How to restrain a child with autism

Restraint & Seclusion | A Guide for Autism Parents

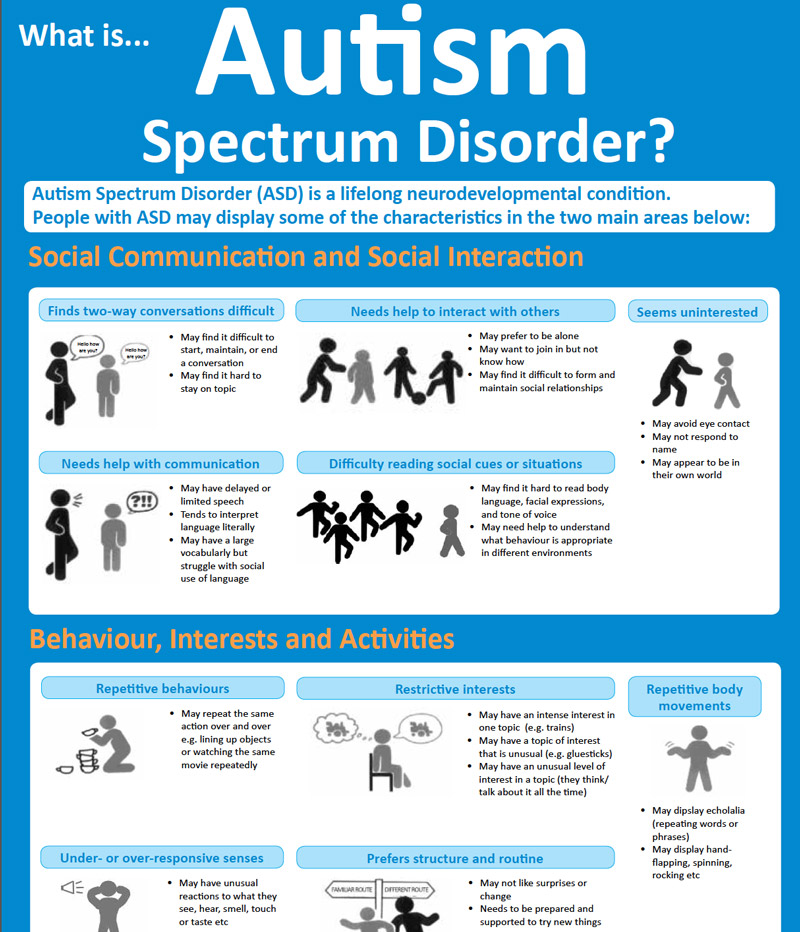

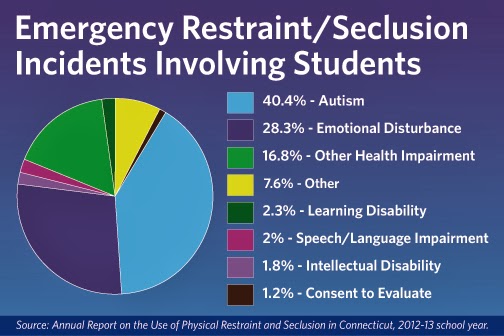

In May 2009 the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) completed its nationwide investigation into the use of restraint & seclusion in public schools. The result of its findings concluded that no federal laws were in place to keep educators from using dangerous and abusive methods to restrain or seclude a student. This is especially troubling for students with special needs, particularly for those with communication challenges.

While most teachers and aides are compassionate and caring individuals, there are cases of abuse and overuse of restraint and seclusion practices.

What is restraint/seclusion?

Restraint is physical force used to immobilize — or reduce the ability of — an individual, whereas seclusion is involuntary confinement of an individual alone in a room or area from which they are physically prevented from leaving.

Restraint and seclusion practices are commonly used in our public schools systems. In a recent school year, restraint and seclusion techniques were used 267,000 times, many for non-emergency reasons.

What are the different types of restraint?

- Prone Restraint means that the child is laid in the facedown position.

- Supine Restraint means that the child is laid in the face-up position.

- Physical restraints involve a person applying various holds using their arms, legs or body weight to immobilize an individual or bring an individual to the floor.

- Mechanical restraints include straps, cuffs, tape and other devices to prevent movement and/or sense perception, often by pinning an individual’s limbs to a splint, wall, bed, chair or floor.

- Chemical restraints rely on medication to dull an individual’s ability to move and/or think.

What are the signs of restraint/seclusion?

While many of children with autism are nonverbal or minimally verbal, there are some ways to tell if restraint/seclusion techniques have been used. They can include:

They can include:

- Bruising or abraded, reddened skin on arms, wrists, or ankles

- Unusual injuries

- Sudden regressions

- The emergence of new and unexplained behavior problems at home such as sleeplessness, nightmares, increased anxiety levels, or emotional outbursts

- The appearance of new problem behavior at school

- The appearance or intensification of self-injurious behaviors and/or increased aggression

- Fear of a particular teacher, aide, substitute, staff member

- The emergence of a school phobia (especially when the child previously enjoyed attending school) or of a more generalized fear of leaving home

- Emergence of specific fears that may be related to particular aversive, restraint, or seclusion techniques (such as fear of spray bottles, seatbelts, or closets)

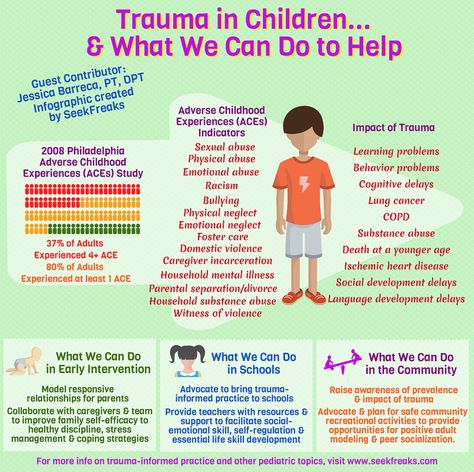

- Acting out of the traumatic experience/s in play (e.g. a child who experiences physical abuse may begin to play roughly with dolls or peers)

- Not wanting to be alone

- Loss of interest in things he/she use to enjoy

P. O.S.I.T.I.V.E Tips for Parents

O.S.I.T.I.V.E Tips for Parents

Restraint and seclusion practices vary by state, district, and classroom. If you’re worried about your child’s safety, remember to stay P.O.S.I.T.I.V.E. by using these tips:

P. PREPARE. Prepare to address any safety concerns ahead of time by assessing and documenting any known meltdown triggers in the classroom or campus (noise, light, stressors, etc.)

