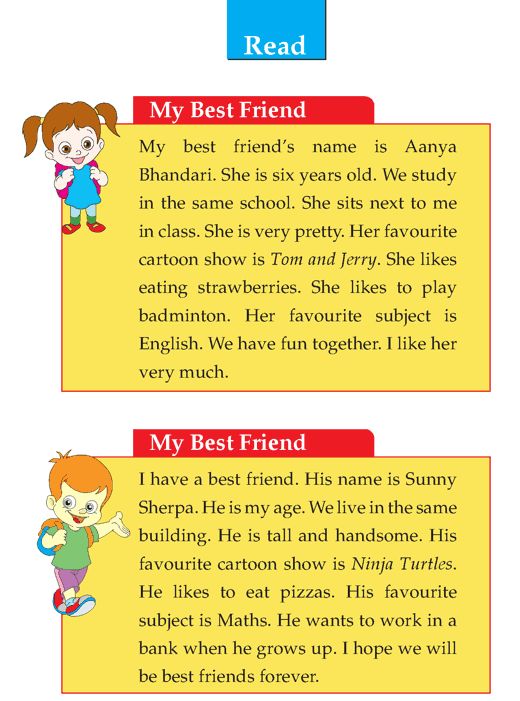

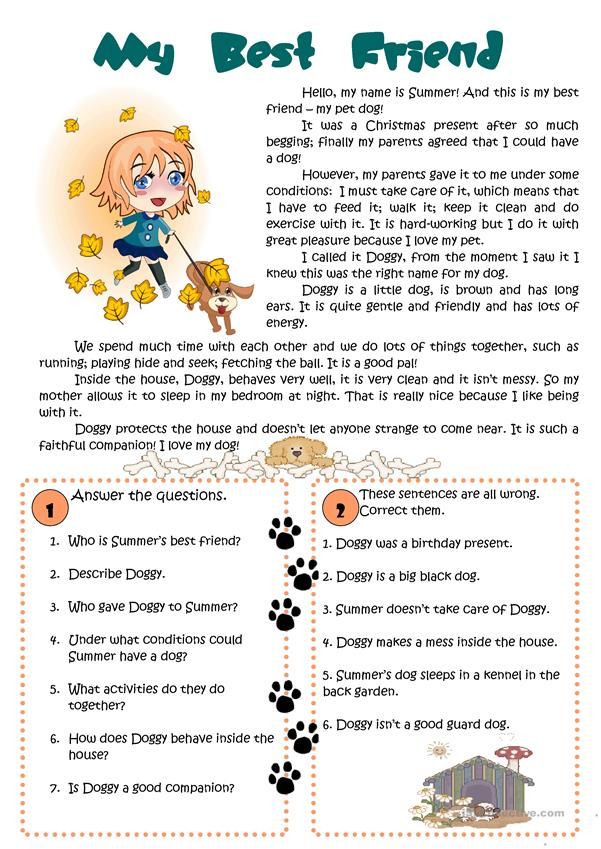

When girls of this age are asked why they chose a particular friend, many answer: "She really understands me." Take a look at how complex the situation is, reflected in a seemingly ordinary dialogue between two ten-year-old girls. nine0003

Stella: I have handwriting problems and the kids in class tease me about it.

Elena: I heard what they were saying. I think they behaved very badly. I know what you feel. I have spelling problems and my parents want me to improve it.

Stella: Could you help me? I hate being teased and I know that you have very good handwriting.

Elena: Of course. Do you want to do it at recess?

Stella: Thank you. It would be great. You are a real friend! nine0003

Elena: LP?

Stella: LP!

Here we observe the development of emotional intelligence - the ability to recognize emotions, understand them and manage them.

Young children simply have emotions; Stella and Elena use them to solve a problem and strengthen their friendship.

Young children simply have emotions; Stella and Elena use them to solve a problem and strengthen their friendship. Stella is aware of and can express her inner state (disorder) incomparably better than a small child with his limited set of ways to express this emotion: whining, detachment or hysteria. In addition, she is perceptive enough to figure out which of her friends to turn to for help in dealing with her feelings. nine0003

Elena's concern about her parents' reaction shows that she knows how others feel. She is able to empathize with her friend and take her problem to heart. Elena kindly offers her time and skills because she knows that Stella has the opportunity to return the favor. In part, our children develop a sense of self by looking at what the world reflects for them as in a mirror.

