How was the one child policy implemented in china

one-child policy | Definition, Start Date, Effects, & Facts

Top Questions

What is the one-child policy?

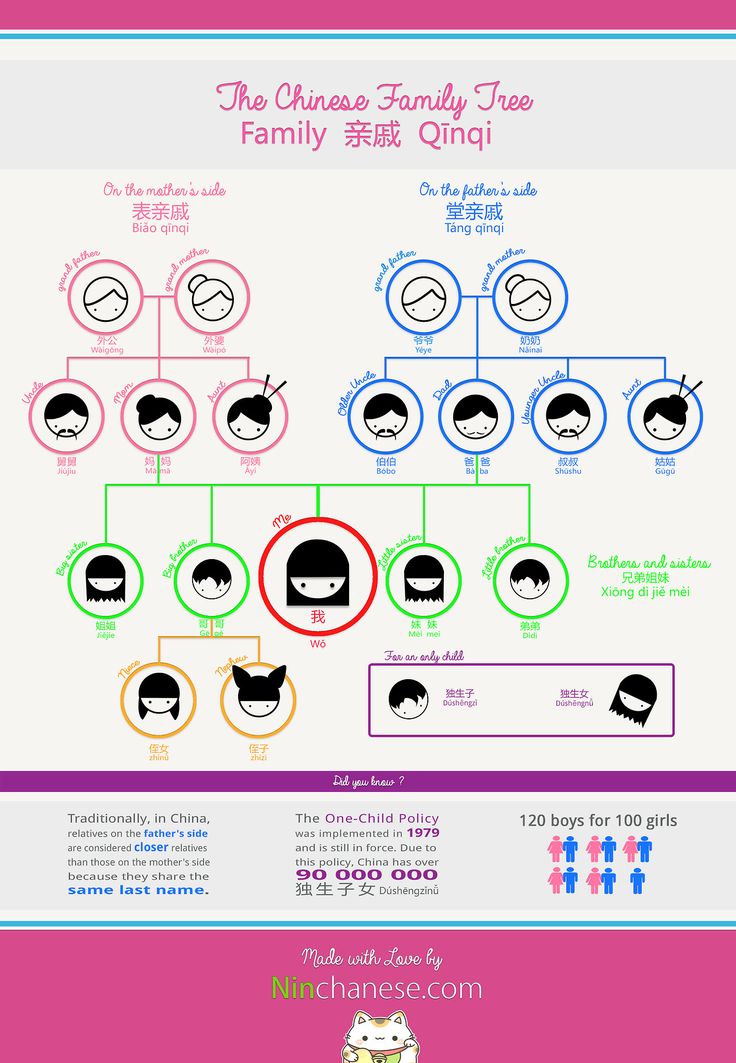

The one-child policy was a program in China that limited most Chinese families to one child each. It was implemented nationwide by the Chinese government in 1980, and it ended in 2016. The policy was enacted to address the growth rate of the country’s population, which the government viewed as being too rapid. It was enforced by a variety of methods, including financial incentives for families in compliance, contraceptives, forced sterilizations, and forced abortions.

When was the one-child policy introduced?

September 25, 1980, is often cited as the official start of China’s one-child policy, although attempts to curb the number of children in a family existed prior to that. Birth control and family planning had been promoted from 1949. A voluntary program introduced in 1978 encouraged families to have only one or two children. In 1979 there was a push for families to limit themselves to one child, but that was not evenly enforced across China. The Chinese government issued a letter on September 25, 1980, that called for nationwide adherence to the one-child policy.

Why is the one-child policy controversial?

