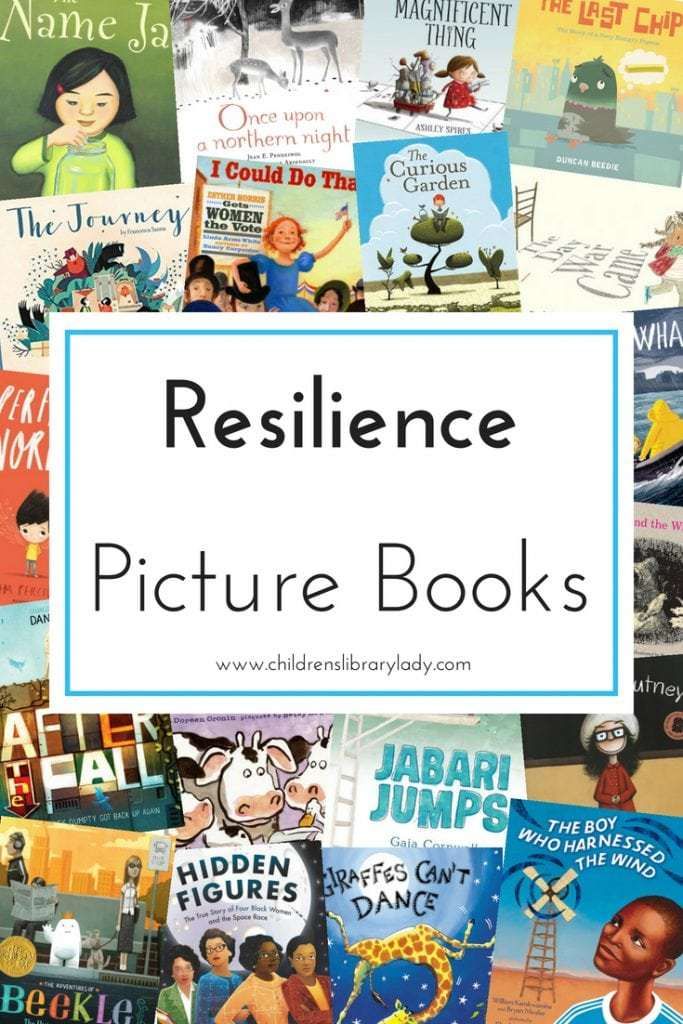

How to teach a child resilience

This Is How to Raise Resilient Kids

We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission. Here’s our process.

