How to parent a child with trauma

Parenting After Trauma: Understanding Your Child's Needs

Log in | Register

Family Life

Family Life

Listen

Español

Text Size

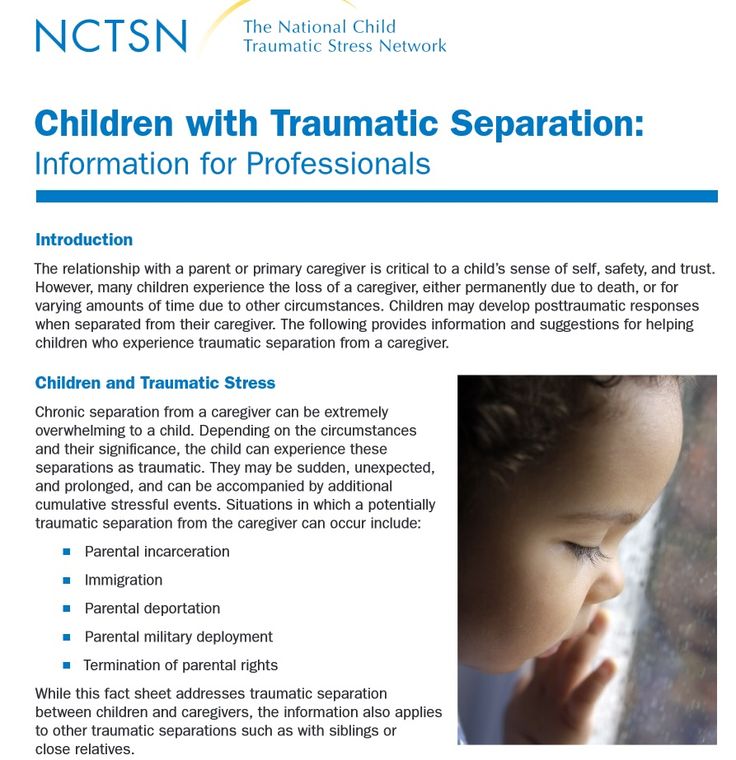

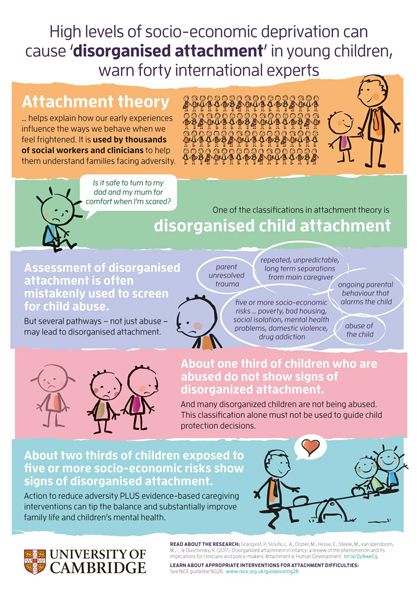

All children need homes that are safe and full of love. This is especially true for children who have experienced severe trauma. Early, hurtful experiences can cause children to see the world differently and react in different ways. Some children who have been adopted or placed into foster care need help to cope with what happened to them in the past. Knowing what experts say about early trauma can help you work with your child.

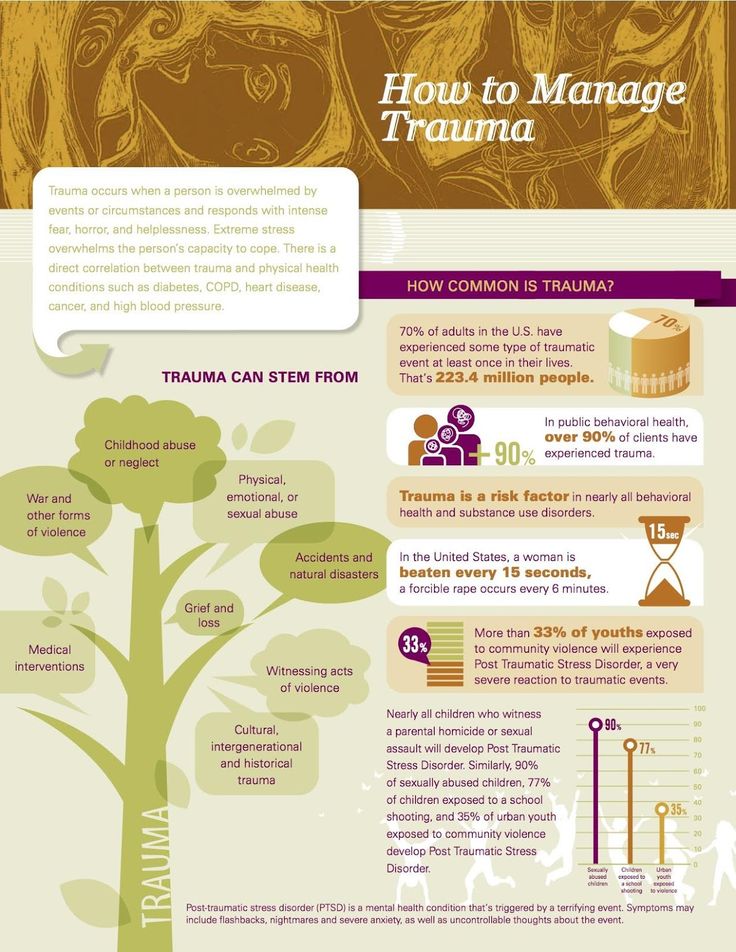

Forms of trauma

An event is traumatic when it threatens the child or someone the child depends on for safety and love. Abuse may be traumatic, but trauma may take many forms. It includes:

The body's fight or flight response

A frightened child may feel out-of-control and helpless. When this happens, the body's protective reflexes set off a “fight or flight" panic response that can make a child's heart pound, blood pressure rise and lead to emotional outbursts or aggressive behavior.

Some children are more sensitive than others. What is traumatic for one child may not be seen as traumatic for another child. Fear responses are based on a child's sense of what is frightening. It might be hardest for children who are neglected, even if they don't have signs of physical injury like bruises. These children worry about having their basic needs met, like food, love, or safety.

Trauma has more severe effects when...

it happens again and again.

different stresses add up.

it happens to a younger child.

the child has fewer social supports (healthy personal relationships).

the child has fewer coping skills (language skills, intelligence, good health, and self-esteem).

