Treating chlamydia during pregnancy

Screening and Treatment for Sexually Transmitted Infections in Pregnancy

BARBARA A. MAJERONI, MD, AND SREELATHA UKKADAM, MBBS

Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(2):265-270

Patient information: See related handout on sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Many sexually transmitted infections are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends screening all pregnant women for human immunodeficiency virus infection as early as possible. Treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy can reduce transmission to the fetus. Chlamydia screening is recommended for all women at the onset of prenatal care, and again in the third trimester for women who are younger than 25 years or at increased risk. Azithromycin has been shown to be safe in pregnant women and is recommended as the treatment of choice for chlamydia during pregnancy. Screening for gonorrhea is recommended in early pregnancy for those who are at risk or who live in a high-prevalence area, and again in the third trimester for patients who continue to be at risk. The recommended treatment for gonorrhea is ceftriaxone 125 mg intramuscularly or cefixime 400 mg orally. Hepatitis B surface antigen and serology for syphilis should be checked at the first prenatal visit. Benzathine penicillin G remains the treatment for syphilis. Screening for genital herpes simplex virus infection is by history and examination for lesions, with diagnosis of new cases by culture or polymerase chain reaction assay from active lesions.

Routine serology is not recommended for screening. The oral antivirals acyclovir and valacyclovir can be used in pregnancy. Suppressive therapy from 36 weeks' gestation reduces viral shedding at the time of delivery in patients at risk of active lesions. Screening for trichomoniasis or bacterial vaginosis is not recommended for asymptomatic women because current evidence indicates that treatment does not improve pregnancy outcomes.

Routine serology is not recommended for screening. The oral antivirals acyclovir and valacyclovir can be used in pregnancy. Suppressive therapy from 36 weeks' gestation reduces viral shedding at the time of delivery in patients at risk of active lesions. Screening for trichomoniasis or bacterial vaginosis is not recommended for asymptomatic women because current evidence indicates that treatment does not improve pregnancy outcomes.

Infections during pregnancy affect the mother and often the child, either in utero or at the time of delivery. Many infections have been linked with increased risks of premature delivery and low birth weight, and associated morbidity and mortality. Because of these risks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended screening for some sexually transmitted infections (STIs) at the first prenatal visit, then again in the third trimester for mothers at high risk (Table 1). 1 The CDC has also published recommendations for the treatment of STIs during pregnancy.1

1 The CDC has also published recommendations for the treatment of STIs during pregnancy.1

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin (Zithromax) is an effective treatment for chlamydia during pregnancy. | B | 5 | No long-term safety studies have been performed. |

| Intramuscular ceftriaxone (Rocephin) and oral cefixime (Suprax) are similar in effectiveness for gonorrhea during pregnancy. | B | 6, 8 | Spectinomycin (Trobicin; not available in the United States) is also effective but is painful to use. |

Initiation of acyclovir (Zovirax) or valacyclovir (Valtrex) treatment at 36 weeks' gestation reduces the recurrence of genital herpes lesions and the number of cesarian deliveries performed because of genital herpes. | A | 10, 11 | In patients with known herpes. Serologic screening is not advocated. |

| Penicillin is effective in the prevention of congenital syphilis. | A | 20 | Needs to be found and treated early. Screening should be carried out at the first visit. |

| Treatment of trichomoniasis does not reduce the incidence of preterm birth. | A | 21 | Screening in asymptomatic women is not recommended. |

| Condition | Screening recommended? | Preferred test |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial vaginosis* | No | — |

| Chlamydia | Yes: all pregnant women | NAAT |

| Gonorrhea | Yes: women who are at risk† or living in a high-prevalence area | NAAT or culture on Thayer-Martin media |

| Hepatitis B | Yes: all pregnant women | HBsAg serology |

| Hepatitis C | Yes: women who are at high risk‡ | Anti-HCV |

| Herpes | No (culture lesions if present) | Culture, PCR |

| HIV | Yes: all pregnant women | EIA, Western blot |

| HPV | No | — |

| Syphilis | Yes: all pregnant women | RPR or VDRL |

| Trichomoniasis | No | — |

Screening

All women in the United States should be screened for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection as early as possible during pregnancy. If the patient declines testing, the physician should discuss her objections and continue to strongly encourage testing. Other screening tests that are recommended for all pregnant women include those for hepatitis B, syphilis, and Chlamydia trachomatis. Women at risk should be tested for Neisseria gonorrhea and hepatitis C. Evidence does not support routine screening for bacterial vaginosis.

If the patient declines testing, the physician should discuss her objections and continue to strongly encourage testing. Other screening tests that are recommended for all pregnant women include those for hepatitis B, syphilis, and Chlamydia trachomatis. Women at risk should be tested for Neisseria gonorrhea and hepatitis C. Evidence does not support routine screening for bacterial vaginosis.

Women younger than 25 years and those who are at risk of chlamydia (e.g., those who have multiple sex partners) should be rescreened in the third trimester.1 Women who continue to be at risk of gonorrhea should also be rescreened in the third trimester.1

When infection is detected, the physician must inform the mother, ensure adequate and safe treatment, and advise partner notification and treatment. In many states, cases of STI must be reported to the health department. Physicians should counsel the patient to use condoms and avoid sexual contact until her partner has been treated.

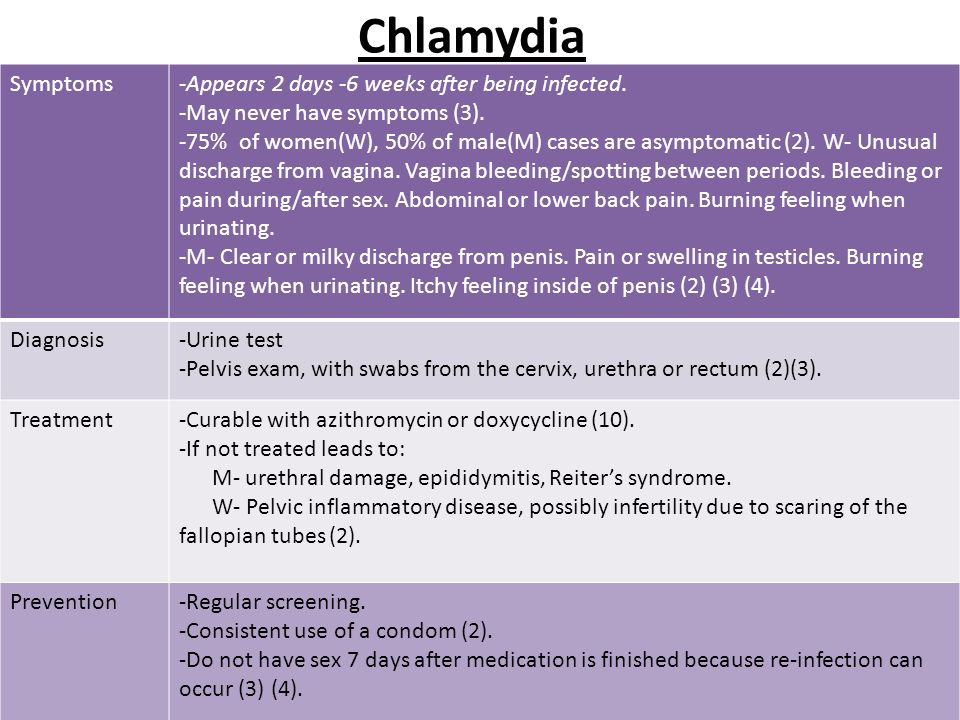

Chlamydia

C. trachomatis is the most common sexually transmitted bacterial pathogen in the United States, and as many as 5 to 15 percent of pregnant women are infected.2 Mother-to-child transmission of C. trachomatis can occur at the time of birth and may result in ophthalmia neonatorum or pneumonitis in the newborn, or postpartum endometritis in the mother. Some reports have linked chlamydia to low birth weight and preterm birth, but one study found no such association.2

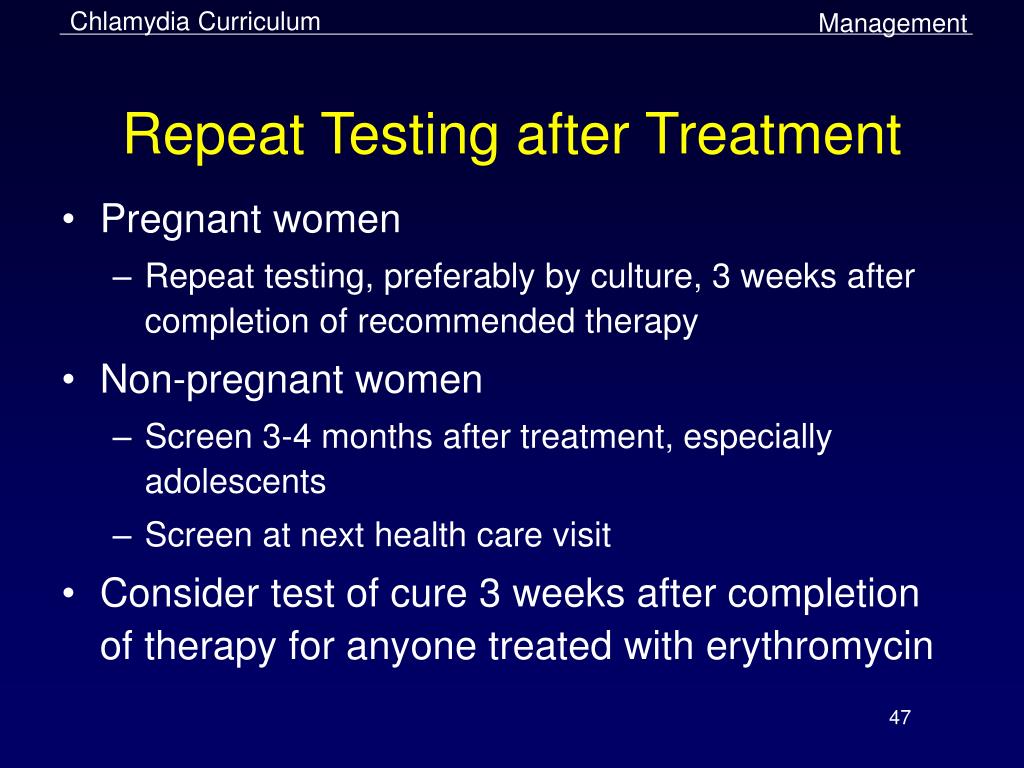

The nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) is the preferred test for chlamydia because of its high sensitivity and specificity and its use on specimens obtained noninvasively.3 It can be performed using cervical or urine specimens. Nonamplified nonculture tests, such as the DNA probe test, remain an option when the NAAT is not available or is too expensive. Repeat testing three weeks after completion of therapy is recommended for pregnant women.1

