Safety for pregnancy

Pregnancy Precautions: FAQs (for Parents)

Almost as soon as you see that little line on the home pregnancy test, the worry seems to set in. You start thinking about the two cups of coffee you had at work yesterday, the glass of wine you sipped at dinner last week, the tuna steak you devoured for lunch 2 weeks ago.

No doubt about it, pregnancy can be one of the most thrilling and most worrisome times in a woman's life. Of course, when you're pregnant, what you don't put into your body (or expose it to) can be almost as important as what you do.

But worrying out about every little thing you come into contact with can make for a long and stressful three trimesters. And fretting about things you did before you knew you were pregnant or before you found out they could be hazardous won't do you or your baby any good.

Questions abound regarding what women can and can't do during pregnancy. But the answers may not always come from the most reliable sources, so you might worry unnecessarily. Some warnings are worth listening to; others are popular but unproven rumors.

Knowing what could truly be harmful to your baby and what's not a real concern is the key to keeping your sanity during these 40 weeks.

The Top Pregnancy Hazards

You'll need to be particularly mindful of a handful of things during your pregnancy, some of which are more harmful than others. Your doctor (or other health care provider) will talk to you about what should be completely avoided, what should be greatly reduced, and what should be carefully considered during pregnancy.

Alcohol

Should I avoid it? Yes! Although it may seem harmless to have a glass of wine at dinner or a mug of beer out with friends, no one knows what's a "safe amount" of alcohol to drink during pregnancy. Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is caused by drinking a lot of alcohol during pregnancy. What that amount is versus a safe amount is really not known. Because of the uncertainty, it's always wise to be cautious and not drink any alcohol at all during pregnancy.

What are the risks to my baby? Alcohol is one of the most common causes of physical, behavioral, and intellectual disabilities. It can be even more harmful to a developing fetus than heroin, cocaine, or marijuana use.

Alcohol is easily passed along to the baby, whose body is less able to get rid of alcohol than the mother's. That means an unborn baby tends to develop a high concentration of alcohol, which stays in the baby's system for longer periods than it would in the mother's. And moderate alcohol intake, as well as periodic binge drinking, can possibly damage a baby's developing nervous system.

What can I do about it? If you had a drink or two before you even knew you were pregnant (as many women do), don't worry too much about it. But your best bet is to not drink any more alcohol for the rest of your pregnancy.

If you're an alcoholic or think you may have a drinking problem, talk to your doctor about it. He or she needs to know how much alcohol you've consumed and when during your pregnancy to get a better idea of how your unborn baby might be affected. Your doctor also can start you on a path to getting the help you need to stop drinking — for your sake and your baby's.

Your doctor also can start you on a path to getting the help you need to stop drinking — for your sake and your baby's.

P

Caffeine

Should I avoid and/or limit it? Yes. It's wise to cut down or stop caffeine intake. Studies show that caffeine consumption of more than 200–300 milligrams a day (about 2–3 cups of coffee, depending on the portion size, brewing method, and brand) might put a pregnancy at risk. Less than that amount is probably safe.

What are the risks to my baby? High caffeine consumption has been linked to an increased risk of miscarriage and, possibly, other pregnancy complications.

What can I do about it? If you're having a hard time cutting out coffee all at once, here's how you can start:

- Cut your consumption down to one or two cups a day.

- Gradually reduce the amount by combining decaffeinated coffee with regular coffee.

- Eventually cut out the regular coffee altogether.

And remember that caffeine is not only in coffee. Green and black tea, cola, and other soft drinks contain caffeine. Try switching to decaffeinated products (which may still have some caffeine, but in much smaller amounts) or caffeine-free alternatives.

If you're wondering about chocolate, which also has caffeine, the good news is that you can eat some in moderation. A cup of brewed coffee has 95–135 milligrams of caffeine, but the average chocolate bar has 5–30 milligrams. So, small amounts of chocolate are fine.

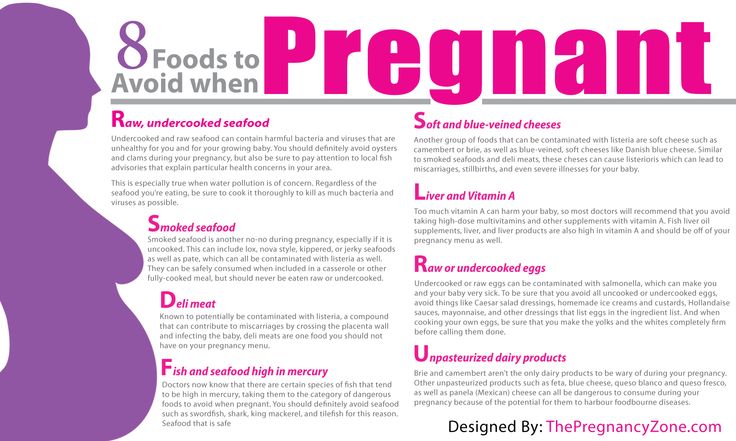

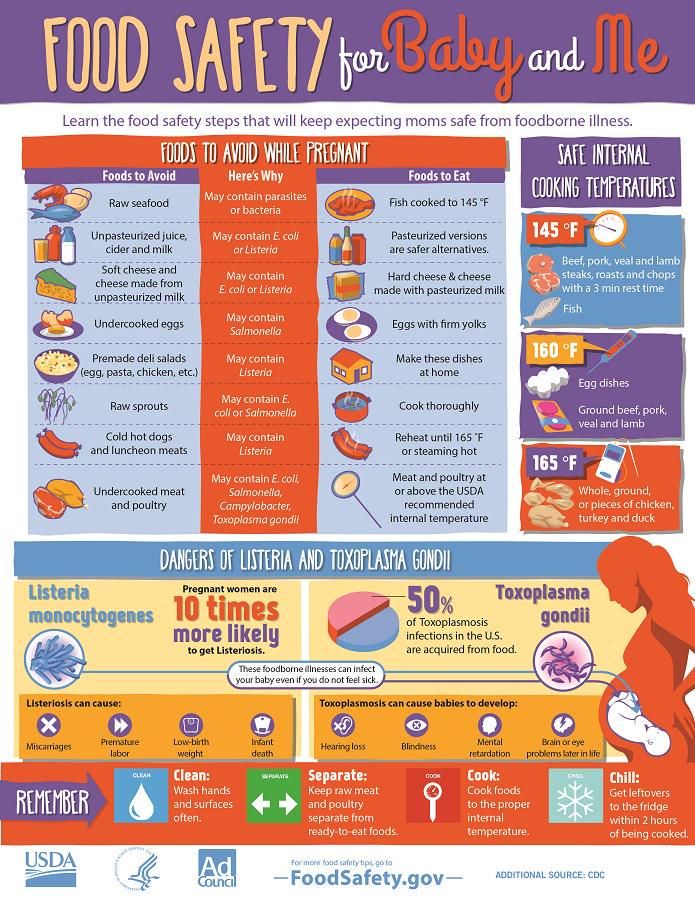

Certain Foods

Are there some I should avoid? Yes. Foods that are more likely to be contaminated with bacteria or heavy metals are ones to try to avoid or limit your exposure to. Those you should steer clear of during pregnancy include:

- soft, unpasteurized cheeses (often advertised as "fresh") such as feta, goat, Brie, Camembert, blue-veined cheeses, and Mexican queso fresco

- unpasteurized milk, juices, and apple cider

- raw eggs or foods containing raw eggs, including mousse, tiramisu, raw cookie dough, eggnog, homemade ice cream, and Caesar dressing

- raw or undercooked fish (sushi), shellfish, or meats

- paté and meat spreads

- processed meats like hot dogs and deli meats (these should be very well cooked before eating)

Also, although fish and shellfish can be an extremely healthy part of your pregnancy diet (they contain beneficial omega-3 fatty acids and are high in protein and low in saturated fat), you should avoid eating certain kinds due to high levels of mercury, which can damage the brain of a developing fetus.

Fish to avoid:

- shark

- swordfish

- king mackerel

- tilefish

- tuna steak (limited amounts of canned, preferably light, tuna is OK)

What are the risks to my baby? Although it's important to eat plenty of healthy foods during pregnancy, you also need to avoid foodborne illnesses, such as listeriosis, toxoplasmosis, and salmonella, which are caused by the bacteria that can be found in certain foods. These infections can be life-threatening to an unborn baby and may cause birth defects or miscarriage.

What can I do about it? Be sure to thoroughly wash all fruits and vegetables, which can carry bacteria or be coated with pesticide residue. And be mindful of what you're buying at the grocery store or when dining out.

When you choose seafood, eat a variety of fish and shellfish and limit the amount to about 12 ounces per week — that's about two meals. Common fish and shellfish that are low in mercury include: canned light tuna, catfish, pollock, salmon, and shrimp. But because albacore (or white) tuna has more mercury than canned light tuna, it's best to eat no more than 6 ounces (or one meal) of albacore tuna a week.

But because albacore (or white) tuna has more mercury than canned light tuna, it's best to eat no more than 6 ounces (or one meal) of albacore tuna a week.

You may have to skip a few foods during pregnancy that you normally enjoy. But just think how delicious they'll taste when you can have them again!

P

Changing the Litter Box

Should I avoid it? Yes. Pregnancy is the prime time to get out of cleaning kitty's litter box. But that doesn't mean that you have to keep away from Fluffy!

What are the risks to my baby? An infection called toxoplasmosis can be spread through soiled cat litter boxes and can cause serious problems in a fetus, including prematurity, poor growth, and severe eye and brain damage. A pregnant woman who becomes infected often has no symptoms but can still pass the infection on to her developing baby.

What can I do about it? Have someone else change the litter box, making sure to clean it thoroughly and regularly, then wash his or her hands well afterward.