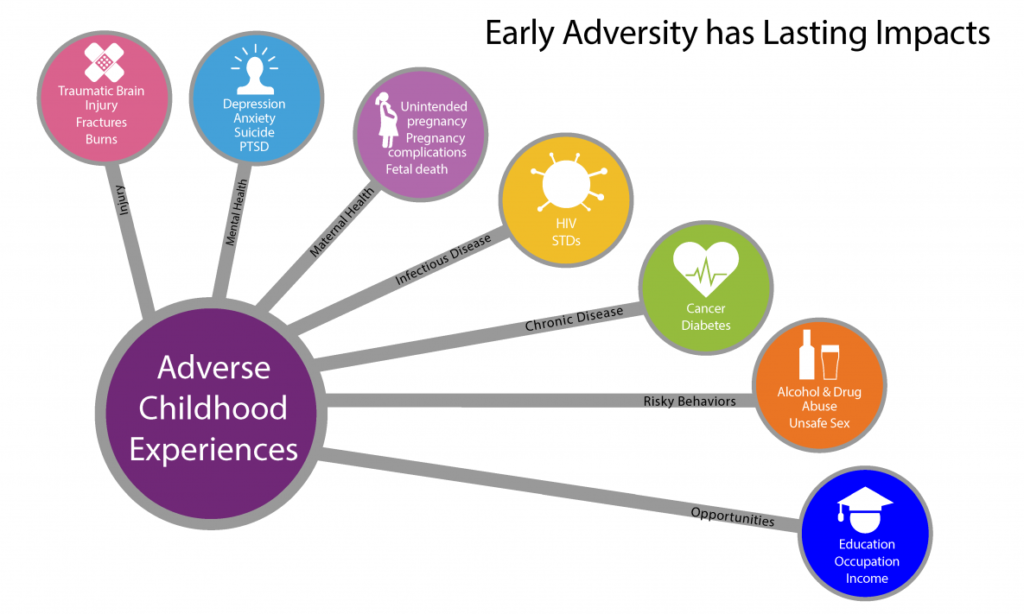

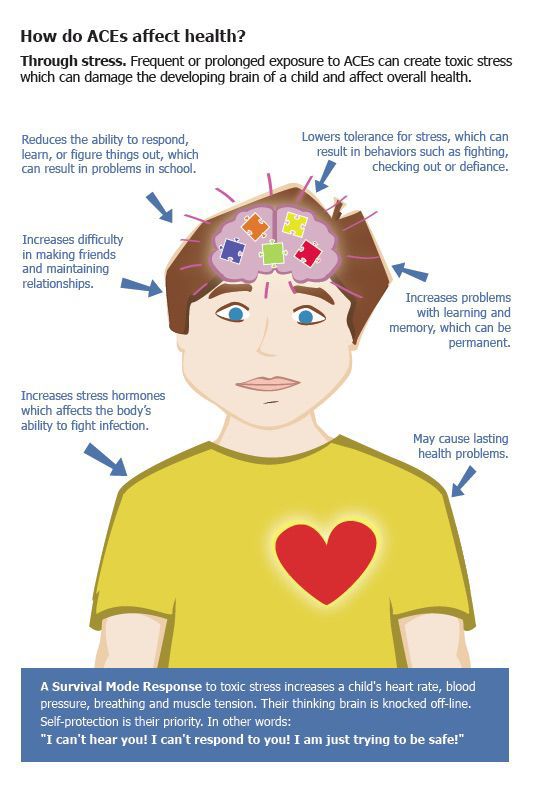

How the brain reacts to trauma

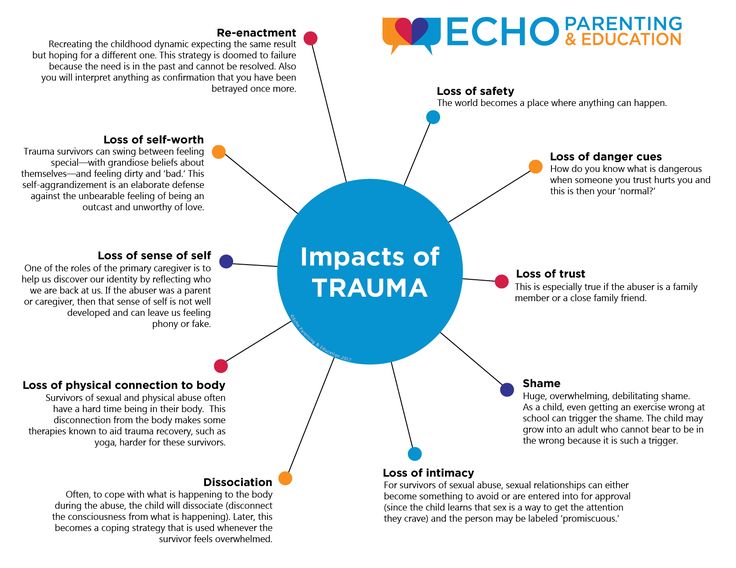

When something scary happens, the brain makes sure you do not forget it. Traumatic events are remembered by the body, not just through memories. Traumas are experienced as a pattern of sensations with sounds, smells, and feelings mixed together. They can rush into the present without a child realizing they are experiencing a memory, and they can be remembered that way, too. Any one of these things can make a child feel like the whole event is happening again. These reminders or sensations are called "triggers."

Triggers

Triggers can be smells or sounds. They can be places, postures, or tones of voice. Even emotions can be a trigger. For example, being anxious about school may be related to being anxious about violence at home. This can cause dramatic and unexpected behaviors like physical aggression or withdrawal.

Triggers can be hard to identify, even for a child. If a child knows what a trigger is, the child will try hard to avoid it.

Remembering a traumatic event can cause some of the original fight-or-flight reaction to return. This might look like a “tantrum" or overreaction. Sometimes anxiety can cause a child to “freeze" or blankly stare as if they are in their own world. This may look like defiance or “zoning out." A child who sees the world as a place full of danger may do this. Many children who have been abused or neglected go through life always on edge, and have difficulty maintaining control of their emotions because their body is ready to freeze, flee or run away from what frightens them, or to fight in self-defense.

Associated disorders

Being ready to flee or fight shows up in many ways. Children who are always on guard may have trouble concentrating. This is called “hyperarousal" or “hypervigilance." These effects of past trauma can be easily confused with hyperactivity and inattention, classic signs of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and children may incorrectly receive this diagnosis if caregivers and doctors do not realize the effects of trauma on development.

