Medical induction of labour

Labor induction - Mayo Clinic

Overview

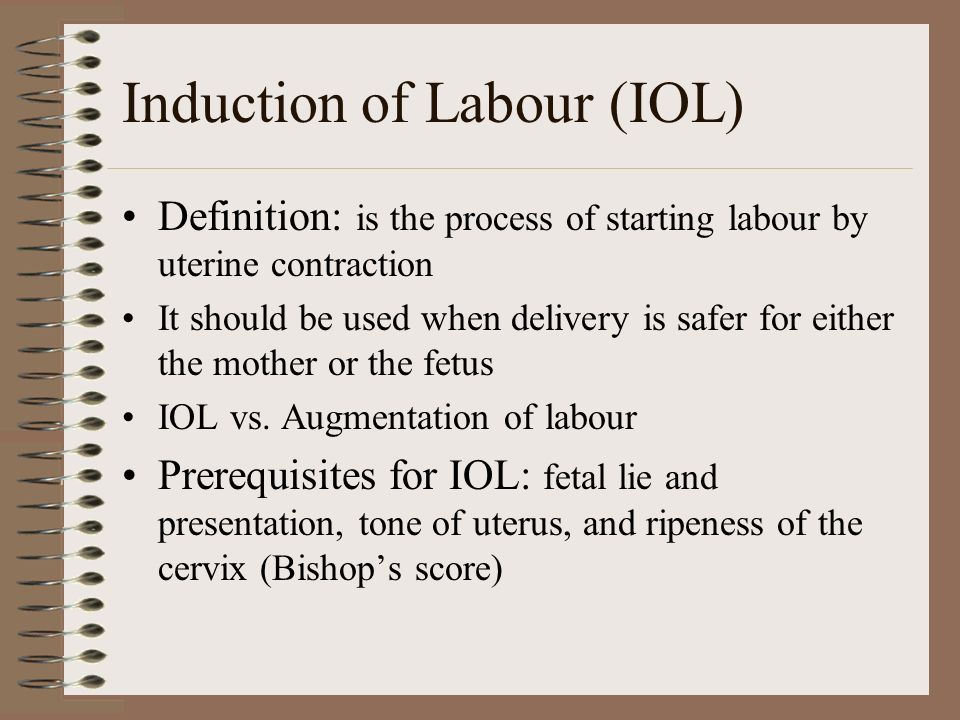

Labor induction — also known as inducing labor — is prompting the uterus to contract during pregnancy before labor begins on its own for a vaginal birth.

A health care provider might recommend inducing labor for various reasons, primarily when there's concern for the mother's or baby's health. An important factor in predicting whether an induction will succeed is how soft and expanded the cervix is (cervical ripening). The gestational age of the baby as confirmed by early, regular ultrasounds also is important.

If a health care provider recommends labor induction, it's typically because the benefits outweigh the risks. If you're pregnant, understanding why and how labor induction is done can help you prepare.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

To determine if labor induction is necessary, a health care provider will likely evaluate several factors. These include the mother's health and the status of the cervix. They also include the baby's health, gestational age, weight, size and position in the uterus. Reasons to induce labor include:

- Nearing 1 to 2 weeks beyond the due date without labor starting (postterm pregnancy).

- When labor doesn't begin after the water breaks (prelabor rupture of membranes).

- An infection in the uterus (chorioamnionitis).

- When the baby's estimated weight is less than the 10th percentile for gestational age (fetal growth restriction).

- When there's not enough amniotic fluid surrounding the baby (oligohydramnios).

- Possibly when diabetes develops during pregnancy (gestational diabetes), or diabetes exists before pregnancy.

- Developing high blood pressure in combination with signs of damage to another organ system (preeclampsia) during pregnancy. Or having high blood pressure before pregnancy, developing it before 20 weeks of pregnancy (chronic high blood pressure) or developing the condition after 20 weeks of pregnancy (gestational hypertension).

- When the placenta peels away from the inner wall of the uterus before delivery — either partially or completely (placental abruption).

- Having certain medical conditions. These include heart, lung or kidney disease and obesity.

Elective labor induction is the starting of labor for convenience when there's no medical need. It can be useful for women who live far from the hospital or birthing center or who have a history of fast deliveries.

A scheduled induction might help avoid delivery without help. In such cases, a health care provider will confirm that the baby's gestational age is at least 39 weeks or older before induction to reduce the risk of health problems for the baby.

