Why are newborns given vitamin k

FAQs About Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding

Since 1961, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended supplementing low levels of vitamin K in newborns with a single shot of vitamin K given at birth. Low levels of vitamin K can lead to dangerous bleeding in newborns and infants. The vitamin K given at birth provides protection against bleeding that could occur because of low levels of this essential vitamin.

Below are some commonly asked questions and their answers. If you continue to have concerns about vitamin K, please talk to your pediatrician or healthcare provider.

Q: What is vitamin K, and how do low levels of vitamin K and vitamin K deficiency bleeding occur in babies?

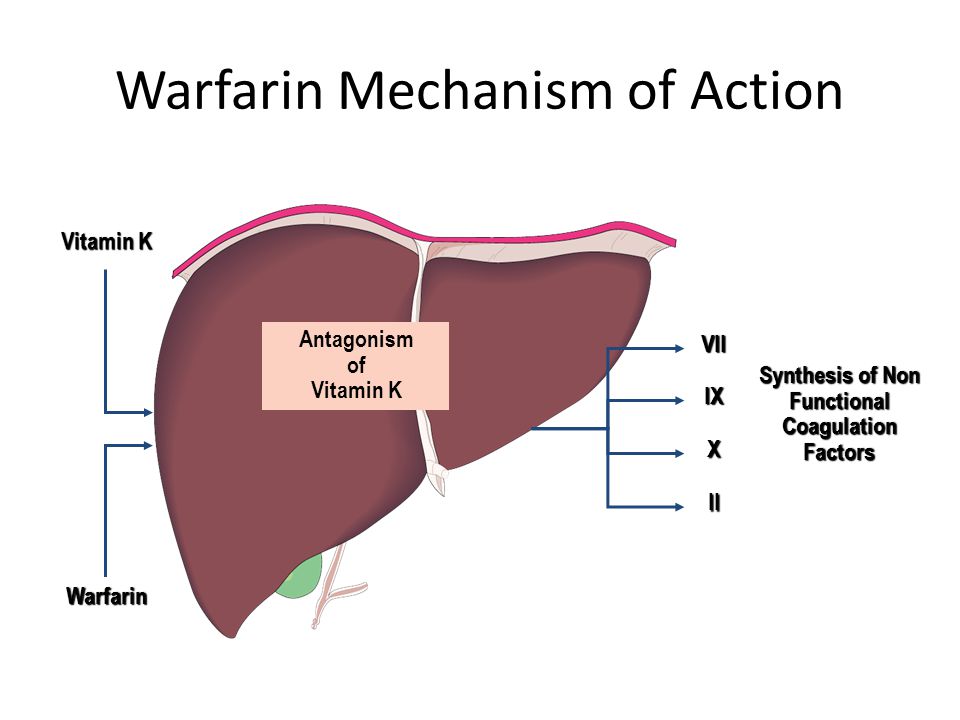

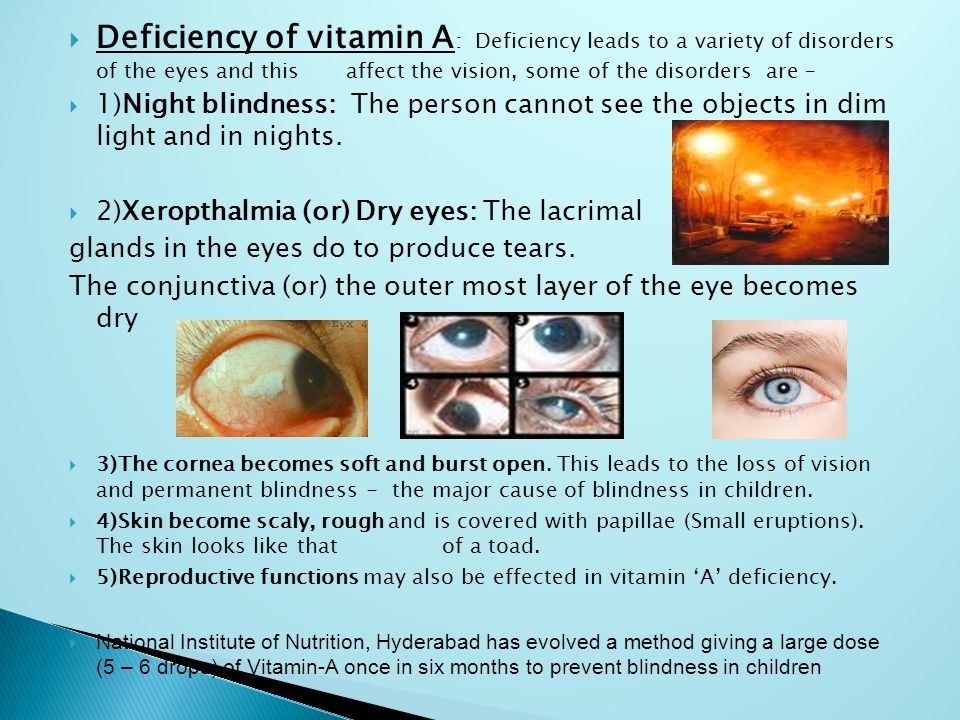

A: Vitamin K is used by the body to form clots and to stop bleeding. Babies are born with very little vitamin K stored in their bodies. This is called “vitamin K deficiency” and means that a baby has low levels of vitamin K. Without enough vitamin K, babies cannot make the substances used to form clots, called ‘clotting factors.’ When bleeding happens because of low levels of vitamin K, this is called “vitamin K deficiency bleeding” or VKDB. VKDB is a serious and potentially life-threatening cause of bleeding in infants up to 6 months of age. A vitamin K shot given at birth is the best way to prevent low levels of vitamin K and vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB).

Q: Why do ALL babies need a vitamin K shot – can’t I just wait to see if my baby needs it?

A: No, waiting to see if your baby needs a vitamin K shot may be too late. Babies can bleed into their intestines or brain where parents can’t see the bleeding to know that something is wrong. This can delay medical care and lead to serious and life-threatening consequences. All babies are born with very low levels of vitamin K because it doesn’t cross the placenta well. Breast milk contains only small amounts of vitamin K. That means that ALL newborns have low levels of vitamin K, so they need vitamin K from another source. A vitamin K shot is the best way to make sure all babies have enough vitamin K. Newborns who do not get a vitamin K shot are 81 times more likely to develop severe bleeding than those who get the shot.

Breast milk contains only small amounts of vitamin K. That means that ALL newborns have low levels of vitamin K, so they need vitamin K from another source. A vitamin K shot is the best way to make sure all babies have enough vitamin K. Newborns who do not get a vitamin K shot are 81 times more likely to develop severe bleeding than those who get the shot.

Q: Doesn’t the risk of bleeding from low levels of vitamin K only last a few weeks?

A: No, VKDB can happen to otherwise healthy babies up to 6 months of age. The risk isn’t limited to just the first 7 or 8 days of life and VKDB doesn’t just happen to babies who have difficult births. In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) investigated 4 cases of infants with bleeding from low levels of vitamin K. All four were over 6 weeks old when the bleeding started and they had been healthy and developing normally. None of them had received a vitamin K shot at birth.