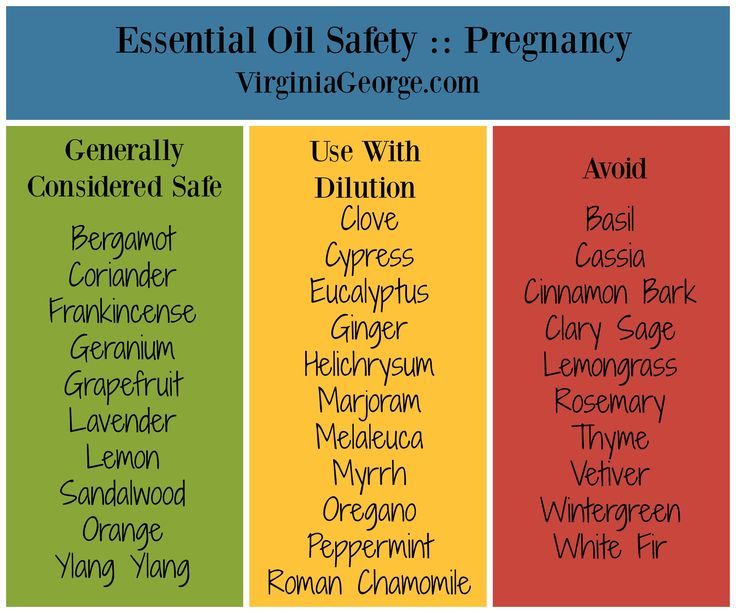

OTC and Prescription Medicines

Should I avoid them? Some, yes; others, no. There are many medicines you should not use during pregnancy. Be sure to talk to your doctor about which prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs you can and can't take, even if they seem like no big deal.

What are the risks to my baby? Even common OTC medicines that you can buy in stores without a prescription may be off-limits during pregnancy because of their potential effects on the baby. Certain prescription medicines may also harm the developing fetus. (The type of harm and extent of possible damage depends on the kind of medication.)

Also, although they may seem harmless, herbal remedies and supplements are not regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). That means that they don't have to follow any safety standards and thus could be harmful to your baby.

What can I do about it? To make sure you don't take anything that could put your baby at risk, talk to your doctor about:

- any medicines you're taking — prescription and OTC — and ask which are safe to take during pregnancy

- any concerns you have about natural remedies, supplements, and vitamins

Also, let all of your health care providers know that you're pregnant so that they'll keep that in mind when recommending or prescribing any medicines. If you were prescribed a medication before you became pregnant for an illness, disease, or condition that you still have, your doctor can help you weigh the potential benefits and risks of continuing your prescription.

If you were prescribed a medication before you became pregnant for an illness, disease, or condition that you still have, your doctor can help you weigh the potential benefits and risks of continuing your prescription.

If you become sick (for example, with a cold) or have symptoms that cause you discomfort or pain (like a headache or backache), talk to your doctor about medicines you can take and other ways to help you feel better without medication.

Also, if you are in your third trimester, talk to your health care professional if you are scheduled to have surgery or a medical procedure that would require the use of general anesthesia. The FDA has issued a warning about its possible effects on an unborn baby's brain development.

P

Recreational Drugs

Should I avoid them? Yes!

What are the risks to my baby? Pregnant women who use drugs may be placing their unborn babies at risk for:

- premature birth

- poor growth

- birth defects

- behavior and learning problems

And their babies could also be born addicted to those drugs.

What can I do about it? If you've used any drugs at any time during your pregnancy, it's important to tell your doctor. Even if you've quit, your unborn child could still be at risk for health problems. If you're still using drugs, talk to your doctor for help on how to quit. Health clinics such as Planned Parenthood also can recommend health care providers, at little or no cost, who can help you quit your habit and have a healthier pregnancy.

Smoking

Should I avoid it? Yes! You wouldn't light a cigarette, put it in your baby's mouth, and encourage your little one to puff away. As ridiculous as this sounds, pregnant women who continue to smoke are allowing their fetus to smoke too. The smoking mother passes nicotine, carbon monoxide, and many other chemicals to her growing baby.

Likewise, you should avoid people who are smoking, whether they're coworkers, friends, family members, or people in public places.

What are the risks to my baby? If a pregnant woman smokes, it could cause:

- miscarriage or stillbirth

- prematurity

- low birth weight

- sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

- asthma and other respiratory problems

And the risks to a fetus from regular exposure to secondhand smoke include low birth weight and slowed growth.

What can I do about it? If you smoke, having a baby may be the reason you need to quit. Talk to your doctor about options for kicking the habit.

If you spend time with people who smoke, ask them nicely to do it outside — and away from you if you're outside as well.

P

Artificial Sweeteners (Sugar Substitutes)

Should I avoid them? Some are OK, others are best to avoid.

Aspartame, sucralose, stevioside, and acesulfame-K have been found to be safe to use in moderation during pregnancy. However, you should avoid aspartame if you or your partner has a rare hereditary disease called phenylketonuria (PKU), in which the body can't break down the compound phenylalanine, which is found in aspartame. In that case, you should avoid aspartame altogether since your baby may also be born with the disease.

Experts are still unsure about whether saccharin, which is found in some foods and in the little pink packets, is safe to use during pregnancy — it can cross the placenta and could stay in the fetus' tissue. Also, a sweetener called cyclamate is banned in the United States because of concerns about a possible link to cancer.

Also, a sweetener called cyclamate is banned in the United States because of concerns about a possible link to cancer.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? Although some people say that the artificial sweetener aspartame is linked to birth defects and illnesses, government authorities and medical groups throughout the world have evaluated aspartame and approved it as safe for human consumption, including during pregnancy.

Research done during the 1970s suggested that saccharin caused bladder cancer in lab rats when given in large quantities. Since then, though, those studies have often been called into question. Also, a warning saying that it could cause cancer was removed from all saccharin-containing products' labels in 2000.

What can I do about it? With aspartame, sucralose, stevioside, and acesulfame-K, moderation is the key. It's OK to have an occasional diet soda or sugar-free food with these sweeteners here and there. But if you're really craving something sweet, it's probably better to have the real thing, as long as it's in moderation.

If you've already had something with saccharin in it during your pregnancy, don't obsess about it. It's highly unlikely that small amounts could harm your baby.

Still, it's wise to check product labels and try to avoid — or at least limit — anything with artificial sweeteners (especially saccharin), just to be safe. After all, this is one time in your life when you have a good reason to avoid diet foods! And the more naturally flavored whole foods you eat during pregnancy, the better.

Flying

Should I avoid it? No, not unless your due date is near or your doctor tells you that you or your baby has a medical condition that warrants keeping you near home. Women with certain health conditions — like high blood pressure (hypertension) or blood clots, a history of miscarriage, premature labor, ectopic pregnancy, or other prenatal complications — are encouraged not to fly.

Otherwise, most healthy pregnant women can fly up to 4 weeks before their due date. After that, it's best to stay close to home in case you deliver.

After that, it's best to stay close to home in case you deliver.

Note: it is recommended that pregnant women not fly to areas with high altitudes, regions with disease outbreaks, or where certain vaccines are recommended for travelers beforehand.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? For women with healthy pregnancies, there are no significant risks. However, women who have difficult pregnancies, especially involving their cardiovascular system, could be compromised by air flight and should discuss any flying plans with their doctor.

What can I do about it? Discuss any plans for lengthy or distant travel with your doctor during your last trimester, just in case. If he or she says it's OK, check with the airlines to find out what their policies are regarding flying during pregnancy. (Most airlines will allow pregnant women to fly up until week 37.)

To make sure your flight is as comfortable as possible:

- Move your lower legs regularly and/or get out of your seat (especially during long flights) to promote blood circulation and help prevent blood clots.

- Wear support stockings to further prevent clotting in your legs.

- Keep your seatbelt on when you're seated to keep the jostling of turbulence to a minimum.

Hair Dyes

Should I avoid them? No. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), because very little dye is absorbed through the skin, dying your hair is "most likely safe" during pregnancy, despite what doctors in years past may have advised. That's good news for many expectant women — coloring your hair can be a great little confidence boost when everything else going on with your body feels so out of your control.

While very few studies have closely looked at the many different kinds of hair treatments and their potential effects on a fetus, what is known shows that hair treatments are most likely safe.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? None that are currently known.

What can I do about it? If you're concerned but want to give yourself a little lift, try having your hair highlighted. This uses far fewer chemicals than dying your entire head of hair.

This uses far fewer chemicals than dying your entire head of hair.

p

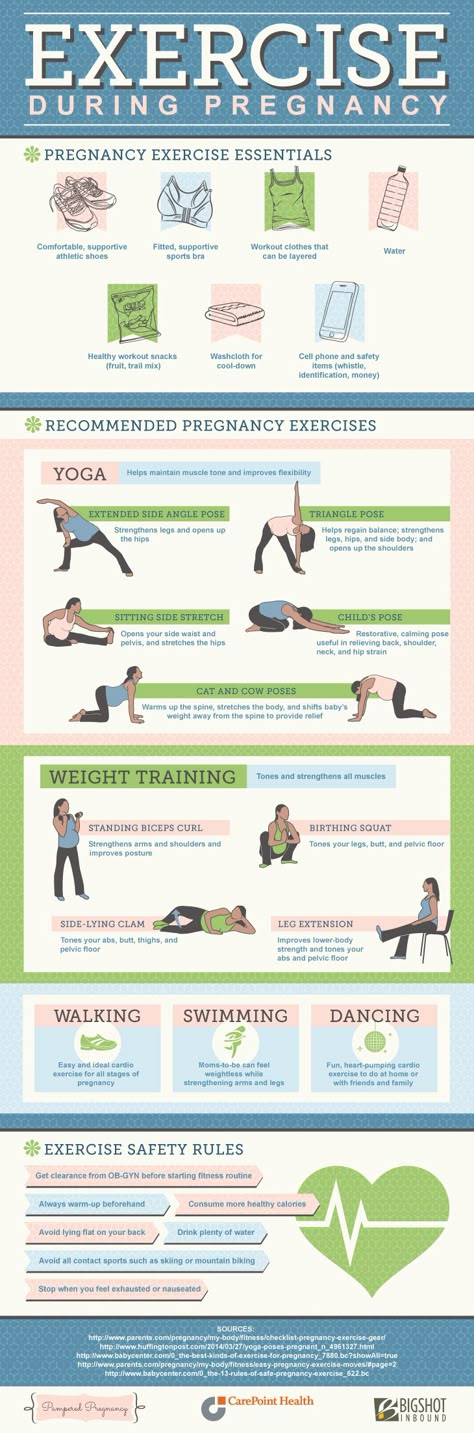

High-Impact Exercise

Should I avoid it? Yes. For most pregnant women, low-impact exercise is a great way to feel better and help prepare the body for labor. Low-impact exercise increases your heart rate and intake of oxygen while helping you avoid sudden or jarring actions that can stress your joints, bones, and muscles. Unless your doctor tells you otherwise, stick to low-impact exercise.