Tetracyclines are contraindicated in pregnancy because of the risk of bone and tooth abnormalities. Amoxicillin (500 mg orally three times per day for seven days) appears to be effective for microbiologic cure, but there are few data on its long-term effectiveness for neonatal infection.4 A randomized trial comparing azithromycin (Zithromax) in a single 1-g dose to erythromycin in a dosage of 500 mg every six hours for seven days found enhanced compliance, fewer gastrointestinal side effects, and equivalent effectiveness with azithromycin.5 No long-term safety studies on azithromycin in pregnancy have been published; however, azithromycin is U.S. Food and Drug Administration pregnancy category B and is recommended as first-line treatment for chlamydia in pregnancy.1 The single 1-g oral dose can be given in the office when compliance is a concern.

Amoxicillin (500 mg orally three times per day for seven days) appears to be effective for microbiologic cure, but there are few data on its long-term effectiveness for neonatal infection.4 A randomized trial comparing azithromycin (Zithromax) in a single 1-g dose to erythromycin in a dosage of 500 mg every six hours for seven days found enhanced compliance, fewer gastrointestinal side effects, and equivalent effectiveness with azithromycin.5 No long-term safety studies on azithromycin in pregnancy have been published; however, azithromycin is U.S. Food and Drug Administration pregnancy category B and is recommended as first-line treatment for chlamydia in pregnancy.1 The single 1-g oral dose can be given in the office when compliance is a concern.

Gonorrhea

N. gonorrhea can be transmitted to the newborn from the mother's genital tract at the time of birth and can cause ophthalmia neonatorum, systemic neonatal infection, maternal endometritis, or pelvic infection. The risk of transmission from an infected mother to her infant is between 30 and 47 percent.6

The risk of transmission from an infected mother to her infant is between 30 and 47 percent.6

Screening can be performed with a culture on Thayer-Martin media, which is recommended in a population with a low prevalence of infection.3 Nucleic acid hybridization tests of cervical specimens and NAATs of cervical specimens or urine are also used, with NAATs being the most sensitive and specific.7 Culture is the most widely available test and has the advantage of providing antimicrobial susceptibility. A repeat test is recommended in the third trimester for those at continued risk.1

A Cochrane review of treatment for gonorrhea in pregnancy concluded that ceftriaxone (Rocephin) 125 mg intramuscularly and spectinomycin (Trobicin) 2 g intramuscularly have similar cure rates to oral amoxicillin plus probenecid.6 One randomized trial found cefixime (Suprax) 400 mg orally to be as effective as ceftriaxone 125 mg intramuscularly for the treatment of gonorrhea in pregnancy. 8 The CDC recommends either of these as the treatment of choice for gonorrhea.1 There have been times when cefixime has been in short supply. Spectinomycin is rarely used because of the high volume required for the intramuscular dose.

8 The CDC recommends either of these as the treatment of choice for gonorrhea.1 There have been times when cefixime has been in short supply. Spectinomycin is rarely used because of the high volume required for the intramuscular dose.

Hepatitis

The CDC recommends routine screening of all pregnant women for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) to detect maternal disease and avoid perinatal transmission. HBsAg is present in acute and chronic infections. The presence of immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis B core antigen is diagnostic of acute or recently acquired infection. HBsAg is the first detectable virologic marker for hepatitis B infection, often appearing before liver transaminases are elevated, but it may become undetectable after one to two months.

Pregnant women seeking STI treatment who have not previously been vaccinated should be vaccinated against hepatitis B. Infants of HBsAg-positive mothers should receive hepatitis B immune globulin as well as hepatitis B vaccine at birth. Further information on treating women with hepatitis B and their infants can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5416.pdf.

Further information on treating women with hepatitis B and their infants can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5416.pdf.

Routine screening for hepatitis C in pregnancy is not recommended.1 Women with known risk factors (e.g., history of injection drug use, blood transfusion or organ transplant before 1992) should be offered counseling and testing for hepatitis C antibodies.1 Approximately 5 percent of infants whose mothers are infected with hepatitis C become infected.1 Breastfeeding does not appear to transmit hepatitis C.1

Herpes Simplex Virus

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is an extremely common STI that has potentially devastating effects on perinatally infected neonates. The risk of transmission is 30 to 50 percent higher among women who acquire genital HSV near the time of delivery. The clinical diagnosis of genital herpes during pregnancy in HIV-infected women may be a risk factor for perinatal HIV infection. 9

9

Screening is performed clinically by visualization of lesions or by patient history. Diagnosis is by culture or polymerase chain reaction assay of an active lesion. Routine serologic testing is not recommended.1

Administration of acyclovir (Zovirax) or valacyclovir (Valtrex) starting at 36 weeks' gestation has been shown to significantly reduce the recurrence of herpes simplex lesions and viral shedding at the time of delivery in patients at risk of active lesions, and to reduce the number of cesarean deliveries performed because of genital herpes.10–12 Acyclovir therapy has been shown to be cost-effective and is the CDC's recommended treatment for HSV infection during pregnancy.1,13 The CDC also recommends using acyclovir during pregnancy for women who have recurrent genital herpes near term.1

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

The U.S. Public Health Service and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend that all pregnant women in the United States be tested for HIV infection, ideally at the first prenatal visit. 14,15 Testing should be voluntary and free of coercion. Women who are at high risk (e.g., those who have a history of sexually transmitted diseases, who exchange sex for money or drugs, who have multiple sex partners during pregnancy, who use illicit drugs, or who have sex partners who are HIV positive or at high risk) should be retested in the third trimester. Testing is done with an enzyme immunoassay for antibodies against HIV. Positive test results are confirmed with a Western blot or an immunofluorescence assay to rule out false-positive results.

14,15 Testing should be voluntary and free of coercion. Women who are at high risk (e.g., those who have a history of sexually transmitted diseases, who exchange sex for money or drugs, who have multiple sex partners during pregnancy, who use illicit drugs, or who have sex partners who are HIV positive or at high risk) should be retested in the third trimester. Testing is done with an enzyme immunoassay for antibodies against HIV. Positive test results are confirmed with a Western blot or an immunofluorescence assay to rule out false-positive results.

Goals of therapy are to control maternal infection and reduce transmission to the fetus. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is used during pregnancy to suppress viral load,14,16 with the exception of efavirenz (Sustiva), which is pregnancy category D because of teratogenicity in animal studies. Elective cesarean delivery at 38 weeks reduces the risk of transmission in women not taking antiretrovirals or taking only zidovudine (Retrovir). 17 HIV treatment guidelines are available on the AIDSinfo Web site at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/default.aspx. Because concepts relevant to HIV management evolve rapidly, the recommendations are regularly updated.

17 HIV treatment guidelines are available on the AIDSinfo Web site at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/default.aspx. Because concepts relevant to HIV management evolve rapidly, the recommendations are regularly updated.

Human Papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is extremely common and often resolves spontaneously. Testing for HPV is considered useful in triage of women with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance on Papanicolaou smear. Treatment is not recommended in women with no cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions or genital warts.1

Diagnosis of genital warts is made by visual inspection. Biopsy may be needed if the diagnosis is uncertain, if the warts do not respond to standard treatment, or if they are pigmented, ulcerated, fixed, or bleeding. Because genital warts can proliferate and become friable during pregnancy, many specialists recommend their removal.1 Podofilox (Condylox), imiquimod (Aldara), and podophyllin are not recommended during pregnancy. Trichloroacetic acid 80–90% applied by a health care professional weekly has been used safely in pregnancy.

Trichloroacetic acid 80–90% applied by a health care professional weekly has been used safely in pregnancy.

Syphilis

Treponema pallidum, the cause of syphilis, is highly transmissible, even in the absence of any specific symptoms or clinical findings.18 Maternal syphilis has been associated with complications such as hydramnios, spontaneous abortion, and preterm delivery. Fetal complications such as fetal syphilis, fetal hydrops, prematurity, fetal distress, and stillbirth also occur. Neonatal complications can include congenital syphilis, neonatal death, and late sequelae.19

Screening is performed with a blood test—the rapid plasma reagin or Venereal Disease Research Laboratories test—and confirmed with a fluorescent treponemal antibody serology and T. pallidum particle agglutination. A single serologic test is insufficient because false-positives occur with other illnesses.

If syphilis is diagnosed after 20 weeks' gestation, ultrasonography should be performed to evaluate for fetal syphilis. Although fetal infection can be cured by treating the mother, treatment failure is much higher in the presence of fetal hepatomegaly, ascites, hydrops, polyhydramnios, and placental thickening, which are signs of fetal syphilis detected on ultrasonography.

Although fetal infection can be cured by treating the mother, treatment failure is much higher in the presence of fetal hepatomegaly, ascites, hydrops, polyhydramnios, and placental thickening, which are signs of fetal syphilis detected on ultrasonography.