Q: Isn’t VKDB really rare?

A: VKDB is rare in the United States, but only because most newborns get the vitamin K shot. Over the past two decades, many countries in Europe have started programs to provide vitamin K at birth – afterward, they all saw declines in the number of cases of VKDB to very low levels. However, in areas of the world where the vitamin K shot isn’t available, VKDB is more common, and many cases of VKDB have been reported from these countries

In the early 1980s in England, some hospitals started giving vitamin K only to newborns that were thought to be at higher risk for bleeding. They then noticed an increase in cases of VKDB. This tells us that giving vitamin K to prevent bleeding is what keeps VKDB a rare condition – when vitamin K is not given to newborns, cases of bleeding occur and VKDB stops being rare.

Q: What happens when babies have low levels of vitamin K and get VKDB?

A: Babies without enough vitamin K cannot form clots to stop bleeding and they can bleed anywhere in their bodies. The bleeding can happen in their brains or other important organs and can happen quickly. Even though bleeding from low levels of vitamin K or VKDB does not occur often in the United States, it is devastating when it does occur. One out of every five babies with VKDB dies. Of the infants who have late VKDB, about half of them have bleeding into their brains, which can lead to permanent brain damage. Others bleed in their stomach or intestines, or in other parts of the body. Many of the infants need blood transfusions, and some need surgeries.

The bleeding can happen in their brains or other important organs and can happen quickly. Even though bleeding from low levels of vitamin K or VKDB does not occur often in the United States, it is devastating when it does occur. One out of every five babies with VKDB dies. Of the infants who have late VKDB, about half of them have bleeding into their brains, which can lead to permanent brain damage. Others bleed in their stomach or intestines, or in other parts of the body. Many of the infants need blood transfusions, and some need surgeries.

Q: I heard that the vitamin K shot might cause cancer. Is this true?

A: No. In the early 1990s, a small study in England found an “association” between the vitamin K shot and childhood cancer. An association means that two things are happening at the same time in the same person, but doesn’t tell us whether one causes the other. Figuring out whether vitamin K might cause childhood cancer was very important because every newborn is expected to get a vitamin K shot. If vitamin K was causing cancer, we would expect to see the same association in other groups of children. Scientists looked to see if they could find the same association in other children, but this association between vitamin K and childhood cancer was never found again in any other study.

