Types of inductions

Reasons, Types, and Risk Factors

Inducing labor, also known as labor induction, is a procedure where a doctor or midwife uses methods to help you go into labor.

In most cases, it’s best to let labor happen on its own, but there are exceptions. Your doctor may decide to induce you for medical reasons or if you’re 2 or more weeks past your due date.

Talk with your doctor about whether labor induction is right for you.

In a perfect world, you’ll go into labor right on cue at 40 weeks. However, sometimes the process doesn’t go as smoothly as expected, and the baby runs late.

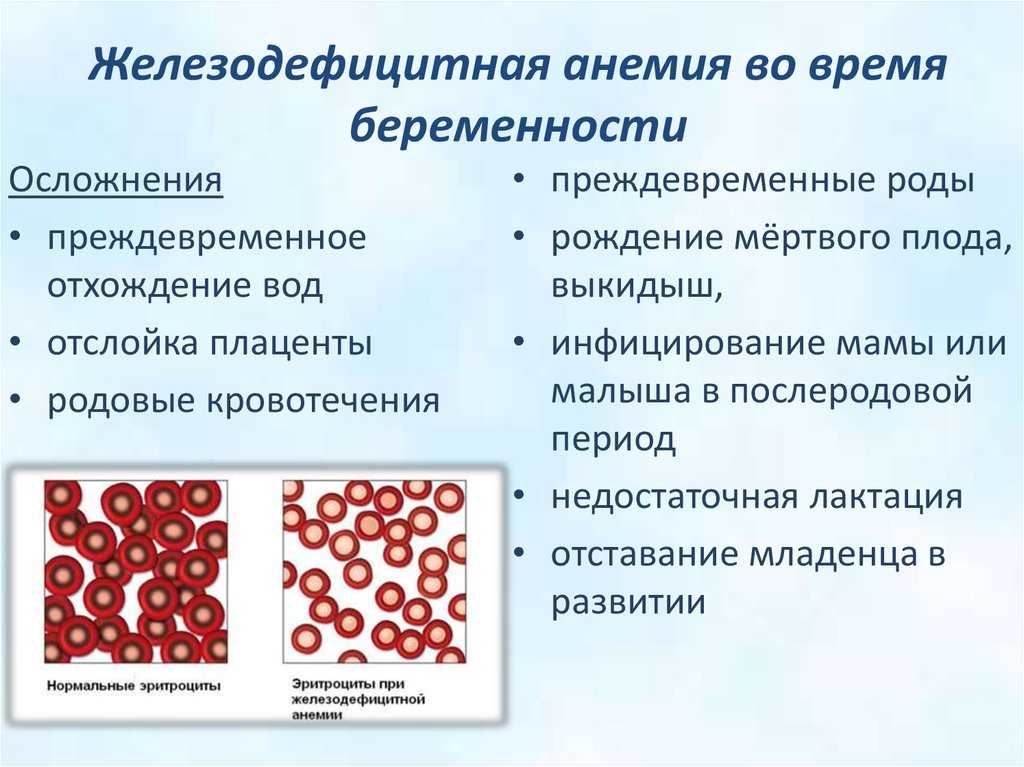

Certain medical problems can make an extended pregnancy risky for you and your baby, including:

- growth problems in the baby

- too little amniotic fluid around the baby

- gestational diabetes

- high blood pressure

- preeclampsia

- a uterine infection

- placental separation from the uterus

- Rh incompatibility

Your doctor may need to induce labor if your water breaks before you start getting contractions. Contractions are a sign that labor has started and your cervix has begun to open. A lack of contractions could mean that your body isn’t preparing for delivery like it should.

You might prefer to induce if you live far from a hospital or have a history of delivering quickly. Inducing labor may also be medically necessary after 42 weeks. At this point, the placenta can no longer provide enough oxygen and nutrients for your baby.

Preeclampsia is another reason for inducing labor. Preeclampsia is when you develop high blood pressure and at least one related symptom. If you have high blood pressure during pregnancy, delivering your baby early could prevent complications.

There are a few ways to speed up the process if your baby is behind schedule. The safest and most effective way is to see your doctor. Medications or medical techniques can bring on labor more quickly.

The other option is to try to induce labor on your own. Before you try anything, talk with your doctor or midwife. Make sure the method you’re attempting is safe and that your pregnancy is at the optimal time to induce.

Make sure the method you’re attempting is safe and that your pregnancy is at the optimal time to induce.

Two types of medications induce labor. Drugs called prostaglandins soften the cervix to ready it for delivery. You can take these drugs by mouth, or they can be inserted as a suppository into your vagina.

The second type of drug kick-starts contractions. Pitocin is the most common of these medications. You get it through an IV.

Your cervix needs to be ready for labor or the medications won’t work. Learn the pros and cons of using medication to induce labor.

Medication isn’t the only way to get your labor started. Membrane stripping and breaking your water are two other options.

Stripping the membranes involves the amniotic sac. Your doctor uses their fingers to push the amniotic sac away from the cervix.

To break your water, the doctor pops open the amniotic sac with a small plastic hook. Your baby will then move its way to the top of your cervix in preparation for delivery. You could go into labor days or even hours later.

You could go into labor days or even hours later.

Membrane stripping is generally considered safe, but experts disagree on whether this practice is worth doing.

For a more natural approach without medical intervention, you can try inducing labor on your own. Studies haven’t verified that these methods work, so check with your doctor or midwife before trying any of them.

One of the easiest and safest ways to try inducing labor on your own is to take a walk. The gravity from your movements may help slide your baby down into position. Although a walk may not speed up your pregnancy, it’s good for you in general.

Having sex can also help. Semen contains hormones called prostaglandins, which make your uterus muscles contract. Having an orgasm yourself will also stimulate your uterus.

There’s no evidence that getting more active will help induce labor, but it’s good for your health and pregnancy. Exercise reduces your risk of a C-section and gestational diabetes.

It’s safe for most people to exercise during their pregnancy. Still, it’s a good idea to check with your doctor beforehand. Certain conditions may mean you should avoid exercise completely during pregnancy.

Deep inside the core of a pineapple is an enzyme called bromelain that breaks down proteins. That property makes it a key ingredient in many meat tenderizers.

The theory behind using bromelain for labor induction is that it might break down tissue in your cervix and soften it to prepare for delivery. There’s no scientific evidence that this theory is true, however.

