Most common congenital abnormality

Birth defects

Birth defects- All topics »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Resources »

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Multimedia

- Publications

- Questions & answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Popular »

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Monkeypox

- All countries »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Regions »

- Africa

- Americas

- South-East Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- WHO in countries »

- Statistics

- Cooperation strategies

- Ukraine emergency

- All news »

- News releases

- Statements

- Campaigns

- Commentaries

- Events

- Feature stories

- Speeches

- Spotlights

- Newsletters

- Photo library

- Media distribution list

- Headlines »

- Focus on »

- Afghanistan crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Northern Ethiopia crisis

- Syria crisis

- Ukraine emergency

- Monkeypox outbreak

- Greater Horn of Africa crisis

- Latest »

- Disease Outbreak News

- Travel advice

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- WHO in emergencies »

- Surveillance

- Research

- Funding

- Partners

- Operations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- WHO's Health Emergency Appeal 2023

- Data at WHO »

- Global Health Estimates

- Health SDGs

- Mortality Database

- Data collections

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Dashboard

- Triple Billion Dashboard

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Highlights »

- Global Health Observatory

- SCORE

- Insights and visualizations

- Data collection tools

- Reports »

- World Health Statistics 2022

- COVID excess deaths

- DDI IN FOCUS: 2022

- About WHO »

- People

- Teams

- Structure

- Partnerships and collaboration

- Collaborating centres

- Networks, committees and advisory groups

- Transformation

- Our Work »

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Activities

- Initiatives

- Funding »

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- Accountability »

- Audit

- Programme Budget

- Financial statements

- Programme Budget Portal

- Results Report

- Governance »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Election of Director-General

- Governing Bodies website

- Member States Portal

- Home/

- Newsroom/

- Fact sheets/

- Detail/

- Birth defects

Causes and risk factors

Genetic

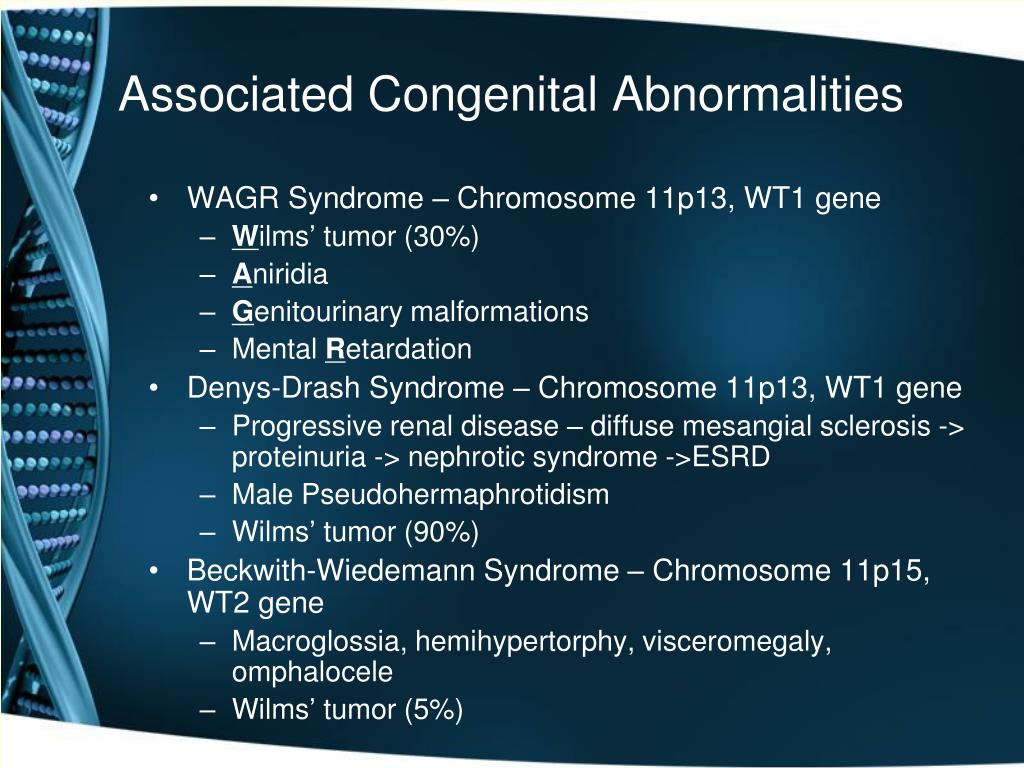

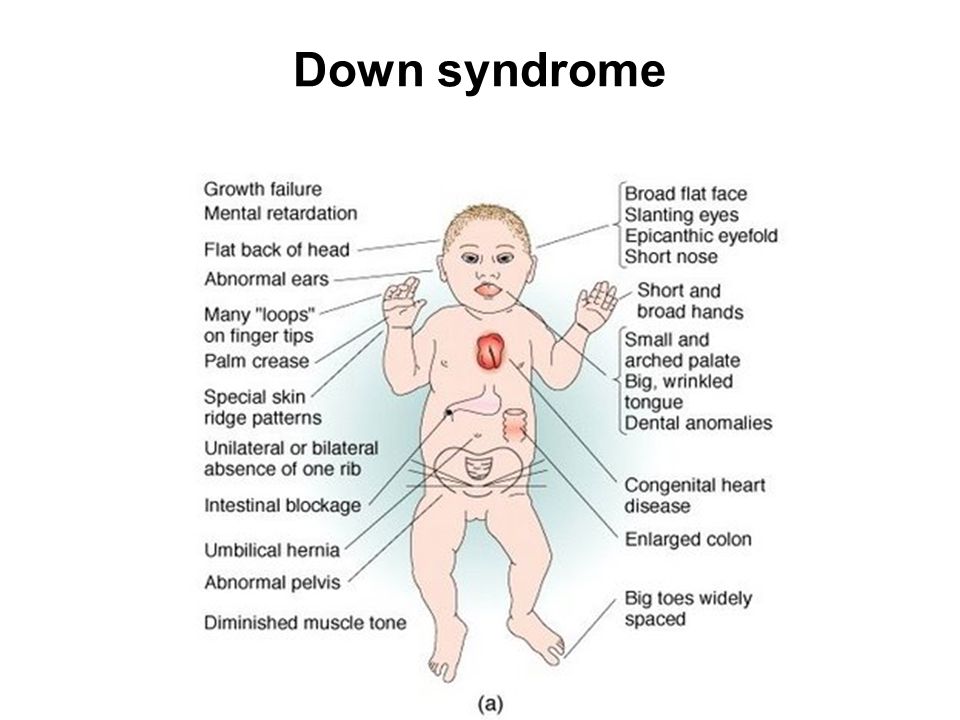

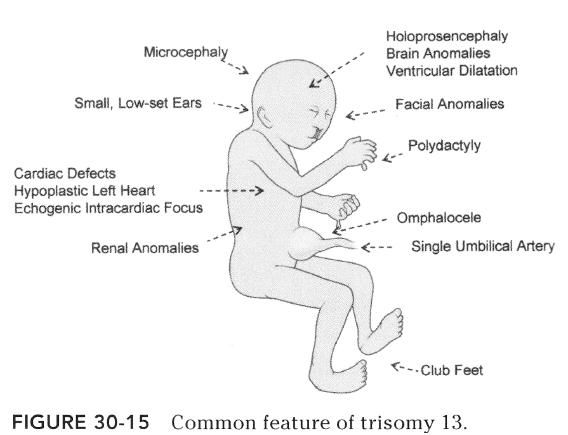

A minority of birth defects are caused by genetic abnormalities i. e. chromosomal abnormalities (for example Down syndrome or trisomy 21) or single gene defects (for example cystic fibrosis).

Consanguinity (when parents are related by blood) also increases the prevalence of rare genetic birth defects and nearly doubles the risk for neonatal and childhood death, intellectual disability and other anomalies.

Socioeconomic and demographic factors

Low-income may be an indirect determinant of birth defects, with a higher frequency among resource-constrained families and countries. It is estimated that about 94% of severe birth defects occur in low- and middle-income countries. An indirect determinant,\r\n this higher risk relates to a possible lack of access to sufficient nutritious foods by pregnant women, an increased exposure to agents or factors such as infection and alcohol, or poorer access to health care and screening.

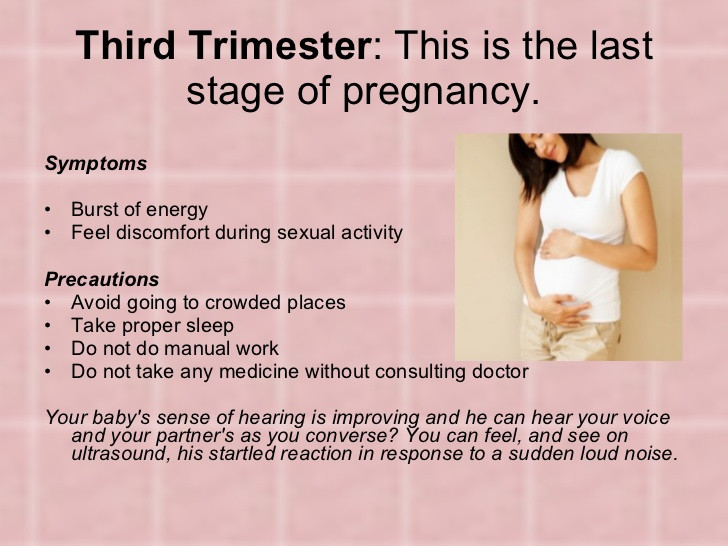

Maternal age is also a risk factor for abnormal intrauterine fetal development. Advanced maternal age increases the risk of chromosomal abnormalities, including Down syndrome.

Environmental factors including infections

Others occur because of environmental factors like maternal infections (syphilis, rubella, Zika), exposure to radiation, certain pollutants, maternal nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iodine, folate deficiency), illness (maternal diabetes) or certain drugs\r\n (alcohol, phenytoin).