O. OPEN THE DISCUSSION. Open up the conversation to address your concerns about restraint and seclusion practices. Just by asking questions, you are more likely to prevent high-risk situations from ever occurring. Be polite, but direct. “What’s your policy of restraint & seclusion practices?” Even as the school year advances, continue to ask questions: has my child ever been restrained, or secluded? Keep the conversation open and ongoing.

S. SUBMIT.Submit letters to your child’s school or in his/her IEP outlining any special safety requirements or requests. Include a “no restraint” letter stating that your child is never to be secluded, and should only be restrained as a last-resort measure in the face of imminent danger. Request immediate notification of any incidents, and be sure to note any medical contraindications (obesity asthma, GI, heart issues, etc.) to restraint.

Include a “no restraint” letter stating that your child is never to be secluded, and should only be restrained as a last-resort measure in the face of imminent danger. Request immediate notification of any incidents, and be sure to note any medical contraindications (obesity asthma, GI, heart issues, etc.) to restraint.

I. INFORM. Inform teachers, aides, and substitute teachers about your child’s meltdown triggers, calming methods, and de-escalation techniques by creating a student profile sheet. This one-sheeter is a basic “do’s and dont’s” guide, which can be as simple as stapling a photo of your child to a piece of paper that provides basic, yet critical, information. Be sure to include emergency contact numbers, and a reminder to call you instead of police in the event of a meltdown.

T. TEAM UP. Rely on others by teaming up with a trusted teacher, parent volunteer, even student who can look out for your child. Keep an open dialogue with allies so you know and understand what’s happening inside and outside of the classroom during your child’s school day. Continue to ask about your child’s mood, progress, social opportunities, peer interactions, and behaviors during non-classroom times, such as lunch and recess.

Continue to ask about your child’s mood, progress, social opportunities, peer interactions, and behaviors during non-classroom times, such as lunch and recess.

I. INVITE. Invite feedback and recommendations from school staff, IEP team members, and therapists. While we tend to know our children best, behaviors may differ in the school setting. Ask teachers and aides for their input and listen intently to any concerns or ideas they may have. It’s a team effort, and both parties should be able to develop, agree upon, and incorporate strategies into both settings for maximum consistency.

V. VOLUNTEER. Donate your time in the classroom, during field trips or fundraisers, and in the school’s PTO or PTA. Be an active participant and supporter of your child’s teachers, and the rest of the school staff. Also show your appreciation. It can be as simple as a hand-written note thanking your child’s teachers, or bringing in treats to eat. The more positive participation you have within the school, the better the relationship will be among all of those caring for your child.

E. EDUCATE. Educate your child about dangers, consequences, and ways to stay safe. While language deficits may make it difficult to gauge your child’s understanding of the information presented, continue to speak it, write it, and show it through a picture system, social story or other preferred method. The ultimate goal is for your child to know and understand dangers, how to communicate abuse, and most of all, self-protection.

What if there are signs of restraint, seclusion, or abuse?

If you do suspect your child has been mistreated, here are some steps to take:

- Remain calm.

- Seek immediate medical attention if your child has any visible signs of abuse.

- Document everything & take pictures of your child’s condition.

- Consider reporting to police, and call your state’s protection and advocacy group.

- If your child has a trusted psychologist or professional counselor, contact them as well.

Will there be a federal bill?

A couple of lawmakers have stepped up to introduce legislation that would provide basic protections for students. You can read the bill language here, and contact your local lawmakers to ask for their support.

Restraint and seclusion can be scary to think about, but with the right precautions, parents can reduce the risk. For more resources, visit the Stop Hurting Kids website or NAA’s Autism Safety Site.