Treatment has been with benzathine penicillin G. A Cochrane review concluded that although penicillin is effective for the treatment of syphilis in pregnancy and the prevention of congenital syphilis, the optimal treatment regimen is uncertain.20 The CDC recommends benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units intramuscularly, with desensitization in patients who are allergic to penicillin.1

Vaginal Infections

Trichomonas vaginalis, a sexually transmitted vaginal infection, has been associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight.21Trichomonas infection can have unpleasant symptoms such as itching, heavy discharge, vaginal irritation, and odor. It also causes a chronic inflammatory condition and may facilitate HIV transmission. 22 Women with symptoms of trichomoniasis should be evaluated with a saline wet mount or culture for the presence of trichomonads. Screening for Trichomonas in asymptomatic women is not recommended.1

22 Women with symptoms of trichomoniasis should be evaluated with a saline wet mount or culture for the presence of trichomonads. Screening for Trichomonas in asymptomatic women is not recommended.1

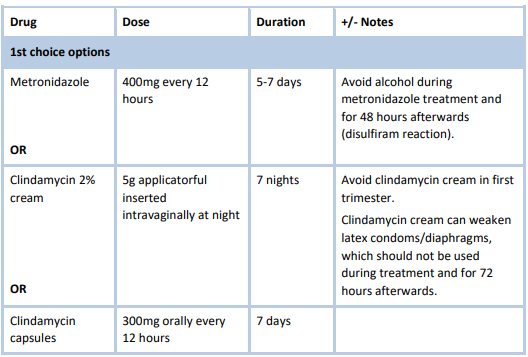

Metronidazole (Flagyl) 2 g orally in a single dose or 500 mg twice per day for seven days is the treatment for trichomoniasis in pregnancy,1 although many physicians wait until after the first trimester to initiate it. It is pregnancy category B, but the manufacturer recommends caution in using it in the first trimester. One meta-analysis found no relationship between exposure to metronidazole in the first trimester and birth defects; however, it included only five studies.23 Tinidazole (Tindamax) is the only other drug available in the United States that is effective against Trichomonas and it is not recommended in pregnancy (category C). The outcome of treating trichomoniasis during pregnancy is uncertain.24 Treatment has not been shown to reduce the incidence of preterm birth. 21

21

Bacterial vaginosis is not an STI, but it is more common in sexually active women. Although many studies have shown an association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes, and low birth weight, it is not known whether the bacterial overgrowth causes these complications, or if it is a marker for intrauterine colonization. Screening for and treating bacterial vaginosis in asymptomatic pregnant women does not appear to reduce the risk of pregnancy complications.21,25 A summary of treatments for the infections discussed is provided in Table 2.1,4–6,8,14,16,19,20,25

| Condition | Treatment options | |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial vaginosis* | Metronidazole (Flagyl) 500 mg orally two times per day for seven days1 | |

| Chlamydia | Azithromycin (Zithromax) 1 g orally in a single dose1,4,5 | |

| Amoxicillin 500 mg orally three times per day for seven days1 | ||

| Gonorrhea | Ceftriaxone (Rocephin) 125 mg intramuscularly in a single dose1,6,8 | |

| Cefixime (Suprax) 400 mg orally in a single dose1,8 | ||

| HIV | Highly active antiretroviral therapy (individualized)1,14,16 | |

| HSV type 2 | ||

| First episode | Acyclovir (Zovirax) 400 mg orally three times per day or 200 mg orally five times per day for seven to 10 days1 | |

| Valacyclovir (Valtrex) 1 g orally two times per day for seven to 10 days1 | ||

| Recurrent | Acyclovir 400 mg orally three times per day for five days1 | |

| Valacyclovir 1 g orally once per day for five days1 | ||

| Suppressive therapy | Acyclovir 400 mg orally two times per day1 | |

| Valacyclovir 500 mg orally once per day1 | ||

| Syphilis | Benzathine penicillin G 2. 4 million units intramuscularly1,19,20 4 million units intramuscularly1,19,20 | |

| Primary: single dose | ||

| Positive serology, no symptoms: three doses one week apart | ||

| Desensitization recommended in patients who are allergic to penicillin1 | ||

| Trichomoniasis | Metronidazole 2 g orally in a single dose1,25 | |

Chlamydia During Pregnancy - American Pregnancy Association

Navigating pregnancy is difficult enough, but the addition of having a sexually transmitted infection (STI) like chlamydia during pregnancy can add more stress. If you think you may have an STI during your pregnancy, it is crucial that you talk to your healthcare provider and get tested right away. If you think you may have (or have already been diagnosed with chlamydia during your pregnancy), you probably have a lot of questions about how the infection could affect your baby and your prenatal care. Answers to all these questions are presented below!

Answers to all these questions are presented below!

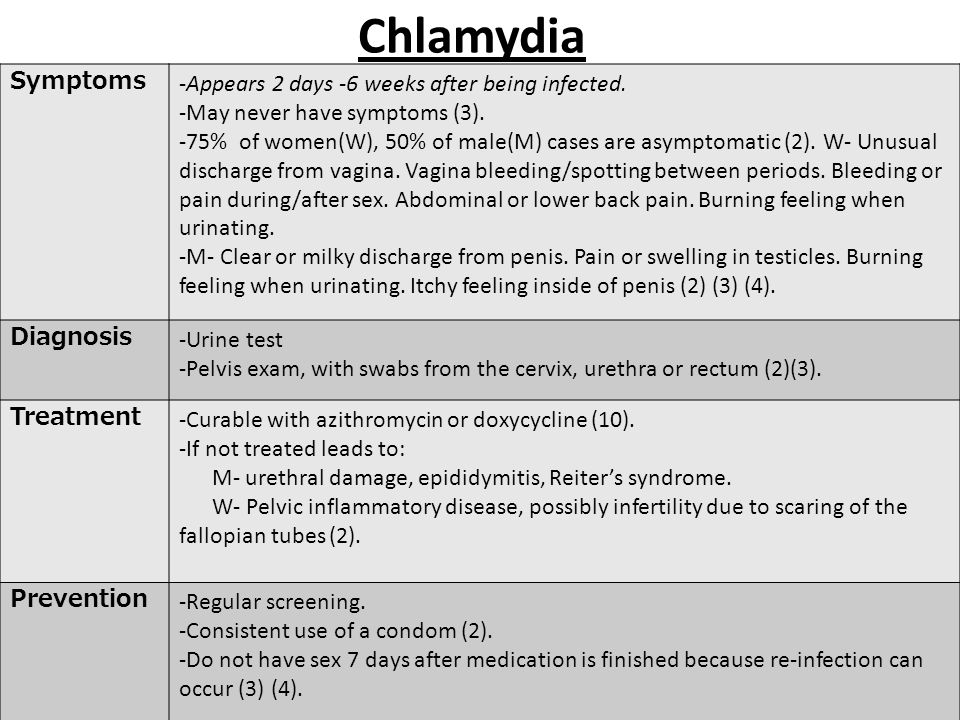

Chlamydia is a bacterial infection and is the most commonly reported bacterial STI. It is often symptomless, making it difficult to diagnose without running tests. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) suggests that all pregnant women be screened at their first prenatal visit, and additionally if any symptoms appear or if risk factors are present.

The CDC estimates that there are 2.86 million infections each year in the USA, with some individuals accounting for multiple cases.

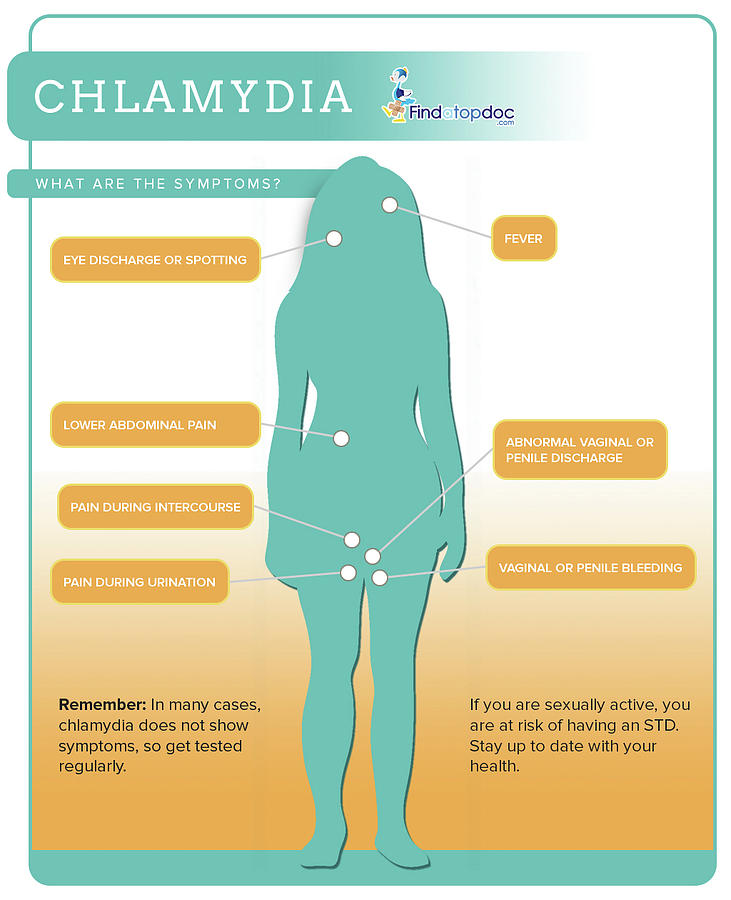

What are the symptoms of chlamydia during pregnancy?

In most cases, there are no symptoms. Some women may experience vaginal discharge and/or pelvic or abdominal pain.

Males usually have pain while urinating and may have a discharge from the penis. If you are pregnant and you notice your partner is experiencing these symptoms, you should both be screened for STIs like chlamydia.

Am I at risk for contracting chlamydia during my pregnancy?

Anyone who is sexually active (outside of a monogamous relationship where you both have not had previous sexual partners) is at risk for contracting chlamydia via vaginal, anal, or oral sex.

You have the highest risk of contracting chlamydia during your pregnancy if you are sexually active and:

- Have multiple sexual partners,

- Have sex without a condom,

- Have had a previous or current STI, and/or

- Have a partner with an STI.

How will chlamydia affect my pregnancy?

The largest risk to the fetus is if the infection goes untreated. The CDC suggests that all pregnant women be tested at the first prenatal appointment.