Unknown causes

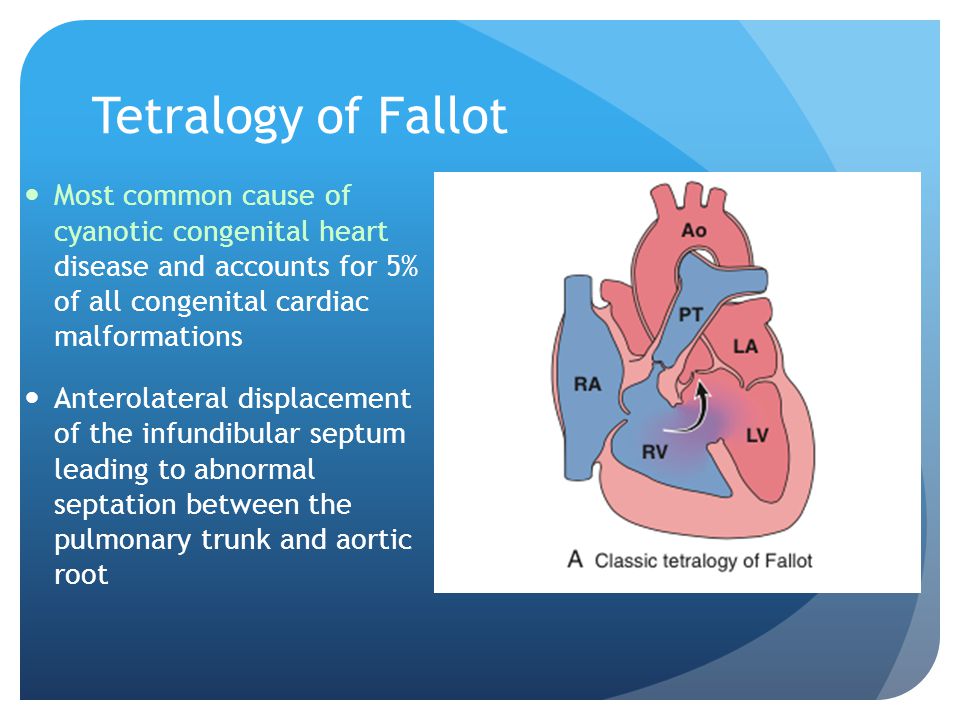

While complex genetic and environmental interactions are proposed, most birth defects have unknown causes, including congenital heart defects, cleft lip or palate and club foot.

Prevention

Preventive public health measures work to decrease the frequency of certain birth defects through the removal of risk factors or the reinforcement of protective factors. Important interventions and efforts include:

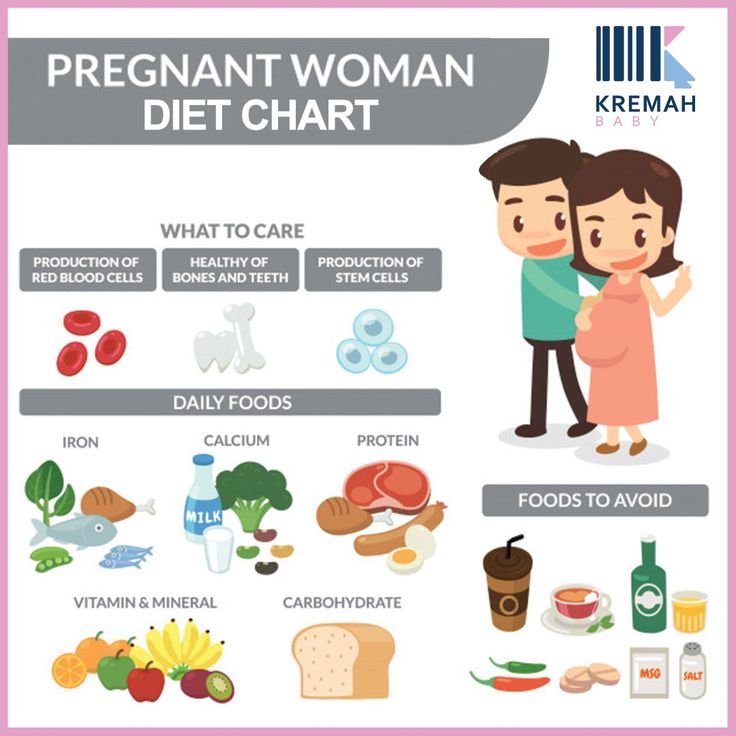

- ensuring adolescent girls and mothers have a healthy diet including a wide variety of vegetables and fruit, and maintain a healthy weight;

- ensuring an adequate dietary intake of vitamins and minerals, particularly folic acid in adolescent girls and mothers;

- ensuring mothers avoid harmful substances, particularly alcohol and tobacco;

- avoidance of travel by pregnant women (and sometimes women of child-bearing age) to regions experiencing outbreaks of infections known to be associated with birth defects;

- reducing or eliminating environmental exposure to hazardous substances (such as heavy metals or pesticides) during pregnancy;

- controlling diabetes prior to and during pregnancy through counselling, weight management, diet and administration of insulin when required;

- ensuring that any exposure of pregnant women to medications or medical radiation (such as imaging rays) is justified and based on careful health risk–benefit analysis;

- vaccination, especially against the rubella virus, for children and women;

- increasing and strengthening education of health staff and others involved in promoting prevention of congenital anomalies; and

- screening for infections, especially rubella, varicella and syphilis, and consideration of treatment.

Screening, treatment and care

Screening

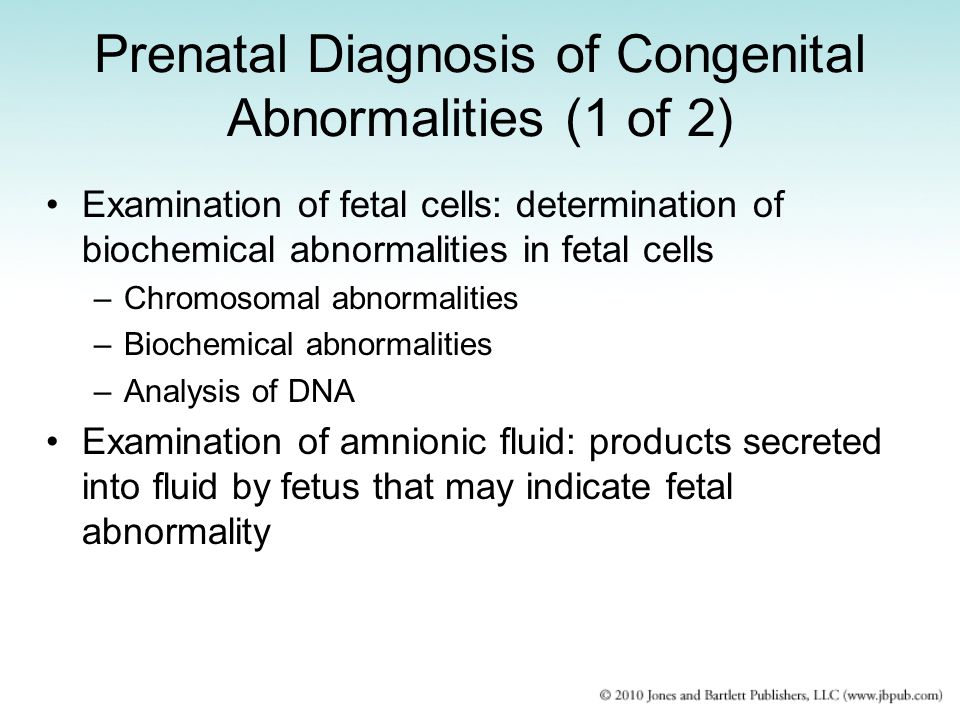

Health care before and near conception (preconception and peri-conception) includes basic reproductive health practices, as well as medical genetic screening and counselling. Screening can be conducted during the 3 periods listed:

- Preconception screening:

This can be useful to identify those at risk of specific disorders or of passing a disorder onto their children. Screening includes obtaining family histories and carrier screening and is particularly valuable in countries where consanguineous marriage\r\n is common.

- Peri-conception screening:

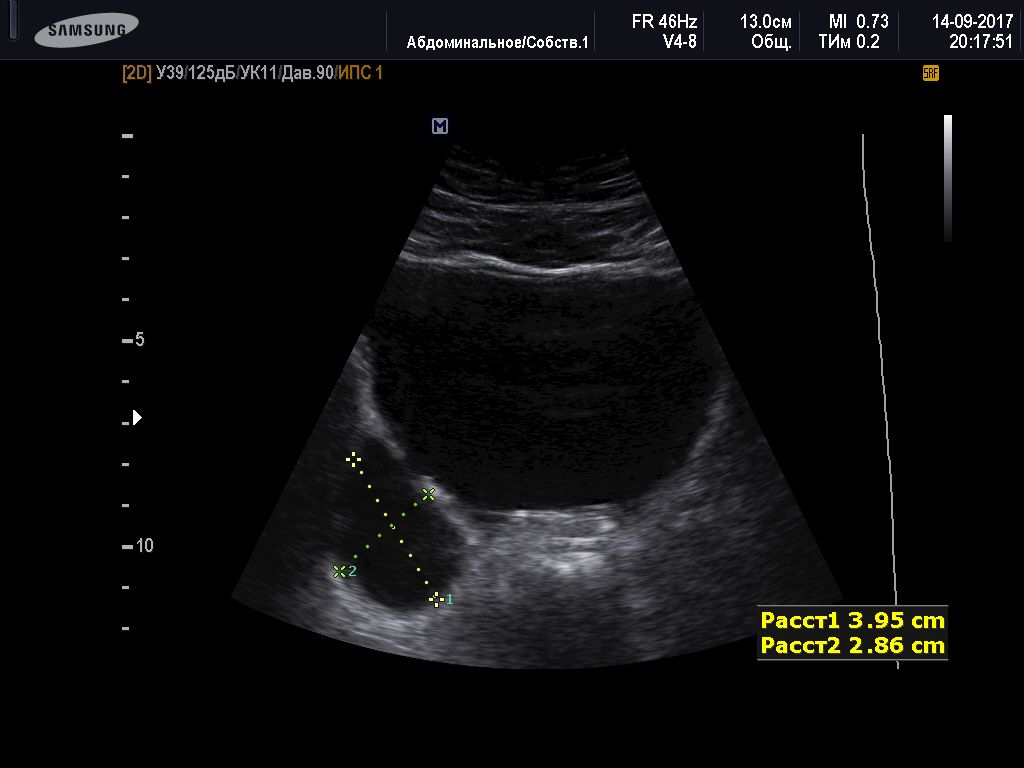

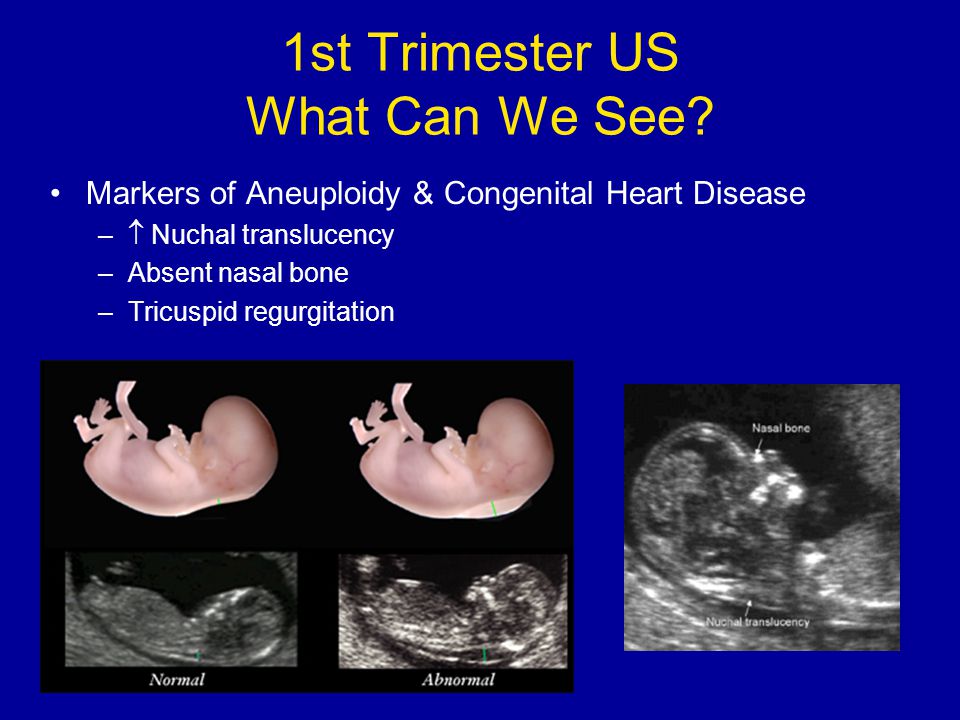

Maternal characteristics may increase risk, and screening results should be used to offer appropriate care, according to risk. This may include screening for young or advanced maternal age, as well as screening for use of alcohol, tobacco or other risks.\r\n Ultrasound can be used to screen for Down syndrome and major structural abnormalities during the first trimester, and for severe fetal anomalies during the second trimester. Maternal blood can be screened for placental markers to aid in prediction\r\n of risk of chromosomal abnormalities or neural tube defects, or for free fetal DNA to screen for many chromosomal abnormalities. Diagnostic tests such as chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis can be used to diagnose chromosomal abnormalities\r\n and infections in women at high risk.

Maternal blood can be screened for placental markers to aid in prediction\r\n of risk of chromosomal abnormalities or neural tube defects, or for free fetal DNA to screen for many chromosomal abnormalities. Diagnostic tests such as chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis can be used to diagnose chromosomal abnormalities\r\n and infections in women at high risk.

- Neonatal screening:

Screening of newborns is an important step towards detection. This helps to reduce mortality and morbidity from birth defects by facilitating earlier referral and the initiation of medial or surgical treatment.

Early screening for hearing loss provides an opportunity for early correction and allows the possibility of acquiring better language, speech and communication skills. Early screening of newborns for congenital cataract also allows early referral and\r\n surgical correction which increases the likelihood of sight.

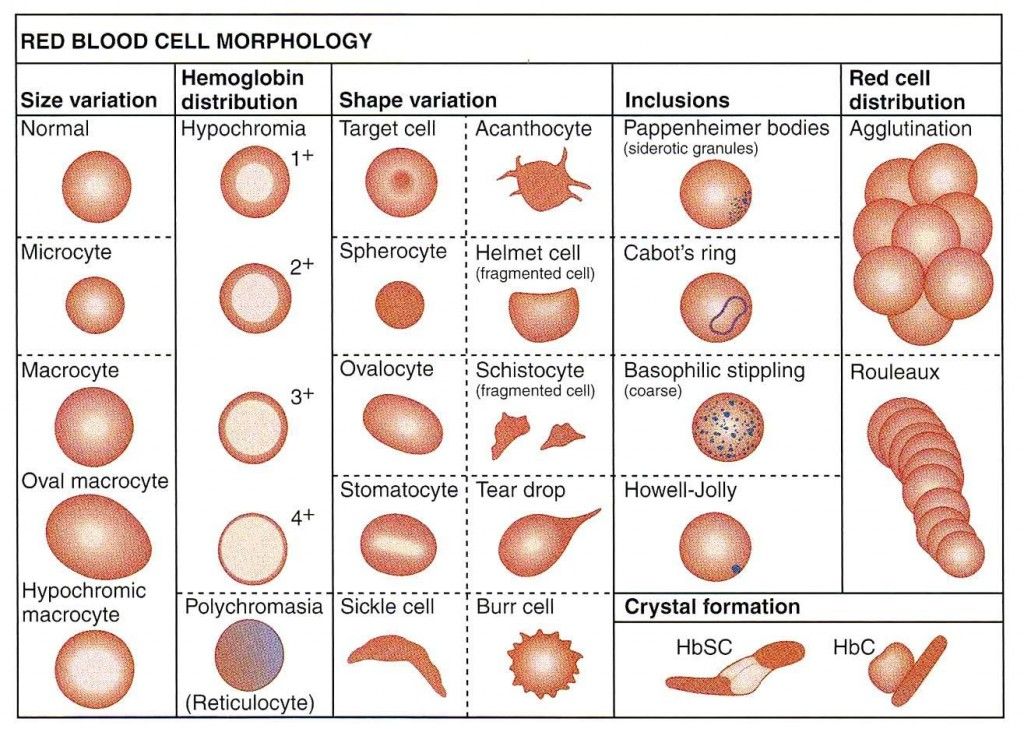

Newborns may be screened for certain metabolic, hematologic and endocrine disorders, many of which may not have immediately visible effects. The conditions screened for vary by country, depending on prevalence and cost. Newborn screening is increasingly\r\n conducted even in low- and middle-income countries.

Treatment and care

Some birth defects can be treated with medical or surgical interventions. Access to this care may vary by country and by different levels of a health system, though complex care is increasingly available in low- and middle-income settings.

Surgery with good follow up care can often mitigate the potential lethality (as in the case of congenital heart defects) or the morbidity (e.g., congenital talipes, cleft lip/palate) associated with structural birth defects. The contribution to reducing\r\n mortality and morbidity of this aspect of the treatment is often underestimated. Outcomes are improved with early detection at lower levels of the system through screening, referral and management (at specialist centres in case of some issues like\r\n cardiac defects).

Medical treatment for certain metabolic, endocrine and hematological conditions can improve quality of life. A clear example is congenital hypothyroidism, where early detection and treatment allows full physical and mental development to healthy adulthood,\r\n whereas a missed diagnosis or unavailability of a simple treatment carries a risk of serious intellectual disability.

Children with some types of birth defects may require long term support including physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy and support from families and community.

WHO response

Through the resolution on birth defects of the Sixty-third World Health Assembly (2010), Member States agreed to promote primary prevention and improve the health of children with congenital anomalies by:

- developing and strengthening registration and surveillance systems;

- developing expertise and building capacity for the prevention of birth defects and care of children affected;

- raising awareness on the importance of newborn screening programmes and their role in identifying infants born with congenital birth defects;

- supporting families who have children with birth defects and associated disabilities; and

- strengthening research on major birth defects and promoting international cooperation in combatting them.

Together with partners, WHO convenes annual training programmes on the surveillance and prevention of birth defects. WHO is also working with partners to provide the required technical expertise for the surveillance of neural tube defects, for monitoring\r\n fortification of staple foods with folic acid, and for improving laboratory capacity for assessing risks for folic acid-preventable birth defects and is assisting low- and middle-income countries in improving control and elimination of rubella and\r\n congenital rubella syndrome through immunization.

WHO develops normative tools, including guidelines and a global plan of action, to strengthen medical care and rehabilitation services to support the implementation of the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities.\r\n \r\n

","datePublished":"2022-02-28T22:52:00.0000000+00:00","image":"https://cdn.who.int/media/images/default-source/imported/preterm-birth-mother-jpg. jpg?sfvrsn=c5c1adf1_0","publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"World Health Organization: WHO","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.who.int/Images/SchemaOrg/schemaOrgLogo.jpg","width":250,"height":60}},"dateModified":"2022-02-28T22:52:00.0000000+00:00","mainEntityOfPage":"https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/birth-defects","@context":"http://schema.org","@type":"Article"};

jpg?sfvrsn=c5c1adf1_0","publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"World Health Organization: WHO","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.who.int/Images/SchemaOrg/schemaOrgLogo.jpg","width":250,"height":60}},"dateModified":"2022-02-28T22:52:00.0000000+00:00","mainEntityOfPage":"https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/birth-defects","@context":"http://schema.org","@type":"Article"};

Key facts

- An estimated 240 000 newborns die worldwide within 28 days of birth every year due to birth defects. Birth defects cause a further 170 000 deaths of children between the ages of 1 month and 5 years.