Bromelain might work well on meat, but it’s not very active in the human body. Plus, pineapple could worsen pregnancy heartburn.

While it’s usually best to let nature take its course, inducing labor may be a good idea if there’s a problem with your pregnancy or your baby. If you’re healthy, an induction might help you avoid a C-section.

A 2018 study found that women in their first pregnancy who were induced at 39 weeks were less likely to need a C-section than those who waited. Complication rates didn’t differ between the two groups.

Complication rates didn’t differ between the two groups.

Ask your doctor whether it makes sense to induce at 39 weeks if:

- this is your first pregnancy

- you’re only carrying one baby

- you and your baby are healthy

C-sections can be risky, causing complications like bleeding and infection. While they may be necessary in certain cases, these surgical deliveries can also cause more problems with future pregnancies.

Your labor will be induced in a hospital or birthing center. The process will differ based on which technique your doctor uses to induce labor. Sometimes doctors use a combination of methods.

Depending on the techniques your doctor tries, it can take anywhere from a few hours to several days for your labor to start. Most of the time, induction will lead to vaginal delivery. If this doesn’t work, you might need to try again or have a C-section.

What you can expect depends on the method of induction:

- Prostaglandins come as a suppository that goes into your vagina.

After a few hours, the medication should trigger labor.

After a few hours, the medication should trigger labor. - You’ll get Pitocin through an IV. This chemical stimulates contractions and helps speed up the labor process.

- During amniotic sac rupture, the doctor will place a plastic hook inside your vagina to open up the sac. You may feel a warm rush of water as the sac breaks. When your water breaks, your body’s prostaglandin production increases, which should start your contractions.

The hospital staff will monitor your contractions to see how your labor is progressing. Your baby’s heartbeat is also monitored.

Health concerns and a long pregnancy are reasons why you might consider labor induction. It’s not a decision to make lightly since inducing labor can have serious risks. These include:

- premature birth

- slowed heart rate in the baby

- uterine rupture

- infections in both parent and baby

- excessive bleeding in the parent

- umbilical cord issues

- lung problems in the baby

- stronger contractions

- vision and hearing problems in the baby

- poor lung and brain development

Labor inductions don’t always work. If your induction isn’t successful, you may need a C-section.

If your induction isn’t successful, you may need a C-section.

The drugs and techniques used to induce labor can cause side effects for both you and your baby. Pitocin and other medications that soften your cervix can intensify contractions, making them come faster and closer together.

More intense contractions may be more painful for you. Those faster contractions can also affect your baby’s heart rate. Your doctor might stop giving you the medication if your contractions are coming too quickly.

Rupturing the amniotic sac may cause the umbilical cord to slip out of your vagina before your baby. This is called prolapse. Pressure on the cord can reduce your baby’s oxygen and nutrient supply.

Labor needs to start within about 6 to 12 hours after rupturing your amniotic sac. Not going into labor within that time frame increases the risk of infection for both you and your baby.

The Bishop score is a system your doctor uses to figure out how soon you’ll deliver and whether to induce labor. It gets its name from obstetrician Edward Bishop, who devised the method in 1964.

It gets its name from obstetrician Edward Bishop, who devised the method in 1964.

Your doctor will calculate your score from the results of a physical exam and ultrasound. The score is based on factors like:

- how far your cervix has opened (dilated)

- how thin your cervix is (effacement)

- how soft your cervix is

- where in the birth canal your baby’s head is (fetal station)

A score of 8 or above means you’re close to starting labor and that induction should work well. Your odds of a successful induction go down with a lower score.

Induction uses medication or medical techniques to start your labor. Natural labor happens on its own. The length of labor that happens without medical intervention varies.

Some people deliver within a few hours of their first contractions. Others have to wait several days before they’re ready to deliver.

When you go into labor naturally, the muscles of your uterus start to contract. Your cervix then widens, softens, and thins to prepare for your baby’s delivery.

During active labor, your cramps become stronger and more frequent. Your cervix widens from 6 cm to 10 cm to accommodate your baby’s head. At the end of this stage, your baby is born.

What labor induction feels like depends on how your doctor induces your labor.

Membrane stripping is slightly uncomfortable, and you should expect some cramping afterward. You’ll feel a slight tug when the doctor breaks your amniotic sac. Afterward, there will be a rush of warm fluid.

Using medication to induce labor produces stronger and faster contractions. You’re more likely to need an epidural when you’re induced than if you start labor without induction.

Unless you or your baby’s health is at risk, waiting for labor to come on its own is the best decision. The biggest benefit is that it reduces the risk of complications from induced labor.

Labor induced without good reason before 39 weeks can lead to more complications than benefits. However, if your doctor induces labor for medical reasons, it could improve both your health and the health of your baby.

Weigh all the benefits versus the risks with your doctor before you decide to have an induction. If your doctor is pressuring you because of scheduling issues, get a second opinion.

Reasons, Types, and Risk Factors

Inducing labor, also known as labor induction, is a procedure where a doctor or midwife uses methods to help you go into labor.

In most cases, it’s best to let labor happen on its own, but there are exceptions. Your doctor may decide to induce you for medical reasons or if you’re 2 or more weeks past your due date.

Talk with your doctor about whether labor induction is right for you.

In a perfect world, you’ll go into labor right on cue at 40 weeks. However, sometimes the process doesn’t go as smoothly as expected, and the baby runs late.

Certain medical problems can make an extended pregnancy risky for you and your baby, including:

- growth problems in the baby

- too little amniotic fluid around the baby

- gestational diabetes

- high blood pressure

- preeclampsia

- a uterine infection

- placental separation from the uterus

- Rh incompatibility

Your doctor may need to induce labor if your water breaks before you start getting contractions. Contractions are a sign that labor has started and your cervix has begun to open. A lack of contractions could mean that your body isn’t preparing for delivery like it should.

Contractions are a sign that labor has started and your cervix has begun to open. A lack of contractions could mean that your body isn’t preparing for delivery like it should.

You might prefer to induce if you live far from a hospital or have a history of delivering quickly. Inducing labor may also be medically necessary after 42 weeks. At this point, the placenta can no longer provide enough oxygen and nutrients for your baby.

Preeclampsia is another reason for inducing labor. Preeclampsia is when you develop high blood pressure and at least one related symptom. If you have high blood pressure during pregnancy, delivering your baby early could prevent complications.