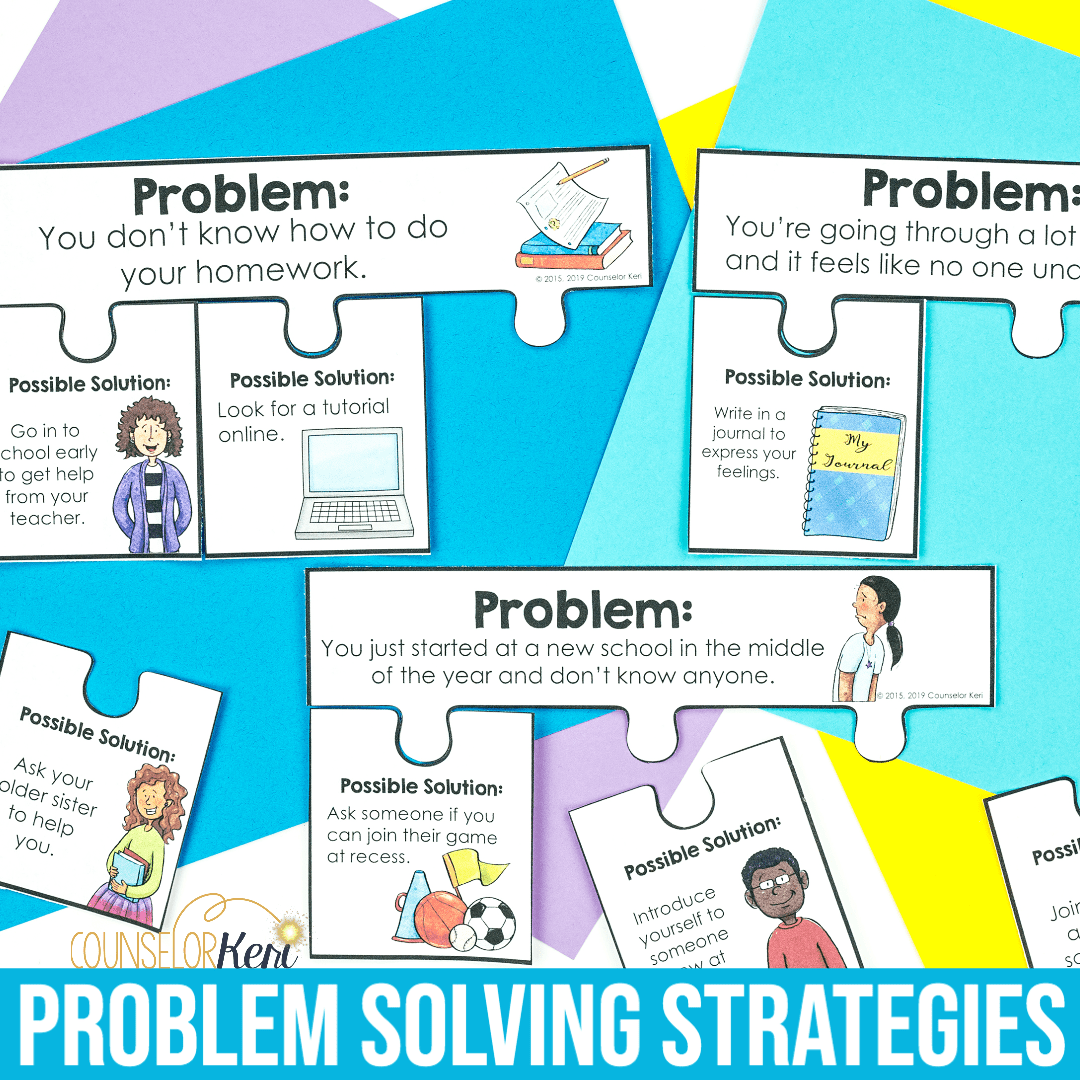

Resilient kids are adaptable problem solvers. They face unfamiliar or tough situations and strive to find practical solutions.

While adulthood is filled with serious responsibilities, childhood isn’t exactly stress-free. Kids take tests, learn new information, change schools, change neighborhoods, get sick, get braces, encounter bullies, make new friends and occasionally get hurt by those friends. They also face real-world, unfiltered traumas.

What helps kids in navigating these kinds of challenges is resilience.

Lynn Lyons is a licensed social worker and psychotherapist in Concord, New Hampshire, who co-authored the book “Anxious Kids, Anxious Parents: 7 Ways to Stop the Worry Cycle and Raise Courageous and Independent Children” with psychologist and anxiety expert Dr. Reid Wilson.

Lyons says when resilient kids step into a situation they “have a sense they can figure out what they need to do and can handle what is thrown at them with a sense of confidence.”

She said that this doesn’t mean that kids have to do everything on their own. Rather, they know how to ask for help and can problem-solve their next steps.

Resilience isn’t a birthright. It can be taught. Lyons encourages parents to equip their kids with the skills to handle the unexpected, which contrasts our cultural approach.

“We have become a culture of trying to make sure our kids are comfortable. We as parents are trying to stay one step ahead of everything our kids are going to run into.” The problem? “Life doesn’t work that way.”

Anxious people have an especially hard time helping their kids tolerate uncertainty simply because they have difficulty tolerating it themselves.

“The idea of putting your child through the same pain you went through is intolerable,” Lyons said. So anxious parents try to protect their kids and shield them from worst-case scenarios.

So anxious parents try to protect their kids and shield them from worst-case scenarios.

However, she said that a parent’s job isn’t to be there all the time for their kids. It’s to teach them to handle uncertainty and to problem-solve. Below, Lyons shared her valuable suggestions for raising resilient kids.

According to Lyons, “whenever we try to provide certainty and comfort, we are getting in the way of children being able to develop their own problem-solving and mastery.” (Overprotecting kids only fuels their anxiety.)

She gave a “dramatic but not uncommon example.” Suppose a child gets out of school at 3:15. But they worry about their parent picking them up on time. So the parent arrives an hour earlier and parks by their child’s classroom so they can see the parent is there.

In another example, parents let their 7-year-old sleep on a mattress on the floor in their bedroom because they’re too uncomfortable to sleep in their room.

Naturally, parents want to keep their kids safe. But eliminating all risks could rob kids of learning resiliency.

But eliminating all risks could rob kids of learning resiliency.

In one family Lyons knows, the kids aren’t allowed to eat when the parents are not home because there’s a risk they might choke on their food. (If the kids are old enough to stay home alone, they’re old enough to eat, she said.)

The key is to allow appropriate risks and teach your kids essential skills. “Start young. The child who’s going to get his driver’s license is going to have started when he’s 5 [years old] learning how to ride his bike and look both ways [slow down and pay attention].”

Giving kids age-appropriate freedom helps them learn their limits, she said.

Let’s say your child wants to go to sleep-away camp, but they’re nervous about being away from home. An anxious parent, Lyons said, might say, “Well, then there’s no reason for you to go.”

But a mindful approach is to normalize your child’s nervousness and help them figure out how to navigate being homesick. So you might ask your child how they can practice getting used to being away from home.

When Lyons’s son was anxious about his first final exam, they brainstormed strategies, including how he’d manage his time and schedule to study for the exam.

In other words, engage your child in figuring out how they can handle challenges. Give them the opportunity, over and over, “to figure out what works and what doesn’t.”

To paraphrase the adage, ‘If you give a kid a fish, you feed them for a day. If you teach a kid to fish, you feed them for a lifetime.’

When Lyons works with kids, she focuses on the specific skills they’ll need to learn to handle certain situations themselves.