- Birth defects can contribute to long-term disability, which takes a significant toll on individuals, families, health care systems and societies.

- Nine of ten children born with a serious birth defect are in low- and middle-income countries.

- As neonatal and under-5 mortality rates decline, birth defects become a larger proportion of the cause of neonatal and under-5 deaths.

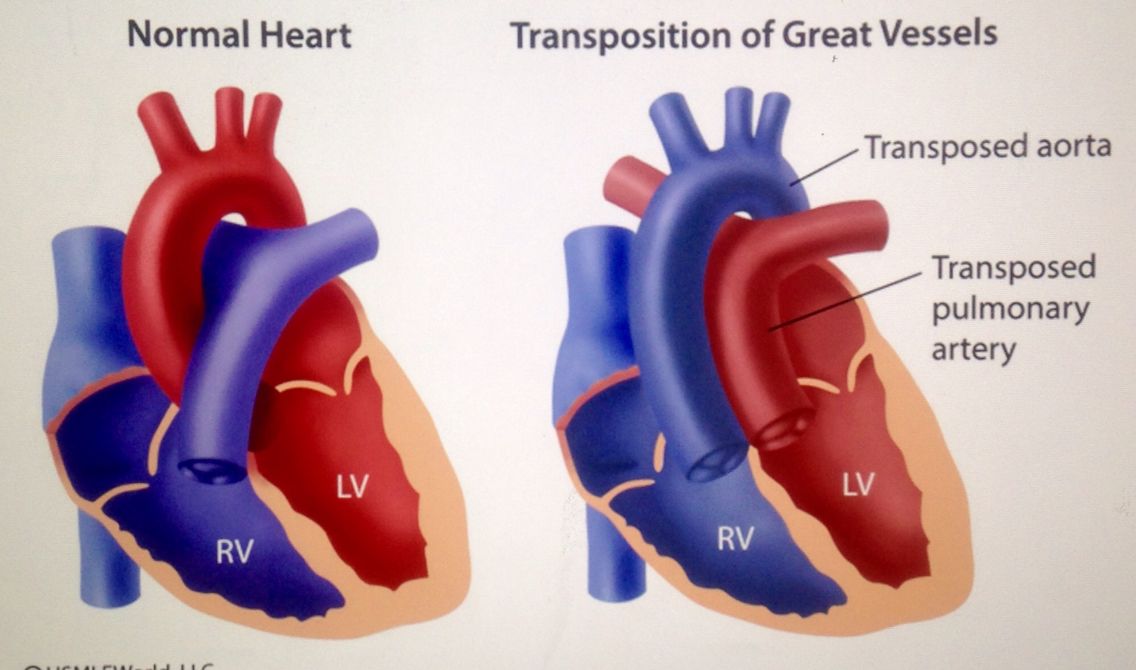

- The most common severe birth defects are heart defects, neural tube defects and Down syndrome.

- Although birth defects may be the result of one or more genetic, infectious, nutritional or environmental factors, it is often difficult to identify the exact causes.

- Some birth defects can be prevented. Vaccination, adequate intake of folic acid or iodine through fortification of staple foods or supplementation, and adequate care before and during a pregnancy are examples of prevention methods.

Birth defects are also known as congenital abnormalities, congenital disorders or congenital malformations. They can be defined as structural or functional anomalies (for example, metabolic disorders) that occur during intrauterine life and can be identified prenatally, at birth, or sometimes may only be detected later in infancy, such as hearing defects. Broadly, congenital refers to the existence at or before birth.

The proportion of under-5 deaths due to birth defects increases as other causes of under-5 deaths are controlled (fig. 1).

1).

Fig 1: Changes in causes of under 5 deaths as under 5 mortality rates decline

Causes and risk factors

Genetic

A minority of birth defects are caused by genetic abnormalities i.e. chromosomal abnormalities (for example Down syndrome or trisomy 21) or single gene defects (for example cystic fibrosis).

Consanguinity (when parents are related by blood) also increases the prevalence of rare genetic birth defects and nearly doubles the risk for neonatal and childhood death, intellectual disability and other anomalies.

Socioeconomic and demographic factors

Low-income may be an indirect determinant of birth defects, with a higher frequency among resource-constrained families and countries. It is estimated that about 94% of severe birth defects occur in low- and middle-income countries. An indirect determinant, this higher risk relates to a possible lack of access to sufficient nutritious foods by pregnant women, an increased exposure to agents or factors such as infection and alcohol, or poorer access to health care and screening.

Maternal age is also a risk factor for abnormal intrauterine fetal development. Advanced maternal age increases the risk of chromosomal abnormalities, including Down syndrome.

Environmental factors including infections

Others occur because of environmental factors like maternal infections (syphilis, rubella, Zika), exposure to radiation, certain pollutants, maternal nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iodine, folate deficiency), illness (maternal diabetes) or certain drugs (alcohol, phenytoin).

Unknown causes

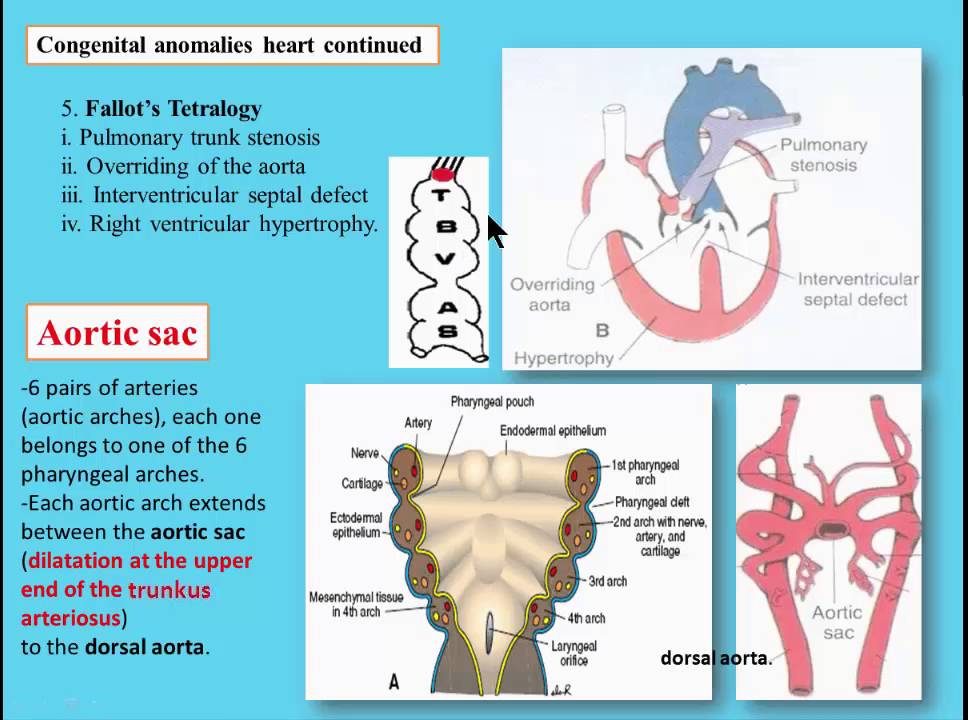

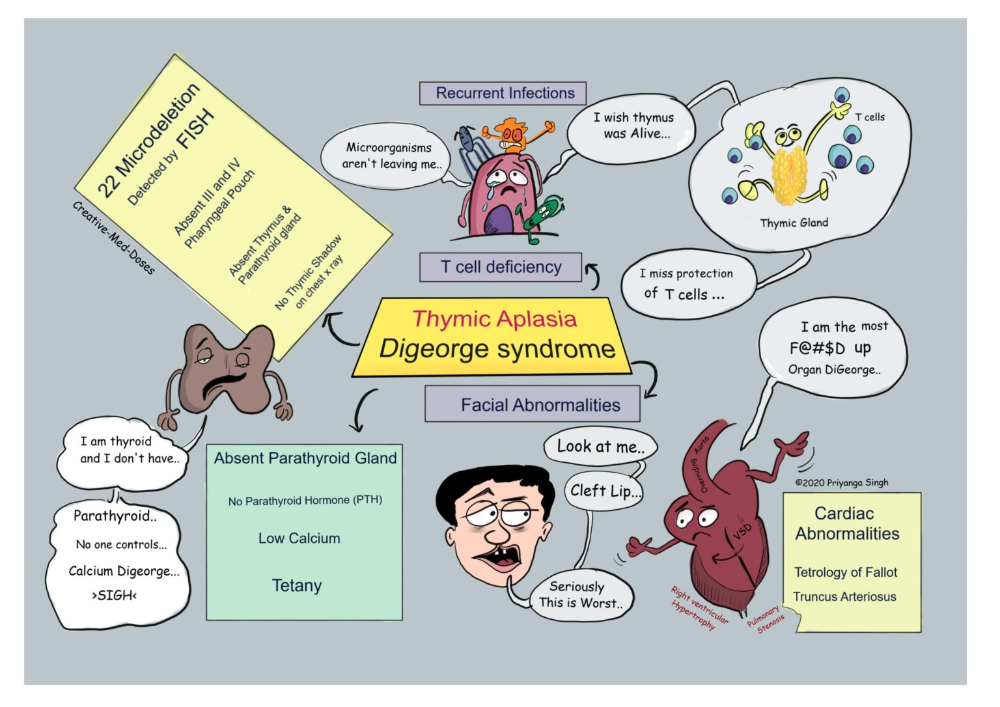

While complex genetic and environmental interactions are proposed, most birth defects have unknown causes, including congenital heart defects, cleft lip or palate and club foot.