If vitamin K was causing cancer, we would expect to see the same association in other groups of children. Scientists looked to see if they could find the same association in other children, but this association between vitamin K and childhood cancer was never found again in any other study.

Q: Can the other ingredients in the shot cause problems for my baby? Do we really know that the vitamin K shot is safe?

A: Yes, the vitamin K shot is safe. Vitamin K is the main ingredient in the shot. The other ingredients make the vitamin K safe to give as a shot. One ingredient keeps the vitamin K mixed in the liquid; another keeps the liquid from being too acidic. One of the ingredients is benzyl alcohol, a preservative. Benzyl alcohol is a common ingredient in many medications.

In the 1980s, doctors recognized that very premature infants who were in neonatal intensive care units might become sick from benzyl alcohol toxicity because many of the medicines and fluids needed for their intensive care contained benzyl alcohol as a preservative. Although the toxicity was only reported for very premature infants, since then doctors have tried to minimize the amount of benzyl-alcohol-containing medications they give. Clearly, the small amount of benzyl alcohol in the vitamin K shot is not enough to be dangerous, even when given in combination with other medications that also contain small amounts of this preservative.

Although the toxicity was only reported for very premature infants, since then doctors have tried to minimize the amount of benzyl-alcohol-containing medications they give. Clearly, the small amount of benzyl alcohol in the vitamin K shot is not enough to be dangerous, even when given in combination with other medications that also contain small amounts of this preservative.

Q: The dose of the shot seems high. Is that too much for my baby?

A: No, the dose in the vitamin K shot is not too much for babies. The dose of vitamin K in the shot is high compared to the daily requirement of vitamin K. But remember babies don’t have much vitamin K when they are born and won’t have a good supply of vitamin K until they are close to six months old. This is because vitamin K does not cross the placenta and breast milk has very low levels of vitamin K.

The vitamin K shot acts in two ways to increase the vitamin K levels. First, part of the vitamin K goes into the infant’s bloodstream immediately and increases the amount of vitamin K in the blood. This provides enough vitamin K so that the infant’s levels don’t drop dangerously low in the first few days of life. Much of this vitamin K gets stored in the liver and it is used by the clotting system. Second, the rest of the vitamin K is released slowly over the next 2-3 months, providing a steady source of vitamin K until an infant has another source from his or her diet.

This provides enough vitamin K so that the infant’s levels don’t drop dangerously low in the first few days of life. Much of this vitamin K gets stored in the liver and it is used by the clotting system. Second, the rest of the vitamin K is released slowly over the next 2-3 months, providing a steady source of vitamin K until an infant has another source from his or her diet.

Q: Can I increase vitamin K in my breast milk by eating different foods or taking multivitamins or vitamin K supplements?

A: We encourage moms to eat healthy and take multivitamins as needed. Although eating foods high in vitamin K or taking vitamin K supplements can slightly increase the levels of vitamin K in your breast milk, neither can increase levels in breast milk enough to provide all of the vitamin K an infant needs.

When infants are born, their already low levels of vitamin K fall even lower. Infants need enough vitamin K to (a) make up for their extra-low levels, (b) start storing it in the liver for future use, and (c) ensure good bone and blood health. Breast milk – even from mothers supplementing with vitamin K sources – can’t provide enough to do all of these things.

Breast milk – even from mothers supplementing with vitamin K sources – can’t provide enough to do all of these things.

Q: My baby is so little. What can I do to make the vitamin K shot less painful and traumatic?

A: Babies, just like us, feel pain, and it is important to reduce even small amounts of discomfort. Babies feel less pain from shots if they are held and allowed to suck.You can ask to hold your baby while the vitamin K shot is given so that your baby can be comforted by you. Breastfeeding while the shot is given and immediately after can be comforting too. All of these are things parents can do to ease pain and soothe their baby.

Remember that if your baby does not get the vitamin K shot, his or her risk of developing severe bleeding is 81 times higher than if he or she got the shot. Diagnosis and treatment of VKDB often involves many painful procedures, including repeated blood draws.

Q: Overall, what are the risks and benefits of the vitamin K shot?

The risks of the vitamin K shot are the same risks that are part of getting most any other shot. These include pain or even bruising or swelling at the place where the shot is given. A few cases of skin scarring at the site of injection have been reported. Only a single case of allergic reaction in an infant has been reported, so this is extremely rare.

Although there have been concerns about some other risks, like a risk for childhood cancer or risks because of additional ingredients, none of these risks have been proven by scientific studies.

The main benefit of the vitamin K shot is that it can protect your baby from VKDB, a dangerous condition that can cause long-term disability or death. In addition, the diagnosis and treatment of VKDB often includes multiple and sometimes painful procedures, such as blood draws, CT scans, blood transfusions, or anesthesia and surgery.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended the Vitamin K shot since 1961, and has repeatedly stood by that recommendation because the risks of the shot don’t outweigh the risks of VKDB, which are based on decades of evidence and decades of experience with babies who were hospitalized or died from VKDB.

