Milk let down hormone

Let-down reflex | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

Let-down reflex | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content3-minute read

Listen

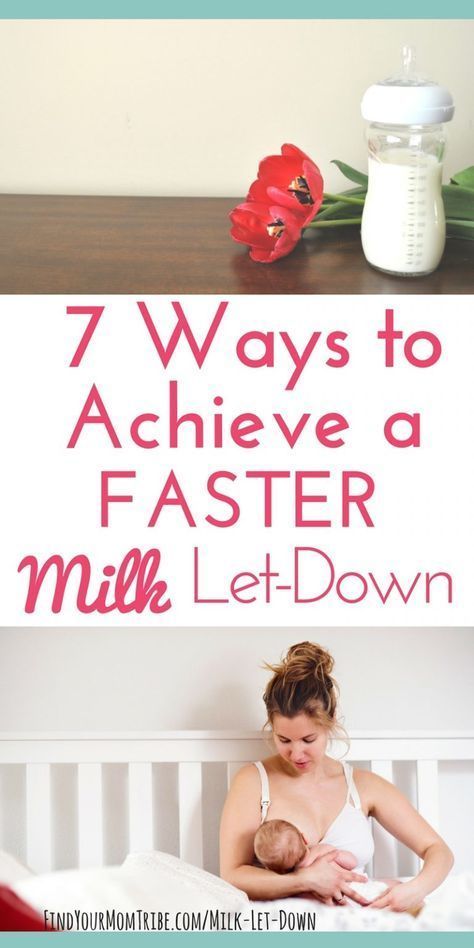

The let-down reflex is an important part of breastfeeding that starts milk flowing when your baby feeds. Each woman feels it differently, and some may not feel it at all. It can be affected by stress, pain and tiredness but once feeding is established, it requires little or no thought.

What is the let-down reflex?

