Women give birth at home

‘Women feel they have no option but to give birth alone’: the rise of freebirthing | Childbirth

On the morning of 3 May, Victoria Johnson prepared to give birth at her home in the Highlands. One by one, her three children came downstairs to where she was labouring in a birthing pool surrounded by fairy lights, the curtains tightly shut against the outside world.

Suddenly, she felt an urge to get out of the pool. “I stood up and it felt as if the weight of the universe crashed from my head to my toes.” Her waters broke – “all over the carpet, which wasn’t ideal” – and the baby started to crown. “Everyone was there, including both grandmothers on video call,” she says. “Once the baby was out, my eight-year-old son came over and said, ‘I’m so proud of you.’ And that was everything.”

There was no midwife present. Instead Johnson and her husband had hired a doula, who offers emotional support and guidance but is not medically trained. It was only after the placenta was delivered, and carefully placed in a bowl, that a midwife was called to check their baby boy.

For Johnson, a freebirth – typically characterised as a birth without medical assistance, through choice rather than circumstance – was an empowering and positive experience. But it had been preceded by an exhausting battle with health authorities that has been the hallmark of many women’s experience of pregnancy during the pandemic. In March, as the infection rate spiralled, trusts across the UK withdrew home birth services, while others closed midwife-led birth centres. Staff shortages and a high volume of 999 calls had put enormous pressure on the system. Hospitals rushed out new rules on birth partners, who were excluded from scans and sometimes even the birth itself. Between 9 March and 9 April, there were 14 different sets of official national advice for pregnant women in the UK. This year, giving birth in hospital has often felt like a confusing, risky and lonely prospect.

The mother of children aged eight, five and three, Johnson had planned a home birth for her fourth baby after a traumatic birth experience in hospital. “I knew if I went to hospital I’d shut down and end up having a C-section,” she explains. But 35 weeks into her pregnancy, home birth services in her area were suspended.

“I knew if I went to hospital I’d shut down and end up having a C-section,” she explains. But 35 weeks into her pregnancy, home birth services in her area were suspended.

Sent into a tailspin of anxiety, Johnson wrote to her MSP, and attempted to register in a neighbouring council, where home births were still on offer. Neither was able to help. She found an independent midwife willing to assist her – but it would have meant travelling hundreds of miles south.

Born and raised in New Jersey, Johnson had told American friends the NHS was one of the main reasons she moved to Scotland. Now, feeling let down, she joined an emerging demographic of women who this year settled on a freebirth – not as their first choice, but because it seemed the best option available.

It is hard to know exactly how many babies are born by freebirth in the UK every year, but research out this month points to an increase in the number of people shunning medical assistance as a result of Covid-19 restrictions. In April, researchers at King’s College London surveyed 1,754 women – aged between 19 and 41, and from across the UK – who were either pregnant or had given birth since the beginning of lockdown, with striking findings. Of the 1,418 still pregnant in April, one in 20 (5%) were considering a freebirth; only one of these had been planning that before the pandemic. “It is a really high figure,” says Dr Mari Greenfield, co-author of the study, “especially in the context of how many women have a home birth each year” – around 2% of women in England and Wales, according to the Office for National Statistics.

In April, researchers at King’s College London surveyed 1,754 women – aged between 19 and 41, and from across the UK – who were either pregnant or had given birth since the beginning of lockdown, with striking findings. Of the 1,418 still pregnant in April, one in 20 (5%) were considering a freebirth; only one of these had been planning that before the pandemic. “It is a really high figure,” says Dr Mari Greenfield, co-author of the study, “especially in the context of how many women have a home birth each year” – around 2% of women in England and Wales, according to the Office for National Statistics.

The reasons given were complex, Greenfield says. “There was rarely one – issues such as childcare and transport came into play.” A desire to avoid going into hospital was a reason given by 39 participants. For many, this was due to a previous bad experience; for others, it was because they felt hospitals had become places of danger and contamination. And for a number of women, opting for a freebirth was not a positive choice: while 16 respondents described it as an empowering decision, 26 said they felt forced into it.

My partner held the shower head on my back for pain relief. After my son was born I was high as a kite – we’d done it

The fact that many trusts were allowing birth partners in only during “established labour” was another key concern. One respondent told King’s College researchers: “My partner is a great support: we have gone through IVF and a miscarriage together, and I couldn’t imagine doing this without him.” A single mother was worried there was no one to look after her other children: “Home births are still going ahead in my trust, but I wouldn’t be allowed my doula or kids in the room. I have no childcare and no other birth partner.”

A theme that ran throughout was safety – of the woman, her baby and the wider family. “This is interesting given the characterisation of freebirth as an inherently unsafe choice,” says Greenfield, who points to a number of medics among the cohort: the first time, she says, that a UK study has shown NHS healthcare professionals contemplating stepping outside it to freebirth. One senior hospital-based healthcare professional told the study she made her decision after home births were cancelled, and she was told she was ineligible for a midwife-led unit because her BMI was too high.

One senior hospital-based healthcare professional told the study she made her decision after home births were cancelled, and she was told she was ineligible for a midwife-led unit because her BMI was too high.

In Greenfield’s view, the study has exposed tensions that preceded the crisis, and the view of some that maternity policies can be coercive. “Covid-19 has placed a spotlight on existing problems,” she says. “When pregnant people are presented with a service they deem to be unsafe, or that does not align with their needs, they will step outside that system. What we may find is a more long-term shift towards greater numbers of women seeking to give birth in out-of-hospital settings.”

How real is the perceived risk of infection during the pandemic? While there have been confirmed cases of Covid-19 on maternity wards, it is not clear that these have led to wider outbreaks. Dr Patrick O’Brien, vice-president of the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists, says maternity units are “a very safe place for pregnant women and their babies. We know the pandemic has made many parents very anxious [but] the risk of a woman catching this virus in a maternity hospital is very low indeed.” Most units test for the virus at the time of an unplanned admission, and beforehand for inductions or caesareans. Maternity staff are tested regularly and wear personal protective equipment at all times.