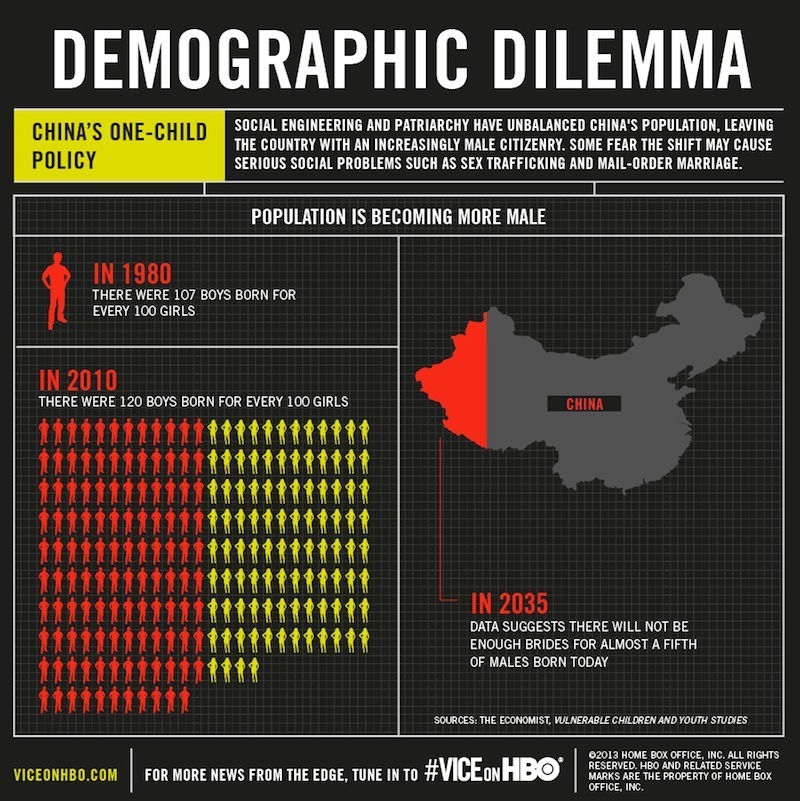

China’s one-child policy was controversial because it was a radical intervention by government in the reproductive lives of citizens, because of how it was enforced, and because of some of its consequences. Although some of the government’s enforcement methods were comparatively mild, such as providing contraceptives, millions of Chinese had to endure methods such as forced sterilizations and forced abortions. Long-term consequences of the policy included a substantially greater number of males than females in China and a shrinking workforce.

When did the one-child policy end?

The end of China’s one-child policy was announced in late 2015, and it formally ended in 2016. Beginning in 2016, the Chinese government allowed all families to have two children, and in 2021 all married couples were permitted to have as many as three children.

Beginning in 2016, the Chinese government allowed all families to have two children, and in 2021 all married couples were permitted to have as many as three children.

What are the consequences of the one-child policy?

There have been many consequences to China’s one-child policy. The country’s fertility rate and birth rate both decreased after 1980; the Chinese government estimated that some 400 million births had been prevented. Because sons were generally favoured over daughters, the sex ratio in China became skewed toward men, and there was a rise in the number of abortions of female fetuses along with an increase in the number of female babies killed or placed in orphanages.

After the one-child policy ended in 2016, China’s birth and fertility rates remained low, leaving the country with a population that was aging rapidly and a workforce that was shrinking. With data from China’s 2020 census highlighting an impending demographic and economic crisis, the Chinese government announced in 2021 that married couples would be allowed to have as many as three children.

one-child policy, official program initiated in the late 1970s and early ’80s by the central government of China, the purpose of which was to limit the great majority of family units in the country to one child each. The rationale for implementing the policy was to reduce the growth rate of China’s enormous population. It was announced in late 2015 that the program was to end in early 2016.

China began promoting the use of birth control and family planning with the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, though such efforts remained sporadic and voluntary until after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. By the late 1970s China’s population was rapidly approaching the one-billion mark, and the country’s new pragmatic leadership headed by Deng Xiaoping was beginning to give serious consideration to curbing what had become a rapid population growth rate. A voluntary program was announced in late 1978 that encouraged families to have no more than two children, one child being preferable. In 1979 demand grew for making the limit one child per family. However, that stricter requirement was then applied unevenly across the country among the provinces, and by 1980 the central government sought to standardize the one-child policy nationwide. On September 25, 1980, a public letter—published by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party to the party membership—called upon all to adhere to the one-child policy, and that date has often been cited as the policy’s “official” start date.