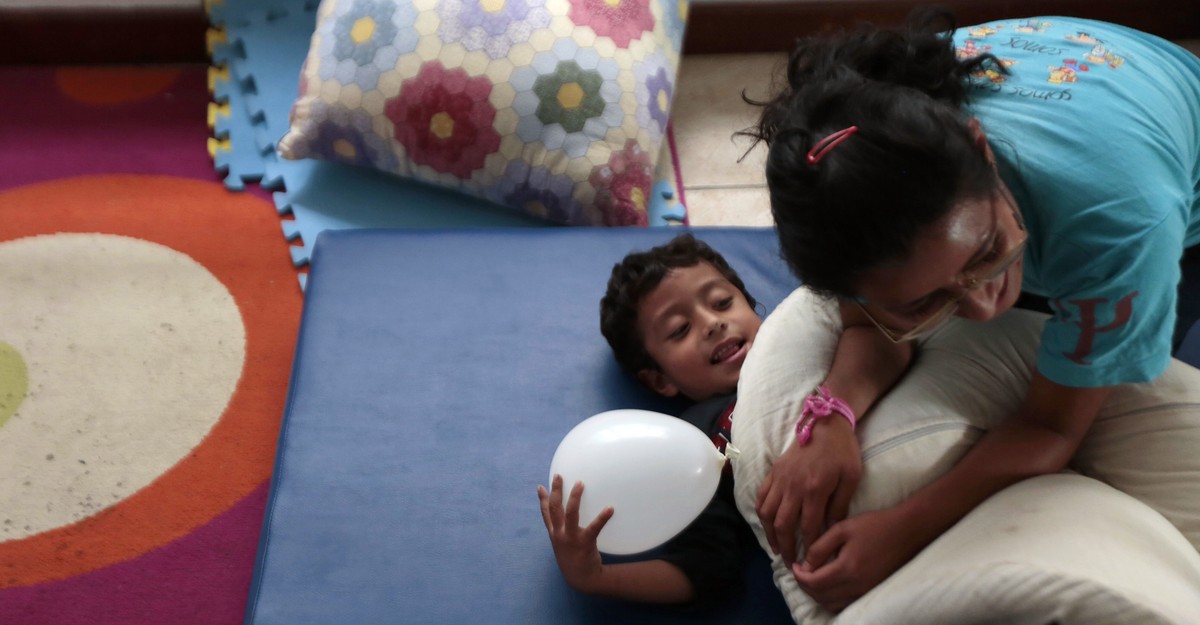

Free From Restraints: Gentle Ways To Help an Autistic Child Manage Meltdowns

As parents and supporters of autistic children, we are often put in situations where our children are being physically restrained during meltdowns. Whether it is in a school situation or at home, restraints and holds have been the norm for many years for individuals on the spectrum. What I love about the Low Arousal Approach is that it offers a gentle alternative that works. That’s the key. It’s not just a nice ideology; it’s effective. It leaves the person who would traditionally be doing the restraining, and the person that would have been restrained, with both their dignity and actionable tools. This article has been adapted from a longer piece written by one of our Danish colleagues, Scott Larsen, who implemented the Low Arousal Approach at the Pindstrup School in Denmark. Pindstrup is a special needs school for children with autism, ADHD, moderate learning difficulties and associated behavioural difficulties. – Maureen Bennie

It’s not just a nice ideology; it’s effective. It leaves the person who would traditionally be doing the restraining, and the person that would have been restrained, with both their dignity and actionable tools. This article has been adapted from a longer piece written by one of our Danish colleagues, Scott Larsen, who implemented the Low Arousal Approach at the Pindstrup School in Denmark. Pindstrup is a special needs school for children with autism, ADHD, moderate learning difficulties and associated behavioural difficulties. – Maureen Bennie

“The vast majority of challenging situations are inadvertently triggered by supporters, and we are often unaware that we can trigger situations”, Andrew McDonnell, founder of the Low Arousal Approach, 2010.

The above statement outlines the underlying premise behind “Low Arousal”, a behaviour management approach that seeks to reduce the points of conflict that lead to challenging behaviour when working with people with autism. But what can the statement tell us? First of all, it tells us we need to explore our own behaviour and emotional responses that arise in the intense, complex and developing work with children and adults with additional needs. It also tells us that even though we are a part of the problem, we have plenty of opportunities to be part of the solution.

But what can the statement tell us? First of all, it tells us we need to explore our own behaviour and emotional responses that arise in the intense, complex and developing work with children and adults with additional needs. It also tells us that even though we are a part of the problem, we have plenty of opportunities to be part of the solution.

Highly stressed children, emotional meltdowns and challenging behaviour are undeniably a part of everyday life in a school for children with additional needs. That is why crisis management became a significant focus at Pindstrup, and why Low Arousal was implemented at the school five years ago. When asked about the effect Low Arousal has had on the school. Vice-principal Lone Bridal Hansen immediately mentioned a decrease in the number of physical restraints at the school. As Lone Bridal put it:

“When you can better understand why children sometimes enter high states of arousal, you are also better able to act in a different way.

”

How does low arousal work to reduce the need for restraints?

Many of the core principles of the Low Arousal approach can be distilled into a single phrase: before you attempt to change or manage another person, you need to reflect on your own behaviour.

It is precisely in the tension of a challenging moment that parents, teachers and support staff can look at how they were a part of the problem, but also how they can be a part of the solution.

But how is this implemented in practice? Dr Andrew McDonnell – founder of Studio 111 and the Low Arousal Approach – explains that there are four key elements to consider in crisis situations:

1) Reduce staff demands and potential conflict triggers around the child. Take into account a child’s sensory challenges or different cognitive functions that can affect their experience of a situation. By curtailing trigger situations, you may be able to avoid a meltdown before it happens, or lessen one. You can learn more about how to notice and keep track of triggers in this past blog post about Tantrums vs Autistic Meltdowns.

You can learn more about how to notice and keep track of triggers in this past blog post about Tantrums vs Autistic Meltdowns.

2) Avoid arousal triggers. When a child seems like they could be heading for an overload meltdown, stay away from direct eye contact, touch, and excuse any onlookers to the event that who could potentially elevate the child’s level of stress or excitement.

3) Ensure that parent/staff/support person is aware of their own attitudes and body language. When you are dealing with a highly stressed or sensory overloaded individual, it is important to avoid a confrontational posture, or attitude. Confrontational body language can cause further stress in a child you are trying to calm down – and on the flip side, appropriate postures and attitudes can reduce a child´s level of stress and reactions.

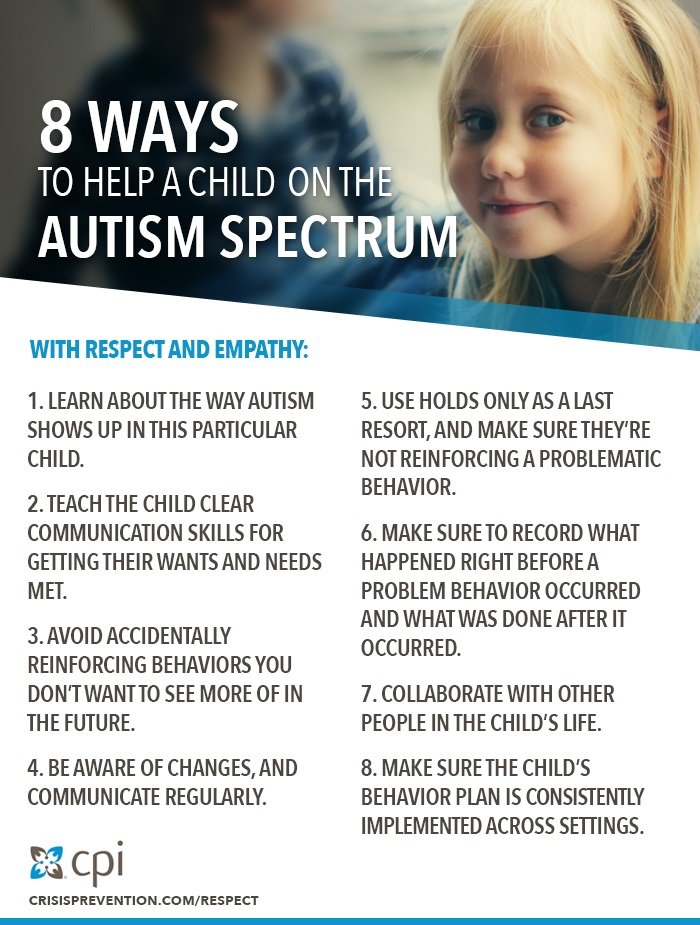

4) Make sure that all caregivers are on the same page. Make sure that parental, educational and support staff beliefs about short-term management of challenging behaviour are looked at and discussed, e. g: when and why we choose confrontational approaches such as physical restraints – and not avoidance strategies.

g: when and why we choose confrontational approaches such as physical restraints – and not avoidance strategies.