We know the pandemic has made many parents very anxious [but] the risk of a woman catching this virus in a maternity hospital is very low indeed.” Most units test for the virus at the time of an unplanned admission, and beforehand for inductions or caesareans. Maternity staff are tested regularly and wear personal protective equipment at all times.

Meanwhile, freebirthing, though legal, carries obvious risks. While most births are uncomplicated, in some situations the immediate care of a qualified midwife or obstetrician could be life-saving. “When a complication occurs, such as heavy bleeding after birth, the presence of a midwife may be critical,” O’Brien says. Every woman should be supported in her birth choice, he adds, but “it’s important they are made aware of the risks and benefits of giving birth in different settings”.

The crisis facing independent midwifery is a crucial part of this jigsaw. Independent midwives are self-employed, and hired by women who find the NHS cannot support their preferred birth plan. But in June, following the twin shocks of Brexit and Covid-19, the US company that provided their insurance withdrew it, meaning they are not legally permitted to assist in childbirth.

But in June, following the twin shocks of Brexit and Covid-19, the US company that provided their insurance withdrew it, meaning they are not legally permitted to assist in childbirth.

Midwife Jacqui Tomkins, who is also chair of Independent Midwives UK, used to take two calls a week. “Suddenly, during [the first] lockdown, it rose to 20, and it was the same across the country,” she says. “Women were terrified after their home births had been cancelled and felt they had no option but to go it alone. Since the second wave, the calls have been mounting again.”

There are an estimated 150 registered independent midwives in the UK who, prior to the insurance crisis, were supporting around 2,500 women a year. “The irony is we are getting more requests than ever,” Tomkins says. “Our hands are tied when we are needed most. This is really hurting our members emotionally; many are slipping into poverty.”

Beatrice Cianchi: ‘A home birth is a right, not a privilege.’ Photograph: Rosie Barnes/The GuardianBeatrice Cianchi tried to hire an independent midwife earlier this year, after her home birth in London was cancelled on 30 March, three days before her due date. “But the fee was £4,000, and I couldn’t afford it.”

“But the fee was £4,000, and I couldn’t afford it.”

Cianchi, 32, had suffered postnatal depression following the birth of her son, Arjuna, now four. “The birth was highly medicalised. I was induced with very high doses of oxytocin and felt completely powerless.” She has few memories of her first five months as a mother. “I’d wake up each day thinking, I could be dead now and who would care? I had therapy, but it took a long time to recover.”

Her second pregnancy had been going smoothly until her family in Italy went into lockdown in early March. “I started feeling incredibly anxious and had a panic attack in front of my midwife, who reassured me, saying: ‘Don’t worry, we won’t leave you alone.’”

Yet that is exactly what happened after home birth services were withdrawn. “I felt totally abandoned,” Cianchi says. “They knew what I’d been through, so how could they do this to me? A home birth is a right, not a privilege.”

Giving birth at home this time around was, for Cianchi, imperative. She started researching unassisted birth. “When I told my midwife, she wanted to help but the hospital wouldn’t back her,” she says. Instead, she turned to a doula, who agreed to attend the birth but insisted she could provide only emotional support. In the early hours of 11 April, Cianchi’s waters broke. “We lit candles and my partner Silvio held the shower on my back for pain relief. We rang the doula and she arrived 30 minutes before my son was born. Afterwards, I was high as a kite and felt a deep joy – I couldn’t believe we’d done it.”

She started researching unassisted birth. “When I told my midwife, she wanted to help but the hospital wouldn’t back her,” she says. Instead, she turned to a doula, who agreed to attend the birth but insisted she could provide only emotional support. In the early hours of 11 April, Cianchi’s waters broke. “We lit candles and my partner Silvio held the shower on my back for pain relief. We rang the doula and she arrived 30 minutes before my son was born. Afterwards, I was high as a kite and felt a deep joy – I couldn’t believe we’d done it.”

After Arjuna’s birth, she had refused to see anyone. “This time, I wanted to show everybody what I’d done, but I couldn’t because of lockdown. I saw a different side to my partner – he knew what to do and didn’t doubt me for a second. If the first birth tore us apart, this one united us.”

That elation was tempered after speaking to their local hospital. “We called them because I was worried I might have a tear. They said what we had done was illegal and that they were going to send an ambulance. But we didn’t want that.” Instead, they were visited by a sympathetic midwife who assessed baby Juniper, now seven months old.

But we didn’t want that.” Instead, they were visited by a sympathetic midwife who assessed baby Juniper, now seven months old.

“She reassured us we had made the right decision,” Cianchi says. Still, she warns against women being pushed into freebirthing because their other options have been removed. “Women should be aware of what could go wrong and willing to get assistance if they need it.”

Alison Edwards of Doula UK, whose 700 members advocate for expectant mothers, says there was a threefold increase in calls about freebirthing between March and June. Meanwhile, Wales-based doula Samantha Gadsden set up a nominal fee-based Facebook group on freebirthing in March, because she was getting so many inquiries. It now has nearly 300 members and numbers spiked again following the second lockdown. “People were getting nervous, because they knew home births were cancelled before,” she says. Membership of her other Facebook group, Home Birth Support Group UK, has more than doubled since March, from 2,700 to 6,390.

Gadsden, who insists she does not advocate for any particular type of birth, says her members have felt unsupported in their decisions. “There are pockets of excellence, but what I’m hearing more and more is that women are being coerced and disrespected.”

Women labour best when they feel comfortable and safe. They know things can go wrong – there is rarely zero risk

Some parents choosing to freebirth have been threatened with referral to children’s services, even though they are not breaking the law. “It appears many maternity staff are not aware that women have a legal right to freebirth,” says Nadia Higson of the Association for Improvements in the Maternity Services. On 30 April, in response to reports that some women were removing themselves entirely from NHS perinatal care because of a reduction in birthplace options, the Royal College of Midwives issued guidance to members on how to support women. This made clear that it was not appropriate to refer a woman to children’s services solely because of her decision to decline medical support. “Despite this, we continue to hear reports of women being threatened,” Higson says. “It causes huge anxiety for couples. While common sense usually prevails, we do hear of some families being monitored.”

“Despite this, we continue to hear reports of women being threatened,” Higson says. “It causes huge anxiety for couples. While common sense usually prevails, we do hear of some families being monitored.”