Stella and Elena end the dialogue with the abbreviation LP, a kind of cipher that seals their closeness. The depth of feelings between these girls is palpable, they really "understand" each other, and as a result, Stella's mood improves significantly. nine0003

nine0003

Girls' friendships are characterized by emotional openness and responsiveness, but boys' friendships are typically characterized by physical contact. They push, grab each other, fight each other and often act like cubs to each other.

Boys and girls have strict rules about reconciliation with the enemy and almost no mixed games. It is not clear which gender children have more taboos, but it is obvious that boys consider girls incomprehensible and dangerous, and vice versa.

This moratorium seems to help both boys and girls to form their identities without unnecessary confusion, since they are surrounded almost exclusively by children of the same sex. nine0003

Although boys and girls in primary school often have very different ways of communicating, they all gravitate towards those who are like them. Able students tend to team up with the same, as well as athletic, socially developed, or children with special interests (for example, music, outdoor games, video games).

Unites children and ethnicity. This is a period of time when everyone who is "like me" is much more attractive than those who are "not like me". At this age, it is quite difficult to figure out who you are without taking into account the character traits that have yet to manifest. nine0010

We may wish our children had more social circles or interests, but it's best to offer them something new, not force them. Give them time to gradually explore the different sides of their personality.

Typical parental friendship questions in elementary school

“My ten-year-old daughter spends all her time with one friend. She is, of course, a wonderful girl, but they are simply inseparable. They spend every free minute together and spend the night at each other's house on weekends. I worry that she is missing out on learning how to communicate with a wider group of kids. Should I be worried?" nine0003

Probably not. A period of intense relationship with one friend is common. Some children are naturally very sociable. Others are quite content with one or two friends, and if you don't see other symptoms like depression or social anxiety, then you don't need to worry about this type of relationship. Such friendships with a compatible child provide support and many wonderful moments. Sometimes they last a lifetime.

Some children are naturally very sociable. Others are quite content with one or two friends, and if you don't see other symptoms like depression or social anxiety, then you don't need to worry about this type of relationship. Such friendships with a compatible child provide support and many wonderful moments. Sometimes they last a lifetime.

“My nine-year-old son is extremely shy. He has several friends, but only because they initiated the communication themselves. It seems to me that he never made friends with anyone on his own initiative. What can I do to help him become more sociable?” nine0003

Shyness is largely a consequence of temperament. Some children are just "rocking slowly". They rarely, if ever, show any initiative and behave reservedly in new social situations until they relax a little.

For a sociable parent, this can be especially hard to see. However, if your son's shyness doesn't hurt him, it's probably you who needs to adjust to such a shy child. Since you say that he has friends, there is hardly any cause for concern. nine0003

Since you say that he has friends, there is hardly any cause for concern. nine0003

Shy children need to be very carefully guided in new situations. It may be helpful for your son if you talk about a new situation (say, an upcoming birthday party) or rehearse what he might say to another child at a party.

See also

Generation Alpha: why millennial kids will destroy gender, save the planet, master the five professions and live to be 100 years old

What is "painful intimacy" and how children and parents can stop being a burden to each other

“My eight year old daughter has no friends. At all. She spends all her free time alone and says that she is sad and no one loves her. I try to invite other girls home, but they rarely accept the invitation, and if they do, they often want to leave early. Help!"

A child without friends is cause for concern. Have you observed your daughter enough in social situations to understand what might be causing her problem? It's best to do this discreetly and unobtrusively when it's your turn to take the kids home or accompany them on field trips. nine0003

nine0003

You need to know if the children refuse to communicate with your child because he messes up or acts aggressively, or if he is ignored because he does not "fit in" and does not have social skills that other children may be interested in.

Some children are slow to grasp social nuances and assimilate accepted norms. They stand too close, talk too loudly, or interrupt others.

You should probably talk to the girl's teachers or a psychologist, as they have many opportunities to observe children in different social situations. Another good source of information is adults accompanying children to playgrounds. nine0003

Once you have a better understanding of why your daughter has so many communication difficulties, you can begin to discuss her role in the problem. She is already uncomfortable, so you should be careful and tune in to cooperation.

The next time she says "No one loves me", you can ask her what she thinks she could do differently. If she doesn't know, suggest one or two options yourself.

There are social skills development groups for children who have trouble reading social cues. If you find one in your area, it can be very useful. nine0010

When a child is constantly sad and isolated from other children, a consultation with a pediatrician and a referral to a child psychologist is necessary.