If you are at a higher risk for contracting STIs during your pregnancy (i.e. have a new sexual partner or multiple partners), an additional test should be done in the third trimester so that treatment can be started before delivery.

If you have an active or untreated chlamydia infection during delivery, the baby has a chance of contracting the infection that will affect the baby in one of two ways: chlamydial conjunctivitis (18-44% of cases) or chlamydial pneumonia (3-16%).

The CDC also states that an active chlamydia infection during pregnancy increases the risk of preterm delivery.

Can my baby get chlamydia from me?

Yes, chlamydia may be spread from mother to child during birth (perinatal transmission).

The best way to prevent passing chlamydia to your baby during birth is to clear the infection before you are due. This is why first and third trimester screenings are so important, as well as reporting any new symptoms to your doctor.

How is chlamydia diagnosed?

Chlamydia may be diagnosed by your healthcare provider using a lab test to assess the secretions from the infected area which may include the cervix, urethra, anus, or throat. The lab may also use a urine sample for testing.

How is chlamydia treated during pregnancy?

Chlamydia may be treated and cured with antibiotics administered orally. This may be either a single dose or a 7-day course. The antibiotics used are typically safe during pregnancy.

If you continue seeing symptoms after a few days into the antibiotic treatment, you should return to your doctor for another evaluation. The CDC suggests that pregnant women who are treated for chlamydia infection should be retested at 3 weeks and 3 months post-treatment since reinfection is somewhat common.

The CDC suggests that pregnant women who are treated for chlamydia infection should be retested at 3 weeks and 3 months post-treatment since reinfection is somewhat common.

How can I prevent getting chlamydia during pregnancy?

There are only two 100% effective ways to prevent chlamydia. The first is to refrain from sexual contact of any kind. The second is to be in a long-term monogamous relationship such as marriage in which both of you test negative for STIs.

According to the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), the consistent and correct use of condoms can decrease the risk of contracting chlamydia during vaginal, oral, or anal intercourse by only 60%.

Compiled using information from the following sources:

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia-detailed.htm

2. Mayo Clinic

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chlamydia-trachomatis/symptoms-causes/dxc-20315310

3. Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS)

Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS)

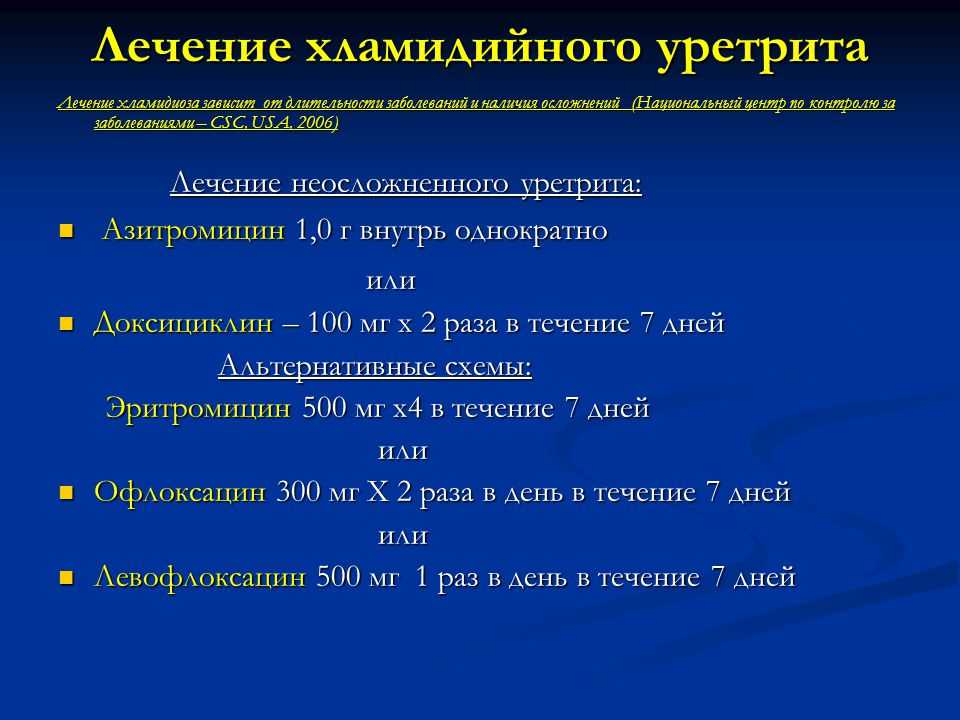

New in recommendations for the treatment of chlamydial infection during pregnancy | #10/06

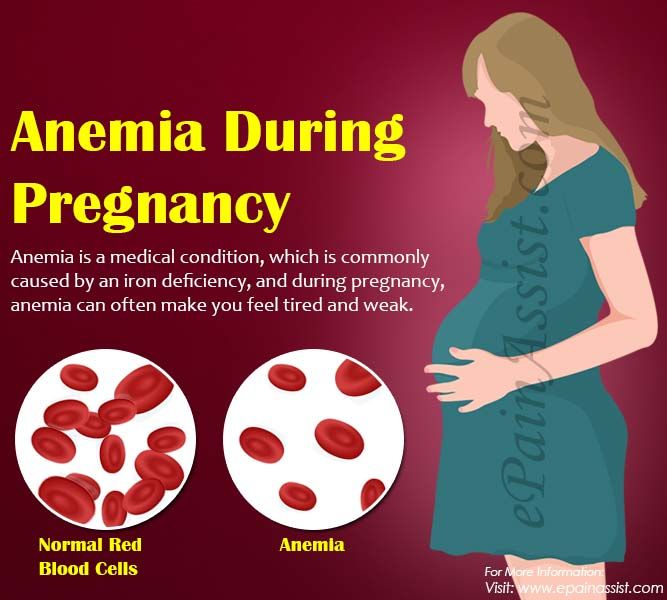

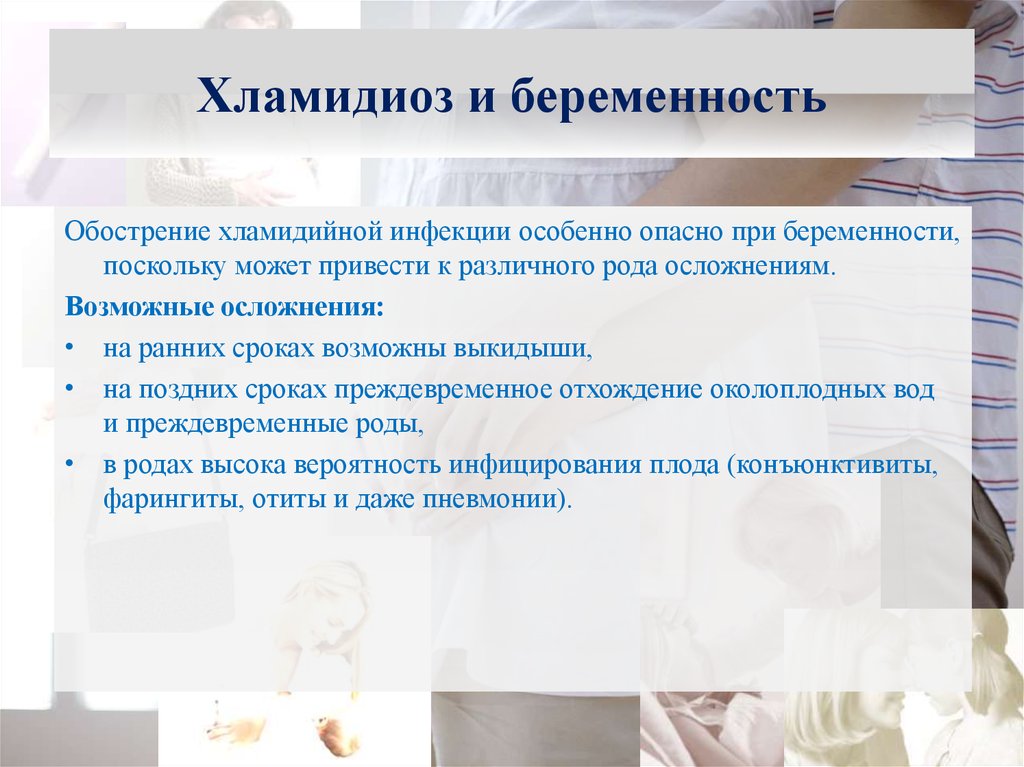

Chlamydial infection can significantly complicate pregnancy. It may be associated with the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as postpartum endometritis, preterm birth, low birth weight babies (W. A. Andrews et al., 2000).

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the prevalence of chlamydial infection in pregnant women is between 2 and 24%. 25–50% of children born to infected women develop chlamydial eye infection, 10–20% develop chlamydial pneumonia (J. Schachter, 1995). The risk of transmission to a newborn is about 70%.

The need for therapy of urogenital chlamydia in pregnant women, if for various reasons it was not possible to carry it out before pregnancy, is beyond doubt among specialists. The only condition that should be strictly observed when choosing adequate therapy for pregnant women is strict adherence to recognized, i. e., relevant principles of evidence-based medicine, recommendations. In fact, any appointment in modern practice must comply with such principles, but when it comes to the treatment of pregnant women, these requirements must be strictly observed - in order to avoid serious consequences.

e., relevant principles of evidence-based medicine, recommendations. In fact, any appointment in modern practice must comply with such principles, but when it comes to the treatment of pregnant women, these requirements must be strictly observed - in order to avoid serious consequences.