Julie Frohlich, a London-based NHS consultant midwife with more than 35 years’ experience, says she is saddened that some women freebirth because they don’t trust healthcare professionals. “We should be supporting women’s informed choices, but too often we are trying to get a woman’s informed compliance.” She believes fear of what could go wrong can be used to direct women into decisions that aren’t right for them. “Clinicians often seem to feel it would be their responsibility if a woman were to make a choice they didn’t approve of. It’s not our role to approve a woman’s informed choice, but to facilitate it. Women labour best when they feel comfortable and safe. They know things can go wrong – there is rarely zero risk. But one woman’s high risk is another woman’s low risk, and we must respect that. ”

”

Meanwhile, NHS England has dismissed the findings of the King’s College study, claiming it shows only women’s intentions rather than what they went on to do. A spokesperson said: “Home births are now available in 98% of trusts, and NHS guidance has been clear throughout the pandemic that mothers can be accompanied by their partners for childbirth.” But trusts issue their own policies when it comes to birth partners, and access varies.

Zoe Kimpton has twice been reported to social services for freebirthing, most recently following the arrival of her eighth child, Arthur, in October. “He was a wild card and I was nervous from the moment I found out I was pregnant,” she says.

Zoe Kimpton with baby Arthur and her four-year-old daughter: ‘I didn’t want to be shunted around a hospital.’ Photograph: Abbie Trayler-Smith/The GuardianWhen she was 35 weeks pregnant with Arthur’s brother, now 15 months, her lung collapsed and she had an elective caesarean in hospital. Her first three children had been born in hospital, followed by a home birth and two freebirths. But Kimpton didn’t want to take any risks with her seventh child. “I wasn’t going to jeopardise my health or his,” she says. “That birth was beautiful in its own way, because as I lay there in theatre I was so grateful he hadn’t been harmed by my health issue.”

But Kimpton didn’t want to take any risks with her seventh child. “I wasn’t going to jeopardise my health or his,” she says. “That birth was beautiful in its own way, because as I lay there in theatre I was so grateful he hadn’t been harmed by my health issue.”

But when Kimpton, now 40, became pregnant with Arthur, there was a new factor: Covid-19. “After my lung collapse, I would have liked NHS input at my birth. But I didn’t want to be shunted around a hospital knowing Covid-19 attacks the respiratory system. It was a scary decision. I was worried home birth services could be cancelled at any time.” She decided her safest option was to freebirth with the support of her husband, and call for help if needed.

In the end, Arthur’s birth was straightforward. “I leant up against the sofa and laboured,” Kimpton says, “then I got in the pool. The kids were coming up, kissing me and playing with glowsticks in the water. My husband was very supportive, and his aunt popped in now and again with fruit for the children. ”

”

But after the birth, Kimpton was losing a lot of blood. She was transferred to hospital, where she underwent surgery for a retained placenta. “It would have happened wherever I was,” she says. “But afterwards a doctor, with a herd of students, came and reprimanded me. Later I learned that while I’d been in theatre, someone was calling social services. The midwife was apologetic – it was the hospital’s policy – but I felt deeply offended.”

Kimpton, who volunteers as a bereavement group coordinator, believes in the importance of being able to make our own decisions about both birth and death. “I pioneer for a gentle birth, but also for a gentle end of life. These are big decisions we should all be free to make as individuals.”

Even for women who have had a positive birth experience in the past nine months, navigating the challenges brought about by Covid-19 may have a lasting effect. A recent survey of 15,000 pregnant women and new mothers by the UK charity Pregnant Then Screwed found 90% of respondents said hospital restrictions were having a negative impact on their mental health. An open letter from 34 MPs and campaigners sent last month to the NHS stated, “The long-term impact of these restrictions for new mothers and their families could be catastrophic.”

An open letter from 34 MPs and campaigners sent last month to the NHS stated, “The long-term impact of these restrictions for new mothers and their families could be catastrophic.”

According to Maria Booker of Birthrights, “Trust has been lost during this pandemic and maternity services must now work hard to rebuild that. We are still getting lots of reports from women affected by restrictions around birth partners. And while most home birth services are back up and running, there are concerns these could be put at risk again if maternity staff are hit by Covid-19.” A Royal College of Midwives survey published last month revealed that 75% of midwives think staffing levels in their NHS trust are unsafe.

Six months after the birth of her son, Victoria Johnson is still angry at the weeks she lost to anguish over her birth plan. “I don’t get back that month of soul-searching,” she says. “It was dehumanising from start to finish. When it comes to women’s birth rights, there is a massive demographic being left behind. We do not have sovereignty over our own bodies.”

We do not have sovereignty over our own bodies.”

Moms Say Philippines 'No Home Birth' Policy Adds Burdens During Pandemic : Goats and Soda : NPR

Marissa Tuping, a rural midwife, and Risa Calibuso, right, arrive in Nueva Vizcaya Provincial Hospital on July 21. Calibuso gave birth to her son moments later. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Marissa Tuping, a rural midwife, and Risa Calibuso, right, arrive in Nueva Vizcaya Provincial Hospital on July 21. Calibuso gave birth to her son moments later.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Risa Calibuso, 34, wanted to give birth to her second child at home.

In the Philippines, where she lives, that's against the law.

In 2008 the country passed the Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and Nutrition Strategy policy — referred to as the "no home birth" policy. The goal was to reduce the country's high rates of maternal mortality, from 203 out of 100,000 live births that year to 52 by 2015.

It's a controversial law. Despite the good intentions, some local groups assert that it impinges on the rights of women.

What's more, the policy has not yet met its goal. In 2017, the maternal mortality rate in the Philippines was 121 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Nor has there been a significant change in the rates of infant mortality. In 2008, there were 25.5 deaths per 1,000 live births. In 2018, the figure was 22.5.

The pandemic of 2020 has made the policy even more controversial. In the past, women who live in remote areas have had to arrange for transportation to the nearest appropriate health-care facility. Now matters are even more complicated. With pandemic-related restrictions on transportation options like cabs and motorized tricycles, women who do not own a car have fewer choices.