Peace of mind is contagious!

People working with stressed children need to be centred and emotionally aware when working with vulnerable groups of people, and able to reflect on how we/they respond to someone in a crisis situation.

It may sound simple, but conflict situations in practice are multifaceted and complex. This is why Pindstrup school regularly has training courses on the subject in order to learn more and to keep the principles fresh in mind. Over the years, the approach has become an implicit part of the school culture.

Vice Principal Lone Bridal observed changes in staff beliefs since the Low Arousal Approach was adopted:

“Today, we talk about children who have difficulties. You would very often hear a teacher say: ‘I think this child seems a little more stressed at the moment, we need to take very good care of him right now’.

Before [Low Arousal], you would hear different narratives about challenging behaviour, and you would see children who were constantly fighting the world, because they were being met in inappropriate ways. At this state, the narratives within the school signal that we understand that these are children with difficulties who need help and support”

For more information on The Low Arousal Approach, please read:

Managing Aggressive Behaviour in Care Settings: Understanding and Applying Low Arousal Approaches

Managing Family Meltdown: The Low Arousal Approach and Autism

If you would like information on how you can bring the Low Arousal Approach training to your area, please contact Maureen Bennie at [email protected] or call 1-866-724-2224.

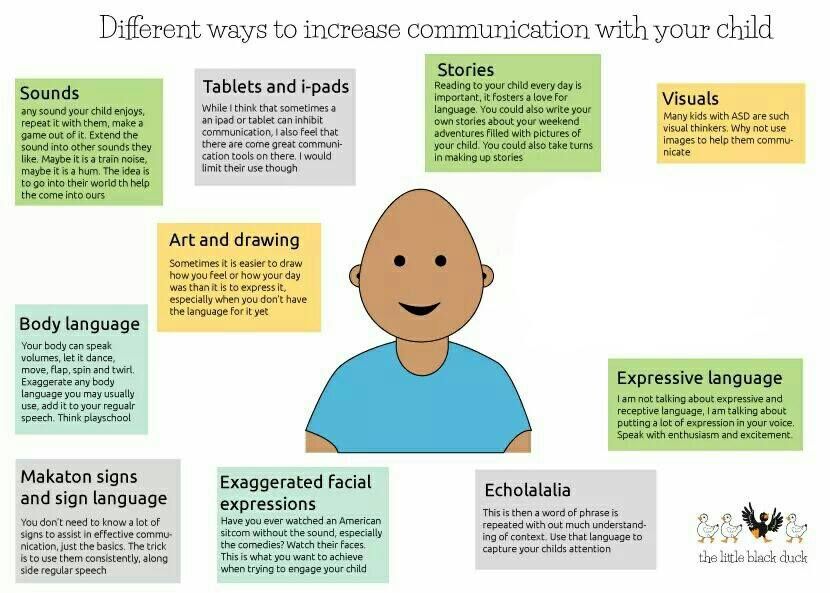

How to attract the attention of a child with autism during class?

07/21/15

Recommendations of a behavioral analyst to keep the attention of a child with autism

Author: Tameik Midose / Tameika MEADOS

Source: I Love ABA

9000 9000 9000

) child (teacher, parent, therapist), he understands how important it is to attract and keep the attention of the child. Even if you started a class with an obedient, quiet and attentive student, there is no guarantee that he will remain the same by the end of the class. ABA instructions may include specific requirements at a fast pace, and if the child is not focused on learning, it can be difficult to assess progress. nine0003

Even if you started a class with an obedient, quiet and attentive student, there is no guarantee that he will remain the same by the end of the class. ABA instructions may include specific requirements at a fast pace, and if the child is not focused on learning, it can be difficult to assess progress. nine0003

Even outside of an ABA session, getting and keeping the attention of a child with autism can be a challenge. When I see non-ABA professionals interacting with children with autism, most often they start bombarding the child with instructions. They may make demands on a child who is absorbed in watching DVDs, sits with his back to them and vocalizes. I do not blame the child for not fulfilling their requirements in such a situation. How can a child fulfill the request "Come to dinner" when he, at best, heard ".. nah"? nine0003

What most adults consider signs of attention (maintaining eye contact, immediate response) is difficult behavior for a child with autism. Self-stimulation can interfere with attention, as can hearing problems. For example, if I'm at a play center with a client and I'm trying to give them instructions, I'll have to compete with the noise of other kids yelling and laughing, the noise of the air conditioner, and the sound effects of the nearest video game machine. It will be difficult for my client to filter out all this noise in order to focus on what I am saying. nine0003

For example, if I'm at a play center with a client and I'm trying to give them instructions, I'll have to compete with the noise of other kids yelling and laughing, the noise of the air conditioner, and the sound effects of the nearest video game machine. It will be difficult for my client to filter out all this noise in order to focus on what I am saying. nine0003

Socialization problems also make it difficult for a child with autism to pay attention during class. Looking directly into my eyes can be very uncomfortable for the child, and if I require him to "look into my eyes", the resulting discomfort will prevent him from concentrating on what I am saying. In other situations, physical proximity to me may be unpleasant for him, and this may make it difficult for him to understand my words. When we are trying to get and keep the attention of a child with autism, we must consider all of these factors. nine0003

It seems to me that everyone already knows this, but just in case, let me remind you: if a person with autism does not look you in the eyes, this does not mean that he does not listen to you. I know that many teachers believe that if a child looks at the floor when they are talking to him, then this is a sign of disrespect. However, a child with autism may look away from you precisely because he is trying to focus on your speech.

I know that many teachers believe that if a child looks at the floor when they are talking to him, then this is a sign of disrespect. However, a child with autism may look away from you precisely because he is trying to focus on your speech.