“My eleven year old son has many friends. But you should have seen them. Frankly, they all look like juvenile delinquents. Pants are lowered, hair is tousled, and speech consists mainly of swearing, sometimes obscene. My son has always been a good boy, and I have no idea why he suddenly found himself in this company of losers. nine0003

I'm afraid his prettier friends won't want to hang out with him. How can I make him understand that these children will give him nothing but trouble? Should I just forbid him to communicate with them?"

Prohibiting friendship with these boys can backfire. You do not have the opportunity to impose your will, since he spends most of the day at school, away from you.

You don't have to like your son's friends, and you can let him know if you are specific about what's bothering you. “You know that they don’t swear in our house. Please ask your friends to follow the rules. Otherwise, they will be asked to leave.” A couple of bad words, if they hang out in your son's room, are best left unnoticed. nine0003

Please note that the problem here may not be as serious as it seems at first glance. In boys at this age, the prepubertal period begins. Experimenting with different styles of clothing is quite typical.

If your son feels that you are categorical and do not support him, he will stop talking to you (as far as eleven-year-old boys can talk). Try to ignore the droopy pants and long locks - there's a reason your son likes these guys. nine0003

Interesting to know why. Things that seem disturbing to us—weird hairstyles, wild clothing styles, provocative behavior—may be especially attractive to those children who have always done everything right.

Of course, you do not need to put up with bad behavior, but the right to exercise authority should be reserved for situations that you consider dangerous for the child or that seriously threaten family values.

You need to figure out something more important than the length of your hair or the way you wear pants: Are your son's new friends really showing deviant behavior? nine0010

Talking to a school psychologist can often shed light on whether they are skipping school or experimenting with drugs. The danger of troubled friends is that they can "teach" a child deviant behavior.

If they have similar problems, then you need to have a clearer idea of what is happening with your son. Maybe something is wrong in your house? Are you getting a divorce? Is there a family conflict? Was a brother or sister born? It is sometimes easier for a dad to find out what is happening from a teenager through joint activities, and not through "conversations" that mothers love so much. nine0003

nine0003

Discuss your concerns with other adults who know your child well: their teacher, another parent, perhaps your pediatrician. If you still feel there is cause for concern, consult with a child or adolescent psychologist.

Maybe interesting

How to whine properly, if you don't want to lose your friends

Why is it harder for us to make friends?

How parents can help

Some mothers experience a sense of loss because their child is away from home most of the day and increasingly turns to peers for support and comfort. Secrets once known only by the two of you are now shared with others, and you are restricted from accessing your child's inner life, especially towards the end of elementary school.

For other mothers, this is a welcome change, allowing them to spend more time with their other children, career, husband, or themselves. Most of us have mixed feelings. nine0003

We worry about the distance that lies ahead of us, and at the same time actively participate in the child's growing desire to explore the world around us and be active. New schedules, clubs and teams, parties and overnight guests appear in life.

New schedules, clubs and teams, parties and overnight guests appear in life.

As we turn over part of a child's life to new people and friends, we want to make sure they have the skills they need to build healthy, responsible, and satisfying friendships.

Do you remember your first friendships? Are you still in touch with any of those friends? Do you remember moments of intimacy in this relationship more or quarrels? How you feel about friendship, how you look at photos, what stories you tell, affects your child's view of friendship. nine0003

Share good stories with your children. Let them also know that friendship involves cooperation, but sometimes entails disappointment.

Remember that the rules, expectations, and behaviors that you approved of when your child was young are learned and will serve as a template for how he treats friendships now and in the future. This is where our values become part of the child's perception.

Listen to the nine-year-old daughter of one of my colleagues:

“Making friends is very interesting.