With pandemic-related restrictions on transportation options like cabs and motorized tricycles, women who do not own a car have fewer choices.

Then again, the policy was complicated even before COVID-19 struck.

Some regions of the Philippines will fine a woman who gives birth at home when she comes to a hospital to register her baby. Other provinces do not fine the woman but may chastise her when she brings in her newborn to be registered.

Meanwhile, across the country, the law has had a chilling impact on midwives. If they assist at a home birth, they risk losing their accreditation.

Marissa Tuping, a rural midwife and health-care worker, walks to visit pregnant mothers in the village of Abinganan. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Marissa Tuping, a rural midwife and health-care worker, walks to visit pregnant mothers in the village of Abinganan.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

As with many laws, those who are well-to-do can get around the restrictions. They would have to hire a private doctor to assist with a home birth, sterilize a birthing area in their residence and rent an ambulance on standby.

But for many women, this is hardly an option.

A mother's burden

The story of Risa Calibuso brings the many issues swirling around the policy into sharp focus.

Calibuso was expecting her second child in July. She lives with her family in Abinganan, a village of 1,700 people on rugged terrain in Bambang. Her husband, Michael, age 36, dries rice for a living and earns 345 pesos ($7) a day. She does not work and describes the family as "indigent." She and her husband do not own a car — they can't afford it.

Risa Calibuso and her husband, Michael Calibuso, at home in Abinganan, a village of 1,700 people on rugged terrain in the municipality of Bambang. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Risa Calibuso and her husband, Michael Calibuso, at home in Abinganan, a village of 1,700 people on rugged terrain in the municipality of Bambang.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

To comply with the No Home Birth policy, she'd have to travel 11 miles – a trip of about an hour over rough roads – to the nearest clinic.

The Calibusos pay $73.94 a year for medical insurance, and yet she was worried that her insurance wouldn't cover all the expenses.

"Traditional birth attendants are cheaper," says Calibuso, who used an attendant when she delivered her first child at home. They are typically paid with tips amounting to the equivalent of about $10 — or higher if the family has a higher income.

They are typically paid with tips amounting to the equivalent of about $10 — or higher if the family has a higher income.

What's more, Calibuso really wanted to give birth at home. She did it with her first child in 2007, before the policy went into effect, and she felt like that went OK.

So she did not arrange in advance for transportation to that clinic that was 11 miles away. When she went into labor at 8 p.m. on July 19, she figured she would call a midwife, Marissa Tuping, and retired birth attendant, Florida Domingo, in the morning and hope for the best.

She gambled – and lost. When the midwife and attendant came to her home, they found that Calibuso's water had already broken and she was spotting blood. Yet the midwife would not agree to help deliver the baby lest her own career be jeopardized.

Marissa Tuping, the midwife, says, "I can never pull the baby out. If there is a home birth, it will affect my performance review." Like many midwives, Tuping works under the Department of Health and must renew her contract with them every year. "I'm scared that if there is home birth on my record, I will lose my job," she says.

"I'm scared that if there is home birth on my record, I will lose my job," she says.

Calibuso's only option for medical care was to travel those 11 miles. A neighbor had a motorcycle, but it was unavailable. The last resort was the motorized tricycle, provided by the government for the village to use in emergencies like these; it was also not available.

Midwife Merissa Tuping, right, assists Risa Calibuso, who is in labor, with her breathing while the reporter drove her to the nearest hospital. Because of the Philippine law against home birth, the midwife would not deliver the child in Calibuso's residence. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Midwife Merissa Tuping, right, assists Risa Calibuso, who is in labor, with her breathing while the reporter drove her to the nearest hospital. Because of the Philippine law against home birth, the midwife would not deliver the child in Calibuso's residence.

Because of the Philippine law against home birth, the midwife would not deliver the child in Calibuso's residence.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

This put me, as a journalist, in a difficult situation. I had arrived to photograph the birth; I traveled by car with a driver.

As a reporter, I am trained not to intervene in the lives of my subjects – but given the circumstance, I felt I had to offer to bring her to the hospital. The midwife came along and talked to Calibuso about how to breathe through the contractions.

Fortunately we made good time. Given that it was an emergency, we drove fast, and the drive took a little over a half an hour. A few minutes after arriving at the hospital, Calibuso gave birth to Heinrich Claude, a healthy baby boy.

Even though many women find the policy burdensome, the government stands by it. "Every birth, life is at risk — and as a doctor who knows the risks, I will not advocate for a home birth," says Dr. Agnes Bernabe, 47, an obstetrician and gynecologist. She works in a private clinic in Bambang and at Nueva Vizcaya Provincial Hospital and is a member of the committee that reviews maternal death in the province. "Home births and traditional healings [procedures done by a local healer after birth] are the usual causes of maternal and neonatal deaths."

Agnes Bernabe, 47, an obstetrician and gynecologist. She works in a private clinic in Bambang and at Nueva Vizcaya Provincial Hospital and is a member of the committee that reviews maternal death in the province. "Home births and traditional healings [procedures done by a local healer after birth] are the usual causes of maternal and neonatal deaths."

Dr. Agnes Bernabe and her team deliver a baby by cesarean section at the Nueva Vizcaya Provincial Hospital on August 18. "As a doctor who knows the risks, I will not advocate for a home birth," says Bernabe. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Dr. Agnes Bernabe and her team deliver a baby by cesarean section at the Nueva Vizcaya Provincial Hospital on August 18. "As a doctor who knows the risks, I will not advocate for a home birth," says Bernabe.