Children who have experienced trauma may also be overwhelmed with emotions and have trouble with the unexpected. Their need for control may be seen as “manipulative" or as always wanting things done their way. Going from one activity to another may be hard. When these aggressive responses are extreme and trauma reactions are not considered, it can be labeled "oppositional defiant disorder" or "intermittent explosive disorder." These terms do not recognize that a child's reactions might have been appropriate at the time they experienced a trauma, though they may be no longer appropriate now.

What foster and adoptive parents can do to help

Children who have been adopted or are in foster care have often suffered trauma. They may see and respond to threats that others do not, and their brains may always be “on guard." Many children have never learned to depend on consistent, reliable adults, and usual parenting practices may not work. It can be hard to remember that these emotions may happen with you, but are not about you. These strong feelings are in response to the traumas that happened before. Some helpful tips:

These strong feelings are in response to the traumas that happened before. Some helpful tips:

Learning to trust after trauma

All newborn babies are helpless and dependent. Consistent and loving caregivers help babies learn to trust others, and to feel valuable and worthy of love. This is important for healthy development. We cannot thrive without the help of others. This is most true when times are hard.

Supportive, caring adults can help a child recover from traumatic experiences. Some children may not have had adults help them before, and may not know that adults can help or that they can be trusted. They may resist the help of others. Not trusting adults can be mistaken as disrespect for authority. This can cause problems at home and school. It can also make learning harder.

It can be hard to tell who is affected by trauma. Mistreated children may withdraw from people and seem

shy and fearful. They may also be very friendly with everyone they meet. They may cross personal boundaries and put themselves at risk for more abuse. They are choosing between “trust no one" and “trust everybody, but not very much."

They may also be very friendly with everyone they meet. They may cross personal boundaries and put themselves at risk for more abuse. They are choosing between “trust no one" and “trust everybody, but not very much."

Remember

Children are remarkedly resilient and do the best they can with what they have been given. It is our job to provide them with the tools they need and to guide them as they grow. It may be a slow process with many setbacks, but the rewards are worth the effort. By understanding that your child's past experiences have affected the way they see and responds to their world, you have taken the first steps to building a safer, healthier world for you child.

More information

- Building Resilience

-

Let's Talk About Adoption

-

Thinking About Adoption: FAQs

- How Pediatricians Can Support Families of Children Who Are Adopted

- Last Updated

- 11/23/2020

- Source

- Adapted from Parenting After Trauma: Understanding Your Child's Needs (© 2016 American Academy of Pediatrics and Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption)

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

Helping Children Cope With Trauma

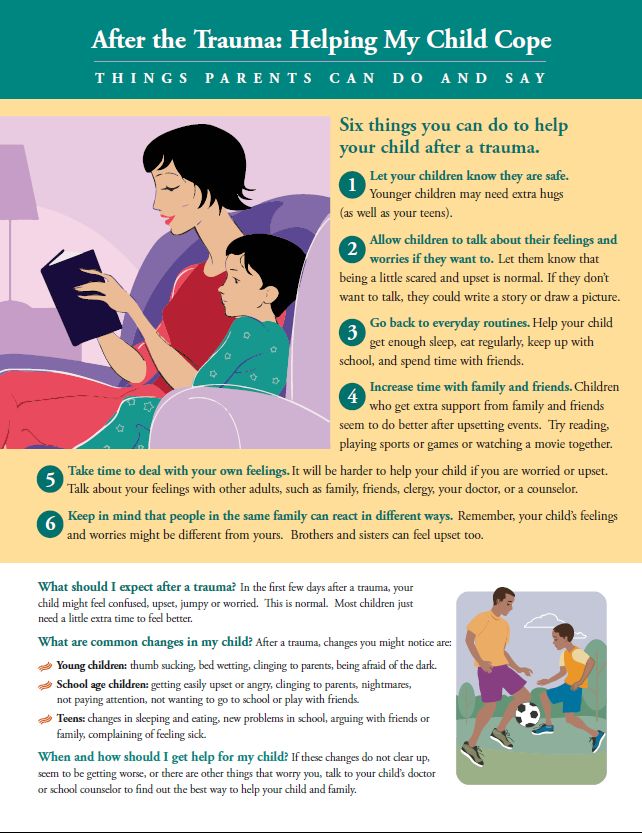

In the wake of a traumatic event, your comfort, support and reassurance can make children feel safe, help them manage their fears, guide them through their grief, and help them recover in a healthy way. This guide was assembled by psychiatrists, psychologists and mental health experts who specialize in crisis situations. It offers simple tips on what to expect, what to do and what to look out for. If you or your children require assistance from a mental health professional, do not hesitate to ask a doctor or other health care provider for a recommendation.

Tips for Helping Children After the Event

- Make your child feel safe. All children, from toddlers to teens, will benefit from your touch—extra cuddling, hugs or just a reassuring pat on the back. It gives them a feeling of security, which is so important in the aftermath of a frightening or disturbing event.

For specific information on what to do and say, see the age-by-age-guide.

For specific information on what to do and say, see the age-by-age-guide. - Act calm. Children look to adults for reassurance after traumatic events have occurred. Do not discuss your anxieties with your children, or when they are around, and be aware of the tone of your voice, as children quickly pick up on anxiety.

- Maintain routines as much as possible. Amidst chaos and change, routines reassure children that life will be okay again. Try to have regular mealtimes and bedtimes. If

you are homeless or temporarily relocated, establish new routines. And stick with the same family rules, such as ones about good behavior. - Help children enjoy themselves. Encourage kids to do activities and play with others. The distraction is good for them, and gives them a sense of normalcy.

- Share information about what happened. It’s always best to learn the details of a traumatic event from a safe, trusted adult. Be brief and honest, and allow children to ask questions. Don’t presume kids are worrying about the same things as adults.

- Pick good times to talk. Look for natural openings to have a discussion.

- Prevent or limit exposure to news coverage. This is especially critical with toddlers and school-age children, as seeing disturbing events recounted on TV or in the newspaper or listening to them on the radio can make them seem to be ongoing. Children who believe bad events are temporary can more quickly recover from them.

- Understand that children cope in different ways. Some might want to spend extra time with friends and relatives; some might want to spend more time alone. Let your child know it is normal to experience anger, guilt and sadness, and to express things in different ways—for example, a person may feel sad but not cry.

- Listen well. It is important to understand how your child views the situation, and what is confusing or troubling to him or her. Do not lecture—just be understanding. Let kids know it is OK to tell you how they are feeling at any time.

- Help children relax with breathing exercises.