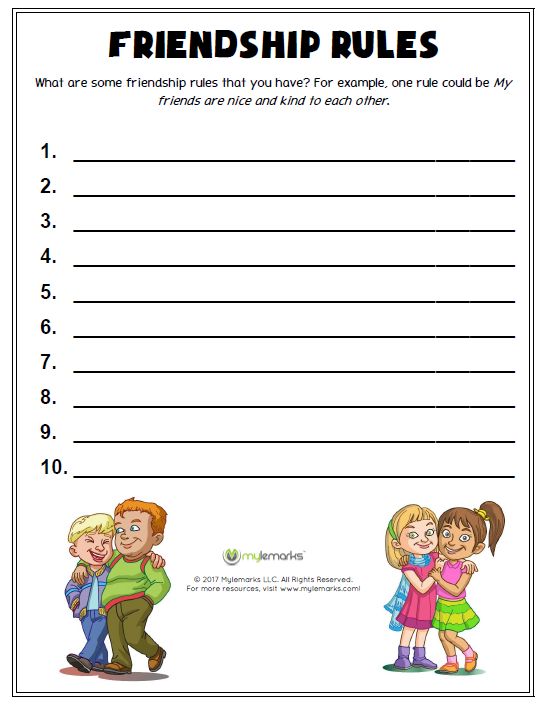

It's easy to make friends if you say "Hello!" Friends shouldn't be talking about a friend behind their back. This means that you should not talk about someone if he is not with you. Don't say things like "you're a fool". And you should always smile when you introduce yourself. This is rule number one. And you also need to behave correctly - even when you are angry. And never yell at your friend. If you're angry, it's better to go to your mother."

We can practically hear this girl's mother somewhere in the background telling her to be friendly, not to be rude and ask for help when something goes wrong. This is a great example of the process of learning values, I could not have come up with better. nine0003

This is how children are socialized. They have a warm relationship with their parents, who support them and demonstrate that they can be freely turned to for advice. “Be polite. Hello. Do not shout". These are the main rules of friendship, but they don't do much when it comes to new social skills in young children. They still have a lot to learn.

They still have a lot to learn.

Here are some additional points to keep in mind.

- Scientists have found that parents who use the reflective method have better socially adapted children. This means that they encourage the child to think about how his actions affect other people and himself. When such parents conduct an educational conversation, they ask the child to think about how his actions are perceived by others. "When you didn't thank your grandmother for the gift, how do you think she felt?" While calming the child, they try to get him to express his feelings. Children who are brought up in this spirit are more likely to be chosen as friends and less likely to be rejected. nine0180

- If the father is actively involved in the upbringing of the child, this is the most powerful factor in developing the child's attention to others; this participation should ideally begin when children enter primary school. The transition from kindergarten to primary school is very important for children.

Dads, who often play a leading role in demonstrating the fascination of the outside world, "oil the wheels", make the process easier. This effect is equally noticeable in both girls and boys. Those children for whom this transition is easier, have more strength to communicate with other children and empathize. Anyone would be happy to have such friends. nine0180 - Do not underestimate the complexity of social interaction from the perspective of children. What seems like nonsense to an adult can be frightening for an insecure or shy child. Simply entering a new class means deciding where to sit, how to get to know other children, and figure out the social hierarchy. Do not underestimate or oversimplify difficulties. “Oh, this is funny. You’ll just move to the next class.” To a child, this may seem like a very difficult situation.

- Help him find in himself what he is good at. A musical child who feels left out in school would benefit from extracurricular activities related to music, where he will meet other children who are passionate about the same, and gain confidence through the recognition of his abilities.

nine0180

nine0180 - Remember that your family life is a training ground for developing a child's understanding of how people should treat each other. Families with warm, responsive relationships and mutual support raise children who know how to show warmth, responsiveness, and support.

- Families with an explosive, unpredictable atmosphere release into life children whose knowledge and experience do not contribute to friendly relations. Pay attention to how your family members talk to each other and interact. Seek help if you need it, especially if you are depressed. This state of mothers has a negative impact on many aspects of a child's life, including the ability to communicate. nine0180

How to teach a child to make friends and keep friendship. Tips for parents

Maria Kuramina

Child psychologist Madeline Levine's book The Most Valuable tells about what qualities a child really needs to develop in order for him to grow up to be a truly happy person. One of those skills is the ability to make friends and keep friendships. We share several tips from the book, as well as answers to popular questions from parents. nine0003

One of those skills is the ability to make friends and keep friendships. We share several tips from the book, as well as answers to popular questions from parents. nine0003

Learn how to make friends and keep friendships

Friends in pre-schools usually appear because of geographical proximity, at the initiative of parents or by chance. A friend is a child living in the neighborhood, the son or daughter of your girlfriend, if they are close in age, a relative or just a child who was on the playground at the same time as you. Making friends is pretty easy: “Do you want to play?” Some of them last for a long time, but most are forgotten, and children practically do not regret them. These first friendships are a training ground for cooperation and communication, because anyone who has watched a three-year-old bash her "friend" over the head with a dustpan, push her out of line up a slide, or stuff her favorite toy down her pants knows that preschoolers have a long way to go. way before they learn to build the kind, mutually supportive relationship we usually call friendship. This is a necessary initial stage, because, coming to school, children embark on one of the most important missions not only of middle childhood, but of all life - they learn to build and maintain relationships. nine0003

This is a necessary initial stage, because, coming to school, children embark on one of the most important missions not only of middle childhood, but of all life - they learn to build and maintain relationships. nine0003

Source

Common parental friendship questions in elementary school

“My ten-year-old daughter spends all her time with one friend. She is, of course, a wonderful girl, but they are simply inseparable. They spend every free minute together and spend the night at each other's house on weekends. I worry that she is missing out on learning how to communicate with a wider group of kids. Should I be worried?"