"As a doctor who knows the risks, I will not advocate for a home birth," says Bernabe.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

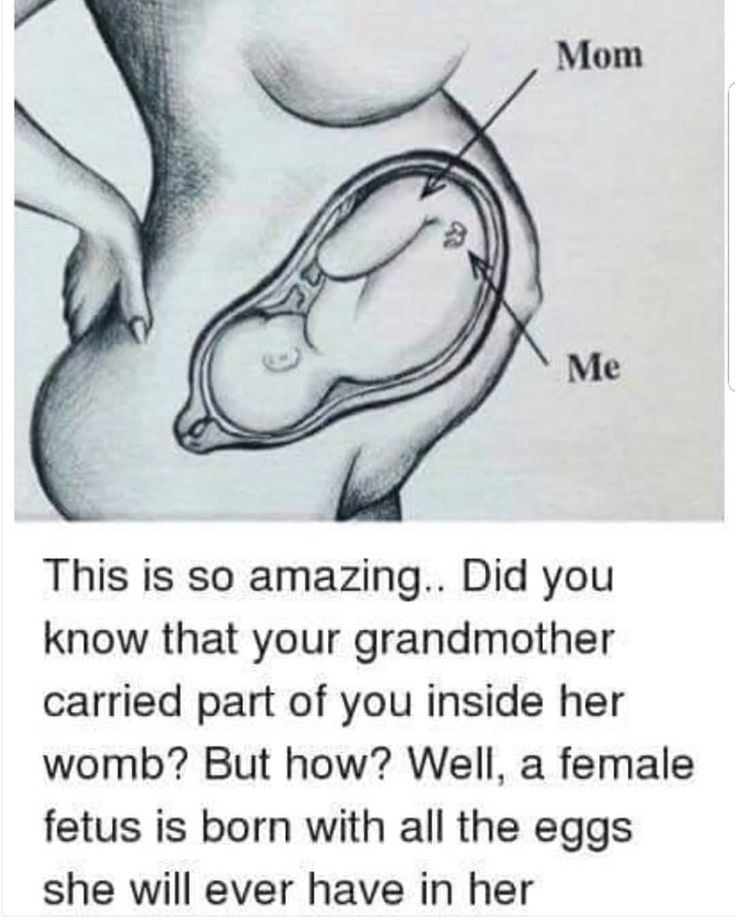

Her concerns are backed up by data. According to the Department of Health, the majority of maternal deaths in the Philippines are a direct result of pregnancy complications that occur during labor and delivery and also from issues that arise in the post-partum period. When the policy was implemented in 2008, a little over half of births in the Philippines were at home. Only about a third of those take place with the assistance of traditional birth attendants (who are not medically trained). There are no comparable statistics regarding the role of midwives.

The policy, adds Bernabe, has helped mothers become "more informed now about the importance of seeing a doctor and hospital births."

Pandemic anxiety adds to the stress

Lockdown restrictions around public transportation — which in some villages, change every couple of weeks – is making it harder for women to get to a health facility.

Some mothers have had to rent an apartment before giving birth, creating an additional cost for them to bear.

"Our house is two hours away from the hospital, so we came down and rented an apartment two weeks before my due date," says Mylene Madawat, a 24-year-old mother from the upland municipality of Santa Fe who gave birth on July 24.

Mylene Madawat, 24, holds her newborn son. Her mother, Minda, right, is by her side. Because Madawat does not live near a health-care facility and home births are against the law in the Philippines, she rented an apartment in a community that has a hospital where she could give birth. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Mylene Madawat, 24, holds her newborn son. Her mother, Minda, right, is by her side. Because Madawat does not live near a health-care facility and home births are against the law in the Philippines, she rented an apartment in a community that has a hospital where she could give birth.

Her mother, Minda, right, is by her side. Because Madawat does not live near a health-care facility and home births are against the law in the Philippines, she rented an apartment in a community that has a hospital where she could give birth.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Madawat ended up delivering her 8-pound baby boy through a cesarean section at the hospital. Due to her surgery, she and her mother Minda, who came down from their village, needed to stay longer in the apartment they rent for 4,000 pesos ($82) plus utilities a month. And Madawat needed to finish her postpartum and neonatal check-ups. "This apartment is so expensive, we can't wait to go back home," she says.

"I'm scared of the virus, what if I get it from the hospital?" says Jessa Tayombong, a 32-year-old mother from Banggot, a village in the province of Nueva Vizcaya.

Even though she knew that home births aren't allowed, she delivered her daughter Josie at home on July 14 with the help of a neighbor, who had assisted women in their village with births before but was not a skilled birth attendant.

Luckily for Tayombong and the neighbor, their village has not enacted a financial penalty for home births. So when she registered the child's birth, she was only chastised by health-care workers and village officials. And to register the child she had to go to the hospital for a neonatal checkup. So in the end, she had to do what she feared and went to a health-care facility during the pandemic.

Jessa Tayombong sits with her baby, Josie. Even though home births are illegal in the Philippines, Tayombong delivered the child at home. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Jessa Tayombong sits with her baby, Josie. Even though home births are illegal in the Philippines, Tayombong delivered the child at home.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Pushing back against the policy

The Gabriela Women's Party, a grassroots organization that advocates for the rights of marginalized Filipino women, has been trying for years to get rid of the policy.

"The No Home Birth policy is against the rights of mothers," says the organization's deputy secretary-general Joan Salvador. "Women should be given all the necessary information and choices on how and where to give birth. Whether she wants to give birth at home or in a facility, the government should provide all the necessary support and services to ensure her safety and that of the child."

In 2014, Gabriela filed House Resolution 1531, a written motion to the Philippines Congress to challenge the No Home Birth policy and investigate the fines on women and health care workers.

It didn't pass, so Gabriela re-filed it in 2016 — but it was never brought up for debate.

Members of the Bambang health unit question Jessa Tayombong (center) about the home birth of her daughter, Josie, on July 14, which goes against government policy. At right is neighbor Jelina Campoy, who assisted with the birth. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Members of the Bambang health unit question Jessa Tayombong (center) about the home birth of her daughter, Josie, on July 14, which goes against government policy. At right is neighbor Jelina Campoy, who assisted with the birth.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Lynn Freedman, a professor of population and family health at Columbia University, agrees that a policy that punishes women for giving birth at home is not the way to go. "Criminalizing or outright banning home deliveries is a blunt, potentially rights-violating instrument for getting to the ultimate goal," she says.

"Criminalizing or outright banning home deliveries is a blunt, potentially rights-violating instrument for getting to the ultimate goal," she says.

Still, she adds, hospitals and health care facilities have a crucial role in reducing maternal mortality. "If a woman gets a serious obstetric complication during delivery, such as hemorrhage, her survival often depends on getting timely access to emergency obstetric care in a health facility or hospital that can save her life," she says.