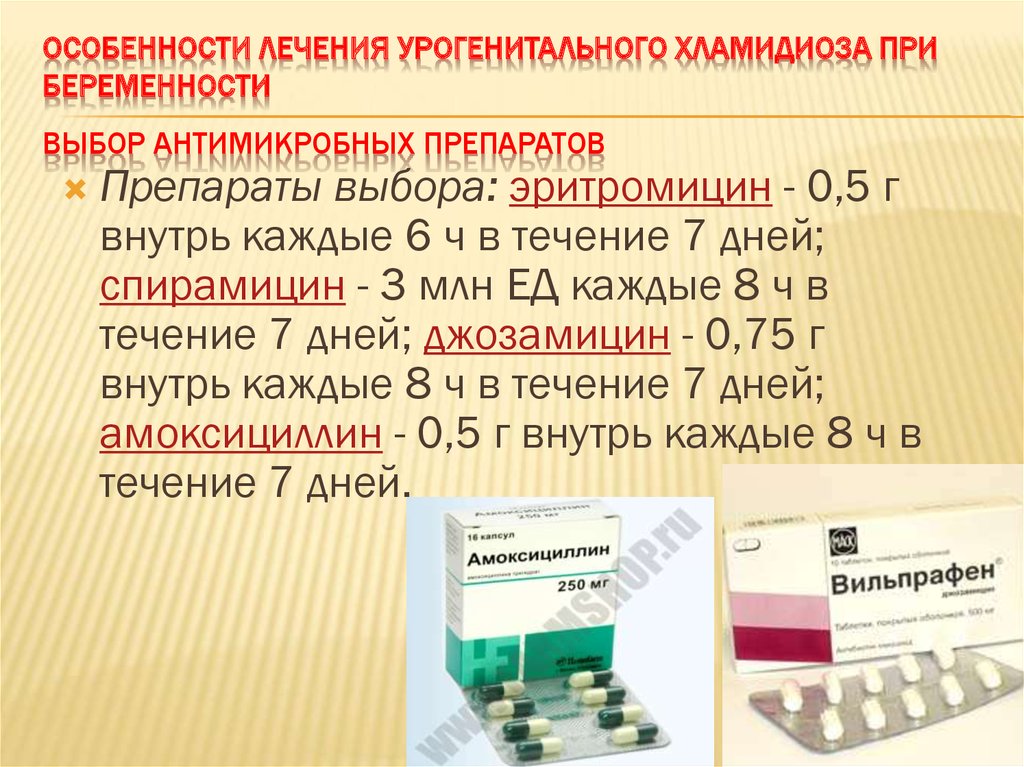

When covering the issues of treating chlamydial infection in pregnant women, we focused on modern approaches to solving this problem, set out in the latest editions of three guidelines - Russian ("Rational pharmacotherapy of skin diseases and sexually transmitted infections", edited by A. A. Kubanova, 2005 .), European (European STI Guidelines, 2001) and American (CDC Guidelines for the Treatment of STIs, 2006).

It is well known that the main antibiotics recommended by all world guidelines for the treatment of chlamydial infection are tetracyclines and macrolides. Ofloxacin is the only fluoroquinolone. It is also known that tetracycline drugs and fluoroquinolones are contraindicated during pregnancy due to the pathological effect on the formation of teeth and bone tissue in the fetus. Thus, of the antibiotics recommended for the treatment of pregnant women with antichlamydial activity, only macrolides remain.

Thus, of the antibiotics recommended for the treatment of pregnant women with antichlamydial activity, only macrolides remain.

The first of the macrolides appeared erythromycin. A huge number of observations, accumulated over almost 60 years of the existence of erythromycin, showed its safety for the fetus. This antibiotic is one of the few approved for use in pregnant women and newborns. In this regard, for the treatment of chlamydial infection in pregnant women, erythromycin has long appeared as the drug of first choice in all recommendations.

When taking any macrolides, side effects from the gastrointestinal tract (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) and liver (increased activity of transaminases, cholestasis, jaundice), as well as allergic reactions, can be observed.

The issue of tolerability becomes one of the main ones when choosing a drug for the treatment of chlamydial infection in pregnant women.

Side effects, mainly from the gastrointestinal tract, when taking erythromycin develop in 15–100% of patients, 12–33% of patients stop therapy because of this (J. Kacmar, 2001). In pregnant women, side effects after taking erythromycin are observed especially often. This forces us to look for new methods of treating pregnant women with drugs that are not inferior in safety to erythromycin. The problem with prescribing new, even relatively new, antibiotics to pregnant women is explained by the fact that no one conducts special clinical trials on pregnant women for ethical reasons. Even if drugs have not been shown to be teratogenic or mutagenic in animal experiments, it takes many years to accumulate data on the safety of drugs in pregnant and lactating women. Progress in this area is very slow, which is nonetheless justified by the complexity of the problem and the enormous responsibility involved in amending existing recommendations.

Kacmar, 2001). In pregnant women, side effects after taking erythromycin are observed especially often. This forces us to look for new methods of treating pregnant women with drugs that are not inferior in safety to erythromycin. The problem with prescribing new, even relatively new, antibiotics to pregnant women is explained by the fact that no one conducts special clinical trials on pregnant women for ethical reasons. Even if drugs have not been shown to be teratogenic or mutagenic in animal experiments, it takes many years to accumulate data on the safety of drugs in pregnant and lactating women. Progress in this area is very slow, which is nonetheless justified by the complexity of the problem and the enormous responsibility involved in amending existing recommendations.

In the last 15 years, azithromycin has been recognized as the most active antichlamydial drug and the main drug for the treatment of various forms of urogenital chlamydial infection. It is this antibiotic that all the mentioned guidelines refer to as the drugs of choice in the treatment of chlamydia. This is facilitated by the unique pharmacokinetic characteristics of azithromycin: a long half-life, a high level of absorption and stability in an acidic environment, the ability of this antibiotic to be transported by leukocytes to the site of inflammation, a high and prolonged concentration in tissues, and the possibility of penetration into the cell. Due to the fact that a high therapeutic concentration of azithromycin in tissues is achieved after a single dose of a standard dose of an antibiotic and persists at the sites of inflammation for at least 7 days, with the advent of azithromycin, for the first time, it became possible to effectively treat patients with chlamydial infection by a single dose of an antibiotic inside. The cure of chlamydial infection after a single dose of azithromycin is confirmed by the highest compliance in comparison with all other antibiotics, which should be prescribed for at least 7 days. It has been shown that violation of multi-day treatment regimens is noted by up to 25% of patients, and with the development of side effects, this figure increases significantly.

This is facilitated by the unique pharmacokinetic characteristics of azithromycin: a long half-life, a high level of absorption and stability in an acidic environment, the ability of this antibiotic to be transported by leukocytes to the site of inflammation, a high and prolonged concentration in tissues, and the possibility of penetration into the cell. Due to the fact that a high therapeutic concentration of azithromycin in tissues is achieved after a single dose of a standard dose of an antibiotic and persists at the sites of inflammation for at least 7 days, with the advent of azithromycin, for the first time, it became possible to effectively treat patients with chlamydial infection by a single dose of an antibiotic inside. The cure of chlamydial infection after a single dose of azithromycin is confirmed by the highest compliance in comparison with all other antibiotics, which should be prescribed for at least 7 days. It has been shown that violation of multi-day treatment regimens is noted by up to 25% of patients, and with the development of side effects, this figure increases significantly. Thus, a clear advantage of azithromycin is the possibility of its administration once, which is especially important in pregnant women.

Thus, a clear advantage of azithromycin is the possibility of its administration once, which is especially important in pregnant women.

The original and most famous of the azithromycin preparations is sumamed, which has been used in the Russian Federation since the early 90s of the last century. It is in relation to this drug that the greatest experience has been accumulated in the treatment of a wide variety of forms of chlamydial infection.

Despite the general requirements regarding the use of only international names of drugs in publications, when describing the effectiveness of the use of a drug, its tolerability, it seems important to indicate which particular commercial drug was used in the study, because the quality of the same drugs produced by different manufacturers may be different. . In order to show the effectiveness and tolerability of their particular product, many pharmaceutical companies that produce generics conduct comparative tests of their products with the original drug, which, as noted above, is sumamed. With the use of sumamed, the bulk of the pharmacological and clinical studies of azithromycin all over the world were carried out, since it was from the substance supplied by the same company that produced sumamed, common in Eastern Europe, for many years in the USA that Zithromax was produced, supplied to the countries of Western Europe, America and Japan.

With the use of sumamed, the bulk of the pharmacological and clinical studies of azithromycin all over the world were carried out, since it was from the substance supplied by the same company that produced sumamed, common in Eastern Europe, for many years in the USA that Zithromax was produced, supplied to the countries of Western Europe, America and Japan.

According to Russian guidelines for chlamydial infection in pregnant women, the drugs of choice are:

- azithromycin - 1.0 g once;

- erythromycin - 500 mg 4 times a day for 7 days;

- josamycin - 750 mg 2 times a day for 7 days;

- amoxicillin - 500 mg 3 times a day for 7 days.

Thus, of the relatively new macrolides in domestic recommendations, azithromycin and josamycin are among the drugs of choice. Although Russia does not yet have national standards for the treatment of STIs, our country has become one of the first countries in the world where azithromycin appeared in official recommendations as the main drug for the treatment of chlamydial infection during pregnancy.