How much is enough? The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends at least 150 minutes (that's 2 hours and 30 minutes) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week for healthy women who are not already highly active or used to doing vigorous-intensity activity. If you were very active or did intense aerobic activities before getting pregnant you may be able to continue your exercise routine, as long as your doctor says it's safe for you and your baby.

It's wise to avoid some exercises and activities, such as:

- weight training and heavy lifting (after the first trimester)

- sit-ups (also after the first trimester)

- contact sports

- scuba diving

- bouncing

- jarring (anything that would cause a lot of up and down movement, such as horseback riding)

- leaping

- a sudden change of direction (such as downhill skiing)

- anything with an increased risk for falling, like gymnastics

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? High-impact exercise can cause increased pressure on the structures within the uterus that could lead to problems such as premature labor or bleeding.

What can I do about it? Some of the healthy ways pregnant women can stay fit include walking, swimming, water aerobics, yoga, and Pilates. But be sure to talk to your doctor before starting — or continuing — any exercise routine during pregnancy.

P

Household Chemicals

Should I avoid them? Some, yes; others, no. While chemicals like ammonia and chlorine may make you nauseated because of the smell, they're not toxic, says the March of Dimes. But others (such as some paints, paint thinners, oven cleaners, varnish removers, air fresheners, aerosols, carpet cleaners, etc.) might be.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? It depends on the product. Some household chemicals may have no effect, while others in high doses could be harmful.

What can I do about it? Here a few tips to help keep household chemicals use safe during your pregnancy:

- Talk to your doctor about any concerns you have with chemicals you use at home or at work.

- Look at product labels before using any product. If it's unsafe to use during pregnancy, the label should say that it's toxic. Find out not only if it's safe for you to use, but if it's safe for you to be around when being used by someone else. If the label doesn't specify, contact the manufacturer.

- Open windows and doors, and use rubber gloves and a mask when cleaning with or using any chemical.

- Wash your hands and arms, even if you wore gloves, after using any chemical.

- Opt for natural products like baking soda, borax, and vinegar for cleaning.

- Have someone else paint the baby's nursery, as much you'd probably like to do it yourself. And definitely don't help with the removal of paint if your home was built before 1978 as it may contain lead-based paint. Although many paints today are considered safer than those of the past, it's still a good idea to let someone else handle painting. You can always take over the decorating duties after the paint dries!

Bug Sprays (Insecticides, Pesticides, Repellents)

Should I avoid them? Yes. They're considered poisons, and pregnant women should stay away from them as much as possible.

They're considered poisons, and pregnant women should stay away from them as much as possible.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? Although the occasional household use of insecticides might not be dangerous, it's best to be careful. High levels of exposure may cause:

- miscarriage

- premature delivery

- birth defects

As for insect repellents (which may contain DEET, or diethyltoluamide), the risks aren't fully known. So, it's best to either not use them at all during pregnancy or to wear gloves to place a small amount on socks, shoes, and outer clothing instead of putting repellents directly on your skin.

What can I do about it? If you have a real problem with pesky bugs around your home, the March of Dimes suggests the following:

- Use safer methods of removal such as boric acid, which you should be able to find at your local hardware store.

- Make sure someone else applies the pesticides.

- When pesticides are sprayed outside, close all windows and turn off air-conditioning units and window fans to prevent the fumes from entering your home.

- Remove utensils, food, and dishes from areas where the chemicals will be used.

- Stay away from the treated area during the application and after for the amount of time specified on the product label.

- After pesticide use indoors, have someone else wash any treated area where food is prepared or served.

- Wear rubber gloves when gardening outside where pesticides have been used.

- Have your water supply tested regularly if you have well water and use pesticides, fertilizers, or weed killers.

P

Lead

Should I avoid it? Yes. However, exposure to high lead levels is rare for women in the United States.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? Exposure to high levels of lead can cause:

- miscarriage

- premature delivery

- low birth weight

- developmental delays

But even low levels of lead can cause subtle problems with behavior and learning in children.

What can I do about it? If your home was built before 1978, it could have lead-based paint. But it only becomes a problem if the paint is chipping, peeling, or being removed. Some homes also may have lead pipes or copper piping with lead solder that can allow lead to enter the tap water.

If you have an older home or think that you may have lead piping or soldering and are concerned about lead exposure, you can have a professional come out to test your water, the dust in your home, the soil outside, and/or the paint around your home for lead.

Make sure that anyone who removes any potentially lead-based paint from your home:

- is a professional trained in removing lead paint (getting rid of lead-based paint isn't a project for a do-it-yourselfer!)

- removes it when you're not there

- doesn't scrape, sand, or use a heat gun to remove the paint (these methods may send lead dust into the air)

- thoroughly cleans the area immediately afterward

To help reduce potential lead levels in your tap water, you can run the water for 30 seconds before using it and/or buy a water filter that specifically says on the packaging that it removes lead.

Overheating (Hot Tubs, Saunas, Electric Blankets, etc.)

Should I avoid or limit it? Yes. You should limit activities that would raise your core temperature above 102°F (38.9°C). They include:

- using saunas or hot tubs

- taking very hot, long baths and showers

- using electric blankets or heating pads

- getting a high fever

- becoming overheated when outside in hot weather or when exercising

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? If your body temperature goes above 102°F (38.9°C) for more than 10 minutes, the elevated heat can cause problems with the fetus. Overheating in the first trimester can lead to neural tube defects and miscarriage. Later in the pregnancy, it can lead to dehydration in the mother.

What can I do about it? Instead of hot tubs or saunas, take a dip in a cool pool. And it's probably a good idea to stick to warm or slightly hot baths and showers. If you have a fever during your pregnancy, talk to your doctor about ways to lower it. And follow your body's cues that you're getting overheated when exercising or enjoying the great outdoors in the warmer months.

If you have a fever during your pregnancy, talk to your doctor about ways to lower it. And follow your body's cues that you're getting overheated when exercising or enjoying the great outdoors in the warmer months.

But if you've already become overheated during your pregnancy, don't worry too much about it. Chances are, you removed yourself from the uncomfortable situation before any damage was done.

Self-Tanners, Sunless Tanners

Should I avoid them? Maybe. Although there's no proof that self-tanners are harmful to an unborn baby, there haven't been many studies done on their effects to a fetus.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? No risks specific to tanning have been documented.

What can I do about it? For a summer glow, skip the self-tanner and apply some bronzer to your face, neck, shoulders, and chest. And if you do decide to try a self-tanner, that's far safer than lying out in the sun and becoming potentially overheated. Overheating in the first trimester, as discussed above, can lead to significant problems for the baby; later in the pregnancy, it could lead to dehydration in the mother. Still, ask your doctor before applying any "tan in a bottle."

Overheating in the first trimester, as discussed above, can lead to significant problems for the baby; later in the pregnancy, it could lead to dehydration in the mother. Still, ask your doctor before applying any "tan in a bottle."

p

Sex

Should I avoid it? No. Most pregnant women having a "normal" pregnancy can continue having sex — it's perfectly safe for both mom and the baby, even up until the delivery. Of course, you'll probably need to adapt positions for your own comfort as your belly gets bigger.

Doctors may advise against sexual intercourse if they anticipate or find significant complications with a woman's pregnancy, including:

- a history or threat of miscarriage

- a history of pre-term labor (previously delivering a baby before 37 weeks) or signs indicating the risk of pre-term labor (such as premature uterine contractions)

- unexplained vaginal bleeding, discharge, or cramping

- leakage of amniotic fluid (the fluid that surrounds the baby)

- placenta previa, a condition in which the placenta (the blood-rich structure that nourishes the baby) is situated down so low that it covers the cervix (the opening of the uterus)

- incompetent cervix, a condition in which the cervix is weakened and dilates (opens) early, raising the risk for miscarriage or premature delivery

- multiple fetuses (having twins, triplets, etc.

)

)

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? You should not have sex with a partner whose sexual history is unknown to you or who may have a sexually transmitted disease (STD), such as herpes, genital warts, chlamydia, or HIV. If you become infected, the disease may be passed to your baby, with potentially dangerous effects.

What can I do about it? Talk to your doctor about any discomfort you have during or after sex or any other concerns.

Tap Water, Drinking Water

Should I avoid it? Not necessarily. Before you go out and buy a 9-month supply of bottled water, tell your doctor where you live and whether you have public water or well water.

It's also important to note that just because water is bottled doesn't necessarily mean it's safer. Although bottled water (which is regulated by the FDA) may taste better or just different, tap water meets the same Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? Different studies show different things, according to the March of Dimes. Some have found that the chlorine used to treat public water can turn into chloroform when it mixes with other materials in the water, which can increase the risk of miscarriage and poor fetal growth. But other studies have found no such links. Also of concern to some is the potential for the water to be contaminated by things like lead and pesticides. If you have well water, you should probably have it checked regularly, such as once a year, whether you're pregnant or not.

What can I do about it? If you're worried, contact your local water supplier to get a copy of the annual water quality report. If you're still concerned and/or have private well water, have your water tested by a state-certified laboratory. This can cost anywhere from $15 to hundreds of dollars, depending on the number of contaminants you want to have your water tested for.

To help ease your mind, you could also buy a water filtration system to help lower the levels of lead, some bacteria and viruses, and chemicals such as chlorine. Be sure to read the product's label, as some filters do more than others.

Countertop pitcher and faucet-mounted units are fairly inexpensive (some for under $50), whereas systems used to treat your entire home's water supply are much pricier (up to thousands of dollars). You can also have refillable water coolers delivered to your home, often through wholesale — or bulk items — stores.

p

Teeth Whiteners, Teeth Bleaching

Should I avoid them? Maybe. As with self-tanners, no good studies have been done on teeth whiteners that say for sure whether they're safe to use if you're expecting. And some makers of whitening products do caution against using them during pregnancy. Some dentists encourage waiting until after pregnancy to get your teeth whitened and others say that the procedures are safe. The concern is mostly about the chemicals used in teeth whitening products that could be swallowed and the potential effect on a fetus.

The concern is mostly about the chemicals used in teeth whitening products that could be swallowed and the potential effect on a fetus.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? There's currently no evidence that teeth whitening can harm a fetus.