"The way to get there has to be multidimensional," she adds. "The country may need to build more facilities, hire more staff who are properly trained and equipped, make sure people have a way to get to the hospital."

Florida Domingo massages Calibuso's belly. The early morning massage is part of a traditional healing process after delivery. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Florida Domingo massages Calibuso's belly. The early morning massage is part of a traditional healing process after delivery.

The early morning massage is part of a traditional healing process after delivery.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

As for Risa Calibuso, she is at home with her newborn son. When I visited her, she was undergoing a traditional healing process from the Ilocana ethnic group with Florida Domingo, a retired birth attendant. The method includes binding the stomach with fabric for several days. In addition, the attendant administers early morning massage.

That's what she did after the birth of her first son.

"It is part of our culture," she says.

And she tells me she is very happy that the stress of giving birth is now behind her.

Risa Calibuso breastfeeds her son, Heinrich Claude, in their balcony. He was born on July 27. Calibuso went into labor at home but the local midwife would not participate in a home delivery. Because there were no other options to get Calibuso to the Nueva Vizcaya Provincial Hospital for delivery, the reporter gave her a ride. Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR hide caption

toggle caption

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Risa Calibuso breastfeeds her son, Heinrich Claude, in their balcony. He was born on July 27. Calibuso went into labor at home but the local midwife would not participate in a home delivery. Because there were no other options to get Calibuso to the Nueva Vizcaya Provincial Hospital for delivery, the reporter gave her a ride.

Xyza Cruz Bacani For NPR

Xyza Cruz Bacani is a freelance photographer based in Southeast Asia and the author of the book We Are Like Air. She previously contributed to NPR for a story on babies born during the pandemic, in collaboration with Everyday Projects.

Why do women go to home births and what are the risks. We analyze with experts in the heading "Give birth - you will understand" | 74.ru

All newsThe mayor's office responded to the complaints of Chelyabinsk residents about uncleaned roads

Passenger bus overturned near Chelyabinsk, there are injured

"Thank you for considering us ordinary people": inclusive education in the Southern Urals is 30 years old

South Ural residents will be able to order free delivery of an express test for HIV

"From Genghis Khan's bodyguard". Who are the Hamnigans and how do they save their native language

Made in Russia: who will fill the region’s need for meat delicacies

Blood, ChEMK and judo: metallurgists and athletes held a joint donor campaign

Alfa-Bank car loans became available in Chelyabinsk as well

A bus with 22 shift workers overturned near Chelyabinsk. An online report about an emergency during a snowfall

Emissions stuffing: what is behind the suddenly optimistic plan for an environmental revolution in Chelyabinsk

It's time to return this money to yourself: test your knowledge of what the state owes you

“This is the clinical death of the auto industry”: we publish a list of brands and their misadventures in Russia

Grain deal is suspended, and Russia is ready for negotiations for October 30

After a scandal with traffic jams in the yards, the avenue in the North-West was opened ahead of schedule

“Some kind of rubbish”: random passers-by were asked about Halloween - their answers surprised

Corgi party in honor of Halloween took place in Chelyabinsk. Dogs dressed up in Harry Potter costumes and more

Dogs dressed up in Harry Potter costumes and more

A beauty courier from Siberia became a model in Turkey. Previously, she delivered orders for 16 hours a day - how her life has changed

Firefighters were sent to the tent camp for the mobilized in the Chelyabinsk region for exercises

Simple or with bubbles? A cardiologist named 4 advantages of carbonated water over regular water

In Magnitogorsk, a driver of a crossover hit two pensioners on a zebra. Video

Star Tree: a list of the most popular celebrities for New Year's corporate parties and their fees

Fishermen of the Chelyabinsk region recorded a video message to Putin

Three Russian women died during the Halloween celebration in the capital of South Korea what we know about seeds is a lie

“You pay as much as you left your car for minutes”: an urbanist about the introduction of paid parking in Chelyabinsk

“Even with one eye can help in the rear”: how vision problems affect the category suitability - doctors explain

A Vietnamese cafe of the St. Petersburg network "Ded Ho" will open in Chelyabinsk

Petersburg network "Ded Ho" will open in Chelyabinsk

Telegram was blocked by Roskomnadzor

During the celebration of Halloween in the capital of South Korea, more than a hundred people died

Attack on the Black Sea Fleet, new foreign agents and Buzova in the DPR: news around SVO for October 29

In the Chelyabinsk region they said goodbye to a 22-year-old shooter, mobilized in September

A resident of Chelyabinsk died in an accident on the way to Kurgan. Six people in hospital

Divorced, and “everything started spinning”: mother of many children with magnificent forms became the star of beauty contests regions

Politicians, artists and bloggers are leaving. Which of the Russian celebrities received foreign citizenship

Schoolgirl or gopnitsa? 7 Hats That Will Ruin Even a Beauty Queen (But You Wear Them Anyway)0003

“They are honking, yelling and driving across the playground”: due to the blocking of the avenue in the North-West, a collapse occurred in the yards

All news

Tanya gave birth to her first child in the maternity hospital and decided that she would not return there again

Photo: Artyom Ustyuzhanin / Е1.RU

Share

Every year in Russia there are thousands of couples who give birth at home. The network of city portals has found a couple who dared to do it twice and do not regret anything. At the same time, they also had the experience of a maternity hospital - with an older child. Tatyana spoke about the reasons for her choice, and the gynecologist and neonatologist spoke about the risks that a woman takes by refusing the help of doctors.

My husband and I are 12 years old. She gave birth to her first son at the age of 23. She walked with the motto "Everyone gave birth and I give birth." Specially not prepared, but the son was very long-awaited. She gave birth in a maternity hospital. I arrived immediately with contractions in the interval of 7 minutes. I thought: “Since it hurts so much, it means that I will soon meet my son.” But the opening was small, and the pains were hellish.

I was screaming when a male doctor came for an examination. He rudely cut off my screams with the words “Shut your mouth. They all give birth in one place.” The flow of those giving birth was dense, so the nurses were not particularly suitable for screaming. The most infernal thing was that for two hours I lay under CTG on my back, in this unnatural position for childbirth. I thought I would die.