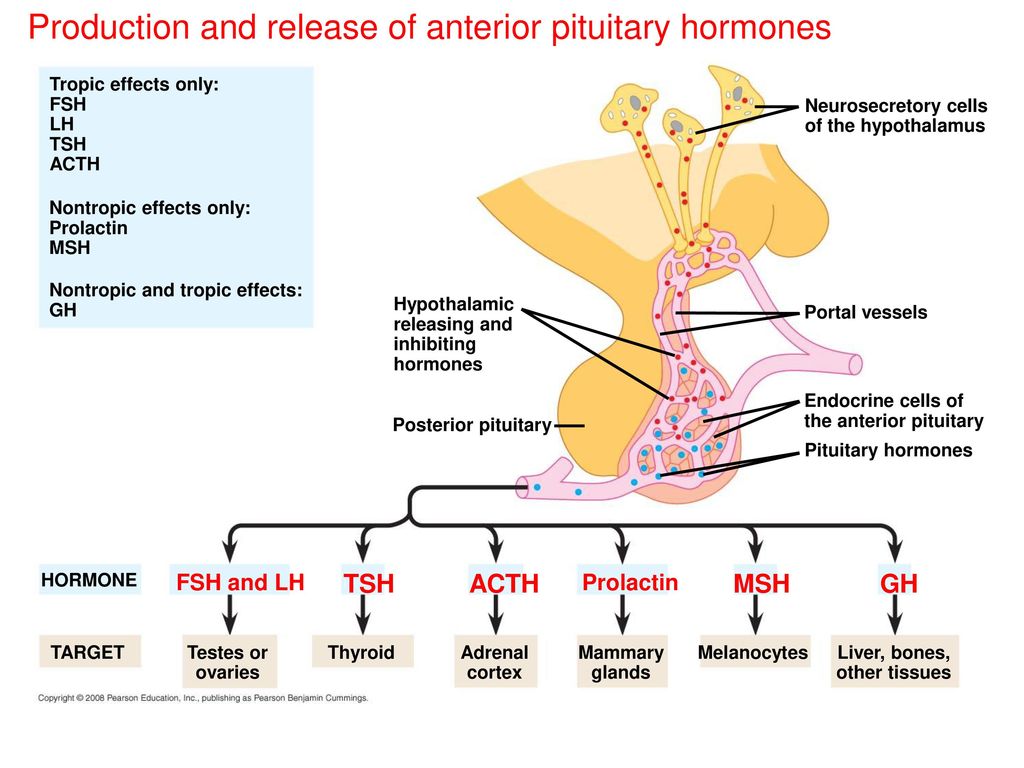

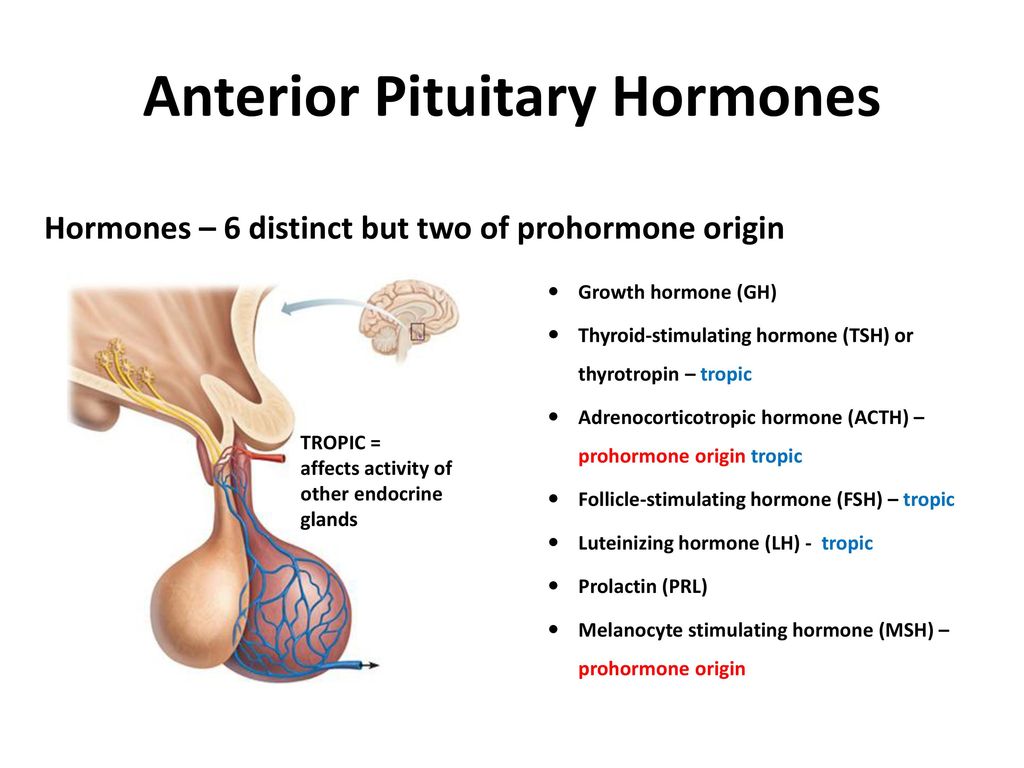

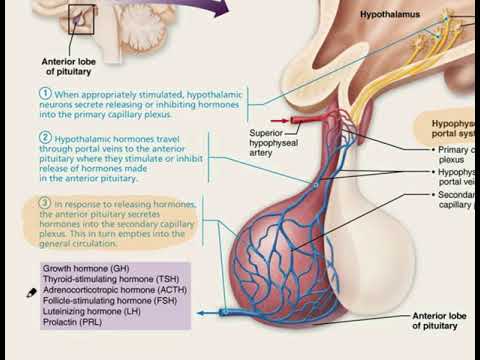

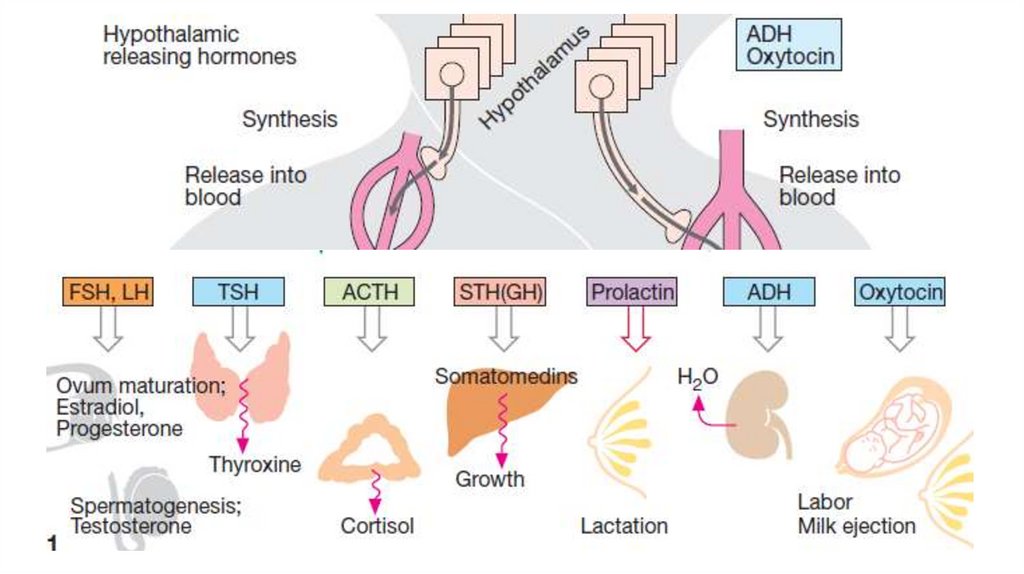

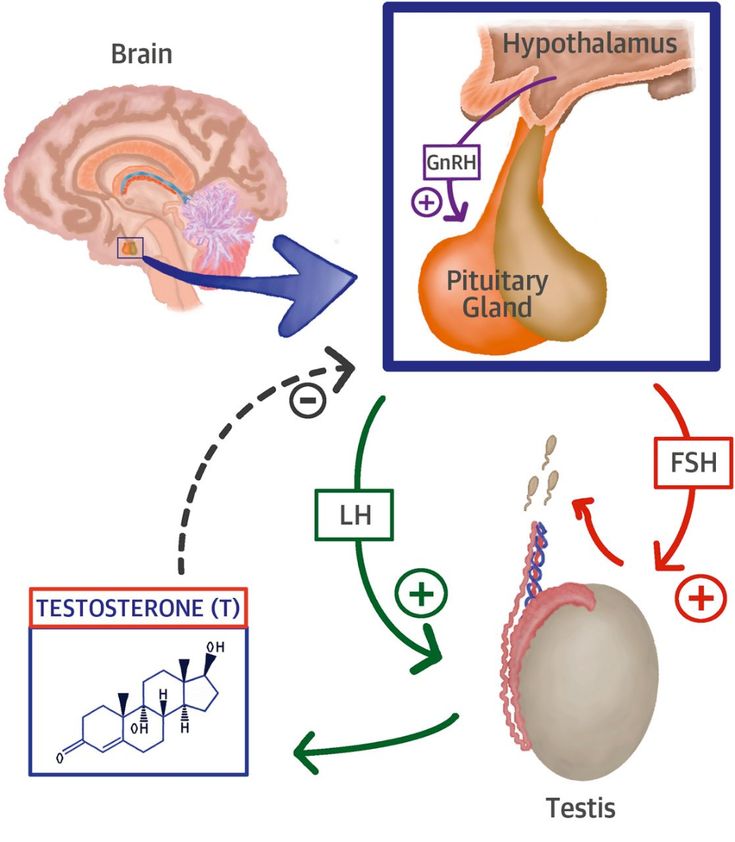

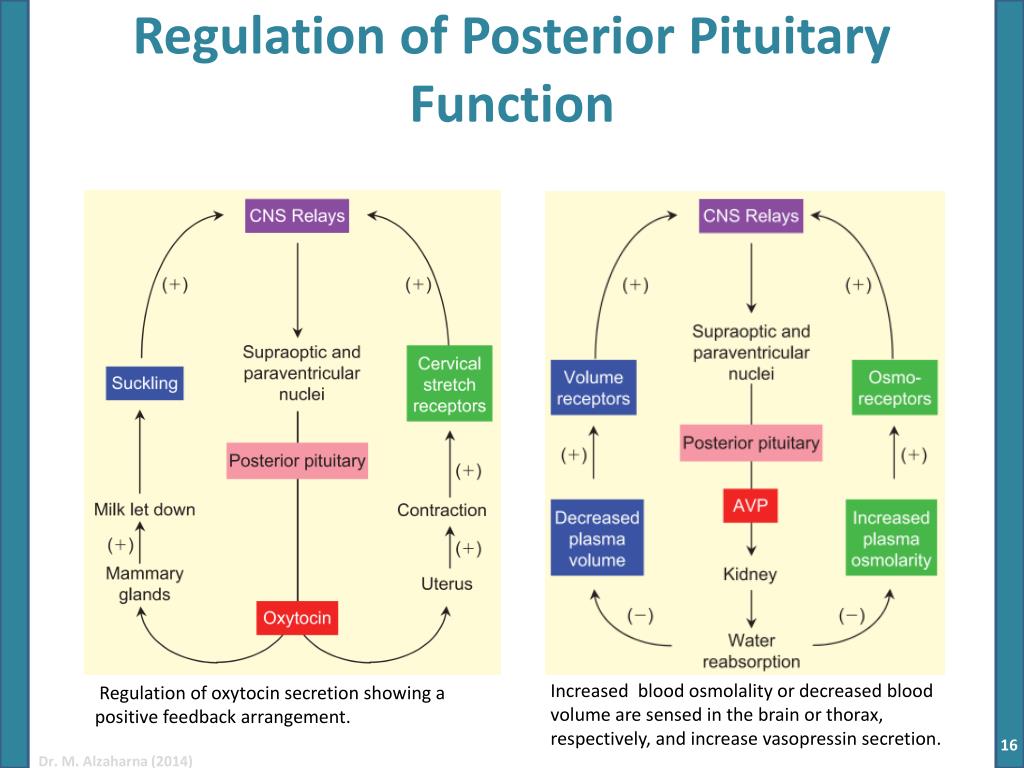

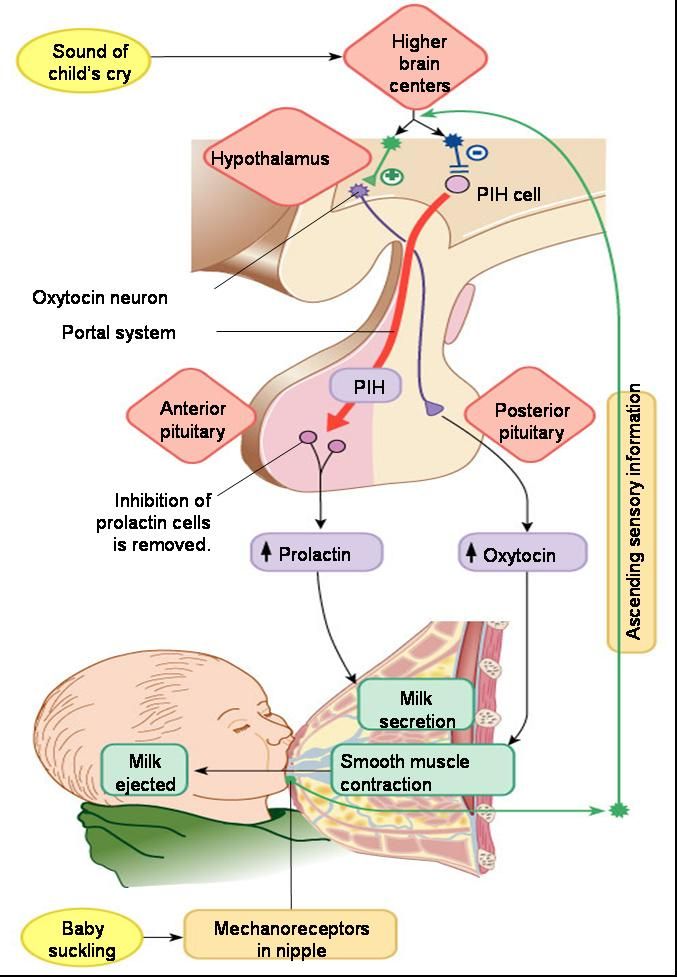

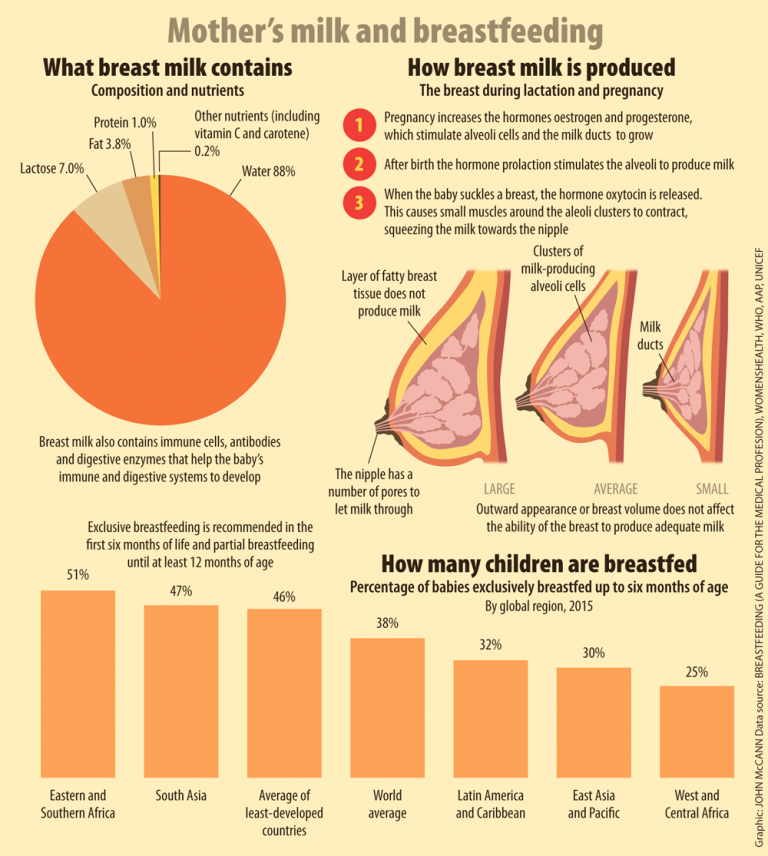

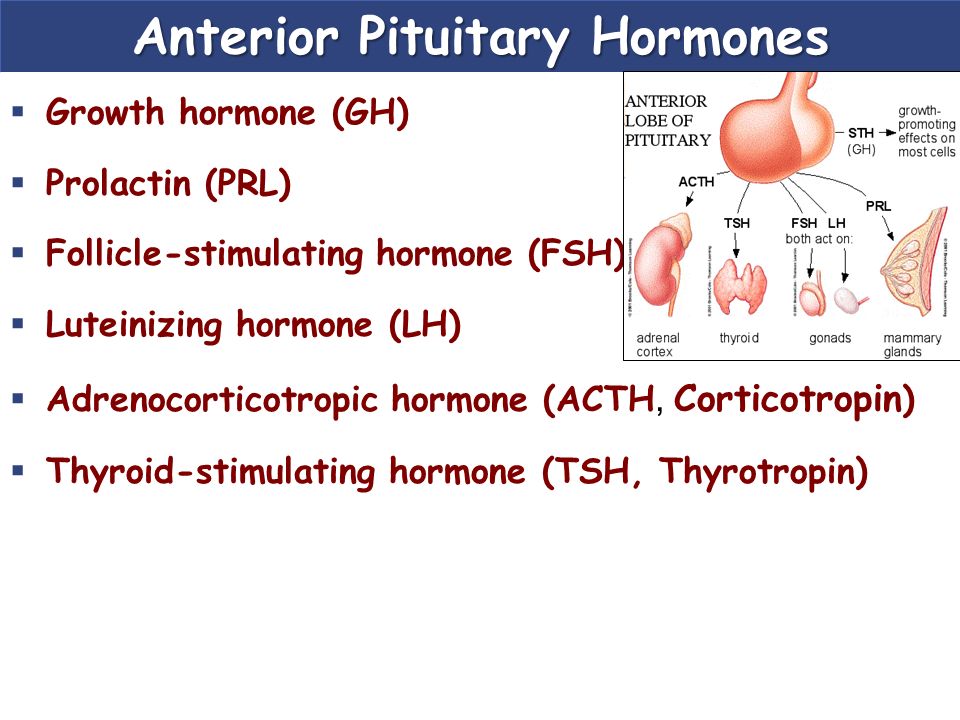