What can I do about it? Talk to your doctor before using whitening products. If you'd rather wait until after your pregnancy to try to make your teeth pearly white, simply brush regularly with whitening toothpaste, which may give a little extra kick to your smile.

Vaccinations

Should I avoid them? Many, yes; others, no. It's best to wait until after your pregnancy for most vaccines, but a few are considered safe. Your doctor may say it's OK to get a vaccine if:

- there's a good chance that you could be exposed to a particular disease or infection and the benefits of vaccinating you outweigh the potential risks

- an infection would pose a risk to you or your baby

- the vaccine is unlikely to cause harm

The flu shot fits the criteria above and is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during any stage of pregnancy. Pregnant women should only get the shot made with the inactivated virus. The flu vaccine previously also came in a nasal spray (or mist) form, but it contained live strains of the virus and was never safe for moms-to-be. Currently, the nasal spray is not recommended for anyone because the CDC found that it didn't prevent cases of the flu between 2013 and 2016.

Pregnant women should only get the shot made with the inactivated virus. The flu vaccine previously also came in a nasal spray (or mist) form, but it contained live strains of the virus and was never safe for moms-to-be. Currently, the nasal spray is not recommended for anyone because the CDC found that it didn't prevent cases of the flu between 2013 and 2016.

The flu vaccine can curb flu-related problems for expectant moms, who are at higher risk of complications from the illness. And, the vaccine is safe — studies show no harmful effects to a fetus. It also helps protect a mother and her baby from getting the flu (and other viruses) in the baby's first year of life.

The Tdap vaccine (against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) is now recommended for all pregnant women in the second half of each pregnancy, regardless of whether or not they had the vaccine before, or when it was last given. This new recommendation was made in response to a rise in pertussis (whooping cough) infections, which can be fatal in newborns who have not yet had their routine vaccinations.

In addition to the flu shot and Tdap vaccine, other vaccines the CDC considers safe during pregnancy, but only if truly necessary, are:

- hepatitis B

- meningitis

- rabies

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? Live-virus vaccines — those containing a live organism — aren't recommended for pregnant women because of the risk that the actual infection or disease the vaccine is meant to prevent may be passed along to the unborn baby. However, this depends on the circumstances and whether the vaccine would ultimately be safer to receive than being exposed to the actual disease. For example, the chickenpox vaccine may be safer to your unborn baby than getting the infection. So, it's important to speak to your doctor if you believe that you may have been exposed to a disease.

For the most part, though, researchers don't know what the risks of some vaccines may be to a fetus. So, it's wise to just wait to be vaccinated unless your doctor tells you otherwise.

What can I do about it? Be sure to talk to your doctor before getting any vaccination during pregnancy. Also tell your doctor if you became pregnant within 4 weeks of having a vaccine. And if your workplace requires certain vaccines, be sure to let them know you're pregnant before agreeing to be immunized.

P

X-Rays

Should I avoid them? Yes and no. If your doctor thinks it's truly necessary — for your own well-being or your baby's — to get one during your pregnancy, then it's highly unlikely that low levels of X-ray radiation will be harmful. However, if you can safely wait to get an X-ray until after your baby is born, then that's probably the best way to go.

What are the risks, if any, to my baby? Health experts say that X-rays are most likely safe during pregnancy. Most diagnostic X-rays emit much less than 5 rads, which is the limit of what the FDA suggests a pregnant woman should be exposed to.

Different imaging studies use different amounts of radiation and the direction of the X-ray beam also affects the possible exposure to the fetus. Dental X-rays, for example, aren't cause for much concern because the X-ray area is far from the uterus.

What can I do about it? Researchers believe that a fetus is more at risk for damage by radiation because of the rapid rate with which its cells are dividing. Always make sure that your health care providers (including your dentist and the X-ray technician) know about your pregnancy before you get an X-ray. Also make sure that your stomach is covered with a lead apron.

If you're concerned and would rather not get an X-ray at all during pregnancy, your doctor may be able to use an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) test during the first trimester or an ultrasound anytime.

Keeping Things in Perspective

Although some things are unsafe during pregnancy, try not to spend too much time wondering and worrying. When in doubt, just use common sense — if it seems like a bad idea, doesn't need to be done right now, or might be risky, hold off at least until you've talked with your doctor about it. He or she can likely help ease your mind and may even say it's fine to do something you never expected to be able to do until after your special delivery.

When in doubt, just use common sense — if it seems like a bad idea, doesn't need to be done right now, or might be risky, hold off at least until you've talked with your doctor about it. He or she can likely help ease your mind and may even say it's fine to do something you never expected to be able to do until after your special delivery.

Above all, make sure to follow the most important healthy pregnancy habits — eat right; get plenty of rest; steer clear of drugs, alcohol, and tobacco — and you'll be well on your way to keeping both you and your baby healthy.

During Pregnancy | CDC

- Preventing Problems

- Genetics and Family History

- Other Concerns

- Things to Think About Before Baby Arrives

Congratulations, you’re pregnant! Pregnancy is an exciting time, but it can also be stressful. Knowing that you are doing all you can to stay healthy during pregnancy and give your baby a healthy start in life will help you to have peace of mind.

What Are Steps You Can Take Toward a Healthy Pregnancy?

Folic Acid: Folic acid is a B vitamin that can help prevent major birth defects. Take a vitamin with 400 micrograms (mcg) of folic acid every day, before and during pregnancy.

Smoking: The best time to quit smoking is before you get pregnant, but quitting at any time during pregnancy can help your baby get a better start on life. Learn more about the dangers of smoking and find help to quit.

Alcohol: A baby can be exposed to the same level of alcohol as the mother during pregnancy. There is no known safe amount of alcohol use during pregnancy.

Marijuana Use: Marijuana use during pregnancy can be harmful to your baby’s health. The chemicals in marijuana (in particular, tetrahydrocannabinol or THC) pass through your system to your baby and can harm your baby’s development.

Vaccinations: Did you know a baby gets disease immunity (protection) from mom during pregnancy? This immunity can protect baby from some diseases during the first few months of life, but immunity decreases over time.

Infections: You won’t always know if you have an infection—sometimes you won’t even feel sick. Learn how to help prevent infections that could harm your developing baby.

HIV: If you are pregnant or are thinking about becoming pregnant, get a test for HIV as soon as possible and encourage your partner to get tested as well. If you have HIV and you are pregnant, there is a lot you can do to keep yourself healthy and not give HIV to your baby.

West Nile Virus: Take steps to reduce your risk for West Nile virus and other mosquito-borne infections.

Diabetes: Poor control of diabetes during pregnancy increases the chance for birth defects and other problems for your baby. It can cause serious complications for you, too.

High Blood Pressure: Existing high blood pressure can increase your risk of problems during pregnancy.

Medications: Taking certain medications during pregnancy might cause serious birth defects for your baby. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about any medications you are taking. These include prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary or herbal supplements.

These include prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary or herbal supplements.

Depression: Depression is common and treatable. If you think you have depression, seek treatment from your health care provider as soon as possible.

Emergencies: Did you know that when you’re pregnant you might need additional supplies or need to protect yourself during an emergency? Public health emergencies can affect access to medical and social services, increase stress, intensify physical work, and expand caregiving duties.

Environmental and Workplace Exposures: There are some common environmental and workplace hazards that could be harmful to pregnant or breastfeeding people, or to household members when carried home on clothes, skin, and shoes. Talk to your doctor or your employer about what you are exposed to at work.

- The Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Units (PEHSUs) are a direct link to medical and health professionals. Because environmental factors can impact health of children and reproductive age adults, the PEHSU network has experts in pediatrics, allergy/immunology, neurodevelopment, toxicology, occupational and environmental medicine, nursing, reproductive health and other specialized areas.

There are regional specialists across the country to answer your questions.

There are regional specialists across the country to answer your questions. - The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) has many fact sheets about toxic substances (e.g, lead, benzene) if you have concerns about toxic exposures.

Radiation: If you think you might have been exposed to radiation, talk with your doctor.

Top of Page

How Do Genetics and Family History Affect Pregnancy?

Genetics: Understanding genetic factors and genetic disorders is important for learning more about preventing birth defects, developmental disabilities, and other unique conditions in children.

- Family History: Family members share their genes and their environment, lifestyles, and habits. A family history can help identify possible disease risks for you and your baby.

- Genetic Counselor: Your doctor might suggest that you see a genetic counselor if you have a family history of a genetic condition or have had several miscarriages or infant deaths.

Top of Page

Top of Page

What Are Other Concerns During Pregnancy?

Bleeding and Clotting Disorders: Bleeding and clotting disorders can cause serious problems during pregnancy, including miscarriage. If you have a bleeding or clotting disorder, talk with your doctor.

Disaster Safety for Expecting and New Parents: Learn general tips to get prepared before a disaster and what to do in case of a disaster to help keep you and your family safe and healthy.

Premature Birth: Important growth and development occur throughout pregnancy – all the way through the final months and weeks. Babies born three or more weeks earlier than their due date have greater risk of serious disability or even death. Learn the warning signs and how to prevent a premature birth.

Travel: If you are planning a trip within the country or internationally, talk to your doctor first. Travel might cause problems during pregnancy. Also, find out about the quality of medical care at your destination and during transit.

Violence and Pregnancy: Violence can lead to injury and death among women in any stage of life, including during pregnancy. Learn more about violence against women, and find out where to get help. Top of Page

What Are Other Things to Think About Before the Baby Arrives?

Breastfeeding: You and your baby gain many benefits from breastfeeding. Breast milk is easy to digest and has antibodies that can protect your baby from bacterial and viral infections.

Jaundice and Kernicterus: Any baby can get jaundice. Severe jaundice that is not treated can cause brain damage. Your baby should be checked for jaundice in the hospital and again within 48 hours after leaving the hospital. If you think your baby has jaundice, call and visit your baby’s doctor right away.

Newborn Screening: Within 48 hours of your baby’s birth, a sample of blood is taken from a “heel stick,” and the blood is tested for treatable diseases. More than 98% of all children born in the United States are tested for these disorders.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): Learn what parents and caregivers can do to help babies sleep safely and reduce the risk of sleep-related infant deaths, including SIDS.