Prevention

Preventive public health measures work to decrease the frequency of certain birth defects through the removal of risk factors or the reinforcement of protective factors. Important interventions and efforts include:

- ensuring adolescent girls and mothers have a healthy diet including a wide variety of vegetables and fruit, and maintain a healthy weight;

- ensuring an adequate dietary intake of vitamins and minerals, particularly folic acid in adolescent girls and mothers;

- ensuring mothers avoid harmful substances, particularly alcohol and tobacco;

- avoidance of travel by pregnant women (and sometimes women of child-bearing age) to regions experiencing outbreaks of infections known to be associated with birth defects;

- reducing or eliminating environmental exposure to hazardous substances (such as heavy metals or pesticides) during pregnancy;

- controlling diabetes prior to and during pregnancy through counselling, weight management, diet and administration of insulin when required;

- ensuring that any exposure of pregnant women to medications or medical radiation (such as imaging rays) is justified and based on careful health risk–benefit analysis;

- vaccination, especially against the rubella virus, for children and women;

- increasing and strengthening education of health staff and others involved in promoting prevention of congenital anomalies; and

- screening for infections, especially rubella, varicella and syphilis, and consideration of treatment.

Screening, treatment and care

Screening

Health care before and near conception (preconception and peri-conception) includes basic reproductive health practices, as well as medical genetic screening and counselling. Screening can be conducted during the 3 periods listed:

- Preconception screening:

This can be useful to identify those at risk of specific disorders or of passing a disorder onto their children. Screening includes obtaining family histories and carrier screening and is particularly valuable in countries where consanguineous marriage is common.

- Peri-conception screening:

Maternal characteristics may increase risk, and screening results should be used to offer appropriate care, according to risk. This may include screening for young or advanced maternal age, as well as screening for use of alcohol, tobacco or other risks. Ultrasound can be used to screen for Down syndrome and major structural abnormalities during the first trimester, and for severe fetal anomalies during the second trimester. Maternal blood can be screened for placental markers to aid in prediction of risk of chromosomal abnormalities or neural tube defects, or for free fetal DNA to screen for many chromosomal abnormalities. Diagnostic tests such as chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis can be used to diagnose chromosomal abnormalities and infections in women at high risk.

Maternal blood can be screened for placental markers to aid in prediction of risk of chromosomal abnormalities or neural tube defects, or for free fetal DNA to screen for many chromosomal abnormalities. Diagnostic tests such as chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis can be used to diagnose chromosomal abnormalities and infections in women at high risk.

- Neonatal screening:

Screening of newborns is an important step towards detection. This helps to reduce mortality and morbidity from birth defects by facilitating earlier referral and the initiation of medial or surgical treatment.

Early screening for hearing loss provides an opportunity for early correction and allows the possibility of acquiring better language, speech and communication skills. Early screening of newborns for congenital cataract also allows early referral and surgical correction which increases the likelihood of sight.

Newborns may be screened for certain metabolic, hematologic and endocrine disorders, many of which may not have immediately visible effects. The conditions screened for vary by country, depending on prevalence and cost. Newborn screening is increasingly conducted even in low- and middle-income countries.

The conditions screened for vary by country, depending on prevalence and cost. Newborn screening is increasingly conducted even in low- and middle-income countries.

Treatment and care

Some birth defects can be treated with medical or surgical interventions. Access to this care may vary by country and by different levels of a health system, though complex care is increasingly available in low- and middle-income settings.

Surgery with good follow up care can often mitigate the potential lethality (as in the case of congenital heart defects) or the morbidity (e.g., congenital talipes, cleft lip/palate) associated with structural birth defects. The contribution to reducing mortality and morbidity of this aspect of the treatment is often underestimated. Outcomes are improved with early detection at lower levels of the system through screening, referral and management (at specialist centres in case of some issues like cardiac defects).

Medical treatment for certain metabolic, endocrine and hematological conditions can improve quality of life. A clear example is congenital hypothyroidism, where early detection and treatment allows full physical and mental development to healthy adulthood, whereas a missed diagnosis or unavailability of a simple treatment carries a risk of serious intellectual disability.

A clear example is congenital hypothyroidism, where early detection and treatment allows full physical and mental development to healthy adulthood, whereas a missed diagnosis or unavailability of a simple treatment carries a risk of serious intellectual disability.

Children with some types of birth defects may require long term support including physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy and support from families and community.

WHO response

Through the resolution on birth defects of the Sixty-third World Health Assembly (2010), Member States agreed to promote primary prevention and improve the health of children with congenital anomalies by:

- developing and strengthening registration and surveillance systems;

- developing expertise and building capacity for the prevention of birth defects and care of children affected;

- raising awareness on the importance of newborn screening programmes and their role in identifying infants born with congenital birth defects;

- supporting families who have children with birth defects and associated disabilities; and

- strengthening research on major birth defects and promoting international cooperation in combatting them.

Together with partners, WHO convenes annual training programmes on the surveillance and prevention of birth defects. WHO is also working with partners to provide the required technical expertise for the surveillance of neural tube defects, for monitoring fortification of staple foods with folic acid, and for improving laboratory capacity for assessing risks for folic acid-preventable birth defects and is assisting low- and middle-income countries in improving control and elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome through immunization.

WHO develops normative tools, including guidelines and a global plan of action, to strengthen medical care and rehabilitation services to support the implementation of the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities.

1.4 Congenital Anomalies - Definitions

- Chapter 1: Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 The Purpose of Congenital Anomalies Surveillance

- 1.