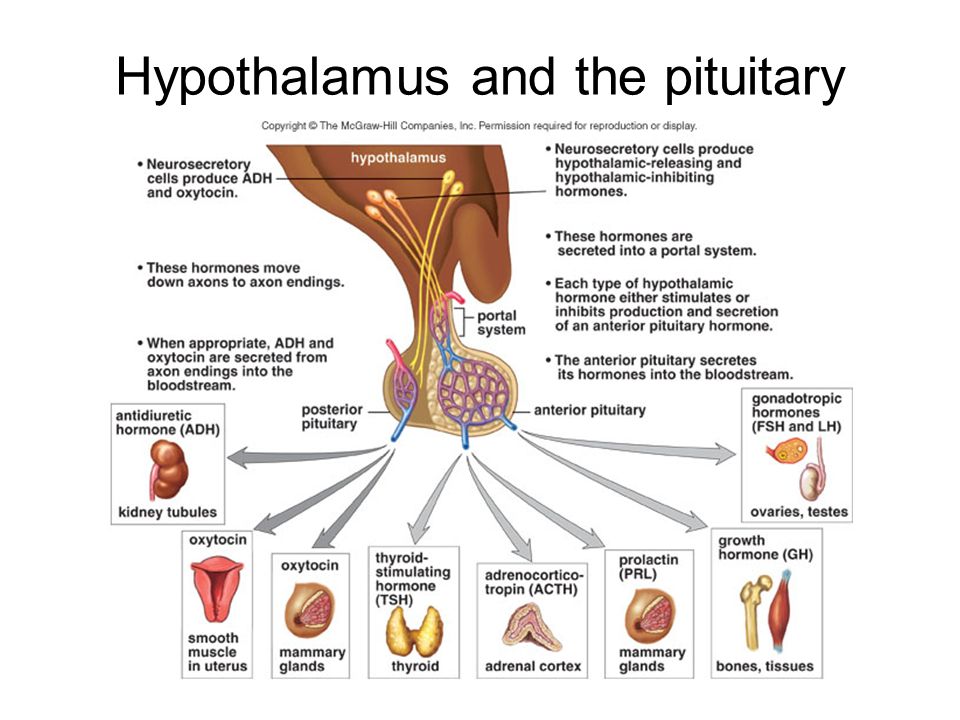

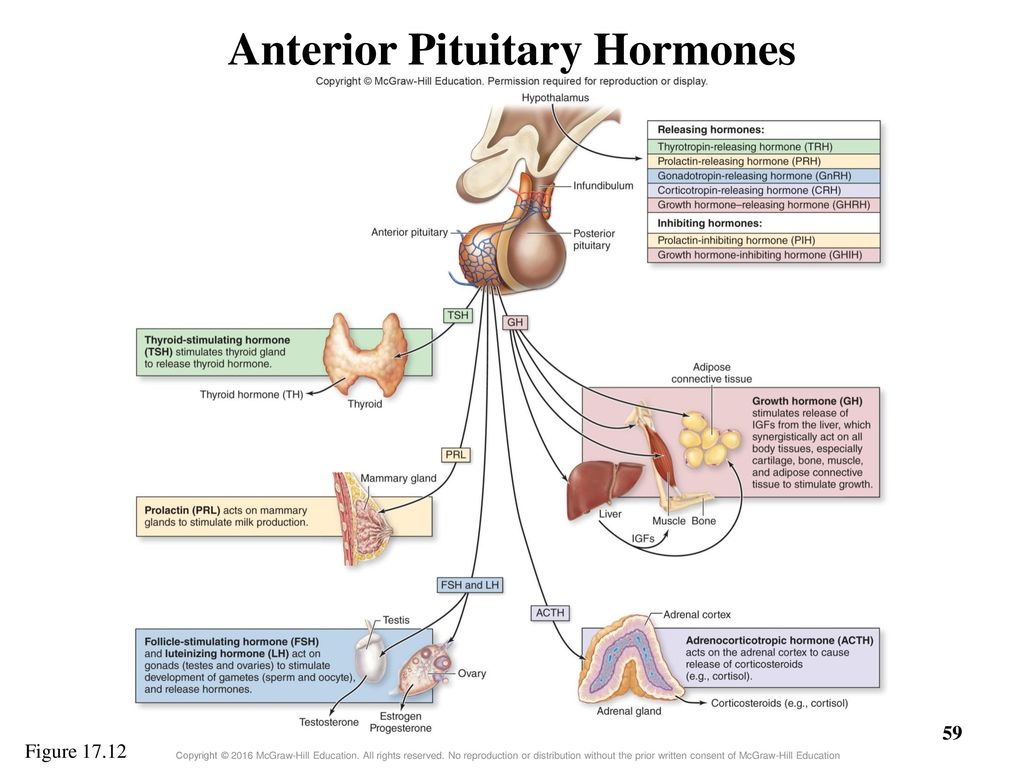

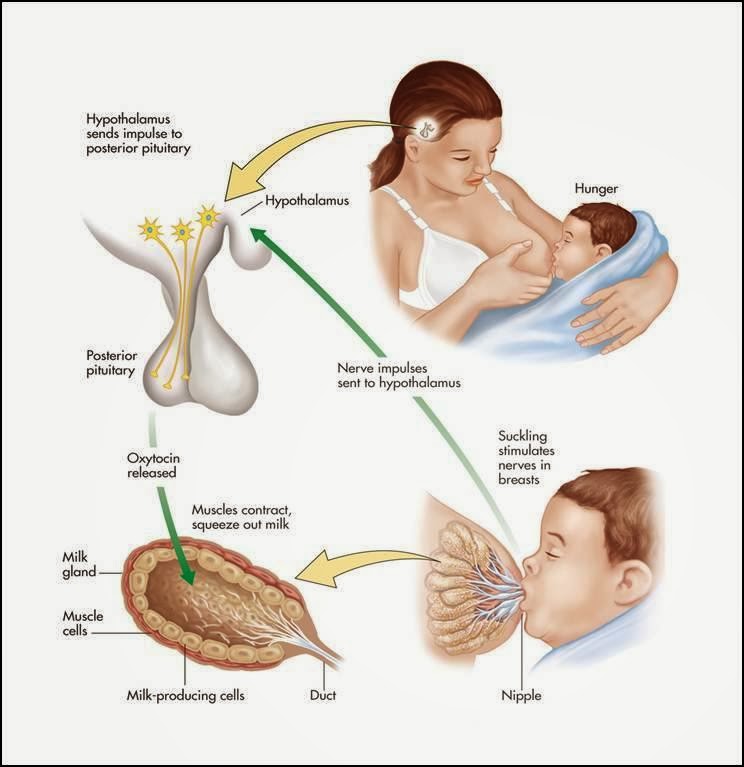

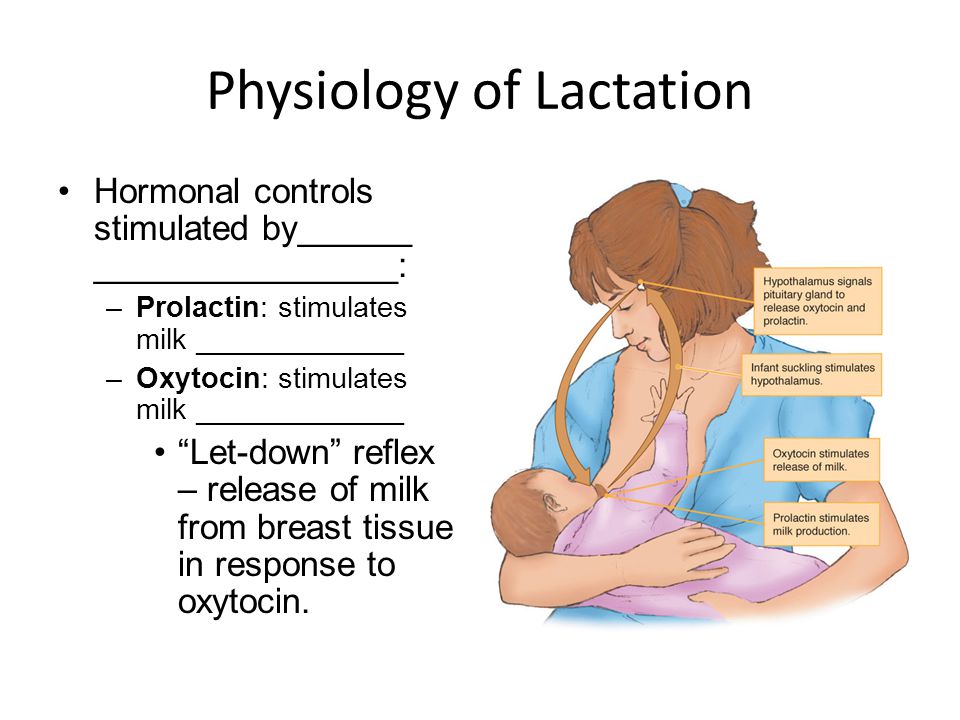

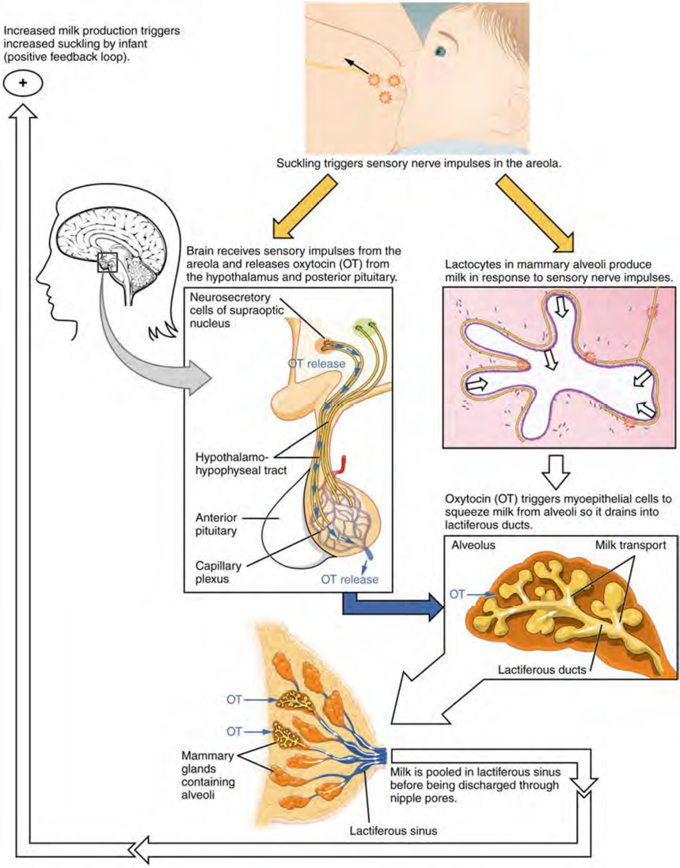

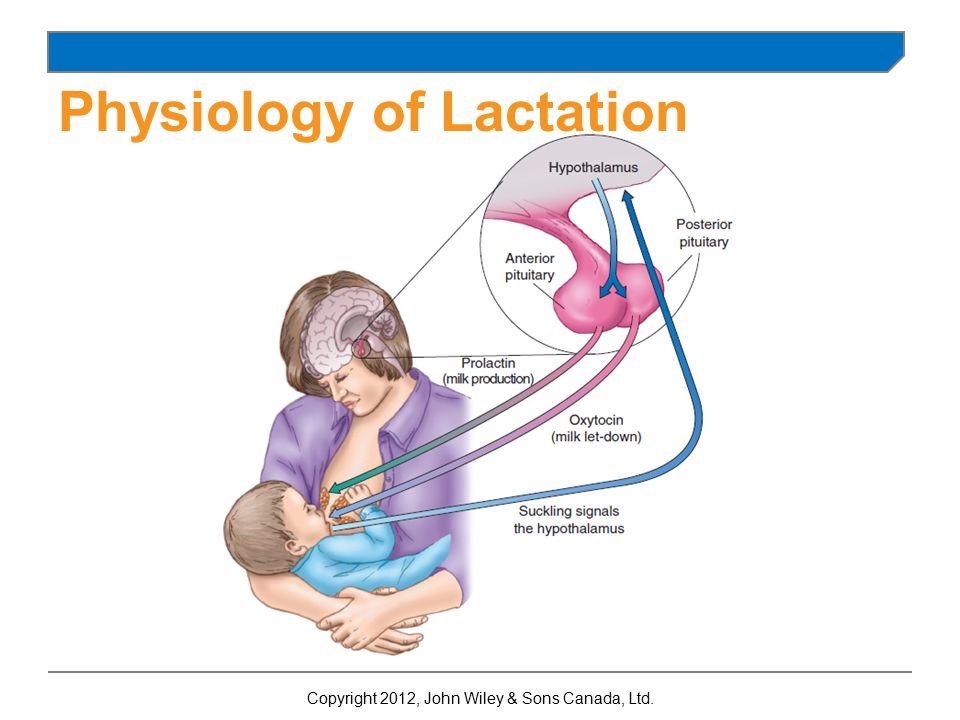

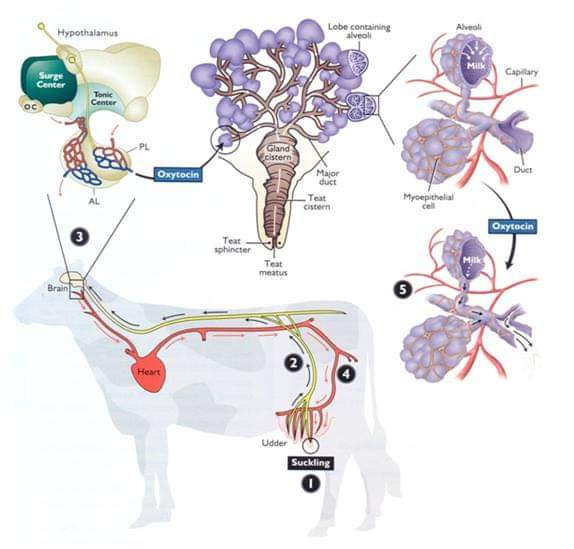

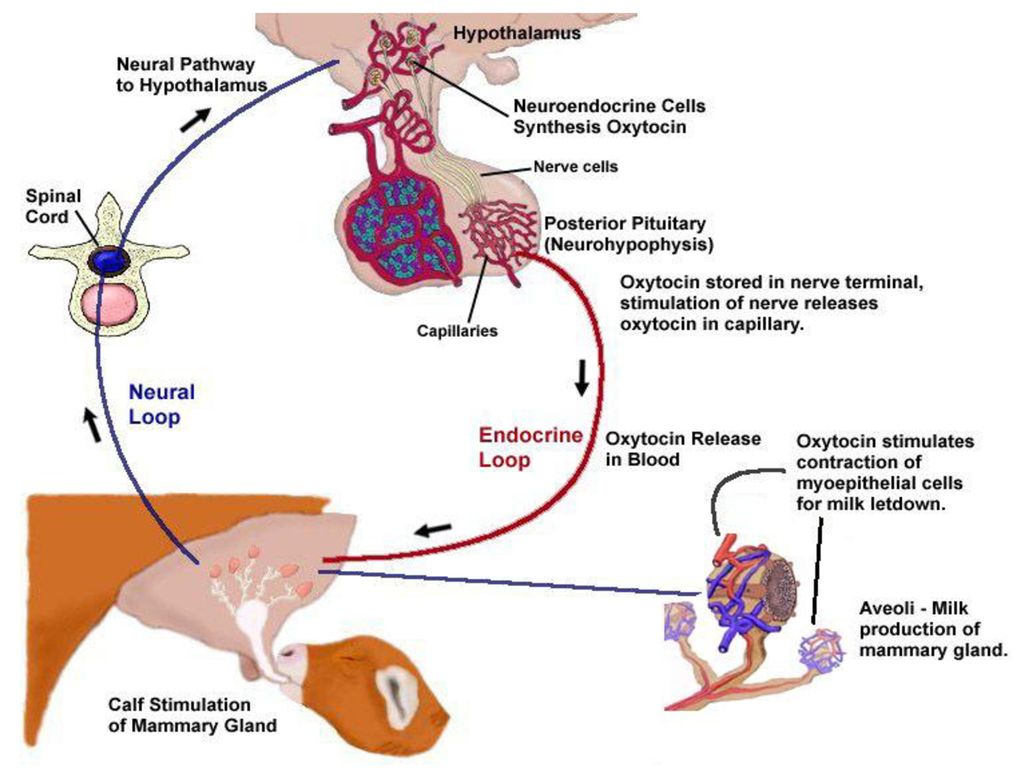

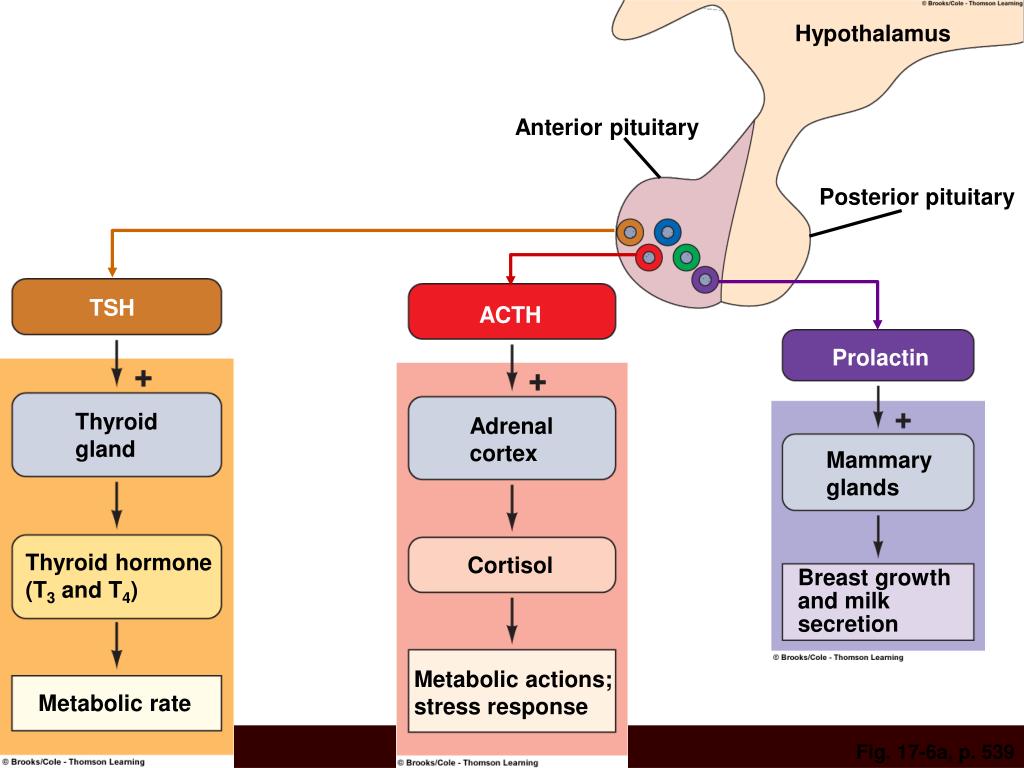