As a result of recent studies, women with low-risk pregnancies are being offered labor induction at 39 to 40 weeks. Research shows that inducing labor at this time reduces several risks, including having a stillbirth, having a large baby and developing high blood pressure as the pregnancy goes on. It's important that women and their providers share in decisions to induce labor at 39 to 40 weeks.

It's important that women and their providers share in decisions to induce labor at 39 to 40 weeks.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which

information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with

other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Risks

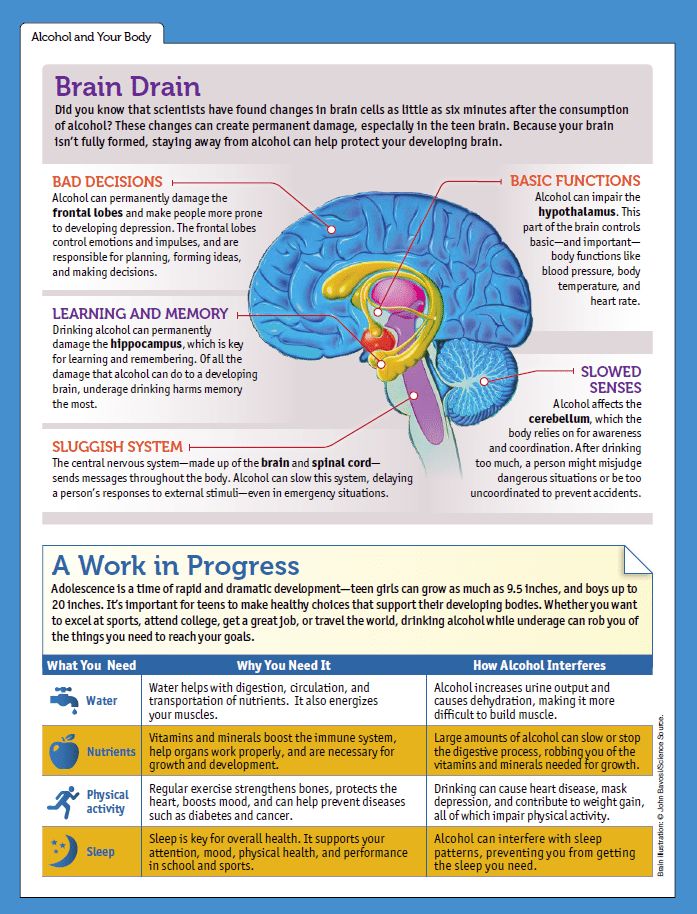

Uterine incisions used during C-sections

Uterine incisions used during C-sections

A C-section includes an abdominal incision and a uterine incision. After the abdominal incision, the health care provider will make an incision in the uterus. Low transverse incisions are the most common (top left).

Labor induction carries various risks, including:

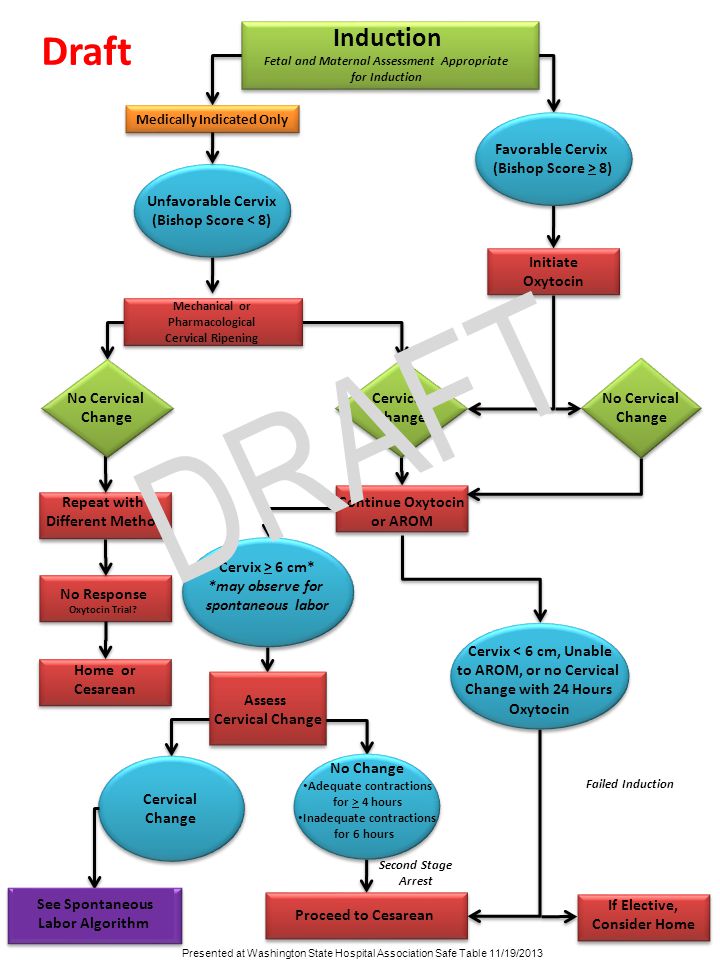

- Failed induction. An induction might be considered failed if the methods used don't result in a vaginal delivery after 24 or more hours. In such cases, a C-section might be necessary.

- Low fetal heart rate. The medications used to induce labor — oxytocin or a prostaglandin — might cause the uterus to contract too much, which can lessen the baby's oxygen supply and lower the baby's heart rate.

- Infection. Some methods of labor induction, such as rupturing the membranes, might increase the risk of infection for both mother and baby. The longer the time between membrane rupture and labor, the higher the risk of an infection.

-

Uterine rupture. This is a rare but serious complication in which the uterus tears along the scar line from a prior C-section or major uterine surgery. Rarely, uterine rupture can also occur in women who have not had previous uterine surgery.

An emergency C-section is needed to prevent life-threatening complications. The uterus might need to be removed.

- Bleeding after delivery. Labor induction increases the risk that the uterine muscles won't properly contract after giving birth, which can lead to serious bleeding after delivery.

Labor induction isn't for everyone. It might not be an option if:

- You've had a C-section with a classical incision or major uterine surgery

- The placenta is blocking the cervix (placenta previa)

- Your baby is lying buttocks first (breech) or sideways (transverse lie)

- You have an active genital herpes infection

- The umbilical cord slips into the vagina before delivery (umbilical cord prolapse)

If you have had a C-section and have labor induced, your health care provider is likely to avoid certain medications to reduce the risk of uterine rupture.

How you prepare

Labor induction is typically done in a hospital or birthing center. That's because mother and baby can be monitored there, and labor and delivery services are readily available.

What you can expect

During the procedure

There are various ways of inducing labor. Depending on the circumstances, the health care provider might use one of the following ways or a combination of them. The provider might:

-

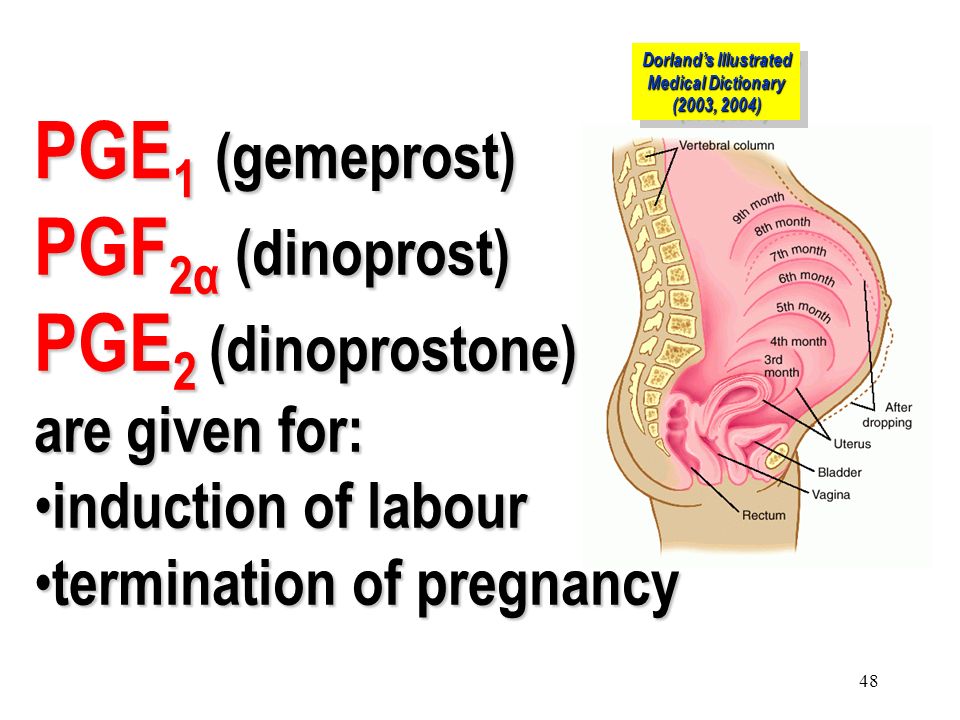

Ripen the cervix. Sometimes prostaglandins, versions of chemicals the body naturally produces, are placed inside the vagina or taken by mouth to thin or soften (ripen) the cervix. After prostaglandin use, the contractions and the baby's heart rate are monitored.

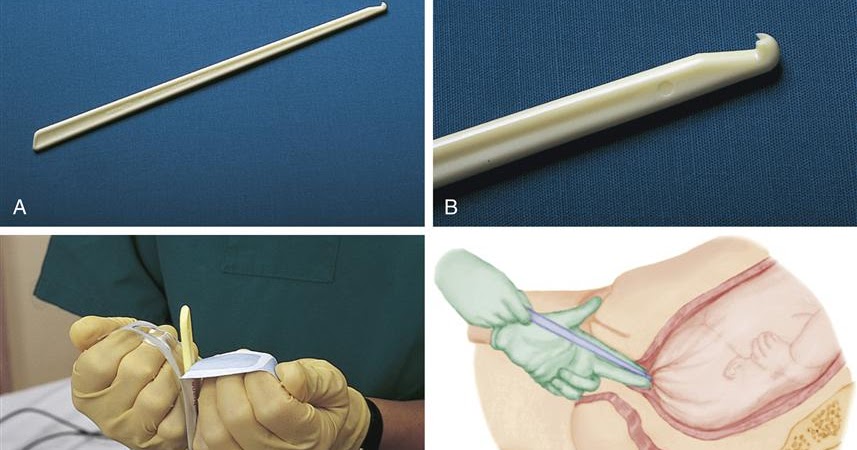

In other cases, a small tube (catheter) with an inflatable balloon on the end is inserted into the cervix. Filling the balloon with saline and resting it against the inside of the cervix helps ripen the cervix.

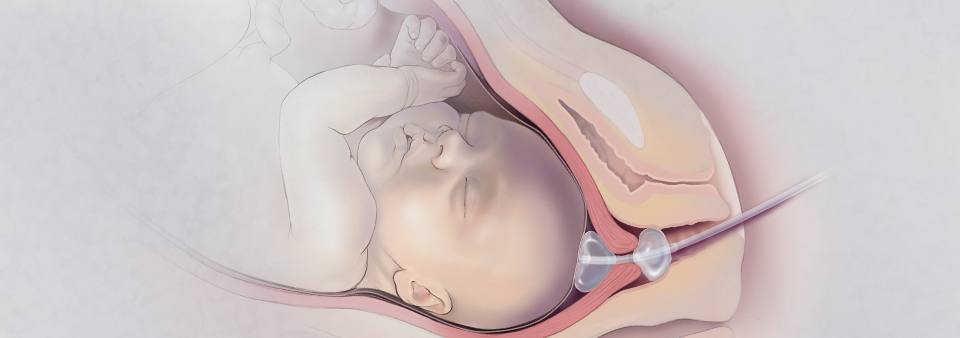

- Sweep the membranes of the amniotic sac.

With this technique, also known as stripping the membranes, the health care provider sweeps a gloved finger over the covering of the amniotic sac near the fetus. This separates the sac from the cervix and the lower uterine wall, which might help start labor.

With this technique, also known as stripping the membranes, the health care provider sweeps a gloved finger over the covering of the amniotic sac near the fetus. This separates the sac from the cervix and the lower uterine wall, which might help start labor. -

Rupture the amniotic sac. With this technique, also known as an amniotomy, the health care provider makes a small opening in the amniotic sac. The hole causes the water to break, which might help labor go forward.

An amniotomy is done only if the cervix is partially dilated and thinned, and the baby's head is deep in the pelvis. The baby's heart rate is monitored before and after the procedure.

- Inject a medication into a vein. In the hospital, a health care provider might inject a version of oxytocin (Pitocin) — a hormone that causes the uterus to contract — into a vein. Oxytocin is more effective at speeding up labor that has already begun than it is as at cervical ripening.