There are a few ways to speed up the process if your baby is behind schedule. The safest and most effective way is to see your doctor. Medications or medical techniques can bring on labor more quickly.

The other option is to try to induce labor on your own. Before you try anything, talk with your doctor or midwife. Make sure the method you’re attempting is safe and that your pregnancy is at the optimal time to induce.

Make sure the method you’re attempting is safe and that your pregnancy is at the optimal time to induce.

Two types of medications induce labor. Drugs called prostaglandins soften the cervix to ready it for delivery. You can take these drugs by mouth, or they can be inserted as a suppository into your vagina.

The second type of drug kick-starts contractions. Pitocin is the most common of these medications. You get it through an IV.

Your cervix needs to be ready for labor or the medications won’t work. Learn the pros and cons of using medication to induce labor.

Medication isn’t the only way to get your labor started. Membrane stripping and breaking your water are two other options.

Stripping the membranes involves the amniotic sac. Your doctor uses their fingers to push the amniotic sac away from the cervix.

To break your water, the doctor pops open the amniotic sac with a small plastic hook. Your baby will then move its way to the top of your cervix in preparation for delivery. You could go into labor days or even hours later.

You could go into labor days or even hours later.

Membrane stripping is generally considered safe, but experts disagree on whether this practice is worth doing.

For a more natural approach without medical intervention, you can try inducing labor on your own. Studies haven’t verified that these methods work, so check with your doctor or midwife before trying any of them.

One of the easiest and safest ways to try inducing labor on your own is to take a walk. The gravity from your movements may help slide your baby down into position. Although a walk may not speed up your pregnancy, it’s good for you in general.

Having sex can also help. Semen contains hormones called prostaglandins, which make your uterus muscles contract. Having an orgasm yourself will also stimulate your uterus.

There’s no evidence that getting more active will help induce labor, but it’s good for your health and pregnancy. Exercise reduces your risk of a C-section and gestational diabetes.

It’s safe for most people to exercise during their pregnancy. Still, it’s a good idea to check with your doctor beforehand. Certain conditions may mean you should avoid exercise completely during pregnancy.

Deep inside the core of a pineapple is an enzyme called bromelain that breaks down proteins. That property makes it a key ingredient in many meat tenderizers.

The theory behind using bromelain for labor induction is that it might break down tissue in your cervix and soften it to prepare for delivery. There’s no scientific evidence that this theory is true, however.

Bromelain might work well on meat, but it’s not very active in the human body. Plus, pineapple could worsen pregnancy heartburn.

While it’s usually best to let nature take its course, inducing labor may be a good idea if there’s a problem with your pregnancy or your baby. If you’re healthy, an induction might help you avoid a C-section.

A 2018 study found that women in their first pregnancy who were induced at 39 weeks were less likely to need a C-section than those who waited. Complication rates didn’t differ between the two groups.

Complication rates didn’t differ between the two groups.

Ask your doctor whether it makes sense to induce at 39 weeks if:

- this is your first pregnancy

- you’re only carrying one baby

- you and your baby are healthy

C-sections can be risky, causing complications like bleeding and infection. While they may be necessary in certain cases, these surgical deliveries can also cause more problems with future pregnancies.

Your labor will be induced in a hospital or birthing center. The process will differ based on which technique your doctor uses to induce labor. Sometimes doctors use a combination of methods.

Depending on the techniques your doctor tries, it can take anywhere from a few hours to several days for your labor to start. Most of the time, induction will lead to vaginal delivery. If this doesn’t work, you might need to try again or have a C-section.

What you can expect depends on the method of induction:

- Prostaglandins come as a suppository that goes into your vagina.

After a few hours, the medication should trigger labor.

After a few hours, the medication should trigger labor. - You’ll get Pitocin through an IV. This chemical stimulates contractions and helps speed up the labor process.

- During amniotic sac rupture, the doctor will place a plastic hook inside your vagina to open up the sac. You may feel a warm rush of water as the sac breaks. When your water breaks, your body’s prostaglandin production increases, which should start your contractions.

The hospital staff will monitor your contractions to see how your labor is progressing. Your baby’s heartbeat is also monitored.

Health concerns and a long pregnancy are reasons why you might consider labor induction. It’s not a decision to make lightly since inducing labor can have serious risks. These include:

- premature birth

- slowed heart rate in the baby

- uterine rupture

- infections in both parent and baby

- excessive bleeding in the parent

- umbilical cord issues

- lung problems in the baby

- stronger contractions

- vision and hearing problems in the baby

- poor lung and brain development

Labor inductions don’t always work. If your induction isn’t successful, you may need a C-section.

If your induction isn’t successful, you may need a C-section.

The drugs and techniques used to induce labor can cause side effects for both you and your baby. Pitocin and other medications that soften your cervix can intensify contractions, making them come faster and closer together.

More intense contractions may be more painful for you. Those faster contractions can also affect your baby’s heart rate. Your doctor might stop giving you the medication if your contractions are coming too quickly.

Rupturing the amniotic sac may cause the umbilical cord to slip out of your vagina before your baby. This is called prolapse. Pressure on the cord can reduce your baby’s oxygen and nutrient supply.

Labor needs to start within about 6 to 12 hours after rupturing your amniotic sac. Not going into labor within that time frame increases the risk of infection for both you and your baby.

The Bishop score is a system your doctor uses to figure out how soon you’ll deliver and whether to induce labor. It gets its name from obstetrician Edward Bishop, who devised the method in 1964.

It gets its name from obstetrician Edward Bishop, who devised the method in 1964.

Your doctor will calculate your score from the results of a physical exam and ultrasound. The score is based on factors like:

- how far your cervix has opened (dilated)

- how thin your cervix is (effacement)

- how soft your cervix is

- where in the birth canal your baby’s head is (fetal station)

A score of 8 or above means you’re close to starting labor and that induction should work well. Your odds of a successful induction go down with a lower score.

Induction uses medication or medical techniques to start your labor. Natural labor happens on its own. The length of labor that happens without medical intervention varies.

Some people deliver within a few hours of their first contractions. Others have to wait several days before they’re ready to deliver.

When you go into labor naturally, the muscles of your uterus start to contract. Your cervix then widens, softens, and thins to prepare for your baby’s delivery.

During active labor, your cramps become stronger and more frequent. Your cervix widens from 6 cm to 10 cm to accommodate your baby’s head. At the end of this stage, your baby is born.