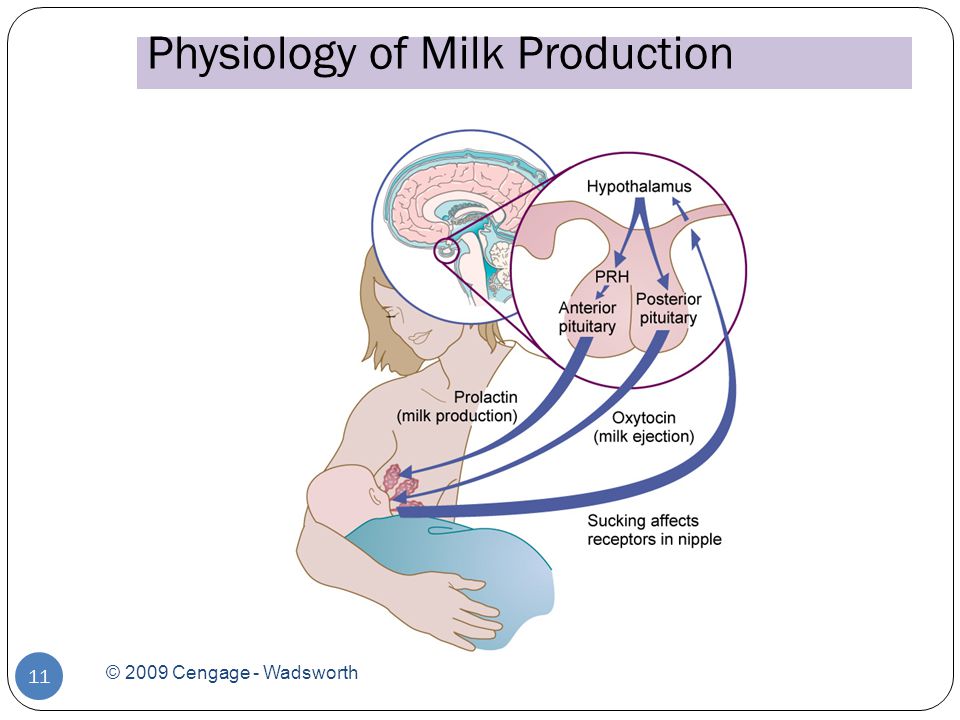

The let-down reflex is what makes breastmilk flow. When your baby sucks at the breast, tiny nerves are stimulated. This causes two hormones – prolactin and oxytocin – to be released into your bloodstream. Prolactin helps make the milk, while oxytocin causes the breast to push out the milk. Milk is then released or let down through the nipple.