The provider monitors contractions and the baby's heart rate.

The provider monitors contractions and the baby's heart rate.

How long it takes for labor to start depends on how ripe the cervix is when the induction starts, the induction techniques used and how the body responds to them. It can take minutes to hours.

After the procedure

In most cases, labor induction leads to a vaginal birth. A failed induction, one in which the procedure doesn't lead to a vaginal birth, might require another induction or a C-section.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Products & Services

Medical reasons for inducing labor

Inducing labor (also called labor induction) is when your provider gives you medicine or breaks your water to make labor start.

Your provider may recommend inducing labor if your health or your baby’s health is at risk or if you’re 2 weeks or more past your due date.

Inducing labor should only be for medical reasons. If your pregnancy is healthy, it’s best to wait for labor to start on its own.

If your provider recommends inducing labor, ask about waiting until at least 39 weeks to be induced so your baby has time to develop in the womb.

What is inducing labor?

Inducing labor (also called labor induction) is when your health care provider gives you medicine or uses other methods, like breaking your water (amniotic sac), to make your labor start. The amniotic sac (also called bag of waters) is the sac inside the uterus (womb) that holds your growing baby. The sac is filled with amniotic fluid. Contractions are when the muscles of your uterus get tight and then relax. Contractions help push your baby out of your uterus.

Your provider may recommend inducing labor if your health or your baby’s health is at risk or if you’re 2 weeks or more past your due date. For some women, inducing labor is the best way to keep mom and baby healthy. Inducing labor should be for medical reasons only.

If there are medical reasons to induce your labor, talk to your provider about waiting until at least 39 weeks of pregnancy. This gives your baby the time she needs to grow and develop before birth. Scheduling labor induction should be for medical reasons only.

This gives your baby the time she needs to grow and develop before birth. Scheduling labor induction should be for medical reasons only.

What are medical reasons for inducing labor?

Your provider may recommend inducing labor if:

- Your pregnancy lasts longer than 41 to 42 weeks. After 42 weeks, the placenta may not work as well as it did earlier in pregnancy. The placenta grows in your uterus (womb) and supplies your baby with food and oxygen through the umbilical cord.

- Your placenta is separating from your uterus (also called placental abruption) or you have an infection in your uterus.

- Your water breaks before labor begins. This is called premature rupture of membranes (also called PROM).

- You have health problems, like diabetes, high blood pressure or preeclampsia or problems with your heart, lungs or kidneys. Diabetes is when your body has too much sugar (called glucose) in your blood. This can damage organs in your body, including blood vessels, nerves, eyes and kidneys.

High blood pressure is when the force of blood against the walls of the blood vessels is too high and stresses your heart. Preeclampsia is a serious blood pressure condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or after giving birth (called postpartum preeclampsia).

High blood pressure is when the force of blood against the walls of the blood vessels is too high and stresses your heart. Preeclampsia is a serious blood pressure condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or after giving birth (called postpartum preeclampsia). - Your baby has a stopped growing. Or your baby has oligohydramnios. This means your baby doesn’t have enough amniotic fluid.

- You have Rh disease and it causes problems with your baby’s blood.

What are the risks of scheduling labor induction for non-medical reasons?

Scheduling labor induction may cause problems for you and your baby because your due date may not be exactly right. Sometimes it’s hard to know exactly when you got pregnant. If you schedule labor induction and your due date is off by a week or 2, your baby may be born too early. Babies born early (called premature babies) may have more health problems at birth and later in life than babies born on time. This is why it’s important to wait until at least 39 weeks to induce labor.

This is why it’s important to wait until at least 39 weeks to induce labor.

If your pregnancy is healthy, it’s best to let labor begin on its own. If your provider talks to you about inducing labor, ask if you can wait until at least 39 weeks to be induced. This gives your baby’s lungs and brain all the time they need to fully grow and develop before he’s born.

If there are problems with your pregnancy or your baby’s health, you may need to have your baby earlier than 39 weeks. In these cases, your provider may recommend an early birth because the benefits outweigh the risks. Inducing labor before 39 weeks of pregnancy is recommended only if there are health problems that affect you and your baby.

If your provider recommends inducing labor, ask these questions:

- Why do we need to induce my labor?