What labor induction feels like depends on how your doctor induces your labor.

Membrane stripping is slightly uncomfortable, and you should expect some cramping afterward. You’ll feel a slight tug when the doctor breaks your amniotic sac. Afterward, there will be a rush of warm fluid.

Using medication to induce labor produces stronger and faster contractions. You’re more likely to need an epidural when you’re induced than if you start labor without induction.

Unless you or your baby’s health is at risk, waiting for labor to come on its own is the best decision. The biggest benefit is that it reduces the risk of complications from induced labor.

Labor induced without good reason before 39 weeks can lead to more complications than benefits. However, if your doctor induces labor for medical reasons, it could improve both your health and the health of your baby.

Weigh all the benefits versus the risks with your doctor before you decide to have an induction. If your doctor is pressuring you because of scheduling issues, get a second opinion.

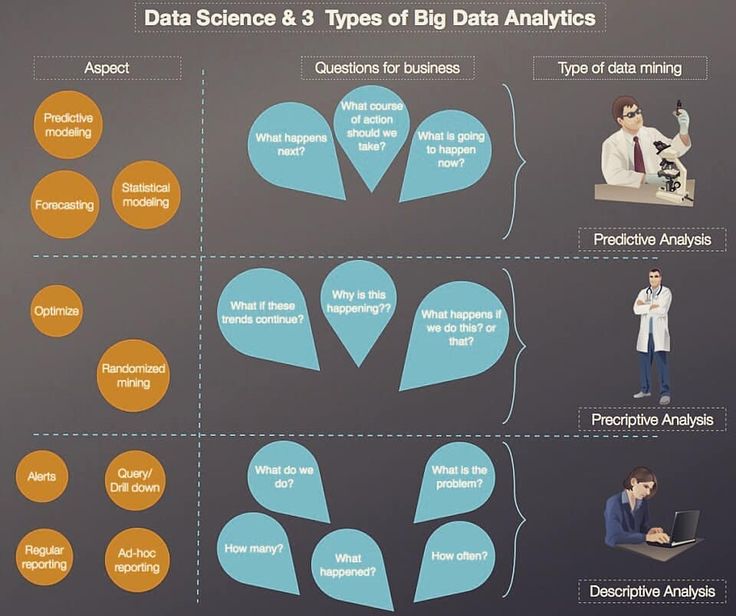

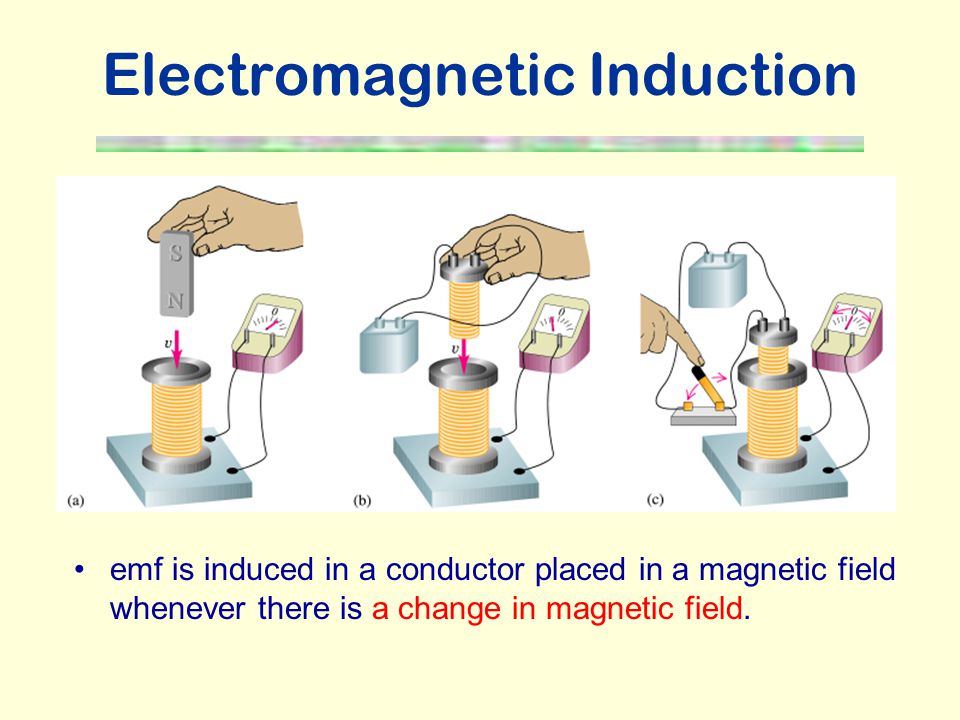

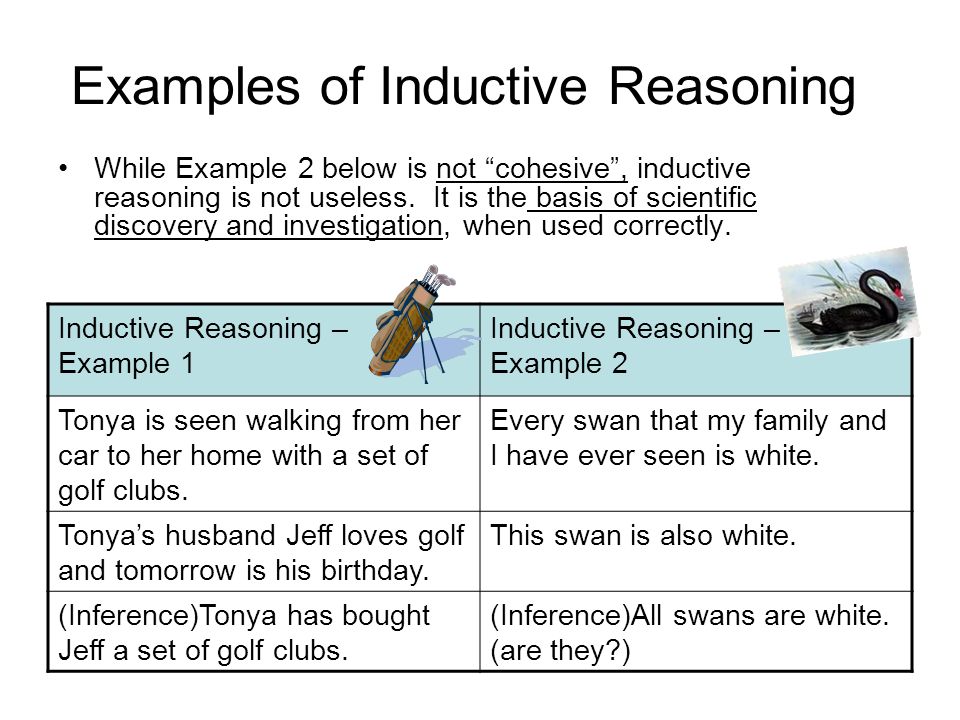

| Induction is a cognitive procedure by means of which a statement generalizing them is deduced from a comparison of the facts at hand. In scientific search (see Methods of scientific knowledge) induction involves the movement of knowledge from single statements about individual facts to statements of a more general nature. In logic (see Logic), the term "induction" is used as a synonym for the more precise, but more cumbersome, term "inductive reasoning" and is understood in a narrower sense: as a conclusion in which a general conclusion is built on the basis of particular premises. At the same time, sendings can confirm or imply truth, but do not guarantee its receipt. This is where induction fundamentally differs from deduction (see Deduction), by means of which true conclusions are always obtained from true premises, subject to the rules of logical inference. The most widely used kind of inductive reasoning is enumerative reasoning, i.e. reasoning containing a transition from premises stating that all known objects from a certain collection A have the property P and unknown - objects from A have P . Another type of inductive reasoning that is widely used is reasoning that contains a transition from premises stating that some object A had the property P at every point in time before the present, to the conclusion that A will have P at the future. Induction is widely used in all areas of scientific knowledge, playing an important role in the construction of empirical knowledge and the transition from empirical to theoretical knowledge. In science, the basis of induction is experience, experiment and observation, during which individual facts are collected. Then, studying these facts, analyzing them, the researcher establishes common and recurring features of a number of phenomena included in a certain class. Inductive reasoning distinguishes complete and incomplete induction:

These varieties of incomplete induction play an extremely important role in scientific knowledge. Incomplete induction allows you to reduce the scientific search and come to general provisions, the disclosure of patterns, without waiting until all the phenomena of this class are studied in detail. However, it also includes a significant limitation, which consists in the fact that the conclusion of incomplete induction most often does not provide reliable knowledge. Since induction is closely connected with the development of experimental knowledge, it began to be used already in ancient times, although theoretically its simplest forms began to be analyzed only in ancient philosophy, in particular by Socrates, who introduced the concept of inductive reasoning, and Aristotle, who considered them as auxiliary means of justification sendings syllogisms (see Syllogism). In Aristotle, the understanding of induction is associated with the generalization of observations and means, in essence, a method of inference through which the ascent from the particular to the general is made. This Aristotelian view was adopted by the philosophers of the Epicurean school, who defended induction against the Stoics as the only authoritative method of proving the laws of nature. Further development of the theory of induction is noted only in modern times, when the active growth of science, due to the accumulation, generalization and systematization of extensive empirical material, raised the question of studying the methods of scientific discovery, and the types of inductive reasoning themselves began to be studied for their reliability. From a philosophical point of view, the most interesting problem is the justification of induction - finding a rational basis for recognizing the legitimacy of inductive reasoning. The importance of the problem is due to the importance of inductive reasoning for modern science. Its successful solution involves finding an answer to the question on what basis we recognize some of the inductive reasoning as acceptable, despite the fact that in any inductive reasoning the truth of the premises does not guarantee the truth of the conclusion. All answers proposed since D. Hume, who raised this question, have been unsuccessful - every attempt to justify induction offered up to the present moment implicitly assumed the legitimacy of induction. At present, the consideration of the problem of induction, proposed by P. Strawson, who claims that the project of substantiating induction is self-contradictory, enjoys a certain popularity. According to Strawson, justifying induction is tantamount to giving inductive reasoning the status of deductive reasoning. | |

|

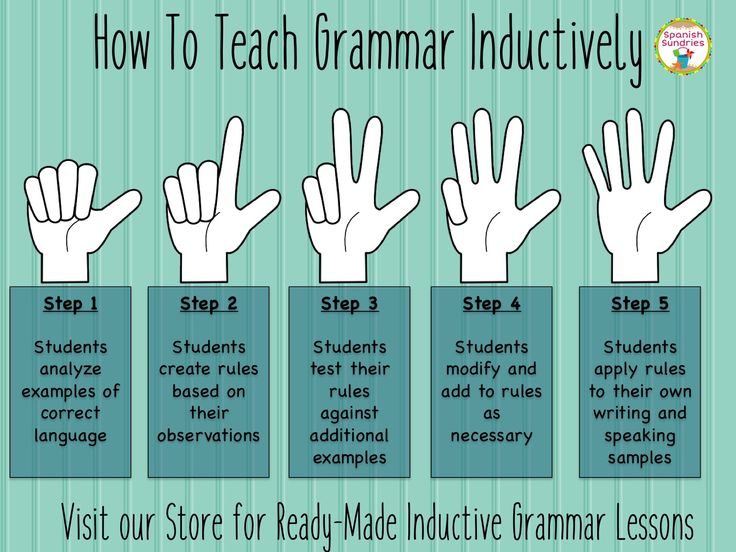

Induction. Types of induction.