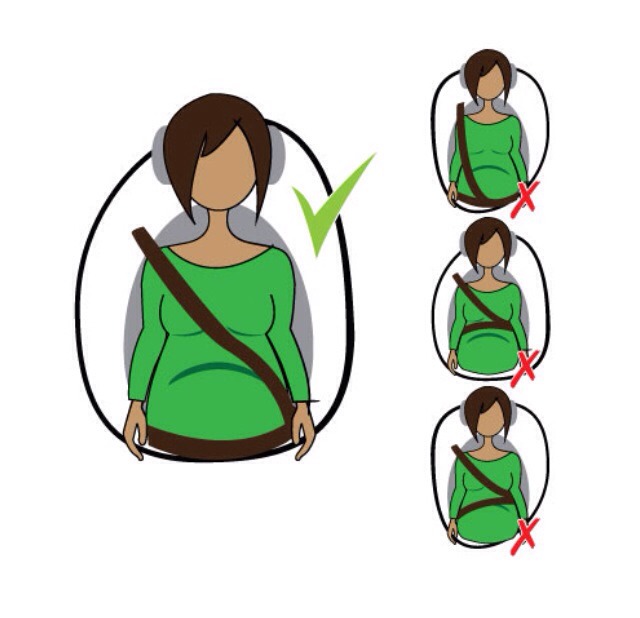

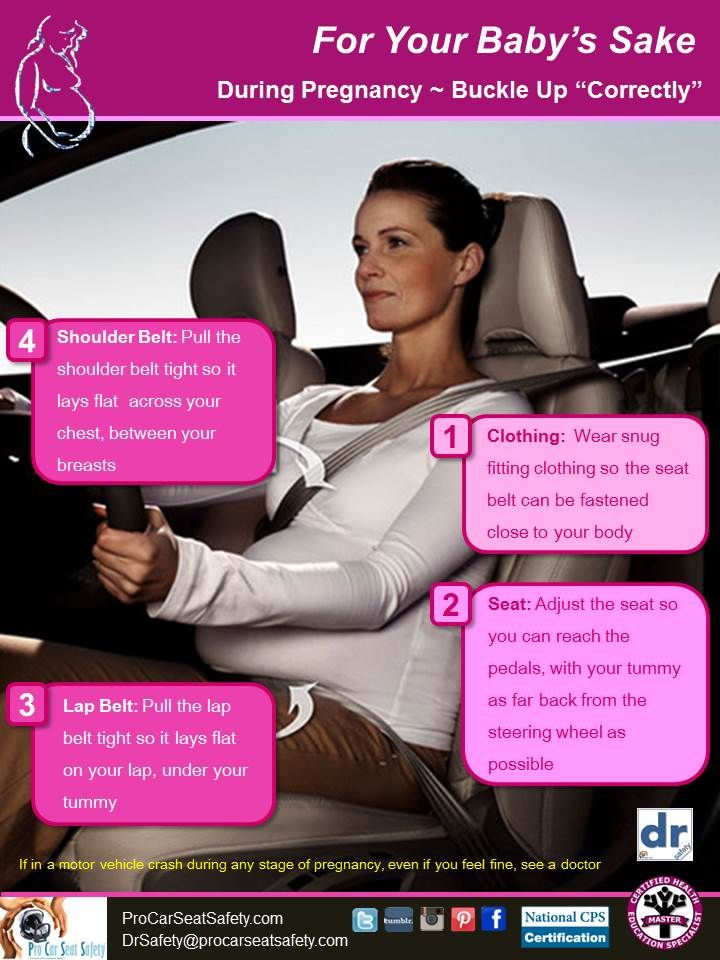

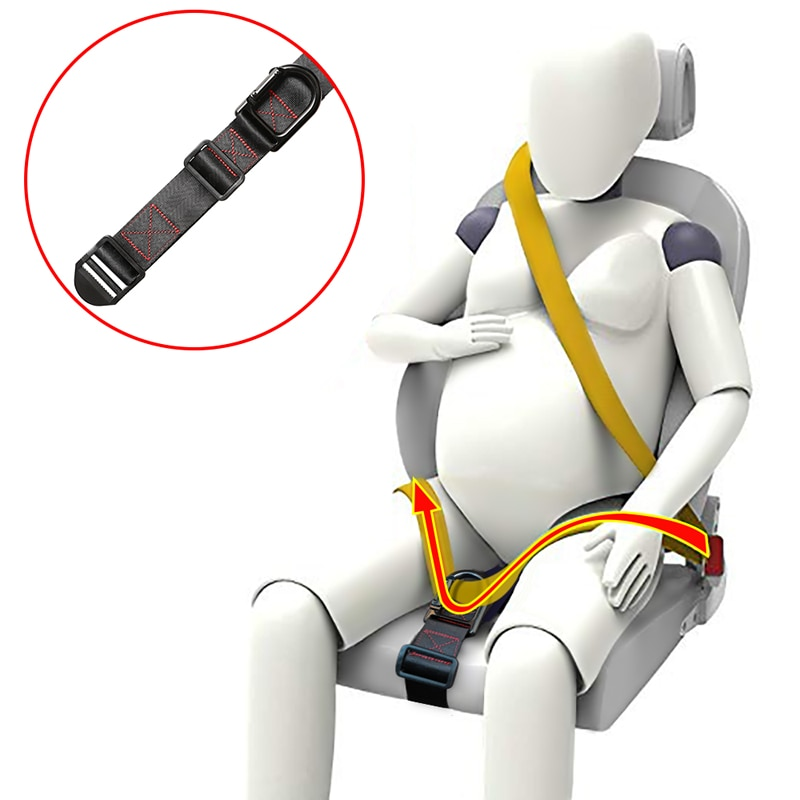

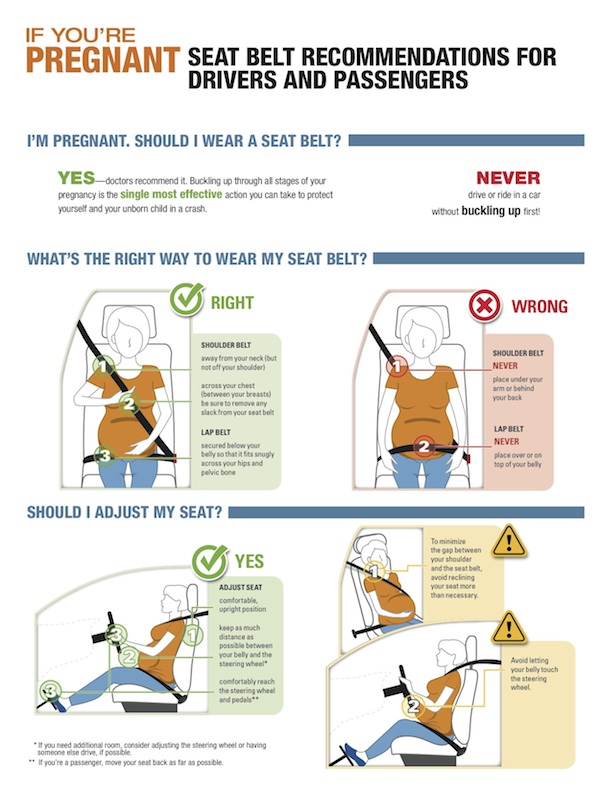

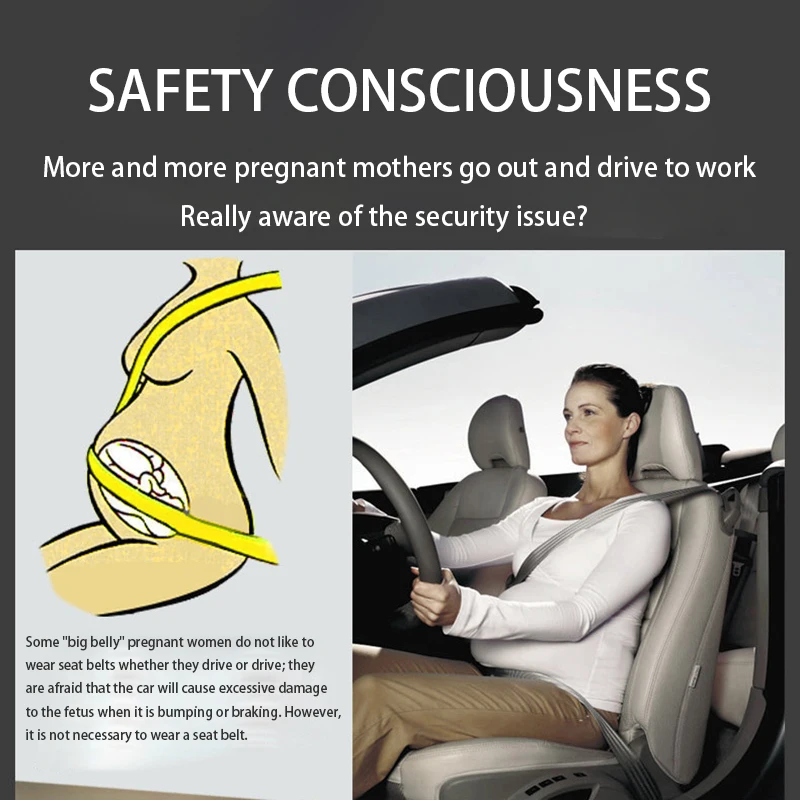

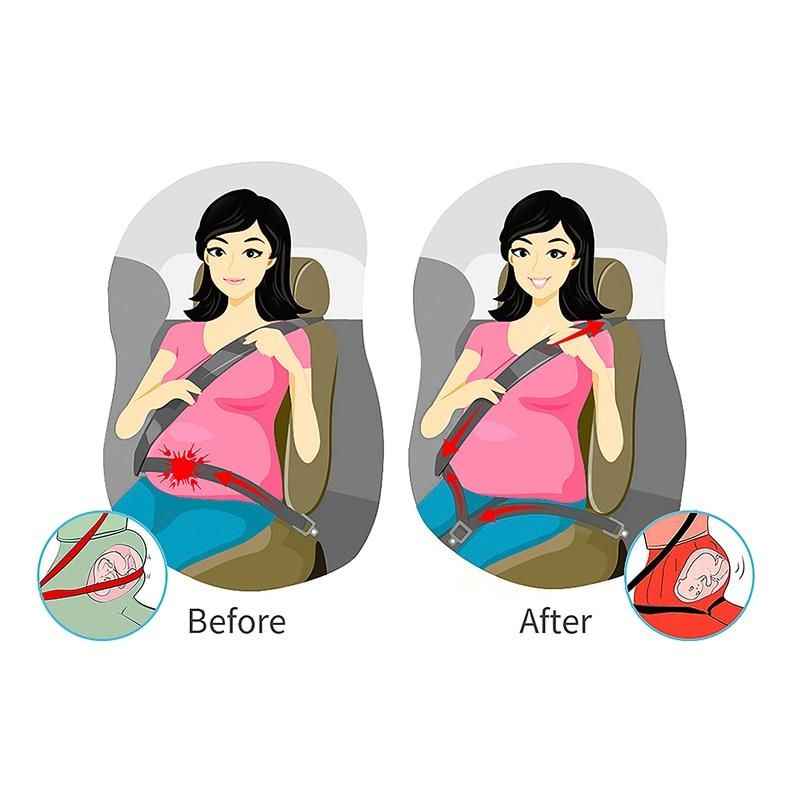

Child Safety Seats: Motor vehicle injuries are a leading cause of death among children in the United States. But many of these deaths can be prevented. Always buckling children in age- and size-appropriate car seats, booster seats, and seat belts reduces serious and fatal injuries by up to 80%. Top of Page

Pharmacological safety in pregnancy: a systematic review of the use of potentially teratogenic drugs | Reshetko

1. Koren G. Ethical framework for observational studies of medicinal drug exposure in pregnancy. Teratology. 2002;65(4):191–195. doi:10.1002/tera.10038.