Your child’s doctor is the best person to talk to about vitamin K. Like you, your child’s doctor wants to see your children grow up safe and healthy and wants to support your efforts to make the best decisions for their health. If you have concerns about vitamin K, talk to your child’s doctor.

Why Your Newborn Needs a Vitamin K Shot

By: Ivan L. Hand, MD, MS, FAAP

There's a lot going on when your baby is first born. They're weighed and measured. Their noses are suctioned out and their vital signs are tested. They may have ointment or drops put in their eyes. They get a complete checkup by your pediatrician.

Most newborns get their first hepatitis B vaccine in the hospital. They also routinely get a vitamin K shot.

But what exactly is vitamin K, and do newborns really need it? Read on to learn more.

What does vitamin K do?

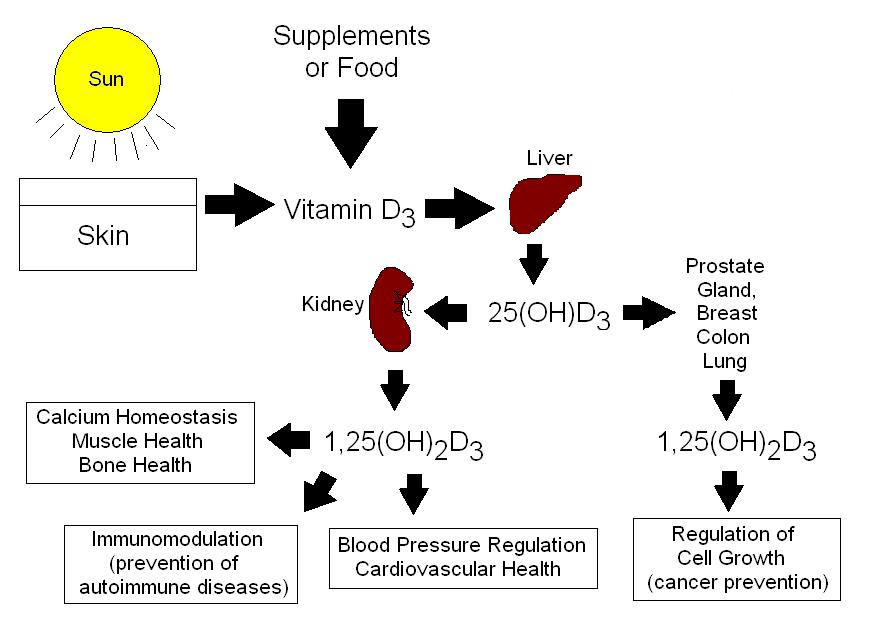

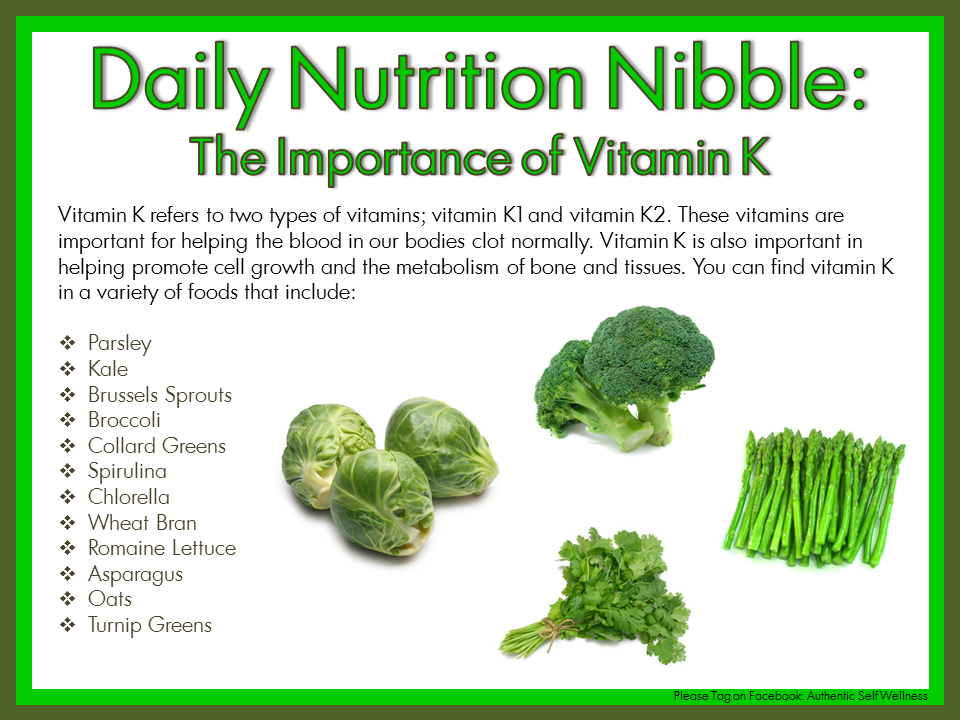

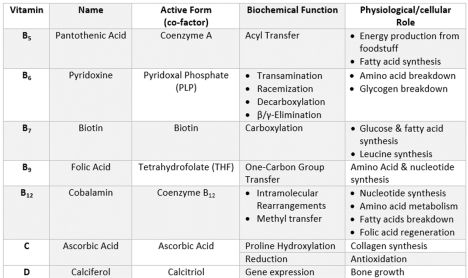

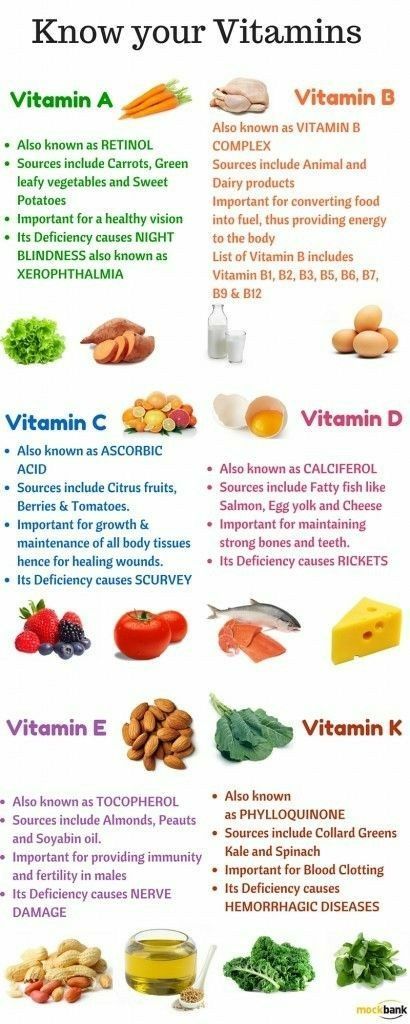

Vitamin K is a fat-soluble nutrient that helps our bodies make blood clots. We need blot clots to stop bleeding. Vitamin K is important for keeping bones healthy too.

Adults and older children get vitamin K from food such as green, leafy vegetables, meat, dairy and eggs. The healthy bacteria in our intestines, which make up our microbiome, also produce some vitamin K.

Babies, though, have very little vitamin K in their bodies at birth. This puts them at risk for bleeding. Fortunately, it's easy to prevent VKDB with a vitamin K shot. The injection is given in your baby's thigh within 6 hours of birth.

One shot is all it takes to protect your baby from getting vitamin K deficiency bleeding. This is why, as pediatricians, we have recommended since 1961 that all newborns get a vitamin K shot at birth.

Why babies aren't born with enough vitamin K?

The two big reasons newborns need vitamin K:

They don't get much vitamin K from the mother during pregnancy. Unlike many other nutrients, vitamin K doesn't pass through the placenta very easily.

Babies' intestines don't have very many bacteria yet, so their bodies can't make enough vitamin K.