In 1979 demand grew for making the limit one child per family. However, that stricter requirement was then applied unevenly across the country among the provinces, and by 1980 the central government sought to standardize the one-child policy nationwide. On September 25, 1980, a public letter—published by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party to the party membership—called upon all to adhere to the one-child policy, and that date has often been cited as the policy’s “official” start date.

The program was intended to be applied universally, although exceptions were made—e.g., parents within some ethnic minority groups or those whose firstborn was handicapped were allowed to have more than one child. It was implemented more effectively in urban environments, where much of the population consisted of small nuclear families who were more willing to comply with the policy, than in rural areas, with their traditional agrarian extended families that resisted the one-child restriction. In addition, enforcement of the policy was somewhat uneven over time, generally being strongest in cities and more lenient in the countryside. Methods of enforcement included making various contraceptive methods widely available, offering financial incentives and preferential employment opportunities for those who complied, imposing sanctions (economic or otherwise) against those who violated the policy, and, at times (notably the early 1980s), invoking stronger measures such as forced abortions and sterilizations (the latter primarily of women).

In addition, enforcement of the policy was somewhat uneven over time, generally being strongest in cities and more lenient in the countryside. Methods of enforcement included making various contraceptive methods widely available, offering financial incentives and preferential employment opportunities for those who complied, imposing sanctions (economic or otherwise) against those who violated the policy, and, at times (notably the early 1980s), invoking stronger measures such as forced abortions and sterilizations (the latter primarily of women).

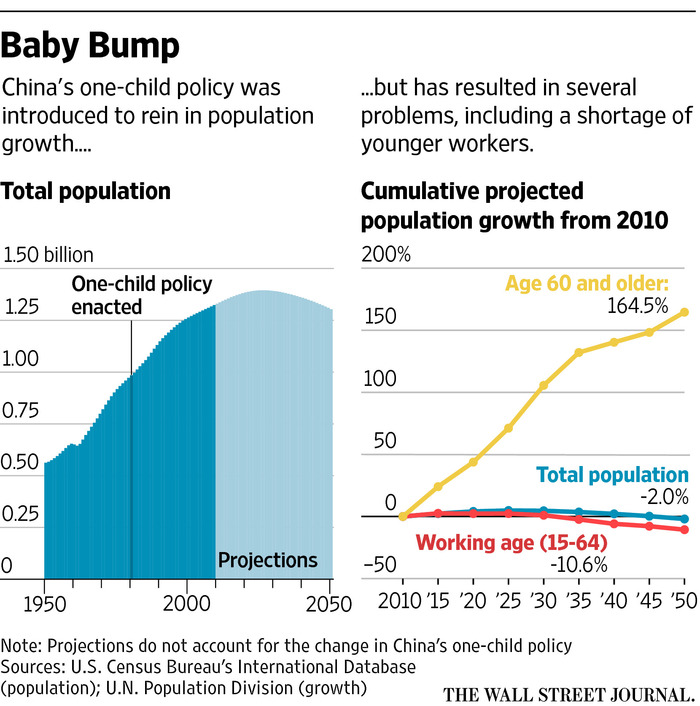

The result of the policy was a general reduction in China’s fertility and birth rates after 1980, with the fertility rate declining and dropping below two children per woman in the mid-1990s. Those gains were offset to some degree by a similar drop in the death rate and a rise in life expectancy, but China’s overall rate of natural increase declined.

Britannica Quiz

Exploring China: Fact or Fiction?

Does China have about half of the world’s population? Is China the most densely populated country on Earth? Test the density—or sparsity—of your knowledge of China in this quiz.

The end of China’s one-child policy

Content from the Brookings-Tsinghua Public Policy Center is now archived. Since October 1, 2020, Brookings has maintained a limited partnership with Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management that is intended to facilitate jointly organized dialogues, meetings, and/or events.