- Is there a problem with my health or the health of my baby that may make inducing labor necessary before 39 weeks? Can I wait to have my baby closer to 39 weeks?

- How will you induce my labor?

- What can I expect when you induce labor?

- Will inducing labor increase the chance that I'll need to have a c-section?

- What are my options for pain medicine?

Last reviewed: September, 2018

See also: 39 weeks infographic

Oral misoprostol for induction of labor

Oral misoprostol is effective for inducing (starting) labor. This (oral misoprostol) is more effective than placebo, is as effective as vaginal misoprostol, and results in fewer caesarean sections than vaginal dinoprostone or oxytocin. However, there is still not enough data from randomized controlled trials to determine the best dose of misoprostol to guarantee safety.

This (oral misoprostol) is more effective than placebo, is as effective as vaginal misoprostol, and results in fewer caesarean sections than vaginal dinoprostone or oxytocin. However, there is still not enough data from randomized controlled trials to determine the best dose of misoprostol to guarantee safety.

Induction of labor at the end of pregnancy is used to prevent complications when the pregnant woman or her unborn child is in danger (there are risk factors). Causes of induction of labor include postnatal pregnancy, premature rupture of membranes, and high blood pressure. Prostaglandins are hormones that are naturally present in the uterus; they soften the cervix and stimulate labor contractions. An artificial analogue of prostaglandin E2, dinoprostone, can be administered vaginally to induce (stimulate) labor, but is not stable at room temperature and is expensive. Oral misoprostol is a cheap and heat-resistant synthetic analogue of prostaglandin E1; it was originally developed to treat stomach ulcers.

This review of 76 randomized controlled trials (14,412 women) found that oral misoprostol appears to be at least as effective as other current methods of labor induction. Nine trials (1,282 women) showed that oral misoprostol was equivalent to an intravenous infusion of oxytocin, but resulted in significantly fewer caesarean sections. `The high incidence of meconium staining of amniotic fluid has not been associated with any adverse effect on the unborn child, and may be a direct effect of misoprostol on the infant's intestines. This effect was also seen when compared with vaginal misoprostol, but was less pronounced. Thirty-seven trials (6,417 women) comparing oral and vaginal misoprostol found them to be equally effective. However, those who took oral misoprostol had better neonates at birth and had fewer postpartum haemorrhages.

In twelve (12) trials (3,859 women) comparing oral misoprostol with vaginal dinoprostone, women taking misoprostol were less likely to need a caesarean section (21% vs. 26% of women), although induction of labor could generally be slower. The most common dose of misoprostol in these studies was 20 mcg. The frequency of hyperstimulation and meconium staining was similar with misoprostol and dinoprostone.

26% of women), although induction of labor could generally be slower. The most common dose of misoprostol in these studies was 20 mcg. The frequency of hyperstimulation and meconium staining was similar with misoprostol and dinoprostone.

Nine trials comparing oral misoprostol with placebo (1,109women) showed that oral misoprostol was more effective than placebo for induction of labor, with lower rates of caesarean sections and infant admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit. The quality of the evidence for some comparisons was very strong (eg, oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol), but the strength of the recommendation was weaker for other comparisons.

Translation notes:

Translation: Ziganshina Liliya Evgenievna. Editing: Yudina Ekaterina Viktorovna. Project coordination for translation into Russian: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia (branch of the Northern Cochrane Center on the basis of Kazan Federal University). For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: lezign@gmail. com

com

Low-dose oral misoprostol to induce labor

We reviewed evidence from randomized controlled trials to investigate whether low-dose oral misoprostol is effective in inducing labor in women in the third trimester of pregnancy with a live birth. We compared the use of misoprostol with other commonly used methods of labor induction.

What is the problem?

Induction of labor, or induction, is often used during pregnancy. Causes may be high blood pressure in the mother during pregnancy or a post-term pregnancy. Misoprostol is a type of prostaglandin that can be taken orally in low doses to induce labor. Prostaglandins are hormone-like compounds that are produced by the body to perform various functions (including the natural onset of labor). Unlike other prostaglandins such as vaginal dinoprostone, misoprostol does not need to be refrigerated. The tablet is convenient for the mother, and low-dose tablets (25 mcg) are now available.

Why is this important?