She asks herself, “Where are we going with this [situation]? What skill do they need to get there?” For instance, she might teach a shy child how to greet someone and start a conversation.

“Why” questions don’t help promote problem-solving. If your child left their bike in the rain, and you ask, “why?” “what will they say? I was careless. I’m an 8-year-old,” Lyons said.

Try asking “how” questions instead. “You left your bike out in the rain, and your chain rusted. How will you fix that?” For instance, she said that they might go online to see how to fix the chain or contribute money to a new chain.

“You left your bike out in the rain, and your chain rusted. How will you fix that?” For instance, she said that they might go online to see how to fix the chain or contribute money to a new chain.

Lyons uses “how” questions to teach her clients different skills. “How do you get yourself out of bed when it’s warm and cozy? How do you handle the noisy boys on the bus that bug you?”

Rather than providing your kids with every answer, start using the phrase “I don’t know,” “followed by promoting problem-solving,” Lyons said. Using this phrase helps empower kids to learn to tolerate uncertainty and think about ways to deal with potential challenges.

Also, starting with small situations when they’re young helps prepare kids to handle bigger trials. She said they won’t like it, but they’ll get used to it.

For instance, if your child asks if they’re getting a shot at the doctor’s office, instead of soothing them, say, “I don’t know. You might be due for a shot. Let’s figure out how you’re going to get through it. ”

”

Similarly, if your child asks, “Am I going to get sick today?” instead of saying, “No, you won’t,” respond with, “You might, so how might you handle that?”

If your child worries they’ll hate their college, instead of saying, “You’ll love it,” you might explain that some freshmen don’t like their school and help them figure out what to do if they feel the same way, she said.

Try to pay attention to what you say to your kids and around them. Anxious parents, in particular, tend to “talk very catastrophically around their children,” Lyons said.

For instance, instead of saying, “It’s really important for you to learn how to swim because it’d be devastating to me if you drowned!” you might try just saying, “It’s really important for you to learn how to swim.”

“Failure is not the end of the world. [It’s the] place you get to when you figure out what to do next,” Lyons says. Letting kids mess up is tough and painful for parents. But it helps kids learn how to fix slip-ups and make informed decisions next time.

According to Lyons, if a child has an assignment, anxious or overprotective parents typically want to ensure the project is perfect, even if their child is not interested in doing it in the first place. But it’s helpful in the long run to let your kids see the consequences of their actions.

Similarly, Lyons said that if your child doesn’t want to go to football practice, you might let them stay home. If next game they sit on the bench, they might also be sitting with the weight of their decision.

Emotional intelligence (EQ) and self-regulation are key to resilience.

You can teach your kids that all emotions are OK, Lyons says. It’s OK to feel angry that you lost the game or someone else finished your ice cream. Caregivers can also teach kids that after feeling their feelings, they need to think through what they’re doing next, she said.

“Kids learn very quickly which powerful emotions get them what they want. Parents have to learn how to ride the emotions, too. ”

”

You might tell your child, “I understand that you feel that way. I’d feel the same way if I were in your shoes, but now you have to figure out what the appropriate next step is.”

If your child throws a tantrum, she says, be clear about what behavior is appropriate (and inappropriate). You might say, “I’m sorry we’re not going to get ice cream, but this behavior is unacceptable.”

Of course, kids also learn from observing their parents’ behavior. Try to be calm and consistent, Lyons said. “You cannot say to a child you want them to control their emotions while you yourself are flipping out.”

“Parenting takes a lot of practice and we all screw up.” When you do make a mistake, admit it. You could say, “I really screwed up. I’m sorry I handled that poorly. Let’s talk about a different way to handle that in the future,” Lyons said.

Resiliency helps kids navigate the inevitable trials, triumphs and tribulations of childhood and adolescence. Resilient kids also become resilient adults, able to survive and thrive in the face of life’s unavoidable stressors.

This Is How to Raise Resilient Kids

We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission. Here’s our process.

Resilient kids are adaptable problem solvers. They face unfamiliar or tough situations and strive to find practical solutions.

While adulthood is filled with serious responsibilities, childhood isn’t exactly stress-free. Kids take tests, learn new information, change schools, change neighborhoods, get sick, get braces, encounter bullies, make new friends and occasionally get hurt by those friends. They also face real-world, unfiltered traumas.

What helps kids in navigating these kinds of challenges is resilience.

Lynn Lyons is a licensed social worker and psychotherapist in Concord, New Hampshire, who co-authored the book “Anxious Kids, Anxious Parents: 7 Ways to Stop the Worry Cycle and Raise Courageous and Independent Children” with psychologist and anxiety expert Dr. Reid Wilson.

Reid Wilson.

Lyons says when resilient kids step into a situation they “have a sense they can figure out what they need to do and can handle what is thrown at them with a sense of confidence.”

She said that this doesn’t mean that kids have to do everything on their own. Rather, they know how to ask for help and can problem-solve their next steps.

Resilience isn’t a birthright. It can be taught. Lyons encourages parents to equip their kids with the skills to handle the unexpected, which contrasts our cultural approach.