Starting on January 1, 2016, all Chinese couples are allowed to have two children. This marks the end of China’s one-child policy, which has restricted themajority of Chinese families to only one child for the last 35 years. The process of ending the one-child policy occurred in three steps over the past three years. It began inMarch 2013, when China merged the National Population and Family Planning Commission with the Ministry of Health to create a new National Health and Family Planning Commission. Eight months later, in November 2013, China announced a partial policy relaxation that allowed couples to have two children if one parent is an only child. Surprisingly, among the estimated more than 11 million couples who were eligible to have a second child under the new rule, only 1.69 million had applied as of August 2015, accounting for 15.4 percent of such couples. The third and final step took place in October 2015 to allow all couples to have two children in 2016.

Surprisingly, among the estimated more than 11 million couples who were eligible to have a second child under the new rule, only 1.69 million had applied as of August 2015, accounting for 15.4 percent of such couples. The third and final step took place in October 2015 to allow all couples to have two children in 2016.

With this latest change, the Chinese state has begun to withdrawits hand fromcontrolling couples’ reproductive decisions. An even more significant change that was announced as part of the third step is that couples are no longer required to seek approval from the government to have a child, whether the first or second, but only to register the birth afterward.While the announcement stops short of lifting all restrictions, and the official language still contains the rhetoric of “continuing the basic state policy of birth control,” it would appear to be only a matter of time before Chinese families will be free to choose when and how many children to have.

The one-child policy was designed in 1980 as a temporary measure to put a brake on China’s population growth and to facilitate economic growth under a planned economy that faced severe shortages of capital, natural resources, and consumer goods. However, the answer to China’s underdevelopment did not come from its extreme birth control measures, but from reform policies that loosened state control over the economy. China’s economic boom over the last few decades has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty, sent almost 100 million young men and women to college, and inspired generations of Chinese, both young and old, to purse their economic goals. As observed in many other countries and societies, socioeconomic and cultural transformations accelerated the pace of fertility decline. By the turn of the new century, China’s fertility was well below the replacement level, and China began to face the mounting pressures associated with continued low fertility. To continue the one-child policy within such a demographic context was clearly no longer defensible.

However, the answer to China’s underdevelopment did not come from its extreme birth control measures, but from reform policies that loosened state control over the economy. China’s economic boom over the last few decades has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty, sent almost 100 million young men and women to college, and inspired generations of Chinese, both young and old, to purse their economic goals. As observed in many other countries and societies, socioeconomic and cultural transformations accelerated the pace of fertility decline. By the turn of the new century, China’s fertility was well below the replacement level, and China began to face the mounting pressures associated with continued low fertility. To continue the one-child policy within such a demographic context was clearly no longer defensible.