What is vitamin K deficiency bleeding?

Newborns who don't get a Vitamin K shot and are low on the vitamin are are at risk of vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB). This happens when a baby's blood can't make clots, and their body can't stop bleeding.

The bleeding can happen on the outside of the body. It can also happen inside the body where parents can't see it. A baby could be bleeding into their intestines or brain before their parents know anything is wrong. Brain bleeding happens in about half of all babies who develop VKDB, and it can lead to brain damage or death.

There are three types of vitamin K deficiency bleeding:

Early-onset: This begins within the first 24 hours after birth. It usually happens when the mother is taking certain medications that interfere with vitamin K.

Classical: This happens between 2 days and 1 week after birth. Doctors don't know exactly what causes most of these cases. Early-onset and classical VKDB occur in 1 in 60 to 1 in 250 newborns.

Late-onset: This happens between 1 week and 6 months after birth. It's rarer than early-onset or classical VKDB, occurring in 1 in 14,000 to 1 in 25,000 babies. Infants who didn't get a vitamin K shot at birth are 81 times more likely to develop late-onset VKDB than babies who do get the shot.

Cases of VKDB seem to be increasing. This is partly because more parents are refusing the vitamin K shot for their newborns. VKDB is fairly rare, so many parents aren't aware of how dangerous the effects of this disease can be.

Are vitamin K shots safe?

Yes, vitamin K shots are very safe. The vitamin K from the injection is stored in your baby's liver and released slowly over months. This gives your baby the vitamin K they need until they can start getting it from solid food and making it themselves.

You may have heard about a study from the 1990s about a possible link between the vitamin K shot and developing childhood cancer. This didn't only worry parents; doctors and scientists were concerned too. Since then, experts have done many different kinds of studies to verify this link. None of the studies have ever been able to find that link again.