He rudely cut off my screams with the words “Shut your mouth. They all give birth in one place.” The flow of those giving birth was dense, so the nurses were not particularly suitable for screaming. The most infernal thing was that for two hours I lay under CTG on my back, in this unnatural position for childbirth. I thought I would die.

12 hours have passed. No one was going to wait for me to “give birth”. Without knowing, they pierced the bubble, put a dropper. When my son was in my arms, I became hysterical, and then I passed out in a dream in a pre-fainting state.

The second daughter was an unplanned child. When I found out that I was pregnant, a chill went down my back and the fear of childbirth fettered my chest. At first, I decided to prepare thoroughly: I learned the stages of childbirth, the structure of the female body, and read about breathing. Miraculously, on Instagram, I went to girls who gave birth at home, and then to home birth courses. Courses were held together with her husband. They learned everything thoroughly - up to the topic "if something goes wrong."

They learned everything thoroughly - up to the topic "if something goes wrong."

Bags for the maternity hospital were collected, but when the contractions started, I realized that I would not go there. Everything went just perfect. I felt all the female power, the energy of childbirth. My husband and I were completely immersed in this sacrament.

The third daughter was also unexpected. The third time I did not even collect the bag to the hospital. Where and how I will give birth, I already knew and was not afraid of anything.

The girl found like-minded people for home births on Instagram

Photo: Artyom Ustyuzhanin / E1.RU

Share

As Tanya said, she was in the bath during all the contractions until she tried to push both daughters, so it was easier to bear the pain. My husband was by my side all the time. The placenta was buried in the garden. Now the middle daughter is three years old, and the youngest is a year old.

According to Elena Kudryavtseva, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, cases of home births occur annually, but this phenomenon is infrequent.

“For the most part, women simply didn't have time to get to the maternity hospital in time, because everything went very quickly,” she says. “But there is always a high rate of child deaths in this group. Yes, someone was lucky and everything ended well, but the statistics mercilessly testify not in favor of home birth.

Not so long ago, there was a very sad incident in one of the maternity hospitals in Yekaterinburg. A woman in labor was admitted there with an anhydrous period of several days, obvious inflammatory phenomena and purulent discharge.

The case ended in a caesarean section because she had severe weakness in labor. The child was born in a critical condition, he required a long resuscitation. In addition, the woman had to remove the uterus. As it turned out, after the outpouring of amniotic fluid, she decided not to go to the hospital, because she was waiting for the start of labor at home on the advice of a midwife who was engaged in illegal activities. By the way, when an ambulance is called during a home birth, the midwife accompanying the woman, as a rule, disappears.

As it turned out, after the outpouring of amniotic fluid, she decided not to go to the hospital, because she was waiting for the start of labor at home on the advice of a midwife who was engaged in illegal activities. By the way, when an ambulance is called during a home birth, the midwife accompanying the woman, as a rule, disappears.

Health care at home is extremely limited. For example, during home birth, it is impossible to diagnose the condition of the fetus using an instrumental recording of its heart rhythm or ultrasound diagnosis. These procedures allow you to identify the beginning of the suffering of the fetus in time and take any measures. Of course, if there is a need for operative delivery, this cannot be done at home either, and this does not happen so rarely.

According to doctors, after a home birth, a woman runs the risk of losing a child and, in general, the opportunity to have children

Photo: Artyom Ustyuzhanin / E1.RU

Share

Many situations in the process of childbirth, when prompt assistance is required, are not so obvious, and only an experienced obstetrician-gynecologist can understand them. For example, if during childbirth a discrepancy between the size of the fetal head and the mother's pelvis is found. When there are obvious manifestations of this pathology, then medical care may be belated. You definitely need to call an ambulance if there is bleeding: this may be a symptom of uterine rupture or premature detachment of the placenta, but in this case, most likely, it will not be possible to save the child.

Among obstetricians, the following phrase is known: the shortest and most dangerous journey that a person makes in his life is childbirth. This means that even an absolutely healthy child in the process of childbirth can die or be seriously injured. But that's only part of the problem. The other side of the coin is the health, and in some cases, the life of the woman giving birth. For example, during childbirth, premature detachment of the placenta with massive bleeding may occur. It is impossible to predict this complication, while in a significant part of cases it leads to the death of the child, and sometimes the mother.

For example, during childbirth, premature detachment of the placenta with massive bleeding may occur. It is impossible to predict this complication, while in a significant part of cases it leads to the death of the child, and sometimes the mother.

Even with a healthy pregnancy, childbirth can go unpredictably

Photo: Artyom Ustyuzhanin / E1.RU

Share

According to neonatologist Anna Mirzoeva, even a full-term baby can adapt to extrauterine life in different ways, and sometimes it requires observation or treatment .

— These could be breathing problems that could harm the child if left untreated. The nature of the amniotic fluid may change. For example, getting meconium into the lungs leads to severe pneumonia, the physician noted. - In maternity hospitals there are wards, the conditions of which are as close as possible to home. We welcome partner births, there are births with a personal midwife or with a doula, a woman should be comfortable in the maternity hospital. When deciding where your birth will take place, you can go on tours of maternity hospitals, even online. And make the right choice.

When deciding where your birth will take place, you can go on tours of maternity hospitals, even online. And make the right choice.

Related

-

July 29, 2022, 14:49

In Chelyabinsk, doctors of a children's clinic came to the aid of a woman who gave birth in a car -

September 14, 2021, 16:25 give birth in a minibus

-

August 14, 2021, 13:00

“What the hell do you need it for? It's a woman's business." Honest story of men about partner births

Irina Akhmetshina

Journalist

GynecologistHome and partner birthsHome birthCaesarean sectionNeonatologistNewbornPartner birthMaternity HospitalBirthBirth at homeDaughter was born

- LIKE0

- LAUGHTER2

- SURPRISE0

- ANGER1

- SAD1

See the typo? Select a fragment and press Ctrl+Enter

COMMENTS42

Read all comments

What can I do if I log in?

COMMENT RULES

0 / 1400 This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and Google. The Privacy Policy and Terms of Use apply.

The Privacy Policy and Terms of Use apply.