3 Types of Surveillance Programmes

3 Types of Surveillance Programmes - 1.4 Congenital Anomalies - Definitions

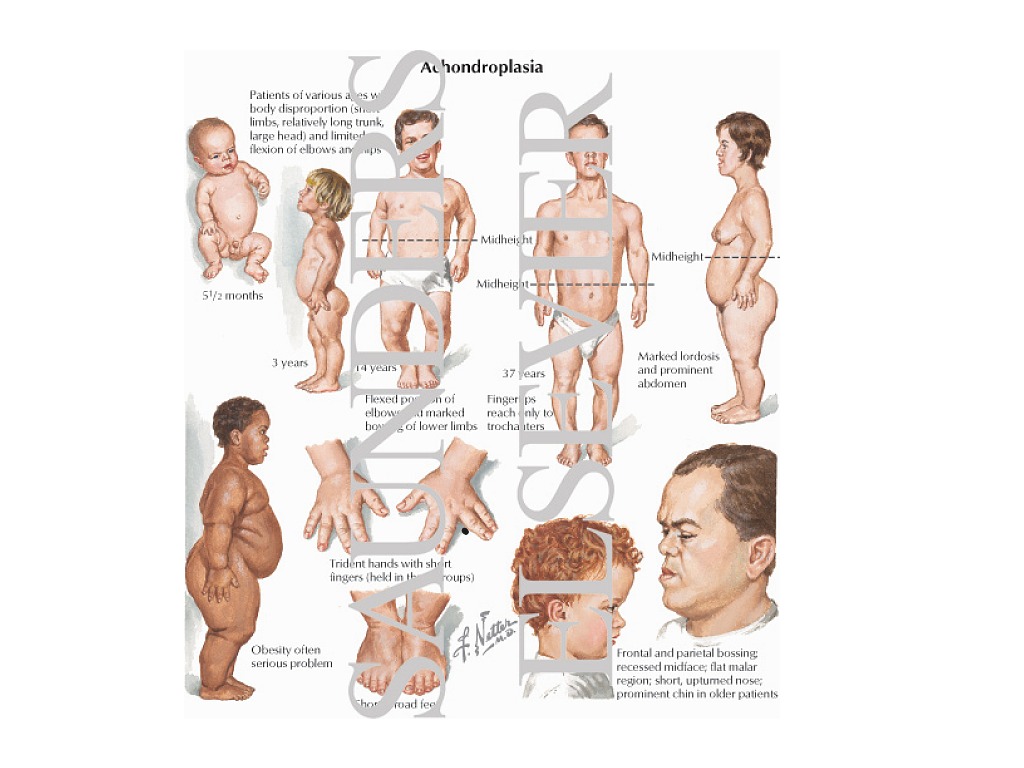

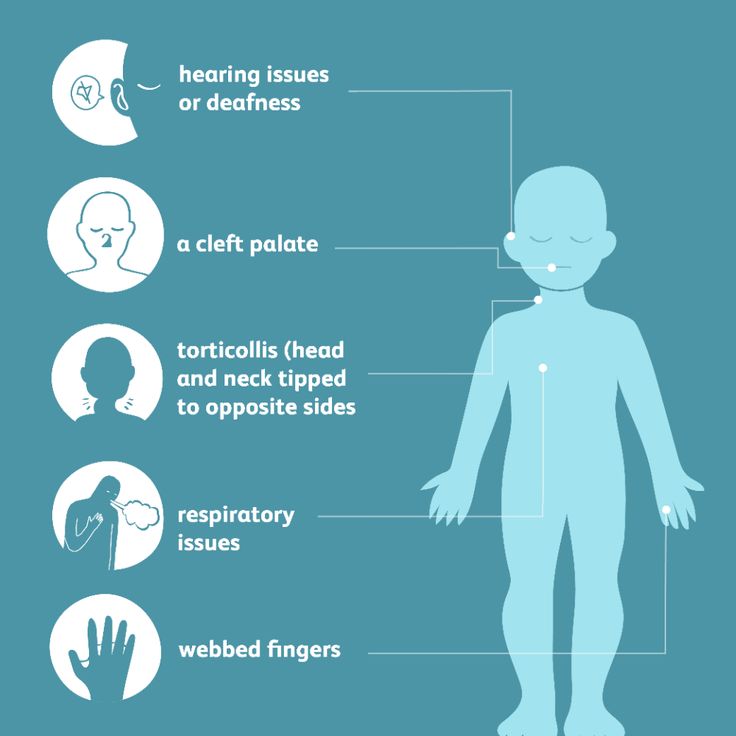

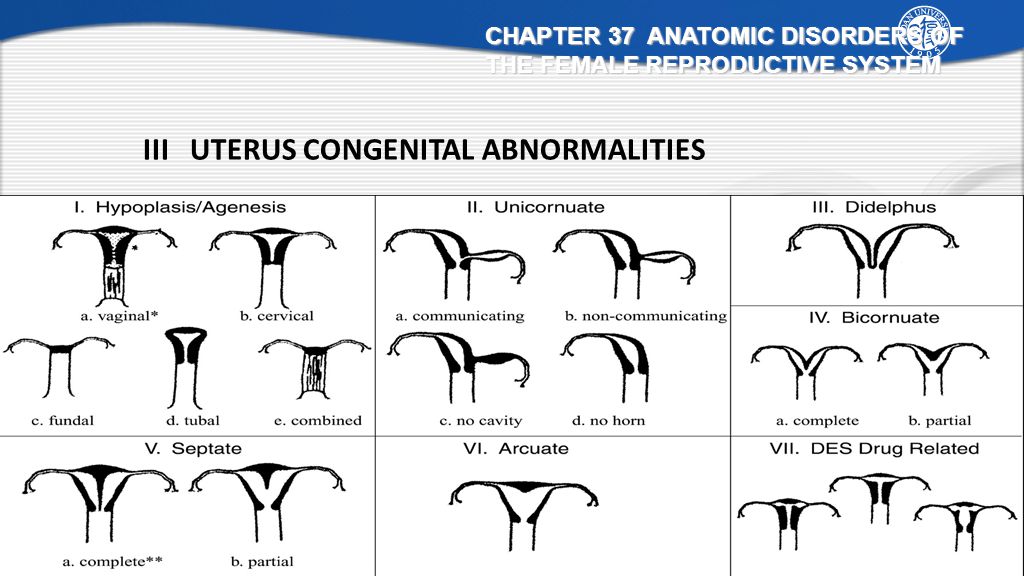

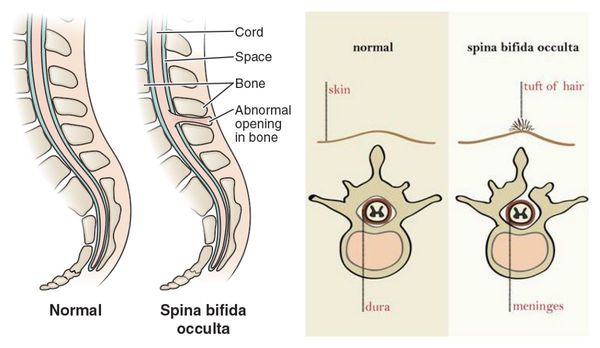

Congenital anomalies comprise a wide range of abnormalities of body structure or function that are present at birth and are of prenatal origin. For efficiency and practicality, the focus is commonly on major structural anomalies. These are defined as structural changes that have significant medical, social or cosmetic consequences for the affected individual, and typically require medical intervention. Examples include cleft lip and spina bifida.

Major structural anomalies are the conditions that account for most of the deaths, morbidity and disability related to congenital anomalies (see Box 1.1 for a list of selected external and internal major congenital anomalies). In contrast, minor congenital anomalies, although more prevalent among the population, are structural changes that pose no significant health problem in the neonatal period and tend to have limited social or cosmetic consequences for the affected individual. Examples include single palmar crease and clinodactyly.

Examples include single palmar crease and clinodactyly.

| External | Internal |

|

|

| Chromosomal | |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | |

Major anomalies are sometimes associated with minor anomalies, which might be objective (e. g. preauricular tags) or more subjective (e.g. low-set ears). Box 1.2 represents selected external minor congenital anomalies frequently captured by different surveillance systems, but only when associated with any of the major anomalies under surveillance. For a more detailed listing of minor anomalies, please refer to Appendix B. Often, surveillance systems will collect information on specific syndromes that are multiple anomalies pathogenetically related due to a single cause – for example, genetic or environmental causes that are known to cause birth defects. Certain syndromes caused by infectious diseases are of special interest in many low- and middle-income countries . For a detailed listing of selected syndromes of infectious origin that are of public health significance, please refer to Appendix B.

g. preauricular tags) or more subjective (e.g. low-set ears). Box 1.2 represents selected external minor congenital anomalies frequently captured by different surveillance systems, but only when associated with any of the major anomalies under surveillance. For a more detailed listing of minor anomalies, please refer to Appendix B. Often, surveillance systems will collect information on specific syndromes that are multiple anomalies pathogenetically related due to a single cause – for example, genetic or environmental causes that are known to cause birth defects. Certain syndromes caused by infectious diseases are of special interest in many low- and middle-income countries . For a detailed listing of selected syndromes of infectious origin that are of public health significance, please refer to Appendix B.

When establishing a new congenital anomalies surveillance programme, the initial anomalies that are included can be limited to structural anomalies that are readily identifiable and easily recognized on physical examination at birth or shortly after birth. The list may vary, depending on the capacity and resources of the health-care system and surveillance programme, but typically includes major external congenital anomalies. Examples include:

The list may vary, depending on the capacity and resources of the health-care system and surveillance programme, but typically includes major external congenital anomalies. Examples include:

- orofacial clefts,

- neural tube defects, and

- limb deficiencies.

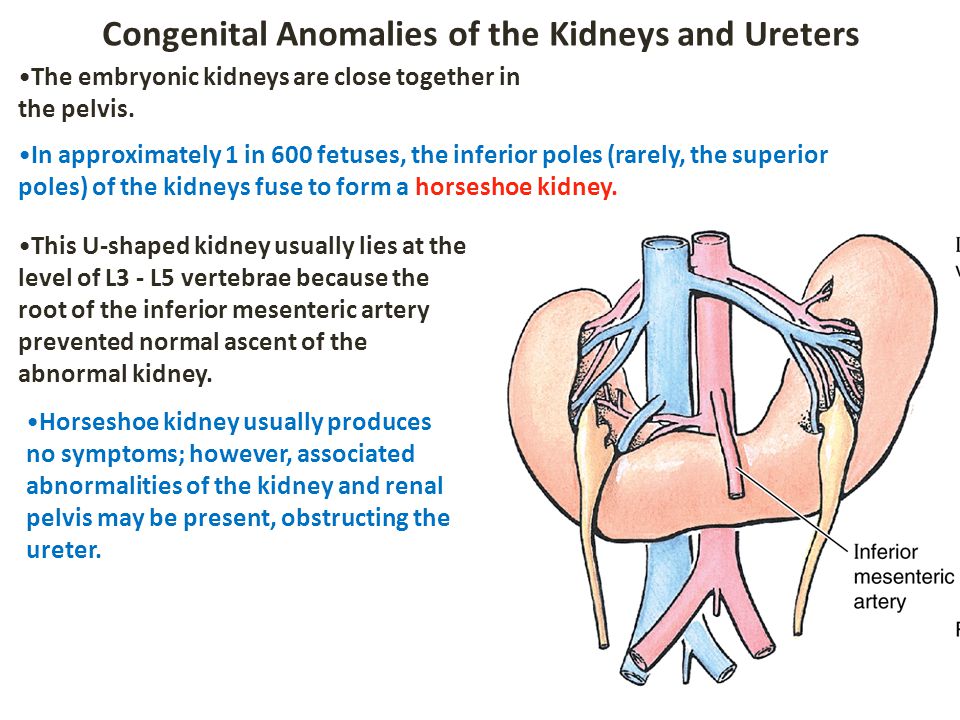

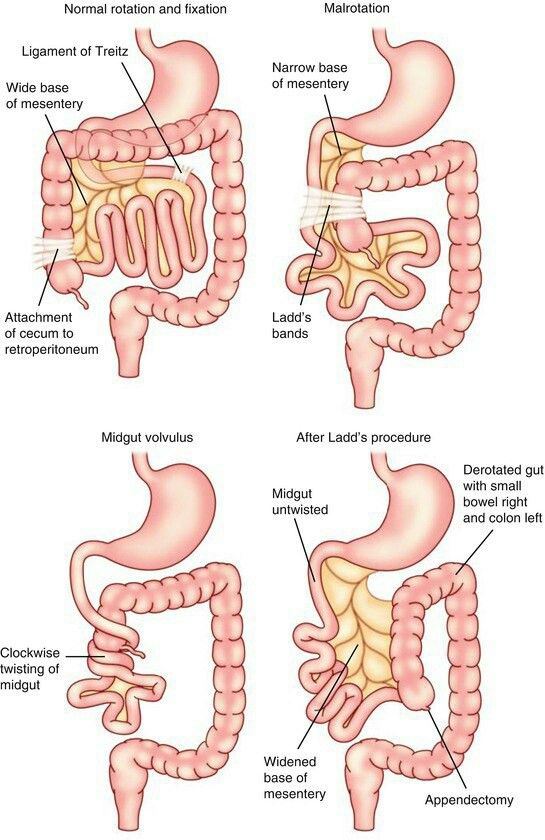

In contrast, detecting the vast majority of internal structural anomalies (e.g. congenital heart defects, intestinal malrotation and unilateral kidney agenesis) requires imaging techniques or other specialized procedures that may not be available consistently. In some cases, internal anomalies have external manifestations that allow the observer to suspect a particular diagnosis, as is the case with the urethral obstruction sequence. Similar to collecting information on internal defects, collecting information on syndromes often requires gathering data from multiple sources such as laboratory, imaging or genetic testing. Therefore, collecting surveillance data on internal defects and syndromes is typically not recommended when first starting a surveillance programme.