Breathing becomes shallow when anxiety sets in; deep belly breaths can help children calm down. You can hold a feather or a wad of cotton in front of your child’s mouth and ask him to blow at it, exhaling slowly. Or you can say, “Let’s breathe in slowly while I count to three, then breathe out while I count to three.” Place a stuffed animal or pillow on your child’s belly as he lies down and ask him to breathe in and out slowly and watch the stuffed animal or pillow rise and fall.

Breathing becomes shallow when anxiety sets in; deep belly breaths can help children calm down. You can hold a feather or a wad of cotton in front of your child’s mouth and ask him to blow at it, exhaling slowly. Or you can say, “Let’s breathe in slowly while I count to three, then breathe out while I count to three.” Place a stuffed animal or pillow on your child’s belly as he lies down and ask him to breathe in and out slowly and watch the stuffed animal or pillow rise and fall. - Acknowledge what your child is feeling. If a child admits to a concern, do not respond, “Oh, don’t be worried,” because he may feel embarrassed or criticized. Simply confirm what you are hearing: “Yes, I can see that you are worried.”

- Know that it’s okay to answer, “I don’t know.” What children need most is someone whom they trust to listen to their questions, accept their feelings, and be there for them. Don’t worry about knowing exactly the right thing to say — after all, there is no answer that will make everything okay.

Download a PDF version of this guide

Tips for Helping Kids Recover in a Healthy Way

- Realize that questions may persist. Because the aftermath of a disaster may include constantly changing situations, children may have questions on more than on occasion. Let them know you are ready to talk at any time. Children need to digest information on their own timetable and questions might come out of nowhere.

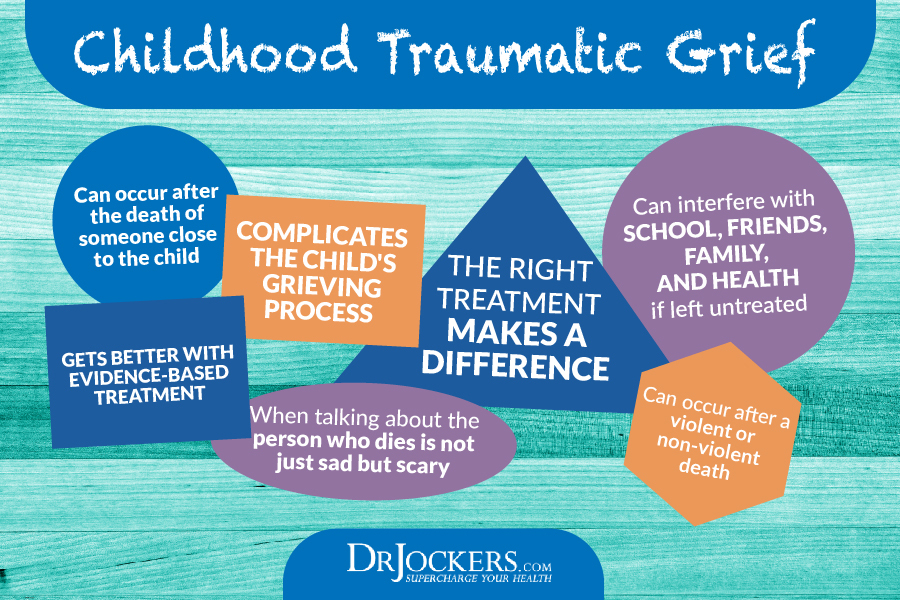

- Encourage family discussions about the death of a loved one. When families can talk and feel sad together, it’s more likely that kids will share their feelings.

- Do not give children too much responsibility. It is very important not to overburden kids with tasks, or give them adult ones, as this can be too stressful for them. Instead, for the near future you should lower expectations for household duties and school demands, although it is good to have them do at least some chores.

- Give special help to kids with special needs.

These children may require more time, support and guidance than other children. You might need to simplify the language you use, and repeat things very often. You may also need to tailor information to your child’s strength; for instance, a child with language disability may better understand information through the use of visual materials or other means of communication you are used to.

These children may require more time, support and guidance than other children. You might need to simplify the language you use, and repeat things very often. You may also need to tailor information to your child’s strength; for instance, a child with language disability may better understand information through the use of visual materials or other means of communication you are used to. - Watch for signs of trauma. Within the first month after a disaster it is common for kids to seem mostly okay. After that, the numbness wears off and kids might experience more symptoms — especially children who have witnessed injuries or death, lost immediate family members, experienced previous trauma in their lives or who are not resettled in a new home.

- Know when to seek help. Although anxiety and other issues may last for months, seek immediate help from your family doctor or from a mental health professional if they do not abate or your child starts to hear voices, sees things that are not there, becomes paranoid, experiences panic attacks, or has thoughts of wanting to harm himself or other people.

- Take care of yourself. You can best help your child when you help yourself. Talk about concerns with friends and relatives; it might be helpful to form a support group. If you belong to a church or community group, keep participating. Try to eat right, drink enough water, stick to exercise routines, and get enough sleep. Physical health protects against emotional vulnerability. To reduce stress, do deep breathing. If you suffer from severe anxiety that interferes with your ability to function, seek help from a doctor or mental health professional and if you don’t have access to one, talk with a religious leader. Recognize your need for help and get it. Do it for your child’s sake, if for no other reason.

Download a PDF version of this guide

How to Help Children Ages 0-2

Infants sense your emotions, and react accordingly. If you are calm, your baby will feel secure. If you act anxious and overwhelmed, your baby may react with fussing, have trouble being soothed, eat or sleep irregularly or may act withdrawn.

What you can do:

- Try your best to act calm. Even if you are feeling stressed or anxious, talk to your baby in a soothing voice.

- Respond consistently to your baby’s needs. The developmental task of this age is to trust caregivers so kids can develop a strong, healthy attachment.

- Continue nursing if you have been breastfeeding. Although there is a myth that when a mother experiences shock her breast milk turns bad and could cause the baby to be “slow” or have learning disorders, that is not true. It is important to continue nursing your baby to keep her healthy and connected with you. You need to stay healthy to breastfeed, so do your best to eat enough and drink water.

- Look into your baby’s eyes. Smile at her. Touch her. Research shows that eye contact, touch and simply being in a mother’s presence helps keep a baby’s emotions balanced.

Download a PDF version of this guide

How to Help Children Ages 2-5

At this age, although children are making big developmental advances, they still depend on parents to nurture them. As with babies, they typically respond to situations according to

As with babies, they typically respond to situations according to

how parents react. If you are calm and confident, your child will feel more secure. If you act anxious or overwhelmed, your child may feel unsafe.