Some women feel the let-down reflex as a tingling sensation in the breasts or a feeling of fullness, although others don’t feel anything in the breast.

Most women notice a change in their baby’s sucking pattern as the milk begins to flow, from small, shallow sucks to stronger, slower sucks.

Some women also notice, while feeding or expressing from one breast, that milk drips from the other.

Your let-down reflex needs to be established and maintained to ensure a good supply of milk. This reflex requires no thought, unless you are having problems with breastfeeding.

When does it occur?

The let-down reflex occurs:

- in response to your baby sucking at the breast

- hearing, seeing or thinking about your baby

- using a breast pump, hand expressing or touching your breasts or nipples

- looking at a picture of your baby

- hearing your baby (or another baby) cry

The let-down reflex generally occurs 2 or 3 times a feed. Most women only feel the first, if at all. This reflex is not always consistent, particularly early on, but after a few weeks of regular breastfeeding or expressing, it becomes an automatic response.

Most women only feel the first, if at all. This reflex is not always consistent, particularly early on, but after a few weeks of regular breastfeeding or expressing, it becomes an automatic response.

The let-down reflex can also occur with other stimulation of the breast, such as by your partner.

Strategies to encourage the reflex

The let-down reflex can be affected by stress, pain and tiredness. There are many things to try if you are experiencing difficulty.

- Ensure that your baby is correctly attached to the breast. A well-attached baby will drain a breast better.

- Feed or express in a familiar and comfortable environment.

- Try different methods to help you to relax: calming music, a warm shower or a warm washer on the breast, some slow deep breathing, or a neck and shoulder massage.

- Gently hand express and massage your breast before commencing the feed.

- Look at and think about your baby.

- If you are away from your baby, try looking at your baby’s photo.

- Always have a glass of water nearby.

Milk let-down can be quite forceful, particularly at the beginning of a feed. This fast flow of milk can upset your baby, but it might not mean you have oversupply. It can be managed through expressing before a feed, reclining slightly and burping your baby after the first few minutes. If you continue to have problems, seek advice.

How to deal with unexpected let-down

Until you and your baby fine-tune breastfeeding, many sensations and thoughts can trigger your let-down reflex. Leaking breasts can be embarrassing, but should stop once breastfeeding is fully established.

In the meantime you can feed regularly, apply firm pressure to your breasts when you feel the first sensation of let-down, use breast pads and wear clothing that disguises milk stains.

If you need help and advice:

- Pregnancy Birth and Baby on 1800 882 436

- your maternal child health nurse

- a lactation consultant (your maternity hospital might be able to help)

- Australian Breastfeeding Association on 1800 686 268

Sources:

Australian Breastfeeding Association (Breastfeeding - naturally : the Australian Breastfeeding Association's guide to breastfeeding - from birth to weaning), Australian Breastfeeding Association (Let-down reflex)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: April 2021

Back To Top

Related pages

- Breastfeeding your baby

- How to increase breast milk supply

- Oversupply of breastmilk

Need more information?

Breastfeeding challenges - Ngala

Sometimes breastfeeding can be challenging

Read more on Ngala website

Breast refusal and baby biting breast | Raising Children Network

Breast refusal or baby biting breast are common breastfeeding issues. These issues might resolve themselves, or your child and family health nurse can help.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Breastfeeding - expressing breastmilk - Better Health Channel

Expressing breast milk by hand is a cheap and convenient method.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Breast feeding your baby - MyDr.com.au

Breast milk has long been known as the ideal food for babies and infants. Major health organisations recommend that women breast feed their babies exclusively until they are 6 months old, and continue breast feeding, along with solids, until they are 12 months old or more. Breast milk has many benefits.

Read more on myDr website

Expressing and storing breast milk

This page includes information about expressing, storing, cleaning equipment, transporting and preparing expressed breastmilk for your baby.

Read more on WA Health website

Expressing breastmilk & storing breastmilk | Raising Children Network

You can express breastmilk by hand, or with a manual or an electric pump. Store expressed breastmilk in special bags or containers in the fridge or freezer.

Store expressed breastmilk in special bags or containers in the fridge or freezer.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Mastitis, blocked duct & breast abscess | Raising Children Network

If you think you have a blocked milk duct, you can treat it at home to start with. If you think you have mastitis or a breast abscess, see your GP as soon as possible.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Weaning at 6 Months | Tresillian

Babies start weaning when they begin consuming foods other than breastmilk. For advice on weaning check out Tresillian's tip page.

Read more on Tresillian website

Frequently asked questions about alcohol and pregnancy | FASD Hub

We've answered some common questions about alcohol use during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and about living with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD).

Read more on FASD Hub Australia website

Breastfeeding challenges - Ngala

Many new mothers experience breastfeeding challenges

Read more on Ngala website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

OKNeed further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Subscribe to newsletters

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Healthdirect Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners and to Elders both past and present.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

What is D-MER? - La Leche League International

An interview with Alia Macrina Heise, IBCLC and Diane Wiessinger, IBCLC

Originally published July 07 2016, republished with express permission

Photos: Suzie Blake

D-MER (Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex)

Alia Macrina Heise is an International Board Certified Lactation Counselor who suffered some intense negative emotions while breastfeeding her third baby. When her milk let down she felt unpleasant and uncomfortable. Breastfeeding Today asked Alia and Diane Wiessinger, IBCLC, some questions to learn something about these bad feelings and the naming of the condition.

When her milk let down she felt unpleasant and uncomfortable. Breastfeeding Today asked Alia and Diane Wiessinger, IBCLC, some questions to learn something about these bad feelings and the naming of the condition.

Alia, can you tell us please about the feelings you experienced when nursing your baby?

The best way to understand my feelings during a D-MER is to refer to what I wrote in 2007. These are excerpts from my first post on D-MER in a thread titled “Only When Nursing” in the Postpartum Depression section of a natural parenting forum:

It’s a sickening feeling in the pit of my stomach. There is a strong aversion to food. I don’t feel sad, but I feel “icky and yucky.” It is a feeling I seem to have associated with strong feelings of worry and guilt in the past, because when I first started experiencing the sensation I kept searching for what I was feeling guilty or worried about. It turns out that there was nothing. It was just that same sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach that makes me lose my appetite that I had experienced in the past for these other reasons.

I then began to analyze not just what the emotions were, but when they occurred, how long they lasted and so on. When I first realized I was having these negative emotional surges throughout the day, I was very unsure of what could be causing them or even where to begin looking. At first I didn’t connect them with breastfeeding, because they happened before let-down and they happened with every let-down I had, including spontaneous let-downs—of which I had many. By the time I finally found a particular thread on a forum that helped me put two and two together, my baby was almost a month old. I began to track and document them and posted this:

The way I am feeling is connected to feeding and milk. The reason I didn’t realize it before is because it is related to LET-DOWN specifically. In fact, now I can tell a let-down is coming because of how I SUDDENLY feel. A let-down in between feedings is much worse. I can tell I am about to let-down (about 60–90 seconds after the emotions hit) because of how I feel. It’s a horrid feeling lasting about two minutes. This happens several times during a feeding, but those times are not nearly as intense as the emotional feelings I get in between feedings during a spontaneous let-down. I think this is because during feeding I am at least feeling more connected to my baby and the nice feelings of nursing and so the yucky emotional stuff is easier to ignore.

It’s a horrid feeling lasting about two minutes. This happens several times during a feeding, but those times are not nearly as intense as the emotional feelings I get in between feedings during a spontaneous let-down. I think this is because during feeding I am at least feeling more connected to my baby and the nice feelings of nursing and so the yucky emotional stuff is easier to ignore.

I feel able to cope with it, as because I know now what it is and why. I think also as time goes on (my baby is four weeks now) it gets less intense. I lost a lot of weight quickly in the beginning because food always sounded so horrible.

I am able to eat now … it just sometimes doesn’t sound good at the moment or after I eat, I momentarily wish I hadn’t.

My biggest thought right now is about NAMING this. If there are so many of us and it seems to be mostly unheard of, it ought to have a name. Also as a breastfeeding counselor I would take comfort in knowing what this issue IS.

Were you suffering from postnatal depression?

I was not. When I was not in the act of breastfeeding, and even in-between let-downs, I felt normal and fine. It was an extremely emotional roller coaster to go from a normal or good mood to crashing down into a D-MER “state” only to bounce right back up again.

When I was not in the act of breastfeeding, and even in-between let-downs, I felt normal and fine. It was an extremely emotional roller coaster to go from a normal or good mood to crashing down into a D-MER “state” only to bounce right back up again.

What led you to investigate your condition?

Since I had breastfed my previous two children “normally” and this was the first time experiencing the phenomenon of D-MER, I knew this was something “not quite right” and that there must be an explanation. So after discovering that my awful feelings were directly related to let-down, I went looking for answers. I was a lactation counselor working for WIC ( US based Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) and had been in the arena of breastfeeding helpers for four years. I had never heard of such a thing happening to another breastfeeding mother, but asked myself, “Why would I be the only one?” But my first attempts at information gathering, of delving into lactation texts, came up empty. So I went to the next obvious place—the Internet and lactation professionals. I started doing archive searches on Lactworld (a major online resource for the breastfeeding support community, previously called Lactnet), which helped lead me to Diane.

So I went to the next obvious place—the Internet and lactation professionals. I started doing archive searches on Lactworld (a major online resource for the breastfeeding support community, previously called Lactnet), which helped lead me to Diane.

How did you find other mothers who were suffering similar feelings when breastfeeding?

In 2008, when I first experienced it, you could Google words like “sadness while nursing,” “depression with milk ejection” or “anxiety before let-down” and get no answers. I went to the breastfeeding and postpartum depression forums of a popular, natural parenting forum and lurked. I wish I could say I was brave enough to post the question myself. But I had personal doubts. At that point I had not been able to dig up any information and I was starting to think that it was all in my head or an oppressed memory or some emotional quirk that would label me a “failure as a mother.”