Classification by developmental mechanism or clinical presentation can be important in surveillance, because the same congenital anomaly can have different etiologies. Futhermore, the distinction may be important both clinically and in etiological studies. Please refer to Appendix C for more information about the causes of congenital anomalies and their classification according to developmental mechanism and clinical presentation.

| Box 1.2. Selected external minor congenital anomalies | |

|---|---|

| Absent nails Accessory tragus Anterior anus (ectopic anus) Auricular tag or pit Bifid uvula or cleft uvula Branchial tag or pit Camptodactyly Cup ear Cutis aplasia (if large, this is a major anomaly) Ear lobe crease Ear lobe notch Ear pit or tag Extra nipples (supernumerary nipples) Facial asymmetry Hydrocele Hypoplastic fingernails Hypoplastic toenails Iris coloboma | Lop ear Micrognathia Natal teeth Overlapping digits Plagiocephaly Polydactyly type B tag, involves hand and foot Preauricular appendage, tag or lobule Redundant neck folds Rocker-bottom feet Single crease, fifth finger Single transverse palmar crease Single umbilical artery Small penis (unless documented as micropenis) Syndactyly involving second and third toes Tongue-tie (ankyloglossia) Umbilical hernia Undescended testicle Webbed neck (pterygium colli) |

2. Planning Activities and Tools

Planning Activities and Tools

Malformations

Malformations- Healthcare issues »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- 9000 O

- M

- R

- S

- T

- Y

- F

- X

- C

- W 0005

- B

- S

- B

- E

- S

- I

- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find country »

- A

- B

- in

- g

- d

- E

- С

- and

- K

- m

- N 9000

- t

- in

- x

- h

- Sh

- 9000 WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Events

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO Data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Malformations

\n

- \n

- development and strengthening of registration and surveillance systems; \n

- experience and capacity building; \n

- strengthening research and scientific work in the field of etiology, diagnosis and prevention; \n

- strengthening international cooperation.

\n

\n

\n

Definition

\n

\nCongenital malformations are also referred to as congenital malformations, congenital disorders, or congenital deformities. Congenital malformations can be defined as structural or functional abnormalities (eg, metabolic disorders) that appear in utero and may be identified before birth, during birth, or later in life.

\n

Causes and risk factors

\n

\nApproximately 50% of all malformations cannot be attributed to any specific cause, but some causes or risk factors are known.

\n

Socio-economic factors

\n

\nAlthough low income may be an indirect determinant, malformations are more likely to occur in families and countries with insufficient resources. It is estimated that approximately 94% of severe malformations occur in middle- and low-income countries, where women often do not have access to sufficient and good enough food and may be exposed to some agent or factor, such as infection or alcohol, that provokes or enhances deviations from the norm in prenatal development. Moreover, motherhood in adulthood increases the risk of chromosomal abnormalities, including Down's syndrome, while motherhood at a young age increases the risk of certain congenital malformations.

Moreover, motherhood in adulthood increases the risk of chromosomal abnormalities, including Down's syndrome, while motherhood at a young age increases the risk of certain congenital malformations.

\n

Genetic factors

\n

\nIncest (consanguinity) increases the prevalence of rare genetic birth defects and almost doubles the risk of neonatal and infant mortality, mental retardation and severe birth defects in children born to first cousins . Some ethnic groups, such as Ashkenazi Jews and Finns, have a relatively high prevalence of rare genetic mutations that lead to an increased risk of malformations.\n

\n

Infections

\n

\nMaternal infections such as syphilis or measles are a common cause of birth defects in low- and middle-income countries.

\n

Maternal nutrition

\n

\nDeficiencies in iodine, folate, obesity, or conditions such as diabetes mellitus are associated with some malformations. For example, folic acid deficiency increases the risk of having a baby with a neural tube defect. In addition, increased intake of vitamin A may affect the normal development of the embryo or fetus.

For example, folic acid deficiency increases the risk of having a baby with a neural tube defect. In addition, increased intake of vitamin A may affect the normal development of the embryo or fetus.

\n

Environmental factors

\n

\nMaternal exposure to certain pesticides and other chemicals, as well as certain drugs, alcohol, tobacco, psychoactive substances, or radiation during pregnancy may increase the risk of developing the fetus or a newborn baby with birth defects. Working or living near or close to landfills, smelters, or mines can also be a risk factor, especially if the mother is exposed to other environmental risk factors or malnutrition.

\n

Prevention

\n

\nPregnancy and conception preventive health care, and prenatal care, reduce the incidence of some birth defects. Primary prevention of malformations includes the following measures:

\n

- \n

- Improving the nutrition of women during the reproductive period by ensuring adequate intake of vitamins and minerals, especially folic acid, as a result of daily oral supplementation or fortification of staple foods, such as wheat or corn flour.

- Supervise that a pregnant woman does not consume or consume in a limited amount unhealthy foods, especially alcohol. \n

- Pre-pregnancy and pregnancy prevention of diabetes through counseling, weight management, proper nutrition, and, if necessary, insulin administration. \n

- Prevention of exposure to environmental hazardous substances (eg, heavy metals, pesticides, certain drugs) during pregnancy. \n

- Ensuring that any exposure of a pregnant woman to drugs or medical exposures (such as x-rays) is justified and based on a careful analysis of the health risks and benefits. \n

- Increase vaccination coverage for women and children, especially against rubella. This disease can be prevented by vaccinating children. Rubella vaccine may also be given at least one month before pregnancy to women who did not receive the vaccine or who did not have rubella in childhood. \n

- Increase vaccination coverage for women and children, especially against rubella virus.

This disease can be prevented by vaccinating children. Rubella vaccine may also be given to women who are not immune to the disease at least one month before pregnancy.

\n - Scaling up and intensifying training for health professionals and other staff involved in strengthening malformation prevention. \n

\n

Identification

\n

\nPre-conception (pre-conception) and near conception (peri-conception) health care includes basic reproductive health care as well as medical genetic screening and counseling. Screening can be carried out during the three periods listed below.

\n

- \n

- Pre-pregnancy screening is designed to identify people who are at risk of developing certain health conditions or at risk of passing on any health conditions to their children. Screening includes family medical history and vector screening. Screening is especially important in countries where incestuous marriages are common.

- Preconception screening: maternal characteristics may increase risk, and screening results should be used to provide appropriate care based on risk. During this period, screening of young and mature mothers, as well as screening for the use of alcohol, tobacco and other psychoactive substances, can be carried out. Ultrasound can be used to detect Down's syndrome during the first trimester of pregnancy and severe fetal malformations during the second trimester. Additional tests and amniocentesis help detect neural tube defects and chromosomal abnormalities during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy. \n

- Newborn screening includes a clinical examination and screening for hematological, metabolic, and hormonal disorders. Screening for deafness and heart disease, and early detection of birth defects, can facilitate life-saving treatment and prevent progression of the defect, which could lead to some form of physical, mental, or visual or hearing disability.

In some countries, all newborns are screened for thyroid and adrenal abnormalities before being discharged from the maternity ward.

\n

\n

Treatment and care

\n

\nIn countries with adequate health services, structural congenital malformations can be corrected with pediatric surgery and children with functional problems such as thalassemia (inherited by recessive blood disease), sickle cell disorders, and congenital hypothyroidism.

\n

WHO activities

\n

\nIn 2010, the World Health Assembly published a report on birth defects. The report outlines the main components of establishing national programs for the prevention and care of birth defects before and after birth. The report also recommends priority actions for the international community to help establish and strengthen such national programs.

\n

\nThe Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health, announced in September 2010 by the United Nations in collaboration with government leaders and other organizations such as WHO and UNICEF, plays a critical role in implementing efficient and cost-effective action to promote newborn and child health.\n

\n

\nWHO is also working with the National Center for Birth and Developmental Disorders, part of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other partners to develop a global policy to fortify foods with salt folic acid at the country level. In addition, WHO is working with partners to provide the necessary technical expertise to conduct surveillance of neural tube defects, monitor efforts to fortify foods with folic acid salts, and strengthen laboratory capacity to assess risks for birth defects prevented by folic acid salts.

\n

\nThe International Clearing House for Surveillance and Research on Birth Defects is a voluntary, non-profit, international organization in official relations with WHO. This organization collects surveillance data on birth defects and research programs around the world to study and prevent birth defects and mitigate their effects.

\n

\nThe WHO Departments of Reproductive Health and Research and Nutrition for Health and Development, in collaboration with the International Clearing House for Surveillance and Research on Birth Defects and the CDC National Center for Birth Defects and Development, organize annual seminars on surveillance and prevention of birth defects and preterm birth. The WHO Department of HIV/AIDS is collaborating with these partners to strengthen surveillance for malformations among women receiving antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy as an integral part of the monitoring and evaluation of national HIV programs.

\n

\nThe GAVI Alliance, partnered with WHO, is helping developing countries to increase the control and elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome through immunization.

\n

\nWHO is developing normative tools, including guidelines and a global action plan to strengthen health care and rehabilitation services in support of the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Similarly, WHO is helping countries integrate health care and rehabilitation services into general primary health care, supporting the development of community-based rehabilitation programs and strengthening specialized rehabilitation centers and their links with community-based rehabilitation centers.

\n

United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

\n

\nThe WHO Department of Public Health and Environment works across a range of activities and develops interventions to address the environmental and social determinants of child development. These include: child-only vulnerability to indoor and outdoor air pollution, water pollution, lack of basic hygiene, toxic compounds, heavy metals, waste components and radiation exposure; mixed impact of factors related to the social environment, professional activities and nutrition, as well as the living conditions of children (home, school).

\n

","datePublished":"2022-02-28T22:52:00.0000000+00:00","image":"https://cdn.who.int/media/images/default -source/imported/preterm-birth-mother-jpg.jpg?sfvrsn=c5c1adf1_0","publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"World Health Organization: WHO","logo": {"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.who.int/Images/SchemaOrg/schemaOrgLogo.jpg","width":250,"height":60}},"dateModified ":"2022-02-28T22:52:00.0000000+00:00","mainEntityOfPage":"https://www.who.int/ru/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/congenital-anomalies", "@context":"http://schema.org","@type":"Article"};

Key Facts

- It is estimated that 303,000 children die every year from malformations during the first 4 weeks of life.

- Developmental disabilities can lead to long-term disability, with significant impacts on individuals, their families, health systems and society.

- The most severe malformations include heart defects, neural tube defects and Down's syndrome.