Typical reactions of children ages 2 to 5:

- Talking repeatedly about the event or pretending to “play” the event

- Tantrums or irritable outbursts

- Crying and tearfulness

- Increased fearfulness—often of the dark, monsters, or being alone

- Increased sensitivity to sounds like thunder, wind, and other loud noises

- Disturbances in eating, sleeping and toileting

- Believing that the disaster can be undone

- Excessive clinging to caregivers and trouble separating

- Reverting to early behavior like baby talk, bed-wetting and thumb-sucking

What you can do:

- Make your child feel safe. Hold, hug and cuddle your child as much as possible. Tell her you will take care of her when she feels sad or scared.

With children who are learning to talk, use simple phrases such as “Mommy’s here.”

With children who are learning to talk, use simple phrases such as “Mommy’s here.” - Watch what you say. Little children have big ears and may pick up on your anxiety, misinterpret what they hear, or be frightened unnecessarily by things they do not understand.

- Maintain routines as much as possible. No matter what your living situation, do your best to have regular mealtimes and bedtimes. If you are homeless or have been relocated, create new routines. Try to do the things you have always done with your children, such as singing songs or saying prayers before they go to sleep.

- Give extra support at bedtime. Children who have been through trauma may become anxious at night. When you put your child to bed, spend more time than usual talking or telling stories. It’s okay to make a temporary arrangement for young children to sleep with you, but with the understanding that they will go back to normal sleeping arrangements at a set future date.

- Do not expose kids to the news.

Young children tend to confuse facts with fears. They may not realize that the images they see on the news aren’t happening again and again. They should also not listen to the radio.

Young children tend to confuse facts with fears. They may not realize that the images they see on the news aren’t happening again and again. They should also not listen to the radio. - Encourage children to share feelings. Try a simple question such as, “How are you feeling today?” Follow any conversations about the recent event with a favorite story or a family activity to help kids feel more safe and calm.

- Enable your child to tell the story of what happened. This will help her make sense of the event and cope with her feelings. Play can often be used to help your child frame the story and tell you about the event in her own words.

- Draw pictures. Young children often do well expressing emotions with drawing. This is another opportunity to provide explanations and reassurance. To start a discussion, you may comment on what a child has drawn.

- If your child acts out it may be a sign she needs extra attention. Help her name how she feels: Scared? Angry? Sad? Let her know it is okay to feel that way, then show her the right way to behave—you can say, “It’s okay to be angry, but it is not okay to hit your sister.

”

” - Get kids involved in activities. Distraction is a good thing for kids at this age. Play games with them, and arrange for playtime with other kids.

- Talk about things that are going well. Even in the most trying times, it’s important to identify something positive and express hope for the future to help your child recover. You can say something like, “We still have each other. I am here with you, and I will stay with you.” Pointing out the good will help you feel better, too.

How to help kids ages 2 to 5 cope with the death of a loved one:

- Speak to them at their level. Use similar experiences to help children understand, such as the death of a pet or changes in flowers in the garden.

- Provide simple explanations. For example, “When someone dies, we can’t see them anymore but we can still look at them in pictures and remember them.”

- Reassure your children. They might feel what happened is their fault, somehow; let them know it is not.

- Expect repeated questions. That is how young children process information.

Download a PDF version of this guide

How to Help Children Ages 6-11

At this age, children are more able to talk about their thoughts and feelings and can better handle difficulties, but they still look to parents for comfort and guidance. Listening to them demonstrates your commitment. When scary things happen, seeing that parents can still parent may be the most reassuring thing for a frightened child.

Typical reactions of children ages 6 to 11:

- Anxiety

- Increased aggression, anger and irritability (like bullying or fighting with peers)

- Sleep and appetite disturbances

- Blaming themselves for the event

- Moodiness or crying

- Concerns about being taken care of

- Fear of future injury or death of loved ones

- Denying the event even occurred

- Complaints about physical discomfort, such as stomachaches, headaches, and lethargy, which may be due to stress

- Repeatedly asking questions

- Refusing to discuss the event (more typical among kids ages 9 to 11)

- Withdrawal from social interactions

- Academic problems: Trouble with memory and concentration at school, refusing to attend

What you can do to help:

-

- Reassure your child that he is safe.

Children this age are comforted by facts. Use real words, such as hurricane, earthquake, flood, aftershock. For kids this age, knowledge is empowering and helps relieve anxiety.

Children this age are comforted by facts. Use real words, such as hurricane, earthquake, flood, aftershock. For kids this age, knowledge is empowering and helps relieve anxiety. - Keep things as “normal” as possible. Bedtime and mealtime routines help kids feel safe and secure. If you are homeless or have been relocated, establish different routines and give your child some choice in the matter—for example, let her choose which story to tell at bed- time. This gives a child a sense of control during an uncertain time.

- Limit exposure to TV, newspapers and radio. The more bad news school-age kids are exposed to, the more worried they will be. News footage can magnify the trauma of the event, so when a child does watch a news report or listen to the radio, sit with him so you can talk about it afterward. Avoid letting your child see graphic images.

- Spend time talking with your child. Let him know that it is okay to ask questions and to express concerns or sadness.

One way to encourage conversation is to use family time (such as mealtime) to talk about what is happening in the family as well as in the community. Also ask what his friends have been saying, so you can make sure to correct any misinformation.

One way to encourage conversation is to use family time (such as mealtime) to talk about what is happening in the family as well as in the community. Also ask what his friends have been saying, so you can make sure to correct any misinformation. - Answer questions briefly but honestly. After a child has brought something up, first ask for his ideas so you can understand exactly what the concern is. Usually children ask a question because they are worried about something specific. Give a reassuring answer. If you do not know an answer to a question, it is okay to say, “I don’t know.” Do not speculate or repeat rumors.

- Draw out children who do not talk. Open a discussion by sharing your own feelings—for example, you could say, “This was a very scary thing, and sometimes I wake up in the night because I am thinking about it. How are you feeling?” Doing this helps your child feel he is not alone in his concerns or fears. However, do not give a lot of detail about your own anxieties.

- Keep children busy. Daily activities, such as playing with friends or going to school, may have been disrupted. Help kids think of alternative activities and organize playgroups with other parents.

- Calm worries about friends’ safety. Reassure your children that their friends’ parents are taking care of them just as they are being cared for by you.

- Talk about community recovery. Let children know that things are being done to keep them safe, or restore electricity and water, and that government and community groups are helping, if applicable.