2. Buhimschi CS, Weiner CP. Medications in pregnancy and lactation: Part 2. Drugs with minimal or unknown human teratogenic effect. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):417–432. doi: 10.1097/ AOG.0b013e31818d686c.

3. Ehrenstein V, Sorensen HT, Bakketeig LS, Pedersen L. Medical databases in studies of drug teratogenicity: methodological issues. Clin epidemiol. 2010;2:37–43. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S9304.

Ehrenstein V, Sorensen HT, Bakketeig LS, Pedersen L. Medical databases in studies of drug teratogenicity: methodological issues. Clin epidemiol. 2010;2:37–43. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S9304.

4. Carey JC, Martinez L, Balken E, et al. Determination of human teratogenicity by the astute clinician method: review of illustrative agents and a proposal of guidelines. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85(1):63–68. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20533.

5. Lo WY, Friedman JM. Teratogenicity of recently introduced medications in human pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(3):465–473. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200209000-00012.

6. Adam MP, Polifka JE, Friedman JM. Evolving knowledge of the teratogenicity of medications in human pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157C(3):175–182. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30313.

7. Addis A, Sharabi S, Bonati M. Risk classification systems for drug use during pregnancy are they a reliable source of information? drug safe. 2000;23(3):245–253. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200023030-00006.

doi: 10.2165/00002018-200023030-00006.

8. Buhimschi CS, Weiner CP. Medications in pregnancy and lactation: part 1. Teratology. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):166–188. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818d6788. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jun;113(6):1377.

9. Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(4):241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00250.x.

10. Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Dose-dependent teratogenicity of valproate in mono- and polytherapy: an observational study. Neurology. 2015;85(10):866–872. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001772.

11. Brent RL. Environmental causes of human congenital malformations: the pediatrician’s role in dealing with these complex clinical problems caused by a multiplicity of environmental and genetic factors. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4 Suppl):957–968. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.S1.957.

12. van Gelder MM, van Rooij IA, Miller RK, et al. Teratogenic mechanisms of medical drugs. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):378–394. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp052.

Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):378–394. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp052.

13. van Gelder MM, de Jong-van den Berg LT, Roeleveld N. Drugs associated with teratogenic mechanisms. Part II: a literature review of the evidence on human risks. Hum reproduction. 2014;29(1):168–183. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det370.

14. Daw JR, Mintzes B, Law MR, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy: a retrospective, population-based study in British Columbia, Canada (2001-2006). Clin Ther. 2012;34(1):239–249. doi: 10.1016/j. clinthera.2011.11.025.

15. van Gelder MM, Bos JH, Roeleveld N, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Drugs associated with teratogenic mechanisms. Part I: dispensing rates among pregnant women in the Netherlands, 1998-2009. Hum reproduction. 2014;29(1):161–167. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det369.

16. Zomerdijk IM, Ruiter R, Houweling LM, et al. Dispensing of potentially teratogenic drugs before conception and during pregnancy: a population-based study. BJOG. 2015;122(8):1119–1129. doi: 10. 1111/1471-0528.13128.

1111/1471-0528.13128.

17. Mitchell AA. Adverse drug reactions in utero: perspectives on teratogens and strategies for the future. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):781–783. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.52.

18. Schwarz EB, Moretti ME, Nayak S, Koren G. Risk of hypospadias in offspring of women using loratadine during pregnancy a systematic review and meta-analysis. drug safe. 2008;31(9):775-788. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831090-00006.

19. Riley EH, Fuentes-Afflick E, Jackson RA, et al. Correlates of prescription drug use during pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2005;14(5):401–409. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.401.

20. Egen-Lappe V, Hasford J. Drug prescription in pregnancy: analysis of a large statutory sickness fund population. Eur J Clinic Pharmacol. 2004;60(9):659–666. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0817-1.

21. Beyens MN, Guy C, Ratrema M, Ollanger M. Prescription of drugs to pregnant women in France: the HIMAGE study. therapy. 2003;58(6):505–511. doi:10.2515/therapie:2003082.

22. Andrade SE, Gurwitz JH, Davis RL, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(2):398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.025.

23. Cooper WO, Hickson GB, Ray WA. Prescriptions for contraindicated category X drugs in pregnancy among women enrolled in TennCare. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18(2):106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2003.00542.x.

24. Lacroix I, Damase-Michel C, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL. Prescription of drugs during pregnancy in France. Lancet. 2000;356(9243):1735–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03209-8.

25. Schirm E, Meijer WM, Tobi H, de Jong-van den Berg L. Drug use by pregnant women and comparable non-pregnant women in the Netherlands with reference to the Australian classification system. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;114(2):182–188. doi: 10.1016/j. ejogrb.2003.10.024.

26. Olesen C, Sorensen HT, de Jong-van den Berg L, et al. Prescribing during pregnancy and lactation with reference to the Swedish classification system. A population-based study among Danish women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(8):686–692. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.1999.780805.x.

A population-based study among Danish women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(8):686–692. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.1999.780805.x.

27. Malm H, Martikainen J, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ. Prescription of hazardous drugs during pregnancy. drug safe. 2004;27(12):899–908. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200427120-00006.

28. Daw JR, Hanley GE, Greyson DL, Morgan SG. Prescription drug use during pregnancy in developed countries: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(9):895–902. doi: 10.1002/pds.2184.

29. Reshetko O.V., Lutsevich K.A. Systematic review of drug use during pregnancy. I. Design and methodological quality of research // Clinical pharmacology and therapy. - 2015. - T.24. - No. 1 - S. 66–71. [Reshetko OV, Lutsevich KA. Systematic review of drug use during pregnancy. I. Design and methodological quality of studies. Clinical farmakologiya i terapiya. 2015;24(1):66–71. (In Russ).]

30. Reshetko O.V., Lutsevich K.A. Systematic review of drug use during pregnancy. II. Antenatal consumption and assessment of the benefit/risk profile. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy. - 2015. - T.24. - No. 2 - S. 82–90. [Reshetko OV, Lutsevich KA. Use of drugs during pregnancy: a systematic review. II. Antenatal consumption and evaluation of the risk-benefit profiles of pharmaceuticals. Clinical farmakologiya i terapiya. 2015;24(2):82–91. (In Russ).]

II. Antenatal consumption and assessment of the benefit/risk profile. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy. - 2015. - T.24. - No. 2 - S. 82–90. [Reshetko OV, Lutsevich KA. Use of drugs during pregnancy: a systematic review. II. Antenatal consumption and evaluation of the risk-benefit profiles of pharmaceuticals. Clinical farmakologiya i terapiya. 2015;24(2):82–91. (In Russ).]

31. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

32. whocc.no [Internet]. WHO Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2011. Oslo; 2010 [cited 2017 Apr 12]. Available from: http://www. whocc.no/filearchive/publications/2011guidelines.pdf

33. fda.gov [Internet]. Department of Health and Human Services. federal register. Requirements on content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products. 2006 Vol. 71, no. 15.p. 3921–3997 [cited 2017 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.fda. gov/ohrms/docets/98fr/06-545.pdf

Requirements on content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products. 2006 Vol. 71, no. 15.p. 3921–3997 [cited 2017 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.fda. gov/ohrms/docets/98fr/06-545.pdf

34. Classification of medicinal products for use during pregnancy and lactation: the Swedish systems. Kungsbacka, Sweden: LINFO, Drug Information Ltd; 1993.

35. Australian Drug Evaluation Committee. Medicines in Pregnancy Working Party. Prescribing medicines in pregnancy: an Australian categorization of risk of drug use in pregnancy. 4th ed. Canberra: Publications Unit, Therapeutic Goods Administration; 1999.75p.

36. Doering PL, Boothby LA, Cheok M. Review of pregnancy labeling of prescription drugs: is the current system adequate to inform of risks? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(2):333–339. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.125740.

37. Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. 9th ed. Philadelphia: LWW; 2011. 1728 p.

9th ed. Philadelphia: LWW; 2011. 1728 p.

38. Friedman JM, Polifka JE. Micromedex Reproductive Risk Information System (REPRORISK). Englewood, Colorado: Thomson MICROMEDEX; 2011.

39. Scialli AR, Buelke-Sam JL, Chambers CD, et al. Communicating risks during pregnancy: a workshop on the use of data from animal develop-mental toxicity studies in pregnancy labels for drugs. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70(1):7–12. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10150.

40. Andrade SE, Raebel MA, Morse AN, et al. Use of prescription medications with a potential for fetal harm among pregnant women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(8):546–554. doi: 10.1002/pds.1235.

41. Hardy JR, Leaderer BP, Holford TR, et al. Safety of medications prescribed before and during early pregnancy in a cohort of 81,975 mothers from the UK general practice research database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(8):555–564. doi:10.1002/pds.1269.

42. Bakker MK, Jentink J, Vroom F, et al. Drug prescription patterns before, during and after pregnancy for chronic, occasional and pregnancy-related drugs in the Netherlands. BJOG. 2006;113(5):559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00927.x.

BJOG. 2006;113(5):559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00927.x.