“We have become a culture of trying to make sure our kids are comfortable. We as parents are trying to stay one step ahead of everything our kids are going to run into.” The problem? “Life doesn’t work that way.”

Anxious people have an especially hard time helping their kids tolerate uncertainty simply because they have difficulty tolerating it themselves.

“The idea of putting your child through the same pain you went through is intolerable,” Lyons said. So anxious parents try to protect their kids and shield them from worst-case scenarios.

So anxious parents try to protect their kids and shield them from worst-case scenarios.

However, she said that a parent’s job isn’t to be there all the time for their kids. It’s to teach them to handle uncertainty and to problem-solve. Below, Lyons shared her valuable suggestions for raising resilient kids.

According to Lyons, “whenever we try to provide certainty and comfort, we are getting in the way of children being able to develop their own problem-solving and mastery.” (Overprotecting kids only fuels their anxiety.)

She gave a “dramatic but not uncommon example.” Suppose a child gets out of school at 3:15. But they worry about their parent picking them up on time. So the parent arrives an hour earlier and parks by their child’s classroom so they can see the parent is there.

In another example, parents let their 7-year-old sleep on a mattress on the floor in their bedroom because they’re too uncomfortable to sleep in their room.

Naturally, parents want to keep their kids safe. But eliminating all risks could rob kids of learning resiliency.

But eliminating all risks could rob kids of learning resiliency.

In one family Lyons knows, the kids aren’t allowed to eat when the parents are not home because there’s a risk they might choke on their food. (If the kids are old enough to stay home alone, they’re old enough to eat, she said.)

The key is to allow appropriate risks and teach your kids essential skills. “Start young. The child who’s going to get his driver’s license is going to have started when he’s 5 [years old] learning how to ride his bike and look both ways [slow down and pay attention].”

Giving kids age-appropriate freedom helps them learn their limits, she said.

Let’s say your child wants to go to sleep-away camp, but they’re nervous about being away from home. An anxious parent, Lyons said, might say, “Well, then there’s no reason for you to go.”

But a mindful approach is to normalize your child’s nervousness and help them figure out how to navigate being homesick. So you might ask your child how they can practice getting used to being away from home.

When Lyons’s son was anxious about his first final exam, they brainstormed strategies, including how he’d manage his time and schedule to study for the exam.

In other words, engage your child in figuring out how they can handle challenges. Give them the opportunity, over and over, “to figure out what works and what doesn’t.”

To paraphrase the adage, ‘If you give a kid a fish, you feed them for a day. If you teach a kid to fish, you feed them for a lifetime.’

When Lyons works with kids, she focuses on the specific skills they’ll need to learn to handle certain situations themselves.

She asks herself, “Where are we going with this [situation]? What skill do they need to get there?” For instance, she might teach a shy child how to greet someone and start a conversation.

“Why” questions don’t help promote problem-solving. If your child left their bike in the rain, and you ask, “why?” “what will they say? I was careless. I’m an 8-year-old,” Lyons said.

Try asking “how” questions instead. “You left your bike out in the rain, and your chain rusted. How will you fix that?” For instance, she said that they might go online to see how to fix the chain or contribute money to a new chain.

“You left your bike out in the rain, and your chain rusted. How will you fix that?” For instance, she said that they might go online to see how to fix the chain or contribute money to a new chain.

Lyons uses “how” questions to teach her clients different skills. “How do you get yourself out of bed when it’s warm and cozy? How do you handle the noisy boys on the bus that bug you?”

Rather than providing your kids with every answer, start using the phrase “I don’t know,” “followed by promoting problem-solving,” Lyons said. Using this phrase helps empower kids to learn to tolerate uncertainty and think about ways to deal with potential challenges.

Also, starting with small situations when they’re young helps prepare kids to handle bigger trials. She said they won’t like it, but they’ll get used to it.

For instance, if your child asks if they’re getting a shot at the doctor’s office, instead of soothing them, say, “I don’t know. You might be due for a shot. Let’s figure out how you’re going to get through it. ”

”

Similarly, if your child asks, “Am I going to get sick today?” instead of saying, “No, you won’t,” respond with, “You might, so how might you handle that?”

If your child worries they’ll hate their college, instead of saying, “You’ll love it,” you might explain that some freshmen don’t like their school and help them figure out what to do if they feel the same way, she said.

Try to pay attention to what you say to your kids and around them. Anxious parents, in particular, tend to “talk very catastrophically around their children,” Lyons said.

For instance, instead of saying, “It’s really important for you to learn how to swim because it’d be devastating to me if you drowned!” you might try just saying, “It’s really important for you to learn how to swim.”

“Failure is not the end of the world. [It’s the] place you get to when you figure out what to do next,” Lyons says. Letting kids mess up is tough and painful for parents. But it helps kids learn how to fix slip-ups and make informed decisions next time.

According to Lyons, if a child has an assignment, anxious or overprotective parents typically want to ensure the project is perfect, even if their child is not interested in doing it in the first place. But it’s helpful in the long run to let your kids see the consequences of their actions.