- Encourage kids to lend a hand. This will give them a sense of accomplishment and purpose at a time when they may feel helpless. Younger children can do small tasks for you; older ones can contribute to volunteer projects in the community

- Reassure your child that he is safe.

- Find the hope. Children need to see the future to recover. Kids this age appreciate specifics. For example, in the event of a natural disaster, you could say: “People from all over the country are sending medical supplies, food, and water.

They’ve built new places where people who are hurt will be taken care of, and they will build new homes. It’ll be very hard like this only for just a little while.”

They’ve built new places where people who are hurt will be taken care of, and they will build new homes. It’ll be very hard like this only for just a little while.”

How to help kids ages 6 to 11 cope with the death of a loved one:

- Find out what your child is thinking. Ask questions before you make assumptions about what your child wants to know. For example, you can say, “It made me so upset when grandma died. What about you? It’s hard to think about, isn’t it?”

- Use real words. Avoid euphemisms for death like “He went to a better place.” School-age children are easily confused by vague answers. Instead, you can say, “Grandma has died, she is not coming back, and it is okay to feel sad about that.”

- Be as concrete as possible. Use simple drawings to describe things such as the body and injuries.

- Inform your child. Let her know that anger and sadness are typical, and that if she avoids feelings she may feel worse later on.

- Prepare your child for anticipated changes in routines or household functions.

Talk about what the changes will mean for her.

Talk about what the changes will mean for her. - Reassure your child. Help her understand it is okay, and normal, to have trouble with school, peers, and family during this time.

- Encourage meaningful memorializing. Pray together as a family and take your child with you to church to light a candle. Your child might also want to write a letter to the deceased person or draw a picture you can hang up.

- Be patient. Kids up to age 11 may think death is reversible, and can have trouble accepting the fact that the person may not return. You might need to say repeatedly, “He died and is not coming back, and I am sad.”

Download a PDF version of this guide

How to Help Children Ages 12-18

Adolescence is already a challenging time for young people, who have so many changes happening in their bodies. They struggle with wanting more independence from parents, and have a tendency to feel nothing can harm them. Traumatic events can make them feel out of control, even if they act as if they are strong. They will also feel bad for people affected by the disaster, and have a strong desire to know why the event occurred.

They will also feel bad for people affected by the disaster, and have a strong desire to know why the event occurred.

Typical reactions of children ages 12 to 18:

- Avoidance of feelings

- Constant rumination about the disaster

- Distancing themselves from friends and family

- Anger or resentment

- Depression, and perhaps expression of suicidal thoughts

- Panic and anxiety, including worrying about the future

- Mood swings and irritability

- Changes in appetite and/or sleep habits

- Academic issues, such as trouble with memory and concentration, and/or refusing to attend school

- Participation in risky or illegal behavior, like drinking alcohol

What you can do:

- Make your teen feel safe again. Adolescents do not like to show vulnerability; they may try to act as if they are doing fine even though they are not. While they may resist hugs, your touch can help them feel secure. You can say something like, “I know you’re grown now, but I just need to give you a hug.

”

” - Help teens feel helpful. Give them small tasks and responsibilities in the household, then praise them for what they have done and how they have handled themselves.

Do not overburden teens with too many responsibilities, especially adult-like ones, as that will add to their anxiety. - Open the door for discussion. It’s very typical for teens to say they don’t want to talk. Try to start a conversation while you are doing an activity together, so that the conversation does not feel too intense or confrontational.

- Consider peer groups. Some teenagers may feel more comfortable talking in groups with their peers, so consider organizing one. Also encourage conversation with other trusted adults, like a relative or teacher.

- Limit exposure to TV, newspapers and radio. While teens can better handle the news than younger kids, those who are unable to detach themselves from TV or the radio may be trying to deal with anxiety in unhealthy ways. In any case, talk with your teen about the things she has seen or heard.

- Help your teen take action. Kids this age will want to help the community. Find appropriate volunteer opportunities.

- Be aware of substance abuse. Teens are particularly at risk for turning to alcohol or drugs to numb their anxiety. If your teen has been behaving secretively or is seemingly drunk or high, get in touch with a doctor. And talk to your teen in a kind way. For example, “People often drink or use drugs after a disaster to calm themselves or forget, but it can also cause more problems. Some other things you can do are take a walk, talk to me or your friends about how you feel, or write about your hopes for a better future.”

How to help kids ages 12 to 18 cope with the death of a loved one:

- Be patient. Teens may have a fear of expressing emotions about death. Encourage them to talk by saying something like, “I know it is horrible that grandma has died. Experts say it’s good to share our feelings. How are you doing?”

- Be very open. Discuss the ways you feel the death may be influencing her behavior.

- Be flexible. It is okay, at this time, to have a little more flexibility with rules and academic and behavioral expectations.

- Memorialize meaningfully. Pray together at home, let your teen light a candle at church, and include her in memorial ceremonies. She might also appreciate doing a private family tribute at home.

Download a PDF version of this guide

What Teachers Can Do to Help Students

- Resume routine as much as possible. Children tend to function better when they know what to expect. Returning to a school routine will help students feel that the troubling events have not taken control over every aspect of their daily lives. Maintain expectations of students. It doesn’t need to be 100%, but needing to do some home- work and simple classroom tasks is very helpful.

- Be aware of signs that a child may need extra help. Students who are unable to function due to feelings of intense sadness, fear or anger should be referred to a mental health professional.

Children may have distress that is manifested as physical ailments, such as head- aches, stomachaches, or extreme fatigue.

Children may have distress that is manifested as physical ailments, such as head- aches, stomachaches, or extreme fatigue. - Help kids understand more about what happened. For example, you can mention the various kinds of help coming in, and provide positive coping ideas.

- Consider a memorial. Memorials are often helpful to commemorate people and things that were lost. School memorials should be kept brief and appropriate to the needs and age range of the general school community. Children under four may not have the attention span to join in. A known caregiver, friend, or relative should be the child’s companion during funeral or memorial activities.

- Reassure children that school officials are making sure they are safe. Children’s fears abate when they know that trusted adults are doing what they can to take care of them.

- Stay in touch with parents. Tell them about the school’s programs and activities so they can be prepared for discussions that may continue at home.

Encourage parents to limit their children’s exposure to news reports.

Encourage parents to limit their children’s exposure to news reports. - Take care of yourself. You may be so busy helping your students that you neglect yourself. Find ways for you and your colleagues to support one another.