Probably not. A period of intense relationship with one friend is common. Some children are naturally very sociable. Others are quite content with one or two friends, and if you don't see other symptoms like depression or social anxiety, then you don't need to worry about this type of relationship. Such friendships with a compatible child provide support and many wonderful moments. Sometimes they last a lifetime. nine0003

Sometimes they last a lifetime. nine0003

“My nine-year-old son is extremely shy. He has several friends, but only because they initiated the communication themselves. It seems to me that he never made friends with anyone on his own initiative. What can I do to help him become more sociable?”

Shyness is largely a consequence of temperament. Some children are just "rocking slowly". They rarely, if ever, show any initiative and behave reservedly in new social situations until they relax a little. For an outgoing parent, this can be especially hard to see. However, if your son's shyness doesn't hurt him, it's probably you who needs to adjust to such a shy child. Since you say that he has friends, there is hardly any cause for concern. Shy children need to be very carefully guided in new situations. It may be helpful for your son if you talk about a new situation (say, an upcoming birthday party) or rehearse what he might say to another child at a party. nine0003

“My eight year old daughter has no friends. At all. She spends all her free time alone and says that she is sad and no one loves her. I try to invite other girls home, but they rarely accept the invitation, and if they do, they often want to leave early. Help!"

At all. She spends all her free time alone and says that she is sad and no one loves her. I try to invite other girls home, but they rarely accept the invitation, and if they do, they often want to leave early. Help!"

A child without friends is cause for concern. Have you observed your daughter enough in social situations to understand what might be causing her problem? It's best to do this discreetly and unobtrusively when it's your turn to take the kids home or accompany them on field trips. You need to know if the children refuse to communicate with your child because he spoils everything or behaves aggressively, or if he is ignored because he does not "fit in" and does not have social skills that other children may be interested in. Some children are slow to grasp social nuances and assimilate generally accepted norms. They stand too close, talk too loudly, or interrupt others. You should probably talk to the girl's teachers or a psychologist, as they have many opportunities to observe children in different social situations. Another good source of information is adults accompanying children to playgrounds. nine0003

Another good source of information is adults accompanying children to playgrounds. nine0003

Once you have a better understanding of why your daughter has so many communication difficulties, you can begin to discuss her role in the problem. She is already uncomfortable, so you should be careful and tune in to cooperation. The next time she says "No one loves me", you can ask what she thinks she could do differently. If she doesn't know, suggest one or two options yourself. There are social skills development groups for children who have trouble reading social cues. If you find one in your area, it can be very useful. When a child is constantly sad and isolated from other children, a consultation with a pediatrician and a referral to a child psychologist are necessary. nine0003

“My eleven year old son has many friends. But you should have seen them. Frankly, they all look like juvenile delinquents. Pants are lowered, hair is tousled, and speech consists mainly of swearing, sometimes obscene. My son has always been a good boy, and I have no idea why he suddenly found himself in this company of losers. I'm afraid that his more attractive friends will not want to communicate with him. How can I make him understand that these children will give him nothing but trouble? Should I just forbid him to communicate with them?" nine0080

My son has always been a good boy, and I have no idea why he suddenly found himself in this company of losers. I'm afraid that his more attractive friends will not want to communicate with him. How can I make him understand that these children will give him nothing but trouble? Should I just forbid him to communicate with them?" nine0080

Being banned from befriending these boys can backfire. You do not have the opportunity to impose your will, since he spends most of the day at school, away from you. You don't have to like your son's friends, and you can let him know if you specify exactly what is bothering you. “You know that they don’t swear in our house. Please ask your friends to follow the rules. Otherwise, they will be asked to leave.” A couple of bad words, if they hang out in your son's room, are best left unnoticed. nine0003

Please note that the problem here may not be as serious as it seems at first glance. In boys at this age, the prepubertal period begins. Experimenting with different styles of clothing is quite typical. If your son feels that you are categorical and do not support him, he will stop talking to you (as far as eleven-year-old boys can talk). Try to ignore the droopy pants and long locks - there's a reason your son likes these guys. It's interesting to know why. Things that seem disturbing to us—weird hairstyles, wild clothing styles, provocative behavior—may be especially attractive to those children who have always done everything right. Of course, you do not have to put up with bad behavior, but the right to use authority should be reserved for situations that you consider dangerous for the child or that seriously threaten family values. You need to figure out something more important than the length of your hair or the way you wear trousers: whether your son's new friends are really deviant. Talking to a school psychologist often helps shed light on whether they are skipping school or experimenting with drugs. The danger of troubled friends is that they can "teach" a child deviant behavior.