Similarly, Lyons said that if your child doesn’t want to go to football practice, you might let them stay home. If next game they sit on the bench, they might also be sitting with the weight of their decision.

Emotional intelligence (EQ) and self-regulation are key to resilience.

You can teach your kids that all emotions are OK, Lyons says. It’s OK to feel angry that you lost the game or someone else finished your ice cream. Caregivers can also teach kids that after feeling their feelings, they need to think through what they’re doing next, she said.

“Kids learn very quickly which powerful emotions get them what they want. Parents have to learn how to ride the emotions, too. ”

”

You might tell your child, “I understand that you feel that way. I’d feel the same way if I were in your shoes, but now you have to figure out what the appropriate next step is.”

If your child throws a tantrum, she says, be clear about what behavior is appropriate (and inappropriate). You might say, “I’m sorry we’re not going to get ice cream, but this behavior is unacceptable.”

Of course, kids also learn from observing their parents’ behavior. Try to be calm and consistent, Lyons said. “You cannot say to a child you want them to control their emotions while you yourself are flipping out.”

“Parenting takes a lot of practice and we all screw up.” When you do make a mistake, admit it. You could say, “I really screwed up. I’m sorry I handled that poorly. Let’s talk about a different way to handle that in the future,” Lyons said.

Resiliency helps kids navigate the inevitable trials, triumphs and tribulations of childhood and adolescence. Resilient kids also become resilient adults, able to survive and thrive in the face of life’s unavoidable stressors.

Shook himself off and went: how to teach a child to calmly accept difficulties

Maria Ananyeva

In fact, elephants are very similar to humans. They experience the same emotions as we do, they grieve for the dead and take care of the little elephants together. The family is very important for them - the bonds within the herd are very strong and are maintained throughout their lives. If the cub is threatened or injured, the other elephants protect and comfort it.

But when the baby elephant turns 14, he is kicked out of the herd. He becomes independent. Agree, we have a lot to learn from elephants. And Julie Litcott-Hames. She wrote the book Let Them Go, which tells how to prepare children for adulthood.

Source

Today we protect, praise, support and guide our children, we try to do as much as possible for them and protect them from failures, worries and troubles. At the same time, there is a high risk of raising a pampered eternal teenager who is used to relying on the help of his parents in everything and does not know how to cope with difficulties on his own.

We forget that childhood is a time of trial and error, the opportunity to learn one's abilities and believe in one's own strength, and not in the fact that parents will definitely help in any situation. How to approach education in such a way that the child does not get bogged down in dependence and is ready for adulthood? In order for our children to accept difficulties normally, we must help them become resilient.