Media news2

Media news2

We give birth like at home - articles from the specialists of the clinic "Mother and Child"

Zimina Natalya Nikolaevna

Obstetrician-gynecologist

MD GROUP Clinical Hospital

How home birth is represented

The most typical arguments of supporters of home births:

- A woman's body is designed specifically to give birth to children. By nature, it has all the necessary strengths and capabilities to give birth to a healthy child on its own, which means that the help of a doctor in this process is completely unnecessary.

- The maternity hospital is not needed, because the atmosphere in it is official, hospital, and this does not contribute to relaxation in contractions and the opening of the cervix.

- When giving birth at home, you can take any position that is comfortable for the woman.

- And at home, you can give birth in the water (in the bath), or at least just relieve contractions by immersion in water.

- During home birth, not strangers (doctors, midwives) will be nearby, but the husband, relatives or friends.

- From the first minutes of birth, the child will be constantly next to his mother, he will not be fed, he will not be subjected to unnecessary manipulations and examinations.

Well, ideally, supporters of home births present them like this: effective contractions begin at 40 weeks, the first stage of labor lasts no longer than 10-12 hours. At this time, the woman in labor behaves in a way that is convenient for her, takes comfortable postures, uses techniques to anesthetize contractions (massage, breathing, water). Then comes the complete opening of the cervix, water spontaneously pours out, there are attempts, during which a healthy baby is born without much effort. The child is immediately applied to the mother's breast - he sucks it as much as he wants, the umbilical cord is cut only after the end of the pulsation. Mom has no breaks, the child is absolutely healthy. In general, everyone is satisfied and happy.

Mom has no breaks, the child is absolutely healthy. In general, everyone is satisfied and happy.

Actually

The picture of home birth is presented, of course, idyllically. And how happy ordinary women would be, and doctors too, if every birth went that way. But it’s not always possible to give birth the way you breathe. In childbirth or immediately after them, various unpleasant situations can arise with a woman or a child. We will not list them so as not to upset anyone. Let's just say that often the life and health of mother and baby depend on how quickly they received medical care . But what can be done at home in such a situation? The only thing is to call an ambulance, because it is impossible to help a child with asphyxia or a woman with bleeding or high blood pressure without certain drugs, equipment, and simply medical skills. But after all, one of the specialists will be present at the birth with the expectant mother? Good obstetricians and gynecologists are well aware of the high risk of home births, so they do not accept births at home, and a midwife, even with experience, will only cope with the simplest situation. In addition, many so-called spiritual obstetricians, as a rule, do not even have a higher, often secondary medical education, and, of course, they do not bear any legal responsibility for the outcome of childbirth. And it happens that sometimes in home births there is no midwife at all (did not come or the woman was convinced that she was not needed). Therefore, of course, we can agree that the home environment helps a lot, but will it be possible to give birth in it in the event of some non-standard or difficult situation?

In addition, many so-called spiritual obstetricians, as a rule, do not even have a higher, often secondary medical education, and, of course, they do not bear any legal responsibility for the outcome of childbirth. And it happens that sometimes in home births there is no midwife at all (did not come or the woman was convinced that she was not needed). Therefore, of course, we can agree that the home environment helps a lot, but will it be possible to give birth in it in the event of some non-standard or difficult situation?

Natural childbirth is possible

But how then to ensure naturalness in childbirth and are there such childbirth at all? In fact, today, natural childbirth is widely carried out in most maternity hospitals, and is not only carried out, but also actively promoted . If everything goes well, if the birth proceeds correctly, if the baby’s heart beats evenly, and the mother feels good, the doctors of the maternity hospital do not interfere with the birth, but simply observe their course. A woman gives birth on her own, as nature dictates. But what about the notorious home comfort in childbirth? Turns out Today, natural childbirth "at home" is provided by many maternity hospitals :

A woman gives birth on her own, as nature dictates. But what about the notorious home comfort in childbirth? Turns out Today, natural childbirth "at home" is provided by many maternity hospitals :

- Almost everywhere is now actively practiced free behavior during childbirth : a woman in labor does not have to lie on the bed all the contractions, but can choose any position.

- In many maternity hospitals there are various devices to facilitate contractions : transforming beds, balls, ropes (with their help you can take different positions in contractions), and in some, in addition to the shower, there is even a jacuzzi in which you can spend the first stage of childbirth.

- Of course, not all, but already many Russian maternity hospitals have either been renovated or built in accordance with modern ideas about beauty and comfort . Even in free maternity hospitals there are cozy double rooms with a private bathroom, fresh renovation and beautiful linens.

What can we say about childbirth under a contract or in a commercial clinic - the conditions there are more than excellent.

What can we say about childbirth under a contract or in a commercial clinic - the conditions there are more than excellent. - According to the order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, in any maternity hospital where there are separate birthing boxes, a husband, girlfriend, personal midwife or even a psychologist can be present at the birth, and absolutely free of charge . So, the expectant mother will not be left without support.

- Today, in all maternity hospitals, babies are immediately applied to the mother's breast; it is also possible for mother and baby to stay together in the postpartum department.

- Now you can easily find a maternity hospital where you can live together with your husband after childbirth in a comfortable family room . All this, of course, is not free - but if you really want it, then it is quite feasible.

So do not be afraid of the maternity hospital: it has all the conditions for natural and safe childbirth. And home birth is an unjustified risk and an unknown result.

And home birth is an unjustified risk and an unknown result.

Have you read at least one story about childbirth at home that ended unsuccessfully? Hardly. And if they read it, it is not enough. And the reason for this, as a rule, is the same: with an unfavorable development of childbirth and problems with the child, a woman is aware of her carelessness and simply keeps silent about it.

“They used to give birth in the field” is one of the popular arguments of supporters of home births. They gave birth, but only the mortality rate in childbirth (both children and mothers) was extremely high.

An individual approach to the expectant mother and her baby, living together, free behavior during childbirth, the opportunity to choose a doctor and midwife, take a husband to give birth - all this is now available in many Russian maternity hospitals

5 signs that you are having a natural birth in the hospital

- Freedom of movement: in the maternity box there is a multifunctional bed-transformer, balls, ropes.