- Although malformations may be genetic, infectious or environmental in origin, the exact cause is often difficult to establish.

- Some birth defects can be prevented. The main elements of prevention are, inter alia, vaccination, adequate intake of folic acid or iodine through fortification of staple foods or provision of nutritional supplements, and proper prenatal care.

Malformations and preterm birth are major causes of childhood death, chronic disease and disability in many countries. In 2010, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution calling on all Member States to promote primary prevention and health promotion for children with developmental disabilities through:

- development and strengthening of registration and surveillance systems;

- experience and capacity building;

- strengthening research and scientific work in the field of etiology, diagnosis and prevention;

- strengthening international cooperation.

Definition

Congenital malformations are also referred to as congenital malformations, congenital disorders or congenital deformities. Congenital malformations can be defined as structural or functional abnormalities (eg, metabolic disorders) that appear in utero and may be identified before birth, during birth, or later in life.

Causes and risk factors

Approximately 50% of all malformations cannot be attributed to any specific cause, but some causes or risk factors are known.

Socio-economic factors

While low income may be an indirect determinant, malformations are more likely to occur in under-resourced families and countries. It is estimated that approximately 94% of severe malformations occur in middle- and low-income countries, where women often do not have access to sufficient and good enough food and may be exposed to some agent or factor, such as infection or alcohol, that provokes or enhances deviations from the norm in prenatal development. Moreover, motherhood in adulthood increases the risk of chromosomal abnormalities, including Down's syndrome, while motherhood at a young age increases the risk of certain congenital malformations.

Genetic factors

Incest (consanguinity) increases the prevalence of rare genetic birth defects and almost doubles the risk of neonatal and infant mortality, mental retardation and severe birth defects in children born to first cousins. Some ethnic groups, such as Ashkenazi Jews and Finns, have a relatively high prevalence of rare genetic mutations that lead to an increased risk of malformations.

Infections

Maternal infections such as syphilis or measles are a common cause of birth defects in low- and middle-income countries.

Maternal nutrition

Deficiency of iodine, folic acid salts, obesity, or conditions such as diabetes mellitus are associated with some malformations. For example, folic acid deficiency increases the risk of having a baby with a neural tube defect. In addition, increased intake of vitamin A may affect the normal development of the embryo or fetus.

Environmental factors

Maternal exposure to certain pesticides and other chemicals, as well as certain drugs, alcohol, tobacco, psychoactive substances, or radiation during pregnancy may increase the risk of birth defects in the fetus or newborn. Working or living near or close to landfills, smelters, or mines can also be a risk factor, especially if the mother is exposed to other environmental risk factors or malnutrition.

Prevention

Preventive health care during pregnancy and conception, as well as antenatal care, reduce the incidence of some birth defects. Primary prevention of malformations includes the following:

- Improving the nutrition of women during the reproductive period by ensuring adequate intake of vitamins and minerals, especially folic acid, through daily oral supplementation or fortification of staple foods such as wheat or corn flour .

- Supervise that a pregnant woman does not consume or consume in a limited amount unhealthy foods, especially alcohol.

- Prevention of diabetes in pregnancy and during pregnancy through counseling, weight management, proper nutrition and, if necessary, insulin administration.

- Prevention during pregnancy of exposure to hazardous environmental substances (eg, heavy metals, pesticides, certain drugs).

- Ensuring that any exposure of a pregnant woman to drugs or radiation for medical purposes (eg x-rays) is justified and based on a careful analysis of the health risks and benefits.

- Increase vaccination coverage for women and children, especially against rubella virus. This disease can be prevented by vaccinating children. Rubella vaccine may also be given at least one month before pregnancy to women who did not receive the vaccine or who did not have rubella in childhood.

- Increase vaccination coverage for women and children, especially against rubella virus.

This disease can be prevented by vaccinating children. Rubella vaccine may also be given to women who are not immune to the disease at least one month before pregnancy.

- Scaling up and intensifying training for health professionals and other staff involved in strengthening the prevention of malformations.

Identification

Medical care before conception (in the preconception period) and around the time of conception (in the periconceptional period) includes basic reproductive health care, as well as medical genetic screening and counseling. Screening can be carried out during the three periods listed below.

- Pre-pregnancy screening is designed to identify people who are at risk of developing certain health conditions or passing on any health conditions to their children. Screening includes family medical history and vector screening. Screening is especially important in countries where incestuous marriages are common.

- Preconception screening: Maternal characteristics may increase risk and screening results should be used to provide appropriate care based on risk.

During this period, screening of young and mature mothers, as well as screening for the use of alcohol, tobacco and other psychoactive substances, can be carried out. Ultrasound can be used to detect Down's syndrome during the first trimester of pregnancy and severe fetal malformations during the second trimester. Additional tests and amniocentesis help detect neural tube defects and chromosomal abnormalities during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy.

- Newborn screening includes a clinical examination, as well as screening for hematological, metabolic and hormonal disorders. Screening for deafness and heart disease, and early detection of birth defects, can facilitate life-saving treatment and prevent progression of the defect, which could lead to some form of physical, mental, or visual or hearing disability. In some countries, all newborns are screened for thyroid and adrenal abnormalities before being discharged from the maternity ward.

Treatment and medical care

In countries with adequate health services, structural birth defects can be corrected with pediatric surgery and timely treatment can be provided for children with functional problems such as thalassemia (a recessive blood disorder), sickle cell disorders, and congenital hypothyroidism.

WHO activities

In 2010, the World Health Assembly published a report on birth defects. The report outlines the main components of establishing national programs for the prevention and care of birth defects before and after birth. The report also recommends priority actions for the international community to help establish and strengthen such national programs.

The Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health, launched in September 2010 by the United Nations in collaboration with government leaders and other organizations such as WHO and UNICEF, plays a critical role in achieving effective and cost-effective action to improve newborn health and children.

WHO is also working with the National Center for Birth and Developmental Disorders, part of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other partners to develop a global policy for folic acid fortification at the country level. In addition, WHO is working with partners to provide the necessary technical expertise to conduct surveillance of neural tube defects, monitor efforts to fortify foods with folic acid salts, and strengthen laboratory capacity to assess risks for birth defects prevented by folic acid salts.

The International Clearing House for Surveillance and Research on Birth Defects is a voluntary, non-profit international organization in official relations with WHO. This organization collects surveillance data on birth defects and research programs around the world to study and prevent birth defects and mitigate their effects.

The WHO Departments of Reproductive Health and Research and Nutrition for Health and Development, in collaboration with the International Clearing House for Surveillance and Research on Birth Defects and the CDC National Center for Birth Defects and Development, organize annual workshops on surveillance and prevention of birth defects and premature birth. The WHO Department of HIV/AIDS is collaborating with these partners to strengthen surveillance for malformations among women receiving antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy as an integral part of the monitoring and evaluation of national HIV programs.

The GAVI Alliance, with WHO among its partners, is helping developing countries to accelerate the control and elimination of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome through immunization.

WHO is developing normative tools, including guidelines and a global action plan to strengthen health care and rehabilitation services in support of the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Similarly, WHO is helping countries integrate health care and rehabilitation services into general primary health care, supporting the development of community-based rehabilitation programs and strengthening specialized rehabilitation centers and their links with community-based rehabilitation centers.

UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The WHO Department of Public Health and Environment works across a range of activities and develops interventions to address the environmental and social determinants of child development. These include: child-only vulnerability to indoor and outdoor air pollution, water pollution, lack of basic hygiene, toxic compounds, heavy metals, waste components and radiation exposure; mixed impact of factors related to the social environment, professional activities and nutrition, as well as the living conditions of children (home, school).

Anomaly of the mammary glands (congenital) - diagnosis and treatment at the medical center "Andreev Hospitals"

Anomalies of the mammary glands include diseases associated with a violation of the location, quantity, size of the mammary glands, as well as nipples and areola. 3% of cases among all diseases of the mammary glands.Most often, the anomaly occurs in women, but can also develop in men.

This pathology is the reason why patients turn to plastic surgeons, since only a surgical method can get rid of the anomaly.

Causes of anomalies of the mammary glands

The most common causes of pathology lie in the violation of intrauterine development. The laying of the mammary glands begins at the sixth week of pregnancy. Already from the third month, the milk ducts are formed. Further on the seventh week, areolas and nipples appear. After birth, the development of the mammary glands continues until the child reaches two years of age.

Taking medications, stress, pathology of the course of pregnancy can lead to a change in this cycle and, as a result, to anomalies in the development of the mammary glands.

Classification of anomalies of the mammary glands

The following classification is most often used:

- The first group consists of true defects. They develop against the background of hereditary diseases and pathologies that have arisen in the embryonic period.

- The second group includes pathologies caused by hormonal disorders, trauma, infection, and so on.

Types of anomalies of the mammary glands

Depending on the type of anomaly, the following forms of pathology are distinguished:

- Quantity anomalies. This includes monomastia. This is a unilateral absence of the mammary gland. Polymastia is characterized by the presence of additional mammary glands. Polythelia differs from polymastia in that with this pathology there is only an additional nipple without breast tissue. There may also be an atelier. It's the absence of nipples. The anomaly occurs even with normally developed mammary glands.

- Position and shape anomalies. Ectopia of the mammary gland or its displacement. However, it can be full or underdeveloped. Micromastia, or hypomastia, is characterized by the small size of the mammary glands. This pathology can also be observed either on one side or on both sides. The severity of symptoms depends on various factors. As a rule, the asymmetry of the mammary glands to one degree or another is observed in most women. But in some cases it is especially pronounced, which makes patients seek help from a specialist. Macromastia, on the contrary, is accompanied by a pronounced growth of the gland. As for the nipples, most often the anomaly is associated with their shape. It could be an inverted or flat nipple. There is also an expansion of the boundaries of the alveoli.

Treatment of mammary anomalies

As a rule, most of the anomalies are diagnosed immediately after birth, but it is possible that the pathology appears only during puberty.