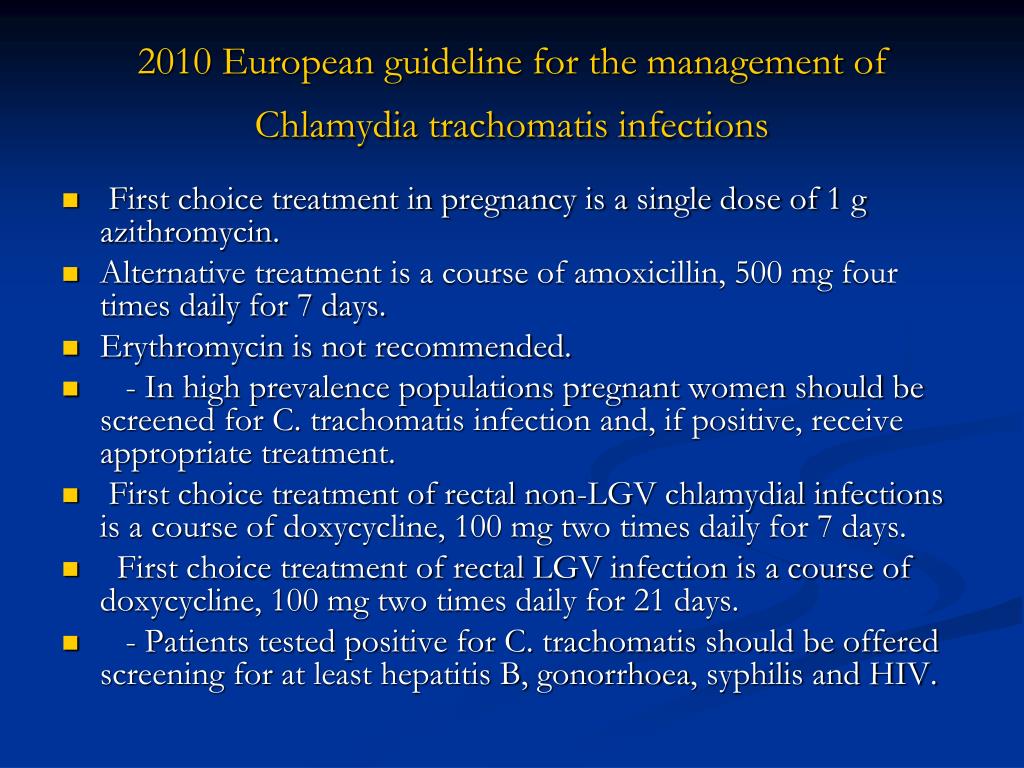

In the European guidelines, among the essential drugs are:

- erythromycin base 500 mg orally 4 times a day for 7 days;

- amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times a day for 7 days;

- josamycin 750 mg orally twice a day for 7–14 days.

The following schemes are given as alternatives:

- erythromycin base 250 mg orally 4 times a day for 14 days;

- erythromycin ethyl succinate 800 mg orally 4 times a day for 7 days, or 400 mg for 14 days;

- azithromycin 1.0 g once orally.

According to European colleagues, despite the efficacy and safety of azithromycin, observations regarding the safety of its use are not yet long enough to recommend its routine use during pregnancy. True, it should be recalled that we are talking about the 2001 Recommendations, which have not been corrected since then.

Until recently, and in the US guidelines, azithromycin was not among the main drugs recommended for the treatment of chlamydial infection in pregnant women. Back in 2002, for the treatment of pregnant women, according to the Guidelines for the Treatment of STIs - CDC, it was recommended to use only erythromycin or amoxicillin. But after the Russian specialists and the Americans changed their recommendations: the new version of the Guidelines from 2006 already recommends a single dose of azithromycin as the main treatment regimen for chlamydial infection in pregnant women. Erythromycin was first transferred to the category of alternative drugs. Amoxicillin remained as the drug of choice along with azithromycin.

Back in 2002, for the treatment of pregnant women, according to the Guidelines for the Treatment of STIs - CDC, it was recommended to use only erythromycin or amoxicillin. But after the Russian specialists and the Americans changed their recommendations: the new version of the Guidelines from 2006 already recommends a single dose of azithromycin as the main treatment regimen for chlamydial infection in pregnant women. Erythromycin was first transferred to the category of alternative drugs. Amoxicillin remained as the drug of choice along with azithromycin.

It can be expected that soon Europe will join the Russian and American colleagues.

I would like to comment on some of the recommendations cited above.

So, why does azithromycin come out on top in the treatment of chlamydial infection in pregnant women?

All recommendations regarding the treatment of pregnant women are very conservative and do not change for decades until data on the safety of a new drug accumulate. Preclinical animal studies have not shown any teratogenic effect of azithromycin. This alone is not enough to allow its use in pregnant women. The appearance of azithromycin as a treatment for chlamydial infection in pregnant women in some recognized guidelines indicates that, by now, a sufficient amount of data has already accumulated around the world on the results of the use of azithromycin, both in the course of planned studies and as a result of accidental use by pregnant women who did not know that they are in this state. No reliable reports of a negative effect on the fetus of azithromycin have yet been received. All these data accumulated gradually in different countries, with the longest experience among researchers from Croatia, where azithromycin was first obtained.

Preclinical animal studies have not shown any teratogenic effect of azithromycin. This alone is not enough to allow its use in pregnant women. The appearance of azithromycin as a treatment for chlamydial infection in pregnant women in some recognized guidelines indicates that, by now, a sufficient amount of data has already accumulated around the world on the results of the use of azithromycin, both in the course of planned studies and as a result of accidental use by pregnant women who did not know that they are in this state. No reliable reports of a negative effect on the fetus of azithromycin have yet been received. All these data accumulated gradually in different countries, with the longest experience among researchers from Croatia, where azithromycin was first obtained.

According to V. Simunic and co-authors, the effectiveness of 1 g of azithromycin in the treatment of chlamydial infection in pregnant women was 92.1%, and a seven-day course of erythromycin was 87.5%. At the same time, compliance and tolerability of azithromycin therapy were much better, and pregnancy outcomes in the groups did not differ significantly. In women with a burdened obstetric and gynecological history and the presence of chlamydial infection, after the use of azithromycin, preterm birth occurred in 10.5% of cases, in 7.9% - early miscarriages, 2.6% - late miscarriages. In the group of the same pregnant women who received erythromycin, preterm birth, early miscarriages and late miscarriages were observed in 12.5, 8.4 and 4.1% of cases, respectively.

At the same time, compliance and tolerability of azithromycin therapy were much better, and pregnancy outcomes in the groups did not differ significantly. In women with a burdened obstetric and gynecological history and the presence of chlamydial infection, after the use of azithromycin, preterm birth occurred in 10.5% of cases, in 7.9% - early miscarriages, 2.6% - late miscarriages. In the group of the same pregnant women who received erythromycin, preterm birth, early miscarriages and late miscarriages were observed in 12.5, 8.4 and 4.1% of cases, respectively.

In another study (C. D. Adair et al., 1998), a comparable therapeutic effect of azithromycin and erythromycin was also shown - 88.1 and 93.0%. But the tolerability of the course of treatment with the use of azithromycin was much higher than with the use of erythromycin - gastrointestinal disorders were observed in 11.9% of patients taking azithromycin (of which 1 patient (2.4%) had to stop treatment due to the development of vomiting 4 hours after taking the drug), and in 58. 1% of patients taking erythromycin (treatment was forced to stop 18, 6% of patients). The lower incidence of side effects when taking azithromycin is partly due to a single dose of this drug. No pathological effects of the therapy on newborns were recorded.

1% of patients taking erythromycin (treatment was forced to stop 18, 6% of patients). The lower incidence of side effects when taking azithromycin is partly due to a single dose of this drug. No pathological effects of the therapy on newborns were recorded.

In a study by M. R. Bush et al. (1994) side effects when taking erythromycin were noted in all patients (15 patients), when prescribing azithromycin - none of the 15. Five of the 15 patients taking erythromycin could not complete the treatment.

According to the Cochrane Review, the microbiological cure rate in pregnant women as a result of the use of all antibiotics listed in the guidelines ranges from 90%. The same review, despite the small amount of data, concludes that pregnant women tolerate azithromycin better and therefore treatment with azithromycin may be more effective. Studies have not led to the conclusion that microbiological cure during pregnancy guarantees against subsequent neonatal illness or postpartum manifestations of chlamydial infection in women.

Amoxicillin belongs to a group of penicillins generally not recommended for use in chlamydia, but the Cochrane Review has reported success in pregnant women with chlamydial infection, although this is surprising. It is less likely than erythromycin or azithromycin to cause side effects that force you to stop treatment. Thus, in a study by J. Kacmar et al. (2001), side effects were reported in 40% of patients taking azithromycin and 17% of those taking amoxicillin. However, about 16% of patients taking amoxicillin violated the treatment regimen by skipping the medication. The effectiveness of treatment was 80% when taking amoxicillin and 94.7% when taking azithromycin (differences are not statistically significant). The lack of long-term studies of the effect of amoxicillin on the risk of developing neonatal infections does not allow us to confidently recommend this drug for routine clinical practice. Long-term follow-up of a group of newborns and their mothers treated with amoxicillin for chlamydial infection during pregnancy would allow clinicians to more widely apply this treatment regimen. Amoxicillin, without a doubt, can be used as an alternative drug for the treatment of pregnant women with macrolide intolerance.

Amoxicillin, without a doubt, can be used as an alternative drug for the treatment of pregnant women with macrolide intolerance.

All patients treated with erythromycin, which is still more commonly used in pregnant women, are advised to conduct a repeat laboratory study 3 weeks after the end of therapy, since side effects may force the patient to violate the scheme of its use.

In conclusion, we once again wanted to return to the problem of changing the traditional recommendations for the treatment of chlamydial infection in pregnant women. This is a very responsible decision that requires many years of observation. In recent years, the only major change in this area has been the appearance of azithromycin among the drugs of choice in Russian and major world recommendations. Of course, this was facilitated by many features of this antibiotic, such as a long half-life, a high level of absorption and stability in an acidic environment, the ability to be transported by leukocytes to the site of inflammation, a high and prolonged concentration in tissues, the ability to penetrate into the cell, and good tolerance. But azithromycin has become the main drug for the treatment of urogenital chlamydial infection in pregnant women, primarily due to its low toxicity and safety for the fetus.

But azithromycin has become the main drug for the treatment of urogenital chlamydial infection in pregnant women, primarily due to its low toxicity and safety for the fetus.