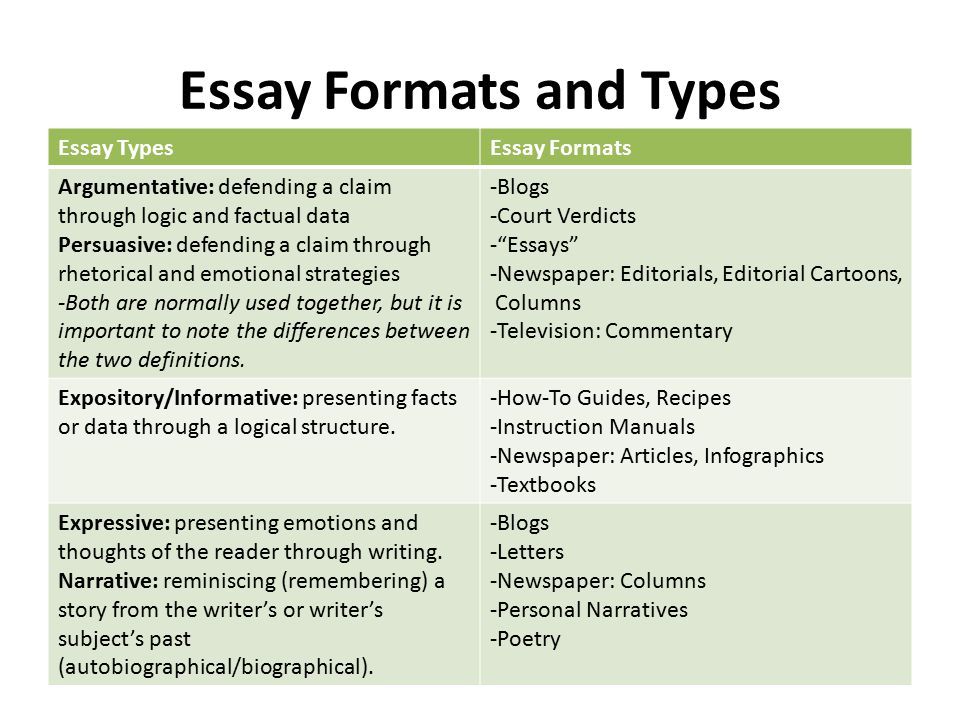

Induction (lat. inductio - guidance) - process transition-based inference from the private to the general. inductive inference binds private premises with a conclusion not strictly through the laws of logic, but rather through some factual, psychological or mathematical representations.

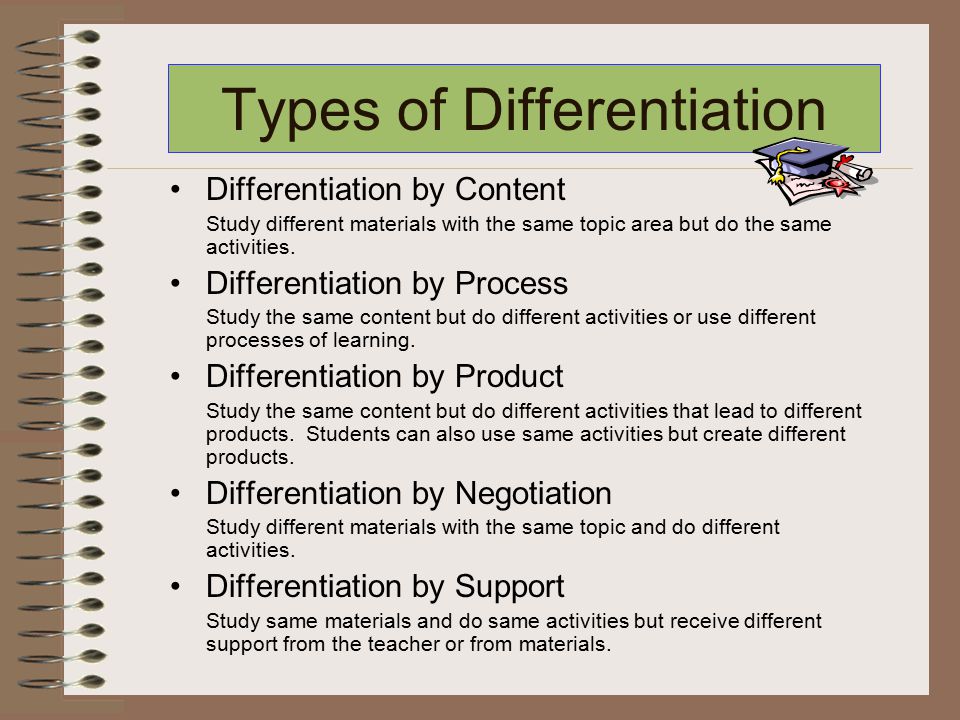

Distinguish full induction - a method of proof, under which the assertion is proved for a finite number of special cases, exhausting all possibilities, and incomplete induction - observations of individual in particular cases lead to a hypothesis, which, of course, needs to be proven. Also used for proof method of mathematical induction.

For complete induction must be performed trace condition:

-

Exactly know the number of objects or phenomena, subject to review

-

Make sure, that the attribute belongs to each element this class

-

Number elements of the class under study should be small

incomplete induction is used when when we, in the first place, cannot consider all elements of the class we are interested in phenomena; secondly, if the number of objects either infinite or finite, but large enough; third, when consideration destroys the object (ex: All trees have roots)

By ways to substantiate the conclusion incomplete induction is divided into trace three kinds:

Induction via simple transfer (popular)

On based on the repetition of the same the same feature in a number of homogeneous objects and the absence of a contradictory case the general conclusion is that all objects of this kind have this sign.

For example, Based on this induction, it was previously believed that that all swans are white, until did not meet black swans in Australia.

This induction gives a probable conclusion, but not reliable.

characteristic and a very common mistake. is a “hasty generalization”

IN induction through analysis and selection of facts trying to rule out randomness generalizations, as they are studied systematically selected, most typical items - varied in time, method receipt and existence and others conditions.

So calculate the average yield of the field, judge the germination of seeds, the quality large quantities of goods, etc.

Scientific induction

Scientific induction is such a conclusion, in which, on the basis of knowledge necessary features or necessary connection of part of the objects of the class is done general conclusion about all subjects class.

Scientific induction, as well as full induction and mathematical induction, gives reliable conclusion.

Reliability conclusions of scientific induction, although it and does not cover all subjects studied class, but only a part of them (and, moreover, small), due to the fact that takes into account the most important of the necessary connections - causation.

Analogy This is non-deductive reasoning which the judgment of belonging attribute to some object is displayed based on its resemblance to another object.

Analogy represents a transition to knowledge the same degree of generality, that is, from singular judgments to singular ones, from private - to private, from general - to general.

foundation inference by analogy serves similarity (analogy) of objects, their properties and relationships. Item similarity determined by two factors:

IN inferences by analogy are used the following concepts:

- analogy sample - object, sign which is transferred to another object;

- the subject of analogy is the object on which the sign is transferred;

- analogy terms are a pattern and the subject of analogy;

- transferable sign - a sign, which is transferred from the sample to the subject;

- the basis of the analogy is a sign, common to both terms analogies and serving as the basis for transfer of the trait we are interested in.