Here are some attention-getting ideas:

Things to avoid

Do not call your child by name. It's best not to give the child's name at all when you're trying to get their attention during class. Otherwise, you can literally repeat it hundreds of times in two hours. In the end, you just teach the child that his name always means some kind of requirement. Imagine that during work, your boss does nothing but shout your name, and each time it ends up with you having more cases. How quickly do you start to flinch and feel annoyed every time your boss says your name? Pretty fast. So it's very important not to combine the child's name with the job ("Aidan, show me a cup", "Aidan, give me a yellow", "Aidan, how old are you"). nine0003

nine0003

Do not touch the child's face or turn his head. Apart from the fact that this has nothing to do with real attention (the child may turn his face in your direction, but still not look at you), these actions are very unpleasant for the child. Imagine that you are bored while I tell you about my vacation and I grab your chin to get your attention back. Do you like it? I doubt. The child may have completely forgotten about your presence and immersed in self-stimulation, so that a sudden touch on the face or chin can greatly frighten him. nine0003

Don't say "Look at me!" Understand that "Look at me" is not a request for attention. Also, please , don't yell at the child "Look at me!" It's not a way to get attention. Speak in a normal tone, do not raise your voice, use pronounced facial expressions and say something like “Look here” (simultaneously pointing to the educational material).

Do not use the same reminders and prompts. I used to use visual cues to get a child's attention back at the table, especially with very young children. However, such clues can be difficult to generalize or reduce. I'm talking about signs like "Hands on knees, feet on the floor, mouth closed, ready to learn." I suggest not relying on prompts and reminders like these, because they don't teach the child to pay attention, they teach him to depend on your prompts. nine0003

I used to use visual cues to get a child's attention back at the table, especially with very young children. However, such clues can be difficult to generalize or reduce. I'm talking about signs like "Hands on knees, feet on the floor, mouth closed, ready to learn." I suggest not relying on prompts and reminders like these, because they don't teach the child to pay attention, they teach him to depend on your prompts. nine0003

Things to try

Use behavioral impulse. In a nutshell, behavioral impulse means that you allow the person to be successful, and only then present a more difficult task or requirement. So if you are having an ABA session and the child is not paying attention, then give him some simple tasks that he has already fully mastered. This way, the child will have a behavioral cycle - simple (reward) + simple (reward) - before you move on to more difficult tasks, and the child will be more attentive during them. nine0003

Be fun and emotional. The best way to attract attention, of course, depends on the individual characteristics of a particular child. However, with many clients in the past, I have fooled around to the fullest, and we started the session with countdowns, handshakes and legshakes, racing around the table, and so on. For older and more high-functioning children, a choice can be offered (“First do “Where does it fit” or “Play numbers” first?). In this way, the child will participate in the structure of the session, and you will get his attention. nine0003

The best way to attract attention, of course, depends on the individual characteristics of a particular child. However, with many clients in the past, I have fooled around to the fullest, and we started the session with countdowns, handshakes and legshakes, racing around the table, and so on. For older and more high-functioning children, a choice can be offered (“First do “Where does it fit” or “Play numbers” first?). In this way, the child will participate in the structure of the session, and you will get his attention. nine0003

Get motivated. If you have correctly identified what motivates the child, then this will certainly lead to increased attention. If I really need five dollars, and here you come to me with five dollars in your hands, then I will most likely pay great attention to what you tell me. Are you not? Always start with a systematic preference assessment to find out what motivates the child.

Helpful Hint

Attention is a complex skill and should not be assumed by default that a child has it. Perhaps the child simply does not know how and what to focus on during the lesson. In this case, you can use ABA to teach this skill. Here are a few examples of programs that can improve attention during class: imitation, receptive speech, responding to a name, following an object (the child follows the object with his eyes). nine0003

Perhaps the child simply does not know how and what to focus on during the lesson. In this case, you can use ABA to teach this skill. Here are a few examples of programs that can improve attention during class: imitation, receptive speech, responding to a name, following an object (the child follows the object with his eyes). nine0003

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

ABA-therapy and behavior, Methods and treatment

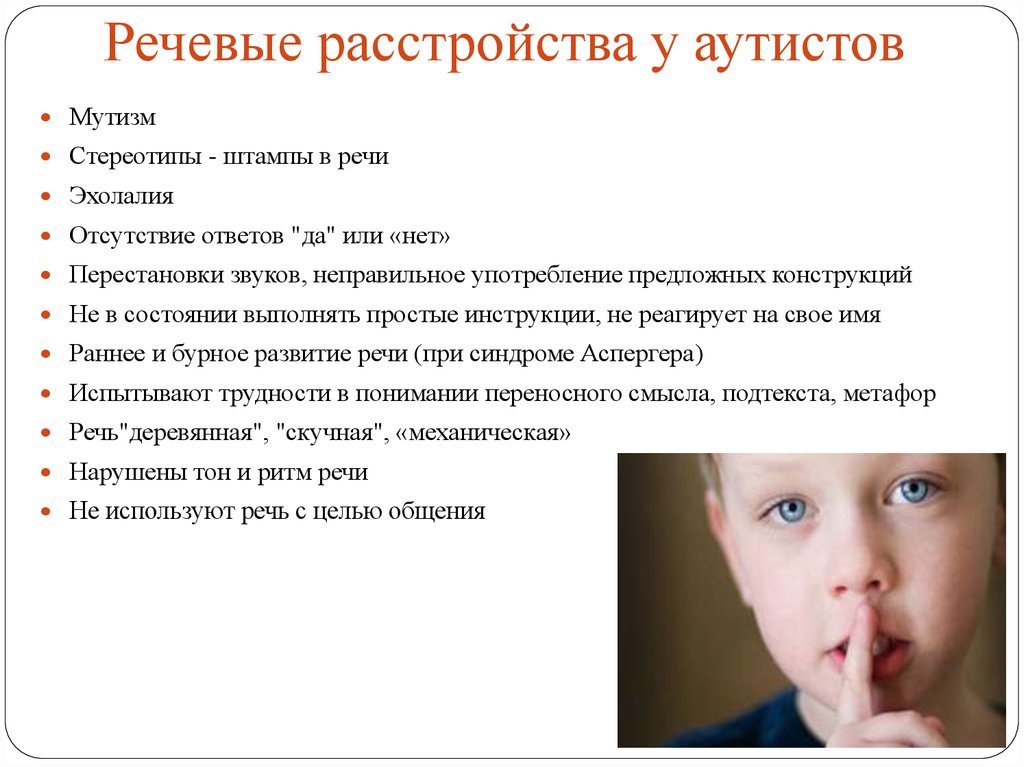

Tantrums in autism: what is the cause and what to do?