A. M. Soloviev, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor

M. A. Gomberg , Doctor of Medical Sciences

MGMSU, Moscow

Reproductive Health Education CenterReproductive Health Education Center

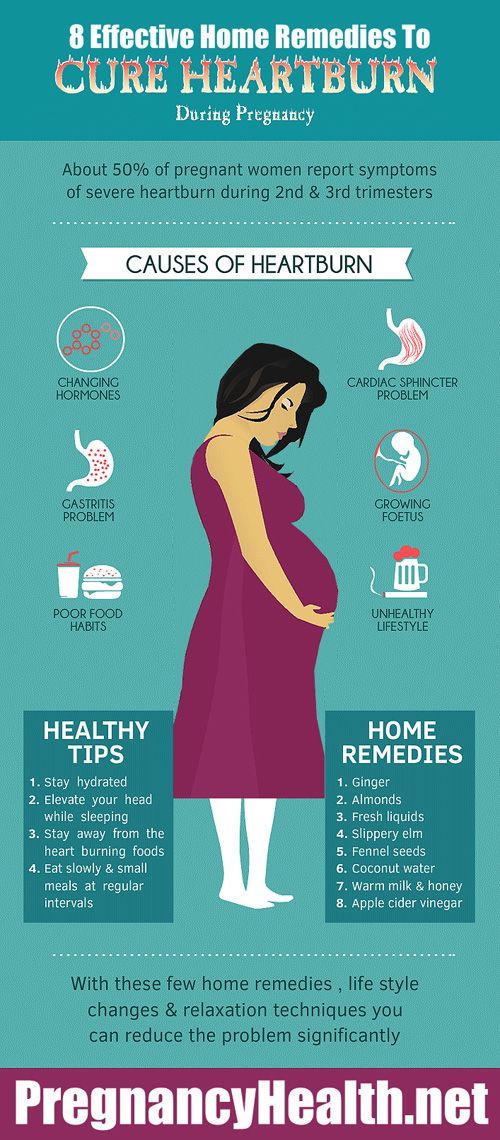

Pregnancy is a happy period in every woman's life. Everyone knows how important it is to take care of your health during this period, because during pregnancy any infection is dangerous not only for the mother, but also for the health of the unborn baby. In pregnant women, immunity is always slightly reduced: a change in the immune status is a physiological response to pregnancy. Reduced immunity is necessary for the expectant mother so that her body does not reject the fetus, perceiving it as a foreign object. That is why the body of the expectant mother during pregnancy becomes extremely vulnerable to infections that lie in wait for a woman at every turn. Unfortunately, no one is immune from various diseases during this period. Venereal diseases are no exception. In particular, chlamydia is quite common during pregnancy.

That is why the body of the expectant mother during pregnancy becomes extremely vulnerable to infections that lie in wait for a woman at every turn. Unfortunately, no one is immune from various diseases during this period. Venereal diseases are no exception. In particular, chlamydia is quite common during pregnancy.

The effect of chlamydia on pregnancy can be extremely detrimental, which is why it is very important to know what are the symptoms of the disease, what are the dangers of chlamydia for the unborn child, how to treat the infection so as not to harm the fetus.

The danger of chlamydia in pregnant women lies in the fact that very often it occurs in a latent form. After a rather long incubation period, mild signs of the disease may appear, which are easy to mistake for a common ailment, but they may be absent altogether if the woman does not suffer from serious diseases and immunodeficiency. If chlamydia is not recognized in time in the blood of a pregnant patient, they can cause premature miscarriage or intrauterine infection of the fetus, which often leads to serious malformations and disorders in the formation of the body of the unborn baby.

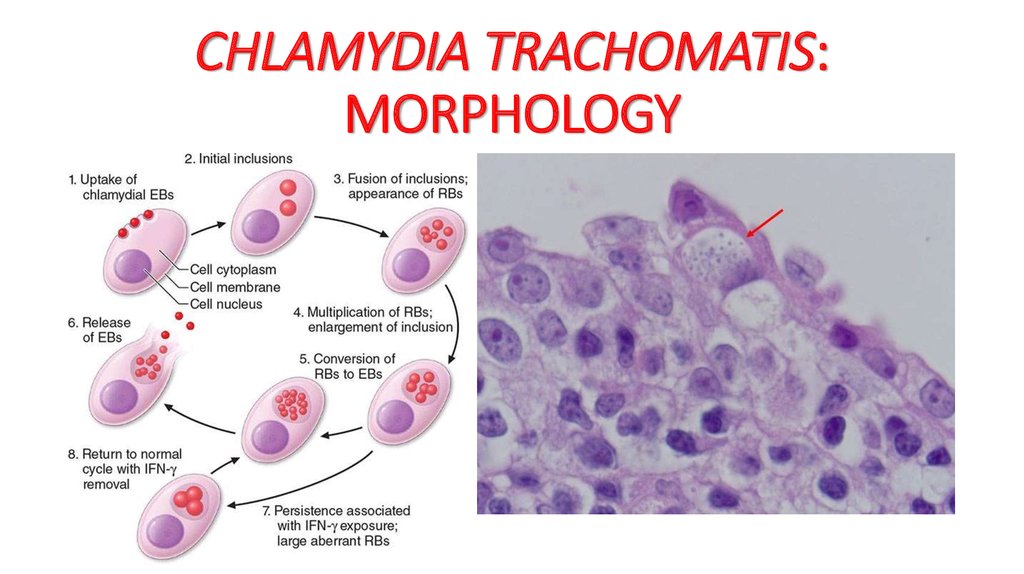

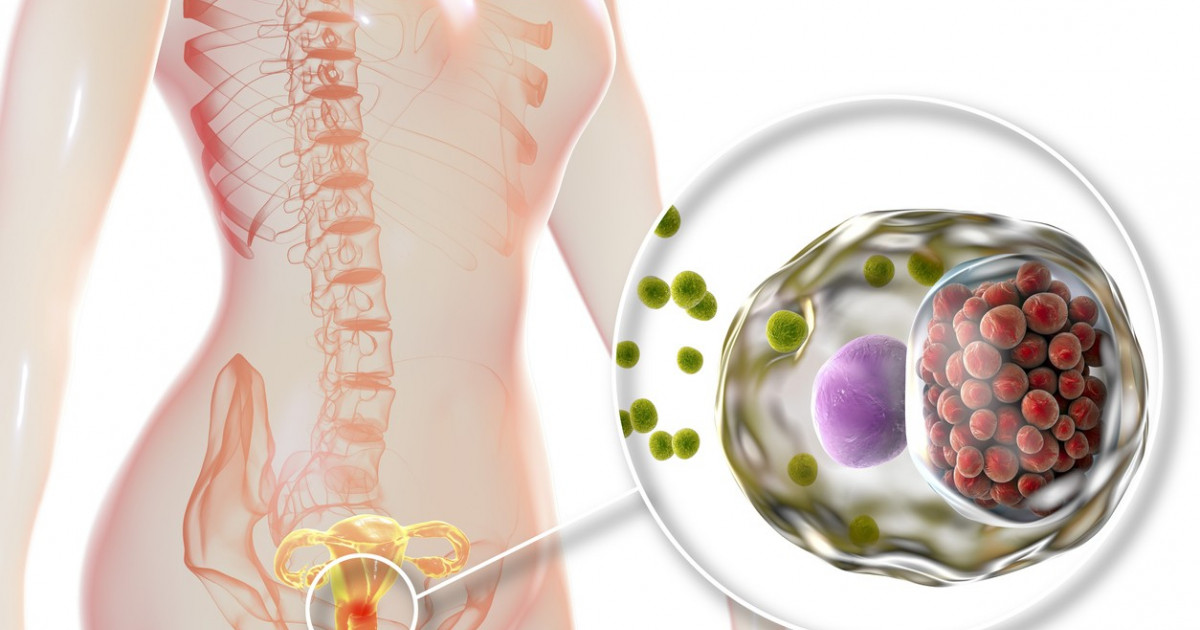

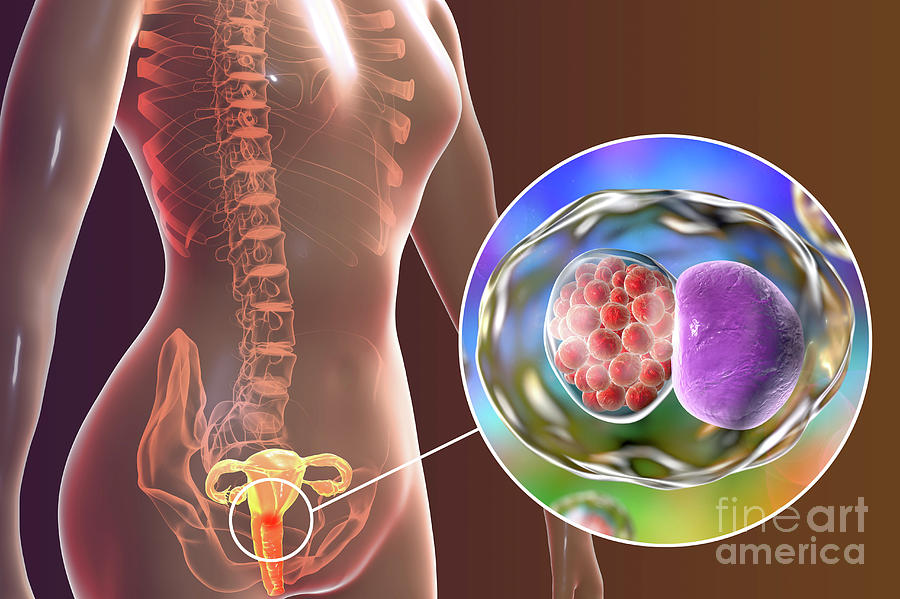

What is Chlamydia trachomatis?