On this basis, he builds an inductive conclusion, the premises of which are judgments about single objects and phenomena with an indication of their recurring feature, and a judgment about a class that includes these objects and phenomena. As a conclusion, a judgment is obtained in which the attribute identified in a set of single objects is attributed to the entire class. The value of inductive inferences lies in the fact that they provide a transition from single facts to general provisions, allow you to detect dependencies between phenomena, build empirically based hypotheses, and come to generalizations.

On this basis, he builds an inductive conclusion, the premises of which are judgments about single objects and phenomena with an indication of their recurring feature, and a judgment about a class that includes these objects and phenomena. As a conclusion, a judgment is obtained in which the attribute identified in a set of single objects is attributed to the entire class. The value of inductive inferences lies in the fact that they provide a transition from single facts to general provisions, allow you to detect dependencies between phenomena, build empirically based hypotheses, and come to generalizations.  The conclusions of complete induction are deductive in the sense that the conclusion in them follows from the premises with logical necessity: if the premises are true, applying the known rules of logic, we cannot obtain a false conclusion. Full induction is applicable in cases where the class of objects under study is observable and all objects of this class can be enumerated. Thus, it implies the study of each of the objects included in the class, and on this basis, finding their common characteristics. However, in some cases there is simply no need to consider absolutely all objects of a particular class, in other cases it is impossible to do this due to the immensity of the class of phenomena being studied or due to the limitations of human practice. In such situations, incomplete induction is used.

The conclusions of complete induction are deductive in the sense that the conclusion in them follows from the premises with logical necessity: if the premises are true, applying the known rules of logic, we cannot obtain a false conclusion. Full induction is applicable in cases where the class of objects under study is observable and all objects of this class can be enumerated. Thus, it implies the study of each of the objects included in the class, and on this basis, finding their common characteristics. However, in some cases there is simply no need to consider absolutely all objects of a particular class, in other cases it is impossible to do this due to the immensity of the class of phenomena being studied or due to the limitations of human practice. In such situations, incomplete induction is used.  Thus, it implies the study of a limited number of objects of any particular class, since, as a rule, the number of all cases is practically incomprehensible, and a theoretical proof for an infinite number of these cases is impossible. Incomplete induction is no longer a logically justified reasoning, since from the point of view of logic only such conclusions are valid, for which no new information is required, except for that contained in the premises, but the conclusion of incomplete induction always says more than its premises can say . This, in fact, is the cognitive meaning of induction - the abstract work of thought helps to obtain new knowledge with a lack of existing [practical] knowledge. Incompleteness of induction can be determined not only by the number of premises (incompleteness with respect to the number of premises), but also by their nature (incompleteness with respect to the nature of premises).

Thus, it implies the study of a limited number of objects of any particular class, since, as a rule, the number of all cases is practically incomprehensible, and a theoretical proof for an infinite number of these cases is impossible. Incomplete induction is no longer a logically justified reasoning, since from the point of view of logic only such conclusions are valid, for which no new information is required, except for that contained in the premises, but the conclusion of incomplete induction always says more than its premises can say . This, in fact, is the cognitive meaning of induction - the abstract work of thought helps to obtain new knowledge with a lack of existing [practical] knowledge. Incompleteness of induction can be determined not only by the number of premises (incompleteness with respect to the number of premises), but also by their nature (incompleteness with respect to the nature of premises).  The fixation of a new feature in a number of objects occurs here, as a rule, without a preliminary research plan: having found a similar feature in the first objects of a certain class that have come across and not having encountered a single contradictory case, they transfer the indicated feature to the entire class of objects. The absence of a contradictory case is the main reason for accepting an inductive inference. The discovery of such a case refutes the inductive generalization. The conclusion obtained by induction through a simple enumeration has a relatively low degree of certainty, and with continued research based on expanding the class of cases studied, it can often turn out to be erroneous. Therefore, popular induction can be used in scientific research when putting forward first and approximate hypotheses. It is often resorted to at the first stages of acquaintance with a new class of objects, but in general it cannot serve as a reliable basis for inductive generalizations obtained by science.

The fixation of a new feature in a number of objects occurs here, as a rule, without a preliminary research plan: having found a similar feature in the first objects of a certain class that have come across and not having encountered a single contradictory case, they transfer the indicated feature to the entire class of objects. The absence of a contradictory case is the main reason for accepting an inductive inference. The discovery of such a case refutes the inductive generalization. The conclusion obtained by induction through a simple enumeration has a relatively low degree of certainty, and with continued research based on expanding the class of cases studied, it can often turn out to be erroneous. Therefore, popular induction can be used in scientific research when putting forward first and approximate hypotheses. It is often resorted to at the first stages of acquaintance with a new class of objects, but in general it cannot serve as a reliable basis for inductive generalizations obtained by science. Such generalizations are built mainly on the basis of scientific induction.

Such generalizations are built mainly on the basis of scientific induction.

To a lesser extent, this applies to scientific induction, some varieties of which give reliable conclusions, but entirely to popular induction. Knowledge obtained in the framework of incomplete induction is usually problematic, probabilistic. This gives rise to the possibility of numerous errors, which are the result of hasty generalizations. This kind of generalization is especially characteristic of the early stages of scientific research. The problematic nature of most inductive conclusions requires their repeated verification by practice, comparison with the experience of the consequences derived from the inductive generalization. As these consequences coincide with the result of the experiment, the degree of reliability of the inductive conclusion increases. In this process, the justification of knowledge obtained by induction necessarily implies a movement from inductive generalizations to one or another particular case. Such a conclusion is already a deductive reasoning. Thus, induction is supplemented by deduction, which ensures the transition from probabilistic to reliable knowledge.

To a lesser extent, this applies to scientific induction, some varieties of which give reliable conclusions, but entirely to popular induction. Knowledge obtained in the framework of incomplete induction is usually problematic, probabilistic. This gives rise to the possibility of numerous errors, which are the result of hasty generalizations. This kind of generalization is especially characteristic of the early stages of scientific research. The problematic nature of most inductive conclusions requires their repeated verification by practice, comparison with the experience of the consequences derived from the inductive generalization. As these consequences coincide with the result of the experiment, the degree of reliability of the inductive conclusion increases. In this process, the justification of knowledge obtained by induction necessarily implies a movement from inductive generalizations to one or another particular case. Such a conclusion is already a deductive reasoning. Thus, induction is supplemented by deduction, which ensures the transition from probabilistic to reliable knowledge.