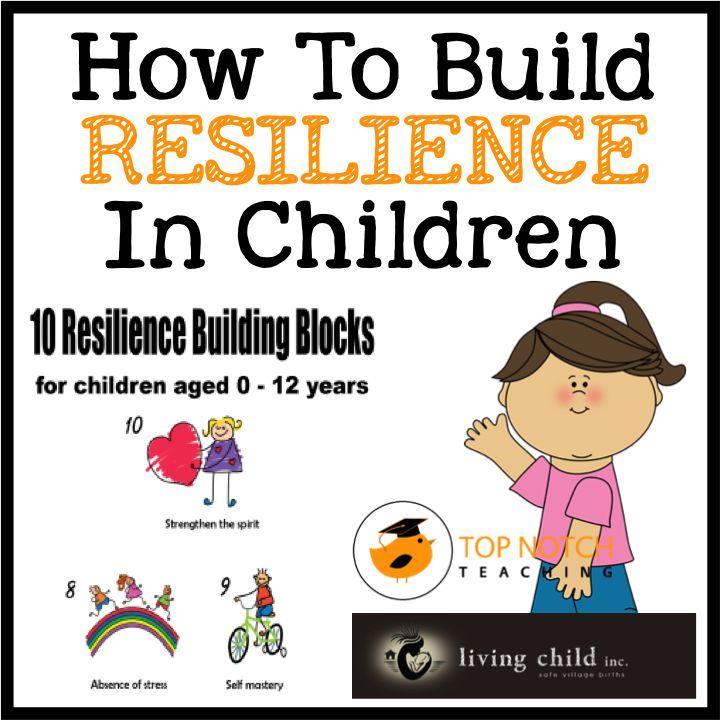

What makes up resilience and how we can influence its formation in our children

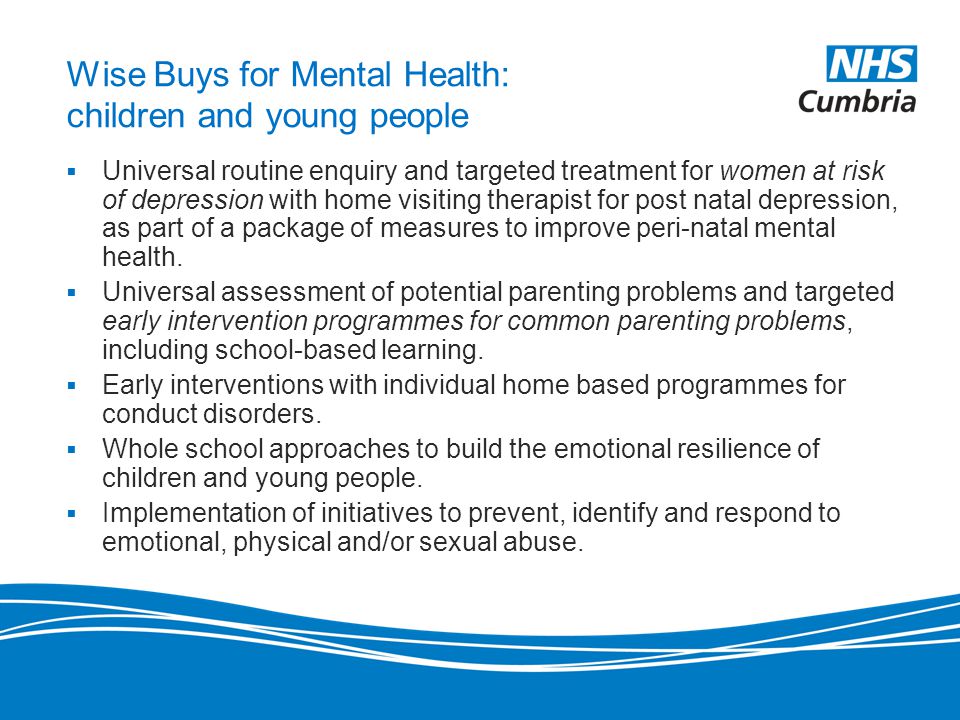

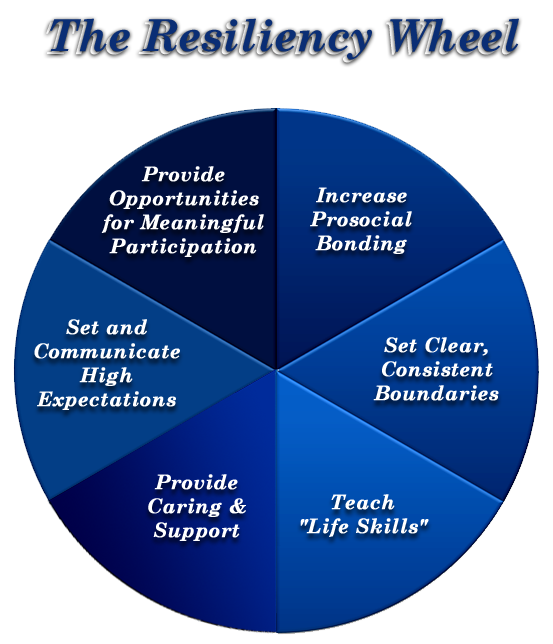

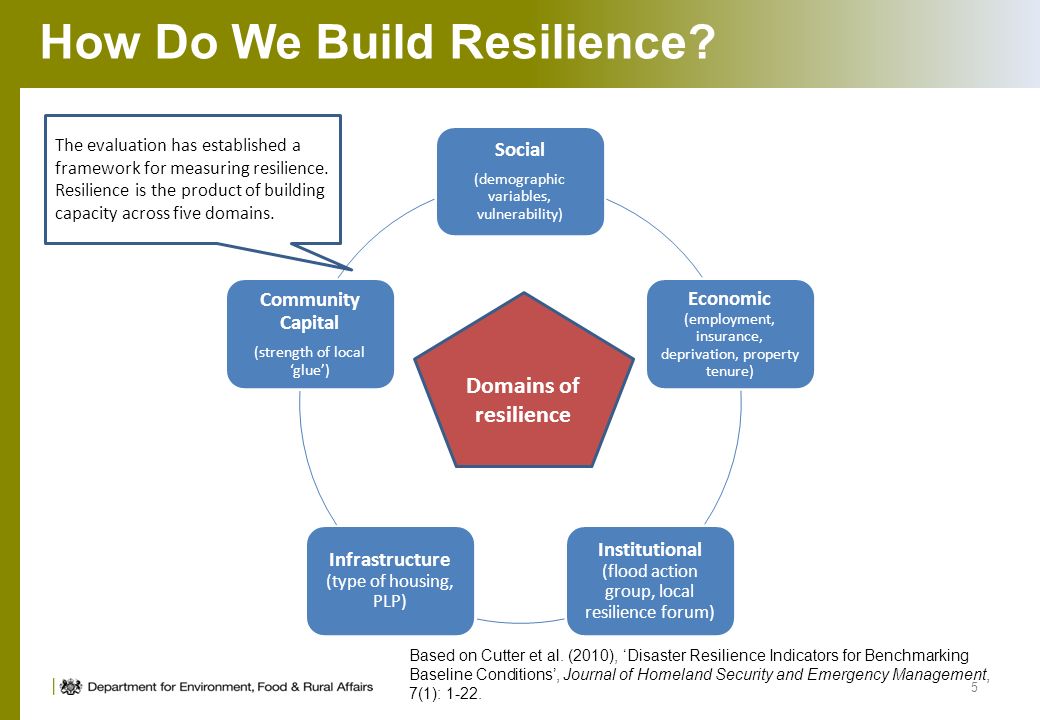

Resilience is the ability to bounce back after adversity, keep going forward and not give up trying. Pediatrician and adolescent development specialist Dr. Kenneth Ginsburg says that resilience is made up of seven factors: competence, confidence, connections, character, contribution, fighting ability, and power.