Can my newborn get oral vitamin K instead?

Some parents may ask for oral vitamin K instead of the shot. But babies can't absorb the oral form very well, so it doesn't work well to prevent VKDB. A vitamin K shot is the safest and best option for all newborns.

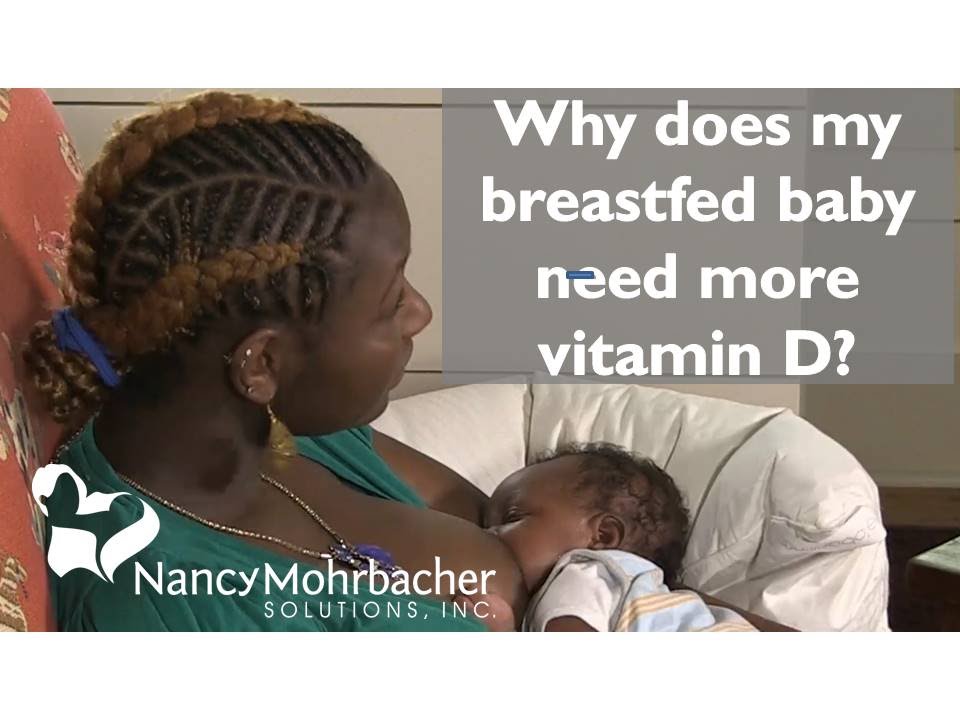

Does breastfeeding give my baby vitamin K?

Breast milk does give your baby a little bit of vitamin K. But it's not enough to prevent VKDB. Babies who are exclusively breastfed are at higher risk of developing VKDB because their vitamin K levels are low.

But it's not enough to prevent VKDB. Babies who are exclusively breastfed are at higher risk of developing VKDB because their vitamin K levels are low.

This all changes when your baby is old enough to start eating solid foods, usually between 4 and 6 months. The bacteria in your baby's intestines will also start making vitamin K once they're eating solid foods.

What are the signs of vitamin K deficiency bleeding?

In most cases, there aren't any warning signs to let you know beforehand that something serious—and possibly life-threatening—is happening.

When babies develop VKDB, they might have one or more of these signs:

Bleeding from the umbilical cord or nose

Paler skin or, in dark-skinned babies, pale gums

Bruising easily, especially around the face and head

Bloody stool or black, dark, sticky stool

Vomiting blood

A yellow tint to the white parts of the eyes 3 weeks or more after birth

Seizures, irritability, excessive vomiting or sleeping too much

Remember

It's easy and safe to prevent VKDB with a vitamin K shot at birth. If you have any questions or concerns, be sure to talk to your pediatrician. They can help you weigh the benefits and risks.

If you have any questions or concerns, be sure to talk to your pediatrician. They can help you weigh the benefits and risks.

More information

- Newborns Need Vitamin K Shortly After Birth to Prevent Bleeding Disease

- Vitamin K and the Newborn Infant (AAP Policy Statement)

About Dr. Hand

Ivan L. Hand, MD, MS, FAAP, is Director of Neonatology, Kings County/Health & Hospitals and a Professor of Pediatrics at SUNY-Downstate School of Medicine. He was selected as a 2022 New York Super Doctor and is a member of the Society for Pediatric Research. Within the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Dr. Hand is a member of the Committee on Fetus and Newborn.

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

Why are newborns given vitamin K injections?

At Mother and Child clinics, we recommend vitamin K injections for all newborns to prevent hemorrhagic disease.