A good method of induction leads to a safe birth for mother and baby. It is effective, leads to a relatively low number of caesarean sections, has few side effects, and is very acceptable to mothers. Some methods of labor induction may cause more caesarean sections because they are not effective in initiating labor; other methods may result in more caesarean sections because they cause contractions that are too strong (hyperstimulation), resulting in distress for the baby (changes in the fetal heart rate).

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence up to 14 February 2021 and identified 61 studies involving 20,026 women for inclusion in this review. Not all studies were of high quality.

Immediate initiation of oral misoprostol may have the same impact on caesarean section rates (4 studies, 594 women; low-certainty evidence) as no treatment (misoprostol) within 12-24 hours followed by initiation of oxytocin, in while the effect of misoprostol on uterine hyperstimulation with changes in fetal heart rate is uncertain (3 studies, 495 women; very low quality evidence). All women in these trials had ruptured membranes.

All women in these trials had ruptured membranes.

Thirteen studies (9676 women) compared oral misoprostol with vaginal dinoprostone. Misoprostol probably reduced the risk of caesarean section (moderate-certainty evidence). When studies were stratified by the starting dose of misoprostol, there was evidence that the use of misoprostol at a dose of 10 mcg to 25 mcg may be effective in reducing the risk of caesarean section (9studies, 8652 women), while the higher dose of 50 mcg may not reduce the risk (4 studies, 1024 women). The difference between misoprostol and dinoprostone in the rate of vaginal delivery within 24 hours may be very small or non-existent (10 studies, 8983 women; low-certainty evidence), but there may be fewer cases of hyperstimulation with a change in fetal heart rate with oral misoprostol (11 studies, 9084 women; low-certainty evidence).

Thirty-three studies (6110 women) compared oral misoprostol with vaginal misoprostol. Oral use may have resulted in fewer vaginal deliveries within 24 hours (16 studies, 3451 women; low-certainty evidence). Oral administration may have caused less hyperstimulation with changes in fetal heart rate (25 certainty, 4857 women; low-certainty evidence), especially at doses of 10 mcg to 25 mcg. Overall, there were no clear differences in the number of caesarean sections (32 studies, 5914 women; low-certainty evidence), but oral administration likely led to a reduction in caesarean sections due to concerns that the baby was in distress (24 studies, 4775 women).

Oral administration may have caused less hyperstimulation with changes in fetal heart rate (25 certainty, 4857 women; low-certainty evidence), especially at doses of 10 mcg to 25 mcg. Overall, there were no clear differences in the number of caesarean sections (32 studies, 5914 women; low-certainty evidence), but oral administration likely led to a reduction in caesarean sections due to concerns that the baby was in distress (24 studies, 4775 women).

When oral misoprostol was compared with oxytocin for induction, misoprostol use probably resulted in fewer caesarean sections (6 studies, 737 women). We found no clear difference in cases of vaginal delivery within 24 hours (3 studies, 466 women; moderate-certainty evidence) or hyperstimulation with changes in fetal heart rate (3 studies, 331 women; very-low-certainty evidence).

Oral misoprostol was compared with the use of a balloon catheter inserted into the lumen of the cervix for mechanical induction of labor. The number of vaginal deliveries within 24 hours may have increased with misoprostol (4 studies, 1044 women; low-certainty evidence). Misoprostol probably reduced the risk of caesarean section (6 studies, 2993 women; moderate-certainty evidence), while the risk of fetal heart rate hyperstimulation did not change (4 studies, 1044 women; low-certainty evidence).

Misoprostol probably reduced the risk of caesarean section (6 studies, 2993 women; moderate-certainty evidence), while the risk of fetal heart rate hyperstimulation did not change (4 studies, 1044 women; low-certainty evidence).

Three small studies examined different doses and timing of oral misoprostol. The certainty of the results of these studies was either low or very low, so we cannot draw any meaningful conclusions from these data.

What does this mean?

Low-dose oral misoprostol (50 µg or less) for labor induction likely results in fewer caesarean sections and therefore more vaginal births than dinoprostone (intravaginally), oxytocin, and transcervical Foley catheters . The frequency of hyperstimulation with changes in fetal heart rate was comparable when using these methods. Oral misoprostol causes less hyperstimulation with changes in fetal heart activity compared to vaginal misoprostol.

More research is needed to determine the most effective misoprostol regimen for labor induction, but so far the results of this review support oral rather than vaginal use and suggest that initiation of oral misoprostol at doses of 25 mcg or less may be safe and effective.