Download a PDF version of this guide

Signs of Trauma in Children and Adolescents

- Constantly replaying the event in their minds

- Nightmares

- Beliefs that the world is generally unsafe

- Irritability, anger and moodiness

- Poor concentration

- Appetite or sleep issues

- Behavior problems

- Nervousness about people getting too close

- Jumpiness from loud noises

- Regression to earlier behavior in young children, such as: clinging, bed-wetting or thumb-sucking

- Difficulty sleeping

- Detachment or withdrawal from others

- Use of alcohol or drugs in teens

- Functional impairment: Inability to go to school, learn, play with friends, etc.

Snowflake children or lonely wolf cubs: is it possible to raise a child without injuries? This time we are also talking about security, but now it is about psychological. To patronize and be afraid to inflict injury on the child, or, on the contrary, to deliberately confront him with the realities of life? We understand.

There are two points of view on what level of psychological comfort a child needs.

Some people are skeptical about the idea of "dancing around a child on its hind legs, so as not to inflict psychological trauma on it." They talk about the generation of "snowflakes" raised in Europe and the USA, who were so protected from the slightest offense that now they are not able to meet any adult challenges. Say, that is why the level of teenage mental disorders has grown so much: pampered children who did not have to cope with difficulties on their own, who were indulged by their parents, met with the harsh real world, where no one will love you just like that, just for what you are, indulge and praise you.

Others argue that it is our commitment to consider the needs of children that develops in them the ability and desire to consider the needs of others. An understanding and loving parent is the best school for emotional intelligence and empathy. On the contrary, harsh conditions (tough demands of the family, bullying and fights that are offered to “handle on your own”, the need to grow up early) do not harden the child at all, but kill him ahead of time, force him to form protective mechanisms that interfere, rather than help, the life of a future adult .

Who is right? Are there any general principles of a child's psychological comfort that need to be observed in upbringing?

1. The child's feelings need support

We believe that any child's feelings have a right to exist.

Yes, absolutely anything. Even what we think is nonsense. And even the one that revolts us.

Even when a child is whining over trifles and you want to tell him: “Just stop crying, no one has died, let's dry our tears and move on. ”

”

Even when he asks if it is possible to take the newborn sister back to where they came from. Or he refuses to kiss his grandmother because she smells bad.

It is not a matter of necessarily sympathizing with the child in everything. But about teaching a child to deal with these feelings. And for this they have to be recognized first.

Yes, people smell differently. But it would be better not to show this to grandma. Your feelings are understandable, it’s not a shame to feel like that, but grandmother also has feelings, and they must also be taken into account.

It is clear that this is a complex construction, and the child will not understand it immediately. But he will understand. And only if we explain, and not resent. And for starters, let's join the child: yes, I see your feelings, I partly understand them.

This will not make the child a pampered whiner, but will teach him to better understand himself, and others too.

2. Children learn from examples

If a child was cruel to a cat, and we responded by spanking the child, he is not learning not to torture animals, he is learning cruelty.

If a child has behaved badly, and we shame him, he does not learn the right behavior, he learns that he himself is wrong and bad, which means that he will not be able to do well.

Negativity in upbringing (violence, ignorance, shaming, swearing and punishment) is bad not only because it “inflicts psychological trauma on the child”, but because he does not work

What works? Just an example. None of us fight. In our family, they don’t drag a cat by the tail, they don’t grab people by the hair. Have you ever heard dad make fun of me and tease me? (We hope that nothing like this really happens in your family.)

It is clear that we cannot always restrain ourselves and will still swear, sometimes shout, and sometimes someone in our hearts cannot resist a slap. But we must understand that this is not education, but simply our emotions. And it would be better to immediately explain this to the child: "I slapped you because I was very scared when I saw you on the windowsill. "

"

3. A child learns to understand himself and others gradually

It would not occur to us to teach a two-year-old child to cross the road on his own. But for some reason, when it comes to feelings, many people think that children should immediately learn to cope with everything on their own.

Sometimes you have to see how on the playground a baby who has just learned to walk falls down, cries, and instead of comforting him, his father puts him on his feet and teaches: “Well, why are you upset, you’re a kid.”

We gradually transfer responsibility for his feelings to the child. If we simply console a three-year-old, no matter what, because he himself cannot cope with his feelings, then a six-year-old can already be left to get angry and offended. These are his feelings, his character, and already partly his choice of how long to sit puffed up, whether to go to put up. And for a nine-year-old, it’s quite possible to say: “You know, I’m very angry with you now, and I still can’t make up. When I can, I'll tell you."

When I can, I'll tell you."

4. The children's team will not "do it on their own"

Russians are not accustomed to the zero tolerance for fights set in schools in the United States and many other countries. We have an idea that a child older than 7–8 years old (especially a teenager) should manage his school communication on his own. Calling adults for help means being a sneak and an informer.

This is not true. The children's team, like an individual child, needs purposeful upbringing and cultivation. He needs to instill norms of cultural interaction.

Without the intervention of adults, the children's team does not have the ability to self-regulate. This does not mean that an adult should vigilantly monitor all the interactions of children. It is enough to set the rules and constantly emphasize that he, the adult, controls and guarantees their observance. You can always approach him and tell how the matter was, and he will listen to both sides and sort it out, as far as possible, in fairness.

5. A parent should not forget about his needs

Gradually, as the child grows, we more and more often leave the role of a parent and more and more communicate with the child on an equal footing. With a baby, we cannot get tired, angry and offended "on an equal footing" - he will not understand us, he will not stand it, he will be frightened. But for a six-year-old child, we can already ask for help, explaining that we are just tired or upset about something. And the older the child, the more such acceptable situations.

Gradually, we begin not only to support the child’s feelings, but also to honestly tell him about ours: “It upsets me that you don’t want to hug your grandmother, because this is my mother, I love her so much.” Not because we want to manipulate him into hugging, but because we are really upset, and we think that the child is already at such an age that he can understand us.

This happens as they grow up, and when a child grows up, he is no longer a “snowflake” that needs to be protected, but a person equal to us. I have feelings, you have feelings - let's understand each other, and not make claims and not accumulate resentment.

I have feelings, you have feelings - let's understand each other, and not make claims and not accumulate resentment.

Thus, the fear of "raising a fragile creature who does not care about others and focuses only on his own problems" is unfounded. The psychological comfort of a child does not mean that we dance around him on tiptoe, raise an egocentric and protect him from all troubles and disappointments.

Photo: Shutterstock / Everett Collection

Is it possible to protect a child from psychological trauma?

Self-doubt, low self-esteem, addictions, aggressive behavior - may be the consequences of the psychological trauma experienced by the child. What traumatic factors are especially dangerous for child development? How to raise a child so as not to injure his psyche?