6/23/20

Parent's guide on how to distinguish simple "scandals" from a nervous breakdown in autism, and what can be done in each case

Source: Autism Parenting Magazine

All parents experience embarrassment, irritation, and fatigue when their child throws a tantrum. It doesn't matter if a child has a diagnosis or what stage of development he is at, both experienced parents and newcomers are faced with violent emotional outbursts in a child. It's inevitable - if you have a child, you'll deal with behavioral outbursts one way or another.

It doesn't matter if a child has a diagnosis or what stage of development he is at, both experienced parents and newcomers are faced with violent emotional outbursts in a child. It's inevitable - if you have a child, you'll deal with behavioral outbursts one way or another.

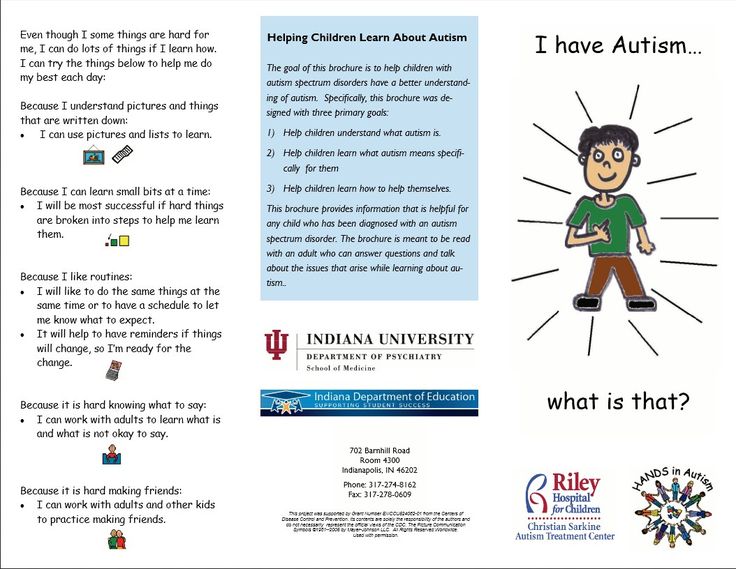

If your child is on the autism spectrum, then you have an additional unique parenting skill - the ability to cope with nervous breakdowns. You cannot always predict what will cause a violent scandal or emotional outburst on any given day or in any given environment. To do this, you will have to be superparents with an infinite set of tools and limitless flexibility and sixth sense. nine0003

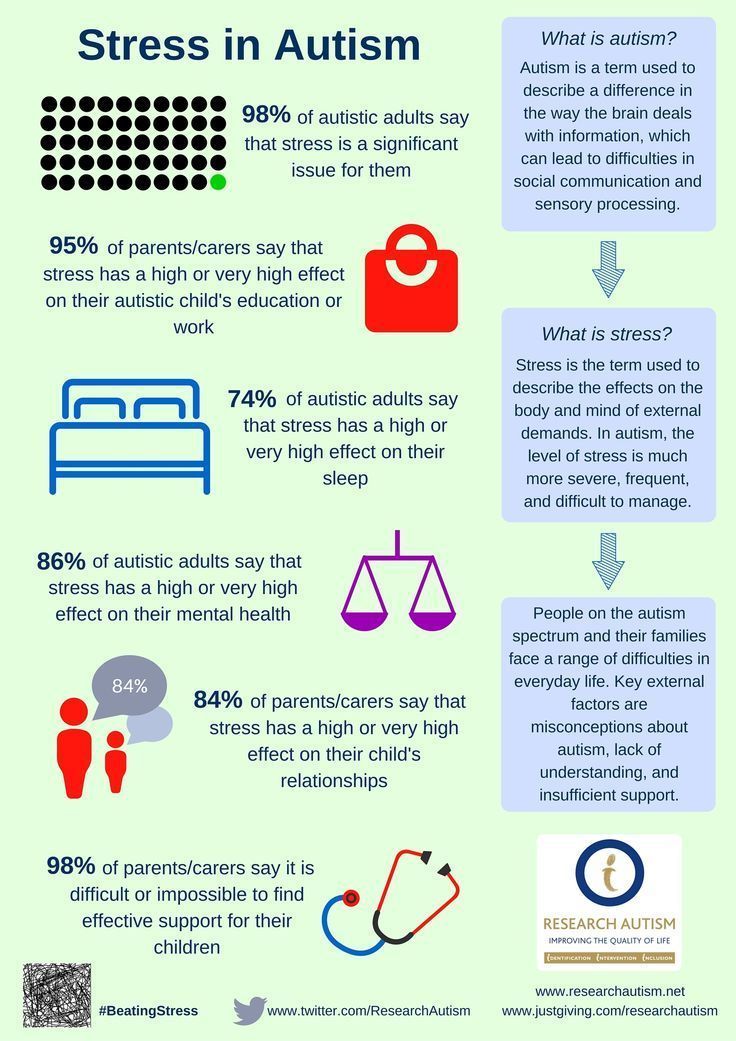

Neither behavioral scandals nor nervous breakdowns look attractive, but in many families of children with autism they happen very often and can be a source of serious stress. It is very important to understand the difference between these two phenomena. Although both may look like a "hysteria," a scandal and a nervous breakdown are not the same thing, and they require completely different approaches.

What is a "scandal"?

Scandal or behavioral outburst usually occurs when a child is denied what he wants or cannot do what he wants to do. nine0003

Parents often face constant scandals at the age of 2 or 3, or during the so-called "crisis of three years", when young children begin to assert their independence. In fact, the “crisis of three years” is a developmental stage that usually takes place between the ages of 1 and 4 years, because the child needs time to develop the necessary motor, speech and thinking skills.

Preschool children are often prone to "throw up scandals" because they lack the skills in the areas needed to cope with a difficult situation on their own. Why is this happening? There are several reasons for this:

- They have a desire to be independent, but lack the motor and cognitive skills (the ability to plan, coordinate, and execute) to actually BECOME independent.