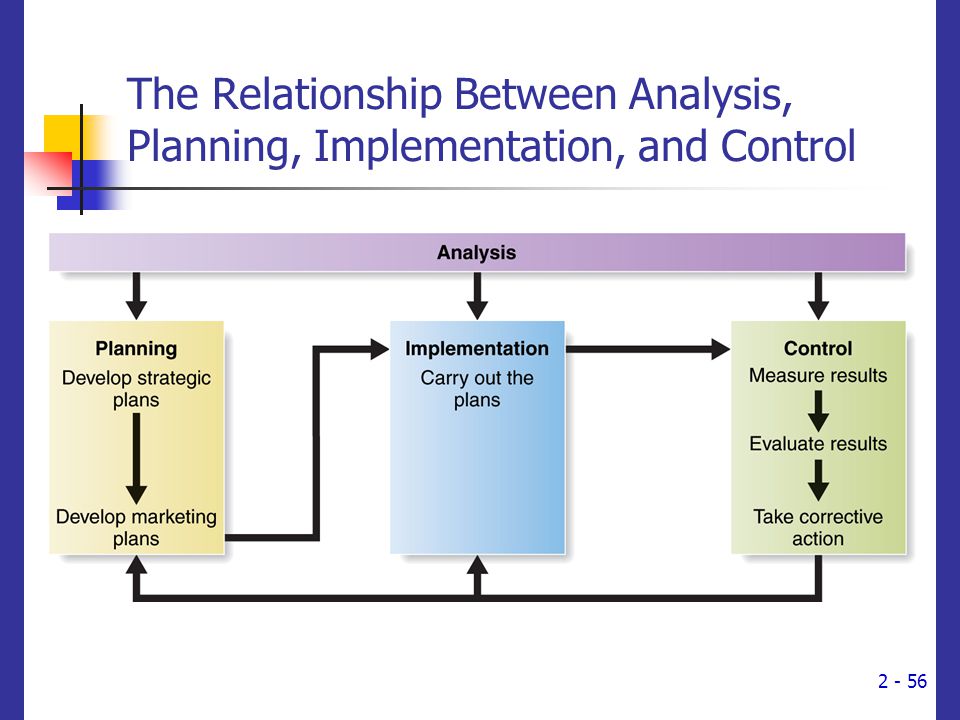

Unlike the rushed launch of the one-child policy in 1980, which was primarily a political decision based on little understanding of demography and society, researchers have played amuchmore active and meaningful role in calling for changes to end the policy. Scholars from leading institutions of population research in China formed an academic team in 2001. Their studies of China’s new demographic realities and the harmful consequences of continuing the ill-conceived one-child policy, and their three collective appeals to Chinese policymakers to relax and to end the one-child policy, in April 2004, January 2009, and most recently in January 2015, served as the basis for policy debates in China. Their efforts, along with efforts from many other sectors of society, informed the public of China’s new demographics and corrected the many misconceptions about population growth and the rationale for the one-child policy.

Scholars from leading institutions of population research in China formed an academic team in 2001. Their studies of China’s new demographic realities and the harmful consequences of continuing the ill-conceived one-child policy, and their three collective appeals to Chinese policymakers to relax and to end the one-child policy, in April 2004, January 2009, and most recently in January 2015, served as the basis for policy debates in China. Their efforts, along with efforts from many other sectors of society, informed the public of China’s new demographics and corrected the many misconceptions about population growth and the rationale for the one-child policy.

Yet, China’s policy change came at least a decade later than it should have. Changes to phase out the policy have been delayed because of leaderswho havemade population control part of their political legitimacy and a bureaucracy that has grown increasingly entrenched in the course of policy enforcement. In addition, the Chinese public has been thoroughly indoctrinated by the Malthusian fear of unchecked population growth and by a social discourse that has erroneously blamed population growth for virtually all of the country’s social and economic problems.

China’s one-child policy will be remembered as one of the costliest lessons of misguided public policymaking. Contrary to the claims of some Chinese officials, much of China’s fertility decline to date was realized prior to the launch of the one-child policy, under a much less strict policy in the 1970s calling for later marriage, longer birth intervals, and fewer births. In countries that had similar levels of fertility in the early 1970s without extreme measures such as the one-child policy, fertility also declined, and some achieved a level similar to China’s today. While playing a limited role in reducing China’s population growth, the one-child policy in the 35 years of its existence has created tens of millions, perhaps as many as 100 million, of China’s 150 million one-child families today. For these families, the harm caused by the policy is long-termand irreparable. Population aging in China is a burden not only for Chinese society as the support ratio between the working-age population and the elderly declines, but also for many of working age who are only children. Furthermore, China has had three decades of abnormal sex As a result, China now has a large pool of surplus men estimated at between 20 and 40 million.

Furthermore, China has had three decades of abnormal sex As a result, China now has a large pool of surplus men estimated at between 20 and 40 million.

The lukewarm response of couples to the partial relaxation in the second step largely confirmed findings from a pilot study in Jiangsu Province in 2007–2009 that very low fertility in China is more the result of choice than of policy restrictions. Other societies in EastAsia, like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, andHong Kong, have had little success in boosting their lowfertility evenwith pronatalist and pro-family policies. The end ofChina’s one-child policy therefore is unlikely to increase births in China by a significant number in the years to come.

What China has practiced under the one-child policy is clearly not voluntary family planning. To enforce the policy, China carried out massive sterilization and abortion campaigns. In 1983 alone, a year with about 21 million births in China, 14.4 million abortions, 20.7 million (predominantly female) sterilizations, and 17. 8 million IUD insertions were performed. A large proportion of these procedures were involuntary.