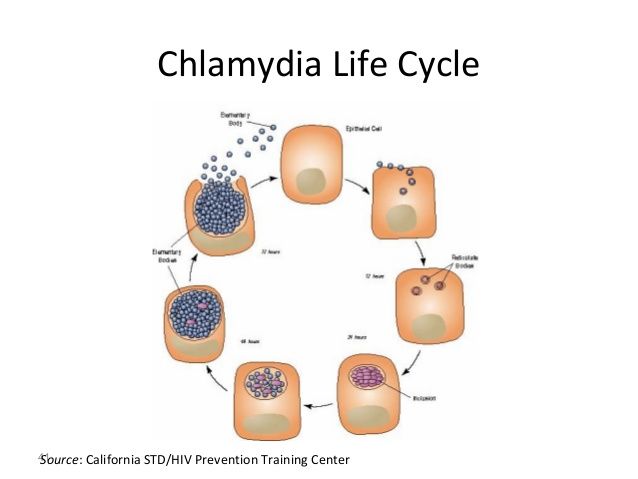

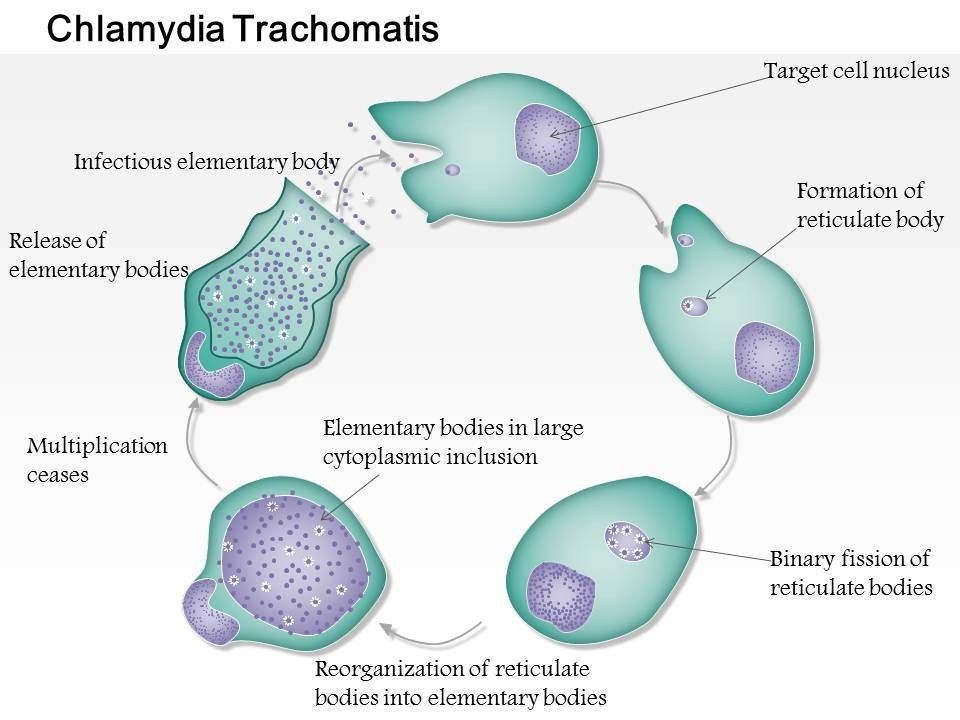

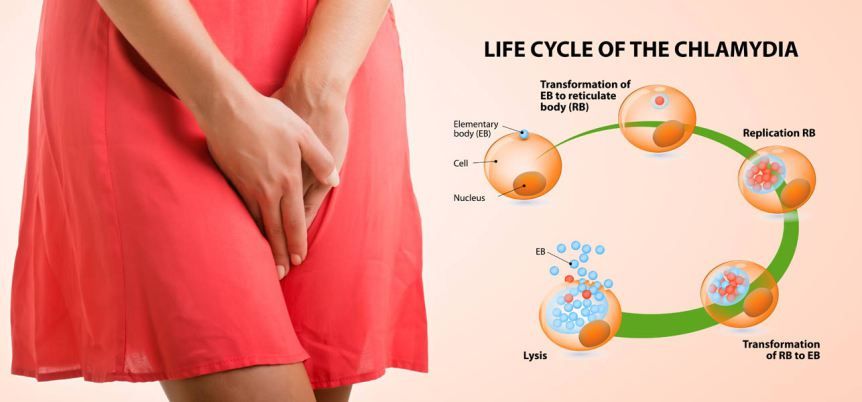

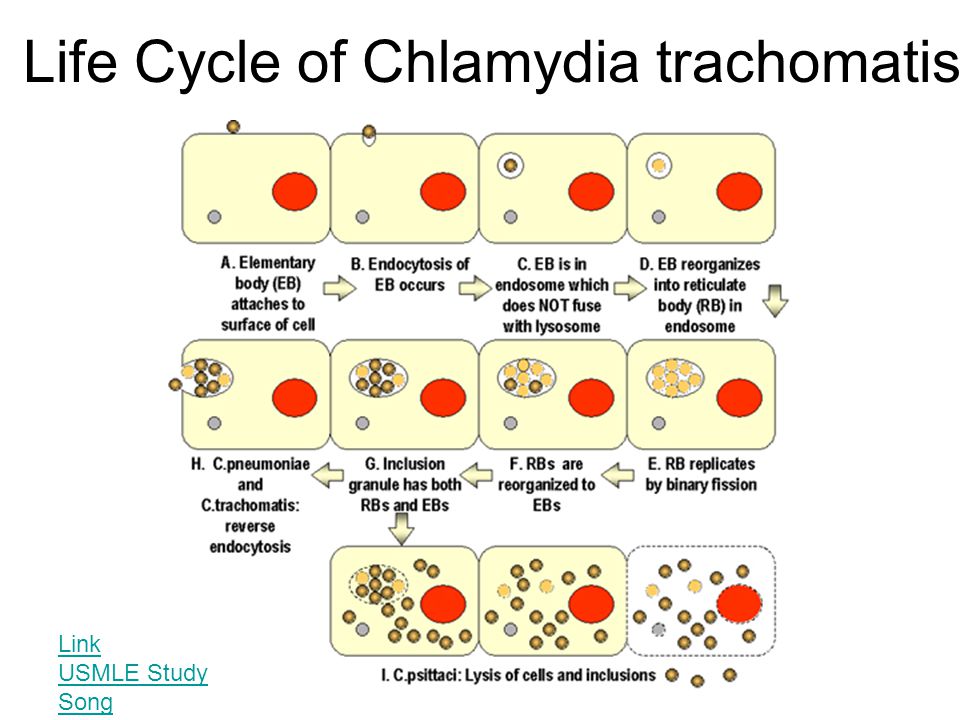

The nature of the pathogen easily explains why chlamydia is so difficult to recognize and treat. Chlamydia are intracellular parasites. They combine the features of bacteria and viruses at the same time. They are much larger than bacteria, but do not reach the usual size of viruses. Getting into the external environment, chlamydia quickly die, so the disease is not transmitted by contact-household method. Once in the human body, the pathogen begins to feed on energy from the cells, affecting the genitourinary system. Chlamydia during pregnancy affects not only the vulva, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries, but also the fetal membranes. This is especially dangerous for the health and life of the unborn child.

Causes of the disease

The source of the disease is an infected sexual partner. Chlamydia is transmitted exclusively through sexual intercourse, if barrier contraception was not used during sexual intercourse. A woman's sexual partner may be a carrier of chlamydia, but due to the latent course of the disease, he may not be aware of its existence. That is why it is so important during pregnancy to undergo a comprehensive examination for the presence of a variety of diseases, which includes PCR for chlamydia. Timely detected chlamydia is treated quite successfully (see a detailed article about the treatment of chlamydia during pregnancy). Pregnancy after treatment and during it proceeds in most cases favorably if the doctor recognizes the infection in time and takes all measures to eliminate it safely and effectively.

A woman's sexual partner may be a carrier of chlamydia, but due to the latent course of the disease, he may not be aware of its existence. That is why it is so important during pregnancy to undergo a comprehensive examination for the presence of a variety of diseases, which includes PCR for chlamydia. Timely detected chlamydia is treated quite successfully (see a detailed article about the treatment of chlamydia during pregnancy). Pregnancy after treatment and during it proceeds in most cases favorably if the doctor recognizes the infection in time and takes all measures to eliminate it safely and effectively.

The cause of intrauterine infection of the fetus is the penetration of chlamydia into the fluid surrounding the fetus. After infection of the fetal membrane, the infection of the fetus itself also occurs, since the child, while in the womb, regularly swallows a small amount of amniotic fluid.

Why are chlamydia dangerous during pregnancy?

In addition to its usual complications, chlamydia in pregnant women can lead to the following adverse effects:

- Complicated pregnancy, threatened miscarriage

- Early and late miscarriages

- Intolerable toxicosis

- Inflammatory processes in the endometrium, inflammation of the mucous membranes of the uterus and vagina

- Inflammation of the amniotic membrane, which adversely affects the development of the child, since the amniotic membrane is involved in the supply of nutrients to the fetus

- Increased risk of preterm birth

- Development of intrauterine diseases in a child (anemia, pneumonia, conjunctivitis).

Chlamydia affects the mucous membrane of the child's eyes, as well as the upper respiratory tract and lungs.

Chlamydia affects the mucous membrane of the child's eyes, as well as the upper respiratory tract and lungs. - It is very common for pregnant women with chlamydia to give birth to premature babies.

How is chlamydia diagnosed during pregnancy?

Symptoms of the disease are identical to normal chlamydia. Usually the signs are quite weak and resemble urethritis or cystitis. A woman experiences discomfort and burning during urination, scanty and cloudy discharge from the urethra is observed. The discharge may contain pus. Pain in the lower abdomen and pain when urinating often cause the initial stage of chlamydia to be mistaken for cystitis.

In some cases, chlamydia in pregnant women can occur without inflammation in the urinary tract. The infection immediately affects the inner lining of the uterus, as well as the mucous membrane of the cervix. There is swelling of the cervix, its epithelium begins to collapse, erosion of varying severity develops.

Due to hormonal changes, a pregnant woman may also develop chlamydial colpitis (inflammation of the vagina), which is not typical for ordinary patients.

How to treat chlamydia in pregnant women?

As mentioned above, the most important stage from which treatment begins is the recognition of infection, for which serious examinations are prescribed. As for the treatment itself, not all antibacterial drugs are suitable for pregnant women. The task for the doctor in this case is complicated, since he will not only have to draw up an individual treatment regimen, but also choose antibiotics that will be as safe as possible and will not have contraindications. Most often, antibiotics of the tetracycline group are used to treat chlamydia, but they are highly undesirable for use during pregnancy. In this regard, doctors use antibiotics from the pharmacological group of macrolides to treat expectant mothers. Drugs are also prescribed to eliminate dysbacteriosis and restore the normal microflora of the vagina, as well as drugs that stimulate and strengthen the immune system.