- In addition, their speech skills are just beginning to develop, so it is difficult for a child to express what he wants and what he needs, and such difficulties can drive him crazy.

- The child's prefrontal cortex is still underdeveloped. This is the part of the brain that is responsible for emotional regulation and social behavior. The child literally has no ability to regulate his behavior! nine0003

- As the child begins to understand the world around him more and more, this very world can cause him anxiety. Such anxiety, coupled with insufficient control over the environment, often leads to behavioral outbursts - it is simply difficult for a child to cope with everything that is happening around.

A key feature of such scandals is that this behavior persists and intensifies if you somehow pay attention to the child during the explosion. If you start consistently ignoring the child when he "scandals", the outbursts will subside. nine0003

When a child “scandals”, he retains the ability to control his behavior, this behavior may increase or decrease depending on the behavior of adults around him. The scandal stops when the child gets what he wants, or when he realizes that the outbreak will not lead to the desired result.

If parents "give in" during outbreaks from time to time, children will start arguing again and again, since this behavior has proven effective if they are denied what they want. nine0003

As children mature, they develop self-regulation skills to deal with anxiety and anger. If the "tantrum"-like behavioral outbursts are not appropriate for the child's developmental stage, it can lead to great social and emotional difficulties due to inappropriate behavior.

What is a "nervous breakdown"?

A nervous breakdown occurs when a child loses control of his behavior and can only calm down when he reaches the stage of exhaustion.

A nervous breakdown is a reaction to overload, for example, very often it is a consequence of excessive sensory stimulation. Scandals can lead to nervous breakdowns, so it's often difficult to distinguish between these two behavioral outbursts if you don't understand the child's sensory responses well.

When a person with autism experiences too much stimulation from the environment, it can lead to an overload of the central nervous system, which loses the ability to process incoming information. This is actually a physiological "traffic jam" in the central nervous system, and behavior in response to sensory overload is the problematic behavior of a driver who is stuck in traffic. Imagine that you are calmly driving to your destination, humming your favorite song, and then suddenly the highway is completely up. Now you can’t continue on your way, your expectations of the situation have not been met at all, you are surrounded by huge trucks, you are inhaling exhaust fumes, you are deafened by car horns, and your car windows are in direct sunlight. Anxiety about the situation itself is heightened by all these sensations, and you start sensory overload. The last thing you want is to stay in this traffic jam, but you have no way out. Irritation and overexertion are normal reactions in such a situation. Maybe you turn off the radio, close your eyes, try to take deep breaths to calm down (a socially acceptable desirable behavior). OR you jump out of the car and yell in a fit of rage (unwanted maladaptive behavior).

This is actually a physiological "traffic jam" in the central nervous system, and behavior in response to sensory overload is the problematic behavior of a driver who is stuck in traffic. Imagine that you are calmly driving to your destination, humming your favorite song, and then suddenly the highway is completely up. Now you can’t continue on your way, your expectations of the situation have not been met at all, you are surrounded by huge trucks, you are inhaling exhaust fumes, you are deafened by car horns, and your car windows are in direct sunlight. Anxiety about the situation itself is heightened by all these sensations, and you start sensory overload. The last thing you want is to stay in this traffic jam, but you have no way out. Irritation and overexertion are normal reactions in such a situation. Maybe you turn off the radio, close your eyes, try to take deep breaths to calm down (a socially acceptable desirable behavior). OR you jump out of the car and yell in a fit of rage (unwanted maladaptive behavior). nine0003

nine0003

During times of increased anxiety and stress, the sympathetic part of our autonomic nervous system starts producing the hormone cortisol and triggers the fight or flight response. When people with autism or sensory processing dysfunction experience sensory overload, they are unable to regulate sensory signals from the environment, and their bodies begin to perceive these signals as a huge threat.

In moments of a nervous breakdown, control over behavioral reactions is lost. And it is very important to remember this - you cannot expect logical and rational answers in a situation where the child's body perceives ordinary sensory signals as an attack. nine0003

Because of this difference in control over one's behavior, strategies for a scandal and a nervous breakdown must be very different.

How can scandals be dealt with?

Strategies for dealing with scandals come down to positive behavioral support and the development of alternative behaviors. There are now many books and articles adapted for parents on how to deal with unwanted child behavior. Most of these approaches boil down to three main strategies:

Most of these approaches boil down to three main strategies:

1. Definition of motivation, that is, the purpose of behavior.

It is important to understand that when a child "scandals" this behavior has a specific purpose. Typically, a behavioral scandal serves a child in one of the following ways: to get the attention of other people (for example, parents), to get some objects or activities (that the child wants, but was denied or access to them is delayed), or to avoid something. - something he doesn't like.

Once you understand WHY the child is fighting, you will be able to understand how you can react to it. Recognize the needs of the child, but do not give in to him in response to the scandal. nine0003

2. Encouragement of positive behaviour.

Start "catching" the child when he behaves well. For example, when he does NOT make a fuss in response to small problems, praise him and reward him for good behavior. Depending on what your child prefers, it could be a hug, a high-five, or a good job. This is how you teach your child that he can get your attention not only through "bad" behavior, but also through "good" behavior. Focusing on what the child did right will help the child build on those successes and behave more positively in the future! nine0003

This is how you teach your child that he can get your attention not only through "bad" behavior, but also through "good" behavior. Focusing on what the child did right will help the child build on those successes and behave more positively in the future! nine0003

3. Develop skills for success.

We know that a child's frequent fights can indicate a lack of patience, a lack of a way to communicate one's desires, a lack of knowledge of what behavior is expected in a given situation, an inability to comfort oneself. It is important to look for opportunities to develop these skills in your child and help them be successful. However, it is important to work on these skills every day and NOT when the child is fighting.