8 million IUD insertions were performed. A large proportion of these procedures were involuntary.

Future generations will likely look back at China’s one-child policy with bewilderment and disbelief. To many it will be incomprehensible why, of all countries that faced the challenge of rapid populationgrowth inthe second half of the twentieth century, onlyChinawent to such an extreme; incomprehensible why in a society based on respect for the family, kin, and filial piety, the government enforced a policy that effectively terminated many kin ties for at least a generation; incomprehensible why China instituted such a policy after the country had already experienced substantial fertility decline; and incomprehensible why China waited so long to end such a harmful policy. The costly lessons to be learned are not only in politics and public policymaking, but also in how parts of the academic community informed and misinformed public policymaking.

Related Books

While there are lessons to be learned from the misadventure of the one-child policy, it is worthwhile to recognize the importance of voluntary family planning services in reducing and averting unplanned childbearing and especially in improving the lives of women and children and in increasing gender equality. Access to safe, voluntary family planning services is a basic human right. The rapid fertility decline in China and around the world over the last half century would not have been possible without family planning services. Even in China, the government began to realize the central role of women in reproductive decisions and started to pay attention to the quality of family planning services in the 1990s. With the ending of the one-child policy, there is a clear and urgent need for re-education of China’s family planning and health service apparatus toward empowering couples to make informed choices about their fertility. China should continue providing free and safe access to voluntary family planning services and keep its focus on quality and on women’s reproductive health.

Access to safe, voluntary family planning services is a basic human right. The rapid fertility decline in China and around the world over the last half century would not have been possible without family planning services. Even in China, the government began to realize the central role of women in reproductive decisions and started to pay attention to the quality of family planning services in the 1990s. With the ending of the one-child policy, there is a clear and urgent need for re-education of China’s family planning and health service apparatus toward empowering couples to make informed choices about their fertility. China should continue providing free and safe access to voluntary family planning services and keep its focus on quality and on women’s reproductive health.

This piece was originally published in the journal of

Studies in Family Planning

.

Get daily updates from Brookings

Enter EmailWhat is China's one-child policy

Photo by Reuters

China has decided to end its long-standing "one-child policy" and allow all couples to have two children.

What was that?

This decades-long policy allowed many families to have only one child, but there were exceptions.

Chinese authorities estimate that this has prevented the birth of approximately 400 million children, although this figure is disputed.

In 2007, China stated that only 36% of citizens had one child due to various policy changes.

Why was this policy implemented?

As China's population approached one billion at the end of 1970, the government was concerned about how this would affect the country's ambitious economic growth plans.

Although other family planning programs had already been implemented by that time, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping decided that tough action was needed to reduce the birth rate.

The one-child policy was introduced in 1979.

How was it implemented?

The government implemented this policy by providing financial and labor incentives to those who adhered, and by making contraception widely available. Those who broke the rules were fined.

Those who broke the rules were fined.

Forced abortions and mass sterilizations were sometimes used.

This policy was strictly enforced in the cities.

Image copyright Reuters

Why is she so controversial?

Activists in China and the West claim that this policy is a gross violation of human and reproductive rights.

The traditional preference for male children, coupled with the one-child policy, has resulted in large numbers of girls being abandoned or placed in orphanages. There were also cases of selective abortions due to the sex of the child and even the killing of newborn girls.

As a result, China's gender balance has tilted towards men.

Why is it now abandoned?

Experts warn that China will be the first economy to grow old before it gets rich, largely because of the one-child policy.

In 2050, more than a quarter of the people in the country will be over 65 years old.

China's birth rate is one of the lowest in the world and well below the level required to replace a population in a generation.

The aging of the Chinese will slow down the economy as the number of young workers declines and the ratio between taxpayers and retirees continues to fall.

How were the rules relaxed?

In 2013, the rules changed: couples in which one of the parents is an only child were allowed to have a second child. But far fewer couples than the government expected have given birth to two children.

A preliminary relaxation of the rules in the 1980s allowed families in rural areas to have a second child if their first child was a girl.