43. Sharma R, Kapoor B, Verma U. Drug utilization pattern during pregnancy in North India. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60(7):277–287. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.26602.

44. Al-Humayyd MS, Babay ZH. Pattern of drug prescribing during pregnancy in Saudi women: a retrospective study. Saudi Pharm J. 2006;14(3–4):201–207.

45. Basgul A, Akici A, Uzuner A, et al. Drug utilization and teratogenicity risk categories during pregnancy. Ad Ther. 2007;24(1):68–80. doi:10.1007/bf02849994.

46. Rohra DK, Das N, Azam SI, et al. Drug-prescribing patterns during pregnancy in the tertiary care hospitals of Pakistan: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-24.

47. Gagne JJ, Maio V, Berghella V, et al. Prescription drug use during pregnancy: a population-based study in Regione Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Eur J Clinic Pharmacol. 2008;64(11):1125–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0546-y.

48. Wen SW, Yang T, Krewski D, et al. Patterns of pregnancy exposure to FDA prescription C, D and X drugs in a Canadian population. J. Perinatol. 2008;28(5):324–329. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.6.

49. Yang T, Walker MC, Krewski D, et al. Maternal characteristics associated with pregnancy exposure to FDA category C, D, and X drugs in a Canadian population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(3):270–277. doi: 10.1002/pds.1538.

50. Kulaga S, Zagarzadeh A, Berard A. Prescriptions filled during pregnancy for drugs with the potential of fetal harm. BJOG. 2009;116(13):1788–1795. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02377.x.

51. Kebede B, Gedif T, Getachew A. Assessment of drug use among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(6):462–468. doi: 10.1002/pds.1732.

52. Potchoo Y, Redah D, Gneni MA, Guissou IP. Prescription drugs among pregnant women in Lome, Togo, West Africa. Eur J Clinic Pharmacol. 2009;65(8):831–838. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0644-5.

53. Colvin L, Slack-Smith L, Stanley FJ, Bower C. Pharmacovigilance in pregnancy using population-based pregnancy linked datasets. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(3):211–225. doi: 10.1002/pds.1705.

54. Irvine L, Flynn RW, Libby G, et al. Drugs dispensed in primary care during pregnancy: a record-linkage analysis in Tayside, Scotland. drug safe. 2010;33(7):593–604. doi: 10.2165/11532330-000000000-00000.

55. Cleary BJ, Butt H, Strawbridge JD, et al. Medication use in early pregnancy -prevalence and determinants of use in a prospective cohort of women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(4):408–417. doi: 10.1002/pds.1906.

56. Artama M, Gissler M, Malm H, et al. Nationwide register-based surveillance system on drugs and pregnancy in Finland 1996–2006. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(7):729–738. doi: 10.1002/pds.2159.

57. Autret-Leca E, Deligne J, Leve J, et al. Drug exposure during the periconceptional period: a study of 1793 women. Pediatric Drugs. 2011;13(5):317–324. doi: 10.2165/11591260-000000000-00000.

2011;13(5):317–324. doi: 10.2165/11591260-000000000-00000.

58. Al-Riyami IM, Al-Busaidy IQ, Al-Zakwani IS. Medication use during pregnancy in Omani women. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):634–641. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9517-y.

59. Bertoldi AD, da Silva Dal Pizzol T, Camargo AL, et al. Use of medicines with unknown fetal risk among parturient women from the 2004 Pelotas Birth Cohort (Brazil). J Pregnancy. 2012;2012:257597. doi: 10.1155/2012/257597.

60. Odalovic M, Vezmar Kovacevic S, Ilic K, et al. Drug use before and during pregnancy in Serbia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(5):719–727. doi: 10.1007/s11096-012-9665-8.

61. Thorpe PG, Gilboa SM, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Medications in the first trimester of pregnancy: most common exposures and critical gaps in understanding fetal risk. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(9):1013–1018. doi: 10.1002/pds.3495.

62. Admasie C, Wasie B, Abeje G. Determinants of prescribed drug use among pregnant women in Bahir Dar city administration, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-325.

BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-325.

63. Dillon P, O'Brien KK, McDonnell R, et al. Prevalence of prescribing in pregnancy using the Irish primary care research network: a pilot study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:67. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0489-0.

64. Palmsten K, Hernandez-Diaz S, Chambers CD, et al. The most commonly dispensed prescription medications among pregnant women enrolled in the U.S. Medicaid Program. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):465–473. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000982.

65. Brent RL. Nongenital malformations following exposure to pro-gestational drugs: the last chapter of an erroneous allegation. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73(11):906–918. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20184.

66. Scholl TO. Iron status during pregnancy: setting the stage for mother and infant. Am J Clinic Nutr. 2005;81(5):1218S–1222S.

67. Smith JM, Lowe RF, Fullerton J, et al. An integrative review of the side effects related to the use of magnesium sulfate for preeclampsia and eclampsia management. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-34.

BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-34.

68. Orioli IM, Castilla EE. Epidemiological assessment of misoprostol teratogenicity. BJOG. 2000;107(4):519-523. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13272.x.

69. Raebel MA, Ellis JL, Andrade SE. Evaluation of gestational age and admission date assumptions used to determine prenatal drug exposure from administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(12):829–836. doi: 10.1002/pds.1100.

70. de Jonge L, de Walle HE, de Jong-van den Berg LT, et al. Actual use of medications prescribed during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study using data from a population-based congenital anomaly registry. drug safe. 2015;38(8):737–747. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0302-z.

71. Colvin L, Slack-Smith L, Stanley FJ, Bower C. Linking a pharmaceutical claims database with a birth defects registry to investigate birth defect rates of suspected teratogens. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(11):1137–1150. doi: 10. 1002/pds.1995.

1002/pds.1995.

72. Feibus KB. FDA's proposed rule for pregnancy and lactation labeling: improving maternal child health through well-informed medicine use. J Med Toxicol. 2008;4(4):284–288. doi: 10.1007/bf03161214.

73. Ramoz LL, Patel-Shori NM. Recent changes in pregnancy and lactation labeling: retirement of risk categories. pharmaceutical therapy. 2014;34(4):389–395. doi: 10.1002/phar.1385.

74. Mazer-Amirshahi M, Samiee-Zafarghandy S, Gray G, van den Anker JN. Trends in pregnancy labeling and data quality for US-approved pharmaceuticals. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):690.e1–690.e11. doi:

75. 1016/j.ajog.2014.06.013.

76. Broussard CS, Frey MT, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Developing a systematic approach to safer medication use during pregnancy: summary of a Center for Disease Control and Prevention-convened meeting. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(3):208.e1–214.e1. doi: 10.1016/j. ajog.2014.05.040.

77. Kallen B. The problem of confounding in studies of the effect of maternal drug use on pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:148616. doi: 10.1155/2012/148616.

Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:148616. doi: 10.1155/2012/148616.

78. Eltonsy S, Martin B, Ferreira E, Blais L. Systematic procedure for the classification of proven and potential teratogens for use in research. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2016;106(4):285–297. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23491.

79. Peters SL, Lind JN, Humphrey JR, et al. Safe lists for medications in pregnancy: inadequate evidence base and inconsistent guidance from Web-based information, 2011. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(3):324–328. doi: 10.1002/pds.3410.

80. Obican S, Scialli AR. Teratogenic exposures. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157C(3):150–169. doi:10.1002/ajmg. c.30310.

Pharmacological safety in pregnancy: principles of teratogenesis and teratogenicity of drugs | Reshetko

1. Alfirevic A, Alfirevic Z, Pirmohamed M. Pharmacogenetics in reproductive and perinatal medicine. Pharmacogenomics. 2010; 11(1):65–79. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.153.

2. Parisi MA, Spong CY, Zajicek A, Guttmacher A. We don’t know what we don’t study: the case for research on medication effects in pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157(3): 247–250. doi:10.1002/ajmg. c.30309.

We don’t know what we don’t study: the case for research on medication effects in pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157(3): 247–250. doi:10.1002/ajmg. c.30309.

3. Wilffert B, Altena J, Tijink L, et al. Pharmacogenetics of druginduced birth defects: what is known so far? Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(4):547–558. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.201.

4. Einarson A. Studying the safety of drugs in pregnancy: and the gold standard is. J Clin Pharmacol Pharmacoepidemiol. 2010;1:3–8.

5. Schachter AD, Kohane IS. Drug target gene signatures that predict teratogenicity are enriched for developmentally related genes. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31(4):562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.11.008.

6. Mitchell AA. Adverse drug reactions in utero: perspectives on teratogens and strategies for the future. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):781–783. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.52.

7. Obican S, Scialli AR. Teratogenic exposures. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157(3):150–169. doi:10.1002/ajmg. c.30310.

doi:10.1002/ajmg. c.30310.

8. Sher SA Teratogenic effects of drugs on the body of the unborn child at the stage of intrauterine development // Pediatric pharmacology. - 2011. - T. 8. - No. 6. - S. 57–60. [Sher SA. Teratogenic effects of drugs on the organism of a future child during fetal stage of development. Pediatricheskaya farmakologiya. 2011;8(6):57–60. (In Rus).]

9. Ivanova A. A., Mikhailov A. V., Kolbin A. S. Teratogenic properties of drugs. Background // Pediatric pharmacology. - 2013. - T. 10. - No. 1. - S. 46–53. [Ivanova AA, Mikhailov AV, Kolbin AS. Teratogenic properties of drugs. background information. Pediatricheskaya farmakologiya. 2013;10(1): 46–53. (In Rus).] doi: 10.15690/pf.v10i1.588.

10. WHO/CDC/ICBDSR. Birth defects surveillance: a manual for program managers [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefectscount/documents/bd-surveillance-manual.pdf.

11. De Vane L, Goetzl LM, Ramamoorthy S. Exposing fetal drug exposure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):786–788. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.67.

Exposing fetal drug exposure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):786–788. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.67.

12. Blumenfeld YJ, Reynolds-May MF, Altman RB, El-Sayed YY. Maternal fetal and neonatal pharmacogenomics: a review of the current literature. J. Perinatol. 2010;30:571–579. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.183.

13. Nordeng H, Ystrom E, Eberhard-Gran M. Medication safety in pregnancy — Results from the MoBa study. norsk epidemiology. 2014;24:161–168.

14. Jelinek R. The contribution of new findings and ideas to the old principles of teratology. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;20(3):295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.03.011.