Hemorrhagic disease (HRD), or vitamin K-deficient hemorrhagic syndrome, is a disease manifested by increased bleeding in newborns and children during the first months of life, due to a deficiency of blood coagulation factors, the activity of which depends directly on vitamin K.

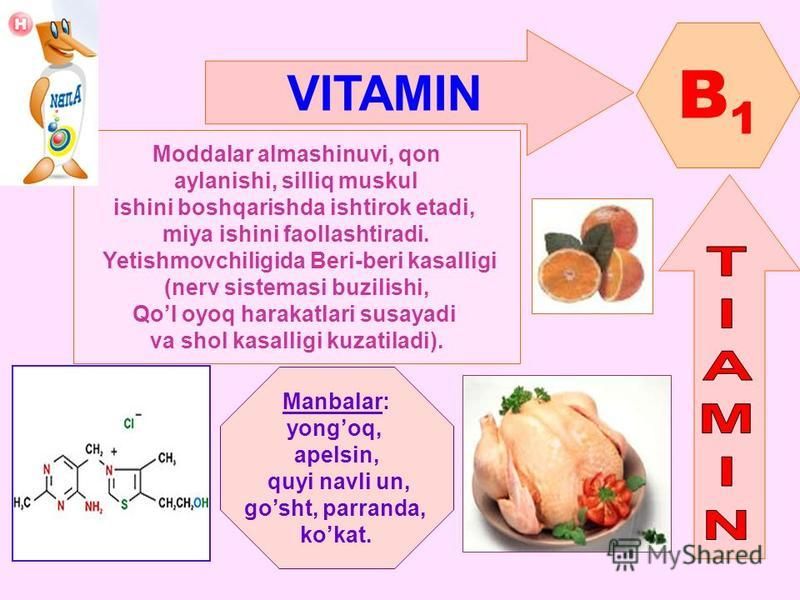

Vitamin K of plant origin, which is called vitamin K 1 or phylloquinone, enters the body with food - green vegetables, vegetable oils, dairy products. Another form of vitamin K, vitamin K2, or menaquinone, is of bacterial origin. Vitamin K 2 is mainly synthesized by the intestinal microflora, which is extremely poor in newborns.

In healthy newborns, the level of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors in blood plasma is 30-60% of that in adults. Their concentration increases gradually and reaches the level of adults by the sixth week of life. In almost all healthy full-term infants in the first five days of life, there is a decrease in the level of procoagulants, physiological anticoagulants and plasminogen.

In almost all healthy full-term infants in the first five days of life, there is a decrease in the level of procoagulants, physiological anticoagulants and plasminogen.

For the newborn, the only source of vitamin K is mother's milk, formula or medicine. Moreover, the amount of vitamin K received by a child depends on the type of feeding. The level of vitamin K 1 in breast milk ranges from 1 to 10 µg/l, on average 2-2.5 µg/l, which is significantly lower than in artificial milk formulas (about 50 µg/l in mixtures for full-term babies; 60 -100 mcg / l - in mixtures for premature babies). Thus, newborns, due to their physiological characteristics of the coagulation system and vitamin K metabolism, are predisposed to the development of vitamin K-deficient hemorrhagic syndrome.

PLEASE NOTE! Poor blood clotting is a condition dangerous for the body, in which bleeding or hemorrhage is noted in various organs. This pathology develops in 0.25-0.5% of newborns.

RISK FACTORS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF RHD

• Exclusive breastfeeding

• Lack of prophylactic administration of vitamin K immediately after birth

• Chronic fetal hypoxia and asphyxia at birth

• Giving birth

• Intrauterine development delay

• Giving birth by cesarean section

• Nedness

• The use of a wide range of

• Long -term parenteral nutrition in the conditions of inadequate supply of

• Diseases and condition of the child that contribute impaired synthesis and absorption of vitamin K

• malabsorption syndrome (cystic fibrosis, diarrhea with fat malabsorption lasting more than one week)

• short bowel syndrome;

• cholestasis;

• pre-eclampsia

• maternal diseases (liver and intestinal diseases).

Vitamin K for the prevention of bleeding in newborns

Vitamin K is required for the synthesis of blood coagulation factors in the liver, which include factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX and X, as well as anticoagulant proteins C and S. In newborns at term, especially those who are exclusively breastfed may develop vitamin K deficiency and therefore associated bleeding because breast milk contains very low levels of vitamin K.

Problematic and management of bleeding in preterm infants

Premature infants are potentially at even higher risk of developing vitamin K deficiency-associated bleeding due to delayed feeding and subsequent delay in colonization of their gastrointestinal tract by microflora involved in vitamin K production, use of antibacterial drugs, as well as due to inferior liver function and hemostasis. The administration of vitamin K preparations to prevent bleeding associated with vitamin K deficiency has been described to some extent in both term and premature infants. It is indicated that a single intramuscular injection of 1 mg of a vitamin K preparation after birth is effective in this regard.