But the online mother forums led the way. I finally found that first thread—it had the words that made me sit up and say out loud, “Aha! I’m NOT the only one. ” Once that was established it was a matter of finding out how not alone I actually was—the Internet to the rescue. Armored with the knowledge that I was not a lone freak, and that surely this was hormonally based, I started posting and posting and posting. As a result I found hundreds of women had had very similar experiences in the past or were currently experiencing it. And they had—with the exception of one or two—all been lurking as I was, afraid to post, afraid to be the first one to ask. (One or two women had asked before me but their threads had gotten buried and ignored in the end.) It was about timing, numbers and persistence. Persistence was something I wasn’t short on. I started a blog after I had exhausted the forums, and ultimately started www.d-mer.org in order to get information and support out to other mothers and to medical lactation professionals. Today, Google just the acronym “D-MER”, and you get well over a half-million results.

” Once that was established it was a matter of finding out how not alone I actually was—the Internet to the rescue. Armored with the knowledge that I was not a lone freak, and that surely this was hormonally based, I started posting and posting and posting. As a result I found hundreds of women had had very similar experiences in the past or were currently experiencing it. And they had—with the exception of one or two—all been lurking as I was, afraid to post, afraid to be the first one to ask. (One or two women had asked before me but their threads had gotten buried and ignored in the end.) It was about timing, numbers and persistence. Persistence was something I wasn’t short on. I started a blog after I had exhausted the forums, and ultimately started www.d-mer.org in order to get information and support out to other mothers and to medical lactation professionals. Today, Google just the acronym “D-MER”, and you get well over a half-million results.

What did your investigations reveal?

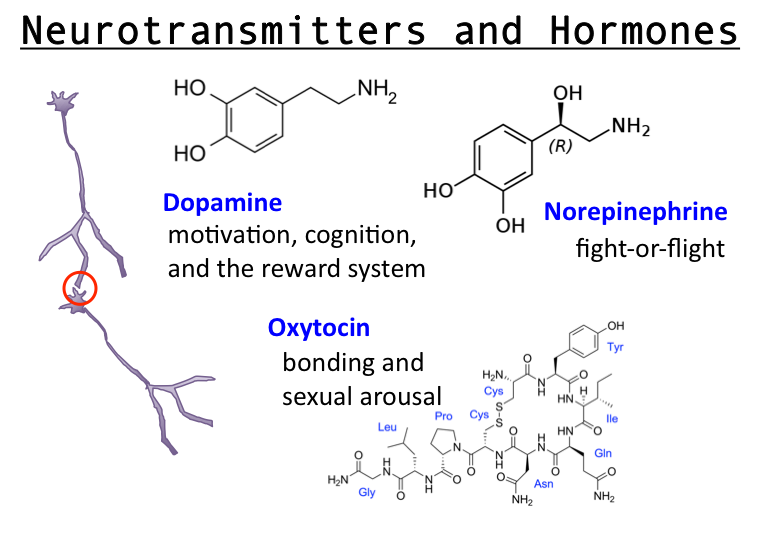

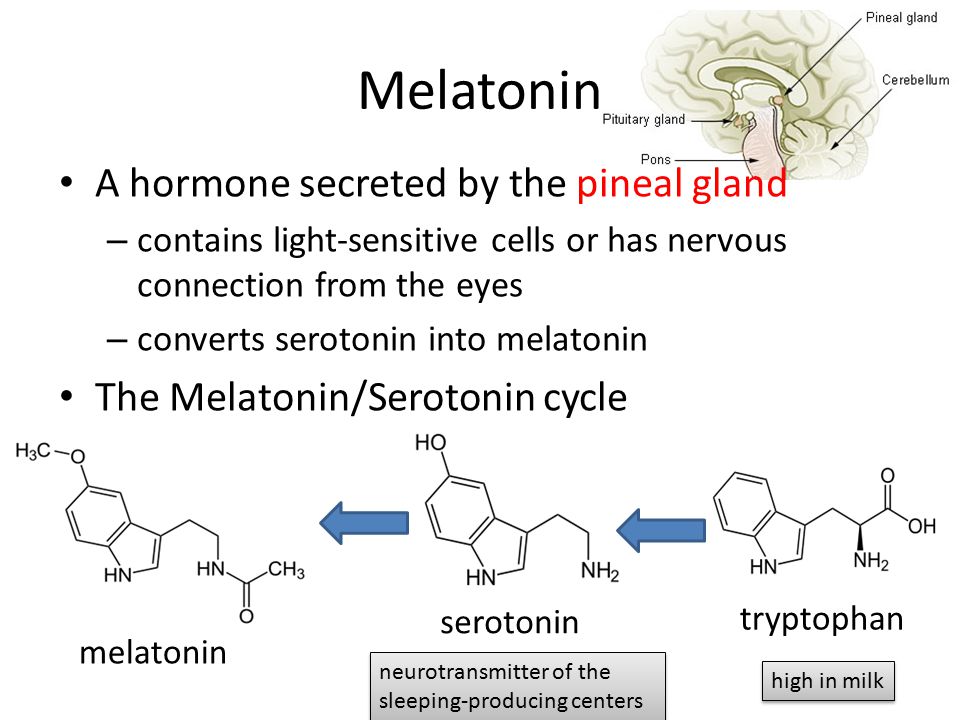

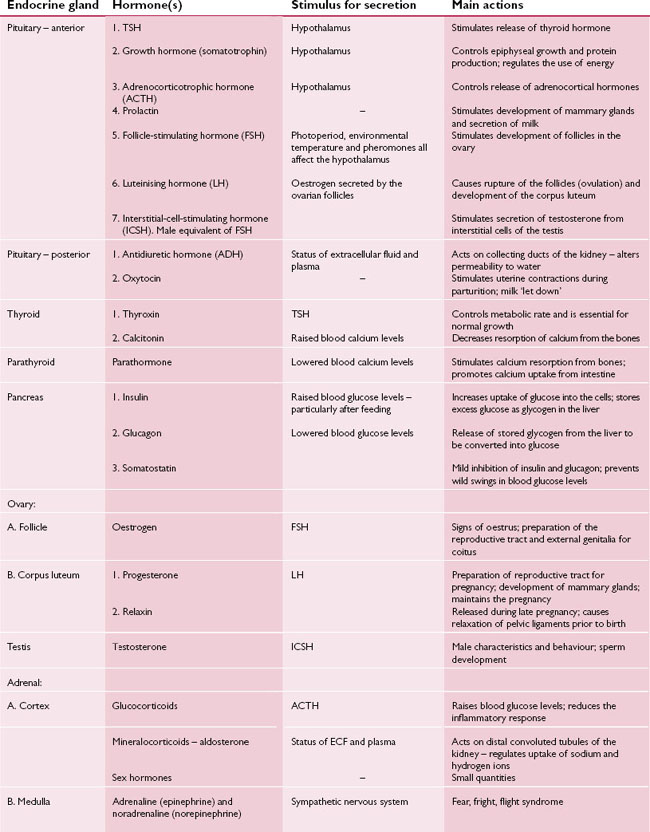

We were able to confirm quickly that it was a physiological reaction, not a psychological one. Based on its behavior we were able to deduce that it was a hormonal reaction. We really needed to find out which hormones were doing what. We consulted with oxytocin specialists, prolactin experts, lactation professionals who studied thyroid function, and those in the field of endocrinology. The word dopamine was finally brought into the conversation. There’s just not much information out there yet about dopamine and its role in human lactation. We did find out that for prolactin to be involved in lactation, dopamine has to get involved, too. Once we were able to start asking the right questions about the right hormones to the right people we made progress. Then we started experimenting with the idea of dopamine: looking at what increases dopamine, what inhibits it and how these things affect a mother’s D-MER. It sure seemed that anything that caused an increase in dopamine alleviated a mother’s D-MER.

Based on its behavior we were able to deduce that it was a hormonal reaction. We really needed to find out which hormones were doing what. We consulted with oxytocin specialists, prolactin experts, lactation professionals who studied thyroid function, and those in the field of endocrinology. The word dopamine was finally brought into the conversation. There’s just not much information out there yet about dopamine and its role in human lactation. We did find out that for prolactin to be involved in lactation, dopamine has to get involved, too. Once we were able to start asking the right questions about the right hormones to the right people we made progress. Then we started experimenting with the idea of dopamine: looking at what increases dopamine, what inhibits it and how these things affect a mother’s D-MER. It sure seemed that anything that caused an increase in dopamine alleviated a mother’s D-MER.

In 2011, Diane and I published my experiences, those of other mothers, and our educated guesses in International Breastfeeding Journal, an open-access online professional journal. [Mothers can download the PDF for Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex: a case report.]

[Mothers can download the PDF for Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex: a case report.]

What led you to give a name to these feelings?

Quite simply, I, along with the other women I was working with, got tired of calling it “it.” We realized that there are other conditions (such as Sheehan’s syndrome) with a much lower prevalence than the condition I was experiencing that have been named and included in every professional lactation text. There was no reason not to name it and many reasons to do so. The word “dysphoria” is a medical term and means an unpleasant or uncomfortable mood, such as sadness (depressed mood), restlessness, anxiety, or irritability. Etymologically, it is the opposite of euphoria. This described it perfectly. Because the condition was directly related to the milk ejection reflex, or let-down, we chose the term dysphoric milk ejection reflex (D-MER). For the women who experience it, D-MER is part of every MER to some degree (usually less intense as the feeding goes on, although not always). LLL Leader and International Board Certified Lactation Consultant Diane Wiessinger, MS, is interested in learning more about this phenomenon, too.

LLL Leader and International Board Certified Lactation Consultant Diane Wiessinger, MS, is interested in learning more about this phenomenon, too.

Diane, what do you think is happening to these mothers who are experiencing such negative feelings when letting down their milk?

Well, it’s been an interesting, twisty-turny path! When Alia first emailed me, I did what every other person she’d approached did. I said that it sounded like some sort of postpartum depression and suggested she look for help along those lines. I basically “blew her off.” It must have made her grind her teeth in frustration! A couple months later she called me, and this time I really, truly listened (those LLL Leader skills!). From what she described, it was pretty clearly physiological, and not psychological, not some sort of past trauma coming to the surface.