15. Friedman JM. The principles of teratology: are they still true? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88(10):766–768. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20697.

16. Friedman JM. How do we know if an exposure is actually teratogenic in humans? Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157(3):170–174. doi:10.1002/ajmg. c.30302.

17. Shepard TH. "Proof" of human teratogenicity. Teratology. 1994;50:97–98.

Teratology. 1994;50:97–98.

18. Holmes LB. Human teratogens: Update 2010. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20748.

19. Wilson RD, Johnson JA, Summers A, et al. Principles of human teratology: drug, chemical and infectious exposure. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(11):911–917. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32668-8.

20. Uhl K, Trontell A, Kennedy D. Risk minimization practices for pregnancy prevention: understanding risk, selecting tools. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(3):337–348. doi: 10.1002/pds.1312.

21. Zhu H, Kartiko S, Finnell RH. Importance of gene-environment interactions in the etiology of selected birth defects. Clin Genet. 2009;75(5):409–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01174.x.

22. Kalter H. Teratology in the twentieth century. Congenital malformations in humans and how their environmental causes were established. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2003.

23. Van Gelder MMHJ, Van Rooij IALM, Miller RK, et al. Teratogenic mechanisms of medical drugs. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4): 378–394. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp052.

Teratogenic mechanisms of medical drugs. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4): 378–394. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp052.

24. van der Put NMJ, van Straaten HWM, Trijbels FJM, Blom HJ. Folate, homocysteine and neural tube defects: an overview. Exp Biol Med. 2001;226(4):243–270.

25. Czeizel AE. Periconceptional folic acid and multivitamin supplementation for the prevention of neural tube defects and other congenital abnormalities. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85(4):260–268. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20563.

26. Botto LD, Yang Q. 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene variants and congenital anomalies: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(9):862–877. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010290.

27. van der Linden IJM, den Heijer M, Afman LA, et al. The methionine synthase reductase 66A>G polymorphism is a maternal risk factor for spina bifida. J Mol Med. 2006;84(12):1047–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0093-x.

28. van Beynum IM, Kapusta L, den Heijer M, et al. Maternal MTHFR 677C>T is a risk factor for congenital heart defects: effect modification by periconceptional folate supplementation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(8):981–987. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi815.

Maternal MTHFR 677C>T is a risk factor for congenital heart defects: effect modification by periconceptional folate supplementation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(8):981–987. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi815.

29. Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Walker AM, et al. Folic acid antagonists during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1608–1614. doi: 10.1056/name200011303432204.

30. Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Walker AM, Mitchell AA. Neural tube defects in relation to use of folic acid antagonists during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(10):961–968. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.10.961.

31. Meijer WM, de Walle HEK, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, et al. Folic acid sensitive birth defects in association with intrauterine exposure to folic acid antagonists. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;20(2):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.01.008.

32. Malm H, Kajantie E, Kivirikko S, et al. Valproate embryopathy in three sets of siblings: further proof of hereditary susceptibility. Neurology. 2002;59(4):630–633. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.630.

Neurology. 2002;59(4):630–633. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.630.

33. Kini U, Lee R, Jones A, et al. Influence of the MTHFR genotype on the rate of malformations following exposure to antiepileptic drugs in utero. Eur J Med Genet. 2007;50(6):411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2007.08.002.

34. Stoller JZ, Epstein JA. Cardiac neural crest. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16(6):704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.06.004.

35. Duester G. Families of retinoid dehydrogenases regulating vitamin A function: production of visual pigment and retinoic acid. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(14):4315–4324. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01497.x.

36. Fujii H, Sato T, Kaneko S, et al. Metabolic inactivation of retinoic acid by a novel P450 differentially expressed in developing mouse embryos. EMBO J. 1997;16(14):4163–4173. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4163.

37. Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, Poskanzer DC. Adenocarcinoma of the vagina: association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. N Engl J Med. 1971;284(16): 878–881. doi: 10.1056/name197104222841604.

N Engl J Med. 1971;284(16): 878–881. doi: 10.1056/name197104222841604.

38. Hernandez-Diaz S, Mitchell AA, Kelley KE, et al. Medications as a potential source of exposure to phthalates in the U. S. population. Environ Health Perspective. 2009;117(2):185–189. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11766.

39. Giwercman A, Rylander L, Giwercman YL. Influence of endocrine disruptors on human male fertility. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007; 15(6):633–642. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60530-5.

40. Diav-Citrin O, Park YH, Veerasuntharam G, et al. The safety of mesalamine in human pregnancy: a prospective controlled cohort study. gastroenterology. 1998;114(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70628-6.

41. Gill SK, O'Brien L, Einarson TR, et al. The safety of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1541–1545. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.122.

42. Sahambi SK, Hales BF. Exposure to 5-bromo-2 deoxyuridine induces oxidative stress and activator protein–1 DNA binding activity in the embryo. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006; 76(8):580–591. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20284.

Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006; 76(8):580–591. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20284.

43. Wellfelt K, Skold AC, Wallin A, et al. Teratogenicity of the class III antiarrhythmic drug almokalant. Role of hypoxia and reactive oxygen species. Reprod Toxicol. 1999;13(2):93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(98)00066-5.

44. Hansen JM, Harris C. A novel hypothesis for thalidomideinduced limb teratogenesis: redox misregulation of the NF-kB pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6(1):1–14. doi: 10.1089/152308604771978291.

45. Winn LM, Wells PG. Maternal administration of superoxide dismutase and catalase in phenytoin teratogenicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(3–4):266–274. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00193-2.

46. Defoort EN, Kim PM, Winn LM. Valproic acid increases conservative homologous recombination frequency and reactive oxygen species formation: a potential mechanism for valproic acid-induced neural tube defects. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69(4): 1304–1310. doi: 10.1124/mol. 105.017855.

105.017855.

47. Scholl TO. Iron status during pregnancy: setting the stage for mother and infant. Am J Clinic Nutr. 2005;81(5):1218–1222.

48. Foster W, Myllynen P, Winn LM, et al. Reactive oxygen species, diabetes and toxicity in the placenta: a workshop report. Placenta. 2008;29:105–107. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.10.014.

49. Azzato EM, Chen RA, Wacholder S, et al. Maternal EPHX1 polymorphisms and risk of phenytoin-induced congenital malformations. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20(1):58–63. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328334b6a3.

50. Chevrier C, Bahuau M, Perret C, et al. Genetic susceptibilities in the association between maternal exposure to tobacco smoke and the risk of nonsyndromic oral cleft. Am J Med Genet A. 2008; 146A(18):2396–2406. doi:10.1002/ajmg. a.32505.

51. Shi M, Christensen K, Weinberg CR, et al. Orofacial cleft risk is increased with maternal smoking and specific detoxification gene variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(1):76–90. doi: 10. 1086/510518.

1086/510518.

52. van Rooij I, Wegerif MJ, Roelofs HM, et al. Smoking, genetic polymorphisms in biotransformation enzymes, and nonsyndromic oral clefting: a gene-environment interaction. Epidemiology. 2001;12(5):502–507. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00007.

53. Hartsfield JK Jr, Hickman TA, Everett ET, et al. Analysis of the EPHX1 113 polymorphism and GSTM1 homozygous null polymorphism and oral clefting associated with maternal smoking. Am J Med Genet. 2001;102(1):21–24. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010722)102:1<21::aid-ajmg1409>3.0.co;2-t.

54. Lie RT, Wilcox AJ, Taylor J, et al. Maternal smoking and oral clefts: the role of detoxification pathway genes. Epidemiology.2008;19(4):606–615. doi: 10.1097/ede.0b013e3181690731.

55. Orioli IM, Castilla EE. Epidemiological assessment of misoprostol teratogenicity. BJOG. 2000;107(4):519–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13272.x.

56. Vargas FR, Schuler-Faccini L, Brunoni D, et al. Prenatal exposure to misoprostol and vascular disruption defects: a case-control study. Am J Med Genet. 2000;95(4):302–306. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001211)95:4<302: aid-ajmg2>3.0.co;2-b.

Am J Med Genet. 2000;95(4):302–306. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001211)95:4<302: aid-ajmg2>3.0.co;2-b.

57. Kozer E, Nikfar S, Costei A, et al. Aspirin consumption during the first trimester of pregnancy and congenital anomalies: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(6):1623–1630. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127376.

58. Werler MM, Mitchell AA, Shapiro S. The relation of aspirin use during the first trimester of pregnancy to congenital cardiac defects. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(24):1639–1642. doi:10.1056/name198912143212404.

59. Raymond GV. Teratogen update: ergot and ergotamine. Teratology. 1995;51(5):344–347. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420510511.

60. Smets K, Zecic A, Willems J. Ergotamine as a possible cause of Mobius sequence: additional clinical observation. J Child Neurol. 2004;19(5):398. doi: 10.1177/08830738040 1

8. 61. Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Hayes C, et al. Vaso exposureactives, vascular events, and hemifacial microsomia. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70(6):389–395. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20022.

2004;70(6):389–395. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20022.

62. Schutz S, Le Moullec JM, Corvol P, Gasc JM. Early expression of all the components of the renin-angiotensin-system in human development. Am J Pathol. 1996;149(6):2067–2079.

63. Himmelmann A, Hansson L, Hansson BG, et al. ACE inhibition preserves renal function better than beta-blockade in the treatment of essential hypertension. Blood Press. 1995;4(2):85–90. doi: 10.3109/08037059509077575.

64. Shotan A, Widerhorn J, Hurst A, et al. Risks of angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibition during pregnancy: experimental and clinical evidence, potential mechanisms, and recommendations for use. Am J Med. 1994;96(5):451–456. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)

-4.

65. Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG, et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2443–2451. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa055202.

66. Alwan S, Polifka JE, Friedman JM. Angiotensin II receptor antagonist treatment during pregnancy. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73(2):123–130. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20102.

Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73(2):123–130. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20102.

67. Gofflot F, Hars C, Illien F, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying limb anomalies associated with cholesterol deficiency during gestation: implications of Hedgehog signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(10):1187–1198. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg129.

68. Petersen EE, Mitchell AA, Carey JC, et al. Maternal exposure to statins and risk for birth defects: a case-series approach. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(20):2701–2705. doi:10.1002/ajmg. a.32493.

69. Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Fischer MA, et al. Statins and congenital malformations: a cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2035. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2035.