Source

What can we do to build resilience in our children? Here are 6 tips to follow:

1. Be in your child's life by spending quality time with them.

Show your love. As Julie Lythcott-Hames said in her over two million-view TED talk: “Instead of obsessing over grades and points, when our precious child comes home from school or when we come home from work, we should turn off all our devices, put our phones away. look into his eyes, and let him see the joy that illuminates our faces at the sight of our child for the first time in several hours. Ask how your day went, what was good. And if the child answers, "Lunch," while you want to know your test score, ask, "What was delicious for lunch?"

2. Don't interfere, let the child have his own experience.

Mobile phones have been dubbed "the world's longest umbilical cord". Our constant monitoring, accompaniment and support undermine the confidence of children. Let the child decide what to do first: math or Russian. A task for more advanced parents: let the child do his homework on his own, without your checking 🙂

Source

whether it threatens life or health. If not, take your will into a fist and keep silent.

If not, take your will into a fist and keep silent.

3. Help your child gain experience.

You must have met mother-daughter tandems at scheduled check-ups in a children's clinic. Mom proudly unwraps the baby and nurses him, and her daughter shifts from foot to foot next to her. This is her child, and she herself is an adult and capable. It’s just that mom “knows better” and doesn’t leave her daughter a chance to gain experience herself.

Have your child wash their cup and plate after dinner. Let it not be perfect - it is the attempt, the effort, that is important here. Teach an older child how to sew on buttons. The older the children get, the more responsibilities you can give them - from cooking scrambled eggs to complex dishes. And let your daughter cut off the bangs, which she has been dreaming of for the second year. You and I know what happens when bangs begin to grow back. Where? That's right, we found out by experience.

4. Shape the child's character.

Show your children that you are proud of their human qualities, not marks and prizes. “Why do we need a road if you can’t take a grandmother through it,” they noted in the film “What Men Talk About”. Notice and discuss the child's good deeds. For example, if in a store a child helped a woman to get goods from a shelf, on the way home you can say: “It was very nice of you to help her.”

Help your child learn to look from the outside and think about how you can help people who are nearby. There are many opportunities to lend a helping hand to others. Instead of buying flowers for September 1, donate money to a charity fund, donate things to those in need, buy a bunch of parsley from your grandmother in the market - not because you need parsley, but because your grandmother needs support.

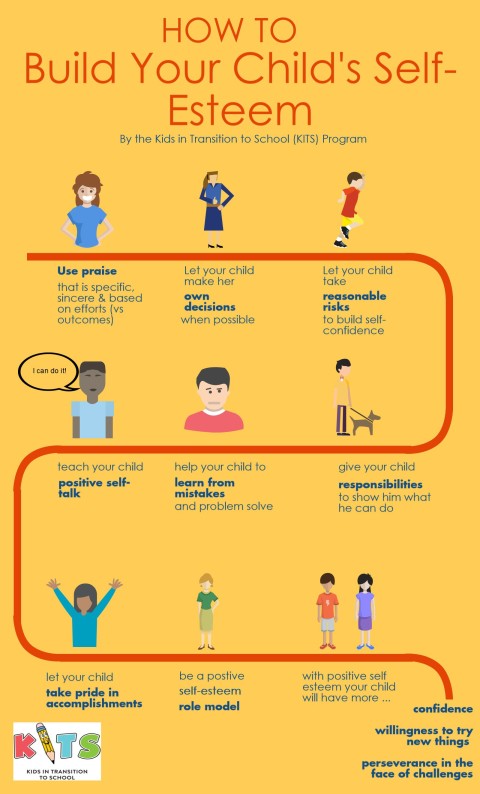

5. Praise and criticize sincerely and specifically.

Adequate and positive self-esteem is formed on the basis of one's own efforts and results. May your praise be genuine. It is better to praise what is related to a specific task completed. Not "Great! You are just a genius!", and "I really liked your essay, as if you read the thoughts of the protagonist."

It is better to praise what is related to a specific task completed. Not "Great! You are just a genius!", and "I really liked your essay, as if you read the thoughts of the protagonist."

Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck advises correcting the fixed mindset that occurs when children are praised for their intelligence. As a result, they begin to avoid difficulties so that the result does not contradict the received characteristic. It is better to explain that effort (which is in the power of the child) is more important than innate mental abilities (which he does not influence).