In addition, the policy did not cover the country's ethnic minorities.

The third is not superfluous: why is China urgently curtailing the policy of birth control?

August 13, 2021, 10:35

Opinion

After almost half a century of "one family, one child" policy, China is urgently moving to stimulate the birth rate. After several unsuccessful attempts to provoke a baby boom, the Chinese authorities announced a national program to support young families.

After several unsuccessful attempts to provoke a baby boom, the Chinese authorities announced a national program to support young families.

The ruling party was the first to officially announce the change: on May 31 this year, the Politburo of the CPC Central Committee decided to allow families to have three children. In July, the State Council of the People's Republic of China actually "legalized" this decision: the authorities canceled fines and other punishments for the birth of a third child.

However, everything was not limited to this: now the government will not only not punish the birth of a third child, but, on the contrary, will encourage young families to have children and help them through various measures.

© Sheldon Cooper/SOPA Images/Sip via Reuters Connect

What made the government change the stick for the carrot? The answer is simple - the demographic crisis, which, according to the most pessimistic forecasts, could turn into almost a socio-economic catastrophe for China.

Read also

Media: Chinese authorities allowed families to have three children

Not so long ago, a huge population - 1.4 billion people - and cheap labor were China's "trump card". Many have heard about the economic miracle of this country, but not everyone thinks about the price at which it was achieved. In order to literally feed the population of the state, the authorities began to limit the birth rate about half a century ago. One-family-one-child policy, minimum pensions and social security, and other measures have enabled the government to save significant resources that would be needed to build even more schools, hospitals and other social infrastructure. However, this laid the foundation for the national renaissance as a ticking time bomb.

Getting old is not fun

The "one family, one child" policy has been in place in China since the 1970s, with families only allowed to have one child, with some exceptions. Parents who violated the rules faced heavy fines and serious penalties, including dismissal from civil service and expulsion from the Chinese Communist Party.

The birth rate has declined, and the problem of overpopulation has faded into the background. However, this unprecedented demographic experiment was not in vain - China began to "age" rapidly. Now in China there are about 200 million people over the age of 60 years. According to the forecasts of Chinese scientists, if the current trend is not reversed, then by 2030 the figure will reach 300 million, and by 2050 there will be about 487 million old people in China. In other words, the elderly will make up 35% of the country's population.

Wake-up call

When sociologists began to sound the alarm, the authorities were quick to assure that everything was under control, and in 2016 allowed families to have two children. However, the positive effect of this turned out to be short-lived and lasted only a couple of years: the birth rate continued to fall and, for example, by the end of 2020, it decreased by another 20% - to 12 million newborns (the lowest figure since 1961).

Read also

China abolishes fines for having a third child

New demographic forecasts have shown that the government needs to do something, and do it quickly, otherwise China's population will start to decline in 2027. And then who will work and feed the country, where by this time every third person will be a pensioner?

"Troubled" pension

The reaction of the government was not long in coming. In March this year, at a session of the Chinese Parliament, an upcoming increase in the retirement age was announced. Now for men it is 60 years, and for women - 55 years (and in the case of heavy physical labor - 50 years). According to the authorities, such an unpopular measure will save the country from complex social problems.

However, the people of China did not share the optimism of the authorities - most of the older generation will have to be content with rather modest pensions.

In this regard, the authorities are actively promoting Confucian values, especially when it comes to caring for the older generation. In 2013, the country's parliament even passed the controversial Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Older Generation. It obliges children to look after their parents over 60 and visit them regularly.

At the same time, if you ask any Chinese pensioner on the street what he is most afraid of, the answer will be simple - to become a burden for his children. In many ways, therefore, in second place among the causes of concern for Chinese grandparents is the fear of getting sick.

Due to the limited range of basic health insurance and the high cost of the healthcare system, this fear sometimes borders on a phobia among older people in China. Chinese social media is full of posts about how children sometimes sell cars, apartments and other property, as well as take out heavy loans to pay medical bills for their elderly parents.