It is indicated that a single intramuscular injection of 1 mg of a vitamin K preparation after birth is effective in this regard.

There is evidence that not only injectable but also oral vitamin K supplementation improves biochemical parameters of coagulation in infants. However, none of these approaches has been studied in the framework of randomized trials for bleeding of various periods (early, classic and late) after birth. Concern has also been expressed about the prophylactic use of vitamin K preparations due to the presence of phenol in their composition, which has potentially carcinogenic properties. A systematic review of the literature did not reveal an increased risk of malignant neoplasms in children after intramuscular injections of vitamin K preparations, so the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) continues to recommend prophylactic intramuscular administration of 0.5-1 mg of a vitamin K preparation to infants after birth to prevent early, classic and late form of associated bleeding in term babies.

Recommendations for the use of vitamin K supplements in preterm infants are less specific because associated bleeding has not been widely discussed in the literature. This may be partly due to the fact that most preterm infants in intensive care units are routinely given prophylactic vitamin K supplementation, and that parenteral nutrition is started early, providing preterm infants with more than enough vitamin K. However, there are many reasons to believe that preterm infants may be at greater risk of associated bleeding, and that these bleeding may be more important, especially in relation to the risk of intraventricular hemorrhage.

Based on this, scientists in the United States of America conducted a systematic review of studies to determine the effect of vitamin K supplementation in preventing vitamin K deficiency-associated bleeding in preterm infants. The results of this work were published on February 5, 2018 in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Trial and participant selection criteria

Searched Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and electronic databases MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, and others. Scientists reviewed randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials of any vitamin K supplement given to preterm infants. At the same time, intramuscular and intravenous injections, as well as oral use of various vitamin K preparations in various dosages, were compared with non-intervention. As a result, 899 records, of which scientists analyzed 7 full-text studies.

Scientists reviewed randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials of any vitamin K supplement given to preterm infants. At the same time, intramuscular and intravenous injections, as well as oral use of various vitamin K preparations in various dosages, were compared with non-intervention. As a result, 899 records, of which scientists analyzed 7 full-text studies.

Primary outcomes

- Any bleeding.

- Any serious bleeding requiring immediate blood transfusion.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Intracranial hemorrhages.

*All types of bleeding in the primary outcomes were studied in two subgroups: infants less than 7 days of age and older.

Secondary outcomes included laboratory parameters (at and after the first week of life) and potential side effects of prophylactic vitamin K supplementation.

Findings and conclusions from a systematic review Compared with non-intervention, and in only one study, scientists have considered various dosages and routes of administration of vitamin K supplements in preterm infants.

The results obtained indicate that the majority of infants who received intramuscular or intravenous injections of vitamin K preparations at a dosage of 0.2 mg had supraphysiological levels of vitamin K in the blood on the 5th day of life.

The results obtained indicate that the majority of infants who received intramuscular or intravenous injections of vitamin K preparations at a dosage of 0.2 mg had supraphysiological levels of vitamin K in the blood on the 5th day of life. At the same time, it was found that intravenous administration of 0.2 mg of the drug is slightly more effective than intramuscular injection of 0.5 mg, according to analyzes of the level of vitamin K in the blood at the end of the observation. However, there were no significant differences between the use of 0.2 mg intravenous, 0.2 and 0.5 mg intramuscular vitamin K in relation to general pathologies associated with prematurity, including other clinical bleeding, sepsis, ventriculomegaly, as well as in relation to mortality. .

Another study looked at blood concentrations of vitamin K in infants 22 to 32 weeks of gestational age who received either 1 mg or 0.5 mg of a vitamin K preparation as part of prophylaxis, with the dosage determined by the attending physician at the infants' admission to the unit neonatal intensive care. Infants were exclusively breastfed, with the exception of individual cases when this was not possible. It was found that the difference in the concentration of vitamin K in the blood of infants on the 2nd and 10th day of life was not statistically significant between the two groups.

Infants were exclusively breastfed, with the exception of individual cases when this was not possible. It was found that the difference in the concentration of vitamin K in the blood of infants on the 2nd and 10th day of life was not statistically significant between the two groups.

In conclusion, the investigators concluded that preterm infants are currently receiving unreasonably high doses of vitamin K supplements in some cases. The investigators argue that, due to uncertainty, clinicians should extrapolate data from term newborns to preterm infants. Because there is no available evidence that vitamin K is harmful or ineffective, and because vitamin K is inexpensive, it would be prudent to follow the recommendations of expert bodies and prescribe vitamin K supplements to preterm infants. In this regard, further studies are needed on the appropriate dosages and routes of administration of vitamin K preparations, especially among preterm infants <30 weeks of gestational age, who are at high risk of developing hemorrhagic complications such as intraventricular hemorrhage.