Criticism must be constructive. Criticize not a child, but an action that can be corrected. Remember how Malvina taught Pinocchio calligraphy: when he planted an inkblot, she called him an ugly naughty and sent him to a closet. It would be more correct to say something like: “Pinocchio, my friend. Just look at these blots. If you hadn't stuck your nose in the inkwell, this wouldn't have happened. You have to be more careful."

You have to be more careful."

6. Lead by example.

There is an anecdote. “Having learned that the International Olympic Committee does not consider poker a sport, the players were upset, but did not show it.” When something goes wrong with yourself, do not hide your grief from the children. This is one of the best ways to show that complexity is okay. Let the children see you admit your mistakes, be resilient, and move forward.

Last week my son and his classmates went to an intellectual camp. It took seven hours to drive, everyone calculated so that they would arrive at the very distribution and acquaintance, and still they had to order a taxi for five in the morning. By the appointed time, there was no car. The coach of the guys found out that they had lost the application at the depot, found out the phone number of the minibus driver and re-arranged the trip. Everyone had to be a little nervous, besides, they could sleep for half an hour longer, but the guys got a lesson in constructive problem solving.

Controlled Risk and Necessary Mistakes

In one of her lectures Tatyana Chernigovskaya, Doctor of Biology, gave an interesting example of controlled risk when raising children in English private schools. They prefer not to read lectures and warn about the negative consequences of running in white golf, but specifically expose children to controlled risk.

Literally adjust the fall so that the child has an abrasion, but so that in the future he does not lose his head and knows what to do in the event of a real fall.

Source

To err is human. Childhood is a training ground where you can make mistakes, learn lessons and develop the ability to cope with difficulties. Let the children have this important experience of struggling, failing, and falling. This is the best way to help them learn and grow. Mistakes are great life teachers. Do not rush to help with every difficulty that arises, and children will learn to cope with them themselves.

Based on the book Let Them Go.

Post cover: pixabay.

Do you want to learn about the most interesting children's books and receive discounts on the best novelties? Subscribe to our newsletter. The first letter is a gift.

How to teach a child to cope with difficulties

372

Since we are all loving parents, then, naturally, on an instinctive level, we strive to protect the child from difficulties and trials, or at least alleviate them. But are we doing well for our child?

The difficulties of childhood are manifold: there are conflicts with friends, bad grades, failed exams, and defeats in sports competitions. Difficulties also include the child's personal characteristics - for example, poor eyesight, hearing, speech defects, etc. We cannot live the life of a child for him, but it is in our power to provide him with the skills that will help him survive and thrive.

When your child is faced with an obstacle, it is very important not to give him a solution or a way out "on a silver platter", but to give him the opportunity to find this way out on his own, using his mental, emotional and physical capabilities. Overcoming small obstacles makes a person stronger and prepares for bigger challenges. Mastering new skills strengthens and increases the child's self-confidence, while excessive care and assistance, on the contrary, hinder the development of the ability to cope with difficulties. However, this is not so easy to do! It is extremely difficult for any parent to resist the temptation to "show it right" or "fix everything for the baby."

How to help a child overcome a difficulty without doing something for him?

- First, of course, you need to show your child that you believe in him and his strength. Support him with the words "You will definitely succeed!", "You can!"

- Praise even the smallest success - "You see, you are already doing much better!"

- Compare your child's successes or failures only with his own achievements, and not with the achievements of other children.

It is important that each time the child does something better than he did the last time, and not better than someone else does it.

It is important that each time the child does something better than he did the last time, and not better than someone else does it. - Resilience - protect your child from serious threats and harm, but do not shield him from the necessary impressions and experiences, even if they are painful.

- Use the difficulties that the child is experiencing to once again remind him of your UNCONDITIONAL love, i.e. love that does not depend on his victories and defeats.

- Analyze, discuss with the child all the difficult situations and failures that he had to endure, but only when emotions subside, when the child is calm. Try each time together to answer the question "Why did I fail and what can I do to succeed next time?"

- Similarly analyze cases of victories - "What helped to be successful?" Draw the attention of the child to what results he has achieved thanks to his perseverance, diligence, diligence, etc.

Remember that the difference between success and failure is often very simple: it comes down to how a person perceives the obstacle encountered - as a barrier that cannot be overcome, or as one of the stages that requires additional effort.

It is said that when Thomas Edison was asked if the 1,073 failures he had suffered before he invented the electric light bulb (sometimes a little more, sometimes a little less) discouraged him, the inventor replied: “But I did not suffer any failures. I just figured out 1073 ways you can't invent the light bulb."

Help your child learn to find a way out of the situation on his own, let him discover in himself a bottomless source of strength and ingenuity!

Did you like it? Share with friends:

Online classes on the Razumeikin website:

-

develop attention, memory, thinking, speech - namely, this is the basis for successful schooling;

-

help to learn letters and numbers, learn to read, count, solve examples and problems, get acquainted with the basics of the world around;

-

provide quality preparation of the child for school;

-

allow primary school students to master and consolidate the most important and complex topics of the school curriculum;

-

broaden the horizons of children and in an accessible form introduce them to the basics of various sciences (biology, geography, physics, chemistry).