See also

Only old men go into battle? How the birth rate became a time bomb for China

The COVID-19 pandemic only added to these fears. And although the authorities have already announced that coronavirus treatment will be completely free for citizens, and the basic health insurance package will be expanded, many residents of the country are confident that this social problem is still far from being solved.

The third is not superfluous

Against the background of the fact that in 2016 the formal permission to have a second child did not lead to the expected baby boom, the authorities carried out "work on the mistakes". In 2021, by allowing the younger generation to have a third child, the government has developed a series of "incentives" to give birth.

Now families with a large number of offspring should not face various administrative obstacles when registering at the place of residence, enrolling children in kindergartens, schools and universities, as well as when applying for a job.

The State Council of the People's Republic of China also announced that the government will consider providing a tax deduction for the cost of supporting children under three years of age. When providing social housing, local authorities will take into account the number of minor children in the family. The government also announced that the share of spending on education between families and schools will be revised, and control over the pricing of educational services will be strengthened.

War on tutors

At the same time, the Chinese authorities have already declared war on unscrupulous and illegal educational centers that "knock out" the last savings from parents. Graduation from high school and good grades in the state final exams - gaokao, which also serve as university entrance exams, are a nightmare for Chinese families and students themselves. Without good grades, it will be very difficult to get into a good university, and without a reputable higher education diploma, it will be difficult to find a prestigious and well-paid job.

Read also

Chinatown on the Neva. How the life of the Chinese diaspora in St. Petersburg works

Against this background, many educational centers inflate prices for gaokao preparation courses. Desperate parents do not spare anything for the well-being of their children, but they have a fair question: why do we need schools if their basic program is not enough to enter a good university?

Desperate parents do not spare anything for the well-being of their children, but they have a fair question: why do we need schools if their basic program is not enough to enter a good university?

In this regard, the country's authorities decided to act tough: school teachers are now threatened with sanctions and even dismissal for paid extracurricular activities. And Chinese social networks are already showing a plethora of videos of armed police breaking down the doors of illegal educational centers and detaining their teachers right in front of frightened schoolchildren. In parallel with such harsh methods, the government announced a reform of the educational sector: companies must stop making profits, they are prohibited from having foreign investors in their capital and conducting IPOs, using foreign educational literature, and hiring teachers from abroad.

Standing up for braces

Among other measures, the government announced the expansion of free medical services for women of childbearing age, protection of their interests in employment. In some regions, the authorities began to pay one-time and regular subsidies for the birth of children.

In some regions, the authorities began to pay one-time and regular subsidies for the birth of children.

In the expert community, there is talk that maternity leave will also be reformed - now Chinese women are entitled to 98 days of parental leave.

See also

Inequality and wealth. How the pandemic reveals weaknesses in society

The authorities actively promote traditional family values among the younger generation and urge not to delay the birth of children. Against this background, even LGBT people got it: in the past few months, dozens of the most popular communities and blogs among sexual minorities have been blocked and deleted on social networks. For many years, the authorities turned a blind eye to their activities in the student and youth environment, but now the government has decided to "tighten the screws" in this direction as well.

Point of no return

Despite the active measures of the authorities, some local and foreign sociologists draw very unfavorable forecasts for China. In their opinion, these steps are at least too late. In the era of globalization, Chinese society follows universal trends - following the growth of the level of education and well-being, young Chinese are increasingly postponing the creation of a family and the birth of children.

In their opinion, these steps are at least too late. In the era of globalization, Chinese society follows universal trends - following the growth of the level of education and well-being, young Chinese are increasingly postponing the creation of a family and the birth of children.

The results of the national census published this year did not add any optimism either. According to them, the total fertility rate in China was 1.3 births per woman. This is well below the replacement level of 2.1, which is in line with "aging" countries such as Japan and Italy.

In this regard, Chinese sociologists are sounding the alarm - China can "grow old" to the level of developed Western countries much earlier than it reaches their level of well-being. It remains to be seen whether the government will be able to reverse the oppressive demographic trajectory. Only one thing is clear - the demographic curve must be directed upwards before it passes the point of no return and sends the country into a peak of a large-scale crisis.