How does psychological trauma manifest itself?

One of the signs of a caring attitude towards a child is to monitor his emotional well-being, protect him from stress and anxiety, and support him when unpleasant situations happen in life. So, a child, having enlisted the support of adults, is more likely to grow up as a self-confident and strong person.

So, a child, having enlisted the support of adults, is more likely to grow up as a self-confident and strong person.

When parents are unaware of what happens to children during the development of emotional trauma, the child runs the risk of being left alone with their experiences. By what signs in children's behavior can one understand that the child's mind is traumatized and he needs help?

emotional and behavioral. Refusal to communicate, isolation, increased anxiety, fears, phobias, tearfulness, aggressiveness - directed at oneself or other people - infantile behavior.

Physical. Eating and sleep disorders, stuttering, enuresis, psychosomatic illnesses.

If parents see that one or more of these signs appear in a child, one should think about what provoked their appearance and how to help the child cope with them. How to do it, and what rules must be followed?

It is impossible to ignore the dangerous symptoms of psychological trauma that manifest themselves on the mental, physical levels or are hidden. Otherwise, it can lead to increased negative consequences. Children, if they are not helped in time, live, getting used to strong experiences. To deal with them, the child may make an internal decision to "not be healthy", "not be an adult", "not be a child", "not be smart", "be perfect", and so on. So, he defends himself from the destructive effect of trauma, however, his behavior acquires its consequences. In the first case, children get sick all the time, tend to get into situations that threaten their life and health. In the second, the child behaves as if he will never grow up. His reactions are childish, he is in emotional regression. A big child - that's what people around him can say about him. He is incapable of solving problems and coping with difficulties.

Otherwise, it can lead to increased negative consequences. Children, if they are not helped in time, live, getting used to strong experiences. To deal with them, the child may make an internal decision to "not be healthy", "not be an adult", "not be a child", "not be smart", "be perfect", and so on. So, he defends himself from the destructive effect of trauma, however, his behavior acquires its consequences. In the first case, children get sick all the time, tend to get into situations that threaten their life and health. In the second, the child behaves as if he will never grow up. His reactions are childish, he is in emotional regression. A big child - that's what people around him can say about him. He is incapable of solving problems and coping with difficulties.

The internal setting “don’t be a child” - on the contrary, makes you become an adult ahead of time. Such children lose their childish part early, they rejoice and laugh a little, they do not know how to relax, enjoy life and communication. Being young, they often suffer from heart disease, experience heart attacks.

Being young, they often suffer from heart disease, experience heart attacks.

The decision made in childhood to “not think” and “not understand” can lead the child to deny his ability to analyze. To pretend to be stupid for him is safe and secure. Such people do not tend to reach heights in their personal lives and careers, to feel satisfied and happy.

Striving for perfection in everything may be the result of excessive criticism to which the child was subjected, as a result of which a psychological trauma formed. Such people have perfectionism, make excessive demands on themselves, try to do everything perfectly and demand the same from others. They are always in a hurry, live according to the plan, deviation from it is regarded by them as a gross violation of the way of life. It is not easy to be with such a person.

Knowing about these consequences, parents try their best to protect the child from psychological trauma. What can this lead to?

7 important questions about baby diapers

Note to moms: how to choose the right diapers and not be fooled by advertising?Overprotection of parents

If adults patronize children, “lay straws” wherever they can “fall”, they thereby deprive them of important life experiences and develop overprotective relationships with them. What is included in them? The habit of doing for the child everything that relates to his responsibility and what he is able to do for himself. Because of this, the child does not acquire the skill of independence.

What is included in them? The habit of doing for the child everything that relates to his responsibility and what he is able to do for himself. Because of this, the child does not acquire the skill of independence.

If parents solve problems for their children at school, institute, protect them every time, even when no one asks for it, the children do not know what it is to overcome obstacles and defend their point of view. In the future, this may lead to the fact that they will not be able to stand up for themselves when relatives are not around, they will not have respect from the people around them.

Sometimes children suffer more and experience the consequences of emotional trauma if adults do their best to save them from unpleasant life experiences. How to be parents? Where to look for the "golden mean" in relationships with children?

Developmental trauma in a child

Sometimes traumatic experiences are unavoidable. This happens when the child is going through an age crisis and his views and feelings clash with the parent's perception system. So, for example, children can take all events too close to their hearts, worry about this, and, on the part of parents, it is impossible to create conditions for them where they could feel good. Developmental trauma, in this case, the living of painful emotions, resistance to adults, mental pain are necessary processes of childhood growing up. They are part of a turning point for the psyche, however, without them it is impossible to develop that side of the personality that will be responsible for overcoming obstacles and maintaining mental health.

So, for example, children can take all events too close to their hearts, worry about this, and, on the part of parents, it is impossible to create conditions for them where they could feel good. Developmental trauma, in this case, the living of painful emotions, resistance to adults, mental pain are necessary processes of childhood growing up. They are part of a turning point for the psyche, however, without them it is impossible to develop that side of the personality that will be responsible for overcoming obstacles and maintaining mental health.

Trauma and guilt

It is impossible to raise a child in such a way that emotional trauma never touches him. Otherwise, it will be upbringing "under the hood", in greenhouse conditions, where dependence on others is the main factor of survival. Parents may blame and scold themselves when they realize that, in some cases, they failed to protect the child from negative events or they themselves, by mistake, harmed him. The feeling of guilt of the parents exacerbates the problems of growing up the child, spoils the relationship between them. You should relieve yourself of the obligation to be an “ideal adult”, stop scolding for any mistakes in upbringing - so the child will also learn to accept himself with shortcomings, and the likelihood of developing emotional trauma will become much lower.

You should relieve yourself of the obligation to be an “ideal adult”, stop scolding for any mistakes in upbringing - so the child will also learn to accept himself with shortcomings, and the likelihood of developing emotional trauma will become much lower.

Injured children

What to do if parents realize that the child has experienced stress, the consequences of which negatively affect his mental health?

To understand that experiencing any negative experience, on the one hand, can hurt a child’s soul, and on the other hand, tempers his ability to adapt to difficulties, find resources in himself to cope, “not to destroy” himself or others. A person can get injured not only in childhood, but also in adulthood, and then it will be much more difficult for him to survive it if his parents all the time protected him from receiving negative life experience.

For the health of the child's psyche, it is much more important if adults support the child in a difficult life period, will be there, allow feelings to live, show him that in life there is a place not only for joy, but also for anger, sadness, pain.