It was too … mechanical. This triggers it, that doesn’t. This makes it worse, that makes it better. She took some pseudoephedrine for a cold at one point. She didn’t realize that pseudoephedrine can wreak havoc with a milk supply, and happily, or maybe significantly, it didn’t. Within hours, D-MER had disappeared altogether, and she called to ask, “What happened?!” Her D-MER came back as the pseudoephedrine wore off.

She didn’t realize that pseudoephedrine can wreak havoc with a milk supply, and happily, or maybe significantly, it didn’t. Within hours, D-MER had disappeared altogether, and she called to ask, “What happened?!” Her D-MER came back as the pseudoephedrine wore off.

We brainstormed with others who were willing to hear us out without labeling it “depression.” We drew up a chart of what made it better and what made it worse, and looked at how those drugs or activities affected the hormones that we thought might be involved. Bingeing on chocolate ice cream helped! High stress made it worse. Alia kept records of the relative intensity of each episode—something that wasn’t that easy to do, because in the midst of an episode she literally couldn’t multiply two times three! It was a really intense time for her, trying things, keeping track, getting her hopes up, having it not work out.

Her D-MER was so clearly tied to her milk releasing that at first we figured oxytocin had to be involved. We learned about other hormones like vasopressin and dopamine, and we looked at familiar ones like prolactin. When we looked at how quickly it came and went, and what made it better and worse, by far the best fit was dopamine. When we looked back at times when she’d felt something very similar but wasn’t lactating, dopamine fit. When she tried a prescription drug that increases dopamine levels, her D-MER got better.

We learned about other hormones like vasopressin and dopamine, and we looked at familiar ones like prolactin. When we looked at how quickly it came and went, and what made it better and worse, by far the best fit was dopamine. When we looked back at times when she’d felt something very similar but wasn’t lactating, dopamine fit. When she tried a prescription drug that increases dopamine levels, her D-MER got better.

What help is available for mothers suffering from D-MER?

At the moment, we think that anything that increases dopamine levels without causing them to crash later (which caffeine seemed to do) would help. Some things are clearly non-starters. You can’t live on chocolate ice cream or pseudoephedrine, and smoking is obviously out. Alia has listed a lot of other choices on her website, from simple things like getting more exercise and more sleep to an herbal remedy to prescriptions that you can talk over with a physician. She loves to hear from and support women with D-MER, and she recently put her information in book form. Before the Letdown: Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex and the Breastfeeding Mother came out on Amazon last year.

Before the Letdown: Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex and the Breastfeeding Mother came out on Amazon last year.

Is the condition curable?

We haven’t found anything that stops it so that it never comes back, except time. Most women find that it gradually gets better over time and eventually just goes away. Unfortunately, the worse it is early on, the longer it seems to go on. For some, it doesn’t go away completely until weaning. Happily, almost everyone Alia talked with found that what helped as much as anything—and was usually enough in itself—was just knowing they weren’t crazy, they weren’t alone, and it wasn’t going to hurt them or their baby.

What do the researchers say?

For a long time, we were it. One D-MER mother and one LLL Leader/IBCLC, and the paper we’d written. Gradually, though, as breastfeeding helpers have realized what they’re seeing and how it differs from postpartum depression, there’s been a real increase in anecdotal information, case studies, and serious research interest (see below), the list of which can be seen referenced below.

Here’s what we think happens, and what we still can’t confirm.: when a milk release is triggered, the oxytocin level shoots up and, separately but in response to the same milk release trigger, dopamine makes an abrupt but brief drop. Since dopamine is a gatekeeper that blocks release of the milk-making hormone prolactin, we know dopamine has to drop to allow prolactin to rise. But we couldn’t find anything to say when that drop occurs or how abrupt or brief it is. Who knows—maybe it isn’t in the literature yet and D-MER mothers will be the ones to provide the answer!

Where do we go from here?

We really hope that this catches the eye of people who are already doing research on dopamine. Since dopamine changes happen within the brain, they can’t really be measured in humans; researchers tend to study something like rats. But here’s a group of humans who can feel a particular change instantly, any time a milk release is triggered, and describe it in detail afterwards. Some researchers have suggested that dopamine is like a keyboard that can be “played” to achieve anything from desire to disgust. Well, D-MER mothers can tell them exactly where they are on the keyboard. I was fascinated that some of the mothers who wrote to Alia described feelings of “homesickness.” That’s a very, very specific emotion that sounds to me like the knife edge between pleasure and pain—a painful recollection of something pleasant. How cool that information would be for the right researcher!

Some researchers have suggested that dopamine is like a keyboard that can be “played” to achieve anything from desire to disgust. Well, D-MER mothers can tell them exactly where they are on the keyboard. I was fascinated that some of the mothers who wrote to Alia described feelings of “homesickness.” That’s a very, very specific emotion that sounds to me like the knife edge between pleasure and pain—a painful recollection of something pleasant. How cool that information would be for the right researcher!

Among the people we talked to were menopausal women who felt dysphoria with hot flashes and a woman who felt Restless Leg Syndrome with hot flashes. RLS is treated with dopamine. What does all this have to say about the hormones of hot flashes? One man even said that, as far back as he can remember, he’s occasionally felt dysphoria in the midst of anticipating something pleasurable. If he’s thinking about a trip, suddenly he can think only about losing the tickets. It sounds a whole lot like D-MER. So I think this could go in a lot of directions. I think things similar to D-MER are out there, and it’s just never occurred to those who experience it that it could have any significance.

So I think this could go in a lot of directions. I think things similar to D-MER are out there, and it’s just never occurred to those who experience it that it could have any significance.

How can D-MER mothers learn more and share their experiences?

It’s important that mothers with D-MER continually feel that they are not alone. In addition to www.D-MER.org there is a Facebook group that is active with posts and discussions called Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex (D-MER) Support Group from d-mer.org. There’s just nothing like the support of other mothers who’ve been there, and the forums are a chance for mothers to “pay it forward” by sharing their D-MER experiences.

Cox S. A case of dysphoric milk ejection reflex (D-MER). Breastfeeding Review, 2010; 18(1).

Heise AM. Before The Letdown: Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex and the Breastfeeding Mother. 2017; independently published.

Pettersson J, Packalén A. Experiences and knowledge on Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex (D-MER) – A study by means of a mixed method design approach. Karolinska Institutet doctoral education program, April 2018.

Karolinska Institutet doctoral education program, April 2018.

Ureño TL, Buchheit TL, Hopkinson SG, Berry-Cabán CS. Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex: A Case Series. Breastfeeding Medicine, 2018; 13(1): 85-88. doi:10.1089/bfm.2017.0086

Uvnas-Moberg K, Kendall-Tackett K. The Mystery of D-MER: What Can Hormonal Research Tell Us About Dysphoric Milk-Ejection Reflex? Clinical Lactation, 2018; 9(1): 23-29. doi:10.1891/2158-0782.9.1.23.

Watkinson M, Murray C, Simpson J. Maternal experiences of embodied emotional sensations during breast feeding: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Midwifery, 2016; 36, 53-60. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2016.02.019.

This article is an updated version of one first published by Breastfeeding Today in 2011.

7 reasons why people should avoid cow's milk

February 15, 2017

If you still doubt that milk really has a bad effect on the human body, then the scientifically proven studies below should dispel all doubts. Since the slogan "meat and milk makes you sick" clearly does not contribute to the successful sales of these products, manufacturers of meat and dairy products make every effort to ensure that such information does not reach the consumer. All sorts of marketing strategies try to make us believe that milk is some kind of magical drink that keeps teeth, bones and skin healthy, when in fact they do just the opposite. Cow's milk is only good for calves, which are cruelly left without mother's milk these days.

Since the slogan "meat and milk makes you sick" clearly does not contribute to the successful sales of these products, manufacturers of meat and dairy products make every effort to ensure that such information does not reach the consumer. All sorts of marketing strategies try to make us believe that milk is some kind of magical drink that keeps teeth, bones and skin healthy, when in fact they do just the opposite. Cow's milk is only good for calves, which are cruelly left without mother's milk these days.

Americans consume dairy products in huge quantities - an average of 272 kg per person per year. It is interesting to note that humanity has not always consumed dairy products (including cow's milk) - only over the past 7,500 years (and human existence has been around for 200,000 years).

NUTRITION EXPERTS, SCIENTISTS AND PHYSICIANS DO NOT RECOMMEND EATING DAIRY PRODUCTS BECAUSE THEY ARE ASSOCIATED WITH VARIOUS SERIOUS PRODUCTS.

In "Forks over Knives" Dr. Alona Pulde gives a thorough overview of dairy products

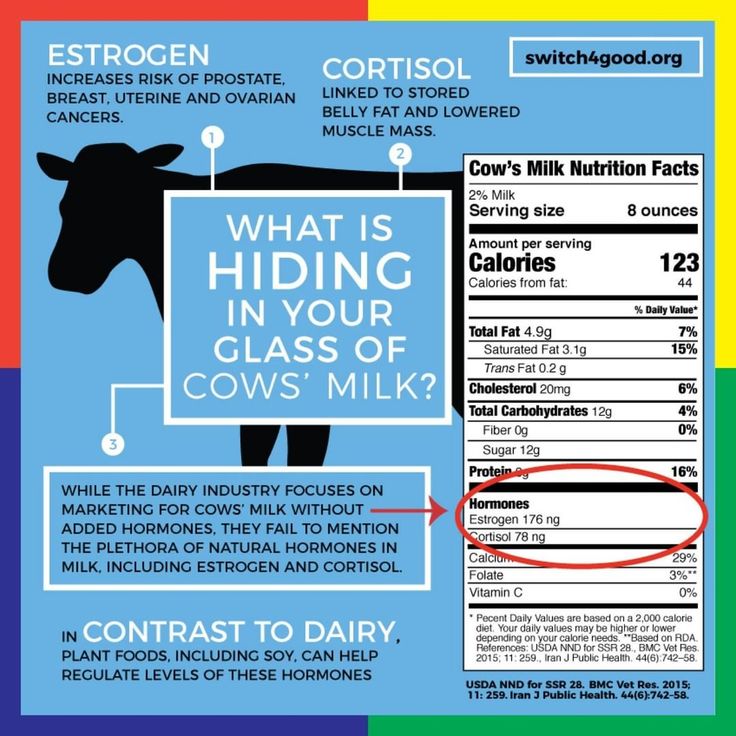

1. EVEN ORGANIC MILK CONTAINS HORMONES Dairy products contain a lot of female hormones. Store-bought cow's milk is high in estrogen and progesterone, which is a serious problem. This is mainly because cows are forced to produce milk all the time, even in the case of repeated production of offspring. These hormones are also found in dairy products labeled "organic" or "hormone-free" on their packages, because the cow's body produces them itself (even if she was not given additional hormones).