If your son feels that you are categorical and do not support him, he will stop talking to you (as far as eleven-year-old boys can talk). Try to ignore the droopy pants and long locks - there's a reason your son likes these guys. It's interesting to know why. Things that seem disturbing to us—weird hairstyles, wild clothing styles, provocative behavior—may be especially attractive to those children who have always done everything right. Of course, you do not have to put up with bad behavior, but the right to use authority should be reserved for situations that you consider dangerous for the child or that seriously threaten family values. You need to figure out something more important than the length of your hair or the way you wear trousers: whether your son's new friends are really deviant. Talking to a school psychologist often helps shed light on whether they are skipping school or experimenting with drugs. The danger of troubled friends is that they can "teach" a child deviant behavior. If they have similar problems, then you need to have a clearer idea of what is happening with your son. Maybe something is wrong in your house? Are you getting a divorce? Is there a family conflict? Was a brother or sister born? It is sometimes easier for a dad to find out what is happening from a teenager through joint activities, and not through "conversations" that mothers love so much. Discuss your concerns with other adults who know your child well: their teacher, another parent, perhaps your pediatrician. If you still feel there is cause for concern, consult with a child or adolescent psychologist. nine0003

If they have similar problems, then you need to have a clearer idea of what is happening with your son. Maybe something is wrong in your house? Are you getting a divorce? Is there a family conflict? Was a brother or sister born? It is sometimes easier for a dad to find out what is happening from a teenager through joint activities, and not through "conversations" that mothers love so much. Discuss your concerns with other adults who know your child well: their teacher, another parent, perhaps your pediatrician. If you still feel there is cause for concern, consult with a child or adolescent psychologist. nine0003

Source

How parents can help

A few tips from the book on how parents can help their children learn to make friends.

- Scientists have found that parents who use the reflective method have better socially adapted children. This means that they encourage the child to think about how his actions affect other people and himself. When such parents conduct an educational conversation, they ask the child to think about how his actions are perceived by others.

"When you didn't thank your grandmother for the gift, how do you think she felt?" While calming the child, they try to get him to express his feelings. Children who are brought up in this spirit are more likely to be chosen as friends and less likely to be rejected. nine0180

"When you didn't thank your grandmother for the gift, how do you think she felt?" While calming the child, they try to get him to express his feelings. Children who are brought up in this spirit are more likely to be chosen as friends and less likely to be rejected. nine0180

- If the father is actively involved in the upbringing of the child, this is the most powerful factor in developing the child's attention to others; this participation should ideally begin when children enter primary school. The transition from kindergarten to primary school is very important for children. Dads, who often play a leading role in demonstrating the fascination of the outside world, "oil the wheels", make the process easier. This effect is equally noticeable in both girls and boys. Those children for whom this transition is easier, have more strength to communicate with other children and empathize. Anyone would be happy to have such friends. nine0180

Source

- Do not underestimate the complexity of social interaction from the perspective of children.

What seems like nonsense to an adult can be frightening for an insecure or shy child. Simply entering a new class means deciding where to sit, how to get to know other children, and figure out the social hierarchy. Do not underestimate or oversimplify difficulties. “Oh, this is funny. You’ll just move to the next class.” To a child, this may seem like a very difficult situation. nine0192

What seems like nonsense to an adult can be frightening for an insecure or shy child. Simply entering a new class means deciding where to sit, how to get to know other children, and figure out the social hierarchy. Do not underestimate or oversimplify difficulties. “Oh, this is funny. You’ll just move to the next class.” To a child, this may seem like a very difficult situation. nine0192 - Help him find what he is good at. A musical child who feels left out in school would benefit from extra-curricular activities related to music, where he meets other children who are passionate about the same, and gain confidence through the recognition of his abilities.

- Remember that your family life is a training ground for your child to develop an understanding of how people should treat each other. Families with warm, responsive relationships and mutual support raise children who know how to show warmth, responsiveness, and support. Families with an explosive, unpredictable atmosphere release into life children whose knowledge and experience do not contribute to friendly relations.