Of great importance in this regard were the works of F. Bacon, who began a systematic study of inductive procedures, considering them as the only scientific way of knowing and contrasting induction with speculative reasoning. Since the methods of Aristotelian syllogistic and induction through a simple enumeration of confirming cases could not be used to analyze empirical generalizations, Bacon, in contrast to Aristotle's Organon, creates his New Organon (1620), in which he sets out the "canons of induction" as methods for discovering new truths in science. Later, the theory of induction was developed in the works of J. St. Mill, who proposed five methods of inductive reasoning (Bacon-Mill canons of induction), through which conclusions are drawn about causal relationships between phenomena: the method of similarity; difference method; combined method of similarity and difference; residual method; concomitant change method. These inductive methods are known examples of plausible reasoning (see Reasoning plausible).

Of great importance in this regard were the works of F. Bacon, who began a systematic study of inductive procedures, considering them as the only scientific way of knowing and contrasting induction with speculative reasoning. Since the methods of Aristotelian syllogistic and induction through a simple enumeration of confirming cases could not be used to analyze empirical generalizations, Bacon, in contrast to Aristotle's Organon, creates his New Organon (1620), in which he sets out the "canons of induction" as methods for discovering new truths in science. Later, the theory of induction was developed in the works of J. St. Mill, who proposed five methods of inductive reasoning (Bacon-Mill canons of induction), through which conclusions are drawn about causal relationships between phenomena: the method of similarity; difference method; combined method of similarity and difference; residual method; concomitant change method. These inductive methods are known examples of plausible reasoning (see Reasoning plausible). Subsequently, they received a number of refinements in the works of other researchers. However, with the help of the "canons of induction" it was possible to make only relatively simple empirical generalizations and establish logical relationships between the observed properties of phenomena. When science began to explore deeper laws that reveal the essence and internal mechanisms of phenomena, it became obvious that empirical methods based on induction are not able to do this, if only because it requires an appeal to abstract, theoretical concepts. In this regard, the view of induction changed radically, and instead of the logic of discovery, it began to be considered as a method of testing and substantiating hypotheses. Within of the hypothetical-deductive method (see Hypothetical-deductive method), it is the empirically verifiable consequences of a hypothesis that can be tested and confirmed with the help of inductively established facts. This view of induction found its most striking expression in the neo-positivist concept, in which the context of justification is sharply opposed to the context of discovery.

Subsequently, they received a number of refinements in the works of other researchers. However, with the help of the "canons of induction" it was possible to make only relatively simple empirical generalizations and establish logical relationships between the observed properties of phenomena. When science began to explore deeper laws that reveal the essence and internal mechanisms of phenomena, it became obvious that empirical methods based on induction are not able to do this, if only because it requires an appeal to abstract, theoretical concepts. In this regard, the view of induction changed radically, and instead of the logic of discovery, it began to be considered as a method of testing and substantiating hypotheses. Within of the hypothetical-deductive method (see Hypothetical-deductive method), it is the empirically verifiable consequences of a hypothesis that can be tested and confirmed with the help of inductively established facts. This view of induction found its most striking expression in the neo-positivist concept, in which the context of justification is sharply opposed to the context of discovery. The task of the logic and philosophy of science is reduced solely to the substantiation of new knowledge, while the process of discovery is entirely related to the psychology of scientific creativity. Since the conclusion of induction does not logically follow from the premises, only a probabilistic relationship can be established between them, which is defined as the semantic degree of confirmation of the conclusion by its premises. Hence, the task of induction is not to invent rules for the discovery of new scientific truths, but to search for objective criteria for confirming hypotheses by their empirical premises, and if possible, then determining the quantitative degree of confirmation. From this point of view, other non-deductive reasoning (analogy, statistical inference) can also be attributed to induction in the sense that their conclusions are only probabilistic in nature and can be analyzed within the framework of a broader probabilistic logic. However, this leaves behind the heuristic function of induction, which is widely used to obtain generalizations from facts.

The task of the logic and philosophy of science is reduced solely to the substantiation of new knowledge, while the process of discovery is entirely related to the psychology of scientific creativity. Since the conclusion of induction does not logically follow from the premises, only a probabilistic relationship can be established between them, which is defined as the semantic degree of confirmation of the conclusion by its premises. Hence, the task of induction is not to invent rules for the discovery of new scientific truths, but to search for objective criteria for confirming hypotheses by their empirical premises, and if possible, then determining the quantitative degree of confirmation. From this point of view, other non-deductive reasoning (analogy, statistical inference) can also be attributed to induction in the sense that their conclusions are only probabilistic in nature and can be analyzed within the framework of a broader probabilistic logic. However, this leaves behind the heuristic function of induction, which is widely used to obtain generalizations from facts.

At the same time, the main value of inductive reasoning is that - unlike deductively correct reasoning - they allow us to receive new information; thus, justifying induction is tantamount to saying that inductive reasoning, contrary to evidence, does not lead to new information, which, according to Strawson, is absurd. In recent years, attempts have been made to supplement the induction with some premises or permissive procedures that provide more reliable conclusions in specific areas of research. In the same direction, an analysis of reproductive reasoning is carried out, where the search goes not from hypotheses to consequences, but, on the contrary, from consequences to hypotheses. Such techniques reduce the risk of error during induction, but in principle, induction - excluding the full and mathematical - always remains a probabilistic inference. In modern logic and philosophy of science, interest in the theory of induction is supported by applied research.

At the same time, the main value of inductive reasoning is that - unlike deductively correct reasoning - they allow us to receive new information; thus, justifying induction is tantamount to saying that inductive reasoning, contrary to evidence, does not lead to new information, which, according to Strawson, is absurd. In recent years, attempts have been made to supplement the induction with some premises or permissive procedures that provide more reliable conclusions in specific areas of research. In the same direction, an analysis of reproductive reasoning is carried out, where the search goes not from hypotheses to consequences, but, on the contrary, from consequences to hypotheses. Such techniques reduce the risk of error during induction, but in principle, induction - excluding the full and mathematical - always remains a probabilistic inference. In modern logic and philosophy of science, interest in the theory of induction is supported by applied research.  Analysts first and second. - M., 1952.

Analysts first and second. - M., 1952.  - "Questions of Philosophy", 1968, No. 9.

- "Questions of Philosophy", 1968, No. 9.  - Ivanovo, 1956.

- Ivanovo, 1956.  — Amsterdam, 1986.

— Amsterdam, 1986.