In the blood and urine of both adults and children, the amount of estradiol and progesterone increases in connection with the consumption of milk, and an increase in the amount of circulating estradiol in the blood is also associated with the use of dairy products. Studies have shown that men who drink milk metabolize the estrogen in milk, which significantly increases testosterone production.

Pediatricians are sounding the alarm about the level of estrogen in cow's milk, since excessively early puberty at puberty may be due to the consumption of milk.

Numerous scientific studies confirm that milk consumption may be one of the risk factors for hormone-dependent malignant diseases (including ovarian, uterine, breast, testicular and prostate cancer).

2. DAIRY CASEIN INCREASES THE RISK OF CANCER

Casein, which promotes cancer and its development, is the main protein found in dairy products. There are suggestions that keeping the development of cancer under control by eating a diet low in casein is more effective than avoiding carcinogens. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) is responsible for this connection, a hormone that promotes the reproduction and division of both normal and cancer cells. Dietary levels of IGF-1 are regulated, and consumption of animal protein (including casein in dairy products) increases blood levels of this cancer-causing hormone. It is for this reason that the consumption of casein contained in milk (and animal protein in general) is associated with the occurrence of cancer and its spread.

It is for this reason that the consumption of casein contained in milk (and animal protein in general) is associated with the occurrence of cancer and its spread.

3. HIGHER RISK OF TYPE I DIABETES AND MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

The human immune system protects the body from microbes and other harmful substances, but if it is not able to recognize and distinguish harmful cells and substances from normal cells and substances, from normal cells and substances it can start attacking our own body.

Such automatic attacks are caused by contact with foreign peptides (including fragments of animal protein found in milk), which are similar to the components of the human body. The immune system is confused and no longer recognizes its own tissues and begins to attack them.

Dairy products have been linked to all sorts of immune system disorders, from allergic reactions to autoimmune diseases. Of particular concern is the association with type I diabetes and multiple sclerosis. In the case of type I diabetes, i.e. in diabetes, the immune system attacks the pancreas, causing it to no longer be able to produce enough insulin to regulate the amount of glucose in the body.

In the case of type I diabetes, i.e. in diabetes, the immune system attacks the pancreas, causing it to no longer be able to produce enough insulin to regulate the amount of glucose in the body.

Numerous scientific studies support the association of cow's milk consumption with type 1 diabetes. One study found that cow's milk may contain a substance that causes this type of diabetes, and another study found that eating cow's milk increased the risk of type 1 diabetes by 1.5 times.

In multiple sclerosis, a person's immune system begins to attack their own nervous system. As with type 1 diabetes, those who drink cow's milk are at higher risk of developing multiple sclerosis.

4. EVEN PASTEURIZED MILK CONTAINS DANGEROUS MICRO-ORGANISMS

Due to the presence of microorganisms in milk and dairy products, they are one of the main spreaders of diseases through food. Even with modern hygiene requirements (including pasteurization and aging), serious incidents can occur. Salmonella, listeria and colibacilli are the most well-known bacteria present in dairy products that cause disease. Three people died in the US last year from contracting Listeria through Blue Belli ice cream, and the company was forced to recall the entire shipment.

Salmonella, listeria and colibacilli are the most well-known bacteria present in dairy products that cause disease. Three people died in the US last year from contracting Listeria through Blue Belli ice cream, and the company was forced to recall the entire shipment.

The US Veterinary and Food Department does not require that milk be completely sterile after pasteurization. Milk is brought to high temperatures in order to reduce the content of microorganisms in it.

5. DAIRY PRODUCTS O DUCTS CONTAIN HIGH PESTICIDES

Dairy products are also associated with organochlorine pesticides. Crop protection products pollute mainly water and agricultural land, however, due to the high fat content, dairy products tend to accumulate pesticides in large quantities. When testing products made from milk, they still contain pesticides that have long been banned. Unfortunately, there are still some organochlorine pesticides in the environment (such as DDT, which used to be quite widely used, but is now recognized as a carcinogen and banned) and they are present in food of animal origin, including dairy products.

In India, milk and other dairy products such as cheese and butter have been found to contain the most foodborne substances DDT and hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH). During a routine check, it was found that in milk produced in Italy on dairy farms in the Sacco Valley, the level of ß-HCH exceeded the permitted level by 20 times.

6. ANTIBIOTIC RESIDUES

Herd animals are the world's largest consumers of antibiotics. But the drugs are used mainly not for the treatment of diseases, but for the prevention of infections and for increasing the growth of animals (the latter is prohibited in the European Union). Despite the warnings of scientists that the excessive use of antibiotics causes resistance (immunity), and they try to minimize their content in milk at the legislative level, traces of antibiotics are still found in milk and dairy products. Their presence in milk is difficult to prevent and control, since milk from single cows and farms is mixed into a single mass, and the use of drugs on different dairy farms can be different. And although the antibiotic content in milk is low, its presence can lead to numerous problems, ranging from resistance to allergic reactions.

And although the antibiotic content in milk is low, its presence can lead to numerous problems, ranging from resistance to allergic reactions.

7. DAIRY PRODUCTS CAUSE BRITTLE BONES

It may seem surprising, but milk does not really have a positive effect on bones. A lot of research has been done that refutes the outdated idea that milk makes bones strong. On the contrary, drinking milk increases the risk of bone fragility.

This has its reasons. For example, milk contains a large amount of calcium, which removes vitamin D from the body and thereby disrupts homeostasis (self-regulation of the system) in the bones. In addition, the animal protein contained in milk can cause acidosis (a shift in the acid-base balance towards acidity), and in order to neutralize the increased acidity, the body compensates for this by removing calcium from the bones. If such a process occurs for a long time, it can have irreversible consequences for the condition of the bones.

And although other factors (such as physical activity) also affect bone health, it should be noted that in the United States, where milk is consumed quite a lot, hip fractures occur more often than anywhere else in the world. But in Japan and Peru, where only 300 milligrams of calcium a day is consumed (less than one-third of the recommended amount for adults in the US), bone fractures are rare.

Fortunately, calcium is abundant in plant foods, including green leafy vegetables, legumes, and seeds, and is more easily absorbed by the body than the calcium found in dairy products.

Sources: "Forks over Knives" and iNourishgently.com

Is milk poison? Hormones and lactose, an analysis of popular nonsense about milk

Surely you have heard somewhere from the corner of your ear that milk is a poison, because it is full of hormones, and in general, adults do not digest dairy products.

Generally speaking, this is partly true. This is not about milk as such, but about milk sugar, that is, lactose. And about the lack of lactase - an enzyme that helps us digest lactose.

There is almost no sugar in human mother's milk, but there is quite a lot in cow's milk. Therefore, in distant prehistoric times, by nature, a person really could not break down lactose. He couldn't and suffered a lot from it, until about 5 thousand years ago one or, at most, a few lucky people in the north of Europe did not have a gene for lactose tolerance.

There is even such an anthropological theory, according to which the flourishing of cattle breeding, and after it civilization, is the result of just such a beneficial mutation, thanks to which a person began to digest milk sugar. Because one cow allows the whole family to survive the cruel winter, while if the animal is simply slaughtered and eaten, the meat will end very quickly.

Either way, this beneficial gene is more common today than at any other time in human history. True, it is distributed unevenly: if in the north of Europe it occurs on average in 90% of the population in different countries, then in the south of Europe and in the Balkans it is already only in half of the population or even less. Therefore, lactase deficiency is also called the "Mediterranean syndrome". For example, only 30 percent of Sicilians and residents of southern France are its happy owners, and among Asians even less - in some populations, adults, like our ancestors, are not at all able to break down milk sugar.

True, it is distributed unevenly: if in the north of Europe it occurs on average in 90% of the population in different countries, then in the south of Europe and in the Balkans it is already only in half of the population or even less. Therefore, lactase deficiency is also called the "Mediterranean syndrome". For example, only 30 percent of Sicilians and residents of southern France are its happy owners, and among Asians even less - in some populations, adults, like our ancestors, are not at all able to break down milk sugar.

Yes, lactase deficiency can also increase with age. In the same population in early childhood, it is less common than among adults.

In general, nothing catastrophic usually occurs with lactase deficiency. It’s just that we don’t absorb milk sugar, but the bacteria that live in our intestines digest it perfectly. As a result, there is some imbalance with all the ensuing consequences - nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain and other signs of disorder. But this is in the most extreme cases. Usually everything is limited to flatulence and unpleasant sensations that make a person avoid fresh milk.

Usually everything is limited to flatulence and unpleasant sensations that make a person avoid fresh milk.

By the way, an important nuance: all this applies only to products made from fresh milk. Cottage cheese, yoghurts and cheeses and other fermented milk products are quite safe even for those who do not have a lucky enzyme. Lactose in these products was eaten by special microorganisms long before us.

And for dessert - about the myth about the notorious hormones in milk that disrupt the human endocrine system.

Indeed, there is growth hormone in milk, which is contained there naturally - simply because there are hormones in milk. Even industrial milk may indeed contain bovin, a growth hormone that is actually injected into cows so that they give more milk.

However, growth hormone is a peptide hormone. Without delving into biochemical subtleties, a peptide is a simple protein molecule. And proteins, as we know, are completely destroyed in the stomach. There are no such peptide hormones that would enter the stomach with food, and from there would enter the blood unharmed. It's just not possible. If scientists could figure out a way to deliver whole peptides through the stomach into the bloodstream, we would have had insulin pills for diabetics a long time ago. And scientists are really struggling to create them, and maybe by 2020 something like this will appear, at least we are promised so.

There are no such peptide hormones that would enter the stomach with food, and from there would enter the blood unharmed. It's just not possible. If scientists could figure out a way to deliver whole peptides through the stomach into the bloodstream, we would have had insulin pills for diabetics a long time ago. And scientists are really struggling to create them, and maybe by 2020 something like this will appear, at least we are promised so.

However, since today all peptides, including hormones, are destroyed in the stomach, milk that has a small amount of bovine growth hormone or bovin is ABSOLUTELY. HARMFUL. FOR HUMAN - and approved by all possible authorities around the world.

Only sellers of organic milk, which does not contain hormones, can convince you otherwise. And there is nothing terrible about organic milk, except perhaps its price. However, remember that even in the most natural whole milk from a cow, there are also hormones. Just because it's milk, damn it.