Strategies for nervous breakdowns in children with autism

You've probably heard the expression, "If you know one person with autism, then you know one person with autism." Each child with autism responds differently to different situations, has different skill levels, and different sensory, communication and social profiles, so there is no single strategy that will help with any child's breakdown. Below are a few tips and strategies that have helped other parents, but you need to consider how they fit the individual child:

Below are a few tips and strategies that have helped other parents, but you need to consider how they fit the individual child:

1. Visual schedules for the day, social stories, to-do lists, schedules for a specific event or task

We all would like to completely avoid nervous breakdowns, but this is impossible. Instead, strategies that reduce stress and anxiety in everyday life, and therefore reduce the risk of a nervous breakdown, can be very helpful. Visual timetables, social stories, checklists, and other visual support help your child become aware of what is expected of him and what is expected of him. For example, if you are planning a trip to the store, then search the Internet for photos of this particular store, place them in the child’s visual schedule for the day. Or, if you have the opportunity, go to the store without your child and film your trip to the store, then watch the video with your child at home. Or write a social story with illustrations about going to the store, what it is for, and what will happen from the beginning to the end of such an event, and read the story with your child. Such strategies create predictability and a sense of control for the child, which reduces anxiety. Over time, also teach your child “surprises” in the schedule so that he can cope with unexpected events in the usual daily routine. nine0003

Such strategies create predictability and a sense of control for the child, which reduces anxiety. Over time, also teach your child “surprises” in the schedule so that he can cope with unexpected events in the usual daily routine. nine0003

2. Regular "sensory unloading" in the child's schedule.

Regular sensory unloading, the so-called “sensory diet”, is an important component that helps the child regulate his condition during the day. Some parents have found it helpful to prevent breakdowns by scheduling regular "quiet time" for their children, rather than waiting for the day's events to overwhelm them. This is important to take into account, especially if you are planning visits to new and noisy places for the child. Since a nervous breakdown is the result of many different environmental stimuli whose effect "accumulates", it's best to schedule some quiet time with relaxing sensory activities before going out in public with your child. nine0003

3. Knowing the signs of severe stress in a child.

Knowing the signs of severe stress in a child.

Another important strategy is to be aware of the first signs that a child is under severe stress. Does the child press his hands to his ears? Runs out of the room? Repeats "Go away!" or "Let's go home!", or do you notice a sharp increase in repetitive behavior (for example, the child sways, hums under his breath, shakes his arms)? These signs of extreme stress may indicate that the child is being over stimulated and needs your help to regulate before they develop into a full-blown breakdown. nine0003

If the child is unable to speak, or their language skills become unreliable or lost during a nervous breakdown, they will need some form of non-technological alternative communication, such as a “choice board” where the child points to one of the images from a few to explain what he wants. The child may use alternative communication to let you know when he needs to leave the situation or use a different strategy to bounce back. nine0003

nine0003

Some children need a predetermined sign that both of you understand (hand gesture, signal word) to communicate sensory overload and thus ask for help.

4. Finding a quiet and safe space.

If you have a nervous breakdown, it is important to find a quiet and safe place. This may mean that you need to leave a place that causes overstimulation (for example, a store). The safe space may also include techniques that reduce sensory information. Remain calm, keep speech to a minimum and, if possible, be silent, offer the child deep pressure, such as hugs, to calm down. If the child is likely to run away or his behavior could become dangerous to himself or others, he may need to be restrained for safety. nine0003

Outsiders in public places may not understand the situation and their behavior may exacerbate the crisis. It is helpful to make special cards in case of a nervous breakdown - these are cards made by parents that explain the diagnosis of the child and the reasons for his cries, why he is held, or other behavior that may alert other people. When you're focusing on a child's breakdown, a ready-made card that can be held out silently can save you from unnecessary explanations or false accusations of abuse. nine0003

When you're focusing on a child's breakdown, a ready-made card that can be held out silently can save you from unnecessary explanations or false accusations of abuse. nine0003

5. Remember to breathe.

This is not so much a strategy for the child as it is for you. Breathe, try not to take what is happening with the child at your own expense. As difficult as it may be, try to notice your emotional reactions (anger, embarrassment, sadness). Remind yourself that your child has lost the ability to control his reactions at the moment. By staying calm and in control of yourself, you are already doing a lot to help your child get through this difficult moment. nine0003

6. Portable sensory set for the prevention of nervous breakdowns.

Here are some examples of what parents carry outside the home to prevent a nervous breakdown or to help their child calm down after one.

- Sunglasses (if you are sensitive to bright light).

- Earmuffs (to reduce noise or to distract the child with music).

- Wide-brimmed hat or cap (as a way to distance yourself from social interaction and block out the light from above). nine0003

- Snack that can be crunched or chewed for a long time (stimulation of the muscles in the mouth can have a calming effect, and hungry children become more irritable).

- Unscented wet wipes (to help with tactile sensitivity if the child accidentally touches something that irritates him).

- Hand lotion with a favorite scent (may help reduce environmental odors as well as provide a soothing effect). nine0003

- A "sensory" toy is a toy that can be used to make repetitive, simple movements that can have a calming effect.

- Communication board with pictures or printed words, eg "I need a break", "Let's go", "Too loud".

- Explanation cards or other way to let strangers know what's going on and why you're reacting the way you do.

The main thing to remember is that nervous breakdowns due to overload are important to distinguish from scandals when a child tries to get his way, since they require different approaches. Both phenomena are extremely unpleasant for all involved, so it is important to put as much effort as possible into actively teaching the child how he can regulate his emotional state. Try to find strategies that work best for your child. Just remember to breathe and stay calm. nine0003

Both phenomena are extremely unpleasant for all involved, so it is important to put as much effort as possible into actively teaching the child how he can regulate his emotional state. Try to find strategies that work best for your child. Just remember to breathe and stay calm. nine0003

See also:

Autistic Meltdown or Temper Tantrum? by Judy Endow, MSW.” Ollibean. N.p., 10 Nov. 2016. Web. 25 May 2017.

“26 Sensory Integration Tools for Meltdown Management – Friendship Circle – Special Needs Blog.” Friendship Circle - Special Needs Blog. N.p., 18 Nov. 2015. Web. 25 May 2017.

Bennett, David D. “Decreasing Tantrum/Meltdown Behaviors of School Children with High Functioning Autism through Parent Training.” social science. N.p., 04 Feb. 2014. Web. May 25, 2017.

Caroline Miller. “Why Do Kids Have Tantrums and Meltdowns?” Child Mind Institute. N.p., n.d. Web. May 25, 2017.

Morin, Amanda. “The Difference Between Tantrums and Sensory Meltdowns.